Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- It is cheaper and less time consuming, since trial and error analyses based on industrial pilot lines would be unaffordable.

- Numerical tools allow the evaluation of a material response without the physical use of the real material and without compromising mould manufacturing.

- CAE simulation routines provide the possibility to shorten the cycle time and optimize the curing duration to save energy and avoid material waste.

- Simulation is able to avoid re-design of the mould.

- CFD studies are able to predict processing-related defects in the injected part, such as weld lines and air traps.

2. Materials and Methods

- 800 rpm, 2 min, 800 mbar vacuum

- 1200 rpm, 2 min, 400 mbar vacuum

- 1600 rpm, 2 min, 100 mbar vacuum

- 1800 rpm, 4 min, 50 mbar vacuum

2.1. Determination of the Viscosity

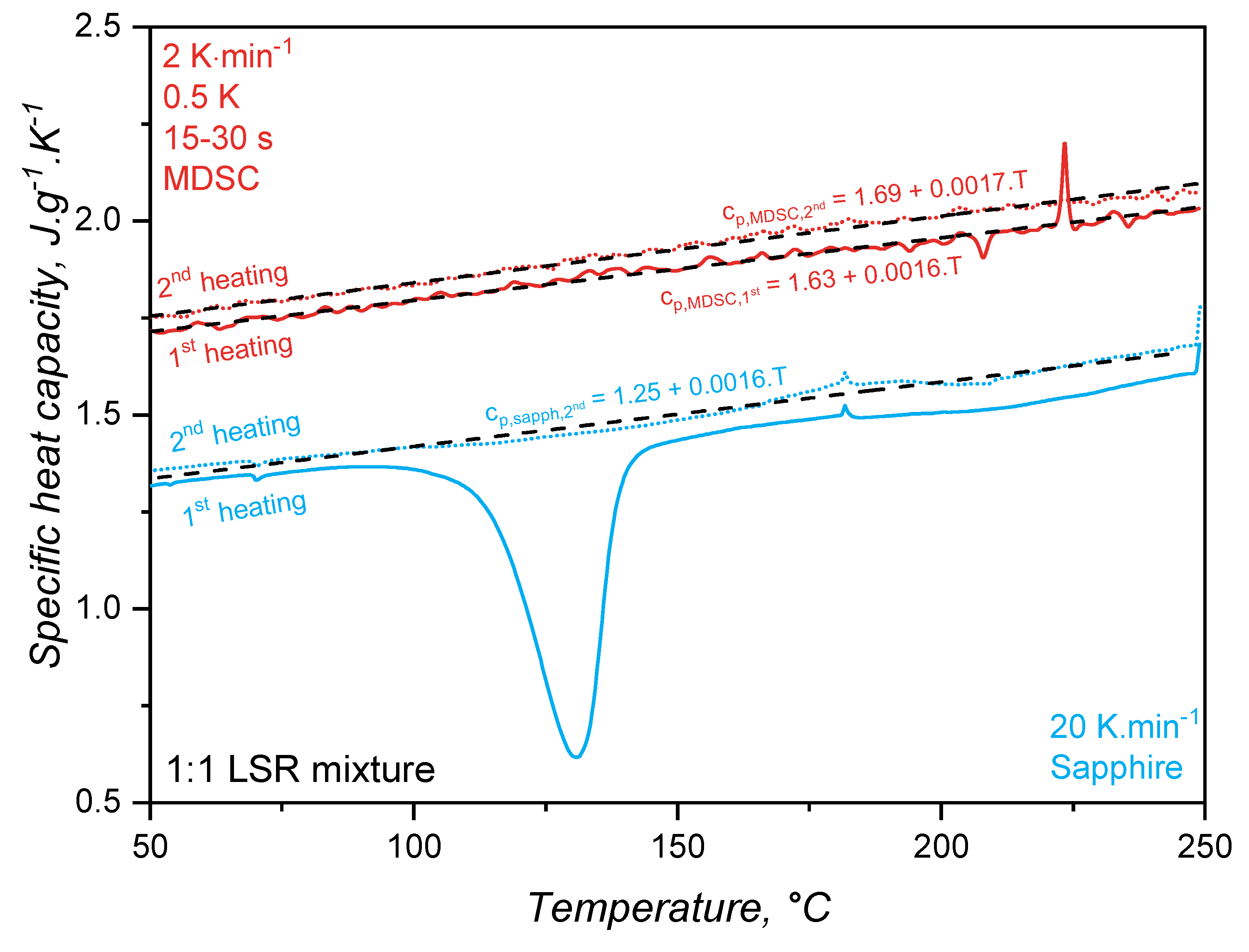

2.2. Determination of the Specific Heat Capacity

2.2.1. Sapphire Method ASTM E1296-11

- Isotherm for 4 min at 50°C.

- Heating at 20 K. until 200°C.

- Isotherm for 4 min at 200°C.

- Cooling at 20 K. until 50°C.

- Isotherm for 4 min at 50°C.

- Heating at 20 K. until 200°C.

- Isotherm for 4 min at 200°C.

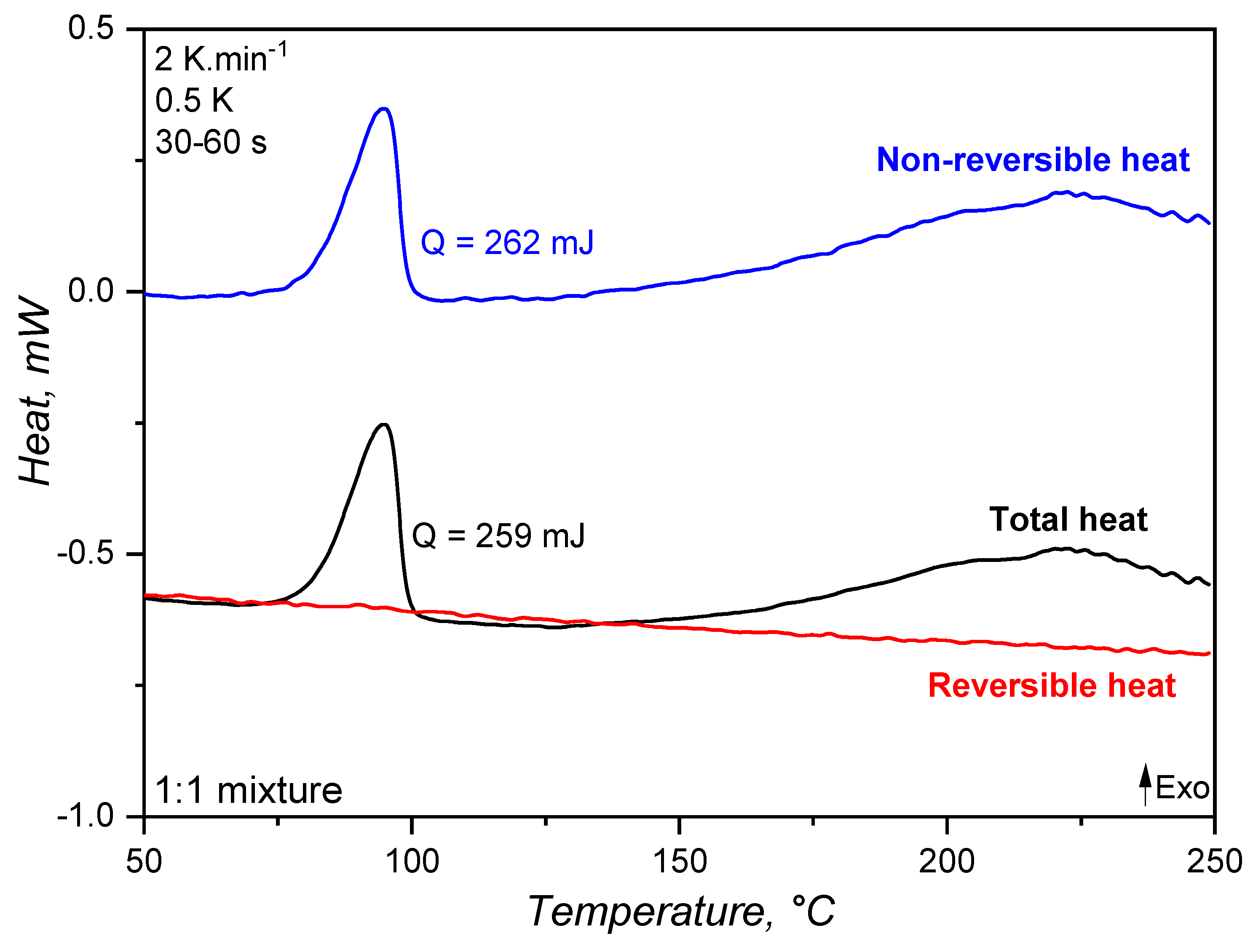

2.2.2. Modulated Temperature Calorimetry

- Isotherm for 1 min at 50°C.

- Heating at 2 K. until 250°C with temperature modulation.

- Isotherm for 1 min at 250°C.

- Cooling at 2 K. until 50°C without temperature modulation.

- Isotherm for 1 min at 50°C.

- Heating at 2 K. until 250°C with modulation.

2.3. Determination of the Thermal Conductivity

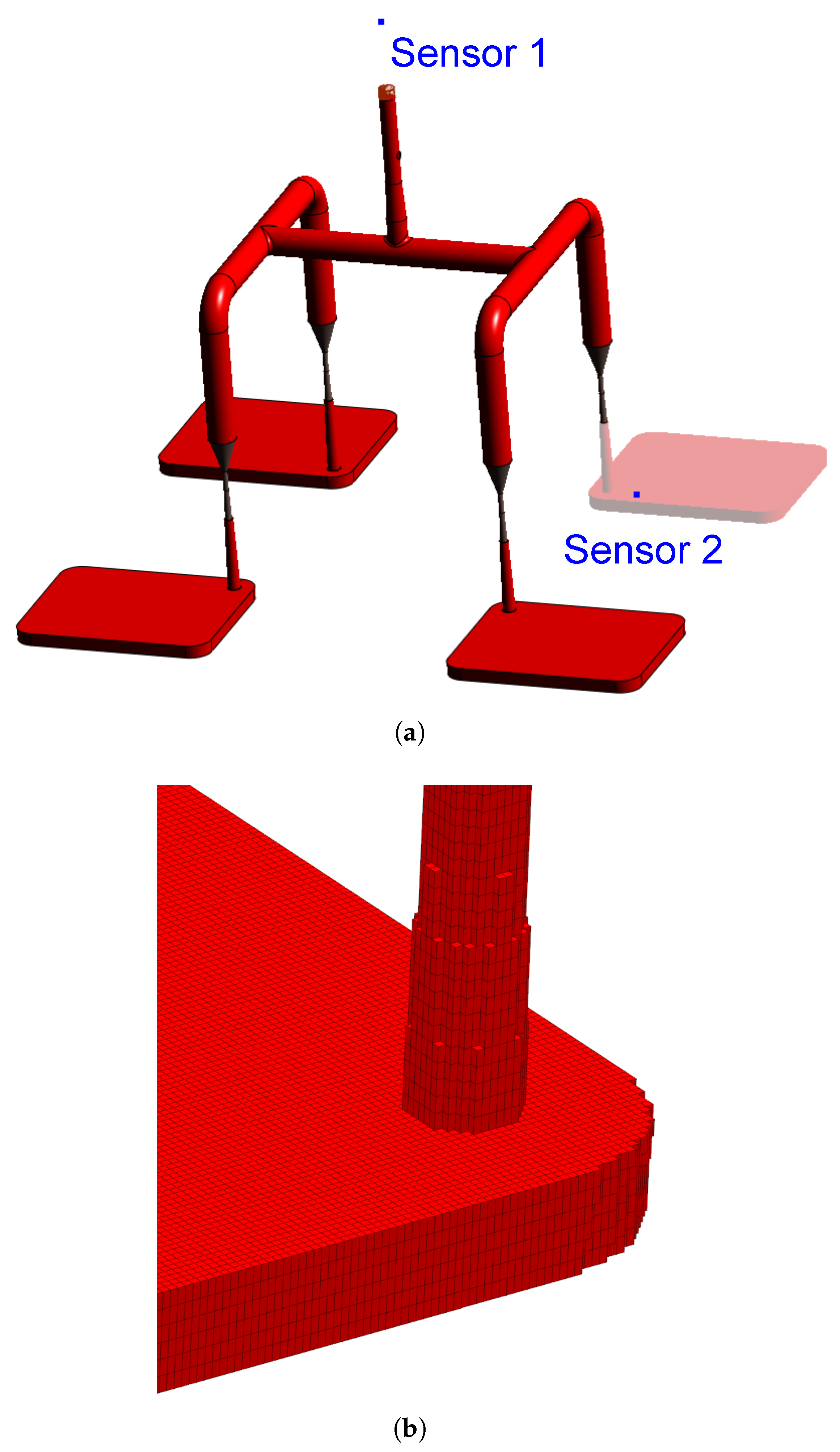

2.3.1. Transient Line-Source Technique

2.3.2. Guarded Heat Flow Meter Method

2.4. Determination of the Specific Volume

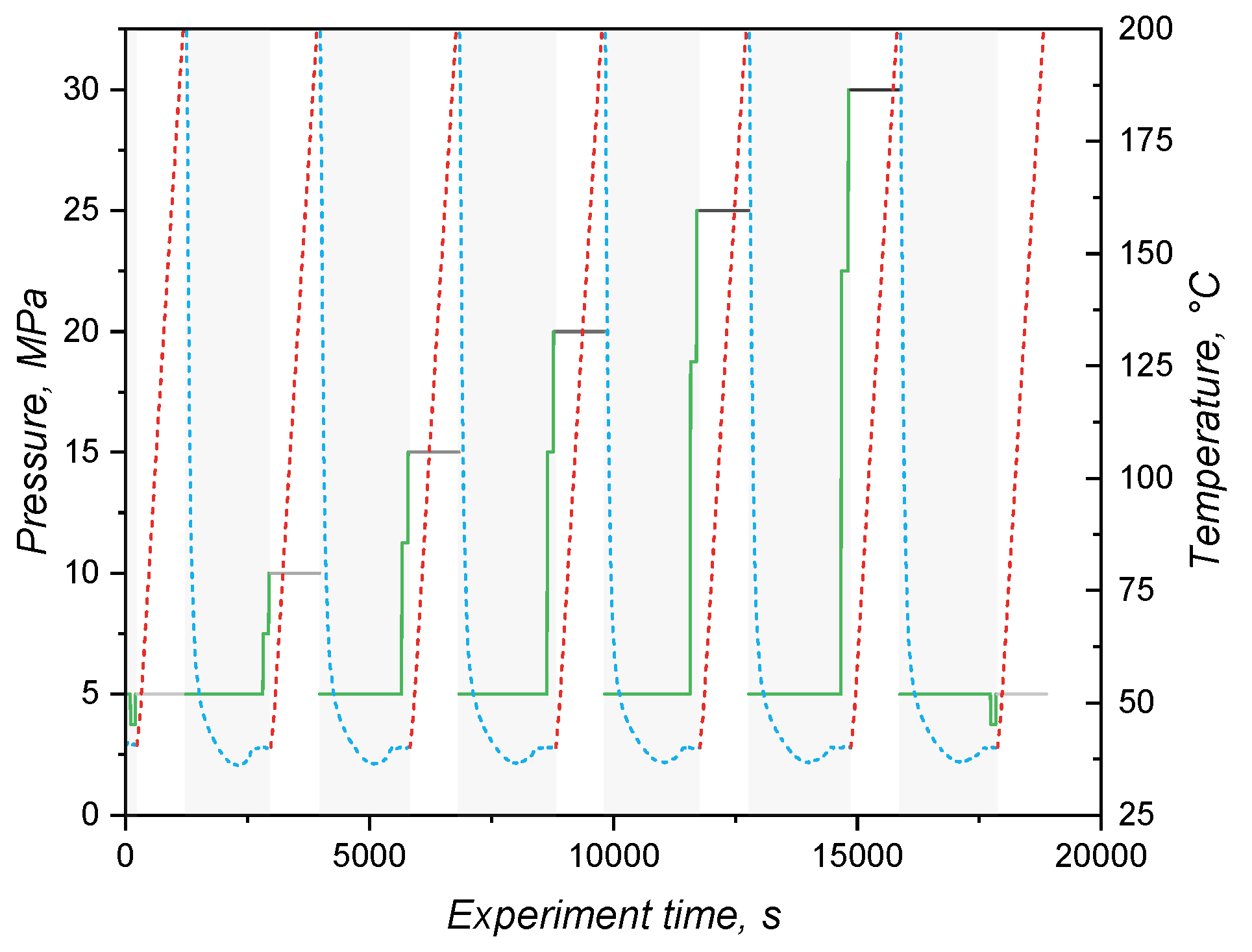

2.5. Determination of the Curing Kinetics

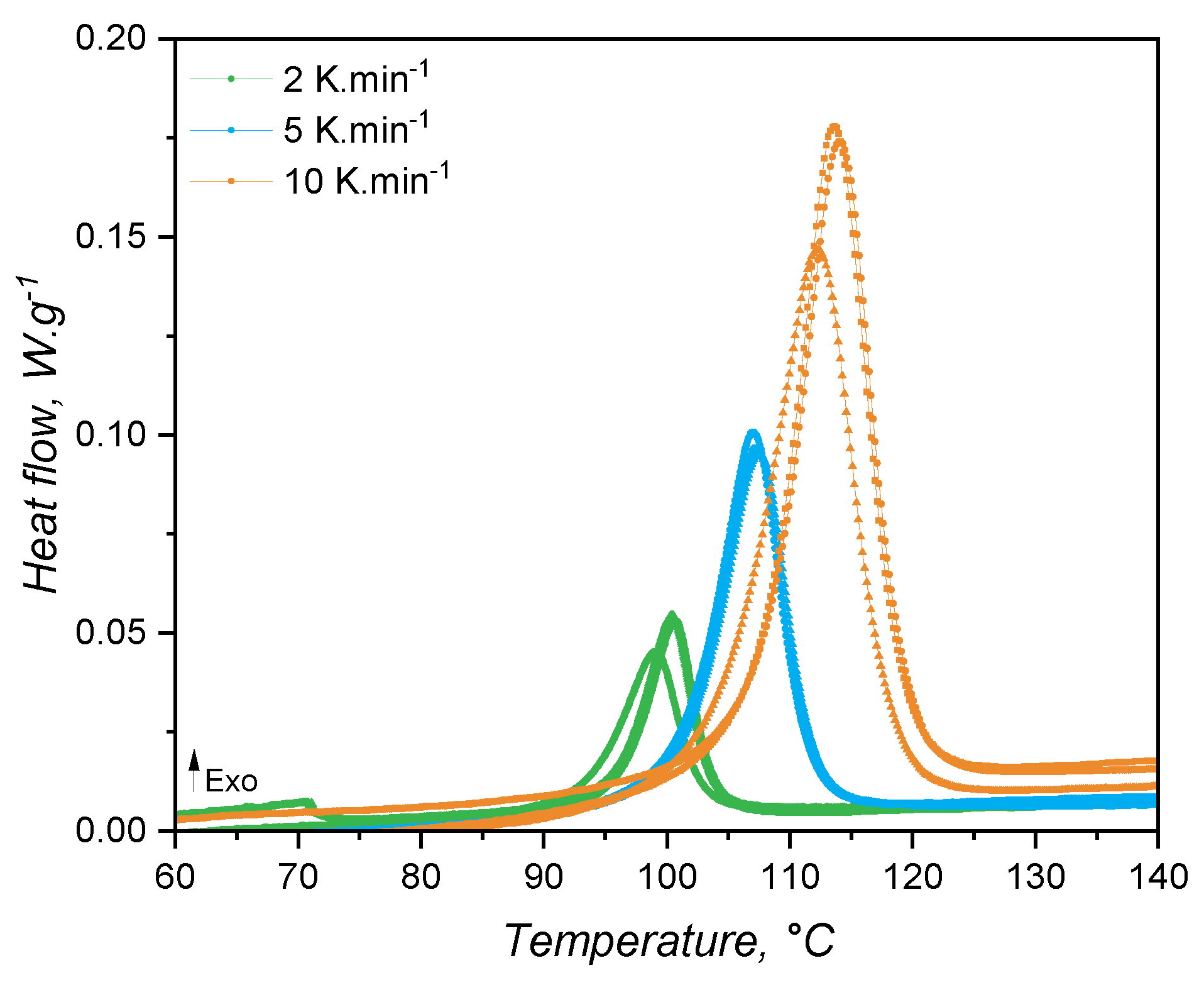

2.5.1. Dynamic Scanning Calorimetry

- Isotherm for 3 min at 50°C

- Heating at 2/5/10 K. until 150°C

- Isotherm for 5 min at 150°C

- Cooling at 20 K. until 50°C

- Isotherm for 3 min at 50°C

- Heating at 2/5/10 K. until 150°C

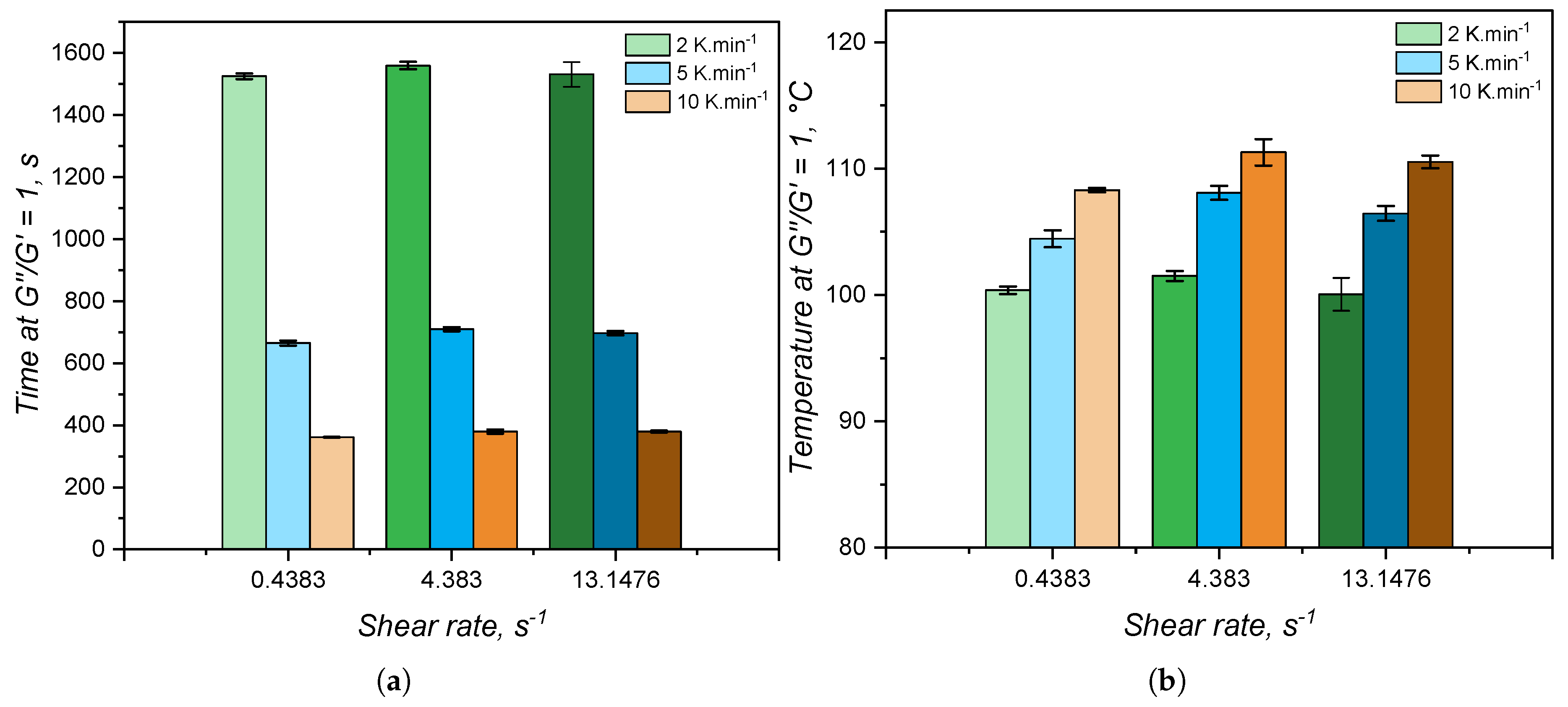

2.5.2. Non-Isothermal Rotational Rhometry

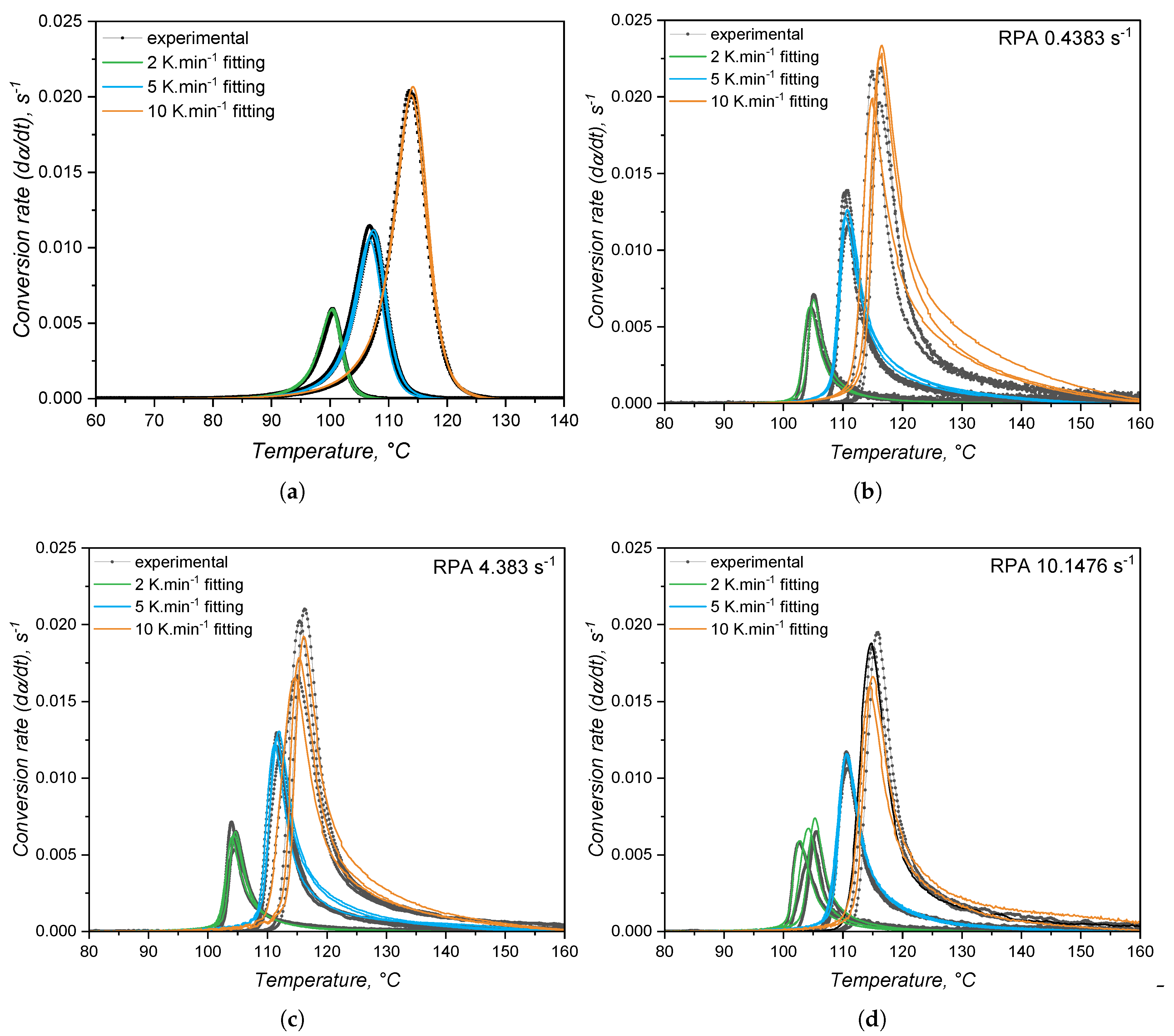

2.5.3. Curing Kinetics Non-Linear Fitting

2.6. Comparison Routines - Simulation Setup

3. Results

3.1. Specific Heat Capacity Trend

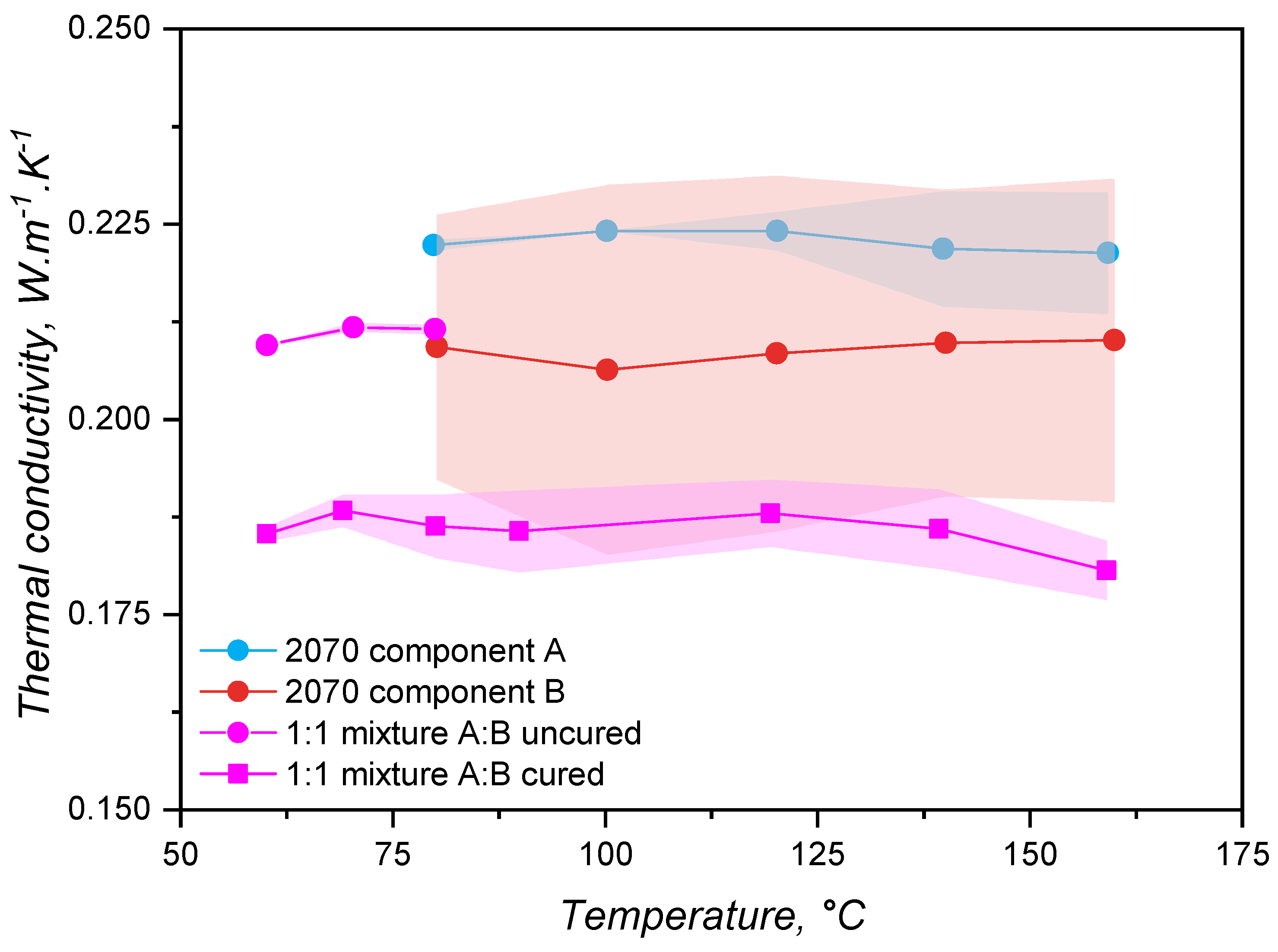

3.2. Thermal Conductivity Response

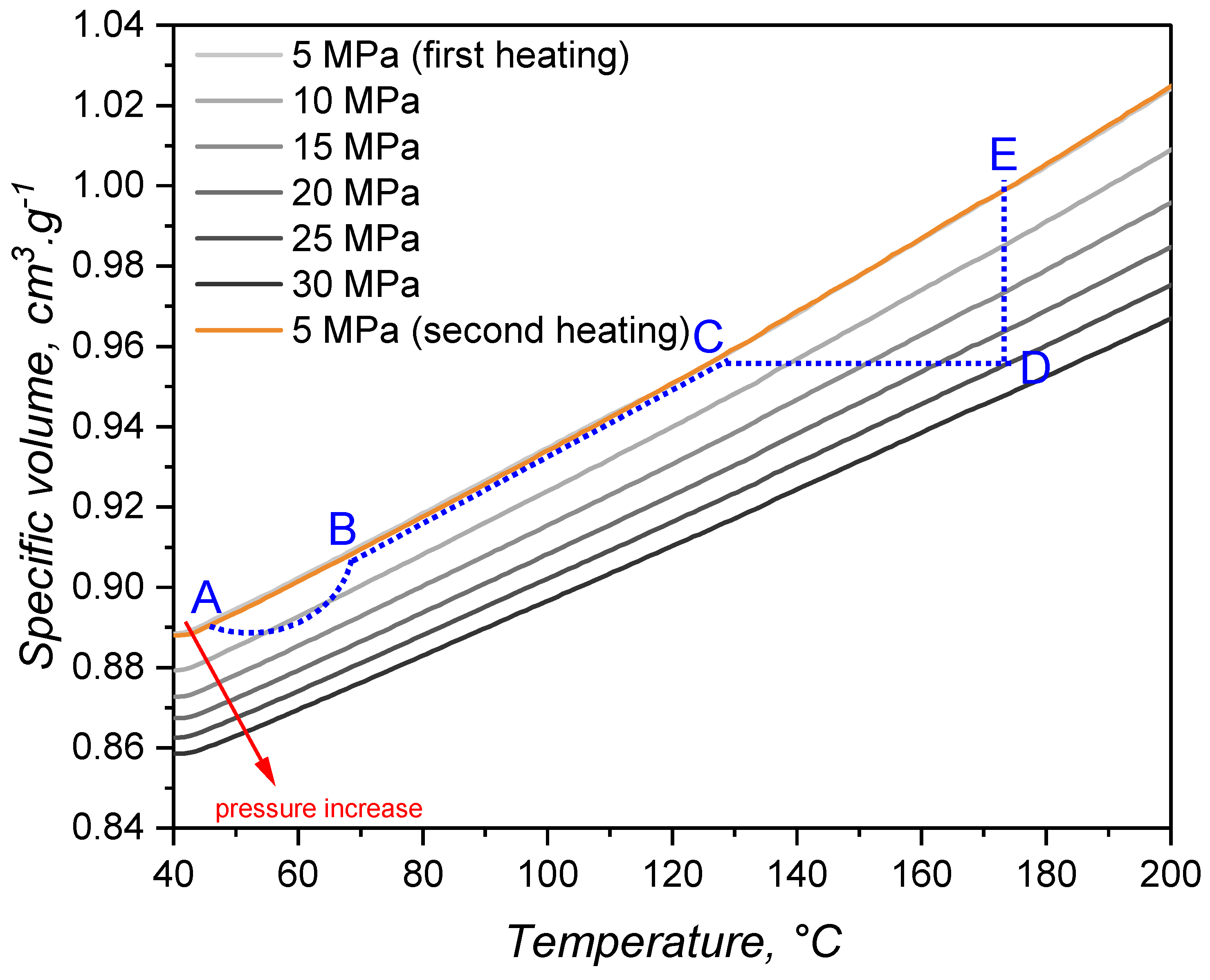

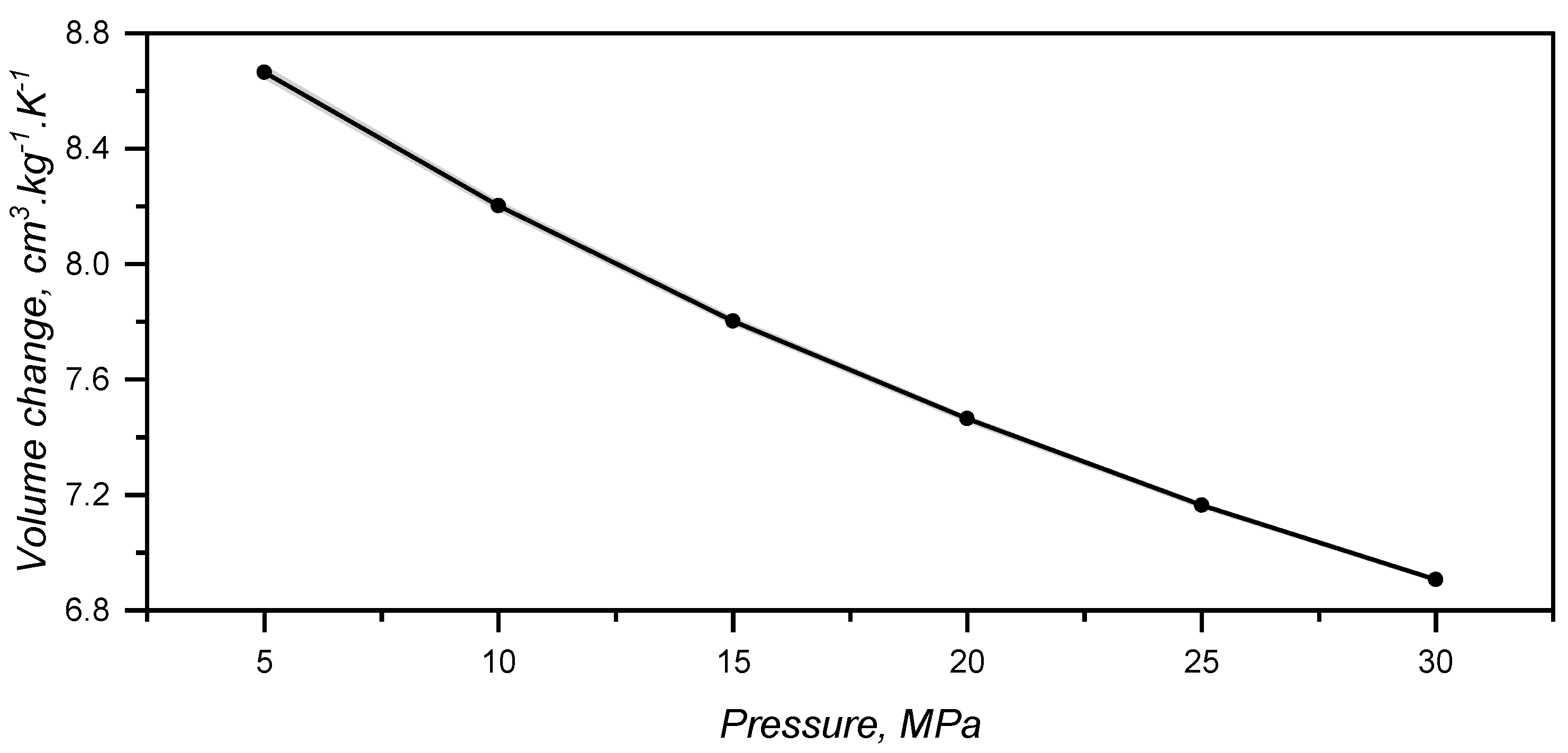

3.3. Specific Volume or pvT Behaviour

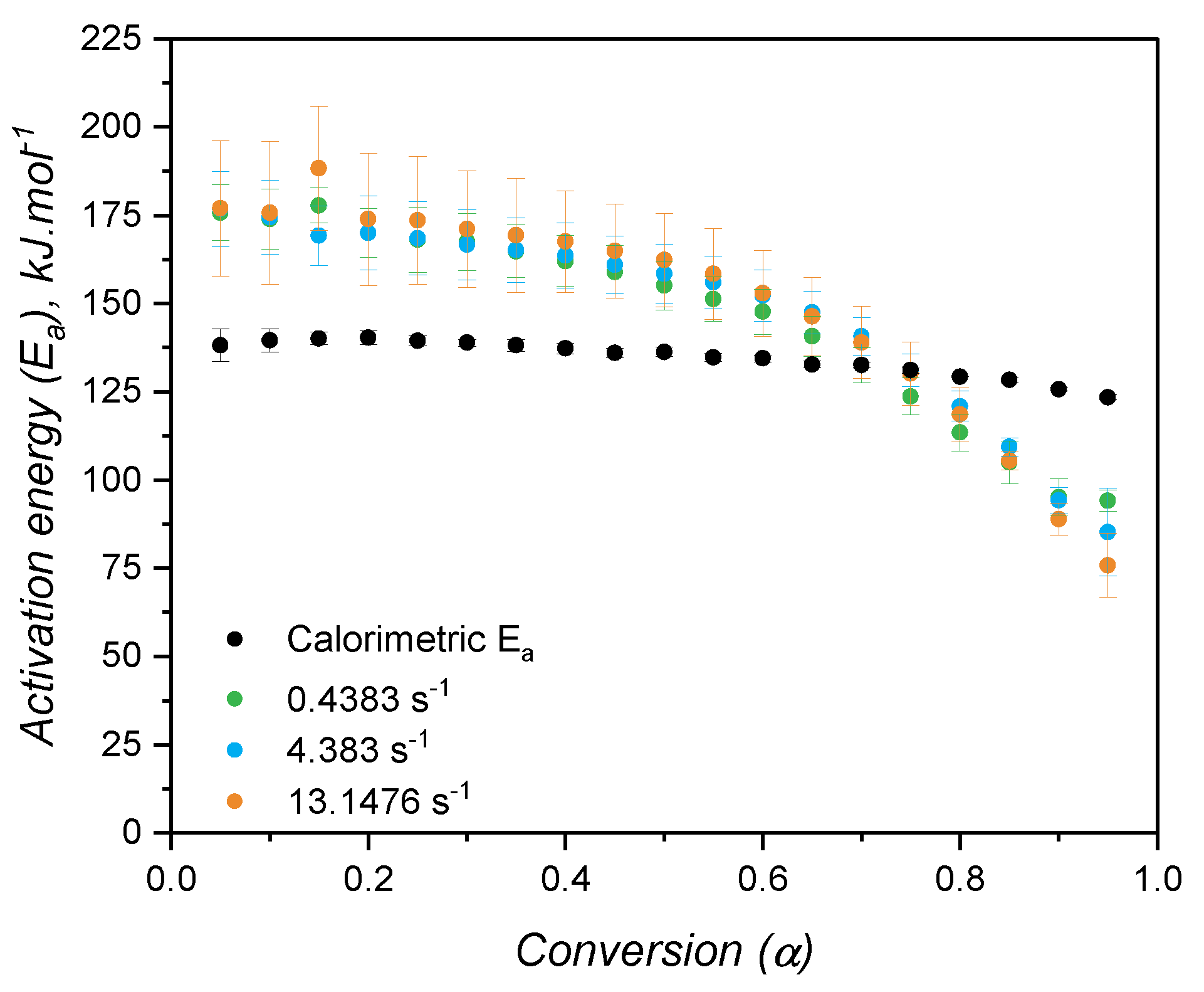

3.4. Crosslinking Kinetics Characteristics

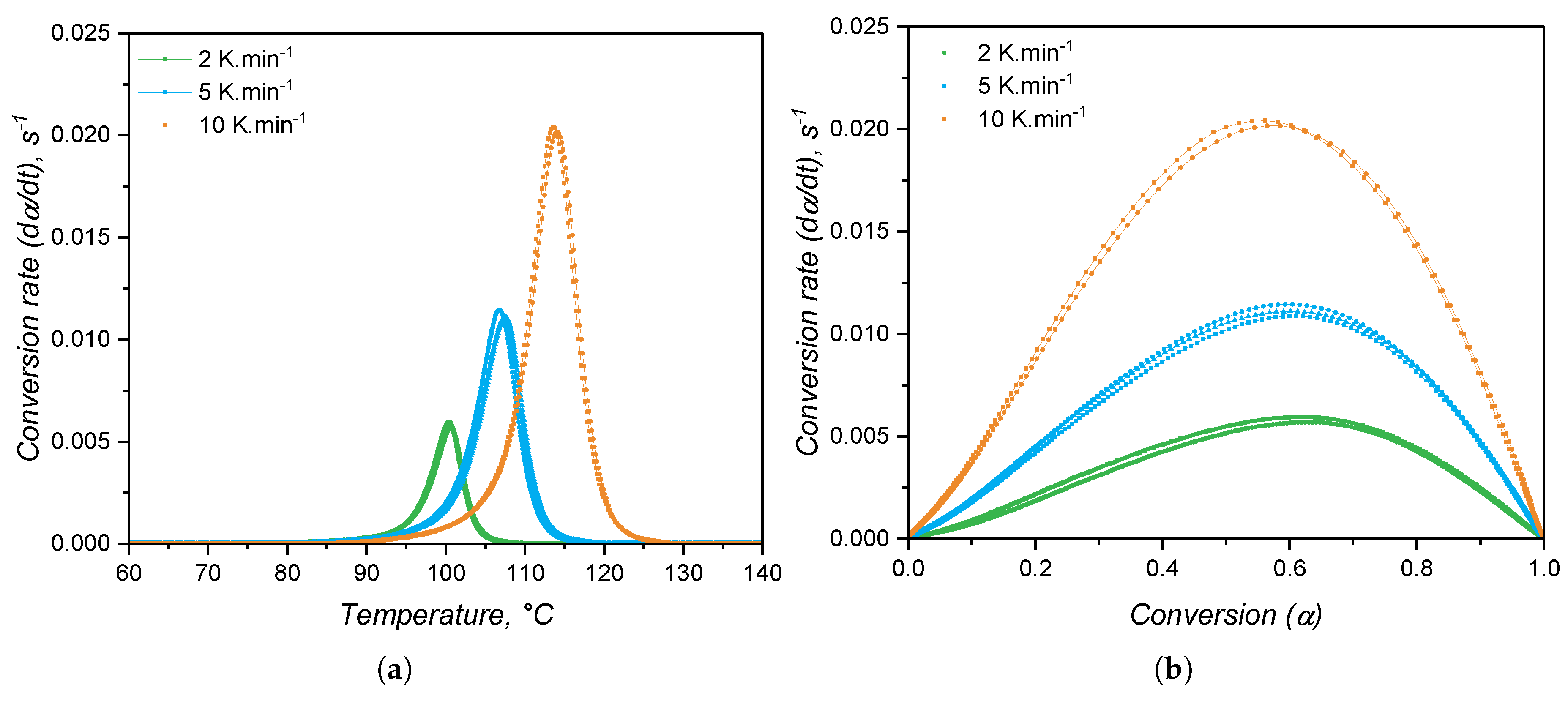

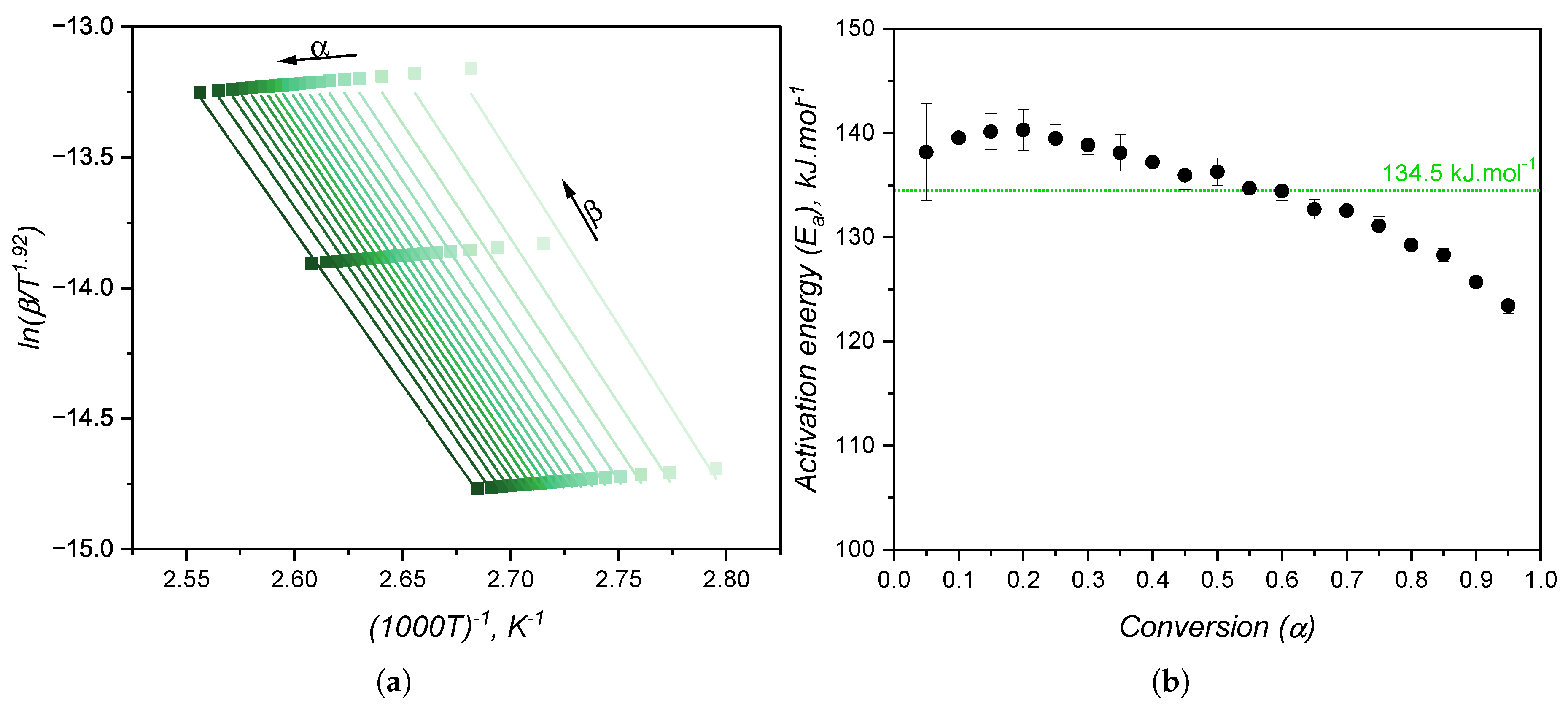

3.4.1. Curing Kinetics via DSC

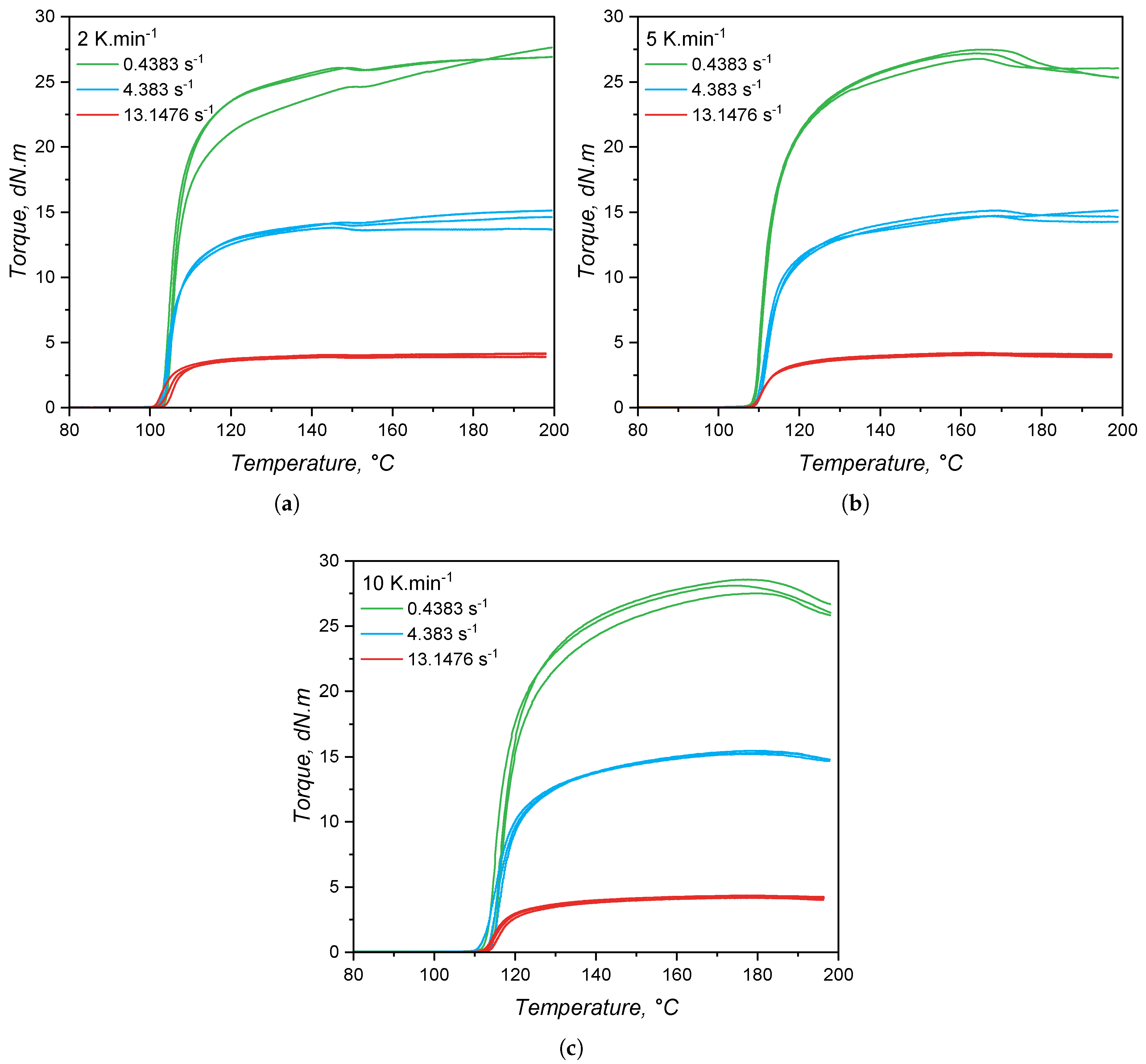

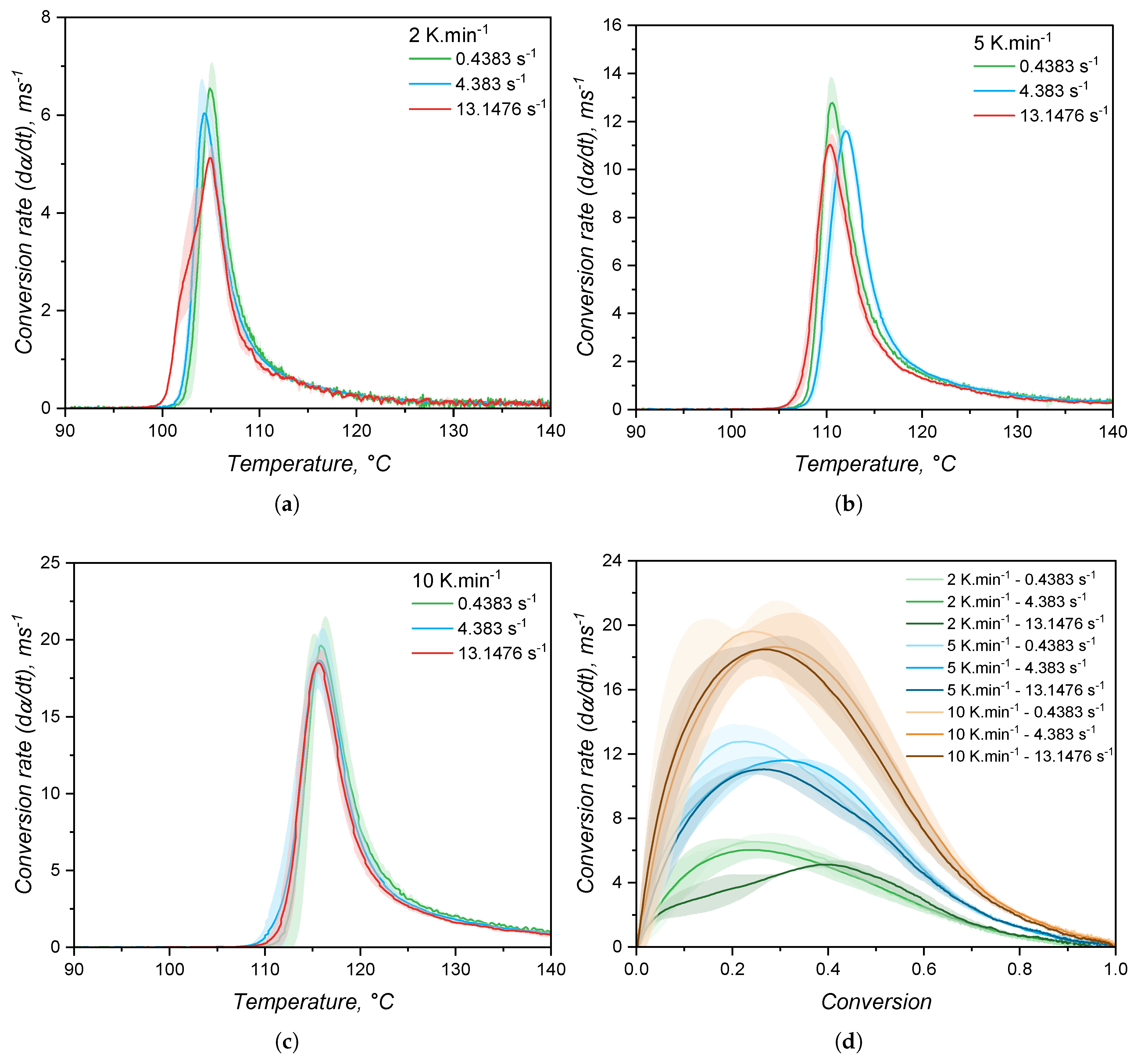

3.4.2. Curing Kinetics via RPA

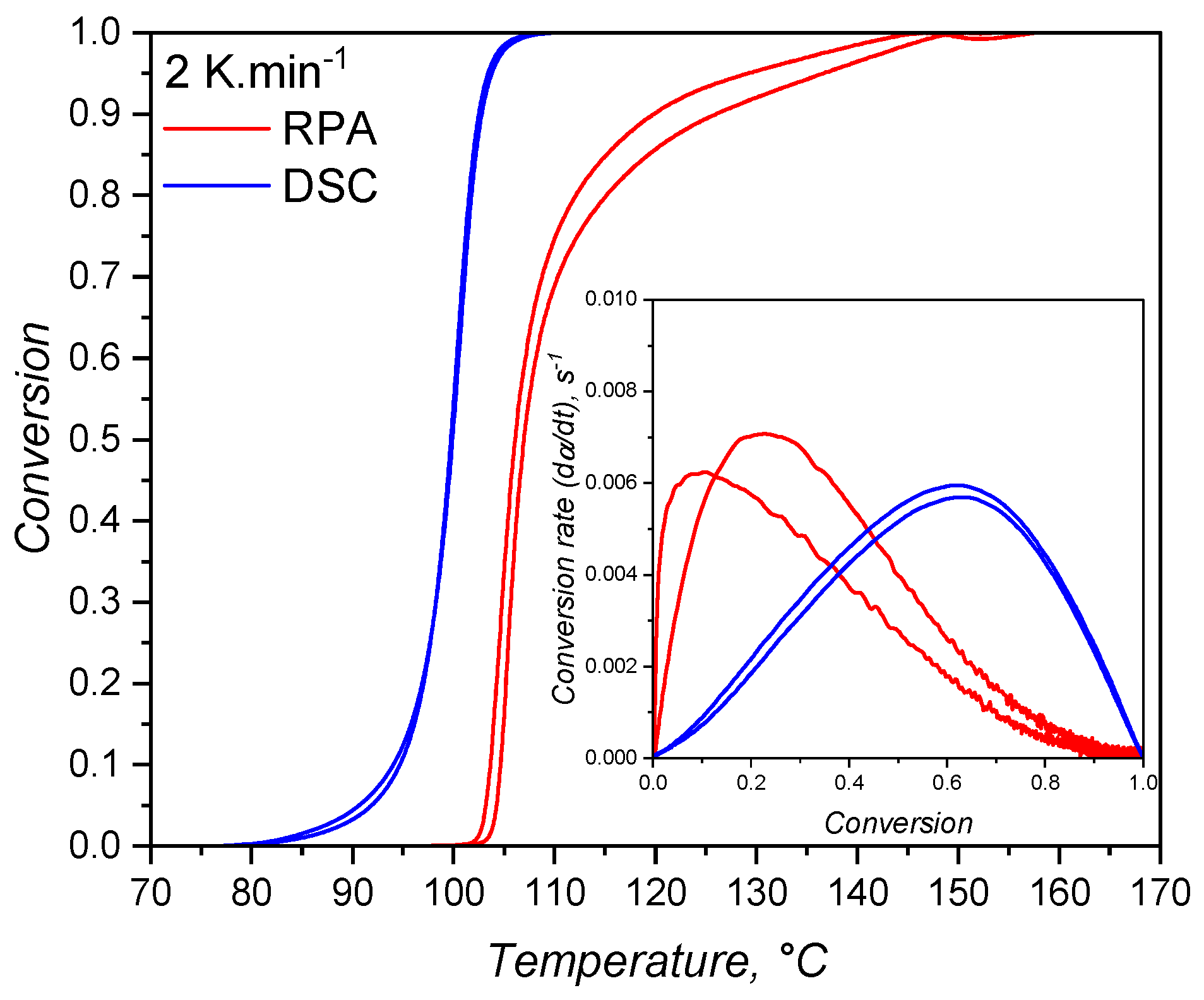

3.4.3. Fitting and Comparison Between DSC and RPA

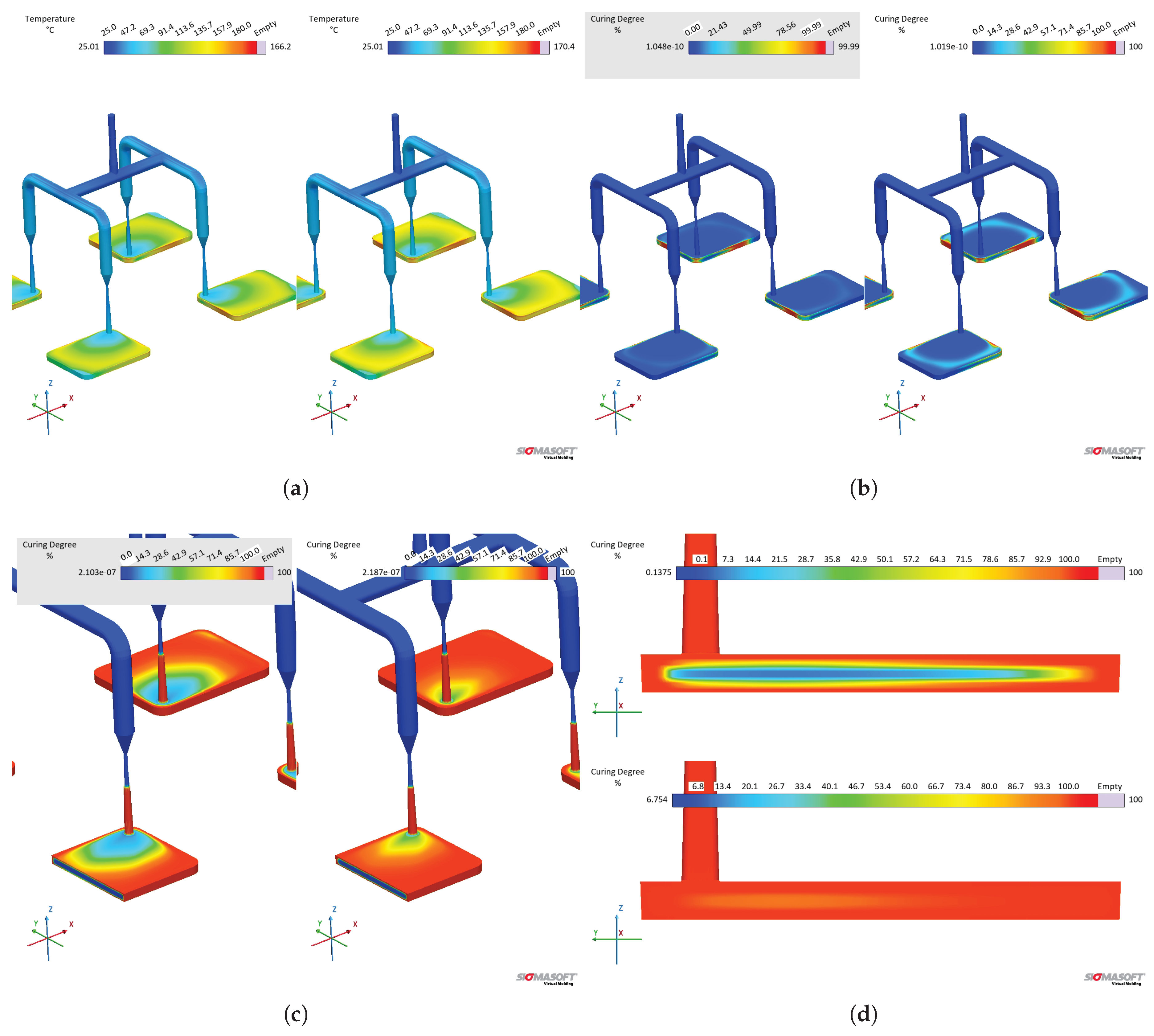

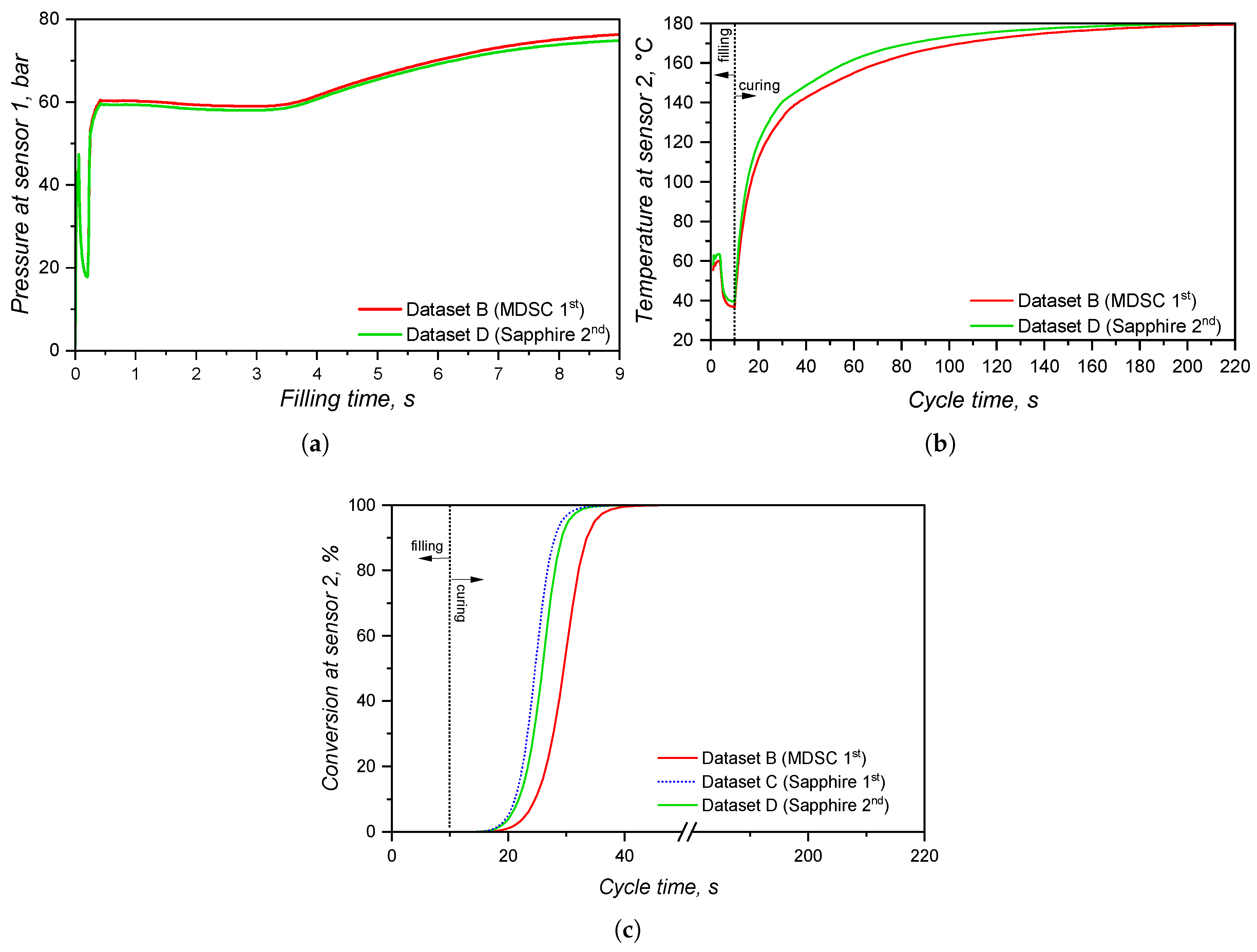

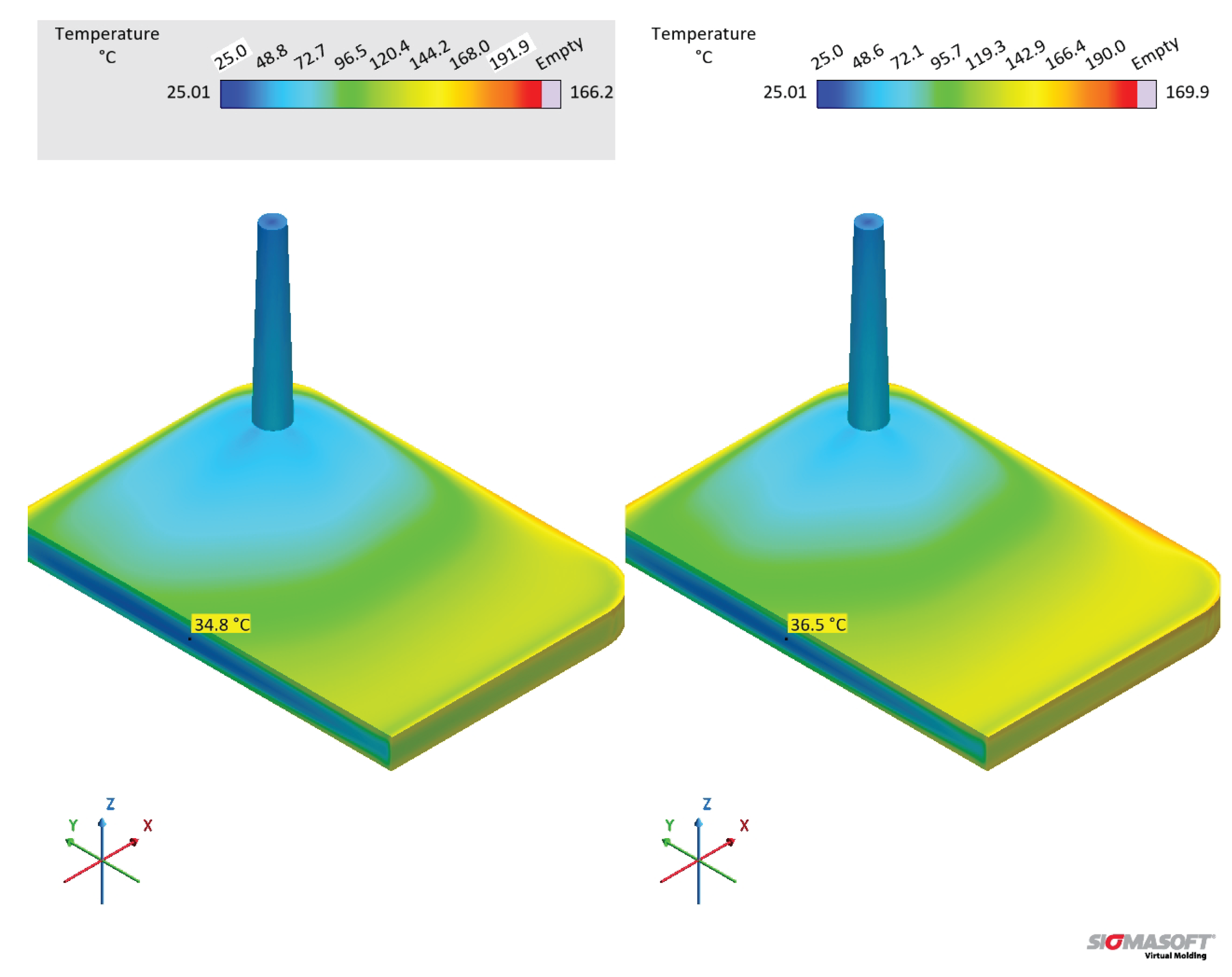

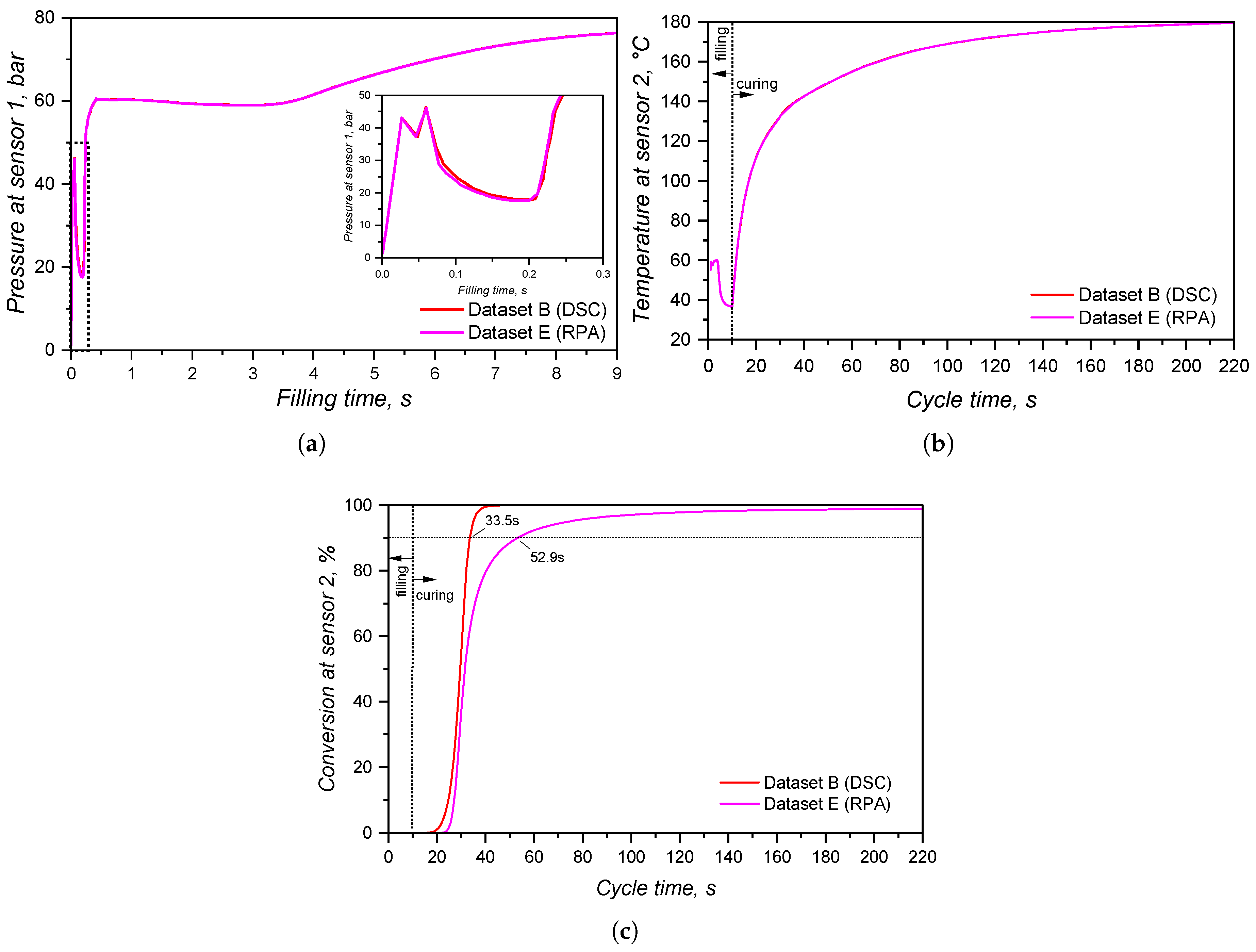

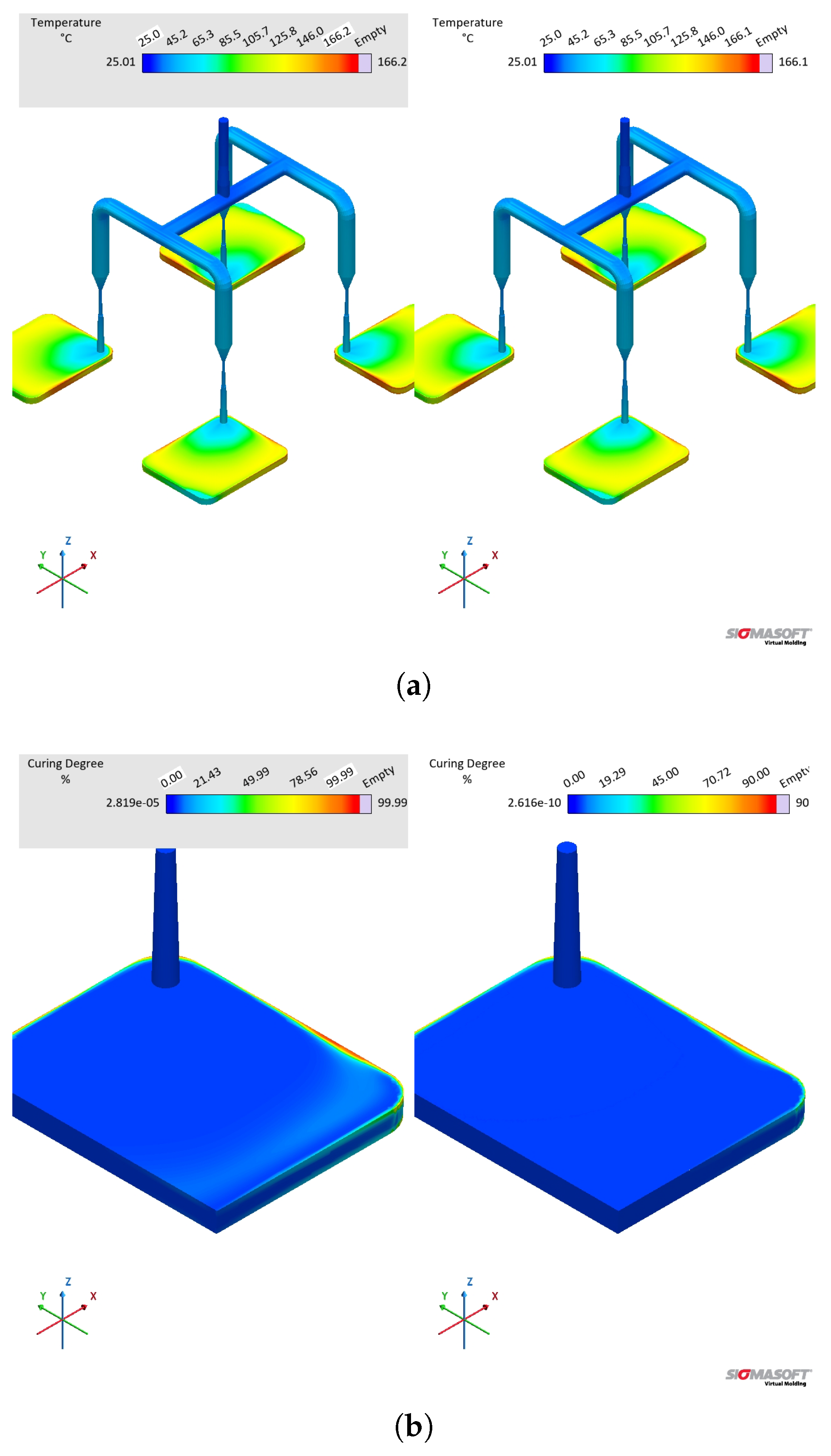

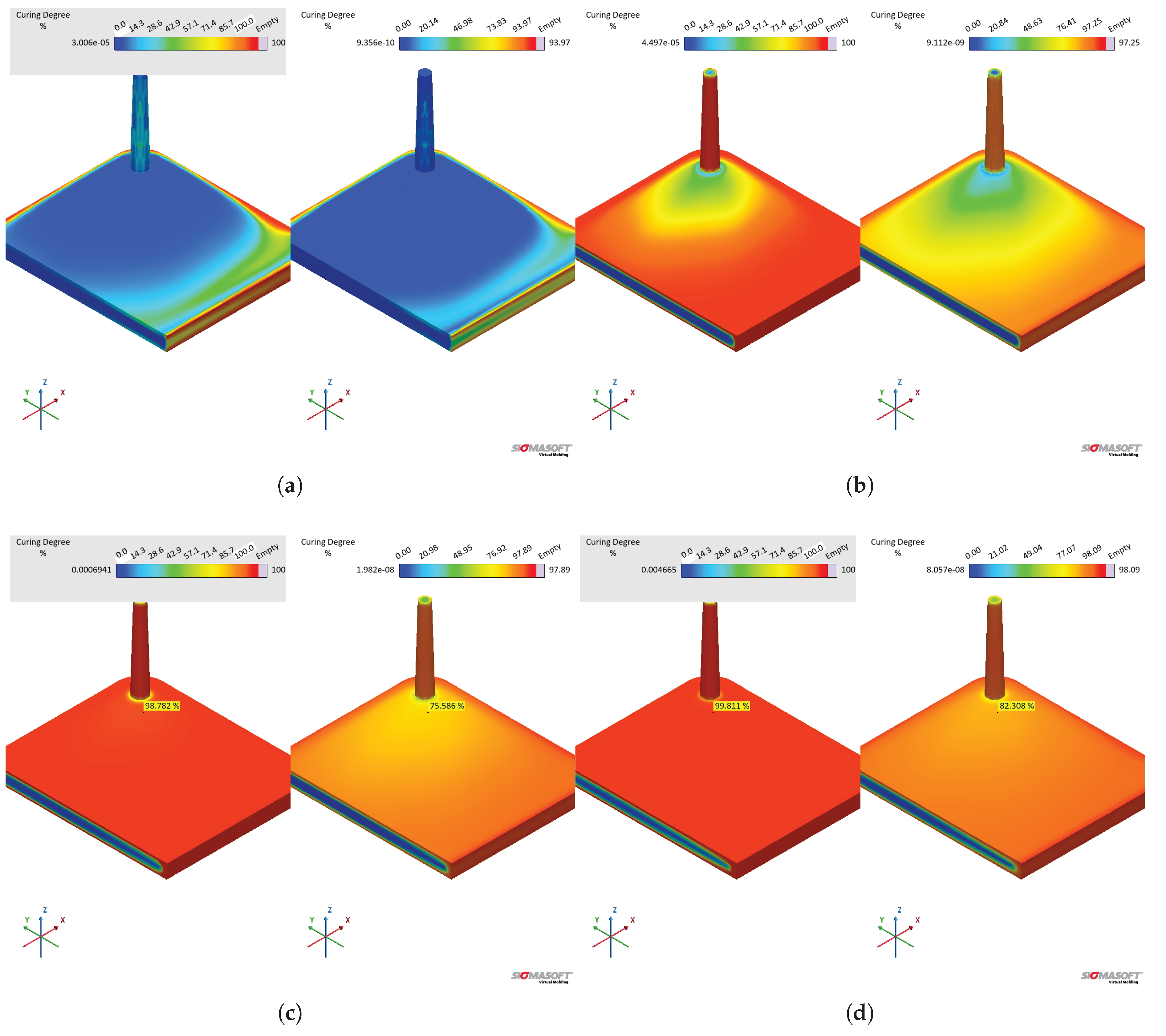

3.5. Injection Moulding Simulations

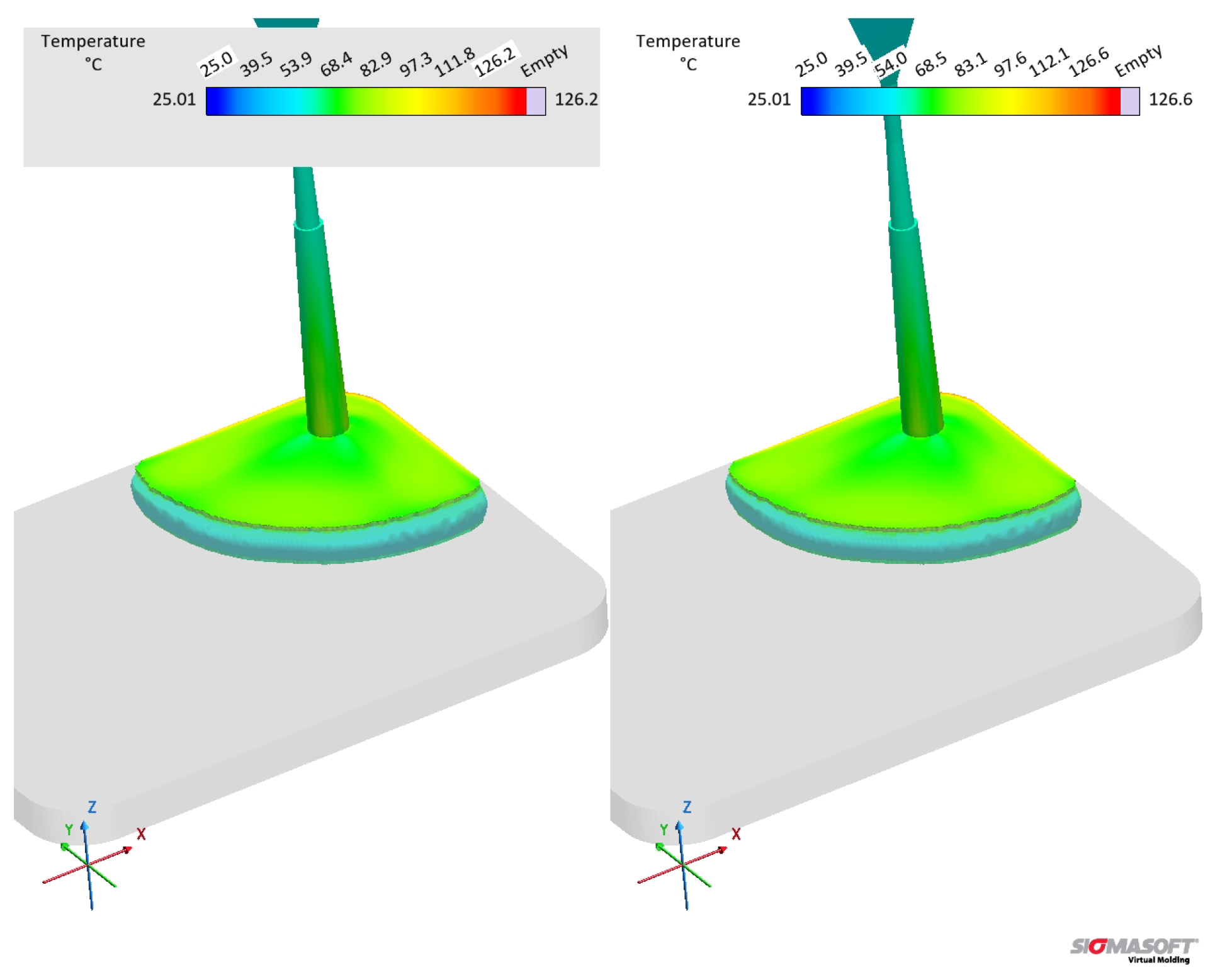

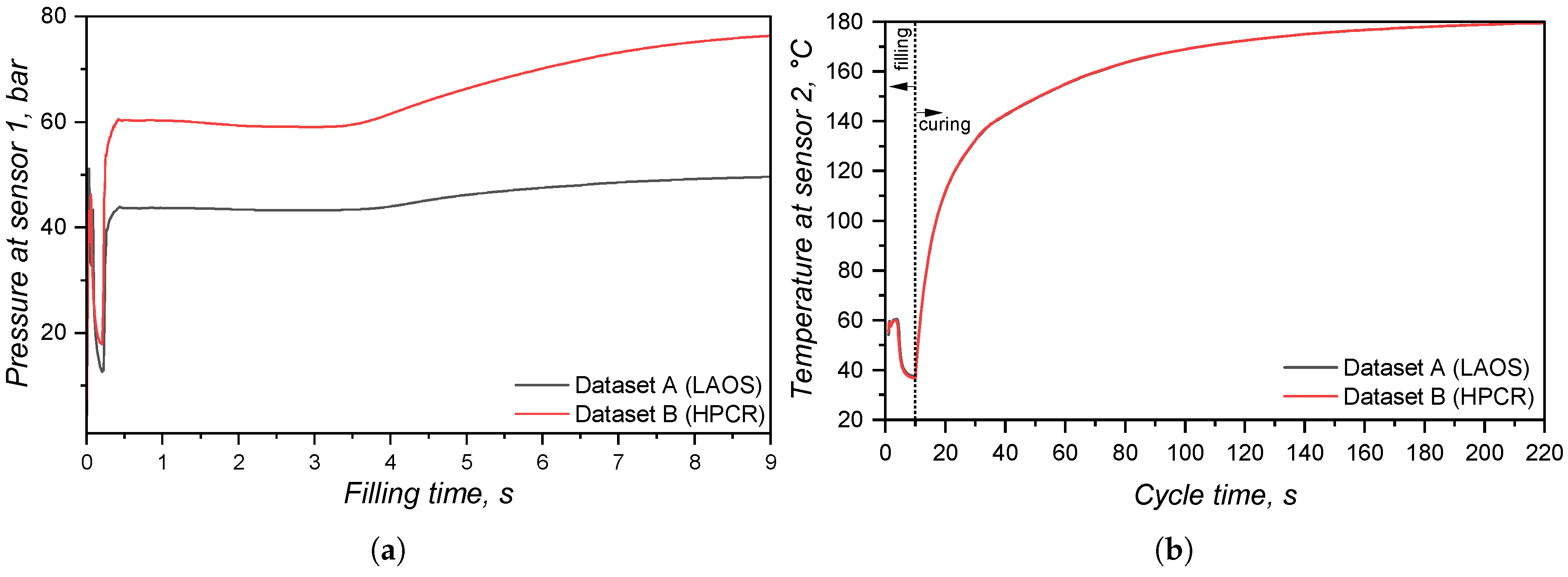

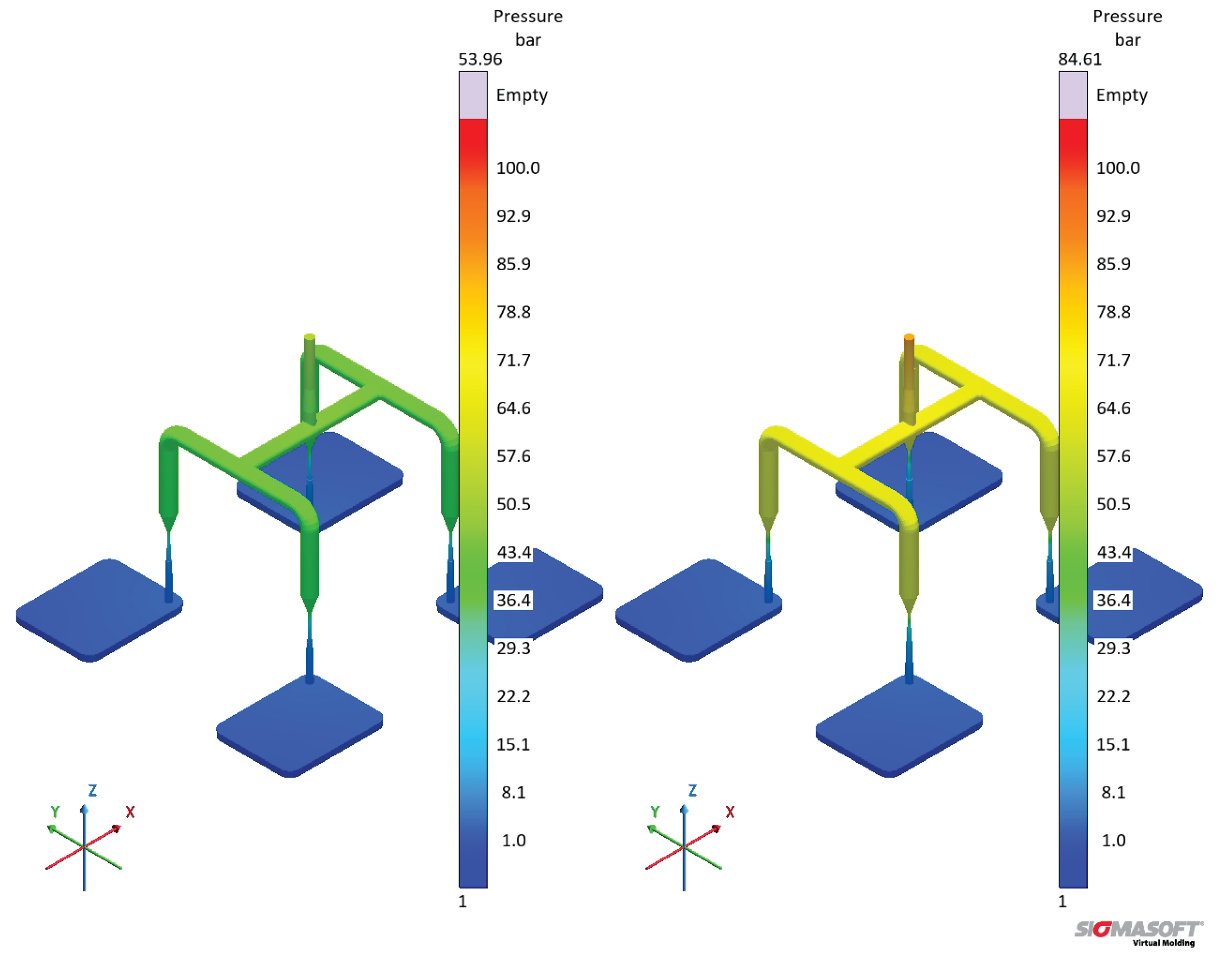

3.5.1. Viscosity Datasets A and B

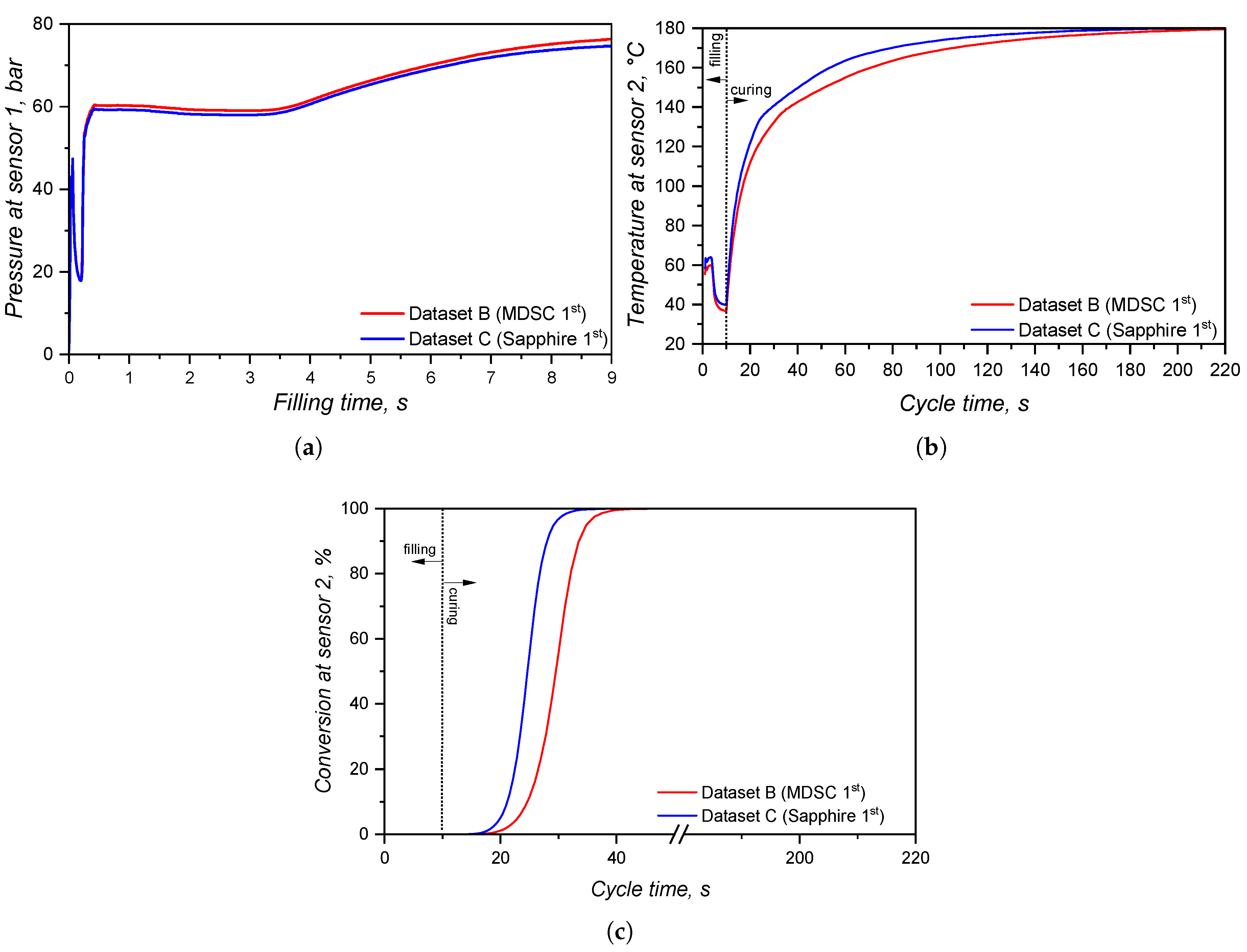

3.5.2. Specific Heat Capacity Datasets Comparisons

3.5.3. Curing Kinetics Datasets B and E

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitsoulis, E. Computational Polymer Processing. In Modeling and Simulation in Polymers; Gujrati, P.; Leonov, A., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH and Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; pp. 127–193.

- Matysiak, L.; Kornmann, X.; Saj, P.; Sekula, R. Analysis and Optimization of the Silicone Molding Process Based on Numerical Simulations and Experiments. Adv. Polym. Tech. 2012, 32, E258–E273. [CrossRef]

- García-Camprubí, M.; Alfaro-Isac, C.; Hernández-Gascón, B.; Valdés, J.; Izquierdo, S. Numerical Approach for the Assessment of Micro-Textured Walls Effects on Rubber Injection Moulding. Polymers 2021, 13, 1739. [CrossRef]

- Speight, R.; Costa, F.; Kennedy, P.; Friedl, C. Best practice for benchmarking injection moulding simulation. Plast. Rubber. Compos. 2013, 37, 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Haberstroh, E.; Michaeli, W.; Heize, E. Simulation of the Filling and Curing Phase in Injection Molding of Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR). Plast. Rubber. Compos. 2002, 21, 461–471.

- Capellmann, R.; Haberstroh, E.; Häuser, T.; Wehr, H. Development of simulation software for the injection moulding of liquid silicone rubber. Int. Polym. Sci. Tech. 2003, 30, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.; Sahli, M.; Barnière, T.; Gelin, J. Mutiphysics modelling and experimental investigations of the filling and curing phases of bi-injection moulding of thermoplastic polymer/liquid silicone rubbers. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 3871–3882. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, M.; Kerschbaumer, R.; Gerstbauer, F.; Sommer, M.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A.; Holzer, C. Rheological Insights: A Comparative Analysis of Viscosity Determination Techniques for Liquid Silicone Rubber Injection Moulding Simulation. Preprint SSRN 2025, 1, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- ASTM. Standard test method for determining specific heat capacity by differential scanning calorimetry. Standard ASTM E1269-(2011), American Society for Testing and Materials, 2011.

- Reading, M.; Luget, A.; Wilson, R. Modulated differential scanning calorimetry. Thermochim. Acta 1994, 238, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Kinshott, I.; Reading, M.; Lacey, A.; Nikolopoulos, C.; Pollock, H. The origin and interpretation of the signals of MTDSC. Thermochim. Acta 1997, 304/305, 187–199. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, I.; Montserrat, S.; Hutchinson, J. TOPEM, a new temperature modulated DSC technique - Application to the glass transition of polymers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 87, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J.; Fideu, P.; Herrmann, A.; Stark, W. Determination and review of specific heat capacity measurements during isothermal cure of an epoxy using TM-DSC and standard DSC techniques. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 759–765. [CrossRef]

- Stark, W.; Jaunich, M.; McHugh, J. Cure state detection for pre-cured carbon-fibre epoxy prepreg (CFC) using Temperature-Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (TMDSC). Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 1261–1272. [CrossRef]

- Kerschbaumer, R.; Stieger, S.; Gschwandl, M.; Hutterer, T.; Fasching, M.; Lechner, B.; Meinhart, L.; Hildenbrandt, J.; Schritesser, B.; Fuchs, P.; et al. Comparison of steady-state and transient thermal conducitivity testing methods using different industrial rubber compounds. Polym. Test. 2019, 80, 106121. [CrossRef]

- ASTM. Standard test method for thermal conductivity of plastics by means of a transient line-source technique. Standard ASTM D5930-(2019), American Society for Testing and Materials, 2019.

- ASTM. Standard test method for evaluating the resistance to thermal transmission of materials by guarded heat flow meter technique. Standard ASTM E1530-(2006), American Society for Testing and Materials, 2006.

- Wang, J., Some Critical Issues for Injection Moulding; InTech: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/33643, 2012; chapter PVT Properties of Polymers for Injections Molding, pp. 3–30.

- Azevedo, M.; Monks, A.M.; Kerschbaumer, R.; Schlögl, S.; Holzer, C. Peroxide-Based Crosslinking of Solid Silicone Rubber, Part I: Insights into the Influence of Dicumylperoxide Concentration on the Curing Kinetics and Thermodynamics Determined by a Rheological Approach. Polymers 2022, 14, 4404. [CrossRef]

- Heinze, S.; Echtermeyer, A. A Practical Approach for Data Gathering for Polymer Cure Simulations. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2227. [CrossRef]

- Akahira, T.; Sunose, T. Method of determining activation deterioration constant of electrical insulating materials. Res. Rep. Chiba Inst. Technol. 1971, 16, 22–31.

- Starink, M. The determination of activation energy from linear heating rate experiments: a comparison of the accuracy of isoconversion methods. Thermochim. Acta 2003, 404, 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Bardelli, T.; Marano, C.; Vangosa, F. Polydimethylsiloxane crosslinking kinetics: A systematic study on Sylgard184 comparing rheological and thermal approaches. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 51013. [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.K.; Lee, S. Cure kinetics and modeling the reaction of silicone rubber. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 42–47. [CrossRef]

- Karami, Z.; Jazani, O.; Navarchian, A.; Saeb, M. Cure Kinetics of Silicone/Halloysite Nanotube Composites. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2020, 26, 548–565. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S. A time to search: finding the meaning of variable activation energy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 18643–18656. [CrossRef]

- Šesták, J. Šesták–Berggren equation: now questioned but formerly celebrated—what is right. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 1117–1121. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M. Thermoset characterization for moldability analysis. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1974, 14, 231––239. [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D. An Algorithm for Least-Squares Estimation of Nonlinear Parameters. J. Soc. Indust. App. Math. 1963, 11, 431–441. [CrossRef]

- Traintinger, M. Produkt-adaptive Regelung des Kautschukspritzgießens. PhD thesis, Leoben, Austria, 2022.

- Van Assche, G.; Van Hemelrijck, A.; Rahier, H.; Van Mele, B. Modulated differential scanning calorimetry: isothermal cure and vitrification of thermosetting systems. Thermo. Acta 1995, 268, 121–142. [CrossRef]

- Vera-Graziano, R.; Hernandez-Sanchez, F.; Cauich-Rodriguez, J. Study of Crosslinking Density in Polydimethylsiloxane Networks by DSC. J. App. Polym. Sci. 1995, 55, 1317–1327. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, Y.; Qian, B.; Gao, H.; Zuo, D. Experimental study on mechanical performance of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) at various temperatures. Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106670. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Zamudío, M.; Villegas, A.; González-Calderón, J.; Meléndrez, R.; Meléndez-Lira, M.; Cervantes, J. Study of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Elastomer Generated by Gammna Irradiation: Correlation Between Properties (Thermal and Mechanical) and Structure (Crosslink Density Value). J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2017, 27, 622–632. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Shi, C.; Li, M. Flow Performance and Its Effect on Shape Formation in PDMS Assisted Thermal Reflow Process. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8282. [CrossRef]

- Bicerano, J. Prediction of Polymer Properties, 3 ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: United States of America, 2002.

- Azevedo, M.; Monks, A.M.; Kerschbaumer, R.; Schlögl, S.; Saalwächter, K.; Walluch, M.; Consolati, G.; Holzer, C. Peroxide-based crosslinking of solid silicone rubber, part II: The counter-intuitive influence of dicumylperoxide concentration on crosslink effectiveness and related network structure. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54111. [CrossRef]

- Rafei, M.; Ghoreishy, M.; Naderi, G. Development of an advanced computer simulation technique for the modeling of rubber curing process. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 47, 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Enhancement of thermal conductivity and tensile strength of liquid silicone rubber by threedimensional alumina network. Soft Mater. 2019, 17, 297–307. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Momen, G.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; David, E. Enhancement in electrical and thermal performance of high-temperature vulcanized silicone rubber composites for outdoor insulating applications. J. App. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, e49514. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.C.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Liu, W.R. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Silicone Composites Filled with Few-Layered Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Polymers 2020, 12, 2072. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Liu, W.J.; Shen, F.X.; Zhang, G.D.; Gong, L.X.; Zhao, L.; Song, P.; Gao, J.F.; Tang, L.C. Processing, thermal conductivity and flame retardant properties of silicone rubber filled with different geometries of thermally conductive fillers: A comparative study. Compos. B Eng. 2022, 232, 109907. [CrossRef]

- van Krevelen, D. Properties of Polymers. Their Correlation with Chemical Structure, Their Numerical Estimation and Prediction from Additive Group Contributions, 3 ed.; Elsevier: Netherlands, 1990.

- Zhong, C.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W. Correlation and prediction of the thermal conductivity of amorphous polymers. Fluid Ph. Equilib. 2001, 181, 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Eiermann, K.; Hellwege, K.H. Thermal Conductivity of High Polymers from -180°C to 90°C. J. Polym. Sci. 1962, 57, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, X.G. Molecular dynamics simulation of thermal conductivity of silicone rubber. Chin. Phys. B 2020, 29, 046601. [CrossRef]

- Cheheb, Z.; Mousseau, P.; Sarda, A.; Deterre, R. Thermal Conductivity of Rubber Compounds Versus the State of Cure. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2012, 297, 228–236. [CrossRef]

- Bont, M.; Barry, C.; Johnston, S. A review of liquid silicone rubber injection molding: Process variables and process modeling. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2021, 61, 331–347. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hopmann, C.; Schmitz, M.; Hohlweck, T.; Wipperfürth, J. Modeling of pvT behavior of semi-crystalline polymer based on the two-domain Tait equation of state for injection molding. Mater. Des. 2019, 183, 108149. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, X. Autocatalytic curing kinetics of thermosetting polymers: A new model based on temperature dependent reaction orders. Polymer 2010, 51, 3841–3820. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortiz, J.; Osswald, T. Modeling Processing of Silicone Rubber: Liquid Versus Hard Silicone Rubbers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 119, 1864–1871. [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Chonggang, W.; Chen, X. Model-free cure kinetics of additional liquid silicone rubber. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 688, 178584. [CrossRef]

- Ziebell, R.; Bhogesra, H. LIM Simulation Modeling Using Newly Developed Chemorheological Methods. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Silicone Conference, May 2016.

- Jin, J.; Noordermeer, J.; Blume, A.; Dierkes, W. Effect of SBR/BR elastomer blend ratio on filler and vulcanization characteristics of silica filled tire tread compounds. Polym. Test. 2021, 99, 107212. [CrossRef]

- Harkous, A.; Colomines, G.; Leroy, E.; Mousseau, P.; Deterre, R. The kinetic behavior of Liquid Silicone Rubber: A comparison between thermal and rheological approaches based on gel point determination. React. Funct. Polym. 2016, 101, 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Weißer, D.; Shakeel, A.; Mayer, D.; Schmid, J.; Heienbrock, S.; Deckert, M.; Rapp, B. Gel point investigation of liquid silicone rubber using rheological approaches. Polymer 2023, 283, 126286. [CrossRef]

- Weißer, D.; Walz, D.; Schmid, J.; Mayer, D.; Deckert, M. Calculating the temperature and degree of cross-linking for liquid silicone rubber processing in injection molding. Adv. Manuf. Process. 2020, 3, e10072. [CrossRef]

- Lukin, R.; Kuchkaev, A.; Sukhov, A.; Bekmukhamedov, G.; Yakhvarov, D. Platinum-Catalyzed Hydrosilylation in Polymer Chemistry. Polymers 2020, 12, 2174. [CrossRef]

- Carreau, P. Rheological Equations from Molecular Network Theories. J. Rheol. 1972, 16, 99–127. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Armstrong, R.; Cohen, R. Shear flow properties of concentrated solutions of linear and star branched polystyrenes. Rheol. Acta 1981, 20, 163–178. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Landel, R.; Ferry, J. The Temperature Dependence of Relaxation Mechanisms in Amorphous Polymers and Other Glass-forming Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 3701–3707. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity | LAOS | HPCR | HPCR | HPCR | HPCR |

| MDSC 1st | MDSC 1st | sapphire 1st | sapphire 2nd | MDSC 1st | |

| cured sample | |||||

| pvT | As determined | ||||

| Curing | DSC | DSC | DSC | RPA |

| Sample | Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2070 A | 0.223 | 0.001 | 7% |

| 2070 B | 0.209 | 0.001 | 7% |

| A+B uncured | 0.211 | 5.0 | 7% |

| A+B cured | 0.186 | 0.002 | 5% |

| Parameter | DSC | 0.4383 | 4.383 | 13.1476 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| , | ||||

| , | ||||

| , kJ. | 193.6 | 171.3 | 158.9 | 178.3 |

| , kJ. | 100.9 | 133.9 | 134.1 | 102.2 |

| m | 1.52 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.84 |

| n | 1.24 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Parameter | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| , Pa.s | 0.0248 | 0.00917 |

| , Pa.s | 22.75 | 8.0 |

| a, - | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| n, - | 0.103 | 0.368 |

| , s | 12.64 | 12.0 |

| , °C | 72.0 | 72.0 |

| , °C | -273.0 | -103.22 |

| Parameter | B | E |

|---|---|---|

| log(), | 24.03 | 5.00 |

| log(), | 12.69 | 17.13 |

| , kJ. | 193.6 | 171.3 |

| , kJ. | 100.9 | 133.9 |

| m, - | 1.52 | 0.73 |

| n, - | 1.24 | 3.00 |

| Enthalpy, kJ. | 8.15 | 8.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).