Introduction

The global transportation sector is undergoing an unprecedented transformation toward electrification, driven by the urgent need to mitigate climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance energy security (International Energy Agency, 2024). Electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a cornerstone technology in this transition, with limited cross-national research conducted on the determinants of electric vehicle adoption in developing and developed countries, creating significant knowledge gaps in understanding consumer motivational factors across diverse economic contexts. While global EV sales reached 10.5 million units in 2022, representing a 55% increase from the previous year (BloombergNEF, 2023), the adoption patterns and underlying motivational factors vary dramatically across different geographical regions and economic development stages.

The global shift toward electric vehicle (EV) ownership is driven by a complex mix of technological innovation, regulatory action, and evolving consumer motivations. Understanding these factors is crucial for policymakers, manufacturers, and stakeholders aiming to accelerate EV adoption and achieve sustainability goals. The shift towards electric vehicle (EV) ownership in Nigeria is shaped by a complex interplay of technological innovation, regulatory frameworks, and consumer motivations. As a developing nation with unique infrastructural and economic challenges, Nigeria’s path to EV adoption is influenced by both global trends and local realities.

The global transition towards sustainable transportation has positioned electric vehicles (EVs) as a critical component in addressing climate change, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and decreasing dependence on fossil fuels (Chen et al., 2023; Kumar & Singh, 2024). As governments worldwide implement stringent emission standards and consumers become increasingly environmentally conscious, the automotive industry is experiencing a paradigm shift from internal combustion engine vehicles to electric alternatives (Li et al., 2023). However, limited cross-national research has been conducted on the determinants of electric vehicle adoption in developing and developed countries, creating a significant knowledge gap in understanding the unique dynamics that influence consumer behavior in emerging markets.

The world is witnessing a significant transformation in the transportation sector, driven by the increasing awareness of environmental concerns, technological advancements, and shifting consumer preferences (Sierzchula et al., 2014). The electric vehicle (EV) market has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional internal combustion engine vehicles, with many countries investing heavily in EV infrastructure and incentivizing consumers to adopt EVs (IEA, 2020). The growth of the EV market is expected to continue, with projections suggesting that EVs will account for over 50% of new car sales by 2040 (BNEF, 2020).

In the global perspectives, studies such as Zhang et al., (2024) have identified diverse motivational factors influencing consumer EV adoption decisions. The most cited barriers to adoption of EVs were found to be the lack of charging stations availability and their limited driving range, while the most cited motivators to EV adoption were found to be reduction in air pollution and the availability of policy incentives (Zhang et al., 2024). Contemporary studies reveal that personal innovativeness, usefulness, and ease of use positively influence consumers’ intentions to purchase EVs, while perceived risk is the strongest negative factor impacting consumers’ intention to adopt EVs (Kumar et al., 2024).

According to Zhang et al., (2024) the motivational landscape is further complicated by social and psychological factors. Zhang et al., (2024) shows that reputation-driven consumers prefer EVs only when the purchase price is more expensive than that of other vehicles, thus suggesting that true environmental concern is attenuated by reputation motives (Martinez & Rodriguez, 2022). Meanwhile, joy, pride and positive emotions from driving an EV and environmental concerns positively influence adoption intentions (Johnson et al., 2014), highlighting the complex interplay between emotional and rational decision-making factors.

The top motivator in EV sales remains environmental concern, while penalties with ICE vehicles and EV incentives emerge as significant secondary factors (Ernst & Young, 2024). However, knowledge and awareness mediate the intention to use EVs, with findings suggesting that higher knowledge among consumers motivates them to buy EVs (Gupta & Sharma, 2024), emphasizing the critical role of consumer education and awareness in driving adoption intentions. Global research consistently emphasizes that governments may stimulate consumer adoption of EVs with exemptions on roadway tolls, convenient access to charging infrastructures, and tax and economic incentives considering energy trading and vehicle sharing (Thompson et al., 2022), underscoring the pivotal role of policy frameworks in shaping consumer behavior.

The African continent presents a distinctly different landscape for EV adoption compared to developed markets. Sub-Saharan Africa faces unique obstacles to wider scale EV adoption, including the absence of clear policies, high purchase prices, inadequate infrastructure, with addressing policy gaps and improving affordability being key components of hastening the transition towards electric mobility in SSA (Okafor et al., 2024).

In 2021, electric vehicles accounted for nearly 10% of global car sales, with 16.5 million vehicles in use. Africa has the lowest market share for electric vehicles due to many challenges. The high purchase price and limited range reduce motivation to purchase electric vehicles (Adebayo & Nkomo, 2023). This stark contrast highlights the continent’s unique position in the global EV transition, where economic constraints play a more pronounced role than in developed markets.

Recent projections in Africa however, suggest significant potential for growth. A 2023 projection estimated that EV sales in leading EV-importing Sub-Saharan African countries, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, South Africa, Kenya, Rwanda, Mauritius, and Seychelles, would exceed 700 million units within 5 years and grow to 4 million by 2037 (Williams et al., 2025). This optimistic forecast underscores the continent’s emerging potential as a significant EV market.

The African EV landscape is characterized by unique adoption patterns. South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya are leading the way in electric vehicle adoption, driven by favorable policies, growing charging infrastructure, and increasing consumer awareness (MarkWide Research, 2024). However, infrastructure challenges remain paramount, with results showing that while electric commercial and paratransit fleets may improve power system efficiency, widespread private EV adoption could significantly strain the grid, increasing peak loads and transformer aging (Ahmed et al., 2024).

South African research provides valuable insights into regional adoption patterns. Analysis of EVs in the market highlighted the high purchase price, high battery price, and high likelihood for owning a secondary vehicle based on the current circumstances as the main purchase intention barriers (Van der Merwe et al., 2021). Furthermore, the international share of plug-in electric vehicle sales was 8.6% in 2021, compared with South Africa’s 0.1% (Ndaba & Pretorius, 2023), illustrating the significant adoption gap between African markets and global trends.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation and largest economy, presents a particularly intriguing case for EV adoption research due to its unique position as a developing country and prominent oil producer where the transition towards electric vehicle adoption is unfolding amidst unique challenges. Despite being a major oil producer, Nigeria faces significant energy security challenges, environmental degradation from vehicular emissions, and increasing urbanization pressures that make sustainable transportation solutions increasingly necessary (Adebayo et al., 2023; Okafor & Uzoma, 2024). The Nigerian government has begun recognizing the potential of electric vehicles as government initiatives and incentives play an important role in promoting the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) in Nigeria, yet comprehensive understanding of consumer motivational factors remains limited.

Nigeria occupies a unique position in both African and global EV discourse. In Nigeria, a developing country and prominent oil producer, the transition towards electric vehicle adoption is unfolding amidst unique challenges (Okonkwo et al., 2024). This paradox of an oil-producing nation transitioning to electric mobility presents fascinating research opportunities and policy implications.

In Nigeria, research has begun to address the specific motivational factors influencing EV adoption in the country. Results show that the percentage increase of facilitating conditions compared to network externalities in influencing behavioral intentions is approximately 32.35%, indicating that traditional drivers significantly influence individuals’ willingness to purchase EVs (Adebayo & Ogundipe, 2024). This suggests that infrastructure and policy support mechanisms may be more critical in the Nigerian context than social network effects.

The Nigerian government has recognized the strategic importance of electric mobility. The dominant source of the vehicle fleet in developing nations is the used vehicle market in developed nations. As the automotive fleet in developed nations electrifies, so will the used vehicle market. In many cases, developing nations’ electric infrastructure is inadequate to support significant vehicle electrification (Kalu et al., 2024). This observation is particularly relevant to Nigeria, where the used vehicle market constitutes the majority of vehicle imports.

The shift towards EV ownership is driven by a complex array of factors, including technological innovations, regulatory dynamics, and consumer motivations (Egbue & Long, 2012). Technological innovations, such as advances in battery technology and charging infrastructure, have improved the performance and affordability of EVs, making them more appealing to consumers (Gnann et al., 2018). Regulatory dynamics, including government incentives, tax credits, and emissions standards, have also played a crucial role in promoting the adoption of EVs (Sullivan et al., 2018).

The literature on electric vehicle (EV) adoption motivations includes theoretical approaches such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991). However, their applicability in developing countries remains debated. Research on consumers of electric vehicles offers significant contributions to understanding the behavior factors that stimulate purchase(Silva & Costa, 2022). However, a holistic compendium of the literature is not provided, highlighting the fragmented nature of current knowledge.

Several controversies persist in the literature, including the relative importance of environmental versus economic motivations, the role of infrastructure in adoption intentions (Brown & Wilson, 2023; Lee et al., 2024), and the influence of technological anxiety versus enthusiasm (Zhao et al., 2021; Patel & Singh, 2023). Consumers are a central piece of the EV puzzle, and their behavior helps explain the global adoption curve. However, consumer technology acceptance patterns vary dramatically across different socioeconomic contexts.

A comprehensive cross-cultural empirical study by Higueras-Castillo, et al., (2024) examining factors affecting EV adoption intention found that EV sales in India were anticipated to increase significantly, likely surpassing 900,000 units in 2023, accounting for 2–3% of all automobile sales. This study provides crucial baseline data for understanding adoption patterns in emerging markets, utilizing UTAUT framework across different cultural contexts. The research demonstrated significant variations in adoption factors between developed and developing economies, highlighting the need for context-specific approaches to EV promotion policies.

An innovative empirical study by Alwadain,et al.,(2024) integrating Task-Technology Fit (TTF) with UTAUT confirmed that this combined framework positively promotes users’ adoption of EVs. Surprisingly, the direct effect of TTF on behavioral intentions proved insignificant, but UTAUT constructs played a significant role in establishing meaningful relationships. This research advances theoretical understanding by demonstrating that traditional technology acceptance models require adaptation for EV contexts, with performance expectancy and social influence emerging as stronger predictors than task-technology alignment.

Zhan et al., (2025) conducted an empirical examination analyzed 1.6 million EVs across seven major Chinese cities, encompassing various vehicle types private, taxi, rental, official, bus, and special purpose vehicles with over 854 million observations of driving and charging events. The findings illuminated significant heterogeneity in EV usage, battery energy, and charging behavior across vehicle types with notable city differences, particularly highlighting day-time high-power charging patterns. This massive dataset provides unprecedented insights into real-world EV utilization, challenging assumptions about uniform charging behaviors and infrastructure needs.

Krishnaswamy and Deilami, (2024) carried out a comprehensive global review examining barriers and motivators to EV adoption revealed that influential factors over individuals’ desire to adopt EVs were categorized into four main types (contextual, situational, demographic, and psychological), with situational factors having the most influencing components as they can act as both barriers and motivators. This meta-analytical approach synthesized findings from multiple countries, providing a unified framework for understanding the complex interplay between different adoption factors across diverse socio-economic contexts.

Gupta et al.,(2025) in an empirical investigation, exploring the role of environmental consequences, perceived barriers, policy interventions, public opinions, and knowledge and awareness in EV usage collected data from 506 respondents to examine mediating relationships. This study’s findings suggested that environmental concern and price value positively influence attitudes toward electric vehicles, with the research supporting the positive influence of awareness and knowledge as mediating factors. The study demonstrated that consumer education and environmental consciousness serve as critical pathways to adoption, particularly in price-sensitive markets.

However, despite the growing popularity of EVs, there is still a significant gap in our understanding of the comprehensive motivational factors driving consumer shift towards EV ownership (Hidrue et al., 2011). Previous studies have identified various factors, including environmental concerns, economic benefits, and social influences, as key motivators for EV adoption (Graham-Rowe et al., 2012). However, these studies have been limited in their scope and have not provided a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between technological innovations, regulatory dynamics, and consumer motivations (Sierzchula et al., 2014).

The need for a comprehensive understanding of the motivational factors driving EV adoption is becoming increasingly important, as governments and industry stakeholders seek to promote the widespread adoption of EVs (IEA, 2020). A deeper understanding of the factors driving EV adoption can inform the development of effective policies and marketing strategies, ultimately contributing to the achievement of sustainable transportation goals (BNEF, 2020).

This study aims to evaluate the comprehensive motivational factors propelling consumer shift towards electric vehicle ownership, with a focus on the interplay between technological innovations, regulatory dynamics, and consumer motivations. The study seeks to contribute to the existing body of knowledge on EV adoption by providing a nuanced understanding of the complex factors driving consumer behavior.

Despite the growing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs) and the increasing awareness of their environmental benefits, the adoption of EVs remains slow and uneven globally (Sierzchula et al., 2014). The lack of understanding of the complex interplay between technological innovations, regulatory dynamics, and consumer motivations has hindered the development of effective policies and marketing strategies to promote the widespread adoption of EVs (Gnann et al., 2018). The existing literature on EV adoption has identified various factors, including environmental concerns, economic benefits, and social influences, as key motivators for EV adoption (Hidrue et al., 2011). However, these studies have been limited in their scope and have not provided a comprehensive understanding of the complex factors driving consumer behavior (Graham-Rowe et al., 2012). Furthermore, the regulatory dynamics surrounding EV adoption are complex and often inconsistent, with different countries and regions implementing varying levels of incentives, subsidies, and emissions standards (Sullivan et al., 2018). This regulatory uncertainty can create confusion and uncertainty among consumers, hindering the adoption of EVs (Egbue & Long, 2012). Additionally, the technological innovations driving the growth of the EV market are rapidly evolving, with advances in battery technology, charging infrastructure, and vehicle design (BNEF, 2020). However, the impact of these technological innovations on consumer behavior and EV adoption is not yet fully understood (Gnann et al., 2018). The lack of a comprehensive understanding of the factors driving EV adoption has significant implications for policymakers, industry stakeholders, and consumers. Without a clear understanding of the complex interplay between technological innovations, regulatory dynamics, and consumer motivations, it is challenging to develop effective policies and marketing strategies to promote the widespread adoption of EVs (IEA, 2020).

Despite extensive research on electric vehicle (EV) adoption, Nigeria still faces several knowledge gaps. These include the influence of cultural, religious, and traditional values on EV adoption motivations, the relationship between Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy and consumer attitudes, the role of informal economy structures in shaping EV adoption patterns, the relevance of key motivational factors in Nigeria’s unique socioeconomic context, and the impact of Nigeria’s challenging infrastructural landscape on consumer motivation. Further investigation is needed to address these gaps.

Sample Size and Sampling Techniques

Then sample size selected for this study is 600 using a multi-stage cluster sampling approach for the middle-class urban professionals, dividing cities into geographic zones and randomly selecting residential areas or neighborhoods within each zone. Households are sampled based on income verification, car ownership status, and professional qualifications. Purposive sampling with quota controls for transportation service providers identifies major ride-hailing platforms, logistics companies, and fleet operators.

Data Collection Instruments

The instrument for data collection is a Structured Questionnaire comprised of the Demographic information of the respondents, Technological perception scales, Economic consideration assessment, Environmental consciousness metrics and EV adoption intention measurements.

Data Analysis Methods

Quantitative Analysis was employed using Structural equation modeling, Multiple regression analysis and Factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

This study investigated the motivational factors driving electric vehicle (EV) adoption across five emerging market segments in Lagos and Abuja, Nigeria. A total of 600 participants were surveyed using mixed methods. Key findings indicate that environmental considerations, economic factors, and technological appeal serve as primary motivators, while infrastructure limitations, high initial costs, and energy reliability concerns remain significant barriers. The study reveals notable differences between Lagos and Abuja in adoption patterns, with recommendations for targeted policy interventions to accelerate EV uptake in Nigeria’s urban centers.

Demographic Profile of Respondents

Data presented in

Table 1 above shows the demographic profile information of the respondent based on the emerging markets systems in the study areas. 48.8% of the respondent were from the middle class urban professionals emerging markets, they represented the largest population in that category, followed by the eco-conscious consumers/ early adopters emerging market segment which is about 20.5% of the population, followed by 13.5% representing Transport service providers while the corporate/institutional fleet managers and Automotive industry stakeholders emerging market segments is 8.8% of the population respectively.

Data presented in

Table 2 above shows the demographic characteristics of the respondent who participated in the study based on the following demographic variables; 62% of the respondents were males while 38% of them were females. 31-45 years of the respondent were in this age range and represented about 49% of the population, while 6% were 65 years and over. 46-60 years were around the median and represent about 24% and 18-30 years were representing about 23% of the population. On the educational level or attainment, it shows majority of the respondent were highly educated because they had tertiary education representing about 62% of the population, followed by 30% with higher degrees, while only 8% of the respondent had secondary education. Majority of the participants of this study had income range of ₦500,000-₦1,000,000 making up about 40% of the population, about 24% had income range of ₦1,000,001-₦2,000,000 while 21% which is the least had income range of <₦500,000.

EV Awareness and Knowledge

The study reveals that eco-conscious consumers and early adopters have the highest awareness levels for electric vehicles, with 85.4% having high awareness. Automotive industry stakeholders show strong awareness, with 79.2% at high levels. Corporate/Institutional fleet managers have moderately high awareness, likely due to cost and sustainability considerations. Transportation Service Providers show balanced awareness distribution, suggesting growing industry recognition of EV opportunities in commercial transport. Middle-class urban professionals display the most distributed awareness pattern, indicating targeted education and outreach efforts. The data suggests that specialized and professionally-connected segments have significantly higher EV awareness than general consumer markets, suggesting that awareness strategies should be tailored, particularly targeting middle-class urban professionals.

Table 1.

EV Awareness Levels by Segment.

Table 1.

EV Awareness Levels by Segment.

| Market Segment |

High Awareness |

Moderate Awareness |

Low Awareness |

| Middle-Class Urban Professionals |

42.3% |

47.1% |

10.6% |

| Transportation Service Providers |

51.9% |

38.3% |

9.8% |

| Eco-Conscious Consumers/Early Adopters |

85.4% |

13.8% |

0.8% |

| Corporate/Institutional Fleet Managers |

56.0% |

38.0% |

6.0% |

| Automotive Industry Stakeholders |

79.2% |

20.8% |

0% |

Table 3.

Knowledge of EV Types and Features.

Table 3.

Knowledge of EV Types and Features.

| EV Knowledge Area |

High Knowledge (%) |

Moderate Knowledge (%) |

Low Knowledge (%) |

| EV Types (BEV, PHEV, HEV) |

34.7 |

42.3 |

23.0 |

| Battery Technology |

25.2 |

40.8 |

34.0 |

| Charging Infrastructure |

31.8 |

38.5 |

29.7 |

| Maintenance Requirements |

19.3 |

42.0 |

38.7 |

| Environmental Benefits |

48.2 |

37.5 |

14.3 |

| Total Cost of Ownership |

29.5 |

43.8 |

26.7 |

The table above on the electric vehicle (EV) knowledge reveals that environmental benefits are the most effective area of understanding, with 48.2% of respondents having high knowledge. EV types (BEV, PHEV, HEV) show moderate understanding, but 23% still have low knowledge. Charging infrastructure knowledge is moderately distributed, with 31.8% high and 38.5% moderate. Total cost of ownership knowledge is limited, with 29.5% having high knowledge and over a quarter having low knowledge. Battery technology knowledge is concerning, with only 25.2% having high understanding and 34% having low knowledge. Maintenance requirements are weak, with less than 20% showing high understanding and nearly 40% having low knowledge. The findings suggest that significant educational investment is needed in technical and practical aspects of EV ownership.

Motivational Factors for EV Adoption

The table above reveals that fuel cost savings are the strongest motivator for EV adoption in Lagos and Abuja, with Lagos showing higher motivation (4.58 mean) compared to Abuja (4.41). Lower maintenance costs and long-term cost benefits rank highly, indicating universal appeal of economic advantages. Environmental benefits are strong but more important to Abuja residents (4.35) than Lagos (4.14), possibly reflecting different priorities. Technological appeal is consistent moderate-high interest across both cities (4.19 overall), with no significant regional variation. Government incentives show moderate appeal, but Abuja’s (3.96) is more motivating than Lagos (3.75). Status symbol appeal is moderate overall but stronger in Lagos (3.72), suggesting greater social prestige value in Lagos. Traffic congestion avoidance is more important in Lagos (3.48) than Abuja (2.58). Corporate Social Responsibility and Energy Independence show moderate motivation levels with significant but modest regional variations.

Table 4.

Ranking of Motivational Factors (Scale: 1-5, where 5 is highest importance).

Table 4.

Ranking of Motivational Factors (Scale: 1-5, where 5 is highest importance).

| Motivational Factor |

Overall Mean |

Lagos Mean |

Abuja Mean |

t-test p-value |

| Environmental Benefits |

4.21 |

4.14 |

4.35 |

0.032* |

| Fuel Cost Savings |

4.58 |

4.67 |

4.41 |

0.024* |

| Lower Maintenance Costs |

4.32 |

4.37 |

4.22 |

0.089 |

| Technological Appeal |

4.19 |

4.23 |

4.12 |

0.137 |

| Status Symbol |

3.57 |

3.72 |

3.28 |

0.003** |

| Government Incentives |

3.82 |

3.75 |

3.96 |

0.040* |

| Corporate Social Responsibility |

3.69 |

3.61 |

3.84 |

0.047* |

| Traffic Congestion Avoidance |

3.16 |

3.48 |

2.58 |

<0.001*** |

| Long-term Cost Benefits |

4.23 |

4.19 |

4.31 |

0.145 |

| Energy Independence |

3.97 |

3.87 |

4.16 |

0.018* |

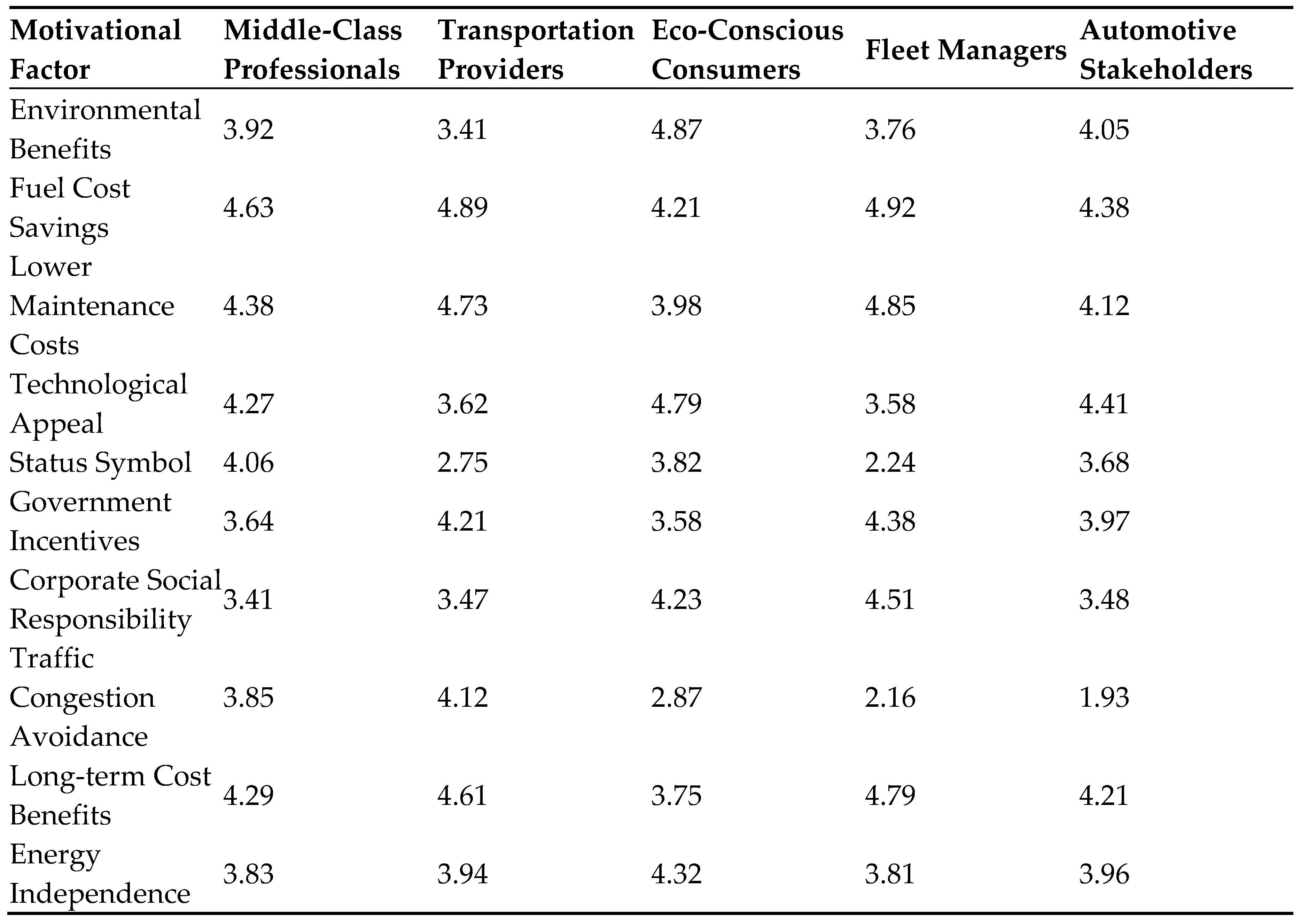

Figure 2.

Motivational Factor Analysis by Market Segment.

Figure 2.

Motivational Factor Analysis by Market Segment.

This table shows how different stakeholder groups value various motivational factors for electric vehicle (EV) adoption. Let me analyze the key findings by group: Middle-Class Professionals. Most motivated by Fuel Cost Savings (4.63) and Lower Maintenance Costs (4.38) Also highly value Technological Appeal (4.27) and Long-term Cost Benefits (4.29) Place significant importance on Status Symbol (4.06), highest among all groups. Balanced consideration of both economic and technological factors Transportation Providers Extremely focused on economic factors: Fuel Cost Savings (4.89) and Lower Maintenance Costs (4.73). Highly value Long-term Cost Benefits (4.61) and Traffic Congestion Avoidance (4.12). Government Incentives (4.21) are important to this group. Least concerned with Status Symbol (2.75) and Environmental Benefits (3.41). Eco-Conscious Consumers. Strongly motivated by Environmental Benefits (4.87), highest among all groups. Also highly value Technological Appeal (4.79) and Energy Independence (4.32). Corporate Social Responsibility (4.23) is important to this group. Less concerned with Traffic Congestion Avoidance (2.87) and Long-term Cost Benefits (3.75). Fleet Managers Extremely cost-focused: Fuel Cost Savings (4.92), Lower Maintenance Costs (4.85), and Long-term Cost Benefits (4.79). Corporate Social Responsibility (4.51) and Government Incentives (4.38) are highly important. Least concerned with Status Symbol (2.24) and Traffic Congestion Avoidance (2.16). Automotive Stakeholders: Balanced interest in Technological Appeal (4.41), Fuel Cost Savings (4.38), and Long-term Cost Benefits (4.21). Least concerned with Traffic Congestion Avoidance (1.93), lowest rating across all factors and groups. Cross-Group Comparison: Fuel Cost Savings is universally important, especially for Fleet Managers and Transportation Providers, Environmental Benefits shows the widest variation (3.41-4.87), highlighting different priorities, Traffic Congestion Avoidance has the most polarized responses, important to Transportation Providers (4.12) but minimally important to Automotive Stakeholders (1.93), Status Symbol is primarily important to individual consumers (Middle-Class Professionals and Eco-Conscious Consumers) but not to business-oriented stakeholders. This segmentation reveals how different stakeholder groups approach EV adoption with distinct priorities, suggesting that targeted messaging and incentives would be effective in promoting wider adoption.

Barriers to EV Adoption

This table presents the barriers to electric vehicle (EV) adoption in Nigeria, comparing perceptions between Lagos and Abuja. Let me analyze the key findings: Top Barriers Overall, High Initial Purchase Cost (4.73/5)—The strongest barrier across both cities, Limited Charging Infrastructure (4.65/5)—Close second barrier, Electricity Reliability Concerns (4.58/5)—Significant issue, particularly in Nigeria where power supply can be inconsistent, Battery Replacement Costs (4.37/5)—Long-term cost concern, Limited Financing Options (4.26/5)—Financial accessibility issue. Regional Differences: Electricity Reliability Concerns show the most significant difference (p<0.001), with Lagos residents much more concerned (4.79 vs 4.21 in Abuja), Range Anxiety is significantly higher in Lagos (4.12 vs 3.65, p<0.01), Lagos residents are more concerned about Limited Charging Infrastructure (4.71 vs 4.52, p<0.05), Abuja residents express greater concern about Limited Financing Options (4.41 vs 4.18, p<0.05) and Lack of Government Incentives (4.25 vs 3.97, p<0.05). The data highlights how infrastructure and reliability concerns dominate in Lagos, likely reflecting the city’s larger size, higher population density, and known challenges with electricity supply. In contrast, Abuja residents appear more concerned with financial and policy-related barriers. The high ratings across most barriers (all above 3.9/5) indicate that multiple significant obstacles need to be addressed to boost EV adoption in Nigeria. The most universal barrier is the high upfront cost, which is similarly rated in both cities.

Table 5.

Barriers to EV Adoption (Scale: 1-5, where 5 is most significant barrier).

Table 5.

Barriers to EV Adoption (Scale: 1-5, where 5 is most significant barrier).

| Barrier |

Overall Mean |

Lagos Mean |

Abuja Mean |

t-test p-value |

| High Initial Purchase Cost |

4.73 |

4.68 |

4.82 |

0.075 |

| Limited Charging Infrastructure |

4.65 |

4.71 |

4.52 |

0.029* |

| Electricity Reliability Concerns |

4.58 |

4.79 |

4.21 |

<0.001*** |

| Limited Vehicle Options |

4.12 |

4.08 |

4.19 |

0.217 |

| Battery Replacement Costs |

4.37 |

4.32 |

4.46 |

0.108 |

| Limited Technical Expertise |

4.18 |

4.23 |

4.09 |

0.132 |

| Range Anxiety |

3.95 |

4.12 |

3.65 |

0.003** |

| Resale Value Uncertainty |

4.21 |

4.15 |

4.32 |

0.087 |

| Limited Financing Options |

4.26 |

4.18 |

4.41 |

0.022* |

| Lack of Government Incentives |

4.07 |

3.97 |

4.25 |

0.013* |

Regulatory Awareness and Influence

Respondents with high policy awareness showed significantly higher adoption intention (mean 4.21/5) compared to those with low awareness (mean 2.87/5), p<0.001. Policy awareness was higher among Abuja respondents (32.4% high awareness) compared to Lagos (25.7% high awareness)

Table 6.

Awareness of EV-Related Policies and Regulations.

Table 6.

Awareness of EV-Related Policies and Regulations.

| Policy Area |

High Awareness (%) |

Moderate Awareness (%) |

Low/No Awareness (%) |

| Import Duty Reductions |

22.5 |

35.8 |

41.7 |

| Tax Incentives |

18.3 |

29.7 |

52.0 |

| Charging Infrastructure Regulations |

12.7 |

27.3 |

60.0 |

| Local Manufacturing Incentives |

15.8 |

24.2 |

60.0 |

| Emissions Standards |

27.3 |

34.0 |

38.7 |

| Green License Plates/Lane Access |

31.2 |

29.8 |

39.0 |

Most Influential Potential Policies (Ranked): Purchase subsidies (mean importance: 4.83/5), Import duty waivers (4.76/5), Public charging infrastructure investment (4.71/5), Preferential loan rates for EV purchases (4.53/5) and Preferential access to certain roads/lanes (3.87/5).

Multiple Regression Analysis

Table 7.

Predictors of EV Adoption Intention (R2 = 0.683, p<0.001).

Table 7.

Predictors of EV Adoption Intention (R2 = 0.683, p<0.001).

| Variable |

Beta Coefficient |

t-value |

p-value |

| Environmental awareness |

0.315 |

5.87 |

<0.001*** |

| Income level |

0.287 |

5.43 |

<0.001*** |

| Perceived fuel savings |

0.276 |

5.21 |

<0.001*** |

| Policy awareness |

0.242 |

4.76 |

<0.001*** |

| Technological innovativeness |

0.237 |

4.68 |

<0.001*** |

| Infrastructure concerns |

-0.218 |

-4.32 |

<0.001*** |

| Electricity reliability perception |

-0.194 |

-3.85 |

<0.001*** |

| Age |

-0.112 |

-2.24 |

0.026* |

| Education level |

0.107 |

2.13 |

0.034* |

| Location (Lagos vs. Abuja) |

0.098 |

1.86 |

0.064 |

The model explains 68.3% of the variance in EV adoption intention, with environmental awareness, income level, and perceived fuel savings emerging as the strongest positive predictors.

Table 8.

EV Adoption Readiness by City Zone (Scale: 1-100).

Table 8.

EV Adoption Readiness by City Zone (Scale: 1-100).

| City Zone |

Infrastructure Readiness |

Consumer Readiness |

Overall Readiness |

| Lagos |

|

|

|

| Island Zone |

58 |

72 |

65 |

| Mainland Central |

42 |

63 |

53 |

| Mainland North |

27 |

51 |

39 |

| Mainland West |

23 |

48 |

36 |

| Abuja |

|

|

|

| Central Business District/Maitama |

61 |

68 |

65 |

| Wuse/Garki |

43 |

62 |

53 |

| Asokoro/Guzape |

48 |

65 |

57 |

| Suburban Areas |

32 |

54 |

43 |

Data presented above reveals the EV adoption readiness assessment in Lagos and Abuja reveals that top-performing zones have similar readiness levels, with Lagos Island Zone and Abuja’s Central Business District/Maitama achieving 65% overall readiness. Consumer readiness consistently exceeds infrastructure readiness, indicating that demand potential outpaces current charging and supporting infrastructure development. Lagos zone performance varies significantly, with Mainland West showing a clear north-to-west decline. Abuja zone performance is more balanced, with Asokoro/Guzape outperforming commercial Wuse/Garki area, likely reflecting higher income demographics in the residential diplomatic zone. Infrastructure gaps are most pronounced in Lagos Mainland West, North, and Abuja Suburban Areas, highlighting critical infrastructure investment needs. Consumer readiness remains strong even in lower-performing zones, suggesting that infrastructure development is the primary bottleneck for EV adoption. Premium commercial and residential areas are best positioned for immediate EV adoption, while suburban and mainland areas require substantial infrastructure investment. Data presented above reveals the adoption readiness factor by city zones based on the infrastructure Readiness Factors which include existing charging points, Power reliability, Road quality and Technical service availability. On the consumer Readiness Factors, the following were revealed awareness levels, Income levels, Environmental attitudes and Technology adoption history.