Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Quantum Threat to Cryptographic Foundations

1.2. Post-Quantum Cryptography: From Theory to Practice

1.3. Research Gap and Contribution

- Assessment Gap: No standardized methodology exists for evaluating organizational quantum readiness across technical, governance, and strategic dimensions.

- Implementation Gap: Performance comparisons lack quantitative benchmarks that account for real-world constraints (latency requirements, bandwidth limits, computational resources).

- Sectoral Gap: Generic guidance fails to address sector-specific requirements in finance, telecommunications, defense, and healthcare, each with distinct threat models and operational constraints.

1.4. Contributions of This Work

- Quantum Readiness Maturity Model (QRMM): We introduce a five-level maturity framework spanning cryptographic infrastructure, governance, sectoral adaptation, interoperability, and strategic agility. This model enables systematic assessment and provides clear advancement pathways.

- Quantitative Algorithm Analysis: We present comparative performance metrics for NIST-standardized PQC algorithms, including key/signature sizes, computational costs, and implementation security considerations, enabling evidence-based deployment decisions.

- Sectoral Implementation Framework: We develop sector-specific readiness profiles for finance, telecommunications, and defense, identifying unique challenges and proposing tailored migration strategies.

- Strategic Interoperability Analysis: We examine geopolitical dynamics in PQC standardization (NIST, ETSI, China) and their implications for multinational organizations, providing guidance for navigating fragmented standards landscapes.

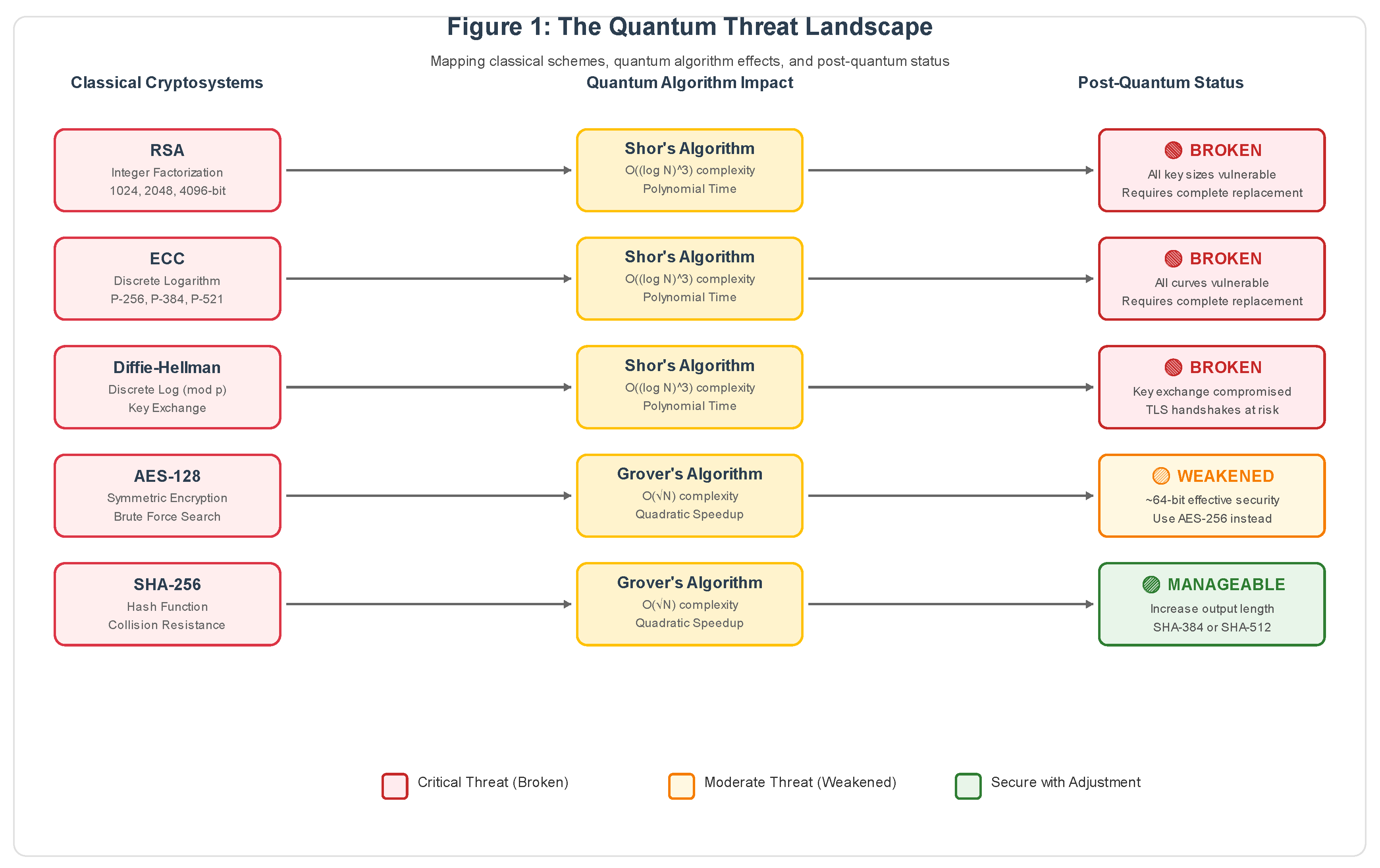

2. Quantum Threat Analysis

2.1. Shor’s Algorithm: Breaking Public-Key Cryptography

- RSA: All key sizes (1024, 2048, 4096-bit) become vulnerable once CRQCs arrive

- ECC: Shorter keys (256-bit ECC ≈ 128-bit classical security) break even faster

- Diffie-Hellman: Key exchange protocols compromised, affecting TLS handshakes globally

- Digital Signatures: ECDSA, EdDSA become forgeable, undermining authentication

2.2. Grover’s Algorithm: Weakening Symmetric Cryptography

- AES-128: Effective security reduced from 128-bit → ~64-bit

- AES-256: Remains secure at ~128-bit effective security

- SHA-256: Collision resistance weakened but remains practical

2.3. Harvest-Now-Decrypt-Later (HNDL) Threat Model

- Intercept and store encrypted communications today

- Retain ciphertexts until quantum capabilities mature

- Decrypt historical data once CRQCs become available

| Data Type | Confidentiality Lifetime | HNDL Risk Window | Mitigation Urgency |

| Government classified | 30-50 years | High (immediate threat) | Critical |

| Medical records (HIPAA) | 25+ years | High | Critical |

| Financial transactions | 7-10 years | Medium | High |

| Personal communications | 1-5 years | Low | Moderate |

| Ephemeral messaging | < 1 year | Negligible | Low |

2.4. Quantum Computing Progress and Timeline Uncertainty

- Largest systems: ~1,000 physical qubits (IBM, Google)

- Error rates: 10⁻³ to 10⁻² (far above fault-tolerance threshold of ~10⁻⁶)

- No demonstration of cryptographically relevant calculations

- Breakthrough in error correction codes (e.g., surface codes, topological qubits)

- Advances in qubit coherence times and gate fidelities

- Scaling challenges in cryogenic systems and control electronics

- Potential for classified progress exceeding public knowledge

2.5. Threat Summary and Strategic Implications

3. Post-Quantum Cryptography Algorithm Landscape

3.1. NIST PQC Standardization Process

- CRYSTALS-Kyber (renamed ML-KEM): Key encapsulation mechanism

- CRYSTALS-Dilithium (ML-DSA): General-purpose digital signatures

- Falcon (FN-DSA): Compact digital signatures for constrained environments

- SPHINCS+ (SLH-DSA): Hash-based signatures (conservative fallback)

3.2. Algorithm Families and Mathematical Foundations

3.2.1. Lattice-Based Cryptography

- Purpose: Key encapsulation for establishing shared secrets (replaces RSA/ECDH in TLS)

- Key Sizes: Public key: 800-1,568 bytes; Ciphertext: 768-1,568 bytes

- Performance: Encapsulation ~150 μs; Decapsulation ~200 μs (on 3.0 GHz Intel CPU)

- Security Levels: Three variants (ML-KEM-512, -768, -1024) equivalent to AES-128, -192, -256

- Purpose: Digital signatures for authentication and non-repudiation

- Signature Size: 2,420-4,595 bytes (vs. 64 bytes for ECDSA-256)

- Performance: Signing ~370 μs; Verification ~180 μs

- Trade-off: Larger signatures but straightforward implementation

- Purpose: Compact signatures for bandwidth-constrained applications

- Signature Size: 666-1,280 bytes (significantly smaller than Dilithium)

- Performance: Signing ~1,700 μs (slower due to floating-point operations)

- Implementation Challenge: Requires careful constant-time implementation to resist timing attacks

3.2.2. Hash-Based Cryptography

- Foundation: Security derived from hash function properties (collision/preimage resistance)

- Advantage: No unproven hardness assumptions; conservative security profile

- Signature Size: 7,856-49,856 bytes (largest among NIST selections)

- Performance: Signing ~6,000-40,000 μs; Verification ~2,000-10,000 μs

- Use Case: Long-term security where space/speed are secondary concerns

3.2.3. Code-Based Cryptography

- Foundation: Decoding random linear codes (50+ years of cryptanalysis)

- Public Key Size: 261 KB to 1.3 MB (prohibitive for most applications)

- Advantage: Oldest and most conservative PQC approach

- Status: Continues evaluation for specialized use cases (government, long-term archives)

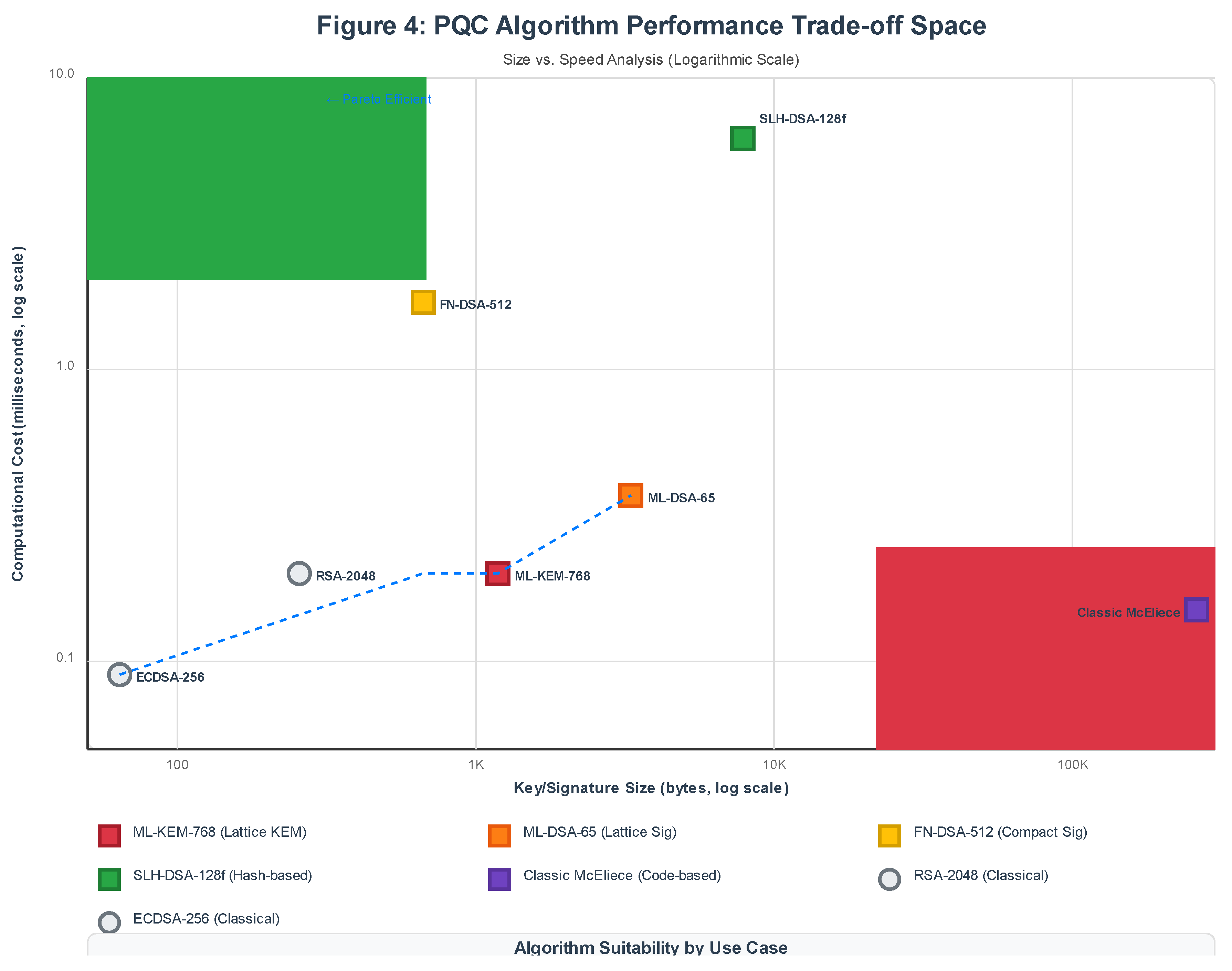

3.3. Quantitative Performance Comparison

- Key Size Penalty: PQC public keys are 3-15× larger than ECC, but smaller than RSA

- Signature Inflation: Dilithium signatures are ~50× larger than ECDSA; Falcon offers ~10× overhead

- Computational Efficiency: Kyber and Dilithium match or exceed RSA performance; Falcon and SPHINCS+ are slower

- Trade-off Spectrum: No single algorithm optimizes all metrics; deployment choices must prioritize based on constraints

| Algorithm | Type | Public Key (bytes) | Signature/Ciphertext (bytes) | Keygen (μs) | Sign/Encap (μs) | Verify/Decap (μs) | Security Level |

| ML-KEM-768 | KEM | 1,184 | 1,088 | 120 | 150 | 200 | AES-192 equiv |

| ML-DSA-65 | Sig | 1,952 | 3,309 | 250 | 370 | 180 | AES-192 equiv |

| FN-DSA-512 | Sig | 897 | 666 | 1,100 | 1,700 | 900 | AES-128 equiv |

| SLH-DSA-128f | Sig | 32 | 7,856 | 800 | 6,200 | 2,100 | AES-128 equiv |

| ECDSA-256 | Sig | 64 | 64 | 50 | 70 | 90 | AES-128 equiv |

| RSA-2048 | Both | 256 | 256 | 50,000 | 200 | 5 | AES-112 equiv |

3.4. Implementation Security Considerations

3.5. Algorithmic Diversity as Risk Mitigation

- Lattice-based: Kyber, Dilithium, Falcon (primary deployments)

- Hash-based: SPHINCS+ (conservative fallback)

- Code-based: Classic McEliece (under continued evaluation)

- Multivariate: Withdrawn after cryptanalytic breaks (Rainbow, GeMSS) [42]

- Isogeny-based: SIKE broken in 2022; research continues on alternative constructions [43]

4. Global Standardization and Interoperability Dynamics

4.1. NIST Leadership and Global Influence

4.2. European Initiatives

- Publishes white papers and technical specifications since 2015

- Emphasizes backward compatibility and hybrid approaches

- Aligns closely with NIST but maintains independent evaluation

- Issues risk assessment frameworks for EU member states

- Coordinates with national agencies (ANSSI in France, BSI in Germany)

- Focus on GDPR compliance and cross-border data protection

- €1 billion initiative combining PQC with quantum key distribution (QKD)

- EuroQCI project: quantum communication infrastructure across Europe

- Strategy: Layer PQC and QKD for defense-in-depth

4.3. China’s Dual-Path Strategy

- PQC Research: Active participation in NIST process; independent algorithm development

- QKD Infrastructure: Extensive deployment (Micius satellite, Beijing-Shanghai network)

- Strategic Goal: Technological sovereignty and reduced dependence on Western cryptographic standards

4.4. Japan and Asia-Pacific

- NICT and MIC coordinate national strategy

- Focus on IoT security and 6G infrastructure

- Active participation in ITU standardization

4.5. Interoperability Risks and Fragmentation

| Region | Leading Body | Primary Strategy | Standards Timeline | Interoperability Risk |

| North America | NIST | PQC algorithms (ML-KEM, ML-DSA) | FIPS finalized 2024 | Low (global leader) |

| Europe | ETSI/ENISA | PQC + hybrid classical | Alignment with NIST | Low-Medium (minor variants) |

| China | State Council | PQC + QKD dual-path | National rollout 2025+ | High (divergent architecture) |

| Japan | NICT/MIC | PQC for IoT/6G | Pilots 2025-2027 | Medium (sectoral focus) |

| International | ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 27 | Harmonization efforts | Ongoing | Coordination challenge |

4.6. Hybrid Cryptography as Transitional Strategy

- Backward compatibility with legacy systems

- Hedges against unexpected PQC vulnerabilities

- Gradual deployment without flag-day transitions

- Increased computational and bandwidth costs

- Complex key management and certificate infrastructure

- Potential for downgrade attacks if not carefully designed [59]

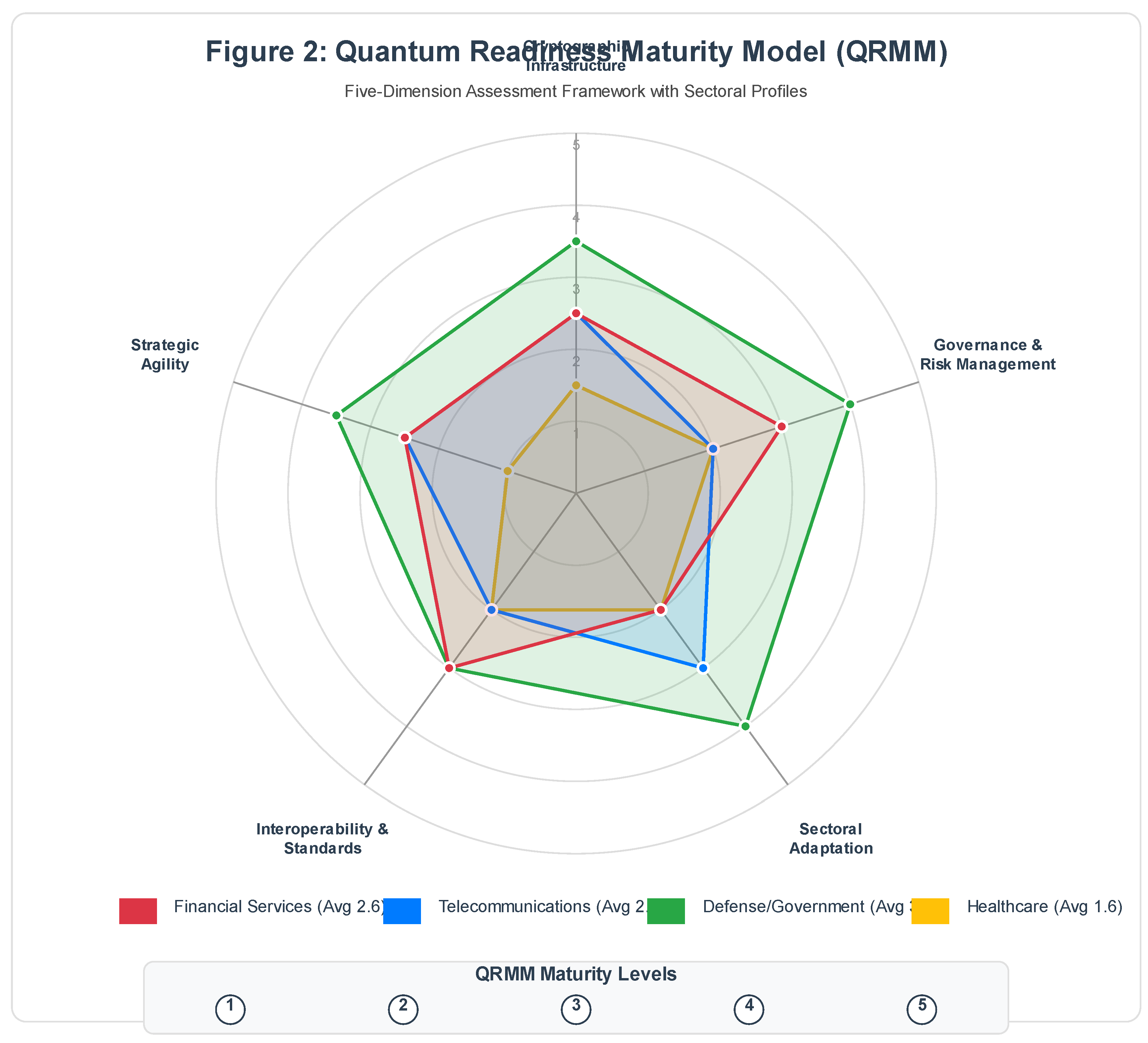

5. The Quantum Readiness Maturity Model (QRMM)

5.1. Motivation and Framework Design

- Assess current readiness across multiple dimensions

- Identify gaps and prioritize investments

- Track progress as migration unfolds

- Adapt to evolving standards and threat landscapes

5.2. QRMM Dimensions

- Discovery and inventory of cryptographic assets (algorithms in use, key sizes, certificate lifetimes)

- Testing PQC algorithms in non-production environments

- Hybrid deployment capabilities

- Integration with PKI, HSMs, and key management systems

- Executive awareness and strategic alignment

- Budget allocation and resource planning

- Risk assessment frameworks (HNDL threat modeling)

- Compliance with regulatory mandates (HIPAA, GDPR, defense classifications)

- Understanding sector-specific threat models (finance vs. healthcare vs. telecom)

- Performance requirements (latency, throughput, computational constraints)

- Legacy system constraints and migration timelines

- Vendor ecosystem readiness

- Alignment with NIST, ETSI, or regional standards

- Support for multiple PQC algorithms (algorithmic agility)

- Cross-border data flow requirements

- Protocol compatibility (TLS, IPsec, S/MIME)

- Modular cryptographic libraries enabling algorithm replacement

- Automated cryptographic policy management

- Incident response plans for cryptographic failures

- Continuous monitoring and threat intelligence integration

5.3. Maturity Levels

- Minimal awareness of quantum threat

- No cryptographic inventory

- Reactive approach to security updates

- Executive awareness and initial planning

- Pilot projects testing PQC algorithms

- Basic cryptographic asset discovery

- Formal PQC migration roadmap

- Hybrid cryptography deployed in production

- Governance frameworks established

- Vendor partnerships for PQC-enabled products

- PQC integrated across critical systems

- Automated cryptographic lifecycle management

- Continuous compliance monitoring

- Performance optimization and tuning

- Cryptographic infrastructure as strategic capability

- Real-time algorithm switching based on threat intelligence

- Multi-algorithm deployments for resilience

- Contribution to standards development and industry leadership

5.4. QRMM Assessment Methodology

- Self-Assessment: Organizations rate themselves (1-5) on each dimension using detailed rubrics

- Gap Analysis: Compare current state against target maturity levels (typically Level 3-4 for most enterprises)

- Prioritization: Identify high-impact, feasible improvements

- Roadmap Development: Define quarterly milestones and KPIs

- Continuous Improvement: Reassess annually or after major standard updates

| Level | Cryptographic Discovery | PQC Testing | Hybrid Deployment | PKI Integration |

| 1 | No inventory | None | Not considered | Manual certificate mgmt |

| 2 | Partial inventory (known apps) | Lab experiments | Evaluated but not deployed | Basic automated PKI |

| 3 | Comprehensive inventory | Pilot in staging | Hybrid in non-critical systems | PQC-aware PKI pilots |

| 4 | Automated discovery & tracking | Production testing | Hybrid in all critical systems | Full PQC PKI integration |

| 5 | Real-time monitoring & alerting | A/B testing in production | Multi-algorithm resilience | Agile certificate lifecycle |

5.5. Sectoral Application of QRMM

5.5.1. Financial Services

- Cryptographic Infrastructure: Level 2-3 (pilots underway, but production deployment limited)

- Governance: Level 3 (regulatory mandates driving formal planning)

- Sectoral Adaptation: Level 2 (performance concerns around high-frequency trading)

- Interoperability: Level 3 (SWIFT and card networks coordinating)

- Strategic Agility: Level 2 (modular architectures emerging)

- Accelerate hybrid TLS deployment for inter-bank communications

- Establish PQC-enabled digital signature services for transaction authentication

- Engage with payment networks (SWIFT, Visa, Mastercard) on standardized timelines

- Develop quantum threat scenario planning for risk management frameworks

5.5.2. Telecommunications

- Cryptographic Infrastructure: Level 2-3 (3GPP standards in development)

- Governance: Level 2 (strategic importance recognized but planning fragmented)

- Sectoral Adaptation: Level 3 (active integration in 6G research)

- Interoperability: Level 2 (international standards coordination slow)

- Strategic Agility: Level 2 (legacy network equipment constrains flexibility)

- Prioritize PQC in network core (authentication servers, base station controllers)

- Develop lightweight PQC variants for IoT devices (resource-constrained endpoints)

- Collaborate with 3GPP, ITU-T on standardized PQC integration

- Plan phased migration aligned with equipment refresh cycles (5-7 years)

5.5.3. Defense and Government

- Cryptographic Infrastructure: Level 3-4 (NSA Commercial Solutions for Classified program)

- Governance: Level 4 (legislative mandates; dedicated budgets)

- Sectoral Adaptation: Level 4 (classified systems prioritized)

- Interoperability: Level 3 (NATO and allied coordination)

- Strategic Agility: Level 3-4 (layered defenses including PQC + QKD)

- Immediate migration for systems handling top-secret/compartmented information

- Multi-algorithm deployments (lattice + hash-based) for resilience

- Integrate PQC with quantum key distribution for defense-in-depth

- Establish cryptographic supply chain security (trusted hardware/software)

5.5.4. Healthcare

- Cryptographic Infrastructure: Level 1-2 (awareness low; legacy systems pervasive)

- Governance: Level 2 (compliance-driven but under-resourced)

- Sectoral Adaptation: Level 2 (medical device constraints)

- Interoperability: Level 2 (HL7 FHIR standards evolving)

- Strategic Agility: Level 1-2 (IT modernization slow)

- Prioritize PQC for electronic health records (EHRs) and medical imaging archives

- Develop guidance for medical device manufacturers on PQC integration

- Align with HIPAA and GDPR compliance frameworks

- Establish industry consortia (HIMSS) for shared best practices

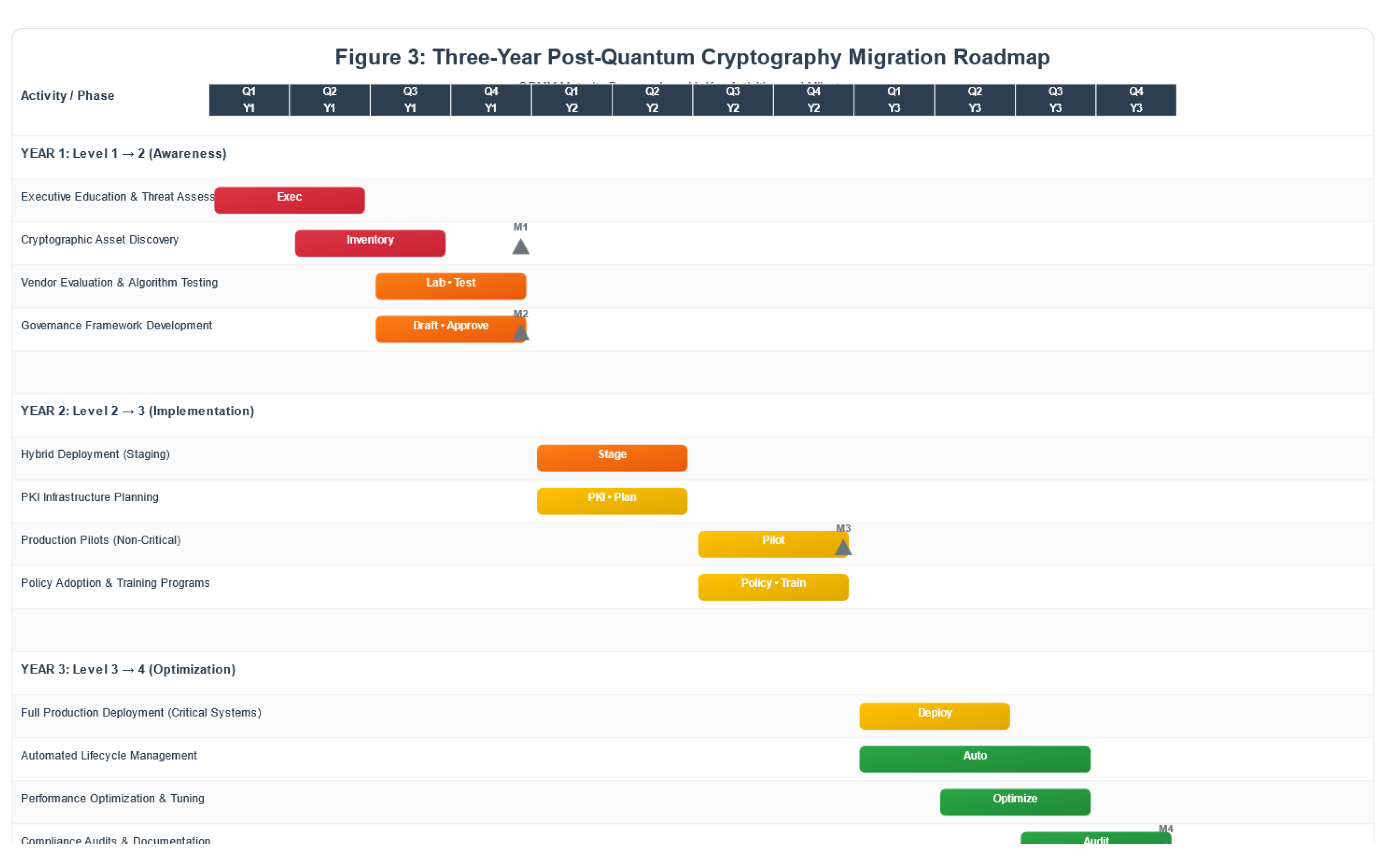

5.6. QRMM Implementation Roadmap

- Q1-Q2: Executive education; threat assessment; cryptographic inventory

- Q3-Q4: Vendor evaluation; pilot PQC algorithms in lab; governance framework draft

- Q1-Q2: Hybrid deployments in staging; PKI infrastructure planning

- Q3-Q4: Production pilots (non-critical systems); policy adoption; training programs

- Q1-Q2: Full production deployment (critical systems); automated lifecycle management

- Q3-Q4: Performance optimization; compliance audits; continuous improvement process

- Algorithmic agility testing (ability to replace algorithms quarterly)

- Threat intelligence integration (automated policy updates)

- Industry leadership (standards contributions, open-source projects)

6. Implementation Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

6.1. Performance and Resource Overheads

- Network Bandwidth: TLS handshakes increase by 2-8 KB due to larger certificates and key exchanges. For high-frequency trading systems processing 100,000 transactions/second, this represents 200-800 MB/s additional bandwidth [64].

- Computational Load: ML-DSA signing is 5× slower than ECDSA; verification is 2× slower. For authentication servers handling 50,000 requests/second, this requires proportional CPU scaling [65].

- Storage Requirements: Certificate chains grow 3-5× larger. A PKI managing 10 million certificates sees storage requirements increase from ~2.5 GB to 10-15 GB [66].

- Hardware Acceleration: Deploy cryptographic accelerators (Intel QAT, ARM CryptoCell) reducing latency by 50-70% [67]

- Algorithm Selection: Use Falcon for bandwidth-constrained scenarios; Dilithium for general-purpose deployments

- Caching and Session Resumption: Reduce handshake frequency through longer session lifetimes

- Hybrid Optimization: Only apply PQC to initial handshake; use symmetric keys for bulk data

- Infrastructure Scaling: Plan 20-30% capacity increase for compute/network resources

6.2. Legacy System Integration

- TLS/SSL implementations in billions of devices

- Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) with embedded key size limits

- Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) with fixed cryptographic capabilities

- Embedded systems with limited storage and computational resources

| System Type | Migration Difficulty | Primary Barrier | Timeline |

| Cloud services (AWS, Azure) | Low-Medium | API compatibility | 1-2 years |

| Enterprise applications | Medium | Vendor dependencies | 2-4 years |

| PKI infrastructure | High | Certificate chain trust | 3-5 years |

| IoT devices | Very High | Hardware constraints | 5-10 years (replacement) |

| Industrial control (SCADA) | Very High | Safety certification | 10-20 years |

- Hybrid Cryptography: Transition layer combining classical and PQC [68]

- Certificate = Sign_Classical(Data) || Sign_PQC(Data)

- Protocol Negotiation: Extend TLS 1.3 to advertise PQC support, falling back to classical for legacy clients [69]

- Gateway Solutions: Deploy PQC-enabled reverse proxies/gateways translating between classical and quantum-safe backends

-

Phased Retirement: Prioritize systems by data sensitivity and replacement feasibility

- ∘

- Phase 1 (0-2 years): High-value targets (government, finance, healthcare)

- ∘

- Phase 2 (2-5 years): Enterprise IT and cloud services

- ∘

- Phase 3 (5-10 years): Consumer devices and IoT

- ∘

- Phase 4 (10-20 years): Industrial and embedded systems

6.3. Certificate Authority and PKI Challenges

- Certificate Size Inflation: X.509 certificates grow from ~1 KB to 5-15 KB

- Chain Length Constraints: Some protocols limit certificate chain size (e.g., HTTP headers)

- Root CA Migration: Updating globally trusted root certificates requires years of coordination

- Revocation Mechanisms: OCSP and CRL systems must handle larger signatures

- Composite Certificates [70]: Single certificate with multiple signature algorithms

- Cert = {PublicKey_Classical, PublicKey_PQC, Sig_Classical, Sig_PQC}

- Progressive Trust Anchors: Introduce new PQC root CAs alongside existing roots during transition period (5-7 years) [71]

- Certificate Compression: IETF work on compressed certificate formats reducing overhead by 40-60% [72]

- Alternative PKI Models: Explore decentralized trust (Certificate Transparency, blockchain-based PKI) for PQC era [73]

6.4. Side-Channel and Implementation Attacks

- Variable-time operations (e.g., modular inversion in Falcon) leak secret information through execution duration

- Countermeasure: Constant-time implementations (all code paths take equal time)

- Performance cost: 10-30% slowdown

- Differential Power Analysis (DPA) extracts keys from power consumption patterns in embedded devices

- Countermeasure: Masking (randomize intermediate values) and hiding (noise injection)

- Performance cost: 2-5× computational overhead

- Induce errors during signing (voltage glitches, electromagnetic pulses) to leak private keys

- Countermeasure: Redundant computation and error detection

- Implementation complexity: High (requires hardware support)

- Adversaries measure cache access patterns to infer secret-dependent memory accesses

- Countermeasure: Constant-time memory access patterns

- Particularly challenging for lattice algorithms with data-dependent lookups

- Use formally verified cryptographic libraries (libOQS, BoringSSL)

- Apply automated side-channel testing tools (ROSITA, dudect)

- Mandate third-party security evaluations (Common Criteria EAL4+)

- Deploy hardware security modules (HSMs) with tamper-resistant enclaves

- Regular security audits and penetration testing

6.5. Migration Governance and Cost Management

- Executive sponsorship and cross-functional coordination

- Budget allocation (often millions of dollars for large enterprises)

- Risk management and compliance frameworks

- Workforce training and skill development

| Organization Size | Total Cost Range | Key Cost Drivers | Timeline |

| Small Enterprise (<500 employees) | $250K - $1M | Software updates, consulting | 2-3 years |

| Medium Enterprise (500-5,000) | $1M - $10M | Infrastructure upgrades, HSMs | 3-5 years |

| Large Enterprise (5,000-50,000) | $10M - $100M | Legacy system integration, training | 4-7 years |

| Critical Infrastructure | $100M - $1B+ | Safety certification, device replacement | 7-15 years |

- Steering Committee: Executive-level oversight with representatives from IT, security, legal, compliance, and business units

-

Risk Assessment: Quantify HNDL exposure by data classification

- ∘

- Critical (30+ year confidentiality): Immediate migration

- ∘

- High (10-30 years): Prioritize within 2-3 years

- ∘

- Moderate (5-10 years): Standard migration timeline

- ∘

- Low (<5 years): Opportunistic upgrade

-

Vendor Management:

- ∘

- Require PQC roadmaps from all cryptographic vendors

- ∘

- Establish contractual SLAs for PQC support

- ∘

- Diversify vendor relationships to avoid lock-in

-

Compliance Mapping:

- ∘

- Map regulatory requirements to PQC timeline (HIPAA, GDPR, PCI-DSS, FISMA)

- ∘

- Engage with regulators for guidance and deadline extensions

- ∘

- Document migration progress for audit purposes

-

Training and Awareness:

- ∘

- Develop PQC training curriculum for security teams

- ∘

- Executive briefings on strategic implications

- ∘

- Developer training on secure PQC implementation

6.6. Interoperability and Standards Fragmentation Risks

- NIST standardizes ML-KEM/ML-DSA

- China mandates domestic PQC algorithms (SM2-PQ variant)

- Result: Multinational corporations must support parallel cryptographic stacks

- Region A requires ML-KEM-1024 (AES-256 equivalent security)

- Region B accepts ML-KEM-768 (AES-192 equivalent)

- Result: Cross-border communications default to lower security level

- TLS 1.3 extensions for PQC differ between implementations

- Some vendors support hybrid mode; others PQC-only

- Result: Handshake failures and connectivity issues

- Multi-Algorithm Support: Implement crypto-agility to support NIST, ETSI, and regional standards simultaneously [81]

- Standards Advocacy: Participate in IETF, ISO, and regional standardization bodies

- Interoperability Testing: Establish industry test events (PQC Plugfests) similar to IPv6 transition [82]

- Fallback Mechanisms: Design protocols with graceful degradation to ensure connectivity

- Regulatory Engagement: Work with policymakers to harmonize requirements

6.7. Open Research Questions

- Long-Term Algorithm Security: Will lattice-based assumptions withstand decades of cryptanalysis? SPHINCS+ offers conservative fallback, but at significant performance cost.

- Quantum-Safe PKI Architecture: How should certificate authorities evolve? Should we move toward shorter-lived certificates, decentralized trust models, or entirely new paradigms?

- IoT and Resource-Constrained Devices: Current PQC algorithms strain low-power microcontrollers. Research into lightweight variants (e.g., NTRU Prime, FrodoKEM) continues [83].

- Post-Quantum Blockchain: Cryptocurrencies rely on ECDSA for signatures and SHA-256 for proof-of-work. Migration strategies for decentralized systems require community consensus [84].

- Quantum Threat Timeline Refinement: Better forecasting models would enable more precise resource allocation and risk management [85].

- Side-Channel Resistant Implementations: Formal verification of constant-time properties remains computationally expensive and incomplete [86].

7. Discussion: Strategic Implications and Future Directions

7.1. Beyond Algorithms: Quantum Readiness as Organizational Capability

7.2. The Geopolitics of Post-Quantum Cryptography

7.3. Economic Considerations and Market Dynamics

- Cryptographic hardware (HSMs, accelerators): $30B

- Security software and services: $250B

- Consulting and integration: $80B

- Training and certification: $15B

- Market share in PQC-enabled products

- Influence over emerging standards

- Talent acquisition advantages

- Patent portfolios in PQC implementations

- Vendor lock-in and reduced competition

- Higher switching costs

- Systemic vulnerabilities if dominant vendor compromised

7.4. Ethical and Social Dimensions

- Developing nations may lag in PQC adoption

- Small healthcare providers may struggle to protect patient data

- Educational institutions face competing budget priorities

- Responsibility to protect data beyond immediate stakeholders

- Liability frameworks for inadequate cryptographic protection

- Rights of individuals whose data is compromised decades later

7.5. Future Research Directions

- Cryptographic asset discovery and inventory

- Automated protocol translation (classical ↔ PQC)

- Performance optimization and tuning

- Compliance verification and reporting

- Blockchain and Distributed Ledgers: Consensus mechanisms, signature aggregation

- Confidential Computing: PQC in trusted execution environments (TEEs)

- 6G and Satellite Networks: Ultra-low-latency PQC for next-generation communications

- Autonomous Systems: Real-time cryptographic decision-making in vehicles, robots

- Mathematics (cryptography, number theory, lattice theory)

- Computer science (implementation, formal methods)

- Engineering (hardware, networking)

- Law and policy (regulation, compliance)

- Economics (cost-benefit analysis, market dynamics)

- Social sciences (organizational change, risk perception)

7.6. The Path Forward: Recommendations for Stakeholders

- Conduct QRMM assessment and establish baseline maturity

- Develop 3-5 year migration roadmap with quarterly milestones

- Allocate 5-10% of cybersecurity budget to PQC transition

- Establish executive-level governance with cross-functional representation

- Begin hybrid deployments in non-critical systems for learning

- Issue clear PQC mandates with realistic timelines (2027-2030 for critical infrastructure)

- Fund public research into PQC optimization and side-channel resistance

- Support small business migration through grants and tax incentives

- Coordinate internationally to prevent standards fragmentation

- Update procurement requirements to mandate PQC support

- Publish transparent PQC roadmaps with feature timelines

- Offer hybrid solutions enabling gradual migration

- Provide migration tooling and consulting services

- Participate in open-source PQC projects (libOQS, Open Quantum Safe)

- Contribute to standards development (IETF, ISO, NIST)

- Focus on lightweight PQC for resource-constrained devices

- Develop automated side-channel testing and formal verification tools

- Investigate post-PQC and quantum-enhanced cryptanalysis

- Study organizational and economic aspects of cryptographic transitions

- Engage with practitioners to ensure research addresses real-world needs

8. Conclusions

- Technical Maturity: NIST-standardized algorithms (ML-KEM, ML-DSA, FN-DSA, SLH-DSA) provide strong quantum resistance with manageable performance overheads. Lattice-based schemes offer the best balance for most applications; hash-based signatures provide conservative fallback options.

- Organizational Gap: Most enterprises remain at QRMM Level 1-2 (awareness and initial planning). Advancing to Level 3-4 (implementation and optimization) requires executive commitment, governance frameworks, and sustained investment.

- Sectoral Heterogeneity: Finance, telecommunications, defense, and healthcare face distinct challenges demanding tailored strategies. Generic guidance risks under-protection or resource misallocation.

- Interoperability Risk: Fragmented regional standards (NIST, ETSI, China) threaten global connectivity. Crypto-agility—supporting multiple algorithms and standards—emerges as critical capability.

- Strategic Imperative: Quantum readiness is not a project with defined endpoint but an ongoing organizational capability. The “Years-to-Quantum” uncertainty and HNDL threat model demand proactive action despite timeline ambiguity.

- Embed crypto-agility into architectural principles

- Establish governance frameworks balancing security and operational requirements

- Invest in workforce development and organizational learning

- Participate in standards development and industry collaboration

- Maintain continuous monitoring and adaptive planning

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Appendix A. QRMM Assessment Rubrics (Condensed)

Appendix B. Glossary of Key Terms

References

- Shor, P. W. “Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring.” Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, IEEE, 1994, pp. 124-134.

- Gidney, C.; Ekerå, M. “How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits.”. Quantum 2021, 5, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects, 2019.

- Mosca, M.; Mulholland, J. “A methodology for quantum risk assessment.” Global Risk Institute, 2017.

- Grover, L. K. “A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search.” Proceedings 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 1996, pp. 212-219.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. “Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization.” https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography, accessed January 2025.

- Regev, O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. J. ACM 2009, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, R. C. “A certified digital signature.” Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ‘89, Springer, 1990, pp. 218-238.

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute. “Quantum Safe Cryptography and Security.” ETSI White Paper No. 8, 2015.

- Bindel, N.; Hülsing, A. Challenges in post-quantum cryptography standardization. IT Professional 2021, 23, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett, E.; Paquin, C.; Stebila, D. “Prototyping post-quantum and hybrid key exchange and authentication in TLS and SSH.” NIST 2nd PQC Standardization Conference, 2019.

- Peikert, C. “A decade of lattice cryptography. ” Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science 2016, 10, 283–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. J.; Lange, T. “Post-quantum cryptography. ” Nature 2017, 549, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, M. “Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers: Will we be ready? ” IEEE Security & Privacy 2018, 16, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; et al. “Report on post-quantum cryptography.” NIST Interagency Report 8105, 2016.

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banegas, G.; Bernstein, D. J. “Low-communication parallel quantum multi-target preimage search.” Selected Areas in Cryptography, Springer, 2018, pp. 325-335.

- National Security Agency. “Quantum computing and post-quantum cryptography FAQ.” Updated August 2021.

- Campagna, M.; et al. “Quantum safe cryptography and security: An introduction, benefits, enablers and challengers.” ETSI White Paper No. 8, 2015.

- UK National Cyber Security Centre. “Preparing for quantum-safe cryptography.” November 2020.

- Chow, J.; et al. “IBM Quantum roadmap to build quantum-centric supercomputers.” IBM Research Blog 2022.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). “Post-quantum cryptography: Current state and quantum mitigation.” 2021.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. “FIPS 203: Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard.” August 2024.

- Alagic, G.; et al. “Status report on the third round of the NIST post-quantum cryptography standardization process.” NISTIR 8413, 2022.

- Alkim, E.; Ducas, L.; Pöppelmann, T.; Schwabe, P. “Post-quantum key exchange—A new hope.” USENIX Security Symposium, 2016, pp. 327-343.

- Lyubashevsky, V.; et al. “CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A lattice-based digital signature scheme.” IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 2018, pp. 238-268.

- Avanzi, R.; et al. “CRYSTALS-Kyber algorithm specifications and supporting documentation.” NIST PQC Submission, 2020.

- Ducas, L.; et al. “CRYSTALS-Dilithium: Algorithm specifications and supporting documentation.” NIST PQC Submission, 2020.

- Fouque, P.-A.; et al. “Falcon: Fast-Fourier lattice-based compact signatures over NTRU.” NIST PQC Submission, 2020.

- Hülsing, A.; et al. “SPHINCS+: Submission to the NIST post-quantum project.” NIST PQC Submission, 2020.

- Bernstein, D. J.; et al. “Classic McEliece: Conservative code-based cryptography.” NIST PQC Submission, 2020.

- Kannwischer, M. J.; et al. “PQM4: Post-quantum crypto library for the ARM Cortex-M4.” Workshop on Attacks and Solutions in Hardware Security, 2019, pp. 79-82.

- Westerbaan, B.; Stebila, D. “X25519Kyber768Draft00 hybrid post-quantum key agreement.” Internet-Draft, IETF, 2023.

- Paquin, C.; et al. “Performance benchmarking of post-quantum cryptography in TLS.” NIST 4th PQC Standardization Conference, 2022.

- Ravi, P.; Roy, S. S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Bhasin, S. “Generic side-channel attacks on CCA-secure lattice-based PKE and KEMs.” IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 2020, pp. 307-335.

- Pessl, P.; et al. “HECTOR-V2: Side-channel analysis of lattice-based post-quantum cryptographic schemes.” Selected Areas in Cryptography, 2019.

- Hamburg, M. “Post-quantum cryptography: Implementation vulnerabilities and lessons learned.” Real World Crypto Symposium, 2020.

- Oder, T.; et al. “Implementing the NewHope-Simple key exchange on low-cost FPGAs.” Progress in Cryptology – LATINCRYPT, 2017, pp. 128-142.

- Genkin, D.; Shamir, A.; Tromer, E. “RSA key extraction via low-bandwidth acoustic cryptanalysis.” Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO, 2014, pp. 444-461.

- Gueron, S.; Krasnov, V. Fast prime field elliptic-curve cryptography with 256-bit primes. J. Cryptogr. Eng. 2014, 5, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, D. “The ship has sailed: The NIST post-quantum cryptography ‘competition’.” AsiaCrypt Invited Talk, 2017.

- Beullens, W. “Breaking Rainbow takes a weekend on a laptop.” Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO, 2022, pp. 464-479.

- Castryck, W.; Decru, T. “An efficient key recovery attack on SIDH (preliminary version).” IACR ePrint Archive, 2022/975, 2022.

- Bindel, N.; et al. “Transitioning to a quantum-resistant public key infrastructure.” Post-Quantum Cryptography, Springer, 2017, pp. 384-405.

- Langley, A. “CECPQ2.” Cloudflare Blog, December 2018.

- Stebila, D.; Mosca, M. “Post-quantum key exchange for the Internet and the Open Quantum Safe project.” Selected Areas in Cryptography, 2017, pp. 14-37.

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute. “Migration strategies and recommendations to quantum safe schemes.” ETSI GR QSC 006, 2021.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. “Post-quantum cryptography: Integration study.” ENISA Report, 2021.

- European Commission. “Strategic Research Agenda for Quantum Technologies.” Quantum Flagship, 2020.

- Pan, J.-W.; et al. “Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers. ” Science 2017, 356, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Quantum Secure Networks Group. “Quantum communications for all.” NPG Asia Materials, 2023.

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y.-K. “Report on post-quantum cryptography in China.” NISTIR Special Publication, 2023.

- National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (Japan). “Research and development roadmap for quantum cryptography.” 2022.

- Korea Internet & Security Agency. “Post-quantum cryptography migration guidelines.” 2023.

- Cyber Security Agency of Singapore. “Quantum-safe cryptography strategy.” 2022.

- Bank for International Settlements. “Quantum computing and financial stability.” BIS Working Paper, 2023.

- Basso, A.; et al. “Supersingular curves you can trust.” IACR ePrint Archive, 2021/1680, 2021.

- Schwabe, P.; Stebila, D.; Wiggers, T. “Post-quantum TLS without handshake signatures.” ACM CCS, 2020, pp. 1461-1480.

- Dowling, B.; et al. “A cryptographic analysis of the TLS 1. 3 handshake protocol.” Journal of Cryptology 2021, 34, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center. “Quantum computing threat assessment for banking.” FS-ISAC White Paper, 2023.

- 3rd Generation Partnership Project. “Study on security aspects of 5G.” 3GPP TR 33.899, 2023.

- U.S. National Security Agency. “Announcing the Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0.” Cybersecurity Advisory, 2022.

- Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. “Post-quantum cryptography readiness in healthcare.” HIMSS Report, 2024.

- Sikeridis, D.; et al. “Post-quantum authentication in TLS 1.3: A performance study.” NDSS, 2020.

- Kampanakis, P.; Panburana, P. “Post-quantum cryptography performance on embedded devices.” IEEE Consumer Communications & Networking Conference, 2021.

- Ounsworth, M.; Pala, M. “Composite keys and signatures for use in Internet PKI.” Internet-Draft, IETF, 2023.

- Intel Corporation. “Intel QuickAssist Technology for post-quantum cryptography.” Technical White Paper, 2023.

- Bindel, N.; et al. “Hybrid key encapsulation mechanisms and authenticated key exchange.” Post-Quantum Cryptography, Springer, 2019, pp. 206-226.

- Stebila, D.; et al. “Hybrid post-quantum key encapsulation methods (PQ KEM) for Transport Layer Security 1.2 (TLS).” Internet-Draft, IETF, 2023.

- Ounsworth, M.; et al. “Composite signatures for use in Internet PKI.” Internet-Draft, IETF, 2023.

- Hoffman, P.; Schlyter, J. “The DNS-based authentication of named entities (DANE) Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol: TLSA.” RFC 6698, 2012.

- Ghedini, A.; Vasiliev, V. “TLS certificate compression.” RFC 8879, 2020.

- Laurie, B.; Langley, A.; Kasper, E. “Certificate transparency.” RFC 6962, 2013.

- Kocher, P.; et al. “Spectre attacks: Exploiting speculative execution.” IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2019, 1–19.

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. “Differential power analysis.” Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ‘99, Springer, 1999, pp. 388-397.

- Boneh, D.; DeMillo, R. A.; Lipton, R. J. “On the importance of checking cryptographic protocols for faults.” Advances in Cryptology — EUROCRYPT ‘97, Springer, 1997, pp. 37-51.

- Yarom, Y.; Falkner, K. “FLUSH+RELOAD: A high resolution, low noise, L3 cache side-channel attack.” USENIX Security Symposium, 2014, pp. 719-732.

- Ravi, P.; et al. “Side-channel assisted existential forgery attack on Dilithium.” IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2023, 454–481.

- Gartner Research. “Market guide for quantum-safe cryptography.” Research Report G00762341, 2023.

- IDC Technology Spotlight. “The economic impact of post-quantum cryptography migration.” Sponsored by IBM, 2024.

- Hoffman, P. “Cryptographic algorithm agility and selecting mandatory-to-implement algorithms.” BCP 201, RFC 7696, 2015.

- Open Quantum Safe Project. “liboqs: C library for quantum-resistant cryptographic algorithms.” https://openquantumsafe.org/, 2024.

- Hülsing, A.; et al. “FrodoKEM: Learning with errors key encapsulation.” NIST PQC Round 3 Submission, 2020.

- Fernández-Caramés, T. M.; Fraga-Lamas, P. “Towards post-quantum blockchain: A review on blockchain cryptography resistant to quantum computing attacks. ” IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21091–21116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M.; Piani, M. “Quantum threat timeline report 2022.” Global Risk Institute, 2022.

- Protzenko, J.; et al. “EverCrypt: A fast, verified, cross-platform cryptographic provider.” IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2020, 983–1002.

- Campbell, E. T.; Terhal, B. M.; Vuillot, C. “Roads towards fault-tolerant universal quantum computation. Nature 2017, 549, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Telecommunication Union. “Quantum key distribution networks: Security handbook.” ITU-T Recommendation X.1710, 2020.

- Orcutt, M. “The networking technology that could bring quantum computing to more people.” MIT Technology Review, 2023.

- Xu, F.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lo, H.-K.; Pan, J.-W. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. “Cybersecurity strategy for the digital decade.” European Commission Communication COM(2020) 823, 2020.

- Krelina, M. Quantum technology for military applications. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2021, 8, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar Arrangement. “List of dual-use goods and technologies and munitions list.” 2022 Edition, December 2022.

- Markets and Markets. “Quantum cryptography market global forecast to 2028.” Market Research Report TC 8139, 2023.

- Bernstein, D. J.; et al. “Post-quantum cryptography standardization should prioritize open-source implementations. ” Communications of the ACM 2023, 66, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson, S.; Gottesman, D. “Improved simulation of stabilizer circuits. ” Physical Review A 2004, 70, 052328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbush, R.; et al. “Focus beyond quadratic speedups for error-corrected quantum advantage. ” PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 010103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthe, G.; et al. “Formal verification of side-channel countermeasures using self-composition. ” Science of Computer Programming 2013, 78, 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation. “Convergent research to secure the quantum future.” NSF Program Solicitation 23-605, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).