1. Introduction

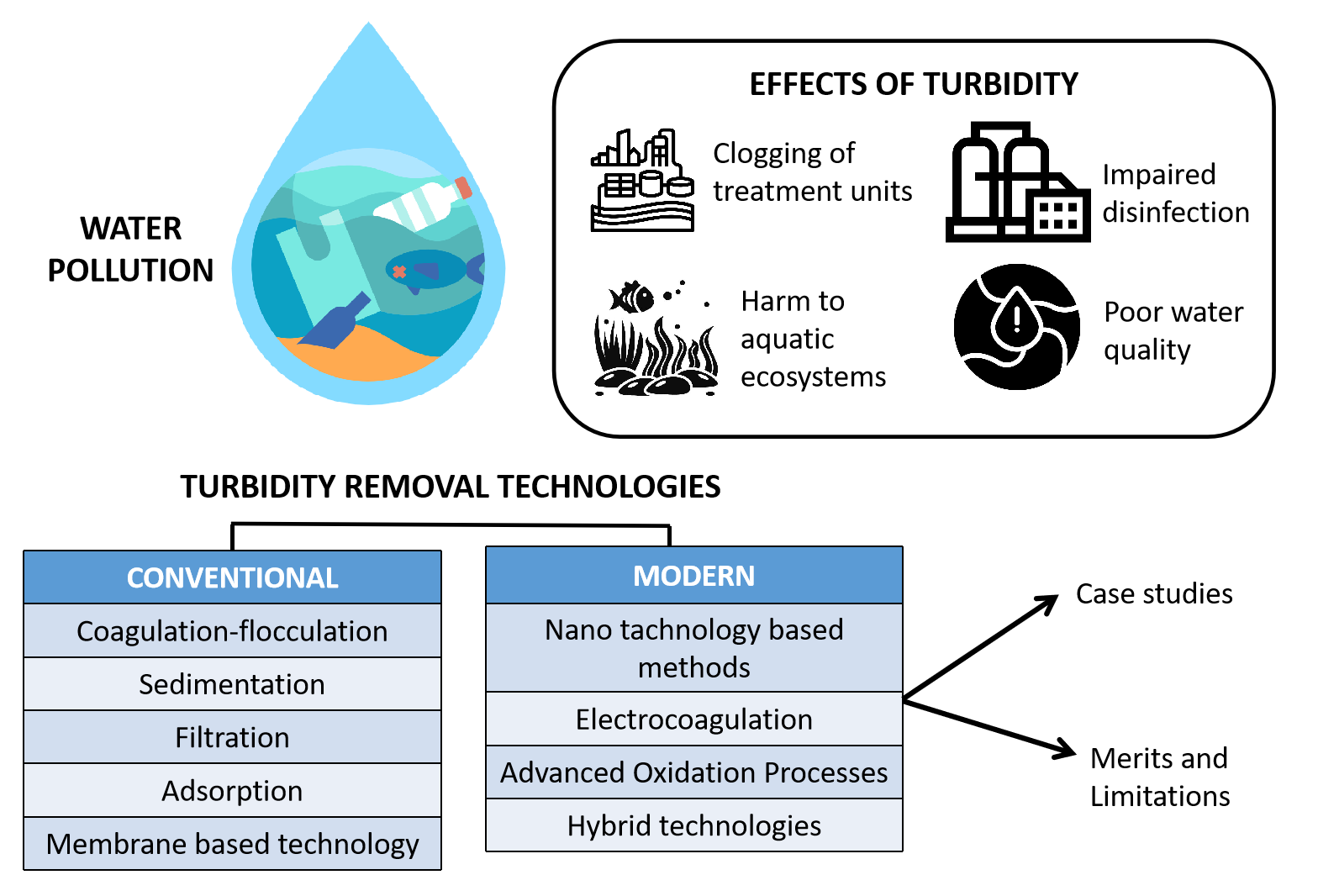

At present, water pollution has become one of the most critical global challenges faced by the Earth, known to harm humans, animals, entire ecosystems, as well as economies [

1]. Consequently, the water quality of many resources around the world, which supports the needs of humans, animals, plants, and others, is rapidly declining. Turbidity is a fundamental parameter which refers to the reduction in water clarity caused by the presence of materials such as suspended solids, clay, silt, organic and inorganic matter, decaying substances, algae, plankton, and other microscopic organisms. These materials can enter water bodies through sources such as wastewater discharges, agricultural and storm water runoff, and industrial effluents [

2,

3,

4]. Water is classified as turbid due to the prominent suspension of such particles, which reduces its clarity. These suspended materials have the capacity to absorb or scatter light [

5]. As a result, turbidity is measured based on the amount of light scattered by suspended matter when light passes through a water sample. The degree of light scattering depends on the size, shape, and composition of the suspended particles. Thus, turbidity is considered a measure of relative clarity or transparency, commonly expressed in Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) [

6]. A high NTU value indicates increased light scattering, meaning less light passes through the water, signifying elevated turbidity levels, and vice versa for lower turbidity levels [

2]. Turbidity in water can lead to numerous harmful effects. Particles responsible for turbidity can interfere with chemical disinfection processes such as ultraviolet (UV) irradiation or ozonation, which are commonly employed in water and wastewater treatment. These particles may act as physical barriers, shielding microorganisms from disinfection and thereby promoting the survival and proliferation of bacteria and viruses. If not properly removed, these particles can contaminate water distribution systems in both residential and non-residential areas, increasing the risk of waterborne diseases. Moreover, in treatment systems, higher doses of disinfectants may be required to address turbidity, potentially resulting in the formation of harmful byproducts. These byproducts can persist in water supply networks, posing additional health risks to consumers. Elevated turbidity also reduces light penetration in aquatic environments, disrupting essential processes such as photosynthesis in aquatic plants and consequently lowering dissolved oxygen levels. This can significantly impact the survival of aquatic ecosystems. Additionally, increased sedimentation in areas with high turbidity may threaten benthic habitats and other sensitive ecological regions. In industrial settings, turbidity can negatively affect downstream process efficiency by clogging filters, scaling equipment, and reducing flow rates, ultimately leading to higher operational and maintenance costs [

4]. Furthermore, the presence of visible cloudiness in drinking water can lead to consumer dissatisfaction and mistrust regarding its safety and quality [

7].

Thus, the removal of turbidity from water is a primary objective in water and wastewater treatment, as it ensures the supply of potable and aesthetically acceptable water for consumers, supports industrial applications, and contributes to environmental protection. Various techniques are available for turbidity removal, generally categorized into conventional and modern treatment methods. Conventional treatment techniques follow well-established procedures, have been extensively studied, and widely applied across the globe for many years. In contrast, modern treatment methods are still evolving alongside advancements in technology. This review paper aims to present a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of turbidity removal technologies, with particular emphasis on emerging approaches along with their advantages and limitations. The review will discuss the underlying principles, practical applications, and associated challenges of selected modern treatment methods, supported by findings from relevant case studies.

Table 1 below outlines both traditional and emerging techniques for turbidity removal, which are examined through this paper.

2. Conventional Treatment Techniques in Removing Turbidity

2.1. Coagulation (with Flocculation)

Coagulation, followed by flocculation, is a physico-chemical process commonly employed in conventional water and wastewater treatment plants. This technique involves two key steps: coagulation (a chemical process) and flocculation (a physical process). Initially, the water is subjected to rapid mixing (flash mixing) to promote the aggregation of turbidity-causing particles into small clusters known as micro flocs, a process referred to as coagulation. To enhance the efficiency of micro floc formation, chemical coagulants are typically added. Among the conventional coagulants, inorganic salts such as ferric sulfate, aluminum sulfate (alum), and ferric chloride are most widely used. The optimal dosage of coagulants depends primarily on the pH of the water [

8].

The primary objective of coagulation is to destabilize negatively charged particles. Many turbidity-inducing contaminants, such as clay, silt, and other suspended solids, carry negative surface charges, which generate electrostatic repulsive forces and keep them dispersed in water. When positively charged coagulants are introduced, these repulsive forces are neutralized. For instance, when alum is used, Al³⁺ ions act as cations that neutralize the negative charges, reducing electrostatic repulsion and allowing the particles to draw closer. This results in the formation of small, destabilized micro flocs. The subsequent step is flocculation. Unlike coagulation, flocculation involves gentle agitation of the liquid to encourage the micro flocs to collide and bind together, forming larger and more stable flocs. To enhance this process, flocculants are added, typically organic polymers, which are effective at lower dosages [

9]. The larger flocs formed during flocculation can then be efficiently removed through sedimentation and/or filtration. The combined use of coagulants, flocculants, and controlled mixing helps to optimize both processing time and treated water quality. As the flocs settle out, water clarity improves significantly due to the removal of suspended particles.

This treatment technique has its own advantages and limitations. While coagulation and flocculation significantly reduce the time required for suspended particles to settle, they are highly effective in removing fine particles, resulting in high turbidity removal efficiency [

10]. Eliminating a substantial portion of suspended matter through this method can positively impact subsequent treatment units, such as filtration, by reducing their load and improving overall performance [

11]. However, one notable drawback of this method is the generation of sludge containing inorganic salts used during chemical coagulation. Proper disposal of this sludge is essential to prevent environmental contamination. Additionally, coagulation (with flocculation) can be a costly process due to the use of chemical additives and the energy required for flash mixing. Flash mixing involves intense agitation over a very short duration, typically less than one minute, necessitating the selection of appropriate motors and impellers to ensure sufficient mixing without mechanical limitations [

12]. A study involving one of the authors was conducted to reduce the cost associated with expensive commercial coagulants by comparing their performance with that of locally available natural coagulants [

13]. The findings revealed that, although natural coagulants are generally less efficient than commercial ones, they were capable of achieving up to 82% turbidity removal. Coagulation and flocculation processes are generally effective in reducing turbidity in raw water, thereby decreasing the load on subsequent treatment stages in the treatment train. Coagulation strategies for reducing turbidity showed promise as a pre-treatment method for coal seam gas (CSG) associated water, helping to reduce fouling in downstream equipment and desalination membranes [

14].

2.2. Sedimentation

Sedimentation (which is usually preceded by coagulation and flocculation) is one of the oldest approaches used to remove turbidity. In this process, the heavier sediments are allowed to naturally settle under the influence of gravity in an undisturbed tank or pool, forming a sludge layer at the bottom. Sedimentation is typically used to remove suspended and/or settleable solids, but it is not effective for certain finer particles that cannot settle easily and remain suspended for longer durations [

15,

16]. These finer particles may be removed through subsequent processes such as filtration and disinfection, which are particularly employed in treatment plants and large reservoirs [

17]. Although sedimentation has the capability to purify water, reduce chemical concentrations, and lower turbidity at relatively low cost, the rate of sedimentation is a critical factor that can significantly affect its efficiency. The sedimentation rate depends on several factors including the size and shape of the particles, the density of the solids, and the viscosity of the liquid [

18].

2.3. Filtration

Filtration is a treatment process that typically follows sedimentation in water and wastewater treatment plants to remove residual contaminants. This technique employs a porous medium designed to eliminate solid particles, including suspended solids, pathogens, unpleasant odors, tastes, colors, and various other contaminants present in wastewater or raw water sources. There are two main types of sand filtration commonly employed in conventional water and wastewater treatment plants: rapid sand filters and slow sand filters. These two filtration types differ significantly in their operational principles, flow rates, and maintenance requirements. Slow sand filters operate at considerably slower rates and rely on a biological layer known as the schmutzdecke, which forms on top of the sand bed to aid in purification. This biological layer enables the filter to effectively remove solid particles, pathogens, organic matter, and other contaminants [

19]. Usually, rapid sand filters generally require pre-treatment steps such as coagulation (with flocculation) and sedimentation, whereas slow sand filters typically do not require such pre-treatment when treating raw water with turbidity levels below 50 NTU [

20]. For waters with turbidity levels less than 10–20 NTU, slow sand filters can operate more efficiently and reliably [

21,

22,

23]. Coagulation and flocculation are not suitable pre-treatment techniques for slow sand filters, as unsettled flocs can clog the sand bed and impair filtration performance. Conversely, rapid sand filters, which are commonly used in conventional water treatment systems, are highly effective in removing turbidity. To further enhance the performance of rapid sand filters, a process known as capping can be employed. Capping involves replacing a few centimeters of the upper sand layer with alternative capping materials such as anthracite coal, PVC granules, crushed coconut shells, bituminous coal, broken bricks, and others. Among these materials, a pilot-scale study conducted by Tamakhu et al., (2021) [

24] demonstrated that anthracite coal exhibited particularly promising results for treating various turbidity levels in water. Moreover, their comparative analysis revealed that anthracite coal allowed for higher filtration rates while requiring less frequent back washing.

In both slow and rapid filtration methods, filters may employ a single type of media (mono-media) or be composed of multiple layers of distinct media types, known as multimedia filters. In multimedia filters, such as roughing filters, which often contain successive layers of filter media with decreasing particle sizes in the direction of water flow [

25] - each distinct layer is capable of trapping and removing specific types of suspended solids. While multimedia filters are effective for treating various turbidity levels, the composition and arrangement of these layers can be customized to address the unique characteristics of specific water quality conditions [

15]. Commonly employed filter media include sand, gravel, charcoal, and anthracite coal, among others. Numerous studies have investigated and compared the turbidity removal efficiencies of these media. For example, a study conducted by Nkwonta et al., (2010) [

26] evaluated the performance of gravel versus charcoal as filter media, concluding that charcoal demonstrated superior efficiency. This enhanced efficiency is likely attributable to charcoal’s higher specific surface area and greater porosity compared to gravel, which can facilitate additional filtration mechanisms such as adsorption.

Roughing Filtration

Pebble matrix filtration (PMF) is a type of roughing filtration technology specifically designed as a pre-treatment step to effectively reduce high turbidity levels before slow sand filtration. It consists of a matrix of natural pebbles approximately 50 mm in diameter, with the lower section filled with finer media (<1 mm) typically sand. Due to this configuration, it can also be classified as a dual-media filter. Experimental studies have explored the use of alternative filter media, such as clay balls and crushed glass, in place of pebbles and sand. In the tested filtration velocity range of 0.72–1.33 m/h and inlet turbidity range of (78–589) NTU, both sand and glass produced above 95% removal efficiencies. The head loss development during clogging was about 30% higher in sand than in glass media [

27]. While these experiments were conducted as a pre-treatment stage ahead of slow sand filtration, there is potential, pending further research, to increase filtration rates, enabling broader application of the technology, including its integration into rapid sand filtration systems.

The primary drawback of employing filtration as a water or wastewater purification method is the gradual clogging of the filter media over time. Therefore, appropriate maintenance measures must be implemented to mitigate this issue effectively. Typically, with rapid filters, after 2–3 years of operation, reapplication or replenishment of the filter media may be necessary, as some layers can become diminished due to repeated backwashing. It is generally recommended to replace the filter media layers entirely after approximately 4–5 years to maintain optimal performance [

28]. However, this maintenance requirement can incur significant costs, especially since certain specialized filter media essential for treating specific types of turbid water may not be readily or freely available in all regions.

2.4. Adsorption

Adsorption is traditionally classified as a conventional method for water and wastewater treatment. However, with recent advancements in adsorbent materials, such as nanotechnology-based materials and functionalized biochars, many hybrid approaches have been developed that significantly enhance turbidity removal efficiencies [

29]. This section focuses on the conventional aspects of adsorption. Adsorption is a process in which small particles present in water (adsorbates) become attracted to and adhere to the surface of an adsorbent material. These particles may be physically bound through van der Waals forces or chemically attached to the adsorbent surface [

30]. Common examples of adsorbent materials include activated carbon, zeolites, silica, alumina, etc [

31].

This technique is typically employed as a polishing step (tertiary treatment) following coagulation (with flocculation) and filtration, effectively removing contaminants that are difficult to eliminate through the secondary treatment methods described earlier [

32]. In the context of water treatment, the water is allowed to pass through fixed beds or columns packed with the adsorbent material. During this stage, contaminants in the water are adsorbed onto the porous surface of the adsorbent. The overall performance of this adsorption system depends on several key parameters, including contact time, temperature, pH, adsorbent dosage, initial adsorbate concentration, etc [

33]. Over time, contaminants accumulate within the adsorbent bed or column, leading to the formation of an adsorption front known as the mass transfer zone. This dynamic region represents the area where active adsorption takes place. As the upstream media becomes saturated, this adsorption front gradually moves through the column (or bed). Eventually, with continued operation, contaminants begin to appear in the effluent, indicating that the adsorbent media is nearing exhaustion [

34]. Therefore, continuous monitoring is essential to accurately detect this point of exhaustion, enabling timely replacement or regeneration of the adsorbent media to maintain treatment efficacy.

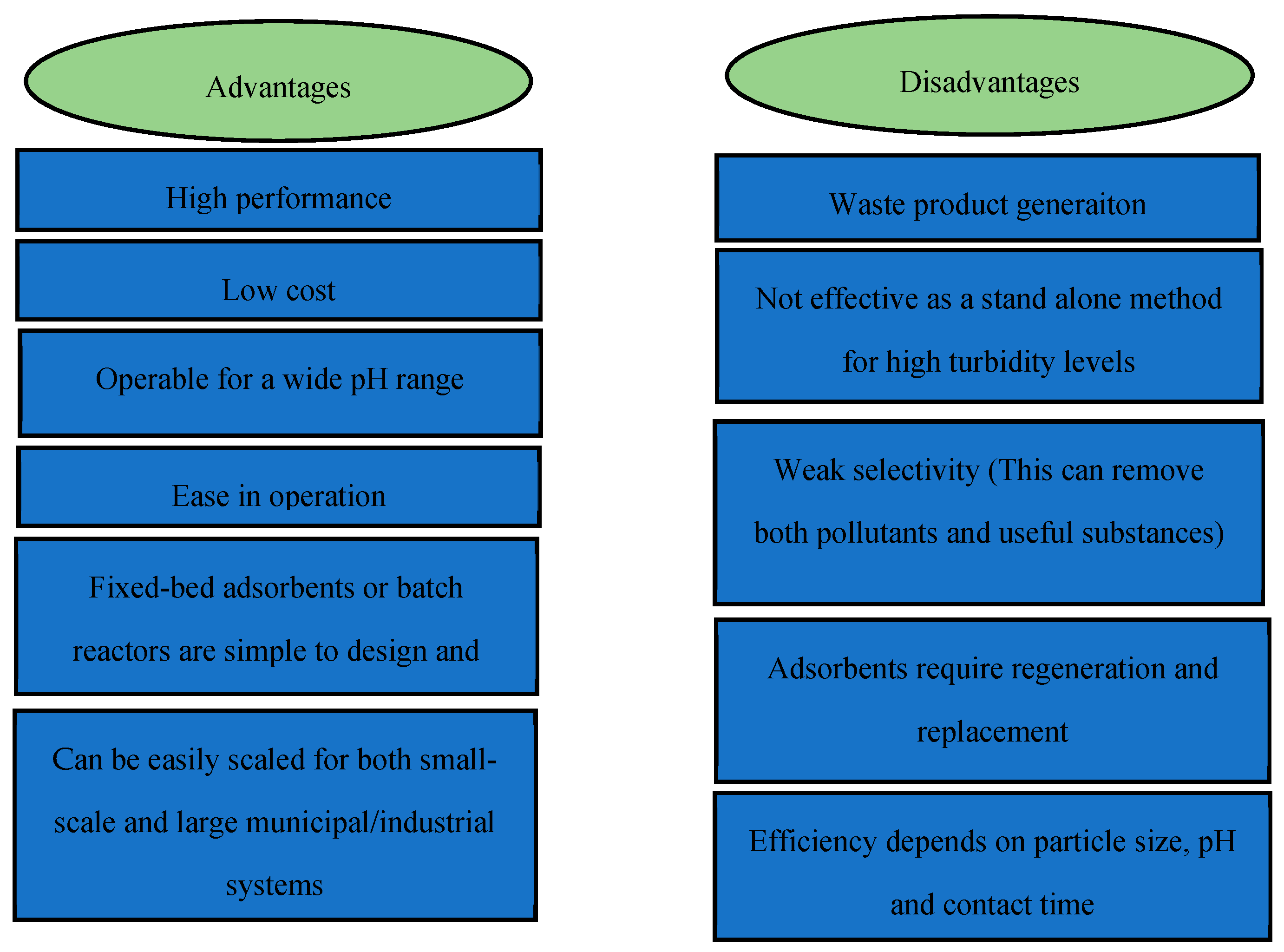

The following figure (

Figure 1) summarizes the overall merits and limitations [

35] of employing adsorption as an effective treatment technique for the removal of turbidity from water.

2.5. Membrane Based Technologies

This technology involves the separation of substances based on their particle sizes and pressure differentials across a semi-permeable membrane. This semi-permeable membrane functions as a physical barrier that allows a feed stream to pass through, effectively dividing it into two distinct streams: the permeate (filtered water) and the retentate (the concentrated stream containing the retained particles). To facilitate effective water filtration, the membrane is designed with varying pore sizes tailored to the specific particle size removal requirements. These pore sizes typically range from approximately 0.1 micrometers down to a few nano-meters. Additionally, pressure is required to drive the feed stream through the membrane. The driving force for the movement of the feed stream is the pressure difference between the two sides of the membrane [

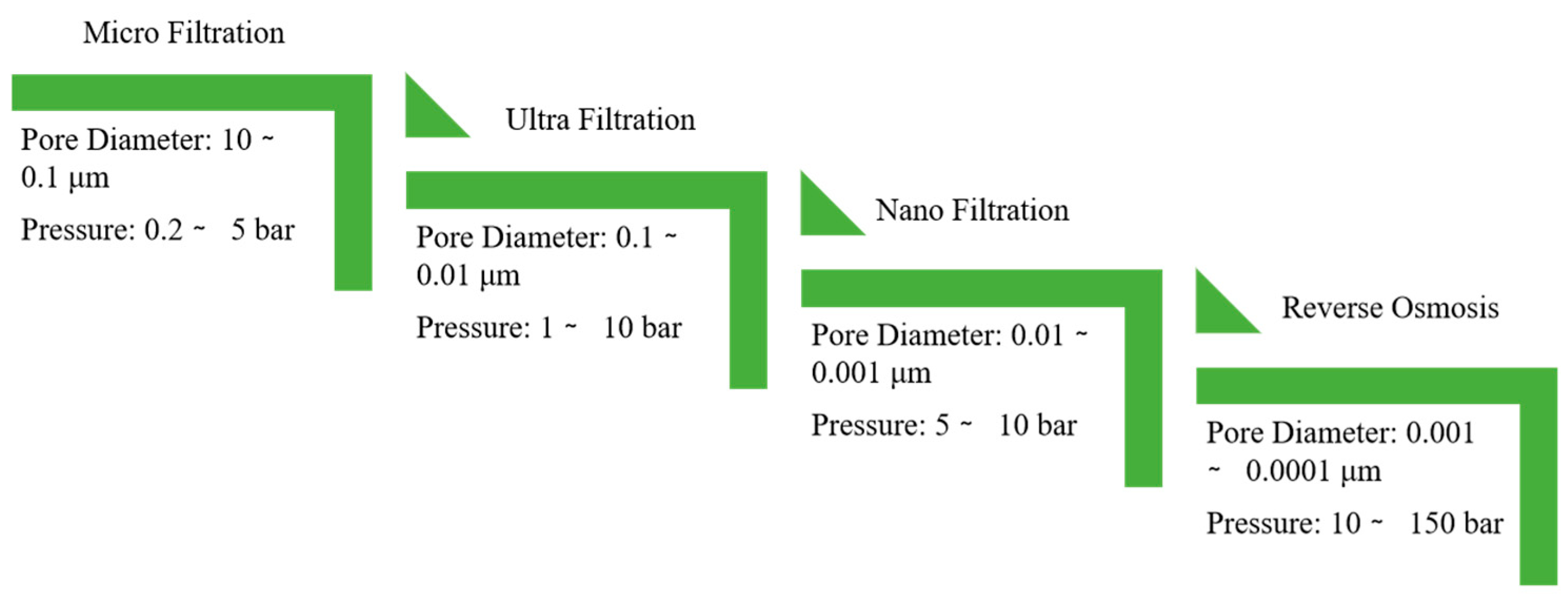

36].

Membrane filtration can be broadly categorized into reverse osmosis (RO), nanofiltration (NF), ultrafiltration (UF) and microfiltration (MF) techniques for the effective removal of turbidity. In many cases, a comprehensive water purification process may involve the sequential combination of these filtration methods. The nominal pore size and the relevant operating pressure for each membrane type is illustrated in

Figure 2.

In general, the water to be treated is first subjected to techniques such as coagulation (with flocculation) to remove larger particles that could potentially cause clogging of the membranes. In the context of turbidity removal, membrane filtration is particularly effective for treating water with lower turbidity levels. However, when water exhibits high turbidity, it is strongly recommended to apply appropriate pre-treatment techniques, as mentioned previously, to ensure the membranes can operate efficiently and maintain optimal performance over time.

2.5.1. Reverse Osmosis (RO)

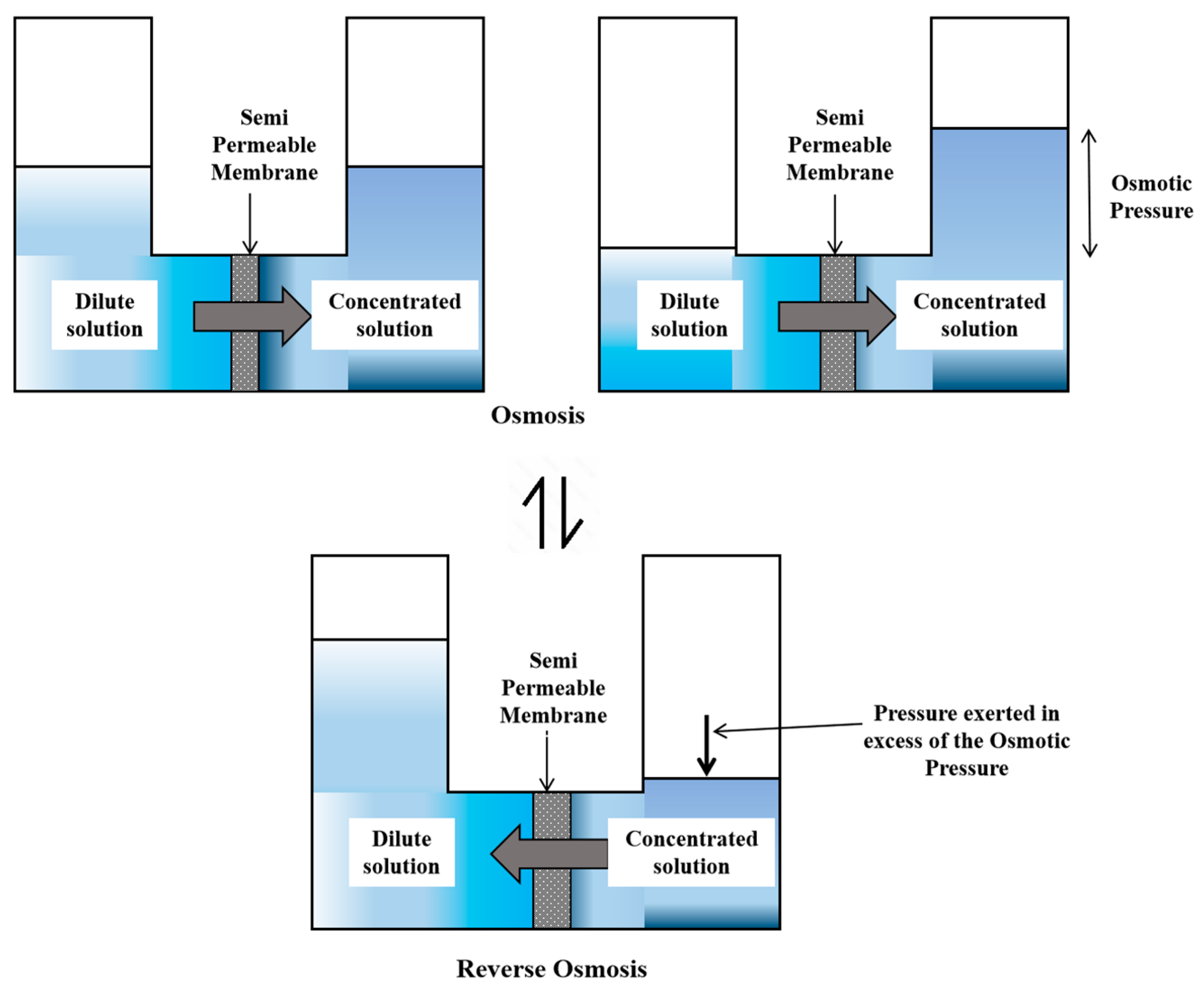

Reverse osmosis is a widely used membrane filtration technique that employs a semi-permeable membrane and applied pressure to remove impurities, particularly dissolved solids, organic matter, and ions from a solution. Osmosis naturally occurs when two solutions of differing concentrations are separated by a semi-permeable membrane; water molecules migrate from the weaker (dilute) solution to the stronger (more concentrated) solution until equilibrium is reached, as the membrane permits only water to pass through. However, in reverse osmosis, external pressure is applied to counteract and reverse this natural flow of water through the membrane. This forces water to move from the more concentrated solution to the weaker one, thereby retaining contaminants on one side of the membrane while allowing purified water to collect on the opposite side.

Figure 3 illustrates the overall processes of both osmosis and reverse osmosis [

37].

The resultant filtrate produced by reverse osmosis (RO) can be utilized for various applications such as drinking water or irrigation purposes. RO membranes are predominantly manufactured from polyamide materials or from natural and synthetic cellulose acetate compounds [

38]. Overall, RO is a highly effective treatment technique capable of producing water of superior quality while maintaining relatively low energy consumption. Although this method is considered environmentally friendly, proper maintenance is essential because RO membranes are susceptible to bacterial growth and contamination over time [

39].

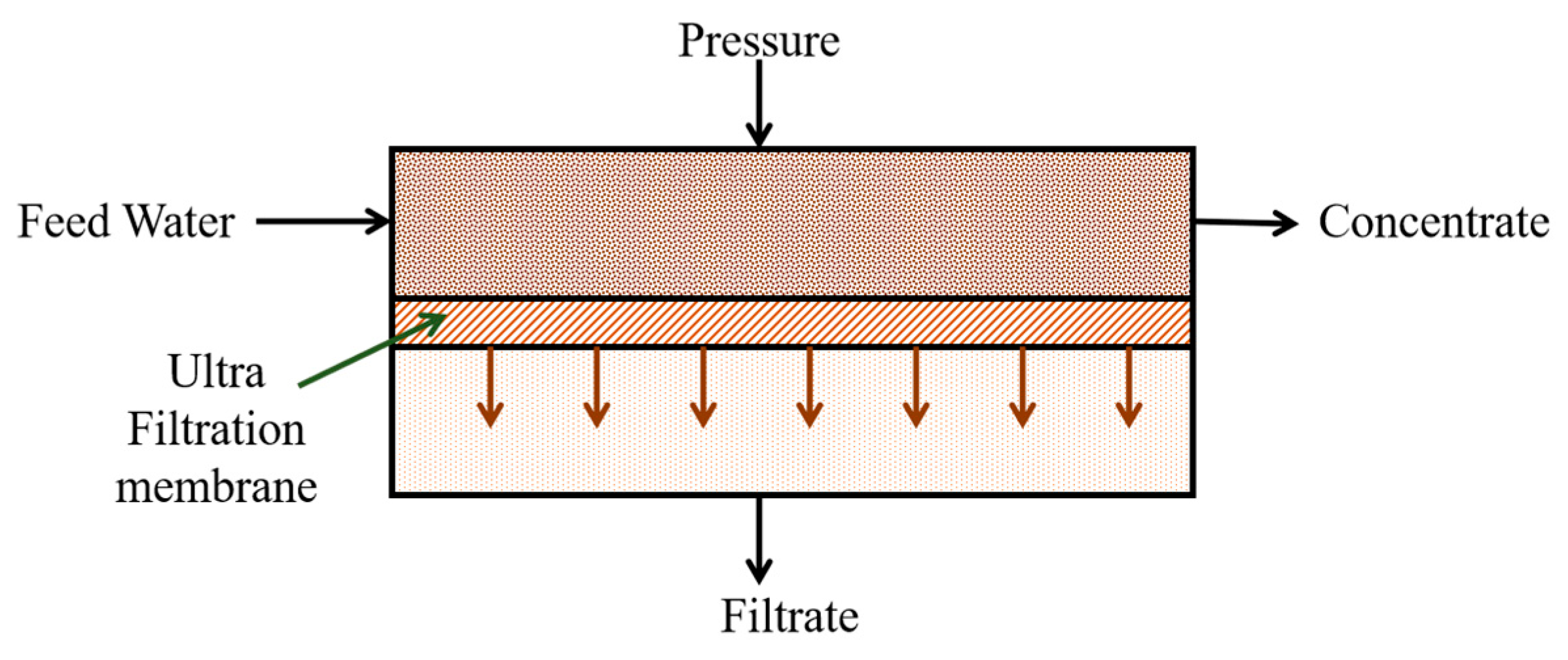

2.5.2. Ultrafiltration (UF)

In ultrafiltration, water is purified using membrane technology with pore sizes ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 μm, making it a suitable method for treating drinking water. As mentioned previously, ultrafiltration utilizes the pressure difference between the two sides of the membrane to drive the movement of small particles and contaminants whose diameters are smaller than the membrane’s pore size, from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side. This process allows water, inorganic salts, and other smaller substances to pass through the membrane, while effectively filtering out suspended solids, colloidal particles, and microorganisms [

40], as illustrated in

Figure 4.

In the context of turbidity removal, ultrafiltration (UF) demonstrates a high turbidity removal efficiency, producing effluent water of consistently stable and reliable quality. UF membranes are generally composed of polymeric materials such as polysulfone and polyethersulfone, which possess favorable characteristics including good mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and thermal stability, all of which positively impact water treatment performance. Key design parameters, such as membrane material, pore size, and module configuration (hollow fiber, spiral wound, plate and frame, or tubular), are carefully optimized according to the feed water properties to maximize filtration efficiency while minimizing fouling, a major challenge associated with membrane filtration [

38]. Typically, for the complete removal of pathogens and viruses in raw water, disinfection is done prior to UF [

41] which is more energy efficient compared to conventional treatment processes [

40]. Furthermore, a case study conducted at the San Juan Reservoir Water Treatment Plant in Chongon, Ecuador, which faces high turbidity levels, elevated bacterial loads, and seasonal algae blooms, demonstrated that ultrafiltration is a significantly more cost-effective water treatment method than traditional conventional techniques [

42].

2.5.3. Microfiltration (MF)

Microfiltration membranes operate similarly to ultrafiltration membranes, except that their pore sizes range from 0.1 to 10 μm, which are larger than those of UF membranes [

43]. MF is classified as a low-pressure membrane process. These membranes are primarily used to retain suspended particles, functioning much like conventional coarse filters. MF membranes can moderately remove colloidal particles and suspended solids. They are typically made from materials such as high-density polyethylene, glass fiber-reinforced plastic, polypropylene, polycarbonate, or ceramics. Among these, ceramic-based MF membranes have been extensively studied and are recognized as a well-established technology for various industrial applications [

44]. One study focusing on high-turbidity environments found that the direct application of MF membranes was inefficient due to irreversible fouling. Consequently, pre-treatment methods such as coagulation were employed, resulting in improved flux and reduced membrane fouling. Additionally, turbidity removal efficiency increased significantly with pre-treatment [

45]. Another case study involving Karstic Spring water reported promising results using MF membranes in managing elevated turbidity levels [

46]. While MF membranes possess the largest pore sizes among membrane technologies, they serve effectively as an intermediate filtration step between UF membranes and granular media filtration. Furthermore, a 2019 pilot-scale study utilizing a submerged, flat ceramic MF membrane combined with a hybrid coagulation-membrane module demonstrated that the permeate exhibited high water quality, with turbidity levels as low as 0.2 NTU and reduced membrane fouling [

47].

Overall, the effectiveness of membrane filtration techniques, like any unit treatment process, is largely influenced by the characteristics of the source water. For instance, while reverse osmosis (RO) is highly efficient in eliminating dissolved salts and minerals, microfiltration (MF) and ultrafiltration (UF) are particularly effective in the removal of microorganisms and suspended solids. Consequently, when selecting an appropriate membrane filtration system, factors such as the specific contaminants present in the water, the operational flow rate, and the desired level of purification must be carefully evaluated [

38]. Although membrane filtration is not a novel concept, the evolving composition and complexity of pollutants in water bodies has necessitated continuous advancement in this technology with respect to performance efficiency, energy consumption, permeate quality, and operational sustainability [

48]. Significant developments are being made in membrane module design and membrane material engineering, particularly aimed at minimizing membrane fouling—one of the primary challenges in membrane applications [

49]. Additionally, there has been notable progress in integrating membrane processes with each other, or with pretreatment methods such as coagulation or adsorption, which are being continually refined and successfully applied across a wide range of water and wastewater types [

48]. For example, a hybrid system combining nanofiltration and RO membranes was employed for the treatment of distillery wastewater, resulting in high removal efficiencies of 99.8% for total dissolved solids, primarily due to the effectiveness of the RO stage [

50]. Therefore, membrane technology continues to evolve as a versatile and efficient approach for the removal of various contaminants contributing to turbidity in water and wastewater treatment systems.

3. Emerging Techniques to Remove Turbidity

Conventional treatment techniques have been widely adopted for the removal of turbidity in water. However, due to several significant drawbacks associated with these methods, such as the production of toxic sludge, strict operating conditions and parameters, clogging of filter media, and other limitations, alternative approaches have emerged alongside ongoing technological advancements. These modern techniques have been developed specifically to address the shortcomings of traditional treatment methods. They include nanotechnology-based methods, electrocoagulation, advanced oxidation processes, and various hybrid technologies. The primary objectives of these innovative approaches are to enhance sustainability, reduce costs, and improve environmental friendliness, especially in light of the increasing water demand that necessitates greater water reuse. This section introduces a selection of the latest advancements in turbidity removal technologies, outlining their fundamental principles, key advantages and limitations, as well as relevant case studies associated with each technology.

3.1. Nano Technology Based Methods

In recent years, with the advancement of emerging research fields, nanotechnology has emerged as a highly promising approach for the removal of turbidity. The use of nanomaterials is becoming increasingly popular due to their unique properties, including large surface area (which facilitates fast dissolution, high reactivity, and strong sorption) [

51], enhanced mechanical stability, and excellent solution mobility, making them a far superior option compared to conventional materials [

52]. These nanomaterials are specifically being engineered to target and capture contaminants responsible for causing turbidity [

17]. Among various nanotechnology-based techniques, the application of nano-adsorbents, nano-membranes, and nano photocatalysts has shown great potential in water and wastewater treatment. This treatment approach offers higher efficiency, greater flexibility, multifunctionality, and affordability. Consequently, nanotechnology has proven to be both environmentally friendly and innovative. However, a significant limitation remains: most research on nanotechnology applications has been conducted at a small laboratory scale, with limited large-scale or field studies to date [

53].

3.1.1. Nano Adsorbents

Adsorption is a physicochemical process whereby molecules from gases or solutions are attracted to and accumulate on the surface of a solid material upon close contact. The molecules undergoing adsorption are termed adsorbates, while the solid materials serving as the adsorption sites are known as adsorbents. When adsorption is integrated with nanotechnology, the resulting nano-adsorbents exhibit significantly enhanced adsorption capacities for the removal of various contaminants. These nano-adsorbents demonstrate superior efficiency in decontamination processes compared to conventional adsorbents. Moreover, the application of nanotechnology in water and wastewater treatment offers advantages such as reduced system footprint, making it highly suitable for decentralized or point-of-use treatment systems [

52]. Various classes of nano-adsorbents have been developed, including carbon-based nanomaterials, metal-based nanoparticles, metal oxide nanoparticles, polymer-based nanoparticles, zeolites, nanocomposites, and bio-adsorbents [

54].

Table 2 summarizes representative examples of these nano-adsorbents along with their key characteristics.

Table 3 below shows a few case studies which were done using nano adsorbents and the affects they had on the turbidity levels.

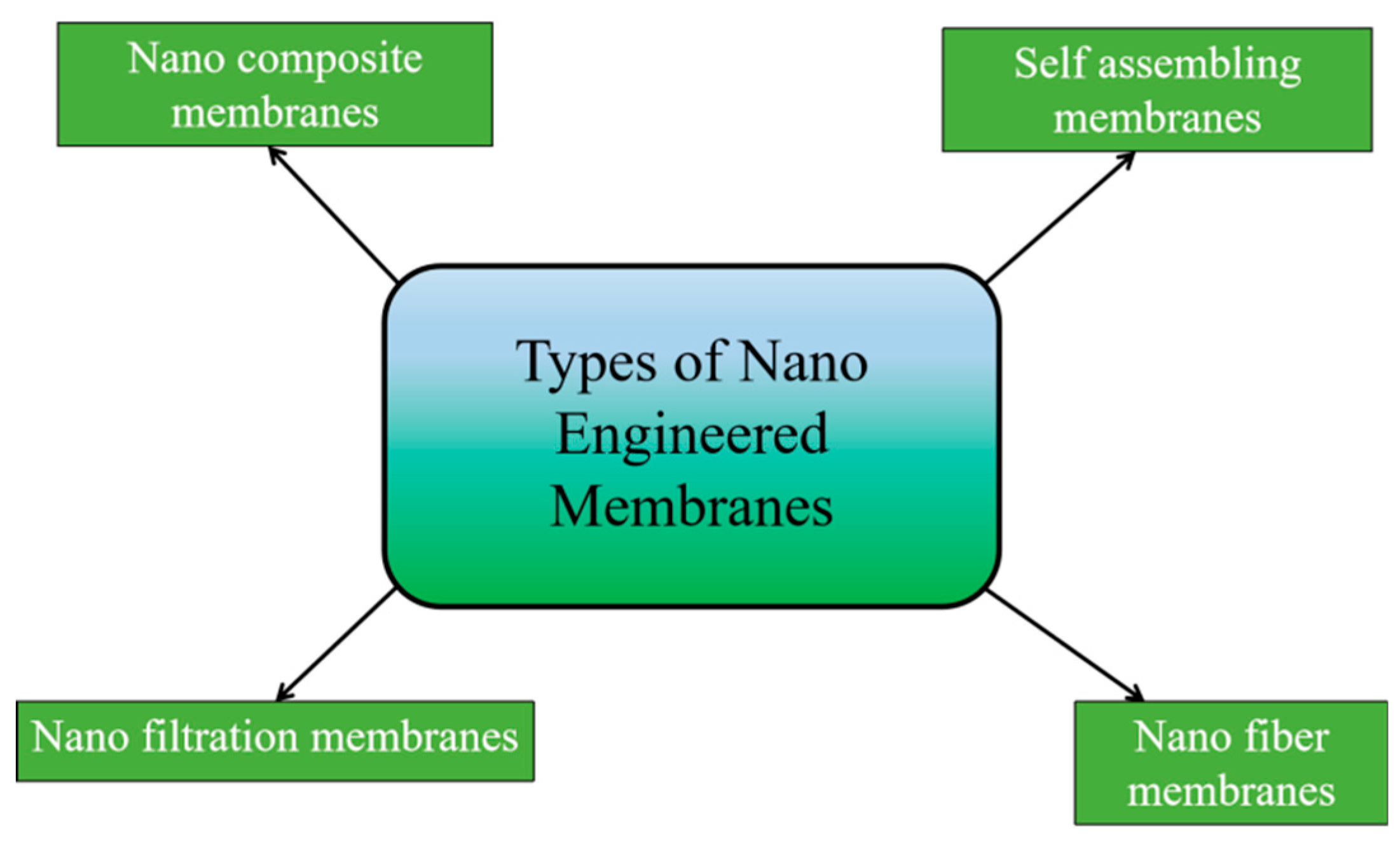

3.1.2. Nano Engineered Membranes

Nanofiltration Membranes

Nanofiltration (NF) membrane technology is a relatively recent approach introduced for water and wastewater treatment. These membranes possess very small pore sizes, typically around 1 nanometer. While NF is a pressure-driven process similar to other membrane types, though operating at relatively low pressures, it also incorporates a unique charge-based repulsion mechanism. This mechanism enables selective permeability, allowing monovalent ions to pass through reasonably well, while predominantly retaining multivalent ions. Consequently, NF membranes are highly effective for separation and selective removal of solutes in various process streams [

64]. NF membranes can be applied to treat multiple types of water, including groundwater, surface water, and wastewater, efficiently removing turbidity, microorganisms, hardness, and other contaminants [

65].

Figure 5.

Types of nano engineered membranes.

Figure 5.

Types of nano engineered membranes.

Nanocomposite Membranes

Nanocomposite membranes are fabricated by incorporating nanomaterials into the membrane matrix to enhance structural and functional properties. They have shown great promise in turbidity removal due to advantageous features such as increased hydrophilicity, self-cleaning ability, high porosity, improved permeability, and enhanced anti-fouling characteristics. Common nanomaterials used in the development of these membranes include zeolites and metal oxides such as TiO₂, Al₂O₃, and SiO₂ [

66]. The addition of metal oxides contributes to improved mechanical and thermal stability, while materials like zeolites enhance membrane hydrophilicity [

52]. Therefore, nanocomposite membranes represent a significant class of materials in the field of water and wastewater treatment, particularly for effective turbidity removal.

Self-Assembling membranes

Self-assembling membranes, developed using nanotechnology, represent an innovative class of membrane materials in which advanced structures are formed through the spontaneous organization of nanoparticles into defined patterns or architectures without direct human intervention [

67]. This approach is typically implemented using block copolymers, resulting in the formation of block copolymer membranes. The self-assembly process is driven by specific molecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding [

68], van der Waals forces, electrostatic attractions, or hydrophobic effects [

69]. Notably, the internal structure and morphology of these membranes can be tailored or customized to meet specific performance requirements or targeted applications [

51].

Nano Fiber Membranes

Nanofibers possess diameters on the nanometer scale and are typically produced from various types of polymers. The diameter of the resulting nanofibers can vary depending on the specific polymer used and the production technique employed. Common fabrication methods include electrospinning, drawing, and template synthesis, among others [

70]. Among these, electrospun nanofiber membranes have demonstrated enhanced efficiency in removing contaminants from water sources [

71]. This approach is particularly effective when combined with pre-treatment techniques, where parameters such as color and turbidity are initially reduced. Subsequently, the partially treated effluent can be passed through these membranes for further turbidity removal and improved water quality [

72].

3.1.3. Nano Photocatalysis

Nanophotocatalysis is a type of Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) that employs nanoparticles—typically metal oxides, for the effective removal of contaminants from water. (Photocatalysis is discussed in greater detail under section 3.3 - AOPs.) Nanomaterial-based photocatalysts exhibit distinct behaviors compared to their bulk counterparts, primarily due to unique quantum effects and enhanced surface properties. These characteristics significantly improve their electrical, mechanical, magnetic, and chemical reactivities, as well as their optical properties [

73]. Research has shown that nanocatalysts can enhance oxidation potential by efficiently generating reactive oxidizing species on their surfaces, facilitating the degradation of various pollutants in water [

74]. Therefore, nanotechnology-based treatment methods offer a highly promising and efficient solution for turbidity removal, combining large surface area, high reactivity, and advanced contaminant degradation capabilities.

While nanotechnology offers groundbreaking potential for turbidity removal, transitioning from laboratory-scale innovations to real-world applications remains challenging, primarily due to the high costs associated with implementing such advanced techniques. Low- and middle-income countries often face barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, limited technical capacity, and substantial upfront investment requirements. Operating and maintaining these sophisticated treatment systems can also pose significant difficulties. Furthermore, the release of nanoparticles into the environment warrants careful management, as unintended ecological impacts may occur. Additional research is needed to address these challenges, including the development of effective mitigation strategies. Key priorities should include ensuring long-term operational stability under dynamic pollutant compositions, enhancing the regeneration and reuse of nanoparticles rather than discharging them, and exploring the integration of nano-based methods with existing treatment infrastructures to improve feasibility and scalability.

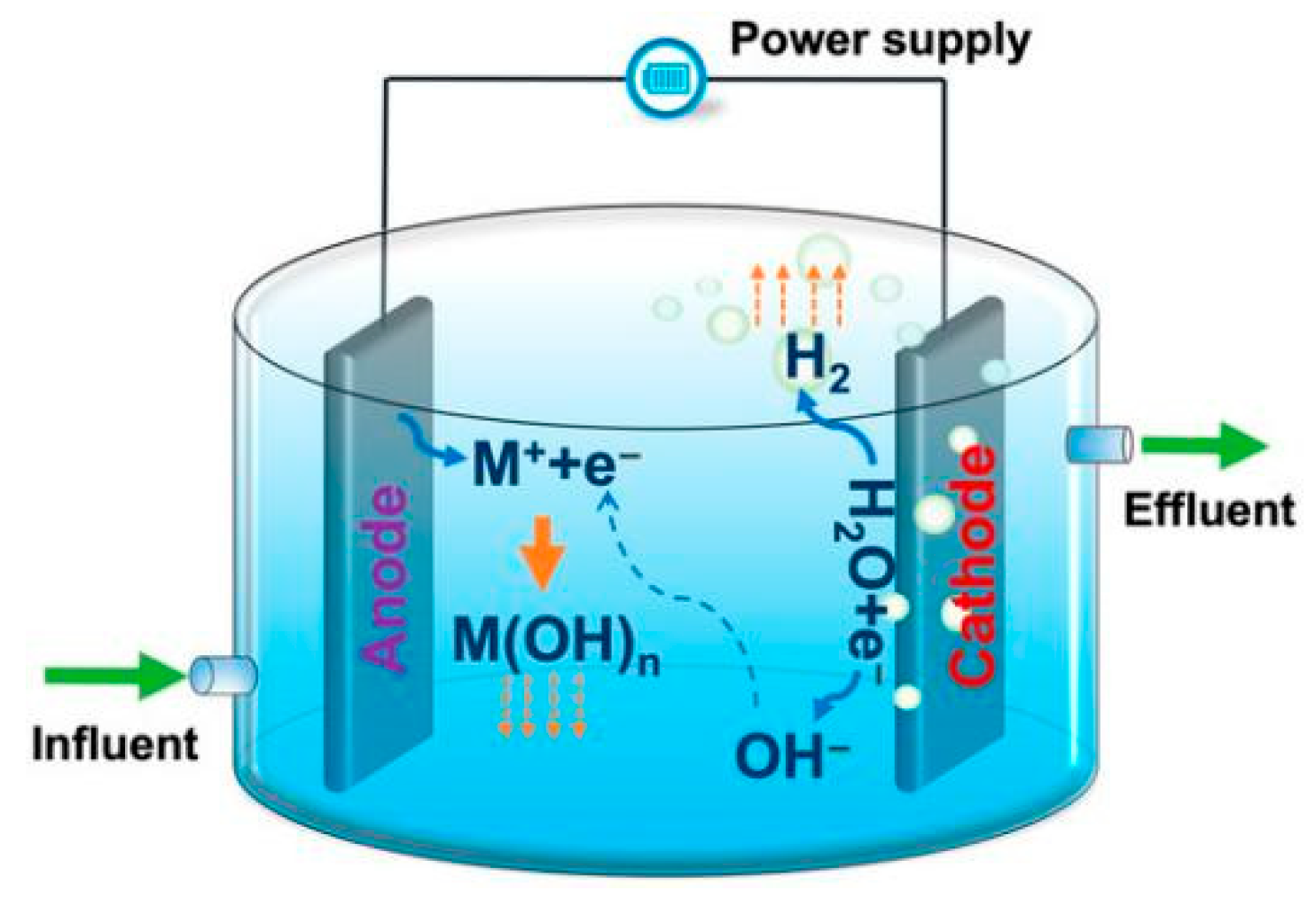

3.2. Electro-Coagulation (EC)

Electrocoagulation is considered an advanced and improved alternative to the conventional coagulation/flocculation processes commonly used in water and wastewater treatment. In this technique, an electric current is applied to the water, resulting in the release of metal ions, typically iron or aluminum, from sacrificial electrodes. The setup involves two electrodes: an anode and a cathode, where simultaneous electrochemical reactions take place. Specifically, upon application of current, the anode undergoes oxidation, releasing metal ions into the solution. Concurrently, water is reduced at the cathode, generating hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions [

75]. The released metal ions then react with the hydroxide ions to form metal hydroxides, which serve as effective coagulants. These metal hydroxides destabilize suspended particles by neutralizing their surface charges, thereby promoting the aggregation of particles into larger flocs. These flocs can subsequently be removed through flotation, sedimentation, or filtration processes. Consequently, particles responsible for turbidity can be efficiently eliminated through this mechanism [

76,

77]. Compared to traditional chemical coagulation, EC is more environmentally friendly and often more cost-effective. The following figure (

Figure 6) illustrates the overall electro coagulation process using generic metal electrodes (M) [

78].

Accordingly, the following reactions occur during the electrolysis process [

78];

The release of metal ions (M) due to electrolytic oxidation of sacrificial anode is shown by Equation (1):

The formation of hydroxyl ions occurs at the cathode (which is a concurrent process with the anode) represented by Equation (2):

The reaction between the metal ions and the hydroxyl ions forming monomeric and polymeric species is illustrated by Equations (3) and (4):

Several factors significantly influence the performance and efficiency of the electrocoagulation (EC) process. These include the type of electrode material, the applied voltage or current, both of which directly impact the rate of electrode dissolution, and the duration of electrolysis. Typically, longer electrolysis times lead to higher removal efficiencies. Additionally, the initial pH of the water plays a crucial role in determining the overall effectiveness of the process. Electrode spacing is another important parameter, as the distance between electrodes affects the strength of the electric field and, consequently, the treatment efficiency. Optimizing these operational parameters is essential to achieving maximum turbidity and contaminant removal [

79,

80,

81]. Electrocoagulation has gained considerable attention as a promising technique for water and wastewater treatment, leading to extensive research focused on a range of water quality parameters, among which turbidity has frequently been investigated under varying conditions.

Rahmani (2008) [

82] conducted an experiment to evaluate turbidity removal from water using three types of electrodes, aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), and stainless steel (St), under varying voltages (10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 V), with an initial pH of 7.5 and electrode spacing of 2 cm. It was observed that at a voltage of 20 V and an electrolysis time of 20 minutes, aluminum electrodes achieved the highest removal efficiency of 93%, outperforming Fe and St electrodes. Similarly, Kobaya et al.,(2013) [

83] investigated the influence of current density on turbidity and chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal from potato chips manufacturing wastewater. The results indicated that an increase in charge loading enhanced turbidity removal efficiency from 56% to 98%. Zailani et al., (2017) [

81] compared various studies on EC and conventional coagulation-flocculation methods for leachate treatment. Their analysis identified current density as the primary influencing factor in EC performance. Shivayogimath et al., (2013) [

84] reported that under optimized conditions, electrolysis time of 35 minutes, cell voltage of 9 V, and pH 5.8, the turbidity removal efficiency in solid waste leachate treatment reached approximately 97%. Sadeddin et al., (2010) [

85] examined turbidity and total suspended solids (TSS) removal from RO feed water using iron electrodes in an EC system. By optimizing current density and electrolysis time, turbidity was reduced from 150 NTU to below the standard RO feedwater quality, with an efficiency exceeding 98%. In another study evaluating EC for produced water treatment, turbidity was initially reduced from 160 NTU to 70 NTU (a 44% reduction). When followed by centrifugation, the combined treatment achieved over 99% turbidity removal, indicating the potential of EC for increased treatment performance in various wastewater types [

86]. Moreover, Behara et al., (2023) [

87] studied the application of EC for treating oil-contaminated wastewater collected from the Haldia industrial region of India, which was characterized by high concentrations of inorganic matter, suspended solids, and turbidity. Two response surface methodology (RSM) techniques, Box-Behnken Design (BBD) and Central Composite Design (CCD), were employed to optimize key operational parameters such as pH, initial oil concentration, current density, and electrolysis time [

88,

89]. Under optimal conditions (pH 7.5, initial oil concentration 275 mg/L, current density 17.5 mA/cm², and electrolysis time of 20 minutes), turbidity removal efficiencies of 80% and 93% were achieved using BBD and CCD, respectively. Notably, CCD was able to reduce turbidity from 450 NTU to 56 NTU, outperforming BBD. In drinking water treatment, although electrocoagulation process has been researched for many years, they have been in use in small scale or mobile units and electrode management and energy demand have been challenging [

90] and further research is needed. For example, the electrocoagulation (EC) unit described in [

90] has been successfully implemented in a small remote village in Sri Lanka at a cost of AUS

$ 8.20 per 1 kL in 2012. However, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB) of Sri Lanka has expressed reservations about adopting this technology more widely in their schemes without further research, citing concerns about the potential release of aluminium from the electrodes into the treated water. Consequently, the EC unit was eventually replaced with a reverse osmosis (RO) system. after two years of service. As a result EC methods have not yet been widely adopted at large municipal scale drinking water treatment plants. In summary, electrocoagulation has been extensively studied and demonstrates significant potential as a robust and effective method for turbidity removal across a wide range of water and wastewater treatment applications.

Thus, based on the above-mentioned case studies, electrocoagulation has demonstrated high effectiveness in turbidity removal across a wide range of water and wastewater matrices, owing to its capability for in-situ generation of coagulants. This technique can be tailored for specific treatment needs through the selection of suitable electrode materials and optimization of operational parameters. However, several research gaps and challenges remain that must be addressed to facilitate broader practical adoption, particularly at large scales. The presence of byproducts and residual metals, such as aluminum or iron, in treated water poses potential health and regulatory concerns, necessitating advanced monitoring and mitigation strategies. While laboratory-scale implementation is relatively straightforward, scaling up to full-scale applications may present operational and economic challenges. Therefore, further research is essential to achieve reliable large-scale implementation with long-term operational stability and cost-effectiveness under real-world conditions.

3.3. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs)

Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) represent a class of emerging treatment technologies that utilize hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which possess one of the highest redox potentials among known oxidants [

91]. These radicals exhibit the remarkable ability to accelerate oxidation processes [

92] and effectively degrade a wide spectrum of contaminants, including both organic and inorganic substances that contribute to turbidity, such as suspended solids, colloidal matter, natural organic matter (NOM), and complex micropollutants, present in water systems [

93,

94,

95]. Once generated, hydroxyl radicals react in a non-selective manner with these pollutants, leading to their fragmentation and subsequent conversion into less harmful end products such as carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic salts. The formation of hydroxyl radicals can be facilitated through the application of one or more primary oxidants, including ozone, hydrogen peroxide, and molecular oxygen, in combination with energy sources like ultraviolet (UV) radiation or catalysts such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂) [

96]. Several configurations of AOPs have been explored for the effective removal of turbidity. These include photocatalysis, ultraviolet radiation combined with hydrogen peroxide, ozonation with hydrogen peroxide, and Fenton-based reactions.

3.3.1. Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is a type of Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) that utilizes photocatalysts, semiconductor materials,to facilitate the removal of various pollutants from water systems. Commonly used photocatalysts include titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and zinc oxide, which are capable of accelerating chemical reactions upon exposure to an appropriate light source. These semiconductors possess the inherent ability to generate electron–hole pairs when photons with sufficient energy strike their surface. Upon light irradiation, these electron–hole pairs are formed and subsequently migrate to the photocatalyst surface, where they interact with water molecules and dissolved oxygen to produce highly reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS initiate a series of redox reactions, leading to the effective degradation of organic pollutants, disinfection of microbial pathogens, and the breakdown of complex contaminants, including those responsible for turbidity [

97,

98].

Several research investigations have evaluated the application of photocatalysis for turbidity reduction in various wastewater types. One such study examined biologically treated wastewater using TiO₂ as the photocatalyst. When the photocatalytic process was conducted under natural sunlight, a maximum turbidity removal efficiency of 71.6% was achieved with a catalyst concentration of 60 mg/L TiO₂. In contrast, samples treated with lower TiO₂ concentrations exhibited correspondingly lower turbidity removal efficiencies. Therefore, it can be concluded that higher photocatalyst concentrations generally lead to improved turbidity removal performance [

99]. Another study focused on municipal wastewater treatment using the same photocatalyst, TiO₂. Under optimized reaction time and catalyst loading conditions specifically determined for the study, a turbidity removal efficiency of 95.17% was attained. Additionally, a comparative assessment of ultraviolet (UV) light and visible light irradiation revealed that UV light achieved significantly higher turbidity removal efficiencies in this setup [

100].

Furthermore, the performance of a solar photocatalytic reactor was investigated as a pre-treatment step to control membrane fouling in wastewater treatment. Using UV light in combination with TiO₂, turbidity removal efficiencies approaching 95% were observed [

101]. Collectively, these case studies demonstrate that TiO₂ is an effective photocatalyst for turbidity removal across various types of wastewater.

3.3.2. UV/Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

The UV/H₂O₂ process is a homogeneous Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) in which photons from the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum interact with hydrogen peroxide molecules, leading to the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [

102], as illustrated in the following chemical Equation (5):

Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) requires external activation to generate hydroxyl radicals effectively. Ultraviolet (UV) photons, possessing high energy, serve as a reliable source to induce the disproportionation of H₂O₂. The rate of photolysis of H₂O₂ depends primarily on the intensity of the UV radiation, with the quantum yield of H₂O₂ decomposition being approximately 0.5 under UV irradiation at 254 nm. Solar radiation can also be employed as a light source; however, the photocatalytic reaction rate under solar light is generally lower compared to that achieved with UV lamps. Several factors influence the overall efficiency of this process, including the concentrations of organic and inorganic constituents, the light transmittance of the solution, pH, temperature, and the dosage of H₂O₂. Regarding dosage, excessive amounts of H₂O₂ can act as hydroxyl radical scavengers, thereby reducing the oxidation rate. Conversely, insufficient H₂O₂ dosage results in inadequate hydroxyl radical formation, which similarly diminishes the oxidation efficiency [

103,

104,

105].

The UV/Hydrogen Peroxide (UV/H₂O₂) process is primarily recognized for its ability to degrade dissolved organic contaminants, such as natural organic matter (NOM) and biofilm particles, as well as for microbial disinfection. This makes it an indirect but effective technique for turbidity reduction. It significantly decreases the concentration of pollutants that contribute to turbidity by breaking down finer colloidal particles and organic matter that cannot be effectively removed by conventional sedimentation or filtration methods [

106]. Occasionally, certain turbidity-causing particles may interfere with coagulation or pass through filtration units, and these can be effectively removed through this AOP [

107]. Although UV/H₂O₂ is not typically employed as a standalone treatment process, it can substantially enhance subsequent coagulation and filtration steps by further degrading residual pollutants into smaller, less light-scattering compounds. This results in improved water clarity and overall turbidity reduction.

3.3.3. Ozone/Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

Ozone/Hydrogen Peroxide (O₃/H₂O₂), commonly referred to as the Peroxone process, is an advanced oxidation process (AOP) similar to the UV/H₂O₂ method, with the key difference being the use of ozone instead of ultraviolet light. The combination of ozone and hydrogen peroxide enhances the removal efficiency of pollutants compared to ozone oxidation alone. Additionally, this synergistic effect allows for the use of lower ozone dosages, resulting in significant cost reductions. The following chemical Equations (6) and (7) illustrate the generation of hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide through its interaction with ozone (O₃) [

108]. These highly reactive hydroxyl radicals subsequently degrade the substances responsible for turbidity in water.

The reaction rate of the Ozone/H₂O₂ process depends on several factors, including the concentrations of ozone and hydrogen peroxide, pH, temperature, and the presence of specific ions in the water matrix. Similar to the UV/H₂O₂ process, both excessively high and very low dosages of hydrogen peroxide are not recommended, as they can adversely affect the oxidation rate. Therefore, the concentrations of ozone, hydrogen peroxide, and the treatment duration must be carefully optimized to achieve maximum removal efficiency [

108]. Optimal performance is generally observed at neutral to slightly alkaline pH values, which promote the enhanced production of hydroxyl radicals. This process is particularly favored for water treatment scenarios where UV transmission is limited, and UV-based AOPs are less feasible [

109]. The Ozone/H₂O₂ system has been successfully applied in various treatment contexts, including groundwater, surface water, and wastewater treatment [

108]. While sharing similar advantages with the UV/H₂O₂ process, this technique also aids in particle destabilization and aggregation, thereby further improving water quality. A study conducted by Paode et al.,(2008) [

110] demonstrated that particle destabilization can occur at a wide range of dosages, while particle aggregation is significantly enhanced when the ozone/peroxone process is combined with alum coagulation. Consequently, this approach represents a potentially effective method for turbidity reduction in water treatment applications.

3.3.4. Fenton Processes

The Fenton process is an Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) that utilizes hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) in combination with iron ions (Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺) to generate highly reactive hydroxyl (•OH) and hydroperoxyl (•O₂H) radicals. These radicals possess strong oxidative potentials capable of decomposing a wide range of pollutants. The Fenton process has attracted considerable attention due to the rapid reactions between iron and hydrogen peroxide, as well as its ability to operate efficiently under ambient temperature and pressure conditions. This process is predominantly employed as a pre-treatment step within water and wastewater treatment plants, facilitating the degradation of complex organic matter into intermediate species, which can subsequently be further oxidized into non-toxic carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic salts, where applicable [

111,

112]. The general reaction mechanisms for the Fenton process are presented below (8,9):

According to the two equations presented above, Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions react with hydrogen peroxide to generate hydroxyl radicals. Typically, Fe²⁺ acts as the primary catalyst in this process and has the ability to regenerate Fe³⁺; however, the regeneration of Fe²⁺ from Fe³⁺ occurs at a significantly slower rate [

113,

114]. Several factors influence the efficiency of particle degradation by these radicals, with pH, reaction time, and the concentrations of Fe and H₂O₂ being the most critical parameters [

114,

115]. Careful optimization of the Fe/H₂O₂ ratio is essential, as excessive concentrations of either reagent can inhibit the overall reaction efficiency. The relevant reaction mechanisms are illustrated in the following Equations (10)–(14):

The Fenton process is typically limited by the regeneration rate of Fe²⁺ ions, as the conversion of Fe³⁺ back to Fe²⁺ is very slow. Therefore, the pH must be carefully maintained within an optimal range of approximately 2.8 to 3.0 [

111], where both Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions remain stable and active. To maximize the production of hydroxyl radicals, precise balancing of the aforementioned parameters is essential. Since the process generates highly reactive and non-selective oxidizing radicals, their continuous production is required to sustain effective pollutant degradation.

Several studies have investigated the application of the Fenton process, although it has rarely been employed as a standalone method specifically for turbidity removal. João et al,. (2020) [

116] explored the use of ultrasound-assisted Fenton processes for treating swine wastewater, examining the effects of parameters such as pH, contact time, and H₂O₂ concentration on the removal of color, turbidity, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), and Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD₅). At an optimal pH of 3 and H₂O₂ concentration of 90 mg/L, a turbidity removal efficiency of 98.2% was achieved. In another study, the Fenton process was combined with conventional coagulation and flocculation using ferric chloride as the coagulant to treat stabilized landfill leachate, resulting in nearly complete turbidity removal, up to 100% [

117]. Similarly, this combined treatment approach was applied to textile industry effluent, assessing the reduction in color, turbidity, and COD at two pH values (6.0 and 7.0). Turbidity levels were reduced to 0.8 NTU and 0.94 NTU, respectively, indicating highly effective treatment [

118]. A recent study by Zaman et al., (2024) [

119] focused solely on the Fenton reaction to evaluate removal efficiencies of COD, BOD₅, Total Organic Carbon (TOC), and turbidity in wastewater from pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. After adjusting the pH to 7.0, turbidity was reduced by 99.55%, confirming that the Fenton process is highly effective for turbidity removal, both as a standalone technique and when combined with other conventional treatment methods.

Fenton processes have been further enhanced by integrating electrochemical methods, giving rise to the Electro-Fenton process. In this approach, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) is produced in situ via the two-electron reduction of dissolved oxygen on the cathode surface within an acidic solution during the electrochemical reaction. Simultaneously, Fe²⁺ ions are regenerated through the reduction of Fe³⁺ at the cathode, sustaining the catalytic cycle [

120]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the Electro-Fenton process. For instance, one investigation focused on treating wastewater generated by the coconut processing industry, reporting a turbidity removal efficiency of approximately 85% [

121]. Another study applied the Electro-Fenton process to aquaculture effluent, achieving a turbidity reduction close to 88.7% [

122]. Overall, these findings confirm that Electro-Fenton processes are efficient and promising methods for reducing turbidity in various water and wastewater matrices.

It is important to note that most Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), including the Electro-Fenton method, cannot typically be used as standalone treatment techniques for turbidity removal, especially when turbidity levels are very high. Consequently, AOPs are often combined with conventional treatment methods to enhance overall turbidity removal efficiency.

While AOPs demonstrate considerable potential for turbidity reduction across diverse water and wastewater matrices, most studies focus primarily on laboratory-scale applications. Full-scale demonstrations under variable field conditions remain limited and uncommon. The scalability of AOP systems for treating high turbidity influent, especially in resource-limited settings, has not been comprehensively addressed. Moreover, the majority of research emphasizes the degradation of organic matter, with turbidity removal often considered a secondary outcome. Therefore, dedicated investigations must be conducted to specifically target the removal of turbidity-causing constituents. Currently, AOPs lack uniform, standardized testing protocols for turbidity-focused AOP performance analysis. Hence, such standardized protocols must be established to ensure consistent evaluation and comparison across studies.

3.4. Hybrid Technologies of Removing Turbidity

To achieve more productive and enhanced turbidity removal efficiencies, the implementation of hybrid treatment systems has recently emerged as a promising technological pathway. These approaches involve the combination of two or occasionally more than two distinct treatment processes integrated into a single, cohesive process configuration. The specific arrangement and sequence of these combined processes depend on factors such as the characteristics of the water source, the targeted treatment objectives, and the operational requirements of each component. For instance, some processes within a hybrid system are primarily designed to remove particular contaminants, thereby complementing each other’s effectiveness. Generally, hybrid technologies integrate physical, chemical, and biological methods to maximize treatment performance. However, careful consideration and optimization of each individual process are essential, as numerous operating parameters can significantly influence the overall treatment efficacy. Some examples of widely studied and applied hybrid technologies are listed below:

Coagulation (with Flocculation) + Membrane Filtration

Coagulation + Ballasted Flocculation

Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) + Coagulation

Ultrasound-Assisted Coagulation

3.4.1. Coagulation (with Flocculation) with Membrane Filtration

The use of coagulants for water treatment, despite being highly efficient in removing many contaminants, may not consistently produce water of sufficiently high quality on its own [

123]. This limitation often necessitates combining coagulation techniques with other treatment methods, such as membrane filtration, to achieve improved results. Such hybrid approaches have been widely implemented for turbidity removal, typically involving an initial coagulation (with flocculation) step followed by membrane filtration. For example, this combined technique was applied to remove protozoan parasites from surface water samples collected from the Pirapó River basin, which supplies water to Maringá city in Paraná, Brazil. Although turbidity reduction was not the primary focus of that study, it was observed as a secondary outcome that over 90% turbidity removal was achieved using a microfiltration membrane combined with a natural coagulant, Moringa [

123]. Another study applying this hybrid method to wood processing wastewater treatment, utilizing a nanofiltration membrane, reported an impressive turbidity removal efficiency of 99.7% [

124]. Similarly, water samples from a surface source in Yong Peng, Malaysia, treated with coagulation followed by ultrafiltration, showed turbidity removal efficiencies exceeding 99% [

125]. Furthermore, in the treatment of soap wastewater, a turbidity removal rate of 99.7% was achieved using ferric chloride (FeCl3) as the coagulant within a coagulation–flocculation and membrane filtration hybrid process [

126].

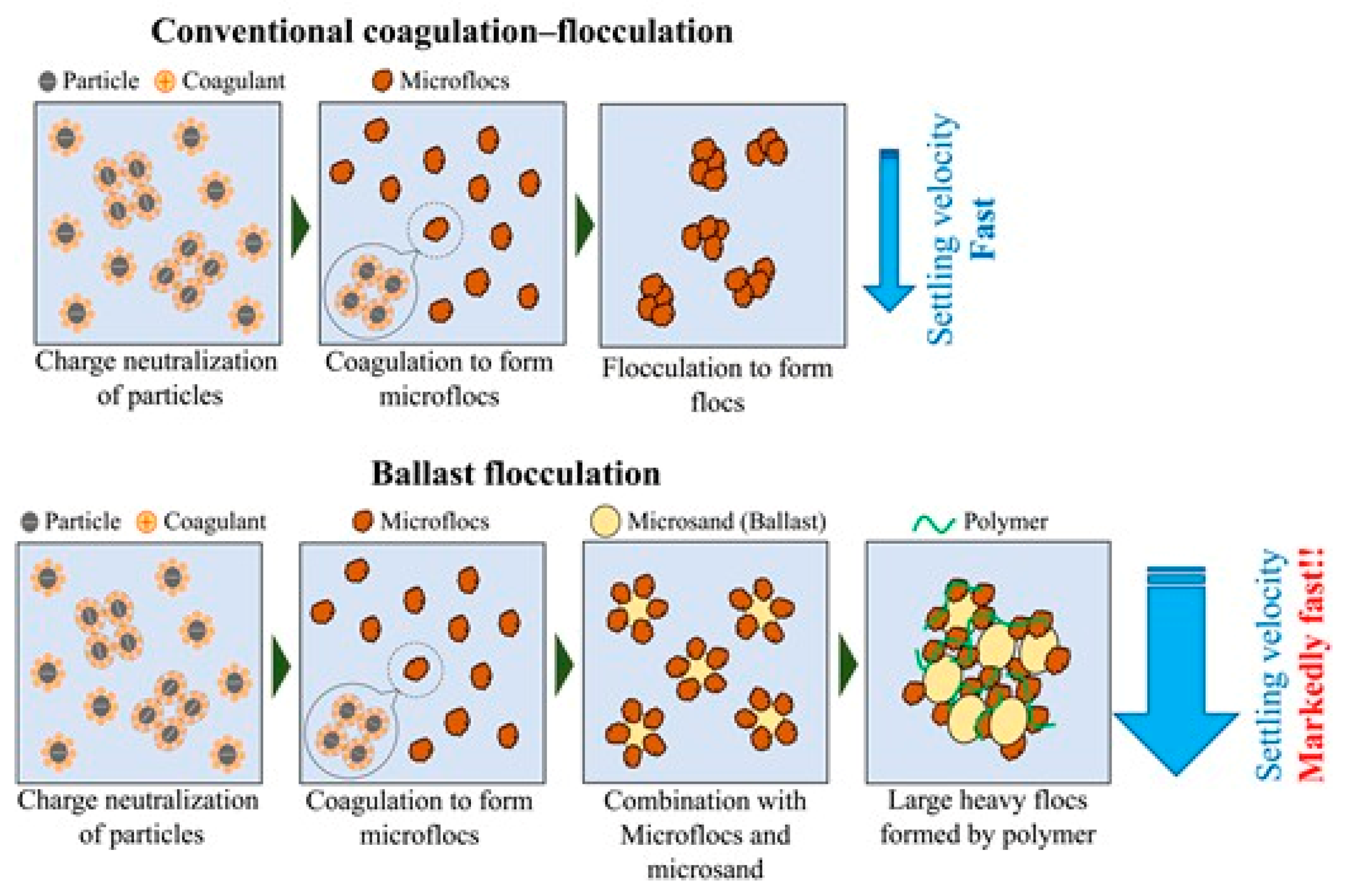

3.4.2. Coagulation with Ballasted Flocculation

Coagulation combined with ballasted flocculation is an effective and widely used method for the removal of turbidity from water. The primary distinction between conventional coagulation/flocculation and ballasted flocculation lies in the addition of a ballast material to the process [

127]. Common ballast materials employed include micro sand, iron oxide, and powdered activated carbon (PAC). The procedure generally involves the conventional coagulation and flocculation steps, wherein suspended particles are destabilized and aggregated into larger flocs. Subsequently, the ballast material is introduced to increase the density of these flocs, enhancing their settling velocity and facilitating more efficient sedimentation. The overall process, including a comparison with the standard coagulation/flocculation technique, is illustrated in

Figure 7 below.

Ballasted flocculation can effectively handle higher turbidity levels compared to conventional flocculation, as demonstrated by several case studies conducted on different types of turbid water sources. One such study utilized a natural coagulant (Aloe Vera) in combination with micro sand and powdered activated carbon (PAC) as ballasting agents to treat water samples with low (<12 NTU), medium (13–24 NTU), and high (25–35 NTU) turbidity levels. For the medium and high turbidity samples, the turbidity removal efficiencies achieved were 90.46% and 88.57%, respectively [

129]. Furthermore, another investigation aimed at optimizing conditions for high-speed solid–liquid separation through ballasted flocculation reported a turbidity removal efficiency of 99.7% using micro sand as the ballast material [

128].

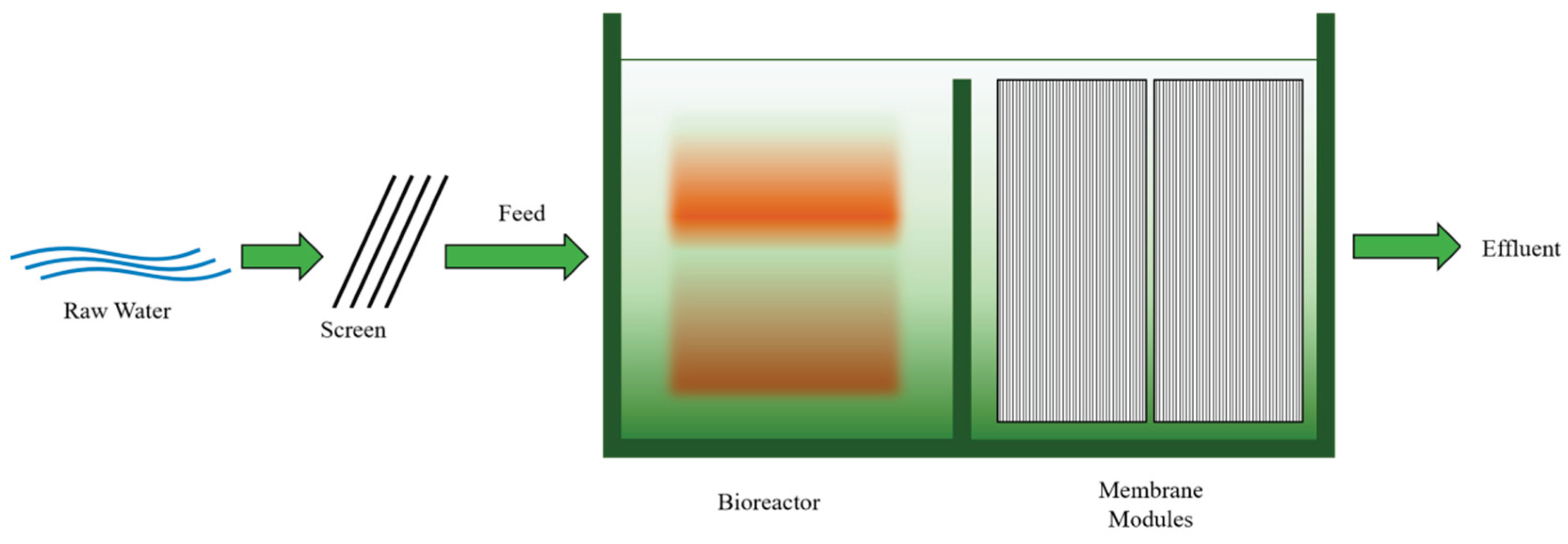

3.4.3. Coagulation with Membrane Bio Reactor technique

Coagulation followed by a membrane bioreactor (MBR) process is also recognized as an effective method for turbidity removal. Initially, suspended particles are destabilized through coagulation, allowing larger flocs to form during flocculation, which are subsequently removed. The resulting clarified effluent then serves as the feed for the MBR system. The MBR process integrates biological treatment, typically involving an activated sludge process, with membrane filtration. The membrane component, which can be either microfiltration or ultrafiltration [

130], functions as a physical barrier that separates treated water from biomass and any remaining particulate matter [

131].

Figure 8 presents a schematic diagram illustrating the MBR configuration.

Pre-treatment by coagulation removes larger particles that could otherwise cause fouling in membrane systems. Saeedika et al., (2025) [

132] investigated the application of this hybrid approach for the enhanced removal of chromium and nutrient pollutants from tannery wastewater. Turbidity was one of the key water quality parameters monitored during the study. Following coagulation, approximately 90% of turbidity was removed. Subsequently, the effluent was passed through the membrane bioreactor (MBR), where the water quality was further enhanced, achieving turbidity reductions of up to 99.8% [

133]. Another case study demonstrated the successful application of this technique for the reclamation of dairy wastewater. In this instance, a turbidity removal efficiency of 98.85% was achieved at an optimal coagulant dosage of 900 mg/L polyaluminium chloride (PACl) and a pH value of 7.5.

3.4.4. Ultrasound Assisted Coagulation

This method enhances turbidity removal by combining conventional coagulation with the application of ultrasound. The process leverages both the mechanical and chemical effects of ultrasound, such as cavitation, to improve the efficiency of coagulation and flocculation. Ultrasound generates cavitation bubbles that collapse violently, producing localized high temperatures and pressures [

134,

135]. This phenomenon aids in breaking down larger particles into smaller, more reactive ones, thereby effectively promoting particle collisions and enhancing the coagulation process. In other words, ultrasound increases the interaction between coagulants and suspended particles. Several studies have investigated this hybrid approach. For instance, Zhang et al., (2006) [

136] applied ultrasound-assisted coagulation to remove algae cells from water, observing significant turbidity reductions ranging from 85% to 93%, depending on the dose of the coagulant polyaluminum chloride (PAC) used. Another study examined the removal of the bacterium Microcystis aeruginosa and disinfection byproduct control following chlorination. Compared to conventional coagulation, ultrasound-assisted coagulation achieved an enhanced turbidity removal rate, increasing from 51% to between 87% and 96% [

137].

Based on these case studies of various hybrid technologies for turbidity removal, it can be concluded that such integrated approaches are applicable to a wide range of wastewater types. These hybrid techniques enhance turbidity removal through the synergistic interaction of the individual processes combined within each treatment system, resulting in significantly improved overall treatment efficiency compared to standalone methods. However, proper care must be taken, as the combination of certain techniques can be very costly; therefore, it is essential to select combinations that optimize efficiency while minimizing expenses.

4. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Emerging Technologies

nnovative approaches are increasingly explored by researchers and industry practitioners to identify more effective and sustainable treatment solutions. With the rapid emergence of diverse and complex pollutants contributing to turbidity, the development of cutting-edge technologies has become essential. These processes have the potential to enhance treatment efficiency, address a wide range of contaminants, and comply with stricter regulatory standards. As these technologies continue to evolve, they play a significant role in expanding the available options for turbidity removal from water.

Table 4 below summarizes the main advantages and disadvantages of each treatment process discussed in the previous sections.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Turbidity remains one of the most persistent and complex challenges in achieving safe and sustainable water supplies. Conventional methods, such as coagulation–flocculation, filtration, adsorption, and membrane technologies, form the backbone of current treatment systems but face limitations including sludge generation, fouling, high maintenance demands, and poor adaptability to extreme turbidity events. Emerging approaches, nanotechnology-based processes, electrocoagulation, advanced oxidation, and hybrid systems demonstrate higher efficiencies and broader applicability, yet their scalability, high operational costs, and limited real-world validation hinder widespread adoption.

The literature suggests that no single method can fully address turbidity in isolation. Future solutions should therefore integrate multiple approaches, blending proven conventional methods with innovative technologies to maximize overall effectiveness. Greater effort is needed to address the weaknesses of traditional techniques while ensuring treatment systems remain resilient to variability, including seasonal fluctuations and sudden turbidity spikes intensified by climate change. Sustainability and equity must also be prioritized: advanced methods should emphasize energy efficiency, affordability, and practicality in resource-limited regions where turbidity challenges are often most severe.

Future advances and developments in turbidity management will be driven by several critical research and innovation priorities. Developing smart, adaptive systems that pair artificial intelligence with real-time turbidity monitoring can optimize chemical dosing, energy use, and fouling control. Expanding the use of sustainable materials, such as bio-based coagulants, environmentally benign nanoparticles, and recyclable adsorbents, represents another critical direction. In rural and climate-vulnerable areas, mobile, low-cost, and renewable-powered solutions should be advanced to provide reliable protection against turbidity. Importantly, more pilot-scale and field studies are needed to validate the performance, safety, and scalability of emerging methods.

In conclusion, turbidity control is entering a new phase defined by integration, intelligence, and sustainability. Through the application of hybrid technologies that merge conventional and advanced methods within adaptive, context-sensitive frameworks, future treatment systems can provide resilient, cost-effective, and equitable access to clean water, addressing the mounting pressures of environmental change and population growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; methodology (literature search and screening), S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; ; validation, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera.; writing—review and editing, S.M.S.N Sumanasekera., J.R. Rajapakse.; visualization (figures/tables), S.M.S.N Sumanasekera.; supervision, J.R. Rajapakse.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used “Grammarly” for the purpose of improving the language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NTU |

Nephelometric Turbidity Units |

| UV |

Ultra Violet |

| CSG |

Coal Seam Gas |

| PMF |

Pebble Matrix Filtration |

| RO |

Reverse Osmosis |

| NF |

Nano Filtration |

| UF |

Ultra Filtration |

| MF |

Micro Filtration |

| CNT |

Carbon Nano Tubes |

| AOP |

Advanced Oxidation Process |

| EC |

Electro Coagulation |

References

- Mayur Bhadarka, Vaghela, D.T., Bamaniya Pinak Kamleshbhai, Hardik Sikotariya and Verma, P. (2024). Water Pollution: Impacts on Environment. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383021412_Water_Pollution_Impacts_on_Environment.

- USGS (2018). Turbidity and Water | U.S. Geological Survey. [online] USGS. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/turbidity-and-water [Accessed : 10/06/2025].

- Fondriest Environmental, Inc. (2014). Turbidity, Total Suspended Solids & Water Clarity - Environmental Measurement Systems. [online] Environmental Measurement Systems. Available at: https://www.fondriest.com/environmental-measurements/parameters/water-quality/turbidity-total-suspended-solids-water-clarity/ [Accessed : 10/06/2025].

- AQUALABO (2024). Understanding the turbidity of water: causes, measurement and solutions - Aqualabo. [online] Aqualabo. Available at: https://www.aqualabo.fr/en/understanding-the-turbidity-of-water-causes-measurement-and-solutions/ [Accessed : 14/06/2025].

- Grobbelaar, J.U. (2009). Turbidity. [online] ScienceDirect. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123706263000752.

- YSI (2024). Turbidity measurement and monitoring in water quality analysis | YSI. [online] www.ysi.com. Available at: https://www.ysi.com/parameters/turbidity [Accessed : 14/06/2025].

- Soros, A., Amburgey, J.E., Stauber, C.E., Sobsey, M.D. and Casanova, L.M. (2019). Turbidity reduction in drinking water by coagulation-flocculation with hitosan polymers. Journal of Water and Health, [online] 17(2), pp.204–218. [CrossRef]

- Olszak, N. (2022). How to Treat Turbidity in Water | Complete Water Solutions. [online] COMPLETE WATER SOLUTIONS. Available at: https://complete-water.com/resources/how-to-treat-turbidity-in-water [Accessed : 14/06/2025].

- Lee, C.S., Robinson, J. and Chong, M.F. (2014). A review on application of flocculants in wastewater treatment. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 92(6), pp.489–508. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-C., Chua, S.-C. and Chong, F.-K. (2020). Coagulation-Flocculation Technology in Water and Wastewater Treatment. Handbook of Research on Resource Management for Pollution and Waste Treatment, pp.432–457. [CrossRef]

- Iwuozor, K.O. (2019). Prospects and Challenges of Using Coagulation-Flocculation Method in the Treatment of Effluents. Advanced Journal of Chemistry-Section a, 2(2), pp.105–127. [CrossRef]

- Lmipumps.com. (2018). Coagulation and Flocculation in Water Treatment. [online] Available at: https://www.lmipumps.com/en/technologies/coagulation-and-flocculation-in-water-treatment/ [Accessed : 14/06/2025].

- Ashraf, S.N., Rajapakse, J., Millar, G. and Dawes, L., 2016. Performance analysis of chemical and natural coagulants for turbidity removal of river water in coastal areas of Bangladesh. In: Kabir, S.M.Z. and Hasan, M.Z., eds. Proceedings of the 1st AISD International Multidisciplinary Conference: International Multidisciplinary Conference on Sustainable Development (IMCSD) 2016. Australia: Australian Institute for Sustainable Development (AISD), pp.172–182. Available at: Fhttps://scholar.google.com.au/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=UCssR4oAAAAJ&citation_for_view=UCssR4oAAAAJ:9yKSN-GCB0IC.

- Nishat Ashraf, S., Rajapakse, J., Dawes, L.A. and Millar, G.J. (2018). Coagulants for removal of turbidity and dissolved species from coal seam gas associated water. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 26, pp.187–199. [CrossRef]

- forestier, jean-pierre (2024). How to Eliminate Turbidity in Well Water for Clear and Healthy Water? [online] Diproclean.com. Available at: https://www.diproclean.com/en/solutions-impurities-water-house-xsl-537_538_545.html [Accessed : 15/06/2025].

- Www.htt.io. (2024). Htt.io. [online] Available at: https://www.htt.io/learning-center/understanding-sedimentation-water-treatment [Accessed : 15/06/2025].

- BOQU (2024). How to Reduce Turbidity in Water: Solutions and Technologies. [online] Boquinstrument.com. Available at: https://www.boquinstrument.com/a-how-to-reduce-turbidity-in-water-solutions-and-technologies.html [Accessed : 15/06/2025].

- www.etch2o.com. (2023). What is Sedimentation in Wastewater Treatment? - Etch2o. [online] Available at: https://www.etch2o.com/what-is-sedimentation-in-wastewater-treatment/ [Accessed : 15/06/2025].

- Ephrem Guchi (2015). Review on Slow Sand Filtration in Removing Microbial Contamination and Particles from Drinking Water. American Journal of Food and Nutrition, [online] 3(2), pp.47–55. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275097978_Review_on_Slow_Sand_Filtration_in_Removing_Microbial_Contamination_and_Particles_from_Drinking_Water_Ephrem_Guchi_1.

- T, M. (2017). Rapid vs slow filtration. [online] Biosand filter. Available at: https://biosandfilter.org/biosand-filter/rapid-vs-slow-filtration/ [Accessed : 16/06/2025].

- U.S. EPA Area-Wide Optimization Program (AWOP) Water Quality Goals and Operational Criteria for Optimization of Slow Sand Filtration. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/water-quality-goals-and-slow-sand-filtration.pdf [Accessed : 16/06/2025].

- Wegelin, M. (1996). Surface Water Treatment by Roughing Filters: A Design, Construction and Operation Manual, pp.v-3.

- Slow Sand Filtration | SSWM - Find tools for sustainable sanitation and water management! Sswm.info. Available at: https://sswm.info/sswm-university-course/module-6-disaster-situations-planning-and-preparedness/further-resources-0/slow-sand-filtration [Accessed : 16/06/2025].

- Tamakhu, G. and Amatya, I.M. (2021). Turbidity removal by rapid sand filter using anthracite coal as capping media. Journal of Innovations in Engineering Education, 4(1), pp.69–73. [CrossRef]

- Adel, K., M. Negm, M. Abdelrazik and E. Wahb (2014). The Use of Roughing Filters in Water Purification. Scientific Journal of October 6 University, 2(1), pp.50–58. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333683287_The_Use_of_Roughing_Filters_in_Water_Purification.

- Nkwonta, O.I., Olufayo, O.A., Ochieng, G.M., Adeyemo, J.A. and Otieno, F.O.A. (2010). Turbidity Removal: Gravel and Charcoal as Roughing Filtration Media. SSRN Electronic Journal. Availabel at: . [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, J.P. and Fenner, R.A. (2011). Evaluation of Alternative Media for Pebble Matrix Filtration Using Clay Balls and Recycled Crushed Glass. Journal of Environmental Engineering, 137(6), pp.517–524. [CrossRef]

- Pure Aqua. Inc. (2022). Turbidity In Water Treatment. [online] Available at: https://pureaqua.com/turbidity-in-water-treatment/ [Accessed : 16/06/2025].

- Akhtar, M.S., Ali, S. and Zaman, W. (2024). Innovative Adsorbents for Pollutant Removal: Exploring the Latest Research and Applications. Molecules, 29(18), p.4317. [CrossRef]