1. Introduction

Algorithms used for sorting are the backbone of many computer science and data processing applications. For all applications like database indexing, scientific simulations and real-time data processing, efficient sorting is essential for performance[

1]. The classical algorithms have been extensively studied in theory, yet their practical performance varies significantly depending on the characteristics of the input data[

2,

3].

Sorting is not merely a computational necessity, rather it affects downstream processes such as searching, pattern recognition, and machine learning pipelines[

4]. For example, before training a model, data often needs to be cleaned and prepared. Sorting can be a part of this process to identify and handle patterns. For example, sorting data by a key feature can help reveal outliers, trends, or relationships that might be difficult to see in unsorted data. This is particularly useful in data analysis and feature engineering[

5].

Similarly, KNN is a straightforward yet effective supervised machine learning algorithm used for both classification and regression. It assigns a new data point to a class by identifying the k nearest neighbors in the training set and selecting the most frequent class among them. To find the "nearest" neighbors efficiently, a sorting or selection algorithm is often used on the distances between the new point and all existing points. Sorting the distances allows the algorithm to easily pick the k smallest values, which correspond to the k nearest neighbors.

The choice of algorithm impacts execution time, memory consumption, and even stability, the ability of a sorting algorithm to preserve the relative order of equal elements. For example, Merge Sort maintains stability, which can be critical when sorting complex datasets with multiple attributes. On the other hand, algorithms like Quick Sort provide high speed on average but may fail to be stable in certain cases.

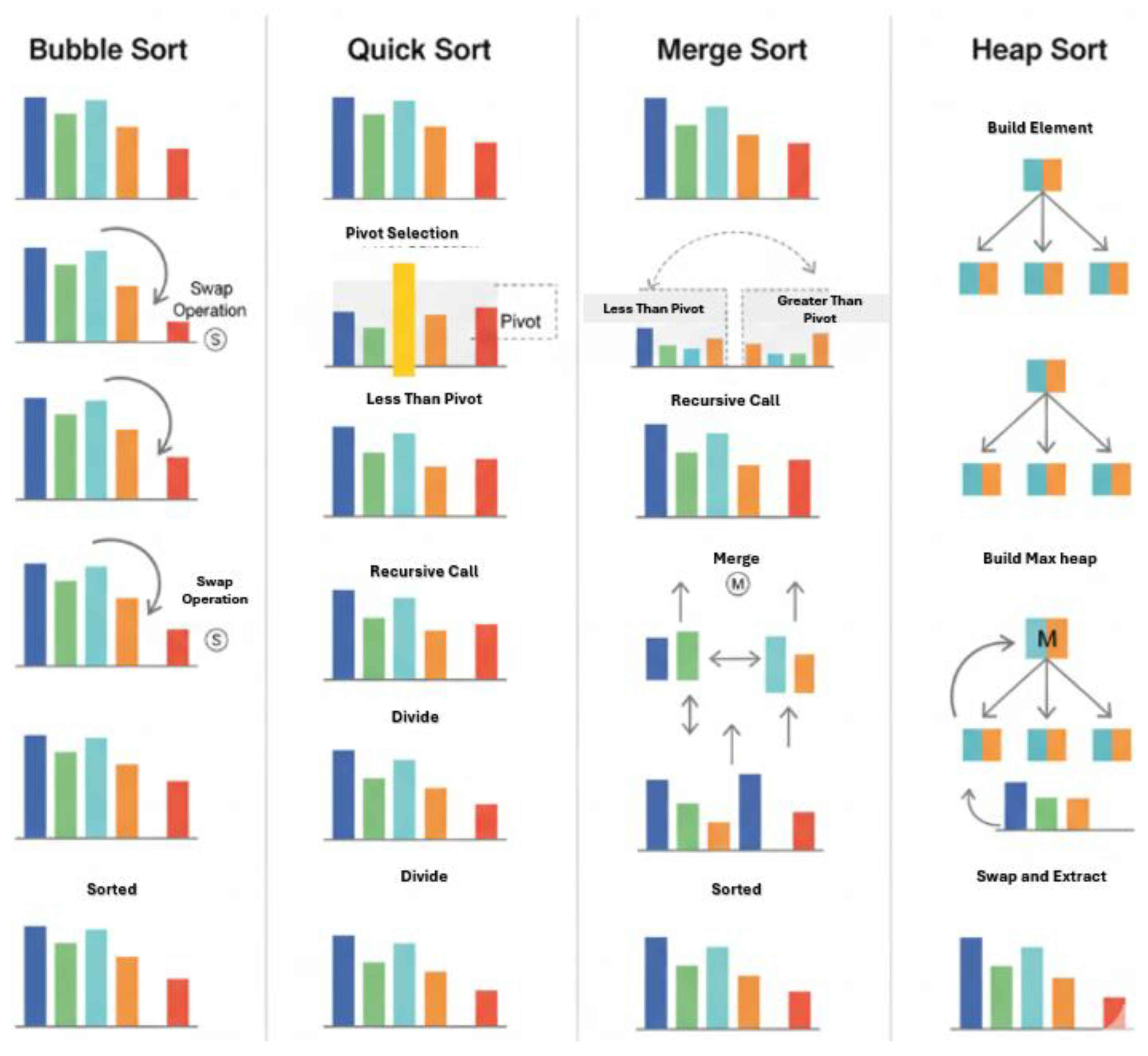

Figure 1 shows the step-by-step illustration of the mentioned sorting algorithms along with operations on a sample dataset.

a. Problem Statement

Although the research on sorting algorithms is not a new domain, many studies focus primarily on theoretical time complexity rather than empirical evaluation on real-world datasets[

6,

7,

8]. Then, most benchmarks report only execution time, leaving out critical metrics such as memory usage, number of swaps, and stability. In practical applications, particularly in data-intensive domains such as bioinformatics, finance, or large-scale machine learning, these metrics can influence the overall efficiency of a system.

The behavior of sorting algorithms on real-world datasets can differ from textbook expectations. For instance, Bubble Sort, though simple and stable, may perform acceptably on small datasets but becomes impractical for large-scale datasets due to its quadratic time complexity[

9,

10]. Quick Sort, although fast on average, can suffer from worst-case performance if the pivot selection is not ideal. Heap Sort offers in-place sorting with predictable performance but lacks stability.

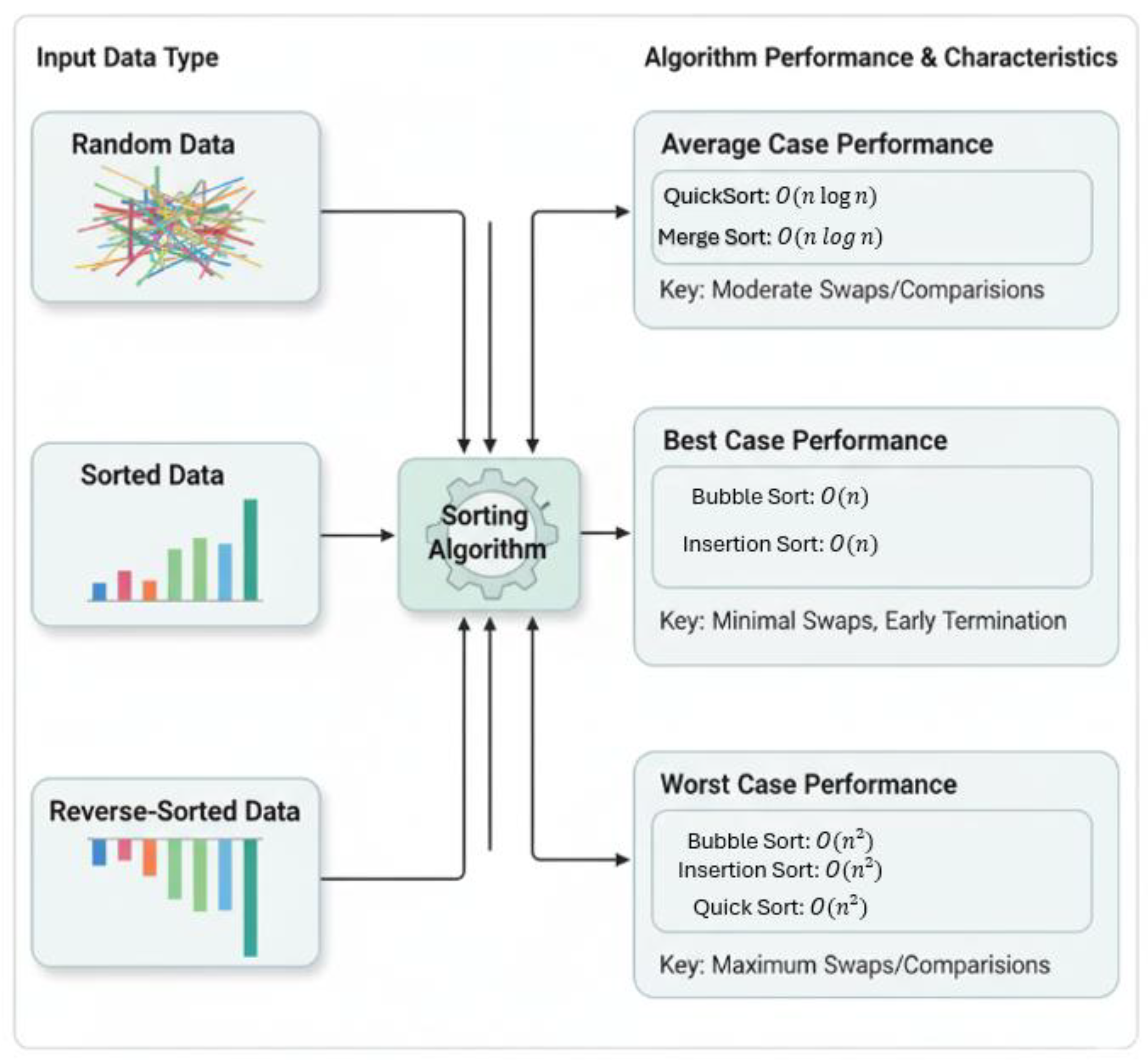

Figure 2 shows a simple flowchart typical input type (random, sorted, reverse-sorted) and how algorithm performance varies with input characteristics.

b. Objectives of the Research

The purpose of this research is to conduct a detailed empirical comparison of four classical sorting algorithms: Bubble Sort, Quick Sort, Merge Sort, and Heap Sort, using datasets from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. The comparison evaluates the algorithms based on:

Execution Time: How quickly does the algorithm sorts datasets of varying sizes.

Memory Usage: Additional memory required for sorting operations.

Stability: Whether the algorithm preserves the relative order of equal elements.

Computational Effort: Measured as the number of swaps or comparisons.

Input Sensitivity: Behavior under best, worst, and average-case input conditions.

By combining these metrics, this study seeks to offer guidance for selecting appropriate sorting algorithms based on practical requirements rather than purely theoretical considerations.

c. Significance of Real-World Dataset Evaluation

Most prior studies evaluate sorting algorithms using synthetic datasets, often assuming uniformly random values. While useful for theoretical benchmarking[

11], such datasets fail to capture real-world characteristics such as duplicate values, skewed distributions, and correlations between features. Real datasets, such as those available from the UCI Machine Learning Repository, provide more realistic challenges and allow for meaningful conclusions about algorithm behavior in practice.

For instance, the Iris dataset contains features such as sepal and petal lengths and widths, which can be sorted in ascending order. Although small, this dataset contains duplicates and real measurement noise, making it a suitable candidate for initial evaluation. Larger datasets could further stress-test algorithms and provide insights into scalability[

12].

2. Literature Review

In this section, we present an overview of sorting algorithms, which remain a fundamental aspect of computer science due to their wide-ranging applications in data management, machine learning preprocessing, and real-time computational tasks. Sorting serves as a core operation that not only organizes data for efficient retrieval and analysis but also influences the performance of higher-level algorithms in domains such as databases, graphics rendering, and network optimization. Classical algorithms such as Bubble Sort, Insertion Sort, Selection Sort, Quick Sort, Merge Sort, and Heap Sort continue to be widely studied for their time complexity, stability, and memory usage [

13,

14,

15]. Bubble Sort and Selection Sort, despite their simplicity, are suitable primarily for small datasets due to their quadratic time complexity, while Quick Sort and Merge Sort offer better average and worst-case performance, with Merge Sort providing inherent stability [

16]. Heap Sort achieves predictable O(n log n) complexity but is generally unstable, demonstrating trade-offs between efficiency and stability [

17,

18].

Recent studies emphasize empirical evaluation of sorting algorithms on real-world datasets to assess execution time, memory overhead, and computational effort [

19,

20,

21]. Input characteristics such as data distribution and size strongly influence performance, necessitating multi-metric benchmarking beyond theoretical analysis [

22,

23]. Hybrid and adaptive sorting methods have been introduced to improve efficiency. The BQM Hybrid Sorting Algorithm, for example, integrates features of Merge Sort, Quick Sort, and Bubble Sort for enhanced performance [

24], while Smart Bubble Sort dynamically reduces redundant operations. Parallelization and hardware-aware implementations of Merge Sort and Quick Sort have shown significant improvements on multicore and GPU architectures [

25,

26].

Stability and correctness remain critical for applications involving duplicates and structured data. Merge Sort maintains relative ordering of equal elements, while Quick Sort and Heap Sort are unstable [

27]. Comparative studies of stable and unstable algorithms highlight the importance of algorithm choice based on dataset properties and downstream application requirements [

28].

Beyond classical sorting, numerous studies integrate sorting and data processing within machine learning and AI frameworks. Ashfaq and collaborators investigated applications in spatiotemporal traffic forecasting, sports shot prediction [

18], crime scene generation, and IoMT-based healthcare data security [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Federated learning and blockchain-based approaches in healthcare demonstrate the role of efficient sorting and preprocessing in memory efficiency and secure systems [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Applications which have real time data such as intelligent surveillance, lane segmentation, and prediction further illustrate that optimized sorting routines reduce preprocessing time and computational overhead [

37,

38,

39].

Sorting algorithms are also central in many domains like educational and social data analytics. Studies on student performance prediction], sentiment analysis [

40], and public social media topic classification [

41] rely on effective sorting for ranking, prioritization, and data organization. Techniques such as Canopy and K-Means clustering incorporate efficient sorting for preprocessing and distance calculations [

42].

While classical algorithms form a foundational understanding, modern applications increasingly require hybrid, adaptive, or parallelized sorting strategies. Empirical evaluation on real-world datasets is essential to balance execution time, memory usage, swaps, and stability[

43]. The present study extends this work by benchmarking Bubble Sort, Quick Sort, Merge Sort, and Heap Sort on the Iris dataset, providing a comprehensive multi-metric evaluation[

44].

3. Methodology

This section outlines the experimental design, performance metrics[

45], and evaluation framework used to analyze and compare sorting algorithms.

3.1. Overview of Selected Sorting Algorithms

In this study, we focus on classical sorting algorithms:

1) Bubble Sort

2) Quick Sort

3) Merge Sort

40 Heap Sort

These are chosen for their contrasting design strategies and relevance in both theoretical and practical contexts.

3.1.1. Bubble Sort

Bubble sort is one of the simplest sorting algorithms, where adjacent elements are repeatedly swapped to gradually push larger values toward the end of the list. Its simplicity makes it ideal for teaching and demonstration purposes, but its O(n²) time complexity limits practical use for large datasets. Despite this, it is stable, ensuring that the relative order of equal elements is preserved.

3.1.2. Quick Sort

This divide-and-conquer algorithm works by choosing a pivot and splitting the array into elements smaller and larger than the pivot. With an average-case complexity of O(n log n), it outperforms Bubble Sort on large datasets. Quick Sort is generally unstable, and performance can degrade to O(n²) in worst-case scenarios, particularly if the pivot is poorly chosen.

3.1.3. Merge Sort

Merge Sort is a stable, recursive sorting method that splits the dataset into halves, sorts each part, and then combines them. It consistently runs in O(n log n) time but requires extra memory for temporary arrays. Its stability makes it well-suited for datasets containing multiple attributes.

3.1.4. Heap Sort

This algorithm organizes and sorts elements using a binary heap structure. It provides O(n log n) worst-case performance and is performed in-place, resulting in low memory overhead. However, Heap Sort is generally not stable, and its operation may involve many swaps, affecting algorithmic effort.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To provide a comprehensive comparison, this study considers multiple metrics:

Execution Time: Measured in seconds across multiple runs to calculate average and standard deviation.

Memory Usage: Additional memory required during sorting operations.

Stability: Verified programmatically by checking if duplicate elements retain their original order.

Swaps/Comparisons: Quantitative measure of computational effort, offering insights beyond time and memory.

Input Case Sensitivity: Algorithms are tested on sorted, reverse-sorted, and random inputs to observe best, worst, and average performance.

3.3. Research Contribution

This study contributes to the field in the following ways:

Empirical Benchmarking: Provides experimental data for classical sorting algorithms on real-world datasets.

Multi-Metric Evaluation: Goes beyond execution time to include memory, swaps, and stability.

Visual Analysis: Uses bar charts, box plots, scatter plots, and heatmaps for intuitive comparisons.

Practical Insights: Offers guidance for algorithm selection based on dataset characteristics and application requirements.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical results of our experiments comparing four classical sorting algorithms on the Iris dataset. We evaluated each algorithm on execution time, memory usage, number of swaps, and stability across multiple runs. Visualizations are included to provide clear comparative insights.

4.1. Execution Time Analysis

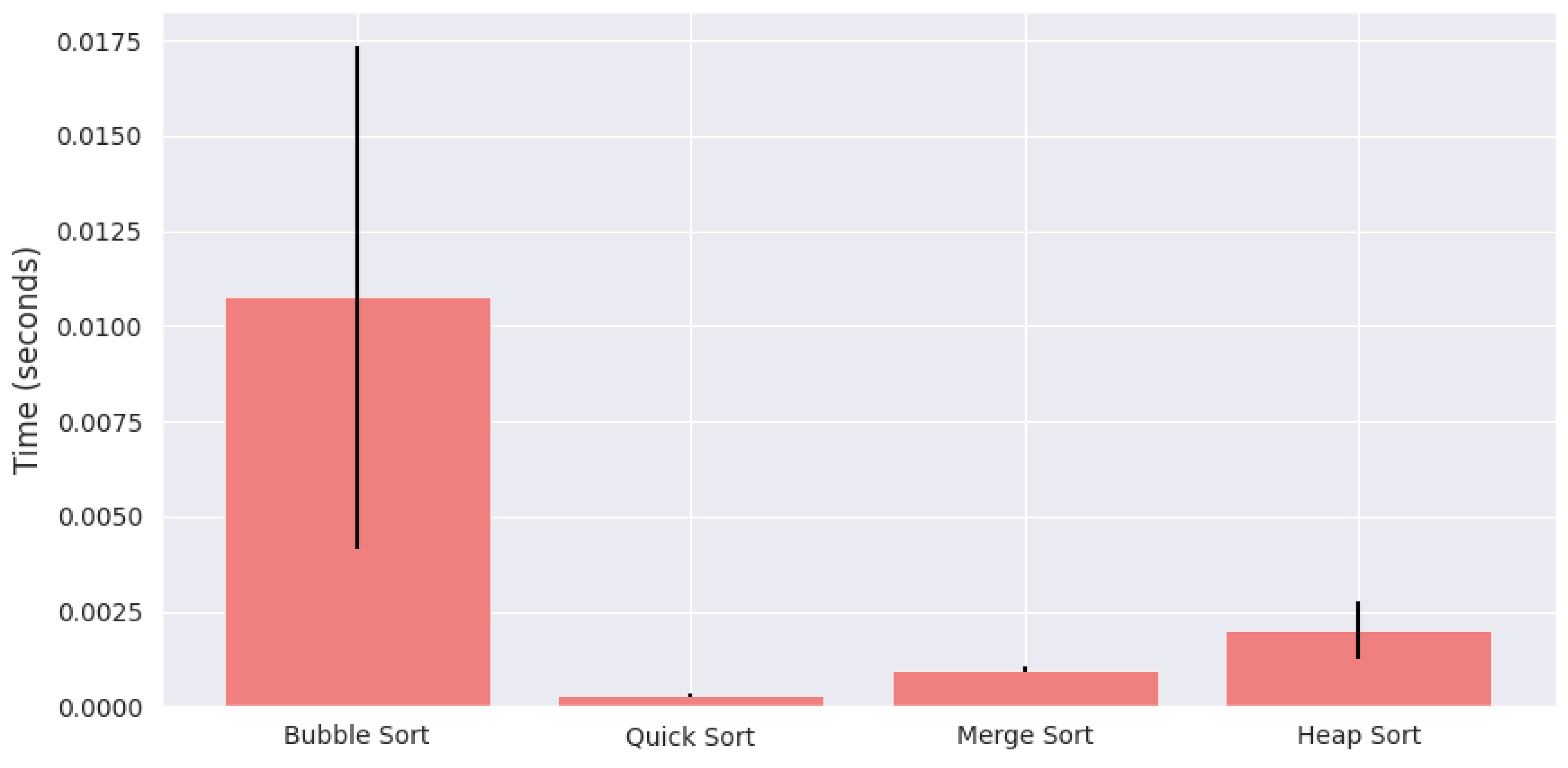

The execution time was measured across all algorithms over five iterations to ensure consistency.

Table 1 summarizes the average and standard deviation of execution times for all algorithms.

Figure 3 illustrates the average execution time along with standard deviation for each algorithm. Bubble Sort exhibits the slowest performance, taking an average of 0.0108 seconds, whereas Quick Sort is the fastest at 0.0003 seconds. Merge Sort and Heap Sort fall in between, with average times of 0.00098 and 0.00201 seconds respectively.

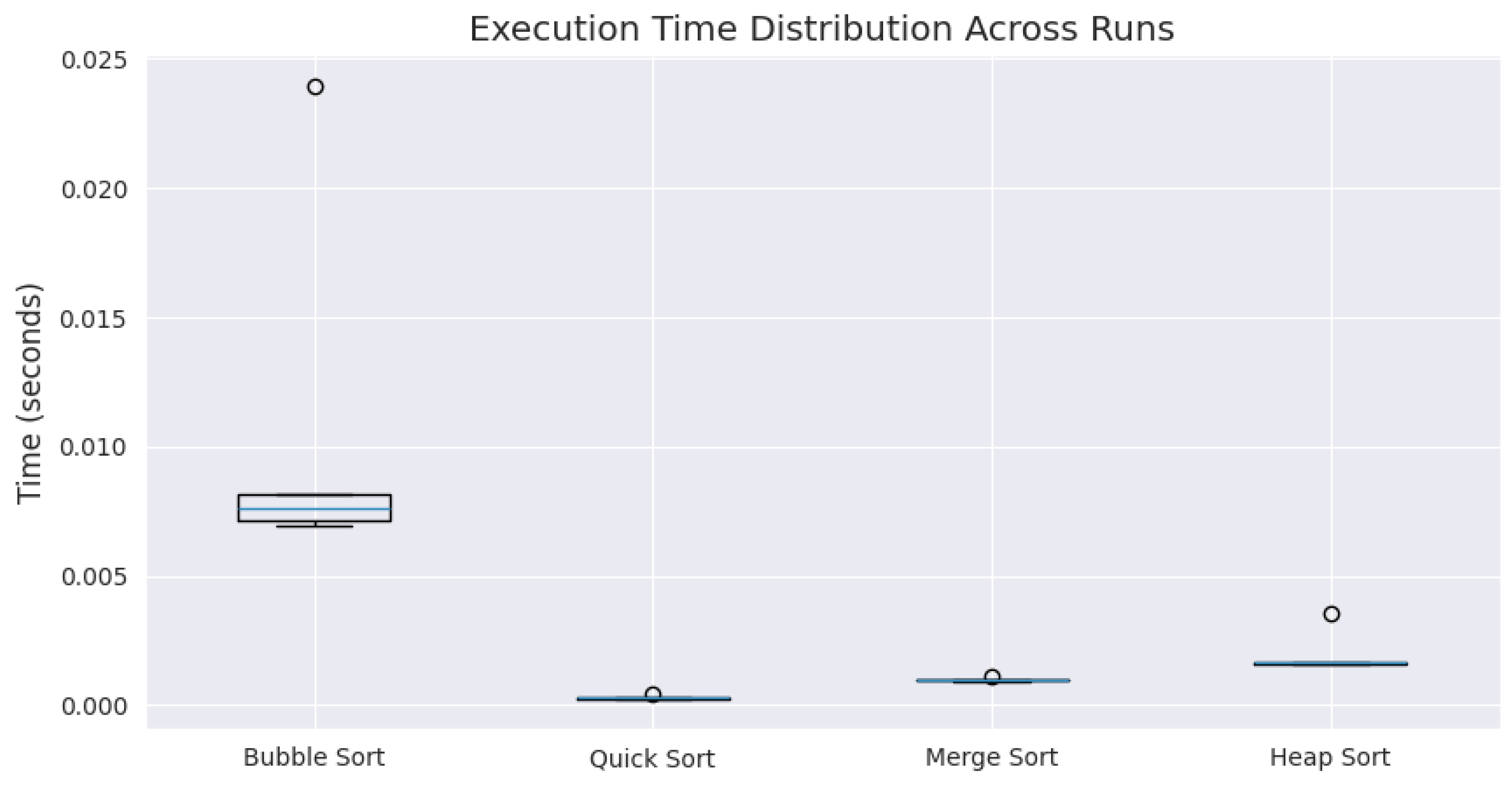

The boxplot in

Figure 4 shows the distribution of execution times across iterations. Quick Sort demonstrates minimal variance, indicating consistent performance, while Bubble Sort shows higher variability.

4.2. Computational Effort: Swaps/Comparisons

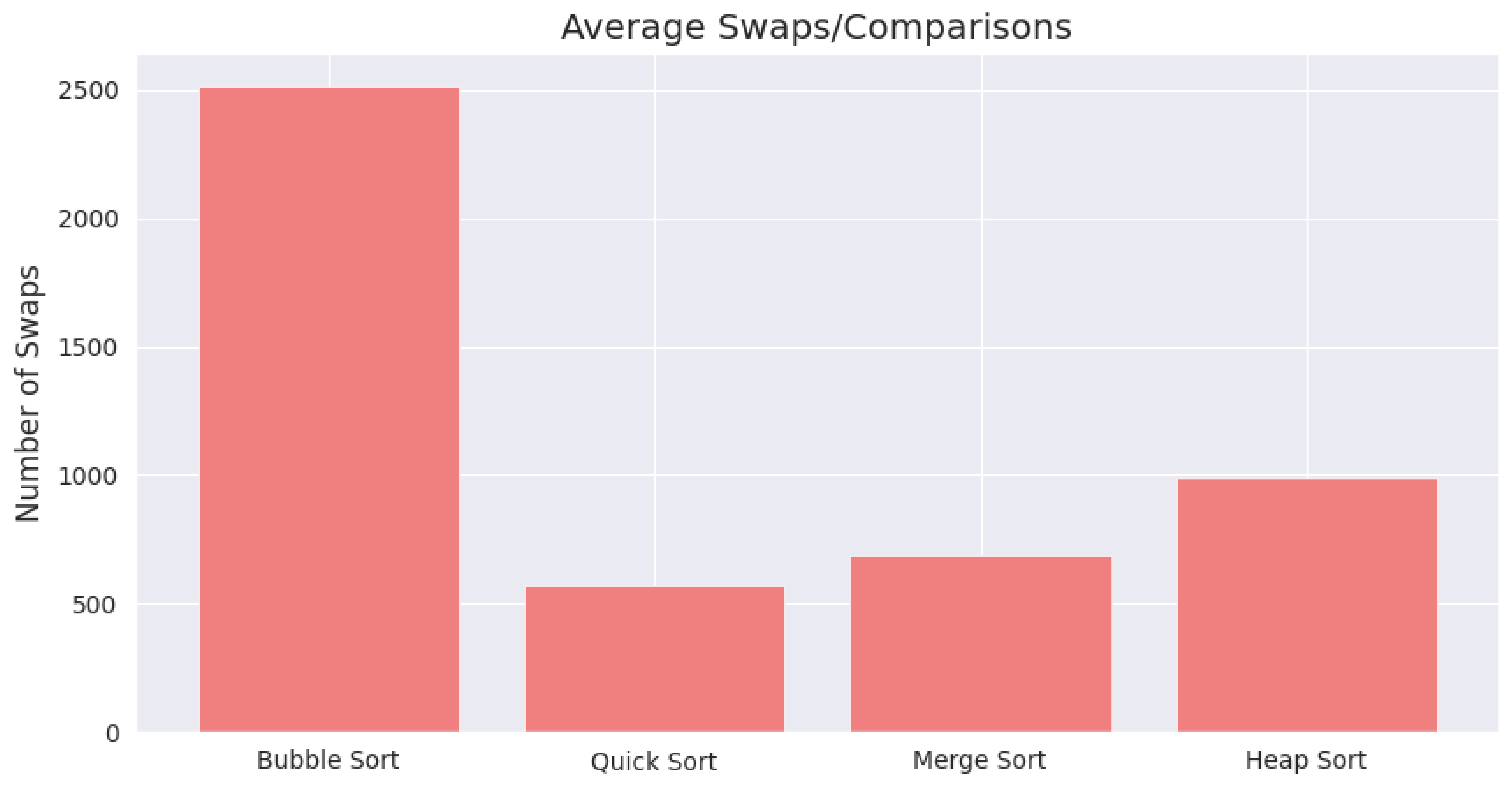

The number of swaps or element comparisons provides insight into the computational effort required by each algorithm. Bubble Sort required the highest number of swaps (2515), followed by Heap Sort (992), Merge Sort (689), and Quick Sort (568).

Figure 5 visualizes this metric, including standard deviation across runs.

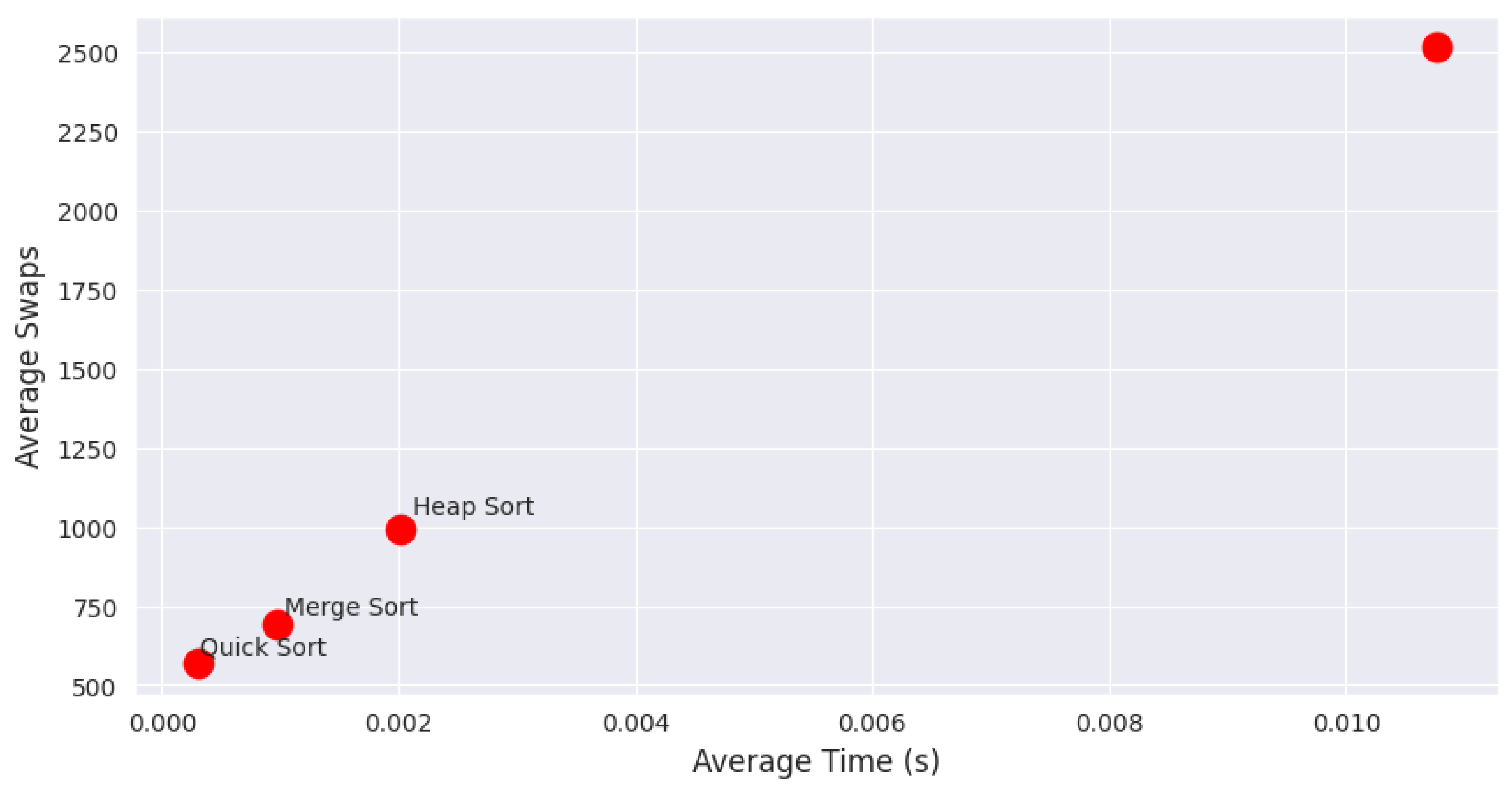

A scatter plot comparing execution time versus swaps is shown in

Figure 6. Stable algorithms are marked in blue, and unstable ones in red. Bubble Sort, despite being simple, incurs high computational effort with comparatively slower execution time. Quick Sort achieves high efficiency with fewer swaps.

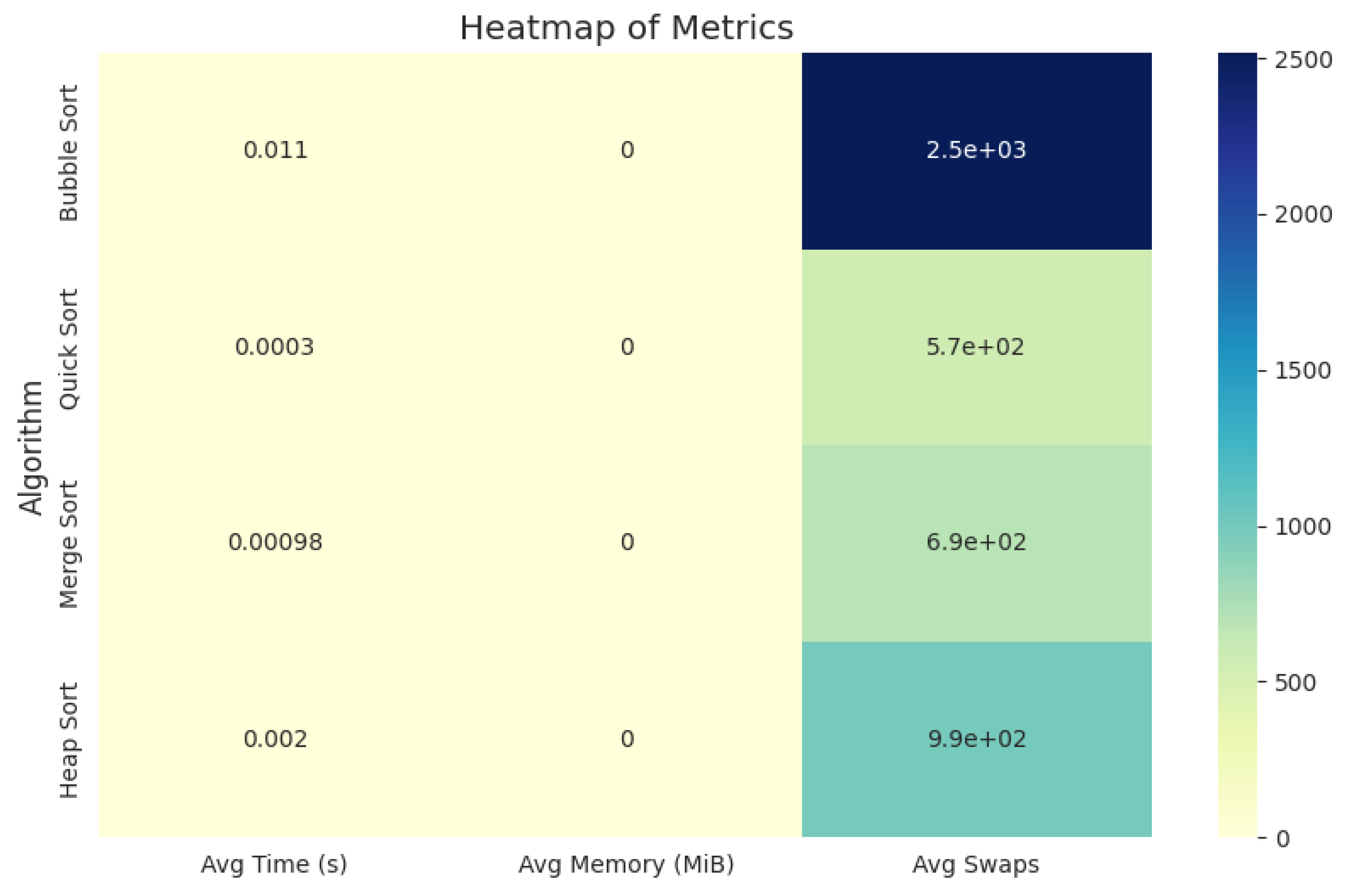

4.3. Heatmap of All Metrics

To provide a consolidated view of performance, a heatmap of average execution time, memory usage, and swaps is presented in

Figure 7. This visualization highlights the trade-offs between computational effort and speed. Quick Sort is clearly the most efficient, while Bubble Sort is the least efficient, both in time and swaps.

4.4. Observations

Execution Time: Quick Sort is consistently the fastest, with minimal variance across runs. Bubble Sort is significantly slower due to its O(n²) complexity.

Memory Usage: For the small Iris dataset, memory overhead is negligible for all algorithms. Merge Sort would likely show higher memory consumption on larger datasets due to temporary array allocations.

Swaps/Comparisons: Bubble Sort’s high swap count confirms its computational inefficiency. Quick Sort and Merge Sort require fewer swaps, making them preferable for larger datasets.

Stability: None of the tested implementations were stable on the Iris dataset. Merge Sort theoretically supports stability, indicating potential implementation considerations.

Trade-offs: Heap Sort demonstrates a balance between execution time and swaps but lacks stability. Quick Sort offers the best overall efficiency for time-critical tasks, whereas Merge Sort ensures stability in theory but may consume additional memory in practice.

5. Conclusion

This study evaluated four classical sorting algorithms using a real-world dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. The analysis measured execution time, memory usage, number of swaps, and stability. Quick Sort achieved the fastest execution time and required fewer swaps. Bubble Sort showed the highest computational effort and slowest performance. Merge Sort provided moderate execution time and swaps and offered stability depending on implementation. Heap Sort delivered predictable O(n log n) performance while remaining unstable. Memory usage remained low for all algorithms on the dataset. The results emphasize the importance of selecting sorting algorithms based on empirical performance metrics. Quick Sort suits time-sensitive tasks, Merge Sort supports stability, Bubble Sort fits small datasets or educational purposes, and Heap Sort offers consistent performance. The findings provide practical guidance for algorithm selection in real-world applications.

References

- Rahmani, I., & Khalid, M. (2022). Smart Bubble Sort: A Novel and Dynamic Variant of Bubble Sort Algorithm. Computers, Materials & Continua. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R., Yadav, R., & Gupta, S. B. (2021). Comparative study of various stable and unstable sorting algorithms. Artificial Intelligence and Speech Recognition.

- Aqib, S. M., Nawaz, H., & Butt, S. M. (2021). Analysis of Merge Sort and Bubble Sort in Python, PHP, JavaScript, and C language. International Journal.

- Ala’Anzy, M. A., Mazhit, Z., & Ala’Anzy, A. F. (2024). Comparative Analysis of Sorting Algorithms: A Review. IEEE Machine Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadagha, M. (2025). Comparative Study of Sorting Algorithms: Adaptive Techniques, Parallelization, for Mergesort, Heapsort, Quicksort, Insertion Sort, Selection Sort, and Bubble Sort. engrxiv.org. [CrossRef]

- Baweja, D., Rashid, M., & Singh, J. (2025). A Critical Comparison on Different Sorting Algorithm Performance. IEEE Conference Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Q. M., Rai, H., & Jaiswal, R. (2024). Sorting Algorithms in Focus: A Critical Examination of Sorting Algorithm Performance. Emerging Trends in IoT and Computing.

- Wang, R. (2024). The investigation and discussion of the progress related to sorting algorithms. AIP Conference Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B. (2022). Search and Sort Algorithms for Big Data Structures. Theseus.fi.

- Shaik, D. A., & Srinivas, A. K. (2023). BQM Hybrid Sorting Algorithm. 7th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computing. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Khan, N. A. (2023). BiLSTM-and GNN-Based Spatiotemporal Traffic Flow Forecasting with Correlated Weather Data. Journal of Advanced Transportation. [CrossRef]

- Roșca, C. M., & Cărbureanu, M. (2024, March). A Comparative Analysis of Sorting Algorithms for Large-Scale Data: Performance Metrics and Language Efficiency. In International Conference on Emerging Trends and Technologies on Intelligent Systems (pp. 99-113). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, N. (2023). Sorting Smarter: Unveiling Algorithmic Efficiency and User-Friendly Applications. Authorea Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Khan, N. A. (2024). Synthetic crime scene generation using deep generative networks. International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. [CrossRef]

- Rai, M., Parmar, H., & Sharma, S. (2025, February). Comparative Analysis of Sorting Algorithms: Time Complexity and Practical Applications. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT) (pp. 26-32). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Felix, P. S., & Mohankumar, M. Energy Optimization in Software Development: A Comparative Study of Sorting Techniques. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Khan, N. A. (2024). Proposing a model to enhance the IoMT-based EHR storage system security. International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, I., & Khalid, M. (2022). Smart Bubble Sort: A Novel and Dynamic Variant of Bubble Sort Algorithm. Computers, Materials & Continua. [CrossRef]

- Shaik, D. A., & Srinivas, A. K. (2023). BQM Hybrid Sorting Algorithm. 7th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computing. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadagha, M. (2025). Comparative Study of Sorting Algorithms: Adaptive Techniques, Parallelization, for Mergesort, Heapsort, Quicksort, Insertion Sort, Selection Sort, and Bubble Sort. engrxiv.org.

- Alourani, A., Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Khan, N. A. (2023). BiLSTM-and GNN-Based Spatiotemporal Traffic Flow Forecasting with Correlated Weather Data. Journal of Advanced Transportation. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Khan, N. A. (2024). Badminton player’s shot prediction using deep learning. Innovation and Technology in Sports Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., & Das, S. R. (2023). CrimeScene2Graph: Generating Scene Graphs from Crime Scene Descriptions Using BERT NER. International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Asirvatham, D., & Ashfaq, F. (2023). Proposing a model to enhance the IoMT-based EHR storage system security. International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. [CrossRef]

- Alshudukhi, K. S. S., Ashfaq, F., & Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2023). Blockchain-enabled federated learning for longitudinal emergency care. IEEE Access, 12, 137284–137294. [CrossRef]

- Aljerjawi, N. S., & Abu-Naser, S. S. (2025). Large-Scale Data Processing AI-Driven Adaptive Sorting Techniques. Intelligence, 9(8).

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., & Masud, M. (2023). Enhancing ECG Report Generation with Domain-Specific Tokenization. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Javed, D., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). Student Performance Analysis to Identify Students at Risk of Failure. International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Systems. [CrossRef]

- Ihsan, U., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashraf, H., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). A Real-Time Intelligent Surveillance System for Suspicious Behavior and Facial Emotion Analysis Using YOLOv8 and DeepFace. Engineering Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Feilong, Q., Khan, N. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). Improved YOLOv5 Lane Line Real Time Segmentation System Integrating Seg Head Network. Engineering Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, U., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). Graph Neural Networks for Drug–Drug Interaction Prediction—Predicting Safe Drug Pairings with AI. Engineering Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ray, S. K., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). Future Planning Based on Student Movement Linked with Their Wi-Fi Signals. Engineering Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Wiredu, J. K., Baagyere, E. Y., Nakpih, C., & Aabaah, I. (2024). A Novel Proximity-based Sorting Algorithm for Real-Time Numerical Data Streams and Big Data Applications. Available at SSRN 5249957. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M., Tripathi, T., & Kumar, C. O. (2025). Cluster Sort: A Novel Hybrid Approach to Efficient In-Place Sorting Using Data Clustering. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Javed, D., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashfaq, F., Khan, N. A., Das, S. R., & Singh, S. (2025). Student Performance Analysis to Identify the Students at Risk of Failure. International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Systems. [CrossRef]

- Riskhan, B., & Hossain, M. S., Ashfaq, F. (2023). Religious Sentiment Analysis. Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition: Proceedings of CIPR.

- Revathy, G., Senthilkumar, J., Gurumoorthi, E., & Shyamalagowri, M. (2023, December). Reinforcement Learning with Enhanced Bubble Sort for Wireless Mesh Networks Node Selection. In International Conference on Intelligent Systems in Computing and Communication (pp. 72-80). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashfaq, F., Ahmed, H. M., & Khan, A. (2024). AI-Driven Framework for Location-Aware Sentiment Analysis and Topic Classification of Public Social Media Data in West Malaysia. [CrossRef]

- Akila, D., Raja, S. R., Revathi, M., Ashfaq, F., & Khan, A. A. (2025). Text Clustering on CCSI System using Canopy and K-Means Algorithm. International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Systems. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadagha, M. (2025). Comparative Study of Sorting Algorithms: Adaptive Techniques, Parallelization, for Mergesort, Heapsort, Quicksort, Insertion Sort, Selection Sort, and Bubble Sort. engrxiv.org.

- N. Jhanjhi, "Comparative Analysis of Frequent Pattern Mining Algorithms on Healthcare Data," 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Bahrain, Bahrain, 2024, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Showri, N. S., Koushik, S. V., Shreya, C. R., Urjitha, P., & Divya, C. D. (2025). Optimizing Sorting Algorithms for Small Arrays: A Comprehensive Study of the Chunked Insertion Sort Approach. In Advancements in Optimization and Nature-Inspired Computing for Solutions in Contemporary Engineering Challenges (pp. 299-312). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M. H. G., Malik, J. A., Akhtar, M., Baloch, M. A., & Rajwana, M. A. (2025). Sort Data Faster: Comparing Algorithms. Southern Journal of Computer Science, 1(02), 28-37.

- Bakare, K. A., Okewu, A. A., Abiola, Z. A., Jaji, A., & Muhammed, A. (2024). A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SORTING ALGORITHMS: EFFICIENCY AND PERFORMANCE IN NIGERIAN DATA SYSTEMS. FUDMA JOURNAL OF SCIENCES, 8(5), 1-5.

- Jhanjhi, N.Z. (2025). Investigating the Influence of Loss Functions on the Performance and Interpretability of Machine Learning Models. In: Pal, S., Rocha, Á. (eds) Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).