Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Synthesis Method (Synthesis of M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx)

2.3. Material Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

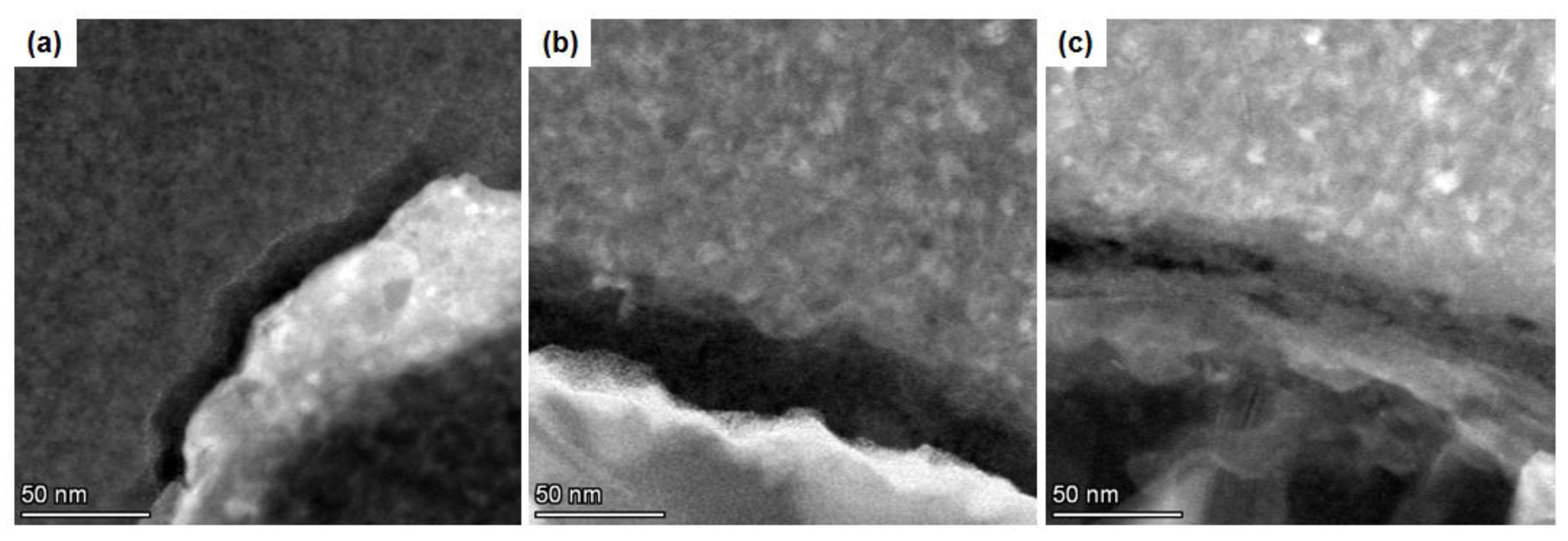

3.1. Characterization of M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx

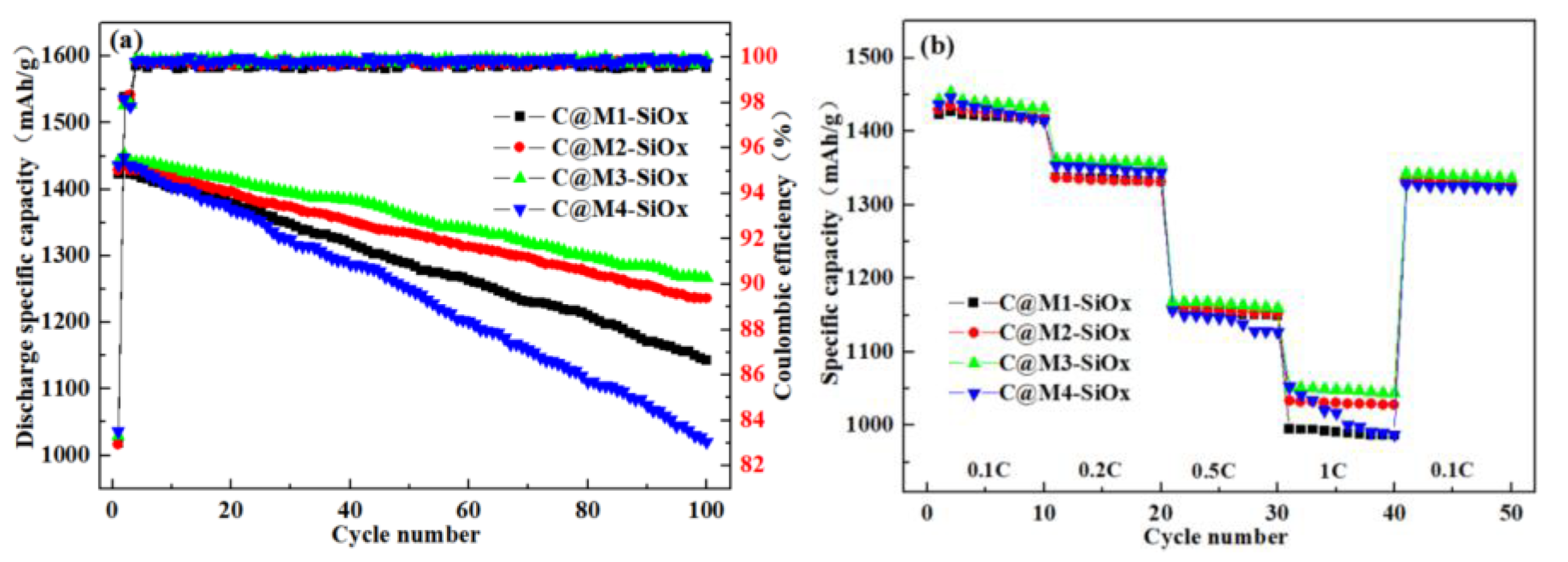

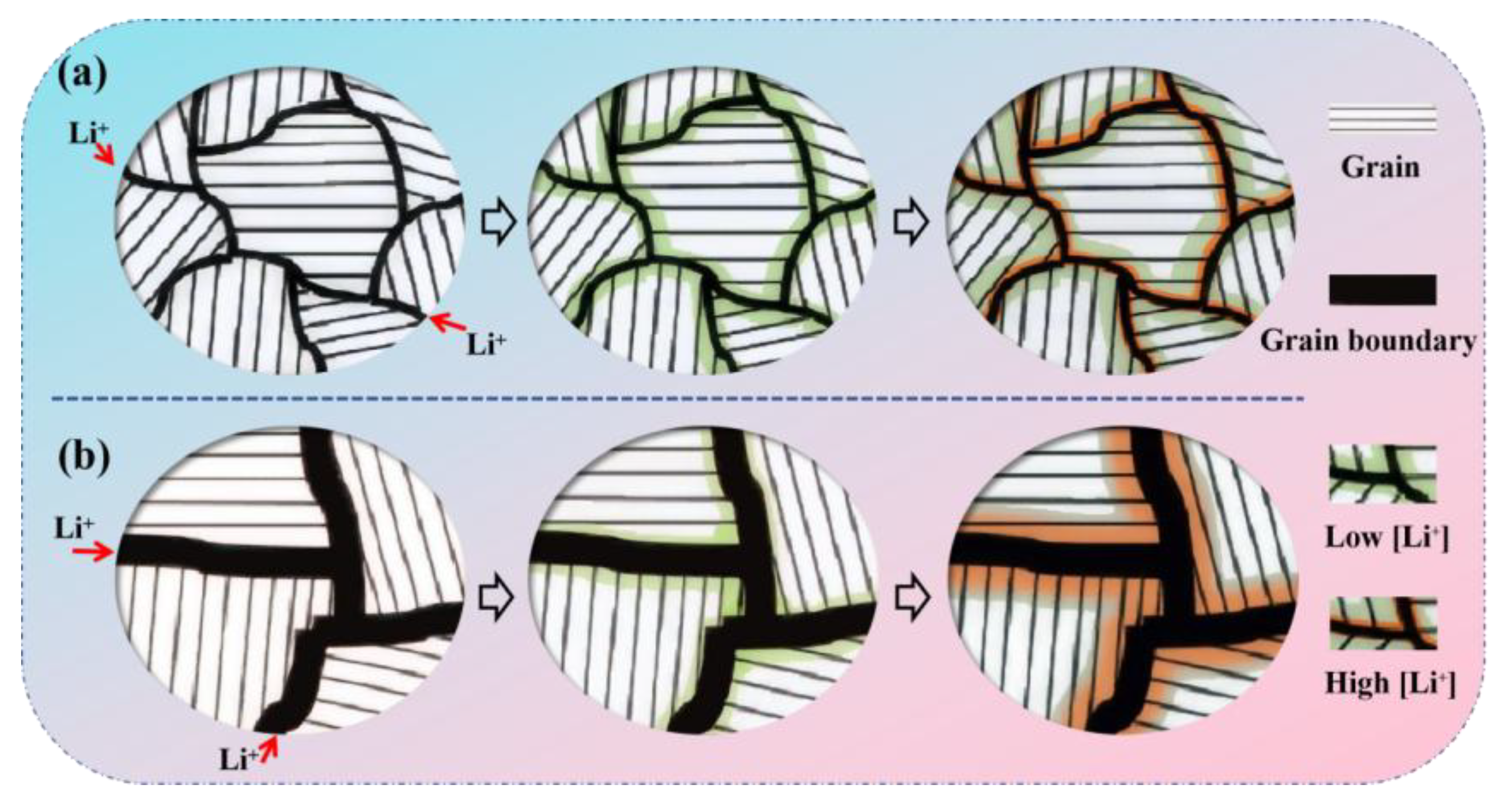

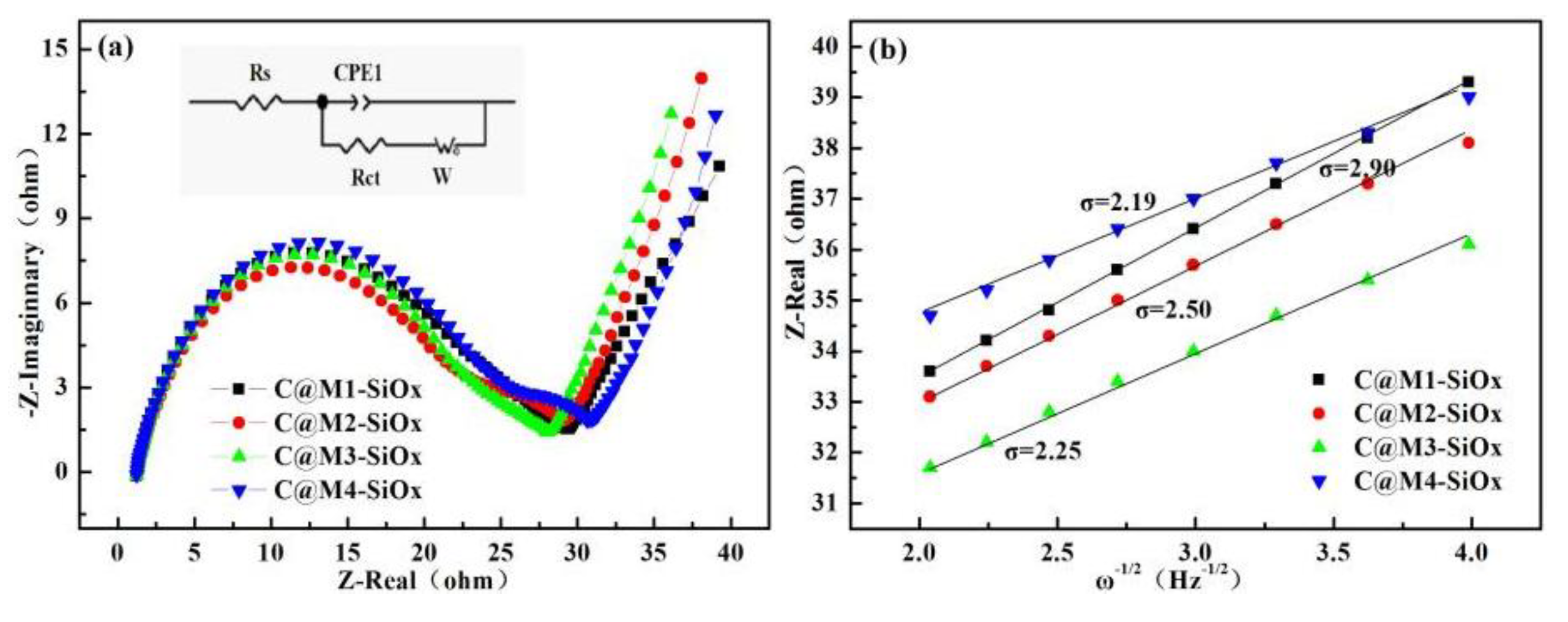

3.2. Electrochemical Properties of C@M-SiOx

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.J.; Du, M.J.; Liu, P.F.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.J.; Sun, H.L.; Sun, Q.J.; Wang, B. Exploring the Influence of Oxygen Distribution on the Performance of SiOx Anode Materials. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.J.; Tan, X.; Shi, Z.Z.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, Y.R.; Wang, F.X.; He, J.R.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, X.B.; Wang, G.J.; Wang, T.; Wu, Y.P. SiOx Based Anodes for Advanced Li-Ion Batteries: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Oh, S.M.; Park, E.; Scrosati, B.; Hassoun, J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H; Belharouak, I; Sun, Y. K. Highly Cyclable Lithium-Sulfur Batteries with a Dual-Type Sulfur Cathode and a Lithiated Si/SiOx Nanosphere Anode. Nano Lett. 2020, 15, 2863–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Park, H.; Ha, J.; Kim, Y.T.; Choi, J. Dual-Carbon-Confined Hydrangea-Like SiO Cluster for High-Performance and Stable Lithium Oon Batteries. J. Ind. and Eng. Chem. 2021, 101, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Fu, C.K.; Li, R.L.; Du, C.Y.; Gao, Y.Z.; Yin, G.P.; Zuo, P.J. High Performance SiOx Anode Enabled by AlCl3-MgSO4 Assisted Low-Temperature Etching for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 557, 232537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.X.; Fu, R.S.; Ji, J.J.; Feng, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.P. Unveiling the Effect of Surface and Bulk Structure on Electrochemical Properties of Disproportionated SiOx Anodes. Chemnanomat 2020, 6, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.Y.; Yang, L.L.; Lv, D.; Song, R.F.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.B.; Zhong, C. Preparation of SiOx Anode with Improved Performance Through Reducing Oxygen Content, Controlling SiO2 Crystallization, and Carbon-Coating. J. Solid State Electro. 2025, 29, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Shi, L.K.; Lang, Z.M.; Jia, G.X.; Lan, D.W.; Cui, Y.F.; Cui, J.L. Selenium Element Doping to Improve Initial Irreversibility of C/SiOx Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electroanal. Chem. 2025, 977, 118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.Y.; Huang, Z.; Fu, F.B. Enhancing Lithium Storage Performance of Carbon/SiOx Composite via Coating Edge-Nitrogen-Enriched Carbon. Int. J. Hydrogen Eenerg. 2024, 91, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Kang, T.X.; Li, S.F.; Ma, Z.; Nan, J.M. A Temperature-Controlled Chemoswitching Aqueous Binder and In Situ Binding Strategy for Stabilizing SiOx Anodes of Lithium-Ion Batteries. " ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 17855–17868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhong, C.; Hu, W.B. Mg-Doped, Carbon-Coated, and Prelithiated SiOx as Anode Materials with IImproved Initial Coulombic Efficiency for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Carbon Energy 2024, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Jo, S.; Na, I.; Oh, S.M.; Jeon, Y.M.; Park, J.G.; Koo, B.; Hyun, H.; Seo, S.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Lim, J.C.; Lim, J. Homogenizing Silicon Domains in SiOx Anode during Cycling and Enhancing Battery Performance via Magnesium Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 52202–52214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y,; Jiang, T. T.; Chen, G.Z. Mechanisms and Product Options of Magnesiothermic Reduction of Silica to Silicon for Lithium-Ion Battery Applications. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 651386. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.X.; Zhao, Y.M.; Chen, H.X.; Lu, Z.Y.; Tian, Y.F.; Xin, S.; Li, G.; Guo, Y.G. Reduced Volume Expansion of Micron-Sized SiOx via Closed-Nanopore Structure Constructed by Mg-Induced Elemental Segregation. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2024, 63, e202401973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.X.; Du, X.F.; Liu, T.; Zhuang, X.C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, B.Q.; Zhang, S.H.; Gao, C.H.; Xu, G.J.; Zhou, X.H.; Cui, G.L. Robust and Fast-Ion Conducting Interphase Empowering SiOx Anode Toward High Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.L.; Song, R.F.; Wan, D.Y.; Ji, S.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.B.; Zhong, C. Magnesiothermic Reduction SiO Coated with Vertical Carbon Layer as High-Performance Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, B.G.; Choi, J.H.; Park, M.S.; Lee, S.M. Swelling-Controlled Double-Layered SiOx/Mg2SiO4/SiOx Composite with Enhanced Initial Coulombic Efficiency for Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7161–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.H.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Y.Y.; Du, X.P.; Chen, C.; Zhou, J.H.; Bi, Z.; Xuan, X.D.; Guo, Y.C. Tang, Y. Zhang, A.B.; Yang, CH. Tuning the Stable Interlayer Structure of SiOx-Based Anode Materials for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 8449–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Z.; Shea, J.; Liu, J.X.; Hagh, N.M.; Nageswaran, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.Y.; Kwon, G.; Son, S.B.; Liu, T.C.; Gim, J.; Su, C.C.; Dong, P.; Fang, C.C.; Li, M.T.; Amine, K.; Jankairaman, U. Comparative Study of Vinylene Carbonate and Lithium Difluoro(oxalate)borate Additives in a SiOx/Graphite Anode Lithium-Ion Battery in the Presence of Fluoroethylene Carbonate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7648–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.F.; Di, J.; Lv, D.; Yang, L.L.; Luan, J.Y.; Yuan, H.Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.B.; Zhong, C. Improving the Electrochemical Properties of SiOx Anode for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries by Magnesiothermic Reduction and Prelithiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7849–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, X.; Dong, Y.W.; Xiong, M.; Wang, B.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Q.C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, R.H. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Matrix to Optimize Cycling Stability of Lithium Ion Battery Anode from SiOx Materials. Inorganics 2024, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, G.Y.; Yang, H.X.; Geng, X.B.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, C.T.; Huang, L.Q.; Luo, X.T. Three-Dimensional Porous Si@SiOx/Ag/CN Anode Derived from Deposition Silicon Waste toward High-Performance Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 43887–43898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, K.; Jeon, S.; Ko, D.S.; Jung, I.S.; Kim, J.H.; Ito, K.; Kubo, Y.; Takei, K.; Saito, S.; Cho, Y.H.; Park, H.; Jang, J.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, W.; Koh, M.; Uosaki, K.; Doo, S.G.; Hwang, Y.; Han, S. Evolving Affinity between Coulombic Reversibility and Hysteretic Phase Transformations in Nano-Structured Silicon-Based Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domi, Y.; Usui, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakaguchi, H. Effect of Silicon Crystallite Size on Its Electrochemical Performance for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Technol-Ger 2019, 7, 1800946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhan, O.; Umirov, N.; Lee, B.M.; Yun, J.S.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.S. A Facile Carbon Coating on Mg-Embedded SiOx Alloy for Fabrication of High-Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2201426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, H.; Au, M.; Chen, N.; Heiden, P.A.; Yassar, R.S. In Situ Electrochemical Lithiation/Delithiation Observation of Individual Amorphous Si Nanorods. Acs Nano 2011, 5, 7805–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M.T.; Ryu, I.; Lee, S.W.; Wang, C.M.; Nix, W.D.; Cui, Y. Studying the Kinetics of Crystalline Silicon Nanoparticle Lithiation with In Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 6034–+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, J.Y.; Sun, J.K.; Yin, Y.X.; Wan, L.J.; Guo, Y.G. Watermelon-Inspired Si/C Microspheres with Hierarchical Buffer Structures for Densely Compacted Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Lv, P.P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z.H.; Teng, Y.Q.; Zhao, L.N.; Zhu, Z.M. Watermelon-Like Structured SiOx-TiO2@C Nanocomposite as a High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1605711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrodes | Rs(Ω) | Rct(Ω) | σ | DLi+(cm2.S-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C@M1-SiOx | 1.2 | 29.45 | 2.9 | 1.112*10-10 |

| C@M2-SiOx | 1.21 | 29.43 | 2.56 | 1.427*10-10 |

| C@M3-SiOx | 1.28 | 28.34 | 2.25 | 1.847*10-10 |

| C@M4-SiOx | 1.23 | 31.18 | 2.19 | 1.950*10-10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).