1. Introduction

Aging represents one of biology's greatest challenges, yet the mechanisms driving its progression remain incompletely understood. While contemporary geroscience has made progress through the hallmarks of aging framework, this taxonomy primarily describes downstream manifestations of aging rather than the upstream forces that initiate and unify them (López-Otín et al. 2023). The critical question of what drives their interconnectedness requires a unifying mechanistic framework.

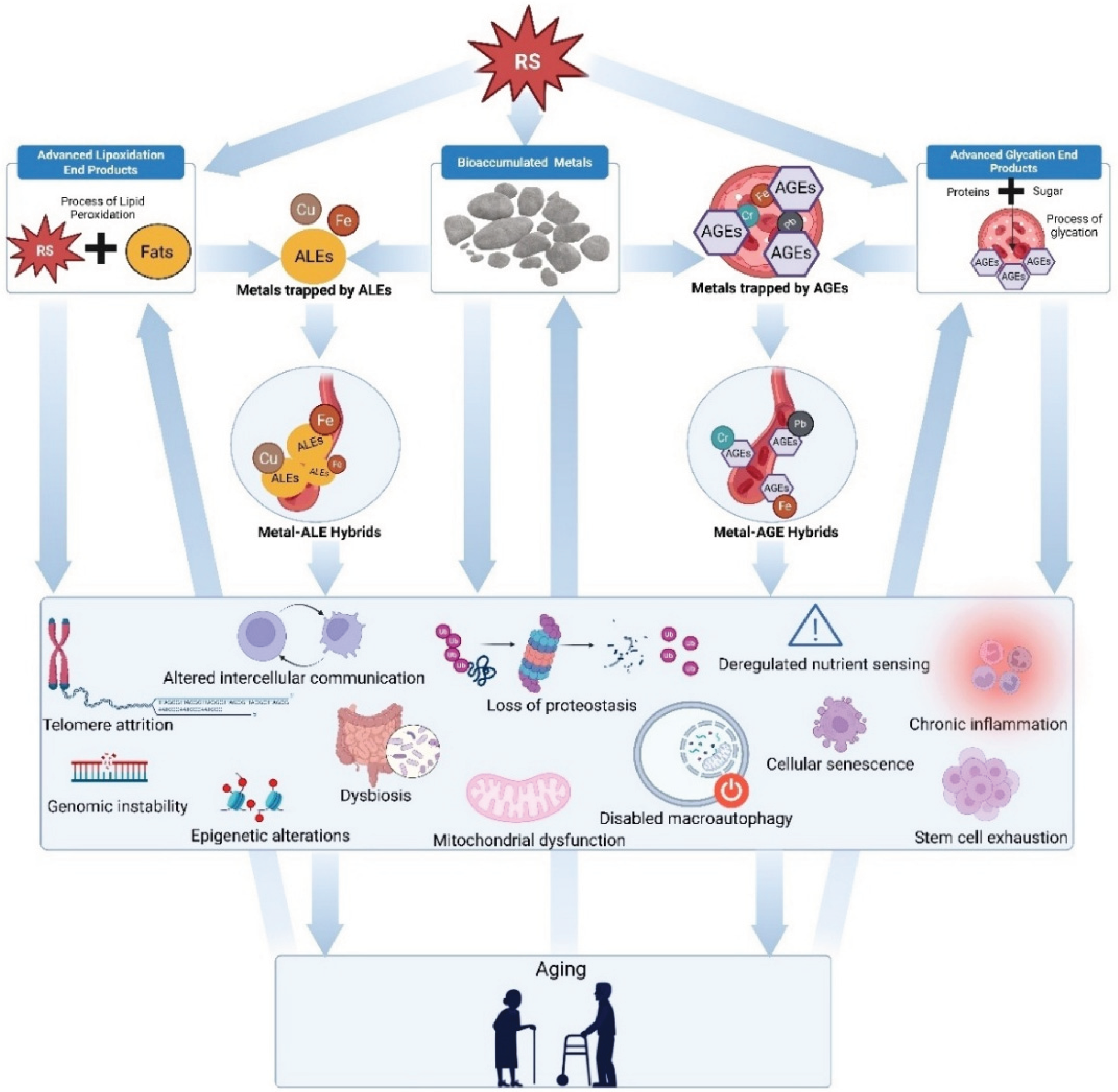

We propose the Conglomerate Theory of Aging, which identifies four synergistic, reactive species (RS) precipitated processes as primary drivers of decline: bioaccumulation of metals, accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs), and the formation of persistent metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid complexes. Unlike existing paradigms that treat individual hallmarks as discrete phenomena, this theory postulates that metals, AGEs, and ALEs operate through parallel, synergistic pathways to amplify cellular dysfunction following incomplete reactive species neutralization.

The mechanistic foundation of our theory rests on three interconnected processes. Transition metals catalyze oxidative damage through Fenton reactions while disrupting proteostasis (Curtain et al. 2001). AGEs crosslink macromolecules impair extracellular matrix dynamics and activate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways that sustain tissue damage (Brownlee 2001). ALEs, generated through lipid peroxidation, form covalent adducts with proteins and nucleic acids. These disrupt mitochondrial and lysosomal function and drive the chronic inflammation characteristic of aged tissues (Poli et al. 2004). The pathogenic impact of these processes is amplified through their interactions. Metals catalyze both AGE and ALE formation while binding to these modified macromolecules, creating stable hybrid complexes that resist degradation and exhibit enhanced oxidative activity (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011). This convergence establishes self-perpetuating damage cycles that accelerate multiple hallmarks simultaneously, transforming cellular stress into progressive functional decline.

By integrating these upstream drivers into a unified framework, the Conglomerate Theory of Aging addresses the gap between aging theory and therapeutic intervention. Our model elucidates the forces underlying hallmark interdependence while identifying actionable targets for disrupting aging at its source, offering new opportunities for extending lifespan.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

The hallmarks of aging have revolutionized geroscience by establishing a comprehensive taxonomy of age-related dysfunction. Yet this framework's focus on downstream processes has left unresolved the question of what upstream factors initiate and orchestrate these hallmarks into systemic decline. Mounting evidence now implicates three interrelated, reactive species precipitated processes as central drivers of aging: metal bioaccumulation, AGE formation, and ALE accumulation.

Figure 1 demonstrates how exposure to diverse reactive species may initiate a self-perpetuating cycle of damage, ultimately leading to compounding and exponential impacts of systemic aging.

2.1. Metal Bioaccumulation

Transition metals represent a paradox of biological necessity and pathogenic potential. While iron, copper, and zinc serve as essential cofactors for enzymatic processes and cellular homeostasis, their progressive accumulation with age transforms these vital elements into instruments of cellular destruction (Halliwell and Gutteridge 2007). This transformation occurs through their capacity to catalyze Fenton chemistry, generating hydroxyl radicals that systematically damage DNA, proteins, and lipids with efficiency (Valko et al. 2007).

The pathogenic consequences of metal bioaccumulation manifest across multiple organ systems with consistency. Iron overload in the substantia nigra exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease, while copper dysregulation catalyzes amyloid-β aggregation in Alzheimer's disease, directly impairing proteostasis through the formation of resistant protein complexes (Zecca et al. 2004; Curtain et al. 2001). These effects align precisely with established aging hallmarks, revealing metals as active orchestrators of cellular decline.

2.2. Advanced Glycation End Products

AGEs emerge from the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids by reducing sugars and reactive species (particularly reactive carbonyls), a process that accelerates exponentially under conditions of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress (Brownlee 2001). These modifications alter macromolecular structure and function, creating crosslinked networks that resist degradation and accumulate inexorably in long-lived proteins such as collagen.

The pathogenic impact of AGEs extends far beyond structural modification. Through activation of the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), these compounds trigger NF-κB-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress, establishing a self-reinforcing cycle of tissue damage that exacerbates cellular senescence and metabolic dysfunction (Ott et al. 2014). Clinical evidence demonstrates that AGE accumulation correlates directly with diabetic complications, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders, underscoring their broad significance in age-related pathology.

2.3. Advanced Lipoxidation End Products

ALEs arise from the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids initiated by reactive species (particularly reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species), generating reactive aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde that covalently modify cellular components with indiscriminate efficiency (Uchida 2003; Poli et al. 2004). These modifications disrupt mitochondrial and lysosomal function, impair proteostasis, and promote the chronic inflammatory state that characterizes aged tissues.

The significance of ALEs in aging has been systematically underappreciated despite mounting evidence of their involvement in neurodegenerative diseases, atherosclerosis, and metabolic dysfunction. Their capacity to form stable adducts with proteins and nucleic acids, combined with their resistance to cellular repair mechanisms, positions ALEs as crucial mediators of age-related cellular decline.

2.4. Metal-AGE and Metal-ALE Hybrid Complexes

Both AGEs and ALEs can chelate transition metals, forming stable hybrid complexes that resist degradation while exhibiting enhanced oxidative activity (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011). These hybrids establish a pathogenic feedback cycle: metals accelerate AGE and ALE formation through oxidative catalysis, while AGEs and ALEs stabilize metal ions, amplifying their toxic effects.

The clinical relevance of these hybrid complexes is demonstrated in amyloid-β plaques in Alzheimer's disease with the sequestration of zinc and copper, forming metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrids that catalyze neuronal oxidative damage (Curtain et al. 2001). The Conglomerate Theory of Aging integrates these observations into a unified mechanistic framework, positioning metal bioaccumulation, AGE and ALE formation, and their hybrid complexes as upstream initiators of aging hallmark interconnections following initial formation through reactive species quenching inefficiency. This framework provides both a mechanistic understanding of simultaneous aging phenotype emergence and a foundation for combinatorial therapies targeting the aging process at its source.

2.5. Metal-Induced Protein Crosslinking

The formation of specific crosslinks has been characterized through detailed mechanistic studies. Liu et al. (2004) investigated Cu(II)-catalyzed oxidation of 4-alkylimidazoles in the presence of amines as surrogates for histidine and lysine side chains. A model His-Lys crosslink was isolated and structurally characterized as a 5-alkyl-5-hydroxy-4-(alkylamino)-1,5-dihydroimidazol-2-one by NMR and mass spectrometry. Evidence that the 2-imidazolone serves as an intermediate was provided by the observation that higher yields of the crosslink adduct were obtained starting with the 2-imidazolone.

The biological significance of metal-induced crosslinking is demonstrated by studies showing that this process occurs in living cells. Kawczynski and Shugar (1987) demonstrated crosslinking of proteins to DNA in live Novikoff ascites hepatoma cells exposed to different concentrations of CuSO₄, Pb(NO₃)₂, HgCl₂, and AlCl₃. The optimal crosslinking occurred at metal concentrations of 0.5 mM for CuSO₄, HgCl₂, and AlCl₃, while optimal crosslinking for Pb(NO₃)₂ occurred at 5 mM. Immunochemical analysis demonstrated that some members of matrix, chromatin, lamins, and cytokeratin protein families became crosslinked to DNA, with each metal exhibiting a distinct pattern.

3. Metal Bioaccumulation and the Hallmarks of Aging

Metal bioaccumulation represents one of the most underappreciated yet fundamental drivers of biological aging. The progressive accumulation of metals, particularly iron, copper, and zinc, transforms these essential cofactors into potent gerontogens capable of initiating and amplifying virtually every recognized hallmark of aging (Niedernhofer et al. 2018).

3.1. Genomic Instability

The capacity of metals to destabilize genomic integrity operates through multiple mechanistic pathways, each contributing to the relentless accumulation of DNA damage that characterizes aging cells. Valko et al. (2005) demonstrated that iron and copper catalyze hydroxyl radical formation through Fenton reactions, creating double-strand DNA breaks and base modifications in human fibroblasts with devastating efficiency. This oxidative assault is amplified in aged tissues, where mitochondrial dysfunction compounds ROS production, as evidenced in neurological models where iron overload accelerated DNA damage while simultaneously reducing repair capacity (Zecca et al. 2004).

3.2. Telomere Attrition

Telomeres represent the Achilles' heel of cellular aging, and their vulnerability to metal-catalyzed oxidative damage has profound implications for organismal longevity. The protective DNA-protein complexes at chromosome ends possess inherently limited repair mechanisms, rendering them exquisitely sensitive to the hydroxyl radicals generated by transition metal-catalyzed Fenton reactions (Houben et al. 2008).

Experimental evidence demonstrates that iron in its Fe(II) state catalyzes oxidative lesions in telomeric DNA, resulting in accelerated shortening that can be decelerated through antioxidant intervention. This sensitivity extends beyond direct oxidative damage. Research by Sfeir et al. (2009) revealed that oxidative stress causes replication fork collapse at telomeres, creating fragile telomeric sites that further promote attrition.

3.3. Epigenetic Alterations

The epigenetic disruption caused by metal exposure exemplifies the multifaceted nature of metal toxicity. Arsenic exposure creates a paradoxical pattern of simultaneous DNA hypomethylation and hypermethylation, as demonstrated by Cui et al. (2006) in HepG2 liver cells, where promoter hypomethylation of tumor suppressor genes occurred alongside hypermethylation of the same genes in lung adenocarcinomas. Similarly, cadmium and nickel inhibit DNA methyltransferases, causing global hypomethylation and oncogene activation, illustrating how metals destabilize epigenetic regulation to contribute to age-related transcriptional dysfunction (Zhao et al. 2022; Hossain et al. 2012).

3.4. Loss of Proteostasis

Metal-induced protein aggregation represents a hallmark pathogenic mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Uversky et al. (2001) demonstrated that copper and iron catalyze α-synuclein and β-amyloid misfolding through redox cycling, creating insoluble aggregates that resist proteasomal degradation. In Alzheimer's disease, Curtain et al. (2001) identified zinc and copper enrichment in amyloid plaques, where they perpetuate oxidative crosslinking and neuronal toxicity. Cadmium compounds this dysfunction by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, disrupting protein folding and activating the unfolded protein response, further impairing proteostasis under chronic exposure conditions.

3.5. Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

Metal imbalances systematically disrupt the metabolic pathways central to nutrient sensing. Sung et al. (2019) demonstrated that iron overload in hepatocytes inhibits insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation, effectively blunting insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Conversely, zinc deficiency impairs mTORC1 activity, as observed in aged murine models with dysregulated zinc transporters. These disruptions establish a metabolic environment that favors age-related insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction.

3.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria function simultaneously as sources and targets of metal-induced damage, creating a vicious cycle of energetic decline. Zecca et al. (2004) demonstrated that iron accumulation in the substantia nigra of Parkinson's patients disrupts complex I activity while increasing ROS production twofold. Cadmium exposure similarly causes mitochondrial membrane depolarization and reduced ATP synthesis in neuronal cells, exacerbating energy deficits. This cycle of impaired electron transport, ROS-mediated mitochondrial DNA damage, and dysfunctional mitochondria releasing additional metals represents a central mechanism in the pathogenesis of aging.

3.7. Cellular Senescence

The capacity of heavy metals to induce cellular senescence has been definitively established, as cadmium exposure promotes a senescence-associated secretory phenotype characterized by IL-6 and TNF-α secretion, amplifying tissue damage through chronic inflammation (Cheng et al. 2025). This SASP induction reinforces local cellular dysfunction while propagating systemic aging processes.

3.8. Stem Cell Exhaustion

Metal-induced oxidative stress represents a critical contributor to stem cell exhaustion, systematically depleting the regenerative capacity essential for tissue maintenance. Rossi et al. (2005) demonstrated that iron accumulation in hematopoietic stem cells leads to increased DNA double-strand breaks, reducing self-renewal capacity and impairing hematopoietic maintenance. Chronic cadmium exposure in neural progenitor cells depletes intracellular glutathione reserves, resulting in heightened oxidative damage and impaired neurogenesis (Xu et al. 2011). These findings underscore the vulnerability of stem cell populations to metal-induced oxidative insults.

3.9. Altered Intercellular Communication

The disruption of intercellular communication by metal toxicity establishes chronic inflammatory states that accelerate tissue aging. Cadmium activates NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways in renal cells even at subtoxic concentrations, leading to sustained pro-inflammatory mediator production (Li et al. 2021). The secretion of SASP factors from senescent cells compounds this toxic microenvironment, promoting senescence and inflammation in neighboring cells. The combined effect of direct metal-induced signaling disruption and secondary SASP-mediated inflammation accelerates tissue dysfunction and age-related pathological progression.

3.10. Disabled Macroautophagy, Chronic Inflammation and Dysbiosis

Bioaccumulated metals exert profound effects on macroautophagy, establishing chronic inflammatory states and disrupting gut microbial balance. Chargui et al. (2011) demonstrated that subtoxic cadmium doses trigger metal accumulation in lysosomes, initially activating autophagy as an adaptive response. However, continued exposure creates maladaptive outcomes: excessive autophagic vacuolization and impaired lysosomal function culminate in cytotoxicity and cell death. Lead exposure similarly induces abnormal hippocampal autophagy, disrupting the Akt/mTOR pathway and impairing autophagosome-lysosome fusion, resulting in autophagosome accumulation and neural injury (Zhang et al. 2023).

The inflammatory consequences of metal bioaccumulation extend systemically, with lead, cadmium, and arsenic inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and endoplasmic reticulum stress that activate inflammatory signaling cascades. These effects are amplified by autophagy dysfunction, as impaired clearance of damaged cellular components sustains danger signals and immune activation. The interplay between metal-induced autophagy disruption and chronic inflammation proves particularly destructive in organs with high metal accumulation, contributing to cardiovascular and renal disease progression.

Emerging evidence suggests that bioaccumulated metals also disrupt gut microbiome composition and function. Heavy metal exposure reduces microbial diversity, favors pathogenic bacterial growth, and impairs beneficial microbial metabolite production (Zhu et al. 2024). These changes compromise intestinal barrier function, promote systemic inflammation, and potentially reduce the gut's capacity for metal detoxification and excretion. The synergistic impact of metals on dysbiosis and inflammation amplifies their detrimental effects on host health, particularly in the context of aging.

3.11. Metal Bioaccumulation and Aging Clocks

Multiple human cohort studies have demonstrated that systemically accumulated metals leave quantifiable imprints on DNA methylation-based aging clocks, providing direct evidence for metal-driven aging acceleration. Ryoo et al. (2025) analyzed 2,201 adults aged 50 and older, demonstrating that higher blood lead and cadmium levels predicted faster aging across eight epigenetic clocks, with the strongest effects observed for Hannum, GrimAge, and PhenoAge accelerations. Quartile-based analyses revealed consistent and strong associations between greater exposure to lead or cadmium and epigenetic age acceleration.

The mechanistic basis for metal-mediated aging acceleration involves multiple pathways. Brewer (2010) provided comprehensive evidence that both copper and iron accumulate during aging and contribute to oxidative damage that builds up as natural selection ceases to act after approximately age 50. The oxidant damage from excess metal stores contributes to diseases of aging including Alzheimer's disease, arteriosclerosis, and diabetes mellitus. Particularly concerning, individuals in the highest quintile of copper intake, when consuming a relatively high-fat diet, demonstrated cognitive decline at over three times the normal rate.

Boyer et al. (2023) conducted mixture-based research using Bayesian kernel machine regression models, revealing that a nonessential metal mixture containing cadmium, arsenic, and tungsten was positively associated with GrimAge and DunedinPACE acceleration, while an essential metal mixture including selenium, zinc, and molybdenum was associated with lower epigenetic age acceleration. Cadmium alone elevated all clocks tested, including Horvath and Hannum, demonstrating its particular potency as an aging accelerant.

The cellular mechanisms underlying metal-mediated aging acceleration have been elucidated through studies of transition metal accumulation and cellular senescence. Research has demonstrated that senescent cells accumulate higher levels of transition metals, which in turn accelerates cellular senescence and related diseases through mechanisms including excessive reactive species production, oxidative stress induction, DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction (Xie et al. 2024). Maher (2018) demonstrated that both iron and copper potentiate glutathione loss and nerve cell death, with these metals specifically enhancing nerve cell death under conditions where glutathione levels are reduced, a condition observed in the aging brain and associated with cognitive dysfunction.

4. Advanced Glycation End Products and the Hallmarks of Aging

Advanced glycation end products consistently induce molecular modifications that accelerate with age, hyperglycemia, and oxidative stress. These heterogeneous compounds, formed through non-enzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids, accumulate in long-lived proteins and tissues (Singh et al. 2001; Brownlee 2001). Their progressive buildup functions simultaneously as an aging biomarker and driver of pathological processes, establishing AGEs as central mediators in diabetes, atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

4.1. Genomic Instability

The Maillard reaction initiating AGE formation generates reactive dicarbonyl intermediates that directly assault genomic integrity. Thornalley et al. (2003) demonstrated that methylglyoxal modifies guanine residues in DNA, forming mutagenic adducts such as N2-carboxyethyl-2'-deoxyguanosine. These modifications increased single-strand breaks and G:C → T:A transversions in E. coli lacI gene assays, with nucleotide excision repair-deficient strains showing threefold higher mutation rates. In human fibroblasts, methylglyoxal exposure elevated 8-oxo-dG levels by 40%, directly linking AGE precursors to oxidative DNA damage (Vistoli et al. 2013). These findings align with the Conglomerate Theory's predictions, as metal-catalyzed Fenton reactions amplify ROS production to synergize with glycation in destabilizing genomic integrity.

4.2. Telomere Attrition

AGEs accelerate telomere shortening through oxidative and inflammatory pathways with devastating precision. Studies have demonstrated that diabetic patients exhibit shortened telomeres compared to healthy controls, with research showing that patients with diabetes had telomeres that were 27% shorter in β-cells and 15% shorter in α-cells relative to controls, with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) negatively correlated with telomere length (Tamura et al. 2014). Supporting this relationship, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 37 studies confirmed that patients with type 2 diabetes had shorter telomeres than non-diabetic individuals (standardized mean difference: -3.70; 95% CI: -4.20, -3.20; P < 0.001), with telomere length showing correlation with HbA1c levels and diabetes duration (He et al., 2024). Mechanistically, methylglyoxal-derived histone modifications have been shown to disrupt chromatin dynamics and gene transcription, with MGO adduction of histones occurring at levels comparable to arginine methylation and causing marked disruption of H2B acetylation and ubiquitylation, which could impair the chromatin environment necessary for telomerase recruitment and function (Galligan et al. 2018). This is consistent with findings in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, where progerin accumulation leads to rapid telomere dysfunction and chromosomal aberrations (Benson et al. 2010).

4.3. Epigenetic Alterations

AGEs systematically disrupt epigenetic regulation through RAGE-dependent histone modifications. Ott et al. (2014) demonstrated that AGE-BSA increased H3K9me3 heterochromatin markers by 2.5-fold in renal tubular cells, silencing nephroprotective genes like SIRT1. Conversely, methylglyoxal reduced global DNA methylation by 30% in adipocytes through DNMT3b inhibition, activating pro-inflammatory IL-6 transcription (Galligan et al. 2018). These effects are amplified by metals, as cadmium and iron synergistically enhance AGE-mediated histone deacetylase inhibition, exacerbating chromatin instability in aging tissues.

4.4. Loss of Proteostasis

AGE crosslinking directly impairs protein quality control with relentless efficiency. In collagen, glycation by glyoxal induced β-sheet-rich aggregates resistant to MMP-1 degradation, increasing tensile stiffness by 60% while reducing fracture toughness by 45% (Sell et al. 2014). Methylglyoxal-modified α-synuclein formed oligomers that inhibited the ubiquitin-proteasome system by 70% in neuronal cells, mimicking Parkinson's pathology (Dalfó et al. 2005). These aggregates sequester chaperones like HSP70, depleting their availability for nascent protein folding and creating a cascade of proteostatic collapse.

4.5. Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

AGEs systematically disrupt nutrient-sensing mechanisms through their impact on insulin signaling and metabolic homeostasis. Multiple studies demonstrate that AGEs impair insulin receptor function by promoting receptor glycation and activating RAGE, triggering chronic low-grade inflammation that interferes with downstream signaling (Vlassara and Uribarri 2014). Cai et al. (2012) showed that mice fed high-AGE diets developed impaired glucose tolerance and reduced insulin sensitivity independent of obesity, due to increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and decreased Akt activation in skeletal muscle and liver.

AGEs further upregulate mTOR signaling through oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators, exacerbating age-related metabolic dysfunction. SIRT1, a key regulator of metabolic adaptation and longevity, becomes downregulated in the presence of high AGE and RAGE activity, as demonstrated in studies of diabetic nephropathy and vascular aging (Ott et al. 2014). These findings establish AGEs not as mere byproducts of metabolic dysfunction but as active disruptors of nutrient-sensing pathways.

4.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

AGEs impair mitochondrial function through RAGE-ROS feedback loops that create self-perpetuating cycles of energetic decline. In diabetic mice, cardiac AGE accumulation reduced complex I activity by 35% while increasing superoxide production twofold (Boudina et al. 2007). Methylglyoxal-modified mitochondrial aconitase has been shown in vitro and in cell models to lose most of its enzymatic activity, disrupting TCA cycle flux and ATP synthesis; iron chelation with deferoxamine or similar agents can restore aconitase function, directly linking metal-AGE interactions to mitochondrial failure (Thornalley 2005; Nulton-Persson and Szweda 2001).

4.7. Cellular Senescence

AGE-RAGE signaling drives the senescence-associated secretory phenotype with relentless efficiency. In human aortic smooth muscle cells, AGEs increased p16INK4a expression threefold and SASP cytokine secretion via NF-κB activation (Yamagishi et al. 2012). This aligns with in vivo data showing that senescent cell clearance using dasatinib plus quercetin reduced aortic AGE content by 40% in aged mice, reversing vascular stiffness and demonstrating the bidirectional relationship between AGEs and cellular senescence.

4.8. Stem Cell Exhaustion

Chronic exposure to reactive species generated as a byproduct of AGE accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction systematically impairs the balance between stem cell quiescence and proliferation. In hematopoietic stem cells, elevated ROS levels drive excessive proliferation and differentiation at the expense of self-renewal, ultimately depleting the stem cell pool and reducing tissue regenerative capacity (Beerman and Rossi 2014). AGEs, through activation of RAGE and downstream inflammatory signaling, exacerbate oxidative and metabolic stress in the stem cell niche, further accelerating stem cell exhaustion and loss of regenerative potential.

4.9. Altered Intercellular Communication

AGEs systematically disrupt extracellular matrix signaling through their capacity to modify structural proteins. In tendon collagen, glucosepane crosslinks increased elastic modulus by 50% while reducing collagenase susceptibility fourfold, impairing tissue remodeling capacity (Snedeker et al. 2014). Methylglyoxal-modified ECM triggered anoikis in endothelial cells, reducing capillary density by 30% in diabetic retinopathy models and demonstrating how AGE-mediated matrix modifications compromise vascular integrity.

4.10. Disabled Macroautophagy, Chronic Inflammation, and Dysbiosis

AGEs systematically impair macroautophagy by crosslinking proteins and rendering them resistant to proteolytic degradation, overwhelming the autophagic machinery. Studies demonstrate that AGE-rich diets in rodents result in undegraded protein aggregate accumulation and impaired lysosomal activity, creating hallmarks of disabled macroautophagy (Spandidos et al. 2023; Wu et al. 2021). This impairment not only contributes to cellular dysfunction but also exacerbates age-related diseases by promoting toxic protein aggregate persistence.

AGEs activate RAGE to trigger downstream signaling cascades such as NF-κB that promote pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Experimental models demonstrate that mice fed AGE-rich diets exhibit elevated systemic inflammation, characterized by increased circulating cytokines and immune cell tissue infiltration (Wu et al. 2021; Spandidos et al. 2023). A 2025 study by Zhang et al. found that dietary AGEs promoted intestinal barrier dysfunction and amplified Th2 immune responses through RAGE-TLR4 signaling, linking AGEs to both systemic and mucosal inflammation.

High-AGE diets induce gut dysbiosis characterized by reduced microbial diversity and shifts toward pro-inflammatory bacterial taxa. Spandidos et al. (2023) reported that rats fed AGE-rich diets exhibited decreases in beneficial bacteria such as Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, alongside increases in potentially harmful genera like Desulfovibrio and Helicobacter. Zhang et al. (2025) demonstrated that prolonged dietary AGE intake enriched LPS-producing bacteria while depleting short-chain fatty acid-producing genera, resulting in compromised intestinal barrier function and heightened immune activation.

AGEs thus emerge as potent drivers of multiple aging hallmarks through their capacity to modify macromolecules, activate inflammatory pathways, and disrupt cellular homeostasis. Their integration within the Conglomerate Theory framework reveals AGEs as upstream mediators that amplify damage through interconnected mechanisms, providing crucial targets for interventions aimed at disrupting the aging process at its source.

5. Metal-AGE Hybrids: Formation, Properties, and Pathogenicity

Metal-AGE hybrid complexes arise through the strong affinity of transition metals for glycation-modified proteins, particularly those containing carboxyl, histidine, and lysine residues that have been modified through the Maillard reaction. Investigations by Sajithlal et al. (1998) demonstrated that rat tail tendon collagen incubated with glucose and increasing concentrations of copper ions (5-500 μM) showed metal-dependent enhancement of AGE accumulation. The mechanism involves transition metal ion-catalyzed autoxidation of glucose and Amadori products, generating superoxide radicals that subsequently produce hydrogen peroxide through dismutation. This hydrogen peroxide then generates hydroxyl radicals through the Fenton reaction in the presence of transition metals, leading to enhanced protein crosslinking in glycated proteins (Sajithlal et al. 1998).

Metal-catalyzed enhancement of AGE formation occurs through direct coordination of metals with glycation products. Research by Qian et al. (1998) established that glycated albumin, gelatin, and elastin gain substantial affinity for transition metals, with glycated proteins binding at least three times as much iron as non-glycated proteins. Similarly, glycated albumin and gelatin bind 2-3 times as much copper compared to their non-glycated counterparts. The bound metals retain redox activity, as demonstrated by copper bound to glycated albumin participating in the catalytic oxidation of ascorbic acid (Qian et al. 1998).

Recent investigations by Litvinov et al. (2021) confirmed that d-metal cations, particularly copper(II), intensify AGE formation in glycation reactions while reducing the fluorescence intensity of tryptophan and tyrosine amino acids. This suggests that metals not only promote AGE formation but also contribute to the structural alteration of proteins through amino acid modification. The copper-mediated enhancement of AGE formation occurs through direct metal coordination with glycation products, creating stable metal-AGE hybrid complexes that resist degradation at a likely systemic basis.

The pathogenicity of metal-AGE hybrids extends beyond simple protein modification. Research by Puglielli et al. (2005) demonstrated that AGE-modified collagen telopeptides showed increased capacity to bind Cu(II) ions, with potentiometric titration confirming this enhanced metal chelation capacity. These findings were corroborated by mass spectrometric characterization of the AGE-modified peptide-Cu(II) system, establishing the formation of stable coordination complexes.

6. Advanced Lipoxidation End Products and the Hallmarks of Aging

Advanced lipoxidation end products, generated through polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation, have emerged as critical mediators of age-related cellular dysfunction. As stable, diffusible aldehydes, ALEs covalently modify proteins, DNA, and lipids, thereby interfering with essential cellular processes and contributing to the progressive decline in tissue integrity that characterizes aging. Mounting evidence links ALEs to several key hallmarks of aging through their capacity to disrupt protein quality control systems, impair mitochondrial bioenergetics, promote inflammatory signaling, and induce cellular stress responses (Pamplona 2008; Grune et al. 2013; Ayala et al. 2014; Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008; Flor & Kron 2016).

6.1. Genomic Instability

ALEs contribute to genomic instability primarily through covalent DNA adduct formation. Reactive aldehydes like 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde, generated during lipid peroxidation, form etheno- and propano-type DNA adducts that disrupt replication and transcription (Marnett 1999; Marnett 2005). These lesions are inherently mutagenic and contribute to chromosomal aberrations, particularly in aging tissues where antioxidant defenses decline. Notably, 4-HNE adducts interfere with base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair pathways, exacerbating DNA damage accumulation (Marnett 1999) in a manner consistent with the age-associated rise in somatic mutations and genomic rearrangements observed in accelerated aging models.

6.2. Loss of Proteostasis

ALEs demonstrate a profound capacity to disrupt proteostasis, a hallmark characterized by the accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins. Reactive aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde form covalent adducts with lysine, histidine, and cysteine residues on proteins, leading to structural modifications, crosslinking, and functional loss (Uchida 2003; Grune et al. 2013). These ALE-modified proteins resist degradation by both proteasomal and lysosomal systems, resulting in their accumulation and the formation of cytotoxic aggregates that disrupt cellular homeostasis (Grune et al. 2013). This process manifests conspicuously in neurodegenerative diseases, where ALE-adducted proteins are found within pathological inclusions such as Lewy bodies and neurofibrillary tangles (Butterfield & Halliwell 2019).

6.3. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

ALEs exert well-established effects on mitochondrial function, another central hallmark of aging. Lipid peroxidation products like 4-HNE diffuse into mitochondria and react with mitochondrial proteins, impairing electron transport chain components and disrupting ATP production (Dalle-Donne et al. 2006). The accumulation of ALEs in mitochondria, observed consistently in aged tissues, correlates with decreased mitochondrial function and increased reactive species production, further exacerbating cellular damage (Dalle-Donne et al. 2006).

6.4. Cellular Senescence

ALEs play a direct role in the induction and maintenance of cellular senescence. Exposure to 4-HNE induces a senescent phenotype across various cell types, characterized by permanent growth arrest, increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Flor and Kron 2016; Flor and Kron 2018). ALEs trigger DNA damage responses and activate p53 and p21 pathways, key regulators of senescence (Flor and Kron 2016). The accumulation of ALE-modified proteins in senescent cells further impairs their ability to maintain proteostasis and contributes to the pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype observed in aging tissues (Flor and Kron 2018).

6.5. Chronic Inflammation

ALEs maintain a close association with chronic inflammation, a hallmark integrative to aging processes. ALEs such as 4-HNE and MDA-modified proteins function as damage-associated molecular patterns, recognized by pattern recognition receptors on immune cells, leading to inflammatory signaling pathway activation (Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008). These modified proteins stimulate macrophages and other immune cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, perpetuating cycles of tissue damage and inflammation (Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008; Ayala et al. 2014). ALEs accumulate at elevated levels in inflammatory lesions of atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, and other age-related diseases, underscoring their role in sustaining chronic, low-grade inflammation throughout aging (Ayala et al. 2014).

6.6. Disabled Macroautophagy

Moderate evidence supports that ALEs contribute to impaired macroautophagy, a process essential for the degradation and recycling of damaged cellular components. ALEs, such as 4-hydroxynonenal, can modify lysosomal and autophagic proteins, leading to reduced efficiency of autophagic flux and accumulation of undegraded substrates (Grune et al. 1997). Experimental studies have demonstrated that the accumulation of ALE-modified proteins impairs the function of the proteasome and lysosomal systems, resulting in the buildup of dysfunctional proteins and organelles that would normally be cleared by autophagy (Grune et al. 1997). This impairment in protein quality control is observed in aging tissues and contributes to age-related cellular dysfunction and disease progression (Dalle-Donne et al. 2006).

6.7. Altered Intercellular Communication

ALEs also moderately influence altered intercellular communication, particularly through their role in promoting pro-inflammatory signaling. ALE-modified proteins act as damage-associated molecular patterns that can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors on immune cells, leading to the activation of inflammatory pathways and the release of cytokines (Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008). This persistent, low-grade inflammation, sometimes termed "inflammaging," disrupts normal communication between cells and tissues, contributing to the systemic decline in tissue function observed with age (Ayala et al. 2014). While this connection is not as direct or robust as for other hallmarks, accumulating evidence supports a contributory role for ALEs in the dysregulation of intercellular signaling networks during aging (Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008; Ayala et al. 2014).

7. Metal-ALE Hybrids: Formation, Properties, and Pathogenicity

The formation of metal-ALE hybrid complexes occurs through the interaction between transition metals and advanced lipoxidation end products generated during lipid peroxidation. Knight and Voorhees (1990) demonstrated that transition metals including cadmium(II), cobalt(II), copper(II), iron(II & III), manganese(II), and nickel(II) all increased the concentration of malondialdehyde and conjugated dienes in linolenic acid systems, with the addition of butylated hydroxytoluene reducing these products, confirming the metal-catalyzed nature of lipid peroxidation.

The mechanism of metal-ALE hybrid formation involves copper-dependent oxidation of lipid hydroperoxides. Research by Girotti et al. (1996) established that Cu(II) promotes lipid peroxidation through reduction to Cu(I) and subsequent formation of lipid-derived peroxyl radicals. This process creates an equilibrium between free Cu(II) and lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) that shifts toward Cu(I) formation and lipid oxidation in the presence of unsaturated fatty acids. The copper-dependent oxidation of lipid hydroperoxides leads to their decomposition to form reactive alkoxyl radicals that attack polyunsaturated fatty acids, initiating the lipid peroxidation chain reaction.

Iron-dependent lipid peroxidation follows similar pathways. Repetto et al. (2009) demonstrated that iron-dependent lipid peroxidation in phospholipid liposomes was enhanced by the presence of copper, cobalt, and nickel ions. The metals promoted lipid peroxidation through H₂O₂ decomposition and direct homolysis of endogenous hydroperoxides, with the resulting lipid peroxidation products forming covalent adducts with proteins to create stable metal-ALE complexes.

The pathogenic implications of metal-ALE hybrid formation are evidenced by studies demonstrating that these complexes resist proteolytic degradation and accumulate in tissues. Research by Nuka et al. (2016) showed that metal-catalyzed oxidation of 2-alkenals generates genotoxic 4-oxo-2-alkenals during lipid peroxidation, with transition metals enhancing the oxidation of the C4-position of 2-octenal, leading to the formation of highly reactive ALE-dG adducts. These findings demonstrated a new pathway for the formation of 4-oxo-2-alkenals during lipid peroxidation and provide a mechanism for metal-catalyzed genotoxicity.

7.1. Lipofuscin: A Paradigmatic Metal-ALE Hybrid

Lipofuscin exemplifies the pathological consequences of metal-ALE hybrid formation in aging tissues. This age pigment accumulates progressively in long-lived, postmitotic cells such as neurons and cardiac myocytes as a complex mixture of highly oxidized lipids, crosslinked proteins, and transition metals, most notably iron and calcium. Lipofuscin formation connects intimately to chronic oxidative stress and impaired lysosomal degradation, where ALEs generated from lipid peroxidation covalently modify proteins, forming aggregates that readily chelate and trap redox-active metals within their structure.

Recent experimental investigations have provided detailed insight into authentic lipofuscin composition and impact. Baldensperger et al. (2024) isolated lipofuscin from human and equine cardiac tissue, revealing iron concentrations several orders of magnitude higher than surrounding tissue, along with characteristic enrichment in proline and other amino acids that confer resistance to proteolytic degradation. The presence of redox-active metals within lipofuscin catalyzes ongoing Fenton-type reactions, generating reactive species that perpetuate oxidative stress and cellular injury. This persistent pro-oxidant activity disrupts both lysosomal and mitochondrial function, leading to increased susceptibility to oxidative damage, lysosomal membrane permeabilization, and impaired autophagic flux.

The pathogenicity of lipofuscin as a metal-ALE hybrid manifests through its cytotoxic effects in experimental models. Lipofuscin aggregates induce cell death at low concentrations, primarily through mechanisms involving oxidative stress and lysosomal dysfunction (Moreno-Garcia et al. 2018). In the aging brain and heart, lipofuscin accumulation associates with declining cellular resilience, chronic inflammation, and progressive loss of tissue function, exemplifying how the intersection of ALE formation and metal accumulation generates persistent, pathogenic aggregates that drive cellular aging and degeneration (Baldensperger et al. 2024; Moreno-Garcia et al. 2018).

8. The Feedback Loop: Damage Begets Damage

A defining characteristic of the Conglomerate Theory of Aging is the self-reinforcing feedback loop that emerges from the interplay among bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrid complexes following their RS initiation. This cycle amplifies molecular and cellular damage, ensuring that once initiated, the aging process accelerates through multiple, interconnected pathways (Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008; Ayala et al. 2014; Grune et al. 1997).

The accumulation of metals such as iron and copper increases the catalytic potential for reactive species production, as demonstrated by studies highlighting iron's role in promoting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in aging tissues (Seo et al.2008). Excess RS damages DNA, proteins, and lipids while accelerating both non-enzymatic glycation and lipid peroxidation, thereby increasing AGE and ALE formation (Uchida 2003; Ayala et al. 2014). As AGEs and ALEs accumulate, they further impair proteostasis and mitochondrial function, exacerbating oxidative and carbonyl stress and creating a permissive environment for additional accumulation events (Grune et al. 1997; Butterfield and Halliwell 2019).

The formation of metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrids introduces additional complexity to this feedback system. Such hybrid complexes would resist degradation and persist in tissues, where their ongoing redox cycling would generate further RS and reactive aldehydes, perpetuating the cycle of molecular damage (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011; Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008). This continuous loop would receive reinforcement through inflammatory pathway activation, notably through the receptor for AGEs, as well as through ALE-modified proteins acting as damage-associated molecular patterns, both of which amplify pro-inflammatory signaling and tissue dysfunction (Ayala et al. 2014).

At the tissue and organismal level, this feedback loop would manifest as age-related extracellular matrix stiffening, impaired autophagy, and widespread tissue dysfunction. AGE and ALE crosslinking, combined with metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid accumulation, may alter tissue mechanical properties and further impairs cellular function (López-Otín et al. 2023; Rondeau and Bourdon 2011; Negre-Salvayre et al. 2008). Mitochondrial dysfunction may, in turn, operate as both cause and consequence of this loop: impaired mitochondria generate increased ROS, which in turn accelerates metal, AGE, and ALE accumulation, further driving hallmark features of aging.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that interventions targeting any single component, such as reducing iron or copper accumulation, inhibiting AGE or ALE formation, can attenuate multiple hallmarks of aging and slow age-related decline progression (Panchin et al. 2024). The bidirectional nature of this feedback loop means that damage in one domain can propagate throughout the system, amplifying dysfunction across cellular compartments and tissues.

The Conglomerate Theory of Aging thus posits a robust, interconnected feedback loop in which bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrid complexes reinforce each other, driving the hallmarks of aging and accelerating the transition from molecular damage to tissue dysfunction and organismal decline. This framework provides a mechanistic basis for the observed amplification of aging phenotypes and their acceleration in late life.

9. Situating the Conglomerate Theory of Aging

The hallmarks of aging framework, as articulated by López-Otín et al. (2013; 2023), has provided a powerful lens through which to understand aging's multifaceted nature. These hallmarks are deeply interconnected, and interventions targeting one often impact others, underscoring the need for a unifying upstream driver that can explain their co-occurrence and mutual reinforcement (López-Otín et al. 2013; López-Otín et al. 2023). The Conglomerate Theory of Aging addresses this need by proposing that the bioaccumulation of metals, the formation of AGEs and ALEs, and their persistent hybrid complexes collectively constitute central, mutually reinforcing drivers of aging.

Recent advances in gene therapies and epigenetic reprogramming, such as Yamanaka factor-mediated partial reprogramming (Ocampo et al. 2016) and CRISPR-based interventions (Long et al. 2016), have demonstrated the potential to reset cellular identity and even reverse some hallmarks of aging in animal models. Nevertheless, the efficacy and durability of these approaches may be constrained by the persistent presence of bioaccumulated metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrids. While epigenetic reprogramming can rejuvenate chromatin structure and reset DNA methylation clocks, it does not directly address the underlying biochemical lesions and crosslinks formed by decades of metal-catalyzed oxidative damage, glycation, and lipoxidation. These persistent molecular scars can continue to disrupt nuclear architecture, impair DNA repair, and propagate cellular dysfunction even after reprogramming interventions (Vijg and Suh 2013). Similarly, gene therapies aimed at enhancing DNA repair or proteostasis may be limited if the cellular environment remains saturated with metal ions, AGEs, and ALEs that perpetuate oxidative stress and protein aggregation. The removal of senescent cells or the restoration of telomere length can be undermined by ongoing tissue stiffening and chronic inflammation driven by extracellular matrix crosslinking involving metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrids (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011). Unless these upstream sources of damage are neutralized, the benefits of even the most sophisticated gene and epigenetic interventions may prove transient or incomplete.

By positing that metal bioaccumulation, AGE and ALE formation, and the generation of metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid complexes collectively drive and amplify all hallmarks of aging, the Conglomerate Theory identifies causal processes that not only manifest during aging but also accelerate and unify the diverse hallmarks when experimentally manipulated (López-Otín et al. 2013; López-Otín et al. 2023). Metal-induced oxidative stress, AGE-mediated crosslinking, and ALE-driven lipid peroxidation can each independently promote genomic instability, telomere attrition, and loss of proteostasis. The persistent presence of metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrids further exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, and chronic inflammation. This model also integrates recent insights into the importance of altered mechanical properties and extracellular matrix remodeling, as these hybrids stiffen tissues and disrupt cell-cell communication, further propagating age-related decline (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011).

The Conglomerate Theory distinguishes itself from other upstream aging paradigms by the breadth and independence of its mechanistic reach. Metals, AGEs, and ALEs each fulfill the criteria for upstream drivers of aging, as each has been demonstrated to accelerate canonical hallmarks via distinct molecular mechanisms (Ott et al. 2014; Niedernhofer et al. 2018). Transition metals such as iron and copper catalyze Fenton reactions that generate reactive species, promoting DNA strand breaks, telomere attrition, and widespread protein oxidation (Valko et al. 2005). AGEs form stable crosslinks in long-lived proteins and extracellular matrix components, disrupt insulin and IGF-1 signaling, and activate chronic inflammatory cascades through RAGE-mediated pathways (Vlassara and Uribarri 2014). ALEs, generated through lipid peroxidation, form reactive adducts with proteins and nucleic acids, disrupt mitochondrial and membrane integrity, and act as potent inducers of inflammation and proteostatic collapse (Negre-Salvayre et al, 2010; Uchida, 2003). The convergence of these three damage modalities, culminating in the formation of persistent metal-AGE and metal-ALE hybrid complexes, further amplifies their pathogenic potential, as demonstrated by studies highlighting the synergistic effects of metal-catalyzed glycoxidation and lipoxidation in promoting tissue stiffening, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence (Rondeau and Bourdon 2011).

This overlapping and mutually reinforcing coverage of the hallmarks suggests that interventions targeting metals, AGEs, and ALEs together are uniquely positioned to disrupt the self-reinforcing cycles of molecular damage that characterize aging. The Conglomerate Theory thus offers a mechanistically unified explanation for the interconnectedness of the hallmarks and provides a compelling rationale for pursuing combinatorial therapeutic strategies with the potential to achieve unprecedented extension of mammalian healthspan and lifespan (López-Otín et al. 2023; Niedernhofer et al. 2018).

10. Comparison with Existing Theories of Aging

The theoretical landscape of aging has long been dominated by two irreconcilable paradigms: error accumulation models that invoke stochastic damage and programmed aging frameworks that emphasize genetic determinism (Jin 2010; Rattan 2006). These reductionist approaches have proven inadequate in explaining aging's complexity. The Conglomerate Theory represents a radical departure by establishing a unified system that systematically integrates the molecular drivers of aging.

Error theories have persistently attributed aging to the relentless accumulation of cellular damage. Harman's free radical hypothesis implicated reactive oxygen species as the primary culprit, while cross-linking theories focused on irreversible protein modifications (Harman 1956; Bjorksten 1968). The oxidative stress theory of aging later refined this argument to posits that aging results from the accumulation of oxidative damage to macromolecules caused by reactive oxygen species (Harman 1956; Gladyshev 2014). This theory dominated gerontology for decades and received substantial support from observations showing that oxidative damage increases with age and that antioxidant interventions can extend lifespan in some model organisms (Wickens 2001). However, mounting contradictory evidence has challenged its foundational assumptions. Increasing ROS production sometimes extends rather than shortens lifespan, and antioxidant supplementation has failed to demonstrate consistent benefits in clinical trials (Gladyshev 2014; Hekimi et al. 2011). These failures have led to the recognition that oxidative stress is often a consequence rather than a cause of aging, and that ROS serve essential signaling functions alongside their deleterious effects (Vina et al. 2008). Additional models have identified DNA mutations, protein aggregation, and declining repair mechanisms as central causes (Weinert and Timiras 2003; Medvedev 1990). Yet these frameworks fail to explain the species-specific patterns of aging or the profound modulation achieved through genetic and environmental interventions.

Programmed theories present an equally compelling yet incomplete narrative, proposing that aging unfolds according to genetically encoded biological programs analogous to developmental cascades (Weismann 1889; Skulachev 1999; Tower 2015). The dramatic post-reproductive decline in salmon and the synchronized aging of bamboo forests provide evidence for programmed mechanisms (Goldsmith 2014). However, these models overemphasize genetic determinism while inadequately addressing the stochastic and environmental factors that shape aging trajectories.

Recent scholarship has increasingly acknowledged the deficiencies of monolithic explanations, advocating instead for integrative approaches that acknowledge the complex interplay between genetic, metabolic, environmental, and stochastic influences (Rattan 2006; Vina et al. 2008). The hallmarks of aging framework exemplifies this evolution, cataloging interconnected biological processes that collectively drive aging (López-Otín et al. 2013). Nevertheless, even these sophisticated models lack the conceptual architecture to explain how diverse mechanisms converge to produce aging phenotypes.

The Conglomerate Theory reframes aging as the consequence of converging, context-dependent processes operating across multiple biological scales. Unlike the oxidative stress theory, which positions ROS as direct causative agents, the Conglomerate Theory recognizes incomplete neutralization of the whole gamut of reactive species as an upstream initiator that triggers the accumulation of metals, AGEs, and ALEs, which then become the primary drivers of aging through self-reinforcing feedback loops. Critically, it recognizes that different mechanisms may predominate in distinct contexts, tissues, or species, with their dynamic interactions generating remarkable diversity of aging trajectories.

11. Discussion

As articulated, the Conglomerate Theory establishes a transformative framework for understanding aging through the systematic integration of multiple RS-initiated processes. Thus, interventions targeting metal overload, glycation processes, lipoxidation pathways, or their convergent interactions may substantially ameliorate multiple aging hallmarks while extending lifespan, revealing unprecedented therapeutic opportunities.

11.1. Chelation Therapies

Chelation therapy extends beyond its traditional applications in heavy metal poisoning, offering significant therapeutic potential for aging intervention. Agents such as deferoxamine and deferasirox demonstrate efficacy in reducing iron-catalyzed oxidative damage while restoring mitochondrial function in neurodegenerative disease models (Kamalinia et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2016). Copper chelators show promise in attenuating amyloid pathology and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's models (Zhang et al. 2022). The central challenge lies in developing chelators that achieve therapeutic selectivity without disrupting metal pools required for physiological function.

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) emerges as an exceptionally powerful intervention. This naturally occurring compound possesses noteworthy metal-chelating properties, binding and neutralizing toxic metals including iron, copper, cadmium, lead, mercury, and arsenic. ALA supplementation enhances antioxidant defenses while dramatically reducing cellular metal burden, with both ALA and its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid, restoring redox balance and protecting against metal-induced cellular damage (Kurutas 2016). The dual antioxidant and chelating actions of ALA create a synergistic effect that simultaneously limits direct metal toxicity and reduces AGE formation by lowering oxidative stress and metal availability, thereby targeting multiple components of the aging feedback loop. Pulsed dosing schedules may prove safest in terms of reducing excess chelation.

11.2. Advanced Glycation End Product Interventions

Targeted AGE interventions represent another critical therapeutic avenue. Aminoguanidine inhibits advanced glycation, reducing AGE accumulation and protecting against vascular and renal complications in diabetic models. Small molecules such as ALT-711 demonstrate the ability to break existing AGE crosslinks and restore tissue elasticity in animal studies. Dietary interventions, including caloric restriction and reduced dietary AGE intake, consistently lower AGE burden while improving metabolic health in both animal and human studies.

L-carnosine and benfotiamine exemplify the therapeutic potential of naturally occurring AGE-targeting agents. L-carnosine functions as an antioxidant and anti-glycating agent by competing with protein amino groups to form Schiff bases, inhibiting AGE formation and protein crosslinking (Hipkiss 2005; McFarland and Holliday 1994). Its capacity to scavenge reactive carbonyl species while chelating transition metals creates a dual mechanism that reduces both reactive stress and glycation-related damage (Hipkiss 2005). Benfotiamine activates transketolase in the pentose phosphate pathway, diverting glycolytic intermediates away from pathways that generate methylglyoxal and other reactive AGE precursors (Brownlee 2001; Thornalley 2005). This metabolic rerouting dramatically reduces AGE formation and oxidative stress while inhibiting NF-κB activation, further disrupting the pro-inflammatory feedback loop driven by AGEs and metal-AGE hybrids (Giacco and Brownlee 2010).

11.3. Advanced Lipoxidation End Product Targeting

ALEs, generated through lipid peroxidation and reactive aldehydes, contribute to protein crosslinking, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation. Gamma-tocopherol demonstrates efficacy in trapping reactive nitrogen species and neutralizing lipid-derived electrophiles, thereby preventing ALE formation and limiting downstream toxic effects (Jiang et al. 2001). Consequently, gamma-tocopherol supplementation reduces lipid peroxidation markers, decreases inflammation, and protects against ALE-mediated cellular damage (Jiang et al. 2001). Researchers should consider testing mixed formulations of gamma-tocopherol and alpha-tocopherol given their complementarity, along with vitamin C given its ability to regenerate oxidized tocopherols. N-acetylcysteine and specific polyphenols are also under investigation for their capacity to scavenge lipid peroxidation products and mitigate ALE-related pathology. Anti-inflammatory interventions may provide additional leverage by disrupting the feedback loop perpetuated by metals, AGEs, and ALEs.

11.4. Reactive Species Interventions

The Conglomerate Theory's identification of RS quenching inefficiency as the initiating cascade necessitates targeted interventions that address diverse reactive species at their sources. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and glycine represent foundational approaches to this challenge. NAC serves as both a direct ROS scavenger and a precursor to glutathione, the body's most abundant endogenous antioxidant. Glycine supplementation provides a substrate for glutathione synthesis and delivers independent longevity benefits through methionine restriction mimicry and autophagy activation, as demonstrated by Miller et al. (2019) who documented its role in promoting autophagic processes. Kumar et al. (2022) demonstrated that combining NAC with glycine as GlyNAC extends the lifespan of elderly mice by 24% while correcting glutathione deficiency, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction across multiple organs. This combination directly addresses the age-related decline in glutathione synthesis identified by Sekhar et al. (2011), where elderly humans showed glutathione deficiency compared to young adults. Researchers should additionally consider evaluating selenium and vitamin C supplementation alongside GlyNAC. Selenium plays an essential role in glutathione peroxidase (GPx) function for peroxide neutralization, while vitamin C provides extracellular antioxidant defense that complements glutathione's intracellular specialization.

Lycopene is superlative in protection against singlet oxygen, demonstrating superior efficacy compared to other carotenoids in neutralizing this reactive species unaddressed by conventional antioxidants. Di Mascio et al. (1989) established that lycopene exhibits the highest physical quenching rate constant with singlet oxygen, exceeding that of beta-carotene by more than 2-fold and alpha-tocopherol by over 10-fold, while inhibiting lipid peroxidation cascades that generate ALE precursors. This multi-modal strategy targeting diverse reactive species limits the initial molecular insults that trigger the self-amplifying feedback loops central to the Conglomerate Theory of Aging.

11.5. Conclusions

The Conglomerate Theory proposes that aging's greatest vulnerability may lie in the gradual, self-amplifying accumulation of metals, AGEs, and ALEs that transforms into systemic tissue destruction. If validated, this recognition would call for multilateral, preventive strategies initiated before significant damage occurs to yield the greatest longevity dividends. The cultivation of sensitive biomarkers to monitor the burden of metals, AGEs, ALEs, and their hybrid complexes will prove essential for assessing health status and therapeutic efficacy in future investigations.

As research continues to unveil aging's intricate mechanisms, this framework provides a roadmap toward translational strategies that could transform our approach to extending human lifespan. As specific routes come closer into view, it appears that the question is not whether we can drive towards this healthier future but how quickly and easily we arrive.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of this work, including theory development, manuscript preparation, and analysis.

Funding

No funding was received to support this work.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Chidi Nwekwo, Near East University, for his expert contributions as a biomedical illustrator in creating the schematic diagram used to demonstrate our theory of aging. Dr. Nwekwo's skillful visual interpretation of the major concepts presented in this work greatly enhanced the clarity and accessibility of our theoretical framework.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186(2), 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtain, C. C.; Ali, F.; Volitakis, I.; Cherny, R. A.; Norton, R. S.; Beyreuther, K.; Barrow, C. J.; Masters, C. L.; Bush, A. I.; Barnham, K. J. Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta binds copper and zinc to generate an allosterically ordered membrane-penetrating structure containing superoxide dismutase-like subunits. The Journal of biological chemistry 2001, 276(23), 20466–20473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414(6865), 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, G.; Leonarduzzi, G.; Biasi, F.; Chiarpotto, E. Oxidative stress and cell signalling. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2004, 11(9), 1163–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondeau, P.; Bourdon, E. The glycation of albumin: structural and functional impacts. Biochimie 2011, 93(4), 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J. M. C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M. T. D. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12(10), 1161–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, L.; Youdim, M. B.; Riederer, P.; Connor, J. R.; Crichton, R. R. Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2004, 5(11), 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Jacobs, K.; Haucke, E.; Navarrete Santos, A.; Grune, T.; Simm, A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox Biology 2014, 2, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: A product and mediator of oxidative stress. Progress in Lipid Research 2003, 42(4), 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, G.; David, A.; Sayre, L. M. Model studies on the metal-catalyzed protein oxidation: structure of a possible His-Lys cross-link. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2004, 17(1), 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawczynski, W.; Shugar, D. Crosslinking of proteins to DNA with transition metal complexes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1987, 908(2), 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedernhofer, L. J.; Kirkland, J. L.; Ladiges, W. Molecular pathology endpoints useful for aging studies. Ageing Research Reviews 2018, 42, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M. T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2007, 39(1), 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, J. M.; Moonen, H. J.; van Schooten, F. J.; Hageman, G. J. Telomere length assessment: Biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2008, 44(3), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfeir, A.; Kosiyatrakul, S. T.; Hockemeyer, D.; MacRae, S. L.; Karlseder, J.; Schildkraut, C. L.; de Lange, T. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell 2009, 138(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wakai, T.; Shirai, Y.; Hatakeyama, K.; Hirano, S. Chronic oral exposure to inorganic arsenate interferes with methylation status of p16INK4a and RASSF1A and induces lung cancer in A/J mice. Toxicological Sciences 2006, 91(2), 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Islam, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. Z. Epigenetic Regulation in Chromium-, Nickel- and Cadmium-Induced Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2022, 14(23), 5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. B.; Vahter, M.; Concha, G.; Broberg, K. Low-level environmental cadmium exposure is associated with DNA hypomethylation in Argentinean women. Environmental health perspectives 2012, 120(6), 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V. N.; Li, J.; Fink, A. L. Metal-triggered structural transformations, aggregation, and fibrillation of human alpha-synuclein: A possible molecular link between Parkinson's disease and heavy metal exposure. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276(47), 44284–44296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. K.; Song, E.; Hipolito, V. E. B.; Sung, J. W.; Han, E. H.; Kaewsapsak, P.; Vasile, E.; Yoon, S.; Kim, H. S.; Park, J.; Langer, R.; Yun, S. H.; Ferrante, A. W., Jr. Iron overload inhibits late stage autophagic flux leading to insulin resistance. EMBO Reports 2019, 20(10), e47911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. F.; Zhao, Y. J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, F. Heavy Metals Toxicity: Mechanism, Health Effects, and Therapeutic Interventions. MedComm 2025, 6(9), e70241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, D. J.; Bryder, D.; Zahn, J. M.; Ahlenius, H.; Sonu, R.; Wagers, A. J.; Weissman, I. L. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102(26), 9194–9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, S.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J. Calcium signaling is involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis via induction of reactive oxygen species and activation of MAPK/mTOR network. PLoS One 2011, 6(4), e19052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chi, H.; Zhu, W.; Yang, G.; Song, J.; Mo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xu, F.; Yang, J.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Cadmium induces renal inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through ROS/MAPK/NF-κB pathway in vitro and in vivo. Archives of toxicology 2021, 95(11), 3497–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chargui, A.; Zekri, S.; Jacquillet, G.; Rubera, I.; Ilie, M.; Belaid, A.; Duranton, C.; Tauc, M.; Hofman, P.; Poujeol, P.; El May, M. V.; Mograbi, B. Cadmium-induced autophagy in rat kidney: An early biomarker of subtoxic exposure. Toxicological Sciences 2011, 121(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Hou, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Mechanism of autophagy mediated by IGF-1 signaling pathway in the neurotoxicity of lead in pubertal rats. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 251, 114557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Y.; Pang, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, T. Toxic and essential metals: metabolic interactions with the gut microbiota and health implications. Frontiers in nutrition 2024, 11, 1448388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, S. W.; Choi, B. Y.; Son, S. Y.; Lee, J. H.; Min, J. Y.; Min, K. B. Lead and cadmium exposure was associated with faster epigenetic aging in a representative sample of adults aged 50 and older in the United States. Chemosphere 2025, 374, 144194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G. J. Risks of copper and iron toxicity during aging in humans. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2010, 23(2), 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, B. B.; Hopkins, S. E.; Doherty, J. A.; O'Brien, D. M.; Thummel, K. E.; Adams, A.; Wilder, J. Metal mixtures and DNA-methylation measures of biological aging in American Indian populations. Environment International 2023, 176, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A. N.; Liu, G. Y.; Zhang, S. Z.; Dai, W. W. Sheng li xue bao. Acta physiologica Sinica] 2024, 76(3), 418–428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maher, P. Potentiation of glutathione loss and nerve cell death by the transition metals iron and copper: Implications for age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 115, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.; Beilin, L. Advanced glycation end-products: A review. Diabetologia 2001, 44(2), 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornalley, P. J. Dicarbonyl intermediates in the maillard reaction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005, 1043, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistoli, G.; De Maddis, D.; Cipak, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Advanced glycoxidation and lipoxidation end products (AGEs and ALEs): an overview of their mechanisms of formation. Free Radical Research 2013, 47(sup1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2013.815348.

- Tamura, Y.; Horiuchi, S.; Hara, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Kinoshita, S.; Arai, Y.; Ito, H. β-Cell telomere attrition in diabetes: Inverse correlation between HbA1c and telomere length. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2014, 99(8), 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cao, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wen, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M. The association between telomere length and diabetes mellitus: Accumulated evidence from observational studies. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2024, 110(1), e177–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galligan, J. J.; Wepy, J. A.; Streeter, M. D.; Kingsley, P. J.; Mitchener, M. M.; Wauchope, O. R.; Marnett, L. J. Methylglyoxal-derived posttranslational arginine modifications are abundant histone marks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115(37), 9228–9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, E. K.; Lee, S. W.; Aaronson, S. A. Role of progerin-induced telomere dysfunction in HGPS premature cellular senescence. Journal of Cell Science 2010, 123(15), 2605–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, D. R.; Monnier, V. M.; Nagaraj, R. H. Role of glycation in diabetic complications. Diabetes 1992, 41(12), 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalfó, E.; Portero-Otín, M.; Ayala, V.; Martínez, A.; Pamplona, R.; Ferrer, I. Evidence of oxidative stress in the neocortex in incidental Lewy body disease. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2005, 64(9), 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassara, H.; Uribarri, J. Advanced glycation end products (AGE) and diabetes: Cause, effect, or both? Current Diabetes Reports 2014, 14(1), 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; He, J. C.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Zheng, F.; Striker, G. E.; Vlassara, H. Oral advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) promote insulin resistance and diabetes by depleting the antioxidant defenses AGE receptor-1 and sirtuin 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109(39), 15888–15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudina, S.; Sena, S.; Theobald, H.; Sheng, X.; Wright, J. J.; Hu, X. X.; Abel, E. D. Mitochondrial energetics in the heart in obesity-related diabetes: direct evidence for increased uncoupled respiration and activation of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 2007, 56(10), 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nulton-Persson, A. C.; Szweda, L. I. Modulation of mitochondrial function by hydrogen peroxide. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276(26), 23357–23361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.; Nakamura, K.; Matsui, T.; Ueda, S.; Fukami, K.; Okuda, S. Agents that block advanced glycation end product (AGE)-RAGE (receptor for AGEs)-oxidative stress system: a novel therapeutic strategy for diabetic vascular complications. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2008, 17(7), 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerman, I.; Rossi, D. J. Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic stem cell aging. Experimental Cell Research 2014, 329(2), 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snedeker, J. G.; Gautieri, A. The role of collagen crosslinks in ageing and diabetes - the good, the bad, and the ugly. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 2014, 4(3), 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Shi, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, L. Validation of vanillic acid as a multi-targeted agent for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 144, 112282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandidos, D. A.; Zoumpourlis, V.; Khoury, G.; Goutas, N.; Papadimitriou, K.; Tzimagiorgis, G.; Koukourakis, M. I. AGE-rich diet and gut microbiota interactions. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2023, 51(3), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Fu, L. Dietary advanced glycation end-products promote food allergy by disrupting intestinal barrier and enhancing Th2 immunity. Nature communications 2025, 16(1), 4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajithlal, G. B.; Chithra, P.; Chandrakasan, G. Effect of curcumin on the advanced glycation and cross-linking of collagen in diabetic rats. Biochemical Pharmacology 1998, 56(12), 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Liu, M.; Eaton, J. W. Transition metals bind to glycated proteins forming redox active "glycochelates": implications for the pathogenesis of certain diabetic complications. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1998, 250(2), 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvinov, D.; Mahini, H.; Garelnabi, M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory role of paraoxonase 1: implication in arteriosclerosis diseases. North American journal of medical sciences 2012, 4(11), 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglielli, L.; Friedlich, A. L.; Setchell, K. D.; Nagano, S.; Opazo, C.; Cherny, R. A.; Barnham, K. J.; Wade, J. D.; Melov, S.; Kovacs, D. M.; Bush, A. I. Alzheimer disease beta-amyloid activity mimics cholesterol oxidase. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2005, 115(9), 2556–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamplona, R. Membrane phospholipids, lipoxidative damage and molecular integrity: A causal role in aging and longevity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2008, 1777(10), 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grune, T.; Reinheckel, T.; Davies, K. J. Degradation of oxidized proteins in mammalian cells. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 1997, 11(7), 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M. F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]