Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Enhance the interpretability of detected intrusions by formalizing relationships between threats and mitigation strategies.

- Improve decision-making in IDS by providing a knowledge-driven framework to recommend suitable countermeasures.

- Facilitate seamless integration of security policies within AV systems, ensuring adaptive protection mechanisms.

2. Related Work

3. Intrusion in Autonomous Vehicle: Classification and Challenges

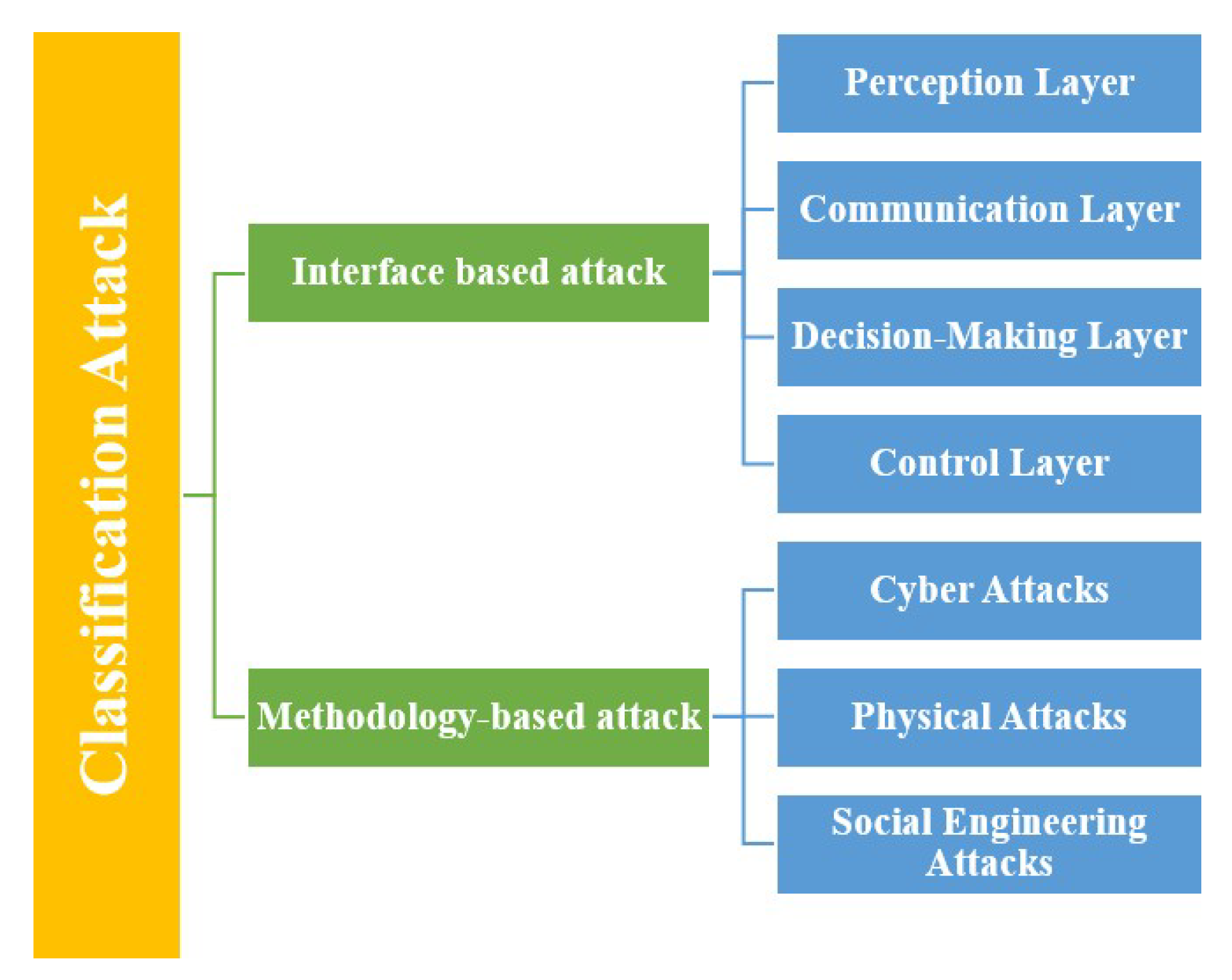

3.1. Classification of Attack

3.1.1. Interface Based Attack

- Attacks on the perception layer (sensor level): Sensors have a crucial role to play in detecting the vehicle's environment. GPS spoofing, for example, involves the injection of falsified GPS signals, which mislead the navigation system and direct the vehicle to incorrect destinations. LiDAR and camera spoofing involves manipulating the data collected by these sensors to create false objects or conceal real obstacles, thereby disrupting the vehicle's decision-making process [29]. Finally, adversarial attacks on AI modify the input data used by artificial intelligence models, which can mislead the vehicle and lead to incorrect driving decisions [30].

- Attacks on the communication layer: AVs constantly interact with other vehicles (V2V) and external infrastructures (V2I). Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks intercept these communications, enabling attackers to modify or falsify them. On the other hand, Denial of Service (DoS/DDoS) attacks aim to saturate communication networks, disrupting essential services such as navigation, communication with other vehicles or security alerts [31]. On the other hand, false message injection is another potentially devastating attack, where falsified messages are sent into V2V or V2I channels, distorting coordination and decision-making between vehicles and the infrastructure.

- Attacks on the decision-making layer: AVs depend on artificial intelligence systems to make decisions in real-time. Data poisoning involves injecting malicious data into learning models, distorting vehicle behavior, and increasing the risk of erroneous decisions [32]. In addition, manipulation of reinforcement learning involves altering the rewards given to the AI system to influence its learning process, which disrupts the vehicle's decisions and may lead it to adopt unsafe behavior.

- Attacks on the control layer: These attacks aim to directly modify the vehicle's actions. Braking override prevents the vehicle from stopping, even in situations where stopping is necessary to avoid an accident [33]. Acceleration manipulation forces the vehicle to accelerate unexpectedly, compromising the safety of passengers and other road users.

3.1.2. Methodology-Based Attack

- Cyber-attacks: refer to attempts to intrude into a vehicle's electronic systems, usually carried out remotely by malicious attackers [34]. One of the most common forms is the exploitation of vulnerabilities in vehicle systems via wireless connections. Using these exploits, attackers can take control of vital vehicle systems, as has been observed in vehicle hacking incidents, particularly those involving Tesla cars. Another form of cyber attack involves malware and ransomware, which are used to infect vehicle systems. This can either disable the vehicle or compromise sensitive data, forcing the attacker to demand a ransom to unlock access or prevent the disclosure of private information [35]. In addition, attacks using backdoors or logic bombs can be introduced during vehicle software updates. Backdoors enable attackers to gain remote access to the vehicle's systems, while logic bombs can be activated at a specific time to disrupt its operation.

- Physical attacks are a direct impact on the vehicle's hardware components, particularly sensors and communication systems. For example, the manipulation of sensors can include actions such as covering, blocking or degrading them, preventing the vehicle from correctly perceiving its environment [36]. This can lead to errors of judgment or failures in autonomous driving systems, compromising vehicle safety.

- Social engineering attacks: also called insider threats, exploit the manipulation of individuals or loopholes in the supply chain to compromise a vehicle's systems. Phishing techniques and fraudulent software updates are commonly used to trick users or employees into installing malware on vehicle systems [37]. These attacks are often disguised as legitimate software updates but contain malicious elements that enable the attacker to take control of the system.

3.2. Challenges Related to the Safety of Autonomous Vehicles

3.2.1. Intrusions Due to System Vulnerabilities

- Software-based vulnerabilities: Unpatched software, unsecured third-party applications, and malicious firmware updates can allow attackers to exploit the system.

- Communication vulnerabilities: AVs communicate via Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) protocols, which are susceptible to eavesdropping, spoofing, and man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Hardware-based vulnerabilities: Malfunctioning electronic control units (ECUs), sensor failures, or unauthorized physical access can introduce security risks.

3.2.2. Intrusions Due to External Actors

- Environmental factors: Sensor manipulation (e.g., LiDAR jamming), GPS spoofing, and adversarial road signs can mislead AV decision-making.

- Malicious drivers: Attackers inside nearby vehicles may inject false information into AV networks to mislead detection systems.

3.2.3. Intrusions Due to Security Policy Violations

- Confidentiality attacks: Data breaches exposing AV sensor or user data.

- Integrity attacks: Tampering with AV decision-making by injecting false control commands.

- Availability attacks: Denial-of-Service (DoS) or jamming attacks that disrupt communication.

4. Security Requirements for Intrusion Detection in Autonomous Vehicle

4.1. Authentication & Access Control

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA): enhances security by requiring multiple authentication factors (e.g. passwords, biometrics, and security tokens) to access vehicle systems.

- Role-based access control (RBAC): implementation of strict authorization policies based on user roles (e.g. driver, manufacturer, service technician) to limit system access and minimize security risks.

4.2. Secure Communication

- End-to-end encryption (E2EE): Use secure cryptographic protocols (e.g. TLS/SSL) to encrypt V2X communications, preventing eavesdropping and data tampering.

- Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS): Deploy network security solutions to detect and block malicious traffic in real-time, mitigating the risk of network-based attacks such as Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) and Denial-of-Service (DoS).

- Blockchain for V2X security: Leveraging decentralized authentication to verify the legitimacy of messages exchanged between vehicles, infrastructure, and cloud services, reducing the risk of injecting false messages.

4.3. AI-Based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

- Anomaly-based detection: using machine learning algorithms to monitor deviations from normal operations in network communications, sensor inputs, and system behaviors, thus identifying potential attacks in real-time [45].

- Adversarial ML defense techniques: implementing robust AI models that resist adversarial attacks by improving training methods, using adversarial learning, and integrating model-checking techniques to improve resilience [46].

4.4. Secure Software & Hardware

- Secure booting and code signing: implementation of cryptographic validation mechanisms to ensure that only trusted and verified software is executed on vehicle components, preventing unauthorized firmware updates or malware injections.

- Hardware Security Modules (HSM): use of dedicated security chips to securely store and manage cryptographic keys, preventing unauthorized access to encryption keys and protecting sensitive vehicle data.

4.5. Resilience & Recovery Mechanisms

- Safety mechanisms: design autonomous systems to enter a safe operating mode if a cyber attack is detected, enabling the vehicle to stop or continue operating with minimal risk to passengers and the environment.

- Redundant systems: integrate backup sensors, isolated control units, and redundant communication networks to maintain essential functionality in the event of system failure or security breaches.

5. Methodology and Proposed Ontology

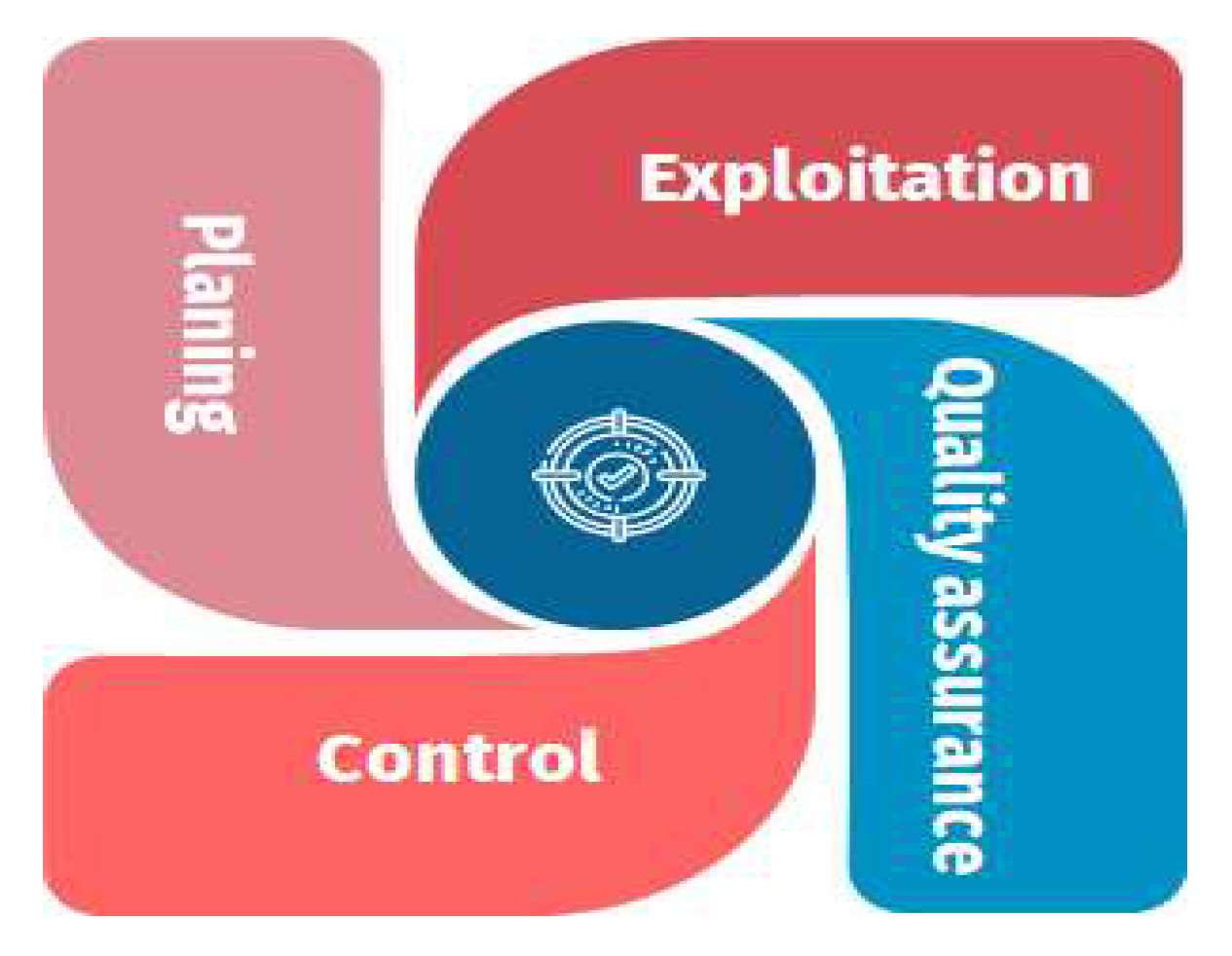

5.1. Procedures for Ontology Creation

- Planning involves defining the problem and outlining the tasks needed to address it. This includes detecting security threats in autonomous vehicles, identifying mitigation techniques, assessing their impact, and structuring these tasks by categorizing relevant elements (e.g., vehicle communication, attack types, and mitigation strategies). Additionally, this step defines actors and their attributes, mapping their interactions within the system.

- Control ensures the ontology's execution is accurate, error-free, and effectively resolves the identified security issues.

- Quality Assurance follows, focusing on testing the ontology and validating the interactions between different entities to confirm its reliability.

- Exploitation is the final stage, where the ontology is deployed in real-world scenarios after extensive testing. Figure 3, illustrates this ontology-based process:

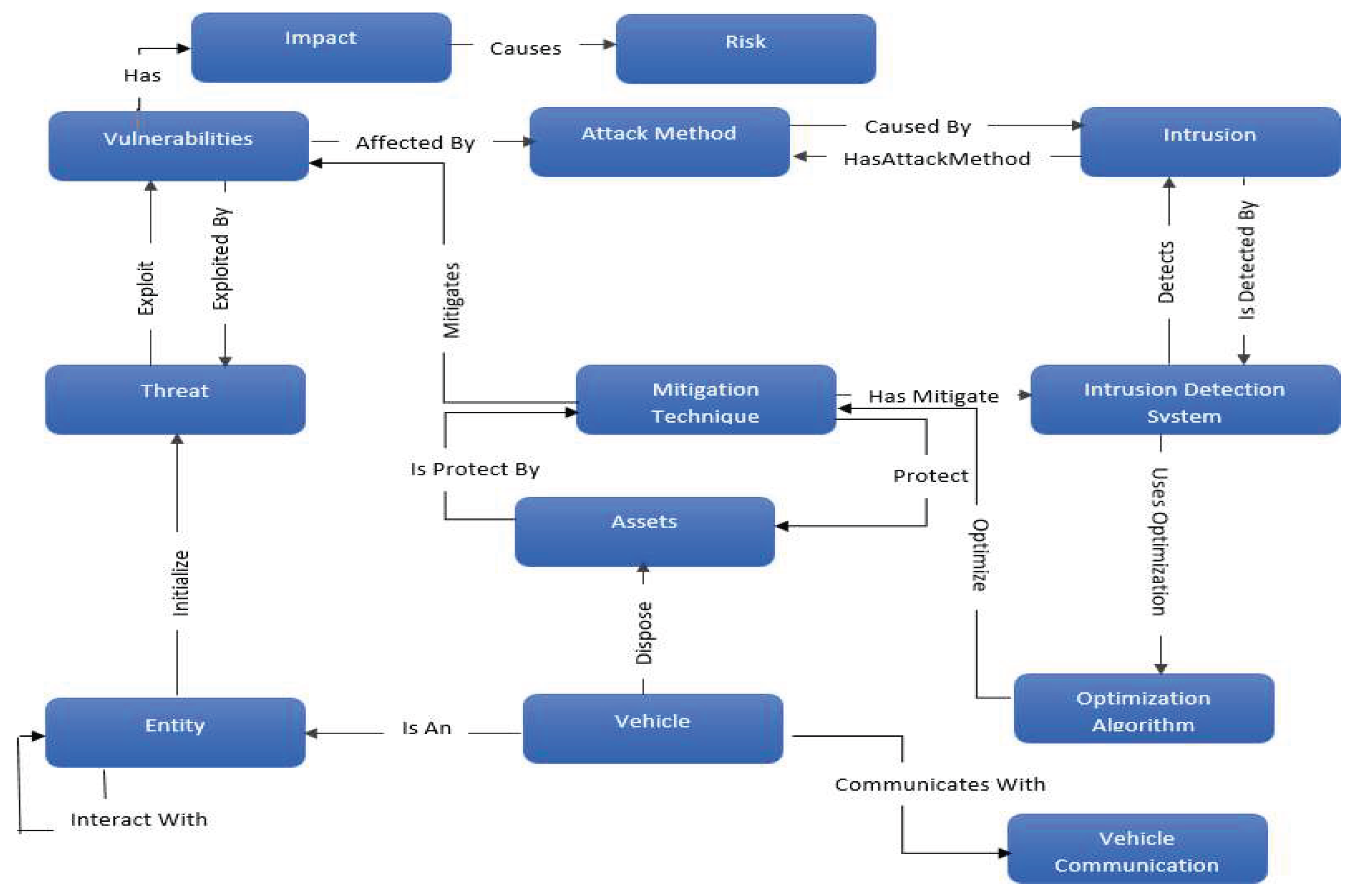

5.2. Proposed Ontology

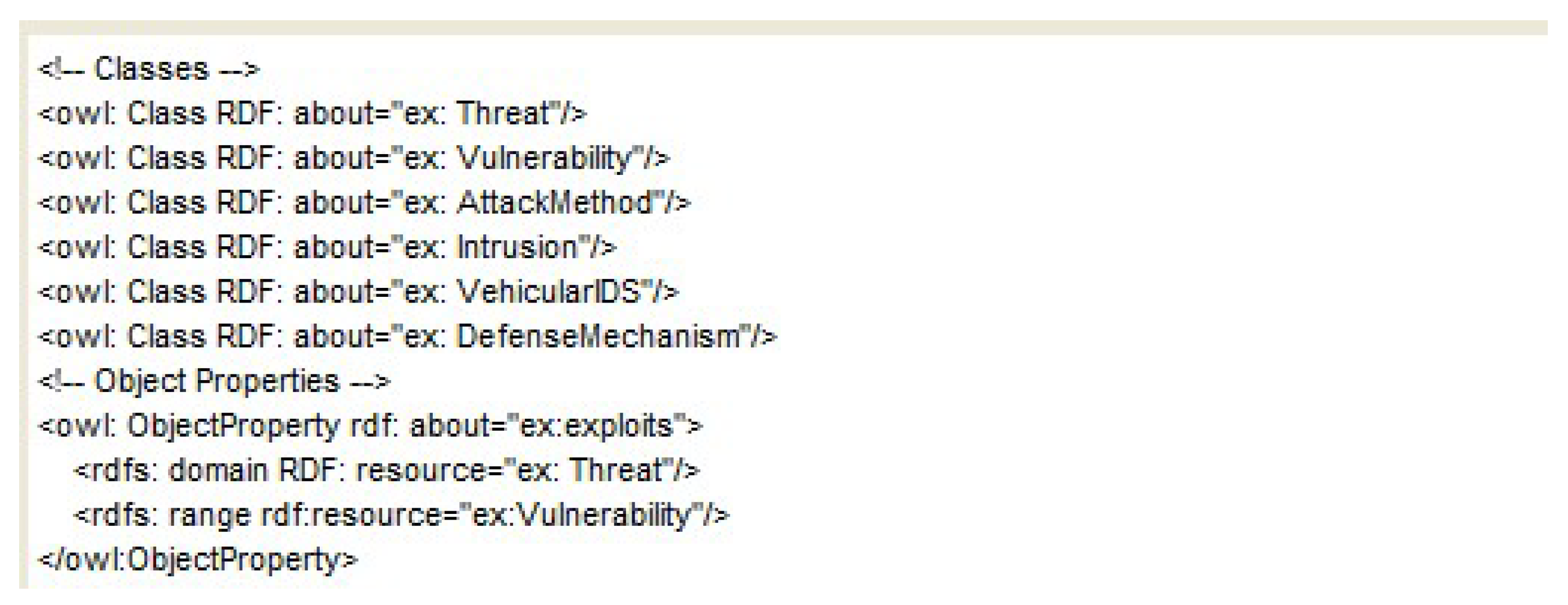

5.3. Ontology-Based to Secure Autonomous Vehicles

5.3.1. Specification

- The knowledge domain: the ontology we have just constructed is part of the autonomous vehicle security domain. It can draw its concepts from the domain of computer security.

- The objective: the main objective of incorporating ontologies in an autonomous vehicle is to conceal the heterogeneity concerning the security to guarantee better interoperability of the security policies to decrease the severity of the risk using the knowledge domain of the ontology.

- Users: This aspect provides the set of users to exploit the ontology. In our case, the ontology users are the autonomous vehicles that need to exploit the ontologies to maintain the required goal.

- Information sources: the information sources on which we based ourselves to arrive at the construction of the application ontology are technical documents of autonomous vehicle security.

- The scope of the ontology: This aspect consists in determining a priori the list of terms of the ontology (the most important ones); among these terms, we can mention: Vehicle, Countermeasure, Threat, etc.

5.3.2. Conceptualization

- A concept C₁ is a subclass of concept C₂ if and only if every instance of C₁ is also an instance of C₂. For example, a Vehicle is a subclass of the class Entity.

- A Disjoint Decomposition of concept C is a set of subclasses of C that do not cover C entirely and do not share any common instances. For example, the concepts Low, Moderate, and Critical form a Disjoint Decomposition of the concept of Security Level.

- An Exhaustive Decomposition of concept C is a set of subclasses of C that together cover C completely and may share common instances.

- A Partition of concept C is a set of subclasses of C that together cover C entirely and have no overlapping instances. For instance, the concepts Proactive, Detective, and Corrective form a Partition of concept types.

5.3.3. Formalization

- TBox defines the concepts and roles of an ontology using descriptive logic constructs. Whereas an ABox describes individuals, a TBox formalizes the conceptual structure of the domain by establishing general relationships between concepts. For example, the statement "A vehicle has at least one asset" can be expressed in description logic as:

- Vehicle1 : Vehicle

- Asset1 : Asset

- Vehicle1 ownsAsset Asset1

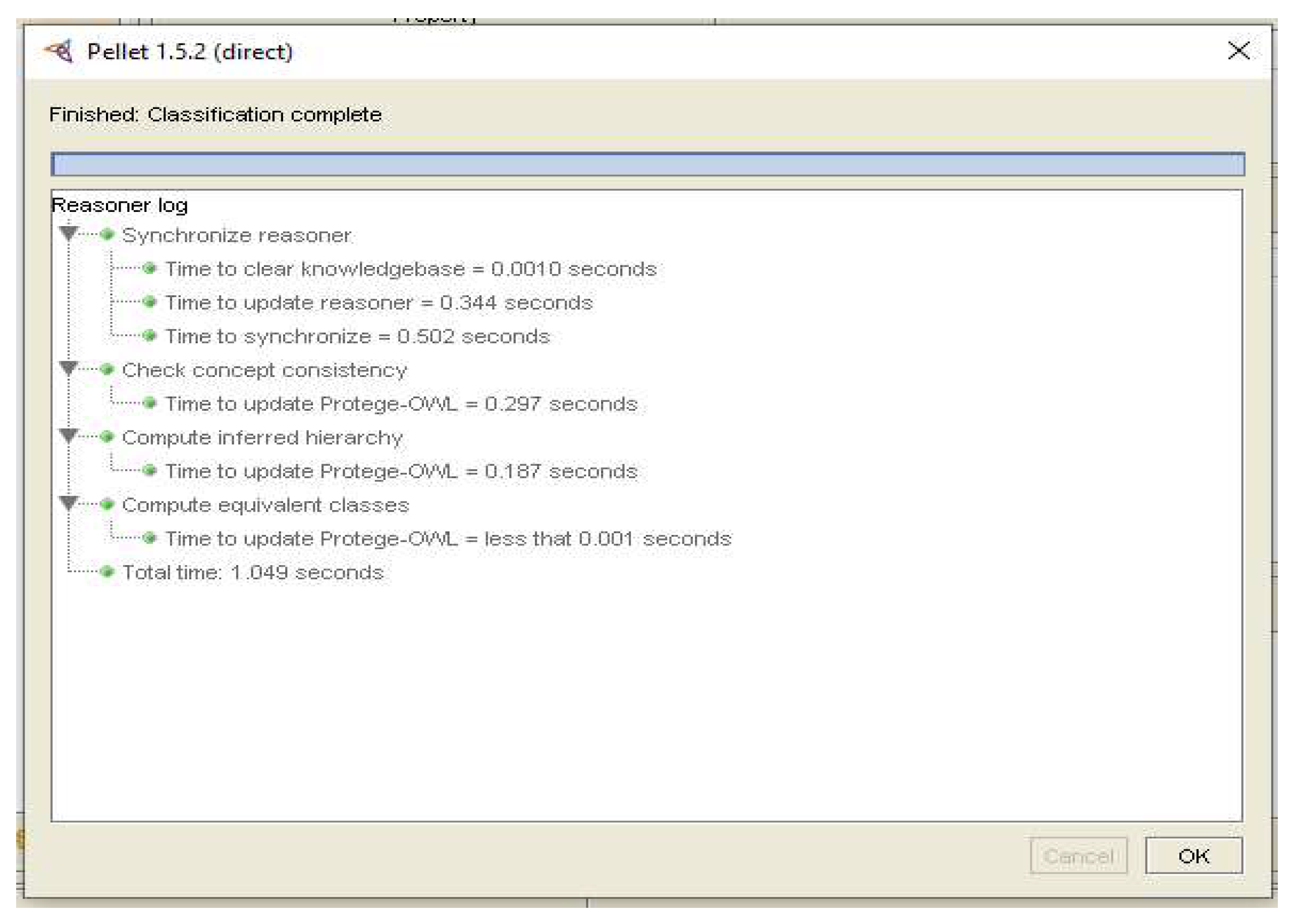

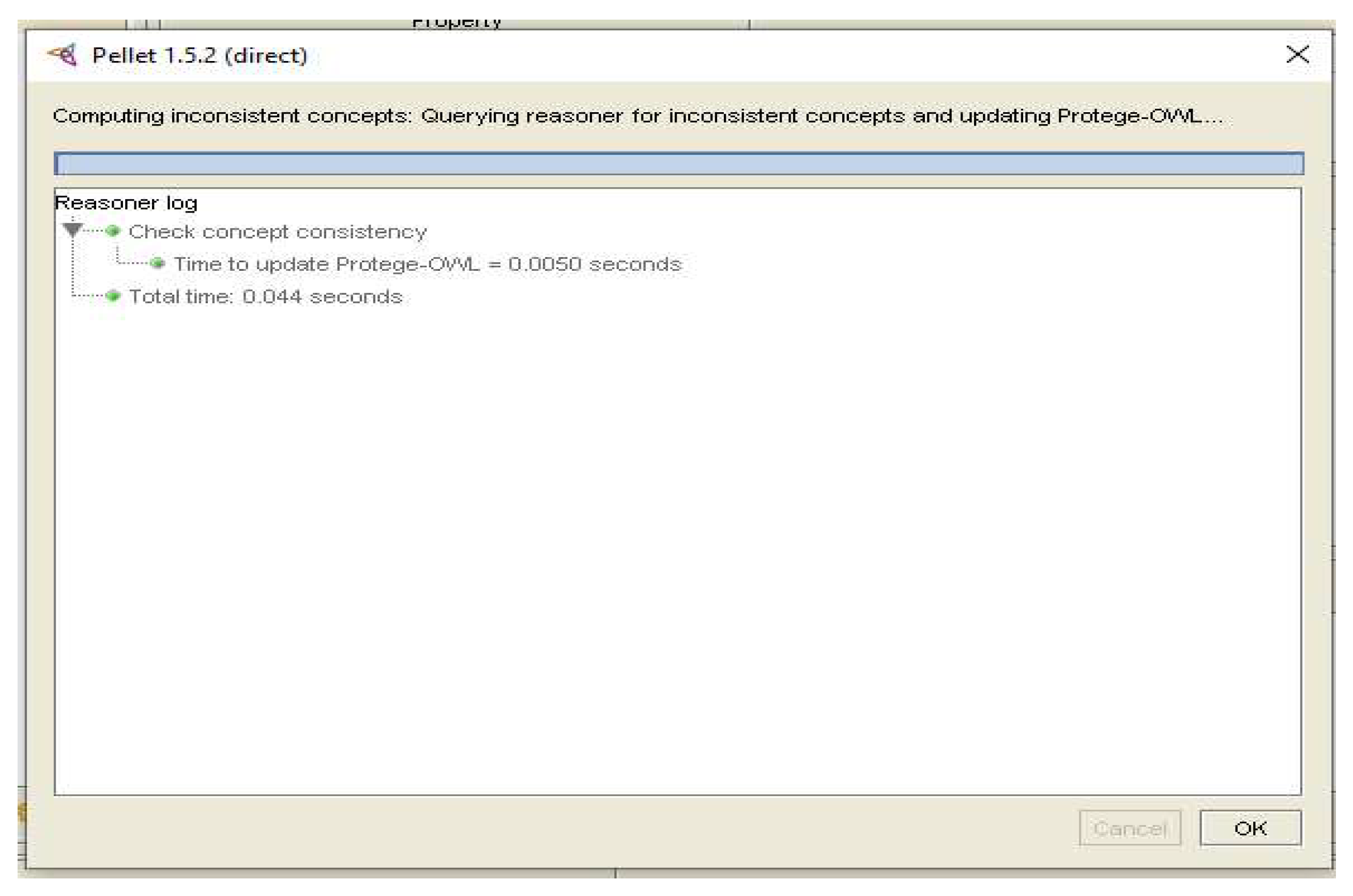

5.3.4. Implementation and Test

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

References

- W. Wu et al. A Survey of Intrusion Detection for In-Vehicle Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Cho et K. G. Shin. Viden: Attacker identification on in-vehicle networks. in Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2017, p. 1109-1123. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. Japkowicz, et S. Leblanc. Frequency-based anomaly detection for the automotive CAN bus. in 2015 World Congress on Industrial Control Systems Security (WCICSS), déc. 2015, p. 45-49. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Song, H. R. H. M. Song, H. R. Kim, et H. K. Kim. Intrusion detection system based on the analysis of time intervals of CAN messages for in-vehicle network. 2016 Int. Conf. Inf. Netw. ICOIN, 2016; 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Manale et T. Mazri. Intrusion detection method for GPS based on deep learning for autonomous vehicle. Int. J. Electron. Secur. Digit. Forensics 2022, 14, 37-52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Bandeira, I. I. J. Bandeira, I. I. Bittencourt, P. Espinheira, et S. Isotani. FOCA: A Methodology for Ontology Evaluation. arXiv, arXiv:1612.03353. [CrossRef]

- F. Neuhaus. What is an Ontology? arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.09171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Filman et T. Linden. SafeBots: A paradigm for software security controls. Proc. New Secur. Paradig. Workshop, 1294; 51. [CrossRef]

- G. Denker, L. G. Denker, L. Kagal, T. Finin, M. Paolucci, et K. Sycara. Security for DAML Web Services: Annotation and Matchmaking. in The Semantic Web - ISWC 2003, D. Fensel, K. Sycara, et J. Mylopoulos, Éd., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2003, p. 335-350. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P. Sandilands, et L. Van Ekert. An ontology for network security attacks. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinforma. 2004, 3285, 317-323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kannan, A. Thangavelu, et R. Kalivaradhan. An Intelligent Driver Assistance System (I-DAS) for Vehicle Safety Modelling using Ontology Approach. Int. J. UbiComp 2010, 1, 15-29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Stocker, M. M. Stocker, M. Rönkkö, et M. Kolehmainen. Making sense of sensor data using ontology: A discussion for road vehicle classification ».

- S. Fernandez, R. Hadfi, T. Ito, I. Marsa-Maestre, et J. R. Velasco. Ontology-Based Architecture for Intelligent Transportation Systems Using a Traffic Sensor Network. Sensors 2016, 16, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Xiong, V. V. Z. Xiong, V. V. Dixit, et S. Travis Waller. The development of an ontology for driving context modelling and reasoning. IEEE Conf. Intell. Transp. Syst. Proc. ITSC, 18. [CrossRef]

- E. Pollard, P. E. Pollard, P. Morignot, et F. Nashashibi. An ontology-based model to determine the automation level of an automated vehicle for co-driving. in Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Fusion, juill. 2013, p. 596-603. Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6641334?

- V. B. Robinson et D. S. Mackay. Semantic modeling for the integration of geographic information and regional hydroecological simulation management. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 1995, 19, 321-339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- « An ontology based approach to traffic management in urban areas | Request PDF ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.researchgate. 2809.

- J.-P. Calbimonte. Ontology-based access to sensor data streams. PhD Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Yu. Zhao, et W. Liu. A Method for Mapping Sensor Data to SSN Ontology. Int. J. U- E- Serv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 303-316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliverstov et R. J., F. Rossetti. An ontological approach to spatio-temporal information modelling in transportation. 2015 IEEE 1st Int. Smart Cities Conf. ISC2 2015. [CrossRef]

- Baccigalupo et, E. Plaza. Poolcasting: A Social Web Radio Architecture for Group Customisation. in Third International Conference on Automated Production of Cross Media Content for Multi-Channel Distribution (AXMEDIS’07), nov. 2007, p. 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Alaya, L. Sellami, et P. Lorenz. An ontological approach to the detection of anomalies in vehicular ad hoc networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024, 156, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- « A dataset for cyber threat intelligence modeling of connected autonomous vehicles | Scientific Data ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.nature. 4159.

- « OAIDS: An Ontology-Based Framework for Building an Intelligent Urban Road Traffic Automatic Incident Detection System | SpringerLink ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10. 1007.

- H. Sun, J. H. Sun, J. Wang, J. Weng, et W. Tan. KG-ID: Knowledge Graph-Based Intrusion Detection on In-Vehicle Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, N. Karie, R. Ryan, et I. Murray, Towards an Ontological Digital Forensic Investigation Framework for Autonomous Vehicles. 2024, p. 204. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Abdallah, A. Aloqaily, et H. Fayez. Identifying Intrusion Attempts on Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: A Survey. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 220, 307-314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Loukas, E. Karapistoli, E. Panaousis, P. Sarigiannidis, A. Bezemskij, et T. Vuong. A taxonomy and survey of cyber-physical intrusion detection approaches for vehicles. Ad Hoc Netw. 2019, 84, 124-147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, T. Liu, T. Shu, et D. Nguyen. Spoofing Detection for LiDAR in Autonomous Vehicles: A Physical-Layer Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 20673-20689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- « Cybersecurity of Autonomous Vehicles: A Systematic Literature Review of Adversarial Attacks and Defense Models | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://ieeexplore.ieee. 1009.

- Praseed et P., S. Thilagam. DDoS Attacks at the Application Layer: Challenges and Research Perspectives for Safeguarding Web Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 661-685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Madhavi, N. C. Santhosh, S. Rajkumar, et R. Praveen. Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets-based VIKOR and TOPSIS-based multi-criteria decision-making model for mitigating resource deletion attacks in WSNs. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 44, 9441-9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Hataba, A. Sherif, M. Mahmoud, M. Abdallah, et W. Alasmary. Security and Privacy Issues in Autonomous Vehicles: A Layer-Based Survey. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2022, 3, 811-829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. G. B. Stottelaar. Practical cyber-attacks on autonomous vehicles ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://essay.utwente. 6676.

- « Towards a Severity Assessment Method for Potential Cyber Attacks to Connected and Autonomous Vehicles - He - 2020 - Journal of Advanced Transportation - Wiley Online Library ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1155.

- « Physical Invariant Based Attack Detection for Autonomous Vehicles: Survey, Vision, and Challenges | IEEE Conference Publication | IEEE Xplore ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://ieeexplore.ieee. 9499.

- V. L. L. Thing et J. Wu. Autonomous Vehicle Security: A Taxonomy of Attacks and Defences. Proc. - 2016 IEEE Int. Conf. Internet Things IEEE Green Comput. Commun. IEEE Cyber Phys. Soc. Comput. IEEE Smart Data IThings-GreenCom-CPSCom-Smart Data 2017, 2016, 164-170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- « Intrusion Threats and Security Solutions for Autonomous Vehicle Networks | IEEE Conference Publication | IEEE Xplore ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://ieeexplore.ieee. 8308.

- « Potential Cyberattacks on Automated Vehicles | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://ieeexplore.ieee. 6899.

- P. Golle, D. P. Golle, D. Greene, et J. Staddon. Detecting and correcting malicious data in VANETs. in Proceedings of the 1st ACM international workshop on Vehicular ad hoc networks, in VANET ’04. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, oct. 2004, p. 29-37. [CrossRef]

- « Vehicle Behavior Analysis to Enhance Security in VANETs | Semantic Scholar ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://www.semanticscholar. 3980.

- M. Ghosh, A. M. Ghosh, A. Varghese, A. A. Kherani, et A. Gupta. Distributed Misbehavior Detection in VANETs. in 2009 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, avr. 2009, p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- S. Lingras et A. Basu. The Security of Autonomous Vehicle Software and its National Security Implications. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025; 1. [CrossRef]

- « AI-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for In-Vehicle Networks: A Survey | ACM Computing Surveys ». Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://dl.acm.org/doi/full/10. 1145.

- H. Lundberg, Increasing the Trustworthiness ofAI-based In-Vehicle IDS usingeXplainable AI. 2022. Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://urn.kb.se/resolve? 4522.

- P. Sharma, D. P. Sharma, D. Austin, et H. Liu. Attacks on Machine Learning: Adversarial Examples in Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. in 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), nov. 2019, p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- F. Khalid et S. R. Hasan. Chapter 9 - Hardware security of autonomous vehicles. in <i>Handbook of Power Electronics in Autonomous and Electric Vehicles</i>, M. H. F. Khalid et S. R. Hasan. Chapter 9 - Hardware security of autonomous vehicles. in Handbook of Power Electronics in Autonomous and Electric Vehicles, M. H. Rashid, Éd., Academic Press, 2024, p. 125-138. [CrossRef]

- K. Sjoberg. Resilience and Recovery [Connected and Autonomous Vehicles]. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2021, 16, 93-96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Roche, TOTh 2010, Terminology & Ontology: Theories and applications, vol. 2010. in TOTh 2010, Terminology & Ontology: Theories and applications, vol. 2010. Annecy, France: Institut Porphyre, Savoir et Connaissance, 2010. Consulté le: 22 mars 2025. [En ligne]. Disponible sur: https://hal. 0135.

- K. Vanitha, M. S. K. Vanitha, M. S. Venkatesh, K. R. -, et S. V. Lakshmi. The Development Process of the Semantic Web and Web Ontology. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2011; 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Poyyamozhi, R. S. Poyyamozhi, R. Yang, V. Krovi, R. Rai, B. Smith, et D. Kasmier. Ontology Foundation for the Self-Driving Software Stack. 8 février 2025, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY: 5129199. [CrossRef]

| Security Technique | Security Measure | Security Requirement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidentiality | Integrity | Availability | ||

| Authentication & Access Control | Multi-factor authentication (MFA) |

* | * | * |

| Multi-factor authentication (MFA) |

* | * | * | |

| Secure Communication | End-to-end encryption (E2EE) |

* | * | |

| Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS) |

* | * | ||

| Blockchain for V2X security |

* | * | ||

| AI-Based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) | Anomaly-based detection |

* | * | |

| Adversarial ML defense techniques |

* | * | ||

| Secure Software & Hardware | Secure booting and code signing |

* | * | |

| Hardware Security Modules (HSM) |

* | * | ||

| Resilience & Recovery Mechanisms |

Safety mechanisms | * | * | |

| Redundant systems | * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).