Submitted:

27 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Participants

Measures

Hetero-Assessments with the Parent

Developmental Battery

Standardized Tests

Receptive Vocabulary

Expressive Vocabulary

Oral Comprehension

Articulation Skills

Procedure

Overview of Statistical Analysis

Results

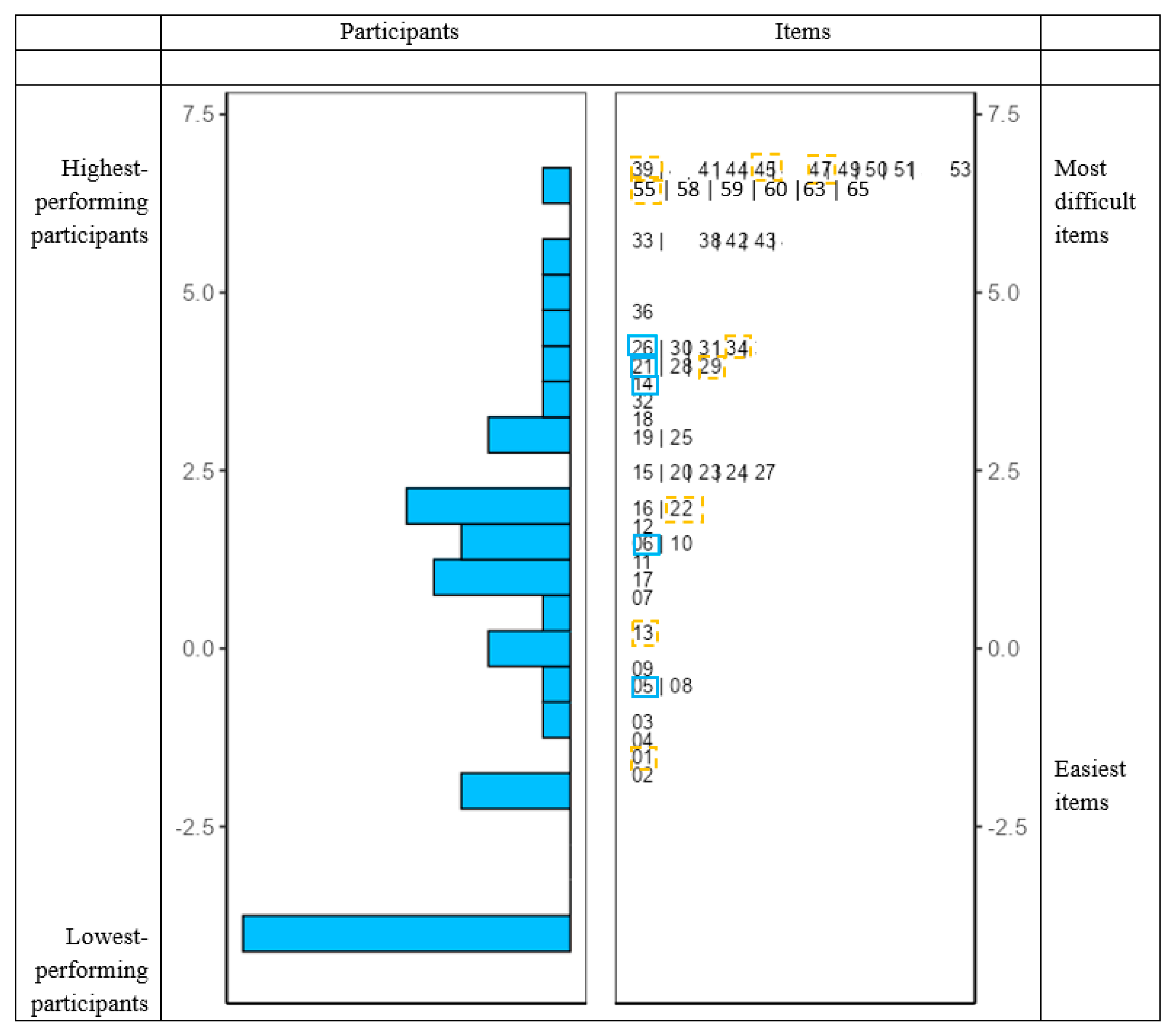

Rasch Analysis

Pearson Correlation Analyses

Inter-Correlation Matrix of Rasch Scores on Language Tests

Focus on Receptive and Expressive Lexicon

Inter-Correlation Matrix Between Hetero-Assessment and Developmental Battery Scores

Inter-Correlation Matrix Between Rasch Scores on Language Tests and Hetero-Assessment Scores

Inter-Correlation Matrix Between Rasch Scores on Language Tests and Developmental Battery Scores

Stepwise Linear Regression Analyses

Stepwise Linear Regression Predicting Rasch Scores on Language Tests from Hetero-Assessment and Developmental Battery Scores

Stepwise Linear Regression to Explain Receptive Language Scores from Hetero-Assessments and Developmental Battery Using Rasch Scores from Receptive Language Standardized Tests

Stepwise Linear Regression to Explain Expressive Language Scores from Hetero-Assessments and Developmental Battery Using Rasch Scores from Expressive Language Standardized Tests

Discussion

Feasibility of Standardized Language Testing in Children with ASD Aged 4 to 6 Years

Exploring the Concordance of Standardized Language Tests, Developmental Battery and Hetero-Assessments

Limitations and Future Directions

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, M.; Poirier, N. La démarche et les outils d’évaluation clinique du trouble du spectre de l’autisme à l’ère du DSM-5. Rev Psychoéduc. 2017, 46, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens VRuiz, C. Language and Communication in Preschool Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disorders. Children. 2021, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volden, J.; Smith, I.M.; Szatmari, P.; Bryson, S.; Fombonne, E.; Mirenda, P.; Roberts, W.; Vaillancourt, T.; Waddell, C.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Georgiades, S.; Duku, E.; Thompson, A. Using the Preschool Language Scale, Fourth Edition to Characterize Language in Preschoolers With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011, 20, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, V.; Tardif, C.; Delahaie, M.; Thomas, K.; Massion, J. Etude exploratoire des capacités phonologiques chez les enfants présentant un déficit de langage. Trav Interdisc Lab Parole Lang. 2001, 20, 149–168, https://hal.science/hal-00313776v1. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Skinner, R.; Martin, J.; Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001, 31, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houzel, D. Les signes précoces de l’autisme et leur signification psychopathologique. In Golse B. Delion P., editors. Autisme : état des lieux et horizons. Paris : Erès; 2005. p. 163–174. [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P.; Goode, S.; Hutton, J.; Rutter, M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004, 45, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadli, A. Troubles autistiques : du repérage des signes d’alerte à la prise en charge. Contraste. 2006, 25, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGiacomo, A.; Fombonne, E. Parental recognition of developmental abnormalities in autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998, 7, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatmari, P.; Archer, L.; Fisman, S.; Streiner, D.L.; Wilson, F. Asperger’s Syndrome and Autism: Differences in Behavior, Cognition, and Adaptive Functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995, 34, 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P. Outcomes in autism spectrum disorders. In: Volkmar FR. Paul R. Klin A. Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2005. p. 201–220. [CrossRef]

- Preschool - Ministry of National Education, Higher Education, and Research. Available online: https://www.education.gouv.fr/l-ecole-maternelle-11534 (accessed on 02 February 2025).

- Atzori, P.; Beggiato, A.; Colineaux, C.; Humeau, E.; Vantalon, V. Dépistage précoce, évaluation diagnostique et prises en charge éducatives précoces de l’autisme. J Pédiatr Puéric. 2022, 35, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipek, P.A.; Accardo, P.J.; Baranek, G.T.; Cook, E.H.; Dawson, G.; Gordon, B.; Gravel, J.S.; Johnson, C.P.; Kallen, R.J.; Levy, S.E.; Minshew, N.J.; Ozonoff, S.; Prizant, B.M.; Rapin, I.; Rogers, S.J.; Stone, W.L.; Teplin, S.; Tuchman, R.F.; Volkmar, F.R. The Screening and Diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999, 29, 439–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé (2018). Trouble du spectre de l’autisme – Signes d’alerte, repérage, diagnostic et évaluation chez l’enfant et l’adolescent. Recommandation de bonne pratique. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-02/trouble_du_spectre_de_lautisme_de_lenfant_et_ladolescent__recommandations.pdf.

- Rutter, M.; LeCouteur, A.; Lord, C. (2003). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

- Kover, S.T.; McDuffie, A.S.; Hagerman, R.J.; Abbeduto, L. Receptive Vocabulary in Boys with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Cross-Sectional Developmental Trajectories. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013, 43, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belteki, Z.; Lumbreras, R.; Fico, K.; Haman, E.; Junge, C. The Vocabulary of Infants with an Elevated Likelihood and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Infant Language Studies Using the CDI and MSEL. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.; Sterling, A. A Review of Language, Executive Function and Intervention in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Semin Speech Lang. 2019, 40, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, D.; Petrova, D.; Watson, L.R.; Garcia-Retamero, R.; Carballo, G. Language and motor skills in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic review. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1737–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posar, A.; Visconti, P. Update about “minimally verbal” children with autism spectrum disorder. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2022, 40, e2020158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenausky, K. ; Nelson, III.C.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Vocalization Rate and Consonant Production in Toddlers at High and Low Risk for Autism. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2017, 60, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, A.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Gu, H.; St John, T.; Paterson, S.; Elison, J.T.; Hazlett, H.; Botteron, K.; Dager, S.R.; Schultz, R.T.; Kostopoulos, P.; Evans, A.; Dawson, G.; Eliason, J.; Alvarez, S.; Piven, J. IBIS network. Behavioral, cognitive, and adaptive development in infants with autism spectrum disorder in the first 2 years of life. J Neurodev Disord. 2015, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.R.; Varcin, K.J.; O’Leary, H.M.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Nelson, C.A. (2017). EEG power at 3 months in infants at high familial risk for autism. J Neurodev Disord. 2017, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, E.J.; West, K.L.; Northrup, J.B.; Iverson, J.M. Word comprehension mediates the link between gesture and word production: Examining language development in infant siblings of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dev Sci. 2019, 22, e12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, N.; Gamliel, I.; Shaked, M.; Sigman, M. Cognitive and Verbal Abilities of 24- to 36-month-old Siblings of Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007, 37, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussu, G.; Jones, E.J.; Charman, T.; Johnson, M.H.; Buitelaar, J.K. Prediction of Autism at 3 Years from Behavioural and Developmental Measures in High-Risk Infants: A Longitudinal Cross-Domain Classifier Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018, 48, 2418–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozonoff, S.; Young, G.S.; Belding, A.; Hill, M.; Hill, A.; Hutman, T.; Johnson, S.; Miller, M.; Rogers, S.J.; Schwichtenberg, A.J.; Steinfeld, M.; Iosif, A.M. (2014). The Broader Autism Phenotype in Infancy: When Does It Emerge? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014, 53, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messinger, D.S.; Young, G.S.; Webb, S.J.; Ozonoff, S.; Bryson, S.E.; Carter, A.; Carver, L.; Charman, T.; Chawarska, K.; Curtin, S.; Dobkins, K.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Hutman, T.; Iverson, J.M.; Landa, R.; Nelson, C.A.; Stone, W.L.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Early sex differences are not autism-specific: A Baby Siblings Research Consortium (BSRC) study. Mol Autism. 2015, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, M.; Duku, E.; Armstrong, V.; Brian, J.; Bryson, S.E.; Garon, N.; Roberts, W.; Roncadin, C.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Smith, I.M. Variability in Verbal and Nonverbal Communication in Infants at Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Predictors and Outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018, 48, 3417–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, D.N.; Ibañez, L.V.; Messinger, D.S. Joint Attention Initiation with and without Positive Affect: Risk Group Differences and Associations with ASD Symptoms. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014, 44, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazenby, D.C.; Sideridis, G.D.; Huntington, N.; Prante, M.; Dale, P.S.; Curtin, S.; Henkel, L.; Iverson JMCarver, L.; Dobkins, K.; Akshoomoff, N.; Tagavi, D. ; Nelson, III.C.A.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Language Differences at 12 Months in Infants Who Develop Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016, 46, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynell, J.K.; Grubber, C.P. (1990). Reynell Developmental Language Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Association.

- Wiig, E.H.; Secord, W.; Semel, E. (1992). CELF-preschool:Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals—preschool version. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Norrelgen, F.; Fernell, E.; Eriksson, M.; Hedvall, Å.; Persson, C.; Sjölin, M.; Gillberg, C.; Kjellmer, L. Children with autism spectrum disorders who do not develop phrase speech in the preschool years. Autism. 2015, 19, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, V.; Trembath, D.; Keen, D.; Paynter, J. (2016). The proportion of minimally verbal children with autism spectrum disorder in a community-based early intervention programme. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016, 60, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tager-Flusberg, H.; Kasari, C. Minimally Verbal School-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Neglected End of the Spectrum. Autism Res. 2013, 6, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrold, C.; Boucher, J.; Russell, J. Language Profiles in Children with Autism: Theoretical and Methodological Implications. Autism. 1997, 1, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrleman, S.; Delage, H. Autism spectrum disorder and specific language impairment: overlaps in syntactic profiles. Lang Acquis. 2016, 23, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjelgaard, M.M.; Tager-Flusberg, H. An Investigation of Language Impairment in Autism: Implications for Genetic Subgroups. Lang Cogn Process. 2001; 16, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modyanova, N.; Perovic, A.; Wexler, K. Grammar Is Differentially Impaired in Subgroups of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Evidence from an Investigation of Tense Marking and Morphosyntax. Front Psychol. 2017, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Rice, M.L.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Tense marking in children with autism. Appl Psycholinguist. 2004, 25, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurm, A.; Lord, C.; Lee, L.C.; Newschaffer, C. Predictors of Language Acquisition in Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007, 37, 1721–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, D.M. (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments.

- Williams, K.T. (2007). EVT-2: Expressive vocabulary test. Pearson Assessments.

- Sparrow, S.S.; Balla, D.A.; Cicchetti, D.V. (1985). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services.

- Hedrick, D.L.; Prather, E.M.; Tobin, A.R. (1975). Sequenced inventory of communication development. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Elliott, C. (1990). Manual for the Differential Abilities Scales. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Mullen, E.M. (1985). Manual for the Infant Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Cranston, RI.

- Mullen, E.M. (1989). Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc.

- Butler, L.K.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Fine motor skill and expressive language in minimally verbal and verbal school-aged autistic children. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cichetti, D.V.; Balla, D.A. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd ed.). Minneapolis: NCS Pearson, Inc.

- Schopler, E.; Lansing, M.D.; Reichler, R.J.; Marcus, L.M. (2004). Psychoeducational Profile Third Edition (PEP-3). Pro-Ed ed. USA.

- Bovet, F.; Danjou, G.; Langue, J.; Moretto, M.; Tockert, E.; Kern, S. Les inventaires français du développement communicatif (IFCD) : un nouvel outil pour évaluer le développement communicatif du nourrisson. Méd Enf. 2005, 25, 327–332, Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/05.ifdc-2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L.; Dale, P.; Reznick, J.; Thal, D.; Bates, E.; Hartung, J.; Pethick, S.; Reilly, J. (1993). The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

- Coudougnan, E. (2012). Le bilan orthophonique de l’enfant autiste : des recommandations à la pratique. Rééduc Ortho. 2012, 50, 77–90, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:193613155 . [Google Scholar]

- Macchi, L.; Herman, F.; Colli-Vaast, L.; Merle, A.; Danchin, P. Propriétés psychométriques des tests francophones de langage oral chez l’enfant. Etud Linguist Appl. 2023, 210, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.M. Thériault-Whalen CM. Dunn LM. (1993). Echelle de Vocabulaire en Images Peabody : EVIP. Toronto : Psycan.

- Coquet, F.; Ferrand, P.; Roustit, J. (2009). EVALO 2-6. Ortho édition.

- Lecocq, P. (1996). L’E.CO.S.SE, une épreuve de compréhension syntaxico-sémantique. Villeneuve d’Ascq : Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen: Denmarks Paedogogiske Instiut. [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D.; Stone, M.H. (1979). Best Test Design. Chicago: MESA Press.

- Smith, A.B.; Rush, R.; Fallowfield, L.J.; Velikova, G.; Sharpe, M. Rasch fit statistics and sample size considerations for polytomous data. BMC Med Res Methodo. 2008, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. (2015). Applying the Rasch Model. Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fisher Jr, WP. Reliability, Separation, Strata Statistics. Rasch Meas Trans. 1992, 6, 238, https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt63i.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.D. Reliability and separation. Rasch Meas Trans. 1996, 9, 472, https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt94n.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Koegel, L.K.; Bryan, K.M.; Su, P.L.; Vaidya, M.; Camarata, S. Definitions of Nonverbal and Minimally Verbal in Research for Autism: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020, 50, 2957–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudry, K.; Leadbitter, K.; Temple, K.; Slonims, V.; McConachie, H.; Aldred, C.; Howlin, P.; Charman, T. Pact Consortium. Preschoolers with autism show greater impairment in receptive compared with expressive language abilities. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2010, 45, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervis, C.B.; Klein-Tasman, B.P. Methodological Issues in Group-Matching Designs: α Levels for Control Variable Comparisons and Measurement Characteristics of Control and Target Variables. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervis, C.B.; Robinson, B.F. Methodological issues in cross-syndrome comparisons: Matching procedures, sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp). Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1999, 64, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasari, C.; Brady, N.; Lord, C.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Assessing the minimally verbal school-aged child with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2013, 6, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; DiLavore, P.C.; Risi, S.; Gotham, K.; Bishop, S.L. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, (ADOS-2). Torrance, California: Western Psychological Services.

- Bal, V.H.; Katz, T.; Bishop, S.L.; Krasileva, K. Understanding definitions of minimally verbal across instruments: Evidence for subgroups within minimally verbal children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016, 57, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenson, L.; Marchman, V.A.; Thal, D.J. Dale Philip Reznick JS. Bates E. (2007). MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User’s Guide and Technical Manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

- DiStefano, C.; Tucker, Z.T.; Jeste, S. (2018). Choosing a definition of “minimally verbal”: characteristics of minimally verbal children with ASD in the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange. Abstracts of the INSAR (International Society for Autism Research) annual meeting. 2018, 28. https://insar.confex.com/insar/2018/webprogram/Paper28434.html.

- Kaushanskaya, M.; Marian, V. Mapping phonological information from auditory to written modality during foreign vocabulary learning. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008, 1145, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis Weismer, S.; Lord, C.; Esler, A. Early Language Patterns of Toddlers on the Autism Spectrum Compared to Toddlers with Developmental Delay. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010, 40, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyster, R.J.; Kadlec, M.B.; Carter, A.; Tager-Flusberg, H. Language Assessment and Development in Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008, 38, 1426–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, M.E.; Gigliotti, F.; Giovannone, F.; Lentini, G.; Manti, F.; Sogos, C. (2025). Developmental Patterns in Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Preschool Children. Children. 2025, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, H.L.; Couteur, A.L.; Charman, T.; Green, J.; Parr, J.R.; Grahame, V. What is the concordance between parent-and education professional-reported adaptive functioning in autistic children using the VABS-II? J Autism Dev Disord. 2023, 53, 3077–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.S.; Annaz, D.; Ansari, D.; Scerif, G.; Jarrold, C. Karmiloff-Smith A. Using developmental trajectories to understand developmental disorders. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009, 52, 336–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tager-Flusberg, H. Strategies for Conducting Research on Language in Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004, 34, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensen, L.D.; Kelley, E.; Fein, D.; Naigles, L.R. Processes of Language Acquisition in Children With Autism: Evidence from Preferential Looking. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.J.; Yelland, G.W.; Taffe, J.R.; Gray, K.M. Morphological and syntactic skills in language samples of pre school aged children with autism: Atypical development? Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012, 14, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Professions and socio-professional categories 2003. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/pcs2003/categorieSocioprofessionnelleAgregee/1?champRecherche=true (accessed on 24 September 2024).

| 1 | Saint-Louis Early Medico-Social Action Center, Saint-Jérôme Day Hospital and Pythéas Medico-Psychological Center: Edouard Toulouse Hospital Center (Marseille); Salvator Polyvalent Early Medico-Social Action Center: Salvator Hospital (Marseille); North Early Medico-Social Action Center: North Hospital (Marseille); La Bricarde Autism Nursery School Unit, Early Medico-Social Action Center and Jean Maurel Autism Nursery School Unit: Regional Association for the Integration of people with disabilities or in difficulty (Marseille, Orange and Puyricard); Florian Departemental Medico-Psycho-Pedagogical Center: General Council of Bouches-du-Rhône (Marseille), Les Tamaris Autism Nursery School Unit: Association of Parents of Disabled Children (Bollène), Aiguebelle Autism Nursery School Unit: Association of Pupils of Public Education Sud-Rhône-Alpes (Donzère), Early Medico-Social Action Centers: Union for the Management of Health Insurance Fund Establishments (Hyères and Toulon), Louis Pécout Autism Nursery School Unit: Regional Association for the Education and Placement of Handicapped Young People (La Ciotat) and Early Medico-Social Action Center: George Sand Hospital Center (La Seyne-sur-Mer). |

| Person reliability | Item infits < 0.7 | Item infits > 1.3 | Items failed by all participants | Participants scored 0 | Score distribution | |||

| Lexicon | Receptive lexicon | EVIP | .910*** | 9 | 5 | 12 | 12 (26%) | Approximately normal with a slight positive skew |

| Designation from a cue | .796*** | 2 | 1 | 0 | 15 (37%) | Uniform | ||

| Expressive lexicon | Denomination-Lex 1 | .700*** | 4 | 3 | 3 | 22 (52%) | Globally uniform | |

| Receptive comprehension | Understanding of topological terms | .619*** | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 (34%) | Positive skew | |

| E.CO.S.SE | .915*** | 27 | 6 | 19 | 12 (26%) | Approximately normal with a slight positive skew | ||

| Phonology | Denomination-Phono 1 | .733*** | 4 | 1 | 1 | 21 (50%) | Globally uniform | |

| Articulation | Orofacial and lingual praxis | .816*** | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 (24%) | Approximately normal with a slight negative skew | |

| Lexicon | Test | Mean | SD | t(df = 40) | P value | Mean differences | |

| Mean | SD | ||||||

| Receptive lexicon | EVIP | -.006 | 2.93 | -3.11** | .003 | -1.018 | .327 |

| Designation from a cue | .455 | 2.27 | -2.21* | .033 | -.557 | .252 | |

| Expressive lexicon | Denomination-Lex 1 | 1.012 | 2.12 | ||||

| Dependent variables |

Lexicon | Receptive comprehension | Phonology | Articulation | ||||

| Receptive lexicon | Expressive lexicon | |||||||

| Predictor variables |

EVIP | Designation from a cue | Denomination-Lex 1 | Understanding of topological terms | E.CO.S.SE | Denomination-Phono 1 | Orofacial and lingual praxis | |

| IFDC-12 months | Comprehension | |||||||

| Production | ||||||||

| IFDC-18 months | Comprehension | |||||||

| Production | ||||||||

| IFDC-24 months | Production | |||||||

| VABS-II | Receptive language | 22%** (simple effect) | 31%** | |||||

| Expressive language | 55%*** (simple effect) | |||||||

| PEP-3 | Receptive language | 43%*** | 20%* | 55%*** (simple effect) | ||||

| Expressive language | 19%* | 52%*** | 60%*** (simple effect) | |||||

| Total effect | 43%*** | 19%* | 52%*** | 20%* | 65%*** (simultaneous effect) | 62%*** (simultaneous effect) | 31%** | |

| Dependent variables |

IFDC-12 months | IFDC-18 months | VABS-II | PEP-3 | |||||

| Predictor variables |

Comprehension | Comprehension | Receptive language | Receptive language | |||||

| Lexicon | Receptive lexicon | EVIP | |||||||

| Designation from a cue | |||||||||

| Receptive comprehension | Understanding of topological terms | ||||||||

| E.CO.S.SE | 19%** (simple effect) | 53%*** (simple effect) | |||||||

| Total effect | 19%** | 53%*** | |||||||

| Dependent variables |

IFDC-12 months | IFDC-18 months | IFDC-24 months | VABS-II | PEP-3 | ||||

| Predictor variables |

Production | Production | Production | Expressive language | Expressive language | ||||

| Lexicon | Expressive lexicon | Denomination-Lex 1 | 57%*** (simple effect) | 52%*** (simple effect) |

|||||

| Phonology | Denomination-Phono 1 | ||||||||

| Articulation | Orofacial and lingual praxis | 39%*** (simple effect) | 24%*** (simple effect) | ||||||

| Total effect | 66%*** (simultaneous effect) | 60%*** (simultaneous effect) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).