1. Introduction

Global demand for rice has continued to rise in recent years, prompting the need for innovations in agricultural practices to ensure sustainable and efficient production. Traditional rice cultivation is challenged by unpredictable weather, pest infestations, and limited resource availability, all of which can adversely affect crop yield and quality. To overcome these limitations, the integration of technology into agriculture, particularly through smart farming systems, has emerged as a promising solution. Smart farming leverages Internet of Things (IoT) technology, automation, and data analytics to enhance agricultural efficiency, optimize resource management, and improve crop productivity [

1,

2].

Recent developments in smart farming systems have introduced advanced sensor technologies, automated control mechanisms, and real-time data processing capabilities [

3]. IoT-enabled greenhouses are specifically designed to monitor and regulate environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and soil moisture, thereby creating optimal conditions for plant growth [

4]. These systems often incorporate machine learning algorithms to interpret data and generate actionable insights, supporting better decision-making and resource allocation [

5]. Furthermore, improvements in wireless communication and cloud computing have enabled seamless integration of IoT devices, forming a responsive and interconnected agricultural ecosystem [

6,

7].

The convergence of IoT and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has significantly advanced smart agriculture. In greenhouse applications, IoT systems integrate diverse sensors and communication protocols to optimize crop production and resource efficiency [

1]. AIoT enhances intelligent decision-making, predictive analytics, and real-time monitoring [

2]. Despite challenges such as data security and infrastructure costs, IoT continues to drive precision farming and smart irrigation [

3]. Hardware and communication innovations contribute to improved productivity and sustainability [

4], while IoT applications in early fire detection and water management bolster agricultural resilience [

6,

7]. Nonetheless, economic and technical barriers remain in deploying smart sensors across agricultural settings [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The integration of AI and IoT supports enhanced data analysis and decision-making in precision agriculture [

13], with ongoing research highlighting the transformative potential of IoT in improving efficiency, reducing resource consumption, and increasing yields [

14].

Despite these advancements, several gaps persist in the development of intelligent farming systems. High implementation and maintenance costs pose challenges for small-scale farmers [

3], and interoperability issues among IoT devices hinder widespread adoption due to the lack of standardized protocols [

2]. Moreover, long-term studies are needed to assess the impacts of IoT-based agriculture on crop performance, soil health, and environmental sustainability [

4,

15].

In parallel, nano-silica has emerged as a promising fertilizer, with foliar spraying proving more effective than soil or root application. Foliar application enhances rice plant height and biomass under both normal and stress conditions [

16], as nano-silica is absorbed through leaf apoplast and distributed efficiently [

17]. Soil application, by contrast, suffers from adsorption, desorption, and polymerization reactions influenced by concentration and pH, leading to significant losses and higher dosage requirements [

18]. Foliar spraying also boosts proline levels and antioxidant enzyme activity, improving tolerance to abiotic stress [

17], particularly in saline and alkaline soils [

19].

However, to rigorously evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these application methods, a precision-controlled farming system is essential. Most existing greenhouse systems are designed for production or simulation, not for structured experimentation. This study addresses that gap by developing an IoT-equipped smart greenhouse system specifically designed as a comparative testing platform. With automated temperature control and humidity regulation, the system enables parallel testing of nano-silica fertilizer via soil and foliar application under identical environmental conditions. This transforms the greenhouse into a valid and replicable research environment, capable of supporting experimental agronomy and input optimization.

By integrating advanced technologies into a structured experimental framework, this research contributes to the development of sustainable, efficient, and data-driven rice farming practices. The system also holds potential for broader applications, including testing various fertilizer formulations, optimizing dosage and timing, and enabling predictive modeling of plant responses through future integration with machine learning.

2. Design of Control and Monitoring System

2.1. Design of Greenhouse Smart Farming System

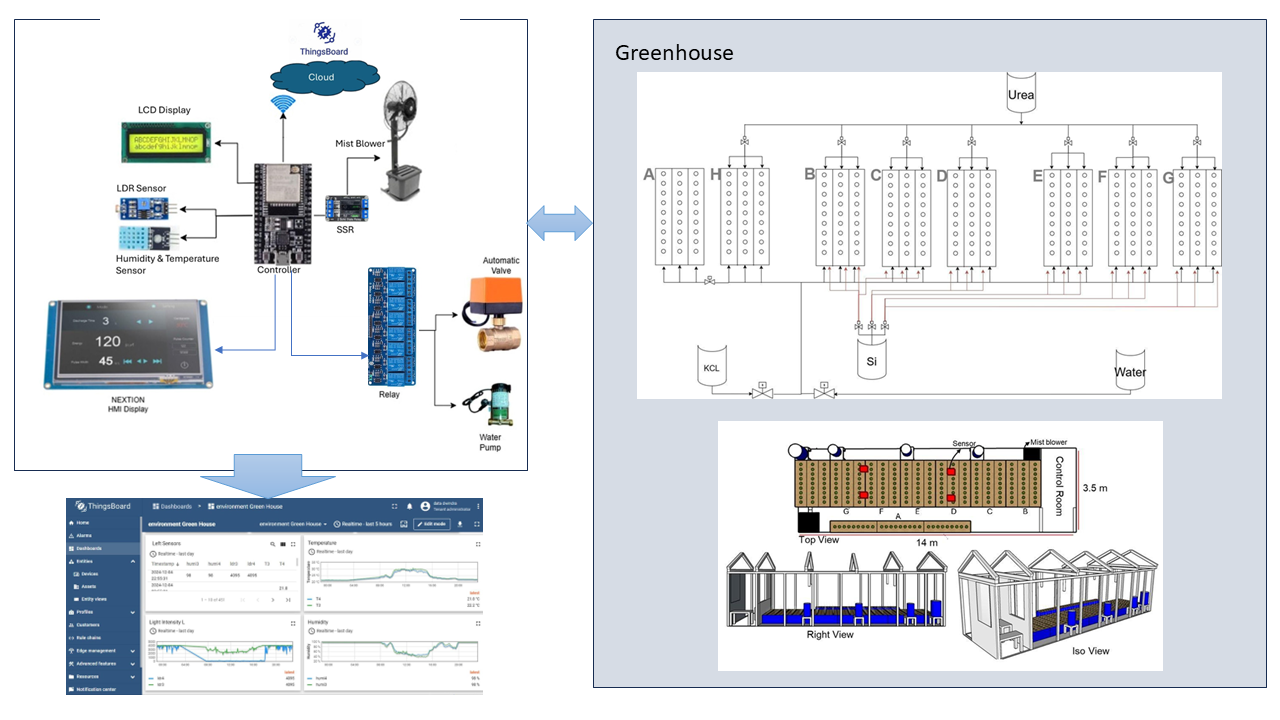

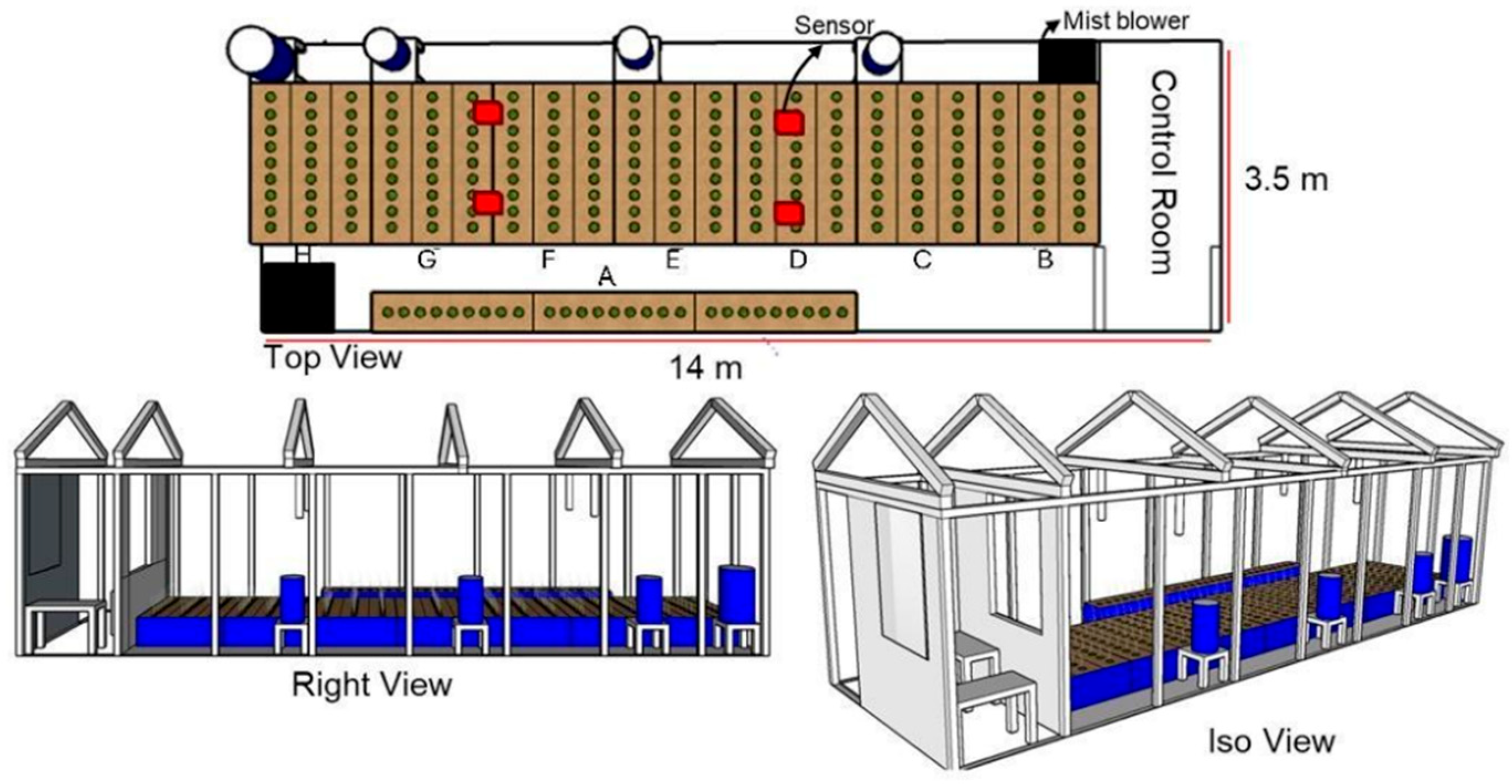

The research scenario is a test rice plant with an integrated greenhouse system with an IoT-based instrumentation system. The Greenhouse was built according to standards and is carried out in the design and build stages. The design begins with designing the greenhouse according to standards referring to the minimum greenhouse standards of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia as shown in

Figure 1.

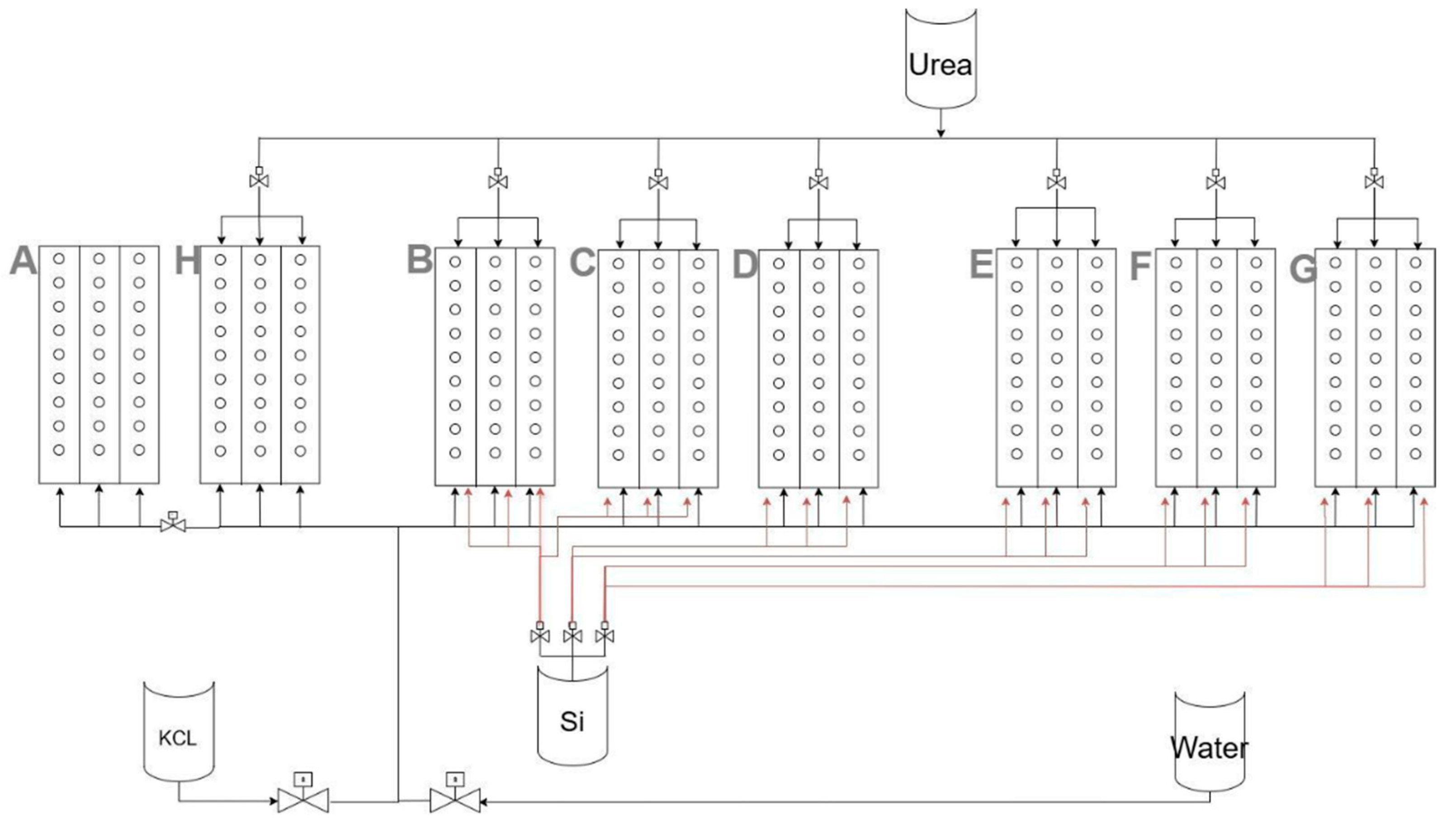

The Greenhouse design is divided into two rooms, namely the control room and the planting room. In the planting room, there are 8 containers and 4 drums (one drum 200L, three drums 120L). The containers will be used for various treatments of rice plants, while the drums are filled with fertilizer and water for irrigation and fertilization. Each container is divided into 2 partitions, creating 3 rows. Each row contains 10 clumps of rice, with each clump containing 3 rice seeds. The containers and drums are designed in such a way that they can easily flow water and fertilizer. The irrigation and fertilization design can be seen in

Figure 2.

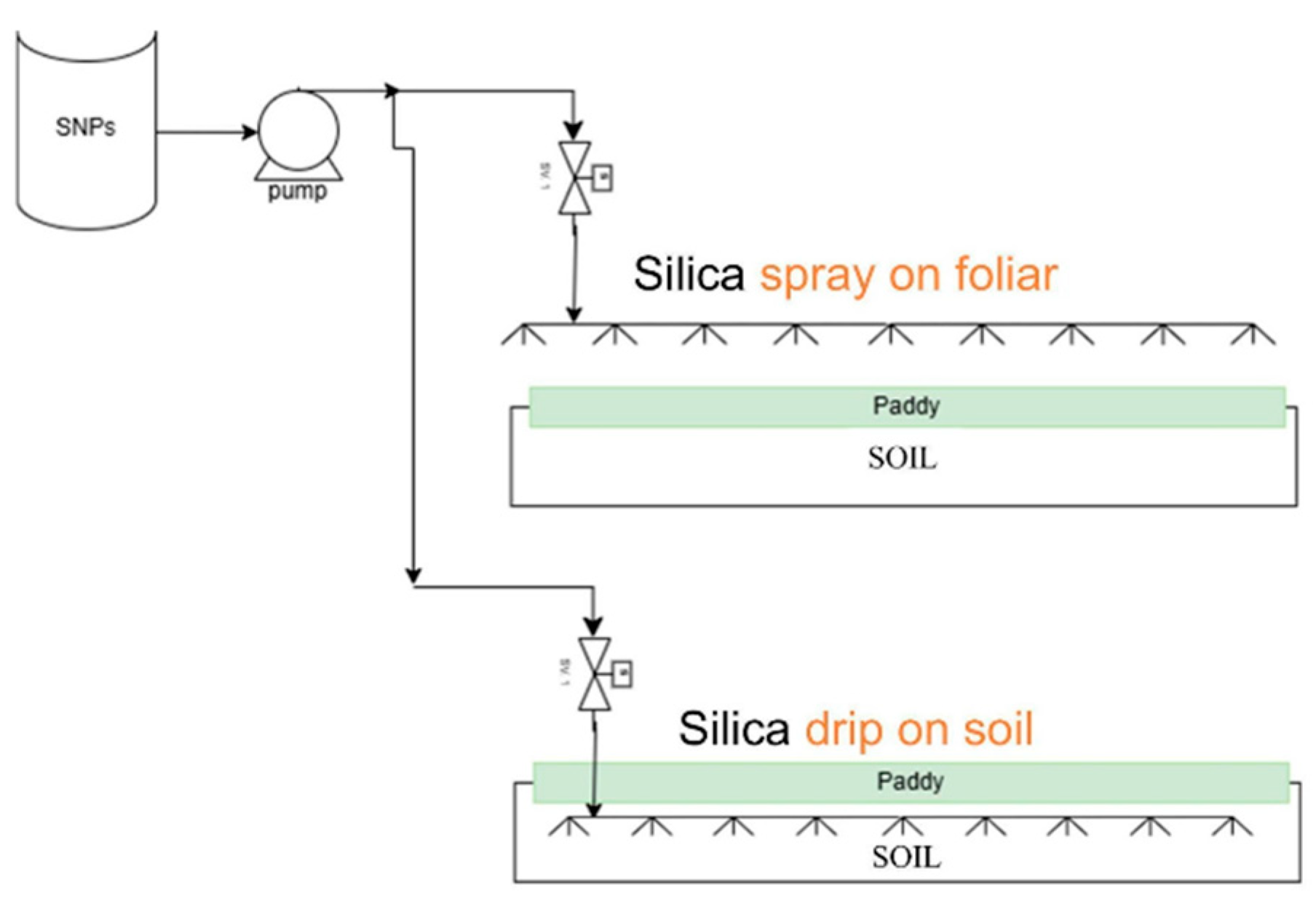

Irrigation and fertilization used a pump from a drum by setting the duration of the automatic valve opening and the duration of the pump on. The treatment was divided into 3 parts, namely via the root path and via the path. The division plan for the planting room was shown in Figure 2 which was divided into 3 parts, namely the root scheme test section, the foliar scheme test section and the control scheme test section.

The supporting schematic design for the greenhouse irrigation process is shown in

Figure 3. The design showed a diagram of the irrigation process through the roots and leaves. Water through the leaves with a sprayer. Irrigation and fertilization systems in rice crops are designed to be supported by instrumentation and IoT systems. Instrumentation and IoT-based systems can help users control the amount of irrigation and fertilization in specific doses depending on the planting substrate plot and its treatment. Plant treatment is carried out in two parts, namely through the roots (drip) and the leaves (foliar spray). Meanwhile, the dosage for plants is divided into four dosages: low, medium, high and control doses.

In tank one, which contains silica nanoparticles (SNPs), both irrigation and foliar spray schemes will be delivered from this tank. Irrigation is alternated during the fertilizer application process. Then, the other two tanks contain standard fertilizers (urea, KCl, etc.) and are applied by the flood method. The fourth tank contains only water, also applied by the flood method. The application of SNP fertilizers is developed by spraying with a nozzle.

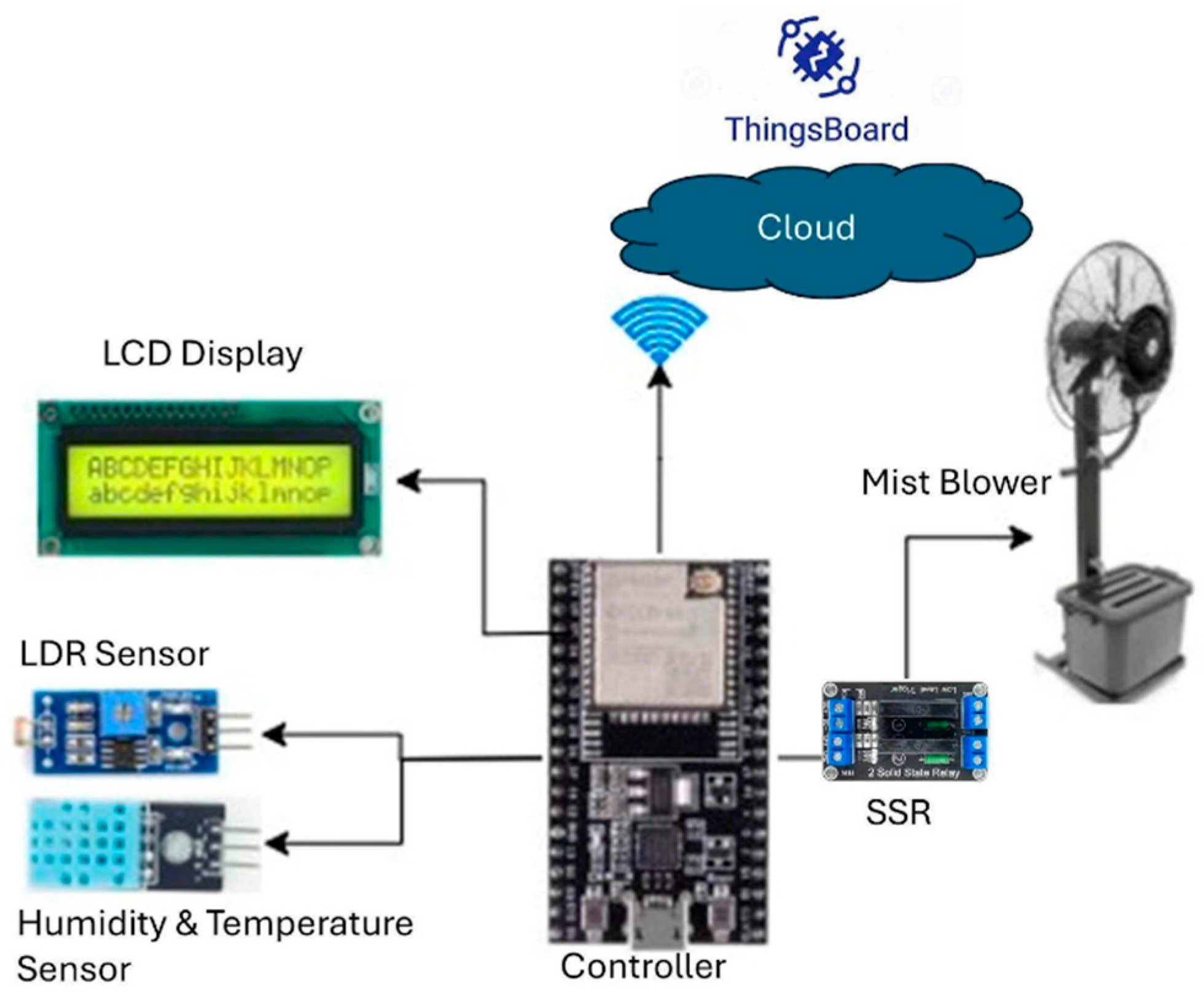

Greenhouse Smart Farming System using sensor systems to measure temperature, humidity, and sunlight intensity for optimizing plant growth control as shown in

Figure 4. Where this temperature value will be used as a control parameter to turn on the mist blower. By precisely regulating those environmental factors in real-time can enable precise management of environmental conditions, which leads to improved crop quality, increased yields, and resource efficiency. The system used consists of an Arduino ESP32 as the microcontroller built with wifi module, DHT11 sensor module for measuring temperature and environmental humidity, LDR sensor module SEN-0012 for measuring sunlight intensity and mist blower with SSR driver as a tool that will turn on if the greenhouse temperature gets too hot. The measurement results from all sensors can be monitored and viewed in real-time on the display located in the greenhouse control room and also stored in the cloud based on the Thingsboard application.

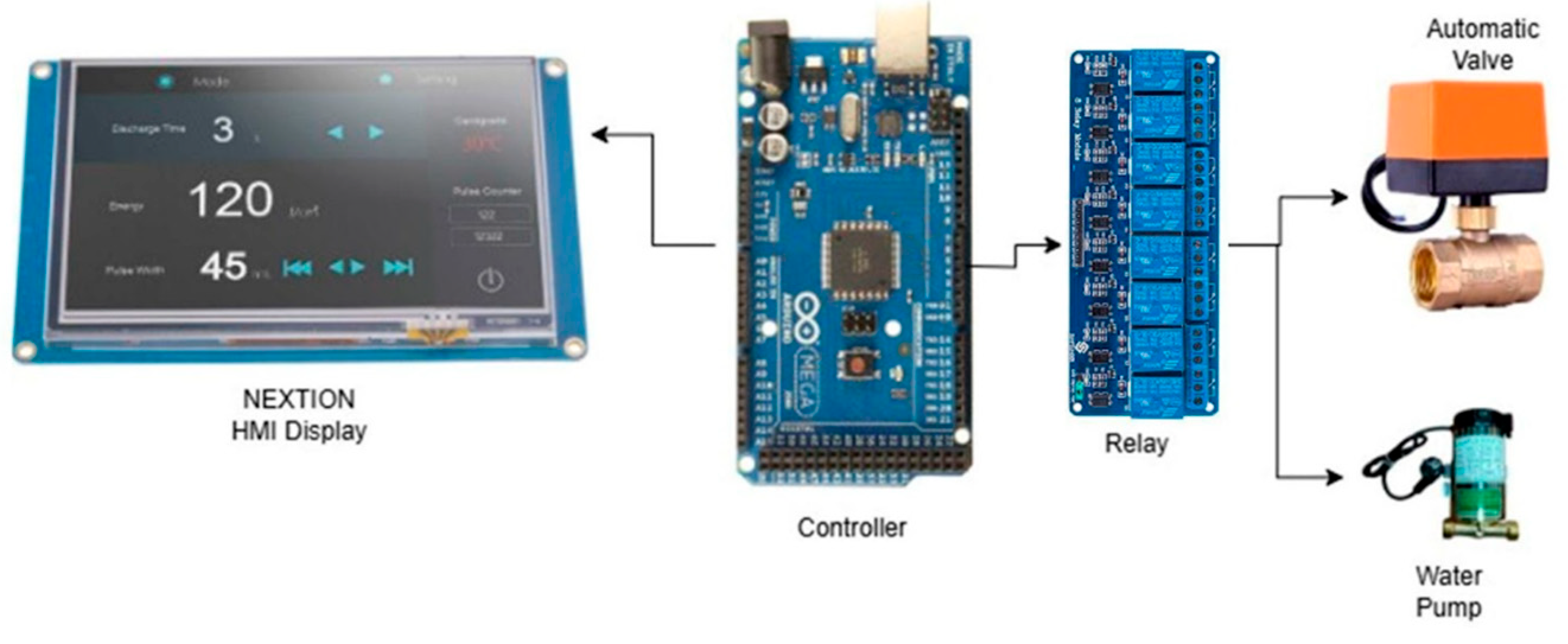

In addition, Greenhouse Smart Farming System also uses a microcontroller Mega2560, Automatic Valve, Relay module driver and Nextion HMI display (

Figure 5) to applied irrigation flow from the tank using a water pump.

2.2. Sensors

2.2.1. Temperature and Humidity Sensor

The DHT11 temperature and humidity sensor has a temperature and humidity sensor complex with a calibrated digital signal output. By using exclusive digital signal acquisition technology as well as temperature and humidity sensor technology, it ensures high reliability and excellent long-term stability. This sensor includes a resistance component for humidity measurement and an NTC temperature measurement component and is connected to a powerful 8-bit microcontroller, which provides excellent quality, fast response, anti-interference capability and cost-effectiveness.

Each DHT11 element is rigorously calibrated in the laboratory, making the humidity calibration extremely accurate. The calibration coefficients are stored as programs in OTP memory that are used by the sensor’s internal signal detection process. The single-wire serial interface enables quick and easy system integration. Its small size, low power consumption and signal transmission distance of up to 20 meters make it the best choice for various applications, even the most demanding ones. The component is a single row 4-pin package. The connection is convenient, and special packages can be provided depending on the user’s needs. The DHT11 sensor module provides a temperature range from 0°C to 50°C and a humidity range from 20% to 90%, with high reliability due to factory calibration. The DHT11 is easy to connect with microcontrollers like Arduino and Raspberry Pi. [

20]

2.2.2. Light Dependent Resistance (LDR) Sensor

A cost-effective digital and analog sensor module that can measure and detect light intensity is the LDR sensor module SEN-0012. Another name for this sensor is photoresistor sensor. The light dependent resistor (LDR) integrated into this sensor supports light detection. There are four connections on this sensor module. where the pins “DO” and “AO” stand for the digital and analog output, respectively. When there is no light, the performance of the module increases, and when there is light, it decreases. The sensitivity of the sensor can be changed using the integrated potentiometer.

The LDR sensor module consists mainly of the LDR, LM393 Comparators, Variable Resistor (Trim-pot), Power LED, output LED. LDR or light dependent resistor is a type of variable resistor. It is also called a photoresistor. The light-dependent resistor (LDR) works on the principle of “photoconductivity”. The LDR resistance changes according to the intensity of light falling on the LDR. As the light intensity on the LDR surface increases, the LDR resistance decreases and the element conductivity increases. As the light intensity on the LDR surface decreases, the LDR resistance increases and the element conductivity decreases.

The LDR sensor module has an integrated variable resistor or potentiometer. This variable resistor is preset to 10 kΩ. This sets the sensitivity of this LDR sensor. Rotate the preset knob to adjust the sensitivity of light intensity detection. If we rotate the preset knob clockwise, the sensitivity of light intensity detection will increase. If it is rotated counterclockwise, the sensitivity of light intensity detection will decrease [

21].

2.3.Control and IoT System

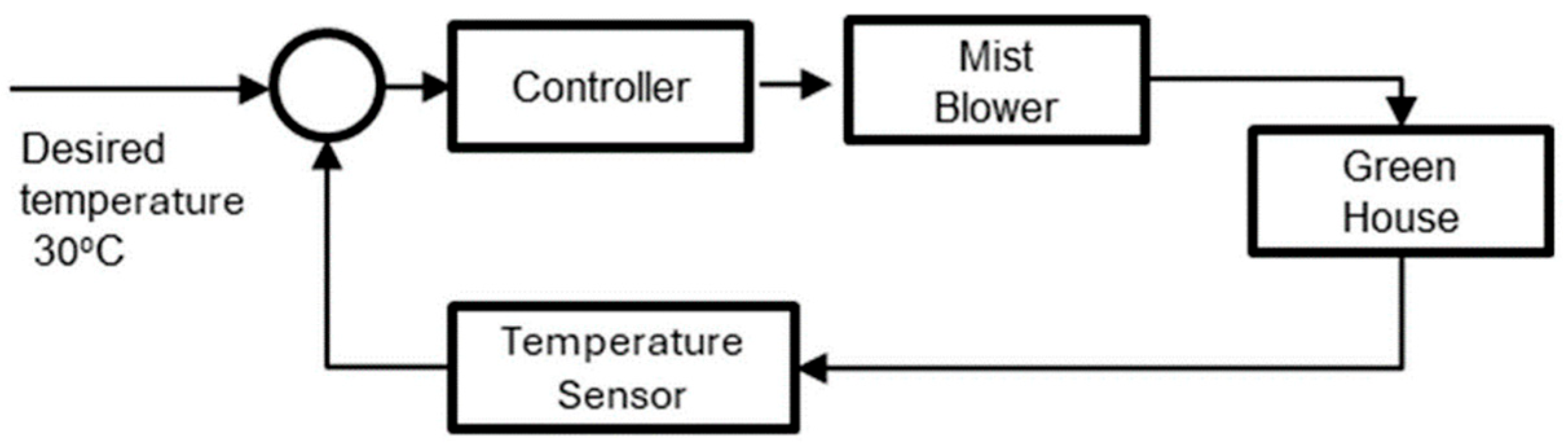

2.3.1. Control System

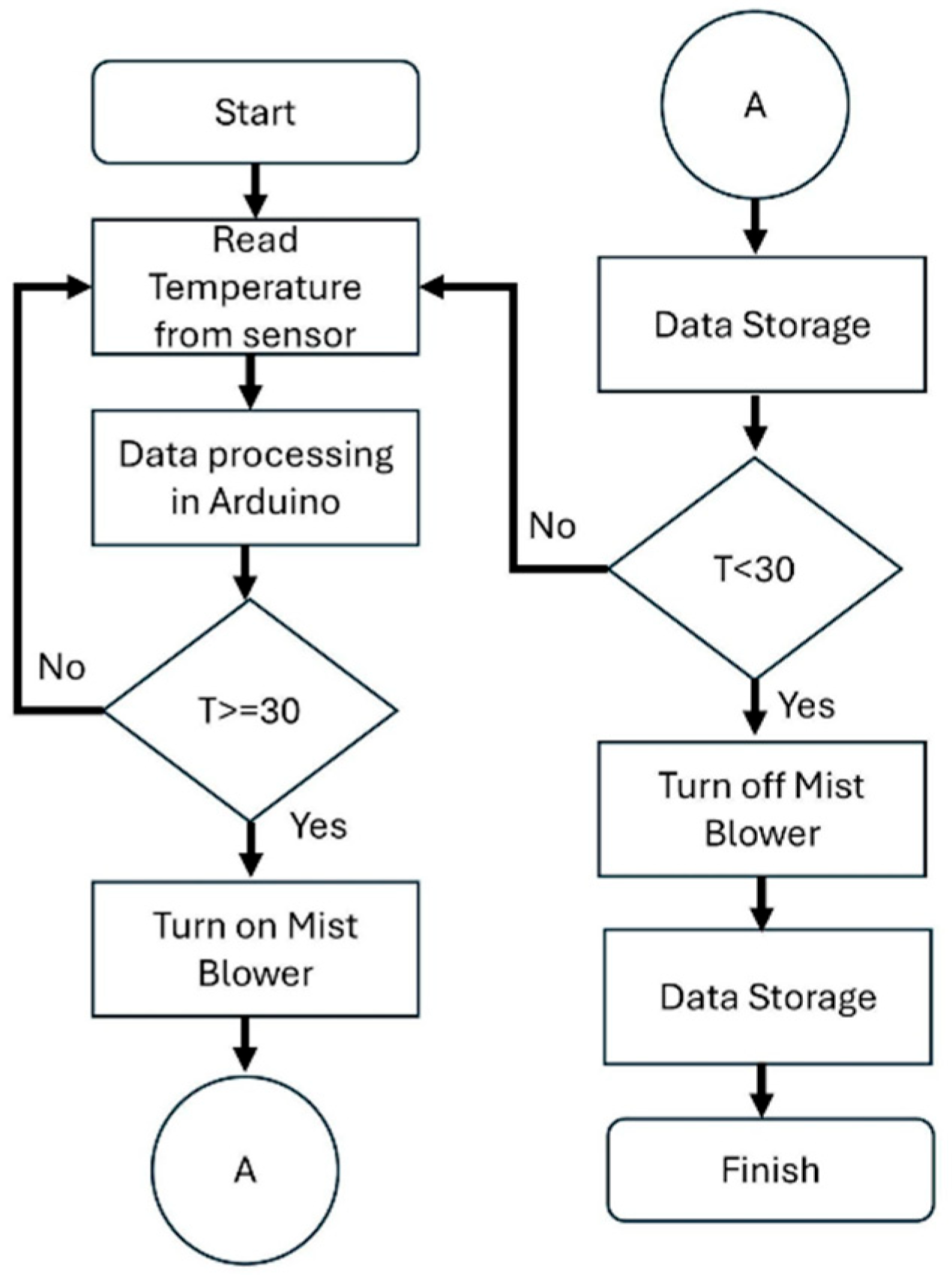

The temperature control system utilized a SSR (Solid State Relay) module that opens and closes a switch due to an input signal applied to the control circuit. The SSR module connects the DC+ terminal to the positive pole of the 5 Volt power supply. Then, DC- terminal connects to the negative pole of the power supply. The CH terminal serves as the relay module’s signal trigger terminal, which is connected to the digital output of Arduino esp32. The normally closed (NC) SSR was connected to an AC source, and the SSR’s COM pin was connected to the mist blower. The input signal is the temperature read from Arduino. When the temperature is more than 30

°C, Arduino sends the signal LOW to the SSR, activating the SSR and allowing current to flow through the circuit. When the temperature is less than 30 °C, the arduino will send a signal HIGH to the SSR then the circuit closes. The control flow chart of the system can be seen in

Figure 6.

Figure 7 shows a block diagram of the temperature room control system. The controller will keep the temperature of the greenhouse to not exceed 40 °C so that the set point temperature is set at 30 °C to turn on the blower.

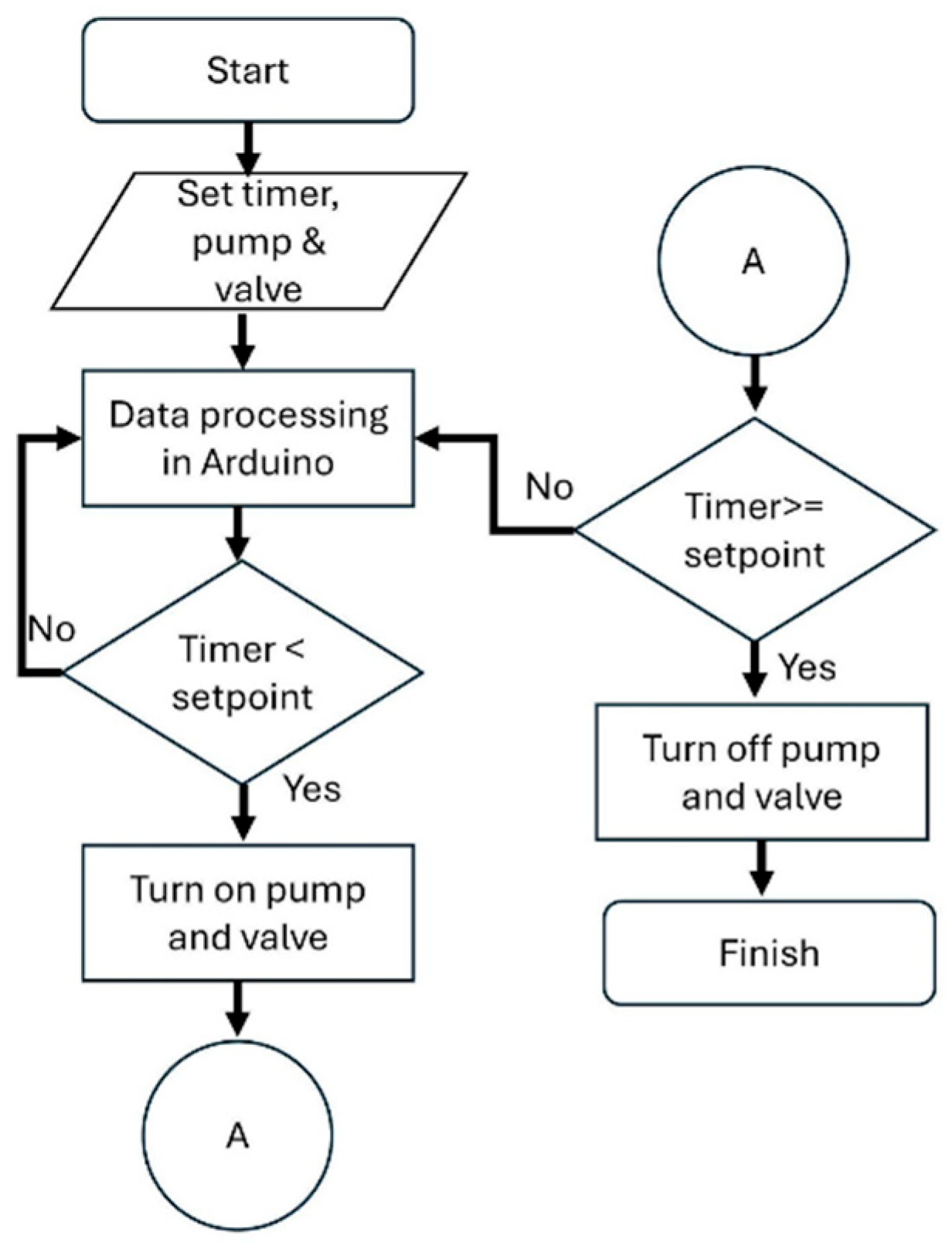

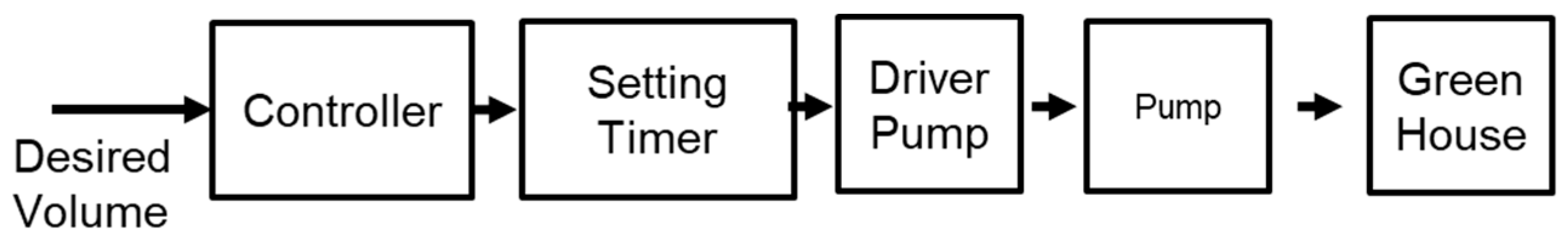

Watering and fertilizing the planting medium are measured using a timer to determine the flow rate in units of time or the flow rate of the liquid (

Figure 8). The flow rate time of the liquid to be distributed to each planting medium is used as the delay time for each automatic valve or solenoid valve (SV) to activate the ON/OFF control. Thus, the liquid is distributed to only one SV at a time and so on based on the delay time

Figure 9.

Water pump on–off control flowchart.

Figure 9.

Water pump on–off control flowchart.

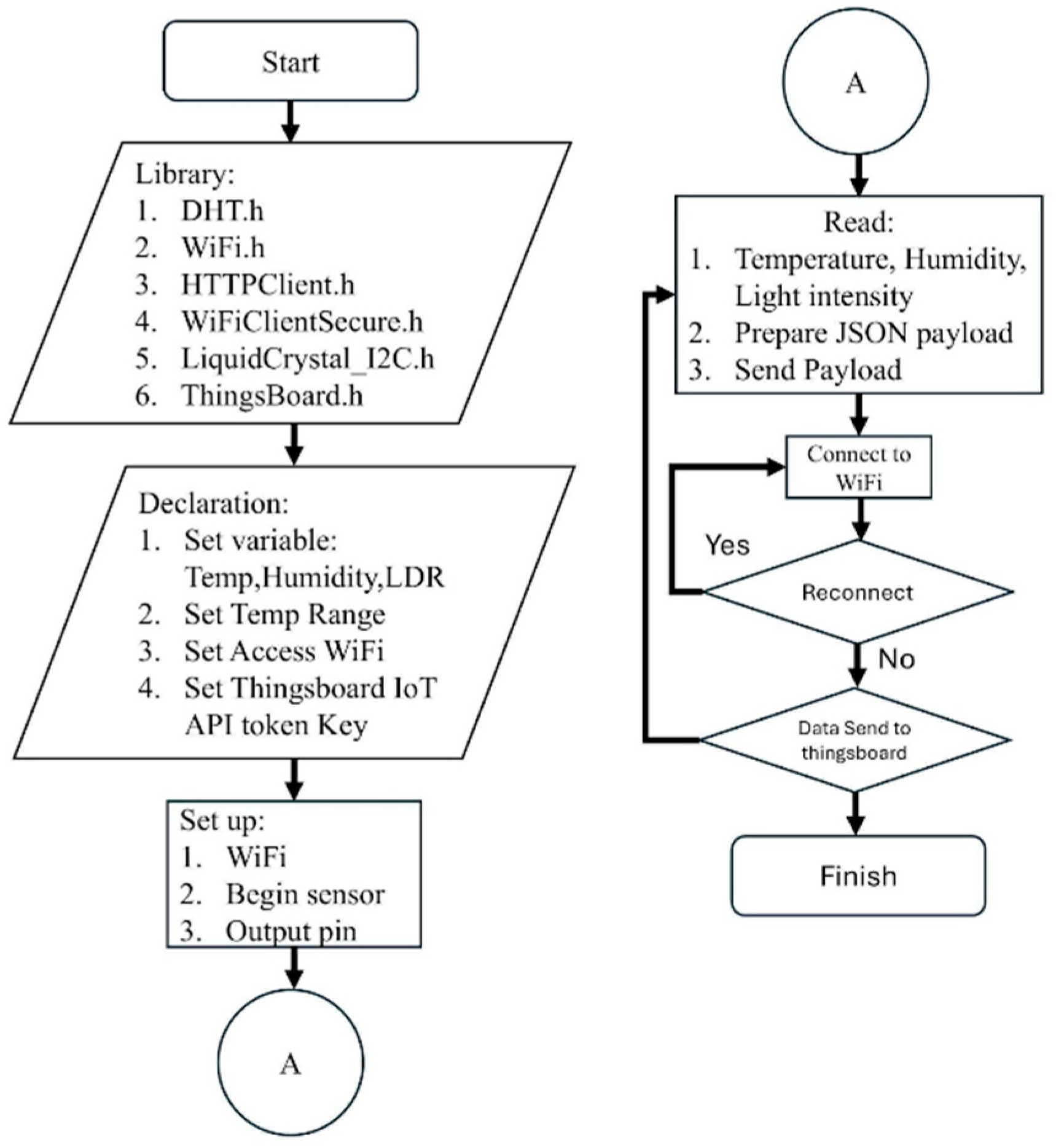

2.3.2. Hardware Description of IoT System

The ESP32 Wi-Fi module allows Arduino to connect to a wireless network. The algorithm used by Arduino to send data to the Thingsboard is shown in

Figure 10. After integrating the library, the variables humidity, light intensity, temperature as control variable, WiFi access and Thingsboard configuration access were defined and initialized to provide the functionality. The Arduino read the sensor measurement data every three minutes and transmitted it automatically and without external interference to ThingsBoard IoT via a WLAN AP. Thingsboard IoT’s opensource application program interface (API) provides an Internet of Things platform that uses the MQTT publish-subscribe network protocol to store and retrieve temperature, humidity, and light intensity data. The three main actors in the message exchange process are the publisher, the MQTT broker and the subscriber [

22,

23].

2.3.3. Sensor Characteristics

The experiment to obtain sensor characteristics was conducted by comparing the sensors with handheld sensors with better accuracy. The characteristics of sensors include accuracy, precision, and error. The accuracy of the DHT11 sensor was compared with a Ace hardware hygrometer, which has range temperature -20-70 °C, range humidity 10%-99%, accuracy ±1C and 5%RH for temperature and humidity, respectively. The Light Intensity was measured compared with the Sanwa Mobiken Illuminance meter.

2.4. Planting Design

During the growth period, standard urea fertilizer was applied three times, at 7, 21, and 36 days after planting. SP36 fertilizer was applied once, at 7 days after planting, while KCL fertilizer was applied twice, at 7 and 36 days after planting. Meanwhile, the application of silica nanoparticle (SNP) fertilizer was carried out 2 times, at 56 and 63 days after planting. The SNP application was regulated based on different doses, namely low, medium, high, and control, where the concentrations used were 100, 200, and 300 kg/ha. The application was also carried out with two different treatments: root (flood irrigation) and foliar (foliar spray). Therefore, 8 planting media were needed to conduct the treatment test on these plants. Based on statistical treatment calculations, the number of plants to be tested for each planting medium was 10 plants with 3 replicates (30 plants).

3. Results & Discussion

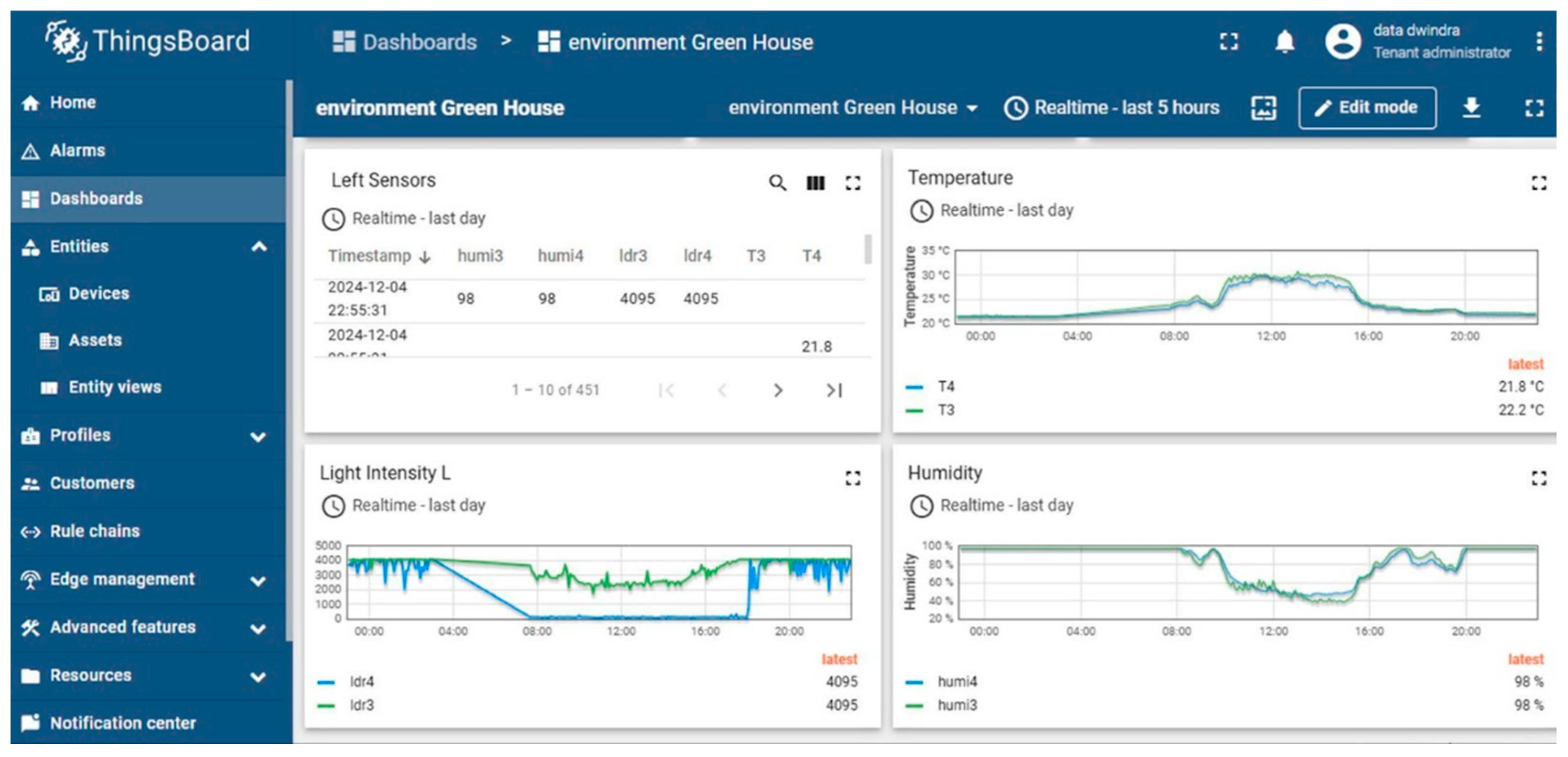

3.1. IoT-Based Environmental Monitoring for Controlled Cultivation

Environmental monitoring in this study was conducted using the Thingsboard IoT platform, which served as the central interface for real-time data acquisition and visualization. The dashboard menu on Thingsboard provided access to graphical displays of key environmental parameters, including temperature (°C), relative humidity (%RH), and light intensity (bit ADC). These parameters were plotted with time intervals on the horizontal x-axis and respective measurement values on the vertical y-axis, enabling continuous observation of microclimatic conditions within the greenhouse.

Figure 11 illustrates a one-day monitoring display with a data grouping interval of 3 minutes, showcasing the system’s capability to capture high-resolution environmental fluctuations. This granularity is essential for precision agriculture, as it allows for the detection of subtle changes that may influence plant physiology and growth dynamics. The data were not only visualized in real-time but also archived and exported to Google Excel for further analysis, as shown in

Figure 12. This dual-mode accessibility—live monitoring and retrospective data logging, enhances the analytical robustness of the system and supports longitudinal studies.

The integration of Thingsboard with ESP32 microcontrollers and sensor arrays reflects the broader trend in smart agriculture toward cyber-physical systems that combine sensing, control, and data analytics [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Such systems enable researchers to maintain environmental parameters within tightly controlled thresholds, which is particularly critical when conducting comparative experiments, such as evaluating the efficacy of nano-silica fertilizer via foliar versus soil application. By minimizing external variability, the greenhouse functions as a replicable and scalable platform for experimental agronomy.

Moreover, the ability to export structured datasets facilitates statistical analysis and modeling, allowing researchers to correlate environmental conditions with plant responses. This supports the development of predictive frameworks and decision-support tools, as emphasized in recent literature on AIoT applications in agriculture [

2,

5,

13]. The system’s responsiveness and data fidelity thus contribute not only to operational efficiency but also to scientific rigor in agricultural experimentation.

In summary, the environmental monitoring infrastructure established through Thingsboard and supporting technologies provides a foundation for precision-controlled cultivation. It transforms the greenhouse from a passive growing space into an active research environment, capable of supporting complex experimental designs and advancing the frontiers of smart farming.

3.2. Planting Design

3.2.1. Greenhouse with IoT System

The developed greenhouse system, integrated with an IoT-based instrumentation and control framework, is shown in

Figure 13. This system was designed to support precision rice cultivation through a structured sequence of agronomic processes. The cultivation began with the preparation of the planting medium, which involved soaking Inceptisol soil, slurrying, and organic fertilization using manure. The soil was first dried and finely ground, then placed in trays and submerged with water approximately 1 cm above the surface. This soaking phase lasted seven days, followed by uniform stirring to initiate the slurry process, which was allowed to settle for another seven days. Subsequently, manure was mixed evenly into the sludge and left to stabilize for two weeks, forming a nutrient-rich medium. High-quality rice seeds were then sown into this prepared substrate, marking the transition to the seedling and transplantation phases. These steps are documented in

Figure 13.

Following transplantation, the cultivation process progressed into the monitoring phase, supported by scheduled irrigation and fertilization. Throughout these stages, the IoT system played a central role in maintaining optimal environmental conditions. Real-time monitoring of temperature, humidity, and sunlight intensity was conducted via the Thingsboard IoT platform, which provided continuous data visualization and logging capabilities. These parameters were displayed on the dashboard interface and stored for retrospective analysis, enabling researchers to correlate environmental fluctuations with plant growth responses [

1,

3,

4]. The rice cultivation workflow within the greenhouse is illustrated in

Figure 14.

The integration of IoT technology into the greenhouse system exemplifies the transformative potential of smart farming in modern agriculture. By enabling precise control over microclimatic variables, the system enhances resource efficiency and supports optimal plant development. This aligns with the broader objectives of precision agriculture, where data-driven approaches are employed to improve productivity and sustainability [

2,

5,

6]. The successful implementation of this system demonstrates how traditional agricultural practices can be augmented through technological innovation, paving the way for scalable and replicable smart farming models.

3.2.2. Control Temperature Performance

Temperature regulation within the greenhouse was successfully achieved through an advanced IoT-integrated control system, which consistently maintained the internal temperature at 30°C (

Figure 15). This level of precision is critical for rice cultivation, as temperature directly influences physiological processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and nutrient uptake. The system’s performance was documented both before and after implementation, clearly demonstrating its effectiveness in stabilizing the microclimate and minimizing plant stress.

The temporal consistency of temperature throughout the planting process is further illustrated in

Figure 16, which shows the system’s ability to maintain optimal conditions over time. This stability is essential for experimental agriculture, where environmental uniformity ensures that observed plant responses can be attributed to specific treatments, such as fertilizer application, rather than uncontrolled external factors.

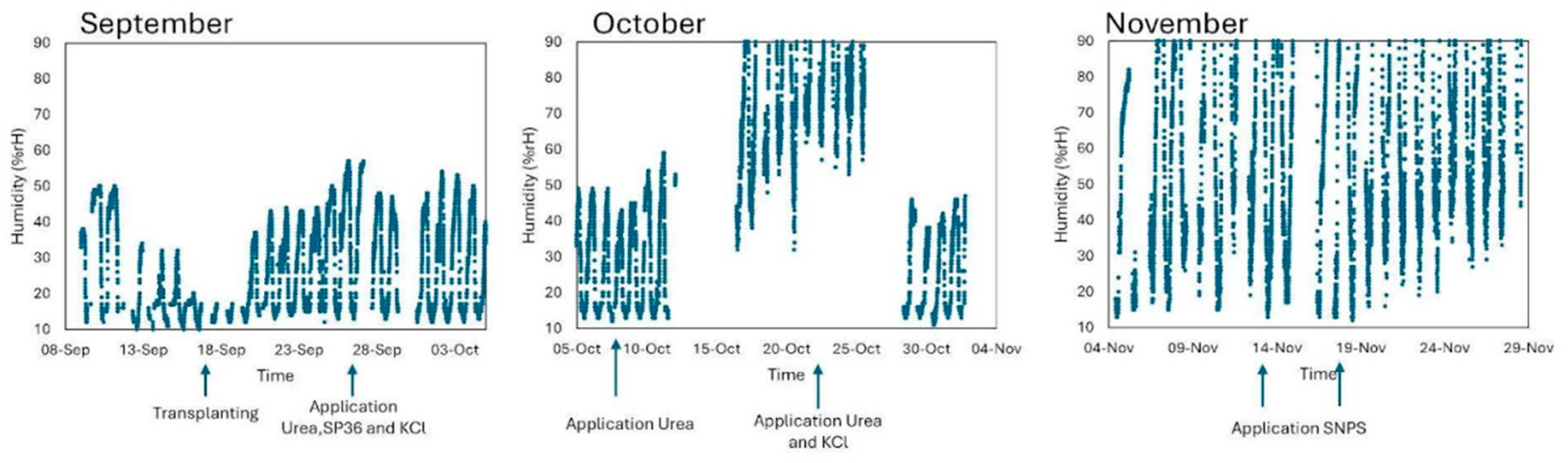

In addition to temperature, humidity levels were also monitored and maintained within optimal ranges, as shown in

Figure 17. This dual-parameter control reinforces the greenhouse’s role as a precision platform for agricultural experimentation.

IoT-based systems offer significant advantages in greenhouse management by enabling continuous monitoring and dynamic adjustment of environmental conditions [

2,

3,

4]. In regions with pronounced diurnal temperature variations, such as tropical climates, maintaining a stable internal temperature can be challenging. The system’s ability to respond to real-time sensor data and automatically regulate heating or cooling inputs ensures that rice plants are not exposed to thermal stress, which could compromise growth and yield.

Moreover, the integration of machine learning algorithms enhances the system’s predictive capabilities, allowing it to anticipate environmental changes and adjust proactively [

6]. This intelligent control mechanism supports long-term sustainability by reducing energy consumption and optimizing resource use.

Consistent temperature regulation is not only beneficial for plant physiology but also contributes to improved crop quality and productivity [

5]. The success of this control system underscores the feasibility of deploying IoT technologies in precision agriculture and highlights their potential for broader adoption in both to support precision rice cultivation, structured experimentation research and commercial farming contexts. By ensuring environmental stability, the system enables rigorous testing of agronomic interventions, such as nano-silica fertilizer application, under controlled conditions, thereby advancing the scientific understanding of crop responses and supporting data-driven agricultural innovation.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully designed and implemented a smart greenhouse system equipped with IoT technology to support precision rice cultivation and structured experimentation. The system demonstrated consistent performance in monitoring and regulating key environmental parameters—temperature, humidity, and light intensity—ensuring optimal and stable growing conditions throughout the cultivation process. Beyond its role as a cultivation space, the greenhouse was purposefully developed as a comparative research platform, enabling parallel testing of nano-silica fertilizer application via foliar and soil methods under identical environmental conditions. This design minimizes external variability and enhances the reliability of treatment evaluation, addressing a critical gap in agricultural experimentation where environmental inconsistency often limits the validity of comparative studies. The successful deployment of this system highlights the potential of smart farming technologies to improve agricultural productivity, resource efficiency, and sustainability. It also demonstrates how traditional farming practices can be transformed through digital innovation, offering scalable and replicable models for both research and commercial use.

In conclusion, the IoT-enabled greenhouse system provides a robust foundation for future agricultural experimentation. Its precision control and data-driven architecture support advanced input testing, including dosage optimization and interaction studies, and open pathways for integration with predictive analytics—contributing meaningfully to the advancement of sustainable and intelligent food production systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.J., D.W.M., O.M. and C.P.; methodology, I.M.J., D.W.M. and O.M.; software, D.W.M.; validation, I.M.J., F.F., O.M., C.P., N.N.R, P.W., K.M.P, S.V., A.A., M.H. and N.L.W.; formal analysis, D.W.M., F.F. and O.M.; investigation, D.W.M. and O.M.; resources, I.M.J; data curation, I.M.J., D.W.M., F.F. and O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.J, D.W.M. and O.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M.J., F.F., O.M., C.P., N.N.R, P.W., K.M.P, S.V., A.A., M.H. and N.L.W.; visualization, D.W.M. and O.M.; supervision, I.M.J.; project administration, D.W.M. and C.P.; funding acquisition, I.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Riset Kolaborasi Indonesia with contract no. 2213/UN6.3.1/TU.00/2024; and The APC was funded by Universitas Padjadjaran.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Mrs. Dyah Pramesti L for their help and technical support during the Integration and performance testing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khalid, M.H.; Walaa, M.E.; Farid, M.S. Technologies, Protocols, and applications of Internet of Things in greenhouse Farming: A survey of recent advances. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, 12 (1), 91-111. [CrossRef]

- Dalhatu, M.; Ehsan, A.; Shohreh, A.; Maria, T.; Marie-José, M.; Reza, E. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for smart agriculture: A review of architectures, technologies and solutions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl., 2024, 228, 103905. [CrossRef]

- Bam, B.S., Dhanalakshmi, R. Recent advancements and challenges of Internet of Things in smart agriculture: A survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 126, 169-184. [CrossRef]

- Chander, P.; Lakhwinder, P.S.; Ajay, G.; Shiv, K.L. Advancements in smart farming: A comprehensive review of IoT, wireless communication, sensors, and hardware for agricultural automation. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 2023, 362, 2023, 114605, ISSN 0924-4247. [CrossRef]

- Biswaranjan, A.; Kyvalya, G.; Anuradha, Y.; Sujata, D. Chapter 1 - Internet of things (IoT) and data analytics in smart agriculture: Benefits and challenges, Editor(s): Ajith, A.; Sujata, D.; Joel, J.P.C.R.; Biswaranjan, A.; Subhendu, K.P. In Intelligent Data-Centric Systems, AI, Edge and IoT-based Smart Agriculture, Academic Press 2022, 3-16, ISBN 9780128236949. [CrossRef]

- Abdennabi, M.; Zahra, O.; Rachid, E.A.; Hassan, Q.; Mohammed, O.J.; Haris, M.K. Integrated internet of things (IoT) solutions for early fire detection in smart agriculture, Results in Engineering 2024, 24, 103392. [CrossRef]

- Abdennabi, M.; Rachid, J.; Haris, M.K.; Rachid, E.A.; Hassan, Q.; Mohammed, O.J. IoT-based smart irrigation management system to enhance agricultural water security using embedded systems, telemetry data, and cloud computing, Results in Engineering 2024, 23, 102829. [CrossRef]

- Prem, R.; Abhratanu, G.; Satadal, A.; Suchandra, B. Internet of Things and smart sensors in agriculture: Scopes and challenges, J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100776. [CrossRef]

- Abdennabi, M.; Ishaq, G.M.A.; Haris, M.K.; Rachid, E.A.; Surendar, R.S.; Muyeen, S.M. High-technology agriculture system to enhance food security: A concept of smart irrigation system using Internet of Things and cloud computing. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2024, ISSN 1658-077X. [CrossRef]

- Vijendra, K.; Kul, V.S.; Naresh, K.; Anant, P., Tanmay, R.K.; Upaka, R. A comprehensive review on smart and sustainable agriculture using IoT technologies. Smart Agri. Technol. 2024, 8, 100487, ISSN 2772-3755. [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, M.; Akshaya, R.; Sreejith, K. An Internet of Things-based Efficient Solution for Smart Farming, Procedia Comp. Sci. 2023, 218, 2806-2819. [CrossRef]

- Vivek, R.P.; Narendra K.; Sandeep, K.; Antar, S.H.A.; Ajay, K.V. A systematic review of IoT technologies and their constituents for smart and sustainable agriculture applications, Scientific African 2023, 19, e01577. [CrossRef]

- Maged, E.A.M.; Muhammad, M. Chapter 3 - Towards smart farming: applications of artificial intelligence and internet of things in precision agriculture, Editor(s): Sartajvir, S.; Vishakha, S.; Arun, L.S.; Yiannis, A. Hyperautomation in Precision Agriculture, Academic Press 2025, 27-37, ISBN 9780443241390. [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekar, S..; A comprehensive review on current issues and advancements of Internet of Things in precision agriculture, Computer Science Review 2025, 55, 100694, ISSN 1574-0137. [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraju, M.; Chenniappan, P.; Ramalingam, K.; Pazhanivelan, S.; Kaliaperumal, R. Smart farming: Internet of Things (IoT)-based sustainable agriculture. Agriculture 2022, 12(10), 1745. [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.S.; El-Hami, K.; Kodaki, T.; Matsushige, K.; Makino, K. A novel method for synthesis of silica nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 28, 125–131. [CrossRef]

- Elshayb, O. M.; Nada, A.M.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Amin, H.E.; Atta, A.M. Application of silica nanoparticles for improving growth, yield, and enzymatic antioxidant for the hybrid rice ehr1 growing under water regime conditions. Materials 202), 14(5), 1150. [CrossRef]

- Keeping, M.G. Uptake of silicon by sugarcane from applied sources may not reflect plant-available soil silicon and total silicon content of sources. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017. 8, 760. [CrossRef]

- Saad K.A.M.; Abouelsoud, H.M.; Hafez, E.M.; Ali, O.A.M. Integrated effect of nano-Zn, nano-Si, and drainage using crop straw–filled ditches on saline sodic soil properties and rice productivity. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2019, 12, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Datasheet DHT11, “DHT11 Humidity & Temperature Sensor”, Access: https://www.mouser.com/datasheet/2/758/DHT11-Technical-Data-Sheet-Translated-Version-1143054.pdf.

- Electroduino. (n.d.). “LDR Sensor Module: How LDR Sensor Works”, Access: https://www.electroduino.com/ldr-sensor-module-how-ldr-sensor-works/#Introduction.

- Azzola, F. Android Things Projects, 1st ed.; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017; pp. 1–232.

- Suriasni, P.A.; Faizal, F.; Hermawan, W.; Subhan, U.; Panatarani, C.; Joni, I.M. IoT Water Quality Monitoring and Control System in Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor to Reduce Total Ammonia Nitrogen. Sensors 2024, 24, 494. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).