Introduction

We situate this manuscript not by the binary “P = NP” or “P ≠ NP”, but by two complementary accounting equations that govern our evaluation ledger: (i) P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 (credit conservation at structural layer L and time window t), and (ii) P(L, t + Δ) − P(L, t) = −(NP(L, t + Δ) − NP(L, t)) (zero-sum transport of credited reasons across registered perturbations Δ).

Together, these constraints — adopted from the hypothesis-first program in [

1] — treat evidence as a conserved quantity: gains in constructive computation P are exactly offset by reductions in certificate-based reasoning NP, and vice versa, within each audited window and layer.

Position A — P = NP (classical, constructive emphasis). If NP collapses to P, decision and verification align asymptotically. While unproven, a large body of constructive practice points to regimes where SAT behaves as if efficiently decidable: modern preprocessors and in-processing pipelines (unit/pure propagation, blocked clause elimination, component decomposition), algebraic modules for XOR/Gaussian elimination [

14,

15], and ubiquitous proof logging with DRAT/DRUP [

6,

7]. Empirically, industrial and crafted instances often succumb to these structures, yielding fast decisions plus publicly checkable artifacts.

On the theory side, proof complexity has clarified simulations among inference systems [

4] and connections between algorithmic procedures and proof strength [

2,

3,

4,

5], yet no universal polynomial-time algorithm for SAT is known.

How This Contributes to Our Co-Evolution Lens

• It motivates a constructive channel in the ledger: P(L, t) should gain credit when π-rounds and local structure (e.g., XOR blocks, low-treewidth regions) drive branchwise polynomial termination with verifiable certificates.

• It suggests where to look for the kernel K: variables causally central to dissolving observed obstructions, consistent with greedy hitting-set over radius-2 witnesses.

• It fits the evidence that travels principle: under perturbations (renamings, rewiring), we can test whether the reasons behind fast decisions persist.

Position B — P ≠ NP (classical, barrier emphasis). If SAT resists uniform polynomial algorithms, kernelization lower bounds and sparsification barriers caution against broad compressions and nontrivial uniform kernels [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Cross-composition shows many problems (including SAT encodings) are unlikely to admit polynomial kernels unless unlikely collapses occur [

9]; sparsification results indicate there is no sublinear representation preserving satisfiability unless the polynomial hierarchy collapses [

10]. Treewidth-based algorithms delineate tractable islands but remain exponential in the parameter and thus do not yield general-case polynomiality [

11].

How This Contributes to Our Co-Evolution Lens

• These results act as scope guards: they shape the registered windows in which we test our hypotheses and prevent over-generalization.

• They justify the two-channel accounting: when obstructions persist, NP(L, t) should carry the weight via certificate-centric evidence (e.g., DRAT) rather than claiming constructive wins.

• They encourage falsifiers and stress tests (e.g., hardening instances against sparsification-like shortcuts), clarifying when the proposed K must grow or fails to yield universal branch certification.

Synthesis toward co-evolution. Rather than seeking a permanent verdict, the current research/practice market around NP-complete problems offers two complementary streams we co-opt: (i) structure-exploiting methods with verifiable proof pipelines (modern preprocessing/in-processing, DRAT/DRUP logging, XOR/GE modules, bounded-treewidth DP) [

6,

7,

11,

14,

15]; and (ii) barrier frameworks (kernelization lower bounds, sparsification limits, proof-complexity insights) that circumscribe where uniform guarantees are unlikely [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Our program integrates both with a ledger view — crediting constructive computation vs. certificate-centric reasoning via P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 — and testing whether reasons travel across layers and time.

How Prior Analyses of NP-Complete Problems Feed the Constructive Channel (P)

• Backdoor sets to tractable classes. Work on strong/weak backdoors and “islands of tractability” in SAT/CSP suggests that small variable sets can collapse hard structure when fixed (e.g., to Horn, 2-SAT, bounded width). Our kernel K operationalizes this intuition with radius-2 witnesses and a greedy hitting-set scheme, audited via branchwise certificates.

• Phase-transition and planted-structure studies. Results on random 3-SAT near the critical clause/variable ratio and on planted/backbone instances indicate when propagation, autarkies, and XOR lifting bite. These literatures provide stress grids to probe whether |K| = O(log n) and universal branch certification persist below/at/above criticality.

• Community structure in industrial SAT. Real-world formulas exhibit modularity, hubs, and near-decomposability, motivating our π-rounds decomposition and local obstruction catalog. Candidates for K can be ranked by centrality/coverage over communities; transport can be tested via community-preserving rewiring.

• Algorithm selection and portfolios. Feature-based selection shows different mechanisms dominate in different regions. In our ledger, P(L, t) gains credit when π-rounds + K yield polynomial termination with compact certificates; otherwise credit shifts to NP(L, t) via proofs, while we log why constructive routes failed.

How Barrier Programs Strengthen the Certificate Channel (NP) and Governance

• Kernelization lower bounds and sparsification. These results discipline claims: we restrict to per-instance objects (K) and registered windows, avoiding global kernelization claims. When obstructions persist (e.g., cross-composition-like hardness, XOR density that defeats GE simplifications), the ledger shifts credit to NP(L, t): we still produce DRAT/DRUP artifacts and verification logs, turning negative results into transportable evidence.

• Proof-complexity insights. Links between CDCL, resolution, and stronger systems inform RUP→DRAT aggregation and where to expect proof-size blow-ups. Failures to keep branchwise proofs small are data that falsify or refine our hypotheses.

Concrete reuse in our pipeline.

Catalog design: include motifs from backdoor and community literatures (Horn/2-SAT pockets, XOR blocks, high-degree hubs, separators suggested by treewidth probes).

Witness extraction: compute radius-2 neighborhoods; define tiny T(o) whose single-bit fixes break or weaken the obstruction.

K construction: apply greedy set cover over {T(o)}; stop at |K| ≤ c·log n (or earlier if all obstructions are hit) [

12].

Branch termination: (A) replay π-rounds under α with RUP→DRAT aggregation [

6,

7]; (B) when tw ≤ c·log n, run bag-wise DP with emitted certificates [

11,

13].

Transport tests: evaluate across phase-transition grids, industrial suites with community structure, and planted/backbone controls, tracking how |K|, certificate sizes, and verifier times move under renamings, rewiring, XOR injection, and clause noise.

Our stance — multilayer, time-indexed evidence. Following [

1], we adopt a governance-first, hypothesis-driven program in which evidence is gathered under registered budgets, seeds, and protocols and assessed by how reasons travel across perturbations. We frame evaluation by P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1, where t indexes time windows and L indexes structural layers (neighborhoods, decompositions, proof routes). The equation is a ledger metaphor, not a class identity: constructive computation (P) and certificate-based reasoning (NP) may trade off across windows and layers, but their credited sum is conserved by design.

Terminology. Here, kernel denotes a small, per-instance branching set K ⊆ V(F) used to structure exploration and certification; it is not a parameterized kernelization of the instance.

Contributions (conceptual).

A precise test object: a small, auditable kernel K for 3-SAT with branchwise polynomial terminalization and verifiable certificates (assignment or DRAT/DRUP).

A π-rounds normalization sketch combining standard simplifications with linear-algebraic XOR modules [

14,

15].

A finite catalog of local obstructions with radius-2 witness sets enabling targeted branching.

A greedy hitting-set routine to assemble K, with audit logs and certificate hooks [

12].

Branch-termination strategies that aggregate RUP→DRAT steps and, when applicable, exploit treewidth-based dynamic programming [

11,

13].

A registered evaluation protocol with explicit falsifiers and predeclared metrics, consistent with kernelization and sparsification barriers [

8,

9,

10,

11].

We make no universal claims about SAT. All interpretations are local to the registered windows and grounded in publicly checkable artifacts.

The Kernel Architecture (K)

This section makes the kernel K concrete as a per-instance branching set governed by a registered window. We move from normalization (π-rounds) to local obstructions and radius-2 witnesses, assemble K by greedy coverage, and close each branch with a publicly checkable certificate.

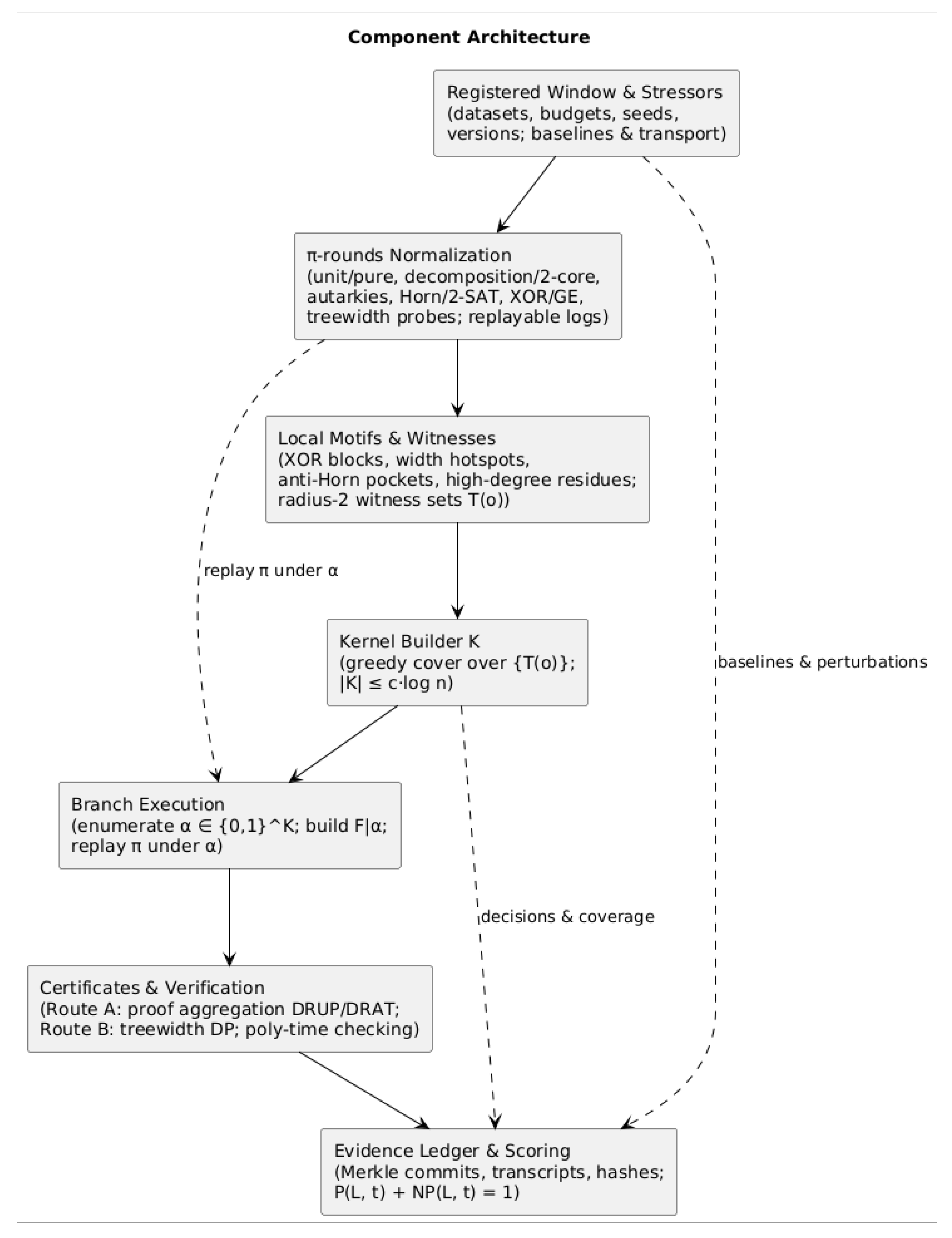

Figure 1 summarizes the components (Normalize → Witness → K → Branches → Ledger) and indicates how each serves H1–H4: polynomial termination per branch, logarithmic size, certificate discipline, and transport under gentle perturbations.

A registered window is the boundary condition. Before anything runs, we fix datasets, budgets, random seeds, toolchain versions, stopping rules, and acceptance criteria. This turns every later number into attributed evidence rather than a one-off result, and it bounds interpretations to the window itself. The same registration anchors stressors (transport perturbations and baselines) so that comparisons have lineage rather than folklore.

Normalization is the first mover. The π-rounds routine iterates familiar passes—unit and pure-literal propagation, component decomposition and 2-core peeling, autarky detection/removal, Horn/2-SAT extraction and consequence folding, XOR lifting via Gaussian elimination, and quick treewidth probes. Each pass writes a replayable log, including RUP fragments when available, so that later proof aggregation is a matter of stitching rather than storytelling. The aim is not to solve but to expose local structure that later steps can name.

Structure becomes operable through a small catalog of local obstructions. After normalization, the formula is read through a finite list of motifs that we expect to recur in practice: XOR clusters, width hotspots, anti-Horn or stubborn 2-SAT pockets, and high-degree residues. The list is provisional by design—easy to extend, easy to prune—because the point is to explain outcomes with compact, nameable reasons rather than to chase universality.

Witness extraction ties motifs to variables. For each obstruction o in the catalog, we compute a tiny witness set T(o) that lives entirely in the radius-2 neighborhood of the motif in the variable–clause incidence graph. The working rule is minimal: one bit in T(o) should dissolve or strictly weaken the obstruction. If that rule fails, the catalog or the radius is wrong—and that failure is useful data for later windows.

The branching set K is assembled greedily over witnesses. Treating the family {T(o)} as a hitting-set instance, we pick variables that cover the most still-unhit witnesses, logging each choice with its marginal coverage and the specific obstructions it disables. We stop when all witnesses are hit or when the budget |K| ≤ c·log n is reached. The goal is not optimality but auditability: every element of K comes with a short, local justification.

Branches are executed with certificates in mind. For each partial assignment α over K, we replay normalization and take one of two constructive routes: Route A aggregates RUP steps and finalizes in DRAT or yields a satisfying assignment; Route B runs dynamic programming when tw(F|α) is small enough and emits bag-to-bag certificates.

Verification is expected to be polynomial in n and m; wall-clock time is secondary to certificate clarity. If both routes fail to produce compact, checkable endpoints, that is a named reason to shift credit to the NP channel.

The evidence ledger closes the loop. Logs from π-rounds, K-construction decisions, branch outcomes, and verifier transcripts are committed to a public ledger (e.g., via Merkle roots and file hashes). Scoring then applies the accounting rule P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1: constructive credit rises only when small K plus normalization yields branchwise polynomial termination with compact, checkable artifacts; otherwise the balance moves to certificate-centric evidence, with the local motifs responsible called out explicitly.

Stressors and baselines keep the story honest. Transport perturbations—variable renamings, community-preserving rewiring, and modest parity injection—test whether reasons travel; no-K and other ablations test whether K actually adds explanatory force beyond strong baselines. If the silhouette collapses under gentle changes, that is a signal to revise the catalog, the witness radius, or the order of π-rounds—not a license to over-generalize from convenient windows.

Privacy-preserving attestations are optional but available. When only aggregate properties should be public (for example, “|K| ≤ c·log n” or “coverage ≥ θ”), zero-knowledge attestations allow claims to be verified without exposing K or run logs. This does not change the reading rule; it widens who can check it.

In short, the architecture turns abstract hypotheses into operable checkpoints: normalization to expose structure, witnesses to localize causes, a small K to make branching feasible, branch routes that end in verifiable artifacts, and a ledger that keeps credit conserved and reasons portable across layers and time.

Definitions and Hypotheses

Let F be a 3-CNF with n = |V(F)| variables and m clauses. All statements below are window-relative: a registered window W fixes datasets, budgets, seeds, toolchain versions, and stopping rules.

Definition 1 (π-round state). One π-round maps a state of F to a new state π(F) while emitting a replayable log of applied simplifications:

degree caps and bounded occurrence pruning;

component decomposition and 2-core peeling;

autarky detection/removal;

Horn / 2-SAT propagation;

XOR lifting and elimination (Gaussian elimination) [

14,

15].

We write π* for iterating π until a fixed point or a budget cap. Logs are required to be sufficient to replay the round and to support downstream proof aggregation.

Definition 2 (kernel K — per-instance branching set). A set K ⊆ V(F) with |K| ≤ c·log n is a valid kernel for F in window W if, for all partial assignments α: K → {0,1}, the restricted instance F ∣ α terminates in time poly(n, m) and emits a publicly verifiable certificate (satisfying assignment or DRAT/DRUP-style proof) [

6,

7]. Certificate verification must also be poly(n, m).Remark. “Kernel” here means a small per-instance branching set, not a parameterized kernelization of the input.

Definition 3 (local obstructions; radius-2 witnesses). After applying π*, an obstruction o is a locally checkable pattern such as: dense XOR blocks, treewidth hotspots, resistant 2-SAT pockets, or high-degree residues. A witness set T(o) is a subset of variables contained entirely in the radius-2 neighborhood of o in the variable–clause incidence graph such that fixing one variable in T(o) dissolves or strictly weakens o.

Quantities for evaluation.

Kernel size: |K| and its scaling with n.

Coverage: fraction of obstructions hit by K (via {T(o)}).

Branch outcomes: SAT/UNSAT mix; presence of certificates; verifier time.

Transport diagnostics: stability of |K| and outcomes under registered perturbations (renamings, rewiring, clause noise).

Hypotheses (falsifiable).

H1 — Branchwise polynomiality. For a nontrivial family of instances in W, a valid K exists.

H2 — Logarithmic size. |K| ≤ c·log n with stable constants c across W.

H3 — Certificate discipline. For every branch α, a checkable artifact (assignment or DRAT/DRUP) is emitted and independently verified in poly(n, m).

H4 — Transport. Under controlled perturbations (renamings, rewiring, clause noise), reasons travel: |K| and termination behavior vary smoothly, and failures admit radius-2 explanations tied to specific obstructions.

Falsifiers (pre-declared). Systematic failure to find such K; super-logarithmic |K|; branches that do not certificate-terminate; verifier failures; or brittle behavior under minimal perturbations that cannot be explained by identified radius-2 obstructions.

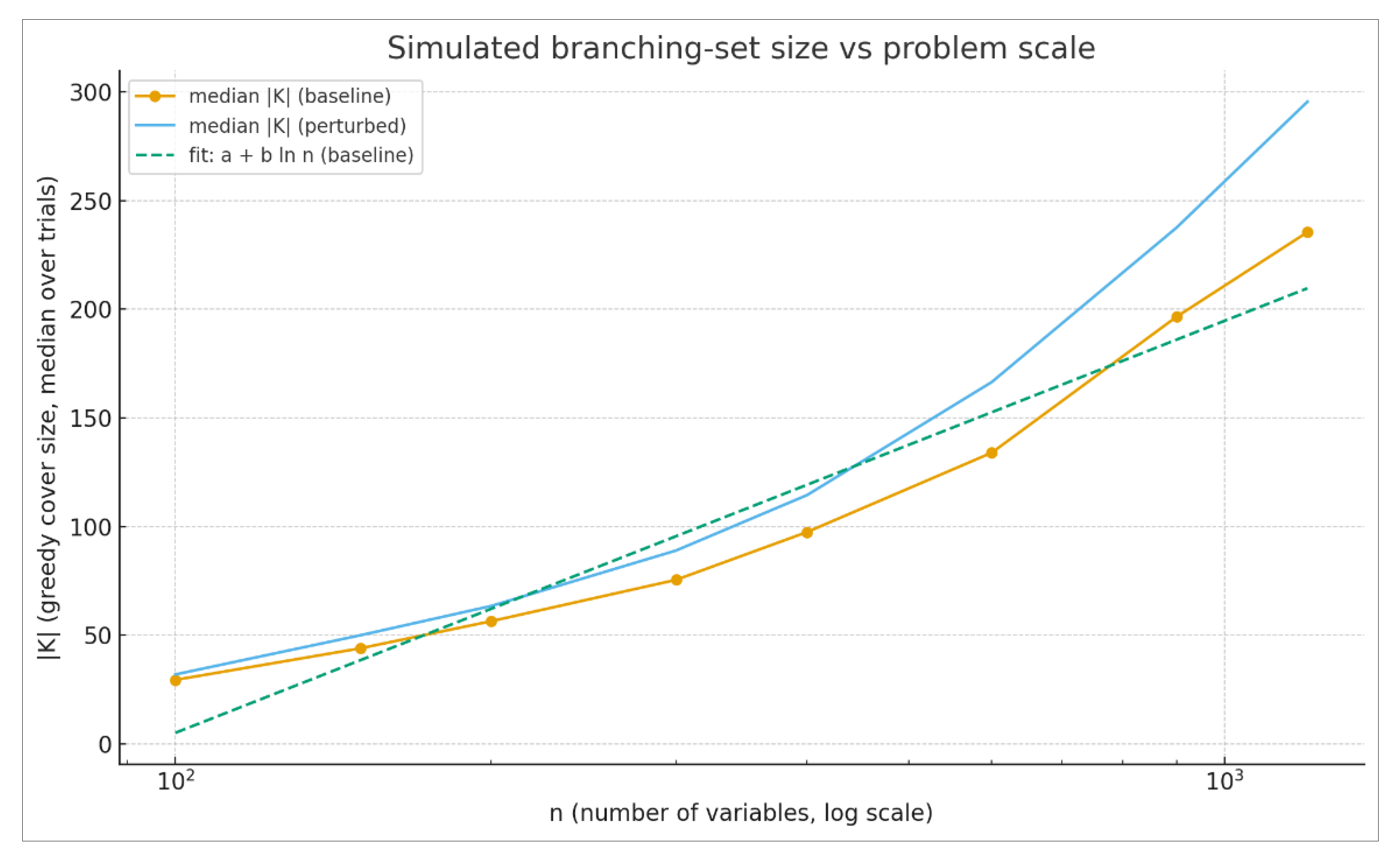

To make the objects and hypotheses tangible, we built a toy simulation that mirrors the intended mechanics without touching real CNFs. Each “obstruction” is represented by a tiny witness set (sizes 1–3) drawn over n variables with a bias toward a few “hotspot” variables, mimicking radius-2 locality.

The kernel K is then assembled by greedy set cover over these witness sets. We read out the median |K| across repeated draws and compare a baseline to a mild “transport” perturbation that randomly swaps one element in a fraction of the witness sets, standing in for renamings/rewiring.

We fit a simple diagnostic curve a + b ln n to the baseline medians. The point is not to prove anything about real instances, but to illustrate the kind of silhouette H1–H4 are about: branchwise tractability suggested by small K (H1), logarithmic scaling (H2), branchwise certification as a reading convention (H3), and stability under gentle perturbations (H4).

Figure 2.

Simulated branching-set size |K| versus problem scale. Median |K| found by greedy set cover over radius-2-style witness sets, plotted against n (logarithmic x-axis). Orange circles: baseline. Blue crosses: perturbed (10% of witness sets have one variable swapped). Dashed line: least-squares fit a + b ln n to the baseline medians. Parameters shown use 12 trials per n, witness sizes in {1, 2, 3}, a popularity bias over variables to emulate hotspots, and n ∈ {100, 150, 200, 300, 400, 600, 900, 1200}. The chart is illustrative only; it does not reflect any real solver or dataset.

Figure 2.

Simulated branching-set size |K| versus problem scale. Median |K| found by greedy set cover over radius-2-style witness sets, plotted against n (logarithmic x-axis). Orange circles: baseline. Blue crosses: perturbed (10% of witness sets have one variable swapped). Dashed line: least-squares fit a + b ln n to the baseline medians. Parameters shown use 12 trials per n, witness sizes in {1, 2, 3}, a popularity bias over variables to emulate hotspots, and n ∈ {100, 150, 200, 300, 400, 600, 900, 1200}. The chart is illustrative only; it does not reflect any real solver or dataset.

Read under our ledger, the baseline curve that tracks ln n is the supportive silhouette for H1–H2: small, slowly growing K suggests that exhaustive branching over K remains polynomial per window, with room for compact certificates.

The perturbed curve sits nearby rather than exploding, which is the transport signal H4 asks for: reasons look local and survive small changes. A counter-pattern would be equally informative—super-logarithmic growth, large sensitivity to tiny perturbations, or divergence between baseline and perturbed curves—indicating that the current obstruction catalog or witness radius is inadequate and that credit should shift to the certificate channel.

Either way, the exercise shows how the definitions (pi-rounds, local obstructions, witness sets, greedy K) translate into concrete diagnostics that can later be applied to real windows without changing the reading rule.

Protocol of Moves: From Normalization to Ledger

We treat normalization as a cyclic, composable pass that advances until a fixed point or a budget cap, while emitting a replayable log suitable for downstream proof aggregation.

In each cycle, the pipeline performs, as the instance demands, unit and pure-literal propagation under bounded degree caps; decomposes the formula into components and peels its 2-core; detects and removes autarkies; extracts Horn/2-SAT regions, solves them, and folds back consequences; lifts parity structure to an algebraic layer and applies Gaussian elimination, re-emitting clauses when needed [

14,

15]; and probes treewidth to obtain fast lower/upper bounds that tag hotspots for later attention [

11,

13]. We write π* for iterating this routine to saturation (or budget exhaustion), and we require the log to be rich enough to replay each transformation and to splice RUP/DRUP fragments into a consolidated DRAT record.

After π*, we interpret the instance through a finite catalog O of locally checkable motifs — dense XOR blocks, treewidth hotspots, anti-Horn or stubborn 2-SAT pockets, and high-degree residues. For each obstruction o ∈ O, we extract a tiny witness set T(o) confined to the radius-2 neighborhood of o in the variable–clause incidence graph, with the property that flipping a single variable in T(o) dissolves or strictly weakens the obstruction. The operating intuition is deliberately minimalistic and testable: one bit collapses the local tangle while preserving explanatory locality.

Given S = {T(o) : o ∈ O}, we assemble the per-instance branching set K by a greedy set-cover pass [

12]. At each step we choose the variable that maximizes coverage of still-unhit witness sets, update coverage, and continue until every T(o) is hit or the budget |K| ≤ c·log n is met. Every pick is recorded with its marginal gain, the obstructions it disables, and the evolving coverage profile, yielding an audit trail that ties kernel elements to concrete, local explanations.

For each α ∈ {0,1}^K we then drive the instance to a certificate along one of two constructive routes. Route A replays π under α, accumulates RUP steps, and finalizes with DRAT-trim to obtain a verifiable UNSAT proof or, when applicable, a satisfying assignment [

6,

7]. Route B invokes treewidth-based dynamic programming when tw(F ∣ α) ≤ c_tw·log n, running in O(m·2^{O(tw)}) and emitting bag-to-bag certificates that can be checked independently [

11,

13]. In both routes, priority is given to certificate compactness and ease of verification — verification itself must be poly(n, m) — rather than raw wall-clock time.

All runs are written to a Merkle-committed ledger that captures π-round logs, K-construction decisions, branch outcomes, and verifier transcripts [

16]. Independent checkers validate DRAT/DRUP proofs and assignment witnesses [

6,

7].

We pre-register datasets, budgets, seeds, toolchain versions, and stopping rules, and we include negative controls — no-K baselines and variable-name shuffles — to test whether reasons travel across perturbations [

1,

9,

10]. When disclosure must be limited to aggregate properties, zero-knowledge attestations can certify claims such as |K| ≤ c·log n or obstruction-coverage levels without revealing K or internal logs [

17].

Register, Measure, Score

A registered window fixes the playing field before any run starts. We pre-declare the datasets, the computational budgets, the random seeds, the stopping rules, and the acceptance criteria; we pin toolchain versions and record cryptographic hashes of all inputs.

This registration is not decoration: it is the boundary condition that turns every subsequent number into evidence with lineage. Within a window, we do not change the rules mid-game.

The windows themselves are chosen to exercise complementary structures. We include curated families of 3-SAT with and without prominent parity structure; synthetic controls where treewidth is manipulated explicitly; and adversarial rewiring stressors that disrupt locality and modularity [

8,

9,

10,

11,

14,

15]. The goal is not to “win everywhere,” but to learn how the reasons behave across regimes: where the normalization pipeline bites, where witness-driven branching pays off, and where barriers hold firm.

Comparisons require baselines that are both capable and fair. We therefore run state-of-practice SAT solvers without any branching set; we run the normalization pipeline alone, without witness-driven kernel construction; and we run treewidth-based dynamic programming in isolation. These baselines anchor the ledger: constructive credit only rises when the proposed kernel adds explanatory power beyond what these references already provide. Measurement follows the objects we defined. First, we track the size of the branching set as a function of problem scale, asking whether |K| grows like log n or drifts upward. Second, we quantify coverage: which listed obstructions are actually hit by the selected variables, and which motifs persist; this is our check that the kernel is not merely small but causally relevant.

Third, we read out the branchwise outcomes: the mix of satisfiable and unsatisfiable conclusions, the presence of certificates in every branch, and the time required by independent verifiers to check them [

6,

7]. Fourth, we estimate total polynomiality by fitting empirical exponents in n to end-to-end effort and by tracking certificate size against n. Finally, we run transport tests: we rename variables, rewire clauses within constraints, or inject parity noise, and we ask whether the size of K, the certificate profile, and the verification cost remain stable or degrade predictably under these perturbations.

Falsification is pre-declared and mechanical. The hypothesis fails when |K| persistently exceeds the logarithmic budget; when branches terminate without a public certificate; when independent verification does not run in polynomial time; or when minimal perturbations produce brittle behavior that cannot be explained by radius-2 witnesses. These triggers are not post-hoc narratives; they are part of the registration.

Statistical handling is deliberately conservative. We compare windows with nonparametric tests; we report effect sizes with bootstrap confidence intervals; and we apply a pre-specified multiplicity control when probing many, correlated readouts [

9,

10]. The emphasis is on robustness to distributional quirks common in solver data, not on squeezing p-values out of heavy-tailed noise.

Scoring closes the loop with the accounting constraint P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1. Within each registered layer and time window, constructive credit rises only when the normalization pipeline plus the selected branching variables yields branchwise polynomial termination accompanied by compact, publicly checkable certificates.

When structure resists, the ledger shifts weight to certificate-centric evidence: longer proofs are still useful if they are auditable and if they explain, via local witnesses, why constructive routes failed here and now.

In this sense the score is a balance, not a verdict, and it is designed to travel across windows rather than to declare a universal law.

Hypothetical Readouts and Evidence Shapes

What follows is purely hypothetical. It sketches how one might read outcomes if registered windows are ever run, without promising data, figures, or artifacts. The reading uses two complementary lenses — one constructive/structure-forward, the other barrier-oriented — and balances credit via the accounting rule P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 [

1].

Under the constructive lens, the imagined narrative borrows the vocabulary of backdoors and islands of tractability. Small sets of variables that steer a formula into Horn, 2-SAT, or other low-width fragments are precisely the kind of “local levers” that could explain why a branching set K stays small and effective; this is the spirit of the seminal backdoor program [

18] and its survey consolidation [

20].

If this lens is apt in a window, one would expect to see silhouettes like |K| tracking log n, witness hits that consistently dissolve local obstructions (XOR clusters, anti-Horn pockets, high-degree residues), and branches that seem to certify via assignment or concise DRAT/DRUP [

6,

7]. Structure found in practice — community/modularity in industrial SAT [

21] — would reinforce the impression: π-rounds are plausibly effective at carving components, radius-2 witnesses remain meaningful, and transport under community-preserving perturbations appears stable. A second constructive thread is bounded treewidth as a route to dynamic programming; if π-rounds or a partial assignment α push tw(F ∣ α) into a low regime, the “Route B” story (DP with bag-to-bag certificates) becomes plausible [

11,

25]. Read this way, a window where these silhouettes recur would credit the P(L, t) channel: constructive reasons seem to dominate, and they do so through local, nameable motifs [

14,

15].

The barrier lens tempers those expectations. Even where engineering is rich, there are provable limits to uniform compression and sparsification. The no-sparsification line [

19] and the sparsification lemma/SETH context [

23] together warn that globally shrinking SAT without unlikely collapses is not to be expected.

Proof-complexity likewise ties proof width to length: narrow proofs are short, but wide necessities force length blow-ups [

22]. Near phase transitions, typical-case hardness and “backbones” can appear, shifting weight away from fast constructive routes [

24]. If this lens is a better fit for a window, imagined readouts would say: |K| appears swollen or unstable; several obstructions persist through π-rounds; certificates appear long (when available); attempts to “shrink” the instance fail in ways consistent with the barriers.

In such a window the ledger shifts credit to NP(L, t): certificate-centric evidence carries the day (and failures are locally explained — dense parity that resists elimination, width hotspots that survive, witness overlap that undermines coverage) [

6,

7,

19,

22,

23].

Between these lenses, the section offers a map of hypothetical silhouettes rather than promises. In structure-friendly windows: |K| ≈ O(log n); branch outcomes consistently seem certified; verification appears to behave polynomially at coarse resolution; and transport under gentle perturbations (renamings, bounded rewiring, light XOR injection) preserves the qualitative picture — an alignment with the backdoor and community narratives [

18,

20,

21].

In structure-resistant windows: |K| seems to exceed the logarithmic regime; some branches lack plausible certification; verification seems to balloon — an alignment with no-go compressions, width/length tradeoffs, and threshold phenomena [

19,

22,

23,

24]. In both cases the common thread is local explainability: when something works, one can point to which element of K neutralized which obstruction; when it does not, one can point to which motif persisted and why the pipeline did not break it [

11,

14,

15,

25].

Interpretation then closes under the same discipline that frames the manuscript: P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1. If a reader recognizes, with [

18,

20,

21,

25], the traces of backdoors, modular structure, and low treewidth, it is natural that P would rise in that window; if they recognize, with [

19,

22,

23,

24], the traces of sparsification limits, resolution width constraints, and threshold hardness, it is natural that NP would carry the balance.

The point here is not to forecast tables or figures but to teach how to read whatever may arise: with two complementary lenses, concrete local motifs, and a conserved-credit rule that keeps the narrative honest.

Limits, Stressors, and Threats to Validity

This is a window-relative program and, by design, vulnerable to specific failure modes. Making them explicit prevents overreach and aligns interpretation with what the literature actually supports.

A first limit is the finite obstruction catalog and its locality prior. By working with XOR blocks, width hotspots, anti-Horn/2-SAT pockets, and high-degree residues, we assume that “levers” live near the motif (radius-2). There are families where causality is more diffuse: long-range interactions, encoding gadgets, or overlapping motifs may require larger radii, breaking the “one bit untangles the knot” narrative.

Even in friendly regimes, the backdoor literature reminds us: small sets may exist and explain typical easiness [

18,

20], but finding and characterizing them can be costly; heuristics risk anecdote, and greedy set cover can pick variables that are incidentally correlated rather than causally central.

The algebraic channel brings its own fragilities. XOR lifting and Gaussian elimination can improve normalization, but their marriage to CNF is delicate: clause re-emissions can inflate instances and mask structure [

14,

15]. With dense parity or XOR interwoven with clauses, the algebraic pass may “paint over” exactly the motif we aim to measure, confusing witness coverage.

On the width channel, our routes depend on treewidth estimates. Exact tw is hard; fast bounders are coarse; and DP with O(m·2^{O(tw)}) carries large constants [

11,

25]. A window that “looks polynomial” may do so because of loose bounds or scales too small to separate regimes. Conversely, hostile windows — near phase transitions and with “backbones” — tend to punish both propagation and DP [

24]; reading a universal no there would ignore their nature as typical hard cases. Proofs impose their own sanity checks. The width↔length tradeoff for Resolution [

22] explains why certificates can blow up even when normalization looks promising: if required width is high, length inflation is inevitable. In practical formats (DRUP/DRAT) [

6,

7], this shows up as long traces with limited didactic value, shifting credit to NP(L, t) — and that shift, by itself, does not license strong claims about intrinsic hardness.

Theoretical guardrails must remain in view. The no-sparsification line [

19] and the sparsification lemma/SETH context [

23] indicate that broad compressions are not a reasonable target without unlikely collapses. Therefore any observation of “compressibility” (small |K| with universal branch certification) is, by principle, local to the window. Likewise, community structure in industrial SAT [

21] can be domain- and encoding-specific; swapping encodings may erase effects that previously looked robust.

There are also mundane bias sources: dataset choices that favor one mechanism; π-round ordering that privileges a motif; unfixed seeds and tie-breaking; implementation variance in checkers and DRAT-trim [

6,

7]. Without registration, these become “engineering magic.” Even with registration, separating real structure from pipeline effects requires ablations: remove/reorder passes, swap tw bounders, vary encodings, test community-preserving rewiring [

21], and inject controlled parity.

Real comparisons set the tone for humility. Backdoors [

18,

20] and bounded width [

25] sustain hope for constructive islands (and guide where to look for K); sparsification limits and proof tradeoffs [

19,

22,

23] sustain skepticism about uniform promises (and guide when to shift credit to NP).

This section does not deny local wins — it asks that they be read as local; it does not mortgage defeats — it asks that they be read as data. In all cases, the balance P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 keeps the narrative aligned: credit moves, but is conserved; what travels are not slogans but nameable reasons.

Conceptual Bridges to Existing Notions

The kernel K in this manuscript is an operational, per-instance branching set — small enough to enumerate (|K| ≤ c·log n), chosen to break local obstructions, and judged by whether every branch ends in a publicly checkable certificate (assignment or DRUP/DRAT) within a registered window. Read this way, K sits at the crossroads of four well-developed traditions; the bridges below clarify what K is and, just as importantly, what it is not.

Backdoors. The closest kin to K are backdoor sets: small variable sets that steer a formula into a tractable subtheory (Horn, 2-SAT, etc.), either for every assignment (strong) or for some assignment (weak) [

18,

20]. Our K borrows the spirit but not the contract. It is window-relative and catalog-relative: variables are selected because radius-2 witnesses show they dissolve explicit local motifs (XOR clusters, low-width pockets, anti-Horn fragments, high-degree residues), not because F|α lands in a fixed tractable class.

The demand is different: all branches must certificate-terminate, regardless of whether the restricted instance is Horn/2-SAT or merely rendered certifiable by π-rounds and proof logging [

6,

7]. Where classical backdoors exist, K will often intersect or subsume them; where they do not, K can still succeed by unwinding local structure without promising global membership in an easy fragment.

Width measures. Bounded treewidth and related parameters explain islands where dynamic programming is effective [

11,

25]. Our “Route B” leverages exactly that: if π-rounds and a partial assignment α push tw(F|α) to O(log n), bag-wise DP becomes plausible and can emit bag-to-bag certificates. The bridge matters in both directions. When width hotspots are present, K acts as a pressure valve: it targets variables whose fixing lowers local width enough to flip DP from intractable to workable.

When required width remains high, the Ben-Sasson–Wigderson tradeoff [

22] reminds us why proofs may grow: large width demands long proofs, shifting credit from P to NP in our ledger rather than inviting over-interpretation.

Kernelization (parameterized). Despite the name, our K is not a kernel in the parameterized sense. We do not claim a polynomial-time compression of an arbitrary SAT instance to an equivalent one of size bounded by a parameter; we avoid precisely the terrain ruled out by no-sparsification and cross-composition barriers [

9,

19,

23]. The distinction is sharp: parameterized kernelization asks for uniform instance shrinkage under reductions; our K is a branching set that structures search locally and is evaluated per window by certificate behavior. Any positive patterns (for example, |K| behaving like O(log n)) are, by construction, local and do not contradict sparsification limits [

19,

23].

Proof systems. The grammar of evidence here is proof-centric: branch outcomes are read through DRUP/DRAT certificates and simple assignment checkers [

6,

7]. π-rounds are designed to leave proof hooks (RUP fragments) that aggregate into DRAT; when DP is used, bag transitions can be logged to yield independently checkable traces. Proof-complexity provides the interpretive scaffolding: short, narrow proofs align with constructive wins; width-driven length inflation [

22] explains why some branches resist compaction and why the ledger should credit the NP channel without conflating long proofs with global hardness.

What K is / is not (concise). Is: a small per-instance branching set, assembled from local witnesses, whose success criterion is universal branch certification within a window; a reading device for where constructive structure lives (backdoors, width pockets, XOR motifs) [

11,

18,

20,

25], and where it does not. Is not: a parameterized kernelization or any claim of uniform compression [

19,

23]; a guarantee of global polynomial-time solvability; a vehicle for class separation.

These bridges do the integrative work. Backdoors and community/width structure suggest where K can be short and explanatory; sparsification and width-length tradeoffs set how far such behavior can generalize and why certificates may swell [

19,

21,

22,

23].

With the accounting rule P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 in the background [

1], the upshot is a disciplined reading: K concentrates reasons — constructive when it can, proof-centric when it must — without overstepping what the existing theory and practice genuinely support.

Future Work

The most immediate path is to widen the obstruction ecology without abandoning locality. The present catalog — XOR clusters, width hotspots, anti-Horn or stubborn 2-SAT pockets, high-degree residues — was chosen because it is legible and radius-2 friendly.

It is natural to ask whether other recurrent motifs deserve entry (for example, backbone fragments near thresholds, community bottlenecks in industrial encodings, or gadgets tied to specific reductions) and whether they still admit witness sets that sit inside small neighborhoods. If repeated counter-patterns suggest that causal “handles” live beyond two hops, one could explore an adaptive radius that defaults to 2 but expands in controlled, auditable ways.

A second thread is to rethink how K is assembled. Greedy set cover is attractive for its transparency, but overlap among witness sets can make it myopic. Alternatives that penalize redundancy, emphasize stability under perturbations, or optimize a multi-objective score (coverage, compactness, and explanatory clarity) could change the quality of K in ways that matter for transport. On small instances, exact or integer-program oracles could serve as ground truth to calibrate heuristics; on larger ones, submodular surrogates might strike a better balance between coverage and interpretability.

Interfaces between normalization, proofs, and structure deserve a third line of attention. On the algebraic side, one can refine the handshake between XOR lifting and clause reasoning so that elimination helps rather than hides the very motifs we measure.

On the graph side, better lower and upper bounds for treewidth would reduce ambiguity in when to trigger the dynamic-programming route, and bag-to-bag certificate templates could be standardized so that proof logging is not an afterthought but an integral output. More generally, π-rounds can be designed to leave proof hooks by construction, easing later aggregation into DRUP or DRAT.

A fourth direction is to extend transport beyond micro-perturbations. The present narrative imagines renamings, bounded rewiring, and mild parity injection; future windows could vary encodings of the same combinatorial source, swap solver families (CDCL, look-ahead, local search), and diversify proof formats (DRUP, DRAT, LRAT, FRAT) to check whether credited reasons keep traveling when the plumbing changes. The same question applies across adjacent territories: MaxSAT, CSP fragments, and bounded-width graph problems offer natural testbeds where a branching set in the sense of this paper may or may not emerge with the same balance.

There is also theory at the right resolution to be written. Without reaching for class separations, one can formulate local theorems — for example, conditions under which a logarithmic-size branching set exists with high probability in planted or modular ensembles; relationships between K and known parameters such as strong or weak backdoors and structural widths; or no-go statements explaining why a given witness radius or catalog cannot succeed on certain distributions without conflicting with known lower bounds. These statements match the granularity of the accounting rule: they tell us where constructive credit can plausibly accumulate and where the certificate channel should rightfully dominate.

Moreover, governance itself can mature into a research object. As windows diversify, registration will matter more: minimal schemas for budgets, seeds, stopping rules, and falsifiers; lightweight conventions for declaring how P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 is operationalized in reports; and narrative norms for writing down failures so that they refine the catalog rather than disappear into engineering folklore.

None of this promises delivery; it traces a map of questions whose answers, supportive or not, would still count as evidence that travels.

Participation and Commons: Making the Problem for Everyone

Complexity talk often congeals into guild knowledge: dense notation, bespoke tooling, tacit norms. A hypothesis-first program does not have to inherit that posture. If the goal is evidence that travels, then participation must travel too.

This section sketches how the same ideas — local witnesses, branching sets, certificate-first reading — can be framed so that a high-school club and a graduate seminar both find a task at the right scale.

The first lever is low-cost windows. Choose problem sizes, budgets, and tools that fit a modest laptop and a short session. Prefer checkers a newcomer can run without compiling a solver stack. When a window asks for a contribution, phrase it as “show a radius-2 witness that dissolves this motif” rather than “beat the leaderboard.” Because the accounting rule P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 gives credit to constructive routes and to certificate routes alike, a clear explanation or a small, well-formed certificate counts as much as a speedup.

The second lever is explainability as a first-class output. Introduce “witness cards”: one-page notes that name a local obstruction (XOR cluster, width hotspot, anti-Horn pocket, high-degree residue), draw its radius-2 neighborhood, and show how flipping a single variable changes the story. Pair them with “proof postcards”: short, human-readable summaries of why an assignment satisfies or a DRAT trace certifies unsatisfiability. These artifacts teach first and only then refer to heavier logs or traces.

The third lever is language and scaffolding. Publish a tiny glossary that fixes the paper’s meanings: kernel here means branching set K, not parameterized kernelization; radius-2 means two steps in the variable–clause graph; π-rounds means the specific normalization passes in plain words. Add walk-throughs of toy formulas that show, step by step, what each pass does and how a witness is extracted. Use diagrams generously, but keep them semantic rather than tool-specific.

The fourth lever is many ways to help. Not everyone has to write code or engineer proofs. Roles can include designing toy windows, curating or translating glossaries, crafting community-preserving perturbations for transport tests, writing clearer witness cards, or auditing explanations for ambiguity. The ledger view makes this natural: different roles move credit between the constructive and certificate channels, and all of them leave reasons that others can reuse.

The fifth lever is light but firm governance. Set simple etiquette (civility, attribution, no gatekeeping). Allow pseudonyms so beginners can try, err, and try again.

Keep windows short and rhythmic so that classrooms and meetups can join without long commitments. Favor versioned notes over locked-down PDFs so that improvements to explanations propagate.

The final lever is equity by design. Avoid assumptions about bandwidth, language, or prior exposure. Offer printable witness cards and plain-text instructions that survive low connectivity. Encourage translations and side-by-side bilingual glossaries. Where examples require data, prefer small, permissively licensed instances that can be shared freely.

None of this changes the mathematics. It changes who feels entitled to touch it. If we take participation seriously, the hypothesis becomes a commons: reasons are small enough to name, artifacts are simple enough to teach, and the balance P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1 is not just an accounting device but a social one — one that makes room for many kinds of contribution to count.

Conclusion

This manuscript argues for reading SAT not through a verdict but through a ledger of reasons. The organizing rule is simple and conservative: P(L, t) + NP(L, t) = 1.

In any registered layer and window, constructive credit rises only when small, local choices lead to branchwise polynomial termination with publicly checkable certificates; when structure resists, the balance shifts to the certificate channel, and the failure is explained locally rather than narrated away [

1]. Everything else in the paper — definitions, pipeline, motifs, branching set K, scoring — exists to keep that accounting honest and portable.

Concretely, we proposed a per-instance branching set K (|K| ≤ c·log n) as a test object: not a parametric kernel; not a compression claim; simply a small set that structures exploration and connects decisions to verifiable artifacts.

The pipeline around K is deliberately orthodox. It cycles through unit and pure-literal propagation, decomposition and 2-core peeling, autarkies, Horn/2-SAT extraction, and an algebraic lift for XOR via Gaussian elimination — moves that the SAT community already trusts in practice [

14,

15] and that pair naturally with certificate formats such as DRUP/DRAT and their checkers [

6,

7].

When a branch appears to land in a low-width region, the second constructive route is treewidth-based dynamic programming with bag-to-bag certificates, aligning with classic and modern results on width-parameterized algorithms [

11,

13,

25]. The greedy set-cover assembly of K is chosen for auditability: each picked variable is tied to a radius-2 witness and a concrete obstruction it dissolves [

12].

Interpretively, the program is anchored to two literatures that often speak past each other. On the constructive/structure side, backdoors and islands of tractability suggest that small sets can explain practical easiness; this is the core intuition of Williams–Gomes–Selman and subsequent surveys that unify strong/weak backdoors and their role in typical-case behavior [

18,

20]. Industrial SAT adds a second structural signal: community/modularity and near-decomposability, which give π-rounds a natural target and make witness locality plausible [

21].

On the barrier side, lower-bound programs explain why uniform dreams should be tempered. No-sparsification and cross-composition tell us not to expect general compressions or polynomial kernels for SAT without unlikely collapses of the hierarchy [

9,

19]; the sparsification lemma and the ETH/SETH landscape articulate when even disjunctions of sparse instances do not buy polynomiality at scale [

23]. Proof-complexity puts teeth on the certificate channel: the width–length tradeoff in Resolution says that wide inferences demand long proofs, so certificate blow-ups can be principled rather than accidental [

22]. Typical-case studies near the phase transition warn that backbones and long-range correlations can emerge precisely where one might hope for locality [

24]. Our stance is to integrate these streams: K concentrates constructive reasons when they exist and, when they do not, the ledger moves credit to NP with named, local causes rather than with generic claims.

This stance is deliberately modest with respect to classical complexity. We fully acknowledge the ambition and reach of the foundational program that linked NP-completeness, reductions, and proof systems [

2,

3,

4,

5]; nothing here undermines those lines or claims to solve their central open questions.

Instead, our hypotheses are window-local and artifact-first: a reader is invited to ask whether, in this bounded regime, reasons travel across perturbations; whether small K’s recur; whether certificates remain compact; and, symmetrically, whether counter-patterns recur in a way that is stable and explainable. Either outcome is informative under the same accounting rule [

1].

Two design choices protect the interpretive discipline. First, registration fixes datasets, budgets, seeds, stopping rules, and toolchain hashes before any run, so that later numbers have lineage rather than luster. Second, locality is not a slogan but a contract: every kernel element is justified by a radius-2 witness attached to an explicit obstruction (XOR cluster, width hotspot, anti-Horn pocket, high-degree residue). If that contract fails — if witnesses must sprawl or if obstructions do not explain outcomes — the program learns that its catalog or radius is wrong and shifts credit accordingly. In practice, this is where cryptographic commitments and optional zero-knowledge attestations can help: they let one publish claims about sizes, coverage, and verification without overexposing internal traces, while preserving independent checkability [

16,

17].

The value of publication, then, is not a promise of universal performance but a way to make progress legible. When K is short and certificates are compact, we know which local structures carried constructive credit — backdoors and modularity in the sense of [

18,

20,

21], low width in the sense of [

11,

25], algebraic lift in the sense of [

14,

15] — and we can ask whether those reasons survive renamings or controlled rewiring. When K swells or proofs balloon, we learn which barriers are active — no-go compressions [

19], sparsification limits [

23], width-driven blow-ups [

22], threshold effects [

24] — and we can write down where the constructive route lost traction.

In both cases, the ledger makes the narration conservative: credit moves, but is conserved, and what travels are named reasons rather than one-off wins.

The program maintains a clear boundary with parameterized kernelization: despite the shared word, our K is not an instance compression and does not touch the terrain fenced off by cross-composition lower bounds [

9] or by no-sparsification results [

19].

Positive silhouettes — |K| behaving like O(log n), universal branch certification with polynomial verification — are explicitly local to the registered windows and coexist with the known limits [

8,

9,

10,

19,

23]. Negative silhouettes are data rather than defeat: they refine the obstruction catalog, the π-rounds order, or the choice of windows.

In sum, the contribution is a small test object (K) and a discipline for reading it. The mechanics are familiar (π-rounds, DRUP/DRAT, XOR/GE, treewidth DP), the hypotheses are falsifiable, and the interpretation is moored to the comparative literatures that define the field.

If this approach proves productive, it will be because the reasons it surfaces travel across layers and time; if it fails, it will fail specifically, in a way that names the local structures and barriers responsible.

Either way, it enriches the conversation by replacing verdicts with portable evidence — the kind of evidence the community already knows how to check and the theory already knows how to bound.

License and Declarations

License. © 2025 Rogério Figurelli. This preprint is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) and adapt (remix, transform, and build upon the material) for any purpose, even commercially, provided that appropriate credit is given to the author. A link to the license and an indication of any changes made must be included when reusing the material. The full license text is available at:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Author Contributions:This work was conceived, structured, and written in full by Rogério Figurelli. No other authors qualify for authorship under the ICMJE recommendations. Contributions from institutions, collaborators, or organizations that supported background research, data organization, or conceptual framing are acknowledged separately in related project documentation.

Data Availability: No proprietary or sensitive datasets were used in the preparation of this manuscript. All conceptual models, equations, and figures were generated as part of the author(s)’ own research process. Any supplementary materials, such as simulation data, analytical scripts, or graphical code used to produce figures, are available upon request and may be deposited in an open-access repository in accordance with FAIR data principles. Authors encourage reuse and adaptation of such resources, provided appropriate credit is given.

Ethics Statement: This research does not involve experiments with humans, animals, or plants and therefore did not require ethics committee approval. The work is conceptual, methodological, and computational in scope. Where references to decision-making domains such as healthcare, finance, and retail are made, they serve as illustrative vignettes rather than analyses of proprietary or sensitive datasets.

Acknowledgments: The author(s) acknowledge prior foundational work and intellectual contributions that have shaped the conceptual and methodological background of this manuscript. Relevant influences include advances in causal reasoning and modeling, developments in artificial intelligence safety and governance, insights from decision sciences and behavioral theories, reinforcement learning frameworks, and broader discussions in information ethics. The author(s) also recognize the value of open-innovation initiatives, collaborative research environments, and public knowledge projects that provide resources, context, and inspiration for ongoing inquiry. Visualizations, figures, and supporting materials were prepared using openly available tools and may have benefited from institutional or laboratory collaborations aimed at promoting reproducibility and transparency.

Conflicts of Interest:The author declares no conflicts of interest. There are no financial, professional, or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence or bias the work presented.

Use of AI Tools: AI-assisted technology was used for drafting, editing, and structuring sections of this manuscript, including the generation of visual prototypes and narrative expansions. In accordance with Preprints.org policy, such tools are not considered co-authors and are acknowledged here as part of the methodology. All conceptual contributions, final responsibility, and authorship remain with the author, Rogério Figurelli.

Withdrawal Policy: The author understands that preprints posted to Preprints.org cannot be completely removed once a DOI is registered. Updates and revised versions will be submitted as appropriate to correct or expand the work in response to community feedback.

References

- R. Figurelli, “What if P + NP = 1? A Multilayer Co-Evolutionary Hypothesis for the P vs NP Millennium Problem,” Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Cook, “The complexity of theorem-proving procedures,” in Proc. STOC, 1971.

- R. M. Karp, “Reducibility among combinatorial problems,” in Complexity of Computer Computations, 1972.

- S. A. Cook and R. A. Reckhow, “The relative efficiency of propositional proof systems,” J. Symbolic Logic, 1979. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Robinson, “A machine-oriented logic based on the resolution principle,” J. ACM, 1965. [CrossRef]

- M. J. H. Heule, “The DRAT format and DRAT-trim checker,” arXiv:1610.06229, 2016.

- M. J. H. Heule, A. Biere, and F. Bacchus, “Trimming while checking clausal proofs (DRUP),” in Proc. FMCAD, 2013.

- D. Lokshtanov, N. Misra, and S. Saurabh, “Kernelization — Preprocessing with a Guarantee,” 2012.

- H. L. Bodlaender, B. M. P. Jansen, and S. Kratsch, “Kernelization lower bounds by cross-composition,” SIAM J. Discrete Math., 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Dell and D. van Melkebeek, “Satisfiability allows no nontrivial sparsification unless the polynomial-time hierarchy collapses,” in Proc. STOC, 2010.

- H. L. Bodlaender, “A linear-time algorithm for finding tree-decompositions of small treewidth,” SIAM J. Comput., 1996. [CrossRef]

- V. Chvátal, “A greedy heuristic for the set-covering problem,” Math. Oper. Res., 1979. [CrossRef]

- E. Eiben, R. Ganian, and S. Ordyniak, “A hybrid approach to dynamic programming with treewidth,” Proc. MFCS, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Soos, “Enhanced Gaussian elimination in DPLL-based SAT solvers,” 2010.

- C.-S. Han and J.-H. R. Jiang, “When Boolean satisfiability meets Gaussian elimination in a simple way,” in Proc. CAV, 2012.

- R. C. Merkle, “A digital signature based on a conventional encryption function,” in Proc. CRYPTO, 1987.

- Goldreich, “Zero-knowledge twenty years after its invention,” J. Cryptology, 2002.

- R. Williams, C. P. Gomes, and B. Selman, “Backdoors to Typical Case Complexity,” in Proc. IJCAI, 2003.

- 19. H. Dell and D. van Melkebeek, “Satisfiability Allows No Nontrivial Sparsification Unless the Polynomial-Time Hierarchy Collapses,” in Proc. STOC, 2010; journal version in J. ACM, 61(4):23, 2014.

- S. Gaspers and S. Szeider, “Backdoors to Satisfaction,” in The Multivariate Algorithmic Revolution and Beyond (LNCS 7170), Springer, 2012, pp. 287–317.

- C. Ansótegui, M. L. Bonet, J. Giráldez-Cru, J. Levy, and L. Simon, “Community Structure in Industrial SAT Instances,” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 64, pp. 1–32, 2019 (preprint 2016). [CrossRef]

- E. Ben-Sasson and A. Wigderson, “Short Proofs Are Narrow — Resolution Made Simple,” Journal of the ACM, 48(2):149–169, 2001.

- R. Impagliazzo and R. Paturi, “On the Complexity of k-SAT,” Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 63(4):512–530, 2001; see also R. Impagliazzo, R. Paturi, and F. Zane, “Which Problems Have Strongly Exponential Complexity?,” JCSS, 63(4):512–530, 2001 (Sparsification Lemma context). [CrossRef]

- R. Monasson, R. Zecchina, S. Kirkpatrick, B. Selman, and L. Troyansky, “2+p-SAT: Relation of Typical-Case Complexity to the Nature of the Phase Transition,” Random Structures & Algorithms, 15(3-4):414–435, 1999.

- M. Samer and S. Szeider, “Constraint Satisfaction with Bounded Treewidth Revisited,” Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 76(2):103–114, 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).