1. Introduction

According to Doswell et al. (1996) [

1] and Johns and Doswell (1992) [

2], the three necessary ingredients for deep convection are: (1) a conditionally unstable environmental lapse rate; (2) sufficient moisture (a deep moist layer at low levels) to produce a level of free convection (LFC) along a moist adiabat from a rising parcel; and (3) a lifting mechanism capable of raising the parcel to its LFC. Multiple convection triggers exist, such as fronts, outflow boundaries, sea-breeze fronts, dry lines, and topography [

1,

3]. Weckwerth and Parsons (2006) [

4] added to these elements’ horizontal convective rolls and solitary waves. Most of these triggers play a similar role to topography, but with the difference that they involve motion [

5].

The interaction between topography and the previously mentioned factors can enhance the triggering strength [

6]. Therefore, deep convection can occur in weakly to moderately unstable environments when orography (or other factors) helps trigger the air mass. Moreover, new thunderstorms that develop after the first convection initiation in mountainous regions often produce heavier precipitation and other severe weather phenomena [

7]. [

8] showed that the combination of mountain size and thermal forcing are the main ingredients controlling precipitation amounts, while [

9] added another factor: the wind profile. Regarding thermal forcing, [

10] observed that convection often initiates over or downwind of the mountain crest during diurnal convection, due to thermally driven circulation—results that coincide with those of [

11]. These authors provided an interesting summary of the types of convection initiation associated with topography, including mechanical causes (direct orographic lifting, upstream blocking, lee-side convergence, and mountain waves) and thermally driven circulations (daytime and nighttime flows).

Most of the previously cited research was carried out using weather radar combined with other sources (numerical weather models, air soundings, automatic weather stations, among others). Therefore, weather radar has become the primary tool for understanding convection initiation in orographic environments [

7,

9,

10].

Many previous works studied this region from a meteorological point of view, but with different objectives. For instance, [

12] showed that heavy rainfall events occur in this area when moisture flow interacts with the orography, favoring high values of precipitation exceeding 100 mm in 24 hours. Then, it is not a surprise that flood events are usual in all the parts of the Pyrenees, but according to [

13], they are more common in the eastern part. It is important to bear in mind that heavy rainfall events in this area have a return period of only 5 years for cases with daily cumulation over 150 mm [

14]. These authors observed two different behaviors of precipitation patterns over the Pyrenees, depending on the area most affected: western or eastern Pyrenees. Of the nine weather type patterns, seven produce more than 25 mm in mean in some places of the eastern Pyrenees. However, there are large differences between the precipitation distribution depending on the pattern. Nevertheless, one common feature is that the maximum is located close to a region shaped by the topography and the maritime flow. [

15] compared thunderstorms that occurred in the Pyrenees (in the central part, west of our study area) with those that developed over the surrounding plain. They observed a slower motion of the cells growing over the mountains, and, besides they had a shorter trajectory than those forming in flat areas. So, the topography does not only play a major role in the formation of thunderstorms, but also in the other parts of the life cycle. Furthermore, the Pyrenees not only influence over small and medium thunderstorms systems, if not contribute to the life cycle of large Mesoscale Convective Systems (MCS) over the French plains [

16]. This result is coincident with the obtained by [

17] for MCS occurring over northern Africa or by [

18] for the Andes region. In this way, the influence of the topography over the convection cycle is not only over the initiation stage, if not in other phases.

[

19] was probably one of the first referenced studies of the convection in the eastern Pyrenees, focusing on the analysis with numerical model and radar of thunderstorms cases occurring under anticyclonic conditions and relative stability. They found a high correlation between the occurrence and the diurnal cycle, caused by the interaction between the topography with the breeze, which introduces a complementary moist contribution in the Eastern part of the region. On the other hand, the Western part received less extra maritime humidity, because of the larger distance to the sea. These results coincide with the found by [

14] using backward trajectories. [

20] observed a peak of lightning activity in the eastern Pyrenees during the summer, mainly in June, while at the end of August the activity in this area decreased and moved to the Catalan coastal region.

Vilar and Rigo (2022) [

21] -hereafter, VR22- made a preliminary analysis of convection initiation using radar imagery, but focusing exclusively on the first initiation in each event. That study was the first systematic analysis using weather radar in an orographic region and only analyzed the first daily convection initiation in the Pyrenees. The results revealed that the eastern part of the Pyrenees massif, with high altitudes but closest to the sea, is the area with the most initiations. However, we observed that in most events, there were one or multiple secondary initiations, which occurred close to or far from the first one. Therefore, the motivation for this manuscript is to develop an objective methodology for improving the identification of all convective initiations using weather radar data.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. The Area of Study

The Pyrenees are the most important orographic system on the Iberian Peninsula (

Figure 1), forming a natural border between it and the rest of Europe. Geographically, they stretch from Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean to the Bay of Biscay on the Atlantic, with a total length of over 400 km. Geologically, the Pyrenees extend for about 1,000 km, continuing into the Basque Mountains and the Cantabrian Mountains. Several peaks exceed 3,000 m, with the highest point at 3,404 m. The valleys are mostly oriented north–south, with a distinctive orographic feature: the northern flank of the range has a steeper slope than the southern one.

This study focuses on the eastern half of the Pyrenees range from a broad geographical perspective. It also includes the Pre-Pyrenees —mountain ranges attached to both sides of the axial Pyrenees— and some adjacent ranges and lands, such as the Catalan Transversal Range (5), to provide a more regular delimitation of the study area. Thus, the entire eastern half of the Pyrenees is considered, covering an east–west length of about 220 km, from Cap de Creus (1) in the east to the Pique (N)–Benasque (S) valleys (2, 3) at the western limit. We have aimed to preserve the unity of the main massifs, such as the prominent Maladeta Massif (4).

2.2. Data Used

The primary data source for this research is the composite radar from XRAD (the radar network of the Meteorological Service of Catalonia). It consists of four radars distributed to provide short-range coverage of the Catalan territory (see

Figure 1). Only a small area in the northwestern part is not included in this coverage. Short-range coverage (between 130 and 150 km, depending on the radar) is a 3D field that allows highly precise observation of the vertical distribution of precipitation structures. It is very useful for nowcasting and surveillance purposes. In contrast, the long-range field consists of a single elevation (0.6º) PPI (Plan Position Indicator) covering distances up to 240 km from the radars. This product is useful for detecting distant precipitation structures moving toward Catalonia. Both the short- and long-range fields have a temporal resolution of 6 minutes, and the pixel size is 1 km in both axes.

As shown in

Figure 1, part of the study area (the red dashed rectangle) lies outside the short-range coverage. Therefore, it is not possible to use the 3D fields systematically. For this reason, we relied on the planar long-range product to identify convection initiation points. However, volumetric images were also used for complex events to assess the probability of a new convection case and to extrapolate the results to other events.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present examples of each data type for the same time. Volumetric data allows for a better understanding of the processes occurring within thunderstorms and their interactions with the surrounding environment. However, these data are more challenging to process and require longer computational times.

Weather radar data have some limitations over complex topographical regions such as the one considered in this study. Beam blockage (the partial or total occultation of the radar beam caused by the presence of a mountain along the beam path [

22]) is the main issue affecting radar data in these areas. Beam blockage can affect one or more beam elevations, and the angle of occultation depends on the distance of the obstacle to the radar. Other limitations under these conditions have also been reported by [

23]. Nevertheless, VR22 demonstrated that deep convection (thunderstorms with strong vertical development) is well detected in the study area. Therefore, radar limitations are minimized in the present study, as we consider echoes exceeding the 45 dBZ threshold, which is commonly associated with convection [

24].

2.3. Methodology

Figure 4 illustrates the methodology used in this study. The method is structured as a sequence of questions; depending on each answer, the process advances to the next step:

-

Is there any reflectivity pixel exceeding 45 dBZ?

As explained previously, the selection of this threshold is based on the bibliography on convective events in the region [

24].

- −

If not, the procedure waits for the next image (6 minutes later).

- −

If yes, it moves to the next question.

-

Has the 45 dBZ area reached a size larger than a given threshold?

- −

If not, the procedure waits for the next image.

- −

If yes, the script proceeds to the next step.

-

Are there any pixels exceeding 45 dBZ in any of the previous Ni images (where Ni is the number of previous images)?

- −

If not, the 45 dBZ area in the current image is classified as convection initiation.

- −

If yes, more questions must be addressed.

-

Is the distance between the two convective cells (current and previous) lower than a given threshold?

- −

If not, the current 45 dBZ area is considered a new convective cell.

- −

If yes, continue with the next question.

-

Is there any reflectivity pixel between the two peaks exceeding a certain threshold?

- −

If not, the cell in the current image is considered independent from the previous one, and therefore classified as a new convection initiation.

- −

If yes, the process stops and waits for the next image.

The algorithm was applied to all valid events (see definition at the end of this section) during the 2022–2024 period, considering only the summer months (June to August). Because the focus is on diurnal convection (which is more closely related to orography), only the daytime period (08:00–20:00 UTC) was analyzed. Consequently, although more convective days occurred in the study region during the analysis period, some were excluded because their convection had a different nature: in some cases, it was nocturnal (not driven by solar forcing), while in others the thunderstorms developed elsewhere and later moved into the eastern Pyrenees.

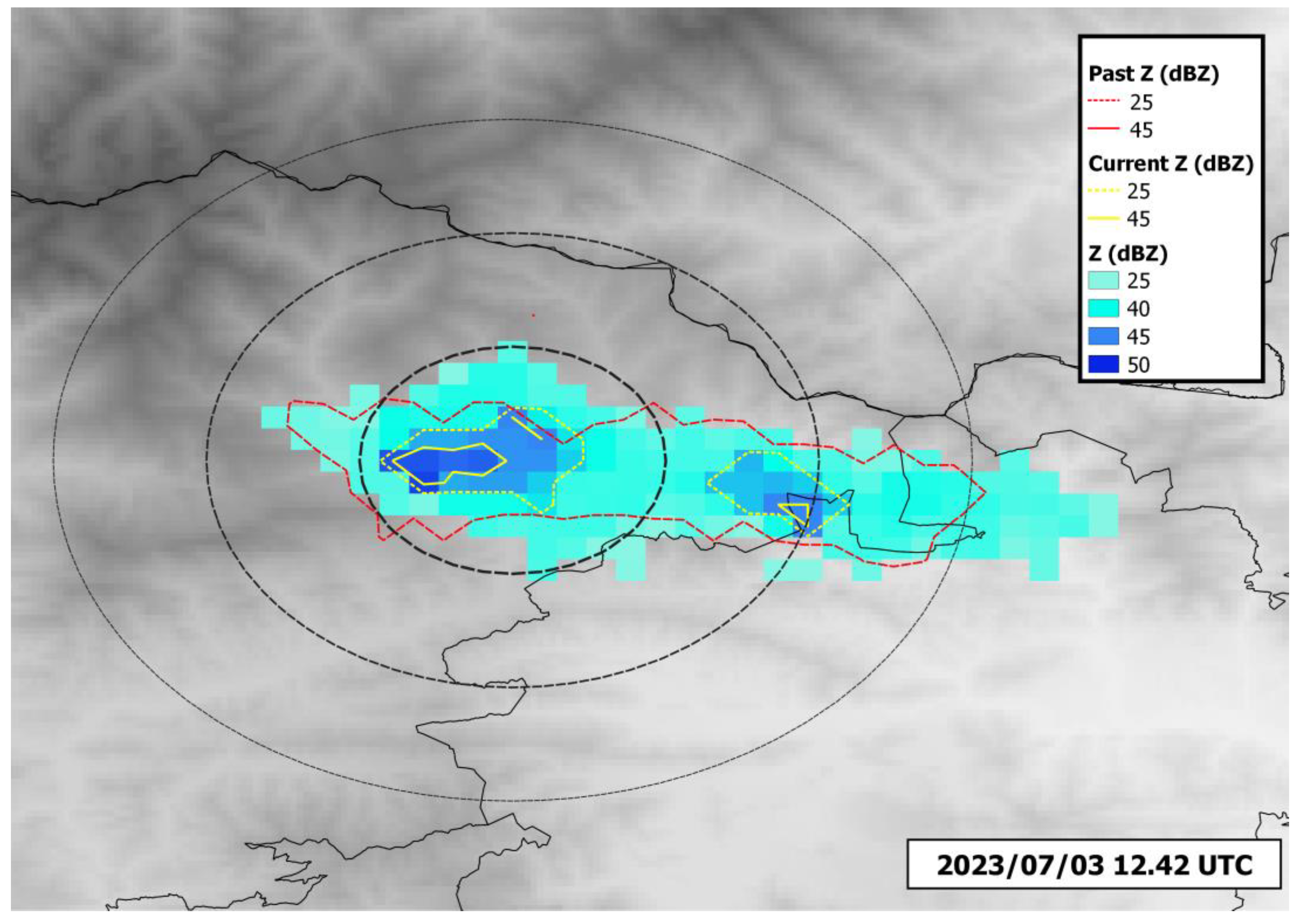

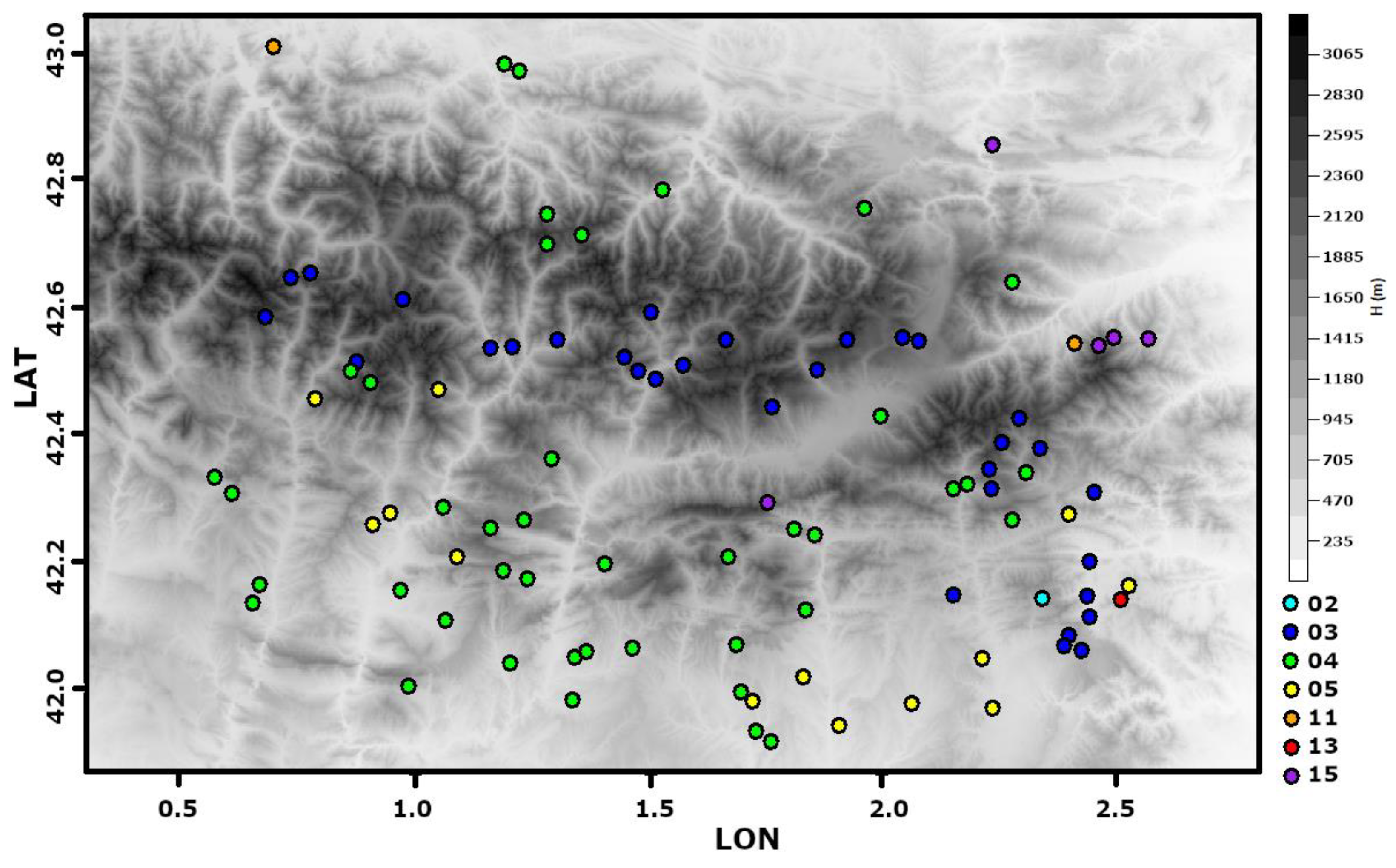

To illustrate the procedure,

Figure 5 shows an example from 3 July 2023 at 12:42 UTC. At that time, there were two candidates for convection initiation (yellow outlines). To determine which of them—if any—are valid candidates, we examined the maximum values of the cumulative reflectivity fields (red outlines) over the previous hour (in this case, this corresponds to the previous 18 minutes, as convection had initiated at 12:30 UTC). The first step the algorithm checks is whether the area is large enough. The left cell had a size of 5 pixels, whereas the right one had only 2 pixels and thus did not meet this criterion. In summary, the right cell does not meet the criteria for being considered a convection initiation, whereas the left one is a good candidate when applying the criteria of (i) a minimum distance of 5 km from previous cells, (ii) any time between 18 minutes and 1 hour, and (iii) an area exceeding 3 or 5 pixels. To validate these thresholds, we compared the results with the previous visual analysis, which confirmed that the left candidate was indeed a convection initiation point (

Figure 6).

It is important to keep in mind that, in the present study, we used the following definitions:

Convective cell: an area exceeding the 45 dBZ threshold.

Convection initiation: the first time a convective cell is identified; this is determined according to criteria such as size, the occurrence of previous convection, and the distance to prior occurrences. It should be noted that this time refers to when the radar data reaches 45 dBZ, not to the actual onset of convection.

Valid event: any day with reflectivity cores exceeding 45 dBZ that originate exclusively within the study area, i.e., not moving into the region from any neighboring area.

The primary goal of this research was to identify the optimal thresholds for the different variables: minimum area of 45 dBZ (between 3 and 9 pixels, in steps of 2), number of previous images (between 3 and 10, in steps of 1 image), minimum distance between current and previous 45 dBZ cores (between 5 and 50 km, in steps of 5 km), and minimum reflectivity between the two cores (between 25 and 35 dBZ, in steps of 5 dBZ). Using this approach, we manually identified convection initiation points (from planar images and 3D data in complex cases) for seven events in July 2023 (see

Figure 6). These points were considered the ground truth, and this period served as the test dataset.

Once the validation determined the optimal thresholds, they were applied to the remaining data (June to August 2022–2024) to identify all convection initiation points and generate a map of hotspots in the study area, which represents the final objective of this work.

3. Results

The verification metrics between observed and predicted convection initiation events, derived from contingency tables for different thresholds of distance, time, area, and reflectivity (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4), enable the assessment and establishment of the most suitable values for each variable in defining the application criteria across all episodes in the series.

In the present case, regarding the first variable — distance — the optimal threshold has been determined to be 30 km. Although the overall level of agreement (VMAX) is already very high from 15 km onward (with the strong penalty from false positives largely disappearing), the 30 km threshold provides a better event prevalence (Base Rate or BASE). For the second variable, time, referring to the number of preceding radar images considered, all thresholds yielded high VMAX values, and several candidates could have been selected. Ultimately, the 30-minute window (up to five preceding radar images) was chosen as the most appropriate combination of VMAX and BASE.

Regarding the third variable, the area of pixels exceeding 45 dBZ, the threshold of 3 pixels was found to be among the most suitable options. Although 9 pixels yielded a slightly higher VMAX, the 3-pixel criterion was preferred as it matches the manual analysis approach. Finally, for the reflectivity between two convective cores, a threshold of 25 dBZ was adopted, as the verification metrics returned best results than for the rest of tested values, which supports the individualization of the convective cores.

Although the objective of this study — which covers only three years — is not to analyze the overall geographical distribution of 45 dBZ hotspots, but rather to establish a consistent and robust methodology suitable for long and representative time series that enables the detection of areas with the highest density of convection initiation, some preliminary remarks can nonetheless be made.

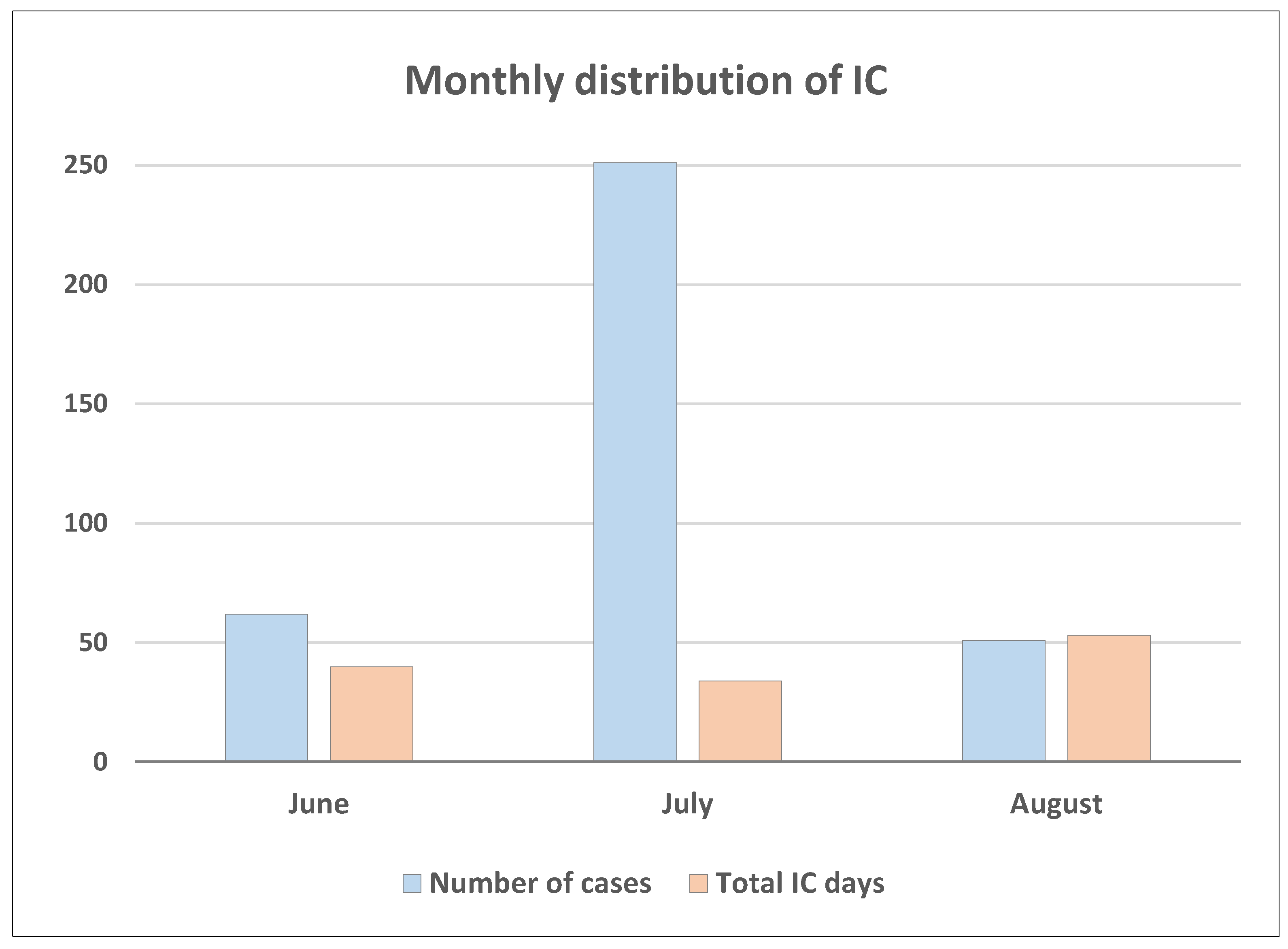

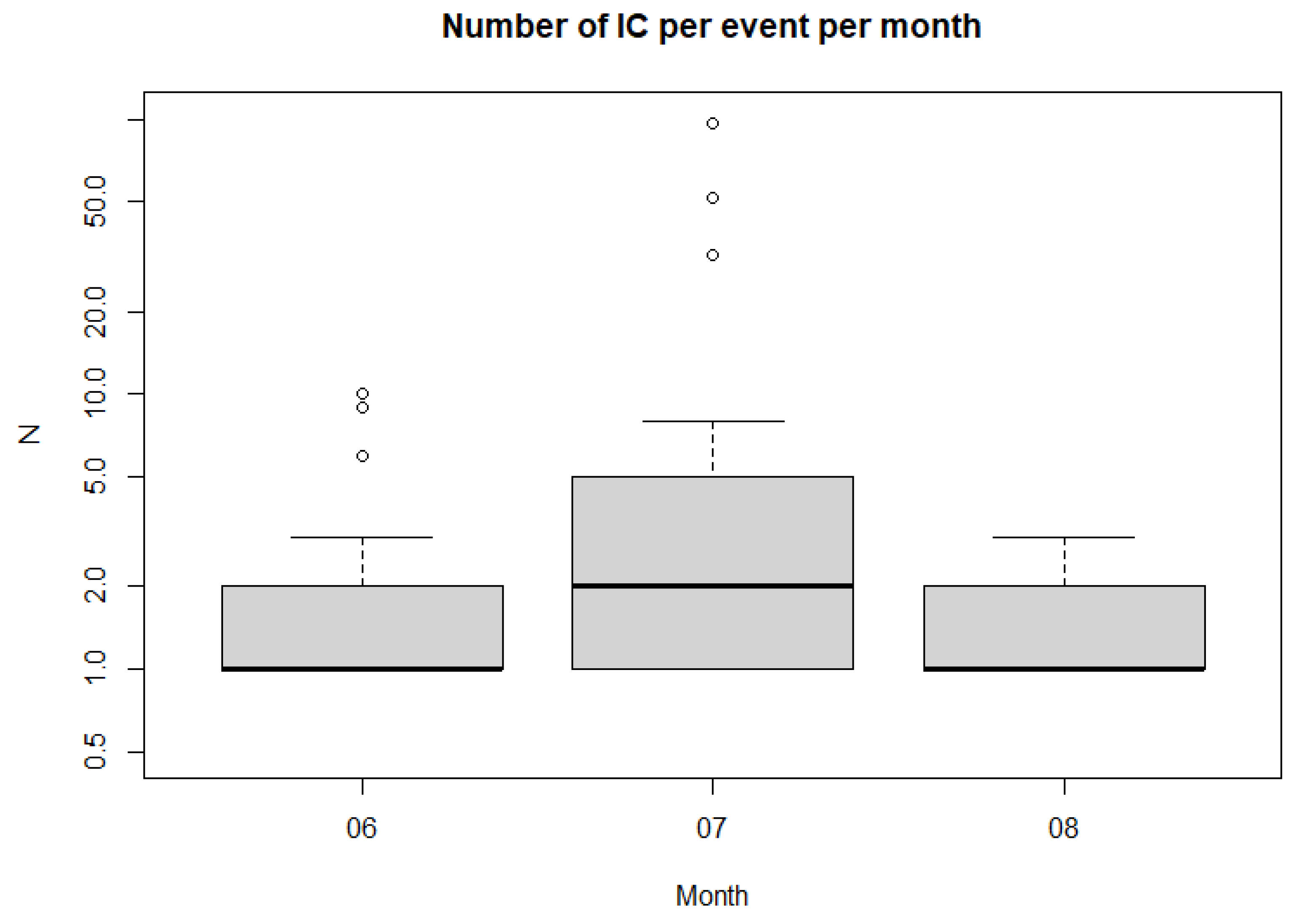

In this sense, in the monthly distribution of convection initiation events during summer (

Figure 7), July clearly stands out, with nearly 250 cases recorded, despite having the smallest number of days (34), compared with June and August, which present around 50–60 cases and 40 and 53 days respectively. Thus, July days with convection presented on average, a higher number of initiation events per day, with some days exceeding 50 cases (

Figure 8). Future studies based on longer datasets will be needed to verify whether this represents a persistent feature or is merely specific to this limited sample.

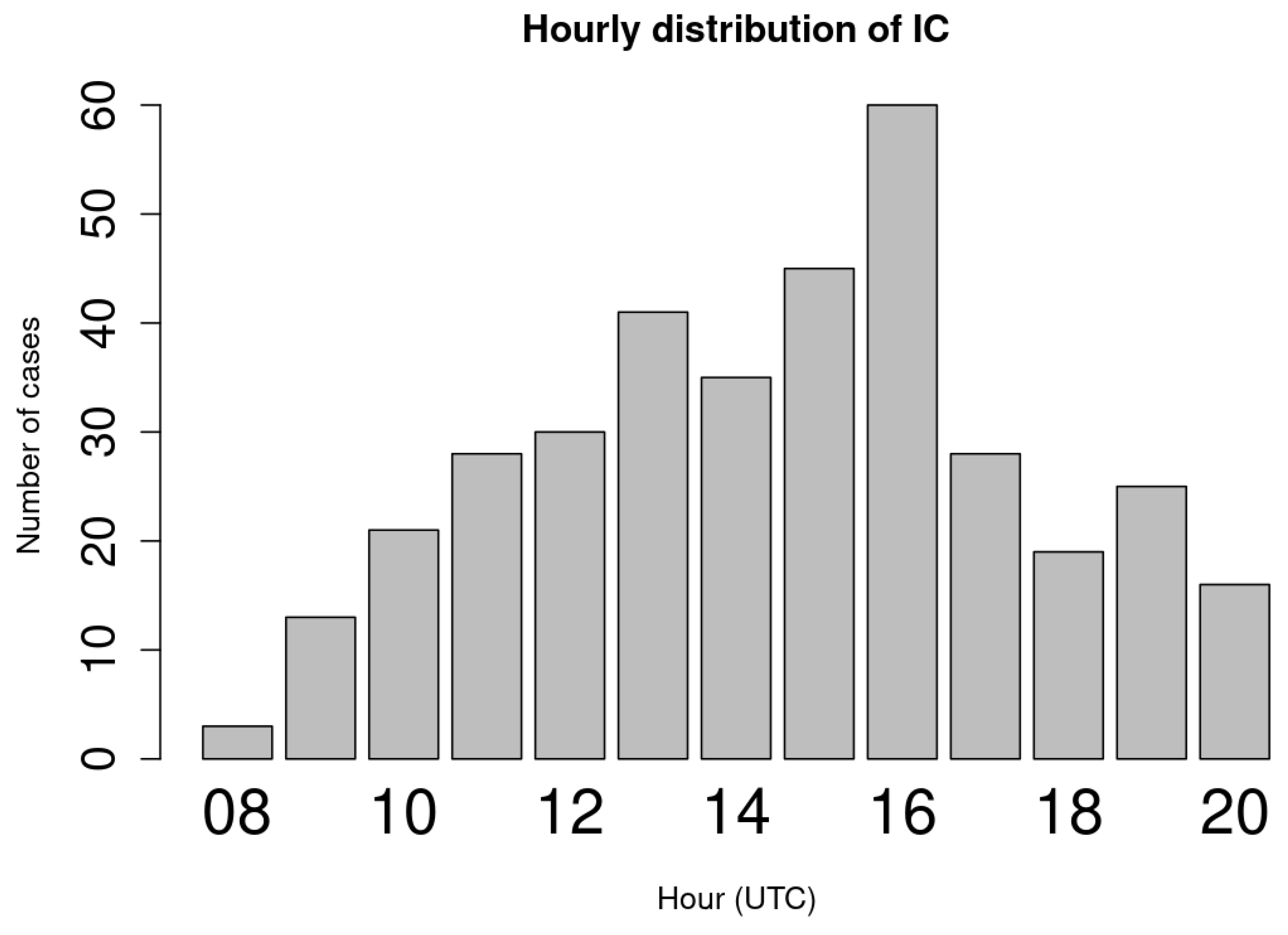

It is also worth highlighting the analysis of the diurnal distribution of convection initiation events between 08:00 and 20:00 UTC (

Figure 9). The hour with the maximum number of cases was 16–17 UTC. The bulk of convection initiation occurred between 13 and 17 UTC, the four-hour intervals with the highest number of cases. This result is fully consistent with the diurnal evolution of convection in this mountain range and with previous studies, in which, for the Catalan Pyrenees, the hourly distribution of only the first 45 dBZ convective initiation of the day was analyzed, showing the bulk of events between 11 and 16 UTC VR22 [

21].

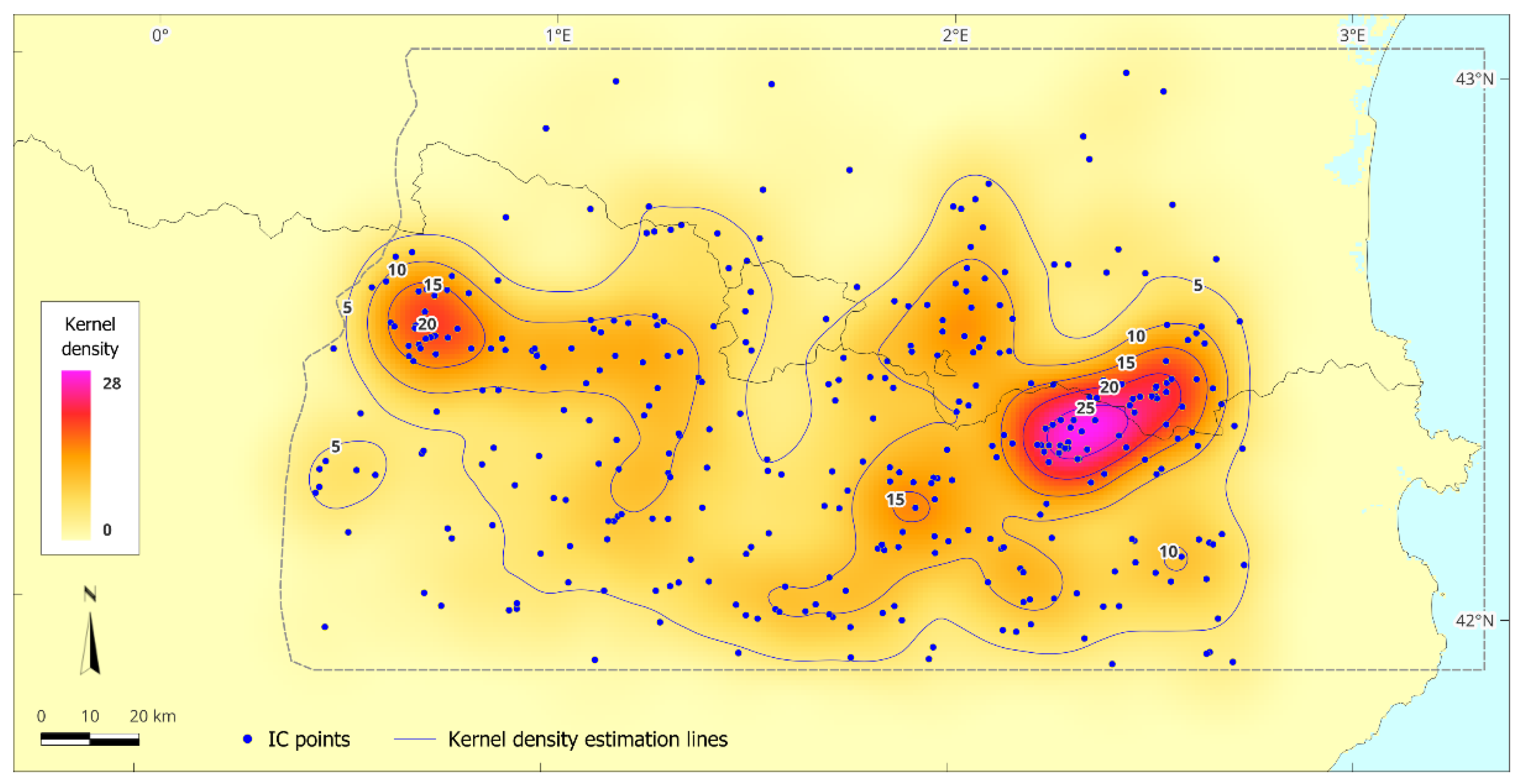

Finally, the production of a heatmap or kernel density map based on the three-year sample (

Figure 10), aimed at preliminarily identifying the sectors with the highest density of convection initiation across the study area, made it possible to locate two important regions of initial convection: a main one, in the eastern part of the study area, straddling the Catalan and French Pyrenees; and a secondary one, in the westernmost part of the area, straddling the Catalan and Aragonese Pyrenees. In the previous study mentioned above, which focused on the first 45 dBZ daily initiation in the Catalan Pyrenees, the sector of maximum activity coincided with the main core identified in this sector. This indicates that, even with a short series, maximum activity remains concentrated in the same sector, which may explain the regularity of this phenomenon in the area and supports the validity of the methodology developed here. By contrast, the secondary core was not apparent in that study, a finding that should be confirmed by future work, as it will apply the detection of all possible convection initiation clusters across the entire eastern Pyrenees using longer datasets.

4. Discussion

There are no publications regarding climatology of convection initiation around the world, at least, as we have had notice. However, analysis of events [

3,

6] or field campaigns summaries [

4,

5] demonstrated the complexity of forecasting this type of event. Furthermore, [

12,

13,

14] presented the high occurrence of heavy rainfall in the Pyrenees, with high impact over the infrastructures and the population caused by floods, debris flows, among other phenomena. Then, it is necessary to have a precise map of the hotspots of thunderstorms initiation to help in the water cycle management of the region.

[

19] did an analysis of thunderstorms cases in the Eastern Pyrenees occurring under anticyclonic conditions and low instability thorough numerical model and radar of thunderstorms cases. Although the area and the meteorological conditions were not the same as the present study, the hotspots are quite like those obtained here. They also search for the meteorological causes, mainly explained by the interaction between the topography and the breeze. These meteorological conditions were also referred to in the analysis of lighting activity [

20], who found the monthly activity peak in June. In our case, we have analyzed few years to compare with, but the goal of the current research was developing the methodology. Therefore, we have planned to apply this methodology in the future to a larger database, to get more robust results that can be compared with those previous studies.

The preliminary analysis of VR22 showed the same hotspots. However, the new results indicated that other areas are also prone to convection development, probably in secondary or tertiary growths (thunderstorms that birth because the interaction between orography and older cells flow). As [

6] indicated, the newborn cells are usually more intense and produce larger precipitations amounts.

Moving to the purpose of the current research, it has been impossible to find any comparable study in the sense of the development of a methodology. However, the patterns shown in [

14,

15] are clearly coincidental with the obtained in our study. Besides, the results fitted also with the ocular analysis made previously to identify the convective initiations manually. In any case, we think that more data, this is, more cases of study will help to adjust the threshold obtained for the different parameters. Furthermore, it seems that the distance between reflectivity peaks is the less restrictive magnitude, while, on the contrary, the size of the area and the time between peaks play a major role.

Finally, our future work will include, among a more robust map of initiation hotspots, the relationship between this map and the different factors observed on the previous analysis, a part of the topography: wind, thermal, and dynamic conditions [

1,

3,

4].

There are no publications on the climatology of convection initiation worldwide, at least to our knowledge. However, analyses of events [

3,

6] and summaries of field campaigns [

4,

5] have demonstrated the complexity of forecasting these types of events. Furthermore, [

12,

13,

14] reported a high occurrence of heavy rainfall in the Pyrenees, causing significant impacts on infrastructure and the population through floods, debris flows, and other related phenomena. Therefore, it is necessary to have a precise map of thunderstorm initiation hotspots to support water cycle management in the region.

[

19] analyzed thunderstorm cases in the eastern Pyrenees occurring under anticyclonic conditions and relative stability using numerical models and radar data. Although the area and meteorological conditions differed from the present study, the hotspots are largely consistent with those obtained here. They also investigated the meteorological causes, primarily explained by the interaction between topography and local breezes. These conditions were also highlighted in the analysis of lightning activity [

20], which found a monthly peak in June. In our case, we analyzed only a few years for comparison, as the primary goal of the current research was the development of the methodology. We plan to apply this methodology to a larger database in the future to obtain more robust results that can be compared with previous studies.

The preliminary analysis of VR22 showed similar hotspots. However, the new results indicate that other areas are also prone to convection development, likely corresponding to secondary or tertiary growths (thunderstorms triggered by the interaction between orography and older cell flows). As [

6] noted, newly formed cells are usually more intense and produce larger amounts of precipitation.

Regarding the aim of the current research, no comparable study exists in terms of developing a methodology. However, the patterns reported in [

14,

15] are clearly consistent with those obtained in our study. Moreover, the results align with previous visual analyses conducted to manually identify convective initiations. In any case, more data—i.e., additional case studies—will help refine the thresholds obtained for the different parameters. It also appears that the distance between reflectivity peaks is the least restrictive parameter, whereas the area size and the time interval between peaks play a more significant role.

Finally, our future work will include, in addition to producing a more robust map of initiation hotspots, the analysis of the relationships between this map and various influencing factors beyond topography, including wind, thermal, and dynamic conditions [

1,

3,

4].

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop an automatic methodology for identifying convection initiation in mountainous areas using weather radar. The technique employs CAPPI reflectivity products and various parameters (reflectivity, area, size, and time) to detect points associated with new convection, even in regions where thunderstorms have previously occurred.

Due to data limitations, mainly radar coverage and beam blockage, we detected the time when thunderstorms reach 45 dBZ at low levels, rather than the exact time when convection begins. However, the temporal and spatial separation between these two events is generally small, according to the typical convection life cycle. We focus on the 45 dBZ threshold because it corresponds to intense precipitation and, in some cases, severe weather.

The methodology was initially applied to a small sample, as the main focus was on the technique rather than the results. Nevertheless, the preliminary results show a high level of agreement with previous analyses, despite some differences between our study and others.

Identifying hotspots of convection initiation in complex topographic regions enables the detection of areas that water resource managers should consider when planning future infrastructure development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R. and F.V.; methodology, T.R. and F.V.; software, T.R.; validation, T.R. and F.V.; formal analysis, F.V.; investigation, T.R. and F.V.; data curation, T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R. and F.V.; writing—review and editing, T.R. and F.V.; visualization, T.R. and F.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available under requirement via e-mail to the Authors.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the Meteorological Service of Catalonia for the data provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LFC |

Free Convection Level |

| MCS |

Mesoscale Convective Systems |

| XRAD |

Radar network of the Meteorological Service of Catalonia |

| PPI |

Plan Position Indicator |

| CAPPI |

Constant Altitude Plan Position Indicator |

| UTC |

Universal Time Coordinated |

References

- Doswell III, C. A., Brooks, H. E., & Maddox, R. A. (1996). Flash flood forecasting: An ingredients-based methodology. Weather and forecasting, 11(4), 560-581.

- Johns, R. H., & Doswell III, C. A. (1992). Severe local storms forecasting. Weather and Forecasting, 7(4), 588-612.

- Abulikemu, Abuduwaili, Jie Ming, Xin Xu, Xiaoyong Zhuge, Yuan Wang, Yunhui Zhang, Shushi Zhang, Bixin Yu, and Mangsuer Aireti (2020): Mechanisms of Convection Initiation in the Southwestern Xinjiang, Northwest China: A Case Study. Atmosphere, 11(12), 1335. [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, T. M., & Parsons, D. B. (2006). A review of convection initiation and motivation for IHOP_2002. Monthly weather review, 134(1), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C. L., & Rasmussen, E. N. (1998). The initiation of moist convection at the dryline: forecasting issues from a case study perspective. Weather and forecasting, 13(4), 1106-1131. [CrossRef]

- Abulimiti, A., Q. Sun, L. Yuan, Y. Liu, J. Yao, L. Yang, J. Ming, and A. Abulikemu (2023). A Case Study on the Convection Initiation Mechanisms over the Northern Edge of Tarim Basin, Xinjiang, Northwest China. Remote Sensing, 15(19), 4812. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, L. J., A. M. Blyth, R. R. Burton, A. M. Gadian, T. M. Weckwerth, A. Behrendt, & P. Di Girolamo (2011): Initiation of convection over the Black Forest mountains during COPS IOP15a. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 137(S), 176-189. [CrossRef]

- Göbel, M., Serafin, S., & Rotach, M. W. (2023). Adverse impact of terrain steepness on thermally driven initiation of orographic convection. Weather and Climate Dynamics, 4(3), 725-745. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M., Van Baelen, J., & Richard, E. (2011). Influence of the wind profile on the initiation of convection in mountainous terrain. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 137(S1), 224-235. [CrossRef]

- Kirshbaum, D. J., Adler, B., Kalthoff, N., Barthlott, C., & Serafin, S. (2018). Moist orographic convection: Physical mechanisms and links to surface-exchange processes. Atmosphere, 9(3), 80. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Xue, M., & Tan, Z. (2016). Convective initiation by topographically induced convergence forcing over the Dabie Mountains on 24 June 2010. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 33, 1120-1136. [CrossRef]

- Trapero, L., Bech, J., & Lorente, J. (2013): Numerical modelling of heavy precipitation events over Eastern Pyrenees: Analysis of orographic effects. Atmospheric Research, 123, 368-383. [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M. C., Llasat-Botija, M., Pardo, E., Marcos-Matamoros, R., & Lemus-Canovas, M. (2024). Floods in the Pyrenees: a global view through a regional database. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences Discussions, 2024, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Canovas, M., J.A. Lopez-Bustins, J. Martín-Vide, A. Halifa-Marin, D. Insua-Costa, J. Martinez-Artigas, L. Trapero, R. Serrano-Notivoli, and J.M. Cuadrat (2021): Characterisation of extreme precipitation events in the Pyrenees: From the local to the synoptic scale. Atmosphere, 12(6), 665. [CrossRef]

- Castro, A., Sánchez, J. L., & Fraile, R. (1992): Statistical comparison of the properties of thunderstorms in different areas around the Ebro-Valley (Spain). Atmospheric research, 28(3-4), 237-257. [CrossRef]

- Bresson, E., Ducrocq, V., Nuissier, O., Ricard, D., & de Saint-Aubin, C. (2012): Idealized numerical simulations of quasi-stationary convective systems over the Northwestern Mediterranean complex terrain. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 138(668), 1751-1763. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, V., Bischoff-Gauß, I., Kalthoff, N., Gantner, L., Roca, R., & Panitz, H. J. (2017). Initiation of deep convection in the Sahel in a convection-permitting climate simulation for northern Africa. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 143(703), 806-816. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K. L., & Houze Jr, R. A. (2016). Convective initiation near the Andes in subtropical South America. Monthly Weather Review, 144(6), 2351-2374.

- Callado, A., & Pascual, R. (2005). Diagnosis and modelling of a summer convective storm over Mediterranean Pyrenees. Advances in Geosciences, 2, 273-277. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, N., Rigo, T., Bech, J., & Soler, X. (2007): Lightning and precipitation relationship in summer thunderstorms: Case studies in the North Western Mediterranean region. Atmospheric research, 85(2), 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Bonet, F., & Rigo, T. (2022). A Characterization of the Initiation of the Summer Diurnal Evolution Convection in the Catalan Pyrenees: an 11-year (2010-2020) Radar-Data Based Analysis. Tethys, 19, 1-13.

- Bech, J., Gjertsen, U., & Haase, G. (2007). Modelling weather radar beam propagation and topographical blockage at northern high latitudes. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society: A journal of the atmospheric sciences, applied meteorology and physical oceanography, 133(626), 1191-1204. [CrossRef]

- Germann, U.; Boscacci, M.; Clementi, L.; Gabella, M.; Hering, A.; Sartori, M.; Sideris, I.V.; & Calpini, B. (2022): Weather Radar in Complex Orography. Remote Sens., 14, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14030503. [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T., & Llasat, M. C. (2007). Analysis of mesoscale convective systems in Catalonia using meteorological radar for the period 1996–2000. Atmospheric Research, 83(2-4), 458-472. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).