1. Introduction and Summary

Suppose that

is

a standard estimate of an unknown parameter

of a statistical model, based on a sample of size

n. That is,

is a consistent estimate, and for

, its

rth order cumulants have magnitude

and can be expanded in powers of

. This is a very large class of estimates, with potential application to a range of practical problems. For example,

may be a smooth function of one or more sample means, or a smooth functional of one or more empirical distributions. A smooth function of a standard estimate is also a standard estimate: see [

29]. [

32] gave the multivariate Edgeworth expansions for the distribution and density of

in powers of

about the multivariate normal in terms of the

Edgeworth coefficients of (2.3). (For typos, see p25 of [

29]. Also replace

by

on 4th to last line p1121 and in (23). To line 3 p1138, add

.) [

30] gave the Edgeworth coefficients explicitly for the Edgeworth expansions to

. [

15].

We now turn to conditioning. This is a very useful way of using correlated information to reduce the variability of estimates, and to make inference on unknown parameters more precise. This is the motivation for this paper. In

Section 3 we take

, and write

and

as

,

and

of dimensions

. Just as the distribution of

allows inference on

w, the conditional distribution of

given

, allows inference on

for a given

. The covariance of

can be substantially less than that of

. Only when

and

are uncorrelated, is there no advantage in conditioning.

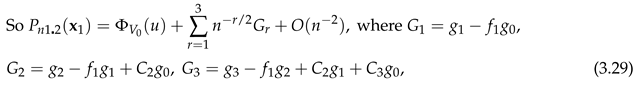

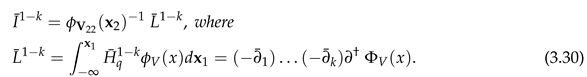

Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 give our main results: explicit expansions to for the conditional density and distribution of given , that is, for the conditional density and distribution of given . In other words it gives the likely position of for any given . The main difficulty is integrating the density. Theorem 3.2 does this in terms of of (3.28), the integral of the multivariate Hermite polynomial, with respect to the conditional normal density. Note 3.1 gives in terms of derivatives of the multivariate normal distribution. Theorem 3.3 gives in terms of the partial moments of the conditional distribution. If , then Theorem 3.4 gives in terms of the unit normal distribution and density.

Section 4 specialises to the case

. Examples are the condtional distribution and density of a bivariate sample mean, of entangled gamma random variables, and of a sample mean given the sample variance.

Section 5 and

Section 6 give conclusions, discussion, and suggestions for future research. Appendix A gives expansions for the conditional moments of

It shows that

given

, is neither a standard estimate, nor a Type B estimate, so that Edgeworth-Cornish-Fisher expansions do not apply to it.

Conditional expansions for the sample mean were given in Chapter 12 of [

4], and used in Section 2.3 and 2.5 of [

13] to show bootstrap consistency.

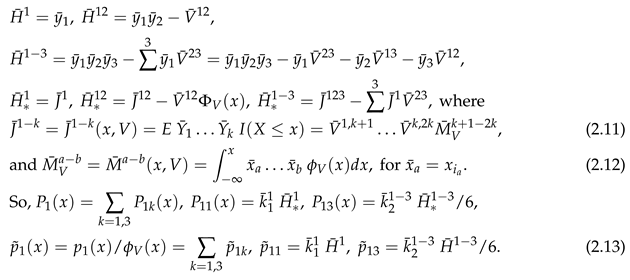

2. Multivariate Edgeworth Expansions

Suppose that

is a

standard estimate of

with respect to

n. (

n is typically the sample size.) That is,

as

, where we use

for expected value, and for

and

the

rth order cumulants of

can be expanded as

where ≈ indicates an asymptotic expansion, and the

cumulant coefficients may depend on

n but are bounded as

. So

the bar replaces each by k. For example

and

We reserve for this bar notation to avoid double subscripts.

the multivariate normal on

, with density and distribution

V may depend on

n, but we assume that

is bounded away from 0.

for

. These are Bell polynomials in the cumulant coefficients of (2.1), as defined and given in [

30]. Their importance lies in their central role in the Edgeworth expansions of

of (

2.2).

(When

and

is a sample mean, the Edgeworth coefficients were given for

all r in [

31]. For typos, see p24–25 of [

29].) Set

Probability

A is true. By [

32], or [

29], for

non-lattice, the distribution and density of

can be expanded as

is

the multivariate Hermite polynomial. We use the tensor summation convention, repetition of

in (2.6) implies their implicit summation over their range,

. [

30] gave

explicitly for

and for

when

.

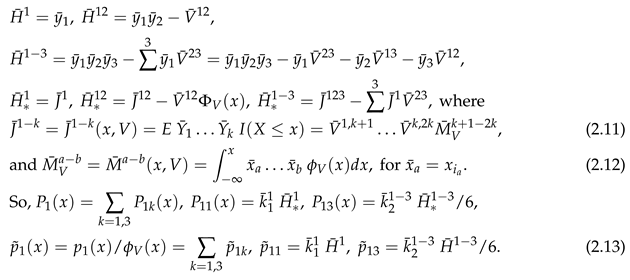

where

sums

over all

N permutations of

giving distinct values. For example,

(So the repeated

in (2.11) implies their repeated summatioin over

.)

are given explicitly in [

30]. So (2.4) with the

in [

30] give the Edgeworth expansions for the distribution and density of

of (

2.2) to

.

and

each have

terms, but many are duplicates as

is symmetric in

. This is exploited by the notation of

Section 4 of [

30] to greatly reduce the number of terms in (2.6).

By (

2.5), the density of

relative to its asymptotic value is

and for measurable

,

If

, then for

r odd,

so that

Examples 3 and 4 of [

30] gave

for

, and .

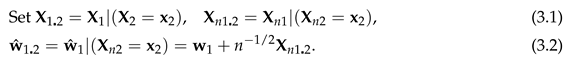

3. The Conditional Density and Distribution

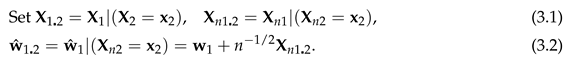

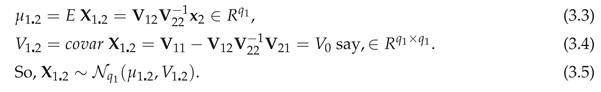

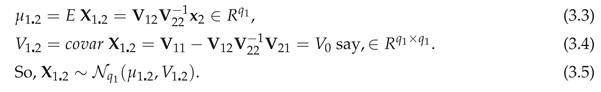

For and partition and as and where are vectors of length . Partition as where are .

Now we come to the main purpose of this paper. Theorem 3.1 expands the conditional density of

about the conditional density of

. Its derivation is straightforward, the only novel feature being the use of Lemma 3.2 to find the reciprocal of a series, using Bell polynomials. Theorem 3.2 integrates the conditional density to obtain the expansion for the conditional distribution of

about the conditional distribution of

in terms of

of (3.28) below, the integral of the Hermite polynomial

of (2.8), with respect to the conditional normal density. Note 3.1 gives

in terms of derivatives of the multivariate normal distribution. Theorem 3.3 gives

in terms of the partial moments of the conditional normal distribution. For

of (3.1), set

Lemma 3.1.

The elements of are

PROOF gives 8 equations relating and . Now solve for .

So for

Since in the sense that for , is less variable than , and is less variable than , unless and are uncorrelated, that is, is a matrix of zeros.

The

conditional density of

is

where

is

of (2.6) for

, and

is the density of

of (3.1). By (4)–(6), Section 2.5 of [

1], for

of (3.4),

So the distribution of

is

For

of (3.3),

of (3.4), and

, set

Corollary 3.1.

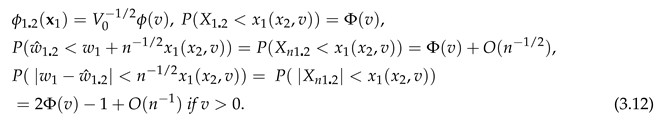

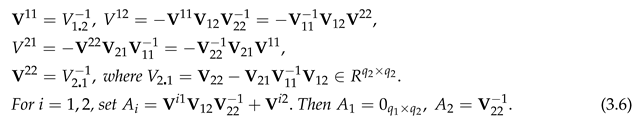

Suppose that . Then for of (3.9),

If

, this gives an asymptotic conditional confidence limit for

given

. So if

, by (2.14), for

of (3.11), 2-sided limits are

So

is given by replacing

and

in

by

By (2.5) and (2.6), for

,

of (3.8) is given by

and

implicit summation in (3.14) for is now over . So,

Ordinary Bell polynomials. For a sequence

from

R, the

partial ordinary Bell polynomial , is defined by the identity

where

for

They are tabled on p309 of [

7]. To obtain (3.7), we use

Lemma 3.2.

Take of (3.15). Set for . Then

PROOF

Now swap summations. □

Theorem 3.1.

Take of (2.6) and of (3.16) with

The conditional density of (3.7), relative to of (3.9), is

and for sequences and So,

PROOF This follows from (3.7) and Lemma 3.2. □

So

of (3.20) and (3.21) give the conditional density to

. We call (3.19)

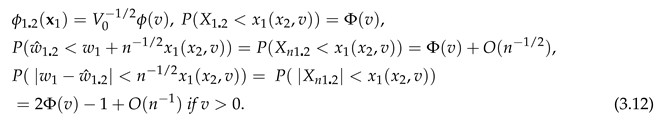

the relative conditional density. We now give our main result, an expansion for the conditional distribution of

. As noted, Theorem 3.2 gives this in terms of

of (3.28) below, an integral of the Hermite polynomial

of (2.8), and Note 3.1 gives

in terms of derivatives of the multivariate normal distribution. Theorem 3.3 gives

in terms of the partial moments of the conditional distribution

of (3.10). When

, Theorem 3.4 gives

in terms of

and

for

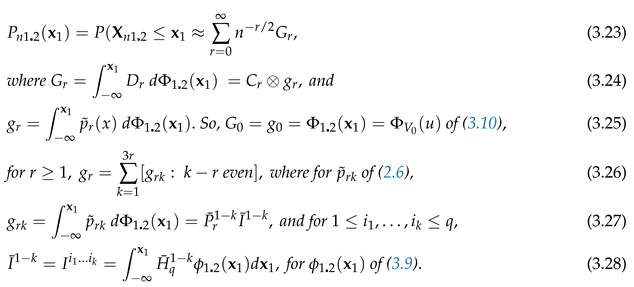

Theorem 3.2.

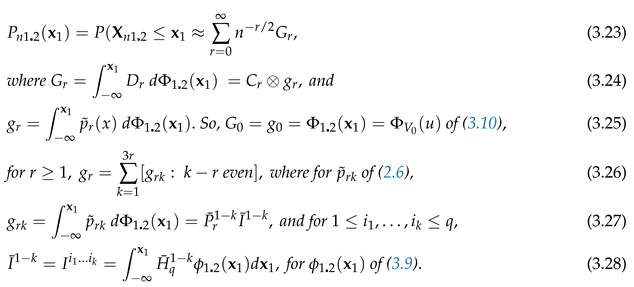

Take of Theorem 3.1. Set The conditional distribution of given , about of (3.10), has the expansion

PROOF (3.26) holds by (2.6). (3.27) holds by (2.6). Now use (3.9). □

for

of (3.17).

is given by

,

is given by

and

is given by

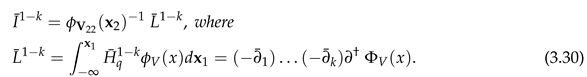

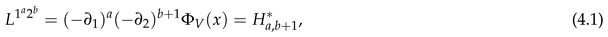

Note 3.1. Set

By (3.9),

Comparing

with the Hermite function

of (2.7), we can call

the partial Hermite function. When

, see (4.1).

By (3.25),

in (3.23) is given by

of (3.18) and

of (3.26). Viewing

as a polynomial in

for

u of (3.9),

is linear in

for

. So

can be expanded in terms of

the partial moments of

This has only

integrals, while (2.12) has

q integrals.

Lemma 3.3.

For , , where

PROOF , where , and for of (3.6). □

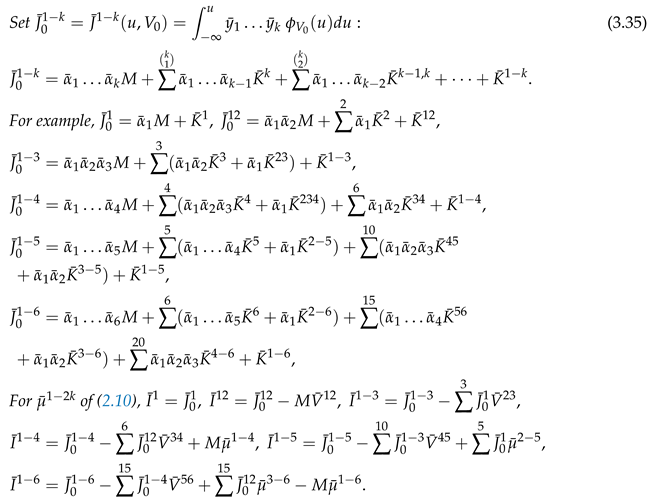

Our main result, Theorem 3.2, gave the conditional distribution expansion in terms of of (3.28). Note 4.1 gave these in terms of the derivatives of . We now give in terms of , the partial moments of the conditional distribution of (3.10). As in (2.10), for any , set summed over all, N say, permutations of giving distinct . For example, .

Theorem 3.3.

Take of (2.11), u of (3.10), M of (3.31), of (3.32), of (3.33), and

. Set

where sum over their range So ,

PROOF Since Substitute into the expressions for Now multiply by and integrate from to

This gives the needed for . The needed for can be written down similarly in terms of the partial moments using for We now show that if , we only need the partial moments of at v of (3.22), and that these are easily written in terms of and a polynomial in v of (3.22).

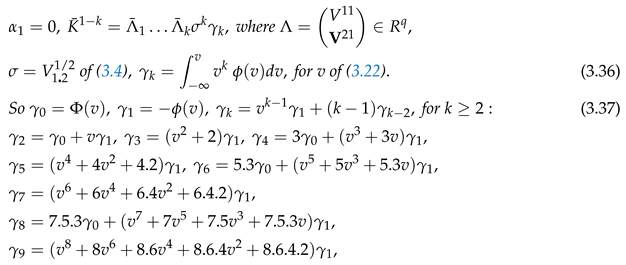

The case So

Theorem 3.4.

For , is given by Theorem 3.3 with where dot denotes multiplication. Also, .

where dot denotes multiplication. Also, .

PROOF For v of (3.22), by (3.9), (3.37) follows from integration by parts. By (3.34), where

That follows from (3.25). □

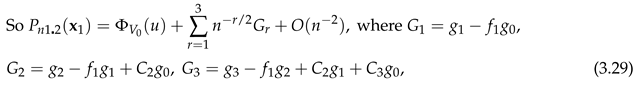

By (3.23), for

of (3.18) and

v of (3.22), the conditional distribution of

is

as in (3.29), and

is given by (3.26) in terms of the integrated Hermite polynomial,

of (3.28) given by Theorems 3.3, 3.4.

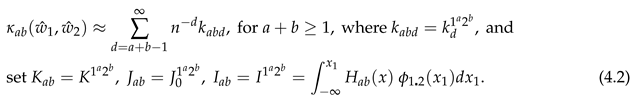

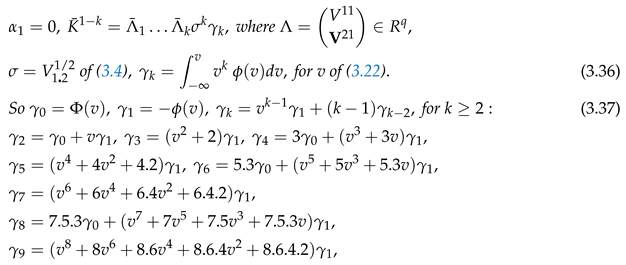

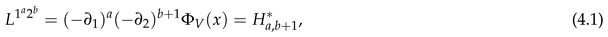

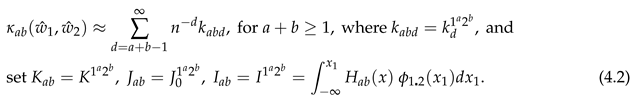

4. The Case

Theorem 3.2 gave the conditional Edgeworth expansion in terms of

of (3.28). Theorem 3.3 gave

needed for

of (3.27) and

of (3.23), in terms of the partial moments

of (3.32). When

, Theorem 3.4 gave

in terms of

and its partial moments for

v of (3.22). But now

so that

or 2. So for

of (2.9), we switch notation to

for

of (3.30). Similarly, write (2.1) as

Also, we switch from

to

given for

in

Section 4 of [

30]. So,

is just

with 1 and 2 reversed. For the other

and

needed for

, see

Section 4 of [

30]. Our main result for this section, Theorem 4.3, gives simple formulas for

and for

of (3.26), the main ingredient needed in Theorem 3.2 for the expansion of the conditional distribution.

Theorem 4.1.

The conditional density of of (3.1), is given by Theorem 3.1 where is given by (3.14) in terms of

PROOF This follows from Theorem 3.1. □

Theorem 4.2 gives a laborious expression for the conditional distribution.

However Theorem 4.3 gives a huge simplification.

Theorem 4.2.

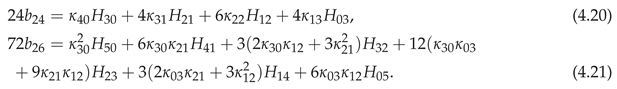

The conditional distribution of of (3.1), is given by Theorem 3.2 with of Theorem 3.4 as follows. For even, of (3.27) is given by

where of (4.2) is given for , as follows in terms of .

Also are with and of (3.33) reversed, before setting and by (3.13). For example, by (4.9), for of Theorem 3.4,

PROOF This follows from Theorems 3.3 and 3.4. □

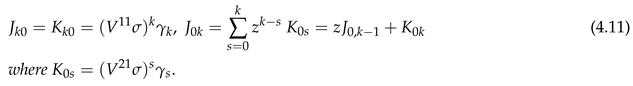

This gives the needed for for the conditional distribution of (3.23)–(3.25) to . The needed for can be written down similarly. We now give a much simpler method for obtaining of (3.27), and so by (3.26), and needed for (3.23) by (3.24). Theorem 4.3 gives and in terms of of (4.2). Theorem 4.4 gives in terms of of (4.11), a function of of Theorem 3.4.

Theorem 4.3.

For v of (3.22), of (4.2) is given by

For and even, of (3.27) is given by

So by (3.26), for of (3.25) is given by

PROOF By (4.8),

By (3.9),

where

and

So,

This proves (4.12). So,

(4.13) follows. (4.14) now follows from (3.14). □

Note 4.1. is just of (4.3) with replaced by for .

So for

is given in terms of

of

Section 3, by

This gives

and

of (3.26) for

, and so the conditional distribution

of (3.23), to

, in terms of

of (4.2) and the coefficients

.

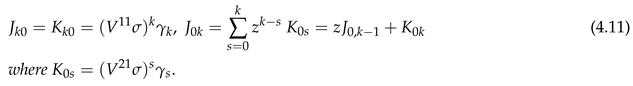

Theorem 4.4.

The needed for of (4.14) and (3.24) are given in terms of of (3.22), and of (4.11), by

PROOF For

follow from Theorem 3.2. By the proof of Theorem 3.3,

can be read off [

30] and the univariate Hermite polynomials

given in terms of

by expanding

To summarise, the conditional density of

of (3.1), is given by Theorem 4.1, and the conditional distribution is given by (3.23), (3.27) in terms of

of (4.14) and

of Theorem 4.4.

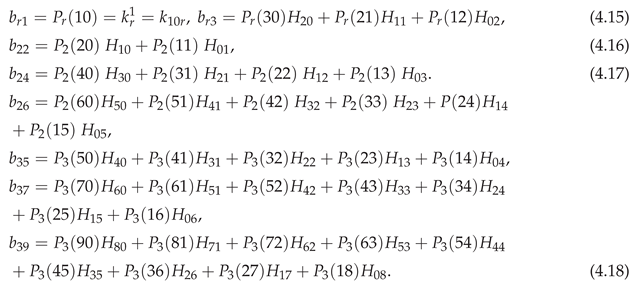

Example 4.1.

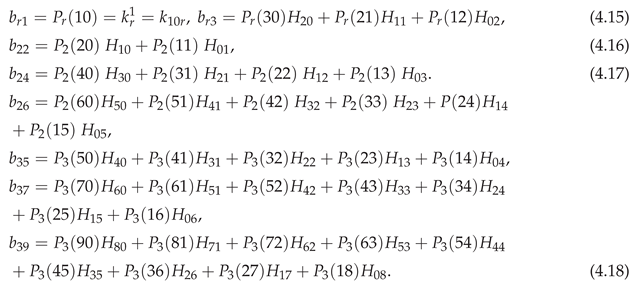

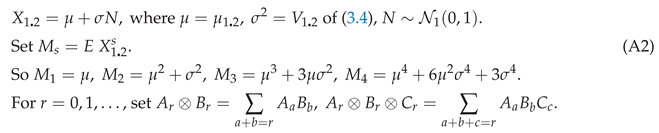

Conditioning when is the mean of a sample with cumulants . The non-zero were given in Example 6 of [30]. So for and for other are given by (4.15)–(4.18) starting

The relative conditional density is given to by (3.19) in terms of of (2.6), of (4.3), of (3.14) for , and of (4.4) for .

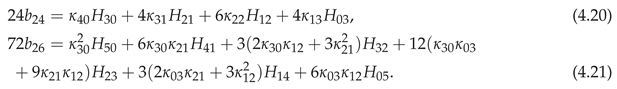

The conditional distribution is given by (3.38) with of (4.14), starting

of Theorem 4.4, and of (4.19). As noted this is a far simpler result than using Theorem 4.2.

for of (4.20), (4.21) and above.

The relative conditional density is given to by (3.19) in terms of of (2.6), of (4.3), of (3.14) for , and of (4.4) for .

The conditional distribution is given by (3.38) with of (4.14), starting

of Theorem 4.4, and of (4.19). As noted this is a far simpler result than using Theorem 4.2.

for of (4.20), (4.21) and above.

Example 4.2.

We now build on

the entangled gamma

model of Example 7 of [30], which gave the needed. Let be independent gamma random variables with means . For , set , and let be the mean of a random sample of size n distributed as . So, and where are independent gamma random variables with means . The rth order cumulants of are and otherwise . Now suppose that ,

the entangled exponential

model. So , and have correlation ,

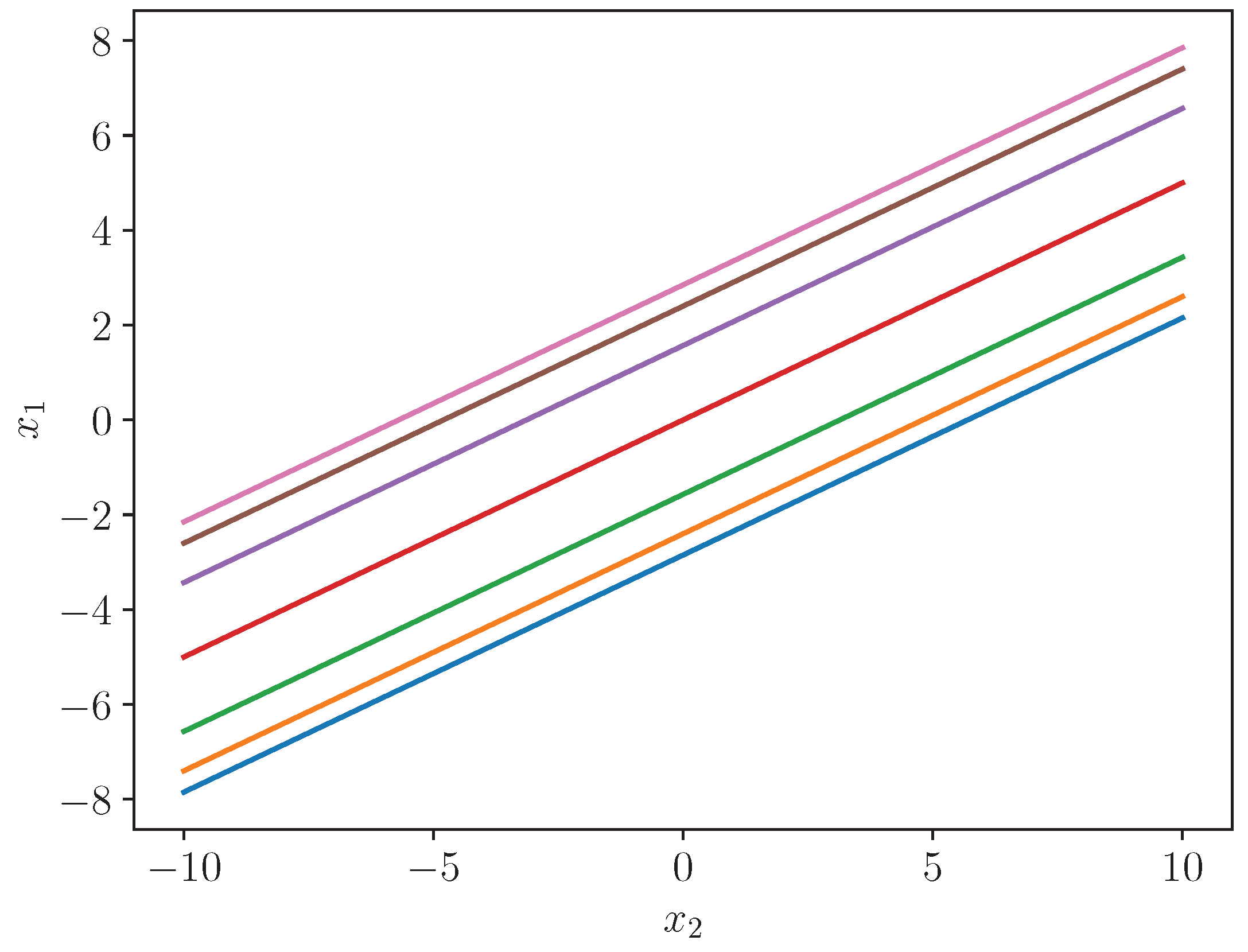

for of (3.11), that is, . Figure 4.1 plots the conditional asymptotic quantiles of , that is, , for . To , given n and , this figure is equivalent to a figure of versus . That is, Figure 4.1 shows to , the likely value of for a given value of In fact by (3.12), lies between the outer limits with probability .98+. So although labelled as versus , the figure can be viewed as showing the likely value of for a given value of

We now give of (3.17), of (3.19), and of (4.4), and for , the coefficients of the expansion for the conditional distribution of (3.23).

By Note 4.1, of Example 7 of [30], symmetry, and (4.14),

Let us work through 2 numerical examples to get the conditional distribution to . We build on Example 7 of [30]. By Theorem 4.1, if then ,

We worked to 8 significant figures, but display less. If , then

So to the relative conditional density of (3.19) for is

so that for and 16 we can only include two terms, and for , only three terms. We now give the 1st 3 , needed by (3.23) for the conditional distribution to . By (3.36),

. By (3.3), .

For example for to

so that divergence begins with the 4th term.

So to the relative conditional density of (3.19) for is

so that we can only include three terms. Finally, we now give the 1st three , needed by (3.23) for the conditional distribution to .

For example for to

so that divergence begins with the 3rd term.

Example 4.3.

Conditioning when the distribution of is symmetric about w. Then for r odd, . By (3.19), the conditional density is

for of Example 1 of [30], of (4.4), and

By (3.38), the conditional distribution of is

for of (4.16) and (4.17).

Example 4.4.

Discussions of pivotal statistics advocate using the distribution of a sample mean, given the sample variance. So Let be the usual unbiased estimates of the mean and variance from a univariate random sample of size n from a distribution with rth cumulant . So By the last 2 equations of Section 12.15 and (12.35)–(12.38) of [26], the cumulant coefficients needed for of (2.3) for , – the coefficients needed for the conditional density to , in terms of , are

(3.19) gives in terms of and , that is, in terms of and of (3.14) in terms of . In this example, many of these are 0. The non-zero are in order needed,

For is now given by (2.13), , and Section 2 of [30]. By (2.4) and (3.19), this gives the conditional density to . And (4.14) gives needed for the conditional distribution to .

5. Conclusions

[

30] gave the density and distribution of

to

, for

any standard estimate, in terms of functions of the cumulant coefficients

of (2.1), called the Edgeworth coefficients,

.

Most estimates of interest are standard estimates, including smooth functions of sample moments, like the sample skewness, kurtosis, correlation, and any multivariate function of

k-statistics. (These are unbiased estimates of cumulants and their products, the most common example being that for a variance.) Unbiased estimates are not needed for Edgeworth expansions, although this does simplify the Edgeworth coefficients, as seen in Examples 4.1, 4.2, 4.4. However unbiased estimates are not available for most parameters or functions of them, such as the ratio of two means or variances, except for special cases of exponential families. [

29] gave the cumulant coefficients for smooth functions of standard estimates.

As noted, conditioning is a very useful and basic way to use correlated information to reduce the variability of an estimate.

Section 3 gave the conditional density and distribution of

given

to

where

is any partition of

. The expansion (3.19) gave the conditional density of any multivariate standard estimate. Our main result, an explicit expansion for the conditional distribution (3.23) to

, is given in terms of the leading

of (3.28). These are given explicitly by Theorems 3.3 and 3.4.

When Theorem 4.1 simplified the conditional density expansion, and Theorem 4.3 gave a huge simplification, and the coefficients of the conditional distribution expansion in terms of of Theorem 4.4.

Cumulant coefficients can also be used to obtain estimates of bias

for

: see [

34,

35,

37].

6. Discussion

A good approximation for the distribution of an estimate, is vital for accurate inference. It enables one to explore the distribution’s dependence on underlying parameters. Our analytic method avoids the need for simulation or jack-knife or bootstrap methods while providing greater accuracy than any of them. [

13] used the Edgeworth expansion to show that the bootstrap gives accuracy to

. [

12] said that “2nd order correctness usually cannot be bettered”. But this is not true using our analytic method. Simulation, while popular, can at best shine a light on behaviour, only when there is a small number of parameters, and only for limited values of their range.

Estimates based on a sample of independent, but not identically distributed random vectors, are also generally standard estimates. For example, for a univariate sample mean

where

has

rth cumulant

, then

where

is the average

rth cumulant. For some examples, see [

22,

23] and [

32] , 2020). The last is for a function of a weighted mean of complex random matrices. For conditions for the validity of multivariate Edgeworth expansions, see [

24] and its references, and Appendix C of [

30].

While the use of Edgeworth-Cornish-Fisher expansions is widespread, few papers address how to deal with their divergence for small sample sizes. [

8] and [

11] avoided this question as it did not arise in their examples. In contrast we confronted this in Example 4.2, the examples of Withers (1984), and in Example 7 of [

30].

We now turn to conditioning. Conditioning on

makes inference on

more precise by reducing the covariance of the estimate. The covariance of

can be substantially less than that of

. [

3] pp34-36 argue that an ideal choice would be when the distribution of

does not depend on

. But this is generally not possible except for some exponential families. An example when it

is true, is when

and

are location and scale parameters: on p54 they essentially suggest choosing

. This is our motivation for Example 4.4. For some examples, see [

2]. Their (7.5) gave a form for the 3rd order expansion for the conditional density of a sample mean to

, but did not attempt to integrate it.

Tilting (also known as small sample asympotics, or saddlepoint expansioins), was first used in statistics by [

9]. He gave an approximation to the density of a sample mean, good for the whole line, not just in the region where the Central Limit Theorem approximation holds. A conditional distribution by tilting, was first given by [

25] up to

, for a bivariate sample mean. Compare [

2]. For some other results on conditional distributions, see [

5,

10,

14,

21], Hansen (1994), [

20], Chapter 4 of [

6], and [

17].

Future directions. The results here give the first step for constructing confidence intervals and confidence regions of higher order accuracy. See [

15] and [

28]. What is needed next, is an application of [

29] to obtain the cumulant coefficients of

or those of

. This should be straightforward.

2. When

, our expansion for the conditional distribution of

of (3.1), can be inverted using the Lagrange Inversion Theorem, to give expansions for its percentiles. This should be straightforward. (The quantile expansions of [

8] and Withers (1984) do not apply as Appendix A shows that conditional estimates of standard estimates are not standard estimates.)

3. Here we have only considered expansions about the normal. However expansions about other distributions can greatly reduce the number of terms by matching the leading bias coefficient. The framework for this is [

32], building on [

15]. For expansions about a matching gamma, see [

33,

36].

4. The results here can be extended to tilted (saddlepoint) expansions by applying the results of [

32]. The tilted version of the multivariate distribution and density of a standard estimate are given by Corollaries 3, 4 there, and that of the conditional distribution and density follow from these. For the entangled gamma of Example 4.2, this requires solving a cubic. See also [

16].

5. A possible alternative approach to finding the conditional distribution, is to use conditional cumulants, when these can be found. Section 6.2 of [

18] uses conditional cumulants to give the conditional density of a sample mean to

. Section 5.6 of [

19] gave formulas for the 1st 4 cumulants conditional on

only when

and

are uncorrelated. He says that this assumption can be removed, but gives no details how. That is unlikely to give an alternative to our approach, for as well as giving expansions for the first 3 conditional cumulants, Appendix A shows that the conditional estimate is not a standard estimate.

6. Lastly we discuss numerical computation. We have used [

27] for our calculations. Its input is

and

, - not

and

. There is a function sub2(sb1,sb2) which takes as argument the two subscripts of mu, and returns the value. If global variables mu20, mu02, mu11 are symbolic variables (defined using sympy) then it returns the answer in terms of those, but if they are numeric then it returns a numeric answer. There is another function called biHermite(n, m, y1, y2) which takes the 2 subscripts of H. If y1 and y2 are symbolic, then it returns a symbolic answer, but if they are numeric it returns a numeric answer. A numerical example is given by Example 4.2, that is, for the case

and

or

.

Similar software for numerical calculations for Theorems 4.1, 4.3 and 4.4 would be invaluable, as would software for applying the Lagrange Inversion Theorem. (We mention R-4.4.1 for Windows: dmvnorm for the density function of the multivariate normal, mvtnorm for the multivariate normal, qmvnorm for quantiles, and rmvnorm to generate multivariate normal variables.) On bivariate Hermite polynomials, see

cran.r-project.org/web/packages/calculus/vignettes/hermite.html

(So the repeated in (2.11) implies their repeated summatioin over .) are given explicitly in [30]. So (2.4) with the in [30] give the Edgeworth expansions for the distribution and density of of (2.2) to . and each have terms, but many are duplicates as is symmetric in . This is exploited by the notation of Section 4 of [30] to greatly reduce the number of terms in (2.6).

(So the repeated in (2.11) implies their repeated summatioin over .) are given explicitly in [30]. So (2.4) with the in [30] give the Edgeworth expansions for the distribution and density of of (2.2) to . and each have terms, but many are duplicates as is symmetric in . This is exploited by the notation of Section 4 of [30] to greatly reduce the number of terms in (2.6). Now we come to the main purpose of this paper. Theorem 3.1 expands the conditional density of about the conditional density of . Its derivation is straightforward, the only novel feature being the use of Lemma 3.2 to find the reciprocal of a series, using Bell polynomials. Theorem 3.2 integrates the conditional density to obtain the expansion for the conditional distribution of about the conditional distribution of in terms of of (3.28) below, the integral of the Hermite polynomial of (2.8), with respect to the conditional normal density. Note 3.1 gives in terms of derivatives of the multivariate normal distribution. Theorem 3.3 gives in terms of the partial moments of the conditional normal distribution. For of (3.1), set

Now we come to the main purpose of this paper. Theorem 3.1 expands the conditional density of about the conditional density of . Its derivation is straightforward, the only novel feature being the use of Lemma 3.2 to find the reciprocal of a series, using Bell polynomials. Theorem 3.2 integrates the conditional density to obtain the expansion for the conditional distribution of about the conditional distribution of in terms of of (3.28) below, the integral of the Hermite polynomial of (2.8), with respect to the conditional normal density. Note 3.1 gives in terms of derivatives of the multivariate normal distribution. Theorem 3.3 gives in terms of the partial moments of the conditional normal distribution. For of (3.1), set

for of (3.17). is given by , is given by and is given by

for of (3.17). is given by , is given by and is given by

Comparing with the Hermite function of (2.7), we can call the partial Hermite function. When , see (4.1).

Comparing with the Hermite function of (2.7), we can call the partial Hermite function. When , see (4.1). This has only integrals, while (2.12) has q integrals.

This has only integrals, while (2.12) has q integrals.

where dot denotes multiplication. Also, .

where dot denotes multiplication. Also, .

for of (3.30). Similarly, write (2.1) as

for of (3.30). Similarly, write (2.1) as Also, we switch from to

Also, we switch from to

This gives and of (3.26) for , and so the conditional distribution of (3.23), to , in terms of of (4.2) and the coefficients .

This gives and of (3.26) for , and so the conditional distribution of (3.23), to , in terms of of (4.2) and the coefficients . The relative conditional density is given to by (3.19) in terms of of (2.6), of (4.3), of (3.14) for , and of (4.4) for .

The relative conditional density is given to by (3.19) in terms of of (2.6), of (4.3), of (3.14) for , and of (4.4) for . Non-central moments.

Non-central moments.