1. Introduction

Thematic mapping derived from remote sensing represents the most rapid and effective approach for quantifying and monitoring both landscape structure [

1] and geomorphological attributes [

2,

3,

4]. Currently, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery has gained particular relevance, as it provides information on the physical and dielectric properties of the terrain under all climatic conditions, both day and night, and even beneath dense vegetation cover [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Recent technological advances in SAR systems include substantially improved spatial resolution and increased revisit frequency, enabling reliable, continuous, and global data acquisition [

10,

11,

12]. Depending on signal frequency, SAR sensors exhibit varying penetration capabilities [

13,

14]. In particular, L-band systems, which operate at the lower end of the frequency spectrum, allow for the extraction of detailed information on soil texture and moisture [

5,

15]. Additionally, Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) derived from SAR interferometry provide robust means of calculating terrain parameters such as slope, aspect, roughness, and convexity [

4,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Collectively, these advances underscore the capacity of SAR-based approaches to enhance geomorphological mapping and landscape analysis by integrating surface and subsurface information with high temporal and spatial fidelity.

Although existing geomorphological mapping has traditionally relied on visual interpretation, a wide range of computational techniques for satellite image classification are now available. Over the past decades, approaches based on Machine Learning (ML) have received particular attention, as they provide highly accurate results, allow for rapid processing, and are inherently non-parametric. This makes them especially suitable for classifying remote sensing data, which often deviate from normal statistical distributions [

21,

22], as well as for handling multidimensional imagery comprising stacked bands from multiple sources [

23]. Among these methods, Random Forest (RF) has emerged as particularly robust. It constructs multiple decision trees defined by the user, using randomly generated subsets with replacement (bagging), whereby samples can be selected more than once or not at all for training. This procedure produces models with high variance but low bias [

24]. The final classification is derived from the average probability across all trees, thereby reducing sensitivity to outliers and mitigating the risk of overfitting [

25].

In Colombia, a methodological framework for the development of analytical geomorphological maps has been proposed [

26]; however, such cartography is not yet available at a regional scale for the study area. Traditionally, these maps have often been produced through analogue approaches, relying on visual interpretation of aerial photographs [

26]. Nevertheless, digital analyses of patterns derived from remote sensing data for landform classification represent a significant and expanding field of research [

7,

18,

27]. These methodological applications are grounded in the spatial localization and distribution of landforms, terrain elevation, surface composition, and subsurface characterization [

19].

An extensive volume of satellite data has been collected over the past decades, posing significant challenges for traditional cartographic techniques applied at regional scales such as Orinoquia. These limitations are largely related to computational capacity and storage requirements for analyzing the available datasets. Google Earth Engine (GEE) is an automated, parallel-computing platform that publicly hosts petabytes of remote sensing information at a planetary scale [

29,

30]. GEE offers substantial advantages over local image processing workflows based on traditional techniques, which typically require downloading datasets from external repositories. Moreover, it integrates a diverse set of analytical functions that can be flexibly applied through programming languages such as Python or JavaScript [

31,

32]. Studies conducted in the Orinoquia have demonstrated that the integrated use of DEM data and SAR imagery outperforms optical images in the identification, discrimination, and delineation of geomorphological features [

33,

34,

35,

36]. These findings underscore the growing relevance of cloud-based geospatial platforms and radar-derived products for advancing geomorphological mapping in complex tropical landscapes.

The objectives of this article are twofold: (i) to characterize and classify, using multidimensional imagery and ML methodologies within the GEE platform, the precise geographical distribution of the geomorphological environments of the Colombian Orinoquia; and (ii) to assess their influence on the region’s physiographic units. This approach enables the development of the first analytical geomorphological map of the region, which, together with other environmental variables, provides essential inputs for regional-scale studies of how biodiversity is structured along environmental gradients.

These digital classification methods constitute consistent and reproducible processes that circumvent the limitations of analogue approaches derived from visual classifications, in which subjective elements and observer assumptions are inherently embedded.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regional Framework

The tectonic conditions that enabled the formation of the Orinoquia are associated with the uplift of the Eastern cordillera during the mid-Tertiary (Oligocene–Miocene), expressed in two principal fronts: a long front in the region between the Duda and Upía rivers, and a shorter yet equally intense front in the El Cocuy region, coupled with continuous sedimentation from river systems descending from the newly formed mountain range [

37,

38]. The region developed over an extensive alluvial sedimentary geosyncline, influenced by tectonic events, Quaternary climatic dynamics, ancient erosional processes in the Guiana Shield massifs, and more recent erosion of the Andes [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Although often described as a territory with relatively homogeneous natural features, gentle slopes, and a landscape largely dominated by grasses [

44], its physiography is closely related to both chronological criteria and its proximity to the Eastern cordillera and the Meta River. The latter constitutes a key hydrological boundary that determines drainage conditions and shapes relief variation: the poorly drained Orinoquia to the north of the river, characterized by alluvial and aeolian fans and plains, and the well-drained Orinoquia to the south, dominated by flat to undulating uplands, hills, and terraces [

45,

46,

47,

48].

The sedimentary deposits, of both Tertiary and Quaternary age, overlie an ancient platform belonging to the Guiana Shield, composed of Precambrian rocks with ages ranging from one to 1.8 billion years. Outcrops of these formations are particularly prominent in

Serranía de La Macarena (La Macarena Mountain Range, hereafter La Macarena) and the High plains, where they appear as hill ranges and inselbergs near the Guaviare and Orinoco rivers, locally referred to as the residual High plains [

38,

44,

49].

2.2. Study Area

The Colombian Orinoquia is bounded to the north by the Arauca River, the international border with Venezuela, and the Meta River; to the east by the Orinoco River; and to the south by the Guaviare and Guayabero rivers. To the west, its boundary is defined by the Guayabero River basin and the upper limit of the Foothills, according to Jaramillo & Rangel-Ch. [

40,

41]. These authors noted that braided and anastomosing fluvial systems originate in rupture zones located between the steep slopes of the cordillera and the Foothills, which tend to occur at higher elevations toward the south, as a consequence of crustal flexure in the High plains. To delineate the physiographic units of the Colombian Orinoquia (

Figure 1), the vector cartographic layer of Colombia’s hydrographic zonation [

50] was employed. In addition, the NASA SRTM v.3 DEM at 30 m resolution, available in GEE, was used to establish altitudinal ranges [

51].

The Foothills (

Piedemonte) was defined eastward and westward based on altitudinal thresholds determined by the river basins present in the region [

33]. South of the Meta River, within the Guamal River basin, the upper limit was set at 575 m and the lower at 350 m. North of the Meta River, the elevation thresholds were defined as follows: 675 m (upper) and 200 m (lower) for the Meta and Pauto river basins; 600 m and 200 m for the Casanare River basin; 425 m and 200 m for the Cravo Sur River; and 375 m and 175 m for the Arauca River. The northern boundary was delimited by the Arauca River, while the southern boundary was set by the Ariari River basin.

La Macarena was delimited to the west by the altitudinal thresholds of 575 m in the Guayabero River basin and 775 m in the Guaviare River basin; to the north and east by the boundaries of the Ariari River basin; and to the south by the Guayabero River and the limits of its respective basin. The Floodplain (Llanura alluvial) was defined to the west by the Foothills, to the north by the Arauca River, to the east by the international border with Venezuela, and to the south by the Meta River. The High Plains (Altillanura) were delimited to the west by the Foothills and La Macarena, to the north by the Meta River, to the east by the Orinoco River, and to the south by the Guaviare River.

2.3. Metodological Framewook

Integrated systems were employed, wherein the outputs or results of one procedure served as the inputs or parameters of the subsequent process (

Figure 2). The geomorphological model incorporated two L-band SAR polarizations and five parameters considered fundamental terrain descriptors, as proposed by Franklin [

27] and Franklin & Peddle [

28]: i) HH/HV polarizations from an annual Alos-PalSAR mosaic for 2021 (Global PALSAR-2/PALSAR collection, available in GEE), which underwent Speckle correction [

52] using a focal mean filter with a 50 m window to improve image classification accuracy [

23,

53]; ii) the NASA SRTM v.3 DEM, from which slope, aspect, and convexity cartographic layers were derived; iii) terrain slope expressed as a percentage, iv) aspect, or slope orientation, expressed in degrees relative to North; v) convexity, calculated from the relative elevation of a seven-pixel moving window compared to its surroundings, categorized as concave (window elevation lower than its surroundings), convex (window elevation higher), or planar (window elevation similar); and vi) terrain roughness, or surface irregularity, quantified through a local variance analysis of slope using seven-pixel moving windows.

The performance of RF classification depends on the quality of the training samples, which must unequivocally represent the thematic categories within the multidimensional image [

54]. The training areas for the geomorphological model were defined using digital elevation profiles derived from the DEM, combined with the visual interpretation of L-band SAR imagery. Polygonal entities of the identified landforms were delineated according to the geomorphological units described by the Colombian Geological Survey [

26]. The training areas covered more than 0.25% of the study area, ensuring both representativeness and validity of the sample [

55]. This allocation considered the spectral breadth of the multidimensional images as well as the landscape representativeness of the classes, since balanced samples across thematic categories yield higher accuracy by reducing both commission and omission errors in underrepresented classes [

56,

57].

Although it is generally assumed that a higher number of decision trees improves the performance of the RF model, processing time increases linearly with this parameter, thereby justifying its calibration to an optimal number of trees [

53]. Accordingly, the classifiers were configured using sampling variables derived from multidimensional images and vector layers of the training areas. The dataset was subsequently partitioned into 70% for training and 30% for accuracy assessment, applying an iterative function in increments of 10 trees until reaching a total of 150. Finally, predictions were generated based on the sampling variable and the sequential tree parameters, and classification accuracy was plotted against the number of trees [

33].

Subsequently, a RF classification was performed, in which training variables for the classifiers were defined using the input layers and training areas, following an approach analogous to the sampling variables employed during the parameterization procedures. The classifiers were then configured with the training variables and the number of trees that yielded the highest accuracy during parameter tuning. The classification outputs were exported in raster format, at a spatial resolution consistent with the input layers (30 m), subsequently generalized to a spatial scale of 5 ha, and converted to vector format. Model accuracy was assessed using the same training variables employed in the Random Forest modeling, along with the number of classification trees previously defined [

58]. Training areas were partitioned following the same parameterization procedures (70% – 30%). Accuracy assessments included confusion matrices, overall model accuracy, producer’s and user’s accuracies, and Kappa coefficients [

33].

3. Results

As a result of the physiographic delimitation, the calculated area of the Orinoquia region is 233,546.19 km², which is smaller than the 260,000 km² previously reported by FAO [

45] and Riveros [

59]. Four geomorphological environments were identified: (i) the denudational, defined by the combined action of moderate to intense processes of weathering, erosion, and gravity- and rainfall-driven transport; (ii) the fluvial, encompassing erosional processes generated by river currents as well as the deposition of sediments in adjacent areas; (iii) the aeolian, determined by wind activity and the consequent transport, fragmentation, and deposition of particles of varying sizes; and (iv) the structural, resulting from processes related to the Earth’s internal dynamics, mainly associated with rock folding and faulting [

26].

3.1. Foothills Geomorphology

The extent of the Foothills was estimated at 19,123.71 km², representing 8.19% of the Orinoquia. This figure exceeds by 6,537.75 km² the previously reported area for this physiographic unit, which accounted for 72.40% of the region [

45,

59]. The geomorphology of the Foothills is defined by thrust faults along the tectonic boundary separating the cordillera from the alluvial plains, resulting in an abrupt change in slope that sustains the dissection, transport, and deposition of detrital material in a torrential manner [

38,

60].

Figure 3 presents the geomorphological map of the Foothills, where the legend indicates that fluvial landforms predominate, occupying 80.83% of the area. Within this environment, sub-recent accumulation terraces are particularly notable; these are associated with the widening of valleys formed by rivers descending from the Eastern cordillera and are located along the eastern margin of the Foothills, where the lowest altitudes and slopes of this physiographic unit are found. The sub-recent accumulation terraces largely constitute progressive transitional units toward the Floodplain, showing no apparent degradation [

40,

41,

61]. Ancient accumulation terraces, formed during the Pleistocene, are exposed in areas of greater elevation and slope, influenced by neotectonic activity and surface runoff. These are overlain by sediments deposited after subsidence events toward the east, which subsequently gave rise to more recent, lower-gradient terraces dating to the Holocene. In these deposits, anastomosing channels with intense fluvial dynamics are clearly identifiable [

38,

62].

Subsequent in representativeness are the actual alluvial fans, formed by torrential and fluvial accumulation in a radial pattern that debouches into flat areas. These originate from the higher elevations of the cordillera and are frequently situated either between structural-environment units or along the higher western margins of the Foothills, in juxtaposition with accumulation terraces located at lower altitudes. The torrential sediment load derived from the cordillera is deposited discontinuously across the Foothills fans, generating conditions of both actual and potential instability. Consequently, river channels often experience bed aggradation, leading to the development of anastomosing morphologies [

38,

60]. Active alluvial fans display intense erosive processes, particularly toward the northern Foothills [

40,

41], where they define the western boundary of this physiographic unit. Ancient alluvial fans, discontinuously distributed along the margin adjacent to the cordillera, were deposited during the Pleistocene. These have since been deformed and delineated by recent tectonic activity, including folding and faults parallel to the mountain range, as well as episodes of subsidence and uplift. Such processes have produced multiple terrace levels, often difficult to differentiate, traversed by braided channels [

38,

62,

63]. Floodplains are also prominent features, associated with the main fluvial channels descending from the cordillera, which frequently exhibit braided patterns. In these wide, shifting channels, gravel is deposited, with clast size progressively decreasing eastward in response to slope reduction and the consequent decline in transport capacity, while finer sediments accumulate along the banks [

62].

Accumulation terraces are commonly located between su-recent alluvial fans and sub-recent terraces. They were formed by erosional and alluvial sedimentation processes within ancient floodplains, during periods in which depositional dynamics prevailed over dissection 38]. The denudational environment encompasses 11.70% of the Foothills, characterized by erosive and erosional hillsides along the margin adjacent to the cordillera, in areas of pronounced gradients and frequently associated with structural-environment units. Representing the smallest extent, the structural environment accounts for 7.47% of the Foothills. It is located along the margin adjoining the cordillera, where structural hills and loins dominate. These were shaped by tectonic processes, combined with rock weathering and denudation, and were further influenced by basement formation and intense regional shear deformation [

40,

41].

3.2. Geomorphology of La Macarena

La Macarena region was estimated to cover 20,747.63 km², representing 8.88% of the Orinoquia. This mountain range, reaching an elevation of 1,598 m and extending over 130 km, constitutes a rocky massif associated with the Guiana Shield, with a maximum estimated age dating back to the Precambrian, whose structure was subsequently overlain by Andean sediments [

44]. Its origin is linked to crustal rifting, the exhumation of basement rocks, and structural deformation in a positive flower structure, with geological ages ranging from the Precambrian to the Tertiary, influenced by orogenic processes such as uplifts and foldings associated with the rise of the Andes [

40,

41].

Within La Macarena, denudational environments predominate, comprising 46.88% of the physiographic unit (

Figure 4). Prominent within this setting are dissected hills formed by intense denudational processes, occurring primarily in the northern sector, along the margin adjoining the High plains and adjacent to the floodplains of the Ariari, Guejar, and Guaduas rivers. Subdominant are undissected hills, associated with erosional and soil-creep processes, located mainly adjacent to the floodplains of

Caño Talanquera and the Cunimia, Guejar, and Guayabero rivers. Also noteworthy are erosive hillsides, predominantly situated in areas of lower elevation within both the massif and the cordillera.

The fluvial environment accounts for 43.83% of the La Macarena region, where floodplains predominate, primarily associated with the major river channels descending from the cordillera. Following in spatial extent are the ancient alluvial fans, located mainly in higher-altitude areas along the cordilleran margin, formed by sediment contributions from the Ariari, Uruime, Yamanito, Guape, Guejar, and Duda rivers. Additionally, sub-recent accumulation terraces are noteworthy, particularly those associated with the floodplains of the

Caño Berlín and the Guejar, Duda, Guayabero, Papamene, and Leiva rivers. The structural environment represents the smallest proportion of La Macarena, encompassing 9.29% of the area. It is characterized by structural hills distributed across much of the massif and by slopes defined by preferential planes parallel to the terrain’s dip, which are often located toward lower-altitude sectors of the massif. These structural units are linked to near-surface deformation processes and basement uplift [

40,

41].

3.3. Floodplain Geomorphology

The extent of the Floodplain was estimated at 52,187.13 km², representing 22.35% of the Orinoquia. This figure is consistent with the value reported by Jaramillo & Rangel-Ch. [

40,

41], although smaller than the 65,250 km² previously recorded for this physiographic unit by other authors [

45,

59]. The Floodplain lies on a lateral depression or sedimentary basin east of the Foothills, characterized by active subsidence, where Cretaceous and Tertiary epicontinental sediments— including volcanic materials—were initially deposited [

38,

44,

60]. This physiographic unit is associated with extensive terraces of poorly consolidated materials converging into a vast overflow plain marked by numerous levees and mobile sandbanks. These expand across longitudinal belts of residual Tertiary sedimentary layers, where distinct alluvial paleoforms occur. In the intermediate areas, known as bajos and esteros, seasonal flooding occurs during the rainy period [

36,

38,

64,

65]. Such conditions result in continuous shifts in river courses, where lateral sedimentation has left few significant traces due to the dominance of overbank deposits [

40,

41,

62,

65].

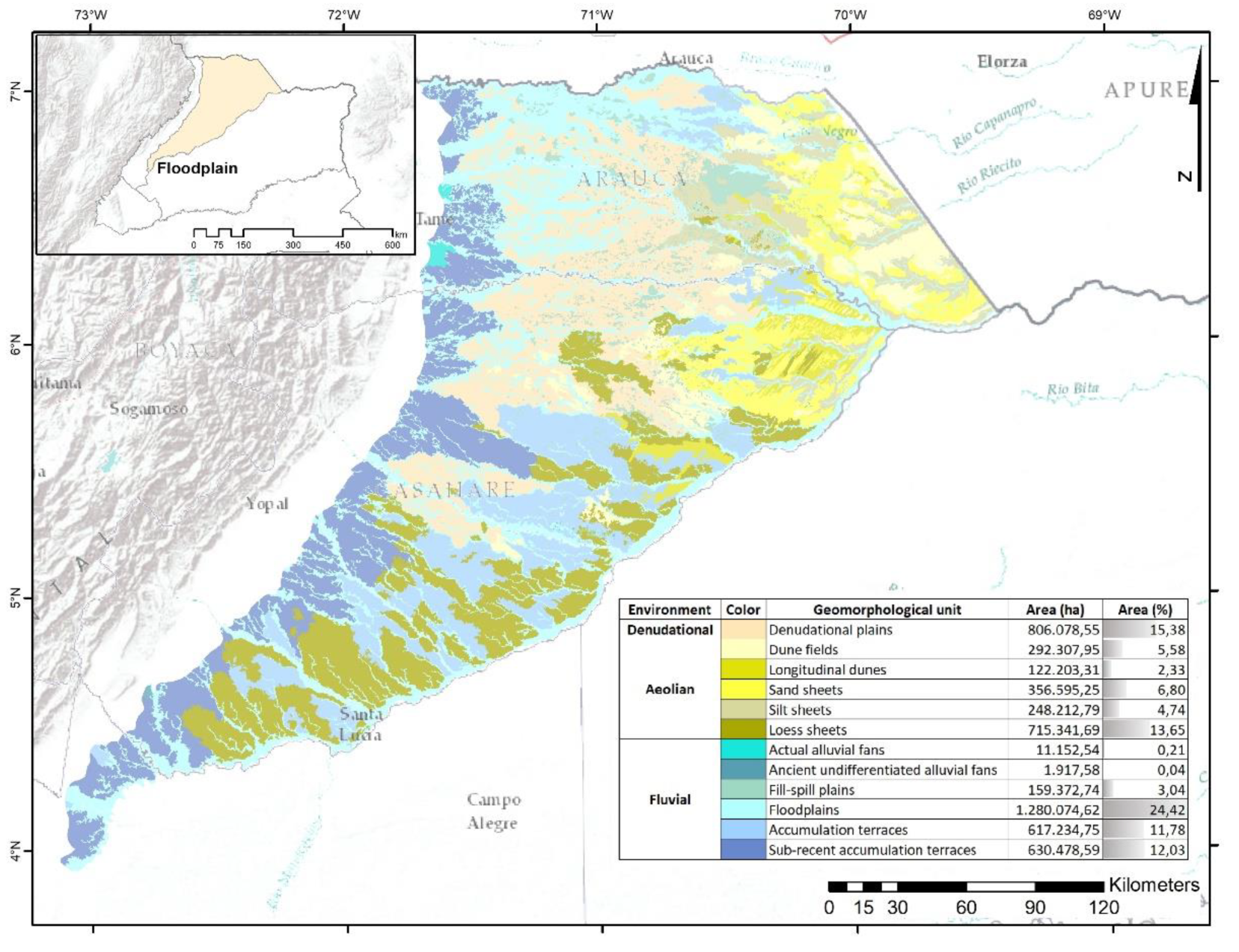

Within the Floodplain, the fluvial environment predominates, occupying 51.52% of its total area (

Figure 5). Floodplains dominate this environment and are closely associated with river channels descending from the cordillera. Toward the northwestern sector of the physiographic unit, these landforms cover larger areas than those observed in the south, forming a complex system of inundable zones affected by processes of overflow and alluviation. This is particularly evident in the areas associated with the Arauca, Lipa, Ele, Cravo Norte, Cusay, Cuiloto, Casanare, and Ariporo rivers, as well as their major tributaries—such as

Caño Colorado,

Caño Palmer,

Caño Caranal,

Caño Cuarteles, and

Caño Matepalma—where fill-spill plains are common, characterized by poor drainage, permanent saturation, and siltation processes [

36,

38,

62]. Sub-recent accumulation terraces follow in representativity. These are found in the higher-altitude zones of the unit, particularly along its western margin bordering the Foothills. In addition, recent accumulation terraces are frequently located in intermediate altitudinal sectors between the Foothills and the Meta River, where they are associated with aeolian processes [

65].

The aeolian environment extends across the eastern margin of the Floodplain, covering 17,346.60 km², equivalent to 33.10% of this physiographic unit. This area is 3,422.15 km² smaller than that reported by other authors [

45,

59]. Its origin is linked to the intense deposition of alluvial material transported during the Pleistocene and Holocene, which facilitated the development of extensive unconsolidated sediment covers. These deposits were subsequently reworked, transported, and redistributed by strong winds, reinforced by the marked alternation of dry and wet seasons that followed desertification phases [

38,

44,

62]. Within this environment, loess mantles are predominant. These were generated by aeolian suspension transport and subsequent compaction of silts over older sediments, under conditions favorable to deflation. They are primarily located in poorly drained flat areas along the southeastern margin of the Floodplain [

60,

62]. Following in extent are sand sheets, concentrated on the northeastern margin, and dune fields formed by sand mounds that frequently overlie preexisting landforms. These dunes occur in the northeasternmost sector of the unit, between the Meta and Arauca rivers, and are typically oriented by prevailing trade winds into elongated or longitudinal units up to 15 km long. Their morphology is further modified by surface runoff, which promotes the formation of rills and the deposition of sediments in interdune areas [

38,

60,

65,

66,

67].

Occupying the smallest proportion of the Floodplain, the denudational environment accounts for 15.38% of its area. It is represented exclusively by plains associated with floodplains in the northern sector, where complex fluvial systems frequently display channel bifurcations. These occur because the low-energy, weakly hierarchical drainage network lacks the capacity to effectively dissect the terrain [

36,

38,

65].

3.4. Geomorphology of the High plains

The High plains covers an estimated area of 141,487.71 km², representing 60.58% of the Orinoquia region. This figure is smaller than the previously reported extent of 188,668.61 km², equivalent to 62.50% of the region, which had included the terraces extending from the cordillera to the Metica River and from the Upía River to the Ariari River [

45,

59]. In the present study, these terraces are classified as Foothills. The origin of the High plains is associated with the compression of the proto-oceanic crust, its subsequent rupture, and the uplift of Tertiary sediments [

40,

41]. During the Tertiary and Pleistocene periods, extensive sedimentation occurred from the Andes to the Orinoco River, ultimately ceasing in the Pleistocene with the development of a fault along which the Meta River currently flows, separating the High plains from the Floodplain Llanos [

38,

60,

62,

68]. This physiographic unit is composed of sedimentary deposits originally accumulated in marine and coastal environments, subsequently redeposited following the uplift of the Eastern Cordillera, and subjected to prolonged weathering processes that have markedly reduced their mineralogical composition [

44]. This regional fault is tilted eastward and deeply incised by the channels that traverse it, shaping the High Plains into a large dissected alluvial fan characterized by landscape units of sierras interrupting the flat surface—a pattern explained by the genesis of these units over Precambrian basement rocks [

40,

41]. These geomorphic conditions define the landscape as a mosaic of low hills and rounded knolls, complemented by slopes of varying length, gradient, and morphology, interspersed with depressions and sinuous valleys amidst multiple domal structures [

44].

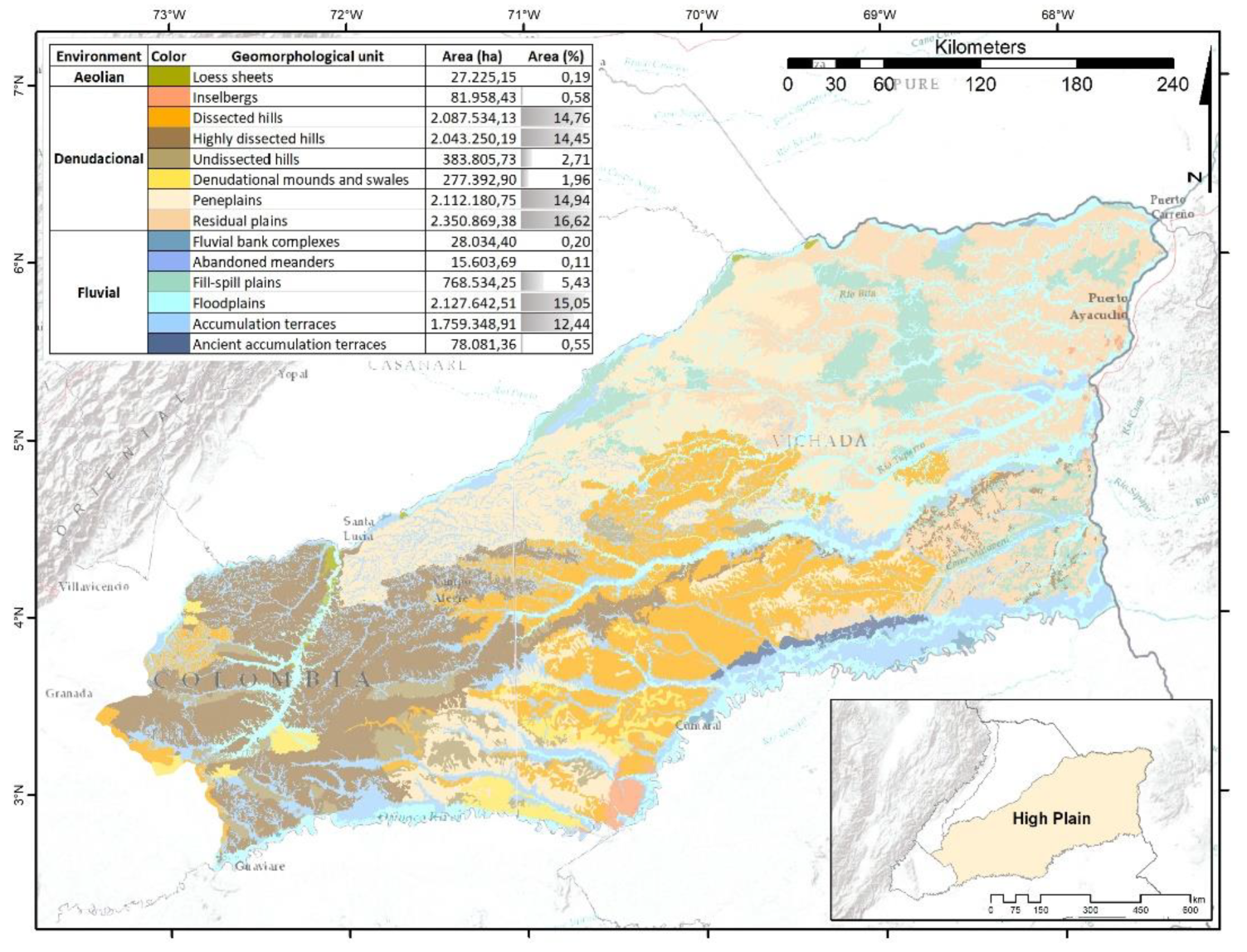

In the High plains, the denudational environment predominates, covering 66.03% of its extent (

Figure 6). The most geographically representative landforms are the residual plains, which comprise extensive areas located along the eastern margin of the subregion, within the influence zone of the Orinoco River. These residual plains are gently inclined, associated with ancient erosion surfaces and residual soils, and are composed of unconsolidated Quaternary fluvial sediments. They are frequently linked to the broad floodplains of the main Orinoco tributaries, to fill-spill plains developed on former overflow surfaces, and to terraces [

38,

60,

61]. The next most representative landforms are the extensive peneplains, located in the central margin under the influence of the Meta River, bounded to the east by the residual plains, to the west by the hill systems influenced by the Manacacías River, and to the south by the dissected hills influenced by the Vichada River. These peneplains exhibit undulating surfaces characterized by the recurrent presence of low hills and intermontane valleys that form a dense reticular drainage pattern, reflecting the dissection of an ancient high plain [

61].

Dissected and highly dissected hills account for approximately one-third of the High plains’s extent. These landforms consist of rounded elevations with short to moderate slopes, producing valleys through fluvial erosion of unconsolidated fine or granular Tertiary sediments and sub-dendritic drainage patterns [

61]. The highly dissected hills are concentrated along the western margin of the High plains, in the area influenced by the Manacacías River, and are characterized by steep, escarped slopes with strong dissection and V-shaped valleys. These landscapes often display advanced degradation stages resulting from diffuse and concentrated surface runoff, leading to the development of petroferrous crusts, gullies, and subsurface tunnels [

60]. In contrast, dissected hills are widely distributed across the central High plains, where they present inclined slopes with moderate dissection and U-shaped valleys, which may exhibit crusted margins and flat valley floors [

38].

The fluvial environment extends across 33.78% of the physiographic unit, with floodplains associated with the major channels constituting the most distinctive features. Next in spatial representativeness are the accumulation terraces, which reach their greatest extent in areas under the influence of the Guaviare River, south of the High plains. The aeolian environment is represented exclusively by loess mantles, occurring in low-gradient zones adjacent to floodplains near the confluence of the Manacacías River. These compacted silt sheets are homologous remnants of more extensive loessic formations to the north, across the Meta River, which characterize the southwestern margin of the Floodplain.

4. Discussion

The parameterization of the RF classifiers revealed that the optimal number of decision trees required to achieve the highest accuracies in the geomorphological models of the Orinoquia ranged from 50 in the Foothills to 120 in the High Plains. The overall accuracy of the models was calculated between 0.875 (Foothills) and 0.920 (Floodplain), indicating that the pixels classified within the training areas matched the predefined sample categories in a proportion ranging from 87.5% to 92.0% after classification.

SAR imagery proved to be highly effective for discriminating geomorphological units, particularly those associated with fluvial environments, even in regions covered by dense vegetation such as the southern High plains [

5,

6,

9]. Nevertheless, according to the confusion matrices, maximum omission errors of 28% and commission errors of 34% were identified, most of which were linked to fluvial environment units. The Kappa coefficient, which quantifies the difference between the accuracy of the automatic classifier and that of a random classification [

69,

70], indicated that the probability of achieving a correct classification, as compared to a classifier that assigns pixels randomly to geomorphological units, was at least 0.86 during the RF model runs.

Despite the higher degree of confusion observed among fluvial environment units, SAR imagery proved effective in discriminating floodplains from units belonging to other environments, owing to the dielectric properties of the terrain that reflect its moisture content [

18,

20,

71]. Another key aspect of SAR image implementation lies in the differentiated response of backscattered signals and their penetration capacity, which enables the discrimination of geomorphological units according to the texture of the prevailing material [

13,

15,

18,

52]. Grain size, in turn, is influenced by erosion and sedimentation processes, as well as transport distance.

The integration of L-band SAR imagery with Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and derived information constitutes an effective data source that complements traditional geomorphological interpretations [

4,

18,

19], which in the Orinoquia have been primarily based on optical imagery or aerial photographs [

61,

65,

68]. These digital methods of geomorphological analysis reduce the subjectivity inherent to visual classification, by implementing coherent and reproducible procedures in which the derivation of quantitative information from DEMs is essential [

27]. The application of multidimensional imagery enables the development and adoption of innovative technological approaches that integrate the potential of diverse data types while addressing associated technical challenges [

32]. Furthermore, increasing the number of variables incorporated into these models enhances overall accuracy and reduces variance during classifications [

23,

72].

Random sampling of training subsets met the requirements of objectivity, both for the estimates derived from the confusion matrix and for the Kappa statistic [

73,

74]. Nevertheless, during the definition of the training samples, certain rare classes with restricted spatial distribution were identified. Although sample acquisition was proportional to the landscape representativeness of the classes, future studies could consider stratified sampling designs to select training data based on existing thematic cartography, which would ensure the inclusion of training samples with greater accuracy regardless of their size [

22,

56]. Beyond its effectiveness as a classifier, the RF technique also enables the ranking of included variables according to their relevance in class discrimination, which may be particularly valuable for the incorporation of new variables or the refinement of those considered in this study [

24,

75].

The preservation of geomorphological and edaphic scenarios in this region is of paramount importance for sustaining the ecological processes that underpin the structure and dynamics of natural vegetation. These landforms and soil systems not only regulate hydrological and nutrient fluxes but also provide the foundational substrates that condition species distribution, community composition, and ecosystem resilience. In particular, the geomorphic heterogeneity enhances microenvironmental variability, fostering ecological niches that support high levels of biodiversity, while edaphic attributes determine the functional traits of plant assemblages and their adaptive responses to environmental stressors [

76]. Consequently, the integrity of these geomorphological and pedological units is critical for maintaining ecological stability, as their degradation could trigger cascading effects on vegetation cover, soil fertility, and hydrological balance. From a conservation perspective, safeguarding these physical and biotic interactions ensures the persistence of natural vegetation mosaics and secures their role in regulating carbon dynamics, sustaining habitat connectivity, and supporting long-term ecosystem services. Thus, the integration of geomorphological and edaphic conservation strategies into regional planning is essential to guarantee the ecological functionality and resilience of these landscapes under current and future environmental pressures [

77].

5. Conclusions

The spatial extent of the Orinoquia region in Colombia was delineated based on precise geomorphological criteria, particularly the abrupt slope changes along the Foothills, which enabled a clear separation of the Andean domain from the Orinoquia region. These topographic features exert a significant influence on the morphology of rivers transporting sediments from the cordillera, thereby reflecting the complex interaction between regional tectonics and the coupled processes of erosion and sedimentation. This dynamic is largely modulated by the underlying crustal flexure observed in the southern portion of the Orinoquia. Furthermore, a precise delimitation of the four physiographic units comprising the region is presented, along with a detailed characterization of the associated geomorphological environments. Within this framework, the structural environment, although geographically limited, is represented in the Foothills and La Macarena subregions; the fluvial environment predominates in the Foothills and Floodplain units; the denudational environment is more prominent in the High Plains (High plains) and La Macarena; and the aeolian environment constitutes a significant component of the Floodplain.

The predominance of fluvial landforms in the Foothills, together with the significant presence of accumulation terraces, alluvial fans, and floodplains, reveals a complex system in which erosion, sedimentation, and denudation processes interact continuously, influenced by abrupt slope changes and tectonic activity. This analysis underscores the influence of neotectonics and historical climatic variability on landscape formation in the Foothills. The torrential sediment load originating from the mountain range, which generates both actual and potential instability hazards, highlights the critical role of geomorphological information in environmental management, where it can contribute to: (i) the mitigation of natural risks associated with erosion, sedimentation, and fluvial evolution; (ii) watershed management and ecosystem conservation, including measures of restoration, preservation, and recreation; and (iii) the planning of sustainable productive activities, where geomorphological analysis assists in parameterizing landscape dynamics and sensitivity in order to understand the processes that sustain and influence ecological systems [

78,

79].

La Macarena was characterized as a Precambrian rock massif with a notable influence on orogenic processes throughout its geological evolution, where the dynamic interplay between denudation, fluvial sedimentation, and tectonics has shaped its present geomorphological configuration. The predominance of the denudational environment, which accounts for nearly half of La Macarena´s surface, underscores the intense geomorphic activity responsible for dissected hills and erosive hillsides. The resulting dynamics have produced a landscape marked by pronounced altitudinal contrasts and a complex drainage network. In relation to the fluvial environment, which encompasses almost the other half of La Macarena, floodplains and ancient alluvial fans highlight the continuous input of sediments from the adjacent cordillera a process that has facilitated the development of accumulation terraces and significantly transformed the landscape. Although the structural environment occupies the smallest area within La Macarena, it reflects the region’s tectonic history, which has strongly influenced the massif’s configuration. The structural hillsides and slopes reveal a past shaped by episodes of uplift and deformation that, in combination with erosion and sedimentation processes, have contributed to the region’s geomorphological diversity.

The Floodplain is situated atop a depression filled with Cretaceous and Tertiary sediments, where the fluvial environment predominates, occupying more than half of its surface area. This dominance highlights the prevalence of overbank flooding and lateral sedimentation processes in shaping a mosaic of landforms, ranging from floodplains to accumulation terraces. The occurrence of extensive loess sheets and dune fields, sculpted by strong winds and the alternation of dry and humid periods, underscores the significance of both historical and contemporary aeolian processes in configuring the surface of the Floodplain. Furthermore, the presence of complex fluvial systems, with a limited capacity to remodel the terrain, reflects the dynamics of the drainage network and its role in the development of floodplains.

The geological origin of the High plains, associated with episodes of compression, rupture of the proto-oceanic crust, and the uplift of Tertiary sediments, underscores the tectonic dynamics that have shaped this landscape. The presence of a fault separating the High plains from the Floodplain highlights the influence of deep geological processes on the current distribution of physiographic environments and regional hydrology. The predominance of a denudational setting in the High plains reveals a landscape dominated by erosion and the sculpting of relief ranging from gently rolling to highly dissected, where colluvial plains and peneplains define much of the subregion. These landforms, the outcome of a long history of sedimentation sourced from the Andes coupled with weathering processes, illustrate the complexity of interactions between geological and climatic processes over time. Fluvial and aeolian environments, although less extensive, are equally significant in the configuration of the High plains landscape. Floodplains and accumulation terraces emphasize the continuous influence of fluvial systems on the geomorphology of the region, whereas loess mantles reflect the role of wind dynamics and broader climatic patterns in sediment distribution.

The methodological contributions presented here demonstrate substantial potential for delineating the geographic distribution of geomorphological units at a regional scale. Random Forest modeling enabled the classification of stacked multidimensional imagery into discrete and representative units, corresponding to categories previously identified within the study area. Confusion matrices and their associated metrics indicated that the models achieved acceptable levels of accuracy, with the greatest misclassifications occurring among the fluvial environment units. The similarity between overall accuracy values and Kappa indices confirmed that the main diagonals of the confusion matrices are consistent with the distribution of values across the remaining matrix arrangements, further evidencing that pixel allocation among classes is not random.

The conservation of geomorphological and edaphic systems is not merely a matter of protecting abiotic structures, but rather a prerequisite for safeguarding the ecological processes that sustain natural vegetation in this region. By maintaining the integrity of soil–landform interactions, it is possible to preserve the functional heterogeneity that enables species persistence, regulates nutrient and water dynamics, and ensures long-term ecosystem resilience. Any deterioration of these foundational scenarios would compromise vegetation structure and ecological stability, with direct implications for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision. Therefore, prioritizing their protection represents a strategic imperative for both ecological research and regional environmental management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and formal analysis L.N. and V.M.-C.; investigation L.N, V.M.-C., J.O.R.-C., A.J.J., V.V. and D.S.-M.; data curation L.N, V.M.-C., J.O.R.-C., A.J.J., V.V. and D.S.-M.; writing—original draft preparation L.N, V.M.-C., J.O.R.-C., and D.S.-M.; writing—review and editing L.N, V.M.-C., J.O.R.-C., A.J.J., V.V. and D.S.-M.; visualization L.N, V.M.-C., J.O.R.-C., A.J.J., V.V. and D.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our profound appreciation to our academic institutions for their steadfast support and commitment, which have been instrumental in enabling the successful development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Steinhardt, U.; Herzog, F.; Lausch, A.; Müller, E.; Lehmann, S. Hemeroby Index for Landscape Monitoring and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Environmental Indices: Systems Analysis Approach; Pykh, Y., Hyatt, D., Lenz, R., Eds.; Oxford, EOLSS Publ.: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1999; pp. 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P.; Luchiari, A. Uso Das Imagens SAR R99B Para Mapeamento Geomorfológico Do Canal Do Ariaú No Município de Iranduba-AM. Rev. Geogr. 2017, 34, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroonenberg, S. Aporte de La Teledeteccion a La Geomorfologia. In Proceedings of the Primer simposio Colombiano sobre sensores remotos; Bogotá, Colombia; 1983; pp. 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.; Alves, P. A Utilização Dos Modelos SRTM Na Interpretação Geomorfológica: Técnicas e Tecnologias Aplicadas Ao Mapeamento Geomorfológico Do Território Brasileiro. In Proceedings of the Anais XIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais INPE: Florianópolis, Brasil, 2007; pp. 4261–4266. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, W. Uso Das Imagens SAR R99B Para Mapeamento Geomorfológico Do Furo Do Ariaú No Município de Iranduba-AM, Universidade de Sáo Paulo, 2013.

- Gallotti, T. Dados Multisensores Para Mapeamento Geomorfológico de Regiões Da Amazônia. In Proceedings of the VIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais INPE: Salvador, Brasil, 1996; pp. 629–630. [Google Scholar]

- Paradella, W.; Santos, A.; Veneziani, P.; Cunha, E. Radares Imageadores Nas Geociências: Status e Perspectivas. In Proceedings of the Anais XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais INPE: Goiânia, Brasil, 2005; pp. 1847–1854. [Google Scholar]

- Topouzelis, K.; Psyllos, A. Oil Spill Feature Selection and Classification Using Decision Tree Forest on SAR Image Data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2012, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, H.; Rossetti, D.; Cremon, E. Mapeamento Geomorfológico de Áreas Alagáveis Tropicais Com Imagens ALOS PALSAR. In Proceedings of the XVI Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto - SBSR; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais INPE: Foz do Iguaçu, Brasil, 2013; pp. 8453–8460. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P.; Samat, A.; Waske, B.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. Random Forest and Rotation Forest for Fully Polarized SAR Image Classification Using Polarimetric and Spatial Features. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Anderson, A.; Herndon, K.; Cherrington, E.; Thapa, R.; Kucera, L.; Quyen, N.; Odour, P.; Wahome, A.; Temeson, K.; Mamane, B.; et al. Introduction and Rationale. In The SAR handbook; Flores-Anderson, A., Herndon, K., Thapa, R., Cherrington, E., Eds.; SERVIR Global Science: Huntsville, EEUU, 2019; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Prats-Iraola, P.; Younis, M.; Krieger, G.; Hajnsek, I.; Papathanassiou, K. A Tutorial on Synthetic Aperture Radar. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2013, 1, 6–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F. Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar: Principles, Data Access, and Basic Processing Techniques. In The SAR handbook; Flores-Anderson, A., Herndon, K., Thapa, R., Cherrington, E., Eds.; SERVIR Global Science: Huntsville, EEUU, 2019; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S.; Butler, D.; Malanson, G. An Overview of Scale, Pattern, Process Relationships in Geomorphology: A Remote Sensing and GIS Perspective. Geomorphology 1998, 21, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwin, A.; Khaing, M. Yangon River Geomorphology Identification and Its Enviromental Imapacts Analsysi by Optical and Radar Sensing Techniques. In Proceedings of the XXII ISPRS Congress; The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences: Melbourne, Australia, 2012; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bocco, G.; Mendoza, M.; Velázquez, A. Remote Sensing and GIS-Based Regional Geomorphological Mapping—a Tool for Land Use Planning in Developing Countries. Geomorphology 2001, 39, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, C.; Riccomini, C.; Steiner, S. Aplicações Dos Modelos de Elevação SRTM Em Geomorfologia. Rev. Geogr. Acadêmica 2008, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Singhroy, V.; Assouad, P.; Barnett, P.; Molch, K. Terrain Interpretation from SAR Techniques. In Proceedings of the EEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Toulouse, France, 2003; pp. 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Pain, C. Applications of Remote Sensing in Geomorphology. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2009, 33, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.; Butler, D.; Malanson, G. An Overview of Scale, Pattern, Process Relationships in Geomorphology: A Remote Sensing and GIS Perspective. Geomorphology 1998, 21, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, Ö.; Güngör, O. Classification of Multispectral Images Using Random Forest Algorithm. J. Geod. Geoinf. 2012, 1, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S. Analysis of Machine Learning Classifiers for LULC Classification on Google Earth Engine, University of Twente, 2019.

- Waske, B.; Braun, M. Classifier Ensembles for Land Cover Mapping Using Multitemporal SAR Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2009, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguț, L. Random Forest in Remote Sensing: A Review of Applications and Futuredirections. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. Random Forest Classifier for Remote Sensing Classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGC Propuesta Metodológica Sistemática Para La Generación de Mapas Geomorfológicos Analíticos Aplicados a La Zonificación de Amenaza Por Movimientos En Masa Escala 1:100.000. Anexo A: Glosario de Términos Geomorfológicos.; Bogotá, Colombia, 2015.

- Franklin, S. Geomorphometric Processing of Digital Elevation Models. Comput. Geosci. 1987, 13, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.; Peddle, D. Texture Analysis of Digital Image Data Using Spatial Cooccurrence. Comput. Geosci. 1987, 13, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Google Earth Engine Applications Since Inception: Usage, Trends, and Potential. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Kumar, L. Google Earth Engine Applications. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, J.; Lucas, R.; Mitchell, A.; Verbesselt, J.; Hoekman, D.; Haarpaintner, J.; Kellndorfer, J.; Rosenqvist, A.; Lehmann, E.; Woodcock, C.; et al. Combining Satellite Data for Better Tropical Forest Monitoring. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, L.; Jaramillo, A.; Villamizar, V.; Rangel-Ch, J.O. Geomorphology, Land-Use, and Hemeroby of Foothills in Colombian Orinoquia: Classification and Correlation at a Regional Scale. Pap. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 9, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiano, Y.; Beaulieu, N. Uso de Las Imágenes Radarsat En La Cartografía de Unidades de Paisaje En La Orinoquia Colombiana. Estudio de Caso En El Municipio de Puerto López, Meta Proyecto Colombia 27. In Proceedings of the GLOBESAR 2"Aplicaciones de Radarsat en América Latina”; GLOBESAR:: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1999; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, L.; Beaulieu, N.; Rubiano, Y. Planificación En Los Llanos Colombianos Con Base En Unidades de Paisaje: El Caso de Puerto López, Meta. GeoTrópico 2004, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Villamizar, V. Evolución de Los Materiales Sedimentarios Del Cuaternario de La Llanura Aluvial Araucana, Colombia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2022.

- Goosen, D. Geomorfología de Los Llanos Orientales. Rev. Acad. Col. Ci. Ex. Fís. Nat. 1964, 12, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

-

IDEAM Sistemas Morfogénicos Del Territorio Colombiano; Flórez, A., Ed.; Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales IDEAM: Bogotá, Colombia, 2010; ISBN 978-958-8067-26-1.

- Hubach, E. Significado Geológico de La Llanura Oriental de Colombia; Instituto Geológico Nacional: Bogotá, Colombia, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A.; Rangel-Ch, J.O. Los Sistemas Fluviales de La Orinoquía Colombiana. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica Vol. XIV: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch, J.O., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014; pp. 71–99. ISBN 978-958-775-147-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A.; Rangel-Ch, J.O. Las Unidades Del Paisaje y Los Bloques Del Territorio En La Orinoquia. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica XIV: La región de la Orinoquia de Colombia; Rangel-Ch, J.O., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014; pp. 101–152. ISBN 978-958-775-147-5. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, V. Rasgos Geológicos de Los Llanos de Colombia Oriental. Inst. del Mus. la Univ. Nac. La Plata 1942, 21, 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Schargel, R. Geomorfología y Suelos de Los Llanos Venezolanos. In Tierras Llaneras de Venezuela; Hétier, J., López-Falcón, R., Eds.; Centro Interamericano de Desarrollo e Investigación Ambiental y Territorial CIDIAT: Mérida, Venezuela, 2015; pp. 63–125. [Google Scholar]

- Molano, J. Biogeografía de La Orinoquia Colombiana. In Colombia Orinoco; Fondo FEN: Bogotá, Colombia, 1998; pp. 69–101. [Google Scholar]

- FAO La Vegetación Natural y La Ganadería; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación FAO: Roma, Italia, 1965.

- Goosen, D. División Fisiográfica de Los Llanos Orientales. Rev. Nac. Agric. 1963, 55, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Ch, J.O.; Sánchez-C, H.; Lowy-C, P.; Aguilar-P, M.; Castillo, A. Región de La Orinoquia. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica Vol. I; Rangel-Ch, J.O., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá, Colombia, 1995; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rippstein, G.; Amézquita, E.; Escobar, G.; Grollier, C. Condiciones Naturales de La Sabana. In Agroecología y diversidad de las sabanas en los Llanos Orientales de Colombia; Rippstein, G., Escobar, G., Motta, F., Eds.; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 2001; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Botero, P. Proyecto Orinoquia-Amazonia Colombiana; Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi IGAC: Bogotá, Colombia, 1990.

- IDEAM Zonificación Hidrográfica de Colombia a Escala 1:100.000 Available online: http://www.siac.gov.co/.

- Farr, T.; Rosen, P.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raed, M.; Gari, J.; Berlles, J.; Sedeño, A.; Porta, P.; Delise, L.; Vicini, E.; Sánchez, L.; Iriondo, J.; Yebrin, J. Métodos de Clasificación Supervisada y No Supervisada de Imágenes SAR ERS 1/2. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of an lnternational Seminar on The Use and Applications of ERS in Latin America; European Space Agency: Viña del Mar, Chile, 1996; pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, P.; Wright, M.; Boulesteix, A. Hyperparameters and Tuning Strategies for Random Forest. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.; Woodcock, C.; Wulder, M. Good Practices for Estimating Area and Assessing Accuracy of Land Change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colditz, R. An Evaluation of Different Training Sample Allocation Schemes for Discrete and Continuous Land Cover Classification Using Decision Tree-Based Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2015, 9655–9681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Stehman, S.; Mountrakis, G. Assessing the Impact of Training Sample Selection on Accuracy of an Urban Classification: A Case Study in Denver, Colorado. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 26, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.; Stow, D.; Chen, J.; Lewison, R.; An, L.; Shi, L. Mapping Vegetation and Land Use Types in Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve Using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. Random Forest Classifier for Remote Sensing Classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, A. La Orinoquia Colombiana. Boletín la Soc. Geográfica Colomb. 1983, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, A. Colombia: Evolución de Sus Relieves y Modelados; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Unibiblos: Bogotá, Colombia, 2003; ISBN 958-701-312-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A.; Villamizar, V.; Lugo, O.; Vélez, A. Geología y Geomorfología En El Territorio de Las Selvas Transicionales de Cumaribo, Vichada (Colombia). In Colombia Diversidad Biótica Vol. XIX: Selvas transicionales de Cumaribo (Vichada - Colombia); Rangel-Ch, J.O., Andrade, G., Jarro, C., Santos, G., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Goosen, D. Physiography and Soils of the Llanos Orientales, Colombia; Publications of the International Institute for Aerial Survey and Earth Sciences (ITC); Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1971.

- Robertson, K. Morfotectónica y Dataciones Del Fallamiento Activo Del Piedemonte Llanero, Colombia, Sudamérica. Cuad. Geogr. 2007, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, L.; Vargas, G. Geomorfología Sísmica y Elementos En Ambientes Fluvio Lacustres En Un Sector de Los Llanos Orientales (Colombia). Boletín Ciencias La Tierra, 2018; 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, A.; Jaramillo, A.; Villamizar, V. Unidades Geomorfológicas Al Noreste Del Río Cravo Norte, Colombia. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica Vol. XX: Territorio sabanas y humedales de Arauca (Colombia); Rangel-Ch, J.O., Andrade, G., Jarro, C., Santos, G., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, R.; Salazar, S.; González, L.; Pacheco, H.; Suárez, C. Caracterización Geomorfológica de Las Dunas Longitudinales Del Istmo de Médanos, Estado Falcón, Venezuela. Investig. Geográficas 2011, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Armitage, S.; Berrío, J.; Bilbao, B.; Boom, A. An Optical Luminescence Chronology for Late Pleistocene Aeolian Activity in the Colombian and Venezuelan Llanos. Quat. Res. 2016, 85, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Rojas, D.; Díaz, J. Geología y Geomorfología de La Serranía de Manacacías (Meta) Orinoquia Colombiana. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica Vol. XVII: La región de la Serranía de Manacacías (Meta) Orinoquía colombiana; Rangel-Ch, J.O., Andrade, G., Jarro, C., Santos, G., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Plourde, L.; Congalton, R. Sampling Method and Sample Placement:How Do They Affect the Accuracy OfRemotely Sensed Maps? Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, G.; Fitzpatrick-Lins, K. A Coefficient of Agreement as Ameasure of Thematic Classification Accuracy. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1986, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, P.; Paradella, W. Recognition of the Main Geobotanical Features along the Bragança Mangrove Coast (Brazilian Amazon Region) from Landsat TM and RADARSAT-1 Data. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 10, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaes, X.; Vanhalle, L.; Defourny, P. Efficiency of Crop Identification Based on Optical and SAR Image Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.; Matzke, N.; de Souza, C.; Clark, M.; Numata, I.; Hess, L.; Roberts, D. Sources of Error in Accuracy Assessment of Thematic Land-Cover Maps in the Brazilian Amazon. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.; Czaplewski, R. Design and Analysis for Thematic Map Accuracy Assessment: Fundamental Principles. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.; Hirata, Y.; Ventura, L.; Serrudo, N. Natural Forest Mapping in the Andes (Peru): A Comparison of the Performance of Machine-Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias RAM, Rezende AV, Sevilha AC, Scariot AO, Matricardi EAT, Terribile LC. Geomorphological and Bioclimatic Relationships in the Occurrence of Species of Agro-Extractivist Interest in the Cerrado Biome. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3653. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Takahashi, F.; Dias, A.; Lima, T.; Alcântara, E. Machine Learning-Based Cerrado Land Cover Classification Using PlanetScope Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lóczy, D. Anthropogenic Geomorphology in Environmental Management. In Anthropogenic Geomorphology; Szabó, J., Dávid, L., Lóczy, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2010; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, P.; Booth, D. Geomorphology in Environmental Management. In The SAGE Handbook of Geomorphology; Gregory, K., Goudie, A., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2011; pp. 78–104. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).