Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Paradigm Shift of LC Management: Early Detection and Chemo-Immunotherapy

3. Lung Cancer Patients and Cardio-Immuno-Metabolic Risk

4. A Tale of Two Cities: Cardiovascular Toxicity of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Randomized Clinical Trials versus Real-World Practice

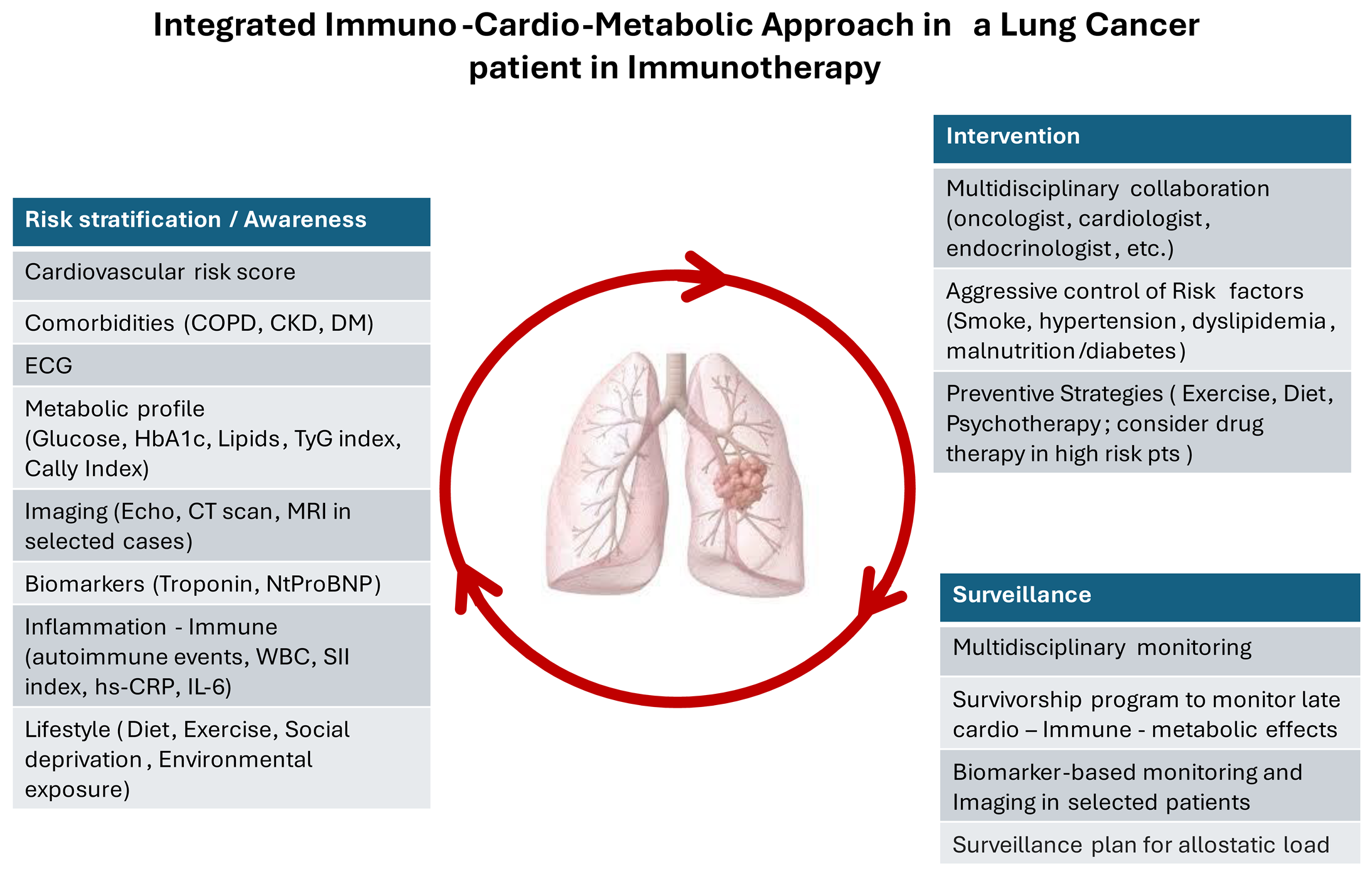

5. Management of Cardiovascular Risk and Toxicity in NSCLC Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors as First Line Therapy

Cardiovascular Events and Surgery in NSCLC

Pericarditis

6. Survivorship and Cardiovascular Surveillance

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May-Jun;74(3):229-263. Epub 2024 Apr 4. PMID: 38572751. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mo, S.; Yi, B. The spatiotemporal dynamics of lung cancer: 30-year trends of epidemiology across 204 countries and territories. BMC Public Health.2022; 22(1):987. PMID: 35578216; PMCID: PMC9109351. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025 Jan-Feb;75(1):10-45. Epub 2025 Jan 16. PMID: 39817679; PMCID: PMC11745215. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Deng, Y.; Tin, M.S.; Lok, V.; Ngai, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. 3rd; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; Elcarte, E.; et al. Distribution, Risk Factors, and Temporal Trends for Lung Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Analysis. Chest. 2022 Apr;161(4):1101-1111. Epub 2022 Jan 11. PMID: 35026300. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, P.F.; Geng, T.T.; Tu, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y.B.; Yu, H.C.; Zhang, J.J.; Guo, K.; Yang, K.; Liu, G.; et al. Trends in Self-Reported Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors Among US Adults, 1999 to March 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jul 3;6(7):e2323584. PMID: 37450300; PMCID: PMC10349344. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Li, M.; Ma, K.; Yin, J.; Zhan, C.; Wang, Q. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res. 2019 Jan 21;11:943-953. PMID: 30718965; PMCID: PMC6345192. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.N.; Zhang, Y.; Seal, B.; Ryan, K.; Yong, C.; Darilay, A.; Ramsey, S.D. Long-term survival trends in patients with unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy: a SEER cancer registry analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020 Apr 5;20(1):276. PMID: 32248816; PMCID: PMC7132866. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, K.A.; Puri, S.; Gray, J.E. Systemic and Radiation Therapy Approaches for Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Feb 20;40(6):576-585. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 34985931. [CrossRef]

- Ganti, A.K.; Klein, A.B.; Cotarla, I.; Seal, B.; Chou, E. Update of Incidence, Prevalence, Survival, and Initial Treatment in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Dec 1;7(12):1824-1832. PMID: 34673888; PMCID: PMC8532041. [CrossRef]

- Bei, Y.; Chen, X.; Raturi, V.P.; Liu, K.; Ye, S.; Xu, Q.; Lu, M. Treatment patterns and outcomes change in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in octogenarians and older: a SEER database analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021 Jan;33(1):147-156. Epub 2020 Apr 3. PMID: 32246386. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.T.; Jin, Y.; Lo, E.; Chen, Y.; Hanlon Newell, A.E.; Kong, Y.; Inge, L.J. Real-World Biomarker Test Utilization and Subsequent Treatment in Patients with Early-Stage Non-small Cell Lung Cancer in the United States, 2011-2021 Oncol Ther. 2023 Sep;11(3):343-360. Epub 2023 Jun 18. PMID: 37330972; PMCID: PMC10447355 . [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Forjaz, G.; Mooradian, M.J.; Meza, R.; Kong, C.Y.; Cronin, K.A.; et al. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 13;383(7):640-649. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.; Marmarelis, M.E.; Hwang, W.T.; Scholes, D.G.; McWilliams, T.L.; Singh, A.P.; Sun, L.; Kosteva, J.; Costello, M.R.; Cohen, R.B.; et al. Association Between Availability of Molecular Genotyping Results and Overall Survival in Patients with Advanced Non squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2023 Jul;7:e2300191. PMID: 37499192 . [CrossRef]

- Voruganti, T.; Soulos, P.R.; Mamtani, R.; Presley, C.J.; Gross, C.P.. Association Between Age and Survival Trends in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer After Adoption of Immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2023 Mar 1;9(3):334-341. PMID: 36701150; PMCID: PMC9880865. [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.; Hilberg, O.; Andersen, M.B.; Weinreich, U.M.; Rasmussen, T.R.; Increased use of computed tomography in Denmark: stage shift toward early stage lung cancer through incidental findings. Acta Oncol. 2022 Oct;61(10):1256-1262. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36264585. [CrossRef]

- Singareddy, A.; Flanagan, M.E.; Samson, P.P.; Waqar, S.N.; Devarakonda, S.; Ward, J.P.; Herzog, B.H.; Rohatgi, A.; Robinson, C.G.; Gao, F.; et al. Trends in Stage I Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2023 Mar;24(2):114-119. Epub 2022 Nov 21. PMID: 36504141. [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.L.; Rosenstein, A.L.; Kiang, M.V.; Shah, S.A.; Gaissert, H.A.; Chang, D.C.; Fintelmann, F.J.; Yang,C.J. Association of computed tomography screening with lung cancer stage shift and survival in the United States: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. 2022 Mar 30;376:e069008. PMID: 35354556; PMCID: PMC8965744 . [CrossRef]

- Bonney, A.; Malouf, R.; Marchal, C.; Manners, D.; Fong, K.M.; Marshall, H.M.; Irving, L.B.; Manser, R. Impact of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening on lung cancer-related mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Aug 3;8(8):CD013829. PMID: 35921047; PMCID: PMC9347663 . [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Patel, P.; Alpert, N.; Pyenson, B.; Taioli, E. Association of Stage Shift and Population Mortality Among Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Dec 1;4(12):e2137508. PMID: 34919136; PMCID: PMC8683966 . [CrossRef]

- Strongman, H.; Gadd, S.; Matthews, A.; Mansfield, K.E.; Stanway, S.; Lyon, A.R.; Dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Smeeth, L.; Bhaskaran, K. Medium and long-term risks of specific cardiovascular diseases in survivors of 20 adult cancers: a population-based cohort study using multiple linked UK electronic health records databases. Lancet. 2019 Sep 21;394(10203):1041-1054. Epub 2019 Aug 20. PMID: 31443926; PMCID: PMC6857444. [CrossRef]

- Florido, R.; Daya, N.R.; Ndumele, C.E.; Koton, S.; Russell, S.D.; Prizment, A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Matsushita, K.; Mok, Y.; Felix, A.S.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Cancer Survivors: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Jul 5;80(1):22-32. PMID: 35772913; PMCID: PMC9638987. [CrossRef]

- Ogedegbe, O.J.; Odugbemi, O.P.; Tabowei, G.; Alugba, G.; Pius, R.; Nwogwugwu, E.; Nwaezeapu, K.I. Rising Cardiovascular mortality in Lung cancer patients results from a large cancer database retrospective cohort study JACC 2025 Apr, 85 (12_Supplement) 2874. [CrossRef]

- Aberle, D.R.; Adams, A.M.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Clapp, J.D.; Fagerstrom, R.M.; Gareen, I.F.; Gatsonis, C.; Marcus, P.M.; Sicks, J.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395-409. Epub 2011 Jun 29. PMID: 21714641; PMCID: PMC4356534. [CrossRef]

- de Koning, H.J.; van Der Aalst, C.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 6;382(6):503-513. Epub 2020 Jan 29. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, D.E.; Reuland, D.S.; Reddy, S.M.; Nagle, M.; Clark, S.D.; Weber, R.P.; Enyioha, C.; Malo, T.L.; Brenner, A.T.; Armstrong, C.; et al. Screening for Lung Cancer With Low-Dose Computed Tomography: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021 Mar 9;325(10):971-987. PMID: 33687468. [CrossRef]

- Passiglia, F.; Cinquini, M.; Bertolaccini, L.; Del Re, M.; Facchinetti, F.; Ferrara, R.; Franchina, T.; Larici, A.R.; Malapelle, U.; Menis, J.; et al. Benefits and Harms of Lung Cancer Screening by Chest Computed Tomography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Aug 10;39(23):2574-2585. Epub 2021 Jun 2. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2021 Oct 1;39(28):3192-3193. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02078. PMID: 34236916. [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 10;375(19):1823-1833. Epub 2016 Oct 8. PMID: 27718847. [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Jul 20;39(21):2339-2349. Epub 2021 Apr 19. PMID: 33872070; PMCID: PMC8280089 . [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Gettinger, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Burgio, M.A.; de Castro Carpeno, J.; Pluzanski, A.; Arrieta, O.; Frontera, O.A.; Chiari, R.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;39(7):723-733. Epub 2021 Jan 15. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2021 Apr 1;39(10):1190. PMID: 33449799; PMCID: PMC8078445. [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Mar 1;37(7):537-546. Epub 2019 Jan 8. PMID: 30620668 . [CrossRef]

- Sezer, A.; Kilickap, S.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Feb 13;397(10274):592-604. PMID: 33581821. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 1;383(14):1328-1339. PMID: 32997907. [CrossRef]

- Novello, S.; Kowalski, D.M.; Luft, A.; Gümüş, M.; Vicente, D.; Mazières, J.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Tafreshi, A.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in squamous non–small-cell lung cancer: 5-year update of the phase III KEYNOTE-407 study. J Clin Onco. 2023; 41(11), 1999-2006.

- Garassino, M. C.; Gadgeel, S.; Speranza, G.; Felip, E.; Esteban, E.; Dómine, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; Bischoff, H.G.; Peled, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Apr 10;41(11):1992-1998. Epub 2023 Feb 21. PMID: 36809080; PMCID: PMC10082311. [CrossRef]

- Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze, T.; Makharadze, T.; Giorgadze, D.; Dvorkin, M.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2022 Nov;28(11):2374-2380. Epub 2022 Aug 25. PMID: 36008722; PMCID: PMC9671806. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; Peters, S.; Ortega Granados, A.L.; Pinto, G.D.J.; Fuentes, C.S.; Lo Russo, G.; Schenker, M.; Ahn, J.S.; Reck, M.; Szijgyarto, Z.; et al. Dostarlimab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in previously untreated metastatic non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer: the randomized PERLA phase II trial. Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 11;14(1):7301. PMID: 37951954; PMCID: PMC10640551. [CrossRef]

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. IMpower150 Study Group. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 14;378(24):2288-2301. Epub 2018 Jun 4. PMID: 29863955. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T. E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Feb;22(2):198-211. Epub 2021 Jan 18. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar;22(3):e92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00082-6. PMID: 33476593. [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.H.; Halmos, B.; Puri, S.; Qin, A.; Ismaila, N.; Abu Rous, F.; Alluri, K.; Freeman-Daily, J.; Malhotra, N.; Marrone, K.A.; et al. Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Without Driver Alterations: ASCO Living Guideline, Version 2025.1. J Clin Oncol. 2025 Aug 20;43(24):e45-e58. Epub 2025 Jul 17. PMID: 40674687. [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Yokoi, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; de Wit, M.; et al. PACIFIC Investigators. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 16;377(20):1919-1929. Epub 2017 Sep 8. PMID: 28885881 . [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Zhang Z, Bai M, Yan Y, Yu J, Xu Y. Radiation combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors for unresectable locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: synergistic mechanisms, current state, challenges, and orientations. Cell Commun Signal. 2023 May 23;21(1):119. PMID: 37221584; PMCID: PMC10207766. [CrossRef]

- Goldstraw, P.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Asamura, H.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Groome, P.; Mitchell, A.; Bolejack, V. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee Advisory Boards and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016 Jan;11(1):39-51. PMID: 26762738. [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, T. B.; Bandi, P.; Freedman, N. D.; Smith, R. A.; Travis, W. D.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R. Lung cancer statistics, 2023. Cancer, 2024;130(8):1330-1348.

- Almatrafi, A.; Thomas, O.; Callister, M.; Gabe, R.; Beeken, R. J.;Neal, R.. The prevalence of comorbidity in the lung cancer screening population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Screen. 2023 Mar;30(1):3-13. Epub 2022 Aug 9. PMID: 35942779; PMCID: PMC9925896. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Apple, J.; Belli, A.J.; Barcellos, A.; Hansen, E.; Fernandes, L.L.; Zettler, C.M.; Wang, C.K. Real-world study of disease-free survival & patient characteristics associated with disease-free survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective observational study. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2023;36:100742. Epub 2023 Jul 13. PMID: 37478531. [CrossRef]

- NSCLC Meta-analysis Collaborative Group. Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1561-1571. [CrossRef]

- Mountzios, G.; Remon, J.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; García-Campelo, R.; Rolfo, C.; Van Schil, P.; Forde, P.M.; Besse, B.; Subbiah, V.; Reck, M.; et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibition for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer - opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Oct;20(10):664-677. Epub 2023 Jul 24. PMID: 37488229. [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Taube, J.M.; Pardoll, D.M. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2020 Jan 31;367(6477):eaax0182. PMID: 32001626; PMCID: PMC7789854. [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Felip, E.; Broderick, S.R.; Brahmer, J.R.; Swanson, S.J.; et al. CheckMate 816 Investigators. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 May 26;386(21):1973-1985. Epub 2022 Apr 11. PMID: 35403841; PMCID: PMC9844511. [CrossRef]

- Heymach, J.V.; Harpole, D.; Mitsudomi, T.; Taube, J.M.; Galffy, G.; Hochmair, M.; Winder, T.; Zukov, R.; Garbaos, G.; Gao, S.; et al. AEGEAN Investigators. Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023 Nov 2;389(18):1672-1684. Epub 2023 Oct 23. PMID: 37870974. [CrossRef]

- Wakelee, H.; Liberman, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Lee, S.H.; Gao, S.; Chen, K.N.; Dooms, C.; Majem, M.; Eigendorff, E.; et al. KEYNOTE-671 Investigators. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023 Aug 10;389(6):491-503. Epub 2023 Jun 3. PMID: 37272513; PMCID: PMC11074923 . [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Neotorch Investigators; Fang, W.; Xing, W.; Chen, Q.; Yang, L.; Mei, J.; et al. Perioperative Toripalimab Plus Chemotherapy for Patients With Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Neotorch Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024 Jan 16;331(3):201-211. Erratum in: JAMA. 2025 Mar 11;333(10):910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.0962. PMID: 38227033; PMCID: PMC10792477. [CrossRef]

- Riely, G.J.; Wood, D.E.; Ettinger, D.S.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024 May;22(4):249-274. PMID: 38754467. [CrossRef]

- Bott, M.J.; Yang, S.C.; Park, B.J.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Rusch, V.W.; Isbell, J.M.; Downey, R.J.; Brahmer, J.R.; Battafarano, R.; Bush, E.; et al. Initial results of pulmonary resection after neoadjuvant nivolumab in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Jul;158(1):269-276. Epub 2018 Dec 13. PMID: 30718052; PMCID: PMC6653596. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Owen, D.H.; Merritt, R.E.; Shilo, K.; Otterson, G.A.; D'Souza, D.M.; Carbone, D.P.; Kneuertz, P.J.. Minimally Invasive Lobectomy for Residual Primary Tumors of Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer After Treatment With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Case Series and Clinical Considerations. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020 Jul;21(4):e265-e269. Epub 2020 Feb 25. PMID: 32184051. [CrossRef]

- Sepesi, B.; Zhou, N.; William, W.N.Jr; Lin, H.Y.; Leung, C.H.; Weissferdt, A.; Mitchell, K.G.; Pataer, A.; Walsh, G.L.; Rice, D.C.; et al. Surgical outcomes after neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab with ipilimumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022 Nov;164(5):1327-1337. Epub 2022 Jan 23. PMID: 35190177; PMCID: PMC10228712. [CrossRef]

- Wislez, M.; Mazieres, J.; Lavole, A.; Zalcman, G.; Carre, O.; Egenod, T.; Caliandro, R.; Dubos-Arvis, C.; Jeannin, G.; Molinier, O.; et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from a multicenter study (IFCT-1601 IONESCO). J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Oct;10(10):e005636. PMID: 36270733; PMCID: PMC9594538. [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, S.; Mehilli, J.; Cassese, S.; Hall, T.S.; Abdelhamid, M.; Barbato, E.; De Hert, S.; de Laval, I.; Geisler, T.; Hinterbuchner, L.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2022 Oct 14;43(39):3826-3924. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2023 Nov 7;44(42):4421. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad577. PMID: 36017553. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Cordoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. 2022 Nov 1;43(41):4229-4361. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2023 May 7;44(18):1621. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad196. PMID:36017568. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Blake, S.J.; Yong, M.C.; Harjunpää, H.; Ngiow, S.F.; Takeda, K.; Young, A.; O'Donnell, J.S.; Allen, S.; Smyth, M.J.; et al. Improved Efficacy of Neoadjuvant Compared to Adjuvant Immunotherapy to Eradicate Metastatic Disease. Cancer Discov. 2016 Dec;6(12):1382-1399. Epub 2016 Sep 23. PMID: 27663893. [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Rozeman, E.A.; Fanchi, L.F.; Sikorska, K.; van de Wiel, B.; Kvistborg, P.; Krijgsman, O.; van den Braber, M.; Philips, D.; Broeks, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med. 2018 Nov;24(11):1655-1661. Epub 2018 Oct 8. PMID: 30297911. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, A.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, H.; Du, W.; Luo, L.; Fu, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. . Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant vs Neoadjuvant-Only PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors for Patients With Resectable NSCLC: An Indirect Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e241285. PMID: 38451524; PMCID: PMC10921251. [CrossRef]

- Felip, E.; Altorki, N.; Zhou, C.; Csőszi, T.; Vynnychenko, I.; Goloborodko, O.; Luft, A.; Akopov, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Kenmotsu, H.; et al. IMpower010 Investigators. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021 Oct 9;398(10308):1344-1357. Epub 2021 Sep 20. Erratum in: Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02135-8. PMID: 34555333. [CrossRef]

- Felip, E.; Altorki, N.; Zhou, C.; Vallières, E.; Csoszi, T.; Vynnychenko, I.O.; Goloborodko, O.; Rittmeyer, A.; Reck, M.; Martinez-Marti, A.; et al. IMpower010 Study Investigators. Five-Year Survival Outcomes With Atezolizumab After Chemotherapy in Resected Stage IB-IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (IMpower010): An Open-Label, Randomized, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2025 May 30:JCO2401681. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40446184. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, M.; Paz-Ares, L.; Marreaud, S.; Dafni, U.; Oselin, K.; Havel, L.; Esteban, E.; Isla, D.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Faehling, M.; et al. EORTC-1416-LCG/ETOP 8-15 – PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022 Oct;23(10):1274-1286. Epub 2022 Sep 12. PMID: 36108662. [CrossRef]

- LBA48 CCTG BR.31: A global, double-blind placebo-controlled, randomized phase III study of adjuvant durvalumab in completely resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Goss, G.; Darling, G.E.; Westeel, V.; Nakagawa, K.; Massuti Sureda,B.; Perrone, F.; McLachlan, S-A.; Kang,J.H.; Dingemans, A-M.C.; et al. Annals of Oncology, Volume 35, S1238 (abs).

- Cascone, T.; Awad, M.M.; Spicer, J.D.; He, J.; Lu, S.; Sepesi, B.; Tanaka, F.; Taube, J.M.; Cornelissen, R.; Havel, L.; et al. CheckMate 77T Investigators. Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024 May 16;390(19):1756-1769. PMID: 38749033. [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.D.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Wang, C.; Lu, S.; Felip, E.; Swanson, S.J.; Brahmer, J.R.; et al. CheckMate 816 Investigators. Overall Survival with Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025 Aug 21;393(8):741-752. Epub 2025 Jun 2. PMID: 40454642. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, N.M.L.; Welch, C.A.; Sweeting, M.; de Belder, M.; Deanfield, J.; Weston, C.; Peake, M.D.; Adlam, D.; Ring, A. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Potentially Curable Malignancies: A National Registry Dataset Analysis. JACC CardioOncol. 2022 Jun 21;4(2):238-253.

- Kravchenko, J.; Berry, M.; Arbeev, K.; Lyerly, H.K.; Yashin, A.; Akushevich, I. Cardiovascular comorbidities and survival of lung cancer patients: Medicare data-based analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015 Apr;88(1):85-93.

- Mitchell, J.D.; Laurie, M.; Xia, Q.; Dreyfus, B.; Jain, N.; Jain, A.; Lane, D.; Lenihan, D.J. Risk profiles and incidence of cardiovascular events across different cancer types. ESMO Open. 2023 Dec;8(6):101830.

- Iachina, M.; Jakobsen, E.; Møller, H.; Lüchtenborg, M.; Mellemgaard, A.; Krasnik, M.; Green, A. The effect of different comorbidities on survival of non-small cells lung cancer patients. Lung. 2015 Apr;193(2):291-7.

- Sun, J.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Qu, Q.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.M.; Miao, L.F.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; et al. Cardiovascular disease-specific mortality in 270,618 patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cardiol. 2021 May 1;330:186-193.

- Batra, A.; Sheka, D.; Kong, S.; Cheung, W.Y. Impact of pre-existing cardiovascular disease on treatment patterns and survival outcomes in patients with lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020 Oct 15;20(1):1004.

- Kobo, O.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z. Gevaert, S.; Rana, J.S.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Roguin, A.; Petersen, S.E.; Ky, B.; Mamas, M.A. Impact of cancer diagnosis on distribution and trends of cardiovascular hospitalizations in the USA between 2004 and 2017. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022 Oct 26;8(7):787-797.

- Bell, C.F.; Lei, X.; Haas, A.; Baylis, R.A.; Gao, H.; Luo, L.; Giordano, S.H.; Wehner, M.R.; Nead, K.T.; Leeper, N.J.. Risk of Cancer After Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Disease. JACC CardioOncol. 2023 Apr 11;5(4):431-440.

- Leiter, A.; Veluswamy, R.R.; Wisnivesky, J.P. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep;20(9):624-639. Epub 2023 Jul 21. PMID: 37479810 . [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.; López-Cuadrado, T.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Galán, I. Clustering of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, self-rated health and disability. Prev Med. 2022 Feb;155:106911. Epub 2021 Dec 16. PMID: 34922996. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Rogers, K.; van der Ploeg, H.; Stamatakis, E.; Bauman, A.E.; Traditional and Emerging Lifestyle Risk Behaviors and All-Cause Mortality in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence from a Large Population-Based Australian Cohort. PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 8;12(12):e1001917. PMID: 26645683; PMCID: PMC4672919. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.C.; Lee, I.M.; Weiderpass, E.; Campbell, P.T.; Sampson, J.N.; Kitahara, C.M.; Keadle, S.K.; Arem. H.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Hartge, P.; et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity With Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jun 1;176(6):816-25. PMID: 27183032; PMCID: PMC5812009. [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.J.; Gao, Q.; Qiao, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C.P.; Liu, J. Red and processed meat consumption and the risk of lung cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of 33 published studies. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014 Jun 15;7(6):1542-53. PMID: 25035778; PMCID: PMC4100964.

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021 Sep;36(9):937-951. Epub 2021 Aug 29. PMID: 34455534. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.R.; Abar, L.; Vingeliene, S.; Chan, D.S.; Aune, D.; Navarro-Rosenblatt, D.; Stevens, C.; Greenwood, D.; Norat, T. Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016 Jan;27(1):81-96. Epub 2015 Sep 14. PMID: 26371287. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, T.; Guo, X.F.; Li D. The Associations of Fruit and Vegetable Intake with Lung Cancer Risk in Participants with Different Smoking Status: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 2;11(8):1791. PMID: 31382476; PMCID: PMC6723574. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, C.; Ji, M.; Fan, J.; Xie, J.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Yin, R.; Du, L, et al. Diet and Risk of Incident Lung Cancer: A Large Prospective Cohort Study in UK Biobank. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021 Dec 1;114(6):2043-2051. PMID: 34582556. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cao, S.M.; Dimou, N.; Wu, L.; Li, J.B.; Yang, J. Association of Metabolic Syndrome with Risk of Lung Cancer: A Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study. Chest. 2024 Jan;165(1):213-223. Epub 2023 Aug 10. PMID: 37572975; PMCID: PMC10790176. [CrossRef]

- Sin, S.; Lee, C.H.; Choi, S.M.; Han, K.D.; Lee, J. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of Lung Cancer: An Analysis of Korean National Health Insurance Corporation Database. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Nov 1;105(11):dgaa596. PMID: 32860708. [CrossRef]

- López-Jiménez, T.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Plana-Ripoll, O.; Recalde, M.; Xavier-Cos, F.; Puente, D. Association between metabolic syndrome and 13 types of cancer in Catalonia: A matched case-control study. PLoS One. 2022 Mar 4;17(3):e0264634. PMID: 35245317; PMCID: PMC8896701. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Tan, S.; Zhao, X.; Hou, A. Association between insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and its components and lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024 Mar 11;16(1):63. PMID: 38468310; PMCID: PMC10926619. [CrossRef]

- Shen, E.; Chen, X. Prediabetes and the risk of lung cancer incidence and mortality: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2023 Oct;14(10):1209-1220. Epub 2023 Jul 30. PMID: 37517054; PMCID: PMC10512911. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zuo, F.; Wen, X.; Wu, D.; Sun, X.; Liu, C. The association between metabolic syndrome and lung cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 18;14(1):28494. PMID: 39558018; PMCID: PMC11574301. [CrossRef]

- Carreras-Torres, R.; Johansson, M.; Haycock, P.C.; Wade, K.H.; Relton, C.L.; Martin, R.M.; Davey Smith, G.; Albanes, D.; Aldrich, M.C.; Andrew, A.; et al. Obesity, metabolic factors and risk of different histological types of lung cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One. 2017 Jun 8;12(6):e0177875. PMID: 28594918; PMCID: PMC5464539. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, G.; Hung, R.J.; Haycock, P.C.; Aldrich, M.C.; Andrew, A.S.; Arnold, S.M.; Bickeböller, H.; Bojesen, S.E.; Brennan, P.; et al. Causal relationships between body mass index, smoking and lung cancer: Univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization. Int J Cancer. 2021 Mar 1;148(5):1077-1086. Epub 2020 Sep 23. PMID: 32914876; PMCID: PMC7845289. [CrossRef]

- Caan, B.J.; Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Kroenke, C.H. The Importance of Body Composition in Explaining the Overweight Paradox in Cancer-Counterpoint. Cancer Res. 2018 Apr 15;78(8):1906-1912. PMID: 29654153; PMCID: PMC5901895. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, K.; Du, X.; Chen, G.; Shi, M.; Shi, B. Abdominal Obesity and Lung Cancer Risk: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients. 2016 Dec 15;8(12):810. PMID: 27983672; PMCID: PMC5188465. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zheng, W.; Johansson, M.; Lan, Q.; Park, Y.; White, E.; Matthews, C.E.; Sawada, N.; Gao, Y.T.; Robien, K.; et al. Overall and Central Obesity and Risk of Lung Cancer: A Pooled Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018 Aug 1;110(8):831-842. PMID: 29518203; PMCID: PMC6093439. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Jonsson, H.; Nagel, G.; Häggström, C.; Manjer, J.; Ulmer, H.; Engeland, A.; Zitt, E.; Jochems, S.H.J.; Ghaderi, S.; et al. The Inverse Association of Body Mass Index with Lung Cancer: Exploring Residual Confounding, Metabolic Aberrations and Within-Person Variability in Smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021 Aug;30(8):1489-1497. Epub 2021 Jun 22. PMID: 34162656. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Spitz, M.R.; Mistry, J.; Gu, J.; Hong, W.K.; Wu, X. Plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor-I and lung cancer risk: a case-control analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Jan 20;91(2):151-6. PMID: 9923856. [CrossRef]

- Favoni, R.E.; de Cupis, A.; Ravera, F.; Cantoni, C.; Pirani, P.; Ardizzoni, A.; Noonan, D.; Biassoni, R. Expression and function of the insulin-like growth factor I system in human non-small-cell lung cancer and normal lung cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1994 Mar 15;56(6):858-66. PMID: 7509779. [CrossRef]

- Dziadziuszko, R.; Camidge, D.R.; Hirsch, F.R.; The insulin-like growth factor pathway in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008 Aug;3(8):815-8. PMID: 18670298. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Shen, Y.; Tan, L.; Li, W. Prognostic Value of Sarcopenia in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2019 Jul;156(1):101-111. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31128115. [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A. A.; Alfaraidhy, M.; AlHajri, N.; Rohant, N. N.; Kumar, M.; Al Malouf, C.; Bahrainy, S.; Ji Kwak, M.; Batchelor, W.B.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation. 2023 May 16;147(20):1534-1553. Epub 2023 May 15. PMID: 37186680; PMCID: PMC10180053 . [CrossRef]

- Afzali, A.M.; Müntefering, T.; Wiendl, H.; Meuth, S.G.; Ruck, T. Skeletal muscle cells actively shape (auto)immune responses. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 May;17(5):518-529. Epub 2018 Mar 9. PMID: 29526638. [CrossRef]

- Montano, M.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Maladaptive Immune Activation in Age-Related Decline of Muscle Function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Jun 16;78(Supplement_1):19-24. PMID: 37325961; PMCID: PMC10272988. [CrossRef]

- Pillon, N.J.; Bilan, P.J.; Fink, L.N.; Klip, A. Cross-talk between skeletal muscle and immune cells: muscle-derived mediators and metabolic implications. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Mar 1;304(5):E453-65. Epub 2012 Dec 31. PMID: 23277185. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Choi, K.M. Interplay of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue: sarcopenic obesity. Metabolism. 2023 Jul;144:155577. Epub 2023 Apr 29. PMID: 37127228. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Xu, S. Sarcopenia affects clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020 Nov;88:106907. Epub 2020 Sep 18. PMID: 33182031 . [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Shen, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhou, T. Sarcopenia as a Determinant of the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2023;75(2):685-695. Epub 2022 Dec 19. PMID: 36533715 . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Chang, J.; Qin, Y.; Li, C. Impact of BMI on the survival outcomes of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2023 Oct 23;23(1):1023. PMID: 37872469; PMCID: PMC10594865. [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, D.; Björck, M.; Säwe, J.; Troëng, T. Randomized trials or population-based registries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007 Sep;34(3):253-6. PMID: 17689818. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. R.; Liu, C.; Hripcsak, G.; Cheung, Y.K.; Weng, C. Comparison of clinical characteristics between clinical trial participants and nonparticipants using electronic health record data. JAMA Network Open, 2021;4(4):e214732-e214732.

- Bonsu, J.; Charles, L.; Guha, A.; Awan, F.; Woyach, J.; Yildiz, V.; Wei, L.; Jneid, H.; Addison, D. Representation of patients with cardiovascular disease in pivotal cancer clinical trials. Circulation. 2019 May 28;139(22):2594-2596. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30882246; PMCID: PMC8244729. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Sivakumar, S.; Segelov, E.; Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A. J. Cardiovascular risk factor reporting in immune checkpoint inhibitor trials: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology, 2023;83, 102334.

- Johnson, D.B.; Balko, J.M.; Compton, M.L.; Chalkias, S.; Gorham, J.; Xu, Y.; Hicks, M.; Puzanov, I.; Alexander, M.R.; Bloomer, T.L.; et al. Fulminant Myocarditis with Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 3;375(18):1749-1755. PMID: 27806233; PMCID: PMC5247797. [CrossRef]

- Agostinetto, E.; Eiger, D.; Lambertini, M.; Ceppi, M.; Bruzzone, M.; Pondé, N.; Plummer, C.; Awada, A.H.; Santoro, A.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; et al Cardiotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2021 May;148:76-91. Epub 2021 Mar 16. PMID: 33740500. [CrossRef]

- Rahouma, M.; Karim, N.A.; Baudo, M.; Yahia, M.; Kamel, M.; Eldessouki, I.; Abouarab, A.; Saad, I.; Elmously, A.; Gray, K.D.; et al. Cardiotoxicity with immune system targeting drugs: a meta-analysis of anti-PD/PD-L1 immunotherapy randomized clinical trials. Immunotherapy. 2019 Jun;11(8):725-735. PMID: 31088241. [CrossRef]

- Kanji, S.; Morin, S.; Agtarap, K.; Purkayastha, D.; Thabet, P.; Bosse, D.; Wang, X.; Lunny, C.; Hutton, B. Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Overview of Systematic Reviews. Drugs. 2022 May;82(7):793-809. Epub 2022 Apr 13. PMID: 35416592. [CrossRef]

- Malaty, M.M.; Amarasekera, A.T.; Li, C.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Tan, T. C. Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor mediated cardiovascular toxicity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2022 Dec;52(12):e13831. Epub 2022 Jul 21. PMID: 35788986. [CrossRef]

- Naqash, A.R.; Moey, M.Y.Y; Cherie Tan, X.W.; Laharwal, M.; Hill, V.; Moka, N.; Finnigan, S.; Murray, J.; Johnson, D.B.; Moslehi, J.J.; et al. Major Adverse Cardiac Events With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Pooled Analysis of Trials Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute-Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Oct 10;40(29):3439-3452. Epub 2022 Jun 4. PMID: 35658474; PMCID: PMC10166352 . [CrossRef]

- Dolladille, C.; Akroun, J.; Morice, P. M.; Dompmartin, A.; Ezine, E.; Sassier, M.; Da-Silva, A.; Plane, A.F.; Legallois, D.; L'Orphelin, J.M.; et al. Cardiovascular immunotoxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a safety meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021 Dec 21;42(48):4964-4977. PMID: 34529770. [CrossRef]

- Salem, J.E.; Manouchehri, A.; Moey, M.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Bastarache, L.; Pariente A.; Gobert, A.; Spano, J.P.; Balko, J.M.; Bonaca, M.P.; et al. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Dec;19(12):1579-1589. Epub 2018 Nov 12. PMID: 30442497; PMCID: PMC6287923. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Yuan, Y.; Eccles, L.; Chitkara, A.; Dalén, J.; Varol, N. Treatment patterns for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the US: A systematic review of observational studies. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;33:100648. Epub 2022 Oct 13. PMID: 36270164. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.; Bortolini, M.; Calleja, A.; Munro, R.; Kong, S.; Daumont, M.J.; Penrod, J.R.; Lakhdari, K.; Lacoin, L.; Cheung, W.Y. Trends in treatment patterns and survival outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a Canadian population-based real-world analysis. BMC Cancer. 2022 Mar 10;22(1):255. PMID: 35264135; PMCID: PMC8908553. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. E.; Kumar, A.; Guo, J. J. Spending, utilization, and price trends for immune checkpoint inhibitors in US medicaid programs: an empirical analysis from 2011 to 2021. Clinical Drug Investigation, 2023;43(4), 289-298.

- Hektoen, H.H.; Tsuruda, K.M.; Fjellbirkeland, L.; Nilssen, Y.; Brustugun, O.T.; Andreassen, B.K. Real-world evidence for pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2025 Jan;132(1):93-102. Epub 2024 Nov 3. PMID: 39489879; PMCID: PMC11724112. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Dec 20;39(36):4073-4126. Epub 2021 Nov 1. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2022 Jan 20;40(3):315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02786. PMID: 34724392. [CrossRef]

- Power, J.R.; Dolladille, C.; Ozbay, B.; Procureur, A.; Ederhy, S.; Palaskas, N.L.; Lehmann, L.H.; Cautela, J.; Courand, P.Y.; Hayek, S.S.; et al. International ICI-Myocarditis Registry. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis: a novel risk score. Eur Heart J. 2025 Jun 18:ehaf315. Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2025 Jul 22:ehaf529. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf529. PMID: 40569849 . [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, J.J.; Salem, J.E.; Sosman, J.A.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Johnson, D.B. Increased reporting of fatal immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Lancet 2018; 391(10124): 933.

- Gougis, P.; Jochum, F.; Abbar, B.; Dumas, E.; Bihan, K.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Moslehi, J.; Spano, J.P.; Laas, E.; Hotton, J.; et al. Clinical spectrum and evolution of immune-checkpoint inhibitors toxicities over a decade-a worldwide perspective. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Mar 22;70:102536. PMID: 38560659; PMCID: PMC10981010. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Bugarin, J.G.; Guha, A.; Jain, C.; Patil, N.; Shen, T.; Stanevich, I.; Nikore, V.; Margolin, K.; Ernstoff, M.; et al. Cardiovascular adverse events are associated with usage of immune checkpoint inhibitors in real-world clinical data across the United States. ESMO Open. 2021 Oct;6(5):100252. Epub 2021 Aug 27. Erratum in: ESMO Open. 2021 Dec;6(6):100286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100286. PMID: 34461483; PMCID: PMC8403739. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lin, J.; Wang, B.; Huang, S.; Liu, M.; Yang, J. Clinical characteristics and influencing factors of anti-PD-1/PD-L1-related severe cardiac adverse event: based on FAERS and TCGA databases. Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 27;14(1):22199. PMID: 39333574; PMCID: PMC11436968 . [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, M.; Nielsen, D.; Svane, I. M.; Iversen, K.; Rasmussen, P.V.; Madelaire, C.; Fosbøl, E.; Køber, L.; Gustafsson, F.; Andersson, C.; et al. The risk of cardiac events in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a nationwide Danish study. Eur Heart J. 2021 Apr 21;42(16):1621-1631. PMID: 33291147. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B.; Zhi, Y.; Chen, M.; Zeng, J.; Jiao, Q.; Tao, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, Z.; et al. Association among major adverse cardiovascular events with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2025 Jan;297(1):36-46. Epub 2024 Nov 13. PMID: 39537368. [CrossRef]

- Delombaerde, D.; Oeste, C.L.; Geldhof, V.; Croes, L.; Bassez, I.; Verbiest, A., Tack, L.; Hens, D.; Franssen, C.; Debruyne, P.R.; et al. Cardiovascular toxicities in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: multicenter study using natural language processing on Belgian hospital data. ESMO Real World Data and Digital Oncology, 2025;7,100111.

- Zheng, Y.; Liu,Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Yang, G. The Cardiotoxicity Risk of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Compared with Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2025 Mar 7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40053271. [CrossRef]

- Poels, K.; van Leent, M.M.T.; Reiche, M.E.; Kusters, P.J.H.; Huveneers, S.; de Winther, M.P.J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Lutgens, E.; Seijkens, T.T.P. Antibody-Mediated Inhibition of CTLA4 Aggravates Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation and Progression in Hyperlipidemic Mice. Cells. 2020 Aug 29;9(9):1987. PMID: 32872393; PMCID: PMC7565685. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, L.; Mahmoud, M.A.A.; Weaver, J.D.; Tijaro-Ovalle, N.M.; Christofides, A.; Wang, Q.; Pal, R.; Yuan, M.; Asara, J.; Patsoukis, N.; et al. Targeted deletion of PD-1 in myeloid cells induces antitumor immunity. Sci Immunol. 2020 Jan 3;5(43):eaay1863. PMID: 31901074; PMCID:PMC7183328. [CrossRef]

- Gotsman, I.; Grabie, N.; Dacosta, R.; Sukhova, G.; Sharpe, A.; Lichtman, A.H. Proatherogenic immune responses are regulated by the PD-1/PD-L pathway in mice. J Clin Invest 2007;117:2974–82.

- Roy, P.; Orecchioni, M.; Ley, K. How the immune system shapes atherosclerosis: roles of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022 Apr;22(4):251-265. Epub 2021 Aug 13. PMID: 34389841; PMCID: PMC10111155. [CrossRef]

- Poels, K.; van Leent, M.M.T.; Boutros, C.; Tissot, H.; Roy, S.; Meerwaldt, A.E.; Toner, Y.C.A.; Reiche, M.E.; Kusters, P.J.H.; Malinova, T.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Aggravates T Cell-Driven Plaque Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. JACC CardioOncol. 2020 Oct 6;2(4):599-610. PMID: 34396271; PMCID: PMC8352210. [CrossRef]

- Drobni, Z.D.; Alvi, R.M.; Taron, J.; Zafar, A.; Murphy, S.P.; Rambarat, P.K.; Mosarla, R.C.; Lee, C.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Raghu, V.K.; et al. Association Between Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors With Cardiovascular Events and Atherosclerotic Plaque. Circulation. 2020 Dec 15;142(24):2299-2311. Epub 2020 Oct 2. PMID: 33003973; PMCID: PMC7736526. [CrossRef]

- Vuong, J.T.; Stein-Merlob, A.F.; Nayeri, A.; Sallam, T.; Neilan, T.G.; Yang, E.H.; Immune Checkpoint Therapies and Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Feb 15;79(6):577-593. PMID: 35144750; PMCID: PMC8983019. [CrossRef]

- Drobni, Z. D.; Gongora, C.; Taron, J.; Suero-Abreu, G. A.; Karady, J.; Gilman, H. K.; Supraja, S.; Nikolaidou, S.; Leeper, N.; Merkely, B.; et al. Impact of immune checkpoint inhibitors on atherosclerosis progression in patients with lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2023 Jul;11(7):e007307. PMID: 37433718; PMCID: PMC10347471. [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.H.; Nie, T.; Yang, M.; Luo, K.; Zheng, C.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: the increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events and progression of coronary artery calcium. BMC Med. 2024 Jan 31;22(1):44. PMID: 38291431; PMCID: PMC10829401. [CrossRef]

- Pasello, G.; Pavan, A.; Attili, I.; Bortolami, A.; Bonanno, L.; Menis, J.; Conte, P.; Guarneri, V. Real world data in the era of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): Increasing evidence and future applications in lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020 Jul;87:102031. Epub 2020 May 16. PMID: 32446182. [CrossRef]

- Spigel, D.R.; McCleod, M.; Jotte, R.M.; Einhorn, L.; Horn, L.; Waterhouse, D.M.; Creelan, B.; Babu, S.; Leighl, N.B.; Chandler, J.C.; et al. Efficacy, and Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptom Burden with Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Including Patients Aged 70 Years or Older or with Poor Performance Status (CheckMate 153). J Thorac Oncol. 2019 Sep;14(9):1628-1639. Epub 2019 May 20. PMID: 31121324. [CrossRef]

- La, J.; Cheng, D.; Brophy, M.T.; Do, N.V.; Lee, J. S.; Tuck, D.; Fillmore, N.R. Real-World Outcomes for Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Veterans Affairs System. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020 Oct;4:918-928. PMID: 33074743; PMCID: PMC7608595. [CrossRef]

- Johns, A.C.; Yang, M.; Wei, L.; Grogan, M.; Patel, S.H.; Li, M.; Husain, M.; Kendra, K.L.; Otterson, G.A.;, Burkart, J.T.; et al. Association of medical comorbidities and cardiovascular disease with toxicity and survival among patients receiving checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023 Jul;72(7):2005-2013. Epub 2023 Feb 4. PMID: 36738310; PMCID: PMC10992740. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lin, J.H.; Pan, S.; Salei, Y.V.; Parsons, S.K. The real-world insights on the use, safety, and outcome of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in underrepresented populations with lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2024;40:100833. Epub 2024 Jul 9. PMID: 39018902. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Drobni, Z.D.; Zafar, A.; Gongora, C.A.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Alvi, R.M.; Taron, J.; Rambarat, P.K.; Schoenfeld, S.; Mosarla, R.C.; et al. Pre-Existing Autoimmune Disease Increases the Risk of Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Events After Immunotherapy. JACC CardioOncol. 2022 Dec 20;4(5):660-669. PMID: 36636443; PMCID: PMC9830202. [CrossRef]

- Teske, A.J.; Moudgil, R.; López-Fernández, T.; Barac, A.; Brown, S.A.; Deswal, A.; Neilan, T.G.; Ganatra, S.; Abdel Qadir, H.; Menon, V.; et al. Global Cardio Oncology Registry (G-COR): Registry Design, Primary Objectives, and Future Perspectives of a Multicenter Global Initiative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2023 Oct;16(10):e009905. Epub 2023 Sep 13. PMID: 37702048; PMCID: PMC10824596. [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, S.; Chehade, R.; Boldt, R. G.; Raphael, J.; Blanchette, P.; Vareki, S.M., & Fernandes, R. Association between immune-related side effects and efficacy and benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 2021;92:102134.

- Maccio, U.; Wicki, A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Beuschlein, F.; Wolleb, S.; Varga, Z.; Moch, H. Frequency and Consequences of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Inflammatory Changes in Different Organs: An Autopsy Study Over 13 -Years. Mod Pathol. 2024 Dec 14;38(4):100683. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39675428. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Horita, N.; Adib, E.; Zhou, S.; Nassar, A.H.; Asad, Z.U.A.; Cortellini, A.; Naqash, A.R. Treatment-related adverse events, including fatal toxicities, in patients with solid tumours receiving neoadjuvant and adjuvant immune checkpoint blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2024 Jan;25(1):62-75. Epub 2023 Nov 25. PMID: 38012893 . [CrossRef]

- Aburaki, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; Chida, K.; Horita, N.; Nagasaka, M. Surgical and safety outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy versus chemotherapy alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024 Dec;131:102833. Epub 2024 Oct 5. PMID: 39369455 . [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Huang, C.; Du, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X.; Lin, S.; Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Cai, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of perioperative sintilimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy for potentially resectable stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer (periSCOPE): an open-label, single-arm, phase II trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Dec 7;79:102997. PMID: 39720604; PMCID: PMC11667015. [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Lee, C.K.; Lewis, C.R.; Boyer, M.; Brown, B.; Schaffer, A.; Pearson, S.A.; Simes, R.J. Generalizability of immune checkpoint inhibitor trials to real-world patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2022 Apr;166:40-48. Epub 2022 Feb 3. PMID: 35152172. [CrossRef]

- Kocher, F.; Fiegl, M.; Mian, M.; Hilbe, W. Cardiovascular Comorbidities and Events in NSCLC: Often Underestimated but Worth Considering. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015 Jul;16(4):305-12. Epub 2014 Dec 30. PMID: 25659438. [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.K.; Munoz-Plaza, C.E.; Hahn, E.E.; Lee, J.S.; Parry, C.; Shen, E. Comorbidity Profiles and Their Effect on Treatment Selection and Survival among Patients with Lung Cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017 Oct;14(10):1571-1580. PMID: 28541748. [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, D.E.; Boyne, D.J.; Ford-Sahibzada, C.; Inskip, J.A.; Smith, C.J.; Sripada, K.; Brenner, D.R.; Cheung, W.Y. Real-World Treatment Patterns, Clinical Outcomes, and Healthcare Resource Utilization in Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2024 Jan 12;31(1):447-461. PMID: 38248115; PMCID: PMC10814046. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.; Cheng, C. Y.; Hernandez-Villafuerte, K.; Schlander, M. (2023). Survival and comorbidities in lung cancer patients: Evidence from administrative claims data in Germany. Oncology Research, 2023;30(4), 173.

- Spigel, D.R.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Gray, J.E.; Vicente, D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Vansteenkiste, J.F.; Garassino, M.C.; Hui, R.; Quantin, X.; Rimner, A.; et al. Five-Year Survival Outcomes From the PACIFIC Trial: Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Apr 20;40(12):1301-1311. Epub 2022 Feb 2. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2022 Jun 10;40(17):1965. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.01023. PMID: 35108059; PMCID: PMC9015199. [CrossRef]

- Leighl NB, Hellmann MD, Hui R, Carcereny E, Felip E, Ahn MJ, Eder JP, Balmanoukian AS, Aggarwal C, Horn L, Patnaik A, Gubens M, Ramalingam SS, Lubiniecki GM, Zhang J, Piperdi B, Garon EB. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-001): 3-year results from an open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Apr;7(4):347-357. Epub 2019 Mar 12. PMID: 30876831. [CrossRef]

- Walls GM, Bergom C, Mitchell JD, Rentschler SL, Hugo GD, Samson PP, Robinson CG. Cardiotoxicity following thoracic radiotherapy for lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2025 Mar;132(4):311-325. Epub 2024 Nov 6. Erratum in: Br J Cancer. 2025 Mar;132(4):401-407. doi: 10.1038/s41416-024-02926-x. PMID: 39506136; PMCID: PMC11833127. [CrossRef]

- Boulet J, Peña J, Hulten EA, Neilan TG, Dragomir A, Freeman C, Lambert C, Hijal T, Nadeau L, Brophy JM, et al. Statin Use and Risk of Vascular Events Among Cancer Patients After Radiotherapy to the Thorax, Head, and Neck. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jul 2;8(13):e005996. Epub 2019 Jun 19. PMID: 31213106; PMCID: PMC6662340. [CrossRef]

- Atkins KM, Bitterman DS, Chaunzwa TL, Williams CL, Rahman R, Kozono DE, Baldini EH, Aerts HJWL, Tamarappoo BK, Hoffmann U, Nohria A, Mak RH. Statin Use, Heart Radiation Dose, and Survival in Locally Advanced Lung Cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021 Sep-Oct;11(5):e459-e467. Epub 2021 Jan 18. PMID: 33476841. [CrossRef]

- Gietema JA, Meinardi MT, Messerschmidt J, Gelevert T, Alt F, Uges DR, Sleijfer DT. Circulating plasma platinum more than 10 years after cisplatin treatment for testicular cancer. Lancet. 2000 Mar 25;355(9209):1075-6. PMID: 10744098. [CrossRef]

- Chan SHY, Fitzpatrick RW, Layton D, Webley S, Salek S. Cancer Therapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Results of the Analysis of the UK DEFINE Database. Cancers (Basel). 2025 Jan 19;17(2):311. PMID: 39858093; PMCID: PMC11763784. [CrossRef]

- Demkow U, Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A. Cardiotoxicity of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013 Jun 1;187(1):64-7. Epub 2013 Mar 30. PMID: 23548823. [CrossRef]

- Alexandre J, Moslehi JJ, Bersell KR, Funck-Brentano C, Roden DM, Salem JE. Anticancer drug-induced cardiac rhythm disorders: Current knowledge and basic underlying mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Sep;189:89-103. Epub 2018 Apr 24. PMID: 29698683. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, He Z, Li M, Weng L, Lin J. Efficacy and safety of metronomic oral vinorelbine and its combination therapy as second- and later-line regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2024 Dec;26(12):3202-3210. Epub 2024 Jun 9. PMID: 38851648. [CrossRef]

- Cui Z, Cheng F, Wang L, Zou F, Pan R, Tian Y, Zhang X, She J, Zhang Y, Yang X. A pharmacovigilance study of etoposide in the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database, what does the real world say? Front Pharmacol. 2023 Oct 26;14:1259908. PMID: 37954852; PMCID: PMC10637489. [CrossRef]

- Cui Z, Cheng F, Wang L, Zou F, Pan R, Tian Y, Zhang X, She J, Zhang Y, Yang X. A pharmacovigilance study of etoposide in the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database, what does the real world say? Front Pharmacol. 2023 Oct 26;14:1259908. PMID: 37954852; PMCID: PMC10637489. [CrossRef]

- Tohidinezhad, F.; Pennetta, F.; van Loon, J.; Dekker, A.; de Ruysscher, D.; Traverso, A. Prediction models for treatment-induced cardiac toxicity in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical and Translational Radiation Oncology, 2022 33, 134-144.

- Liu, S.; Gao, W.; Ning, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, L.; Liu, J. Cardiovascular Toxicity With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 8;13:908173. PMID: 35880172; PMCID: PMC9307961. [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, R.; Shah, C.; Blaes, A.; Bian, J.; Hong, Y.R. Cardiovascular toxicity in patients treated with immunotherapy for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A SEER-medicare study: CVD outcomes with the use of ICI in mNSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2020 Dec;150:172-177. Epub 2020 Nov 3. PMID: 33186859. [CrossRef]

- Sabaté-Ortega, J.; Teixidor-Vilà, E.; Sais, È.; Hernandez-Martínez, A.; Montañés-Ferrer, C.; Coma, N.; Polonio-Alcalá, E.; Pineda, V.; Bosch-Barrera, J. Cardiovascular toxicity induced by immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Oncol. 2025 Feb 24;15:1528950. PMID: 40066100; PMCID: PMC11891047. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zheng, L.; Xu, X.; Jin, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, L. The impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the risk of immune-related pneumonitis in lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2024 Aug 14;24(1):393. PMID: 39143553; PMCID: PMC11323643. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nusair, J.; Obeidat, O.; Masoudi, M.D.; Wright, T.; Al-Momani, Z.; Gebremedhen, A. I.; Alnabahneb, N.; Pacioles, T.; Jamil, M.O. Evaluating the impact of COPD exacerbations on survival outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immunotherapy: A retrospective cohort analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2025, Volume 43, Number 16_suppl. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.N.; Ha, Nguyen, T.H.; Hoang, K.D.; Vo, T.K.; Minh Pham, Q.H.; Chen, Y.C. The prognostic significance of diabetes in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024 Dec;218:111930. Epub 2024 Nov 12. PMID: 39536976. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lee, J.; Hong, Y.S.; Kim, K. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease associated with diabetes among adult cancer survivors: a population-based matched cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023 Jun 1;30(8):670-679. PMID: 36790054. [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, H.; Yamada, T.; Oka, Y. Adiposity and cardiovascular disorders: disturbance of the regulatory system consisting of humoral and neuronal signals. Circ Res. 2007 Jul 6;101(1):27-39. Erratum in: Circ Res. 2007 Sep 14;101(6):e79. PMID: 17615379. [CrossRef]

- Larabee, C.M.; Neely, O.C.; Domingos, A.I. Obesity: a neuroimmunometabolic perspective. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 Jan;16(1):30-43. Epub 2019 Nov 27. PMID: 31776456. [CrossRef]

- Rahal, Z.; El Darzi, R.; Moghaddam, S.J.; Cascone, T.; Kadara, H. Tumour and microenvironment crosstalk in NSCLC progression and response to therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2025 Jul;22(7):463-482. Epub 2025 May 16. PMID: 40379986; PMCID: PMC12227073. [CrossRef]

- Tenuta, M.; Gelibter, A.; Pandozzi, C.; Sirgiovanni, G.; Campolo, F.; Venneri, M.A.; Caponnetto, S.; Cortesi, E.; Marchetti, P.; Isidori, A.M.; Sbardella, E. Impact of Sarcopenia and Inflammation on Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NCSCL) Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): A Prospective Study. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Dec 17;13(24):6355. PMID: 34944975; PMCID: PMC8699333. [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, G.; Heo, R.H.; Wang, M.K.; Meyre, P.B.; Park, L.; Blum, S.; Devereaux, P.J.; Conen, D. Associations of inflammatory biomarkers with morbidity and mortality after noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2024 Oct;97:111540. Epub 2024 Jul 2. PMID: 38959697. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, D.; Li, W. Association of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and clinical outcomes in patients with lung cancer receiving immunotherapy: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020 Jun 3;10(6):e035031. PMID: 32499266; PMCID: PMC7282333. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.M.; Ma, L.X. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine, 2015; 8(3), 3098.

- Liu, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; He, Z. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR): A Strong Predictor of Disease Severity in Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) Stroke Patients. J Inflamm Res. 2025 Jan 7;18:195-202. PMID: 39802522; PMCID: PMC11724665. [CrossRef]

- Afari, M.E.; Bhat, T. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and cardiovascular diseases: an update. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;14(5):573-7. Epub 2016 Mar 4. PMID: 26878164. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, F.H.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, J.X.; Wu, L.; Qin, Y.; Zheng, W.R.; Xing, W.Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Associations between peripheral whole blood cell counts derived indexes and cancer prognosis: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of cohort studies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024 Dec;204:104525. Epub 2024 Oct 5. PMID: 39370059. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ruan, G.T.; Liu, T.; Xie, H.L.; Ge, Y.Z.; Song, M.M.; Deng, L.; Shi HP. The value of CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) as a prognostic biomarker in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2023 Aug 23;31(9):533. PMID: 37610445. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Lin, Y.D.; Yao, Y.Z.; Qi, X.J.; Qian, K.; Lin, L.Z.. Negative association of C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in patients with cancer: results from NHANES 1999-2018. BMC Cancer. 2024 Dec 5;24(1):1499. PMID: 39639229; PMCID: PMC11619214. [CrossRef]

- Vernooij, L.M.; van Klei, W.A.; Moons, K.G.; Takada, T.; van Waes, J.; Damen, J.A.; Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 21;12(12):CD013139. PMID: 34931303; PMCID: PMC8689147. [CrossRef]

- Lamperti, M.; Romero, C.S.; Guarracino, F.; Cammarota, G.; Vetrugno, L.; Tufegdzic, B.; Lozsan, F.; Macias Frias, J.J.; Duma, A.; Bock, M.; et al. Preoperative assessment of adults undergoing elective noncardiac surgery: Updated guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2025 Jan 1;42(1):1-35. Epub 2024 Nov 2. PMID: 39492705. Fine modulo. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Smilowitz, N.R.; de Las Fuentes, L.; Mukherjee, D.; Aggarwal, N.R.; Ahmad, F.S.; Allen, R.B.; Altin, S.E.; Auerbach, A.; et al. Peer Review Committee Members. 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Noncardiac Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024 Nov 5;150(19):e351-e442. Epub 2024 Sep 24. Erratum in: Circulation. 2024 Nov 19;150(21):e466. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001298. PMID: 39316661.2024 Dec;204:104525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104525. Epub 2024 Oct 5. PMID: 39370059. [CrossRef]

- Parashar, Y.; Awwad, A.; Bagchi, S.; Claggett, B.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Ogheneochuko, A.W.; Ballantyne, C.M.; deFilippi, C.A. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Cardiac Troponin I vs T in Community Dwelling Adults: Is Specificity at Risk? Clin Chem. 2025 Mar 27:hvaf023. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40151069. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ibáñez, F. O.; Johnson, T.; Mascalchi, M.; Katzke, V.; Delorme, S.; Kaaks, R. Cardiac troponin I as predictor for cardiac and other mortality in the German randomized lung cancer screening trial (LUSI). Sci Rep. 2024 Mar 26;14(1):7197. PMID: 38531926; PMCID: PMC10965973. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, N.; Samadi, S.; Arasteh, O.; Dashtbayaz, R. J.; Zarei, B.; Mohammadpour, A. H.; Jomehzadeh, V. Cardiac troponins and coronary artery calcium score: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024 Feb 9;24(1):96. PMID: 38336618; PMCID: PMC10854184. [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, J.; Henschke, C.I.; Farooqi, A.; Yip, R.; Yankelevitz, D.F.; Shaham, D.; Miettinen, O.S. Frequency of coronary artery calcification on low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Clin Imaging. 2006 May-Jun;30(3):181-5. PMID: 16632153. [CrossRef]

- Dzaye, O.; Berning, P.; Dardari, Z.A.; Mortensen, M.B.; Marshall, C.H.; Nasir, K.; Budoff, M.J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Whelton, S.P.; Blaha, M.J. Coronary artery calcium is associated with increased risk for lung and colorectal cancer in men and women: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Apr 18;23(5):708-716. PMID: 34086883; PMCID: PMC9016360. [CrossRef]

- Gendarme, S.; Maitre, B.; Hanash, S.; Pairon, J.C.; Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Chouaïd, C. Beyond lung cancer screening, an opportunity for early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular diseases. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Sep 2;8(5):pkae082. PMID: 39270051; PMCID: PMC11472859. [CrossRef]

- Mascalchi, M.; Puliti, D.; Romei, C.; Picozzi, G.; De Liperi, A.; Diciotti, S.; Bartolucci M.; Grazzini, M.; Vannucchi, L.; Falaschi, F.; et al. Moderate-severe coronary calcification predicts long-term cardiovascular death in CT lung cancer screening: The ITALUNG trial. Eur J Radiol. 2021 Dec;145:110040. Epub 2021 Nov 16. PMID: 34814037. [CrossRef]

- Koutroumpakis, E.; Xu, T.; Lopez-Mattei, J.; Pan, T.; Lu, Y.; Irizarry-Caro, J.A.; Mohan, R.; Zhang, X.; Meng, Q.H.; Lin, R.; et al. Coronary artery calcium score on standard of care oncologic CT scans for the prediction of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Dec 2;9:1071701. PMID: 36531700; PMCID: PMC9755726. [CrossRef]

- Osawa, K.; Bessho, A.; Fuke, S.; Moriyama, S.; Mizobuchi, A.; Daido, S.; Tanaka, M.; Yumoto, A.; Saito, H.; Ito, H. Coronary artery calcification scoring system based on the coronary artery calcium data and reporting system (CAC-DRS) predicts major adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause death in patients with potentially curable lung cancer without a history of cardiovascular disease. Heart Vessels. 2020 Nov;35(11):1483-1493. Epub 2020 May 22. PMID: 32444933. [CrossRef]

- Zahergivar, A.; Golagha, M.; Stoddard, G.; Anderson, P.S.; Woods, L.; Newman, A.; Carter, M.R.; Wang, L.; Ibrahim, M.; Chamberlin, J.; et al. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium scoring in patients with non-small cell lung cancer using initial staging computed tomography. BMC Med Imaging. 2024 Dec 27;24(1):350. PMID: 39731094; PMCID: PMC11673365. [CrossRef]

- Hech, H.S.; Cronin, P.; Blaha, M.J.; Budoff, M.J.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Narula, J.; Yankelevitz, D.; Abbara, S. 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: A report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Thorac Imaging. 2017 Sep;32(5):W54-W66. PMID: 28832417. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. J.; Wienke, A.; Surov, A.; CT-Defined Coronary Artery Calcification as a Prognostic Marker for Overall Survival in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Radiol. 2025 Mar;32(3):1306-1312. Epub 2024 Nov 18. PMID: 39562196. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Han, S.; Zhang, P.; Mi, L.; Wang,Y.; Nie, J.; Dai, L.; Hu,W.; Zhang,J.; Chen,X.; et al. . Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myocarditis in patients with lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2025, 685 https://doi-org.asmn-re.idm.oclc.org/10.1186/s12885-025-13997-1).

- Faubry, C.; Faure, M.; Toublanc, A.C.; Veillon, R.; Lemaître, A.I.; Vergnenègre, C.; Cochet, H.; Khan, S.; Raherison, C.; Dos Santos, P.; t al.Prospective Study to Detect Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Associated With Myocarditis Among Patients Treated for Lung Cancer. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Jun 6;9:878211. PMID: 35734278; PMCID: PMC9207328. [CrossRef]

- Takada, K; Takamori, S.; Brunetti, L.; Crucitti, P.; Cortellini, A. Impact of neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors on surgery and perioperative complications in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Clinical Lung Cancer, 2023;24(7), 581-590.

- Udumyan, R.; Montgomery, S.; Fang, F.; Valdimarsdottir, U.; Hardardottir, H.; Ekbom, A.; Smedby, K.E.; Fall, K. Beta-Blocker Use and Lung Cancer Mortality in a Nationwide Cohort Study of Patients with Primary Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020 Jan;29(1):119-126. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31641010. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Yang, W.; Zuo, Y. Beta-blocker and survival in patients with lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021 Feb 16;16(2):e0245773. PMID: 33592015; PMCID: PMC7886135. [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.S.; Guzner, A.; Wainwright, D.A.; Mohindra, N.A.; Chae, Y.K.; Behdad, A.; Villaflor, V.M.; The Impact of Beta Blockers on Survival Outcomes in Patients with Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin Lung Cancer. 2021 Jan;22(1):e57-e62. Epub 2020 Aug 5. PMID: 32900613; PMCID: PMC7785632. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, P.; Li, D.; Hu, R.; Tao, M.; Zhu, S.; Wu, W.; Yang, M.; Qu, X. Novel evidence for the prognostic impact of β-blockers in solid cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022 Dec;113(Pt A):109383. Epub 2022 Oct 28. PMID: 36330916. ). [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, T.; Kaira, K.; Shimizu, K.; Shimizu, A.; Mori, K.; Nagashima, T.; Ohtaki, Y.; Oyama, T.; Mogi, A.; Kuwano, H. Prognostic significance of β2-adrenergic receptor expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2016 Nov 15;8(11):5059-5070. PMID: 27904707; PMCID: PMC5126349.

- Dong, Z.K.; Wang, Y.F.; Li, W.P.; Jin, W.L. Neurobiology of cancer: Adrenergic signaling and drug repurposing. Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Dec;264:108750. Epub 2024 Nov 10. PMID: 39527999. [CrossRef]

- Leshem, Y.; Etan, T.; Dolev, Y.; Nikolaevski-Berlin, A.; Miodovnik, M.; Shamai, S.; Merimsky, O.; Wolf, I.; Havakuk, O.; Tzuberi, M.; et al. The prognostic value of beta-1 blockers in patients with non-small-cell lung carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. Int J Cardiol. 2024 Feb 15;397:131642. Epub 2023 Dec 6. PMID: 38065325 . [CrossRef]

- Bhalraam, U.; Veerni, R.B.; Paddock, S.; Meng, J.; Piepoli, M.; López-Fernández, T.; Tsampasian, V.; Vassiliou, V.S. Impact of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on heart failure outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025 Mar 6:zwaf026. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40044419. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hendryx, M.; Dong, Y. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and non-small cell lung cancer survival. Br J Cancer. 2023 Apr;128(8):1541-1547. Epub 2023 Feb 10. PMID: 36765176; PMCID: PMC10070339. [CrossRef]

- Perelman, M.G.; Brzezinski, R.Y.; Waissengrin, B.; Leshem, Y.; Bainhoren, O.; Rubinstein, T.A.; Perelman, M.; Rozenbaum, Z.; Havakuk, O.; Topilsky, Y.; et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cardiooncology. 2024 Jan 11;10(1):2. PMID: 38212825; PMCID: PMC10782769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Tian, J.; Sui, L.; Chen, X. Concomitant Statins and the Survival of Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2022 Jul 5;2022:3429462. PMID: 35855055; PMCID: PMC9276478. [CrossRef]

- Marrone, M.T.; Reuss, J.E.; Crawford, A.; Neelon, B.; Liu, J.O.; Brahmer, J.R.; Platz, E.A. Statin Use With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Survival in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2025 May;26(3):201-209. Epub 2024 Dec 25. PMID: 39818516; PMCID: PMC12037305. [CrossRef]

- Cantini, L.; Pecci, F.; Hurkmans, D.P.; Belderbos, R.A.; Lanese, A.; Copparoni, C.; Aerts, S.; Cornelissen, R.; Dumoulin, D.W.; Fiordoliva, I.; et al. High-intensity statins are associated with improved clinical activity of PD-1 inhibitors in malignant pleural mesothelioma and advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Feb;144:41-48. Epub 2020 Dec 14. PMID: 33326868 . [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ye, X.; Shen, J. Concomitant Statin Use and Survival in Patients With Cancer on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Meta-Analysis. JCO Oncol Pract. 2025 Jul;21(7):989-1000. Epub 2025 Jan 7. PMID: 39772879 . [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Lei, S. Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists with risk of cancers-evidence from a drug target Mendelian randomization and clinical trials. Int J Surg. 2024 Aug 1;110(8):4688-4694. PMID: 38701500; PMCID: PMC11325911. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Lei, S. Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists with risk of cancers-evidence from a drug target Mendelian randomization and clinical trials. Int J Surg. 2024 Aug 1;110(8):4688-4694. PMID: 38701500; PMCID: PMC11325911. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cali Daylan, A.E.; Chi, K.Y.; Prem Anand, D.; Chang, Y.; Chiang, C.H.; Cheng, H. Association Between GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Incidence of Lung Cancer in Treatment-Naïve Type 2 Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2025 Mar;40(4):973-976. Epub 2024 Oct 4. PMID: 39365528; PMCID: PMC11914447. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, C.H. Differential Risk of Cancer Associated with Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: Analysis of Real-world Databases. Endocr Res. 2022 Feb;47(1):18-25. Epub 2021 Aug 30. PMID: 34459679. [CrossRef]

- Sazgary, L.; Puelacher, C.; Lurati Buse, G.; Glarner, N.; Lampart, A.; Bolliger, D.; Steiner, L.; Gürke, L.; Wolff, T.; Mujagic, E.; et al. BASEL-PMI Investigators. Incidence of major adverse cardiac events following non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021 Jun 30;10(5):550–558. Epub 2020 Oct 14. PMID: 33620378; PMCID: PMC8245139. [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz, N. R.; Gupta, N.; Ramakrishna, H.; Guo, Y.; Berger, J. S.; Bangalore, S. Perioperative Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events Associated With Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2017 Feb 1;2(2):181-187. PMID: 28030663; PMCID: PMC5563847. [CrossRef]

- Strickland, S.S; Quintela, E.M.; Wilson, M.J.; Lee, M.J. Long-term major adverse cardiovascular events following myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery: meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2023 Mar 7;7(2):zrad021. PMID: 37104754; PMCID: PMC10129390. [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Gupta, N.; Guo, Y.; Beckman, J. A.; Bangalore, S.; Berger, J.S. Trends in cardiovascular risk factor and disease prevalence in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2018 Jul;104(14):1180-1186. Epub 2018 Jan 5. PMID: 29305561; PMCID: PMC6102124. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Farrokhyar, F.; Schieman, C.; Shargall, Y.; D'Souza, J.; Camposilvan, I.; Hanna,W.C.; Finley, C.J. Pneumonectomy: the burden of death after discharge and predictors of surgical mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014 Dec;98(6):1976-81; discussion 1981-2. Epub 2014 Oct 3. PMID: 25282164. [CrossRef]

- Benker, M.; Citak, N.; Neuer, T.; Opitz, I.; Inci, I. Impact of preoperative comorbidities on postoperative complication rate and outcome in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022 Mar;70(3):248-256. Epub 2021 Sep 23. PMID: 34554366; PMCID: PMC8881261 . [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, A.; Rocco, G.; Szanto, Z.; Thomas, P.; Falcoz, P.E. Morbidity and mortality of lobectomy or pneumonectomy after neoadjuvant treatment: an analysis from the ESTS database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020 Apr 1;57(4):740-746. PMID: 31638692; PMCID: PMC7825477. [CrossRef]

- Ichinose, J.; Yamamoto, H.; Aokage, K.; Kondo, H.; Sato, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Chida, M. Real-world perioperative outcomes of segmentectomy versus lobectomy for early-stage lung cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022 Dec 2;63(1):ezac529. PMID: 36321968. [CrossRef]

- Shelley, B.; Glass, A.; Keast, T.; McErlane, J.; Hughes, C.; Lafferty, B.; Marczin, N.; McCall, P. Perioperative cardiovascular pathophysiology in patients undergoing lung resection surgery: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2023 Jan;130(1):e66-e79. Epub 2022 Aug 13. PMID: 35973839; PMCID: PMC9875905. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Chahil, V.; Battisha, A.; Haq, S.; Kalra, D.K. Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation: A Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1968. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Hida, Y.; Kaga, K.; Iimura, Y.; Shiina, N.; Ohtaka, K.; Muto, J.; Kubota, S.; Matsui, Y. Left lobectomy might be a risk factor for atrial fibrillation following pulmonary lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014 Feb;45(2):247-50. Epub 2013 Aug 6. PMID: 23921159. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, D.; Yamamoto, H.; Endo, S.; Fukuchi, E.; Miyata, H.; Fukuda, I.; Ogino, H.; Sawa, Y.; Chida, M.; Minakawa, M. Postoperative cerebral infarction and arrhythmia after pulmonary lobectomy in Japan: a retrospective analysis of 77,060 cases in a national clinical database. Surg Today. 2023 Dec;53(12):1388-1395. Epub 2023 May 5. PMID: 37147511. [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.C.; Gu, L.; Wang, X..; Wigle, D.A.; Phillips, J.D.; Harpole D.H.; Klapper, J.A., Sporn, T., Ready, N.E.; D'Amico, T.A. Perioperative outcomes of pulmonary resection after neoadjuvant pembrolizumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022 Feb;163(2):427-436. Epub 2021 Apr 9. PMID: 33985811. [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, N.; Okawara, M.; Mori, M.; Fujino, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Fushimi, K.; Tanaka, F. Postoperative cerebral infarction risk is related to lobectomy site in lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study of nationwide data in Japan. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022 Jul;9(1):e001327. PMID: 35868837; PMCID: PMC9316032. [CrossRef]

- Frendl, G.; Sodickson, A.C.; Chung, M.K.; Waldo, A.L.; Gersh, B.J.; Tisdale, J.E.; Calkins, H.; Aranki, S.; Kaneko, T.; Cassivi, S.; et al. American Association for Thoracic Surgery. 2014 AATS guidelines for the prevention and management of perioperative atrial fibrillation and flutter for thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Sep;148(3):e153-93. Epub 2014 Jun 30. PMID: 25129609; PMCID: PMC4454633. [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Di Franco, A.; Rong, L.Q.; Piccini, J.; Mack, M. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: From mechanisms to treatment. Eur.Heart J. 2023, 44, 1020–1039.

- Proietti, M.; Romiti, G.F.; Raparelli, V.; Diemberger, I.; Boriani, G.; Dalla Vecchia, L.A.; Bellelli, G.; Marzetti, E.; Lip, G.Y.; Cesari, M. Frailty prevalence and impact on outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 1,187,000 patients. Ageing Res Rev. 2022 Aug;79:101652. Epub 2022 May 31. PMID: 35659945. [CrossRef]

- Amar, D.; Zhang, H.; Tan, K.S.; Piening, D.; Rusch, V.W.; Jones, D.R. A brain natriuretic peptide-based prediction model for atrial fibrillation after thoracic surgery: Development and internal validation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Jun;157(6):2493-2499.e1. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30826103; PMCID: PMC6626556. [CrossRef]

- Toufektzian, L.; Zisis, C.; Balaka, C.; Roussakis, A. (2015). Effectiveness of brain natriuretic peptide in predicting postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing non-cardiac thoracic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015 May;20(5):654-7. Epub 2015 Jan 28. PMID: 25630332 . [CrossRef]