Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

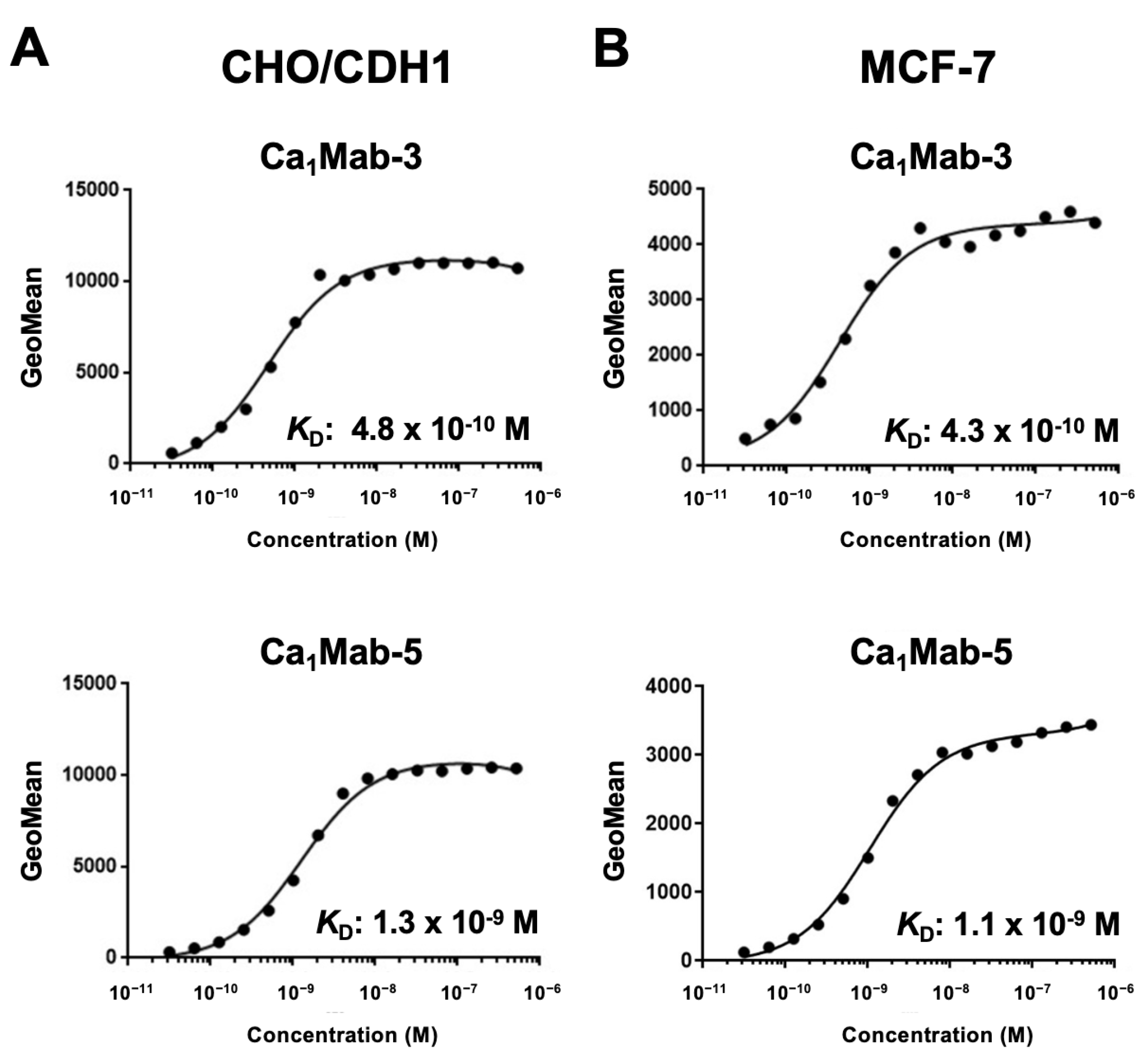

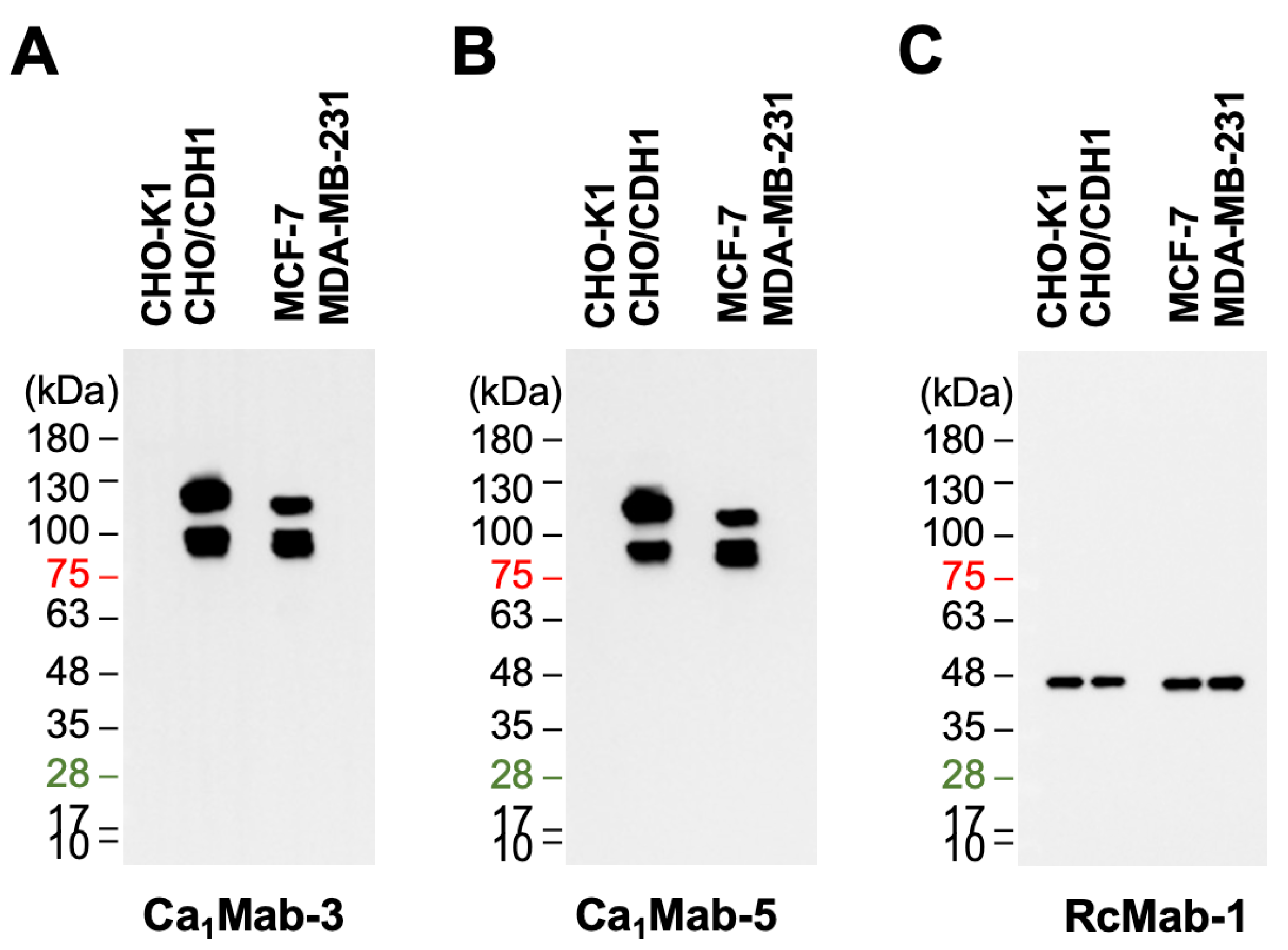

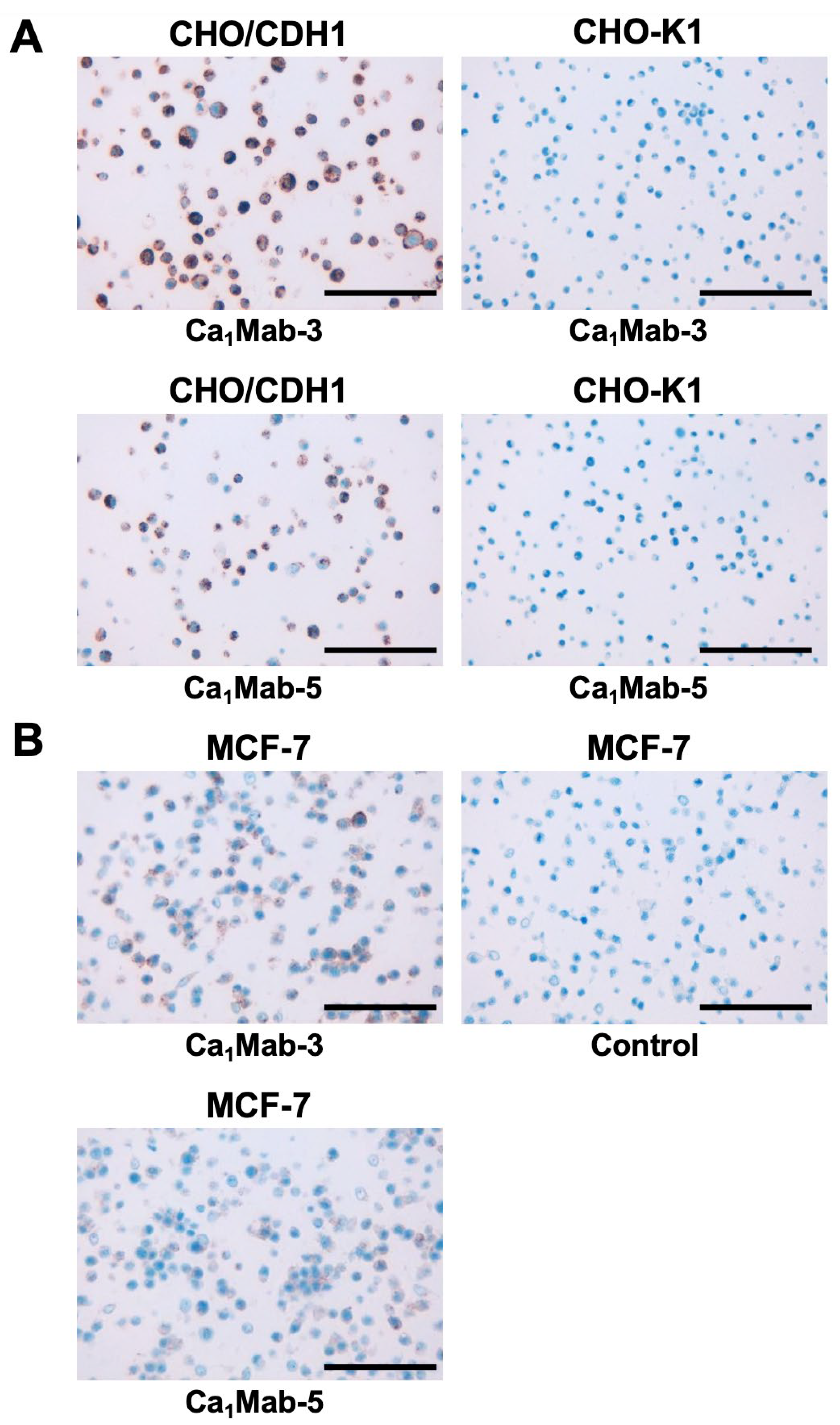

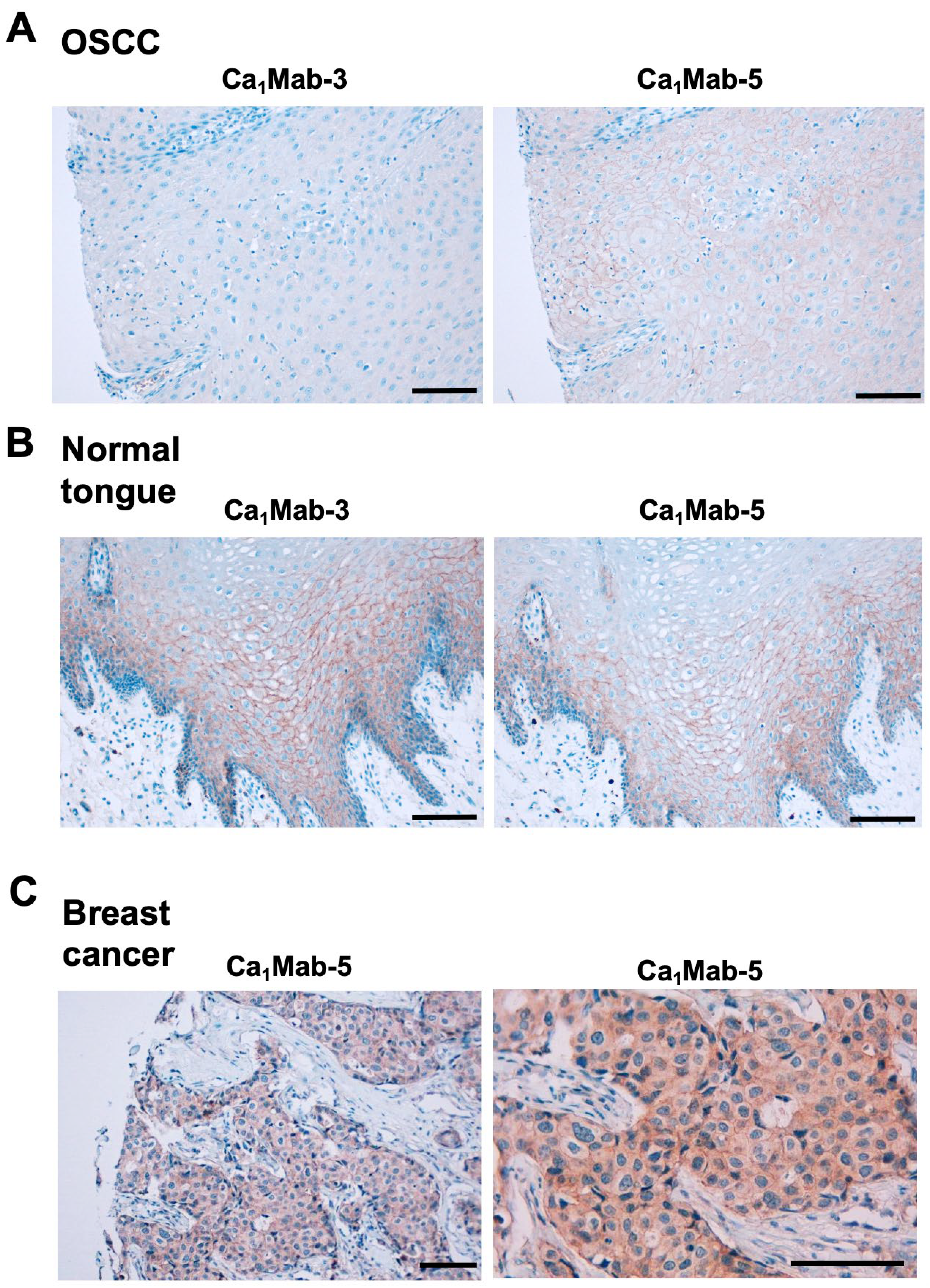

Cadherin (CDH)-mediated extracellular homophilic binding is crucial for maintaining tissue homeostasis. The epithelial cell-cell adhesion molecule cadherin 1 (CDH1/E-cadherin) forms the adherens junctions in epithelial cells, and the loss of CDH1 facilitates the migration and invasion of carcinoma cells. Although several anti-CDH1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are available for western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC), a highly sensitive anti-CDH1 mAb suitable for flow cytometry has not been developed. We developed anti-CDH1 monoclonal antibodies through a flow cytometry-based high-throughput screening. Two anti-CDH1 mAb clones, Ca1Mab-3 (IgG1, κ) and Ca1Mab-5 (IgG1, κ), reacted with human CDH1-overexpressed Chinese hamster ovary-K1 (CHO/CDH1) cells in flow cytometry. Furthermore, Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 recognize endogenous CDH1-expressing human luminal-type breast cancer cells, such as MCF-7, but not triple-negative breast cancer cells, like MDA-MB-231. The dissociation constant values of Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 for CHO/CDH1 were determined as 4.8 × 10−10 M and 1.3 × 10−9 M, respectively. Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 can detect endogenous CDH1 in western blotting and IHC using a cell block. Furthermore, Ca1Mab-5 is available for IHC in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissues. These results indicate that Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5, established by the CBIS method, are versatile for basic research and are expected to contribute to clinical applications, such as tumor diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Establishment of Stable Transfectants

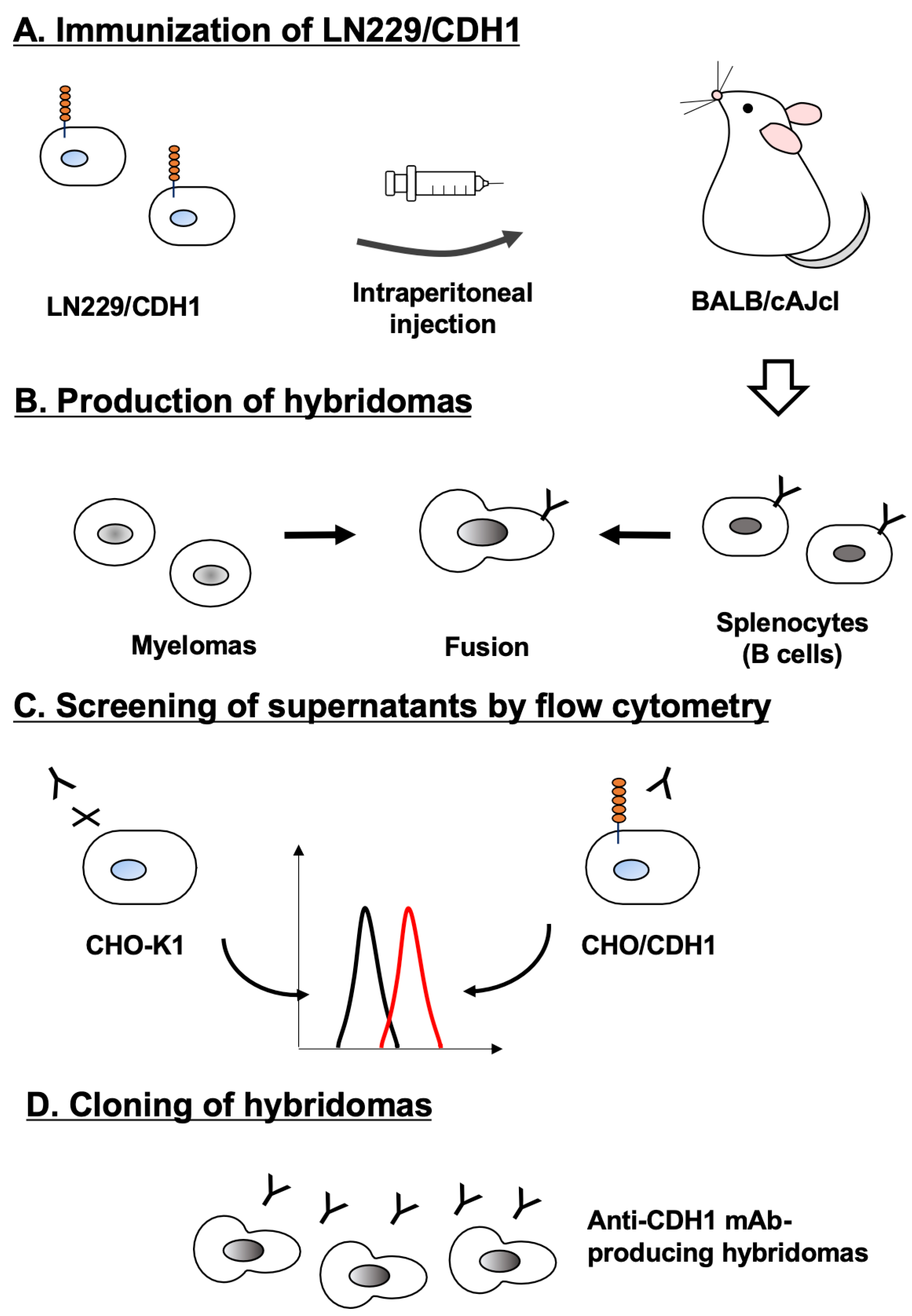

2.3. Development of Hybridomas

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant Values Using Flow Cytometry

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Using Cell Blocks

2.8. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Using FFPE Tissues

3. Results

3.1. Development of Anti-CDH1 mAbs

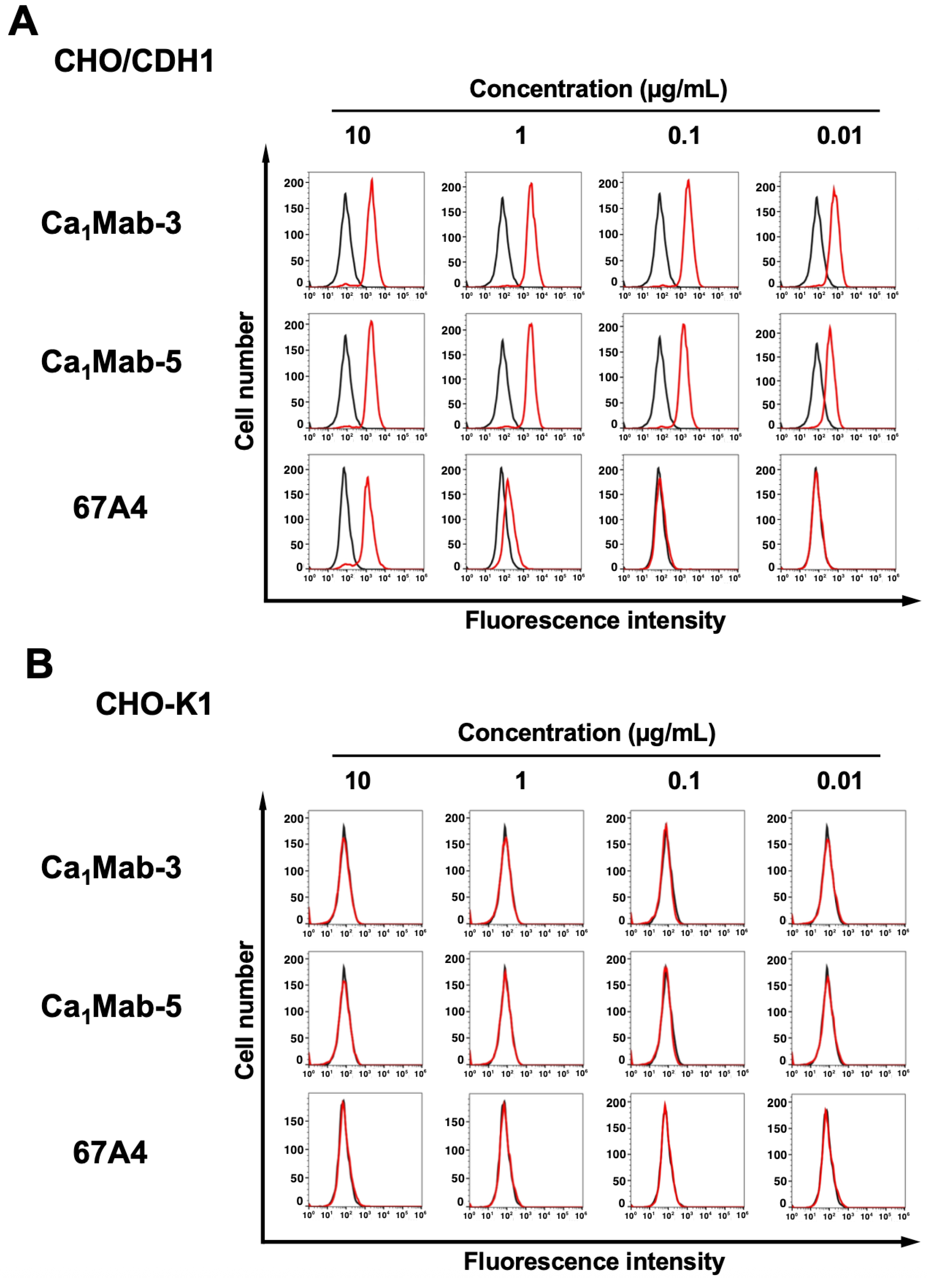

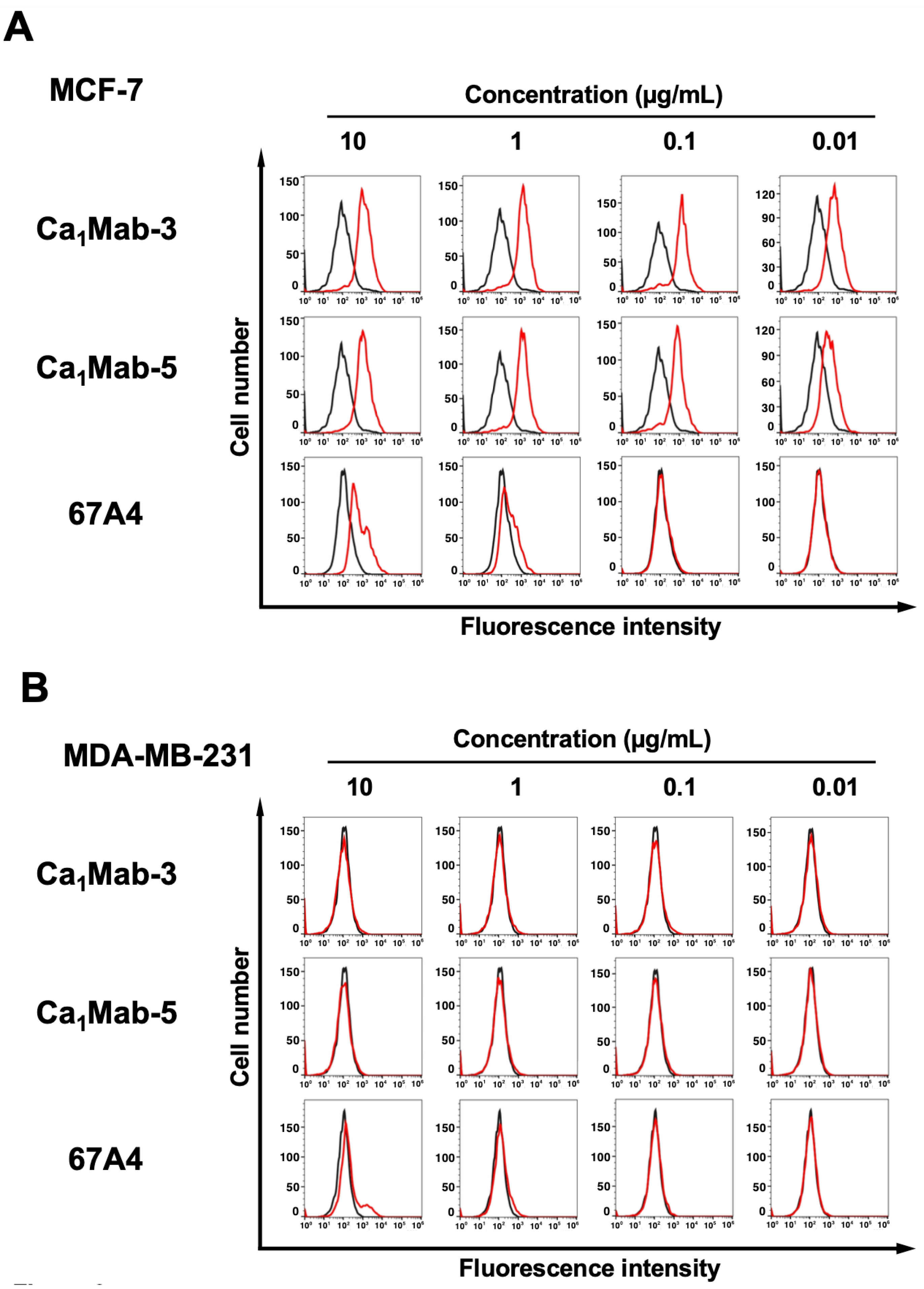

3.2. Flow Cytometry Using Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5

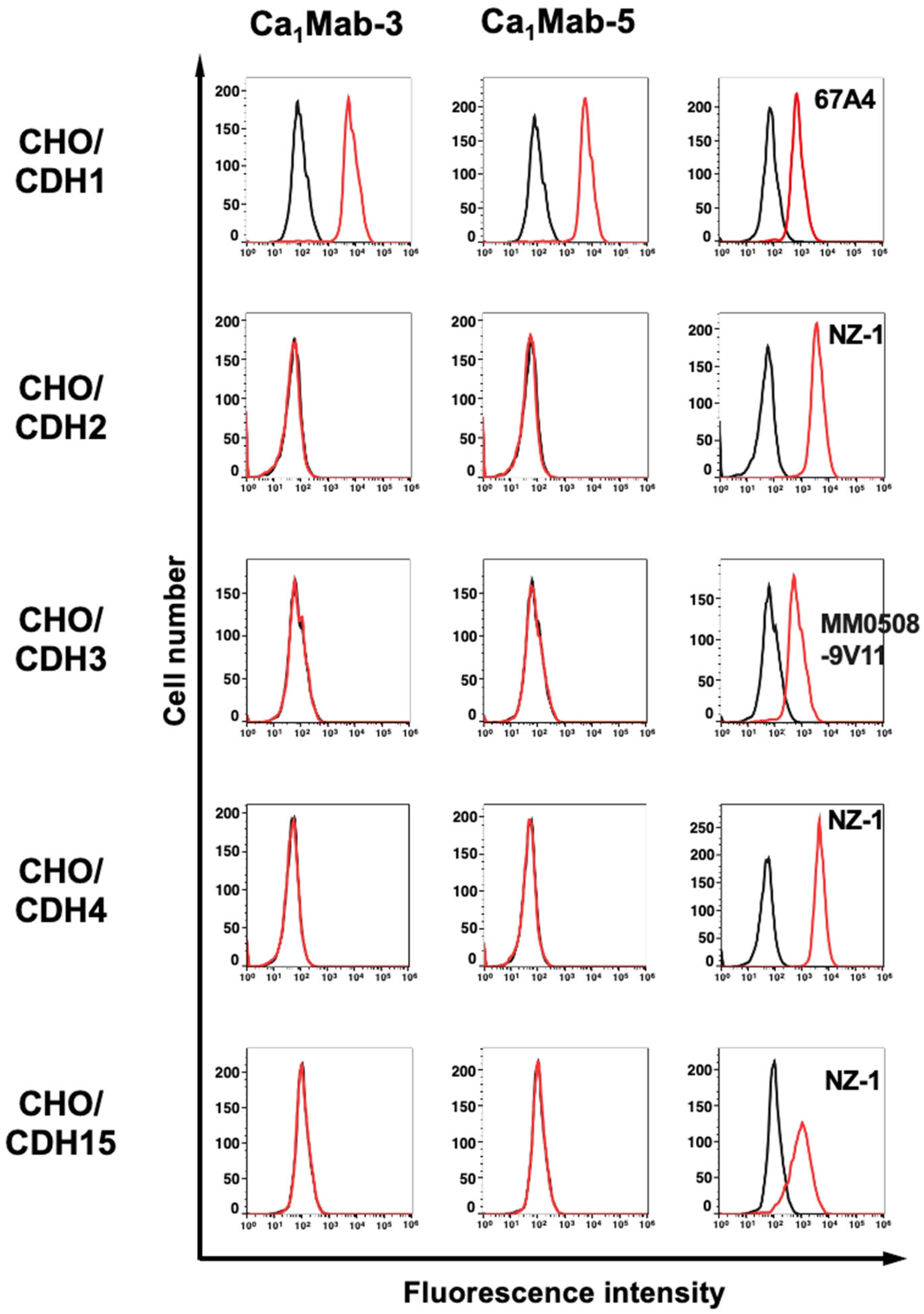

3.3. Specificity of Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 to Type I CDHs-Overexpressed CHO-K1

3.4. Determination of KD Values of Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 by Flow Cytometry

3.5. Western Blot Analysis Using Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5

3.6. IHC using Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Cell Blocks

3.7. IHC Using Ca1Mab-3 and Ca1Mab-5 in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Funding Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niessen, C.M.; Leckband, D.; Yap, A.S. Tissue organization by cadherin adhesion molecules: dynamic molecular and cellular mechanisms of morphogenetic regulation. Physiol Rev 2011;91(2): 691-731. [CrossRef]

- Nollet, F.; Kools, P.; van Roy, F. Phylogenetic analysis of the cadherin superfamily allows identification of six major subfamilies besides several solitary members11Edited by M. Yaniv. Journal of Molecular Biology 2000;299(3): 551-572.

- Oda, H.; Takeichi, M. Evolution: structural and functional diversity of cadherin at the adherens junction. J Cell Biol 2011;193(7): 1137-1146. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Cooper, L.M.; Anastasiadis, P.Z. Cadherins and catenins in cancer: connecting cancer pathways and tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023;11: 1137013. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Cadherin Signaling in Cancer: Its Functions and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Front Oncol 2019;9: 989. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.A.; Huang, R.Y.; Jackson, R.A.; Thiery, J.P. EMT: 2016. Cell 2016;166(1): 21-45.

- Lambert, A.W.; Weinberg, R.A. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2021;21(5): 325-338. [CrossRef]

- Valastyan, S.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 2011;147(2): 275-292. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Antin, P.; Berx, G.; et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020;21(6): 341-352. [CrossRef]

- Ogou, S.I.; Yoshida-Noro, C.; Takeichi, M. Calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion molecules common to hepatocytes and teratocarcinoma stem cells. J Cell Biol 1983;97(3): 944-948. [CrossRef]

- Vestweber, D.; Kemler, R. Identification of a putative cell adhesion domain of uvomorulin. Embo j 1985;4(13a): 3393-3398. [CrossRef]

- Brouxhon, S.M.; Kyrkanides, S.; Teng, X.; et al. Monoclonal antibody against the ectodomain of E-cadherin (DECMA-1) suppresses breast carcinogenesis: involvement of the HER/PI3K/Akt/mTOR and IAP pathways. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(12): 3234-3246. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.L.; Tang, P.; Hicks, D.G.; et al. A new rabbit monoclonal E-cadherin antibody [EP700Y] shows higher sensitivity than mouse monoclonal E-cadherin [HECD-1] antibody in breast ductal carcinomas and does not stain breast lobular carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2014;22(8): 606-612. [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-CDH15/M-cadherin monoclonal antibody Ca(15)Mab-1 for flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025;43: 102138. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; et al. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CCR5 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(4): 96-100. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a Novel Cancer-Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody H(2)Mab-250/H(2)CasMab-2 for Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(2): 35-43.

- Itai, S.; Yamada, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. Establishment of EMab-134, a Sensitive and Specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody for Detecting Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells of the Oral Cavity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017;36(6): 272-281. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014;95: 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Nanamiya, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an Anti-EphB4 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications Against Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2023;42(5): 166-177. [CrossRef]

- Fukagawa, A.; Ishii, H.; Miyazawa, K.; Saitoh, M. δEF1 associates with DNMT1 and maintains DNA methylation of the E-cadherin promoter in breast cancer cells. Cancer Med 2015;4(1): 125-135. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.; Weis, W.I. Structure and biochemistry of cadherins and catenins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009;1(3): a003053. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wei, S.; Lv, X. Circulating tumor cells: from new biological insights to clinical practice. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9(1): 226w biological insights to clinical practice. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D. Circulating tumor cell isolation for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. EBioMedicine 2022;83: 104237ncer diagnosis and prognosis. [CrossRef]

- Gires, O.; Pan, M.; Schinke, H.; Canis, M.; Baeuerle, P.A. Expression and function of epithelial cell adhesion molecule EpCAM: where are we after 40 years? Cancer Metastasis Rev 2020;39(3): 969-987. [CrossRef]

- Gorin, M.A.; Verdone, J.E.; van der Toom, E.; et al. Circulating tumour cells as biomarkers of prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2017;14(2): 90-97. [CrossRef]

- Criscitiello, C.; Sotiriou, C.; Ignatiadis, M. Circulating tumor cells and emerging blood biomarkers in breast cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2010;22(6): 552-558. [CrossRef]

- Marcuello, M.; Vymetalkova, V.; Neves, R.P.L.; et al. Circulating biomarkers for early detection and clinical management of colorectal cancer. Mol Aspects Med 2019;69: 107-122. [CrossRef]

- Varillas, J.I.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; et al. Microfluidic Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells and Cancer Stem-Like Cells from Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Theranostics 2019;9(5): 1417-1425. [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; et al. In Vivo Coinstantaneous Identification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Circulating Tumor Cells by Dual-Targeting Magnetic-Fluorescent Nanobeads. Nano Lett 2021;21(1): 634-641. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Ling, S.; Zheng, S.; Xu, X. Liquid biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma: circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Mol Cancer 2019;18(1): 114. [CrossRef]

- Gall, T.M.H.; Belete, S.; Khanderia, E.; Frampton, A.E.; Jiao, L.R. Circulating Tumor Cells and Cell-Free DNA in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol 2019;189(1): 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wuethrich, A.; Wang, J.; et al. Dynamic Monitoring of EMT in CTCs as an Indicator of Cancer Metastasis. Anal Chem 2021;93(50): 16787-16795. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, E.; Taftaf, R.; Reduzzi, C.; et al. Better together: circulating tumor cell clustering in metastatic cancer. Trends Cancer 2021;7(11): 1020-1032. [CrossRef]

- Hapach, L.A.; Carey, S.P.; Schwager, S.C.; et al. Phenotypic Heterogeneity and Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res 2021;81(13): 3649-3663. [CrossRef]

- van Roy, F. Beyond E-cadherin: roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14(2): 121-134.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144(5): 646-674.

- Lüönd, F.; Sugiyama, N.; Bill, R.; et al. Distinct contributions of partial and full EMT to breast cancer malignancy. Dev Cell 2021;56(23): 3203-3221.e3211. [CrossRef]

- Hollestelle, A.; Peeters, J.K.; Smid, M.; et al. Loss of E-cadherin is not a necessity for epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;138(1): 47-57. [CrossRef]

- Horne, H.N.; Oh, H.; Sherman, M.E.; et al. E-cadherin breast tumor expression, risk factors and survival: Pooled analysis of 5,933 cases from 12 studies in the Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Sci Rep 2018;8(1): 6574. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.J.; Lewis-Tuffin, L.J.; Anastasiadis, P.Z. E-cadherin’s dark side: possible role in tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1826(1): 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.J.; Ewald, A.J. A collective route to metastasis: Seeding by tumor cell clusters. Science 2016;352(6282): 167-169. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.J.; Gabrielson, E.; Werb, Z.; Ewald, A.J. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell 2013;155(7): 1639-1651. [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, V.; Krol, I.; Suhail, Y.; et al. E-cadherin is required for metastasis in multiple models of breast cancer. Nature 2019;573(7774): 439-444. [CrossRef]

- Na, T.Y.; Schecterson, L.; Mendonsa, A.M.; Gumbiner, B.M. The functional activity of E-cadherin controls tumor cell metastasis at multiple steps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(11): 5931-5937. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Cancer-Specific Anti-Podoplanin Monoclonal Antibody, PMab-117-mG(2a) Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Tumor Xenograft Models. Cells 2024;13(22). [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(3). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).