Introduction

Immunisation is one of the greatest achievements of modern medicine, preventing an estimated 4–6 million deaths worldwide each year (1). In Croatia, vaccination is free and legally mandated against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, measles, mumps, rubella, tuberculosis, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and pneumococcal disease (2,3). Despite its proven effectiveness and availability, parental hesitancy persists. Concerns about side effects, doubts regarding efficacy, and distrust in institutions reduce vaccine coverage, weaken herd immunity, and contribute to the re-emergence of preventable diseases (4). The aim of this study was to examine the knowledge and attitudes of parents of preschool-aged children towards vaccination and to identify factors influencing their decisions. The findings may inform targeted educational strategies and strengthen public health efforts to sustain high immunisation coverage.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

A sample of 320 parents of children aged 0 to 6 years, born between 2018 and 2024, took part in the study. All parents who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study and gave their informed consent at the time of arrival at the study were included. The inclusion criteria were: Parenthood of the child up to the age of six, regular attendance at one of the named paediatric clinics, and access to and ability to complete online questionnaires. The study was conducted anonymously so that basic ethical standards for the protection of personal data and privacy were adhered to.

Methods

A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted based on the use of a structured anonymous questionnaire. The aim of the study was to investigate the attitudes of parents of pre-school children towards vaccination, focussing on the level of information, sources of information and attitudes towards compulsory vaccination. The study lasted three months, and was conducted as part of regular systematic examinations and check-ups in two paediatric outpatient clinics of the Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, Health Centre in Pehlin. A structured questionnaire created in Google Forms was used for the study, based on a validated instrument by Kulić I., Čivljak M. and Čivljak R., which was developed as part of the study Parents’ attitudes towards vaccination of their own children: experiences from two paediatric outpatient clinics of the Zagreb Health Centre – West (4). The questionnaire contained 26 closed questions and was divided into two main parts. The first part contained demographic and socioeconomic data: Gender, age, marital status, education level, employment, number of children and monthly household income. The second part contained seven statements about parents’ attitudes towards vaccination, including opinions on compulsory vaccination, previous experience and the type of information provided. The answers were recorded on a Likert-scale from 1 to 5, where 1 stands for “strongly disagree” and 5 for “strongly agree”. The questionnaire took about 5 minutes to complete.

The data was collected using leaflets that were displayed in the waiting rooms of paediatric clinics. The leaflets contained a brief description of the purpose of the survey, instructions for participation and a QR code to access the digital questionnaire. Parents could complete the questionnaire immediately on their smartphone or take it home and complete it at their leisure. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the purpose of the survey, the voluntary nature of participation, the option to withdraw at any time, and the guarantee of anonymity and confidentiality of the data were clearly indicated.

Statistical Data Processing

The statistical processing of the data collected was carried out using the Statistics programme. The parents’ gender variable was analysed using the nominal scale, while the parents’ age variable was treated as a proportional variable, which was presented using the arithmetic mean and the standard deviation. Parents’ attitudes towards vaccination, and the sources of information, were analysed as ordinal variables. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics, which describe the basic characteristics of the sample. The results are presented in the form of tables and charts using absolute numbers, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion. In this study, the dependent variables were parents’ attitudes towards vaccinating their own children, while the independent variables included age, gender, number of children, sources of information, level of information and satisfaction with vaccination information.

The Spearman correlation coefficient and chi-square test were used to examine the relationship between parental attitudes and these variables. Parametric statistical tests, including t-test and unidirectional analysis of variance (ANOVA), were also applied. Where appropriate, additional post-hoc tests were conducted using Tukey’s test.

The analysis examined whether there were statistically significant differences in parents’ attitudes towards vaccination in relation to their demographic characteristics and the type of information, with statistical significance defined at the p < 0.05 level.

The Ethical Aspect of the Research

The ethical conduct of the research was ensured through the use of an anonymous questionnaire, in which all respondents were previously informed of the objectives and conditions of participation in the research, and gave their consent. The data collected during the study was not misused or utilised for purposes other than scientific research. A low-risk study, ethical approval was not required, but it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

General Data

A total of 320 parents participated in the study, of which 255 (79.7%) were female and 65 (20.3%) male. Of the age groups, 14 (4.4%) were younger than 25 years, 187 (58.4%) were aged 26-36 years, 105 (32.8%) were aged 37-45 years and 14 (4.4%) were older than 45 years. 296 (92.6%) of respondents are married, while 18 respondents (5.6%) are divorced, and 6 of them (1.9%) stated that they are single. One child was reported by 171 (53.4 %), two children by 121 (37.8 %), three children by 21 (6.6 %), and four or more children by 7 (2.2 %) of the respondents.

Other socio-demographic data related to the level of education, employment and monthly income of the family. 161 (50.3%) of the respondents have a university degree, 65 (20.3%) have a university degree, 92 (28.7%) have a high school diploma, and 2 (0.6%) have a primary school diploma or lower. 292 (91.3%) of respondents were employed, 26 (8.1%) were unemployed, and 2 respondents (0.6%) were still in education. 50 (15.6 %) of respondents had a monthly family income of more than €4000, 175 (54.4 %) respondents had a monthly family income of more than €4000, 89 (27.8 %) respondents had an income of €1000-2000, and 7 (2.2 %) respondents had an income of less than €1000.

Attitude Towards Vaccination

The majority of parents (85.9%) stated that they have their children vaccinated regularly, and will continue to do so. Some parents (8.8%) stated that they had concerns about vaccinating their children and did not have a clear stance on mandatory vaccination, while 5.3% were against mandatory vaccination. 225 (70.3) of respondents believe that immunisation is the best way to prevent potentially fatal infectious diseases and protect children. , 56 (17.5%) of respondents believe that every parent should decide for themselves whether they want their child to be vaccinated and what is best for them, while 39 (12.2%) of respondents do not know what they think about this. If parents had the right to choose and the option to refuse vaccinations, 164 (51.2%) respondents would continue to have their child vaccinated, 112 (35%) would only have their child vaccinated with certain vaccines, 17 (5.3%) respondents would not have their child vaccinated, while 27 (8.4%) are not sure what they would do in such a situation. The most common reason given for refusing vaccinations by 189 of them (59.1%) was fear of the side effects of vaccination. 6 (1.9%) respondents believe that vaccination is not necessary, while 31 (9.7%) respondents stated that no vaccine is 100% effective in preventing infectious diseases. On the other hand, 94 (29.4%) parents would not refuse to have their child vaccinated, expressing their confidence in vaccination despite the possibility of choice. Most of the respondents, 286 (89.4 %), stated that they received most of their information about immunisation from their doctor, 193 (60.3 %) parents used the Internet as the second most important source of information, and 179 (55.9 %) received information from a nurse. 145 of them (45.3 %) consult with family and friends about vaccination, and 57 (17.8 %) obtain information from brochures, television and magazines. Regarding respondents’ satisfaction with the vaccination information they received from the doctor and nurse in charge, the majority of respondents, 231 (72%), stated that they received all the necessary information and answers to their questions and uncertainties, indicating a high level of satisfaction with communication with healthcare professionals. 60 respondents (19%) stated that communication was very sparse, that they received little information and that they had a general impression of disinterest. The remaining 29 respondents (9%) point out that they are only informed about basic things, and that health professionals do not know how to answer some of their questions. 197 (61.6%) parents are familiar with the anti-vaccination movement, while 123 (38.4%) are not. When asked what they think of the movement, 139 (43.4%) responded that they do not support it, 60 (18.8%) partially agree, and 24 (7.5%) support it. When asked who benefits most from vaccination, 167 (52.2%) responded: the community, family and children, 86 (26.9%): the children, and 65 (20.3%): parents pharmaceutical companies that produce vaccines. Most participants, 106 (33.1%), believe that they are well informed, while 95 respondents (29.7%) say they are sufficiently informed. At the same time, 66 respondents (20.6%) rated their level of information as very good. On the other hand, 36 respondents (11.3%) believe that they are insufficiently informed, and 17 (5.3%) state that they are unable to assess their level of information.

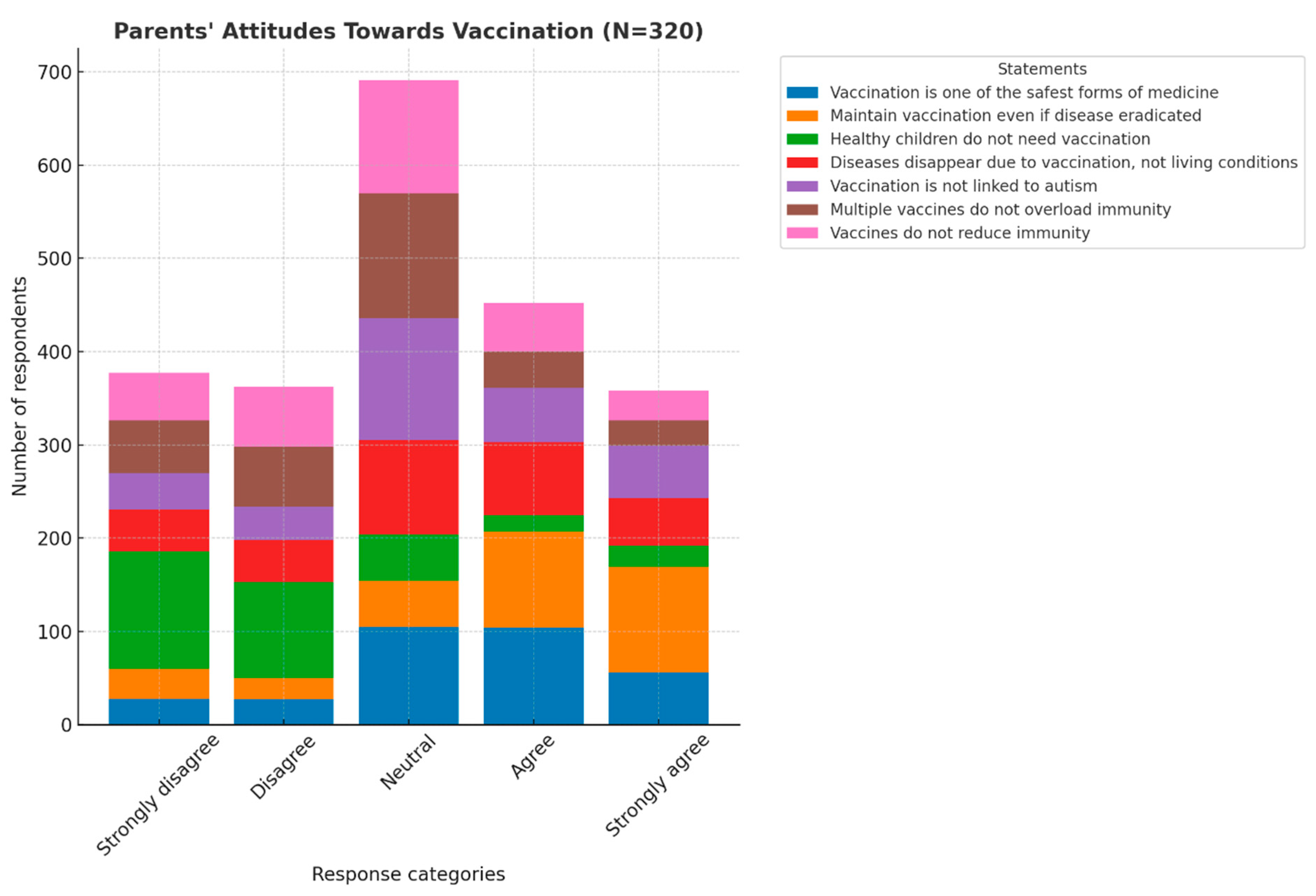

Table 1 and

Figure 1 shows parents’ attitudes towards vaccination, rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. Most parents agreed with the statement that it is important to maintain a high level of vaccination even if the disease is eradicated, with an average of 3.76 (SD=1.28), with 67.5% agreeing or strongly agreeing. In addition, half of the respondents believe that vaccination is one of the safest forms of medicine, which is confirmed by an average score of 3.42 (SD=1.13).

The majority of respondents disagree with the statement that healthy children do not need to be immunised, an average of 2.09 (SD=1.19) and 71.6% disagree or strongly disagree, which shows a good awareness of the importance of immunisation. The attitude towards the assertion that infectious diseases disappear due to vaccinations and not due to better living conditions, is moderate, with an average of 3.14 (SD=1.25).

The question about the connection between vaccination and autism triggers uncertainty – 40.9% of respondents are neutral, and the average value is 3.18 (SD = 1.20). The situation is similar with claims about the simultaneous administration of several vaccines and a decrease in immunity, where there is a large number of neutral responses, and the average is 2.74 (SD = 1.14). Similarly, the view that the vaccine does not cause a decrease in immunity has a mean score of 2.84 (SD = 1.17), indicating indecision and lack of information in these areas.

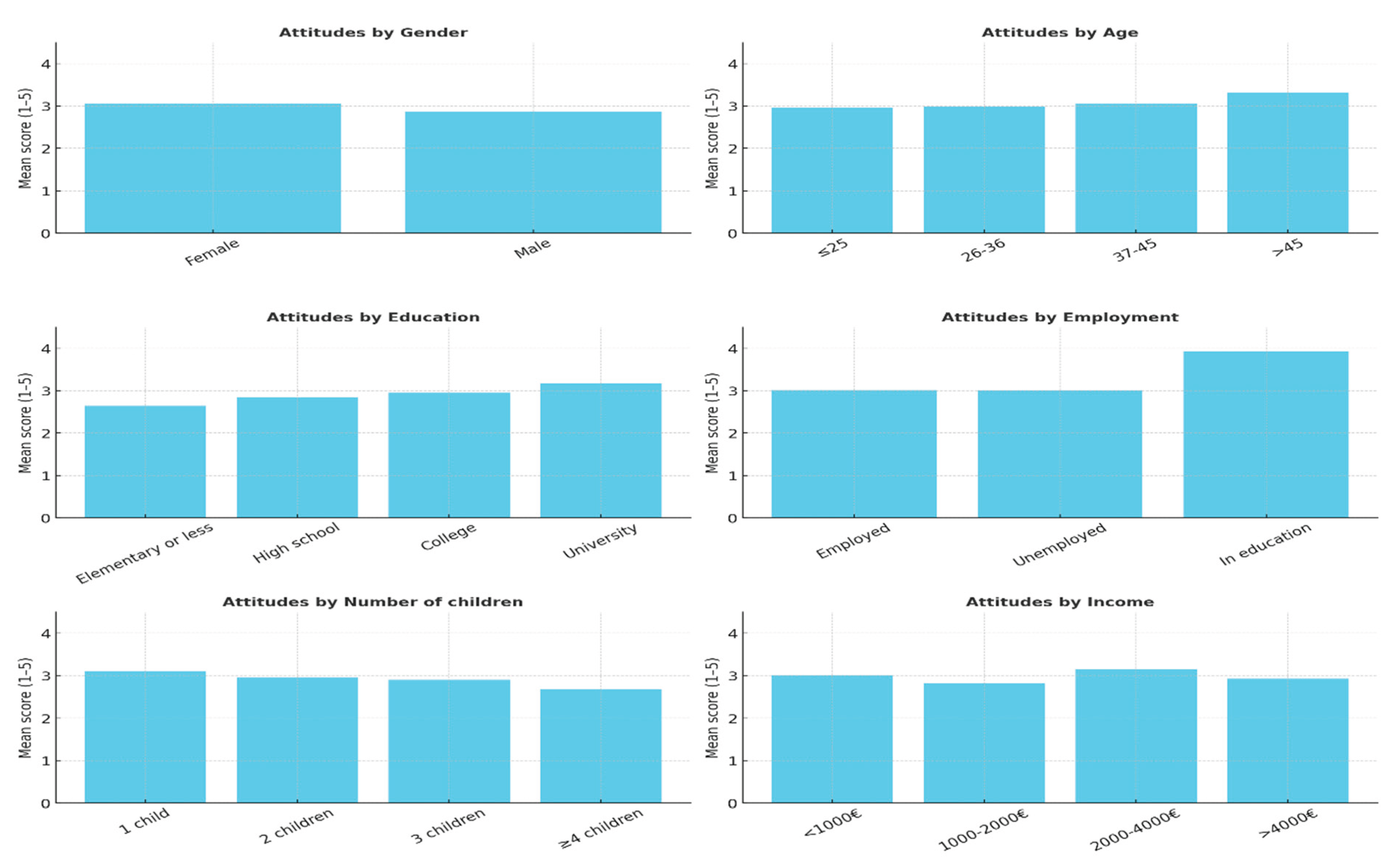

Table 2 and

Figure 2 shows the differences in parents’ attitudes towards vaccinating their children (Likert scale score) according to socio-demographic characteristics. Analysing the sociodemographic data of the respondents (N = 320) to the survey on parents’ attitudes and knowledge regarding vaccination of preschool children revealed that the majority of the sample were women (79.7%), with an average Likert scale score of 3.06, with no statistically significant difference compared to men (P = 0.46). The age of the participants did not have a major influence on the results, although those over 45 years of age showed a slightly higher level of agreement (M = 3.32; p = 0.05). In terms of education, respondents with a university degree agreed more strongly (M = 3.17), while the lowest scores were recorded for those with a high school diploma (M = 2.84), and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Marital status, employment and the number of children in the family did not appear to be significant in relation to the attitudes and knowledge analysed, while higher monthly family income was associated with higher scores, with a statistically significant correlation (p = 0.01).

Discussion

General Overview

Immunisation is one of the most successful public health interventions, preventing an estimated 4–6 million deaths annually (5–9). Despite its proven effectiveness, vaccination has been controversial since the 19th century and remains a topic of public debate. In Croatia, vaccination coverage has declined in certain counties, falling below 90% in some areas and raising concerns about herd immunity (8).

Comparison with Previous Studies

Our results confirm trends observed in Croatia and across Europe (10-15). Previous Croatian studies also showed variability in parents’ knowledge about routine vaccination (13). Fear of adverse effects remains the most common reason for hesitancy: 59% of parents in our study cited side effects as the main concern, compared with 50% in a Zagreb survey ten years earlier (4,15). Similar results on vaccine confidence were observed in Italy, where coverage for herpes zoster remained linked to public trust in healthcare professionals (10). The persistence of autism-related concerns reflects the long-standing impact of Wakefield’s discredited work (14). Concerns about a link to autism persist, with 64% of parents unconvinced of vaccine safety, reflecting the enduring impact of Wakefield’s discredited 1998 study (14,15).

While 85.9% of parents reported vaccinating their children regularly and 80.3% expressed positive views, 5.3% openly opposed vaccination, higher than in earlier Croatian studies where opposition was below 1%. This increase, though modest, signals the influence of misinformation. Similar European studies confirm that socio-demographic factors matter. Higher education and income correlate with more favourable attitudes (16-20). A systematic review confirmed that psychological and social factors strongly shape parents’ decisions on vaccination across Europe (11). Determinants of MMR uptake among European parents have been systematically reviewed, confirming the influence of education and income (18). Our findings also show older parents express slightly more positive views, while gender differences were minimal. The ESCULAPIO project (18) highlighted that lower education and income significantly reduce MMR uptake consistent with our results.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic strongly shaped public perceptions of vaccination. The rapid rollout of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines highlighted the role of immunisation in managing global crises but also fuelled mistrust, extending doubts to routine paediatric vaccines. Although concerns about the speed of development were understandable, safety standards were rigorously maintained and the benefits far outweighed risks (21-23). The rapid development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines has also shaped public perceptions of immunisation more broadly (22). Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices, HALMED, reported 6,613 suspected adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccines in Croatia from 4.7 million administered doses, with only a small number assessed as possibly or probably related (23). This illustrates the rarity of serious adverse events relative to the scale of vaccination.

Public Health Implications

Our study underscores the need for ongoing monitoring of parental attitudes and targeted interventions. Public health strategies should therefore:

strengthen the communication skills of paediatricians, family doctors, and nurses;

increase the visibility of accurate online information on official websites and social networks;

develop tailored campaigns addressing specific parental concerns and fears.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include a relatively large sample and robust statistical analysis. However, as a cross-sectional design, it cannot establish causality. Self-reported data may also introduce bias, and the study was limited to two clinics, which may affect generalisability. Most parents in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County support childhood immunisation, but misinformation and fear of side effects remain significant barriers. The post-pandemic environment has intensified mistrust, requiring stronger professional communication, better use of digital platforms, and comprehensive, science-based campaigns. Investing in the education and empowerment of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, will be critical to sustaining high vaccination coverage and protecting public health.

Conclusion

This study shows that most parents in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County comply with the vaccination calendar and hold positive attitudes toward childhood immunisation. Nevertheless, a considerable proportion express uncertainty, with fear of side effects being the primary concern, rather than doubts about vaccine efficacy. Parental knowledge was generally high, and paediatricians and internet sources were the most frequently cited channels of information. Satisfaction with communication from healthcare professionals was strongly associated with greater confidence in vaccines, while higher education was also linked to more positive attitudes. In contrast, the number of children did not significantly influence parental views, suggesting that personal beliefs and education play a stronger role. Demographic differences were also observed, with mothers and older parents more often reporting positive attitudes.

These findings emphasise the importance of clear, consistent, and empathetic communication by healthcare professionals. Public health campaigns should be better tailored to parents with lower levels of education and to those expressing insecurity about vaccination. Nurses, particularly bachelor’s and master’s graduates in primary care and public health, have a pivotal role in this process. By strengthening their counselling and communication skills, they can significantly contribute to building parental trust, reducing misinformation, and maintaining high vaccination coverage.

Finally, research of this kind is crucial for understanding parental attitudes and needs. Such insights provide the foundation for developing effective educational strategies, enabling more targeted interventions and strengthening the preventive role of the health system in safeguarding public health.

Author Contributions

MŠ and ŽJ Conceptualized the study, interpreted the results and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. SŠ and BM Conceptualized the study and the methodology, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted of the results and revised of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All participants were informed about the study objectives and conditions and provided informed consent before participation. A low-risk study, ethical approval was not required, but it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating parents and the staff of the paediatric outpatient clinics of the Health Centre of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County for their support during the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable (low-risk observational study).

References

- Simić, M. Knowledge and opinions on vaccination among parents of preschool children [master’s thesis]. Osijek: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Medicine Osijek; 2018 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: https://repozitorij.mefos.hr/islandora/object/mefos:366/datastream/PDF/view.

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Implementation program of mandatory vaccination in the Republic of Croatia in 2022 [Internet]. Zagreb: CIPH; 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Provedbeni-program-obveznog-cijepljenja-u-RH-u-2022..pdf.

- Public Health Institute of Dubrovnik-Neretva County. Vaccination [Internet]. Dubrovnik: PHI; [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: https://www.zzjzdnz.hr/hr/usluge/cijepljenje.

- Kulić I, Čivljak M, Čivljak R. Parents’ attitudes toward vaccinating their children – experience from two pediatric practices of the Zagreb-West Health Center. Acta Med Croatica. 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/224693.

- World Health Organization. Vaccination and immunization: key facts [Internet]. WHO; [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/vaccines-and-immunization/know-the-facts.

- Karmel S, Jovanović Ž. Some factors influencing underreporting of suspected adverse vaccine reactions. Paediatr Croat. 2023;67:65-70. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Vaccination coverage [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/procijepljenost/.

- Stefanoff P, Mamelund SE, Robinson M, et al. Tracking parental attitudes on vaccination across European countries: The Vaccine Safety, Attitudes, Training and Communication Project (VACSATC). Vaccine. 2010;28(35):5731-5737. [CrossRef]

- Greyson D, Carpiano RM, Bettinger JA. Support for a vaccination documentation mandate in British Columbia, Canada. Vaccine. 2022 Dec 5;40(51):7415-25. [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35501180/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salussolia A, Capodici A, Scognamiglio F, La Fauci G, Soldà G, Montalti M, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine coverage and confidence in Italy: the OBVIOUS project. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11044443/.

- Achimaș-Cadariu T, Pașca A, Jiboc NM, Puia A, Dumitrașcu DL. Vaccine Hesitancy among European Parents-Psychological and Social Factors Influencing the Decision to Vaccinate against HPV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(2):127. Published 2024 Jan 26. [CrossRef]

- Gács Z, Koltai J. Understanding Parental Attitudes toward Vaccination: Comparative Assessment of a New Tool and Its Trial on a Representative Sample in Hungary. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Dec;10(12):2006. [cited 2025 May 6]. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/10/12/2006. [CrossRef]

- Čuljak, N. Parents’ knowledge and awareness of routine childhood vaccination [master’s thesis]. [cited 2025 May 6]. Available from: https://repozitorij.fdmz.hr/islandora/object/fdmz:615.

- Rao TS, Andrade C. The MMR vaccine and autism: sensation, refutation, retraction, and fraud. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011 [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 9]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3136032/.

- Lindsay, P. The Doctor Who Fooled The World: Andrew Wakefield’s war on vaccines. Br J Gen Pract. 2020 Dec [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 9]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7759370/.

- Szalast K, Nowicki GJ, Pietrzak M, Mastalerz-Migas A, Biesiada A, Grochans E, Ślusarska B. Parental Attitudes, Motivators and Barriers Toward Children’s Vaccination in Poland: A Scoping Review. Vaccines. 2025; 13(1):41. [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, I.A. , Mollema, L., Ruiter, R.A. et al. Why parents refuse childhood vaccination: a qualitative study using online focus groups. BMC Public Health 13, 1183 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi G, Costantino C, Napoli G, et al. Determinants of European parents’ decision on the vaccination of their children against measles, mumps and rubella: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(7):1909-1923. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Pelčić, G. Vaccination and communication [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 6]. Available from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/248504.

- Cjepko Zna. Cjepko zna [Internet]. Rijeka: Faculty of Medicine, University of Rijeka; [cited 2025 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.cjepkozna.com/.

- Figueiredo A, Larson HJ, Reicher SD. The potential impact of vaccine passports on inclination to accept COVID-19 vaccination in the United Kingdom. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101109. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020;586(7830):516-27. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices (HALMED). Report on suspected adverse reaction reports in 2021 [Internet]. Zagreb: HALMED; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.halmed.hr/fdsak3jnFsk1Kfa/ostale_stranice/Izvjesce-o-prijavama-sumnji-na-nuspojave-u-2021.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).