1. Introduction

Invasive fungal respiratory infections (IFRIs) represent a significant clinical challenge, particularly among immunocompromised individuals, and are associated with high morbidity and mortality. These infections, predominantly caused by

Aspergillus spp.,

Candida spp.,

Cryptococcus neoformans, and mucormycetes, are increasingly recognized in patients with compromised host defenses [

1,

2]. The lungs are a frequent portal of entry for these opportunistic pathogens, and pulmonary involvement can rapidly progress to disseminated disease if not promptly diagnosed and treated [

3].

Certain populations are especially vulnerable to IFRIs, including recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and solid organ transplantation (SOT), patients with hematologic malignancies, individuals undergoing prolonged corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy, and those in intensive care units (ICUs) [

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced an additional at-risk group, as severe SARS-CoV-2 infection has been linked to increased susceptibility to secondary fungal infections such as COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) and mucormycosis [

7,

8,

9]. The convergence of immunosuppression, pulmonary damage, and altered host-microbiome interactions in these settings further complicates timely diagnosis.

A major obstacle in the clinical management of IFRIs remains the delay in diagnosis. Conventional diagnostic methods—including culture, histopathology, serologic markers such as galactomannan and β-D-glucan, and imaging—are often time-consuming, lack sensitivity or specificity, and may require invasive sampling [

10,

11]. Given the nonspecific nature of early symptoms and radiographic findings, IFRIs frequently remain undiagnosed until advanced stages, when therapeutic interventions are less effective [

12]. Diagnostic delays have been directly associated with increased mortality, underscoring the urgent need for novel tools capable of providing rapid and specific results at the point of care [

13].

Recent advances in biosensing technologies offer promising alternatives to traditional diagnostics. In particular, the integration of microfluidic systems and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) into biosensing platforms has enabled the miniaturization and automation of complex laboratory procedures, making them more suitable for bedside or outpatient use [

14,

15]. These platforms allow for the manipulation of minute sample volumes, rapid analyte detection, and the potential for multiplexing, which are critical features in the diagnosis of fungal pathogens that require both speed and specificity [

16].

This review aims to explore recent innovations in microfluidic and MEMS-based biosensing platforms tailored for the diagnosis of IFRIs in immunocompromised patients. It will examine current challenges in fungal diagnostics, the principles of microfluidic and MEMS technologies, and recent examples of biosensor development targeting fungal pathogens. Emphasis will be placed on systems that demonstrate potential for rapid, specific, and minimally invasive point-of-care applications, with a view toward facilitating early diagnosis and improving clinical outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

2. Clinical Challenges in Diagnosing Fungal Respiratory Infections

The clinical diagnosis of IFRIs remains a formidable challenge, particularly in immunocompromised populations, where early detection is critical to prevent dissemination and death. IFRIs are most commonly caused by

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Pneumocystis jirovecii, and

Cryptococcus neoformans, though the exact pathogen profile varies depending on the host’s immune status, underlying condition, and geographic context [

17,

18,

19]. These pathogens can cause rapidly progressive pulmonary disease, yet often present with nonspecific symptoms that mimic other common respiratory conditions, including bacterial pneumonia and viral infections.

One of the key barriers to early diagnosis lies in the non-specificity of both clinical and radiological features. Fever, cough, dyspnea, and chest discomfort may occur, but are not pathognomonic. Radiological findings such as ground-glass opacities, nodules with halo signs, or cavitary lesions are suggestive but not definitive for fungal infection, and may also be seen in malignancies, viral pneumonia, or drug-induced lung injury [

20,

21,

22]. This lack of specificity complicates the diagnostic workup and often delays targeted antifungal therapy.

Another substantial difficulty relates to sample acquisition. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid remains a cornerstone for microbiological and biomarker testing, yet the procedure is frequently contraindicated in critically ill or severely hypoxemic patients due to its invasiveness and risk of decompensation [

23]. Induced sputum may be unreliable in non-productive cough, and lung biopsies, although diagnostic, are rarely feasible outside of select cases due to their invasive nature and associated morbidity [

7].

Current diagnostic methods suffer from significant limitations in sensitivity, specificity, or timeliness. Fungal cultures, although considered the gold standard, are notoriously slow and often yield negative results, particularly in patients who have received prior antifungal therapy or have low fungal burden [

8]. The sensitivity of fungal cultures from BAL fluid or sputum in cases of proven invasive aspergillosis can be as low as 30–50% [

9]. Furthermore, positive cultures may represent colonization rather than true infection, particularly in patients with underlying lung disease.

Non-culture-based methods, such as serological assays, have improved diagnostic capabilities but also pose interpretative challenges. Galactomannan (GM), a component of the

Aspergillus cell wall, is widely used in serum and BAL samples, yet false positives may arise from dietary factors, concurrent antibiotic use (e.g., piperacillin–tazobactam), or cross-reactivity with other fungal species [

10,

11]. β-D-glucan (BDG), a panfungal biomarker, has broader sensitivity but limited specificity, making it less useful for differentiating between fungal species [

12]. Additionally, both assays may yield false negatives in early infection stages or in patients receiving mold-active antifungals.

Imaging plays a crucial role in the diagnostic workup but is rarely definitive. Computed tomography (CT) findings may prompt suspicion for IFRI, but overlap with other causes of pulmonary infiltrates remains a persistent problem. As a result, many clinicians resort to empiric antifungal treatment in high-risk febrile neutropenic patients, which may lead to overtreatment, drug toxicity, increased costs, and antifungal resistance [

13].

The cumulative effect of these limitations is a diagnostic landscape characterized by uncertainty, delayed intervention, and suboptimal outcomes. The need for diagnostic tools that are not only rapid and sensitive, but also minimally invasive and amenable to point-of-care deployment is thus both clear and urgent. In this context, biosensing platforms employing microfluidic and MEMS-based technologies offer a potentially transformative approach to IFRI detection, particularly if designed to integrate sample handling, pathogen detection, and result reporting in a compact format suitable for use in ICUs, transplant wards, or outpatient clinics.

3. Microfluidic Platforms for Fungal Pathogen Detection

3.1. Nucleic Acid Detection

Nucleic acid-based diagnostics have become the cornerstone of infectious disease detection due to their high sensitivity, specificity, and ability to identify pathogens at the species level. For fungal respiratory infections, molecular detection methods—particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and isothermal amplification—offer significant advantages over culture and serological testing, especially when integrated into microfluidic platforms capable of rapid and automated analysis.

Microfluidic systems have been successfully adapted for on-chip PCR to detect fungal DNA in clinical specimens, notably

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Pneumocystis jirovecii, and

Cryptococcus neoformans—the primary pathogens involved in IFRIs in immunocompromised patients [

24,

25,

26]. Such devices can perform thermal cycling within a microchamber, using minimal sample volumes, and drastically reduce time-to-result compared to benchtop PCR systems. Moreover, microfluidic chips facilitate the parallelization of reactions, enabling multiplex detection of multiple fungal targets within a single cartridge [

27].

Isothermal amplification techniques, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), are particularly suited to point-of-care integration because they obviate the need for thermal cycling. LAMP assays targeting

Aspergillus spp.,

P. jirovecii, and

C. neoformans have demonstrated robust performance in clinical studies, with some achieving sensitivities and specificities comparable to conventional quantitative PCR (qPCR) [

28,

29,

30]. Their incorporation into lab-on-a-chip platforms has enabled simplified workflows, making these tools promising candidates for use in resource-limited settings or bedside diagnostics [

31].

Recent advances have also brought CRISPR-Cas systems into the microfluidic domain. CRISPR-based diagnostics, which rely on guide RNA-directed cleavage of target DNA or RNA sequences by Cas enzymes, have shown exceptional potential for fungal pathogen detection. When coupled with pre-amplification strategies such as LAMP or recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), CRISPR-Cas12 and Cas13 platforms can achieve femtomolar sensitivity with high specificity for fungal nucleic acids [

32]. Emerging studies have reported CRISPR-Cas-enabled microfluidic assays capable of distinguishing

Aspergillus fumigatus from other

Aspergillus species in under an hour, demonstrating the potential for rapid species-level identification directly from clinical specimens [

33].

A critical component of integrating nucleic acid detection into microfluidic biosensors is the inclusion of upstream sample processing steps. On-chip lysis, nucleic acid extraction, and purification remain technical bottlenecks but are increasingly being addressed through the incorporation of microvalves, electrokinetic fluid control, and surface-anchored magnetic beads [

34,

35]. Fully integrated devices combining sample input with lysis, purification, amplification, and detection have been developed for respiratory specimens such as BAL fluid or sputum, streamlining the entire workflow into a single cartridge-based system [

36]. These closed-system microfluidic platforms not only minimize contamination risks but also eliminate the need for complex laboratory infrastructure.

3.2. Fungal Antigen Detection

Antigen detection represents one of the most widely used approaches in the diagnosis of IFRIs, offering the ability to detect fungal cell wall components circulating in blood or respiratory fluids. Among the most clinically relevant fungal antigens are GM, BDG, and cryptococcal antigen (CrAg), each of which is a validated biomarker for

Aspergillus spp., multiple pathogenic fungi, and

Cryptococcus neoformans, respectively [

37,

38,

39]. However, traditional antigen detection assays, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and lateral flow assays (LFAs), often require laboratory infrastructure, multistep procedures, and relatively long turnaround times. Recent advances in microfluidics and paper-based biosensing technologies are enabling the miniaturization and acceleration of antigen detection assays, facilitating rapid bedside testing and decentralized diagnostics.

Microfluidic ELISA platforms have been developed to overcome the limitations of conventional bench-top immunoassays by integrating fluid handling, antigen–antibody interactions, and signal readout within a compact chip. For galactomannan detection, microfluidic immunoassays have demonstrated comparable sensitivity to standard ELISA (e.g., Platelia™ Aspergillus), with significantly reduced assay time—often under 30 minutes [

40,

41,

42].

Recent years have seen rapid progress in the miniaturization of fungal antigen assays through microfluidic and paper-based technologies. For galactomannan, microfluidic fluorescence immunosensors have demonstrated on-chip detection using ZnO nanoflower interfaces, highlighting the feasibility of sensitive, pump-free assays in lab-on-a-chip formats [

43]. Broader advances in microfluidic point-of-care testing emphasize portable cartridge designs and automated flow control, enabling immunoassays to be performed outside centralized laboratories [

44,

45].

For BDG, traditionally detected with batch assays such as Fungitell™, research has focused on microfluidic paper-based devices capable of quantitative ELISA on paper substrates. Such platforms reduce assay time, require only microliter sample volumes, and integrate colorimetric readouts that are compatible with smartphone imaging [

46]. These developments suggest that BDG testing is moving closer to true near-patient application.

CrAg detection has also been transformed by digital and microfluidic approaches. The classical LFA remains a global standard, but artificial intelligence–driven mobile phone platforms have been shown to automatically interpret semi-quantitative CrAg LFAs, providing both qualitative and concentration-dependent readouts in real time [

47,

48]. This integration of digital readers with established LFAs represents an important step toward standardized bedside testing, particularly in resource-limited settings.

3.3. Host Response Profiling

Rapid, minimally invasive diagnosis of IFRIs in immunocompromised patients is hampered by low pathogen burden, sampling constraints (e.g., unsafe bronchoscopy), and slow mycological tests. Profiling the host response—the coordinated transcriptomic, proteomic and cellular immune signatures induced by infection—offers a complementary diagnostic axis that (i) can be measured from accessible matrices (whole blood, plasma/serum, finger-prick), (ii) is amenable to lab-on-a-chip miniaturization for point-of-care use, and (iii) may also provide prognostic and treatment-response information.

3.3.1. Blood Transcriptomics and Circulating microRNAs

Whole-blood mRNA signatures can distinguish invasive aspergillosis (IA) from controls even under immunosuppression, provided analytic pipelines control for confounders introduced by steroids and chemotherapy. Steinbrink et al. derived and validated a conserved Aspergillus host-response signature that retained diagnostic accuracy across immunosuppressive states, highlighting feasibility for clinical translation to rapid reverse trancrption qPCR (RT-qPCR) panels on chip [

48,

49]. MicroRNA (miRNA) profiling is similarly promising: specific circulating miRNA patterns supported invasive aspergillosis (IA) diagnosis and prognosis in hematology/oncology cohorts, and miR-132/miR-155 are modulated in human myeloid cells by A. fumigatus [

50,

51,

52]. These nucleic-acid markers align naturally with digital-microfluidic RT-qPCR implementations that deliver multiplexed gene-expression readouts from microliter volumes in under an hour [

53].

3.3.2. Soluble Protein Biomarkers (Cytokines And Pattern-Recognition–Linked Proteins)

Cytokine surrogates of Th1/Th17 inflammation—most consistently interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-8—are elevated in serum and BAL of hematologic patients with IA and have shown added diagnostic value alongside fungal PCR and lateral-flow assays [

54,

55,

56]. Pentraxin-3 (PTX3), a humoral pattern-recognition molecule produced by myeloid/endothelial cells, is increased in plasma/BAL in IPA, augments galactomannan performance, and has emerging prognostic utility (mortality risk stratification; treatment-response kinetics) [

57,

58,

59,

60]. Such proteins are ideal targets for multiplex immunoassays on microfluidic chips (bead-based, droplet-based, or electrochemical) capable of parallel IL-6/IL-8/PTX3 detection from a finger-prick [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

3.3.3. Antigen-Specific T-Cell Responses

Aspergillus-reactive T-cell assays [Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot (ELISpot)/ELISA for interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-10] detect skewed Th1/Th2 responses during IA and have been explored for early diagnosis and immune monitoring in hematology and post-transplant settings [

66,

67,

68]. Microfluidic single-cell platforms further enable high-throughput immune phenotyping (e.g., cytokine secretion profiling from individual PBMCs), reducing assay time and sample volume [

62].

3.3.4. Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia (PCP): Multi-Omics Host Signatures

In PCP, dynamic host responses across disease course have been characterized by multi-omic and immunophenotyping studies, revealing distinct cytokine milieus and lymphocyte perturbations driven by the type/degree of immunosuppression [

69,

70,

71]. While serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan remains pathogen-directed, host profiles (e.g., IL-6/IL-8, composite inflammatory indices) can improve risk prediction and may be adapted to rapid chips for rule-in/rule-out strategies when bronchoscopy is not feasible [

55,

71].

3.3.5. Microfluidic/MEMS Enablement and Sample-to-Answer Workflows

Microfluidic and MEMS technologies now support integrated host-response testing. Digital-microfluidic RT-qPCR cartridges for multiplex host-gene signatures using whole blood, with on-cartridge extraction and 30–60 min turnaround [

52]. Bead-array or droplet microfluidic immunoassays quantifying IL-6/IL-8/PTX3 (and additional cytokines) in <30 min from ≤50 µL serum, with analytical sensitivities in the low pg/mL range [

60]. Electrochemical/photonic/MEMS sensors [e.g., silicon nanowire Field-Effect Transistors (FETs)] for ultrasensitive IL-6 and related markers, compatible with portable readers for bedside testing [

63,

64].

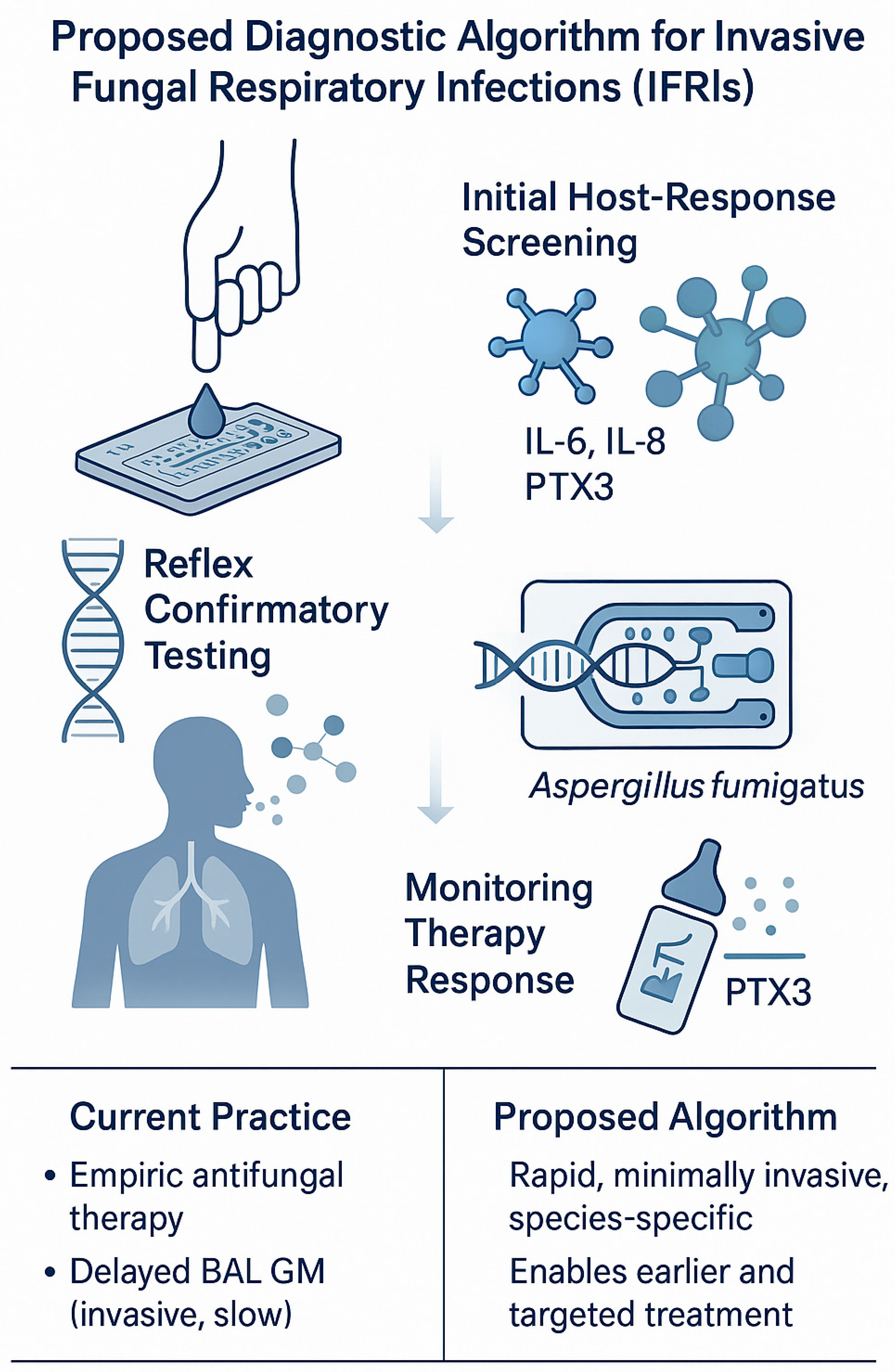

A tiered algorithm is therefore feasible: (i) finger-prick host-response panel (IL-6/IL-8/PTX3 ± parsimonious mRNA signature) to triage high-risk immunocompromised patients with new pulmonary infiltrates; (ii) reflex pathogen-directed testing [e.g., plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA)/Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) or respiratory PCR] when host test is positive or indeterminate; and (iii) serial host-marker monitoring (e.g., PTX3) to assess therapeutic response and prognosis [

57,

58,

59].

4. MEMS-Based Tools in Fungal Diagnosis

4.1. VOC Detection from Exhaled Breath

Non-invasive detection of IPA through analysis of exhaled volatile organic compounds (VOCs) represents a rapidly evolving frontier in fungal diagnostics.

Aspergillus fumigatus and other filamentous fungi emit unique VOCs during metabolic processes, including compounds such as 2-pentylfuran, α-trans-bergamotene, β-trans-bergamotene, and trans-geranylacetone, which can be detected in the breath of infected patients [

72].

MEMS-based gas sensors are ideally suited for capturing these VOC signatures due to their small footprint, low power requirements, and capacity for real-time, label-free detection. Recent advances have enabled MEMS sensors to detect fungal VOCs with high sensitivity and selectivity at concentrations relevant to human breath. Arabi et al. (2022) developed MEMS-based bifurcation gas sensors capable of detecting volatile biomarkers such as hydrogen sulfide and formaldehyde, achieving detection thresholds as low as 1 ppm [

73]. While these gases are not specific to fungi, the study highlights the precision and miniaturization potential applicable to fungal metabolite detection.

Electronic nose (e-nose) systems integrating MEMS chemiresistive sensors, quartz crystal microbalances (QCM), and field asymmetric ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) have demonstrated strong performance in identifying

Aspergillus-specific VOC profiles. For example, a study using porphyrin-coated QCM sensors successfully distinguished

A. fumigatus from

A. terreus and other fungi with classification accuracies exceeding 85% in test datasets [

74]. Similarly, FAIMS-MEMS platforms have shown promise for multiplex fungal VOC detection under clinical conditions [

75].

Perhaps the most clinically relevant progress comes from breathomics research. Koo et al. identified a panel of fungal VOCs from patients with confirmed IPA, including α- and β-trans-bergamotene and trans-geranylacetone, and reported clear separation between IPA and non-IPA groups using breath samples [

72]. These findings have since been translated into patented biosensor designs, such as those described in US Patent US10227629B2, which proposes selective detection of IPA using MEMS sensors tuned to fungal sesquiterpenes [

76].

To enhance specificity and usability, modern MEMS VOC biosensors incorporate functionalized sensing layers, such as metal oxide semiconductors (e.g., SnO

2, ZnO), graphene derivatives, and molecularly imprinted polymers that preferentially bind fungal metabolites [

77]. Sensor responses are typically interpreted using machine learning algorithms or multivariate statistical models (e.g., PCA, LDA, random forest), enabling differentiation of fungal infections from bacterial or viral mimics [

78].

Clinical implementation of these systems is increasingly feasible, given their compatibility with handheld devices, breath collectors, and portable data analysis modules. A fluorescence-based MEMS microfluidic sensor capable of detecting fungal antigens in under 40 minutes using exhaled breath condensate or serum [

79].

4.2. Mechanical Biosensors

Mechanical biosensors, including cantilever-based and resonant mass sensors, are increasingly recognized as powerful tools for the label-free and real-time detection of fungal biomarkers such as DNA and cell wall antigens. These micro- and nanoelectromechanical systems [MEMS and Nanoelectromechanical Systems (NEMS)] operate by transducing biomolecular interactions into measurable mechanical signals—typically changes in mass, resonance frequency, or surface stress—without requiring enzymatic or fluorescent labels. This makes them ideally suited for integration into compact, high-throughput diagnostic platforms targeting fungal infections in immunocompromised patients.

Cantilever biosensors function analogously to atomic force microscopy probes. They are typically coated with specific capture molecules—such as antibodies, DNA probes, or aptamers—on one surface. When the target analyte binds, it induces surface stress or changes in mass that cause the cantilever to deflect or shift its resonant frequency. These shifts can be detected optically (via laser reflection) or electrically (via piezoresistive or capacitive methods). Several studies have successfully employed this technology for the detection of fungal antigens, including galactomannan and cryptococcal capsular polysaccharides, as well as for DNA sequences specific to

Aspergillus fumigatus and

Candida albicans [

80].

Recent work has demonstrated that micro- or nano-mechanical cantilever sensors functionalized with genetic probes (e.g., thiol-modified oligonucleotides on gold surfaces) can detect DNA hybridization via changes in cantilever resonance frequency or bending. For example, Mishra & Hegner developed a nanomechanical cantilever sensor that showed femtomolar sensitivity for in-situ hybridization in a pure target environment [

81].

Another relevant study by Nugaeva et al., functionalized gold-coated (and uncoated) silicon cantilevers with proteins to capture fungal spores (e.g.,

Aspergillus niger) and detected spore binding and growth via resonance-frequency shifts [

82].

A biosensor fabricated by Liu et al. used Dectin-1 immobilization on a composite film (Nafion-thionine-AuNP-chitosan) to measure β-glucan in serum. Binding of β-glucans inhibited electron transfer and produced measurable amperometric suppression; the assay showed acceptable speed, accuracy, and stability [

83].

4.3. Device-Associated Fungal Biofilm Monitoring

Indwelling medical devices such as central venous catheters, urinary catheters, and endotracheal tubes are critical in the care of immunocompromised patients, yet they also serve as key substrates for fungal biofilm formation.

Candida albicans,

Candida glabrata, and

Aspergillus fumigatus are among the most common fungal pathogens implicated in device-associated infections, which are notoriously resistant to antifungal therapy due to the protective biofilm matrix and altered metabolic state of the organisms [

84].

Detection of biofilms on medical devices currently relies on indirect clinical signs (e.g., persistent fever despite therapy) or requires device removal for culture and microscopy, leading to diagnostic delay. In this context, MEMS-based biosensors embedded within or onto indwelling devices offer a transformative approach for real-time, in situ monitoring of fungal biofilm formation.

Detection of biofilms on medical devices currently relies on indirect clinical signs or device removal for culture and microscopy, leading to diagnostic delay. In this context, embedding MEMS-class biosensors on or within indwelling devices is a promising route for real-time, in situ monitoring of fungal colonization and biofilm growth. Early demonstrations with micromechanical cantilevers showed label-free detection of immobilized fungal cells via resonance-frequency shifts—for example, Nugaeva et al. used antibody/lectin-functionalized silicon cantilever arrays to capture

Aspergillus niger and

Candida spp., with mass-loading readouts in dynamic mode [

83,

85]. For

Candida spp. label-free impedance approaches can directly sense yeast attachment: a membrane-based electrochemical impedance sensor with anti-

Candida capture enabled specific detection of

C. albicans [

86], and subsequent work has refined Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) workflows for

Candida spp. in clinical matrices (e.g., urine) with rapid, reagent-light measurements [

87,

88]. Recent reviews focused specifically on

Candida spp. biosensing highlight optical and electrochemical platforms (including microfluidic/EIS integrations) as viable paths toward catheter-compatible monitoring of fungal biofilms, while noting that fully embedded, clinical-grade MEMS devices for fungi remain an active translational frontier [

90,

91].

5. Translational Applications in Immunocompromised Settings

The development of microfluidic and MEMS-based biosensing platforms holds substantial translational potential across a spectrum of clinical settings where immunocompromised patients are at risk of IFRIs. These technologies, capable of rapid, sensitive, and minimally invasive diagnostics, can be strategically deployed to address the unique challenges of fungal detection in ICUs, hematology-oncology departments, transplant centers, and even home-based environments.

In the ICU, ventilated patients often develop non-specific respiratory deterioration where rapid differentiation among bacterial, viral, and fungal etiologies is critical. Severe influenza and COVID-19 are established risk factors for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis [Influenza-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis (IAPA)/CAPA], with multicenter ICU data and consensus guidance underscoring excess morbidity and mortality when diagnosis is delayed [

6,

91]. Noninvasive fungal breath diagnostics show promise: targeted VOC profiles in exhaled breath distinguished proven/probable invasive aspergillosis with high sensitivity and specificity in a clinical cohort [

73] and exhaled-breath condensate (EBC) GM testing has demonstrated feasibility against BAL GM in immunocompromised populations and in ventilated ICU patients [

79,

92].

In hematology–oncology patients during post-chemotherapy neutropenia, preemptive strategies anchored on serial serum GM plus high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) have reduced empiric antifungal exposure while maintaining outcomes [

93]. For earlier rule-in testing, BAL GM is analytically and clinically validated (systematic reviews/meta-analyses), and bedside Aspergillus GM LFAs—including reader-assisted formats—provide 15–45-minute turnaround and have shown useful performance in cancer and ICU cohorts [

94,

95,

96].

In transplant units, where febrile neutropenia is common and sample volumes are limited, pairing rapid serum/respiratory GM LFA with BAL GM (when feasible) supports risk-adapted antifungal initiation while minimizing unnecessary drug exposure [

94,

95,

96]. Beyond the inpatient setting, longitudinal surveillance is emerging: electronic-nose breath profiling has detected

Aspergillus fumigatus airway colonization in cystic fibrosis patients, suggesting a feasible outpatient monitoring pathway that could, after validation for invasive disease, enable earlier intervention post-discharge [

97].

A proposed diagnostic algorithm integrating host-response screening, reflex confirmatory testing, and monitoring is shown in

Figure 1.

A comparative summary of the biosensor platforms including target analytes, sample types, performance metrics, and clinical validation stages—is provided in

Table 1.

6. Clinical Validation Gaps and Real-World Performance

Although recent developments in microfluidic and MEMS-based fungal diagnostics have shown considerable technical promise, most platforms remain in early stages of clinical evaluation, with limited validation in immunocompromised patient populations. Many of the cited studies reporting high sensitivity and specificity for techniques such as microfluidic LAMP, CRISPR-based nucleic acid assays, and antigen detection methods—including galactomannan and β-D-glucan—are based on small single-center cohorts, often comprising fewer than 100 subjects, and frequently lack comparison against standardized clinical reference methods such as bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan, PCR, or EORTC/MSG criteria [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

40,

41,

42,

43].

While digital CrAg lateral flow assays have achieved broader clinical deployment, including semi-quantitative reader-assisted formats that demonstrate diagnostic accuracies exceeding 95% [

47,

48], other platforms such as microfluidic BDG assays, host-response transcriptomic panels, multiplex cytokine biosensors, and MEMS-based volatile organic compound sensors remain in the preclinical or pilot-testing phase [

46,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Most evaluations have been limited to controlled settings or proof-of-concept studies without robust real-world validation in hematology–oncology, transplant, or intensive care unit cohorts. In addition, the reported diagnostic performance is often confounded by heterogeneous sampling protocols, lack of antifungal exposure stratification, and absence of gold-standard comparators.

Mechanical and impedance-based biosensors targeting fungal DNA, cell wall antigens, or device-associated biofilms have demonstrated high analytical sensitivity in vitro but have not yet progressed to clinical trials [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

91]. No published studies currently support their performance in real clinical matrices such as serum, BAL fluid, or urine.

To support clinical translation, future research should focus on well-powered, prospective, multicenter studies using harmonized definitions of invasive fungal disease. Real-world performance assessments in diverse immunocompromised populations, alongside standardized cost-effectiveness and implementation analyses, will be essential to determine the true diagnostic value of these biosensing platforms

7. Regulatory and Economic Considerations

In addition to analytical and clinical performance, the successful translation of biosensor-based diagnostics for IFRIs depends on regulatory classification, reimbursement potential, and economic feasibility. In the United States, POC devices must meet the criteria for Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) waiver, which requires demonstration of analytical simplicity, minimal risk of erroneous results, and ease of use by non-laboratory personnel. To date, most fungal diagnostics, including the Platelia™ GM and Fungitell™ BDG assays, are not CLIA-waived and remain confined to centralized laboratories due to their technical complexity and sample preparation requirements [

40,

41,

42,

43,

46].

Emerging POC platforms—such as microfluidic LAMP [

28,

29,

30,

31], CRISPR-Cas-based diagnostics [

32,

33], and MEMS VOC sensors [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]—may be eligible for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance or Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) if supported by multicenter clinical validation and usability studies. However, no such platforms have yet progressed beyond the prototype stage. Reimbursement pathways remain uncertain, particularly for biosensors not yet associated with established Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. While reader-assisted CrAg lateral flow assays have shown clinical promise and could be eligible for POC implementation [

47,

48], microfluidic BDG or GM platforms, as well as host-response panels based on transcriptomics or cytokines [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], would likely require new cost-effectiveness evaluations and health technology assessments. Economic feasibility will be especially important in immunocompromised populations managed in outpatient settings or low-resource hospitals, where high test throughput, sample-type compatibility (e.g., serum, BAL, breath), and device portability are critical for adoption.

8. Current Limitations and Future Opportunities

Despite rapid progress in microfluidic and MEMS-based biosensors for fungal diagnostics, several hurdles must be addressed before routine clinical use. Chief among these are the scarcity of multicenter clinical validations in at-risk populations, with most reports still benchtop or single-center proofs-of-concept; even promising noninvasive breath-VOC approaches emphasize the need for more in-vivo, clinically powered studies [

90,

98]. Standardization is another critical gap—particularly for fungal VOCs, where marker panels vary with strain, growth phase, media, host metabolism, and environmental background. Signature sesquiterpenes (e.g., α-/β-trans-bergamotene, trans-geranylacetone) can differentiate invasive aspergillosis in small cohorts, but broader reproducibility across centers and standardized sampling are still required [

98,

99].

From a sample-handling standpoint, performance in real matrices (serum, BAL, exhaled breath condensate) is limited by biofouling and matrix effects on transducer surfaces, as well as material interactions in microfluidic devices (e.g., hydrophobic small-molecule absorption into PDMS). Antifouling coatings [zwitterionic, peptide, hydrogel, Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM)-based] and interface engineering improve robustness but are not yet harmonized across platforms [

100,

101,

102].

Looking forward, three trends are especially promising. First, artificial intelligence/machine learning-assisted interpretation [e.g., Support Vector Machines (SVMs), random forests, neural networks] can learn complex, multianalyte patterns from VOC or label-free sensor outputs, potentially boosting accuracy and enabling bedside triage [

103]. Second, multiplexed panels that integrate pathogen targets (antigens/NAs/VOCs) with host-response markers may help discriminate colonization from invasive disease and support risk-adapted therapy [

90]. Third, miniaturized, cartridge-based fungal diagnostics are feasible: for candidemia, T2MR panels already deliver species-level results directly from whole blood in ~3–4 h with high accuracy in pooled analyses—illustrating a translational pathway for future MEMS/microfluidic fungal platforms [

90,

104]. Strategic collaborations among academic labs, clinical microbiology, and industry will be essential to deliver validated, standardized, and cost-effective fungal biosensors.

9. Conclusions

The rapid evolution of biosensor technologies—ranging from microfluidic nucleic acid amplification to MEMS-based breath analyzers—offers unprecedented potential for point-of-care diagnosis of IFRIs in immunocompromised patients. These platforms can achieve high analytical sensitivity and specificity, rapid turnaround, and compatibility with minimally invasive sample types such as serum, BAL fluid, and exhaled breath. Furthermore, innovations in host-response profiling and AI-based signal interpretation may enable more nuanced diagnostic strategies that go beyond pathogen detection alone.

However, despite the technical maturity of many platforms, clinical translation remains limited. As described above, most devices have only been evaluated in small, preclinical, or single-center pilot studies, often without stratification by host immune status or antifungal exposure. Comparative performance against established gold standards such as BAL galactomannan, PCR, or EORTC/MSG-defined criteria is frequently lacking, and real-world validation in high-risk settings—such as HSCT, SOT, and ICU cohorts—remains sparse. Without such evidence, the diagnostic utility of these biosensors cannot yet be generalized to the broader clinical population.

To realize the promise of these technologies, future efforts must prioritize multicenter validation, robust comparator trials, and economic feasibility studies tailored to the unique clinical contexts in which IFRIs occur. Until then, biosensor platforms should be regarded as promising adjuncts rather than replacements for existing diagnostic tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C.P.; Data curation, V.E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C.P. and V.E.G..; writing—review and editing, V.C.P.; supervision, V.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mtibaa, L.; Jebari, M.; Ghedira, H.; Baccouchi, N.; Zriba, S.; Msadek, F.; Jemli, B. Invasive fungal infection in patients with hematologic malignancies: epidemiology and prognostic factors. Pan Afr. Med J. 2024, 48, 130. [CrossRef]

- Marr, K.A.; Carter, R.A.; Crippa, F.; Wald, A.; Corey, L. Epidemiology and Outcome of Mould Infections in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 909–917. [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, C.; Denning, D.W. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax 2015, 70, 270–277. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Paterson, D.L. AspergillusInfections in Transplant Recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 44–69. [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Alexander, B.D.; Andes, D.R.; Hadley, S.; Kauffman, C.A.; Freifeld, A.; Anaissie, E.J.; Brumble, L.M.; Herwaldt, L.; Ito, J.; et al. Invasive Fungal Infections among Organ Transplant Recipients: Results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1101–1111. [CrossRef]

- Schauwvlieghe, A.F.A.D.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Philips, N.; Verwijs, R.; Vanderbeke, L.; Van Tienen, C.; Lagrou, K.; Verweij, P.E.; Van De Veerdonk, F.L.; Gommers, D.; et al. Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 782–792. [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Seidel, D.; Sprute, R.; Cunha, C.; Oliverio, M.; Goldman, G.H.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Carvalho, A. COVID-19-associated fungal infections. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1127–1140. [CrossRef]

- White, P.L.; Dhillon, R.; Cordey, A.; Hughes, H.; Faggian, F.; Soni, S.; Pandey, M.; Whitaker, H.; May, A.; Morgan, M.; et al. A National Strategy to Diagnose Coronavirus Disease 2019–Associated Invasive Fungal Disease in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e1634–e1644. [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Liang, G.; Liu, W. Fungal Co-infections Associated with Global COVID-19 Pandemic: A Clinical and Diagnostic Perspective from China. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, M.; Anagnostou, T.; Fuchs, B.B.; Caliendo, A.M.; Mylonakis, E. Molecular and Nonmolecular Diagnostic Methods for Invasive Fungal Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 490–526. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Sanborn, D.; Vergidis, P.; Razonable, R.; Yadav, H.; Pennington, K.M. Diagnosis and Prevention of Invasive Fungal Infections in the Immunocompromised Host. Chest 2024, 167, 374–386. [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arenz, D.; Chen, S.C.A.; Dannaoui, E.; Hochhegger, B.; Hoenigl, M.; Jensen, H.E.; Lagrou, K.; Lewis, R.E.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e405–e421. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, J.; Lodewyck, T.; Donnelly, J.P.; Chantepie, S.; Robin, C.; Blijlevens, N.; Turlure, P.; Selleslag, D.; Baron, F.; Aoun, M.; et al. Empiric vs Preemptive Antifungal Strategy in High-Risk Neutropenic Patients on Fluconazole Prophylaxis: A Randomized Trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 674–682. [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.D.; Laksanasopin, T.; Cheung, Y.K.; Steinmiller, D.; Linder, V.; Parsa, H.; Wang, J.; Moore, H.; Rouse, R.; Umviligihozo, G.; et al. Microfluidics-based diagnostics of infectious diseases in the developing world. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1015–1019. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Y.; Singh, S.P. Recent Advances in Bio-MEMS and Future Possibilities: An Overview. J. Inst. Eng. (India): Ser. B 2023, 104, 1377–1388. [CrossRef]

- Garnacho-Montero, J.; Barrero-García, I.; León-Moya, C. Fungal infections in immunocompromised critically ill patients. J. Intensiv. Med. 2024, 4, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Fraser, J.A.; Doering, T.L.; Wang, Z.A.; Janbon, G.; Idnurm, A.; Bahn, Y.-S. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the Etiologic Agents of Cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a019760–a019760. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.F.J.; Limper, A.H. Pneumocystis Pneumonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2487–2498. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, S.P.; Sipsas, N.V.; Marom, E.M.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. The Diagnostic Value of Halo and Reversed Halo Signs for Invasive Mold Infections in Compromised Hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 1144–1155. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lim, C.; Lee, S.-O.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, Y.S.; Woo, J.H.; Song, J.-W.; Kim, M.Y.; Chae, E.J.; Do, K.-H.; et al. Computed tomography findings in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic transplant recipients and neutropenic patients, and their prognostic value. J. Infect. 2011, 63, 447–456. [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, S.; Lu, Z. CT findings and differential diagnosis in adults with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Radiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Bay, P.; de Prost, N. Diagnostic approach in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. J. Intensiv. Med. 2024, 5, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Alanio, A.; Desoubeaux, G.; Sarfati, C.; Hamane, S.; Bergeron, A.; Azoulay, E.; Molina, J.M.; Derouin, F.; Menotti, J. Real-time PCR assay-based strategy for differentiation between active Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and colonization in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 1531–1537. [CrossRef]

- Fillaux, J.; Malvy, S.; Alvarez, M.; Fabre, R.; Cassaing, S.; Marchou, B.; Linas, M.-D.; Berry, A. Accuracy of a routine real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 75, 258–261. [CrossRef]

- Zono, B.B.; Sacheli, R.; Kasumba, D.M.; Situakibanza, H.N.-T.; Mavanga, A.; Anyshayi, J.M.; Etondo, M.; Muwonga, J.; Moutschen, M.; Mvumbi, G.L.; et al. Screening for cryptococcal antigenemia and meningeal cryptococcosis, genetic characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans in asymptomatic patients with advanced HIV disease in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Liu, S.; Sui, G. Microfluidic System for Rapid Detection of Airborne Pathogenic Fungal Spores. ACS Sensors 2018, 3, 2095–2103. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Tian, S.; Yu, N.; Zhang, X.; Jia, X.; Zhai, H.; Sun, Q.; Han, L. Development and Evaluation of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Method for Rapid Detection of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 950–955. [CrossRef]

- Scharmann, U.; Kirchhoff, L.; Buer, J.; Schuler, F.; Serr, A.; Rößler, S.; Held, J.; Szumlanski, T.; Steinmann, J.; Rath, P.-M. Evaluation of the Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay (LAMP) Eazyplex® Pneumocystis jirovecii. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 300. [CrossRef]

- Stivanelli P, Tararam CA, Trabasso P, Levy LO, Melhem MSC, Schreiber AZ, Moretti ML. Visible DNA microarray and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the identification of Cryptococcus species recovered from culture medium and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2020 Oct 9;53(11):e9056. doi: 10.1590/1414-431 × 20209056.

- Khanjani, E.; Fergola, A.; Martínez, J.A.L.; Nazarnezhad, S.; Terre, J.C.; Marasso, S.L.; Aghajanloo, B. Capillary microfluidics for diagnostic applications: fundamentals, mechanisms, and capillarics. Front. Lab a Chip Technol. 2025, 4, 1502127. [CrossRef]

- Kostyusheva, A.; Brezgin, S.; Babin, Y.; Vasilyeva, I.; Glebe, D.; Kostyushev, D.; Chulanov, V. CRISPR-Cas systems for diagnosing infectious diseases. Methods 2022, 203, 431–446. [CrossRef]

- Luan, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Luan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Langford, P.R.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, G. A CRISPR/Cas12a-assisted rapid detection platform by biosensing the apxIVA of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 928307. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Johnson, M.; Hill, P.; Gale, B.K. Microfluidic sample preparation: cell lysis and nucleic acid purification. Integr. Biol. 2009, 1, 574–586. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, Y.; You, M.; Hu, J.; Yao, C.; Cao, L.; Xu, F. Fully integrated microfluidic devices for qualitative, quantitative and digital nucleic acids testing at point of care. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 177, 112952–112952. [CrossRef]

- Mabey, D.; Peeling, R.W.; Ustianowski, A.; Perkins, M.D. Diagnostics for the developing world. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 231–240. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.F.; Thompson, G.R., III; Denning, D.W.; Fishman, J.A.; Hadley, S.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Morrison, V.A.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e1–e60. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, J.A.; Klont, R.; Masson, C.; Theunissen, K.; Meersseman, W.; Lagrou, K.; Heinen, C.; Crepin, B.; Eldere, J.V.; Tabouret, M.; et al. Optimization of the Cutoff Value for the Aspergillus Double-Sandwich Enzyme Immunoassay. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 1329–1336. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, J.N.; Percival, A.; Bauman, S.; Pelfrey, J.; Meintjes, G.; Williams, G.N.; Longley, N.; Harrison, T.S.; Kozel, T.R. Evaluation of a Novel Point-of-Care Cryptococcal Antigen Test on Serum, Plasma, and Urine From Patients With HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 1019–1023. [CrossRef]

- White, P.L.; Price, J.S.; Posso, R.; Vale, L.; Backx, M. An Evaluation of the Performance of the IMMY Aspergillus Galactomannan Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay When Testing Serum To Aid in the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58. [CrossRef]

- Dichtl, K.; Forster, J.; Ormanns, S.; Horns, H.; Suerbaum, S.; Seybold, U.; Wagener, J. Comparison of β-D-Glucan and Galactomannan in Serum for Detection of Invasive Aspergillosis: Retrospective Analysis with Focus on Early Diagnosis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 253. [CrossRef]

- Piguillem, S.V.; Regiart, M.; Bertotti, M.; Raba, J.; Messina, G.A.; Fernández-Baldo, M.A. Microfluidic fluorescence immunosensor using ZnONFs for invasive aspergillosis determination. Microchem. J. 2020, 159. [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, S.; Davis, R.W.; Saha, A.K. Microfluidic Point-of-Care Testing: Commercial Landscape and Future Directions. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 602659. [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Salazar, J.R.; Rodrigues Cruz, K.; Materon Vasques, E.M. Microfluidic Point-of-Care Devices: New Trends and Future Prospects for eHealth Diagnostics. Sensors 2020, 20, 1951. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Hahn, C.; Herchen, S.; Soucy, A.; Carpio, E.; Harper, S.; Rahmani, N.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Faghri, M. A Microfluidic Paper-Based Lateral Flow Device for Quantitative ELISA. Micro 2024, 4, 348–367. [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Peláez, D.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Medina, N.; Capellán-Martín, D.; Bonilla, O.; Luengo-Oroz, M.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J.L. Artificial intelligence-driven mobile interpretation of a semi-quantitative cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay. IMA Fungus 2024, 15, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Peláez, D.; Medina, N.; Álamo, E.; Soto-Debran, J.C.; Bonilla, O.; Luengo-Oroz, M.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A. Digital Platform for Automatic Qualitative and Quantitative Reading of a Cryptococcal Antigen Point-of-Care Assay Leveraging Smartphones and Artificial Intelligence. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 217. [CrossRef]

- Steinbrink, J.M.; Zaas, A.K.; Betancourt, M.; Modliszewski, J.L.; Corcoran, D.L.; McClain, M.T. A transcriptional signature accurately identifies Aspergillus Infection across healthy and immunosuppressed states. Transl. Res. 2020, 219, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Tolnai, E.; Fidler, G.; Szász, R.; Rejtő, L.; Nwozor, K.O.; Biró, S.; Paholcsek, M. Free circulating mircoRNAs support the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies and neutropenia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Fidler, G.; Szilágyi-Rácz, A.A.; Dávid, P.; Tolnai, E.; Rejtő, L.; Szász, R.; Póliska, S.; Biró, S.; Paholcsek, M. Circulating microRNA sequencing revealed miRNome patterns in hematology and oncology patients aiding the prognosis of invasive aspergillosis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, M.; Fliesser, M.; Springer, J.; Breitschopf, T.; Schlossnagel, H.; Schmitt, A.-L.; Kurzai, O.; Hünniger, K.; Einsele, H.; Löffler, J. Aspergillus fumigatus induces microRNA-132 in human monocytes and dendritic cells. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 2014, 304, 592–596. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, K.; Sun, Y.; Luo, D.; Wang, M.; Chen, T.; Li, M.; Duan, J.; Huang, L.; Dong, C. A Digital Microfluidic RT-qPCR Platform for Multiple Detections of Respiratory Pathogens. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1650. [CrossRef]

- Heldt, S.; Eigl, S.; Prattes, J.; Flick, H.; Rabensteiner, J.; Prüller, F.; Niedrist, T.; Neumeister, P.; Wölfler, A.; Strohmaier, H.; et al. Levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 are elevated in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of haematological patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2017, 60, 818–825. [CrossRef]

- Heldt, S.; Prattes, J.; Eigl, S.; Spiess, B.; Flick, H.; Rabensteiner, J.; Johnson, G.; Prüller, F.; Wölfler, A.; Niedrist, T.; et al. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in hematological malignancy patients: Performance of cytokines, Asp LFD, and Aspergillus PCR in same day blood and bronchoalveolar lavage samples. J. Infect. 2018, 77, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, S.A.; Heldt, S.; Prattes, J.; Eigl, S.; Jenks, J.D.; Flick, H.; Rabensteiner, J.; Prüller, F.; Wölfler, A.; Neumeister, P.; et al. Using Interleukin 6 and 8 in Blood and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid to Predict Survival in Hematological Malignancy Patients With Suspected Pulmonary Mold Infection. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1798. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, M.; Feng, C. The role of pentraxin3 in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in COPD patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Cai, X.; Zhong, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Cao, M.; Wang, L.; et al. Pentraxin-3 as a novel prognostic biomarker in non-neutropenic invasive pulmonary aspergillosis patients. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0294524. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-F.; Wang, F.-D.; Huang, C.-C.; Chou, K.-T.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wu, P.-F.; Lee, C.-T.; Yang, Y.-Y. Monitoring treatment response using serial PTX3 levels in chronic and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 578, 120553. [CrossRef]

- Gandolpho, L.S.; Francisco, E.C.; Breda, G.L.; Arrais-Rodrigues, C.; Colombo, A.L. Pentraxin 3 as a Potential Biomarker of Invasive Fusariosis in Onco-Haematological Patients. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70095. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, D.; Qian, W.; Tin, C.; Sun, D.; Chen, W.; Lam, R.H.W. A fluorescent microbead-based microfluidic immunoassay chip for immune cell cytokine secretion quantification. Lab a Chip 2018, 18, 522–531. [CrossRef]

- Tanak, A.S.; Muthukumar, S.; Krishnan, S.; Schully, K.L.; Clark, D.V.; Prasad, S. Multiplexed cytokine detection using electrochemical point-of-care sensing device towards rapid sepsis endotyping. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 171, 112726–112726. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, X.; Sun, S. Microfluidic Biosensors: Enabling Advanced Disease Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 1936. [CrossRef]

- Majdinasab, M.; de la Chapelle, M.L.; Marty, J.L. Recent Progresses in Optical Biosensors for Interleukin 6 Detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 898. [CrossRef]

- Crapnell, R.D.; Jesadabundit, W.; Ferrari, A.G.-M.; Dempsey-Hibbert, N.C.; Peeters, M.; Tridente, A.; Chailapakul, O.; Banks, C.E. Toward the Rapid Diagnosis of Sepsis: Detecting Interleukin-6 in Blood Plasma Using Functionalized Screen-Printed Electrodes with a Thermal Detection Methodology. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 5931–5938. [CrossRef]

- Potenza, L.; Barozzi, P.; Vallerini, D.; Bosco, R.; Quadrelli, C.; Mediani, L.; Morselli, M.; Forghieri, F.; Volzone, F.; Codeluppi, M.; et al. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis by tracking Aspergillus-specific T cells in hematologic patients with pulmonary infiltrates. Leukemia 2007, 21, 578–581. [CrossRef]

- Bettelli, F.; Vallerini, D.; Lagreca, I.; Barozzi, P.; Riva, G.; Nasillo, V.; Paolini, A.; D’aMico, R.; Forghieri, F.; Morselli, M.; et al. Identification and validation of diagnostic cut-offs of the ELISpot assay for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in high-risk patients. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0306728. [CrossRef]

- Lauruschkat, C.D.; Page, L.; Etter, S.; Weis, P.; Gamon, F.; Kraus, S.; Einsele, H.; Wurster, S.; Loeffler, J. T-Cell Immune Surveillance in Allogenic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: Are Whole Blood–Based Assays Ready to Challenge ELISPOT?. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 8, ofaa547. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-Q.; Sun, H.; Li, K.; Shao, M.-M.; Zhai, K.; Tong, Z.-H. Dynamics of host immune responses and a potential function of Trem2hi interstitial macrophages in Pneumocystis pneumonia. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, H.-Q.; Tong, Z.; Song, N. Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal the altered transcriptomic characteristics of pulmonary macrophages in immunocompromised hosts with Pneumocystis pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1179094. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Cui, X.; Jia, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y. Peripheral immune phenotypes and T cell receptor repertoire in pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-1 infected patients. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 237, 108985. [CrossRef]

- Póvoa, P.; Coelho, L.; Cidade, J.P.; Ceccato, A.; Morris, A.C.; Salluh, J.; Nobre, V.; Nseir, S.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Lisboa, T.; et al. Biomarkers in pulmonary infections: a clinical approach. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2024, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Thomas, H.R.; Daniels, S.D.; Lynch, R.C.; Fortier, S.M.; Shea, M.M.; Rearden, P.; Comolli, J.C.; Baden, L.R.; Marty, F.M. A Breath Fungal Secondary Metabolite Signature to Diagnose Invasive Aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 1733–1740. [CrossRef]

- Arabi, M.; Alghamdi, M.; Kabel, K.; Labena, A.; Gado, W.S.; Mavani, B.; Scott, A.J.; Penlidis, A.; Yavuz, M.; Abdel-Rahman, E. Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds by Using MEMS Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 4102. [CrossRef]

- Capuano, R.; Paba, E.; Mansi, A.; Marcelloni, A.M.; Chiominto, A.; Proietto, A.R.; Zampetti, E.; Macagnano, A.; Lvova, L.; Catini, A.; et al. Aspergillus Species Discrimination Using a Gas Sensor Array. Sensors 2020, 20, 4004. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Lei, C.; Liang, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ghaffar, A.; Xiong, J. Multi-Channel MEMS-FAIMS Gas Sensor for VOCs Detection. Micromachines 2023, 14, 608. [CrossRef]

- Koo S, Thomas HR, Baden LR, Marty FM. Diagnosis and treatment of invasive aspergillosis. US Patent 10,227,629 B2. Filed 4 Jun 2015. Published 12 Mar 2019. Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/US10227629B2/en.

- Pathak, A.K.; Swargiary, K.; Kongsawang, N.; Jitpratak, P.; Ajchareeyasoontorn, N.; Udomkittivorakul, J.; Viphavakit, C. Recent Advances in Sensing Materials Targeting Clinical Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Biomarkers: A Review. Biosensors 2023, 13, 114. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; S, S.; Varma, P.; Sreelekha, G.; Adak, C.; Shukla, R.P.; Kamble, V.B. Metal oxide-based gas sensor array for VOCs determination in complex mixtures using machine learning. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Bhimji, A.; Bhaskaran, A.; Singer, L.; Kumar, D.; Humar, A.; Pavan, R.; Lipton, J.; Kuruvilla, J.; Schuh, A.; Yee, K.; et al. Aspergillus galactomannan detection in exhaled breath condensate compared to bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 24, 640–645. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.; Lechuga, L.M. Microcantilever-based platforms as biosensing tools. Anal. 2010, 135, 827–836. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Hegner, M. Effect of non-specific species competition from total RNA on the static mode hybridization response of nanomechanical assays of oligonucleotides. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 225501. [CrossRef]

- Nugaeva, N.; Gfeller, K.Y.; Backmann, N.; Lang, H.P.; Düggelin, M.; Hegner, M. Micromechanical cantilever array sensors for selective fungal immobilization and fast growth detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2005, 21, 849–856. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Luo, P.; Sun, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Detection of β-glucans using an amperometric biosensor based on high-affinity interaction between Dectin-1 and β-glucans. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 404, 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Kojic, E.M.; Darouiche, R.O. Candida Infections of Medical Devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 255–267. [CrossRef]

- Nugaeva, N.; Gfeller, K.Y.; Backmann, N.; Düggelin, M.; Lang, H.P.; Güntherodt, H.-J.; Hegner, M. An Antibody-Sensitized Microfabricated Cantilever for the Growth Detection of Aspergillus niger Spores. Microsc. Microanal. 2007, 13, 13–17. [CrossRef]

- Kwasny, D.; Tehrani, S.E.; Almeida, C.; Schjødt, I.; Dimaki, M.; Svendsen, W.E. Direct Detection of Candida albicans with a Membrane Based Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 2214. [CrossRef]

- D'APonte, T.; De Luca, M.; Sakač, N.; Schibeci, M.; Arciello, A.; Roscetto, E.; Catania, M.R.; Iannotti, V.; Velotta, R.; Della Ventura, B. Rapid detection of Candida albicans in urine by an Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)-based biosensor. Sensors Diagn. 2023, 2, 1597–1604. [CrossRef]

- Sá SR, Santos LMC, Pereira EM, Almeida MA, Dias R, de Almeida LC, Silva LLA, Reis RL, Sales MGF. Lectin-based impedimetric biosensor for differentiation of Candida spp. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2020;326:128829.

- Lorenzo-Villegas, D.L.; Gohil, N.V.; Lamo, P.; Gurajala, S.; Bagiu, I.C.; Vulcanescu, D.D.; Horhat, F.G.; Sorop, V.B.; Diaconu, M.; Sorop, M.I.; et al. Innovative Biosensing Approaches for Swift Identification of Candida Species, Intrusive Pathogenic Organisms. Life 2023, 13, 2099. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.K.; Malavia, D.; Johnson, E.M.; Littlechild, J.; Winlove, C.P.; Vollmer, F.; Gow, N.A.R. Biosensors and Diagnostics for Fungal Detection. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 349. [CrossRef]

- Koehler, P.; Bassetti, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chen, S.C.A.; Colombo, A.L.; Hoenigl, M.; Klimko, N.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Oladele, R.O.; Vinh, D.C.; et al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e149–e162. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, R.; Fang, H.; Tang, H.; Xie, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y. Non-invasive detection of Aspergillosis in ventilated patients: Galactomannan analysis in exhaled breath. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 110, 116420. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, J.; Theunissen, K.; Verhoef, G.; Verschakelen, J.; Lagrou, K.; Verbeken, E.; Wilmer, A.; Verhaegen, J.; Boogaerts, M.; Van Eldere, J. Galactomannan and Computed Tomography-Based Preemptive Antifungal Therapy in Neutropenic Patients at High Risk for Invasive Fungal Infection: A Prospective Feasibility Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 1242–1250. [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Tang, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Fan, X. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Detecting Galactomannan in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid for Diagnosing Invasive Aspergillosis. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e43347. [CrossRef]

- Autier, B.; Prattes, J.; White, P.L.; Valerio, M.; Machado, M.; Price, J.; Egger, M.; Gangneux, J.-P.; Hoenigl, M. Aspergillus Lateral Flow Assay with Digital Reader for the Diagnosis of COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA): a Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0168921. [CrossRef]

- Jani, K.; McMillen, T.; Morjaria, S.; Babady, N.E. Performance of the sōna Aspergillus Galactomannan Lateral Flow Assay in a Cancer Patient Population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, JCM0059821. [CrossRef]

- de Heer, K.; Kok, M.G.M.; Fens, N.; Weersink, E.J.M.; Zwinderman, A.H.; van der Schee, M.P.C.; Visser, C.E.; van Oers, M.H.J.; Sterk, P.J. Detection of Airway Colonization by Aspergillus fumigatus by Use of Electronic Nose Technology in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 569–575; Erratum in: J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1926. [CrossRef]

- Diefenderfer, J.; Bean, H.D.; Keppler, E.A.H. New Breath Diagnostics for Fungal Disease. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, M.G.; Brinkman, P.; Escobar, N.; Bos, L.D.; de Heer, K.; Meijer, M.; Janssen, H.-G.; de Cock, H.; AB Wösten, H.; E Visser, C.; et al. Profiling of volatile organic compounds produced by clinical Aspergillus isolates using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Med Mycol. 2017, 56, 253–256. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S.; Pedrero, M.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Antifouling (Bio)materials for Electrochemical (Bio)sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 423. [CrossRef]

- D’agata, R.; Bellassai, N.; Jungbluth, V.; Spoto, G. Recent Advances in Antifouling Materials for Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensing in Clinical Diagnostics and Food Safety. Polymers 2021, 13, 1929. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Ambrosi, A.; Ding, C.; Luo, X. Electrochemical Biosensor with Enhanced Antifouling Capability for COVID-19 Nucleic Acid Detection in Complex Biological Media. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 5963–5971. [CrossRef]

- Kaloumenou, M.; Skotadis, E.; Lagopati, N.; Efstathopoulos, E.; Tsoukalas, D. Breath Analysis: A Promising Tool for Disease Diagnosis—The Role of Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 1238. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.-L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.-G.; Li, Z.-W.; Xia, Y.; Guo, X.-G. Pooled analysis of T2 Candida for rapid diagnosis of candidiasis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).