Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neurobiology of Depression: Beyond Serotonin (5-HT)

2.1. Microglia Activation and Neuroinflammation

2.2. Neurogenesis Impairment and Hippocampal Atrophy in Depressive Pathology

2.3. The Link Between Inflammation, Tryptophan (Trp) Metabolism, and Depressive Symptoms

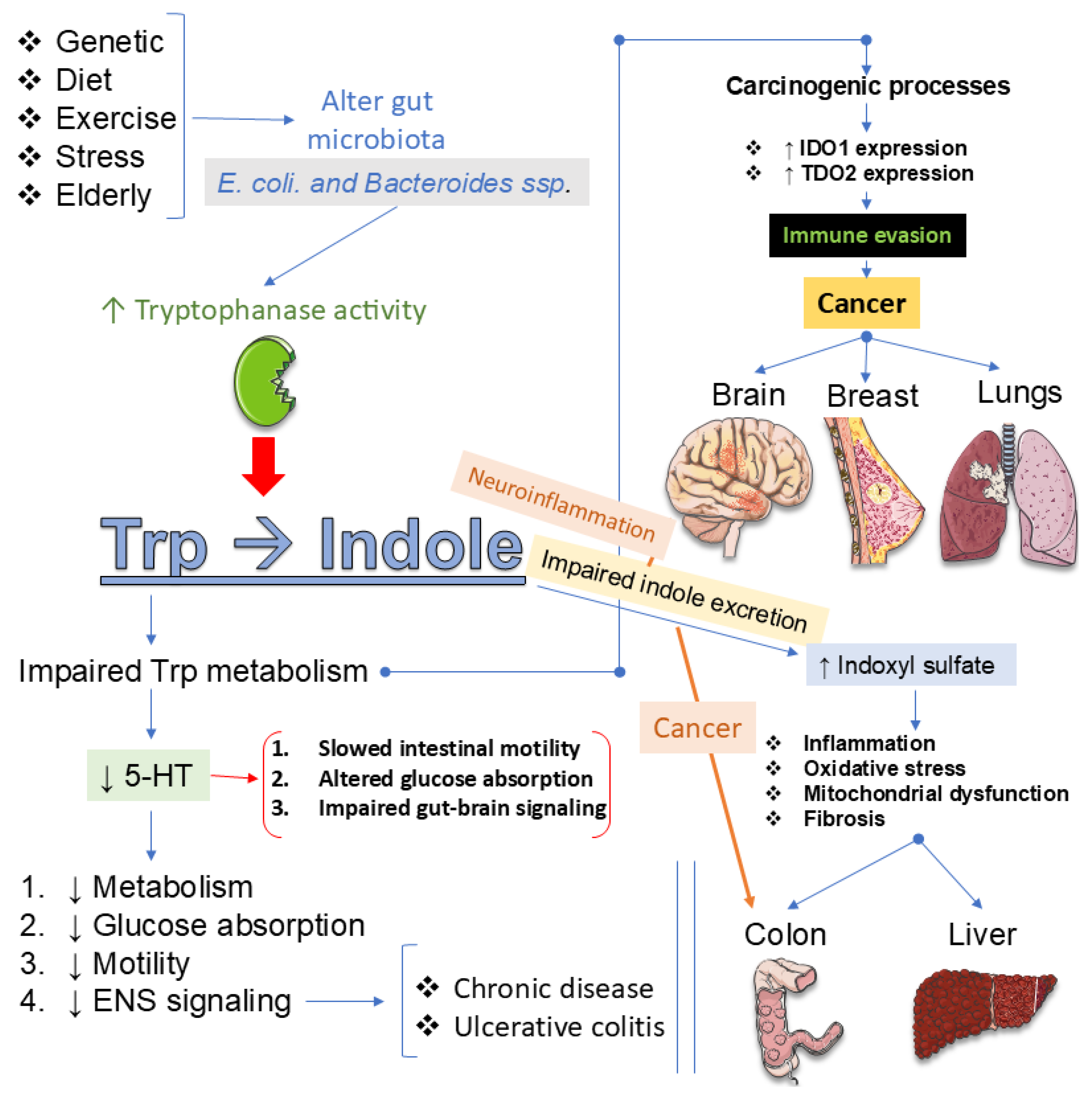

3. Tryptophan (Trp) Metabolism: Central Pathways and Peripheral Influences

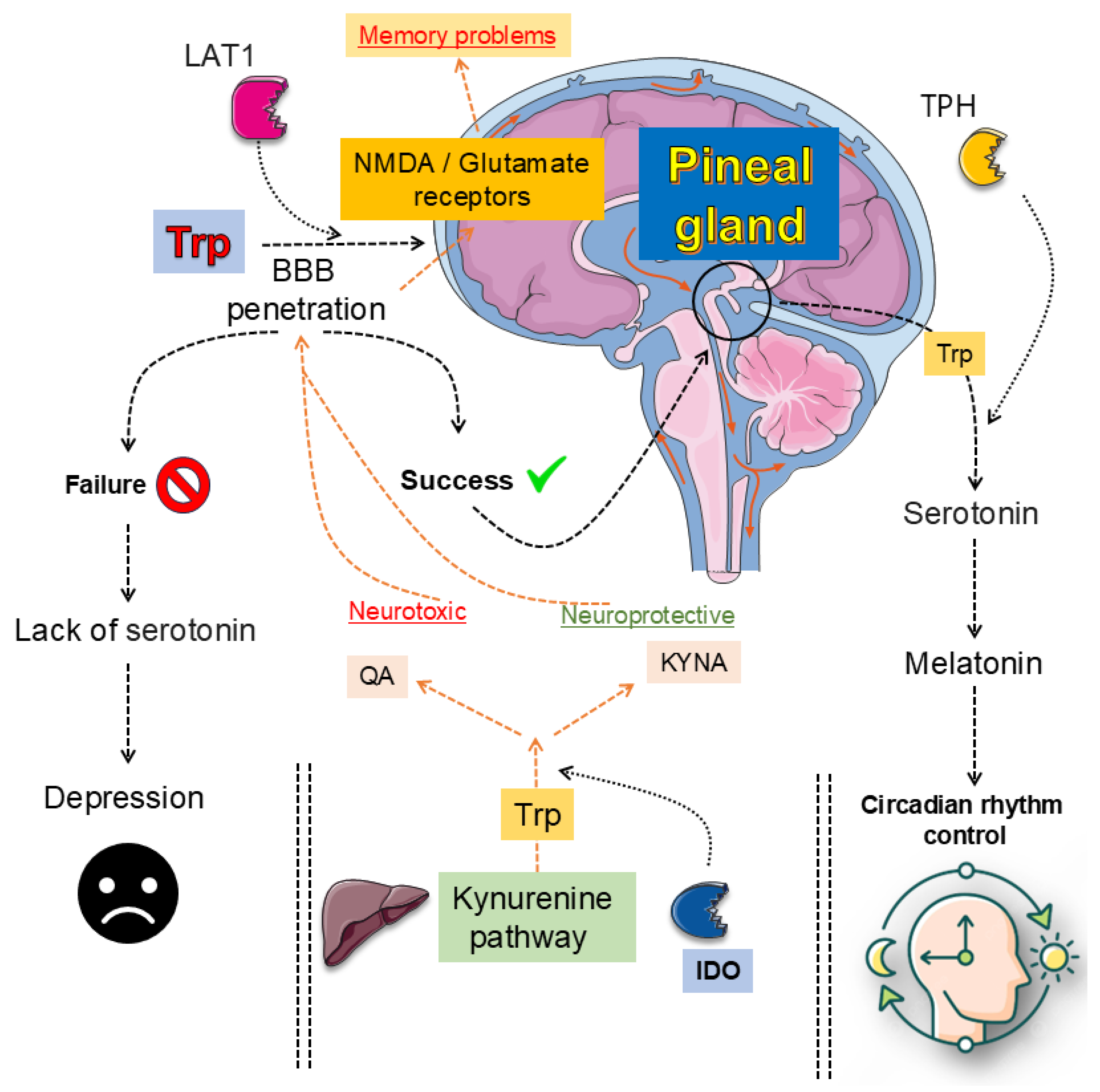

3.1. Serotonin (5HT) and Kynurenine (KYN) Metabolic Pathways: Fundamental Metabolic Routes

3.2. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: Drivers of Kynurenine (KYN) Pathway Activation

3.3. Gut-Brain Axis and Intestinal Microbiota: Peripheral Modulators of Tryptophan (Trp) Metabolism

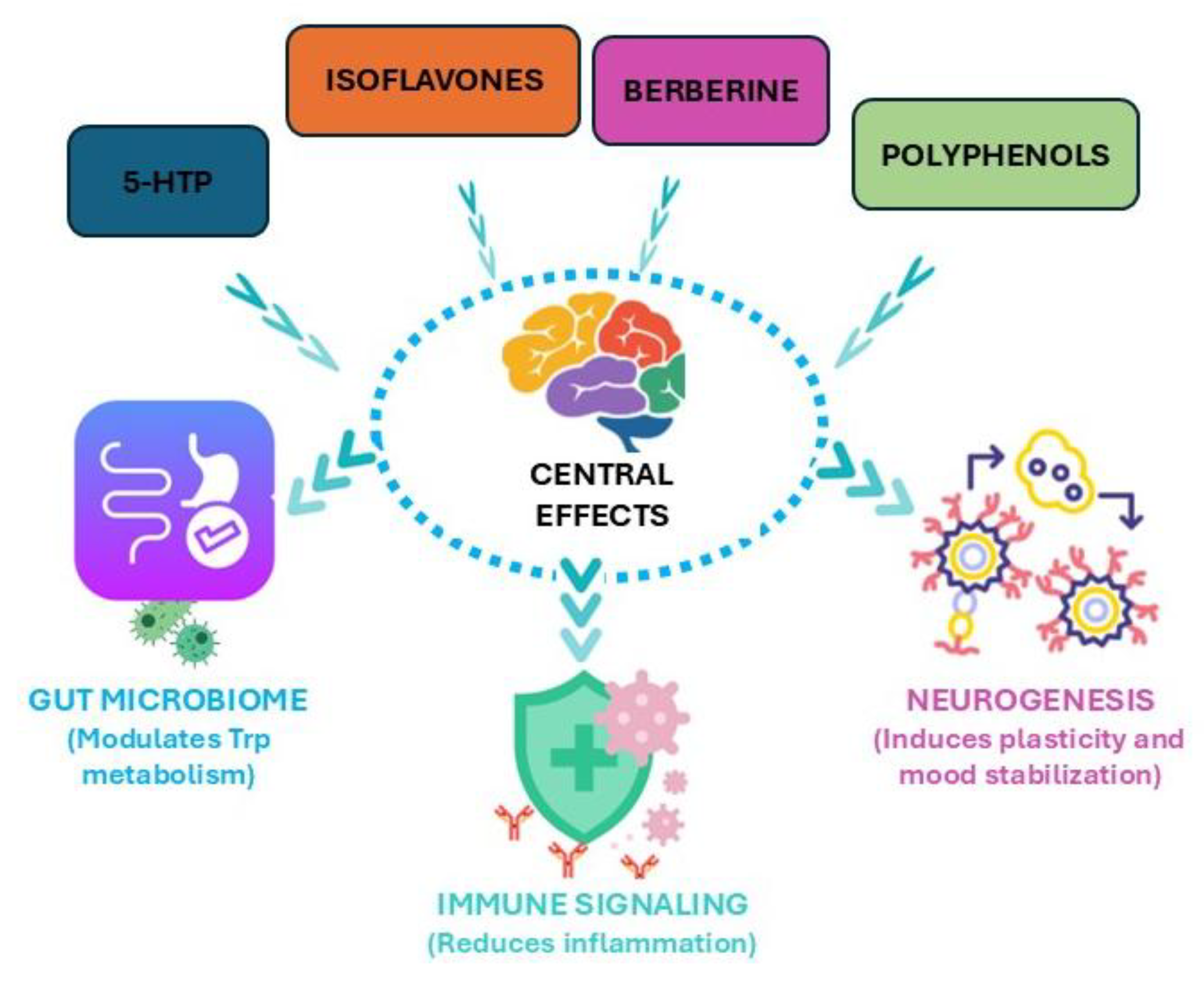

4. Integrative Therapeutic Approaches as Modulators of Tryptophan (Trp) Metabolism with a Focus on Plant-Derived Dietary Strategies

4.1. Clinical Evidence for Plant-Derived Modulators of Tryptophan (Trp) Metabolism

4.2. Specific Tryptophan (Trp)-Rich Phytocompounds and Associated Clinical Outcomes

5. Gaps and Controversies in Current Research

5.1. Identified Gaps in Current Research

5.2. Controversies Regarding Clinical Efficacy and Bioavailability

6. Clinical Translation: From Bench to Bedside

6.1. Practical Considerations for Clinical Application

6.2. Personalized Medicine Approaches

7. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

7.1. Advancing Clinical Evidence through Robust Study Designs

7.2. Combined Pharmacological and Dietary Intervention Strategies

7.3. Leveraging Biotechnological Innovations for Personalized Depression Management

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-HK | 3-hydroxykynurenine |

| 5-HT | serotonin |

| 5-HTP | 5-hydroxytryptophan |

| AhR | aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CDK5 | cyclin-dependent kinase 5 |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

| HDRS | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HPA | hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IDO | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN | interferon |

| IL | interleukin |

| KAT | kynurenine aminotransferases |

| KMO | kynurenine 3-monooxydase |

| KYN | kynurenine |

| KYNA | kynurenic acid |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| QA | quinolinic acid |

| QPRT | quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| TDO | tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Trp | tryptophan |

| TPH | tryptophan hydroxylase |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Filatova, E.V.; Shadrina, M.I.; Slominsky, P.A. Major Depression: One Brain, One Disease, One Set of Intertwined Processes. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Fries, G.R.; Saldana, V.A.; Finnstein, J.; Rein, T. Molecular pathways of major depressive disorder converge on the synapse. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 284-297. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 30. [CrossRef]

- Proudman, D.; Greenberg, P.; Nellesen, D. The Growing Burden of Major Depressive Disorders (MDD): Implications for Researchers and Policy Makers. Pharmacoeconomics 2021, 39, 619-625. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.E.; Fournier, A.A.; Sisitsky, T.; Simes, M.; Berman, R.; Koenigsberg, S.H.; Kessler, R.C. The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics 2021, 39, 653-665. [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, L.; Gui, S.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Ran, Y.; et al. An integrated meta-analysis of peripheral blood metabolites and biological functions in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4265-4276. [CrossRef]

- Kouba, B.R.; de Araujo Borba, L.; Borges de Souza, P.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Role of Inflammatory Mechanisms in Major Depressive Disorder: From Etiology to Potential Pharmacological Targets. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Athira, K.V.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Samudrala, P.K.; Naidu, V.G.M.; Lahkar, M.; Chakravarty, S. An Overview of the Heterogeneity of Major Depressive Disorder: Current Knowledge and Future Prospective. Curr Neuropharmacol 2020, 18, 168-187. [CrossRef]

- Ilavská, L.; Morvová, M., Jr.; Paduchová, Z.; Muchová, J.; Garaiova, I.; Ďuračková, Z.; Šikurová, L.; Trebatická, J. The kynurenine and serotonin pathway, neopterin and biopterin in depressed children and adolescents: an impact of omega-3 fatty acids, and association with markers related to depressive disorder. A randomized, blinded, prospective study. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1347178. [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.S.; Vale, N. Tryptophan Metabolism in Depression: A Narrative Review with a Focus on Serotonin and Kynurenine Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Yuan, M.; Guo, Y.; Ma, L.; Lin, D.; et al. In Situ Recovery of Serotonin Synthesis by a Tryptophan Hydroxylase-Like Nanozyme for the Treatment of Depression. J Am Chem Soc 2025, 147, 9111-9121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, J.; Zhu, P.; Xie, H.; Lu, L.; Bai, W.; Pan, W.; Shi, R.; Ye, J.; Xia, B.; et al. Tryptophan-rich diet ameliorates chronic unpredictable mild stress induced depression- and anxiety-like behavior in mice: The potential involvement of gut-brain axis. Food Res Int 2022, 157, 111289. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Le, A.; Hong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Zang, W.; Jiang, C.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolism in Central Nervous System Diseases: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Aging Dis 2023, 14, 858-878. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Gao, C.S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.P.; Pan, L.B.; Yu, H.; He, C.Y.; Luo, H.B.; Zhao, Z.X.; et al. Morinda officinalis oligosaccharides increase serotonin in the brain and ameliorate depression via promoting 5-hydroxytryptophan production in the gut microbiota. Acta Pharm Sin B 2022, 12, 3298-3312. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Godoy, A.C.; Frota, F.F.; Araújo, L.P.; Valenti, V.E.; Pereira, E.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Galhardi, C.M.; Caracio, F.C.; Haber, R.S.A.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Natural Antidepressants: Balancing Fire with Flora. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, P.J. SSRIs in the Treatment of Depression: A Pharmacological CUL-DE-SAC? Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2024, 66, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, F.C.; de Melo, D.O.; Fráguas, R.; Leite-Santos, N.C.; Mantovani da Silva, R.A.; Ribeiro, E. Pharmacological treatment of depression: A systematic review comparing clinical practice guideline recommendations. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231700. [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz, K.; Sowa-Kućma, M. The treatment of depression - searching for new ideas. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 988648. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, D.; Chrobak, A.A.; Krupa, A.J.; Gorostowicz, A.; Gerlich, A.; Juryk, A.; Siwek, M. TED-trazodone effectiveness in depression: a naturalistic study of the effeciveness of trazodone in extended release formulation compared to SSRIs in patients with a major depressive disorder. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1296639. [CrossRef]

- Srifuengfung, M.; Pennington, B.R.T.; Lenze, E.J. Optimizing treatment for older adults with depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2023, 13, 20451253231212327. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D.; Liu, A.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, W. The pharmacological mechanism of chaihu-jia-longgu-muli-tang for treating depression: integrated meta-analysis and network pharmacology analysis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1257617. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Yu, C. The efficacy and safety of St. John's wort extract in depression therapy compared to SSRIs in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv Clin Exp Med 2023, 32, 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Huang, Y. Electroacupuncture as a rapid-onset and safer complementary therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1012606. [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Jafarabady, K.; Seighali, N.; Mohammadi, I.; Rajai Firouz Abadi, S.; Abhari, F.S.; Bakhtiyari, M. Effect of Saffron Versus Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) in Treatment of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr Rev 2025, 83, e751-e761. [CrossRef]

- Zhichao, H.; Ching, L.W.; Huijuan, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhiyu, W.; Weiyang, H.; Zhaoxiang, B.; Linda, Z.L.D. A network meta-analysis on the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in treating patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10384. [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, K.; David, D.; Franko, M.; Toledano, R.; Fidelman, S.; Tenenbaum, Y.S.; Blonder, M.; Armoza-Eilat, S.; Shamir, A.; Rehavi, M.; et al. Anxiolytic and antidepressants' effect of Crataegus pinnatifida (Shan Zha): biochemical mechanisms. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 208. [CrossRef]

- Di Sotto, A.; Vitalone, A.; Di Giacomo, S. Plant-Derived Nutraceuticals and Immune System Modulation: An Evidence-Based Overview. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vrânceanu, M.; Galimberti, D.; Banc, R.; Dragoş, O.; Cozma-Petruţ, A.; Hegheş, S.C.; Voştinaru, O.; Cuciureanu, M.; Stroia, C.M.; Miere, D.; et al. The Anticancer Potential of Plant-Derived Nutraceuticals via the Modulation of Gene Expression. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.X.; Lan, W.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Natural saponins and macrophage polarization: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic perspectives in disease management. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1584035. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Song, Y.; Ai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhu, G.; Yang, M.; Su, D. Pulsatilla chinensis saponins ameliorated murine depression by inhibiting intestinal inflammation mediated IDO1 overexpression and rebalancing tryptophan metabolism. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154852. [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, H.; Parveen, A.; Kim, S.Y. Neuroprotective Natural Products' Regulatory Effects on Depression via Gut-Brain Axis Targeting Tryptophan. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Azhar, A.; Tikmani, P.; Rafique, H.; Khan, A.; Mesiya, H.; Saeed, H. A randomized clinical trial to test efficacy of chamomile and saffron for neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory responses in depressive patients. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10774. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Li, C.X.; Zhang, R.B.; Shen, Y.; Xu, X.J.; Yu, Q.M. A review of the pharmacological action and mechanism of natural plant polysaccharides in depression. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1348019. [CrossRef]

- Tartt, A.N.; Mariani, M.B.; Hen, R.; Mann, J.J.; Boldrini, M. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2689-2699. [CrossRef]

- Colucci-D'Amato, L.; Speranza, L.; Volpicelli, F. Neurotrophic Factor BDNF, Physiological Functions and Therapeutic Potential in Depression, Neurodegeneration and Brain Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Corticosterone-induced Hippocampal 5-HT Responses were Muted in Depressive-like State. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021, 12, 845-856. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Peng, W.H.; Kan, H.W.; Wu, C.C.; Wang, D.W.; Ho, Y.C. Neurobiology of Depression: Chronic Stress Alters the Glutamatergic System in the Brain-Focusing on AMPA Receptor. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- He, J.G.; Zhou, H.Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.G. Dysfunction of Glutamatergic Synaptic Transmission in Depression: Focus on AMPA Receptor Trafficking. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci 2023, 3, 187-196. [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff, J.; Cooper, R.E.; Stockmann, T.; Amendola, S.; Hengartner, M.P.; Horowitz, M.A. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3243-3256. [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.S.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. Oxidative Stress in Depression: The Link with the Stress Response, Neuroinflammation, Serotonin, Neurogenesis and Synaptic Plasticity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cao, K.; Lin, H.; Cui, S.; Shen, C.; Wen, W.; Mo, H.; Dong, Z.; Bai, S.; Yang, L.; et al. Early-Life Stress Induces Depression-Like Behavior and Synaptic-Plasticity Changes in a Maternal Separation Rat Model: Gender Difference and Metabolomics Study. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 102. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, R.; Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T. Down-regulation of MST1 in hippocampus protects against stress-induced depression-like behaviours and synaptic plasticity impairments. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 94, 196-209. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, L.R.; Phillips, A.G. Neuroplasticity as a convergent mechanism of ketamine and classical psychedelics. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2021, 42, 929-942. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Gould, T.D. Targeting metaplasticity mechanisms to promote sustained antidepressant actions. Mol Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1114-1127. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. Dualistic Dynamics in Neuropsychiatry: From Monoaminergic Modulators to Multiscale Biomarker Maps. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, W.; Ge, T.; Wang, Y.; Cui, R. Stress induced microglial activation contributes to depression. Pharmacol Res 2022, 179, 106145. [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, S.C.; Bollinger, J.L.; Wohleb, E.S. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 258. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ren, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, J. Microglia in depression: an overview of microglia in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 132. [CrossRef]

- Kokkosis, A.G.; Madeira, M.M.; Hage, Z.; Valais, K.; Koliatsis, D.; Resutov, E.; Tsirka, S.E. Chronic psychosocial stress triggers microglial-/macrophage-induced inflammatory responses leading to neuronal dysfunction and depressive-related behavior. Glia 2024, 72, 111-132. [CrossRef]

- Sugama, S.; Kakinuma, Y. Stress and brain immunity: Microglial homeostasis through hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis and sympathetic nervous system. Brain Behav Immun Health 2020, 7, 100111. [CrossRef]

- Picard, K.; Bisht, K.; Poggini, S.; Garofalo, S.; Golia, M.T.; Basilico, B.; Abdallah, F.; Ciano Albanese, N.; Amrein, I.; Vernoux, N.; et al. Microglial-glucocorticoid receptor depletion alters the response of hippocampal microglia and neurons in a chronic unpredictable mild stress paradigm in female mice. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 97, 423-439. [CrossRef]

- Fornari Laurindo, L.; Aparecido Dias, J.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; Torres Pomini, K.; Machado Galhardi, C.; Rucco Penteado Detregiachi, C.; Santos de Argollo Haber, L.; Donizeti Roque, D.; Dib Bechara, M.; Vialogo Marques de Castro, M.; et al. Immunological dimensions of neuroinflammation and microglial activation: exploring innovative immunomodulatory approaches to mitigate neuroinflammatory progression. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1305933. [CrossRef]

- Asveda, T.; Talwar, P.; Ravanan, P. Exploring microglia and their phenomenal concatenation of stress responses in neurodegenerative disorders. Life Sci 2023, 328, 121920. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K. Microglia mediated neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: A review on the cell signaling pathways involved in microglial activation. J Neuroimmunol 2023, 383, 578180. [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.L.; Short, A.K.; Othy, S.; Kooiker, C.L.; Shao, M.; Gunn, B.G.; Beck, J.; Bai, X.; Law, S.M.; Savage, J.C.; et al. Early stress-induced impaired microglial pruning of excitatory synapses on immature CRH-expressing neurons provokes aberrant adult stress responses. Cell Rep 2022, 38, 110600. [CrossRef]

- Reemst, K.; Kracht, L.; Kotah, J.M.; Rahimian, R.; van Irsen, A.A.; Congrains Sotomayor, G.; Verboon, L.N.; Brouwer, N.; Simard, S.; Turecki, G. Early-life stress lastingly impacts microglial transcriptome and function under basal and immune-challenged conditions. Translational psychiatry 2022, 12, 507.

- Smail, M.A.; Lenz, K.M. Developmental functions of microglia: Impact of psychosocial and physiological early life stress. Neuropharmacology 2024, 258, 110084. [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Liang, L.F.; Shi, T.L.; Shen, Z.Q.; Yin, S.Y.; Zhang, J.R.; Li, W.; Mi, W.L.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.Q.; et al. Microglia-Derived Interleukin-6 Triggers Astrocyte Apoptosis in the Hippocampus and Mediates Depression-Like Behavior. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2412556. [CrossRef]

- Klawonn, A.M.; Fritz, M.; Castany, S.; Pignatelli, M.; Canal, C.; Similä, F.; Tejeda, H.A.; Levinsson, J.; Jaarola, M.; Jakobsson, J.; et al. Microglial activation elicits a negative affective state through prostaglandin-mediated modulation of striatal neurons. Immunity 2021, 54, 225-234.e226. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Wu, H.R.; Zhang, S.S.; Xiao, H.L.; Yu, J.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Liu, Q. Catalpol ameliorates depressive-like behaviors in CUMS mice via oxidative stress-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome and neuroinflammation. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 353. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Y.; Guo, Y.X.; Lian, W.W.; Yan, Y.; Ma, B.Z.; Cheng, Y.C.; Xu, J.K.; He, J.; Zhang, W.K. The NLRP3 inflammasome in depression: Potential mechanisms and therapies. Pharmacol Res 2023, 187, 106625. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hauenstein, A.V. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Mechanism of action, role in disease and therapies. Mol Aspects Med 2020, 76, 100889. [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Ferrari, C.; Turner, L.; Mariani, N.; Enache, D.; Hastings, C.; Kose, M.; Lombardo, G.; McLaughlin, A.P.; Nettis, M.A.; et al. Whole-blood expression of inflammasome- and glucocorticoid-related mRNAs correctly separates treatment-resistant depressed patients from drug-free and responsive patients in the BIODEP study. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 232. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, F.; Ge, J.; Xia, Q. Serum cytokines-based biomarkers in the diagnosis and monitoring of therapeutic response in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 118, 110108. [CrossRef]

- Bodnár, K.; Hermán, L.; Zsigmond, R.; Réthelyi, J. Investigation of cytokine imbalance in schizophrenia, assessment of the possible role of serum cytokine levels in predicting treatment response, prognosis and psychotic relapses. European Psychiatry 2024, 67, S685-S685.

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tu, D.; Wilson, B.; Song, S.; Feng, J.; Hong, J.S.; et al. A novel role of NLRP3-generated IL-1β in the acute-chronic transition of peripheral lipopolysaccharide-elicited neuroinflammation: implications for sepsis-associated neurodegeneration. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 64. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.A.; Hottz, E.D.; Dos Santos Ornellas, D.; Adesse, D.; de Azevedo, C.T.; d'Avila, J.C.; Zaverucha-do-Valle, C.; Maron-Gutierrez, T.; Barbosa, H.S.; Bozza, P.T.; et al. Microglial NLRP3 Inflammasome Induces Excitatory Synaptic Loss Through IL-1β-Enriched Microvesicle Release: Implications for Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 481-494. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2025, 22, 341-355. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wu, C.; Jia, L.; Fang, Z.; Lu, J.; Mou, T.; Hu, S.; He, H.; Huang, M.; Xu, Y. Increased plasma levels of IL-6 are associated with striatal structural atrophy in major depressive disorder patients with anhedonia. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1016735. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.F.P.; Tirado, B.; Seider, N.A.; Triplett, R.L.; Lean, R.E.; Neil, J.J.; Miller, J.P.; Tillman, R.; Smyser, T.A.; Barch, D.M.; et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal disadvantage-related inflammatory biomarkers: associations with neonatal white matter microstructure. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 72. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Sohn, H.; Kwon, M.S.; Kim, B. White Matter Alterations Associated with Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2021, 19, 449-458. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zheng, R.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lei, N.; Xiong, L.; Guo, P.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depression-like model in mice: meta-analysis and systematic evaluation. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1181973. [CrossRef]

- Lasselin, J.; Schedlowski, M.; Karshikoff, B.; Engler, H.; Lekander, M.; Konsman, J.P. Comparison of bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behavior in rodents and humans: Relevance for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 115, 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Pan, Y.W.; Wang, S.Q.; Li, X.Z.; Huang, F.; Ma, S.P. Saikosaponin-d attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behaviors via inhibiting microglia activation and neuroinflammation. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 80, 106181. [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, V.S.; Chaves Filho, A.J.M.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Jucá, P.M.; Soares, M.V.R.; Barroso, P.N.; Cristino, L.M.F.; Jiang, W.; Teixeira, A.L.; de Lucena, D.F.; et al. Antidepressants of different classes cause distinct behavioral and brain pro- and anti-inflammatory changes in mice submitted to an inflammatory model of depression. J Affect Disord 2020, 268, 188-200. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.S.; Zou, J.J.; Meng, L.; Chen, H.M.; Hong, Z.Q.; Liu, X.F.; Farooq, U.; Chen, M.X.; Lin, Z.R.; Zhou, W.; et al. Ultrasound Stimulation of Prefrontal Cortex Improves Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depressive-Like Behaviors in Mice. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 864481. [CrossRef]

- Kappelmann, N.; Lewis, G.; Dantzer, R.; Jones, P.B.; Khandaker, G.M. Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 335-343. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X.L.; Shi, H.; Meng, L.Q.; Quan, H.F.; Yan, L.; Yang, H.F.; Peng, X.D. Betaine Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Hyperactivation and Regulates Microglial M1/M2 Phenotypic Differentiation, Thereby Attenuating Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depression-Like Behavior. J Immunol Res 2022, 2022, 9313436. [CrossRef]

- Planchez, B.; Lagunas, N.; Le Guisquet, A.M.; Legrand, M.; Surget, A.; Hen, R.; Belzung, C. Increasing Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Promotes Resilience in a Mouse Model of Depression. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.L.; Zhou, M.; Jhaveri, D.J. Dissecting the role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis towards resilience versus susceptibility to stress-related mood disorders. NPJ Sci Learn 2022, 7, 16. [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wan, C.; Yuan, N.; Chen, J.; Hao, W.; Mo, X.; Guo, X.; et al. Roles of microglia in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression and their therapeutics. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1193053. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J.; Wang, C.; Ding, H.; Wen, S.; Yang, F.; Jiao, R.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; et al. Neuron stem cell NLRP6 sustains hippocampal neurogenesis to resist stress-induced depression. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2017-2038. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Deng, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, Z.L.; Long, L.H.; Wu, P.F.; He, J.G.; Chen, H.S.; Yue, Z.; Lu, J.H.; et al. Cell type-specific NRBF2 orchestrates autophagic flux and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in chronic stress-induced depression. Cell Discov 2023, 9, 90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, F.; Zhai, M.; He, M.; Hu, Y.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, C. Hyperactive neuronal autophagy depletes BDNF and impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis in a corticosterone-induced mouse model of depression. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1059.

- Du Preez, A.; Onorato, D.; Eiben, I.; Musaelyan, K.; Egeland, M.; Zunszain, P.A.; Fernandes, C.; Thuret, S.; Pariante, C.M. Chronic stress followed by social isolation promotes depressive-like behaviour, alters microglial and astrocyte biology and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 91, 24-47. [CrossRef]

- Parul; Mishra, A.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Tiwari, V.; Chaturvedi, S.; Wahajuddin, M.; Palit, G.; Shukla, S. Chronic unpredictable stress negatively regulates hippocampal neurogenesis and promote anxious depression-like behavior via upregulating apoptosis and inflammatory signals in adult rats. Brain Res Bull 2021, 172, 164-179. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Rong, P.; Zhang, L.; He, H.; Zhou, T.; Fan, Y.; Mo, L.; Zhao, Q.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; et al. IL4-driven microglia modulate stress resilience through BDNF-dependent neurogenesis. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, M.; Sun, N.; Wang, H.; Fan, H. Melatonin attenuates chronic stress-induced hippocampal inflammatory response and apoptosis by inhibiting ADAM17/TNF-α axis. Food Chem Toxicol 2022, 169, 113441. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Fan, C.; Zhang, P.; Shen, J.; Yu, S.Y. Ginsenoside-Rg1 Rescues Stress-Induced Depression-Like Behaviors via Suppression of Oxidative Stress and Neural Inflammation in Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 2325391. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Ren, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Duan, W.; et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 Reduced Microglial Activation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Alleviate Depression-Like Behaviour Via the GAS5/EZH2/SOCS3/NRF2 Axis. Mol Neurobiol 2022, 59, 2855-2873. [CrossRef]

- Amanollahi, M.; Jameie, M.; Heidari, A.; Rezaei, N. The Dialogue Between Neuroinflammation and Adult Neurogenesis: Mechanisms Involved and Alterations in Neurological Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 923-959. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, H.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, T.; He, H.; Yi, S.; Zhang, L.; Mo, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; et al. Priming of microglia with IFN-γ impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis and leads to depression-like behaviors and cognitive defects. Glia 2020, 68, 2674-2692. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, B. Aerobic Exercise Restores Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Cognitive Function by Decreasing Microglia Inflammasome Formation Through Irisin/NLRP3 Pathway. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70061. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Lan, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, S. Ginsenoside-Rg1 synergized with voluntary running exercise protects against glial activation and dysregulation of neuronal plasticity in depression. Food Funct 2023, 14, 7222-7239. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B.; et al. Vascular Impairment, Muscle Atrophy, and Cognitive Decline: Critical Age-Related Conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liloia, D.; Zamfira, D.A.; Tanaka, M.; Manuello, J.; Crocetta, A.; Keller, R.; Cozzolino, M.; Duca, S.; Cauda, F.; Costa, T. Disentangling the role of gray matter volume and concentration in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic investigation of 25 years of voxel-based morphometry research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 164, 105791. [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S. Neuroimmune crosstalk in chronic neuroinflammation: microglial interactions and immune modulation. Front Cell Neurosci 2025, 19, 1575022. [CrossRef]

- Navabi, S.P.; Badreh, F.; Khombi Shooshtari, M.; Hajipour, S.; Moradi Vastegani, S.; Khoshnam, S.E. Microglia-induced neuroinflammation in hippocampal neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35869. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener 2020, 9, 42. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Molina, P.; Almolda, B.; Giménez-Llort, L.; González, B.; Castellano, B. Chronic IL-10 overproduction disrupts microglia-neuron dialogue similar to aging, resulting in impaired hippocampal neurogenesis and spatial memory. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 101, 231-245. [CrossRef]

- Izzy, S.; Yahya, T.; Albastaki, O.; Abou-El-Hassan, H.; Aronchik, M.; Cao, T.; De Oliveira, M.G.; Lu, K.J.; Moreira, T.G.; da Silva, P.; et al. Nasal anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody ameliorates traumatic brain injury, enhances microglial phagocytosis and reduces neuroinflammation via IL-10-dependent T(reg)-microglia crosstalk. Nat Neurosci 2025, 28, 499-516. [CrossRef]

- Witcher, K.G.; Bray, C.E.; Chunchai, T.; Zhao, F.; O'Neil, S.M.; Gordillo, A.J.; Campbell, W.A.; McKim, D.B.; Liu, X.; Dziabis, J.E.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Causes Chronic Cortical Inflammation and Neuronal Dysfunction Mediated by Microglia. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 1597-1616. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Gu, Y. Evaluation of serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-a cognitive function, and sleep quality in elderly patients with major depressive disorder and somatic symptoms. J Med Biochem 2025, 44, 568-575. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Guo, A.; Guan, K.; Chen, C.; Xu, S.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Z. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates depression-like behaviour and cognitive deficits in chronic ethanol exposure mice by down-regulating systemic inflammatory factors. Addict Biol 2024, 29, e13445. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Yao, W.; Hashimoto, K. Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)-TrkB Signaling in Inflammation-related Depression and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016, 14, 721-731. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.; Rossetti, A.C.; Racagni, G.; Gass, P.; Riva, M.A.; Molteni, R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a bridge between inflammation and neuroplasticity. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 430. [CrossRef]

- Carniel, B.P.; da Rocha, N.S. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and inflammatory markers: Perspectives for the management of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021, 108, 110151. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, C.; Su, D.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, W.; You, Z.; Zhou, T. Akebia saponin D protects hippocampal neurogenesis from microglia-mediated inflammation and ameliorates depressive-like behaviors and cognitive impairment in mice through the PI3K-Akt pathway. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 927419. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Yun, Y.; Ma, T.; An, H.; Fan, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F. Multiomics analysis reveals aberrant tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism and immunity linked gut microbiota with cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2025, 373, 273-283. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; Jasmin Santos German, I.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; da Silva, R.M.S.; Gallerani Caglioni, L.; Nunes Junqueira de Moraes, V.B.F.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Beluce, M.E.; et al. AdipoRon's Impact on Alzheimer's Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A. Role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) and kynurenine pathway in the regulation of the aging process. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 75, 101573. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tóth, F.; Polyák, H.; Szabó, Á.; Mándi, Y.; Vécsei, L. Immune Influencers in Action: Metabolites and Enzymes of the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, S.; Bano, S.; Badawy, A.A. Inflammation and serotonin deficiency in major depressive disorder: molecular docking of antidepressant and anti-inflammatory drugs to tryptophan and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases. Biosci Rep 2022, 42. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Paramanik, V. Role of Probiotics in Depression: Connecting Dots of Gut-Brain-Axis Through Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenal Axis and Tryptophan/Kynurenic Pathway involving Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase. Mol Neurobiol 2025, 62, 7230-7241. [CrossRef]

- Sublette, M.E.; Postolache, T.T. Neuroinflammation and depression: the role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) as a molecular pathway. Psychosom Med 2012, 74, 668-672. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S. From Biomarkers to Behavior: Mapping the Neuroimmune Web of Pain, Mood, and Memory. 2025, 13, 2226.

- Stone, T.W.; Williams, R.O. Tryptophan metabolism as a 'reflex' feature of neuroimmune communication: Sensor and effector functions for the indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase kynurenine pathway. J Neurochem 2024, 168, 3333-3357. [CrossRef]

- Juhász, L.; Spisák, K.; Szolnoki, B.Z.; Nászai, A.; Szabó, Á.; Rutai, A.; Tallósy, S.P.; Szabó, A.; Toldi, J.; Tanaka, M.; et al. The Power Struggle: Kynurenine Pathway Enzyme Knockouts and Brain Mitochondrial Respiration. J Neurochem 2025, 169, e70075. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Á.; Galla, Z.; Spekker, E.; Szűcs, M.; Martos, D.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Toldi, J.; et al. Oxidative and Excitatory Neurotoxic Stresses in CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Kynurenine Aminotransferase Knockout Mice: A Novel Model for Despair-Based Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 25706. [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.; Murray, P.J. Tryptophan and indole metabolism in immune regulation. Curr Opin Immunol 2021, 70, 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Á.; Galla, Z.; Spekker, E.; Martos, D.; Szűcs, M.; Fejes-Szabó, A.; Fehér, Á.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; et al. Behavioral Balance in Tryptophan Turmoil: Regional Metabolic Rewiring in Kynurenine Aminotransferase II Knockout Mice. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Rodríguez, A.; Reyes-Long, S.; Roldan-Valadez, E.; González-Torres, M.; Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Bandala, C.; Avila-Luna, A.; Bueno-Nava, A.; Cabrera-Ruiz, E.; Sanchez-Aparicio, P.; et al. Association of the Serotonin and Kynurenine Pathways as Possible Therapeutic Targets to Modulate Pain in Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.; Macedo, E.C.T.; Suchting, R.; de Dios, C.; Cuellar Leal, V.A.; Soares, J.C.; Dantzer, R.; Teixeira, A.L.; Selvaraj, S. Effect of immune activation on the kynurenine pathway and depression symptoms - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020, 118, 514-523. [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A.F.; Supasitthumrong, T.; Tunvirachaisakul, C.; Algon, A.A.A.; Al-Hakeim, H.K.; Maes, M. The tryptophan catabolite or kynurenine pathway in COVID-19 and critical COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2022, 22, 615. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X. Dietary polyphenols: regulate the advanced glycation end products-RAGE axis and the microbiota-gut-brain axis to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 9816-9842. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Cady, N.M.; Lehman, P.; Peterson, S.R.; Shahi, S.K.; Rashid, F.; Giri, S.; Mangalam, A.K. Dietary Isoflavones Alter Gut Microbiota and Lipopolysaccharide Biosynthesis to Reduce Inflammation. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2127446. [CrossRef]

- Winiarska-Mieczan, A.; Kwiecień, M.; Jachimowicz-Rogowska, K.; Donaldson, J.; Tomaszewska, E.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Neuroprotective Effects of Polyphenols-Polyphenols as an Element of Diet Therapy in Depressive Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Tian, E.; Sharma, G.; Dai, C. Neuroprotective Properties of Berberine: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L. Supplementation with soy isoflavones alleviates depression-like behaviour via reshaping the gut microbiota structure. Food Funct 2021, 12, 4995-5006. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Kumar, S.; Roy Sarkar, S.; Halder, R.; Kumari, R.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, B. Dietary polyphenols represent a phytotherapeutic alternative for gut dysbiosis associated neurodegeneration: A systematic review. J Nutr Biochem 2024, 129, 109622. [CrossRef]

- Tayab, M.A.; Islam, M.N.; Chowdhury, K.A.A.; Tasnim, F.M. Targeting neuroinflammation by polyphenols: A promising therapeutic approach against inflammation-associated depression. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 147, 112668. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, F.; Fakhri, S.; Khan, H. Targeting apoptosis and autophagy following spinal cord injury: Therapeutic approaches to polyphenols and candidate phytochemicals. Pharmacol Res 2020, 160, 105069. [CrossRef]

- Grifka-Walk, H.M.; Jenkins, B.R.; Kominsky, D.J. Amino Acid Trp: The Far Out Impacts of Host and Commensal Tryptophan Metabolism. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 653208. [CrossRef]

- Comai, S.; Bertazzo, A.; Brughera, M.; Crotti, S. Tryptophan in health and disease. Adv Clin Chem 2020, 95, 165-218. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, R. Involvement of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in chronic restraint stress: disturbances of the kynurenine metabolic pathway in both the gut and brain. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Tutakhail, A.; Boulet, L.; Khabil, S.; Nazari, Q.A.; Hamid, H.; Coudoré, F. Neuropathology of kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism. Current pharmacology reports 2020, 6, 8-23.

- Höglund, E.; Øverli, Ø.; Winberg, S. Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways and Brain Serotonergic Activity: A Comparative Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 158. [CrossRef]

- Fujigaki, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Saito, K. L-Tryptophan-kynurenine pathway enzymes are therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric diseases: Focus on cell type differences. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 264-274. [CrossRef]

- Messaoud, A.; Mensi, R.; Douki, W.; Neffati, F.; Najjar, M.F.; Gobbi, G.; Valtorta, F.; Gaha, L.; Comai, S. Reduced peripheral availability of tryptophan and increased activation of the kynurenine pathway and cortisol correlate with major depression and suicide. World J Biol Psychiatry 2019, 20, 703-711. [CrossRef]

- Chivite, M.; Leal, E.; Míguez, J.M.; Cerdá-Reverter, J.M. Distribution of two isoforms of tryptophan hydroxylase in the brain of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). An in situ hybridization study. Brain Struct Funct 2021, 226, 2265-2278. [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E. 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP): Natural Occurrence, Analysis, Biosynthesis, Biotechnology, Physiology and Toxicology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 22. [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Gu, X.; Shi, Q.; Su, Y.; Chu, Q.; Yuan, X.; Bao, Z.; Lu, J.; et al. Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab 2023, 35, 1304-1326. [CrossRef]

- Zakrocka, I.; Urbańska, E.M.; Załuska, W.; Kronbichler, A. Kynurenine Pathway after Kidney Transplantation: Friend or Foe? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 9940.

- Perez-Castro, L.; Garcia, R.; Venkateswaran, N.; Barnes, S.; Conacci-Sorrell, M. Tryptophan and its metabolites in normal physiology and cancer etiology. The FEBS journal 2023, 290, 7-27.

- Tanaka, M.; Bohár, Z.; Vécsei, L. Are Kynurenines Accomplices or Principal Villains in Dementia? Maintenance of Kynurenine Metabolism. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Vakili, K.; Yaghoobpoor, S.; Tavasol, A.; Jazi, K.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Klegeris, A.; McElhinney, A.; Mafi, Z.; Hajiesmaeili, M.; et al. Dynamic changes in kynurenine pathway metabolites in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1013784. [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Chen, Y.; Ju, Y.; Ma, M.; Qin, Y.; Bi, Y.; Liao, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder under different disease states: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2023, 339, 624-632. [CrossRef]

- Kozieł, K.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenine Pathway in Diabetes Mellitus-Novel Pharmacological Target? Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining Roles: A Paradigm Shift in Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism for Innovative Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Skorobogatov, K.; De Picker, L.; Verkerk, R.; Coppens, V.; Leboyer, M.; Müller, N.; Morrens, M. Brain Versus Blood: A Systematic Review on the Concordance Between Peripheral and Central Kynurenine Pathway Measures in Psychiatric Disorders. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 716980. [CrossRef]

- Pocivavsek, A.; Schwarcz, R.; Erhardt, S. Neuroactive Kynurenines as Pharmacological Targets: New Experimental Tools and Exciting Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmacol Rev 2024, 76, 978-1008. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sakuma, M.; Deora, G.S.; Levy, C.W.; Klausing, A.; Breda, C.; Read, K.D.; Edlin, C.D.; Ross, B.P.; Wright Muelas, M.; et al. A brain-permeable inhibitor of the neurodegenerative disease target kynurenine 3-monooxygenase prevents accumulation of neurotoxic metabolites. Commun Biol 2019, 2, 271. [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.P.; Franco, N.F.; Varney, B.; Sundaram, G.; Brown, D.A.; de Bie, J.; Lim, C.K.; Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Expression of the Kynurenine Pathway in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells: Implications for Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Disease. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0131389. [CrossRef]

- Sathyasaikumar, K.V.; Notarangelo, F.M.; Kelly, D.L.; Rowland, L.M.; Hare, S.M.; Chen, S.; Mo, C.; Buchanan, R.W.; Schwarcz, R. Tryptophan Challenge in Healthy Controls and People with Schizophrenia: Acute Effects on Plasma Levels of Kynurenine, Kynurenic Acid and 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic Acid. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hestad, K.; Alexander, J.; Rootwelt, H.; Aaseth, J.O. The Role of Tryptophan Dysmetabolism and Quinolinic Acid in Depressive and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Martos, D.; Tuka, B.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L.; Telegdy, G. Memory Enhancement with Kynurenic Acid and Its Mechanisms in Neurotransmission. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szatmári, I.; Vécsei, L. Quinoline Quest: Kynurenic Acid Strategies for Next-Generation Therapeutics via Rational Drug Design. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Mor, A.; Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, A.; Krupa, A.; Pawlak, D. Role of Kynurenine Pathway in Oxidative Stress during Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. From Microbial Switches to Metabolic Sensors: Rewiring the Gut-Brain Kynurenine Circuit. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.E.; Sun, L. Targeting the IDO1/TDO2-KYN-AhR Pathway for Cancer Immunotherapy - Challenges and Opportunities. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39, 307-325. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Yue, L.; Shi, J.; Shao, M.; Wu, T. Role of IDO and TDO in Cancers and Related Diseases and the Therapeutic Implications. J Cancer 2019, 10, 2771-2782. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Su, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. The Kynurenine Pathway and Indole Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism Influence Tumor Progression. Cancer Med 2025, 14, e70703. [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W.; Williams, R.O. Interactions of IDO and the Kynurenine Pathway with Cell Transduction Systems and Metabolism at the Inflammation-Cancer Interface. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, N.A.; Roudsari, N.M.; Shayan, M.; Niazi Shahraki, F.; Hosseini, Y.; Momtaz, S.; Abdolghaffari, A.H. IDO/Kynurenine; novel insight for treatment of inflammatory diseases. Cytokine 2023, 166, 156206. [CrossRef]

- Labadie, B.W.; Bao, R.; Luke, J.J. Reimagining IDO Pathway Inhibition in Cancer Immunotherapy via Downstream Focus on the Tryptophan-Kynurenine-Aryl Hydrocarbon Axis. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 1462-1471. [CrossRef]

- Campesato, L.F.; Budhu, S.; Tchaicha, J.; Weng, C.H.; Gigoux, M.; Cohen, I.J.; Redmond, D.; Mangarin, L.; Pourpe, S.; Liu, C.; et al. Blockade of the AHR restricts a Treg-macrophage suppressive axis induced by L-Kynurenine. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4011. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Kato, S.; Nesline, M.K.; Conroy, J.M.; DePietro, P.; Pabla, S.; Kurzrock, R. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitors and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2022, 110, 102461. [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, A.G.; Mingoti, M.E.D.; Ignácio, Z.M. Neurobiological mechanisms in the kynurenine pathway and major depressive disorder. Rev Neurosci 2025, 36, 169-187. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chang, R.; Zou, J.; Tan, S.; Huang, Z. The role and mechanism of tryptophan - kynurenine metabolic pathway in depression. Rev Neurosci 2023, 34, 313-324. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fishbein, J.; Hong, J.; Roeser, J.; Furie, R.A.; Aranow, C.; Volpe, B.T.; Diamond, B.; Mackay, M. Quinolinic acid, a kynurenine/tryptophan pathway metabolite, associates with impaired cognitive test performance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, T.; Dai, G.; Wang, M.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, G. Associations between the kynurenine pathway and the brain in patients with major depressive disorder-A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2023, 121, 110675. [CrossRef]

- Ogyu, K.; Kubo, K.; Noda, Y.; Iwata, Y.; Tsugawa, S.; Omura, Y.; Wada, M.; Tarumi, R.; Plitman, E.; Moriguchi, S.; et al. Kynurenine pathway in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018, 90, 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; McGuinness, A.J.; Rocks, T.; Ruusunen, A.; Cleminson, J.; Walker, A.J.; Gomes-da-Costa, S.; Lane, M.; Sanches, M.; Diaz, A.P.; et al. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4158-4178. [CrossRef]

- Joisten, N.; Ruas, J.L.; Braidy, N.; Guillemin, G.J.; Zimmer, P. The kynurenine pathway in chronic diseases: a compensatory mechanism or a driving force? Trends Mol Med 2021, 27, 946-954. [CrossRef]

- Martos, D.; Lőrinczi, B.; Szatmári, I.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. Decoupling Behavioral Domains via Kynurenic Acid Analog Optimization: Implications for Schizophrenia and Parkinson's Disease Therapeutics. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Inam, M.E.; Fernandes, B.S.; Salagre, E.; Grande, I.; Vieta, E.; Quevedo, J.; Zhao, Z. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cerebrospinal fluid studies. Braz J Psychiatry 2023, 45, 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Battaglia, S.; Liloia, D. Navigating Neurodegeneration: Integrating Biomarkers, Neuroinflammation, and Imaging in Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Motor Neuron Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Więdłocha, M.; Marcinowicz, P.; Janoska-Jaździk, M.; Szulc, A. Gut microbiota, kynurenine pathway and mental disorders - Review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110145. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Lei, L.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of microbiota and its metabolites through gut-brain axis on pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Life Sci 2024, 351, 122815. [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O'Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1877-2013. [CrossRef]

- Ohara, T.E.; Hsiao, E.Y. Microbiota-neuroepithelial signalling across the gut-brain axis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2025, 23, 371-384. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Bonfili, L.; Wei, T.; Eleuteri, A.M. Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xing, C.; Long, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.F. Impact of microbiota on central nervous system and neurological diseases: the gut-brain axis. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 53. [CrossRef]

- Góralczyk-Bińkowska, A.; Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Kozłowska, E. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, H.; He, C.; Hua, R.; Liang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, S.; Xu, J. Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Inflamm Res 2022, 15, 6213-6230. [CrossRef]

- Naufel, M.F.; Truzzi, G.M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Coelho, F.M.S. The brain-gut-microbiota axis in the treatment of neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2023, 81, 670-684. [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 37. [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjö, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 604179. [CrossRef]

- Long-Smith, C.; O'Riordan, K.J.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: New Therapeutic Opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020, 60, 477-502. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Han, C.; Shin, C. IUPHAR review: Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its role in neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Res 2025, 216, 107749. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Fan, Y.; Xu, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; et al. Microbiome and tryptophan metabolomics analysis in adolescent depression: roles of the gut microbiota in the regulation of tryptophan-derived neurotransmitters and behaviors in human and mice. Microbiome 2023, 11, 145. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qiu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Xia, X.; Li, W. Multiple pathways through which the gut microbiota regulates neuronal mitochondria constitute another possible direction for depression. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1578155. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, P. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: from pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104527. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; He, T.; Johnston, L.J.; Ma, X. Host-microbiome interactions: the aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a critical node in tryptophan metabolites to brain signaling. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1203-1219. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A. Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in Alzheimer's disease: role of tryptophan metabolites generated by gut host-microbiota. J Mol Med (Berl) 2023, 101, 201-222. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, K.; Cui, M.; Ye, W.; Zhao, G.; Jin, L.; Chen, X. The progress of gut microbiome research related to brain disorders. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 25. [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Chen, N.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, L.; He, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Hong, G. The gut microbiota-brain axis in neurological disorders. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e656. [CrossRef]

- Zatorska, O. Impact of gut microbiota on the central nervous system relevance in neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. Current Problems of Psychiatry 2024, 25, 239-247.

- Varesi, A.; Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Candiano, B.; Carrara, A.; Ricevuti, G.; Esposito, C.; Pascale, A. The brain-gut-microbiota interplay in depression: A key to design innovative therapeutic approaches. Pharmacol Res 2023, 192, 106799. [CrossRef]

- Palepu, M.S.K.; Dandekar, M.P. Remodeling of microbiota gut-brain axis using psychobiotics in depression. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 931, 175171. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Kanoujia, J.; Mohana Lakshmi, S.; Patil, C.R.; Gupta, G.; Chellappan, D.K.; Dua, K. Role of Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Depression: Emerging Therapeutic Avenues. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2023, 22, 276-288. [CrossRef]

- Generoso, J.S.; Giridharan, V.V.; Lee, J.; Macedo, D.; Barichello, T. The role of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric disorders. Braz J Psychiatry 2021, 43, 293-305. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Q.; Mou, C.K.; Lei, L.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, W.; et al. Current landscape of fecal microbiota transplantation in treating depression. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1416961. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, Q.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y. Regulatory effects of Lactobacillus zhachilii HBUAS52074(T) on depression-like behavior induced by chronic social defeat stress in mice: modulation of the gut microbiota. Food Funct 2025, 16, 691-706. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, G.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Xue, H. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum GOLDGUT-HNU082 Alleviates CUMS-Induced Depressive-like Behaviors in Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota and Neurotransmitter Levels. Foods 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.G.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, D.D.; Wu, S.X.; Huang, S.Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.J.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mental Disorders as Well as the Protective Effects of Dietary Components. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Sanada, K.; Nakajima, S.; Kurokawa, S.; Barceló-Soler, A.; Ikuse, D.; Hirata, A.; Yoshizawa, A.; Tomizawa, Y.; Salas-Valero, M.; Noda, Y.; et al. Gut microbiota and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020, 266, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Lim, Y.L.; Yaow, C.Y.L.; Ng, W.K.; Thumboo, J.; Liew, T.M. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Gut Microbiota in Patients with Major Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, M.; Clement, F.; Patten, S.; Li, J.; Dowsett, L.E.; Farkas, B.; Mastikhina, L.; Egunsola, O.; Diaz, R.; Cooke, N.C.A.; et al. The effect of interventions targeting gut microbiota on depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E1195-e1204. [CrossRef]

- Esmeeta, A.; Adhikary, S.; Dharshnaa, V.; Swarnamughi, P.; Ummul Maqsummiya, Z.; Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Plant-derived bioactive compounds in colon cancer treatment: An updated review. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 153, 113384. [CrossRef]

- Naoi, M.; Wu, Y.; Maruyama, W.; Shamoto-Nagai, M. Phytochemicals Modulate Biosynthesis and Function of Serotonin, Dopamine, and Norepinephrine for Treatment of Monoamine Neurotransmission-Related Psychiatric Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hannan, M.A.; Dash, R.; Rahman, M.H.; Islam, R.; Uddin, M.J.; Sohag, A.A.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Rhim, H. Phytochemicals as a Complement to Cancer Chemotherapy: Pharmacological Modulation of the Autophagy-Apoptosis Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 639628. [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.A.T.; Paterson, J.; Bucknall, M.; Arcot, J. Interactions between phytochemicals from fruits and vegetables: Effects on bioactivities and bioavailability. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018, 58, 1310-1329. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Gao, Z.; Lin, M.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X. Phytomedicine Fructus Aurantii-derived two absorbed compounds unlock antidepressant and prokinetic multi-functions via modulating 5-HT(3)/GHSR. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 323, 117703. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Pan, F.; Liu, D.; Ho, R.C.M.; Ho, C.S.H. Rifaximin ameliorates depression-like behaviour in chronic unpredictable mild stress rats by regulating intestinal microbiota and hippocampal tryptophan metabolism. J Affect Disord 2023, 329, 30-41. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Rubio-Arias, J.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Reche-García, C.; Leyva-Vela, B.; Nadal-Nicolás, Y. Psychological and Sleep Effects of Tryptophan and Magnesium-Enriched Mediterranean Diet in Women with Fibromyalgia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Cheung, J. The effect of mediterranean diet and chrononutrition on sleep quality: a scoping review. Nutr J 2025, 24, 31. [CrossRef]

- Scoditti, E.; Tumolo, M.R.; Garbarino, S. Mediterranean Diet on Sleep: A Health Alliance. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Ferri, R.; Lanza, G.; Caraci, F.; Vistorte, A.O.R.; Yelamos Torres, V.; Grosso, G.; Castellano, S. Mediterranean Diet and Sleep Features: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Gantenbein, K.V.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. Mediterranean Diet as an Antioxidant: The Impact on Metabolic Health and Overall Wellbeing. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Ferri, R.; Caraci, F.; Cosentino, F.I.I.; Castellano, S.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is Associated with Better Sleep Quality in Italian Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Casas, I.; Nakaki, A.; Pascal, R.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Youssef, L.; Genero, M.; Benitez, L.; Larroya, M.; Boutet, M.L.; Casu, G.; et al. Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Maternal Stress, Well-Being, and Sleep Quality throughout Gestation-The IMPACT-BCN Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Booij, L.; Merens, W.; Markus, C.R.; Van der Does, A.J. Diet rich in alpha-lactalbumin improves memory in unmedicated recovered depressed patients and matched controls. J Psychopharmacol 2006, 20, 526-535. [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.J.; Phipps, A.J.; Gallagher, P.; Scott, A.; Stevenson, P.S.; O'Brien, J.T. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and cognitive functioning in older recovered depressed subjects. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry 2005, 13, 607-615.

- Badrasawi, M.M.; Shahar, S.; Abd Manaf, Z.; Haron, H. Effect of Talbinah food consumption on depressive symptoms among elderly individuals in long term care facilities, randomized clinical trial. Clin Interv Aging 2013, 8, 279-285. [CrossRef]

- Jangid, P.; Malik, P.; Singh, P.; Sharma, M.; Gulia, A.K. Comparative study of efficacy of l-5-hydroxytryptophan and fluoxetine in patients presenting with first depressive episode. Asian J Psychiatr 2013, 6, 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Meloni, M.; Puligheddu, M.; Carta, M.; Cannas, A.; Figorilli, M.; Defazio, G. Efficacy and safety of 5-hydroxytryptophan on depression and apathy in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary finding. Eur J Neurol 2020, 27, 779-786. [CrossRef]

- Markus, C.R.; Olivier, B.; Panhuysen, G.E.; Van Der Gugten, J.; Alles, M.S.; Tuiten, A.; Westenberg, H.G.; Fekkes, D.; Koppeschaar, H.F.; de Haan, E.E. The bovine protein alpha-lactalbumin increases the plasma ratio of tryptophan to the other large neutral amino acids, and in vulnerable subjects raises brain serotonin activity, reduces cortisol concentration, and improves mood under stress. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 71, 1536-1544. [CrossRef]

- Firk, C.; Markus, C.R. Mood and cortisol responses following tryptophan-rich hydrolyzed protein and acute stress in healthy subjects with high and low cognitive reactivity to depression. Clin Nutr 2009, 28, 266-271. [CrossRef]

- Benkelfat, C.; Ellenbogen, M.A.; Dean, P.; Palmour, R.M.; Young, S.N. Mood-lowering effect of tryptophan depletion. Enhanced susceptibility in young men at genetic risk for major affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994, 51, 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K.R.; Steiger, H.; Young, S.N.; Kin, N.M.; Israël, M.; Lévesque, M. Impact of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and eating-related urges in bulimic and nonbulimic women. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2009, 34, 376-382.

- Murphy, S.E.; Longhitano, C.; Ayres, R.E.; Cowen, P.J.; Harmer, C.J. Tryptophan supplementation induces a positive bias in the processing of emotional material in healthy female volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006, 187, 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, G.H.; Causada-Calo, N.; Borojevic, R.; Nardelli, A.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Constante, M.; Libertucci, J.; Mohan, V.; Langella, P.; Loonen, L.M.P.; et al. Oral tryptophan activates duodenal aryl hydrocarbon receptor in healthy subjects: a crossover randomized controlled trial. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2024, 326, G687-g696. [CrossRef]

- Cerit, H.; Schuur, R.J.; de Bruijn, E.R.; Van der Does, W. Tryptophan supplementation and the response to unfairness in healthy volunteers. Front Psychol 2015, 6, 1012. [CrossRef]

- Markus, C.R.; Firk, C.; Gerhardt, C.; Kloek, J.; Smolders, G.F. Effect of different tryptophan sources on amino acids availability to the brain and mood in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008, 201, 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R.; Matito, S.; Cubero, J.; Paredes, S.D.; Franco, L.; Rivero, M.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Barriga, C. Tryptophan-enriched cereal intake improves nocturnal sleep, melatonin, serotonin, and total antioxidant capacity levels and mood in elderly humans. Age (Dordr) 2013, 35, 1277-1285. [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Opizzi, A.; Faliva, M.; Mozzoni, M.; Antoniello, N.; Cazzola, R.; Savarè, R.; Cerutti, R.; Grossi, E.; Cestaro, B. Effects of a diet integration with an oily emulsion of DHA-phospholipids containing melatonin and tryptophan in elderly patients suffering from mild cognitive impairment. Nutr Neurosci 2012, 15, 46-54. [CrossRef]

- Connell, N.J.; Grevendonk, L.; Fealy, C.E.; Moonen-Kornips, E.; Bruls, Y.M.H.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; de Vogel, J.; Hageman, R.; Geurts, J.; Zapata-Perez, R.; et al. NAD+-Precursor Supplementation With L-Tryptophan, Nicotinic Acid, and Nicotinamide Does Not Affect Mitochondrial Function or Skeletal Muscle Function in Physically Compromised Older Adults. J Nutr 2021, 151, 2917-2931. [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Gąsiorowska, A.; Popławski, T.; Konrad, P.; Chojnacki, M.; Fila, M.; Blasiak, J. Beneficial Effect of Increased Tryptophan Intake on Its Metabolism and Mental State of the Elderly. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Tryptophan Intake in the US Adult Population Is Not Related to Liver or Kidney Function but Is Associated with Depression and Sleep Outcomes. J Nutr 2016, 146, 2609s-2615s. [CrossRef]

- Nematolahi, P.; Mehrabani, M.; Karami-Mohajeri, S.; Dabaghzadeh, F. Effects of Rosmarinus officinalis L. on memory performance, anxiety, depression, and sleep quality in university students: A randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2018, 30, 24-28. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its active constituents on nervous system disorders. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2020, 23, 1100-1112. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Deng, K.; et al. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) hydrosol based on serotonergic synapse for insomnia. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 318, 116984. [CrossRef]

- Kenda, M.; Kočevar Glavač, N.; Nagy, M.; Sollner Dolenc, M. Medicinal Plants Used for Anxiety, Depression, or Stress Treatment: An Update. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Can, S.; Yildirim Usta, Y.; Yildiz, S.; Tayfun, K. The effect of lavender and rosemary aromatherapy application on cognitive functions, anxiety, and sleep quality in the elderly with diabetes. Explore (NY) 2024, 20, 103033. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Sharafabadi, F.M.; Marani, E. The Effect of Inhalation Aromatherapy with Essential Oils of Various Plants on Anxiety and Sleep Quality in Diabetic Patients: A Review Study. Iranian journal of diabetes and obesity 2025.

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Aromatherapy and Essential Oils: Holistic Strategies in Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Integral Wellbeing. Plants (Basel) 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mathews, I.M.; Eastwood, J.; Lamport, D.J.; Cozannet, R.L.; Fanca-Berthon, P.; Williams, C.M. Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability of Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis L.) in Psychological Well-Being: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wei, Z.; Jiang, N.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Fan, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, F. Soy isoflavones protects against cognitive deficits induced by chronic sleep deprivation via alleviating oxidative stress and suppressing neuroinflammation. Phytother Res 2022, 36, 2072-2080. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, C.R.; Manhães-de-Castro, R.; de Santana, B.; Olegário da Silva, L.; Toscano, A.E.; Guzmán-Quevedo, O.; Galindo, L.C.M. Effects of flavonols on emotional behavior and compounds of the serotonergic system: A preclinical systematic review. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 916, 174697. [CrossRef]

- Hamsalakshmi; Alex, A.M.; Arehally Marappa, M.; Joghee, S.; Chidambaram, S.B. Therapeutic benefits of flavonoids against neuroinflammation: a systematic review. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 111-136. [CrossRef]

- Scuto, M.; Majzúnová, M.; Torcitto, G.; Antonuzzo, S.; Rampulla, F.; Di Fatta, E.; Trovato Salinaro, A. Functional Food Nutrients, Redox Resilience Signaling and Neurosteroids for Brain Health. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, F.; An, L. Berberine alleviates postoperative cognitive dysfunction by suppressing neuroinflammation in aged mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2016, 38, 426-433. [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, L.S. Transient receptor potential channels as targets for phytochemicals. ACS Chem Neurosci 2014, 5, 1117-1130. [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.C.; Shibu, M.A.; Mahalakshmi, B.; Velmurugan, B.K. Effects of phytochemicals on cellular signaling: reviewing their recent usage approaches. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020, 60, 3522-3546. [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.P. Phytochemicals in Obesity Management: Mechanisms and Clinical Perspectives. Curr Nutr Rep 2025, 14, 17. [CrossRef]

- Sarris, J.; Ravindran, A.; Yatham, L.N.; Marx, W.; Rucklidge, J.J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Benedetti, F.; Caneo, C.; Cramer, H.; et al. Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce. World J Biol Psychiatry 2022, 23, 424-455. [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.Z.; Ma, Q.Y.; Tao, G.; Huang, J.Q.; Chen, J.X. Oral coniferyl ferulate attenuated depression symptoms in mice via reshaping gut microbiota and microbial metabolism. Food Funct 2021, 12, 12550-12564. [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Serio, G.; Gaglio, R.; Maffei, M.E.; Settanni, L.; Di Stefano, V.; Gentile, C. Biological Activity and Metabolomics of Griffonia simplicifolia Seeds Extracted with Different Methodologies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, R.; Oliveira, D.; Silva, P. The different roles of Griffonia simplicifolia in the treatment of depression: a narrative review. Int J Complement Alt Med 2021, 14, 167-172.

- Moharir, Y. 5-HTP for Improved Sleep, Mood and Weight Loss.

- Fellows, L.E.; Bell, E.A. 5-Hydroxy-L-tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptamine and L-tryptophan-5-hydroxylase in Griffonia simplicifolia. Phytochemistry 1970, 9, 2389-2396.

- Vigliante, I.; Mannino, G.; Maffei, M.E. Chemical Characterization and DNA Fingerprinting of Griffonia simplicifolia Baill. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Jędrejko, K.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Ziaja, M.; Kała, K.; Muszyńska, B. Edible Mushrooms as a Potential Component of Dietary Interventions for Major Depressive Disorder. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Tong, L.; Liu, X.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Soy isoflavones alleviate lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior by suppressing neuroinflammation, mediating tryptophan metabolism and promoting synaptic plasticity. Food Funct 2022, 13, 9513-9522. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, N.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q.; Fan, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, F. S-equol, a metabolite of dietary soy isoflavones, alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior in mice by inhibiting neuroinflammation and enhancing synaptic plasticity. Food Funct 2021, 12, 5770-5778. [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.; Seidler, K.; Neil, J. Investigating the Role of 17β-Estradiol on the Serotonergic System, Targeting Soy Isoflavones as a Strategy to Reduce Menopausal Depression: A Mechanistic Review. J Am Nutr Assoc 2024, 43, 221-235. [CrossRef]

- Sekikawa, A.; Wharton, W.; Butts, B.; Veliky, C.V.; Garfein, J.; Li, J.; Goon, S.; Fort, A.; Li, M.; Hughes, T.M. Potential Protective Mechanisms of S-equol, a Metabolite of Soy Isoflavone by the Gut Microbiome, on Cognitive Decline and Dementia. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Birru, R.; Snitz, B.E.; Ihara, M.; Lopresti, B.J.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Lopez, O.L.; Mathis, C.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kuller, L.H. P3-615: EFFECTS OF SOY ISOFLAVONES ON COGNITIVE FUNCTION: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2018, 14, P1365-P1366.

- Huang, M.; He, Y.; Tian, L.; Yu, L.; Cheng, Q.; Li, Z.; Gao, L.; Gao, S.; Yu, C. Gut microbiota-SCFAs-brain axis associated with the antidepressant activity of berberine in CUMS rats. J Affect Disord 2023, 325, 141-150. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Kong, L.; Jiang, Z.; Shang, R.; Zhong, X.; Lv, S.; Zhang, G.; Gao, H.; et al. Microbiota-gut-brain axis: Natural antidepressants molecular mechanism. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 156012. [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.H.; Xie, R.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Chen, S.D.; Tang, H.D. Mechanisms of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Derived from Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer's Disease. Aging Dis 2022, 13, 1252-1266. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, H.; Ju, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications. Gen Psychiatr 2024, 37, e101374. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Fu, J.; Ma, S.R.; Peng, R.; Yu, J.B.; Cong, L.; Pan, L.B.; Zhang, Z.G.; Tian, H.; Che, C.T.; et al. Gut-brain axis metabolic pathway regulates antidepressant efficacy of albiflorin. Theranostics 2018, 8, 5945-5959. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood-brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 217. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Shi, D.D.; Li, W.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zhang, S.; Tsoi, B.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.J. Berberine ameliorates depression-like behaviors in mice via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and preventing neuroplasticity disruption. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 54. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, Q.N.; Li, S.J.; Wang, H.O.; Zhou, F.; Li, J.M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Ameliorate Depressive-like Behaviors of High Fructose-Fed Mice by Rescuing Hippocampal Neurogenesis Decline and Blood-Brain Barrier Damage. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, K.A.; Dion-Albert, L.; Lebel, M.; LeClair, K.; Labrecque, S.; Tuck, E.; Ferrer Perez, C.; Golden, S.A.; Tamminga, C.; Turecki, G.; et al. Molecular adaptations of the blood-brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 3326-3336. [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F.; O'Driscoll, C.M. The blood-brain barrier in aging and neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2659-2673. [CrossRef]

- Grabska-Kobyłecka, I.; Szpakowski, P.; Król, A.; Książek-Winiarek, D.; Kobyłecki, A.; Głąbiński, A.; Nowak, D. Polyphenols and Their Impact on the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Development. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, B.N.; Parylak, S.L.; Gage, F.H. Mechanisms of dietary flavonoid action in neuronal function and neuroinflammation. Mol Aspects Med 2018, 61, 50-62. [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, A.; Patanè, G.T.; Tellone, E.; Barreca, D.; Ficarra, S.; Misiti, F.; Laganà, G. The Neuroprotective Potentiality of Flavonoids on Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Pontifex, M.G.; Malik, M.; Connell, E.; Müller, M.; Vauzour, D. Citrus Polyphenols in Brain Health and Disease: Current Perspectives. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 640648. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Coria, H.; Arrieta-Cruz, I.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, R.; López-Valdés, H.E. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Flavonoids in Common Neurological Disorders Associated with Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Bakoyiannis, I.; Daskalopoulou, A.; Pergialiotis, V.; Perrea, D. Phytochemicals and cognitive health: Are flavonoids doing the trick? Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 109, 1488-1497. [CrossRef]

- Zagoskina, N.V.; Zubova, M.Y.; Nechaeva, T.L.; Kazantseva, V.V.; Goncharuk, E.A.; Katanskaya, V.M.; Baranova, E.N.; Aksenova, M.A. Polyphenols in Plants: Structure, Biosynthesis, Abiotic Stress Regulation, and Practical Applications (Review). Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, F.; Hosseini, R.; Saso, L.; Firuzi, O. Modulation of neurotrophic signaling pathways by polyphenols. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016, 10, 23-42. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of Phenylpropanoid Pathway and the Role of Polyphenols in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Lucey, A.; Doyle, L. Flavonoid Containing Polyphenol Consumption and Recovery from Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 2021, 51, 1293-1316. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Du, P.; Xie, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Smith, E.E.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Huo, G.; Li, B. Protective effects of tryptophan-catabolizing Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS 1.0386 against dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Food Funct 2020, 11, 10736-10747. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. Int J Tryptophan Res 2018, 11, 1178646918802282. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, L.; Elsaraf, M.; Mindt, M.; Wendisch, V.F. l-Serine Biosensor-Controlled Fermentative Production of l-Tryptophan Derivatives by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.W.; Liu, X.J.; Yuan, J.; Li, H.J.; Mahmud, T.; Hong, M.J.; Yu, J.C.; Lan, W.J. l-Tryptophan Induces a Marine-Derived Fusarium sp. to Produce Indole Alkaloids with Activity against the Zika Virus. J Nat Prod 2020, 83, 3372-3380. [CrossRef]

- Henarejos-Escudero, P.; Méndez-García, F.F.; Hernández-García, S.; Martínez-Rodríguez, P.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Design, Synthesis and Gene Modulation Insights into Pigments Derived from Tryptophan-Betaxanthin, Which Act against Tumor Development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; Turner, J.; Del Mar, C. Tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002, Cd003198. [CrossRef]

- Herrington, R.N.; Bruce, A.; Johnstone, E.C. Comparative trial of L-tryptophan and E.C.T. in severe depressive illness. Lancet 1974, 2, 731-734. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, A.M.; Tanabe, A.; Iwahori, Y. A systematic review of the effect of L-tryptophan supplementation on mood and emotional functioning. J Diet Suppl 2021, 18, 316-333. [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Qian, X.; Zou, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Qian, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1025 attenuates major depression disorder via regulating gut microbiome and tryptophan metabolism: A randomized clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 100, 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Su, T.; Wu, P.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S. Identification of paeoniflorin from Paeonia lactiflora pall. As an inhibitor of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase and assessment of its pharmacological effects on depressive mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 317, 116714. [CrossRef]

- Kałużna-Czaplińska, J.; Gątarek, P.; Chirumbolo, S.; Chartrand, M.S.; Bjørklund, G. How important is tryptophan in human health? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 72-88. [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, C.N.; Loh, W.W.; Toh, D.W.K.; Lee, D.P.S.; Kim, J.E. Association Between Dietary Protein Intake and Sleep Quality in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Singapore. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 832341. [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, C.N.; Loh, W.W.; Kim, J.E. The impact of tryptophan supplementation on sleep quality: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Nutr Rev 2022, 80, 306-316. [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, M.H.; Wittwer, J.; Vargas, K.; Hogan, E.; Holmes, A.; Rogers, P.J.; Goralczyk, R.; Gibson, E.L. Chronic treatment with a tryptophan-rich protein hydrolysate improves emotional processing, mental energy levels and reaction time in middle-aged women. Br J Nutr 2015, 113, 350-365. [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.A.; Fu, J.; Chang, P.V. Microbial tryptophan metabolites regulate gut barrier function via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 19376-19387. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Mi, S.; Ruan, Z.; Li, J.; Shu, X.; Yao, K.; Jiang, M.; Deng, Z. Dietary Tryptophan Enhanced the Expression of Tight Junction Protein ZO-1 in Intestine. J Food Sci 2017, 82, 562-567. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Dai, Z.; Kou, J.; Sun, K.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, G.; Wu, Z. Dietary l-Tryptophan Supplementation Enhances the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Function in Weaned Piglets: Implication of Tryptophan-Metabolizing Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 20. [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S. Tryptophan Dietary Impacts Gut Barrier and Metabolic Diseases. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2113. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Bai, M.; Peng, C.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Intestinal Immunity Mediated by Tryptophan Metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Modulating Gut Microbiota with Dietary Components: A Novel Strategy for Cancer-Depression Comorbidity Management. Nutrients 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, P.; Herbet, M. Role of the Intestinal Microbiome, Intestinal Barrier and Psychobiotics in Depression. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; Mendes, N.M.; Pereira de Lima, E.; Chehadi, A.C.; Lamas, C.B.; Haber, J.F.S.; Dos Santos Bueno, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. Curcumin: A Golden Approach to Healthy Aging: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Daglia, M.; Braidy, N.; Nabavi, S.F. Natural products, micronutrients, and nutraceuticals for the treatment of depression: A short review. Nutr Neurosci 2017, 20, 180-194. [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J.D. Effects and side effects associated with the non-nutritional use of tryptophan by humans. J Nutr 2012, 142, 2236s-2244s. [CrossRef]