1. Introduction

ISAC has emerged as a key paradigm for next-generation wireless networks, where a common hardware platform and joint signal processing are leveraged to simultaneously support communication and sensing functionalities [

1,

2]. By enabling spectrum sharing and hardware reuse, ISAC offers significant advantages regarding spectral efficiency, energy consumption, and system cost, which are critical for future applications such as autonomous driving, smart cities, and industrial automation.

Despite its potential, one of the fundamental challenges in ISAC systems lies in managing the inherent trade-off between communication performance and sensing accuracy. Due to the shared use of resources, such as waveform, power, and spatial degrees of freedom, optimizing the system for communication often degrades the sensing performance, and vice versa. Thus, effective ISAC design necessitates a careful balance between these competing objectives [

1].

This trade-off is most evident in the design of transmit signal structures, where communication and sensing often require conflicting properties. Communication schemes aim to maximize the data rate or reliability, favoring directional beamforming and power allocation strategies aligned with user channel eigenmodes. In contrast, sensing tasks such as target detection or parameter estimation benefit from broader spatial coverage, diversified or orthogonal signal structures, and more uniform energy allocation to enhance resolution and robustness. These differences are fundamentally reflected in the transmit covariance matrix, which governs the spatial and spectral properties of the transmitted signal. Although communication-oriented designs optimize the covariance matrix for spectral efficiency, often through water filling or eigenmode transmission, sensing-centric designs instead emphasize uniform or structured energy distribution, for example, by allocating power to dedicated sensing components or constraining the matrix condition number, with performance typically assessed through criteria such as Cramér-Rao bound (CRB) or mean squared error (MSE) [

2,

3].

Recent works have explored optimization frameworks that jointly design transmit signals or beamformers under dual constraints. Some studies adopt weighted sum objectives, where a regularization or tuning parameter controls the trade-off between communication rate and sensing fidelity. For example, in [

4], the authors formulate a beamforming design that interpolates the approximation of the radar-centric beam pattern and the communication rate through a regularization parameter, offering flexible trade-offs. Other works pose Pareto-optimal or boundary-tracing frameworks to characterize what communication and sensing performance combinations are achievable [

5].

This work proposes a constraint-based approach to manage the ISAC trade-off in multi-user systems. Specifically, we optimize communication performance, focusing on the sum data rate, subject to structural constraints on the transmit covariance matrix that are known empirically or theoretically to favor sensing. Rather than placing explicit limits on sensing metrics such as MSE or CRB [

5], these constraints include, for example, limiting the condition number of the covariance matrix or reserving a portion of the transmit power for dedicated sensing signals. These design choices embed sensing-awareness into communication without solving a multi-objective optimization. The effectiveness of the proposed approach is assessed via the resulting channel estimation MSE at the sensing receiver, which serves as an indirect indicator of sensing quality. This formulation offers a tractable method for joint resource allocation that aligns with the dual goals of ISAC.

2. System Model

We consider an ISAC system with a transmitter equipped with antennas, a sensing receiver equipped with antennas, and K User Equipment (UEs), each equipped with antennas.

The transmitted signals are denoted by for , where is a dedicated sensing signal and L is the number of Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) symbols. The covariance matrix of each column of these signals is given by for each and for each .

The communication channel from the transmitter to the k-th UE is denoted by , where .

The received signal at the

k-th communication receiver is given by

where

denotes the received communication signal, and

is the additive noise matrix at the communication receiver, whose columns are i.i.d. and follow the complex standard normal distribution with standard deviation

, i.e.,

.

Then, for the sake of mathematical convenience, we denote:

Similarly, the sensing channel is denoted by , modeling the round-trip response from the Base Station (BS) to the environment and back.

The received signal at the sensing receiver is given by

where

denotes the received sensing signal, and

is the additive noise matrix at the sensing receiver, whose columns are i.i.d. and follow the complex standard normal distribution with standard deviation

, i.e.,

.

Then, for the sake of mathematical convenience, we denote:

The transmitter employs dirty paper coding (DPC) [

6] to encode user signals due to its capacity-achieving property in multi-user Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO). In DPC, users are encoded sequentially, allowing the transmitter to pre-cancel interference from previously encoded users by treating it as known. Consequently, each user only experiences interference from those encoded later, with the last user in the sequence enjoying an interference-free channel.

The achievable rate for user

i under DPC is:

where the encoding order

determines the interference structure. The numerator includes the user’s signal and interference from later users, while the denominator excludes the user’s contribution, isolating the remaining interference.

This structure enables DPC to achieve the Gaussian broadcast channel (BC) capacity under a sum-power constraint. The sensing signal , known at the BS, does not interfere with the DPC chain, affecting only the total available transmit power.

To estimate the sensing channel

, we employ the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator [

3]. The ML estimate of

is given by:

The ML estimator is optimal under Gaussian noise and known channel statistics. Its performance depends heavily on the conditioning of the matrix . As the number of OFDM symbols L grows, the expectation of converges to . Therefore, ensuring that is well-conditioned improves the accuracy of the channel estimate.

The quality of the sensing is quantified by the Normalized Mean Square Error (NMSE) of the channel estimate:

A low NMSE indicates a more accurate estimation, essential for effective sensing.

5. Evaluation Results

To estimate a channel, it is necessary to probe all orthogonal directions defined by its singular vectors. Under the assumption , which is typical for monostatic sensing where the same node transmits and receives the signal, a sensing channel of dimension has singular vectors, corresponding to orthogonal directions or degrees of freedom. In contrast, a communication channel of dimension , with , effectively supports only degrees of freedom. To maximize data rate, transmit power should be concentrated on these dominant directions, rather than being spread across the unused directions. Balancing this trade-off is critical, as leveraging the full degrees of freedom is essential for accurate sensing, but only degrees of freedom contribute directly to communication. This tension forms the basis for the analysis presented in this section.

This evaluation considers a urban macro-cell (UMa) scenario, featuring a single BS and one sector site or cell with a 500-m diameter. The BS is centrally positioned in the cell at a height of 25 m. Communication users (or UEs) are randomly distributed within this area at a height of m, with a minimum 3D distance of m from the BS.

For sensing, a mono-static mode is implemented, where the BS both transmits and receives the signal used for sensing. The target for sensing is randomly positioned within the environment and always maintains a Line of Sight (LoS) condition relative to the BS. Communication users’ LoS or Non Line of Sight (NLoS) conditions follow the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) model specifications, which determine visibility based on urban propagation factors.

The BS has a antenna array, while each UE has a linear array. All antenna elements are spaced apart, where represents the signal wavelength.

Table 1 provides the detailed configuration parameters for the evaluated scenario. Building on the network layout described previously, the evaluation requires a large set of random seeds, approximately 10,000, to ensure robust statistical reliability. The number of OFDM symbols (

L) for channel estimation varies from 64 to 2048.

Following guidelines from Table 7.8-1 in TR 38.901 [

10], certain simulation assumptions are applied for the communication-only scenarios, including parameters like carrier frequency, sampling frequency, and the number of subcarriers. The hybrid ISAC channel model from [

11] is utilized for sensing functions, while the 3GPP channel model supports the communication aspects. This setup enables a comprehensive assessment of the performance trade-offs in the ISAC system under realistic conditions.

In this study, an underdetermined system refers to scenarios where the number of available degrees of freedom (determined by transmit antennas) exceeds the number of active receive antennas. Such systems are flexible but underutilized, leaving resources untapped. In contrast, an overdetermined system arises when users attempt to utilize or exceed the available degrees of freedom fully. These systems are resource-constrained but better conditioned for optimal performance.

This paper explores the trade-offs between communication and sensing in systems with varying numbers of UEs, focusing on the influence of the condition number and power allocation on performance. Results are analyzed for three scenarios: a system with 5 UEs, representing an underdetermined case; 8 UEs, where the system is balanced with an equal number of transmit and receive antennas; and 10 UEs, where the system becomes overdetermined, with more receive antennas than transmit antennas.

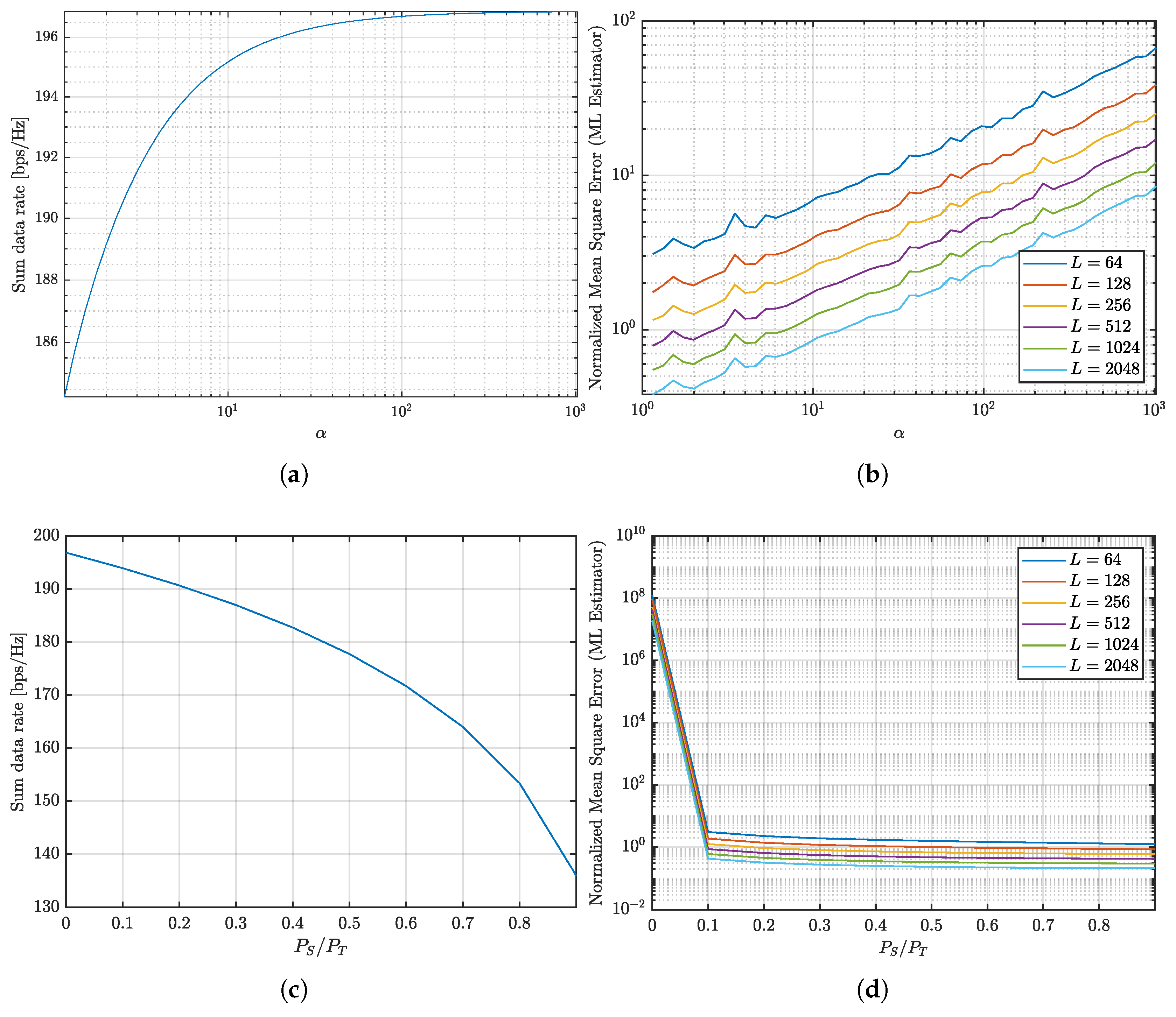

Figure 1 analyzes the communication and sensing trade-off when 5 UEs are allocated.

Figure 1a illustrates the relationship between the sum data rate and the condition number. As the condition number increases, the sum data rate also rises. This behavior is expected, as a higher condition number implies a softer constraint on the sum of the covariance matrices, allowing greater flexibility in power allocation to maximize the sum data rate. However, the sum data rate eventually flattens at approximately 196 bps/Hz.

Figure 1b shows the NMSE as a function of the condition number for various OFDM symbol counts (

). The NMSE increases with the condition number, reflecting reduced accuracy in sensing channel estimation due to poor conditioning of the transmit covariance matrices. However, the NMSE decreases as the number of OFDM symbols (

L) increases. This improvement occurs because a larger

L provides more observations over time, enabling better averaging of noise.

Figure 1c demonstrates the sum data rate decline as more power is allocated to sensing. As the sensing power fraction (

) increases, less power remains available for communication, leading to a reduction in system capacity.

Figure 1d illustrates the NMSE as a function of

for different OFDM symbol counts. Introducing a dedicated sensing signal significantly improves the NMSE, particularly when a small fraction of power is allocated to sensing. Beyond this point, further increases in sensing power yield diminishing returns, as the NMSE stabilizes.

Increasing the condition number results in higher sum data rates and NMSE. Increasing the number of OFDM symbols enhances sensing accuracy because the larger symbol set improves the channel estimation process by mitigating noise through averaging. However, increasing the number of OFDM symbols requires larger delays on sensing channel estimation, and the channel has to be stable during transmitting those symbols. Therefore, increasing the number of OFDM symbols might not always be an option. Conversely, allocating additional power to sensing reduces overall system capacity. For systems where the number of transmit antennas exceeds the number of receive antennas, dedicating a small portion of power to sensing achieves an optimal balance. For example, allocating 10% of the total power to sensing decreases the sum data rate by only 3 bps/Hz, while dramatically reducing the NMSE from to . Achieving comparable accuracy without a dedicated sensing signal would result in a much larger loss in sum data rate, exceeding 10 bps/Hz.

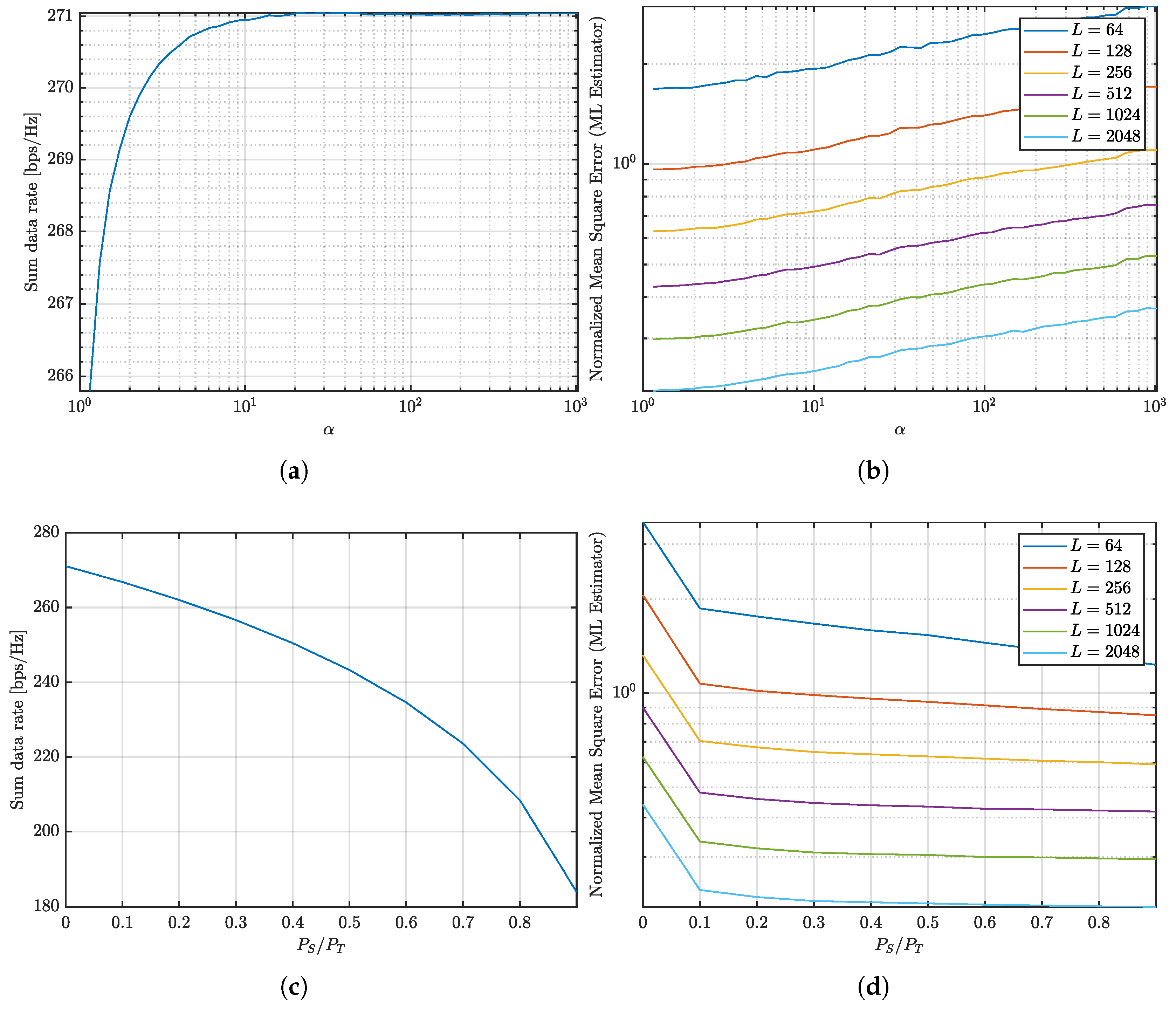

After analyzing the trade-off behavior in a scenario where there are more transmit antennas (32 at the BS) than receive antennas (20 in total, with 4 antennas per UE across 5 UEs), it is interesting to explore what happens when the number of antennas is balanced between transmission and reception. Specifically, we consider a case with 32 antennas at the BS and 8 UEs, each equipped with 4 antennas, resulting in an equal number of transmit and receive antennas.

Figure 2 examines the communication and sensing trade-off for this scenario.

In

Figure 2a, the sum data rate is shown as a function of the condition number. As in the previous scenario, the sum data rate increases with the condition number, but the growth rate is slower compared to the case with 5 UEs. This difference arises because the system now has an equal number of transmit and receive antennas, leading to better conditioning the sum of the signal covariance matrices. Similarly,

Figure 2b depicts the NMSE as a function of the condition number. Here, the NMSE also increases more gradually than in the 5 UEs case. While increasing the number of OFDM symbols continues to improve sensing performance, the improvement in NMSE is less pronounced due to the more balanced antenna configuration.

Figure 2c highlights how increasing the sensing power fraction (

) reduces the sum data rate, consistent with the 5 UEs case. However,

Figure 2d shows that the corresponding reduction in NMSE is less significant than before. This indicates that allocating power to sensing in a balanced system configuration is less impactful, as the system is inherently better conditioned for communication and sensing tasks.

Keeping the condition number below 10 achieves similar NMSE performance compared with having a sensing dedicated signal and has minimal impact on communication capacity. Therefore, limiting the condition number proves to be a more efficient strategy for maximizing the sum data rate and keeping a low NMSE compared to allocating additional power to sensing.

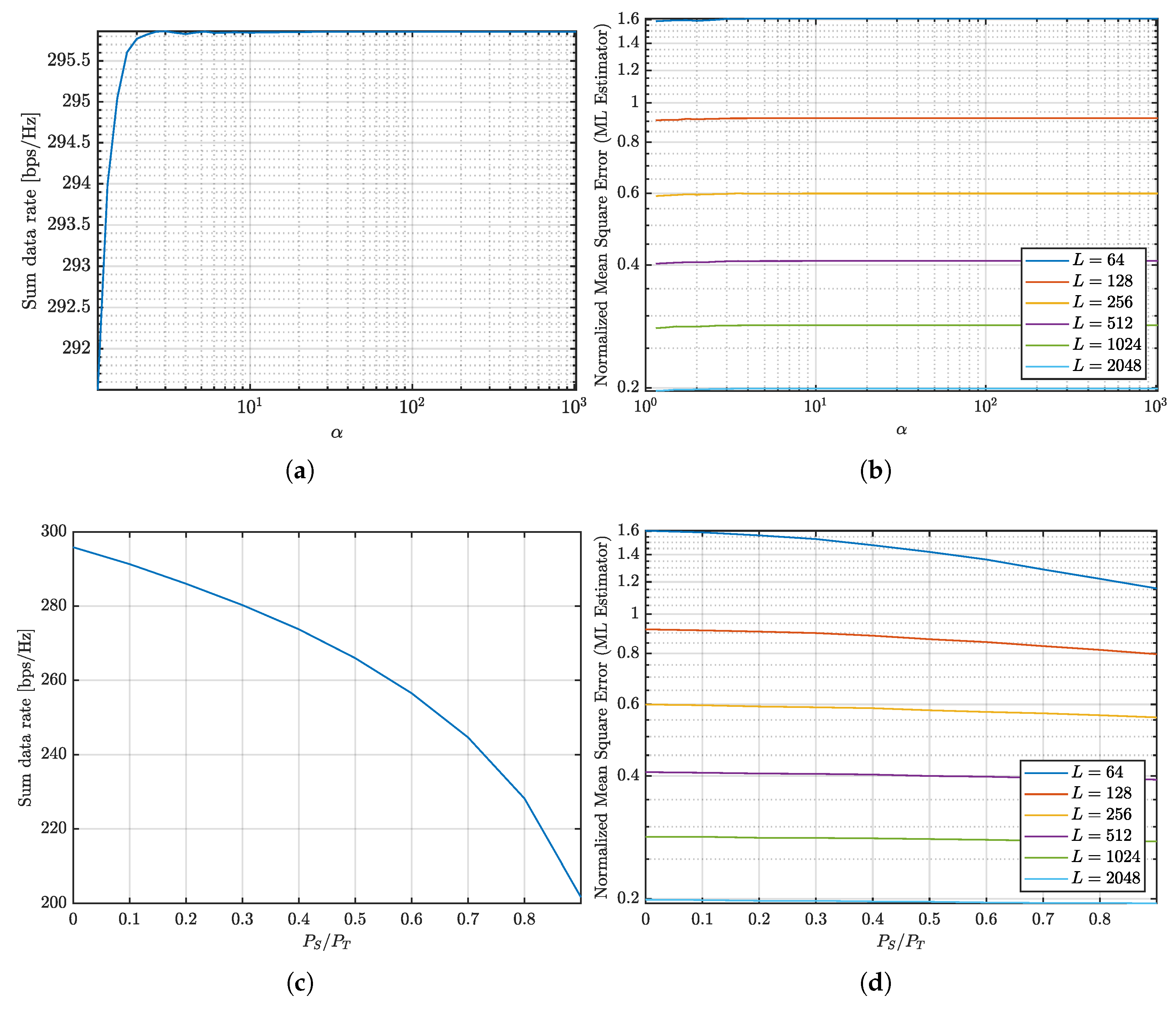

Finally, we analyze a scenario where the number of receive antennas exceeds the number of transmit antennas. Specifically, we assess a system with 10 UEs, corresponding to 32 transmit antennas at the BS and 40 receive antennas across the UEs.

Figure 3a shows that the sum data rate remains unaffected, mainly as the condition number increases. This stability arises because the sum of the covariance matrices in this configuration is inherently well-conditioned, enabling the system to achieve near-optimal performance without requiring additional adjustments.

Similarly,

Figure 3b illustrates that the NMSE remains relatively stable as the condition number increases, further confirming that matrix conditioning is less critical in this scenario compared to the previous cases.

Figure 3c demonstrates that allocating power to sensing significantly reduces the sum data rate. However,

Figure 3d shows that the corresponding improvement in NMSE is minimal. This indicates that dedicating power to sensing in this configuration is not worthwhile, as the marginal benefits in sensing accuracy do not justify the substantial loss in communication capacity.

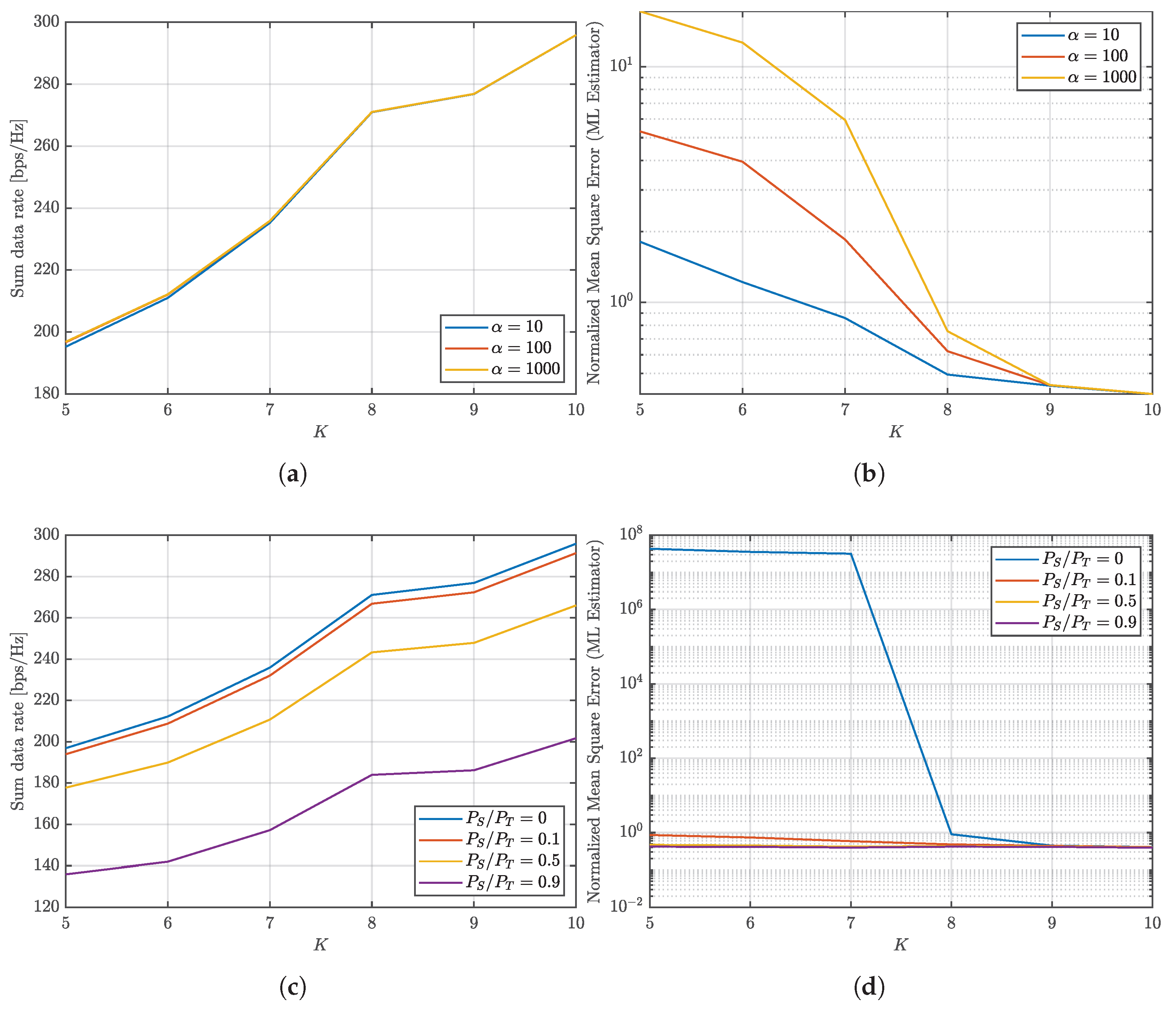

To complement the previous analysis, we present additional graphs illustrating how the system transitions from underdetermined to overdetermined as the number of users increases. To analyze this transition, we consider scenarios with 5 to 10 users, three condition numbers (

) values (10, 100, and 1000), and four power allocation ratios (

): 0, 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9.

Figure 4 presents the results for the sum data rate and NMSE across different numbers of UEs, condition numbers, and power allocation ratios.

Figure 4a displays the sum data rate as a function of the number of users for various condition number values. The results show an increasing trend in the sum data rate, but the growth slows noticeably after 8 users. This behavior reflects the transition from an underdetermined system (fewer than 8 users, where the degrees of freedom exceed the number of active receivers, leading to underutilization) to an overdetermined system (8 or more users, where the number of active receivers matches or exceeds the available degrees of freedom). In the overdetermined regime, adding more users diminishes gains in the sum data rate, as the system’s resources are already fully engaged.

Regarding the NMSE,

Figure 4b demonstrates that limiting the condition number reduces the error. However, after 9 users, the system becomes inherently well-conditioned due to the overdetermined configuration, eliminating the need for further constraints. This indicates that the presence of more users naturally balances the system, improving performance.

Next, we analyze

Figure 4c and

Figure 4d to evaluate the impact of allocating power to sensing. In

Figure 4c, the sum data rate increases as users grow but decreases with higher

. These results are expected, as dedicating more power to sensing reduces the power available for communication. However,

Figure 4d highlights that using a dedicated sensing signal significantly reduces the NMSE, particularly when the system is underdetermined (fewer than 8 users). In this regime, allocating just 10% of the total power to sensing is sufficient to achieve acceptable error levels. Beyond this point, further increases in sensing power offer minimal improvements in error reduction but result in a significant degradation of the sum data rate.