Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

28 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

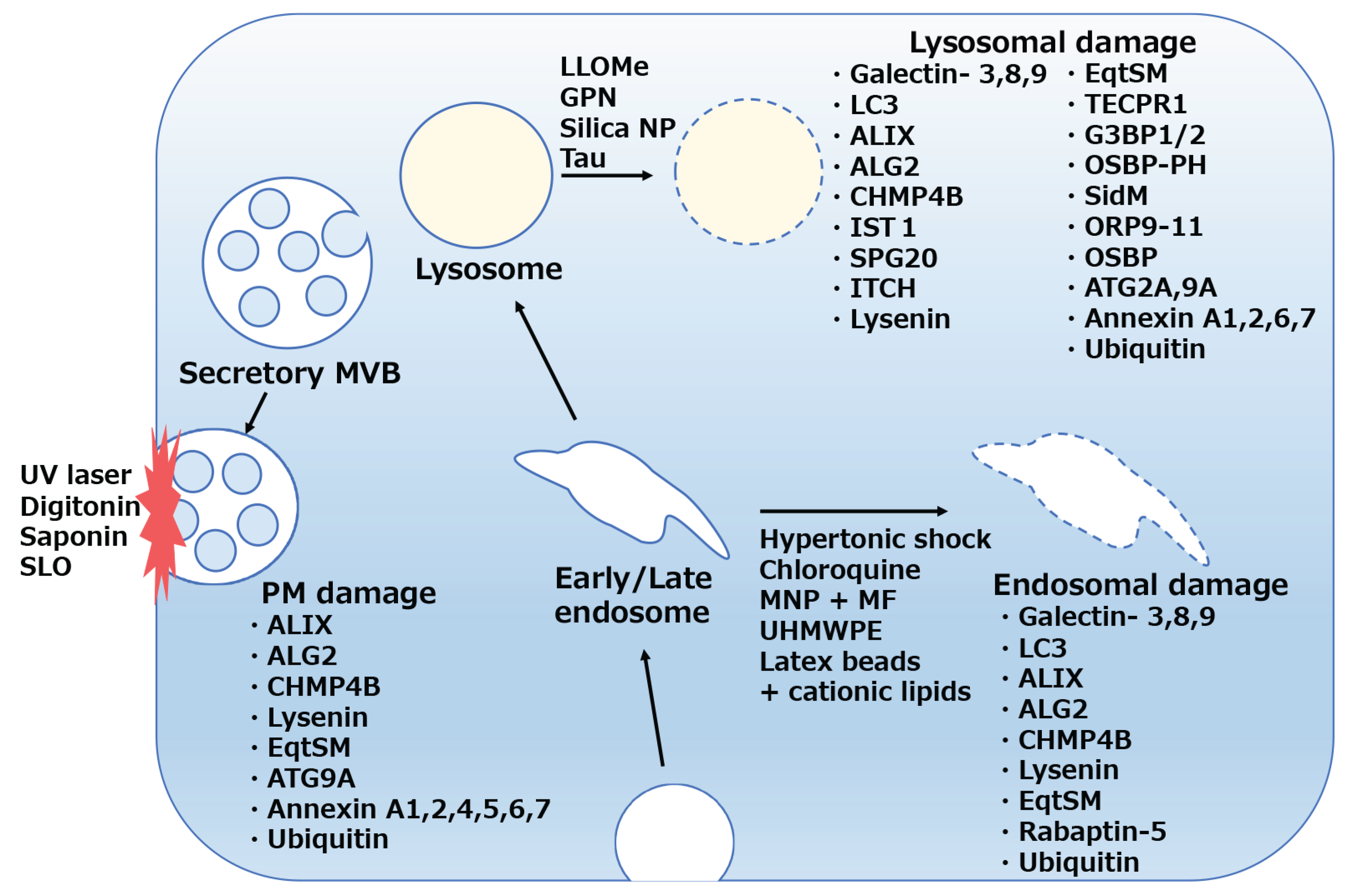

Mammalian cells contain many membranous organelles, among which endosomes are the initial destination for endocytosed materials. Drugs and pathogens, such as bacteria, are internalized by cells and transported to endosomes or phagosomes, then to lysosomes for degradation. Internalized drugs must escape from endosomes into the cytosol before undergoing degradation in lysosomes. However, endosomal escape is often inefficient in artificial drug delivery systems (DDSs). In contrast, many pathogens are phagocytosed and subsequently escape into the cytosol to proliferate. The studies on phagosomal escape of pathogens have revealed the molecular mechanisms through which host cells detect organelle membrane damage. In this review, we first provide an overview of bacterial endosomal and phagosomal escape, focusing on Shigella flexneri as a model organism. We then describe the current knowledge on the cellular machinery involved in sensing and repairing membrane damage, including galectins, ESCRTs, sphingomyelin, stress granules, PI4P in membrane contact sites, and Annexins. We further discuss the roles of secretory MVBs in plasma membrane repair in the Annexins and Future Perspectives sections. Research on membrane damage not only advances our understanding of cellular responses to damage caused by pathogens and artificial nanoparticles, but also informs the design of more effective DDSs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

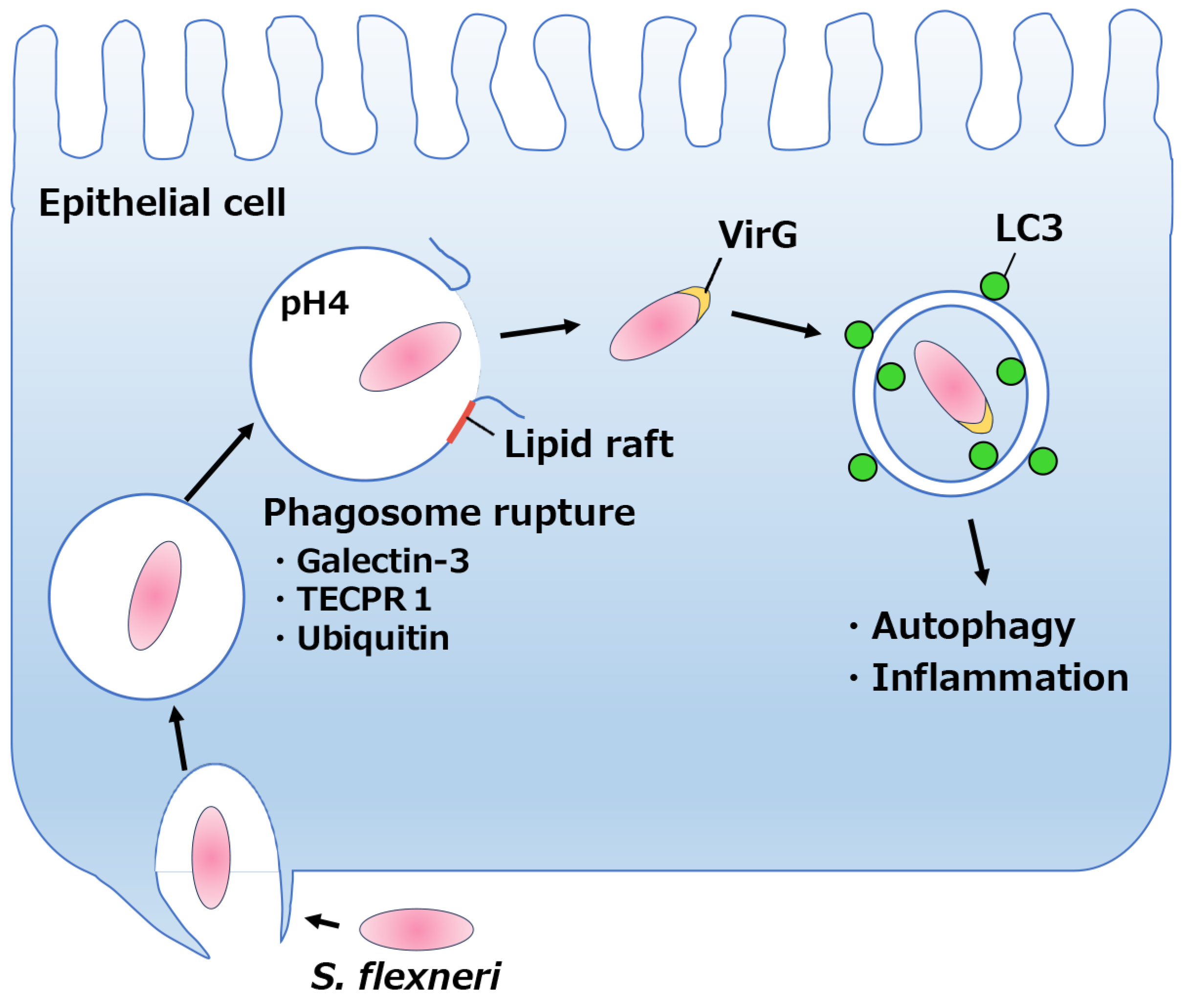

2. Phagosomal Escape by Shigella Species

2.1. Overview of Infection by Shigella spp.

2.2. Phagosomal lysis

3. Molecular Detection of Membrane Damage in Mammalian Cells

3.1. Galectins

3.1.1. Galectin-3

3.1.2. Galectin-8, 9

3.2. ESCRTs

3.2.1. Overview of ESCRT Proteins

3.2.2. ESCRT in Plasma Membrane Damage

3.2.3. ESCRT in Lysosomal Membrane Damage

3.2.4. ESCRT in Endosomal Membrane Damage

3.2.5. ESCRT in Bacteria-Containing Vacuoles

3.3. Sphingomyelin

3.3.1. Sphingomyelin Exposure in Phagosomal Escape

3.3.2. Sphingomyelin Receptor in Membrane Damage

3.3.3. Sphingomyelin Pathway in Membrane Damage

3.4. Stress Granules

3.5. Rabaptin-5 in Endosomal Damage

3.6. Membrane Contact Sites in Membrane Repair

3.6.1. Phosphatidylinositol-4 Phosphate (PI4P) in Lysosomal Damage

3.6.2. ATG2-ATG9 in Membrane Damage

3.7. Annexins

3.7.1. Annexins in Plasma Membrane Repair

3.7.2. Annexins in Endolysosomal Repair

3.7.3. Annexins for Secretory Lysosome/MVB Fusion to the Plasma Membrane

4. Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Dong, J.; Tong, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Jin, X.; Chen, J.; Jia, H.; Gao, M.; Wei, M.; et al. Endosomal traffic disorders: a driving force behind neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiborg, C.; Rusten, T.E.; Stenmark, H. Protein sorting into multivesicular endosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2003, 15, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, J.; Helenius, A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J 2011, 30, 3481–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.C.; Vacca, F.; Gruenberg, J. Endosome maturation, transport and functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 31, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, R.F.; Powers, S.; Cantor, C.R. Endosome pH measured in single cells by dual fluorescence flow cytometry: rapid acidification of insulin to pH 6. J Cell Biol 1984, 98, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielian, M.C.; Marsh, M.; Helenius, A. Kinetics of endosome acidification detected by mutant and wild-type Semliki Forest virus. EMBO J 1986, 5, 3103–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, D.J.; Maxfield, F.R. Acidification of morphologically distinct endosomes in mutant and wild-type Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Cell Biol 1987, 105, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.W.; Maxfield, F.R. Delivery of ligands from sorting endosomes to late endosomes occurs by maturation of sorting endosomes. J Cell Biol 1992, 117, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Soe, T.T.; Maxfield, F.R. Endocytic sorting of lipid analogues differing solely in the chemistry of their hydrophobic tails. J Cell Biol 1999, 144, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvig, K.; Ryd, M.; Garred, O.; Schweda, E.; Holm, P.K.; van Deurs, B. Retrograde transport from the Golgi complex to the ER of both Shiga toxin and the nontoxic Shiga B-fragment is regulated by butyric acid and cAMP. J Cell Biol 1994, 126, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neel, E.; Chiritoiu-Butnaru, M.; Fargues, W.; Denus, M.; Colladant, M.; Filaquier, A.; Stewart, S.E.; Lehmann, S.; Zurzolo, C.; Rubinsztein, D.C.; et al. The endolysosomal system in conventional and unconventional protein secretion. J Cell Biol 2024, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chang, B.; Lin, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, W.; Ding, S.; Zhan, W.; Wang, S.; Xiao, B.; et al. Intercellular transfer of activated STING triggered by RAB22A-mediated non-canonical autophagy promotes antitumor immunity. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 1086–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Beek, J.; de Heus, C.; Sanza, P.; Liv, N.; Klumperman, J. Loss of the HOPS complex disrupts early-to-late endosome transition, impairs endosomal recycling and induces accumulation of amphisomes. Mol Biol Cell 2024, 35, ar40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Yoshimori, T.; Suzuki, T.; Sagara, H.; Mizushima, N.; Sasakawa, C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science 2005, 307, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; Yoshimori, T.; Ohsumi, Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2011, 27, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi, Y. Historical landmarks of autophagy research. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, G.N.; Hilbi, H. Molecular pathogenesis of Shigella spp.: controlling host cell signaling, invasion, and death by type III secretion. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.; Sekirov, I.; Finlay, B.B. Type III secretion systems and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okui, N. Dr. Kiyoshi Shiga (1871-1957): Outstanding Bacteriologist Who Discovered Dysentery Bacillus and Contributed Immensely to Public Health in Japan. Cureus 2024, 16, e71881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassef, J.S.; Keren, D.F.; Mailloux, J.L. Role of M cells in initial antigen uptake and in ulcer formation in the rabbit intestinal loop model of shigellosis. Infect Immun 1989, 57, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansonetti, P.J.; Arondel, J.; Cantey, J.R.; Prevost, M.C.; Huerre, M. Infection of rabbit Peyer's patches by Shigella flexneri: effect of adhesive or invasive bacterial phenotypes on follicle-associated epithelium. Infect Immun 1996, 64, 2752–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zychlinsky, A.; Prevost, M.C.; Sansonetti, P.J. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature 1992, 358, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, D.F.; Watkins, H.M. Growth of shigellae in monolayer tissue cultures. J Bacteriol 1961, 82, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.L.; Morris, R.E.; Bonventre, P.F. Shigella infection of henle intestinal epithelial cells: role of the host cell. Infect Immun 1979, 24, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaks, E.V.; Wingfield, M.E.; Formal, S.B. Plaque formation by virulent Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun 1985, 48, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, M.L.; Mounier, J.; d'Hauteville, H.; Coquis-Rondon, M.; Sansonetti, P.J. Identification of icsA, a plasmid locus of Shigella flexneri that governs bacterial intra- and intercellular spread through interaction with F-actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989, 86, 3867–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, S.; Sasakawa, C.; Kamata, K.; Kurata, T.; Yoshikawa, M. A genetic determinant required for continuous reinfection of adjacent cells on large plasmid in S. flexneri 2a. Cell 1986, 46, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurelli, A.T.; Baudry, B.; d'Hauteville, H.; Hale, T.L.; Sansonetti, P.J. Cloning of plasmid DNA sequences involved in invasion of HeLa cells by Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun 1985, 49, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, J.; Ito, K.; Nakamura, A.; Watanabe, H. Cloning of regions required for contact hemolysis and entry into LLC-MK2 cells from Shigella sonnei form I plasmid: virF is a positive regulator gene for these phenotypes. Infect Immun 1989, 57, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasakawa, C.; Kamata, K.; Sakai, T.; Makino, S.; Yamada, M.; Okada, N.; Yoshikawa, M. Virulence-associated genetic regions comprising 31 kilobases of the 230-kilobase plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2a. J Bacteriol 1988, 170, 2480–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajunaid, W.; Haidar-Ahmad, N.; Kottarampatel, A.H.; Ourida Manigat, F.; Silue, N.; Tchagang, C.F.; Tomaro, K.; Campbell-Valois, F.X. The T3SS of Shigella: Expression, Structure, Function, and Role in Vacuole Escape. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubos, R.J.; Geiger, J.W. Preparation and properties of Shiga toxin and toxoid. J Exp Med 1946, 84, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keusch, G.T.; Jacewicz, M. The pathogenesis of Shigella diarrhea. VI. Toxin and antitoxin in Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei infections in humans. J Infect Dis 1977, 135, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantey, J.R. Infectious diarrhea. Pathogenesis and risk factors. Am. J. Med. 1985, 78, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, A.D.; Thompson, M.R.; Gemski, P.; Doctor, B.P.; Formal, S.B. Biological properties of Shigella flexneri 2A toxin and its serological relationship to Shigella dysenteriae 1 toxin. Infect Immun 1977, 15, 796–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.L.; Formal, S.B. Protein synthesis in HeLa or Henle 407 cells infected with Shigella dysenteriae 1, Shigella flexneri 2a, or Salmonella typhimurium W118. Infect Immun 1981, 32, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemski, P.; Takeuchi, A.; Washington, O.; Formal, S.B. Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae. 1. Relative importance of mucosal invasion versus toxin production in pathogenesis. J Infect Dis 1972, 126, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Loughlin, E.V.; Robins-Browne, R.M. Effect of Shiga toxin and Shiga-like toxins on eukaryotic cells. Microbes Infect 2001, 3, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, A.; Arondel, J.; Sansonetti, P.J. Role of Shiga toxin in the pathogenesis of bacillary dysentery, studied by using a Tox- mutant of Shigella dysenteriae 1. Infect Immun 1988, 56, 3099–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansonetti, P.J.; Ryter, A.; Clerc, P.; Maurelli, A.T.; Mounier, J. Multiplication of Shigella flexneri within HeLa cells: lysis of the phagocytic vacuole and plasmid-mediated contact hemolysis. Infect Immun 1986, 51, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, N.; Mounier, J.; Prevost, M.C.; Sansonetti, P.J. IpaB of Shigella flexneri causes entry into epithelial cells and escape from the phagocytic vacuole. EMBO J 1992, 11, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoudy, A.; Mounier, J.; Aruffo, A.; Ohayon, H.; Gounon, P.; Sansonetti, P.; Tran Van Nhieu, G. CD44 binds to the Shigella IpaB protein and participates in bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 2000, 2, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafont, F.; Tran Van Nhieu, G.; Hanada, K.; Sansonetti, P.; van der Goot, F.G. Initial steps of Shigella infection depend on the cholesterol/sphingolipid raft-mediated CD44-IpaB interaction. EMBO J 2002, 21, 4449–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senerovic, L.; Tsunoda, S.P.; Goosmann, C.; Brinkmann, V.; Zychlinsky, A.; Meissner, F.; Kolbe, M. Spontaneous formation of IpaB ion channels in host cell membranes reveals how Shigella induces pyroptosis in macrophages. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, M.M.; Higgins, D.E.; Tilney, L.G.; Portnoy, D.A. Role of listeriolysin O in cell-to-cell spread of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 2000, 68, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Boland, J.A.; Kocks, C.; Dramsi, S.; Ohayon, H.; Geoffroy, C.; Mengaud, J.; Cossart, P. Nucleotide sequence of the lecithinase operon of Listeria monocytogenes and possible role of lecithinase in cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun 1992, 60, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweten, R.K.; Parker, M.W.; Johnson, A.E. The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2001, 257, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Peraro, M.; van der Goot, F.G. Pore-forming toxins: ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, C.; Gaillard, J.L.; Alouf, J.E.; Berche, P. Purification, characterization, and toxicity of the sulfhydryl-activated hemolysin listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 1987, 55, 1641–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, D.A.; Tweten, R.K.; Kehoe, M.; Bielecki, J. Capacity of listeriolysin O, streptolysin O, and perfringolysin O to mediate growth of Bacillus subtilis within mammalian cells. Infect Immun 1992, 60, 2710–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Portnoy, D.A. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis in a strain expressing perfringolysin O in place of listeriolysin O. Infect Immun 1994, 62, 5608–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provoda, C.J.; Lee, K.D. Bacterial pore-forming hemolysins and their use in the cytosolic delivery of macromolecules. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2000, 41, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lett, M.C.; Sasakawa, C.; Okada, N.; Sakai, T.; Makino, S.; Yamada, M.; Komatsu, K.; Yoshikawa, M. virG, a plasmid-coded virulence gene of Shigella flexneri: identification of the virG protein and determination of the complete coding sequence. J Bacteriol 1989, 171, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasselon, T.; Mounier, J.; Prevost, M.C.; Hellio, R.; Sansonetti, P.J. Stress fiber-based movement of Shigella flexneri within cells. Infect Immun 1991, 59, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, N.; Morita, E.; Itoh, T.; Tanaka, A.; Nakaoka, M.; Osada, Y.; Umemoto, T.; Saitoh, T.; Nakatogawa, H.; Kobayashi, S.; et al. Recruitment of the autophagic machinery to endosomes during infection is mediated by ubiquitin. J Cell Biol 2013, 203, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maejima, I.; Takahashi, A.; Omori, H.; Kimura, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hamasaki, M.; Noda, T.; Isaka, Y.; et al. Autophagy sequesters damaged lysosomes to control lysosomal biogenesis and kidney injury. EMBO J 2013, 32, 2336–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, N.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Bertout, J.; Paz, I.; Freche, B.; Van Nhieu, G.T.; van der Goot, F.G.; Sansonetti, P.J.; Lafont, F. Shigella phagocytic vacuolar membrane remnants participate in the cellular response to pathogen invasion and are regulated by autophagy. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, E.M.; Vance, R.E. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature 2011, 477, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, J.; Gong, Y.N.; Lu, Q.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Shao, F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature 2011, 477, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, I.; Sachse, M.; Dupont, N.; Mounier, J.; Cederfur, C.; Enninga, J.; Leffler, H.; Poirier, F.; Prevost, M.C.; Lafont, F.; et al. Galectin-3, a marker for vacuole lysis by invasive pathogens. Cell Microbiol 2010, 12, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, K.V.; Cagnoni, A.J.; Croci, D.O.; Rabinovich, G.A. Targeting galectin-driven regulatory circuits in cancer and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncoso, M.F.; Elola, M.T.; Blidner, A.G.; Sarrias, L.; Espelt, M.V.; Rabinovich, G.A. The universe of galectin-binding partners and their functions in health and disease. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonekawa, Y.; Oikawa, K.; Bayarkhuu, B.; Kobayashi, K.; Saito, N.; Oikawa, I.; Yamada, R.; Chen, Y.H.; Oyanagi, K.; Shibasaki, Y.; et al. Magnetic control of membrane damage in early endosomes using internalized magnetic nanoparticles. Cell Struct Funct 2025, 50, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repnik, U.; Borg Distefano, M.; Speth, M.T.; Ng, M.Y.W.; Progida, C.; Hoflack, B.; Gruenberg, J.; Griffiths, G. L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester does not release cysteine cathepsins to the cytosol but inactivates them in transiently permeabilized lysosomes. J Cell Sci 2017, 130, 3124–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkoy, G.; Lamark, T.; Johansen, T. p62/SQSTM1: a missing link between protein aggregates and the autophagy machinery. Autophagy 2006, 2, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibenhener, M.L.; Babu, J.R.; Geetha, T.; Wong, H.C.; Krishna, N.R.; Wooten, M.W. Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 8055–8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerver, L.; Papadopoulos, C.; Liu, B.; Kravic, B.; Rota, G.; Brecht, L.; Veenendaal, T.; Polajnar, M.; Bluemke, A.; Ehrmann, M.; et al. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2QL1 coordinates lysophagy in response to endolysosomal damage. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e48014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kirchner, P.; Bug, M.; Grum, D.; Koerver, L.; Schulze, N.; Poehler, R.; Dressler, A.; Fengler, S.; Arhzaouy, K.; et al. VCP/p97 cooperates with YOD1, UBXD1 and PLAA to drive clearance of ruptured lysosomes by autophagy. EMBO J 2017, 36, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Ponpuak, M.; Mudd, M.H.; Kimura, T.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Mandell, M.; Bruun, J.A.; et al. TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2016, 39, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, N.; Itoh, T.; Omori, H.; Fukuda, M.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 2008, 19, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Claude-Taupin, A.; Gu, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Bissa, B.; Mudd, M.H.; Allers, L.; Pallikkuth, S.; Lidke, K.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and Removal. Dev. Cell 2020, 52, 69–87 e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, I.C.; Chen, H.L.; Lo, T.H.; Lin, W.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T. Cytosolic galectin-3 and -8 regulate antibacterial autophagy through differential recognition of host glycans on damaged phagosomes. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, T.L.; Wandel, M.P.; von Muhlinen, N.; Foeglein, A.; Randow, F. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature 2012, 482, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, H.; Mizushima, N. Diverse Cellular Roles of Autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2019, 35, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Rietz, H.; Hedlund, H.; Wilhelmson, S.; Nordenfelt, P.; Wittrup, A. Imaging small molecule-induced endosomal escape of siRNA. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.J.; O'Driscoll, G.; Silva, A.M.; Lazaro-Ibanez, E.; Gallud, A.; Wilson, J.T.; Collen, A.; Esbjorner, E.K.; Sabirsh, A. A high-throughput Galectin-9 imaging assay for quantifying nanoparticle uptake, endosomal escape and functional RNA delivery. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Bissa, B.; Brecht, L.; Allers, L.; Choi, S.W.; Gu, Y.; Zbinden, M.; Burge, M.R.; Timmins, G.; Hallows, K.; et al. AMPK, a Regulator of Metabolism and Autophagy, Is Activated by Lysosomal Damage via a Novel Galectin-Directed Ubiquitin Signal Transduction System. Mol Cell 2020, 77, 951–969 e959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Anderson, A.C.; Schubart, A.; Xiong, H.; Imitola, J.; Khoury, S.J.; Zheng, X.X.; Strom, T.B.; Kuchroo, V.K. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Niki, T.; Hirashima, M.; Horton, H. Galectin-9 binding to Tim-3 renders activated human CD4+ T cells less susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Blood 2012, 119, 4192–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmann, D.J.; Stefan, C.J.; Babst, M.; Emr, S.D. Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J Cell Biol 2003, 162, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmann, D.J.; Babst, M.; Emr, S.D. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 2001, 106, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babst, M.; Katzmann, D.J.; Snyder, W.B.; Wendland, B.; Emr, S.D. Endosome-associated complex, ESCRT-II, recruits transport machinery for protein sorting at the multivesicular body. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babst, M.; Katzmann, D.J.; Estepa-Sabal, E.J.; Meerloo, T.; Emr, S.D. Escrt-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for mvb sorting. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odorizzi, G.; Katzmann, D.J.; Babst, M.; Audhya, A.; Emr, S.D. Bro1 is an endosome-associated protein that functions in the MVB pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci 2003, 116, 1893–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.L.; Urbe, S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citri, A.; Yarden, Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Zastrow, M.; Sorkin, A. Mechanisms for Regulating and Organizing Receptor Signaling by Endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem 2021, 90, 709–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, A.; Futter, C.E.; Eden, E.R. EGF receptor trafficking: consequences for signaling and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haglund, K.; Shimokawa, N.; Szymkiewicz, I.; Dikic, I. Cbl-directed monoubiquitination of CIN85 is involved in regulation of ligand-induced degradation of EGF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 12191–12196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, A.; Gilestro, G.F.; Lanzardo, S.; Comoglio, P.M.; Migone, N.; Giordano, S. The endophilin-CIN85-Cbl complex mediates ligand-dependent downregulation of c-Met. Nature 2002, 416, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymkiewicz, I.; Kowanetz, K.; Soubeyran, P.; Dinarina, A.; Lipkowitz, S.; Dikic, I. CIN85 participates in Cbl-b-mediated down-regulation of receptor tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 39666–39672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubeyran, P.; Kowanetz, K.; Szymkiewicz, I.; Langdon, W.Y.; Dikic, I. Cbl-CIN85-endophilin complex mediates ligand-induced downregulation of EGF receptors. Nature 2002, 416, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zeng, X.; Kim, W.; Balasubramani, M.; Fortian, A.; Gygi, S.P.; Yates, N.A.; Sorkin, A. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination is required for EGF receptor degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 15722–15727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmann, D.J.; Odorizzi, G.; Emr, S.D. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.; Radulovic, M.; Stenmark, H. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, A.; McClure, M.; Huang, F.; Carter, R. Interaction of EGF receptor and grb2 in living cells visualized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy. Curr Biol 2000, 10, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surve, S.; Watkins, S.C.; Sorkin, A. EGFR-RAS-MAPK signaling is confined to the plasma membrane and associated endorecycling protrusions. J Cell Biol 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.I.; Roth, R.; Lin, Y.; Heuser, J.E. Plasma membrane deformation by circular arrays of ESCRT-III protein filaments. J Cell Biol 2008, 180, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollert, T.; Wunder, C.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hurley, J.H. Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature 2009, 458, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, N.; Sougrat, R.; Spurlin, T.A.; Hurley, J.H.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Dynamics of endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery during cytokinesis and its role in abscission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 4846–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.T.; Schuh, A.L.; Zheng, Y.; Quinney, K.; Wang, L.; Hanna, M.; Mitchell, J.C.; Otegui, M.S.; Ahlquist, P.; Cui, Q.; et al. Structural analysis and modeling reveals new mechanisms governing ESCRT-III spiral filament assembly. J Cell Biol 2014, 206, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell, M.A.Y.; Migliano, S.M.; Upadhyayula, S.; Bykov, Y.S.; Sprenger, S.; Pakdel, M.; Vogel, G.F.; Jih, G.; Skillern, W.; Behrouzi, R.; et al. Recruitment dynamics of ESCRT-III and Vps4 to endosomes and implications for reverse membrane budding. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.J.; Maiuri, P.; Lafaurie-Janvore, J.; Divoux, S.; Piel, M.; Perez, F. ESCRT machinery is required for plasma membrane repair. Science 2014, 343, 1247136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Shibata, H.; Suzuki, H.; Nara, A.; Ishidoh, K.; Kominami, E.; Yoshimori, T.; Maki, M. The ALG-2-interacting protein Alix associates with CHMP4b, a human homologue of yeast Snf7 that is involved in multivesicular body sorting. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 39104–39113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schwedler, U.K.; Stuchell, M.; Muller, B.; Ward, D.M.; Chung, H.Y.; Morita, E.; Wang, H.E.; Davis, T.; He, G.P.; Cimbora, D.M.; et al. The protein network of HIV budding. Cell 2003, 114, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, B.; Calistri, A.; Craig, S.; Popova, E.; Gottlinger, H.G. AIP1/ALIX is a binding partner for HIV-1 p6 and EIAV p9 functioning in virus budding. Cell 2003, 114, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Serrano, J.; Yarovoy, A.; Perez-Caballero, D.; Bieniasz, P.D. Divergent retroviral late-budding domains recruit vacuolar protein sorting factors by using alternative adaptor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 12414–12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, L.L.; Sreetama, S.C.; Sharma, N.; Medikayala, S.; Brown, K.J.; Defour, A.; Jaiswal, J.K. Mechanism of Ca(2)(+)-triggered ESCRT assembly and regulation of cell membrane repair. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vito, P.; Pellegrini, L.; Guiet, C.; D'Adamio, L. Cloning of AIP1, a novel protein that associates with the apoptosis-linked gene ALG-2 in a Ca2+-dependent reaction. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missotten, M.; Nichols, A.; Rieger, K.; Sadoul, R. Alix, a novel mouse protein undergoing calcium-dependent interaction with the apoptosis-linked-gene 2 (ALG-2) protein. Cell Death Differ 1999, 6, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trioulier, Y.; Torch, S.; Blot, B.; Cristina, N.; Chatellard-Causse, C.; Verna, J.M.; Sadoul, R. Alix, a protein regulating endosomal trafficking, is involved in neuronal death. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Cour, J.M.; Mollerup, J.; Berchtold, M.W. ALG-2 oscillates in subcellular localization, unitemporally with calcium oscillations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 353, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kawasaki, M.; Inuzuka, T.; Okumura, M.; Kakiuchi, T.; Shibata, H.; Wakatsuki, S.; Maki, M. Structural basis for Ca2+ -dependent formation of ALG-2/Alix peptide complex: Ca2+/EF3-driven arginine switch mechanism. Structure 2008, 16, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, H.; Chevallier, J.; Mayran, N.; Le Blanc, I.; Ferguson, C.; Faure, J.; Blanc, N.S.; Matile, S.; Dubochet, J.; Sadoul, R.; et al. Role of LBPA and Alix in multivesicular liposome formation and endosome organization. Science 2004, 303, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissig, C.; Lenoir, M.; Velluz, M.C.; Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R.; Overduin, M.; Gruenberg, J. Viral infection controlled by a calcium-dependent lipid-binding module in ALIX. Dev. Cell 2013, 25, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larios, J.; Mercier, V.; Roux, A.; Gruenberg, J. ALIX- and ESCRT-III-dependent sorting of tetraspanins to exosomes. J Cell Biol 2020, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claude-Taupin, A.; Jia, J.; Bhujabal, Z.; Garfa-Traore, M.; Kumar, S.; da Silva, G.P.D.; Javed, R.; Gu, Y.; Allers, L.; Peters, R.; et al. ATG9A protects the plasma membrane from programmed and incidental permeabilization. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, M.; Takahashi, T.; Shibata, H.; Maki, M. Mammalian ESCRT-III-related protein IST1 has a distinctive met-pro repeat sequence that is essential for interaction with ALG-2 in the presence of Ca2+. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2013, 77, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulovic, M.; Schink, K.O.; Wenzel, E.M.; Nahse, V.; Bongiovanni, A.; Lafont, F.; Stenmark, H. ESCRT-mediated lysosome repair precedes lysophagy and promotes cell survival. EMBO J 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowyra, M.L.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Naismith, T.V.; Hanson, P.I. Triggered recruitment of ESCRT machinery promotes endolysosomal repair. Science 2018, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadot, M.; Colmant, C.; Wattiaux-De Coninck, S.; Wattiaux, R. Intralysosomal hydrolysis of glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide. Biochem J 1984, 219, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.O.; Stromhaug, E.; Lovdal, T.; Seglen, O.; Berg, T. Use of glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide, a lysosome-disrupting cathepsin C substrate, to distinguish between lysosomes and prelysosomal endocytic vacuoles. Biochem J 1994, 300 ( Pt 1), 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, T.O.; Stromhaug, P.E.; Berg, T.; Seglen, P.O. Separation of lysosomes and autophagosomes by means of glycyl-phenylalanine-naphthylamide, a lysosome-disrupting cathepsin-C substrate. Eur J Biochem 1994, 221, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Fermin, A.; Vardhana, S.; Weng, I.C.; Lo, K.F.; Chang, E.Y.; Maverakis, E.; Yang, R.Y.; Hsu, D.K.; Dustin, M.L.; et al. Galectin-3 negatively regulates TCR-mediated CD4+ T-cell activation at the immunological synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 14496–14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.F.; Tsao, C.H.; Lin, Y.T.; Hsu, D.K.; Chiang, M.L.; Lo, C.H.; Chien, F.C.; Chen, P.; Arthur Chen, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; et al. Galectin-3 promotes HIV-1 budding via association with Alix and Gag p6. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, P.; Kravic, B.; Rota, G.; van den Boom, J.; Levantovsky, S.; Schulze, N.; Maspero, E.; Polo, S.; Behrends, C.; Meyer, H. Lysosomal damage sensing and lysophagy initiation by SPG20-ITCH. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 1556–1569 e1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, V.; Larios, J.; Molinard, G.; Goujon, A.; Matile, S.; Gruenberg, J.; Roux, A. Endosomal membrane tension regulates ESCRT-III-dependent intra-lumenal vesicle formation. Nat Cell Biol 2020, 22, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Molin, M.; Verolet, Q.; Colom, A.; Letrun, R.; Derivery, E.; Gonzalez-Gaitan, M.; Vauthey, E.; Roux, A.; Sakai, N.; Matile, S. Fluorescent flippers for mechanosensitive membrane probes. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujon, A.; Colom, A.; Strakova, K.; Mercier, V.; Mahecic, D.; Manley, S.; Sakai, N.; Roux, A.; Matile, S. Mechanosensitive Fluorescent Probes to Image Membrane Tension in Mitochondria, Endoplasmic Reticulum, and Lysosomes. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 3380–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goser, V.; Kehl, A.; Roder, J.; Hensel, M. Role of the ESCRT-III complex in controlling integrity of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol 2020, 22, e13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Gerl, M.J. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, S.A.; Gunther, G.; Tricerri, M.A.; Gratton, E. Methyl-beta-cyclodextrins preferentially remove cholesterol from the liquid disordered phase in giant unilamellar vesicles. J Membr Biol 2011, 241, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futerman, A.H.; Stieger, B.; Hubbard, A.L.; Pagano, R.E. Sphingomyelin synthesis in rat liver occurs predominantly at the cis and medial cisternae of the Golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem 1990, 265, 8650–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, M.; Pagano, R.E. Intracellular transport and metabolism of sphingomyelin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1991, 1082, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannun, Y.A.; Luberto, C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Okazaki, T. The role of sphingomyelin and sphingomyelin synthases in cell death, proliferation and migration-from cell and animal models to human disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1841, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandet, C.L.; Tan-Chen, S.; Bourron, O.; Le Stunff, H.; Hajduch, E. Sphingolipid Metabolism: New Insight into Ceramide-Induced Lipotoxicity in Muscle Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, C.J.; Kukulski, W.; Boyle, K.B.; Munro, S.; Randow, F. Transbilayer Movement of Sphingomyelin Precedes Catastrophic Breakage of Enterobacteria-Containing Vacuoles. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 2974–2983 e2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, A.; Sekizawa, Y.; Emoto, K.; Sakuraba, H.; Inoue, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Umeda, M. Lysenin, a novel sphingomyelin-specific binding protein. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 5300–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakrac, B.; Gutierrez-Aguirre, I.; Podlesek, Z.; Sonnen, A.F.; Gilbert, R.J.; Macek, P.; Lakey, J.H.; Anderluh, G. Molecular determinants of sphingomyelin specificity of a eukaryotic pore-forming toxin. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 18665–18677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakrac, B.; Kladnik, A.; Macek, P.; McHaffie, G.; Werner, A.; Lakey, J.H.; Anderluh, G. A toxin-based probe reveals cytoplasmic exposure of Golgi sphingomyelin. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 22186–22195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachi, R.; Uchida, Y.; Balakrishna, B.H.; Anderluh, G.; Kobayashi, T.; Taguchi, T.; Arai, H. Subcellular localization of sphingomyelin revealed by two toxin-based probes in mammalian cells. Genes Cells 2012, 17, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishitsuka, R.; Yamaji-Hasegawa, A.; Makino, A.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Kobayashi, T. A lipid-specific toxin reveals heterogeneity of sphingomyelin-containing membranes. Biophys J 2004, 86, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, K.B.; Ellison, C.J.; Elliott, P.R.; Schuschnig, M.; Grimes, K.; Dionne, M.S.; Sasakawa, C.; Munro, S.; Martens, S.; Randow, F. TECPR1 conjugates LC3 to damaged endomembranes upon detection of sphingomyelin exposure. EMBO J 2023, 42, e113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Mimuro, H.; Fukumatsu, M.; Kiga, K.; Piao, Z.; Ashida, H.; Yoshida, M.; Kakuta, S.; et al. A Tecpr1-dependent selective autophagy pathway targets bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaoui, A.; Mounier, J.; Prevost, M.C.; Sansonetti, P.J.; Parsot, C. icsB: a Shigella flexneri virulence gene necessary for the lysis of protrusions during intercellular spread. Mol Microbiol 1992, 6, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niekamp, P.; Scharte, F.; Sokoya, T.; Vittadello, L.; Kim, Y.; Deng, Y.; Sudhoff, E.; Hilderink, A.; Imlau, M.; Clarke, C.J.; et al. Ca(2+)-activated sphingomyelin scrambling and turnover mediate ESCRT-independent lysosomal repair. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wang, F.; Bhujabal, Z.; Peters, R.; Mudd, M.; Duque, T.; Allers, L.; Javed, R.; Salemi, M.; Behrends, C.; et al. Stress granules and mTOR are regulated by membrane atg8ylation during lysosomal damage. J Cell Biol 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Mathieu, C.; Kolaitis, R.M.; Zhang, P.; Messing, J.; Yurtsever, U.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Pan, Q.; et al. G3BP1 Is a Tunable Switch that Triggers Phase Separation to Assemble Stress Granules. Cell 2020, 181, 325–345 e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Boixet, J.; Kopach, A.; Holehouse, A.S.; Wittmann, S.; Jahnel, M.; Schlussler, R.; Kim, K.; Trussina, I.; Wang, J.; Mateju, D.; et al. RNA-Induced Conformational Switching and Clustering of G3BP Drive Stress Granule Assembly by Condensation. Cell 2020, 181, 346–361 e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, C.; Mangiarotti, A.; Vanhille-Campos, C.; Aylan, B.; Pellegrino, E.; Athanasiadi, N.; Fearns, A.; Rodgers, A.; Franzmann, T.M.; Saric, A.; et al. Stress granules plug and stabilize damaged endolysosomal membranes. Nature 2023, 623, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedersha, N.; Chen, S.; Gilks, N.; Li, W.; Miller, I.J.; Stahl, J.; Anderson, P. Evidence that ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-tRNA(i)(Met))-deficient preinitiation complexes are core constituents of mammalian stress granules. Mol Biol Cell 2002, 13, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Salinas, J.E.; Wheaton, R.P.; Poolsup, S.; Allers, L.; Rosas-Lemus, M.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Q.; Pu, J.; Salemi, M.; et al. Calcium signaling from damaged lysosomes induces cytoprotective stress granules. EMBO J 2024, 43, 6410–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenmark, H.; Vitale, G.; Ullrich, O.; Zerial, M. Rabaptin-5 is a direct effector of the small GTPase Rab5 in endocytic membrane fusion. Cell 1995, 83, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, G.; Rybin, V.; Christoforidis, S.; Thornqvist, P.; McCaffrey, M.; Stenmark, H.; Zerial, M. Distinct Rab-binding domains mediate the interaction of Rabaptin-5 with GTP-bound Rab4 and Rab5. EMBO J 1998, 17, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippe, R.; Miaczynska, M.; Rybin, V.; Runge, A.; Zerial, M. Functional synergy between Rab5 effector Rabaptin-5 and exchange factor Rabex-5 when physically associated in a complex. Mol Biol Cell 2001, 12, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, Y.; Takatsu, H.; Shin, H.W.; Nakayama, K. Gamma-adaptin interacts directly with Rabaptin-5 through its ear domain. J. Biochem. 2002, 131, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millarte, V.; Schlienger, S.; Kalin, S.; Spiess, M. Rabaptin5 targets autophagy to damaged endosomes and Salmonella vacuoles via FIP200 and ATG16L1. EMBO Rep 2022, 23, e53429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsu, F.; Kawasaki, A. Functions of Oxysterol-Binding Proteins at Membrane Contact Sites and Their Control by Phosphoinositide Metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 664788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, W.A.; Toulmay, A.; Balla, T. The functional universe of membrane contact sites. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Taskinen, J.H.; Olkkonen, V.M. Coordination of inter-organelle communication and lipid fluxes by OSBP-related proteins. Prog Lipid Res 2022, 86, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, A.; Tuymetova, G.; Tsiomenko, A.; Varnai, P.; Balla, T. A plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is generated by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type-III alpha: studies with the PH domains of the oxysterol binding protein and FAPP1. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, G.R.; Machner, M.P.; Balla, T. A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J Cell Biol 2014, 205, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejgaard, S.Y.; Presley, J.F. Arfs on the Golgi: four conductors, one orchestra. Front Mol Biosci 2025, 12, 1612531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Yuan, L.C.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Klausner, R.D. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 1989, 56, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.G.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Klausner, R.D. Guanine nucleotides modulate the effects of brefeldin A in semipermeable cells: regulation of the association of a 110-kD peripheral membrane protein with the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol 1991, 112, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.K.; Pfeifer, A.C.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Jackson, C.L. Dynamics of GBF1, a Brefeldin A-sensitive Arf1 exchange factor at the Golgi. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radulovic, M.; Wenzel, E.M.; Gilani, S.; Holland, L.K.; Lystad, A.H.; Phuyal, S.; Olkkonen, V.M.; Brech, A.; Jaattela, M.; Maeda, K.; et al. Cholesterol transfer via endoplasmic reticulum contacts mediates lysosome damage repair. EMBO J 2022, 41, e112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.X.; Finkel, T. A phosphoinositide signalling pathway mediates rapid lysosomal repair. Nature 2022, 609, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, M.; Ohsumi, Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, T.M.; Morano, K.A.; Scott, S.V.; Klionsky, D.J. Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. J Cell Biol 1995, 131, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Otomo, C.; Otomo, T. The autophagic membrane tether ATG2A transfers lipids between membranes. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.; Kotani, T.; Kawaoka, T.; Hirata, E.; Suzuki, K.; Nakatogawa, H.; Ohsumi, Y.; Noda, N.N. Atg2 mediates direct lipid transfer between membranes for autophagosome formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, D.P.; Yu, S.; Boggavarapu, V.; Kumar, N.; Lees, J.A.; Walz, T.; Reinisch, K.M.; Melia, T.J. ATG2 transports lipids to promote autophagosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol 2019, 218, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.; Ishii, Y.; Noda, N.N. Human ATG2B possesses a lipid transfer activity which is accelerated by negatively charged lipids and WIPI4. Genes Cells 2020, 25, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, T.; Reiche, S.; Straub, M.; Bredschneider, M.; Thumm, M. Autophagy and the cvt pathway both depend on AUT9. J Bacteriol 2000, 182, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, T.; Kim, J.; Huang, W.P.; Baba, M.; Tokunaga, C.; Ohsumi, Y.; Klionsky, D.J. Apg9p/Cvt7p is an integral membrane protein required for transport vesicle formation in the Cvt and autophagy pathways. J Cell Biol 2000, 148, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tito, S.; Almacellas, E.; Dai Yu, D.; Millard, E.; Zhang, W.; de Heus, C.; Queval, C.; Hervas, J.H.; Pellegrino, E.; Panagi, I.; et al. ATG9A and ARFIP2 cooperate to control PI4P levels for lysosomal repair. Dev. Cell 2025. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Chan, E.Y.; Hu, X.W.; Kochl, R.; Crawshaw, S.G.; High, S.; Hailey, D.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Tooze, S.A. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J Cell Sci 2006, 119, 3888–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, A.; Razi, M.; Dooley, H.C.; Robinson, D.; Weston, A.E.; Collinson, L.M.; Tooze, S.A. Dynamic and transient interactions of Atg9 with autophagosomes, but not membrane integration, are required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 2012, 23, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, S.; Omori, H.; Saitoh, T.; Sone, T.; Guan, J.L.; Akira, S.; Imamoto, F.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T. The LC3 recruitment mechanism is separate from Atg9L1-dependent membrane formation in the autophagic response against Salmonella. Mol Biol Cell 2011, 22, 2290–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, C.M.; Tan, X.F.; Lian, T.; Rana, M.S.; Zhou, W.; Christenson, E.T.; Lowry, A.J.; Faraldo-Gomez, J.D.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Jiang, J.; et al. Structure of Human ATG9A, the Only Transmembrane Protein of the Core Autophagy Machinery. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, K.; Kotani, T.; Tsutsumi, A.; Tsuji, T.; Mori, T.; Noshiro, D.; Sugita, Y.; Nomura, N.; Iwata, S.; Ohsumi, Y.; et al. Atg9 is a lipid scramblase that mediates autophagosomal membrane expansion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, A.R.; Chiduza, G.N.; Maslen, S.L.; Pye, V.E.; Joshi, D.; De Tito, S.; Jefferies, H.B.J.; Christodoulou, E.; Roustan, C.; Punch, E.; et al. ATG9A and ATG2A form a heteromeric complex essential for autophagosome formation. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 4324–4339 e4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Dikic, I. TBC1D5 and the AP2 complex regulate ATG9 trafficking and initiation of autophagy. EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, K.; Hao, F.; Fujita, N.; Tsuji, Y.; Oe, Y.; Araki, Y.; Hamasaki, M.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T. Atg9A trafficking through the recycling endosomes is required for autophagosome formation. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, 3781–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattera, R.; Park, S.Y.; De Pace, R.; Guardia, C.M.; Bonifacino, J.S. AP-4 mediates export of ATG9A from the trans-Golgi network to promote autophagosome formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E10697–E10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.K.; Itzhak, D.N.; Edgar, J.R.; Archuleta, T.L.; Hirst, J.; Jackson, L.P.; Robinson, M.S.; Borner, G.H.H. AP-4 vesicles contribute to spatial control of autophagy via RUSC-dependent peripheral delivery of ATG9A. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Wang, Y.; You, Z.; Liu, B.; Gao, J.; Liu, W. Mammalian Atg9 contributes to the post-Golgi transport of lysosomal hydrolases by interacting with adaptor protein-1. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 4027–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garcia, D.; Ortega-Bellido, M.; Scarpa, M.; Villeneuve, J.; Jovic, M.; Porzner, M.; Balla, T.; Seufferlein, T.; Malhotra, V. Recruitment of arfaptins to the trans-Golgi network by PI(4)P and their involvement in cargo export. EMBO J 2013, 32, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S.E.; Morgan, R.O. The annexins. Genome Biol 2004, 5, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, V.; Creutz, C.E.; Moss, S.E. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, V. Consensus peptide antibodies reveal a widespread occurrence of Ca2+/lipid-binding proteins of the annexin family. FEBS Lett. 1989, 258, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, R.A.; Ernst, J.D. Characterization of Ca2(+)-dependent phospholipid binding, vesicle aggregation and membrane fusion by annexins. Biochem J 1990, 266, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meers, P.; Mealy, T. Calcium-dependent annexin V binding to phospholipids: stoichiometry, specificity, and the role of negative charge. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 11711–11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junker, M.; Creutz, C.E. Ca(2+)-dependent binding of endonexin (annexin IV) to membranes: analysis of the effects of membrane lipid composition and development of a predictive model for the binding interaction. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 8930–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokumitsu, H.; Mizutani, A.; Minami, H.; Kobayashi, R.; Hidaka, H. A calcyclin-associated protein is a newly identified member of the Ca2+/phospholipid-binding proteins, annexin family. J Biol Chem 1992, 267, 8919–8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.J.; Merrifield, C.J.; Shao, D.; Ayala-Sanmartin, J.; Schorey, C.D.; Levine, T.P.; Proust, J.; Curran, J.; Bailly, M.; Moss, S.E. Annexin 2 binding to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate on endocytic vesicles is regulated by the stress response pathway. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 14157–14164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescher, U.; Ruhe, D.; Ludwig, C.; Zobiack, N.; Gerke, V. Annexin 2 is a phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate binding protein recruited to actin assembly sites at cellular membranes. J Cell Sci 2004, 117, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, T.; Kellner, R.; Parton, R.G.; Gruenberg, J. Specific release of membrane-bound annexin II and cortical cytoskeletal elements by sequestration of membrane cholesterol. Mol Biol Cell 1997, 8, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, N.J.; Kho, A.; Bacskai, B.J.; Perlmutter, S.L.; Hyman, B.T.; Brown, R.H., Jr. Dysferlin interacts with annexins A1 and A2 and mediates sarcolemmal wound-healing. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 50466–50473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittel, D.C.; Chandra, G.; Tirunagri, L.M.S.; Deora, A.B.; Medikayala, S.; Scheffer, L.; Defour, A.; Jaiswal, J.K. Annexin A2 Mediates Dysferlin Accumulation and Muscle Cell Membrane Repair. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, A.K.; Rescher, U.; Gerke, V.; McNeil, P.L. Requirement for annexin A1 in plasma membrane repair. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 35202–35207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, T.L.; Maeda, K.; Pezeshkian, W.; Sonder, S.L.; Haeger, S.C.; Gerke, V.; Simonsen, A.C.; Nylandsted, J. Annexin A4 and A6 induce membrane curvature and constriction during cell membrane repair. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouter, A.; Gounou, C.; Berat, R.; Tan, S.; Gallois, B.; Granier, T.; d'Estaintot, B.L.; Poschl, E.; Brachvogel, B.; Brisson, A.R. Annexin-A5 assembled into two-dimensional arrays promotes cell membrane repair. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonder, S.L.; Boye, T.L.; Tolle, R.; Dengjel, J.; Maeda, K.; Jaattela, M.; Simonsen, A.C.; Jaiswal, J.K.; Nylandsted, J. Annexin A7 is required for ESCRT III-mediated plasma membrane repair. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerdt, S.N.; Gerke, V. Annexin A2 is involved in Ca(2+)-dependent plasma membrane repair in primary human endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2017, 1864, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demonbreun, A.R.; Quattrocelli, M.; Barefield, D.Y.; Allen, M.V.; Swanson, K.E.; McNally, E.M. An actin-dependent annexin complex mediates plasma membrane repair in muscle. J Cell Biol 2016, 213, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, B.; Clement, C.C.; Wu, X.X.; Morozova, K.; Zanolini, D.; Follenzi, A.; Larocca, J.N.; Levon, K.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Rand, J.; et al. Annexin A2 binds to endosomes following organelle destabilization by particulate wear debris. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, R.; Clement, C.C.; Scharf, B.; Crisi, G.M.; Chitta, S.; Paget, D.; Purdue, P.E.; Cobelli, N.; Santambrogio, L. Endosomal damage and TLR2 mediated inflammasome activation by alkane particles in the generation of aseptic osteolysis. Mol Immunol 2009, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, W.W.; Yamamoto, H.; Mizushima, N. Annexins A1 and A2 are recruited to larger lysosomal injuries independently of ESCRTs to promote repair. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebstrup, M.L.; Sonder, S.L.; Fogde, D.L.; Heitmann, A.S.B.; Dietrich, T.N.; Dias, C.; Jaattela, M.; Maeda, K.; Nylandsted, J. Annexin A7 mediates lysosome repair independently of ESCRT-III. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1211498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.W.; Almeida, P.E.; Corrotte, M. Damage control: cellular mechanisms of plasma membrane repair. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emans, N.; Gorvel, J.P.; Walter, C.; Gerke, V.; Kellner, R.; Griffiths, G.; Gruenberg, J. Annexin II is a major component of fusogenic endosomal vesicles. J Cell Biol 1993, 120, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasserot-Golaz, S.; Vitale, N.; Umbrecht-Jenck, E.; Knight, D.; Gerke, V.; Bader, M.F. Annexin 2 promotes the formation of lipid microdomains required for calcium-regulated exocytosis of dense-core vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013, 200, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.; Heuser, J.; Stahl, P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 1983, 97, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, C.; Heuser, J.; Stahl, P. Endocytosis and intracellular processing of transferrin and colloidal gold-transferrin in rat reticulocytes: demonstration of a pathway for receptor shedding. Eur J Cell Biol 1984, 35, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.T.; Teng, K.; Wu, C.; Adam, M.; Johnstone, R.M. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 1985, 101, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijnen, H.F.; Schiel, A.E.; Fijnheer, R.; Geuze, H.J.; Sixma, J.J. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood 1999, 94, 3791–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.K.; Ngo, J.M.; Lehman, I.M.; Schekman, R. Annexin A6 mediates calcium-dependent exosome secretion during plasma membrane repair. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, M.; Carmo, N.B.; Krumeich, S.; Fanget, I.; Raposo, G.; Savina, A.; Moita, C.F.; Schauer, K.; Hume, A.N.; Freitas, R.P.; et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 19–30; sup pp 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, F.J.; Bebelman, M.P.; Jimenez, C.R.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Janssen, H.; Neefjes, J.; Knol, J.C.; de Goeij-de Haas, R.; Piersma, S.R.; Baglio, S.R.; et al. Quantifying exosome secretion from single cells reveals a modulatory role for GPCR signaling. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordjour, F.K.; Guo, C.; Ai, Y.; Daaboul, G.G.; Gould, S.J. A shared, stochastic pathway mediates exosome protein budding along plasma and endosome membranes. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, J.R.; Eden, E.R.; Futter, C.E. Hrs- and CD63-dependent competing mechanisms make different sized endosomal intraluminal vesicles. Traffic 2014, 15, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Okawa, Y.; Akter, S.; Ito, H.; Shiba, Y. Arf GTPase-Activating proteins ADAP1 and ARAP1 regulate incorporation of CD63 in multivesicular bodies. Biol Open 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, Y.; Randazzo, P.A. ArfGAP1 function in COPI mediated membrane traffic: currently debated models and comparison to other coat-binding ArfGAPs. Histol Histopathol 2012, 27, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y.; Randazzo, P.A. ArfGAPs: key regulators for receptor sorting. Receptors Clin Investig 2014, 1, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanna, C.E.; Goss, L.B.; Ludwig, C.G.; Chen, P.W. Arf GAPs as Regulators of the Actin Cytoskeleton-An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, Y.; Kametaka, S.; Waguri, S.; Presley, J.F.; Randazzo, P.A. ArfGAP3 regulates the transport of cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor in the post-Golgi compartment. Curr Biol 2013, 23, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, G.V.; Williamson, C.D.; Jarnik, M.; Bonifacino, J.S. Inhibition of endolysosome fusion increases exosome secretion. J Cell Biol 2023, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, F.J.; Bebelman, M.P.; George, A.E.; Couty, M.; Becot, A.; Palmulli, R.; Heiligenstein, X.; Sires-Campos, J.; Raposo, G.; Pegtel, D.M.; et al. ER membrane contact sites support endosomal small GTPase conversion for exosome secretion. J Cell Biol 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| molecule | recognition | Recruitment upon membrane damage | timing | reference |

| Galectin-3 | lumenal glycosylation | lysosomes, endosomes | 10-30min | [55,56,57,60] |

| Galectin-8 | lumenal glycosylation | lysosomes, endosomes | 30-60min | [73] |

| Galectin-9 | lumenal glycosylation | lysosomes,endosomes | 5-10min | [75,76,77] |

| LC3 | lysosomes, endosomes, autophagosomes | 30-60min | [55,56,57,60,73] | |

| Ubiquitin | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 30-60min | [67,103,158] | |

| UBE2QL1 | lysosomes | 30-60min | [67] | |

| ALIX | ALG2 binding under Ca2+, Gal-3 binding | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 30sec~ | [71,103,108,119,120,127] |

| ALG2 | Ca2+ | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 20sec~ | [108,112,206] |

| CHMP4B | ALIX/TSG101 | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 60sec~ | [71,108,119,120,127] |

| IST1 | ALG2 binding under Ca2+ | lysosomes | 60sec~ | [118,126] |

| SPG20 | Peroxidized lipids, IST1 | lysosomes | 5min~ | [126] |

| ITCH | SPG20 binding | lysosomes | 15min | [126] |

| Lysenin | Sphingomyelin exposure to cytosol | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 5-40min | [138,139] |

| EqtSM | Sphingomyelin exposure to cytosol | lysosomes, endosomes, plasma membrane | 2min~ | [142,147] |

| TECPR1 | Sphingomyelin exposure to cytosol | bacteria-positive autophagosomes, lysosomes | 10-30min | [144,145] |

| G3BP1/2 | Stress granules, Slightly overlap with damaged lysosomes | 30sec~ | [148,151,153] | |

| Rabaptin-5 | (Rab4,Rab5)a | endosomes | 30min | [158] |

| PI4KIIA | lysosomes | 10min | [169] | |

| SidM | PI4P | lysosomes | 5-10min | [168,178] |

| ORP9-11 | PI4P | lysosomes | 10min | [169] |

| OSBP | PI4P, (Arf1)a | lysosomes | 6-30min | [168,169] |

| ATG2A | lysosomes | 10 min | [169] | |

| ATG9A | Ca2+ | lysosomes, plasma membrane | 15-45min | [117,178] |

| Annexin A1,2,4,5,6,7 | Ca2+ , negative-charged lipids | plasma membrane | 2-50 sec | [204,205,206,207,208] |

| Annexin A1, 2, 6,7 | Ca2+ , negative-charged lipids | MVBs, lysosomes, plasma membrane after fusion | 10-30min | [209,211,212,221] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).