1. Introduction

The Collatz map

is defined by

The (forward) Collatz conjecture asserts that every positive integer eventually reaches 1 under iteration of

T. Despite its elementary form, the problem has resisted resolution since 1937. Classical analyses organize trajectories by parity patterns, stopping times, and modular constraints [

2,

3], and extensive surveys chart the landscape of techniques and phenomena [

1,

4,

5]. More recently, ergodic/probabilistic methods have established almost-sure boundedness in a density sense [

6].

This paper presents a novel and direct arithmetic framework for the system based on two additional simple observations:

- (1)

Combined lens mod 18. Because the reverse step divides by 3, one needs the mod-18 lift to make the child well-defined; pairing this with parity yields a single operational lens mod . On this lens, both the forward first step and any admissible reverse first step land in the same three residue classes , and these residue classes alone determine the next odd class.

- (2)

Forward/Reverse equivalence at the middle even. For every live odd n () there exists an admissible k with , so the forward and reverse procedures share the same middle decision.

From these facts we see that advancing k by 2 rotates the mod-18 middle-even class , which cycles the available child classes . Thus the terminating option recurs regularly in the rotation; it is available but not forced. This periodic availability, together with parity (every even halves to odd), ensures that the forward and reverse frameworks align and that the global dynamics converge into .

We also formulate a general taxonomy for other

q:

rotation (no dead classes when 2 generates all units),

splitting (proper order of 2 in the unit group), and

collapse (composite

q with many nonunits). The

case is the rotation extreme: there are no dead classes, and the mod-18 gate is fully deterministic. Background and complementary perspectives may be found in [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

2. Prior Work and Novelty

Prior work.

Parity encodings, stopping-time statistics, and modular constraints underpin much of the modern Collatz literature [

2,

3]. Authoritative surveys and monographs systematize these tools and document many partial results and heuristics [

1,

4,

5]. More recently, density-based approaches have shown that almost all orbits attain almost bounded values [

6]. These contributions provide powerful average-case control and a broad toolkit for congruence reasoning, but they do not yield a single, deterministic local rule that simultaneously governs the forward and reverse steps at the same arithmetic resolution.

Novelty.

Our contribution is a single-lens, local rule that completely determines the next odd class from the middle even that is shared by forward and reverse functions:

We use mod 18 as the operational lens: parity × the division-by-3 lift. Mod 9 supplies the minimal “division-by-3 memory” to preserve residues, but because the middle-even is always even, the dynamics close naturally in mod 18.

We prove forward/reverse middle-even congruence: for every live odd n and for all admissible doublings k, the reverse middle-even lies in the same three residues as the forward middle-even . Thus forward and reverse dynamics are congruent at the middle even: they always meet at one of the residues , and from this shared gate the next odd class is determined identically in both directions.

We deduce a finitely bound terminating-child property from : even-k increments rotate the residue classes with period 3, determining a hit of the terminating residue class 10 in at most two steps.

These local facts yield concise global consequences: no nontrivial odd cycles and global inclusion (every integer’s trajectory enters ).

Conceptually, the framework isolates the interaction of

powers of two (doubling) with the prime 3 in a single arithmetic object (mod 18), turning Collatz dynamics into a short residue computation rather than a long-range statistical argument; cf. [

1,

4,

5].

3. Definitions

Definition 1 (System parameter

q)

. Fix an odd integer . The reverse Collatz transform at order q is

well-defined exactly for those satisfying the admissibility congruence . The classical Collatz case is .

Two arithmetic lenses are attached to q:

For , these combine as a single operational lens modulo .

Definition 2 (Forward Collatz function)

. The (one-step) forward Collatz map is

Definition 3 (Reverse Collatz function (

))

. Given an odd integer n, a doubling count is admissible

if (equivalently, forces k even, and forces k odd). For any admissible k, the reverse Collatz function

produces the odd child

If is the minimal admissible doubling count, then is called the first child

of n.

In particular, is the smallest admissible odd: it satisfies the condition with and yields . Thus 1 is the unique self-parent and the root origin of the reverse tree; every odd child in the system is a descendant of an admissible k-function applied to 1.

Definition 4 (Middle-even values)

. For an odd integer n, define the forward middle-even

value

For the reverse step with admissible doubling count (i.e., ), define the reverse middle-even

value

Both and are even and are read modulo 18 to determine the child’s odd class via the fixed gate , , in the reverse function.

Definition 5 (Parent (reverse Collatz, )). An odd integer n is a parent . If (an odd multiple of 3), it has no admissible doubling and is a terminating parent. Otherwise (), n is live and has at least one admissible k.

Definition 6 (Child (reverse Collatz,

))

. Given a parent n and an admissible , the corresponding child

is

For a fixed n, admissible k have fixed parity and are exactly with . As k increases by , the middle-even residue cycles (Lemma 4); under the fixed gate , , , the children of n therefore occur in the deterministic class rotation

Definition 7 (First child)

. For a live parent n, let be the minimal admissible doubling count. The first child

of n is

Definition 8 (Admissible doubling and child)

. Let n be odd. A doubling count is admissible

if

For any admissible k, the reverse child

is

By Lemma 2, the set of admissible k for a fixed odd n has fixed parity (even if , odd if ), and hence preserves admissibility.

4. The Mod 6 Classification for Odd Integers

All odd integers fall into three residue classes modulo 6:

-

C0: (odd multiples of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): No admissible k with exists, so has no reverse parent.

-

C1: (two higher than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): , so admissible

k are

odd. The first admissible is

. One doubling gives

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

-

C2: (two lower than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): , so admissible

k are

even. The first admissible is

, yielding

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

doublings.

Lemma 1 (C0 is terminating under the reverse step)

. If (i.e., n is an odd multiple of 3), then for every ,

In particular, the class C0 has no admissible reverse child.

Proof. If then for all , hence , which is not divisible by 3. □

Corollary 1 (Forward exit from C0). If , then in the forward map with the next odd m satisfies , hence .

Proof. If then , contradicting . □

Lemma 2 (Admissibility parity)

. Let n be odd. The congruence has a solution iff . In that case the parity of k is fixed by :

In particular, whenever k is admissible, so is .

Proof. Since , the condition is . If this forces (so k even); if it forces (so k odd); if there is no solution. Adding 2 to k preserves and hence admissibility. □

5. Mod 18 Deterministic Residue vs. n

Proposition 1 (Deterministic child-class decision via mod 18)

. In the Reverse Collatz function, and for odd n, the residue of the middle even in alone determines the child’s odd class, both forward and reverse. This gives a one-step, local rule independent of trajectory history [1,2,3]. Via the fixed gate,

the child’s odd class is determined locally by the middle-even residue. Equivalently, the child’s odd class depends only on the residue of the middle even modulo 18, not on the history of the trajectory.

5.1. Residue Lens (Mod )

Given a live class, we lift one step deeper:

Lemma 3 (Gate 10 produces a C0 child)

. If an admissible middle even satisfies , then

so the reverse child is in C0 (an odd multiple of 3).

Proof. Write . Then . □

Remark 1 (Forward mod 6 lifts to mod 18 in the first step)

. For odd n, the forward middle-even value carries the mod 6 residue of n to a residue mod 18:

Thus the first forward step lifts

the mod 6 classification to the combined lens mod (parity + residue), and the child’s class is then read off by the fixed gate , , .

The quotient

is the

child, well-defined modulo

. The map

determines whether the trajectory continues or collapses into a terminating residue.

6. Microcycles and Lifted k with Tables

Lemma 4 (Rotation under

in mod 18)

. If k is admissible for odd n (), then

Moreover , and hence

Proof. Admissible are even and , so only occur modulo 18. For admissible k, ; computing mod 18 gives , , , which establishes the 3-cycle. □

Microcycles: function and reason. Fix a live odd parent

n (

). For the Reverse Collatz Function, all admissible reverse doublings for

n share the same parity (by admissibility parity), so from the minimal admissible count

we may advance by steps of 2:

. By Lemma 4, each

step multiplies the reverse middle-even by 4 modulo 18, sending

and hence rotating the child classes

.

cycling through

(mod 18). By the common mod-18 gate (Lemma 6), these three middle-even classes deterministically select the child odd classes

, in that order. Thus every fixed parent

n generates a

k-lifted microcycle of children:

Moreover, by the forward–reverse middle-even equivalence (Lemma 7), there exists an admissible

k for which

, so the reverse microcycle is aligned with the residue one sees on the forward side.

Why two tables (by n and by residue). The decision rule depends only on the mod-18 middle-even class together with the fixed parity of admissible k. Hence one may work either with a concrete integer n or directly with its residue . The paired tables illustrate both viewpoints—the integer view (full n) and the residue view (r)—and they agree entry-by-entry in the mod-18 column and the first-child class.

How to read the tables. Each row advances k by (preserving admissibility). Read off: (i) the rotating mod-18 middle-even class , (ii) the corresponding child class , and (iii) the 3-step periodicity. The first appearance of residue certifies an accessible termination to within at most two lifts from .

Tables.

Example

(reverse step, even

k; here

,

):

Example

(reverse step, odd

k; here

,

):

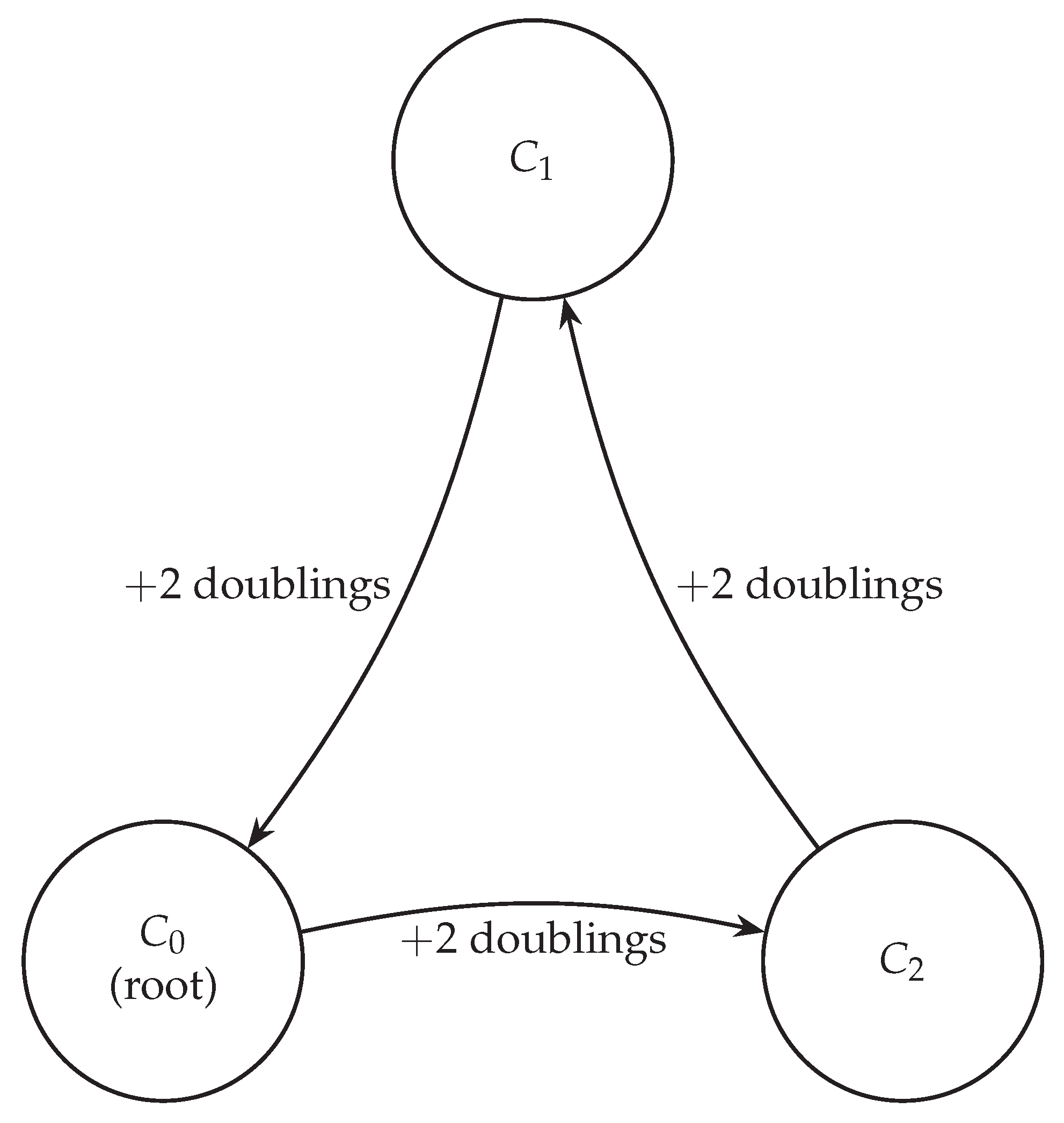

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate (Collatz case ). Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate (Collatz case ). Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

Corollary 2 (Linear segment pattern 19–35)

. List the odd integers n from 19 to 35. For each n, take its class (mod 6), its residue (mod 18), the reverse middle-even at the minimal admissible

doubling (so for , for , none for ), and the class of the first child when defined. The resulting first-child classes occur in the order

i.e., (none), (none), (none), .

Explanation. For each n: determine its class by (C0: 3, C1: 5, C1: 1). If , no admissible reverse step exists. If (resp. ), take (resp. ) by admissibility parity. Then use the reverse mod-18 gate (Lemma 6): with the fixed mapping . Evaluating these nine cases yields the displayed sequence . □

Remark 2 (Periodicity of the linear pattern)

. The assignment “first-child class of n” depends only on and on the parity of , which in turn depends only on . Since listing odd integers in order cycles their residues through and then repeats, the 9-term pattern

repeats indefinitely: it has period 18 in n (i.e., period 9 when restricted to consecutive odd integers).

Even distribution of first-child classes (per residue cycle).

Over any run of nine consecutive odd integers, the residues cycle

(reindexed for clarity). Using admissibility parity for

and the fixed middle-even gate (Lemma 6, Lemma 4), the

first-child class for each entry in this 9-term cycle follows the pattern

where “×” marks a terminating parent (

has no admissible reverse step).

Consequence. Among the six live residues in the cycle (the three parents excluded), the first-child classes occur exactly twice each: two , two , and two . Hence, restricted to odd , the first-child classes are equidistributed with frequency each, and the 9-term pattern repeats periodically with period 18 in n (period 9 when listing consecutive odd integers).

7. Forward Mod 6 and Lift to Mod 18

Lemma 5 (Forward middle-even residues mod 18)

. For odd n,

Proof. Check the three odd residues modulo 6:

Thus

(mod 18) according as

(mod 6). □

7.1. Reverse Step: Admissible k (Odd/Even) and Valid Children

Lemma 6 (Reverse middle-even residues mod 18)

. Let n be odd and admissible, with . Then

and the child class is determined by the common mod-18 gate

Proof. Admissibility means

. Modulo 9, the residues

are exactly

. Among

even residues modulo 18, these lift uniquely to

Hence

(mod 18). Moreover,

so the child class is chosen by the stated gate. □

Forward–reverse equivalence.

Lemma 7 (Middle-even equivalence mod 18)

. If , there exists an admissible with

Proof. Work modulo 9. Since

,

n is a unit mod 9. We want

, i.e.

Because

has order 6 and is generated by 2, its even powers are exactly

and its odd powers are

. Since

, the target residue lies in the required parity coset (even if

, odd if

), so there exists

k with

. As

and

are both even, their difference is divisible by 9 and by 2, hence by

, yielding

. □

8. Forward–Reverse Equivalence

Proposition 2 (Two-step equivalence at the middle even). For each live odd n (), there exists an admissible reverse step whose middle-even residue equals the forward middle-even residue (Lemma 7). Moreover, for any admissible step the middle even lies in the same three-way gate (mod 18); in the matching case they select the same child class. In particular, every admissible k lands in one of and is decoded by the same gate , , .

Corollary 3 (Class agreement at the gate). For any odd n and any admissible k with , the forward and reverse steps select the same child class at the middle-even gate.

Proof. By Proposition 2, , and by the fixed gate mapping , , , both directions choose the same class. □

Forward gate. By Lemma 5, for odd

n we have

with the residue determined by

, and these three residues map to the child classes via

,

,

.

Reverse gate. For any admissible

k, Lemma 6 gives

and the

same mapping

,

,

determines the child class.

Remark 3. The first child uses and returns to 1 as above. Larger t give other (valid) reverse children (e.g. ), but the minimal-child dynamics that drive our arguments are governed by at , which anchors the system at the loop and shows that 1 is always a fixed reference point. This consistency ensures the reverse tree connects globally while still allowing infinitely many valid children.

Corollary 4 (Deterministic class agreement). For any odd n and any admissible k, the child class obtained from the forward first step equals the child class obtained from the reverse step . For live n, there exists an admissible k with .

9. The Trivial Loop from : Reverse and Forward Views

Lemma 8 (1 is and has even admissible doublings). Since , the integer 1 lies in class . Admissibility for the reverse step requires . With and , this gives , hence k is even. The minimal admissible doubling count is .

Proposition 3 (First child of 1 equals 1)

. With , the reverse child of is

so the first child of 1 is 1 again. Consequently, under the reverse map with minimal admissible doubling, is a fixed point in class .

Remark 4 (Consistency with the forward picture: the

loop)

. From the forward side, starting at 1,

which is the well-known loop. Thus the reverse fixed point at (with minimal ) corresponds exactly to the unique forward cycle.

Remark 5 (Other even doublings)

. Any admissible doubling for has the form with , yielding

The first child

uses and returns to 1 as above. Larger t give other (valid) reverse children (e.g. ), but for our purposes the minimal-child dynamics at are governed by , which identifies 1 as a fixed point and ensures consistency with the forward loop.

10. No Nontrivial Cycles

Lemma 9 (Infinite children; unique parent). In the Collatz function, each parent has infinitely many children, and each child has exactly one parent.

Proof. A parent has infinitely many children because, for any live odd n, the admissible exponents are exactly with (Lemma 2). Each t produces a distinct odd child , hence there are infinitely many children. A child has exactly one parent because in the forward direction is always even, and repeated halving continues until the first odd integer appears. That odd is unique, since all values between are even, and no two odd integers share the same double, the parent is uniquely determined. □

Lemma 10 (Reverse bound: unique path to ). Build the reverse graph level by level starting at 1 as follows: a child of an odd parent m is any odd n whose forward step (form and halve until the first odd appears) lands at m. Assign each child depth one more than its parent’s depth. Then every node that appears in this reverse construction has a unique finite path to 1 (its parent chain), hence its reverse position is completely determined by the rule “each child has exactly one parent.”

Proof.

Existence (finite path). By construction, 1 is at depth 0, serving as the unique root. It has no parent apart from its trivial self-loop, and thus is not itself a child. Whenever a child n is added under a parent m, we set . Hence every node is created at some finite depth and admits a finite parent chain that ultimately terminates at 1.

Uniqueness (only one path). Each child has exactly one parent by the step rule: from n, is even and the first odd reached by halving is the parent; there is no other odd between n and that parent. Hence, for any node x at depth d, its parent at depth is uniquely determined; repeating this d times yields a single chain back to 1 with no alternatives. Therefore the path to 1 is unique. □

Corollary 5 (Reverse tree structure). Within this construction the reverse graph is a rooted tree with root 1: every node has in-degree 1 (unique parent) and a unique simple path to 1.

Proposition 4 (Forward orbit equals reverse parent chain)

. Let be odd. Define its parent to be the first odd reached by the forward rule: form and divide by 2 until odd. Then the forward odd subsequence generated by T satisfies

In particular, the forward odd orbit is exactly the reverse parent chain read in reverse order.

Proof. By definition of , is the first odd encountered after applying and halving. But this is precisely how the next odd iterate of T is defined. Hence . □

Corollary 6 (Unique parentage ⇒ forward convergence). By Lemma 9 each odd has a unique parent; by Corollary 5 the reverse graph is a rooted tree with root 1. Therefore, every parent chain is finite and terminates at 1. By Proposition 4, every forward odd orbit coincides with that chain read backward. Hence every forward trajectory reaches 1; no odd cycles or runaways can occur.

Corollary 7 (Elimination of loops, merges, and forward divergence). Assume the step rules of the function and the two facts established above: (i) every parent has infinitely many admissible children; (ii) every child has exactly one parent. Together with the reverse-tree bound that every path begins at 1, the following hold.

(A) No loops. A loop would require a parent producing a child, which produces a child, and so on, eventually producing a child equal to the original parent. But each child has a unique parent and every node’s parent chain begins at 1. If a loop existed, the parent chain would never reach 1, contradicting Lemma 10. Hence loops cannot exist.

(B) No forward runaways. Suppose some starting odd n under the forward function (apply , then halve until odd, repeat) never reaches 1. In the reverse picture, n has a unique parent, that parent has a unique parent, and so on; by Lemma 10 this parent chain begins at 1, so it is finite. The forward trajectory is just the same chain read in inverse, so it must terminate at 1 in finitely many steps. An infinite forward “runaway” would contradict this, so forward divergence cannot occur.

(C) No merges (no reverse convergence).

If two distinct reverse paths converged, some child would have two different parents. This contradicts the uniqueness of the parent. Therefore distinct reverse branches never merge.

11. Higher q: Dead-Class Existence and Coverage

Lemma 11 (Dead-class criterion for general

q)

. Let be odd and let . The reverse step

is possible for some if and only if r is a unit modulo q and . Equivalently, the class of r is

terminating if ;

dead if either or r is a unit with ;

live otherwise, with the least s.t. .

Proof. The reverse integrality condition is , i.e. . If then so no k exists (terminating). If the congruence has no solution (no inverse). If r is a unit, write : such k exists iff lies in the cyclic subgroup generated by 2. Minimality of k is by definition. □

Corollary 8 (Coverage criterion). For a fixed odd q, there are no dead classes (all nonzero residues are live) if and only if . In particular, for primes p where 2 is a primitive root (e.g. ), every is live; for moduli such as , proper containment or many nonunits ensures the existence of dead classes.

| q |

class lens

(mod )

|

residue lens

(mod )

|

live

classes

|

terminating

classes

|

dead/invalid

residues

|

| 3 |

mod 6 |

mod 18 |

2 |

1 |

0 (rotation) |

| 5 |

mod 10 |

mod 50 |

4 |

1 |

0 (rotation) |

| 7 |

mod 14 |

mod 98 |

3 |

1 |

3 (splitting) |

| 9 |

mod 18 |

mod 162 |

6 |

1 |

2 (splitting) |

| 15 |

mod 30 |

mod 450 |

4 |

1 |

10 (collapse) |

| 21 |

mod 42 |

mod 882 |

6 |

1 |

14 (collapse) |

Remark 6 (Labels: rotation, splitting, collapse). “Rotation” indicates (no dead classes); “splitting” indicates is a proper subgroup of the units (some live, some dead); “collapse” highlights that many residues are nonunits (composite q), so most classes are dead. These agree with the annex tables for .

12. All Integers Included for

Lemma 12 (Global inclusion at ). For there are no dead classes: every odd n satisfies either (terminating) or admits an admissible reverse doubling k with . Since every even integer halves to the odd layer, all positive integers lie in the system.

Proof. Modulo 3, and , so Corollary 8 gives no dead classes: every is live, and (odd multiples of 3) is terminating. Thus every odd is either live or terminating. Any even N can be repeatedly halved to an odd n, placing N into the same framework. The operational child-class decision is made at the middle even via the common mod-18 gate , , (Lemmas 5, 6), and forward–reverse equivalence (Proposition 2) maintains consistency. Hence all integers are included in the system. □

13. Final Theorem

Theorem 1 (Resolution of the dynamics in the system). Combining Lemmas 5, 6, 7, 1, 12, Corollary 5, and Corollary 6, every forward trajectory enters the loop .

Proof (structured).

Step 1: Common middle-even gate for forward and reverse. By Lemma 5, for odd n the forward middle-even lies in and selects the next child class via the fixed gate , , . By Lemma 6, every admissible reverse middle-even lies in the same three residues with the same gate. Lemma 7 guarantees that for each live odd n there is an admissible k with , so forward and reverse agree at the gate.

Step 2: Unique parentage ⇒ reverse tree. By Lemma 9 each odd has exactly one parent; hence, by Corollary 5, the reverse graph is a rooted tree with root 1.

Step 3: All integers lie in the system; is terminating. Lemma 12 shows that for there are no dead classes: every odd is either terminating () or live (admits a reverse step). Lemma 1 shows that does not have a reverse child. Thus every odd integer is either the root 1, a node of the reverse tree (hence with a finite parent chain to 1), or a terminating parent in .

Step 4: Forward convergence. Reading edges forward in the tree gives the unique forward path from each node to 1. Since all runaways and odd cycles are excluded, the only forward cycle remaining is the trivial loop . Therefore, every forward trajectory converges into . □

14. Conclusions

This work recasts the dynamics of into a fully arithmetic framework. The class lens (mod 6) organizes the odd layer, while the operational middle-even lens (mod 18) unifies parity with the division-by-3 constraint and produces a deterministic local gate . On the reverse side, admissibility is read purely modulo q (here ), and k-rotation in mod 18 cycles the available child classes , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes. The forward–reverse middle-even equivalence shows that both directions pass through the same gate and therefore select the same child class. Because has no dead classes (every odd is either live or terminating), every integer lies in this system, and the reverse graph has the structure of a tree with root 1, ensuring unique parentage and excluding nontrivial cycles. As assembled in Theorem 1, every forward trajectory converges to the loop .

Historically, the Collatz problem was studied through probabilistic heuristics, stopping-time statistics, and ergodic averages [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The present treatment is purely arithmetic: by partitioning odd integers into residue classes, aligning forward and reverse dynamics through their common middle-even residues, and establishing unique parentage together with the exclusion of odd cycles, the dynamics become fully deterministic at each step. In this setting, the “conjecture” in the classical case ceases to be a conjecture: within this operator framework it is a theorem, every trajectory enters

. A constructive arithmetic account of offsets, block coverage, and recursive lifts is developed separately in the companion supplement [

7].

Outlook. The annexed tables for higher q exhibit the rotation/splitting/collapse trichotomy of live classes dictated by . Although these higher-order lenses are not needed for resolution, they clarify why dead classes arise for and, conversely, why their absence at implies global coverage of the integers in the classical Collatz setting.

Appendix A. Annex: Tables for q=x

How to read the annex tables (odds q=3 through q=21)

Each table lists, for a fixed odd modulus q, the behavior of odd classes under the reverse Collatz step. The columns are:

raw odd : the odd residue class in the parity lens;

: the residue that controls divisibility by q;

: the minimal admissible doubling count solving , equivalently ;

-

status:

- –

terminating if (odd multiples of q have no reverse parent);

- –

dead if (so n is not invertible mod q), or if r is a unit but (no k with );

- –

live if r is a unit and ; then is the least with .

The following subsections list the tables for .

References

- J. C. Lagarias, The 3x + 1 Problem and Its Generalizations, Amer. Math. Monthly 92 (1985), no. 1, 3–23. [CrossRef]

- R. Terras, A stopping time problem on the positive integers, Acta Arith. 30 (1976), 241–252.

- C. J. Everett, Iteration of the number-theoretic function f(2n) = n, f(2n + 1) = 3n + 2, Advances in Mathematics 25 (1977), 42–45. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Wirsching, The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n + 1 Function, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1681, Springer, 1998.

- J. C. Lagarias (ed.), The Ultimate Challenge: The 3x + 1 Problem, American Mathematical Society, 2010.

- T. Tao, Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded values, arXiv:1909.03562 (2019).

- M. Spencer, Arithmetic Offsets and Recursive Coverage Patterns in the Collatz Function, Supplement to Spencer (2025), Manuscript, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).