Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Outcome Assessment

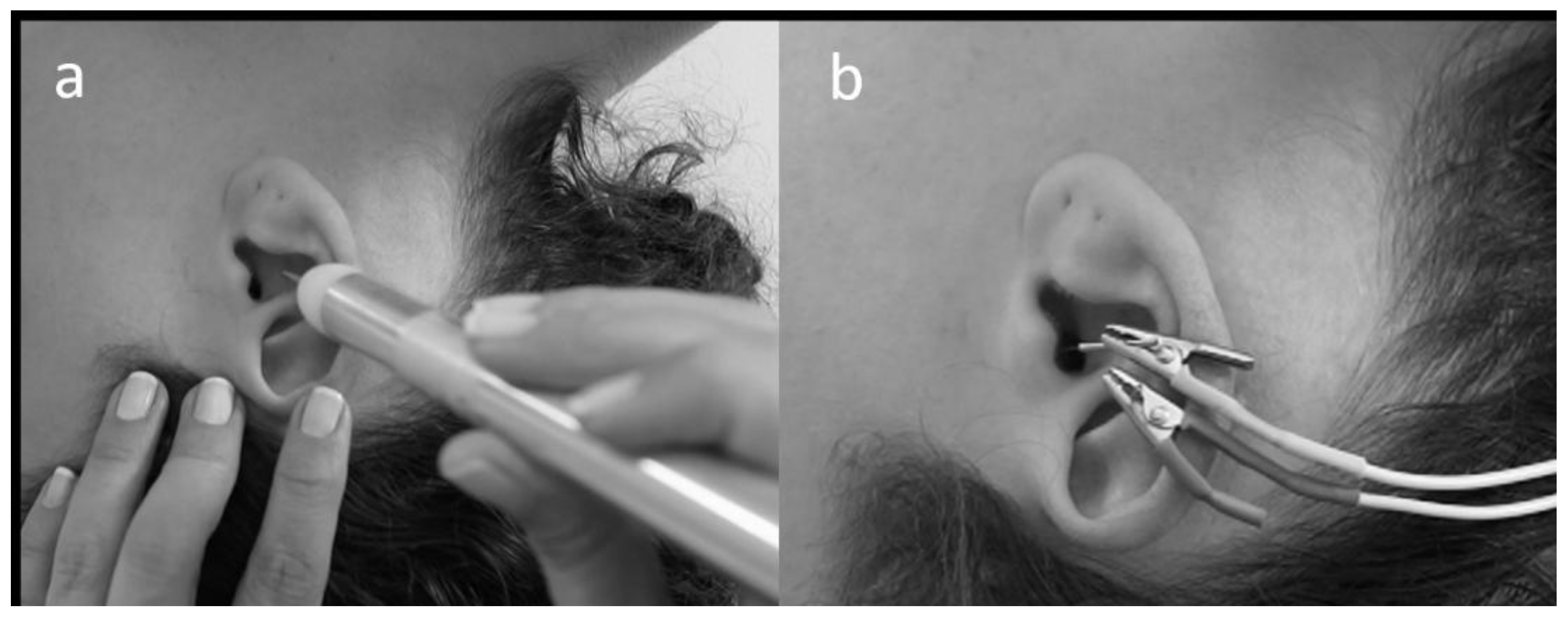

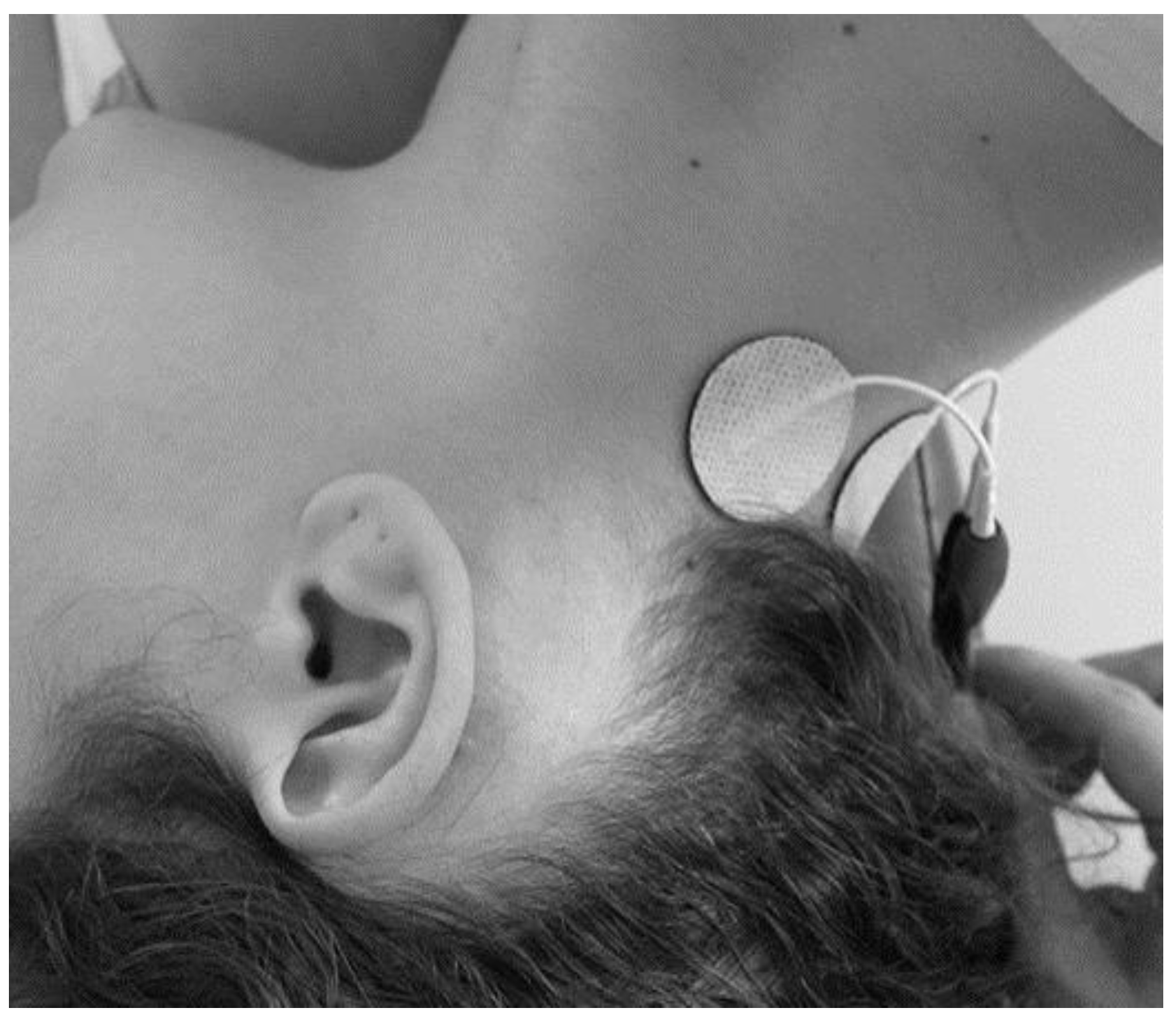

2.3. aVNS and TENS Protocols

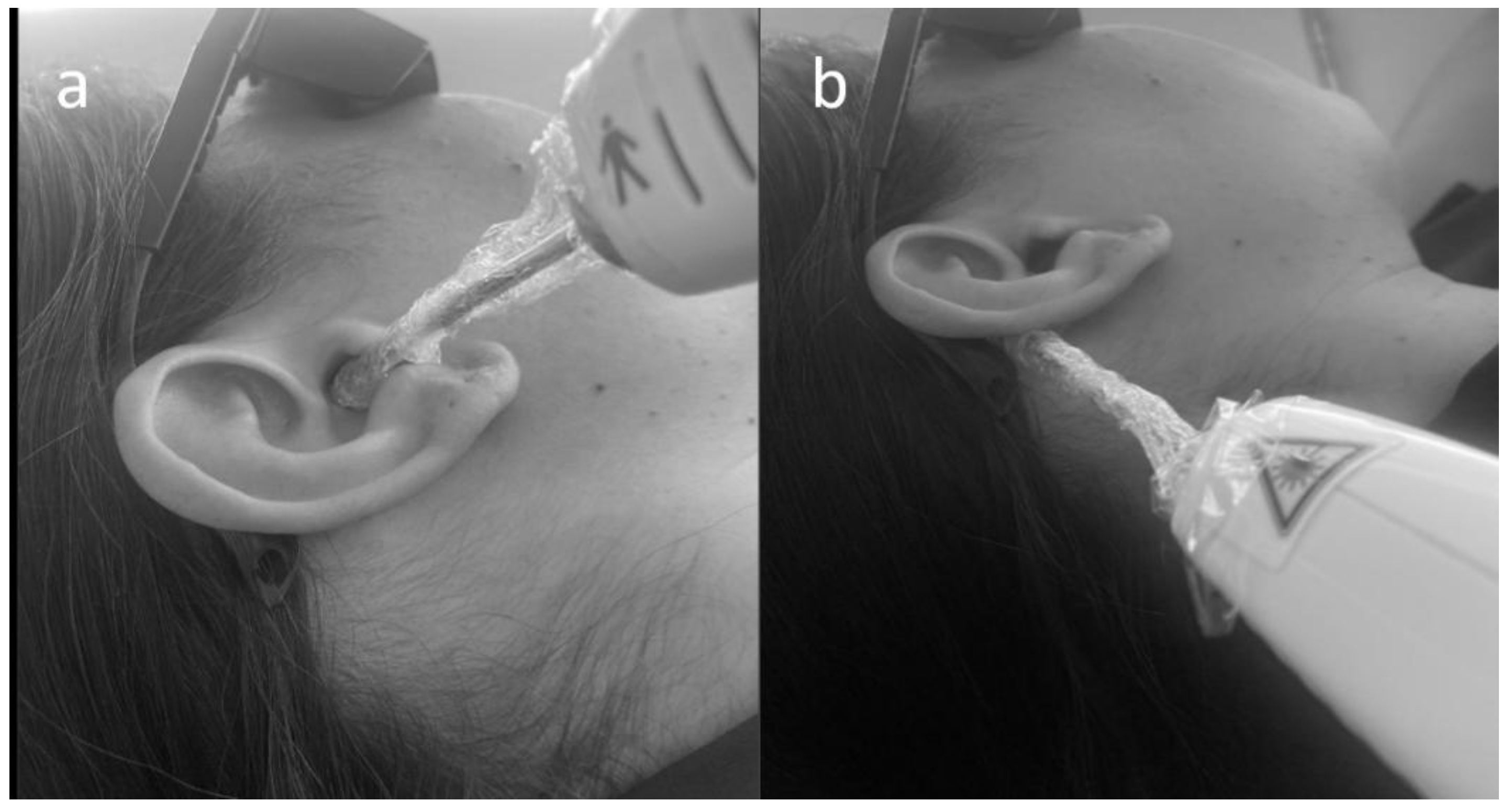

2.4. Photobiomodulation Protocol

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.; Shi, H.; Wang, M. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Patients With Acute Tinnitus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019, 98, e13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarach, C.M.; Lugo, A.; Scala, M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Odone, A.; Garavello, W.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Gallus, S. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Tinnitus. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesser, H.; Weise, C.; Westin, V.Z.; Andersson, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus Distress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbist, B.; Connor, S.; Farina, D. ESR Essentials: Diagnostic Strategies in Tinnitus—Practice Recommendations by the European Society of Head and Neck Radiology. Eur. Radiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.; Adhia, D.; Langguth, B. Tinnitus and Brain Stimulation. In Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences; 2021; Vol. 51, pp. 249–293.

- Wadhwa, S.; Jain, S.; Patil, N.; Jungade, S. Cervicogenic Somatic Tinnitus: A Narrative Review Exploring Non-Otologic Causes. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, W.S.M. da; Araújo, L.B. de; Bedaque, H. de P.; Ferreira, L.M. de B.M.; Ribeiro, K.M.O.B. de F. Impact of the Somatosensory Influence on Annoyance and Quality of Life of Individuals with Tinnitus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 91, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didier, H.A.; Cappellari, A.M.; Sessa, F.; Giannì, A.B.; Didier, A.H.; Pavesi, M.M.; Caria, M.P.; Curone, M.; Tullo, V.; Di Berardino, F.; et al. Somatosensory Tinnitus and Temporomandibular Disorders: A Common Association. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spisila, T.; Fontana, L.C.; Hamerschmidt, R.; de Cássia Cassou Guimarães, R.; Hilgenberg-Sydney, P.B. Phenotyping of Somatosensory Tinnitus and Its Associations: An Observational Cross-sectional Study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 2008–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfatti, T.; Ciralli, B.; Hilscher, M.M.; Leao, R.N.; Leao, K.E. Decreasing Dorsal Cochlear Nucleus Activity Ameliorates Noise-Induced Tinnitus Perception in Mice. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre-Demers, M.; Doyon, N.; Fecteau, S. Non-Invasive Neuromodulation for Tinnitus: A Meta-Analysis and Modeling Studies. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabau, S.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Aboseria, M.; Griepp, D.; Van Rompaey, V.; Bikson, M.; Van de Heyning, P. Comparison of the Long-Term Effect of Positioning the Cathode in TDCS in Tinnitus Patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar, B.; Atar, S.; Berkiten, G.; Üstün, O.; Kumral, T.L.; Uyar, Y. The Effect of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) on Chronic Subjective Tinnitus. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, Y.J.; Lee, J.A.; Nguyen, S.A.; Rizk, H.G.; Meyer, T.A.; Lambert, P.R. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e767–e775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegeman, I.; Velde, H.M.; Robe, P.A.J.T.; Stokroos, R.J.; Smit, A.L. Tinnitus Treatment by Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.F.; Albusoda, A.; Farmer, A.D.; Aziz, Q. The Anatomical Basis for Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation. J. Anat. 2020, 236, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Chang, Y.-C.; Zafeiropoulos, S.; Nassrallah, Z.; Miller, L.; Zanos, S. Strategies for Precision Vagus Neuromodulation. Bioelectron. Med. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, C.; Ma, Y.; Gao, S.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hong, Y.; Hou, X.; Xiao, X.; Yu, X.; et al. Immediate Modulatory Effects of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on the Resting State of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 325, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj-Koziak, D.; Gos, E.; Kutyba, J.; Ganc, M.; Jedrzejczak, W.W.; Skarzynski, P.H.; Skarzynski, H. Effectiveness of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Tinnitus: An Interventional Prospective Controlled Study. Int. J. Audiol. 2024, 63, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Hu, L. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Facilitates Cortical Arousal and Alertness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianlorenco, A.C.L.; de Melo, P.S.; Marduy, A.; Kim, A.Y.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.-J.; Fregni, F. Electroencephalographic Patterns in TaVNS: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.Y.Y.; Keatch, C.; Lambert, E.; Woods, W.; Stoddart, P.R.; Kameneva, T. Critical Review of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Challenges for Translation to Clinical Practice. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakunina, N.; Nam, E.-C. Direct and Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Tinnitus: A Scoping Review. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B. Non-Invasive Neuromodulation for Tinnitus. J. Audiol. Otol. 2020, 24, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hernando, D.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Machado-Martín, A.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; García-Esteo, F.J.; Mesa-Jiménez, J.A. Effects of Non-Invasive Neuromodulation of the Vagus Nerve for Management of Tinnitus: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, S.; Plazier, M.; Van de Heyning, P.; De Ridder, D. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) of Upper Cervical Nerve (C2) for the Treatment of Somatic Tinnitus. Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 204, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikookam, Y.; Zia, N.; Lotfallah, A.; Muzaffar, J.; Davis-Manders, J.; Kullar, P.; Smith, M.E.; Bale, G.; Boyle, P.; Irving, R.; et al. The Effect of Photobiomodulation on Tinnitus: A Systematic Review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2024, 138, 710–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, N.; Usumez, A.; Demirkol, M.; Sari, F.; Akcaboy, C. Efficacy of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Subjective Tinnitus Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.E.; Lee, M.Y.; Chung, P.-S.; Jung, J.Y. A Preliminary Study on the Efficacy and Safety of Low Level Light Therapy in the Management of Cochlear Tinnitus: A Single Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. Tinnitus J. 2019, 23, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, L.S.; Lozza, L.; Marchiori, D.M.; Almeida, D. De; Ciquinato, S.; Teixeira, D.D.C. Inflammatory Biomarkers and Tinnitus in Older Adults. 2024, 535–542. [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.W.; Jacobson, G.P.; Spitzer, J.B. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 1996, 122, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula Erika Alves, F.; Cunha, F.; Onishi, E.T.; Branco-Barreiro, F.C.A.; Ganança, F.F. Tinnitus Handicap Inventory: Cross-Cultural Adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese. Pro. Fono. 2005, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, J.S.; Yang, H.W.; Shin, J.W.; Han, J.W.; Kim, K.W. A Normative Study of the Gait Features Measured by a Wearable Inertia Sensor in a Healthy Old Population. Gait Posture 2023, 103, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-F. Efficacy of Low-Level Laser Therapy for Tinnitus: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R.K.; Durrant, F.G.; Nguyen, S.A.; Meyer, T.A.; Lambert, P.R. The Placebo Effect on Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, e263–e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.Y.; Marduy, A.; de Melo, P.S.; Gianlorenco, A.C.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.-J.J.; Fregni, F. Safety of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (TaVNS): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, J.A.; Mary, D.A.; Witte, K.K.; Greenwood, J.P.; Deuchars, S.A.; Deuchars, J. Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Healthy Humans Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, M.; Wienke, C.; Betts, M.J.; Zaehle, T.; Hämmerer, D. Current Challenges in Reliably Targeting the Noradrenergic Locus Coeruleus Using Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (TaVNS). Auton. Neurosci. 2021, 236, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keute, M.; Gharabaghi, A. Brain Plasticity and Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2021, 236, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Mrudula, K.; Sreepada, S.S.; Sathyaprabha, T.N.; Pal, P.K.; Chen, R.; Udupa, K. An Overview of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation: Basic Principles and Clinical Applications. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. / J. Can. des Sci. Neurol. 2022, 49, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.A.; Brites, R.; Fraião, G.; Pereira, G.; Fernandes, H.; de Brito, J.A.A.; Pereira Generoso, L.; Maziero Capello, M.G.; Pereira, G.S.; Scoz, R.D.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Modulates Masseter Muscle Activity, Pain Perception, and Anxiety Levels in University Students: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shan, A.; Wan, C.; Cao, X.; Yuan, Y.; Ye, S.; Gao, M.; Gao, L.; Tong, Q.; Gan, C.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Improves Anxiety Symptoms and Cortical Activity during Verbal Fluency Task in Parkinson’s Disease with Anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 361, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, A.N.H.; Graetz, L.; Hillier, S.; Uy, J.; Hamilton, T.; Opie, G.; Vallence, A.; Braithwaite, F.A.; Chamberlain, S.; Hordacre, B. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Modifies Cortical Excitability in Middle-aged and Older Adults. Psychophysiology 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.; Scheffer, A.R.; de Assunção Bastos, R.S.; Chavantes, M.C.; Mondelli, M.F.C.G. The Effects of Photobiomodulation Therapy in Individuals with Tinnitus and without Hearing Loss. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dole, M.; Auboiroux, V.; Langar, L.; Mitrofanis, J. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Transcranial Photobiomodulation on Brain Activity in Humans. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 34, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, T.; Wang, X.; Wu, A.; Kallioniemi, E.; Husain, M.M.; Liu, H. Transcranial Photobiomodulation (TPBM) With 1,064-Nm Laser to Improve Cerebral Metabolism of the Human Brain In Vivo. Lasers Surg. Med. 2020, 52, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.; Barrett, D.W.; Saucedo, C.L.; Huang, L. Da; Abraham, J.A.; Tanaka, H.; Haley, A.P.; Gonzalez-Lima, F. Beneficial Neurocognitive Effects of Transcranial Laser in Older Adults. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi, C.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation in Human Muscle Tissue: An Advantage in Sports Performance? J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1273–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolandi, M.; Javanbakht, M.; Shaabani, M.; Bakhshi, E. Effectiveness of Bimodal Stimulation of the Auditory-Somatosensory System in the Treatment of Tonal Tinnitus. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boedts, M.; Buechner, A.; Khoo, S.G.; Gjaltema, W.; Moreels, F.; Lesinski-Schiedat, A.; Becker, P.; MacMahon, H.; Vixseboxse, L.; Taghavi, R.; et al. Combining Sound with Tongue Stimulation for the Treatment of Tinnitus: A Multi-Site Single-Arm Controlled Pivotal Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadi, M.; Faraji, R.; Hamidi Nahrani, M.; Heidari, A. Effect of Simultaneous Use of Neuromodulation and Acoustic Stimulation in the Management of Tinnitus. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 76, 5495–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtarikia, S.; Tavanai, E.; Rouhbakhsh, N.; Sayadi, A.J.; Sabet, V.K. Investigating the Effectiveness of Music Therapy Combined with Binaural Beats on Chronic Tinnitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Value |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 50.51 (12.88) |

| Med (Min; Max) | 49 (26;78) |

| Gender (n) | |

| Male (%) | 66 (55%) |

| Female (%) | 54 (45%) |

| Hearing loss | |

| No loss | 58 (48.3%) |

| Mild | 42 (35%) |

| Moderate | 20 (16.7%) |

| Laterality | |

| Right | 17 (18.9%) |

| Left | 18 (20%) |

| Bilateral | 55 (61%) |

| Duration of Tinnitus (months) | |

| < 6 | 4 (3.3%) |

| 6 | 14 (11.7%) |

| 7-12 | 43 (35.8%) |

| 13-24 | 20 (16.7%) |

| > 24 | 39 (32.5%) |

| Outcome |

THI baseline |

THI post |

VASdiscomfort baseline |

VASdiscomfort post |

VASloudness baseline |

VASloudness post |

|

| Median (min;max) | 62 (36;90) | 18 (0;68) | 7 (2;10) | 1 (0;7) | 7 (3;10) | 2 (0;7) | |

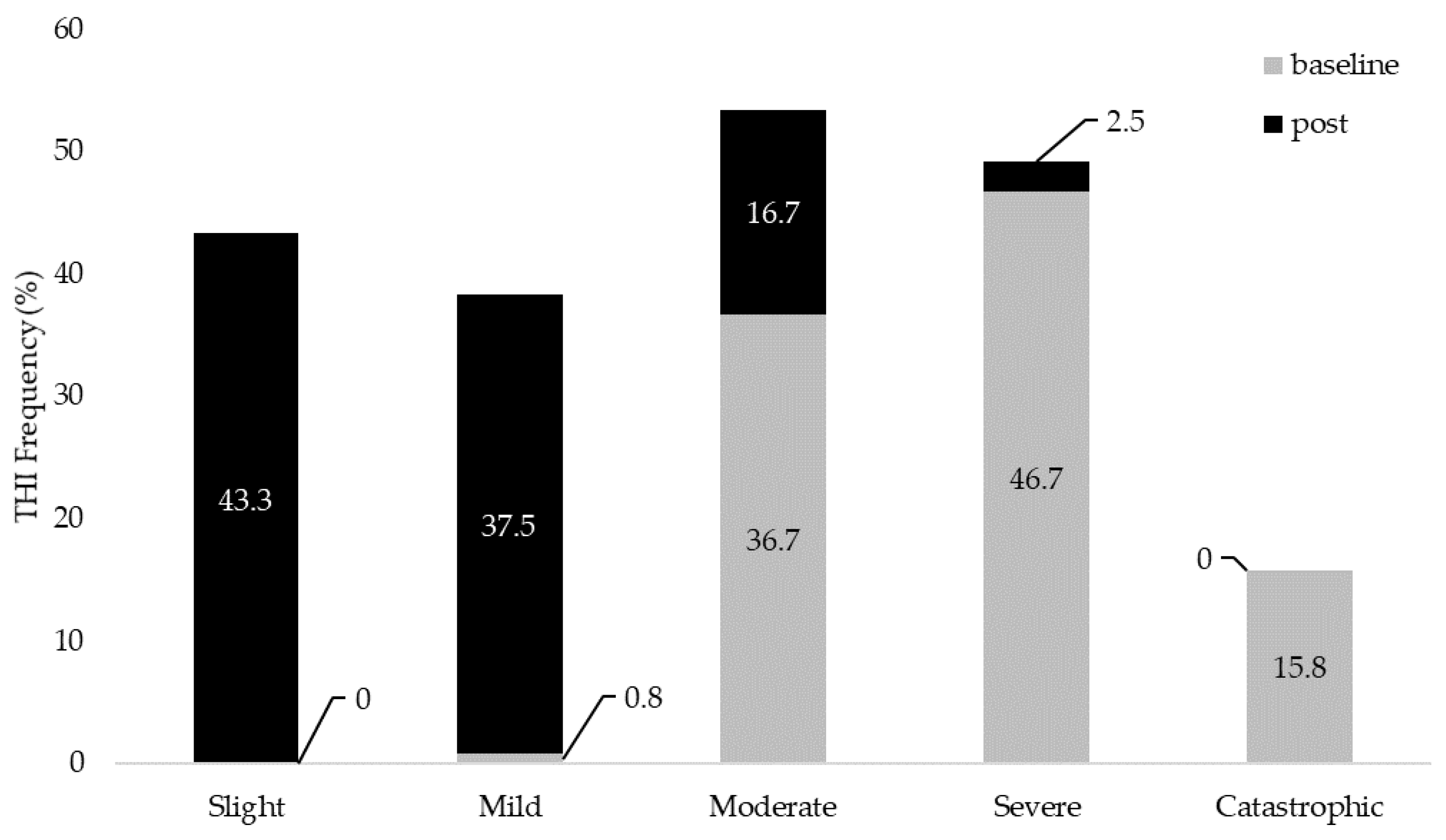

| Frequency n (%) |

Slight | 0 | 52 (43.3%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

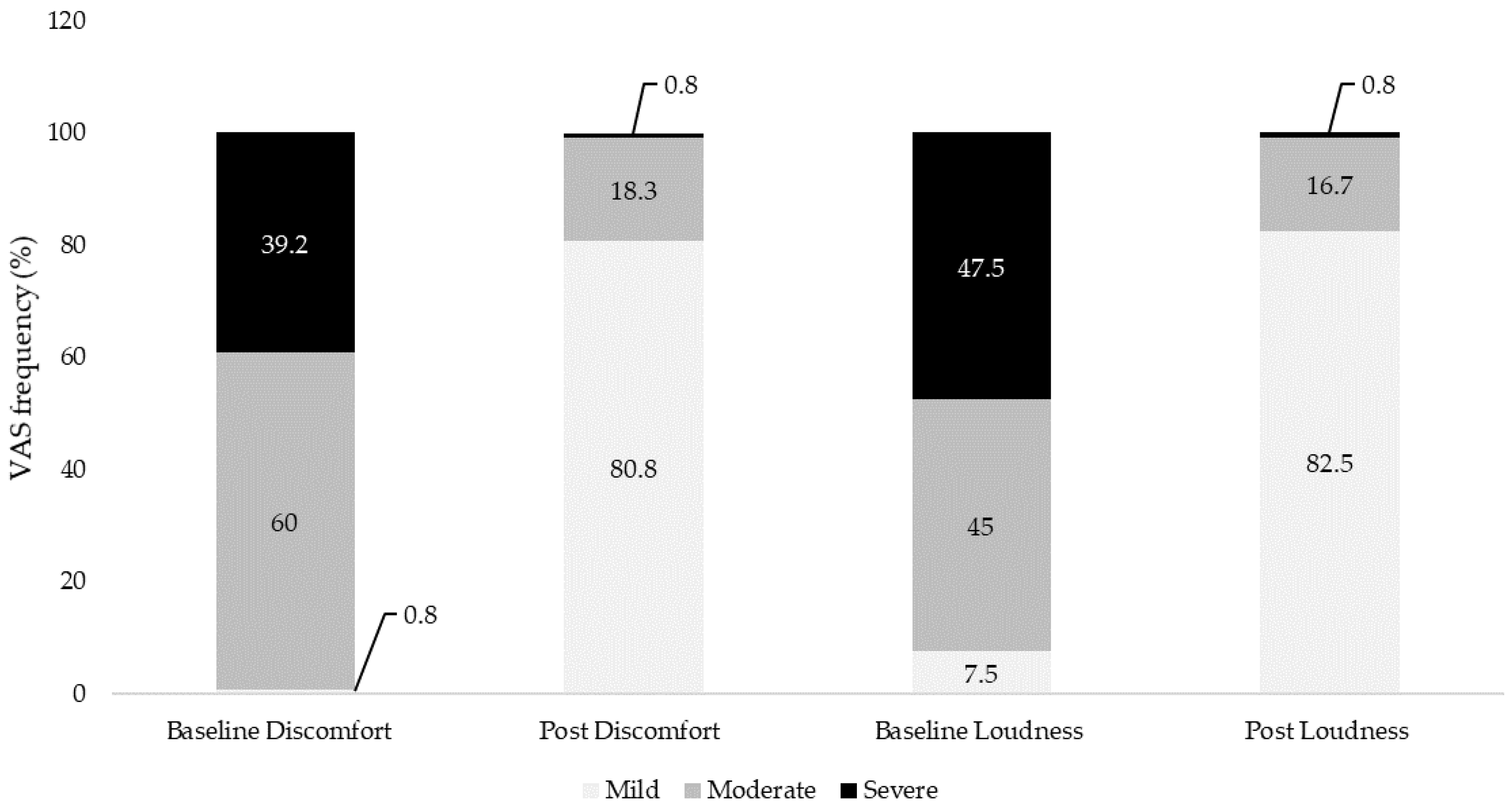

| Mild | 1 (0.8%) | 45 (37.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 97 (80.8%) | 9 (7.5%) | 99 (82.5%) | |

| Moderate | 44 (36.7%) | 20 (16.7%) | 72 (60%) | 22 (18.3%) | 54 (45%) | 20 (16.7%) | |

| Severe | 56 (46.7%) | 3 (2.5%) | 47 (39.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | 57 (47.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Catastrophic | 19 (15.8%) | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).