Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

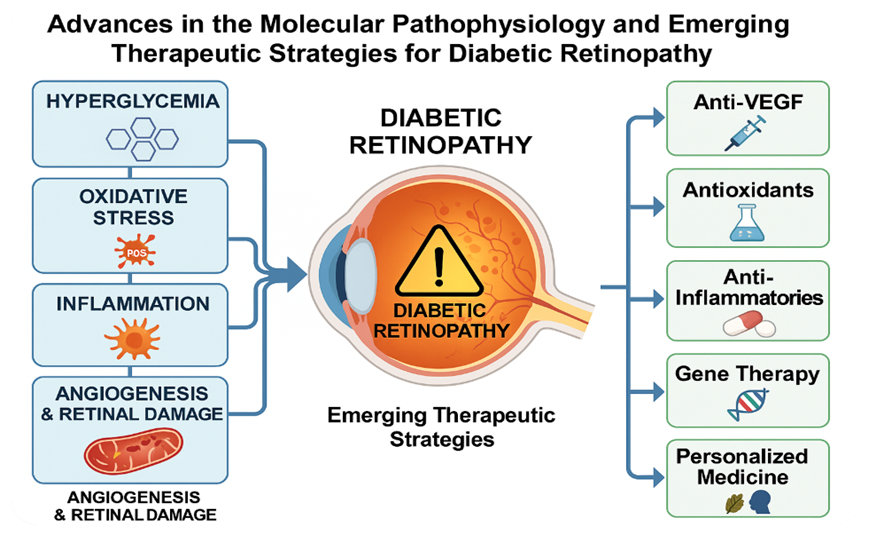

1. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

2. Diabetic Retinopathy in the Context of Other Eye Diseases

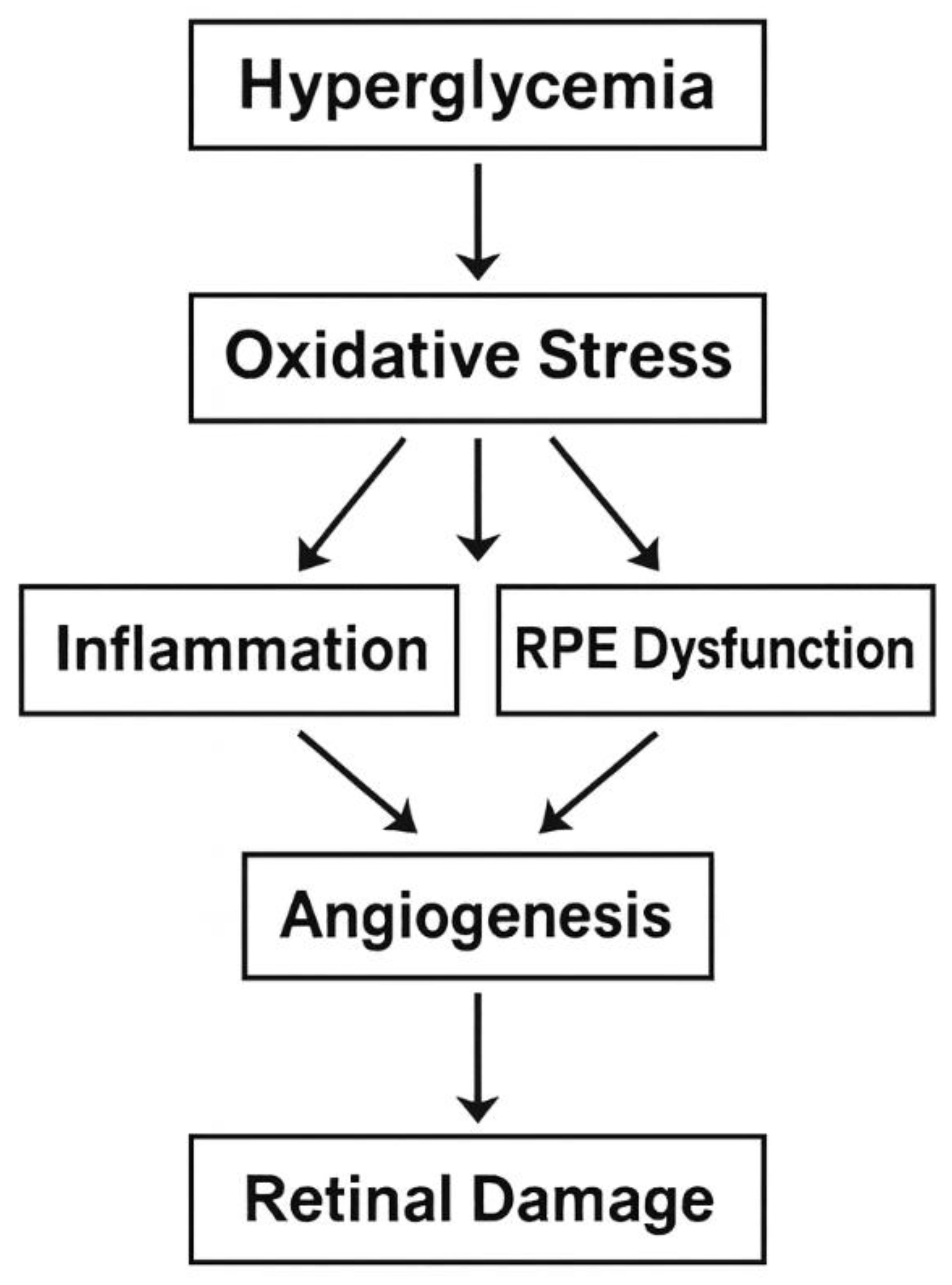

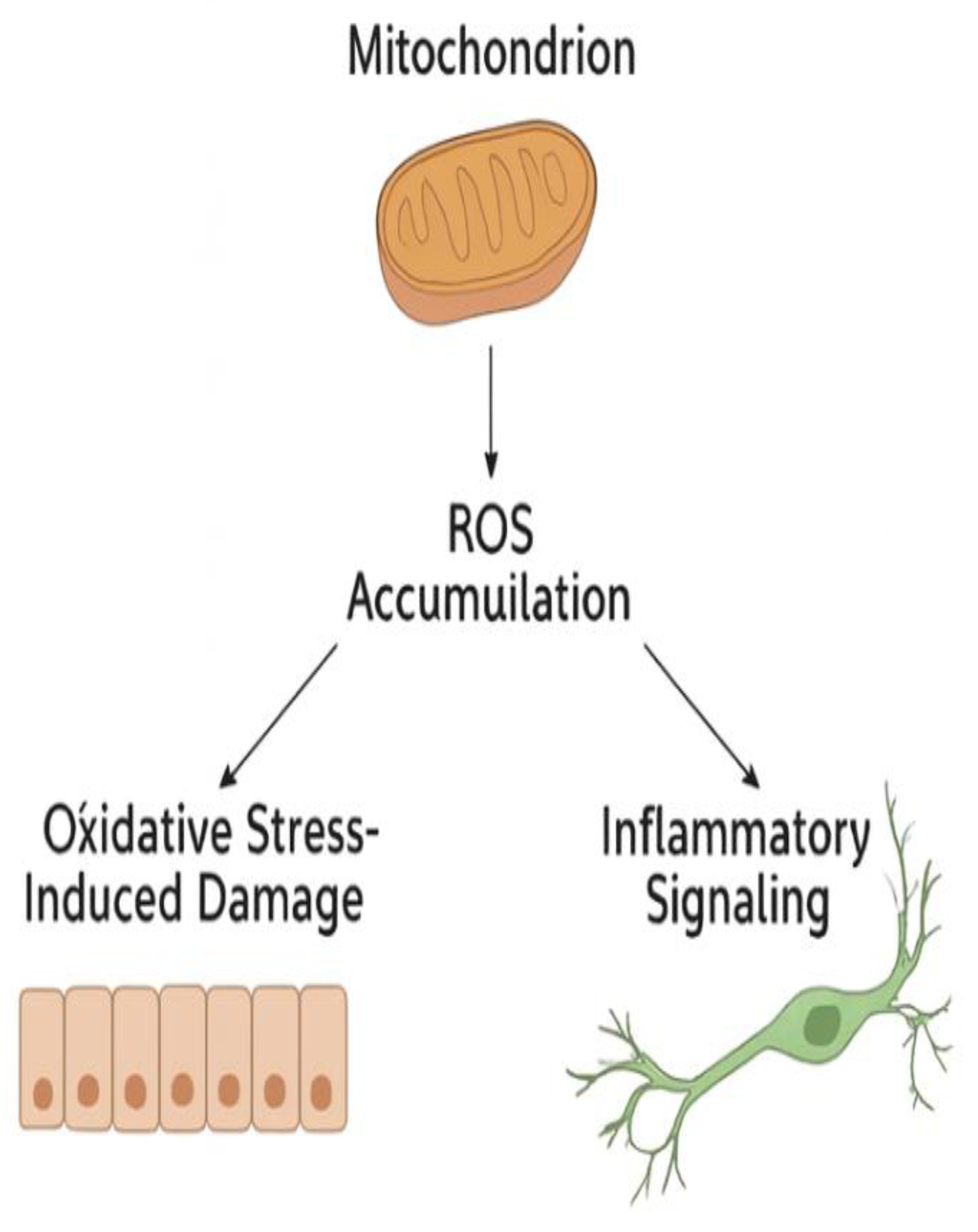

3. Oxidative Stress

4. Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE)

5. Angiogenesis

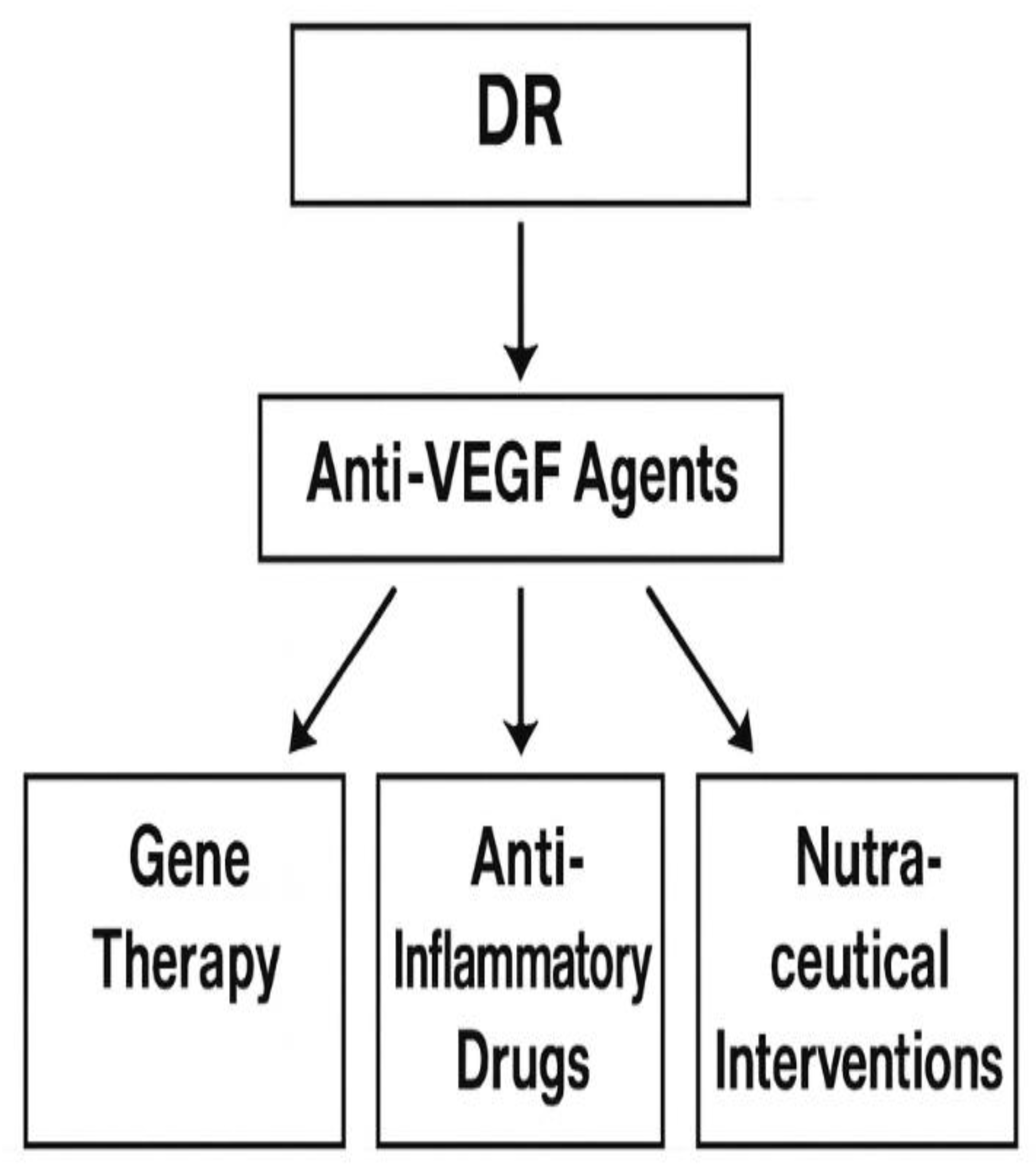

6. Current Treatment of DR

7. What Is Next for DR? Future Directions: Personalized Medicine and Targeted Therapies

8. Targeted Therapies

9. Analysis of Key Findings in DR Research

10. Conclusions

References

- Teo, Z. L.; Tham, Y.-C.; Yu, M.; Chee, M. L.; Rim, T. H.; Cheung, N.; Bikbov, M. M.; Wang, Y. X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wong, I. Y.; Ting, D. S. W.; Tan, G. S. W.; Jonas, J. B.; Sabanayagam, C.; Wong, T. Y.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, (11), 1580-1591. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P. F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, (1), 14790.

- GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, (10440), 2100-2132.

- Alegre-Díaz, J.; Herrington, W.; López-Cervantes, M.; Gnatiuc, L.; Ramirez, R.; Hill, M.; Baigent, C.; McCarthy, M. I.; Lewington, S.; Collins, R.; Whitlock, G.; Tapia-Conyer, R.; Peto, R.; Kuri-Morales, P.; Emberson, J. R. Diabetes and Cause-Specific Mortality in Mexico City. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, (20), 1961-1971. [CrossRef]

- Bragg, F.; Holmes, M. V.; Iona, A.; Guo, Y.; Du, H.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yang, L.; Herrington, W.; Bennett, D.; Turnbull, I.; Liu, Y.; Feng, S.; Chen, J.; Clarke, R.; Collins, R.; Peto, R.; Li, L.; Chen, Z. Association Between Diabetes and Cause-Specific Mortality in Rural and Urban Areas of China. JAMA 2017, 317, (3), 280-289. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. J.; Yu, D.; Wen, W.; Saito, E.; Rahman, S.; Shu, X.-O.; Chen, Y.; Gupta, P. C.; Gu, D.; Tsugane, S.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Gao, Y.-T.; Yuan, J.-M.; Tamakoshi, A.; Irie, F.; Sadakane, A.; Tomata, Y.; Kanemura, S.; Tsuji, I.; Matsuo, K.; Nagata, C.; Chen, C.-J.; Koh, W.-P.; Shin, M.-H.; Park, S. K.; Wu, P.-E.; Qiao, Y.-L.; Pednekar, M. S.; He, J.; Sawada, N.; Li, H.-L.; Gao, J.; Cai, H.; Wang, R.; Sairenchi, T.; Grant, E.; Sugawara, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ito, H.; Wada, K.; Shen, C.-Y.; Pan, W.-H.; Ahn, Y.-O.; You, S.-L.; Fan, J.-H.; Yoo, K.-Y.; Ashan, H.; Chia, K. S.; Boffetta, P.; Inoue, M.; Kang, D.; Potter, J. D.; Zheng, W. Association of Diabetes With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in Asia: A Pooled Analysis of More Than 1 Million Participants. JAMA Network Open 2019, 2, (4), e192696-e192696.

- Jenkins, A. J.; Joglekar, M. V.; Hardikar, A. A.; Keech, A. C.; O'Neal, D. N.; Januszewski, A. S. Biomarkers in Diabetic Retinopathy. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2015, 12, (1-2), 159-95.

- Wong, T. Y.; Tan, T. E. The Diabetic Retinopathy "Pandemic" and Evolving Global Strategies: The 2023 Friedenwald Lecture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, (15), 47. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Petroianu, G.; Adem, A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, (4). [CrossRef]

- Stitt, A. W. The role of advanced glycation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2003, 75, (1), 95-108. [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, D. A.; Barber, A. J.; Bronson, S. K.; Freeman, W. M.; Gardner, T. W.; Jefferson, L. S.; Kester, M.; Kimball, S. R.; Krady, J. K.; LaNoue, K. F.; Norbury, C. C.; Quinn, P. G.; Sandirasegarane, L.; Simpson, I. A. Diabetic retinopathy: seeing beyond glucose-induced microvascular disease. Diabetes 2006, 55, (9), 2401-11.

- Wiley, H. E.; Ferris, F. L., Chapter 47 - Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema. In Retina (Fifth Edition), Ryan, S. J.; Sadda, S. R.; Hinton, D. R.; Schachat, A. P.; Sadda, S. R.; Wilkinson, C. P.; Wiedemann, P.; Schachat, A. P., Eds. W.B. Saunders: London, 2013; pp 940-968.

- Wong, T. Y.; Sun, J.; Kawasaki, R.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Gupta, N.; Lansingh, V. C.; Maia, M.; Mathenge, W.; Moreker, S.; Muqit, M. M. K.; Resnikoff, S.; Verdaguer, J.; Zhao, P.; Ferris, F.; Aiello, L. P.; Taylor, H. R. Guidelines on Diabetic Eye Care: The International Council of Ophthalmology Recommendations for Screening, Follow-up, Referral, and Treatment Based on Resource Settings. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, (10), 1608-1622.

- Gupta, A.; Bansal, R.; Sharma, A.; Kapil, A., Retinal Hard Exudates. In Ophthalmic Signs in Practice of Medicine, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp 59-79.

- Campochiaro, P. A. Ocular neovascularization. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2013, 91, (3), 311-21.

- Wilkinson, C. P.; Ferris, F. L.; Klein, R. E.; Lee, P. P.; Agardh, C. D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J. T. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, (9), 1677-1682. [CrossRef]

- Flaxel, C. J.; Adelman, R. A.; Bailey, S. T.; Fawzi, A.; Lim, J. I.; Vemulakonda, G. A.; Ying, G. S. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, (1), P66-p145.

- Yang, Z.; Tan, T. E.; Shao, Y.; Wong, T. Y.; Li, X. Classification of diabetic retinopathy: Past, present and future. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1079217. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jivraj, S. Are diabetes and blood sugar control associated with the diagnosis of eye diseases? An English prospective observational study of glaucoma, diabetic eye disease, macular degeneration and cataract diagnosis trajectories in older age. BMJ Open 2025, 15, (6), e091816. [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Billard, S.; Dupas, B. Eye disorders other than diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 47, (6), 101279. [CrossRef]

- Terheyden, J. H.; Fink, D. J.; Mercieca, K.; Wintergerst, M. W. M.; Holz, F. G.; Finger, R. P. Knowledge about age-related eye diseases in the general population in Germany. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, (1), 409. [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, V. S.; Wang, J. J.; Wong, T. Y. Ocular associations of diabetes other than diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, (9), 1905-12.

- Chen, L.; Islam, R. M.; Wang, J.; Hird, T. R.; Pavkov, M. E.; Gregg, E. W.; Salim, A.; Tabesh, M.; Koye, D. N.; Harding, J. L.; Sacre, J. W.; Barr, E. L. M.; Magliano, D. J.; Shaw, J. E. A systematic review of trends in all-cause mortality among people with diabetes. Diabetologia 2020, 63, (9), 1718-1735.

- Li, Y.; Pan, A. P.; Yu, A. Y. Recent Progression of Pathogenesis and Treatment for Diabetic Cataracts. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 40, (4), 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; He, D.; Shen, M.; Chen, R.; Shen, X. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and neovascular glaucoma in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, (1), 163. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Yuan, J.; Chen, F.; Yao, Y.; Xing, S.; Yu, X.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Bao, J.; Qu, J.; Su, J.; Chen, H. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of 88,250 individuals highlights pleiotropic mechanisms of five ocular diseases in UK Biobank. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104161. [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, L. I. M.; Varesi, A.; Barbieri, A.; Marchesi, N.; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut-Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, (17). [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lin, M.; Hong, Y. The causal effect of glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy: a Mendelian randomization study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, (1), 80. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Yang, C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101799. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R. A.; Chan, P. S. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2007, 2007, 43603.

- Tang, J.; Kern, T. S. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, (5), 343-58.

- Forbes, J. M.; Cooper, M. E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, (1), 137-88.

- Madsen-Bouterse, S. A.; Kowluru, R. A. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2008, 9, (4), 315-27. [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kotwani, A. Exploring the various aspects of the pathological role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 99, 137-48. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Bandello, F.; Berg, K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Gerendas, B. S.; Jonas, J.; Larsen, M.; Tadayoni, R.; Loewenstein, A. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica 2017, 237, (4), 185-222.

- Simó, R.; Sundstrom, J. M.; Antonetti, D. A. Ocular Anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic retinopathy: the role of VEGF in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, (4), 893-9. [CrossRef]

- Sajovic, J.; Cilenšek, I.; Mankoč, S.; Tajnšek, Š.; Kunej, T.; Petrovič, D.; Globočnik Petrovič, M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-related polymorphisms rs10738760 and rs6921438 are not risk factors for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 19, (1), 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Huang, D.; Li, Z. Genetic insights and emerging therapeutics in diabetic retinopathy: from molecular pathways to personalized medicine. Frontiers in Genetics 2024, Volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gong, C. Y.; Lu, B.; Sheng, Y. C.; Yu, Z. Y.; Zhou, J. Y.; Ji, L. L. The Development of Diabetic Retinopathy in Goto-Kakizaki Rat and the Expression of Angiogenesis-Related Signals. Chin. J. Physiol. 2016, 59, (2), 100-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Y.; Yang, M. Roles of fibroblast growth factors in the treatment of diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2024, 15, (3), 392-402. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, B. miR-372-3p is a potential diagnostic factor for diabetic nephropathy and modulates high glucose-induced glomerular endothelial cell dysfunction via targeting fibroblast growth factor-16. Arch. Med. Sci. 2023, 19, (3), 703-716. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, C.; Gu, C.; Cui, X.; Wu, J. MiRNA-144-3p inhibits high glucose induced cell proliferation through suppressing FGF16. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, (7). [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, A.; Chen, X.; Cui, Y.; Meng, Q. Long-Term Retinal Neurovascular and Choroidal Changes After Panretinal Photocoagulation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Med. 2021, Volume 8 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Stefánsson, E. The therapeutic effects of retinal laser treatment and vitrectomy. A theory based on oxygen and vascular physiology. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2001, 79, (5), 435-440. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jaganathan, R.; Hao, Y. Current Advances in Pharmacotherapy and Technology for Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, (1), 1694187.

- Ogata, N.; Tombran-Tink, J.; Jo, N.; Mrazek, D.; Matsumura, M. Upregulation of pigment epithelium-derived factor after laser photocoagulation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 132, (3), 427-429. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lo, A. C. Y. Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiology and Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, (6), 1816. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hua, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L. Laser Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy: History, Mechanism, and Novel Technologies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, (18), 5439. [CrossRef]

- Tsilimbaris, M. K.; Kontadakis, G. A.; Tsika, C.; Papageorgiou, D.; Charoniti, M. Effect of panretinal photocoagulation treatment on vision-related quality of life of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina 2013, 33, (4), 756-61. [CrossRef]

- Blumenkranz, M. S.; Yellachich, D.; Andersen, D. E.; Wiltberger, M. W.; Mordaunt, D.; Marcellino, G. R.; Palanker, D. Semiautomated patterned scanning laser for retinal photocoagulation. Retina 2006, 26, (3), 370-6. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, Y. M.; Kaur, K.; Egbert, P. R.; Blumenkranz, M. S.; Moshfeghi, D. M. Human histopathology of PASCAL laser burns. Eye (Lond.) 2013, 27, (8), 995-6. [CrossRef]

- Inan, S.; Polat, O.; Yıgıt, S.; Inan, U. U. PASCAL laser platform produces less pain responses compared to conventional laser system during the panretinal photocoagulation: a randomized clinical trial. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, (4), 1010-1017. [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, L.; Huang, C.; Zhong, X.; Gong, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, F.; Li, C.; Lu, L.; Jin, C. Subthreshold Pan-Retinal Photocoagulation Using Endpoint Management Algorithm for Severe Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Paired Controlled Pilot Prospective Study. Ophthalmic Res. 2020, 64, (4), 648-655. [CrossRef]

- Kozak, I.; Oster, S. F.; Cortes, M. A.; Dowell, D.; Hartmann, K.; Kim, J. S.; Freeman, W. R. Clinical evaluation and treatment accuracy in diabetic macular edema using navigated laser photocoagulator NAVILAS. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, (6), 1119-24. [CrossRef]

- Deschler, E. K.; Sun, J. K.; Silva, P. S. Side-Effects and Complications of Laser Treatment in Diabetic Retinal Disease. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 29, (5-6), 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N. C.; Hsieh, Y. T.; Yang, C. M.; Berrocal, M. H.; Dhawahir-Scala, F.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Pappuru, R. R.; Dave, V. P. Vitrectomy for diabetic retinopathy: A review of indications, techniques, outcomes, and complications. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 14, (4), 519-530. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, G. Y.; De Juan, E., Jr.; Humayun, M. S.; Pieramici, D. J.; Chang, T. S.; Awh, C.; Ng, E.; Barnes, A.; Wu, S. L.; Sommerville, D. N. A new 25-gauge instrument system for transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy surgery. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, (10), 1807-12; discussion 1813. [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, C. Transconjunctival sutureless 23-gauge vitrectomy. Retina 2005, 25, (2), 208-11. [CrossRef]

- Oshima, Y.; Wakabayashi, T.; Sato, T.; Ohji, M.; Tano, Y. A 27-gauge instrument system for transconjunctival sutureless microincision vitrectomy surgery. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, (1), 93-102.e2. [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Kurihara, T.; Uchida, A.; Nagai, N.; Shinoda, H.; Tsubota, K.; Ozawa, Y. Wide-Angle Viewing System versus Conventional Indirect Ophthalmoscopy for Scleral Buckling. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13256. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Lin, P.; Xing, Y.; Yang, N. Recent advances in the treatment and delivery system of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, Volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H.; Iwama, Y.; Tanioka, K.; Emi, K. Paracentral Acute Middle Maculopathy following Vitrectomy for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Characteristics. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, (12), 1929-1936. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lin, Y.; Zeng, R.; Yang, Z.; Deng, X.; Lan, Y. The incidence and risk factors of neovascular glaucoma secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy after vitrectomy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, (6), 3057-3067. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.; Piggott, K.; Bao, Y. K.; Pham, H.; Kavali, S.; Rajagopal, R. Complete Posterior Vitreous Detachment Reduces the Need for Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 2019, 50, (11), e266-e273. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, N.; Kumar, V.; Ramachandran, A.; Venkatesh, R.; Tekchandani, U.; Tyagi, M.; Jayadev, C.; Dogra, M.; Chawla, R. Vitrectomy for cases of diabetic retinopathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, (12). [CrossRef]

- Sobrin, L.; D'Amico, D. J. Controversies in Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide Use. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2005, 45, (4), 133-141. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J. B.; Kreissig, I.; Söfker, A.; Degenring, R. F. Intravitreal Injection of Triamcinolone for Diffuse Diabetic Macular Edema. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, (1), 57-61. [CrossRef]

- Martidis, A.; Duker, J. S.; Greenberg, P. B.; Rogers, A. H.; Puliafito, C. A.; Reichel, E.; Baumal, C. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, (5), 920-927. [CrossRef]

- Avitabile, T.; Longo, A.; Reibaldi, A. Intravitreal Triamcinolone Compared With Macular Laser Grid Photocoagulation for the Treatment of Cystoid Macular Edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 140, (4), 695.e1-695.e10. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Q.; Gillies, M. C.; Wong, T. Y. Management of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. JAMA 2007, 298, (8), 902-16.

- Pearson, P.; Levy, B.; Comstock, T.; Group, F. A. I. S. Fluocinolone Acetonide Intravitreal Implant to Treat Diabetic Macular Edema: 3–Year Results of a Multi–Center Clinical Trial. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, (13), 5442-5442.

- Gupta, N.; Mansoor, S.; Sharma, A.; Sapkal, A.; Sheth, J.; Falatoonzadeh, P.; Kuppermann, B.; Kenney, M. Diabetic retinopathy and VEGF. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2013, 7, 4-10. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E. B.; Farah, M. E.; Maia, M.; Penha, F. M.; Regatieri, C.; Melo, G. B.; Pinheiro, M. M.; Zanetti, C. R. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in ophthalmology. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, (2), 117-44. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, B.; Hong, T.; Gilles, M. C.; Chang, A. Anti-VEGF Therapy for Diabetic Eye Diseases. Asia. Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Phila). 2017, 6, (6), 535-545. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Radke, N. V.; Amarasekera, S.; Park, D. H.; Chen, N.; Chhablani, J.; Wang, N.-K.; Wu, W.-C.; Ng, D. S. C.; Bhende, P.; Varma, S.; Leung, E.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Fang, D.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhao, P.; Sharma, T.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Lai, C.-C.; Lam, D. S. C. Updates on medical and surgical managements of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy. Asia. Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Phila). 2025, 14, (2), 100180. [CrossRef]

- Macugen Diabetic Retinopathy Study Group. Changes in Retinal Neovascularization after Pegaptanib (Macugen) Therapy in Diabetic Individuals. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, (1), 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Macugen Diabetic Retinopathy Study Group. A Phase II Randomized Double-Masked Trial of Pegaptanib, an Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Aptamer, for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, (10), 1747-1757. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M. B.; Zhou, D.; Loftus, J.; Dombi, T.; Ice, K. S. A Phase 2/3, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Masked, 2-Year Trial of Pegaptanib Sodium for the Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, (6), 1107-1118. [CrossRef]

- Fortin, P.; Mintzes, B.; Innes, M. A Systematic Review of Intravitreal Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. CADTH Technol. Overv. 2013, 3, (1).

- Li, J. Q.; Welchowski, T.; Schmid, M.; Letow, J.; Wolpers, C.; Pascual-Camps, I.; Holz, F. G.; Finger, R. P. Prevalence, incidence and future projection of diabetic eye disease in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, (1), 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, (1), 352. [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, L.; Banihashemi, S.; Malekzadegan, Y.; Catanzaro, R.; Moghadam Ahmadi, A.; Marotta, F. Microbiome as an endocrine organ and its relationship with eye diseases: Effective factors and new targeted approaches. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2024, 15, (5), 96446. [CrossRef]

- Gwon, H.-N.; Son, H.-J.; Shin, Y.-J. Association of Body Metrics and Ocular Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, (16). [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Koka, S.; Boini, K. M. Understanding the Role of Adipokines in Cardiometabolic Dysfunction: A Review of Current Knowledge. Biomolecules 2025, 15, (5). [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M. J.; Bamba, S. Diabetic cataracts. Dis. Mon. 2021, 67, (5), 101134.

- Tian, C.; Chen, Y.; Xu, B.; Tan, X.; Zhu, Z. Association of triglyceride-glucose index with the risk of incident aortic dissection and aneurysm: a large-scale prospective cohort study in UK Biobank. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, (1), 282. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fan, Z. The mechanism and therapeutic strategies for neovascular glaucoma secondary to diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1102361. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. C.; Wilkins, M.; Kim, T.; Malyugin, B.; Mehta, J. S. Cataracts. Lancet 2017, 390, (10094), 600-612.

- Wei, B.; Hu, X.; Shu, B. L.; Huang, Q. Y.; Chai, H.; Yuan, H. Y.; Zhou, L.; Duan, Y. C.; Yao, L. L.; Dong, Z. E.; Wu, X. R. Association of triglyceride-glucose index and derived indices with cataract in middle-aged and elderly Americans: NHANES 2005-2008. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, (1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Kashyap, A.; Srivastav, T.; Yadav, A.; Pandey, S.; Majhi, M. M.; Verma, K.; Prabu, A.; Singh, V. Enzymatic and biochemical properties of lens in age-related cataract versus diabetic cataract: A narrative review. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, (6), 2379-2384. [CrossRef]

- Hom, M.; De Land, P. Self-reported dry eyes and diabetic history. Optometry (St. Louis, Mo.) 2006, 77, (11), 554-8.

- Brar, G. K.; Bawa, M.; Chadha, C.; Gupta, T.; Kaur, H. Proportion of dry eye in type II diabetics. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, (4), 1311-1315. [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti, V.; Kasturi, N.; Rajappa, M.; Gochhait, D. Ocular surface disorder among adult patients with type II diabetes mellitus and its correlation with tear film markers: A pilot study. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 11, (2), 156-160. [CrossRef]

- Mangoli, M. V.; Bubanale, S. C.; Bhagyajyothi, B. K.; Goyal, D. Dry eye disease in diabetics versus non-diabetics: Associating dry eye severity with diabetic retinopathy and corneal nerve sensitivity. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, (4), 1533-1537. [CrossRef]

- Lima-Fontes, M.; Barata, P.; Falcão, M.; Carneiro, Â. Ocular findings in metabolic syndrome: a review. Porto Biomed. J. 2020, 5, (6), e104. [CrossRef]

| Stage | Key Features | Fundus Findings | Visual Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Proliferative (NPDR) | Microaneurysms, dot hemorrhages | Cotton wool spots, hard exudates | Mild to moderate |

| Proliferative (PDR) | Neovascularization | Vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment | Severe vision loss |

| Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) | Retinal thickening in macula | Cystoid spaces in OCT | Blurred central vision |

| Diagnosis | Frequency of occurrence in patients with diabetes | Association with chronic hyperglycemia | The main pathogenetic mechanisms Associated diseases and conditions | Associated diseases and conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic retinopathy (DR) | The total frequency of occurrence is 20-25.7%. In patients with type 1 diabetes, 54.4%, in patients with type 2 diabetes [1,80]. | A decrease in blood glucose by 10 mg/dl is directly related to a decrease in intraocular pressure by 0.09 mmHg [20]. |

Oxidative stress. Dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium. Abnormal angiogenesis. Inflammation of the retina. Disruption of neurotransmitter production. Violation of the production of trophic factors in the retina. Similar genetic correlations with OTHER dysbiosis of the ocular and intestinal microbiota [26,80,81,82]. | Fatness. Cardiovascular diseases. Dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Chronic kidney disease. Old age Intestinal diseases [27,83,84]. |

| Cataract | Prevalence: 3.3% vs. 1.9% in patients with diabetes compared to the control group. The incidence of cataracts in people with diabetes is 3-5 times higher than in healthy people. Up to 20% of all cataract surgeries are performed in patients with diabetes mellitus [85]. |

The risk of developing cataracts depends on the duration of diabetes and the severity of hyperglycemia [85]. | Metabolic disorders Oxidative stress Old age Denaturation of lens proteins Dyslipidemia Smoking Similar genetic correlations with others) [26,81,86,87]. |

Obesity and metabolic syndrome. Old age. Cardiovascular diseases. High degree of myopia. Smoking. Exposure to sunlight. Therapy with steroids. Local injuries) Intestinal diseases [26,86,88,89,90] |

| Glaucoma | DR is the main cause of glaucoma, accounting for 30% to 52.38% of cases. glaucoma [22,87]. |

The probable risk of glaucoma in patients with chronic hyperglycemia is high [22,87]. |

Similar genetic correlations with others. Degeneration of axons. Neuroinflammation. Transynaptic degeneration of retinal ganglion cells. Dysbiosis of ocular and intestinal microbiota [22,82]. |

Old age. Systemic diseases Cardiovascular diseases [87]. |

| Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) | Ambiguous results: The same prevalence or risk of developing DR or its progression. The number of people living with diabetes and AMD, DR is expected to grow rapidly due to the aging population and the additional risk of visual impairment outside of DR [20,26]. |

High risk of developing DR with chronic hyperglycemia for more than 5 years [26]. | Abnormal angiogenesis Inflammation Dyslipidemia Similar genetic correlations with others. Dysbiosis of the ocular and intestinal microbiota. [26,81,82]. |

Old age Cardiovascular diseases Fatness Intestinal diseases [26,82]. |

| Dry eye syndrome |

Higher prevalence from 20% to 53% in patients with diabetes and others compared to the general population [91,92]. |

High risk in uncontrolled diabetes [92]. | Similar genetic correlations with others. Instability of the tear film. Hyperosmolarity. Chronic inflammation. Violation of the production of tear proteins. Structural abnormality in the corneal nerve fibers. Autonomic neuropathy [93,94]. |

Old age Fatness Encephalopathy Cardiovascular diseases [92,95]. |

| Therapy | Target | Mechanism | Clinical Stage |

| Anti-VEGF (e.g., ranibizumab) | VEGF-A | Inhibits angiogenesis | Approved |

| Corticosteroids | Inflammation | Suppress cytokine release | Approved |

| Antioxidants (e.g., lutein) | ROS | Reduces oxidative stress | Preclinical/Clinical |

| Gene therapy | VEGF, PEDF | Long-term suppression or overexpression | Experimental |

| Stem cell therapy | Retinal regeneration | Replaces damaged cells | Experimental |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).