1. Introduction

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus and a major pathogen responsible for acute viral hepatitis [

1,

2]. HEV infection has emerged as a significant global public health challenge. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis estimated that approximately 12.47% of the global population (around 939 million) have experienced a past HEV infection, while 15 to 110 million individuals are either currently or recently infected [

3]. HEV can cause both outbreaks and sporadic cases of hepatitis, typically manifesting as a self-limiting illness [

4]. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, HEV infection may progress rapidly to liver cirrhosis [

5]. In the general population, the mortality ranges from 0.2% to 1.0%, but it is significantly higher during pregnancy, especially in developing countries [

6,

7]. Moreover, HEV-associated central nervous system disorders have also been reported in infected patients [

8].

HEV belongs to the family

Hepeviridae, which the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) divided into two subfamilies:

Orthohepevirinae and

Pisci-hepevirus. The subfamily

Orthohepevirinae includes four genera and nine species [

9]: (1)

Paslahepevirus (PASLHEV), two species (

Paslahepevirus alci and

P. balayani); (2)

Rocahepevirus (RCHEV), two species (

Rocahepevirus eothenomi and

R. ratti); (3)

Chirohepevirus (CHHEV), three species (

Chirohepevirus desmodi,

C. eptesici,

C. rhinolophi) [

10,

11]; and (4)

Avihepevirus (AVHEV), two species (

Avihepevirus egretti and

A. magniiecur). Human-pathogenic HEV strains are generally classified as

P. balayani and subdivided into eight genotypes (HEV-1 to HEV-8). HEV-1 and HEV-2 circulate mainly in developing countries via fecal-oral transmission [

12,

13], whereas HEV-3 and HEV-4 are zoonotic, infecting domestic pigs, wild boars, deer, rabbits, and humans [

14]. Human infections typically occur through the consumption of undercooked meat or blood transfusion, making these genotypes predominant strains in developed countries [

15].

Rat hepatitis E virus (rat HEV), a member of the genus

Rocahepevirus, was long believed to infect only rodents [

16,

17]. This view changed in 2018 when the first human case of rat HEV infection was reported in Hong Kong, China [

18]. The strain isolated from a liver transplant recipient shared 99.2% genomic identity with local rat HEV strains from Norway rats (

Rattus norvegicus). The patient's serum reacted strongly to the rat HEV-specific capsid protein p241 but not to the human HEV antigen p239, confirming that rat HEV represent a distinct lineage [

19]. This discovery overturned the assumption of species-restricted tropism of rat HEV and highlighted its potential for interspecies transmission. Since then, chronic rat HEV infections have been reported in immunocompromised patients, pediatric cases, and HIV-positive individuals in Spain, France, and other regions [

20,

21]. Despite its growing recognition, rat HEV remains underdiagnosed due to limitations in diagnostic assays and screening protocols, which likely contribute to the underestimation of acute hepatitis cases of unknown origin [

22].

Yunnan Province, located in China's southwestern border region adjoining Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, is a global biodiversity hotspot and a critical hub for the cross-border spread of zoonotic viruses [

23]. Its unique tropical-subtropical climate gradient and complex topography sustain high small mammal diversity (e.g., rodents and shrews). Frequent human-animal interactions (such as mixed farming practices), active livestock trade, and transboundary wildlife movement elevate HEV transmission risks for both humans and domestic animals (cattle, goats) [

24]. HEV prevalence rates of 7.79%–22.70% have been reported in Yunnan's small mammals [

25]. Infections are not limited to domestic rats (

Rattus tanezumi,

R. norvegicus) but extend to tree shrews (

Tupaia belangeri) and shrews (

Soricidae) [

26], demonstrating broad viral adaptability across

Rodentia,

Scandentia, and

Eulipotyphla. Considerable genotypic diversity has also been observed, including emerging genotypes such HEV-C3 [

27]. These ecological and virological features establish Yunnan as an important reservoir for HEV: high densities sustain viral circulation, multiple host species facilitate cross-species transmission, and genetic diversity enables continuous viral adaptation, creating hotspots for emerging infectious disease [

23].

To better understand the infection and evolution of rat HEV, we collected small mammals from seven counties and cities in Southwestern Yunnan Province, China. Through molecular epidemiology, phylogenetic reconstruction, and evolutionary dating, this study aimed to (i) characterize prevalence patterns, (ii) assess host adaptability and cross-species potential, and (iii) elucidate genomic features and evolutionary history of rodent-derived HEV strains, thereby providing scientific evidence to guide the prevention and control of small mammal-borne HEV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Viral RNA Extraction

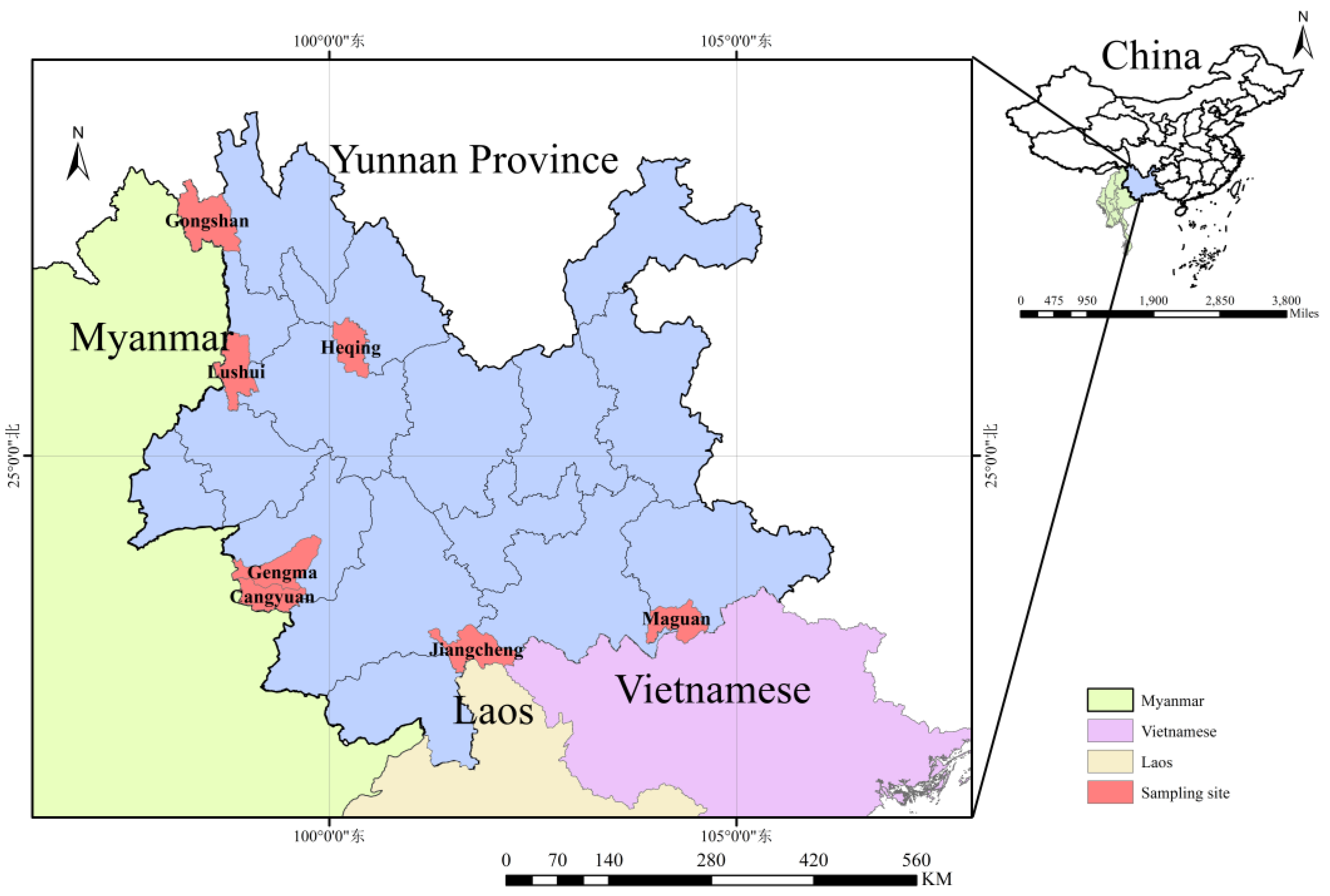

From July 2022 to October 2024, small mammals were collected from residential areas, farms, shrublands, and forests across seven counties and cities in Yunnan Province, including Gongshan, Lushui, Heqing, Cangyuan, Gengma, Jiangcheng, and Maguan, spanning the province from west to south (

Figure 1). Animals were trapped using baited mouse cages (20 × 12 × 10.5 cm; Xiangyun Hong Jin Mouse Cage Factory, Dali, Yunnan, China) with fresh fried dough as bait. Tissue samples (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and rectum) were collected from all animals, aliquoted into pre-cooled 2 mL cryotubes (CORNING, Shanghai, China), stored in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently transferred to a –80°C ultra-low temperature freezer until testing.

Species identification was performed using a morphology-molecular dual verification system. First, taxonomic experts conducted morphological classification based on external characteristics. This was followed by molecular identification through amplification and Sanger sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (

mt-Cytb) [

28,

29,

30].

Under sterile conditions, approximately 1 gram of liver tissue was placed into a GeneReady Animal PIII grinding tube (Life Real, Hangzhou, China) containing 600 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were homogenized using a GeneReady Ultimate homogenizer (Life Real, Guangzhou, China). A total of 300 μL of the resulting supernatant was used for RNA extraction with a commercial kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) on a fully automated nucleic acid extraction and purification system (BIOER, Hangzhou, China). Extracted RNA was stored at –80°C for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Detection of HEV RNA

Based on previous studies and high-throughput sequencing results, universal primers targeting the conserved RdRp region of HEV were designed for viral detection. A semi-nested PCR was used to screen liver tissue samples from small mammals for rat HEV [

28,

31]. Each PCR round was performed in a 25 μL reaction mixture. In the first round, a one-step RT-PCR kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) was used with 3 μL of RNA template. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: reverse transcription at 42.0°C for 30 min; initial denaturation at 94.0°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94.0°C for 30 s, 52.8°C for 30 s, and 72.0°C for 30 s; followed by a final extension at 72.0°C for 5 min and hold at 4.0°C. The second round was performed with Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) using 1 μL of the first-round product as template. Cycling conditions were: 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min [

32].

Amplification products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis. Bands of the expected size were excised and purified using a gel extraction kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA), and bidirectional Sanger sequencing was conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Samples yielding overlapping peaks or sequencing failures were re-purified (OMEGA Bio-Tek, Norcross, USA), cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), and sequenced from positive clones.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of rat HEV in small mammals was calculated as the number of positive samples divided by the total number of animals tested. Associations between HEV infection status and explanatory variables were initially assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Variables with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were subsequently included in a binary multivariate logistic regression model to evaluate their independent effects while controlling for potential confounders. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with cooresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

2.4. High-throughput Sequencing and Whole Genome Acquisition

Viral RNA from positive samples was used to construct sequencing libraries, and paired-end sequencing was performed on the MGISEQ-2000 platform. Raw data were processed through joint quality control using Trimmomatic v0.39 and FastQC v0.11.9 to remove low-quality sequences. Adapter contamination was eliminated using Cutadapt v3.4, yielding high-quality clean reads.

The processed data were aligned against a custom HEV reference database using the DIAMOND v2.0.13 algorithm, and candidate sequences with ≥95% confidence were retained. De novo assembly was performed in parallel with SOAPdenovo2 (r240) and MEGAHIT v1.2.9, and resulting contigs were validated through BLASTn homology searches. Final sequence correction and open reading frame (ORF) annotation were conducted in Geneious Prime, using the reference genome as a guide.

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

Representative HEV gene sequences were retrieved from NCBI GenBank database for phylogenetic analysis. Multiple sequences alignment was performed using the MAFFT algorithm in Geneious Prime, with manual correction for reading frame shifts. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed under the GTR+I nucleotide substitution model with 1,000 bootstrap replicates to assess the robustness of tree topology. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities were calculated in Geneious Prime.

Recombination analysis was conducted using RDP4. Six algorithms, including RDP, Chimaera, BootScan, GENECONV, MaxChi, and SiScan, were applied to detect potential recombination events, and only events supported by at least four methods were retained. For each candidate event, corresponding sequences were extracted, realigned with MAFFT, and further validated in SimPlot (window size: 200 bp; step size: 20 bp).

The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was identified using IQ-Tree. Bayesian evolutionary inference was performed with BEASTv1.10.4. Parameters, including sampling times, substitution models, molecular clock models, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chain lengths, and priors were configured using the BEAUti interface. MCMC runs were executed in BEAST to generate posterior distributions of trees. TreeAnnotator was applied to discard burn-in and summarize tree statistics, while FigTree v1.4.4 was used for visualization, annotation, and calibration of divergence times.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and HEV Detection

A total of 818 small mammals were collected, representing 17 species, 7 families, and 4 orders. Among these, oriental house rat (

Rattus tanezumi) comprised 35.45% (290/818), Chevrieri's field mouse (

Apodemus chevrieri) 24.69% (202/818), and other species collectively 39.86% (326/818). The samples included 399 females (48.78%) and 419 males (51.22%) (419/818). Age composition consisted of 14 juveniles (1.71%), 87 sub-adults (10.64%), and 717 adults (87.65%). Samples were obtained from four habitat types: residential areas (9.90%, 81/818), farming areas (31.42%, 257/818), shrublands (26.04%, 267/818), and forest areas (26.04%, 213/818). By elevation, 46.09% (377/818) were collected at 0–1499 m, 27.87% (228/818) at 1500–2999 m, and 26.04% (213/818) above 3000 m. The overall prevalence of rat HEV was 6.23% (51/818). Positive samples were detected in oriental house rat (

R.

tanezumi), Chevrieri's field mouse (

A. chevrieri), the large Chinese vole (

Eothenomys miletus) and black-toothedged rat (

R. andamanensiss) (

Table 1).

3.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing Rat HEV Infection in Small Mammals

Among the 818 collected small mammals tested, rat HEV prevalence varied significantly across sampling locations (χ² = 90.29,

P < 0.001). By host species, prevalence was highest in

A.

chevrieri (12.87%, 26/202), followed by

R. tanezumi (7.93%, 23/290), and other species (0.61%, 2/326), with significant interspecies differences (χ² = 34.27,

P < 0.001). Age group analysis showed prevalence rates of 14.29% (2/14) in juveniles, 3.45% (3/87) in sub-adults, and 6.42% (46/717) in adults; however, these differences were not statistically significant (χ² = 2.75,

P = 0.25). Habitat distribution revealed marked variation: 20.99% (17/81) in residential areas, 10.51% (27/257) in farming areas, 2.62% (7/267) in shrublands, and 0.00% (0/213) in forest areas (χ² = 58.30,

P < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons confirmed significant differences among habitat, with residential areas showing the highest prevalence. Prevalence also differed by elevation: 5.31% (20/377) at 0–1499 m, 13.60% (31/228) at 1500–2999 m, and 0.00% (0/213) at ≥3000 m (χ² = 38.85,

P < 0.001). The highest prevalence occurred at mid-elevation (1500–2999 m) (

Table 2).

Binary logistic regression, incorporating significant factors from univariate analysis (sampling location, species, habitat, and elevation), identified the following independent associations: the prevalence of rat HEV in small mammals from Gengma County and Heqing County was significantly higher than that in the reference group (Cangyuan County), being 8.14 times higher (95% CI: 2.90–22.87,

P < 0.001) and 4.93 times higher (95% CI: 1.97–12.32,

P < 0.001), respectively; the prevalence of rat HEV in

R. tanezumiand and

A. chevrieri were significantly higher, reaching 14.00 times (95% CI: 3.27–59.89,

P < 0.001) and 24.14 times (95% CI: 5.67–102.88,

P < 0.001), compared with other species; the prevalence of rat HEV in residential areas was significantly higher than in shrublands, with an odds ratio (OR) of 9.87 (95% CI: 3.93–24.80,

P < 0.001); the prevalence of rat HEV at mid-elevation (1500–2999 m) was significantly higher than at low elevation (0–1499 m), with an OR of 2.81 (95% CI: 1.56–5.06,

P < 0.001) (

Table 2).

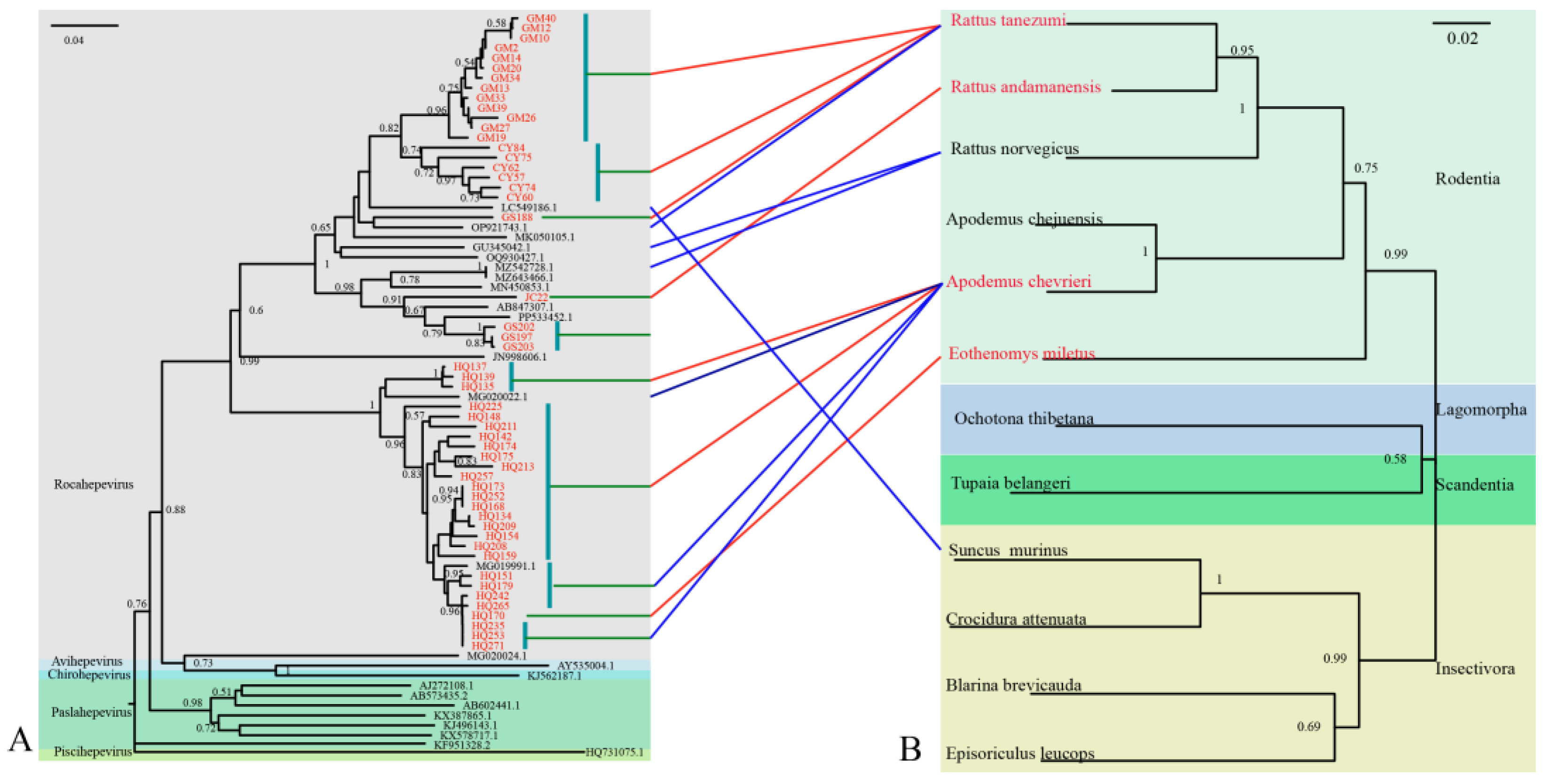

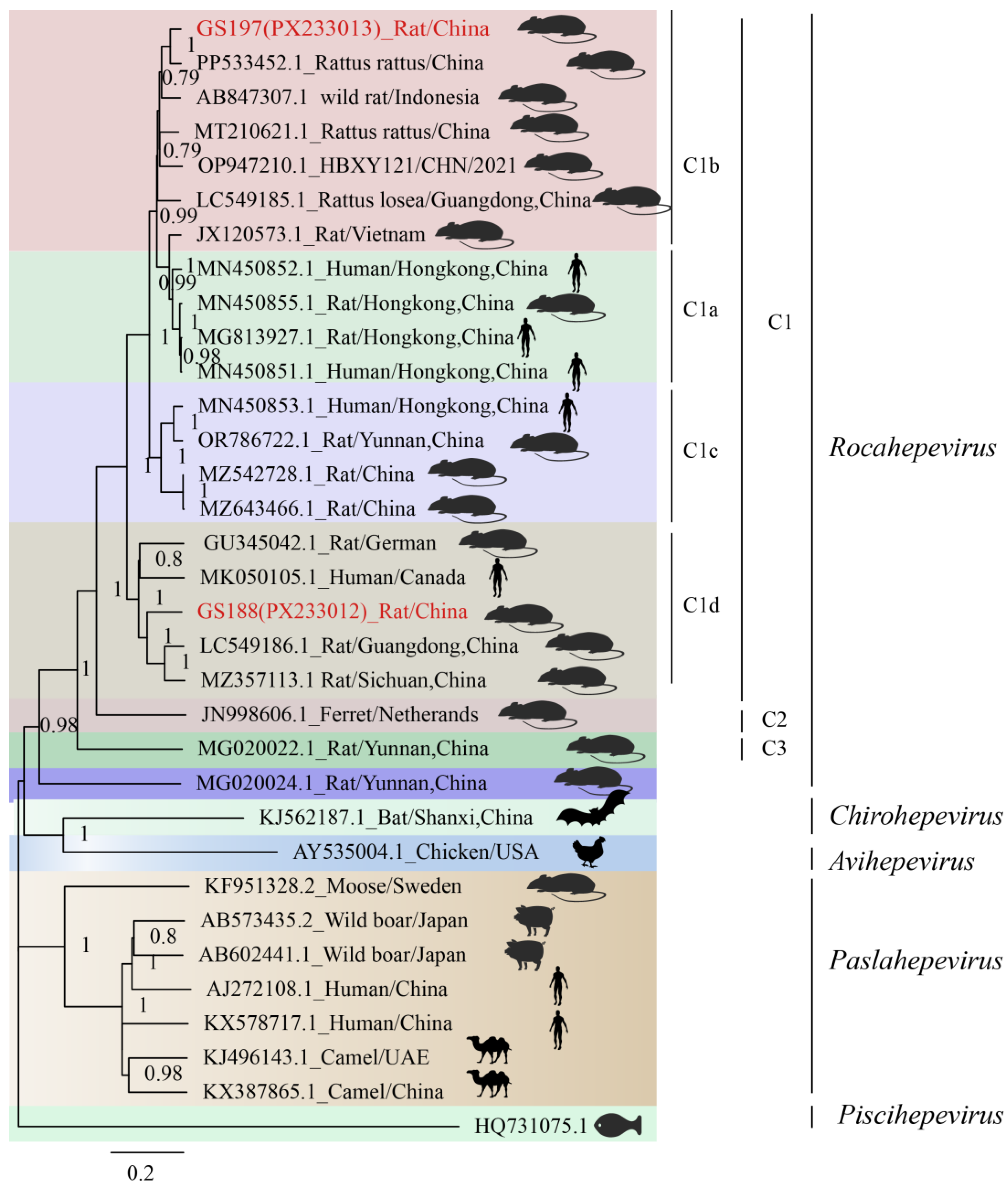

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Co-Evolution with Hosts of Rat HEV

The 51 rat HEV strains obtained in this study (GenBank accession numbers: PX233014–PX233064) exhibited nucleotide (nt) sequence homologies ranging from 64.69% to 100.00% (

Figure S1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that all strains clustered within the HEV-C1 lineage (

Figure 2). Further subtyping showed that these sequences formed two distinct subclusters: Subcluster I comprised 27 sequences with nt identities of 72.41%–100.00%, including one strain from

E. miletusand and 26 strains from

A. chevrieri, all detected in Heqing County. These clustered closely with rat HEV strains from

A. chevrieri in in Lijiang, Yunnan (GenBank accession no. MG020002). Subcluster II contained 24 sequences, among which were three strains (GS197, GS202, and GS203 from

R. tanezumi) clustered with strain JC22 from

R. nitidus in Yunnan and a human HEV strain from Hong Kong (GenBank accession no. MN450544). The remaining 19 strains from

R. tanezumi were closely related to a shrew-derived HEV strain from Guangdong (GenBank accession no. LC549186) and a human strain from Canada (GenBank accession no. MK050105) [

33].

Comparison of HEV and host phylogenetic trees demonstrated greater identity among strains originating from the same host species. For example, the 27

A. chevrieri strains from Dali Prefecture were closely related to

A. chevrieri-derived strains from Lijiang City (GenBank accession nos. MG020002 and MG019991). Similarly, strains GM10 from

R. tanezumi in Gengma County, CY75 from

R. tanezumi in Cangyuan County, and GS188 from

R. tanezumi in Gongshan County clustered tightly together. Nevertheless, exceptions were observed among HEV strains from insectivorous hosts, which did not fully align with virus-host co-clustering patterns (

Figure 2).

3.4. Genomic Structure and Similarity Comparison of Two Full-Length Rat HEV Sequences from Rattus tanezumi

Using high-throughput sequencing, we obtained two full-length rat HEV genomes from

R. tanezumi in Gongshan County, Yunnan Province: GS188 (GenBank accession no. PX233012, 7023 bp) and GS197 (GenBank accession no. PX233013, 6971 bp). Both genomes contained the canonical ORF1–ORF3, with GS188 additionally harbored a complete ORF4 [

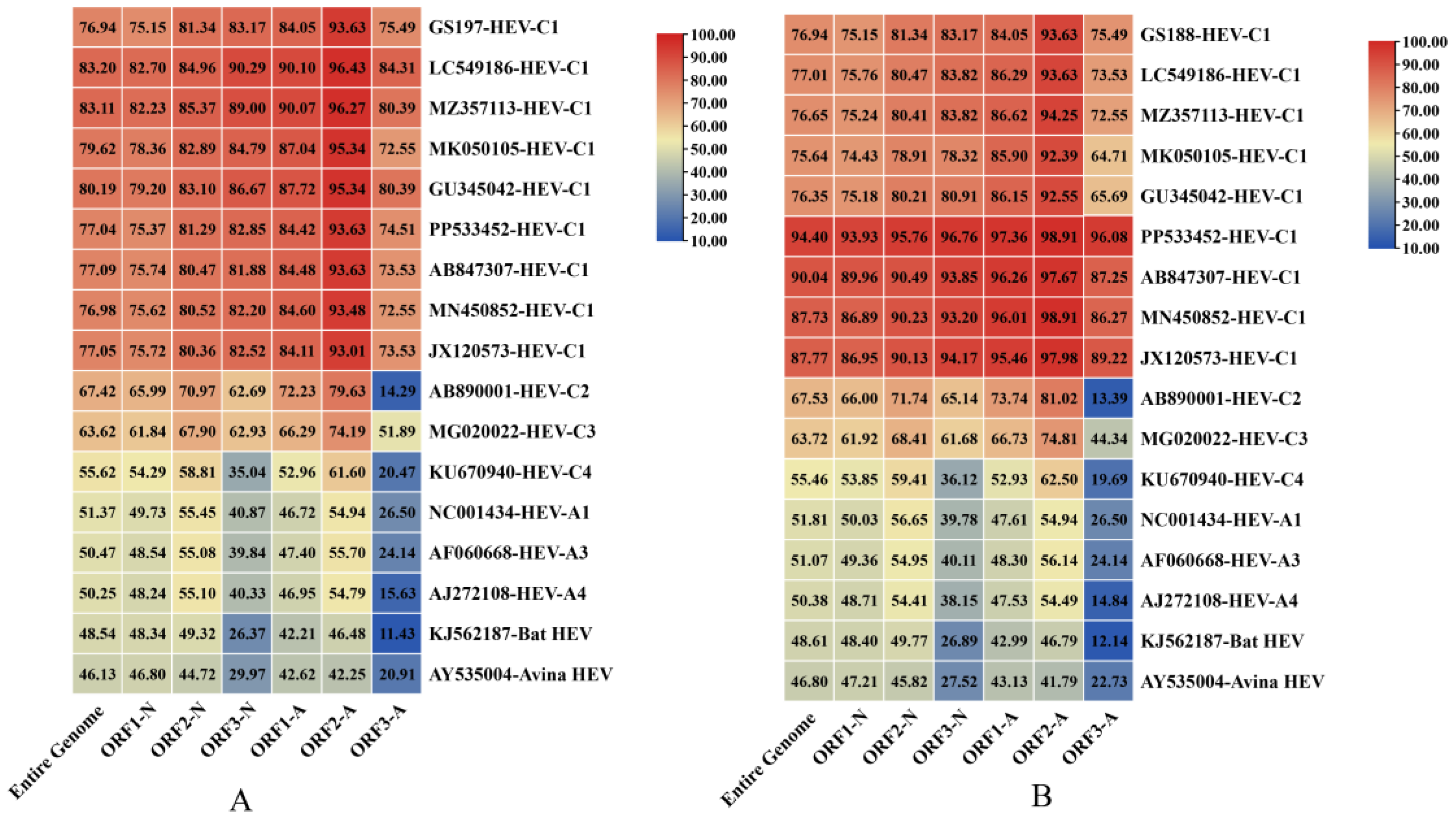

16]. Genomic alignment revealed 76.94% nt identity between GS188 and GS197. Phylogenetic analysis showed that GS188 shared 46.13%–83.20% nt identity with HEV strains available in GenBank, with the highest identity (76.94%–83.20%) observed with HEV-C1 strains. Likewise, GS197 exhibited 46.80%–94.40% nt identity with rat HEV strains in GenBank, also showing its closest relationship (75.64%–94.40%) with HEV-C1.

For ORF identities, both genomes demonstrated higher nt and amino acid (aa) sequence identity with HEV-C1 strains than with other HEV genotypes, supporting their classification within the HEV-C1 lineage. Comparative analysis further revealed that, relative to other HEV-C1 strains, ORF2 of both genomes exhibited greater nt conservation than ORF1 and ORF3. Interestingly, ORF1 and ORF2 followed a pattern in which aa identity greater than nt identity, whereas ORF3 displayed the opposite trend, with nt identity surpassing aa identity (

Figure 3).

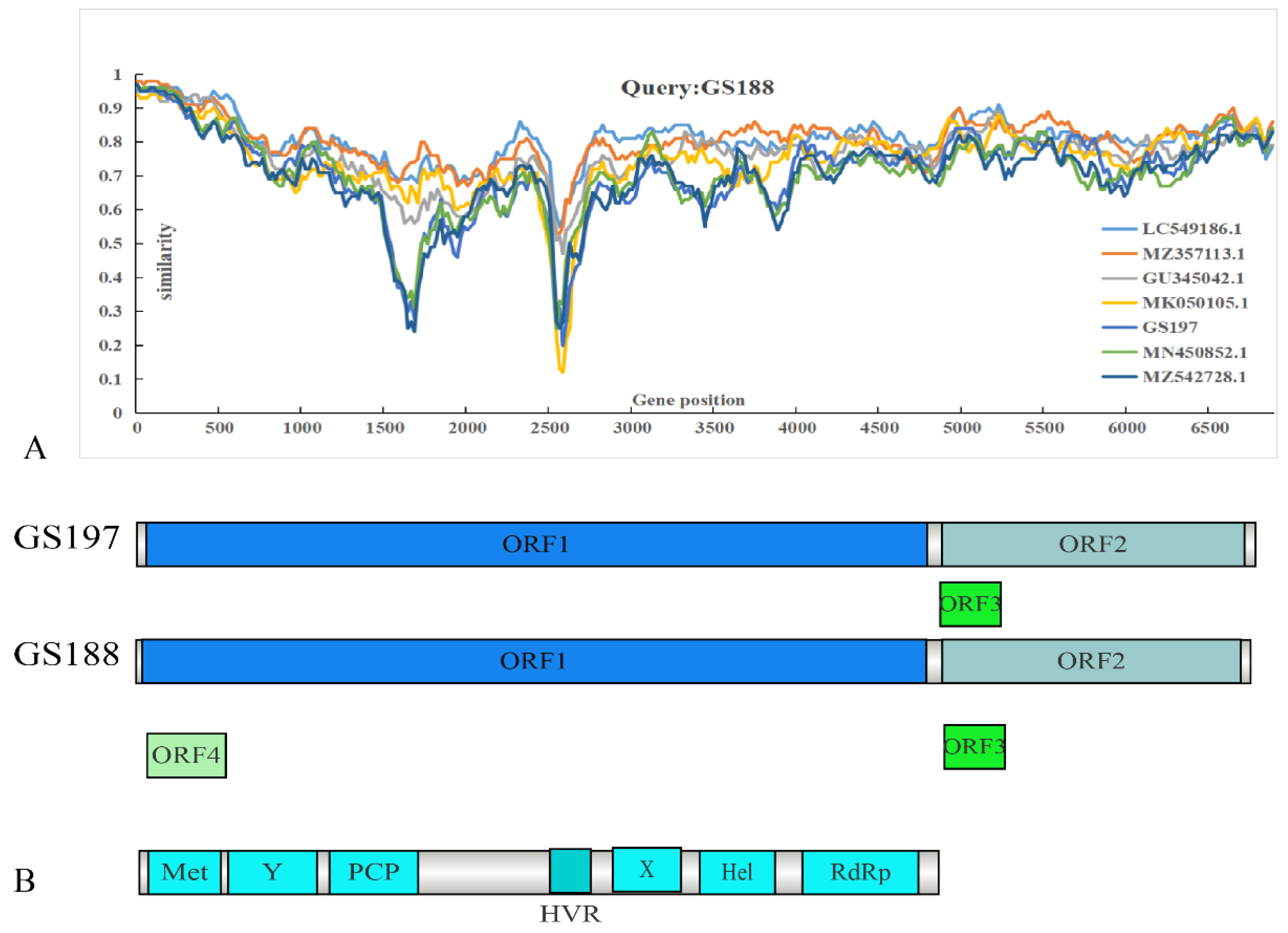

Recombination analysis using RDP4 did not reveal significant recombination events between the two rat HEV strains obtained in this study and other HEV strains. A similarity comparison was conducted using representative full-length genomes alongside the two

R. tanezumi-derived rat HEV strains from this study (

Figure 4). GS188 exhibited relatively low identity with other sequences in ORF1. Beyond the reduced identity in the hypervariable region (HVR) [

34], GS188 showed a marked decrease in identity with two human-derived HEV strains from Hong Kong and the

R. tanezumi-derived GS197 within the 1500–2000 bp segment of ORF1. In contrast, no significant decrease in identity was observed when compared to the

R. norvegicus-derived strains from Sichuan, China (GenBank accession no. MZ357113) and Germany (GenBank accession no. GU345042), or the shrew-derived strain from Guangdong, China (GenBank accession no. LC549186).

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of Two Rat HEV Strains from R. tanezumi

Phylogenetic analysis based on the full-genome sequences confirmed that both GS197 and GS188 belong to HEV-C1. According to previous studies, HEV-C1 can be further divided into four subtypes (HEV-C1a, C1b, C1c, and C1d), with GS197 and GS188 falling into different subtypes (

Figure 5). GS197, derived from

R. tanezumi in Gongshan County, Yunnan Province, formed a strongly supported clade with rat HEV strain (GenBank accession no. PP533452) from

R. rattus in China. This clade, together with rat HEV strain (GenBank accession no. MT210621) isolated from

R. norvegicus in Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China and rat HEV strain (GenBank accession no. LC549185) isolated from from

R. losea in Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China), belongs to HEV-C1b. In contrast, BLASTn analysis of GS188 showed the highest identity (83.51%) with HEV strain S1129 (GenBank accession no. LC549186) from shrews in Guangdong of China. In the full-genome phylogenetic tree, GS188 clustered within the HEV-C1d branch, together with the

R. norvegicus-derived HEV strain from Sichuan (GenBank accession no. MZ357113), the shrew-derived HEV strain from Guangdong (GenBank accession no. LC549186), and a human-derived HEV strain from Canada (GenBank accession no. MK050105), highlighting its close evolutionary relationship with strains from multiple host species.

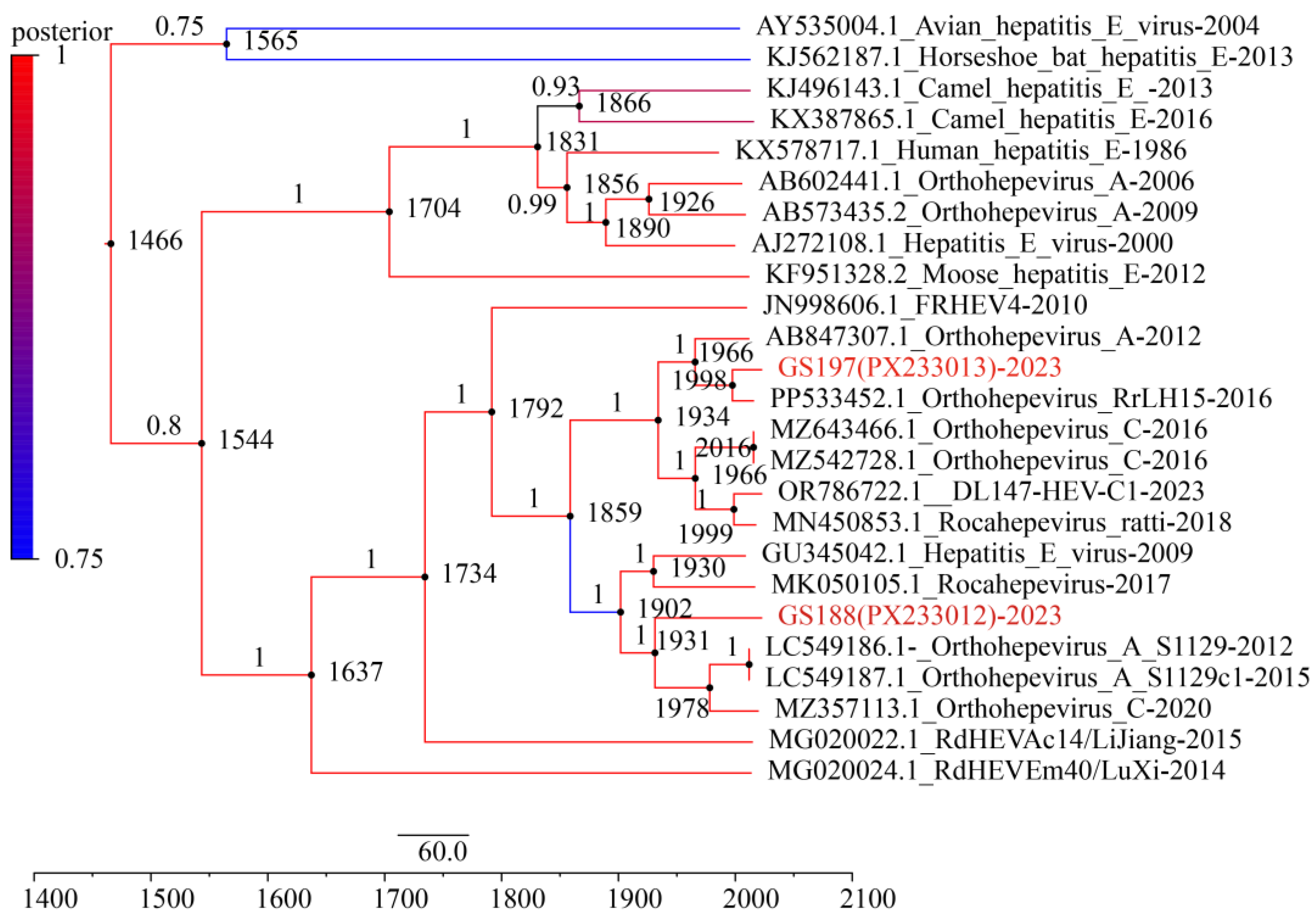

3.6. Temporal Evolution of Two Rat HEV Strains from R. tanezumi

Under an uncorrelated log-normal relaxed molecular clock model, the Bayesian Skyline analysis estimated the mean evolutionary rate of the ORF2 gene to be 9.60 × 10

-4 nt substitutions per site per year (95% Highest Posterior Density interval [HPD]: 7.68 × 10

-4–1.13 × 10

-3). The divergence time between GS197 and another

R. tanezumi-derived strain from Yunnan (GenBank accession no. PP533452) was estimated to be around 1998 (95% HPD: 1983–2003). In contrast, GS188 diverged earlier from other HEV strains, with an estimated divergence of approximately 1931 (95% HPD: 1872–1960) from HEV strain S1129 (GenBank accession no. LC549186) from the musk shrew (

Suncus murinus) in Guangdong of China and HEV strain 2PE-REP-1 (GenBank accession no. MZ375113) from the red tail toad-headed lizard (

Phrynocephalus erythrurus) in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China. Furthermore, the divergence of GS188 from HEV strain R63 (GenBank accession no. GU345042) from

R. norvegicus in German and a human-derived HEV strain 17/1683 (GenBank accession no. MK050105) from Canada, was estimated at around 1902 (95% HPD: 1885–1935) (

Figure 6). These findings indicate that GS188 represents a more ancient lineage of rat HEV, suggesting long-term evolution and potential cross-species transmission over the past century.

4. Discussion

In this study, the overall prevalence of rat HEV in small mammals was 6.23% (51/818), consistent with detection rates previously reported in Yunnan and Hubei Provinces of China and Canada [

25,

33]. The prevalence was marked higher in

A. chevrieri (12.87%) and

R. tanezumi (7.93%) compared with other species (0.61%,

P < 0.001). As a typical high-altitude species,

A. chevrieri may provide favorable ecological conditions for viral persistence, highlighting both host preference and habitat association. Our results support the hypothesis of virus-host co-adaptation, in contrast with Eastern China’s plains where

R. norvegicus is the dominant host [

35]. The complex topography and diverse habitats of Yunnan appear to create unique ecological niches sustaining rat HEV circulation.

Prevalence patterns also showed a strong gradient by habitat and elevation. Rat HEV was most frequent in residential areas (20.99%), followed by farming areas (10.51%), shrublands (2.62%), and forests (0.00%,

P < 0.001), indicating that human-associated environments drive viral amplification [

36]. This is consistent with previous work showing higher viral diversity in rodents habituating disturbed or anthropogenically modified habitats [

23]. Residential areas provide abundant food sources (e.g., household waste), shelter (e.g., building crevices), and a stable microclimate, conditions that support dense rodent populations and increase opportunities for viral transmission [

37]. Surveillance studies have also shown high genetic similarity between HEV strains in sewage and those detected in local rodents [

38], suggesting ongoing circulation at the human–wildlife interface. Moreover, pig farms frequently located near human settlements may facilitate cross-species transmission, as experimental studies demonstrate that rat HEV can infect pigs [

39], and rat HEV has been detected in European pig farms [

40]. Such a “pig–rat–human” transmission chain could serve as a bridge for zoonotic spillover [

41].

Habitat-associated variation was paralleled by altitude-related differences: prevalence was highest at mid-altitude regions (1500–2999 m, 13.60%). lower at low altitudes (0–1499 m, 5.31%), and absent at ≥ 3000 m (

P < 0.001). Mid-altitude zones host the densest human settlements and most farming activity, reinforcing the role of anthropogenic factors in shaping viral transmission risk. By contrast, high-altitude regions are relatively pristine, likely limiting rodent–human contact and viral circulation. While previous studies suggest altitude influences viral diversity in wildlife, the mechanisms remain poorly understood and warrant further investigation [

42,

43]. Overall, the elevated prevalence in residential and farming habitats underscores that small mammals adapting to human-modified landscapes are key amplifiers of rat HEV, representing hotspots for zoonotic risk [

44].

Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that all 51 HEV sequences clustered within the rat HEV clade, with clear evidence of genetic diversity, geographic clustering, and cross-species associations. Twenty-seven strains from

A. chevrieri in Heqing County, Dali Prefecture, clustered with strains from

A. chevrieri-derived strains from Lijiang, suggesting long-tern virus-host coexistence and lineage stability [

25]. By contrast, rat HEV strains GS197, GS202, and GS203 from

R. tanezumi in Gongshan County clustered JC22 from

R. nitidus from the same location and formed a branch adjacent to a human-derived strain from Hong Kong [

19]. Notably, GS197 and GS188 from

R. tanezumi also showed close genetic affinity to strains from shrews in Guangdong and human cases in Canada, as well as to

R. norvegicus strains from Germany. These findings illustrate a broad host range, intercontinental spread potential, and phylogenetic connections between rodent- and human-derived HEV strains. Together, they provide molecular evidence that rat HEV is not restricted to a single host or region but circulates across multiple mammalian species with clear zoonotic potential [

45].

Molecular clock analysis based on the ORF2 gene provided preliminary insights into the evolutionary history of RCHEV and its major lineages. Bayesian analysis estimated that the most recent common ancestor of RCHEV emerged approximately 1,637 years ago (95% HPD: 1135–1537), corresponding to roughly 4th to 16th centuries. This suggests a deep evolutionary history of RCHEV within populations. The divergence of the lineage containing GS188 (along with related strains from German rat and Canadian human case) from other related lineages occurred earlier, around 1902–1931 (approximately 93 to 122 years ago). Our molecular clock estimates reveal a key trend: the major HEV-C1 lineages currently circulating in

R. tanezumi populations Yunnan, along with clades genetically related to certain human-derived isolates, represent relatively recent divergence events that likely occurred within the past one to two centuries. This time frame aligns with a period of significant global socio-ecological transformation, including accelerated urbanization, agricultural expansion, habitat fragmentation, and increased human mobility [

44]. These anthropogenic changes have disrupted natural habitats and altered host animal behaviors, likely facilitating the spatial spread of the virus, increased interspecies contact, and an elevated viral evolutionary rate.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that human activities are the primary driver sustaining the high prevalence of rat HEV in small mammal populations, particularly with residential areas and mid-elevation zones of Southwestern Yunnan. Rat HEV in this region exhibits substantial genetic diversity and establishes extensive cross-species and cross-regional phylogenetical connections, underscoring its zoonotic potential. These findings highlight the importance of continuous rat HEV surveillance, strengthened environmental hygiene management in human settlements, and targeted control of specific reservoir host to mitigate the risk of viral emergence and spillover.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Identity comparison of nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the Rat HEV RdRp fragment in small mammals from this study. The upper right triangle of the matrix represents amino acid sequence identity (%); the lower left triangle represents nucleotide sequence identity (%).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y. and Y.-Z.Z.; methodology, Z.Y. and Y.-Z.Z.; software, Z.Y., P.-Y.H., L.-D.Z. and B.W.; validation, Z.Y., L.-D.Z.,W.K.,J.-Y.Z., Y.L.,C.-J.H.,S.W.,Y.-H.C.,W.-C.C. and Y.-Z.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Y., J.-Y.Z.,Y.L.,C.-J.H.,S.W.,Y.-H.C.,W.-C.C. W.K. and B.W.; investigation, Z.Y.,P.-Y.H.,L.-D.Z., Y.L.,C.-J.H.,S.W.,Y.-H.C.,W.-C.C. and W.K.; resources, Z.Y.,P.-Y.H., J.-Y.Z., W.K. and Y.-Z.Z.; data curation, Z.Y. and Y.-Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y. and Y.-Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.W., and Y.-Z.Z.; supervision, Y.-Z.Z.; project administration, Y.-Z.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.-Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (No. GZNL2023A01001); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2002218); Yunnan Health Training Project of High Level Talents (No. L-2017027); Cross-border Control and Quarantine Innovation Group of Zoonosis of Dali University (No. ZKPY2019302).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The relevant materials involving animal biomedical research were reviewed by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dali University, and it is considered that the project conforms to medical ethics (2021-PZ-177).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author in a reasonable manner. All sequences referenced in this article are retrievable from the NCBI database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 1 August 2026).

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the staff of the following County Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Yunnan Province for their field assistance during the sampling campaign: Heqing, Lushui, Gongshan, Jiangcheng, Gengma, Cangyuan, and Maguan

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.J. Structural and molecular biology of hepatitis E virus. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimgaonkar, I.; Ding, Q.; Schwartz, R.E.; Ploss, A. Hepatitis E virus: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Ma, Z.; Bramer, W.M.; Cao, W.; de Man, R.A.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Pan, Q. The global epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int 2020, 40, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Johne, R.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, E.; Schemmerer, M.; Wenzel, J.J.; Hofmann, J.; Shih, J.W.K.; Wedemeyer, H.; et al. Hepatitis E: An update on One Health and clinical medicine. Liver Int 2021, 41, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamar, N.; Abravanel, F.; Lhomme, S.; Rostaing, L.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis E virus: chronic infection, extra-hepatic manifestations, and treatment. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015, 39, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Li, W.; Heffron, C.L.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Wang, B.; LeRoith, T.; Meng, X.J. Antiviral resistance and barrier integrity at the maternal-fetal interface restrict hepatitis E virus from crossing the placental barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2501128122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tian, D.; Sooryanarain, H.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Heffron, C.L.; Hassebroek, A.M.; Meng, X.J. Two mutations in the ORF1 of genotype 1 hepatitis E virus enhance virus replication and may associate with fulminant hepatic failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2207503119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Li, W.; Heffron, C.L.; Wang, B.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Sooryanarain, H.; Hassebroek, A.M.; Clark-Deener, S.; LeRoith, T.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E virus infects brain microvascular endothelial cells, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and invades the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2201862119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdy, M.A.; Drexler, J.F.; Meng, X.J.; Norder, H.; Okamoto, H.; Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Reuter, G.; de Souza, W.M.; Ulrich, R.G.; Smith, D.B. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Hepeviridae 2022. J Gen Virol 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, X.L. Chirohepevirus from Bats: Insights into Hepatitis E Virus Diversity and Evolution. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cronin, P.; Mah, M.G.; Yang, X.L.; Su, Y.C.F. Genetic Diversity and Molecular Evolution of Hepatitis E Virus Within the Genus Chirohepevirus in Bats. Viruses 2025, 17, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, O.A.; Harms, D.; Wang, B.; Opaleye, O.O.; Adesina, O.; Osundare, F.A.; Ogunniyi, A.; Naidoo, D.; Devaux, I.; Wondimagegnehu, A.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Hepatitis E Virus Genotype 1e Strain from an Outbreak in Nigeria, 2017. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Akanbi, O.A.; Harms, D.; Adesina, O.; Osundare, F.A.; Naidoo, D.; Deveaux, I.; Ogundiran, O.; Ugochukwu, U.; Mba, N.; et al. A new hepatitis E virus genotype 2 strain identified from an outbreak in Nigeria, 2017. Virol J 2018, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Li, W.; Heffron, C.L.; Tian, D.; Hassebroek, A.M.; LeRoith, T.; Meng, X.J. Ribavirin Treatment Failure-Associated Mutation, Y1320H, in the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase of Genotype 3 Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) Enhances Virus Replication in a Rabbit HEV Infection Model. mBio 2023, 14, e0337222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E virus: host tropism and zoonotic infection. Curr Opin Microbiol 2021, 59, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johne, R.; Heckel, G.; Plenge-Bonig, A.; Kindler, E.; Maresch, C.; Reetz, J.; Schielke, A.; Ulrich, R.G. Novel hepatitis E virus genotype in Norway rats, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 1452–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Harms, D.; Yang, X.L.; Bock, C.T. Orthohepevirus C: An Expanding Species of Emerging Hepatitis E Virus Variants. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, S.; Yip, C.C.Y.; Wu, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, A.J.; Leung, K.H.; Chung, T.W.H.; Chan, J.F.W.; Chan, W.M.; Teng, J.L.L.; et al. Rat Hepatitis E Virus as Cause of Persistent Hepatitis after Liver Transplant. Emerg Infect Dis 2018, 24, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Yip, C.C.Y.; Lo, K.H.Y.; Wu, S.; Situ, J.; Chew, N.F.S.; Leung, K.H.; Chan, H.S.Y.; Wong, S.C.Y.; Leung, A.W.S.; et al. Hepatitis E Virus Species C Infection in Humans, Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis 2022, 75, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero-Gomez, J.; Pereira, S.; Rivero-Calle, I.; Perez, A.B.; Viciana, I.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Rios-Munoz, L.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Aguilera, A.; Rivero, A. Acute Hepatitis in Children Due to Rat Hepatitis E Virus. J Pediatr 2024, 273, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares-Jimenez, M.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Lopez-Lopez, P.; Montes, M.L.; Navarro-Soler, R.; Peraire, J.; Espinosa, N.; Aleman-Valls, M.R.; Garcia-Garcia, T.; Caballero-Gomez, J.; et al. Rat hepatitis E virus (Rocahepevirus ratti) in people living with HIV. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024, 13, 2295389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Yin, J.; Fan, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Substantial spillover burden of rat hepatitis E virus in humans. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, Y.; Tendu, A.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Mastriani, E.; Lan, J.; Catherine Hughes, A.; Berthet, N.; Wong, G. Viral diversity in wild and urban rodents of Yunnan Province, China. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024, 13, 2290842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcatty, T.Q.; Pereyra, P.E.R.; Ardiansyah, A.; Imron, M.A.; Hedger, K.; Campera, M.; Nekaris, K.A.; Nijman, V. Risk of Viral Infectious Diseases from Live Bats, Primates, Rodents and Carnivores for Sale in Indonesian Wildlife Markets. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Wang, B.; Han, P.Y.; Li, B.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, H.M.; Zong, L.D.; Tang, Y.; Shi, Z.L.; et al. Identification of novel rodent and shrew orthohepeviruses sheds light on hepatitis E virus evolution. Zool Res 2025, 46, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, C.; Bi, Y.; Long, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, F. Characterization of hepatitis E virus infection in tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis). BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhou, J.H.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.H.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.X.; Bock, C.T.; Shi, Z.L.; et al. Chevrier's Field Mouse (Apodemus chevrieri) and Pere David's Vole (Eothenomys melanogaster) in China Carry Orthohepeviruses that form Two Putative Novel Genotypes Within the Species Orthohepevirus C. Virol Sin 2018, 33, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, X.L.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ge, X.Y.; Zhang, L.B.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Bock, C.T.; Shi, Z.L. Detection and genome characterization of four novel bat hepadnaviruses and a hepevirus in China. Virol J 2017, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Kong, Y.C.; Tian, J.W.; Han, P.Y.; Wu, S.; He, C.J.; Ren, T.L.; Wang, B.; Qin, L.; Zhang, Y.Z. Molecular Epidemiology and Genetic Diversity of Orientia tsutsugamushi From Patients and Small Mammals in Xiangyun County, Yunnan Province, China. Vet Med Sci 2025, 11, e70573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.Y.; Xu, F.H.; Tian, J.W.; Zhao, J.Y.; Yang, Z.; Kong, W.; Wang, B.; Guo, L.J.; Zhang, Y.Z. Molecular Prevalence, Genetic Diversity, and Tissue Tropism of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals from Yunnan Province, China. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cai, C.L.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.H.; Zhuo, F.; Shi, Z.L.; Yang, X.L. Detection and characterization of three zoonotic viruses in wild rodents and shrews from Shenzhen city, China. Virol Sin 2017, 32, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Harms, D.; Papp, C.P.; Niendorf, S.; Jacobsen, S.; Lutgehetmann, M.; Pischke, S.; Wedermeyer, H.; Hofmann, J.; Bock, C.T. Comprehensive Molecular Approach for Characterization of Hepatitis E Virus Genotype 3 Variants. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.J.; Borlang, J.; Himsworth, C.G.; Pearl, D.L.; Weese, J.S.; Dibernardo, A.; Osiowy, C.; Nasheri, N.; Jardine, C.M. Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Norway Rats, Ontario, Canada, 2018-2021. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 1890–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Subramaniam, S.; Tian, D.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Heffron, C.L.; Meng, X.J. Phosphorylation of Ser711 residue in the hypervariable region of zoonotic genotype 3 hepatitis E virus is important for virus replication. mBio 2024, 15, e0263524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wen, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, M.; Chen, Q. The prevalence and genomic characteristics of hepatitis E virus in murine rodents and house shrews from several regions in China. BMC Vet Res 2018, 14, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Singleton, G.R.; Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit Rev Microbiol 2009, 35, 221–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sabato, L.; Monini, M.; Galuppi, R.; Dini, F.M.; Ianiro, G.; Vaccari, G.; Ostanello, F.; Di Bartolo, I. Investigating the Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) Diversity in Rat Reservoirs from Northern Italy. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, K.K.; Boley, P.A.; Lee, C.M.; Khatiwada, S.; Jung, K.; Laocharoensuk, T.; Hofstetter, J.; Wood, R.; Hanson, J.; Kenney, S.P. Rat hepatitis E virus cross-species infection and transmission in pigs. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Munoz, L.; Gonzalvez, M.; Caballero-Gomez, J.; Castro-Scholten, S.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Agullo-Ros, I.; Corona-Mata, D.; Garcia-Bocanegra, I.; Lopez-Lopez, P.; Fajardo, T.; et al. Detection of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs, Spain, 2023. Emerg Infect Dis 2024, 30, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero-Gomez, J.; Garcia-Bocanegra, I.; Cano-Terriza, D.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Jimenez-Ruiz, S.; Risalde, M.A.; Rios-Munoz, L.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Rivero, A. Zoonotic rat hepatitis E virus infection in pigs: farm prevalence and public health relevance. Porcine Health Manag 2025, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Luo, C.F.; Xiang, R.; Min, J.M.; Shao, Z.T.; Zhao, Y.L.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.S.; et al. Host taxonomy and environment shapes insectivore viromes and viral spillover risks in Southwestern China. Microbiome 2025, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Hu, S.J.; Lin, X.D.; Tian, J.H.; Lv, J.X.; Wang, M.R.; Luo, X.Q.; Pei, Y.Y.; Hu, R.X.; Song, Z.G.; et al. Host traits shape virome composition and virus transmission in wild small mammals. Cell 2023, 186, 4662–4675 e4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.; Murray, K.A.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Morse, S.S.; Rondinini, C.; Di Marco, M.; Breit, N.; Olival, K.J.; Daszak, P. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.K.; Anzolini Cassiano, M.H.; de Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Brunink, S.; Yansanjav, A.; Yihune, M.; Koshkina, A.I.; Lukashev, A.N.; Lavrenchenko, L.A.; Lebedev, V.S.; et al. Ancient evolutionary origins of hepatitis E virus in rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2413665121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).