1. Introduction

Acute episodes of lower urinary tract infections (LUTI) are among the most prevalent bacterial infections in women and typically present with dysuria, frequency, and urgency [

1]. LUTI can be presented as both acute sporadic (AC) and recurrent cystitis (RC). RC is defined as at least two episodes within six months or three episodes within one year, and may remain for decades, impairing patients’ quality of life by affecting social and sexual relationships, self-esteem, work productivity, and increasing healthcare burden on society [

2,

3].

Patients with RC receive numerous courses of antibiotics, which put them at risk of developing resistant pathogens that require treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics with unwanted collateral damage [

4]. To counteract this trend and adhere to antibiotic stewardship principles, the medical community has developed new strategies against LUTI, such as avoiding antibiotic treatment by using non-antibiotic therapy only (e.g., NSAIDs), delayed antimicrobial therapy, and replacing empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics with tailored treatment based on urine culture and susceptibility testing [

5,

6,

7,

8]. To prevent recurrences, patients might be offered prophylactic measures with nutraceuticals, antiadhesives, hormone replacement or antibiotics, although some interventions have recently failed to show efficacy in randomized controlled trials [

9]. Today, treatment and diagnostic evaluation of LUTI are differentiated depending on whether the acute cystitis is sporadic or recurrent [

1].

A key feature in the diagnostic work-up and the prevention of recurrences is the identification of factors that predispose for infection, increase the risk of a more severe outcome, and demand a longer treatment period [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Various classifications of risk factors have been suggested to ensure a comprehensive patient evaluation in the search for risk factors that can be eliminated (LUTIRE-nomogram; ORENUC-classification) [

11,

12]. Hitherto, evaluation of risk factors has mainly been discussed in patients with severe upper-tract UTI, but there is also a spectrum of risk factors for patients with less severe lower-tract UTI. Recent reviews highlight the role of host immune mechanisms and genetic susceptibility in recurrent UTI, suggesting differences in innate immunology between patients with AC and RC [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The present analytical study aimed to improve individualized management of cystitis by identifying patients at risk of recurrence, refining diagnostic evaluation, and informing tailored preventive measures. The prioritized objective was to determine the factors that distinguish AC from RC.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

The primary study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Justus-Liebig University of Giessen, Germany (AZ.:10/15, August 4, 2015) [

12]. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to enrollment. Personal data was anonymized in accordance with data protection regulations [

18].

Study Design and Definitions

This post-hoc analysis was based on data from the multinational, prospective non-interventional Global Prevalence Study of Infections in Urinary tract in Community Setting (GPIU.COM) on the epidemiology of AC in community-based healthcare settings [

19]. Women aged 16 years and older presenting with a suspected acute episode of lower UTI were recruited from outpatient clinics in Germany and Switzerland between July 2016 and February 2023. The diagnosis of an acute episode of lower UTI was based on symptoms, relevant medical history, and either a positive midstream urine dipstick test showing ≥25 white blood cells (WBC)/µL by leucocyte esterase, and/or a positive urine culture yielding >102 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of a uropathogen. Recurrence was defined as two or more acute episodes of lower UTI within the preceding six months or three or more acute episodes within the preceding 12 months [

1]. Recurrence data were obtained from patient self-reports and medical records. Treatment and follow-up have not been evaluated in the present study.

Study Population and Risk Factor Evaluation

At study entry, patients completed a paper study report form (SRF) on demographics, medical history and medications. To evaluate lower UTI symptoms and their impact on quality of life, all respondents completed the validated German versions of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) and the 3-Level Version of the EuroQoL 5-Dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) [

20,

21]. Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were recorded at the first visit. All patients underwent clinical examination and abdominal ultrasonography by a urologist. Clean-catch midstream urine was sampled for dipstick, urine culture, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The diagnosis of AC or RC was based on symptoms, ACSS and history. Risk factors for recurrence were later assessed with the Lower Urinary Tract Infection Recurrence Risk (LUTIRE) nomogram, data from medical history, clinical examination, and ultrasonography were categorized according to the ORENUC system [

12]. While ACSS was completed by the patients, the LUTIRE nomogram and the ORENUC categories were assessed by the treating urologist.

Urinalyses and Urine Culture

Urine dipstick leucocyte esterase results were classified into five semi-quantitative levels: “Negative” (up to 10 WBC/µL), “Trace” (> 10 to 25 WBC/µL), “Small (1+)” (> 25 to 50 WBC/µL), “Moderate (2+)” (> 50 to 100 WBC/µL), and “Large (3+)” (> 100 WBC/µL) [

22]. Counts of the colony-forming units (CFU) on the urine culture were categorized into six groups: 10² CFU/mL, 10³ CFU/mL, 10⁴ CFU/mL, 10⁵ CFU/mL, 10⁶ CFU/mL, and >10⁶ CFU/mL. CFU counts up to 10² CFU/mL were considered insignificant. Uropathogens with intrinsic resistance to specific antimicrobials were not tested against those agents, in line with the Expert Rules of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [

23,

24].

Statistical Evaluation

Sample size was calculated using Cochrane’s formula for descriptive and cross-sectional studies [

25].

Data were entered into an online database designed for the GPIU.COM-Study via electronic case report forms (eCRFs). Only fully completed forms were considered eligible for further data processing. Data were analyzed using a pre-specified, robust stepwise procedure (

Table 1), with sequential exclusion of non-significant variables (p >0.05) at each stage to obtain the most parsimonious and best-fitting model. Statistical significance was set at the cut-off point of the P-value at 0.05.

Analysis and graphical representation of the results were performed using R-Studio, integrated with R v.3.5.2 and related packages [

26]. Normality of variables was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots [

27]. Homogeneity of variances was examined using Levene’s test [

28]. Numerical values were summarized as appropriate measures of central tendency and dispersion (e.g., mean, median, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, interquartile range). Categorical variables were reported in proportions.

Between-group comparisons included univariate parametric or non-parametric tests, depending of the nature and type of variable, normality of distribution, and frequencies of cases in the groups, including Student or Welch’s t-test, ANOVA, Wilcoxon rank-sum, Pearson’s chi-squared, and Fisher’s exact proportion tests [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The null hypothesis stated that there were no differences between the groups.

P-values for multiple comparisons involving continuous or ordinal variables were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength of associations for numerical and interval variables [

35]. Association measures were expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% CIs, calculated to identify variables associated with AC or RC, with a primary focus on risk factors for developing RC. Haldane-Anscombe correction was used for contingency tables containing zero cells, to allow valid estimation of RR and CIs [

36].

Significant, non-collinear predictors were entered into univariate logistic regression (LR) models to obtain adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI and the final model equation.

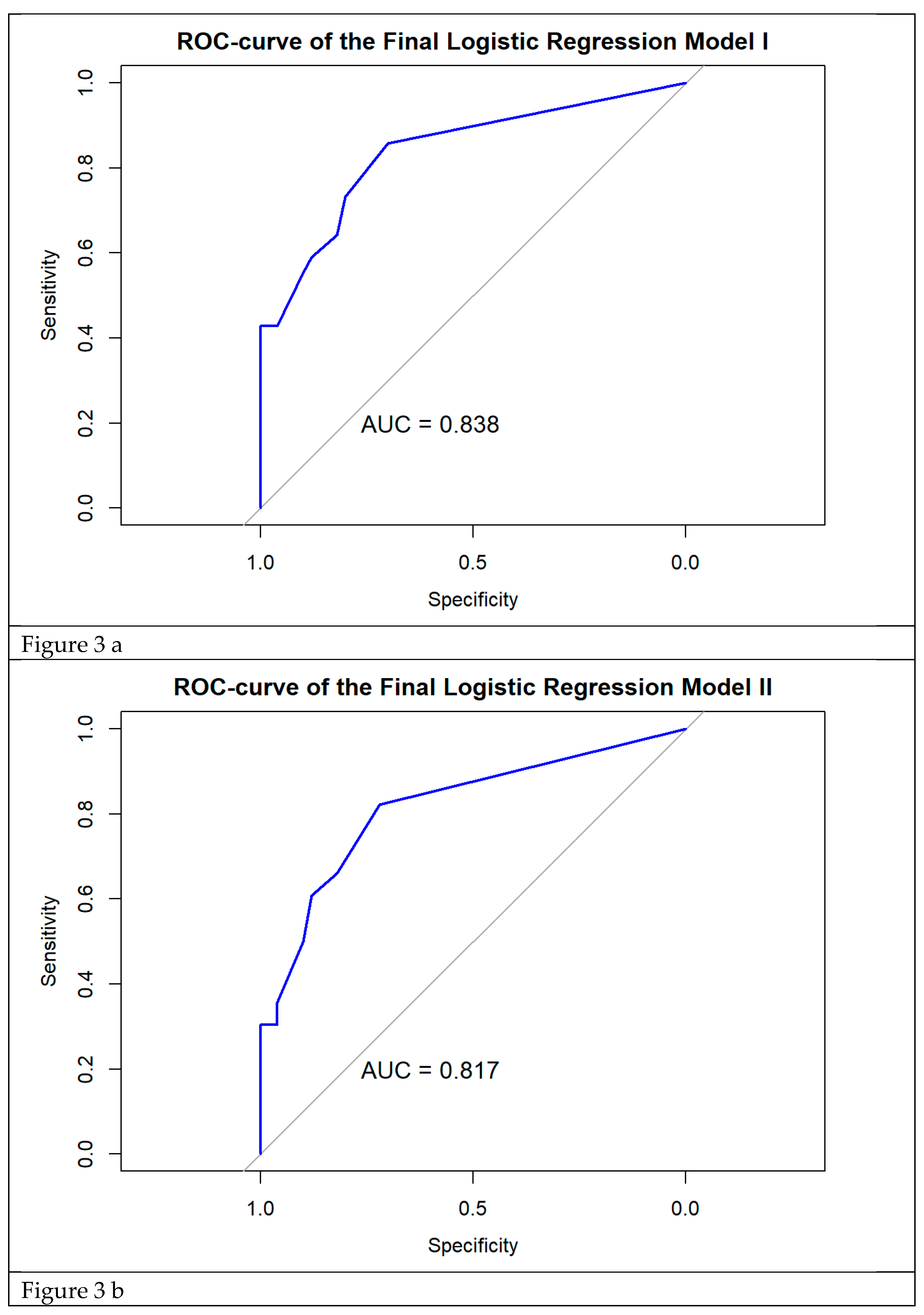

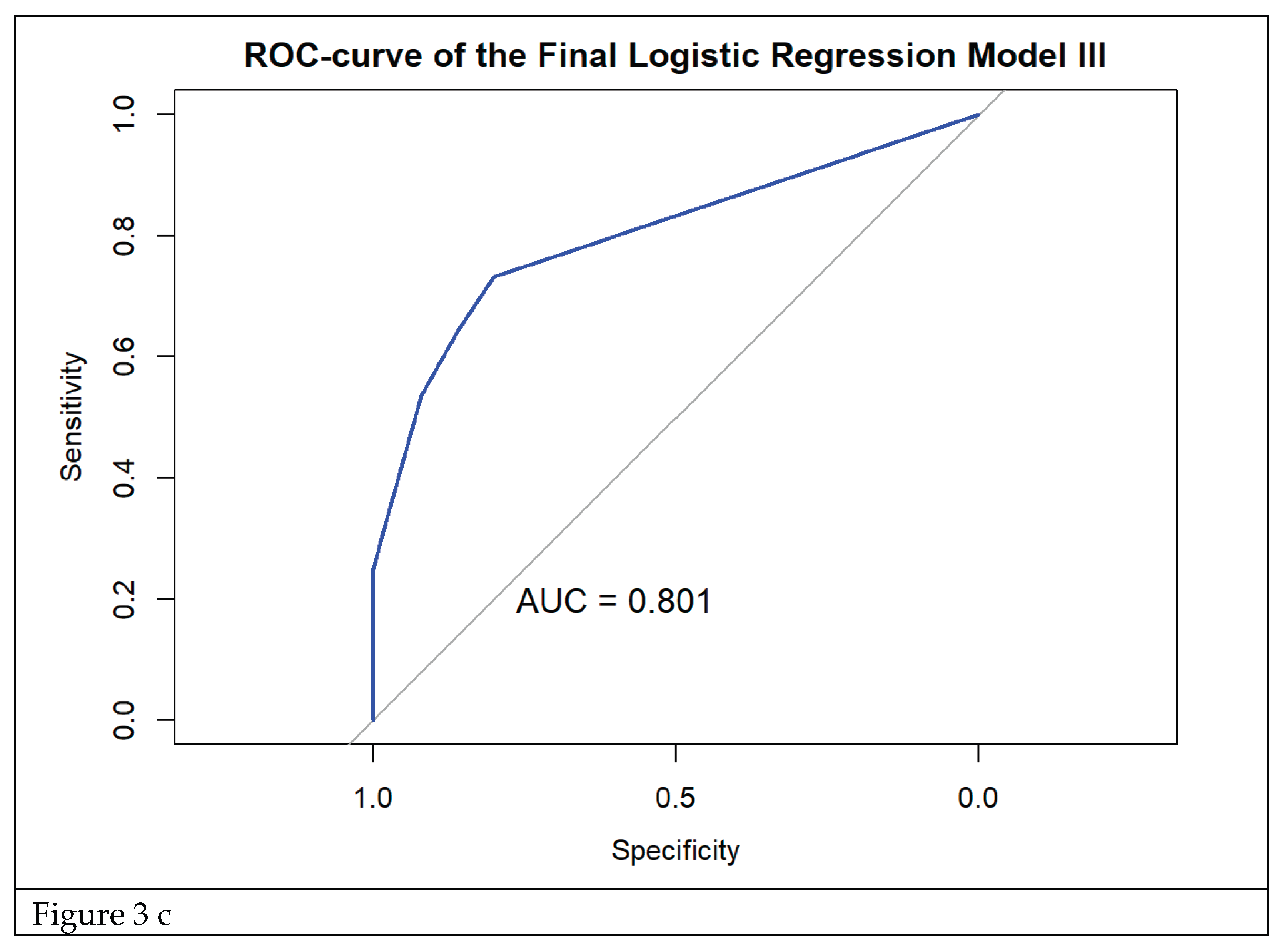

Predictors that had significant ORs in univariate LR were included in the final multivariate LR model. Model discrimination was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF).

3. Results

Clinical assessment

Demographics

157 women were recruited. Patients with incomplete data and patients who did not match the study definition of acute cystitis were excluded. Data from 106 patients were categorized into two groups: sporadic acute cystitis (AC) (n=50; 47.2%) and recurrent acute cystitis (RC) (n=56; 52.8%) and included in the final analysis. The groups were comparable for all demographic characteristics (

Table 2). The complete set of all tested variables is provided in the

supplementary materials (Suppl. Table 1).

Symptoms

Analysis of the summary scores of the 'Typical', 'Differential' and 'Quality of Life' domains of the ACSS revealed no statistically significant differences between groups (p > 0.4). However, patients with RC more frequently reported a severe impact of symptoms on their daily activities (ACSS) and experienced extreme levels of anxiety and depression (EQ-5D-3L), with a higher tendency to be confined to bed compared to those with AC (EQ-5D-3L). Results of these comparisons are detailed in

Suppl. Table 3. Symptoms with significant differences between groups are presented in

Table 3.

History and Risk Factors

While the differentiation into AC and RC based on patients` information and journal notes was straightforward, assessment according to LUTIRE and ORENUC classification revealed that patients with AC also had previous episodes with the same symptoms and had used preventive measures. Some patients with AC also had risk factors for recurrence. Opposite, while risk factors for recurrence were significantly more common among RC patients, some patients in the RC group had no known risk factors for recurrence. Use of classification instruments showed the uncertainty of differentiating AC and RC based on the patients` history only.

Patients with AC more often reported normal bowel function and patients with extra-urogenital risk factors like constipation (LUTIRE)(ORENUC-E) had 83% (15/18) chance of belonging to the RC group (two-sided P <0.05 for both comparisons) (

Table 3.)(

Suppl Table 1.). AC patients also more often reported a sense of incomplete bladder emptying on ACSS, but the urologist found no evidence of residual urine (ORENUC-U). Moreover, patients with AC reported more severe flank pain, and symptoms of menopause-related complaints (P<0.05) which did not correspond with urological (ORENUC-U) findings or factual menopause status (

Table 3). The proportion of patients who presented with multiple abnormalities was significantly higher among patients with RC indicating that individual risk factors have additive effect on the overall risk of recurrence (

Suppl.Table 2.).

The proportion of patients with a history of isolation of a Gram-negative uropathogen was significantly higher in the RC group (P<0.001) (

Table 3), whereas the proportion of Gram-positive uropathogens did not differ significantly between groups (P=0.277) (

Suppl.Table 1.).

Urinalysis and microbiological findings

Urinalysis

Patients with RC exhibited a significantly higher rate of negative leucocyte esterase tests than AC patients (17.9% vs. 4.0%), as well as a higher frequency of concurrent negative results for leucocyte esterase and nitrite tests (12.5% vs. 2.0%). Conversely, the proportion of patients with the “Moderate (2+)” level of the leucocyte esterase test was significantly higher among patients in AC group (

Table 4).

Urine Culture

Out of the 106 urine samples taken on admission from all included patients, 91 (85.8%) yielded a positive culture (CFU

>10

3/mL). Among these, a single uropathogen was isolated in 67 cultures (73.6%), while two uropathogens were isolated in 24 cultures (26.4%). In total, 119 uropathogens were isolated, 76 (63.9%) were Gram-negative and 33 (27.7%) were Gram-positive. Ten cultures (8.4%) were classified as mixed flora (

Suppl.Table 4).

Escherichia coli was the most isolated uropathogen in both groups. The prevalence was 55.6% in the AC and 41.0% in the RC group. The proportion of

E. coli isolated as the primary (first) uropathogen did not differ significantly between groups (p>0.05 for all comparisons). No significant difference was observed between the groups regarding the proportion of patients with a single uropathogen or a negative urine culture (

Suppl.Table 4). Patients with RC had a significantly higher rate of multiple uropathogens compared to those with AC (31.3% vs. 6.8%) (P<0.05) (

Table 4,

Suppl. Table S4.

Non-susceptibility rates of all primary uropathogens to tested antimicrobials were significantly higher in the AC group, whereas non-susceptibility of

E. coli to second-generation cephalosporins was higher in the RC group. No statistically significant differences in fluoroquinolone non-susceptibility rates were observed between groups (

Suppl.Table 4).

Statistical analysis

Weighting of Risk Factors Based on Relative Risk (RR)

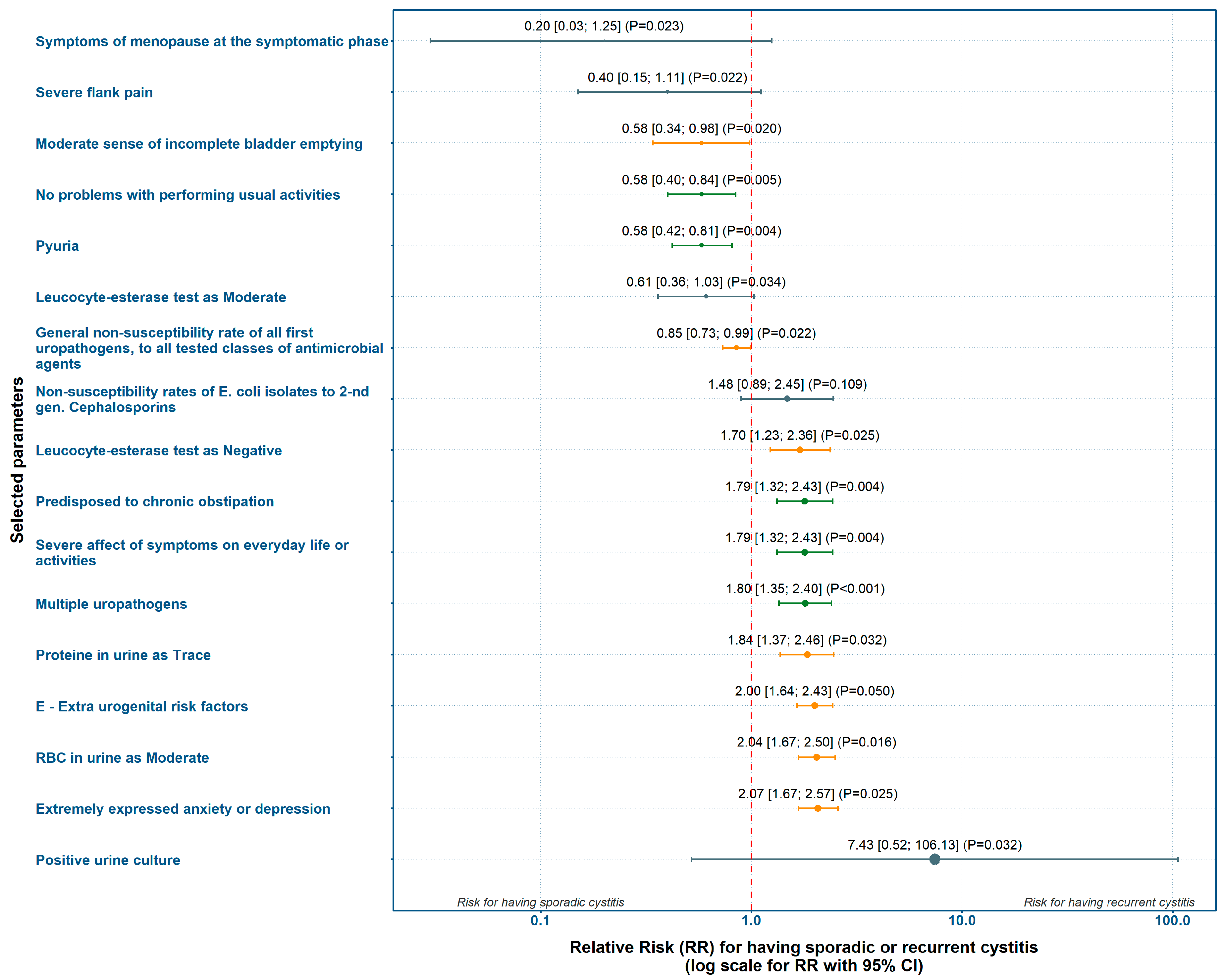

Based on the incidence of risk factors with statistically significant differences between groups, we calculated point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for RR and presented them in a forest-plot (

Figure 1.). Variables which directly influenced the study’s definition of recurrence were manually excluded. These were the number of previous symptomatic UTI episodes, prior prophylactic measures and antimicrobial treatments, the LUTIRE recurrence probability and the "O" and "R" criteria from the ORENUC classification.

Absence of problems with daily activities according to ACSS, and presence of pyuria were most strongly associated with AC. Conversely, chronic constipation (LUTIRE-nomogram), extra-urogenital risk factors (ORENUC E-category), negative leucocyte esterase test, moderate level of red blood cells in urine, and reporting extreme anxiety or depression (EQ-5D-3L) showed the strongest weight for RC (

Figure 1,

Suppl. Table S5).

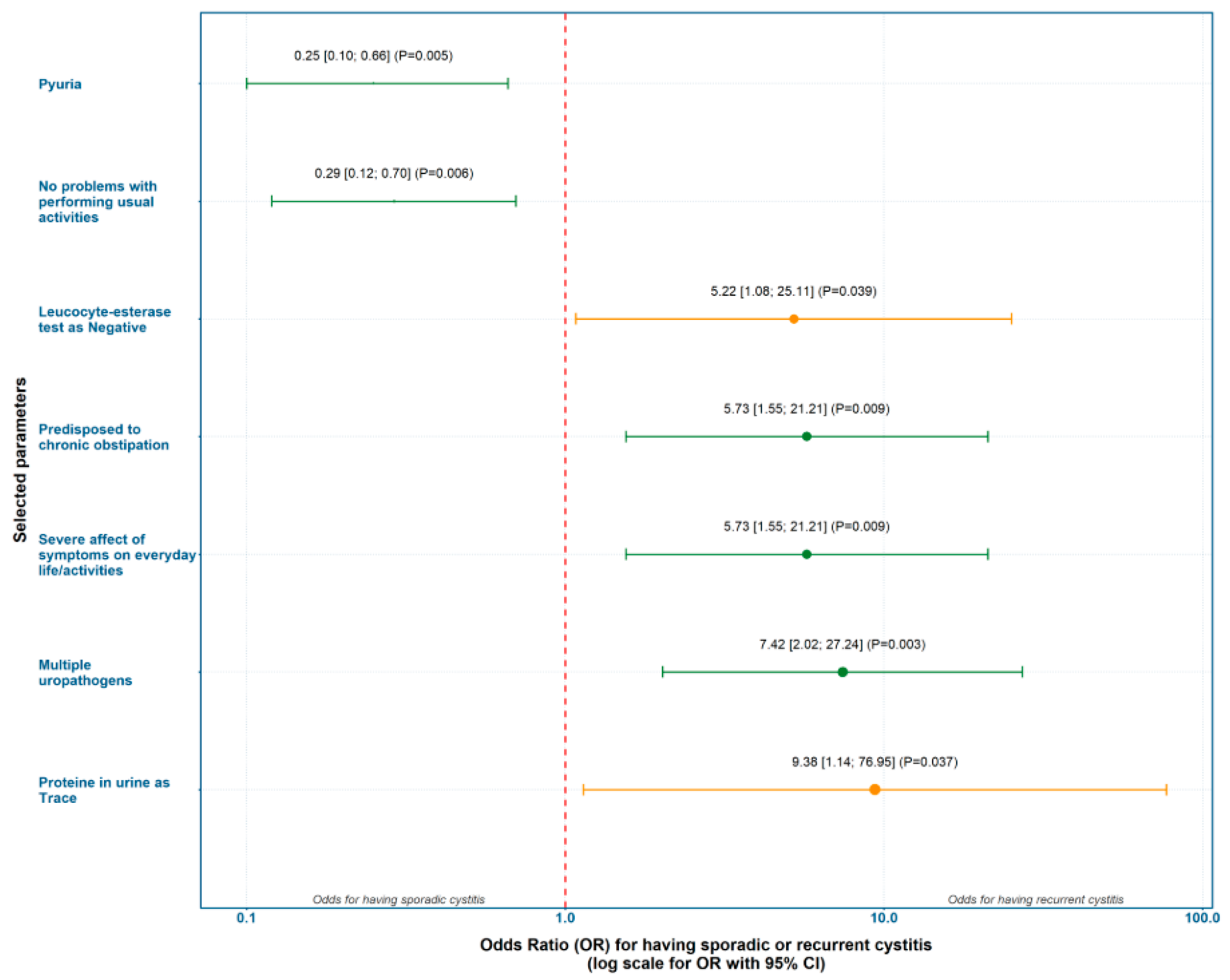

Evaluation of Predicting Factors for Recurrent Cystitis Based on Odds Ratio (OR)

The clinical, laboratory, and microbiological parameters that showed significant relative risk ratios for either the AC or the RC group were selected for further analyses. Based on the incidence of risk factors with statistically significant differences between groups, we calculated ORs with 95% CI and performed univariate logistic regression. The strongest predictors for AC were pyuria and absence of problems with performing usual activities. The strongest predictors for RC were trace proteinuria and the presence of multiple uropathogens (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Main Findings

We assessed patients with acute cystitis by means of ACSS, LUTIRE and the ORENUC classification and found that 14% of patients considered to have AC reported a similar symptomatic episode within the preceding 6 months and 74% had used preventive measures against acute cystitis. Patients with AC more often reported severe flank pain, moderate sense of incomplete bladder emptying and menopause-related complaints, which did not correspond with urological (ORENUC-U) findings or factual menopause status.

Patients with RC more frequently reported a severe impact of symptoms on their daily activities and experienced extreme levels of anxiety and depression, with a higher tendency to be confined to bed. All patients with extra-urogenital risk factors according to ORENUC, and 63% of all patients in the study population with urological abnormalities belonged to the RC group. All patients with more than one ORENUC risk category, except O or R, also had RC. Patients in the RC group more frequently had a history of Gram-negative uropathogen isolation and more frequently had Gram-positive uropathogens isolated on admission. In cases with multiple uropathogens, patients with RC had a significantly higher prevalence of Enterococcus species as the second uropathogen with higher colony counts compared to those with AC.

Logistic regression of odds ratios showed that the strongest predictors for AC were pyuria and the absence of problems with performing usual activities. The strongest predictors for RC were trace proteinuria and the presence of multiple uropathogens. Three constructed prediction models showed consistent results, highlighting constipation, severe impact of symptoms on everyday activities, and the presence of multiple uropathogens as the strongest set of independent risk factors for RC, while pyuria was inversely associated with AC.

Methodological Aspects

This is the first time patients with acute cystitis are evaluated for risk factors according to the combined use of ACSS, LUTIRE and the ORENUC classification. While patients with AC report severe flank pain, the urologists found no fever, flank tenderness or dilatation on ultrasonography and hence could rule out pyelonephritis. Likewise, some patients reported feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, but the urologist found no residual urine. While patients with AC reported symptoms of menopause, the ACSS did not register the hormonal status of menopause, but this information was picked up by LUTIRE. When developing the LUTIRE nomogram, Cai et al. found that hormonal status and constipation had the highest predictive value for recurrence [

11]. They also found the type of previously isolated pathogens to be important. This is consistent with our findings. Other important factors identified by Cai et al were the number of sexual partners and previous treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. We did not identify these risk factors in our study. On the other hand, Cai et al. did not identify risk factors in the ORENUC E-category, which in our study were endometriosis, immunosuppression, entero-vesical fistula, multiple sclerosis and one “other”.

Our findings highlight differences and limitations in the reporting of risk factors by patients and urologists. We therefore argue that risk factors with the highest predictive value for RC from ACSS, LUTIRE and ORENUC should be combined in a comprehensive prognostic evaluation tool. The current differentiation of acute cystitis into AC and RC should be replaced by a new description of acute cystitis with a grading of the risk of recurrence like we do in bladder cancer [

37].

Context and Clinical Impact

Our results underline the importance of a thorough anamnesis and clinical examination with evaluation of extra-urogenital, nephrological and urological risk factors. The presence of risk factors can help the clinician decide which type of cystitis the patient has and the risk of recurrence. Microbiological results add value to the differentiation between AC and RC. Patients with RC tend to have multiple and more resistant pathogens, which require more broad-spectrum antibiotics as compared with AC. Reporting of incomplete bladder emptying and flank pain among RC patients are arguments for having ultrasonography at hand at the initial visit. A history of constipation should cause instant guidance on lifestyle habits.

Although patients in the AC group more frequently reported menopausal symptoms and higher symptom burden, our previous studies did not demonstrate a significant association between symptom severity and findings in urinalyses and urine culture [

38,

39]. These patient complaints are arguments for expanding the ORENUC classifications of UTI with a mental domain, since menopausal symptoms and symptom burden can lead to depression and anxiety and affect daily activities and work.

Our prediction models are relevant for decision algorithms for diagnosis and treatment of acute episodes of cystitis. Model I included constipation, severe impact of symptoms on everyday activities, proteinuria, pyuria and multiple uropathogens isolated from urine. This model is most valuable when the aim is to avoid missing any RC cases, even at the cost of some over-diagnosis. Model III, which excluded pyuria, is preferable when the priority is to prevent overtreatment and support antibiotic stewardship. Model II, which excluded proteinuria, provides a balanced compromise and seems most relevant for routine clinical practice.

Strengths and Limitations

Key strengths of our study are the prospective design, inclusion of symptomatic patients only, clinical examination by a urologist at baseline, availability of urine culture tests and susceptibility data from nearly all patients, and a robust stepwise statistical evaluation. The use of standardized tools such as ACSS and categorization of laboratory assessments ensured comparability between patient groups.

A limitation of this study is that some of the predictors overlapped with diagnostic criteria, posing a risk of collinearity. We therefore excluded the most collinear factors from the final analysis. The modest sample size was compensated for by rigorous statistical methodology and appropriate corrections. Although we classified CFU counts ≤102/mL as insignificant, the use of a threshold of 103 CFU/mL may still have led to the inclusion of patients who would be considered bacteriuria-negative in other studies. Finally, as our study was limited to Germany and Switzerland, the findings may differ from those in other geographic regions with different patterns of non-susceptibility.

Future Research

Reporting of severe flank pain and moderate findings on leucocyte esterase test in AC, as opposed to a negative leucocyte esterase test, trace proteinuria and red blood cells as moderate in RC, warrants further immunological characterization of the two clinical entities. More frequent findings of multiple uropathogens more often in RC than in AC indicate different pathogenetic mechanisms. The above features may generate hypotheses of a different innate immunology in patients with AC and RC to be addressed in future studies with more specific tests [

16].

Future research should address the role of the intestinal microbiome in constipation-induced RC and explore why the bladder mucosa is more susceptible to infection in cases of poor bladder emptying. We need large prospective studies to assess the prognostic weight of individual factors and the effect of eliminating separate risk factors on recurrence rates. Our models for the identification of recurrent episodes of acute cystitis should be expanded by means of AI into larger decision algorithms to guide treatment and prevention policies.

5. Conclusions

Although both sporadic and recurrent cystitis present as acute infection of the urinary bladder, there are significant differences in symptoms, findings on urinalysis and urine culture, and risk factors according to ACSS, LUTIRE and ORENUC classifications. The most common risk factors among patients with RC are constipation and urological abnormalities. Use of risk factor classifications will ensure a comprehensive patient evaluation and help differentiate between AC and RC. The strongest predictors for sporadic cystitis are pyuria and the absence of problems with performing usual activities. The strongest predictors for recurrent cystitis are trace proteinuria and the presence of multiple uropathogens. Different findings on urinalysis and culture indicate different host reactions and pathogenetic mechanisms in the two clinical conditions and warrant further research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JA, KGN, TEBJ; Methodology: JA, KGN, FMW, TEBJ; Validation: UK, KhK, AP, TEBJ; Software, data curation, statistical analysis: JA; Original draft preparation: JA, KGN, TEBJ; Review and editing: JK, AP, TC, FMW, KGN, TEBJ; Visualization: JA, KGN; Supervision: FMW, TEBJ; Project administration: FMW, TEBJ.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The primary study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Justus-Liebig University of Giessen, Germany (AZ.:10/15, August 4, 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to enrollment. Personal data was anonymized in accordance with data protection regulations.

Funding

The GPIU.COM study was conducted under the investigator-initiated trial (IIT) grant provided by OM Pharma SA/CSL (Geneva, Switzerland) to cover the GPIU.COM web-based forms preparation, data processing and statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

JA, AP, KN and FW are the copyright holders of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS). JA is currently an employee of Bionorica SE (Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, Germany). This work was conducted in his capacity as a researcher only before joining Bionorica. The company neither funded nor influenced this research. All findings, interpretations, and conclusions are solely those of the authors and do not represent the official policy of Bionorica SE.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Acute (sporadic) cystitis |

| ACSS |

Acute Cystitis Symptom Score |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC |

Area under the (receiver-operating characteristic) curve |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CFU |

Colony-forming units |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| eCRF |

Electronic case report form |

| EAU |

European Association of Urology |

| EQ-5D-3L |

EuroQoL 5-Dimensions, 3-level version of the questionnaire |

| ESIU |

EAU Section of Infections in Urology |

| EUCAST |

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| GPIU.COM |

Global Prevalence Study of Infections in Urinary tract in Community Setting |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| LR |

Logistic regression |

| LUTI |

Lower urinary tract infection(s) |

| LUTIRE |

Lower Urinary Tract Infection Recurrence Risk (nomogram) |

| NSAIDs |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| ORENUC |

Classification system of UTI risk factors |

| RC |

Recurrent cystitis |

| RR |

Relative risk |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| SRF |

Study report form |

| UTI(s) |

Urinary tract infection(s) |

| VIF |

Variance inflation factor |

| WBC |

White blood cells |

References

- Bonkat, G., et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections, in EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Madrid 2025. 2025, EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, the Netherlands.: Madrid, Spain.

- Foxman, B. , Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med, 2002, 113 (Suppl 1A), 5S–13S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, A.L.; Bradley, M.; D’aNci, K.E.; Hickling, D.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E. Updates to Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline (2025). J. Urol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.H.; Tartof, S.Y.; Contreras, R.; Ackerson, B.K.; Chen, L.H.; Reyes, I.A.C.; Pellegrini, M.; E Schmidt, J.; Bruxvoort, K.J. Antibiotic Resistance of Urinary Tract Infection Recurrences in a Large Integrated US Healthcare System. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e1344–e1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midby, J.S.; Miesner, A.R. Delayed and Non-Antibiotic Therapy for Urinary Tract Infections: A Literature Review. J. Pharm. Pr. 2022, 37, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F.M.; Abramov-Sommariva, D.; Höller, M.; Steindl, H.; Naber, K.G. Non-Antibiotic Herbal Therapy (BNO 1045) versus Antibiotic Therapy (Fosfomycin Trometamol) for the Treatment of Acute Lower Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Randomized, Multicentre, Non-Inferiority Phase III Trial. Urol. Int. 2018, 101, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naber, K.G.; Alidjanov, J.F.; Fünfstück, R.; Strohmaier, W.L.; Kranz, J.; Cai, T.; Pilatz, A.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Therapeutic strategies for uncomplicated cystitis in women. GMS Infect Dis. 2024, 12, Doc01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, K.G.; Alidjanov, J. [Are there alternatives to antimicrobial therapy and prophylaxis of uncomplicated urinary tract infections?]. Urologiia 2016, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, G.; et al. d-Mannose for Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Among Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024, 184, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B.; Gillespie, B.; Koopman, J.; Zhang, L.; Palin, K.; Tallman, P.; Marsh, J.V.; Spear, S.; Sobel, J.D.; Marty, M.J.; et al. Risk Factors for Second Urinary Tract Infection among College Women. Am. J. Epidemiology 2000, 151, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Mazzoli, S.; Migno, S.; Malossini, G.; Lanzafame, P.; Mereu, L.; Tateo, S.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Pickard, R.S.; Bartoletti, R. Development and validation of a nomogram predicting recurrence risk in women with symptomatic urinary tract infection. Int. J. Urol. 2014, 21, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.E.B.; Botto, H.; Cek, M.; Grabe, M.; Tenke, P.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Naber, K.G. Critical review of current definitions of urinary tract infections and proposal of an EAU/ESIU classification system. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerson, B.K.; Tartof, S.Y.; Chen, L.H.; Contreras, R.; Reyes, I.A.C.; Ku, J.H.; Pellegrini, M.; E Schmidt, J.; Bruxvoort, K.J. Risk Factors for Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Among Women in a Large Integrated Health Care Organization in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e1101–e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosman, I.S.; Roić, A.C.; Lamot, L. A Systematic Review of the (Un)known Host Immune Response Biomarkers for Predicting Recurrence of Urinary Tract Infection. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 931717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, R.; Hafner, J.; Ingersoll, M.A. Immunity to urinary tract infection: What the clinician should know. CMI Commun. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godaly, G.; Ambite, I.; Svanborg, C. Innate immunity and genetic determinants of urinary tract infection susceptibility. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 28, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Lv, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, A.; Niu, H. The immune mechanisms of the urinary tract against infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1540149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

European Parliament and Council of the European Union, Directive 2001/20/EC of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. 2001.

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Khudaybergenov, U.A.; Ayubov, B.A.; Pilatz, A.; Mohr, S.; Münst, J.C.; Ziviello Yuen, O.N.; Pilatz, S.; Christmann, C.; Dittmar, F.; et al. Linguistic and clinical validation of the acute cystitis symptom score in German-speaking Swiss women with acute cystitis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidjanov, J.F. , et al., [German validation of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score]. Urologe A 2015, 54, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, R.; de Charro, F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001, 33, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimenatos, L.; Mahajan, P.; Dayan, P.S.; Vitale, M.; Linakis, J.G.; Blumberg, S.; Borgialli, D.; Ruddy, R.M.; Van Buren, J.; Ramilo, O.; et al. Accuracy of the Urinalysis for Urinary Tract Infections in Febrile Infants 60 Days and Younger. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20173068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), Expert rules and expected phenotypes. 2019 [cited 2023 May, 8]; Available from: https://www.eucast.org/expert_rules_and_expected_phenotypes.

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Vahedi, M.; Rahimzadeh, M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2013, 6, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Team, R.C.: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples)†. Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H., Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics; essays in honor of Harold Hotelling, I. Olkin, H. Hotelling, and et al., Editors. 1960, Stanford University Press Stanford, Calif.: Stanford, Calif. p. 278–292.

- Student, W.S.G. The Probable Error of a Mean. Biometrika 1908, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. The generalisation of Student's problems when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biometrics Bulletin 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the Interpretation of χ 2 from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1922, 85, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. London Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. XV. —The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1918, 52, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Note on Regression and Inheritance in the Case of Two Parents. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; et al. Zero-cell corrections in random-effects meta-analyses. Research Synthesis Methods 2020, 11, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, A.G.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer, in EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Madrid 2025, A. EAU Guidelines Office, the Netherlands., Editor. 2025: Madrid, Spain.

- Alidjanov, J.F.; Naber, K.G.; Pilatz, A.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Validation of the American English Acute Cystitis Symptom Score. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzhabov, A.; Zamuddinov, M.; Alidjanov, J.F.; Pilatz, A.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Naber, K.G. Linguistic and Clinical Validation of the Tajik Acute Cystitis Symptom Score for Diagnosis and Patient-Reported Outcome in Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).