1. Introduction

Sixth cranial nerve palsy is the most common type of ocular motor nerve palsy. Its etiology includes neoplastic, traumatic, infectious, microvascular disease, and giant cell arteritis [

1,

2]

. Some of these causes are fatal and require prompt neurological evaluation and urgent treatment to avoid irreversible complications.

Lyme disease a multisystem infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted to humans thorough the bite of infected ticks or nymphs. The prevalence of this bacterium in ticks in Belgium is estimated at 9.9%. The risk of contracting Lyme disease increases during the period of tick activity typically from May to October [

3]. Although many infections remain localized to the skin, early dissemination may occur.

Early neuroborreliosis usually develops within two to three weeks of infection. In adults, the most frequent neurological manifestation is Bannwarth syndrome which is characterized by lymphocytic meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis and cranial nerve involvement, most often affecting the facial nerve but potentially involving other cranial nerves as well [

4]. We report the case of a 46-year-old man who presented to the ophthalmology emergency department with new onset of binocular horizontal diplopia ultimately diagnosed as Lyme neuroborreliosis.

2. Case Report

A 46-year-old man presented to the ophthalmology emergency department with a five-day history of horizontal binocular diplopia that he described constant and more pronounced when looking to the left. He also reported compressive, holocranial headaches that had been progressively radiating bilaterally to the cervical region for approximately three weeks. His past medical history included Crohn’s disease for which he received infliximab infusions every two months. He denied any recent gastro-intestinal manifestation or current systemic infection. He reported no prior neurologic disorder and no recent travel outside Europe. Ophthalmological examination revealed a corrected visual acuity of 10/10 Parinaud 2 in both eyes, with normal anterior segment and fundus examinations. Orthoptic examination showed 30 diopters of left esotropia with markedly limited abduction in the left eye. A comprehensive neurologic examination revealed no additional motor or sensory deficits. To relieve his symptoms, the patient was temporarily fitted with Fresnel prisms.

Peripapillary retinal nerve fibers layer optical coherence tomography (OCT), ganglion cell complex (inner nuclear layer + ganglion cells layer) OCT and automated visual field examinations were normal, as were the cerebral CT scan and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). General laboratory tests, including complete blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), angiotensin-converting enzyme, syphilis, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) serologies and tuberculosis testing were normal. The only abnormal result was positive serum Borrelia IgG antibodies.

Two weeks after his first visit, during a follow-up appointment, the patient reported new symptoms of incomplete left eyelid closure and a drooping of the left oral commissure on the same side indicating a deficit of the homolateral seventh cranial nerve. He also complained of progressively intensifying headaches that became intolerable, neck pain and diplopia. Ophthalmologic examination was similar to that of the first visit. Further history-taking revealed that the patient had sustained a tick bite four months earlier during a hike in the woods. His general practitioner had documented an erythema migrans rash and prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days, which the patient completed.

Given the new cranial nerve VII involvement and history of tick exposure, further testing was undertaken. The patient underwent laboratory testing and a lumbar puncture. No inflammatory syndrome was detected, but serum antibodies against Borrelia were positive on both enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot tests. The lumbar puncture showed proteinorachy, pleocytosis and the presence of Borrelia IgG in the CSF. Intrathecal IgG secretion index was also positive.

The presence of multineuritis with positive serum and intrathecal Borrelia serologies led to a diagnosis of neuroborreliosis. The patient was treated with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 28 days. By the end of the antibiotic course, the patient was free of symptoms, including facial paralysis. Follow-up orthoptic assessment showed a recovery of left eye abduction, with only a minimal residual esotropia of one prism diopter on left gaze, which was asymptomatic.

3. Discussion

Sixth nerve palsy: causes, diagnostic and management

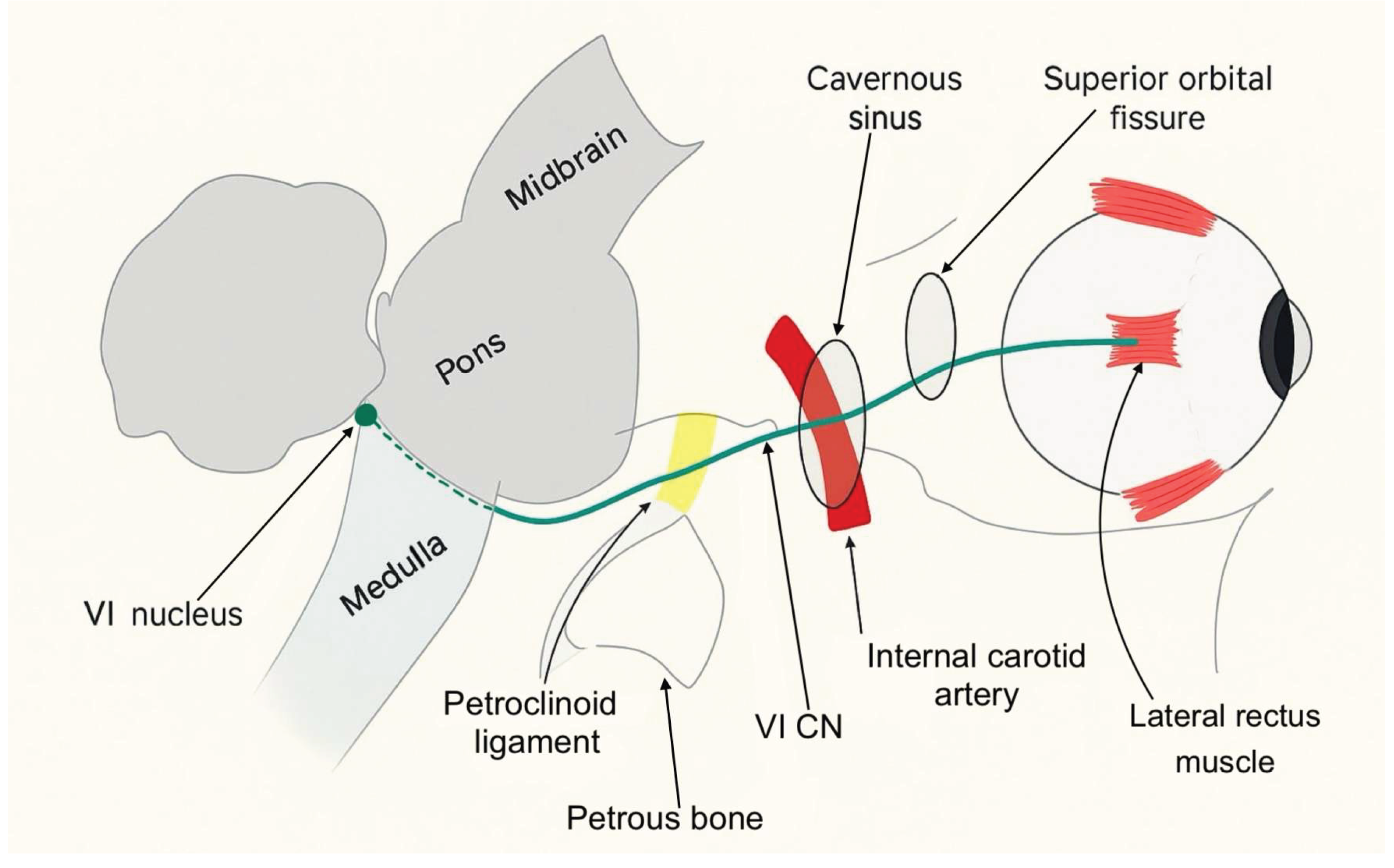

Most sixth nerve palsies are unilateral and acquired. They typically present with new-onset horizontal diplopia and impaired abduction of the affected eye. Immunologic or viral injury to the abducens nerve can occur at any point along its course. As illustrated in Figure 1, the abducens nerve, also known as the sixth cranial nerve, has a long course extending from the sixth nerve nucleus in the dorsal pons to the lateral rectus muscle within the orbit. Its anatomy makes it vulnerable to injury at numerous points. Sixth nerve palsies can be classified into distinct syndromes based on the anatomical location of the nerve involvement: brainstem syndrome, petrous apex syndrome, cavernous sinus syndrome, orbital syndrome, and isolated sixth nerve palsy. Each of these regions has characteristic associated signs that can help localize it.

The brainstem syndrome can involve the fifth, seventh and eighth cranial nerves, as well as the pyramidal tract on the anterior aspect of the pons and the cerebellum behind it. The petrous apex syndrome concerns the course of the sixth cranial nerve under the petro-clinoid ligament. In this area, the ipsilateral fifth, seventh and eighth cranial nerves can be involved. When the injury is located within the cavernous sinus, the sixth nerve palsy is often associated with a dysfunction of the third, fourth and fifth (ophthalmic and maxillary divisions) cranial nerves. Involvement of the internal carotid artery and the carotid sympathetic plexus is also possible. Finally, if the sixth cranial nerve is injured within its orbital course, the optic nerve and the ophthalmic and maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve may be affected. Proptosis is an early sign of the orbital syndrome and is frequently accompanied by conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis [

1,

2]

.

Figure 1.

Course of the abducens nerve.

Figure 1.

Course of the abducens nerve.

Isolated sixth nerve palsy in adults is most commonly caused by microvascular ischemia, often related to systemic pathologies such as diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis or systemic hypertension. However, it may also occur secondary to elevated intracranial pressure. In fact, approximately 19% of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension have been diagnosed with sixth cranial nerve palsy [

5]. Infectious causes such as Lyme disease or syphilis are uncommon and account for only a small proportion of cases [

6]. A retrospective study found that trauma is responsible for about 3% of isolated sixth nerve palsy [

7]

.

It is important to consider other conditions that can mimic sixth nerve palsy, including thyroid eye disease and myasthenia gravis [

1,

2]

. Prompt differentiation of these entities is essential to avoid unnecessary imaging and to recognize more serious underlying disease.

A thorough ophthalmologic examination is mandatory in any patient presenting with acute diplopia or suspected sixth nerve dysfunction. This examination should include the assessment of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, pupillary light reflexes and motility deficits to document the degree of lateral rectus weakness. Examination of the anterior and posterior segments of the eye, including a dilated fundus evaluation, is important to detect papilledema or other retinal and choroidal findings that might signal raised intracranial pressure or a systemic inflammatory disease. A complete cranial nerve and neurologic examination should also be conducted since additional nerve involvement can redirect the diagnostic work-up toward brainstem, petrous apex, cavernous sinus, or orbital apex pathology [

2]

.

The workup should include laboratory tests such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP, syphilis testing, Lyme antibody testing, glucose levels or hemoglobin A1c, syphilis, HIV serologies, tuberculosis and Lyme antibody testing, thyroid function tests, and myasthenia gravis antibodies [

2]

.

Neuroimaging is recommended in patients with an atypical clinical presentation, age under 50 years or persistent symptoms beyond three months to rule out compressive, inflammatory or demyelinating lesions. Brain MRI with gadolinium is preferred, as it can detect small enhancing lesions of individual cranial nerves [

8]

. Computed tomography of the orbits and skull base may also be considered if bone or sinus pathology is suspected. In our case, MRI was not contributory.

As previously discussed, sixth cranial nerve palsy can have multiple etiologies and the underlying cause largely determines the extent of recovery which may be complete or, in some cases, absent. Persistent paresis can result in chronic esotropia and diplopia, causing significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life in affected patients.

To alleviate the patient’s discomfort during the diagnostic work-up, interim measures such as Fresnel prisms may be proposed. Fresnel prisms, thin and flexible plastic lenses affixed to the patient’s glasses, can provide temporary optical compensation for a defined angle of ocular misalignment [

2].The use of prism correction was highly effective in managing the binocular diplopia in our patient.

In the early stages, the use of botulinum toxin can be also useful. Injection of botulinum toxin into the ipsilateral medial rectus (MR) weakens its contractile force, preventing secondary contracture and improving the effectiveness of prismatic correction in cases of marked deviation [

2].

For long-term management, ground-in prisms - prisms permanently incorporated into the spectacle lenses- offer a cosmetically superior alternative to Fresnel prisms, albeit at greater expense. If the palsy does not resolve after 6 to 10 months, a surgical intervention is indicated. Careful preoperative assessment of lateral rectus (LR) function and deviation angle is essential to guide surgical planning. The primary objectives are to expand the binocular diplopia-free field, improve abduction and restore primary-position alignment. Patients with partial LR function typically undergo horizontal muscle surgery, which may include contralateral medial rectus (MR) recession to address significant incomitance, ipsilateral LR resection/plication to improve abduction, and/or ipsilateral MR recession to reduce excessive adduction [

9,

10]. In contrast, complete LR palsy requires a distinct strategy. The preferred initial procedure is vertical rectus muscle transposition (VRT), which repositions vertical rectus forces to substitute for absent LR activity. The most common VRT techniques are the Jensen and Hummelsheim procedures and the modified Nishida procedure [

9,

10]

.

Lyme disease: an overview

There are three stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated. Early localized infection typically occurs days to weeks after the tick bite. It manifests with an expanding erythematous rash called erythema migrans (EM) that appears at the site of the tick bite and is often accompanied by flu-like symptoms. If left untreated, weeks to months later, the infection can spread hematogenously, leading to early disseminated Lyme disease, which can manifest as multiple EM lesions, facial palsy, meningitis, or carditis. Late disseminated disease occurs months to years after an untreated infection and can lead to encephalomyelitis, encephalopathy, chronic arthritis, or chronic atrophying acrodermatitis [

11]. Cranial nerve VII is the most common cranial nerve affected by Lyme disease [

11]. Some authors suggest that inflammatory edema may easily damage the facial nerve due to its long intraosseous course [

12].

Lyme Neuroborreliosis encompasses all the neurologic manifestations caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Early neuroborreliosis manifests during the first two stages of Lyme disease, with Bannwarth syndrome being the most frequent presentation. This syndrome is characterized by the triad of lymphocytic meningitis, cranial nerve damage, and radiculoneuritis. Late neuroborreliosis develops in 5% of untreated patients and can lead to irreversible nerve damage, headache, fatigue, paresthesia, chronic neuropathic pain, and cognitive impairment [

4].

The diagnostic criteria for Lyme neuroborreliosis include a typical clinical picture (cranial nerve deficits, meningitis), a sensitive ELISA test, followed by Western blot testing confirming the presence of abnormal IgM or IgG antibodies in serum, and an inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid syndrome with lymphocytic pleocytosis demonstrating the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier dysfunction, and intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis. The antibody index, which is the ratio of specific antibodies in CSF compared with serum, has a high specificity (97%) but only moderate sensitivity (40%–89%) [

13,

14].

Lyme disease can also produce a wide array of ocular findings. The literature describes follicular conjunctivitis, which may be unilateral or bilateral and occasionally severe enough to cause marked eyelid edema. Other reported presentations include interstitial or ulcerative keratitis, episcleritis, scleritis, orbital myositis, uveitis (anterior, intermediate, or posterior), optic neuritis, and oculomotor palsies affecting the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerves [

15]. These diverse signs underscore the need for ophthalmologists to maintain a high index of suspicion in endemic areas, especially when conventional causes of cranial nerve palsy are not apparent.

In our case, all diagnostic criteria were met, with the patient presenting with early onset neuroborreliosis and typical Bannwarth syndrome. The treatment for patients with acute neurological disease due to

Borrelia burgdorferi infection is based on one of the following regimens for 14 to 21 days: oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for adults), ceftriaxone (2 g IV once a day), cefotaxime (2 g IV every eight hours) [

16]. According to the EFNS (European Federation of Neurological Societies), the outcomes with the use of oral doxycycline (200 mg daily) and IV ceftriaxone (2 g daily) for 14 days was the same [

4].

The treatment depends on disease severity, patient tolerance, comorbidities and local resistance patterns. Our patient was treated with doxycycline for 28 days and completely recovered.

In contrast to the more typical involvement of the facial nerve in Lyme disease, our patient presented initially with an isolated sixth nerve palsy. Such an initial presentation is uncommon and highlights both the broad spectrum of manifestations of neuroborreliosis and the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnostic when evaluating cranial nerve palsies. For ophthalmologists and neurologists practicing in endemic regions, maintaining awareness of Lyme disease as a potential cause is critical. Early recognition and appropriate antibiotic therapy not only resolve acute symptoms but also prevent chronic complications.

5. Conclusions

The severity of etiologies for sixth cranial nerve paralysis varies greatly, ranging from relatively benign microvascular ischemia to life-threatening intracranial masses or infectious causes. When confronted with an acquired sixth nerve palsy, ophthalmologists must perform a thorough and detailed medical history and comprehensive examination, including systemic review and careful cranial nerve and neurologic assessment. Neuroimaging is mandatory in patients under 50 years old, and further diagnostic workup including serologic testing for infectious and inflammatory disorders should be considered. When isolated or multiple cranial neuropathies, especially with headaches or meningitis symptoms are present, Lyme disease must be considered as a differential diagnosis. This case emphasizes that a meticulous history-taking, including potential tick exposure, is essential for guiding appropriate investigations and avoiding unnecessary diagnostic delay. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment are crucial to prevent disease progression and neurologic sequelae including chronic complications. Our patient’s complete recovery following a full course of doxycycline therapy highlights the importance of timely recognition and treatment of neuroborreliosis. Clinicians should remain vigilant and avoid dismissing positive Lyme serologies as false positives without considering the clinical context and regional epidemiology.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFS |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| ESR |

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| EM |

Erythema migrans |

| CN |

Cranial nerve |

| LR |

Lateral Rectus |

| MR |

Medial Rectus |

| VRT |

Vertical Rectus muscle Transposition |

| EFNS |

European Federation of Neurological Societies |

References

- Thomas C, Dawood S. Cranial nerve VI palsy (Abducens nerve). Disease-a-Month. mai 2021;67[5]:101133.

- Azarmina M, Azarmina H. The Six Syndromes of the Sixth Cranial Nerve. JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH. 8[2].

- Philippe C, Geebelen L, Hermy MRG, Dufrasne FE, Tersago K, Pellegrino A, et al. The prevalence of pathogens in ticks collected from humans in Belgium, 2021, versus 2017. Parasites Vectors. 5 sept 2024;17[1]:380.

- Mygland Å, Ljøstad U, Fingerle V, Rupprecht T, Schmutzhard E, Steiner I. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of European Lyme neuroborreliosis. Euro J of Neurology. janv 2010;17[1]:8.

- Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. févr 1991;114 ( Pt 1A):155-80.

- Jung EH, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Cho BJ. The incidence and etiology of sixth cranial nerve palsy in Koreans: A 10-year nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 5 déc 2019;9[1]:18419.

- Shrader EC, Schlezinger NS. Neuro-Ophthalmologic Evaluation of Abducens Nerve Paralysis. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1 janv 1960;63[1]:84-91.

- Elder C, Hainline C, Galetta SL, Balcer LJ, Rucker JC. Isolated Abducens Nerve Palsy: Update on Evaluation and Diagnosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. août 2016;16[8]:69.

- Akbari MR, Masoomian B, Mirmohammadsadeghi A, Sadeghi M. A Review of Transposition Techniques for Treatment of Complete Abducens Nerve Palsy. Journal of Current Ophthalmology. juill 2021;33[3]:236-46.

- Hakimeh C, Shahraki K, Courtois L, W. Suh D. Surgical management of chronic sixth cranial nerve palsy: case report and literature review. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 1 juill 2024;13[1]:55-62.

- Sriram A, Lessen S, Hsu K, Zhang C. Lyme Neuroborreliosis Presenting as Multiple Cranial Neuropathies. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 4 mars 2022;46[2]:131-5.

- Eiffert H, Karsten A, Schlott T, Ohlenbusch A, Laskawi R, Hoppert M, et al. Acute Peripheral Facial Palsy in Lyme Disease - A Distal Neuritis at the Infection Site. Neuropediatrics. août 2004;35[5]:267-73.

- Rauer S, Kastenbauer S, Hofmann H, Fingerle V, Huppertz HI, Hunfeld KP, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment in neurology – Lyme neuroborreliosis. GMS German Medical Science; 18:Doc03 [Internet]. 27 févr 2020 [cité 15 sept 2025]; Disponible sur: https://www.egms.de/en/journals/gms/2020-18/000279.

- Chaturvedi A, Baker K, Jeanmonod D, Jeanmonod R. Lyme Disease Presenting with Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits: Report of a Case. Case Reports in Emergency Medicine. 2016;2016:1-3.

- Lesser, RL. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. The American Journal of Medicine. avr 1995;98[4]:60S-62S.

- Hu, L.; Shapiro, E. D.; Steere, A. C. (Eds.) Treatment of Lyme disease. U: In, 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).