Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection Criteria

2.2. Definition of Focal Infection

- (A)

- (B)

- Peaceful, delicate rose (not red) tonsils - a very important criterion. AND

- Pus can be squeezed from the tonsils.

- AND/OR Pus can be seen coming from deep within. Small white pus clumps, sometimes the size of a pinhead or smaller, or even sizable "tonsil stones" may be visible.

- AND/OR The tonsils are pitted, deeply fissured.

- AND/OR The tonsils are spectacularly asymmetrical.

- AND/OR Some parts or the entire tonsils are rounded, swollen, „inflated”.

2.3. Clinical Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Chronic Lyme Disease as a Hot Topic

4.2. Symptoms of "Chronic Lyme Disease" According to Lyme Foundations' Guidelines

4.4. Chronic Tonsillitis as a Focal Infection

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steere, A.C.; Malawista, S.E.; Snydman, D.R.; Shope, R.E.; Andiman, W.A.; Ross, M.R.; Steele, F.M. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977, 20, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachner, A.R. Borrelia burgdorferi in the nervous system: the new "great imitator". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988, 539, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakos, A. Lyme disease and chronic Lyme disease. Orvostovábbképző Szemle 2017, 24, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lakos, A. Chronic Lyme disease=post-Lyme syndrome=focal infections? Integráló infekciókontroll 2024, 3, 37-50. [in Hungarian].

- Lantos, P.M. Chronic Lyme disease: the controversies and the science. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011, 9, 787–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakos, A.; Igari, E. Advancement in Borrelia burgdorferi antibody testing: Comparative immunoblot assay (COMPASS). In: Lyme disease, Ed: Karami A. InTech, Rijeka 2012, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hornok, S.; Takács, N.; Nagy, Gy.; Lakos, A. Retrospective molecular analyses of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from patients admitted to the medical Centre for Tick-Borne Diseases in Central Europe, Hungary (1999-2021) in relation to clinical symptoms. Parasit. Vectors 2025, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, K.E.; Nwokeabia, B.C.; Hassan, R.; Dunphy, T.; Osondu, M.; Wonders, C.; Khaja, M. What Makes It Tick: Exploring the Mechanisms of Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. Cureus. 2024, 16, e64987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogne, A.G.; Müller, E.G.; Udnaes, E.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Raudeberg, R.; Connelly, J.P.; Revheim, M.E.; Hassel, B.; Dahlberg, D. β-Amyloid may accumulate in the human brain after focal bacterial infection: An 18 F-flutemetamol positron emission tomography study. Eur J Neurol. 2021, 28, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, S.; Green, C.; Szantyr, B.; Phillips, S.; Liegner, K.; Burrascano, J.J. Jr.; Bransfield, R.; Maloney, E.L. Chronic Lyme Disease: An Evidence-Based Definition by the ILADS Working Group. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, P.H.; Lenormand, C.; Jaulhac, B.; Talagrand-Reboul, E. Human Co-Infections between Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. and Other Ixodes-Borne Microorganisms: A Systematic Review. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos P.M.; Wormser, G.P. Chronic coinfections in patients diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2014; 127, 1105-10.

- Lymedisease.org: Lyme disease checklist. [https://www.lymedisease.org/lyme-disease-symptom-checklist/ accessed on March 2, 2024].

- Lantos, P.M.; Rumbaugh, J.; Bockenstedt, L.K.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.E.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Baldwin, K.; Bannuru, R.R.; Belani, K.K.; Bowie, W.R.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantos, P.M. Chronic Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015, 29, 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berende, A.; Ter Hofstede, H.J.M.; Vos, F.J.; Vogelaar, M.L. erende, A.; Ter Hofstede, H.J.M.; Vos, F.J.; Vogelaar, M.L. Effect of prolonged antibiotic treatment on cognition in patients with Lyme borreliosis Neurology. 2019, 92, e1447-e1455. [CrossRef]

- Klempner, M.S.; Baker, P.J.; Shapiro, E.D.; Marques, A.; Dattwyler, R.J.; Halperin, J.J.; Wormser, G.P. Treatment trials for post-Lyme disease symptoms revisited. Am J Med. 2013, 126, 665–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

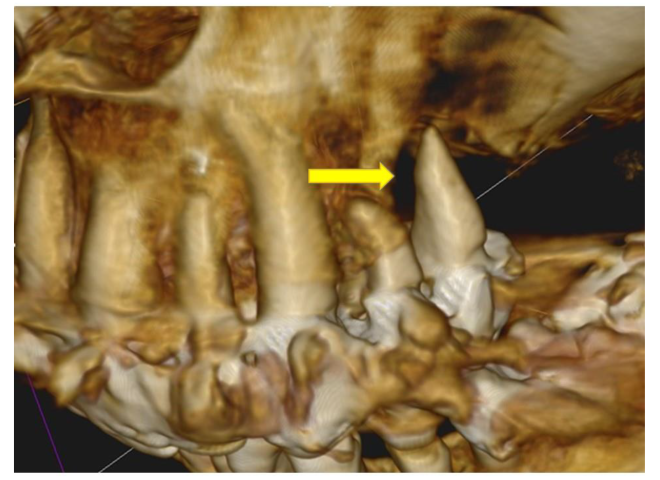

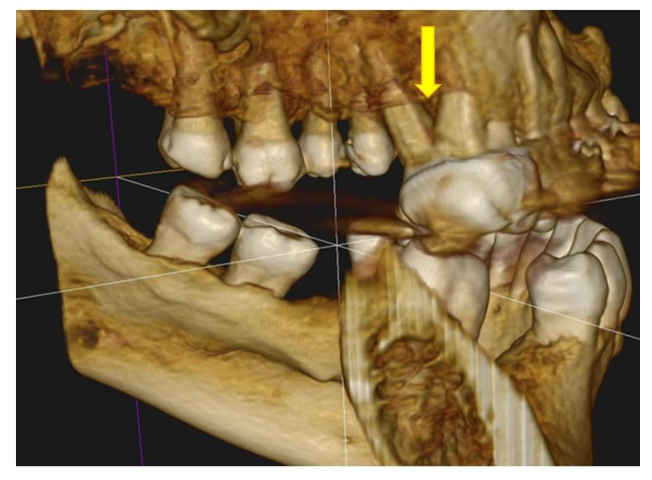

- Lohiya, D.V.; Mehendale, A.M.; Lohiya, D.V.; Lahoti, H.S.; Agrawal, V.N. Effects of periodontitis on major organ systems. Cureus 2023, 15, e46299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, E.B.; Breault, L.G.; Cuenin, M.F. Periodontal disease and its association with systemic disease. Mil Med. 2001, 166, 85–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.R.; Kupp, L.I.; Sheridan, P.J.; Sánchez, D.R. Maternal chronic infection as a risk factor in preterm low birth weight infants: the link with periodontal infection. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2004, 6, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Soskolne, W.A.; Klinger, A. The relationship between periodontal diseases and diabetes: an overview. Ann Periodontol. 2001, 6, 91–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsopoulos, N.M.; Madianos, P.N. Low-grade inflammation in chronic infectious diseases: paradigm of periodontal infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006, 1088, 251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannapieco, F.A.; Dasanayake, A.P.; Chhun, N. "Does periodontal therapy reduce the risk for systemic diseases? " Dent Clin North Am. 2010, 54, 163–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng-Kai Ma, K.; Lai, J-N. ; Veeravalli, J.J.; Chiu L.T.; Van Dyke T.E.; Wei J.C. Fibromyalgia and periodontitis: Bidirectional associations in population-based 15-year retrospective cohorts. J Periodontol. 2022, 93, 877–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, J.; Gera, I.; Fejérdy, P.; Soós, B.; Madléna, M.; Hermann, P. Oral health assessment of Hungarian adult population based on epidemiologic examination. (in Hungarian) Fogorvosi Szemle 2011, 104, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, A.; Fagö-Olsen, H.; Sørensen, Ch.; Kilian, M. Molecular mapping to species level of the tonsillar crypt microbiota associated with health and recurrent tonsillitis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e56418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryukov, A.I.; Krechina, E.K.; A S Tovmasyan, A.S.; Kishinevskiy, A.E.; Danilyuk, L.I.; Filina, E.V. Chronic tonsillitis and periodontal diseases. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2023, 88, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoodley, P.; Debeer, D.; Longwell, M.; Nistico, L.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Wenig, B.; Krespi, Y.P. Tonsillolith: not just a stone but a living biofilm. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009, 141, 316–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, M.; Strużycka, I.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Significance of biofilms in dentistry. Przegl Epidemiol. 2015, 69, 739–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).