1. Introduction

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a severe, frequent and debilitating disease. There is an overlap with post-acute infection syndromes (PAIS) which demonstrate similar symptom profiles irrespective of the infectious agent [

1,

2,

3]. The prevalence of ME/CFS and post-acute infection syndrome (PAIS) have increased significantly because of SARS-CoV-2 infections. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of developing PAIS was at least 6.5%, and likely closer to 15% among those infected [

4]. PAIS after SARS-CoV-2 infections contributes much to substantial cumulative burden of health loss in populations [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6]. ME/CFS presents with a plethora of symptoms which include severe fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, exercise intolerance with post-exertional malaise (PEM), exaggerated by any stresses, physical, emotional or cognitive. Chronic whole body pain, joints and muscle aching, and dyspnea are reported [

3,

7,

8]. Orthostatic intolerance, tachycardia and palpitations are prevalent. Inability to stand upright or even to sit for a long time is found in more severely ill ME/CFS patients who are often housebound or bedridden [

9,

10]. Laboratory findings include inflammation, formation of reactive oxidative species, proinflammatory cytokines, and activation of the inflammasome, as well as disturbances in T cell function and secretory immune system and B cell function, followed by complement activation and immune thrombosis and decreased tissue blood flow [

11,

12,

13]. Neurocognitive symptoms include inabilities to concentrate, to read or to memorize, and a particular cognitive cloudiness which is described as “brain fog”. Hypersensitivities against light, noises and smells are reported. Sleep disorders are common as well as gastrointestinal symptoms [

3,

7,

8]. Despite these partially debilitating symptoms and the rising prevalence, medicine has failed to define a pathophysiological picture. Clinical neurological investigations did not find disturbances in nerve conduction velocity; neuroimaging does not reveal spinal or cerebral pathologies.

This review focuses on muscle weakness as an important contribution to the burden of disease. The inability to perform even low intensity endurance exercises, increasing weakness after few muscle contractions and the loss of muscle strength for single contractions characterize myasthenia in ME/CFS. Skeletal muscle incapacity and myasthenia are important signs of disease severity [

7,

14,

15]. Accordingly, hand grip strength correlates with severity of fatigue, disability and symptoms [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Muscle tremor or fasciculations have only been reported recently [

20]. In the Yale LISTEN trial from 423 subjects after COVID-19, 37% reported retrospectively “internal tremors, or buzzing/vibration”. Compared to the others, participants with internal tremors reported worse health and had higher rates of new-onset mast cell disorders (11% vs. 2.6%) and neurologic conditions (22% vs. 8.3%) [

21].

As no neurological causes have been found, a muscular pathomechanism explaining loss of force, fasciculations (or tremor), cramps and muscular pain should instead be assumed. In this paper, the focus is on the potential cause of the disturbed muscle function and muscle symptomatology. In many other diseases decisive pathophysiological recognitions have been gained from severe cases and have strongly contributed to the understanding of the pathophysiology of the milder cases. Recognitions concerning pathophysiology in ME/CFS, however, mainly come from patients with less severe disease because bedridden patients, unable to leave their houses, have not been accessible to medical research.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), which provides objective metabolic data in patients with mild to moderate symptomatology demonstrated reduced maximal oxygen consumption [

22,

23,

24], an early appearance of anaerobic metabolism during exercise and deregulated energy metabolism [

25,

26].

In more than 50% of post-COVID and ME/CFS patients, mitochondria in skeletal muscles show damage to their internal structures (cristae) and shape, including lysis. In some cases, neighboring sarcomeres also show severe damage [

23]. Local and systemic metabolic disturbances, decreased oxidative phosphorylation, severe exercise-induced myopathy and tissue infiltration of amyloid-containing deposits are found [

22,

23]. However, these studies only involved patients who were able to exercise, which means they suffered from mild to moderate disease severity. Muscular force measured as hand grip strength is known to be decreased in ME/CFS and PAIS and to even correlate with symptoms in patients still able to visit the medical unit [

16,

18,

19].

2. The Potential Causes of Myasthenia in ME/CFS

Four possible causes must be considered in the discussion on the loss of muscular force:

- 1)

Lack of energy due to mitochondrial dysfunction

- 2)

Atrophy due to inactivity in the intention to avoid PEM and due to immobilization (deconditioning)

- 3)

Skeletal muscle damage

- 4)

Electrophysiological causes leading to insufficient excitation and recruitment of muscle fibers upon neuromuscular activation

Ad 1) Skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction can explain loss of endurance and of force-endurance. However, a strong loss of force even with the first muscular action after a sufficiently long rest is not explained by a lack of energy due to mitochondrial dysfunction. This is because certain skeletal muscles are physiologically of the glycolytic type and these are even the most vigorous muscles (of the fast twitch 2b fiber type). We have learned from SARS-CoV-2 infections that, even in asymptomatic athletes, VO2max is decreased after 3 months and much more so in those with symptoms [

27]. Viral proteins likely alter the mitochondrial epigenome, by histone modifications or by modulating metabolite substrates, potentially silencing OXPHOS gene expression [

28].

Ad 2) Skeletal muscle atrophy and deconditioning as a cause for muscle weakness have been excluded by a careful recent investigation comparing healthy individuals after 6-weeks bedrest with ME/CFS patients [

29]. Patients with long COVID and ME/CFS did not show muscle atrophy but had less capillaries and more glycolytic fibers [

22,

29,

30]. In contrast to healthy subjects after 6-weeks of bed rest, skeletal muscle in ME/CFS patients does not really rest as patients suffer from cramps and fasciculations. A key assumption in our concept is that calcium in skeletal muscle is too high and that calcium overload causes damage [

31]. Calcium pathways are indeed discussed to constitute the hypertrophic signal [

32]. It may oppose the tendency for atrophy by inactivity and thus prevent atrophy even in bedridden ME/CFS patients.

Ad 3) Although skeletal muscle damage has been shown in a recent study and might contribute minorly to the muscle force reduction, this damage is most likely not big enough to cause a severe loss of force [

22]. Skeletal muscle biopsies from severely ill patients would be needed to clarify this question.

Ad 4) In the following we provide arguments that the main and common cause for both loss of force and fasciculations could be a disturbed electrophysiology of skeletal muscle. We try to explain how muscular symptoms including loss of force and endurance, fasciculations and pain are causally related.

3. The Potential Role of the Na+/K+-ATPase in Physiology and Pathophysiology of ME/CFS

A key assumption in our concept of a unifying disease hypothesis for ME/CFS published in previous papers is that the Na

+/K

+-ATPase is dysfunctional [

31,

33]. The causes are insufficient hormonal stimulation, active inhibition by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lack of ATP due to mitochondrial dysfunction. Ouabain, an inhibitor of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase, impressively demonstrates that (strong) inhibition of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase leads to a (total) loss of muscle force upon electrical stimulation in isolated skeletal muscle and depolarization of the resting membrane potential [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Not only is sodium efflux decreased because of an insufficient Na

+/K

+-ATPase- activity but sodium influx is also strongly increased by complex perfusion disturbances in PAIS raising the activity of the proton-sodium-exchanger subtype 1 (NHE1) which is explained at length in a previous publication [

33]. This increases the workload of the already impaired Na

+/K

+-ATPase. Intracellular sodium loading as shown in ME/CFS patients in skeletal muscle is the consequence [

38]. Sodium overload, in turn, causes calcium overload and associated calcium-induced damage at a high intracellular sodium concentration. The sodium-calcium-exchanger (NCX) changes its transport direction to import calcium instead of exporting it at high intracellular sodium. The sodium concentration at which this occurs is referred to as the reverse mode threshold of the NCX. We see the reverse mode threshold of the NCX as the biological base for the clinical PEM-threshold [

31]. These pathomechanisms can also fully explain the observed skeletal muscle damage after exercise [

22].

4. The Physiological Role of the Na+/K+-ATPase in Muscle Electrophysiology and Metabolism

Na

+/K

+-ATPase generates the electro-chemical ion gradients between intracellular and extracellular space by exporting 3 Na

+ ions against the cellular import of 2 K

+ ions [

39,

40]. These gradients are responsible for the physiological resting membrane potential as well as for the driving forces for excitation and propagation of the action potential. With diminished activity of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase the resting membrane potential becomes more positive and gets closer to the firing threshold (depolarized). The consequence is hyperexcitability so that otherwise subthreshold stimuli can cause excitations which are less efficacious leading to reduced force development. Prolonged depolarization of the sarcolemma would inactivate voltage-gated Na

+ channels and impair neuromuscular transmission. Na

+/K

+-ATPase accelerates repolarization and restores excitability and contractility of skeletal muscle. Furthermore, by limiting K

+ loss from contracting skeletal muscle, Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity also helps to prevent or at least blunts exercise-induced extracellular interstitial hyperkalemia which would have depolarizing effects increasing hyperexcitability, and it maintains the high intracellular K

+ concentration that together with chloride conductivity forms the resting membrane potential in skeletal muscle.

During exercise Na

+/K

+-ATPase is hormonally stimulated by protein kinase A (PKA) via cAMP activated by ß2-adrenergic receptors and by calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP) [

40,

41,

42]. At rest, stimulation is by low concentrations of acetylcholine via the nicotinergic receptor and by insulin. Insulin stimulates Na

+/K

+-ATPase via protein-kinase C directly and by its translocation from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane [

40]. A third indirect mechanism related to its energy supply will be explained below.

Na

+/K

+-ATPase is not only responsible for creating membrane excitability, but it is also involved in energetic processes. By maintaining low intracellular Na

+ concentrations, Na

+/K

+-ATPase promotes Na

+-coupled transport and uptake of substrates, which play key roles in energy metabolism of skeletal muscle including carnitine, inorganic phosphate, amino acids like glutamine and alanine [

43,

44]. Furthermore, it provides the sodium gradient for proton export via the sodium-proton-exchanger. Pyruvate kinase-activity is dependent on the physiologically intracellular (high) potassium concentration [

45]. Proper Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity keeps intracellular potassium high and thus prevents the fall in pyruvate kinase-activity which is dependent on K

+ thus preserving energy supply via glycolysis even at normal oxygen pressure (aerobic glucose utilization) for its own energy supply. Hence, insufficient Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity may also have negative effects on skeletal muscle metabolism, and not only impair electrophysiology.

5. Potential Disturbances of Na+/K+-ATPase in ME/CFS

Autoantibodies against ß2AdR and the high tendency for desensitization of this receptor by the high sympathetic tone found in ME/CFS, for which orthostatic stress may be the most important cause, may cause dysfunction of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase [

46,

47]. CGRP is released from small nerve fibers but small fiber neuropathy which is frequently reported in ME/CFS [

24,

48,

49], may diminish CGRP release and availability. Moreover, TRPM3-dysfunction is present in ME/CFS in leucocytes [

50,

51,

52]. TRPM3 is not only present in leukocytes but also expressed and involved in the release of neuropeptides from sensory nerves so that its dysfunction may reduce CGRP release even before overt small nerve fiber degeneration occurs [

53,

54,

55]. In fully developed ME/CFS, mitochondrial dysfunction develops so that the high energy need of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase may limit its activity [

33]. ROS which is produced via mitochondrial dysfunction even inhibits the Na

+/K

+-ATPase by stimulation of glutathionylation [

40,

41,

56].

Insulin resistance of skeletal muscle, probably of mild degree, has been reported in ME/CFS, [

26,

57,

58,

59,

60]. As insulin stimulates Na

+/K

+-ATPase at rest the ionic situation in skeletal muscle in patients with insulin resistance may not recover sufficiently from previous muscle work for the next activity and patients may already start muscle activity under unfavorable intracellular ionic conditions that lead to an early rise in intracellular sodium and calcium explaining a low PEM threshold in our concept [

40,

41,

42].

6. High Workload and Energy Consumption of Na+/K+-ATPase by Sarcolemmal Depolarization and Fasciculations

For reasons which will be explained below, central muscle tone is probably also increased to favor spontaneous uncoordinated excitations. Since with sarcolemmal depolarization the resting membrane is closer to the firing threshold skeletal muscle is sensitized to central rises in muscle tone and centrally induced excitations. Uncontrolled excitations caused in this way become manifest as muscle fasciculations and cramps and clearly indicate hyperexcitability. It cannot be excluded that there are frequent unnoticed excitations of single muscle fibers. Alterations in EMG-activity have indeed been reported in ME/CFS and Long COVID in less severe cases [

56,

61]. Although such M-wave alterations are rather unspecific and therefore do not reveal a particular cause, M-wave alterations have been previously attributed to a dysfunctional Na

+/K

+-ATPase inhibited by ROS [

56,

62].

Excitations cause sodium influx during depolarization and potassium efflux for repolarization strongly raising the workload of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase the activity of which is already insufficient to restore the physiological action potential. Thus, workload for the Na

+/K

+-ATPase also increases ATP consumption. 5-10% of oxygen consumption in skeletal muscle at rest is estimated to be coupled to the Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity [

40]. In case of frequent excitations, the workload and energy consumption of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase may strongly rise, even at rest. Muscle contractions are the strongest stimulus for Na

+/K

+-ATPase activation. In healthy muscles, direct stimulation of isolated skeletal muscle rapidly increases Na

+ efflux 20-fold [

42]. It is self-explaining that an impaired Na

+/K

+-ATPase function which we strongly assume for ME/CFS cannot raise its activity by a factor of 20 during exercise explaining electrophysiological loss of force, exercise intolerance and further pathomechanisms. The latter includes intracellular sodium loading leading to subsequent calcium overload by the reverse mode of the NCX. Additionally, the reverse mode of the NCX is favored by a more positive membrane potential [

63].

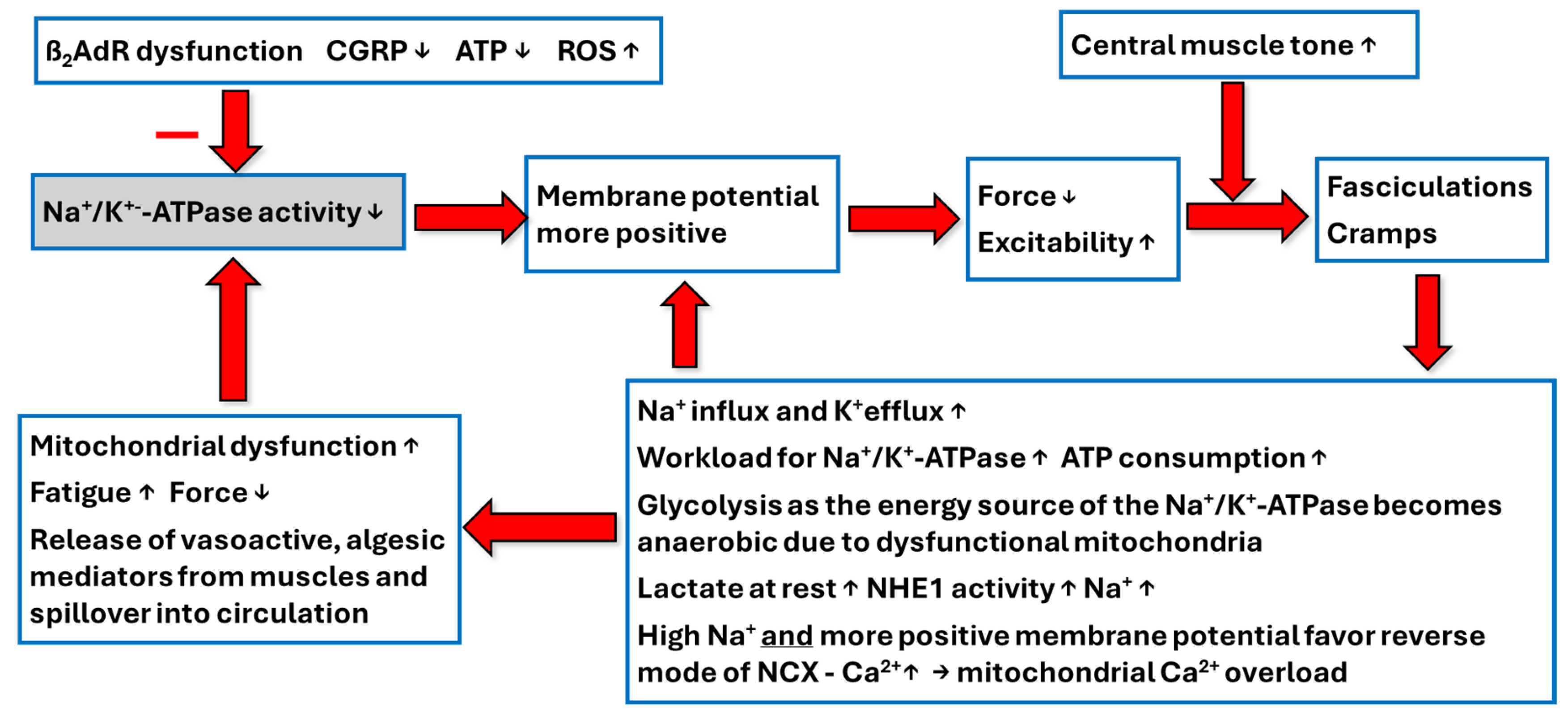

Figure 1 shows the presumed sequence of skeletal pathomechanisms causing dysfunction of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase and its consequences for skeletal muscle pathophysiology in ME/CFS.

7. Energy Supply of the Na+/K+-ATPase and Its Disturbances

Energy supply of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase in skeletal muscle strongly depends on glycolysis [

64]. In aerobic muscle fibers, in contrast to glycolytic muscle fibers, it is very likely that the pyruvate generated by glycolysis for the energy supply of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase is used up in the citrate cycle after decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA by the nearby mitochondria, the subsarcolemmal mitochondria, for the generation of the contractile force and work. In ME/CFS, however, these subsarcolemmal mitochondria show signs of damage and therefore it is likely that glucose metabolism becomes anaerobic to produce more lactate even in the aerobic muscle fibers. Lactate production raises proton concentrations that are mainly extruded by the sodium-proton-exchanger NHE1 further raising intracellular sodium and the workload for the impaired Na

+/K

+-ATPase and enhancing the probability of calcium overload. The depolarized state causes frequent inadequate excitations with sodium influx and potassium efflux for repolarization but the impaired Na

+/K

+-ATPase can no longer restore a stable resting membrane potential that would put an end to the permanent excitations. The skeletal muscle is thus caught in the “depolarization trap”. Therefore, sarcolemmal depolarization generates further depolarization. This raises the workload and energy consumption of Na

+/K

+-ATPase, but the energy supply is limited due to ineffective glycolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Physiologically, excitation and skeletal muscle work (i.e. contraction) are coupled. Therefore, the energetic processes for electrophysiological activity and physical work should also be physiologically coupled. Excitations due to a depolarized state of the sarcolemma and enhanced excitability as assumed here leading to a high workload of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase already at rest dissociates the (high) electrophysiological energetic demand from the demand for physical work for contraction (no demand at rest). Pyruvate would then not be utilized by the citrate cycle and, therefore, lactate would be generated because pyruvate is in equilibrium with lactate. This may explain why a fraction of patients shows elevated lactate levels at rest [

65]. This would impair glycolysis and the energy supply of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase and thereby weaken its activity. This does not necessarily mean that there is a positive correlation between lactate rise at rest and skeletal muscle depolarization and muscular symptoms. In resting conditions, enhanced anaerobic glycolysis could still be effective to provide enough energy for the enhanced need of the Na

+/K

+-ATPase via anaerobic glycolysis to mitigate or prevent depolarization. However, insulin resistance may be present to reduce glucose uptake in skeletal muscle as referenced above and to even impair

anaerobic glycolysis as the energy source for the Na

+/K

+-ATPase and thereby its function favoring depolarization and symptoms [

26,

40,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Insulin resistance may result in lower cellular glucose and pyruvate levels which could explain why lactate levels may remain (paradoxically) low, and secondly, when complex I dysfunction is present, why the import of pyruvate into the respiratory chain as acetyl-CoA is further diminished.

Altogether, insulin is important for the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase via several mechanisms, by providing glucose for its energy supply, by stimulation of its activity via protein kinase C and via its translocation from the cytoplasm into the cell membrane as explained above.

During exercise Na+/K+-ATPase-activity increases although probably less than in healthy controls to contribute to exercise intolerance but the limiting factor for utilizing pyruvate arising from the glycolytic pathway for the energy supply of the Na+/K+-ATPase in aerobic muscles is the low oxidative capacity due to skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction. This can explain lactate rise during exercise. Thus, the rises in lactate at rest and exercise may have different causes in ME/CFS patients.

8. Central Muscle Tone and Depolarized Sarcolemma Interact to Cause Inappropriate Excitations

Above we have mentioned that the central muscle tone is raised. Hypervigilance explaining the severe sleep disturbance and high sympathetic tone are hallmarks of ME/CFS [

66,

67]. Three potential causes for an elevated muscle tone that favor spontaneous skeletal muscle excitations of the depolarized muscle membrane may be considered based on new recognitions and findings. TRPM3-dysfunction may be present in many ME/CFS patients. As explained in a previous paper TRPM3 seems to be involved in the GABA-system and its dysfunction could lower release of GABA and thus raise muscle tone [

55,

68,

69]. New autoantibodies have been reported against the alpha2C-adrenergic receptor (alpha2C-R) and serine/arginine repetitive matrix protein 3 (SRRM3). The latter is also related to the GABA system [

70,

71]. Remarkably, a single nucleotide variant in SRRM3 was found to be associated with ME/CFS strengthening the role of this protein and GABA in ME/CFS-pathophysiology [

72].

The alpha2-R could be involved in ME/CFS as already suspected in a previous paper, simply based on its physiological functions and its tendency for desensitization by catecholamines [

73,

74]. Its dysfunction could explain some symptoms of ME/CFS. Recent findings even show autoantibodies against this important receptor further strengthening the previous assumption that this receptor could be of relevance and be dysfunctional in ME/CFS [

70]. As a postsynaptic receptor the alpha2C-R is present on veins in a vasoconstrictor function [

75]. If inhibited by autoantibodies this would cause orthostatic dysfunction by insufficient venous contraction reducing cardiac preload which would raise sympathetic tone for compensation (orthostatic stress). Alpha2C-R also is a presynaptic receptor on sympathetic nerve endings, acting as an autoreceptor to limit and modulate catecholamine release [

76]. Its dysfunction would cause excessive norepinephrine release and potentially vasoconstriction during sympathetic activation. Norepinephrine released excessively by the synergistic effects of the two mechanisms explained above would have overshooting vasoconstrictor effects since the vasodilatory effect of the intact endothelium that physiologically opposes vasoconstriction is also dysfunctional [

77]. Thus, vasospasms in the periphery (Raynaud symptoms) and orthostatic cerebral vasoconstriction could be explained satisfactorily [

78]. In the brain alpha2C-R is expressed in activating noradrenergic brain regions like the Locus Coeruleus [

75,

79]. Pharmacological agonists at this presynaptic alpha2-adrenergic receptor cause sedation, muscle relaxation and a mild analgesic effect. This enables us to understand the (opposite) effects which blocking autoantibodies could instigate by causing alpha2-R dysfunction. [

80]. Its dysfunction might raise pain perception, muscle tone, vigilance and arousal all of which may be involved in the severe sleep disturbances and sympathetic hyperactivity typically found in ME/CFS [

66,

67,

81].

Not fully understood is the role of the histamine system in ME/CFS. Recent findings reveal small mast cell population in skeletal muscle which are likely responsible for histamine secretion during exercise and for targeting myeloid and vascular cells rather than myofibers in a paracrine manner [

82]. High mast cell activation is more frequent with muscle dysfunction and tremor [

21].

Skeletal muscle depolarization in the severely ill is superimposed on mitochondrial dysfunction: A step model to explain the situation of the severely ill ME/CFS patient

Altogether, the muscles of the severely ill ME/CFS patient may be caught in a state of depolarization and mitochondrial damage even at rest and aggravation is induced by minimal efforts. Energy depleted muscles compensatorily release vasoactive mediators like bradykinin, prostaglandins, prostacyclin and adenosine to raise local blood flow to remove the energetic deficit [

83] and also histamine [

82]. When excessively produced these otherwise very labile mediators can reach every organ (spillover into systemic circulation) and cause symptoms by their vasoactive, inflammatory, vascular leakage-inducing, algesic, hyperalgesic and spasmogenic actions [

83]. In skeletal muscle itself these algesic mediators can cause muscular pain. In the kidney, mediators like bradykinin and prostacyclin cause renal hyperexcretion of sodium and water by raising renal blood flow and by inhibiting distal tubular sodium reabsorption, effects that prevent a rise in renin to correct for the resulting hypovolemia (explaining the renin paradox). This renal mechanism causing hypovolemia together with enhanced vascular leakage could play a strong role in orthostatic dysfunction and orthostatic stress [

83].

Our unifying hypothesis on the causes of the symptoms and pathophysiology of ME/CFS can explain the situation of the severely ill patient without making new assumptions. Mitochondrial damage and skeletal muscle depolarization reinforce each other and have the same cause, a dysfunction of ion transport, mainly by a dysfunction of the Na+/K+-ATPase although favored by a number of different pathomechanisms including increased sodium influx into skeletal muscle, central pathomechanisms, risk factors and triggers. It is the stringent application of the current concept that provides a single pathomechanism to explain loss of force, fatigue and fasciculations of skeletal muscle.

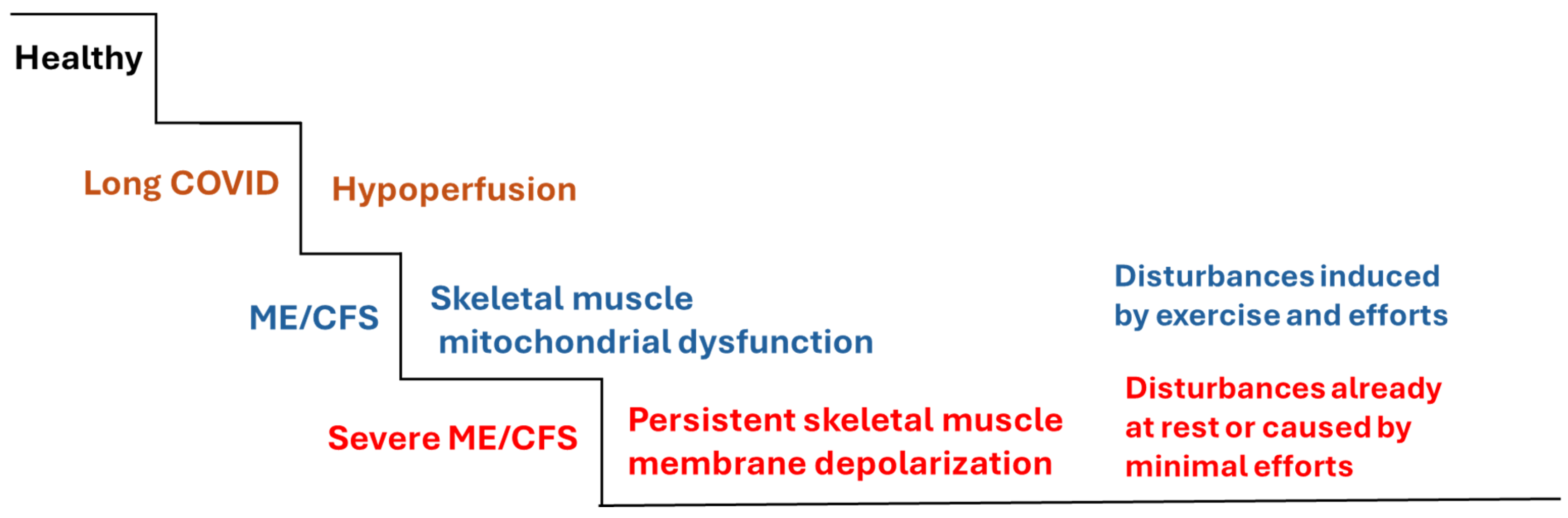

Figure 2 shows a step model of ME/CFS arising from Long COVID. In the Long COVID stage hypoperfusion is present, mainly as a cause of microvascular dysfunction. From these perfusion disturbances in the presence of risk factors ME/CFS develops via skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction. PEM as an aggravation of the complaints occurs by exercise and efforts. The third stage is the situation of the severely ill patient with persisting membrane depolarization that develops because of insufficient Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity and mitochondrial dysfunction. The disturbances are persistent or induced by minimal efforts.

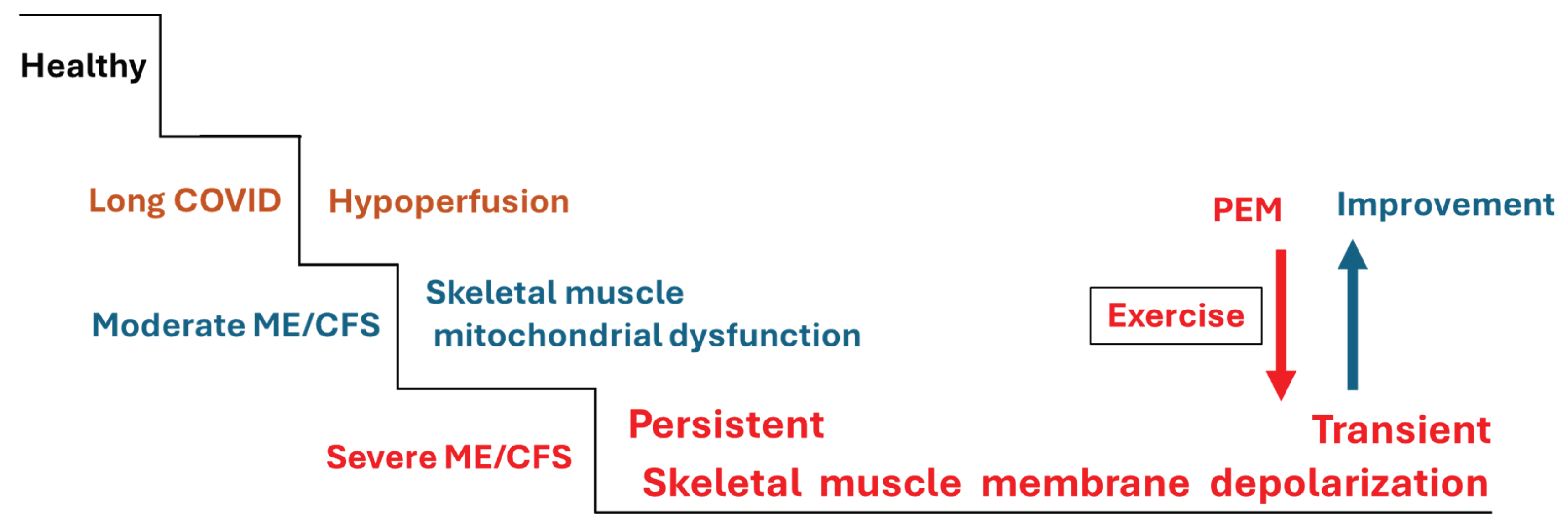

From these considerations one may conclude that skeletal muscle of a patient with moderate disease who is in a longer-lasting episode of PEM could also be in a (transient) depolarized state. Skeletal muscles may be in a depolarized state for a longer time, but the patient may be able to overcome excessive depolarization to return to the stage of mitochondrial dysfunction (

Figure 3). In support of this idea, EMG-changes were found in about half of ME/CFS patients after a cycling exercise. The M-wave amplitude significantly decreased in leg muscles and the M-wave duration significantly increased [

84]. This measurement with surface electrodes does not assess membrane voltage but a surface summation potential so that it does not directly reveal sarcolemmal depolarization. The decrease in amplitude and the longer duration suggests a less effective recruitment of muscle fibers and a delayed propagation of the excitation that, after exclusion of neuronal causes, can be explained with membrane depolarization as a fraction of excitatory sodium channels would have been in the inactivated state. This suggests that even in mild to moderate ME/CFS sarcolemmal depolarization can occur. Interestingly, in the group of patients developing exercise-induced M-wave alterations, resting values of handgrip strength were significantly lower and symptoms were more serious than in patients without M-wave abnormalities. Hence, the known correlation between loss of muscle force and symptoms also seems to apply to EMG-changes (disturbed excitability). This is not surprising as we see the disturbed electrophysiology behind the demonstrated EMG-changes as the cause for the loss of force.

These considerations also help to understand why a loss of force after diagnosis correlates with symptoms and poor prognosis [

16]. The main cause for the loss of force, an insufficient Na

+/K

+-ATPase-activity, is also the main cause for sodium-induced calcium-overload that causes skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction, the key pathomechanism in our ME/CFS disease concept.

9. Conclusions

Insufficient activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase can explain mitochondrial dysfunction via sodium induced calcium overload causing diminished oxidative phosphorylation and lack of energy, fatigue and loss of endurance as well as a disturbance of skeletal muscle electrophysiology. The latter leads to chronic depolarization of the sarcolemma to explain both loss of force by impairing action potential propagation and fiber recruitment and fasciculations (hyperexcitability). Skeletal muscle depolarization may play a strong role in the myasthenia of these severely ill ME/CFS patients. It may also become part of a vicious circle that increases sodium loading by inappropriate excitations to further raise mitochondrial damage by calcium overload.

References

- Choutka J, Jansari V, Hornig M, Iwasaki A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nature Medicine 2022;28:911–23.

- Kedor C, Freitag H, Meyer-Arndt L, Wittke K, Hanitsch LG, Zoller T, et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nature Communications 2022;13:5104. [CrossRef]

- Peter RS, Nieters A, Göpel S, Merle U, Steinacker JM, Deibert P, et al. Persistent symptoms and clinical findings in adults with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19/post-COVID-19 syndrome in the second year after acute infection: A population-based, nested case-control study. PLoS Medicine 2025;22:e1004511.

- Hill E, Mehta H, Sharma S, Mane K, Xie C, Cathey E, et al. Risk factors associated with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in an EHR cohort: a national COVID cohort collaborative (N3C) analysis as part of the NIH RECOVER program. medRxiv 2022.

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequelae of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nature Medicine 2023;29:2347–57.

- Steinacker JM, Klinkisch E-M. Halbierte Sichtbarkeit: Aktivität und Rehabilitationsmaßnahmen bei postakuten Infektionssyndromen The (In-) Visible Half: Activity and Rehabilitation Measures for Post-acute Infection Syndromes. Verhaltenstherapie 2025.

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med 2011;270:327–38. [CrossRef]

- Ballouz T, Menges D, Anagnostopoulos A, Domenghino A, Aschmann HE, Frei A, et al. Recovery and symptom trajectories up to two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: population based, longitudinal cohort study. Bmj 2023;381.

- van Campen C, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Cerebral Blood Flow Is Reduced in Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients During Mild Orthostatic Stress Testing: An Exploratory Study at 20 Degrees of Head-Up Tilt Testing. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- van Campen CMC, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Worsening Symptoms Is Associated with Larger Cerebral Blood Flow Abnormalities during Tilt-Testing in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Medicina 2023;59. [CrossRef]

- Ryabkova VA, Churilov LP, Shoenfeld Y. Neuroimmunology: what role for autoimmunity, neuroinflammation, and small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and adverse events after human papillomavirus vaccination? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019;20:5164.

- Cervia-Hasler C, Brüningk SC, Hoch T, Fan B, Muzio G, Thompson RC, et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science 2024;383:eadg7942.

- Haunhorst S, Dudziak D, Scheibenbogen C, Seifert M, Sotzny F, Finke C, et al. Towards an understanding of physical activity-induced post-exertional malaise: Insights into microvascular alterations and immunometabolic interactions in post-COVID condition and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Infection 2024:1–13.

- Conroy K, Bhatia S, Islam M, Jason LA. Homebound versus bedridden status among those with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. vol. 9, MDPI; 2021, p. 106.

- Sommerfelt K, Schei T, Angelsen A. Severe and very severe Myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome me/Cfs in Norway: symptom burden and access to care. J Clin Med 2023;12:1487.

- Paffrath A, Kim L, Kedor C, Stein E, Rust R, Freitag H, et al. Impaired hand grip strength correlates with greater disability and symptom severity in post-COVID Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024;13:2153.

- Jäkel B, Kedor C, Grabowski P, Wittke K, Thiel S, Scherbakov N, et al. Hand grip strength and fatigability: correlation with clinical parameters and diagnostic suitability in ME/CFS. Journal of Translational Medicine 2021;19:1–12.

- Nacul LC, Mudie K, Kingdon CC, Clark TG, Lacerda EM. Hand grip strength as a clinical biomarker for ME/CFS and disease severity. Frontiers in Neurology 2018;9:992.

- do Amaral CMSSB, da Luz Goulart C, da Silva BM, Valente J, Rezende AG, Fernandes E, et al. Low handgrip strength is associated with worse functional outcomes in long COVID. Scientific Reports 2024;14:2049. [CrossRef]

- Blitshteyn S, Ruhoy IS, Natbony LR, Saperstein DS. Internal Tremor in Long COVID May Be a Symptom of Dysautonomia and Small Fiber Neuropathy. Neurology International 2024;17:2.

- Zhou T, Sawano M, Arun AS, Caraballo C, Michelsen T, McAlpine LS, et al. Internal tremors and vibrations in long COVID: a cross-sectional study. The American Journal of Medicine 2024.

- Appelman B, Charlton BT, Goulding RP, Kerkhoff TJ, Breedveld EA, Noort W, et al. Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nature Communications 2024;15:17. [CrossRef]

- Bizjak DA, Ohmayer B, Buhl JL, Schneider EM, Walther P, Calzia E, et al. Functional and Morphological Differences of Muscle Mitochondria in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Post-COVID Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024;25. [CrossRef]

- Joseph P, Arevalo C, Oliveira RKF, Faria-Urbina M, Felsenstein D, Oaklander AL, et al. Insights From Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing of Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. CHEST 2021;160:642–51. [CrossRef]

- de Boer E, Petrache I, Goldstein NM, Olin JT, Keith RC, Modena B, et al. Decreased fatty acid oxidation and altered lactate production during exercise in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2022;205:126–9.

- Hoel F, Hoel A, Pettersen IK, Rekeland IG, Risa K, Alme K, et al. A map of metabolic phenotypes in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight 2021;6:e149217.

- Vollrath S, Bizjak DA, Zorn J, Matits L, Jerg A, Munk M, et al. Recovery of performance and persistent symptoms in athletes after COVID-19. PLoS One 2022;17:e0277984.

- Guarnieri JW, Haltom JA, Albrecht YES, Lie T, Olali AZ, Widjaja GA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mitochondrial metabolic and epigenomic reprogramming in COVID-19. Pharmacological Research 2024;204:107170.

- Charlton BT, Slaghekke A, Appelman B, Eggelbusch M, Huijts JY, Noort W, et al. Skeletal muscle properties in long COVID and ME/CFS differ from those induced by bed rest. medRxiv 2025:2025–05.

- Scheibenbogen C, Wirth KJ. Key pathophysiological role of skeletal muscle disturbance in post COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): accumulated evidence. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2025;16:e13669.

- Wirth KJ, Scheibenbogen C. Pathophysiology of skeletal muscle disturbances in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). J Transl Med 2021;19:162. [CrossRef]

- Semsarian C, Wu M-J, Ju Y-K, Marciniec T, Yeoh T, Allen DG, et al. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is mediated by a Ca2+-dependent calcineurin signalling pathway. Nature 1999;400:576–81.

- Wirth KJ, Löhn M. Microvascular Capillary and Precapillary Cardiovascular Disturbances Strongly Interact to Severely Affect Tissue Perfusion and Mitochondrial Function in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Evolving from the Post COVID-19 Syndrome. Medicina 2024;60. [CrossRef]

- Clausen T, Andersen SL, Flatman JA. Na(+)-K+ pump stimulation elicits recovery of contractility in K(+)-paralysed rat muscle. J Physiol 1993;472:521–36. [CrossRef]

- Murphy KT, Clausen T. The importance of limitations in aerobic metabolism, glycolysis, and membrane excitability for the development of high-frequency fatigue in isolated rat soleus muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2007;292:R2001–11.

- Nielsen OB, Clausen T. The significance of active Na+, K+ transport in the maintenance of contractility in rat skeletal muscle. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 1996;157:199–209.

- Wareham, AC. Effect of denervation and ouabain on the response of the resting membrane potential of rat skeletal muscle to potassium. Pflügers Archiv 1978;373:225–8.

- Petter E, Scheibenbogen C, Linz P, Stehning C, Wirth K, Kuehne T, et al. Muscle sodium content in patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022;20:580. [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T. Role of Na+, K+-pumps and transmembrane Na+, K+-distribution in muscle function: The FEPS Lecture–Bratislava 2007. Acta Physiologica 2008;192:339–49.

- Pirkmajer S, Chibalin AV. Na,K-ATPase regulation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2016;311:E1–31. [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T. Na+-K+ Pump Regulation and Skeletal Muscle Contractility. Physiological Reviews 2003;83:1269–324. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen OB, Harrison AP. The regulation of the Na+, K+ pump in contracting skeletal muscle. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 1998;162:191–200.

- Odoom JE, Kemp GJ, Radda GK. The regulation of total creatine content in a myoblast cell line. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 1996;158:179–88.

- Zorzano A, Fandos C, PalacÍN M. Role of plasma membrane transporters in muscle metabolism. Biochemical Journal 2000;349:667–88.

- Page MJ, Di Cera E. Role of Na+ and K+ in enzyme function. Physiological Reviews 2006;86:1049–92.

- Scheibenbogen C, Loebel M, Freitag H, Krueger A, Bauer S, Antelmann M, et al. Immunoadsorption to remove ß2 adrenergic receptor antibodies in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome CFS/ME. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193672. [CrossRef]

- Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S, Eschenhagen T. What is the role of β-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circulation Research 2003;93:896–906.

- Abrams RMC, Simpson DM, Navis A, Jette N, Zhou L, Shin SC. Small fiber neuropathy associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Muscle & Nerve 2022;65:440–3. [CrossRef]

- Oaklander AL, Nolano M. Scientific Advances in and Clinical Approaches to Small-Fiber Polyneuropathy: A Review. JAMA Neurol 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cabanas H, Muraki K, Balinas C, Eaton-Fitch N, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. Validation of impaired Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 3 ion channel activity in natural killer cells from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients. Molecular Medicine 2019;25:14. [CrossRef]

- Cabanas H, Muraki K, Eaton N, Balinas C, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. Loss of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 3 ion channel function in natural killer cells from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients. Molecular Medicine 2018;24:44. [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Fitch N, Du Preez S, Cabanas H, Muraki K, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. Impaired TRPM3-dependent calcium influx and restoration using Naltrexone in natural killer cells of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022;20:94. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Carbajo L, Alpizar YA, Startek JB, Lopez-Lopez JR, Perez-Garcia MT, Talavera K. Activation of the cation channel TRPM3 in perivascular nerves induces vasodilation of resistance arteries. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2019;129:219–30. [CrossRef]

- Held K, Kichko T, De Clercq K, Klaassen H, Van Bree R, Vanherck J-C, et al. Activation of TRPM3 by a potent synthetic ligand reveals a role in peptide release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015;112:E1363–72. [CrossRef]

- Held K, Tóth BI. TRPM3 in brain (patho) physiology. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021;9:635659.

- Jammes Y, Adjriou N, Kipson N, Criado C, Charpin C, Rebaudet S, et al. Altered muscle membrane potential and redox status differentiates two subgroups of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med 2020;18:173. [CrossRef]

- Al Masoodi WTM, Radhi SW, Abdalsada HK, Niu M, Al-Hakeim HK, Maes M. Increased galanin-galanin receptor 1 signaling, inflammation, and insulin resistance are associated with affective symptoms and chronic fatigue syndrome due to long COVID. PLoS One 2025;20:e0316373.

- Allain TJ, Bearn JA, Coskeran P, Jones J, Checkley A, Butler J, et al. Changes in growth hormone, insulin, insulinlike growth factors (IGFs), and IGF-binding protein-1 in chronic fatigue syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 1997;41:567–73. [CrossRef]

- Beentjes SV, Miralles Méharon A, Kaczmarczyk J, Cassar A, Samms GL, Hejazi NS, et al. Replicated blood-based biomarkers for myalgic encephalomyelitis not explicable by inactivity. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2025:1–24.

- Al-Hakeim HK, Khairi Abed A, Rouf Moustafa S, Almulla AF, Maes M. Tryptophan catabolites, inflammation, and insulin resistance as determinants of chronic fatigue syndrome and affective symptoms in long COVID. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2023;16:1194769.

- Agergaard J, Yamin Ali Khan B, Engell-Sørensen T, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Østergaard L, Hejbøl EK, et al. Myopathy as a cause of Long COVID fatigue: Evidence from quantitative and single fiber EMG and muscle histopathology. Clinical Neurophysiology 2023;148:65–75. [CrossRef]

- Jammes Y, Retornaz F. Understanding neuromuscular disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome. F1000Res 2019;8:F1000-Faculty.

- Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/Calcium Exchange: Its Physiological Implications. Physiological Reviews 1999;79:763–854. [CrossRef]

- Dutka TL, Lamb GD. Na+-K+ pumps in the transverse tubular system of skeletal muscle fibers preferentially use ATP from glycolysis. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2007;293:C967–77.

- Ghali A, Lacout C, Ghali M, Gury A, Beucher A-B, Lozac’h P, et al. Elevated blood lactate in resting conditions correlate with post-exertional malaise severity in patients with Myalgic encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome. Scientific Reports 2019;9:18817.

- Nelson MJ, Bahl JS, Buckley JD, Thomson RL, Davison K. Evidence of altered cardiac autonomic regulation in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019;98:e17600.

- Wyller VB, Eriksen HR, Malterud K. Can sustained arousal explain the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Behavioral and Brain Functions 2009;5:1–10.

- Löhn M, Wirth KJ. Potential pathophysiological role of the ion channel TRPM3 in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and the therapeutic effect of low-dose naltrexone. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024;22:630. [CrossRef]

- Seljeset S, Liebowitz S, Bright DP, Smart TG. Pre-and postsynaptic modulation of hippocampal inhibitory synaptic transmission by pregnenolone sulphate. Neuropharmacology 2023;233:109530.

- Hoheisel F, Fleischer KM, Rubarth K, Sepulveda N, Bauer S, Konietschke F, et al. Autoantibodies to Arginine-rich Sequences Mimicking Epstein-Barr Virus in Post-COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. medRxiv 2024:2024–12.

- Nakano Y, Wiechert S, Bánfi B. Overlapping activities of two neuronal splicing factors switch the GABA effect from excitatory to inhibitory by regulating REST. Cell Reports 2019;27:860–71.

- Schlauch KA, Khaiboullina SF, De Meirleir KL, Rawat S, Petereit J, Rizvanov AA, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic variations in subjects with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Translational Psychiatry 2016;6:e730–e730.

- Artalejo AR, Olivos-Oré LA. Alpha2-adrenoceptors in adrenomedullary chromaffin cells: functional role and pathophysiological implications. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology 2018;470:61–6.

- Wirth KJ, Scheibenbogen C, Paul F. An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine 2021;19:471. [CrossRef]

- Gyires K, Zádori ZS, Török T, Mátyus P. α2-Adrenoceptor subtypes-mediated physiological, pharmacological actions. Neurochemistry International 2009;55:447–53.

- Gyires K, Zádori ZS, Török T, Mátyus P. α2-Adrenoceptor subtypes-mediated physiological, pharmacological actions. Neurochemistry International 2009;55:447–53.

- Scherbakov N, Szklarski M, Hartwig J, Sotzny F, Lorenz S, Meyer A, et al. Peripheral endothelial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. ESC Heart Fail 2020;7:1064–71. [CrossRef]

- van Campen CM, Visser FC. The Relation Between Cardiac Output and Cerebral Blood Flow in ME/CFS Patients with a POTS Response During a Tilt Test. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025;14:3648.

- Rosin DL, Zeng D, Stornetta RL, Norton FR, Riley T, Okusa MD, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors in catecholaminergic and other brainstem neurons in the rat. Neuroscience 1993;56:139–55. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi Y, Maze M. Alpha2 adrenoceptor agonists and anaesthesia. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 1993;71:108–18.

- Wyller VB, Saul JP, Walløe L, Thaulow E. Sympathetic cardiovascular control during orthostatic stress and isometric exercise in adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2008;102:623–32. [CrossRef]

- Van der Stede T, Van de Loock A, Turiel G, Hansen C, Tamariz-Ellemann A, Ullrich M, et al. Cellular deconstruction of the human skeletal muscle microenvironment identifies an exercise-induced histaminergic crosstalk. Cell Metabolism 2025;37:842-856.e7. [CrossRef]

- Wirth K, Scheibenbogen C. A Unifying Hypothesis of the Pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ss2-adrenergic receptors. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19:102527. [CrossRef]

- Retornaz F, Stavris C, Jammes Y. Consequences of sarcolemma fatigue on maximal muscle strength production in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Biomechanics 2023;108:106055.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).