Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Exponential Growth of Human Needs

1.2. Human Agreements

2. Methods

- 1)

- The CSRD described above includes the development of ESRS; companies within the CSRD will have to report on double materiality — financial and impact materiality.

- 2)

- The aim of CSDDD is to foster sustainable and responsible corporate behavior in companies’ operations and across their global value chains; it limits the information large companies can request from SMEs and small mid-cap business partners to that laid out in the CSRD’s VSME.

- 3)

- The EU taxonomy helps direct investments to the economic activities most needed for the transition, in line with the European Green Deal objectives. The taxonomy is a classification system that defines criteria for economic activities that are aligned with a net-zero trajectory by 2050 and the broader environmental goals, other than climate.

- 4)

- CBAM is the EU’s tool to put a fair price on carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive goods that are entering the EU, and to encourage cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries.

3. Results

3.1. GRI Standards

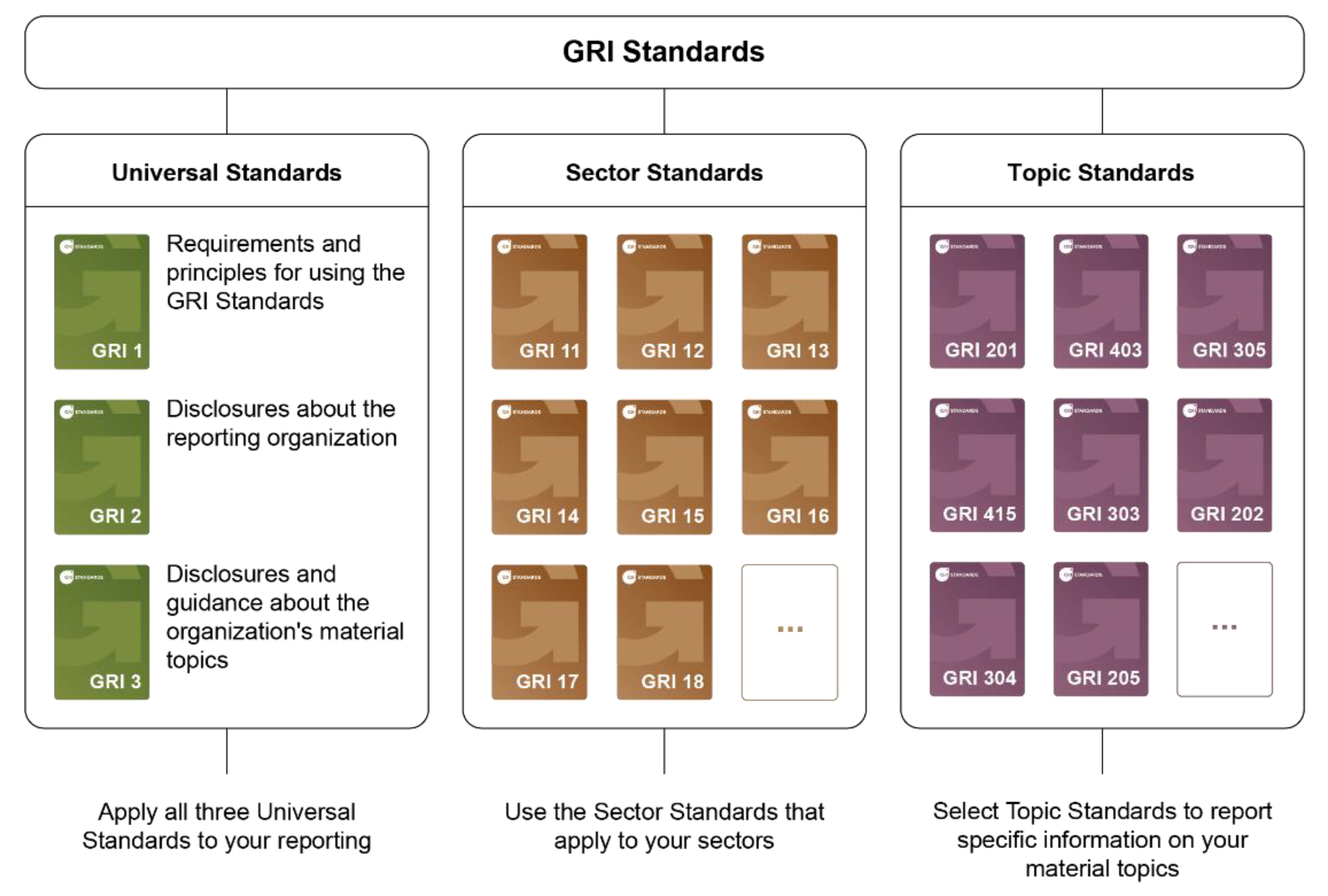

- GRI 1, Foundation 2021, explains the purpose of the GRI Standards, their critical concepts, and usage. It presents the requirements that an organization must fulfil to report according to the GRI Standards. It must respect the elementary principles of good-quality reporting, e.g., accuracy, balance, and verifiability.

- GRI 2, General Disclosures 2021, includes disclosures of the organization: structure and reporting practices, activities and workers, governance, strategy, policies, practices, and stakeholder engagement. The profile of the organization and its scale are presented, providing a context for understanding.

- GRI 3, Material Topics 2021, gives the steps that help the organization to determine the most relevant topics, their impacts, materials, and how the Sector Standards are used in this process. It also discloses the list of material topics, the process of determining them, and how it manages each topic.

- Basic materials and needs (oil and gas, coal, agriculture and aquaculture with fishing, mining, food and beverages, textiles and apparel, banking, insurance, capital markets, utilities, renewable energy, forestry, metal processing).

- Industry (construction materials, aerospace and defense, automotive, construction, chemicals, machinery and equipment, pharmaceuticals, electronics).

- Transport, infrastructure and tourism (media and communication, software, real estate, transportation infrastructure, shipping, trucking, airlines, trading with distribution and logistics, packaging, hotels).

- Other services and light manufacturing (educational services, household durables, managed healthcare, medical equipment and services, retail, security services, restaurants, commercial services, non-profit organizations).

- 1)

- Supply chain sustainability and responsible sourcing: supplier engagement, selection, screening and auditing, sustainable materials, supply chain impacts, supply chain management.

- 1.

- Governance and leadership: corporate management, sustainability program leadership, board structure and independence, risk management and business continuity, executive compensation, accountability.

- 2.

- Customer satisfaction and engagement: customer satisfaction, engagement and provision of information to customers and consumers.

- 3.

- Economic performance: direct economic value generated and distributed; other disclosures related to economic performance.

- 4.

- Ethical business conduct: prevention of anti-competitive practices, anti-corruption/anti-bribery practices, human rights, data security and privacy, responsible marketing and product labelling, transparency, regulatory compliance, animal welfare, and clinical trials.

- 5.

- Innovation and R&D: research in unmet needs, developing new technologies, innovative solutions, and intellectual property.

- 6.

- Market presence and pricing: growth strategy in emerging/developed markets, pricing and affordability of products and solutions.

- 7.

- Product safety and quality: product responsibility, product safety design, quality management, customer health and safety.

- 1)

- Air quality and other emissions: ozone-depleting substances, NOX and SOX, other (non-GHG) emissions.

- 2)

- Chemicals and hazardous materials: management of toxic substances, hazardous materials, chemicals, and restricted substances.

- 3)

- Climate change and energy-related GHG emissions: climate change strategy, carbon footprint reductions (Scopes 1, 2 and 3), energy consumption and efficiency, renewable energy.

- 4)

- Sustainable products and solutions: Life Cycle Assessment, sustainable design, product take-back, resource efficiency, product energy efficiency.

- 5)

- Waste management: waste generation and recycling, electronic and hazardous waste, and packaging waste.

- 6)

- Water and effluents: water consumption, effluents and wastewater management, water scarcity.

- 1.

- Community and donations: volunteerism, philanthropy, local development, engagement and dialogue with local communities, non-governmental organizations, local governments, academia, etc.

- 2.

- Diversity and inclusion: employee diversity and inclusion, equal opportunity, non-discrimination, gender equality.

- 3.

- Labor practices: employment practices, labor management relations, freedom of association and collective bargaining, forced or compulsory labor, child labor.

- 4.

- Occupational health and safety (OHS): hazard minimization precautions, employee health, safety and well-being, emergency response plans, occupational accidents, biosafety and laboratory biosecurity, OHS management system.

- 5.

- Talent attraction, development and retention: training and development, recruitment, career management and promotion, compensation and benefits.

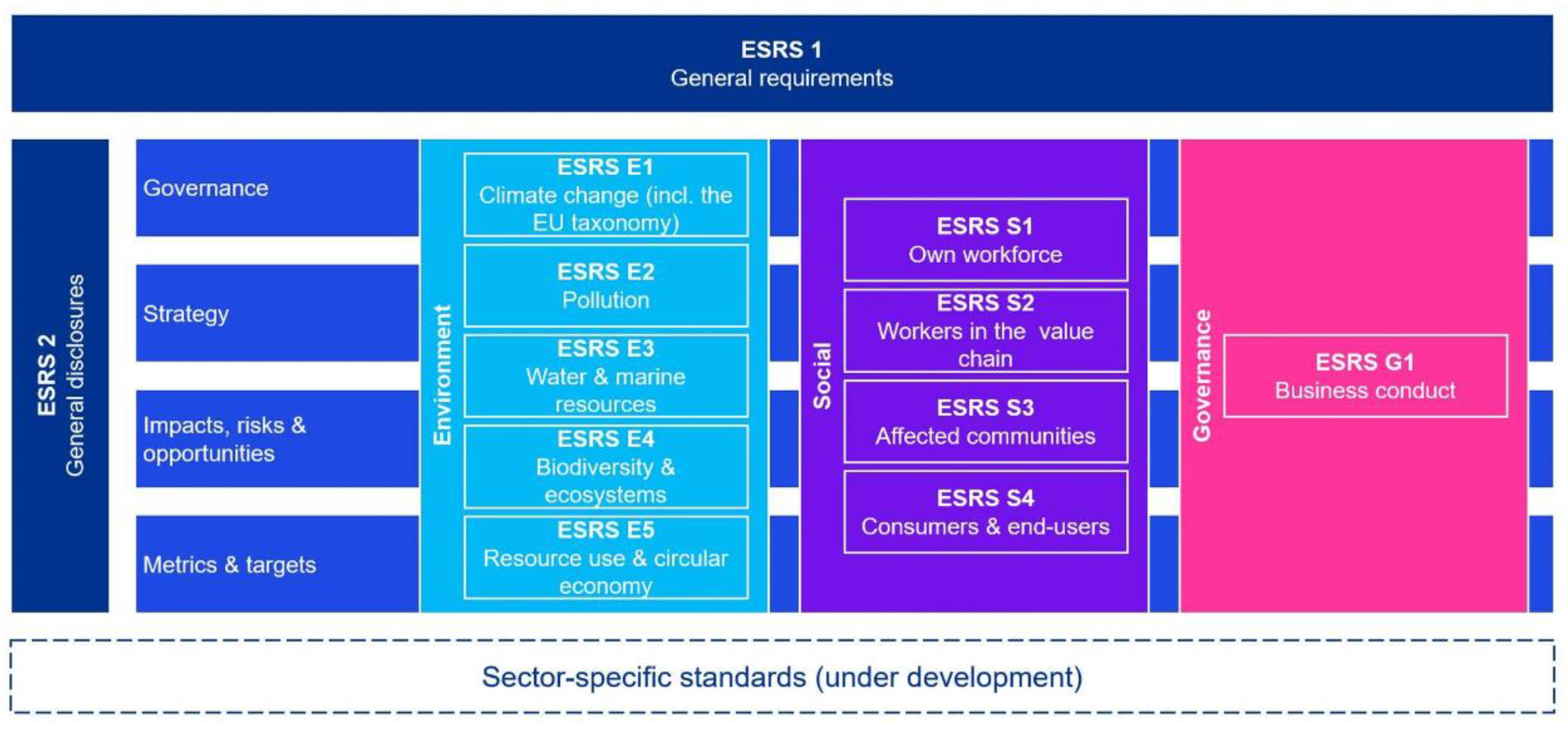

3.2. ESRS Standards

- ESRS LSME (ESRS for Listed Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises): The standard offers simplified and proportionally adjusted reporting for small and medium-sized listed companies, while the comprehensive ESRS standard requires detailed and in-depth disclosure of all relevant sustainability aspects in accordance with the CSRD.

- ESRS VSME (Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for non-listed SMEs): The Standard offers a voluntary and greatly reduced reporting scheme that is geared to the limited resources of very small companies. A helpful Word report template for the VSME standard is available, and it additionally compiles all report requirements in a clear VSME data point list.

3.3. ISO Standards

3.4. Other International Sustainability Reporting Standards

3.5. National Sustainability Reporting Standards

3.5. Reporting Sustainability in the Public Sector

3.5.1. Sustainability Reporting in the Higher Education Sector

- a)

- Human Rights: 1) Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights; and 2) make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses.

- b)

- Labor: 3) Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; 4) the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labor; 5) the effective abolition of child labor; and 6) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

- c)

- Environment: 7) Businesses should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges; 8) undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; and 9) encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies.

- d)

- Anti-Corruption: 10) Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery.

4. Discussion

4.1. Corporate Sustainability Reporting Standards

4.2. Public Sustainability Reporting Standards

4.3. Personal and Community Sustainability Reporting

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AASB | Australian Accounting Standards Board |

| AASHE | Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education |

| ASRS | Australian Sustainability Reporting Standard |

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| CCDAA | Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act |

| CIPFA | Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy |

| CDP | Carbon Disclosure Project |

| CF | Carbon Footprint |

| CFO | Chief Financial Officers |

| CSDDD | Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CSRS | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| CSSB | Canadian Sustainability Standards Board |

| DEI | Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion |

| EF | Ecological Footprint |

| EFRAG | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| EU | European Union |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| GSSB | Global Sustainability Standards Board |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| IPSASB | International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| KPI | key performance indicator |

| NFRD | Non-Financial Reporting Directive |

| OHS | Occupational Health and Safety |

| SASB | Sustainability Accounting Standards Board |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| TCFD | Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures |

| UN | United Nations |

| US | United States (of America) |

| VSME | Voluntary Reporting Standard for SMEs |

References

- Roser, M.; Mortality in the past: every second child died, Our World in Data. November 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H.; How has world population growth changed over time? Our World in Data. 1 June 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth-over-time (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Fleck, A.; A History of Resource Extraction and Acceleration, Statista. 31 July 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/32750/global-extraction-of-the-four-main-material-groups/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- WEF, World Economic Forum. The number of cars worldwide is set to double by 2040. 22 April 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2016/04/the-number-of-cars-worldwide-is-set-to-double-by-2040/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M.; Energy Production and Consumption. Our World in Data. January 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/energy-production-consumption#article-citation (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M.; Greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data. January 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M.; Breakdown of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions by sector. Our World in Data. January 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- United Nations, Climate change, Process and meetings. Available online: https://unfccc.int/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ritchie, H.; How much CO2 can the world emit while keeping warming below 1.5 °C and 2 °C? Our World in Data. 29 September 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/how-much-co2-can-the-world-emit-while-keeping-warming-below-15c-and-2c (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- OECD (2015), The Economic Consequences of Climate Change, OECD Publishing, Paris. 3 November 2015. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264235410-en (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 25 September 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement. 12 December 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. O.J. 2014 (L. 330) 1–9.

- Directive 2022/2464/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. O.J. 2022 (L 322) 15–80.

- European Commission, Simplification: Council gives final green light on the ‘Stop-the-clock’ mechanism to boost EU competitiveness and provide legal certainty to businesses. 14 April 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/04/14/simplification-council-gives-final-green-light-on-the-stop-the-clock-mechanism-to-boost-eu-competitiveness-and-provide-legal-certainty-to-businesses/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Commission adopts “quick fix” for companies already conducting corporate sustainability reporting. 11 July 2025. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/commission-adopts-quick-fix-companies-already-conducting-corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Reuter, A.S.; EU Omnibus proposal: Essential insights and how to navigate the upcoming changes. Sphera. Available online: https://www.sphera.com (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- IMD. Best practices in ESG reporting: enhancing corporate responsibility. August 2025. Available online: https://www.imd.org/blog/sustainability/esg-reporting/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Institute of Directors. Sustainability and ESG – What’s the difference? 17 July 2024. Available online: https://www.iod.com/resources/sustainable-business/sustainability-and-esg-whats-the-difference/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- European Commission. Questions and answers on simplification omnibus I and II. 26 February 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_615 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative, GRI. Continuous improvement. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- GRI Standards. A Short Introduction to the GRI Standards. Available online: http://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB). GRI Sector Program – List of prioritized sectors, Revision 3. 19 October 2021. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/mqznr5mz/gri-sector-program-list-of-prioritized-sectors.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Agilent. Final List of Topics, Example Sub-topics and GRI Standards to Consider. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/environment/Material%20Topics%20and%20Sub%20topic%202019.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- The GRI Standards: A guide for policy makers. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/nmmnwfsm/gri-policymakers-guide.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards, C/2023/5303. OJ L 2023, 2772, 1–284.

- CSR Tools. ESRS – short and compact. Available online: https://csr-tools.com/en/esrs/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- KPMG. ESRS. Available online: https://kpmg.com/se/en/services/esg-sustainability/esrs.html (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization). Building a sustainable path to ESG reporting. Available online: https://www.iso.org/climate-change/esg-reporting (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Duvernay, G.; Plan A. All ISO standards for ESG and sustainability. 27 May 2025. Available online: https://plana.earth/academy/iso-esg (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Poirmeur, P. Top 10 ISO sustainability standards. Available online: https://www.trustditto.com/en/resources/blog/top-10-iso-sustainability-standards#iso-14001-environmental-management-system (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- KPMG. The move to mandatory reporting: Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2024. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/our-insights/esg/the-move-to-mandatory-reporting.html#accordion-57530f0dfc-item-b09872126f (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- GRI. GRI and sustainability reporting in the EU. July 2024. Available online: https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.globalreporting.org/media/d4faazel/gri-and-the-esrs-qa-final.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- EFRAG. Amended ESRS Exposure Draft. July 2025. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2025-07/Amended_ESRS_Exposure_Draft_July_2025_ESRS_1.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Brightest. The Top 7 Sustainability Reporting Standards in 2024. Available online: https://www.brightest.io/sustainability-reporting-standards#issb (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- EcoActive. Canadian Sustainability Disclosure Standards: Timeline, Scope and What’s Next. 4 August 2025. Available online: https://ecoactivetech.com/csds-1-2-esg-reporting-canada/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers) Indonesia, Spotlight on sustainability: National Sustainability Reporting Framework. October 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/my/en/publications/2024/national-sustainability-reporting-framework.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Keslio. Sustainability Reporting Requirements in the United States. 2 January 2025. Available online: https://www.keslio.com/kesliox/sustainability-reporting-requirements-in-the-united-states (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- PwC. Sustainability reporting standards and legislation finalized: mandatory sustainability reporting begins. Available online: https://www.pwc.com.au/assurance/sustainability-reporting-and-assurance/australian-sustainability-reporting-standards.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- China Briefing. China Unveils Its First Set of Basic Standards for Corporate Sustainability (ESG) Disclosure. Available online: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-unveils-basic-standards-for-corporate-sustainability-esg-disclosure/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- ESG Today. Japan Releases Inaugural IFRS-Aligned Sustainability Reporting Standards. Disclosure. 6 March 2025. Available online: https://www.esgtoday.com/japan-releases-inaugural-ifrs-aligned-sustainability-reporting-standards/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- UK government. Guidance – UK Sustainability Reporting Standards. 25 June 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/uk-sustainability-reporting-standards (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- IPSASB. Advancing Public Sector Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://www.ipsasb.org/focus-areas/sustainability-reporting (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Leal Filho, W.; Coronado-Marín, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Silva, F.F.; Wolf, F.; LeVasseur, T.; Kirrane, M.J.; Doni, F.; Paço, A.; Blicharska, M.; et al. International Trends and Practices on Sustainability Reporting in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abello-Romero, J.; Mancilla, C.; Restrepo, K.; Sáez, W.; Durán-Seguel, I.; Ganga-Contreras, F. Sustainability Reporting in the University Context—A Review and Analysis of the Literature. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggi, S. Sustainability reporting, universities and global reporting initiative applicability: a still open issue. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14/4, 699–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE). STARS, The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System. Available online: https://stars.aashe.org/about-stars/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- United Nations Global Compact. The power of principles. Available online: https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- University of Indonesia. UI GreenMetric World University Ranking. Available online: https://greenmetric.ui.ac.id/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- GRI and EFRAG. GRI-ESRS Interoperability Index. Version 1. 22 November 2024. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/qzmoeixv/esrs-gri-interoperability-index-november-2024.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- IFRS. GRI and IFRS Foundation collaboration to deliver full interoperability that enables seamless sustainability reporting. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2024/05/gri-and-ifrs-foundation-collaboration-to-deliver-full-interoperability/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- EFRAG and IFRS. ESRS–ISSB Standards Interoperability Guidance. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/sites/default/files/sites/webpublishing/SiteAssets/ESRS-ISSB%20Standards%20Interoperability%20Guidance.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- EFRAG. Voluntary reporting standard for SMEs (VSME). Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/projects/voluntary-reporting-standard-for-smes-vsme/concluded (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Buchanan, R.; Trump 2.0: potential impact on sustainability regulations and reporting. Jupiter, 29 January 2025. Available online: https://www.jupiteram.com/global/en/corporate/insights/trump-potential-impact-sustainability-regulations-reporting/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Salesforce, Net Zero. California’s Climate Disclosure Laws: A Guide for Companies. Available online: https://www.salesforce.com/net-zero/california-climate-disclosure-laws/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- GRI. Sustainability disclosure still driven by voluntary policies. 18 November 2024. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/news/news-center/sustainability-disclosure-still-driven-by-voluntary-policies/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Worldfavor guide. The sustainability reporting playbook. 2024; pp. 8,9.

- OECD. Advancing public sector sustainability reporting. OECD papers on budgeting, Vol. 2025/05. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/06/advancing-public-sector-sustainability-reporting_6f80aa9d/ad5fb10f-en.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Adams, C.A.; Public sector sustainability reporting: time to step it up. CIPFA. April 2023. Available online: https://www.cipfa.org/protecting-place-and-planet/sustainability-reporting (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Mantzikopoulou, N.; The Power of Individual and Systemic Action in Driving Sustainability. AIMS International. 23 April 2025. Available online: https://www.aimsinternational.com/news/the-power-of-individual-and-systemic-action-in-driving-sustainability (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Levermann, A.; Individuals can’t solve the climate crisis. Governments need to step up. The Guardian, 10 July 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/10/individuals-climate-crisis-government-planet-priority (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Cohen, S.; Responsibility in the Transition to Environmental Sustainability. Columbia Climate School. 10 May 2021. Available online: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/05/10/the-role-of-individual-responsibility-in-the-transition-to-environmental-sustainability/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Global Footprint Network. How Ecological Footprint accounting helps us recognize that engaging in meaningful climate action is critical for our own success. 9 November 2017. Available online: https://www.footprintnetwork.org/2017/11/09/ecological-footprint-climate-change/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- CO2NEWS. Carbon Footprint vs. Ecological Footprint: What’s the Difference and Why Does It Matter? 9 November 2024. Available online: https://www.co2news.sk/en/2024/11/09/carbon-footprint-versus-ecological-footprint-what-is-the-difference-and-why-does-it-matter/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- UN. Pact for the Future: A Vision for Global Collaboration. 28 November 2024. Available online: https://unric.org/en/pact-for-the-future/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).