1. Introduction

Breathing is one of the most essential processes for sustaining human life. Through a complex system of ventilation and diffusion, the lungs enable the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, ensuring cellular respiration and physiological stability. Any disruption to the respiratory system can have severe consequences, particularly when caused by chronic pulmonary diseases. Conditions such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and severe infections like asthma and pneumonia represent major global health burdens and are frequent causes of respiratory failure.

Biomedical engineering is conceived as the field that integrates the principles of engineering with biology and medicine, orienting its development toward optimizing healthcare through technological innovations. Its interdisciplinary nature allows for the articulation of areas such as physiology, human biology, molecular imaging, and tissue reconstruction, with the purpose of designing and perfecting technologies that facilitate the monitoring of physiological functions, as well as the diagnosis and treatment of various pathologies. Although its origins are closely linked to electrical engineering, biomedical engineering has evolved into an autonomous field that maintains the rigor of engineering principles while offering specific solutions to the challenges inherent to clinical practice and healthcare systems (Rondón et al., 2024). In this context, advances in mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO₂R) are paradigmatic examples of how biomedical engineering has transformed the management of respiratory failure, integrating physiological knowledge with highly complex technological developments.

The clinical approach to respiratory limitations has evolved significantly throughout the years. Mechanical ventilation remains the primary intervention for patients with impaired breathing, offering life-saving support in intensive care settings. However, its use may include risks, such as ventilator-induced lung injury, barotrauma, and infection. In response to these limitations, extracorporeal support systems, like extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO₂R), have emerged as advanced alternatives. These techniques provide direct blood oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal, thereby evolving the treatment for defective lung operations.

This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the physiology of breathing, the most common lung pathologies affecting respiration, and the technological evolution of ventilatory and extracorporeal support systems. By relating physiological foundations to clinical practice, this discussion emphasizes the crucial role of merging medical insight with technological development in respiratory management. Therefore, this review aims to bridge physiological principles, pathological mechanisms, and engineering-based technological solutions, providing a comprehensive understanding of ventilation and extracorporeal respiratory support.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Breathing and the Lungs

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, breathing is the act or process of taking air into your lungs and releasing it (Cambridge University Press & Assessment, 2025).

During breathing, air enters through the mouth or nose and travels through the trachea until it reaches the lungs. There, the air branches from the bronchi into the bronchioles and finally reaches the alveoli. Once in the alveoli, hemoglobin proteins circulating in the alveolar capillaries capture oxygen. Thanks to the heart’s pumping action, oxygen is distributed throughout the body, where cells use it to produce energy. During this process of aerobic cellular respiration, waste in the form of carbon dioxide is generated. The veins then transport the carbon dioxide back to the heart. From there, the pulmonary artery transports the carbon dioxide from the heart to the lungs, where it is distributed through the capillaries, ultimately reaching the alveoli. From the alveoli, carbon dioxide is expelled from the body through the respiratory tract during exhalation. In the alveoli, oxygen that enters the body during inhalation is exchanged with the carbon dioxide that is expelled (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2022).

A respiratory cycle consists of inhalation and exhalation of air. At rest, it is normal to complete between twelve and fifteen cycles per minute, although the respiratory cycle’s frequency may vary. An increased respiratory rate refers to tachypnea, while a decreased respiratory rate refers to bradypnea, and it is associated with central nervous system diseases (Empendium, 2025).

The breathing process begins when oxygen passes through the alveoli into the capillary network, where it enters the arterial system and eventually perfuses body tissues, and ends when the carbon dioxide is expelled (Haddad, 2023).

The lungs are the essential organs for respiration and gas exchange, allowing the absorption of oxygen and the elimination of carbon dioxide from the body. Combined with the diaphragm, they facilitate inhalation through muscle contraction, which expands the lungs and draws in air. In addition to their respiratory function, the lungs play other important roles, such as regulating blood pH by controlling CO₂ levels, filtering small gas bubbles in the bloodstream, and converting essential chemicals for blood pressure control. The lungs are further divided into individual lobes, which ultimately contain over 300 million alveoli.

3.2. Lung Pathologies

Lung damage caused by infection or inflammation can lead to numerous diseases, including asthma, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease, narrows the airways and causes symptoms like wheezing, cough, and breathlessness, with refractory asthma representing a severe form of asthma unresponsive to standard treatment (World Health Organization, 2024; Narasimhan, 2021). Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that fills alveoli with fluid or pus, causing symptoms such as cough with phlegm, fever, and chest pain (Mayo Clinic, 2021). COPD is a progressive lung disease, often caused by long-term exposure to irritants, and is marked by airflow obstruction, inflammation, and alveolar damage as seen in chronic bronchitis and emphysema (Mayo Clinic, 2021). ARDS, a life-threatening condition usually affecting critically ill patients, leads to fluid-filled alveoli and reduced oxygen exchange, often requiring mechanical ventilation, which can cause further lung injury (Mayo Clinic, 2022). These pathologies share symptoms like difficulty breathing and chest discomfort, and though they differ in cause and severity, they all significantly impact respiratory health.

Hypercapnia and hypoxemia are not diseases themselves but rather critical indicators of underlying respiratory or circulatory dysfunction. Hypercapnia refers to an excess buildup of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the bloodstream, typically resulting from hypoventilation or reduced respiratory efficiency. Mild symptoms may include flushed skin, headaches, fatigue, dizziness, drowsiness, and difficulty concentrating, while more severe cases can lead to confusion, paranoia, abnormal muscle spasms, panic attacks, irregular heart rhythms, hyperventilation, and even seizures (Jewell, 2018). In contrast, hypoxemia is characterized by abnormally low oxygen levels in the blood, often coming from inadequate oxygen intake or impaired oxygen delivery to the bloodstream. It can be caused by factors such as low atmospheric oxygen, slow or shallow breathing, impaired blood flow, and medical conditions like anemia, congenital heart disease, and various respiratory illnesses including asthma, ARDS, COPD, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism. Symptoms of hypoxemia include shortness of breath, rapid breathing, palpitations, and mental confusion (Mayo Clinic, 2023). Both conditions pose serious risks, especially in critically ill patients, and are often managed using life-support technologies like ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), which can help maintain adequate oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal when the lungs are unable to function properly on their own.

3.3. History and Development of the Mechanical Ventilator and Extracorporeal Life Support System

The evolution of mechanical lungs began with the invention of the iron lung in 1927 by Philip Drinker and Louis Agassiz. This 650-pound device used External Negative Pressure Ventilation (ENPV), enclosing the patient's body and using a bellows system to create negative pressure that facilitated airflow into and out of the lungs. Although groundbreaking, the iron lung was a large, immobile, and inconvenient device. The 1950s brought a major shift with the development of positive pressure ventilation, which manually pushed air into the lungs and led to the creation of mechanical ventilators. These ventilators were more compact and less invasive, delivering continuous airflow at a set pressure to prevent airway collapse. Today, positive pressure ventilation remains the primary method for mechanical respiratory support (Taylor, 2024).

Simultaneously, innovations in extracorporeal life support began to emerge. In the 1920s, Sergei Bryukhonenko developed the “autoejector,” a dual-pump system initially tested on dogs, which circulated blood even after the heart stopped. This inspired John Gibbon Jr. in the 1930s–1940s to design the first cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) machine for humans, successfully used to treat a woman with a pulmonary embolism. By the 1950s, membrane oxygenators made with polyethylene sheets were developed by Clowes, enhancing CPB technology for clinical applications. In the late 1960s, Dr. Robert Bartlett further advanced the field by creating ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) systems, which oxygenated blood outside the body before returning it to the patient (Brogan, 2021). These innovations laid the foundation for life-saving techniques in patients with severe respiratory failure.

During the 1970s and 1980s, ECMO technology expanded with Kolobow and Gattinoni introducing ECCO₂R (extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal) in animal models using an arteriovenous setup. In 1986, Gattinoni’s group transitioned to a venovenous configuration to treat patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), enabling gas exchange while minimizing ventilator-induced trauma (Stommel et al., 2024). From the 1990s to early 2000s, ECMO systems relied on roller pumps and silicone membranes, which often presented issues like moisture buildup and the need for multiple oxygenators. However, advancements between 2010 and 2021 introduced centrifugal pumps and polymethyl pentene (PMP) membranes, significantly improving performance and reducing complications, thereby enhancing the safety and efficiency of ECMO and ECCO₂R therapies (Brogan, 2021).

In the context of advanced respiratory failure, biomedical engineering has driven the development of devices that seek to replicate lung function beyond traditional extracorporeal support. While extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) remains the standard for temporary support, its limitations in terms of thrombotic risk and hospital dependence have motivated the exploration of implantable alternatives. Recent advances in biomaterials and microengineering have enabled the creation of gas exchange devices using hollow fiber membranes and biomimetic microchannel-based devices that emulate alveolar function, reducing associated complications and improving gas exchange efficiency. The incorporation of 3D bioprinting techniques and decellularized scaffolds repopulated with autologous cells also opens the possibility of biohybrid models capable of combining biocompatibility with physiological performance. These innovations represent a transformative horizon that links mechanical ventilation, ECMO, and ECCO₂R with the future perspective of implantable artificial lungs (Rondón et al., 2025).

3.4. The Mechanical Ventilator

A mechanical lung, or ventilator, provides life support for patients who cannot breathe independently. It supplies oxygen, removes carbon dioxide, keeps airways open, and maintains pressure to prevent alveolar collapse. This function is crucial because alveoli enable the exchange of gases between the lungs and bloodstream, allowing oxygen to reach body tissues during respiration (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

3.5. Types of Ventilators

Positive pressure ventilators are the primary method used in modern respiratory care, delivering air by continuously pushing it into the lungs, a technique that has significantly reduced patient mortality rates by nearly 60% (Gong & Sankari, 2022). Unlike outdated negative pressure methods, such as the iron lung, positive pressure ventilation is more efficient and widely adopted today (Physiopedia Contributors, 2025). These ventilators can be either noninvasive, using a face mask, or invasive, involving intubation through the mouth or neck (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). While invasive methods carry a higher risk of infection, they are necessary when noninvasive ventilation is inadequate (Strachan & Hughes, 2010). To minimize complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and pneumonia, lung-protective strategies, including lower tidal volumes, are recommended during invasive ventilation (Hickey et al., 2024).

3.6. ECMO vs. ECCO2R

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) and Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal (ECCO₂R) are advanced life support techniques used when conventional mechanical ventilation is insufficient. ECMO is a highly invasive method that provides substantial oxygenation and is used in critical respiratory failure (Titus et al., 2022). In contrast, ECCO₂R is a less invasive extracorporeal life support (ECLS) option focused primarily on removing carbon dioxide rather than supplying oxygen (Hanks et al., 2022). Both procedures involve vascular cannulation, but ECCO₂R utilizes smaller cannulas, requires lower blood flow, is more cost-effective, and is generally more accessible than ECMO (Cove et al., 2012).

3.7. Main Parts of ECCO2R

The main components of the extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO2R) system include: a drainage cannula placed in a large central vein, a pump, a membrane lung, and a return cannula (Cove et al., 2012).

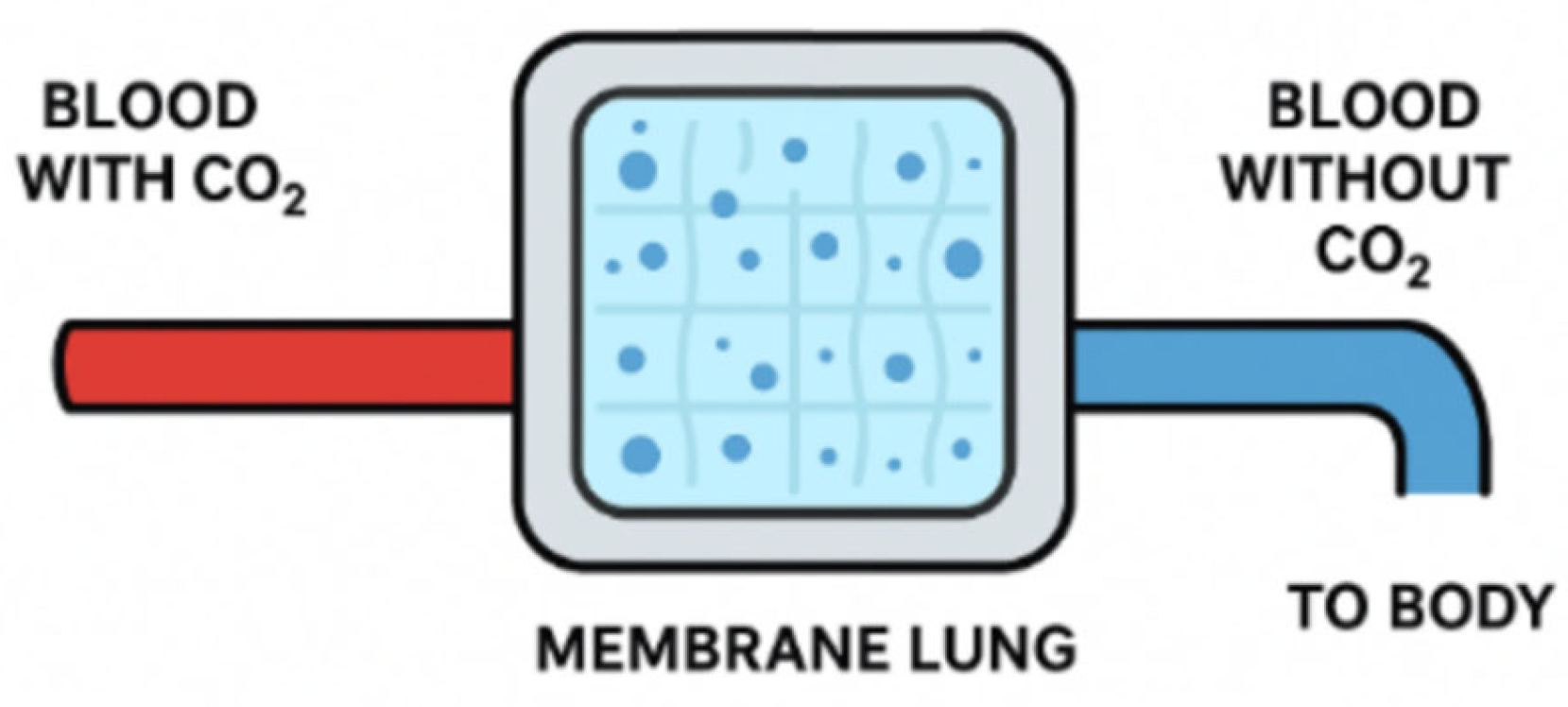

The membrane lung, also known as membrane oxygenator, has been a revolutionary addition to ECLS. Initially, gas exchange methods exposed blood directly to air through bubbling or rotating cylinders, causing cell damage, protein denaturation, and activation of inflammatory and coagulation pathways. Because of this, devices that allow direct gas exchange between blood and air can only be used for a few hours before severe complications arise. The idea of adding an intermediary, the membrane lung, arose after observing cellophane tubes in dialysis machines.

The membrane lung was initially coiled and contained fabric with an irregular surface to increase the surface area. These coiled membranes were later replaced by hollow fiber membranes made of microporous polypropylene, which enabled efficient gas exchange but led to plasma leakage. To address this issue, modern membranes, measuring between 1 m² and 3 m², are now made from poly(4-methyl-1-pentene). This material not only reduces plasma leakage but also improves gas exchange and biocompatibility. Gas exchange efficiency has been improved by incorporating fibers arranged in a complex mesh, allowing blood to flow perpendicularly to the fibers. This reduces the diffusion pathway length, enhancing mass transfer. Additionally, biocompatibility has been further enhanced by covalently binding heparin to the membrane surface.

Figure 1.

Basic Principle of a Membrane Lung.

Figure 1.

Basic Principle of a Membrane Lung.

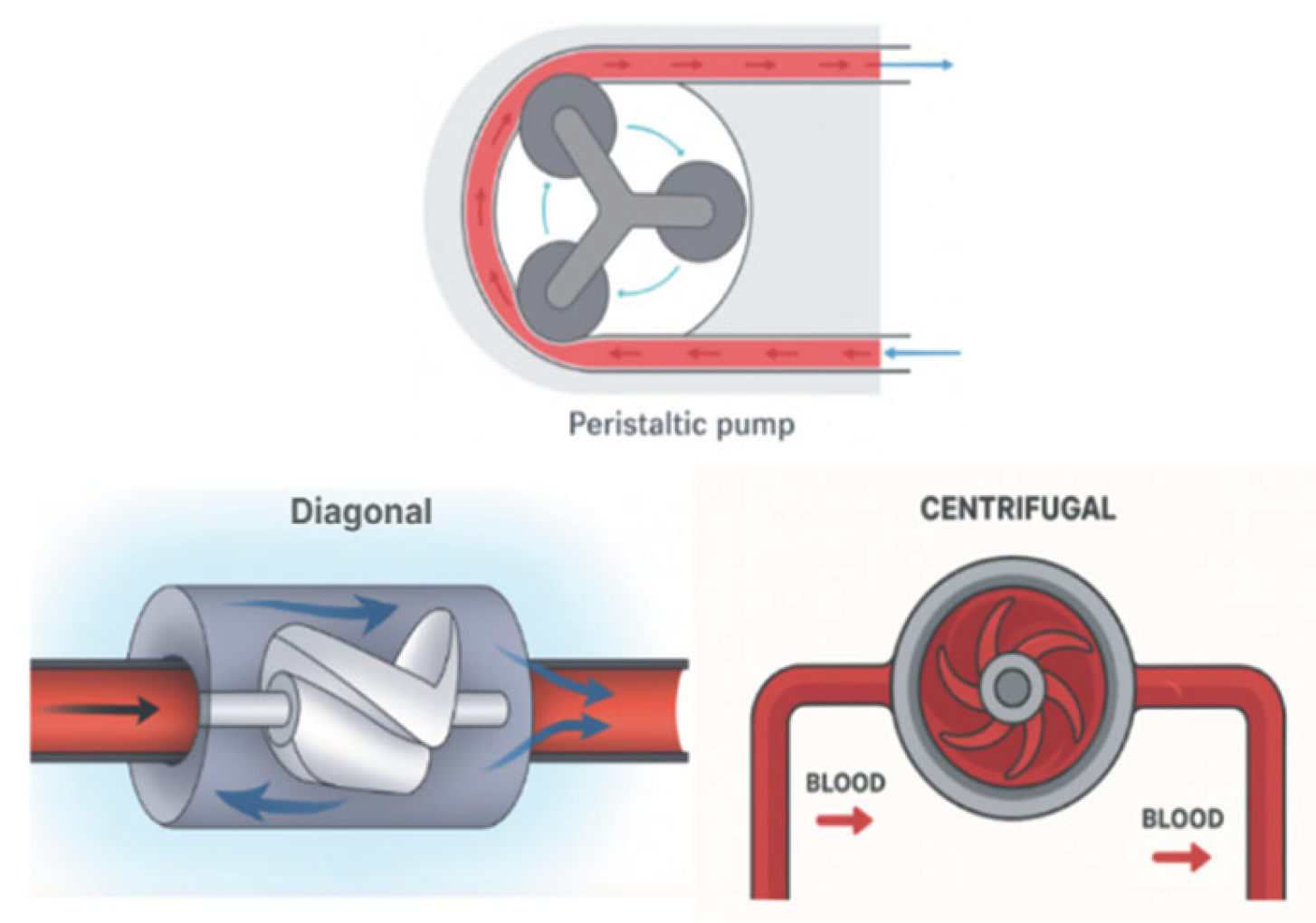

In ECCO2R, pumps are used to drive blood through the system. Not all ECCO₂R systems require a pump, given that patients with sufficient blood pressure can undergo arteriovenous (AV) CO₂ removal without one. However, venovenous (VV) CO₂ removal needs the use of a mechanical pump to drive blood flow. Early pumps, like roller or peristaltic pumps, were cost-effective but caused blood damage due to excessive compression and heating. The rotary pumps, such as centrifugal and diagonal flow pumps, reduced blood trauma by improving blood flow mechanics. Centrifugal pumps create a suction vortex to expel blood with high pressure but low flow, while diagonal flow pumps combine axial and radial geometries, achieving both high pressure and flow. However, these pumps still face challenges with waste accumulation and blood clotting due to the exposure of blood to the rotating drive shafts and impellers.

To address these challenges, newer centrifugal pump designs incorporate biocompatible materials for bearings, and the most advanced models now use magnetic fields to suspend impellers, eliminating the need for mechanical bearings and drive shafts. This innovation reduces mechanical failures, minimizes blood trauma, and decreases the heating of blood components, leading to more efficient and safer CO₂ removal systems (Arens et al., 2024).

Figure 2.

Pressure Generating Pumps and Volume Displacement Pumps.

Figure 2.

Pressure Generating Pumps and Volume Displacement Pumps.

Cannulas are used to drive the blood from and into the patient. In the first clinical trials of ECCO₂R, two cannulas were used and placed in the saphenous veins, located in the legs. One of these cannulas drained the patient’s blood and transported it to the filtration device, while the other cannula returned the blood with reduced CO₂ back into the body. The structure and placement of the cannulas have since changed. Instead of being inserted into the saphenous veins, they are now placed in the femoral or jugular veins due to their proximity to the heart. Additionally, the cannulas are reinforced with wire to provide rigidity and are coated with heparin, an anticoagulant, to prevent clot formation and reduce damage to red blood cells.

A more advanced type of cannula is the double-lumen cannula. Instead of using separate extraction and return cannulas, both processes occur within the same device. Blood is drawn through one side of the cannula and returned through the other. The double-lumen cannula is inserted through the right jugular vein and guided into the intrahepatic inferior vena cava using ultrasound. The dual-chamber design of the cannula minimizes accidental blood recirculation (Cove et al., 2012).

3.8. ECCO2R Challenges

In general terms, positive pressure ventilation can lead to complications such as oxygen toxicity, pulmonary overdistension, and ventilator-associated pneumonia, but ECCO2R comes with its own complications and challenges. These can be categorized into patient-related, mechanical system-related, and circuit and catheter-related challenges. Patient-related challenges include bleeding associated with anticoagulation and vascular access, hemolysis, and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Mechanical challenges involve clot formation, air embolism, and failures in the pump, membrane oxygenator, and heat exchanger. Finally, circuit and catheter-related challenges include aneurysms, hematomas, thrombosis, vascular injuries, vascular occlusions, bleeding at the cannula insertion site, infections, and cannula displacement.

Additionally, extracorporeal arteriovenous carbon dioxide removal has been associated with complications such as pseudoaneurysm formation, ischemia in distal limbs, and compartment syndrome. Although these complications can also occur when using the venovenous extracorporeal removal method, they are less frequent (Titus et al., 2022).