Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

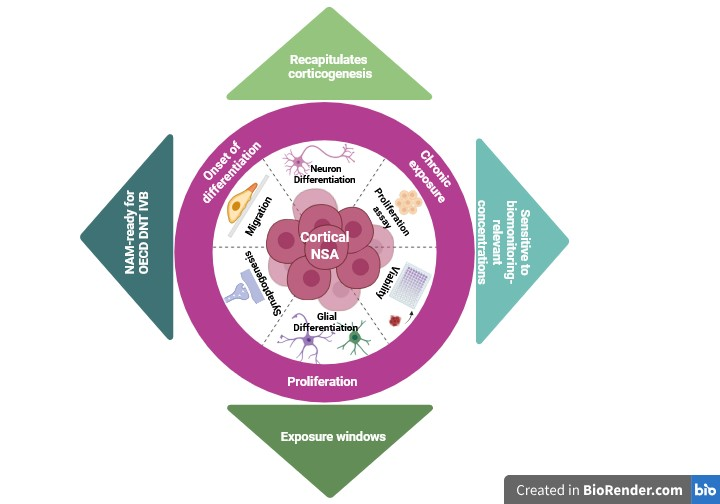

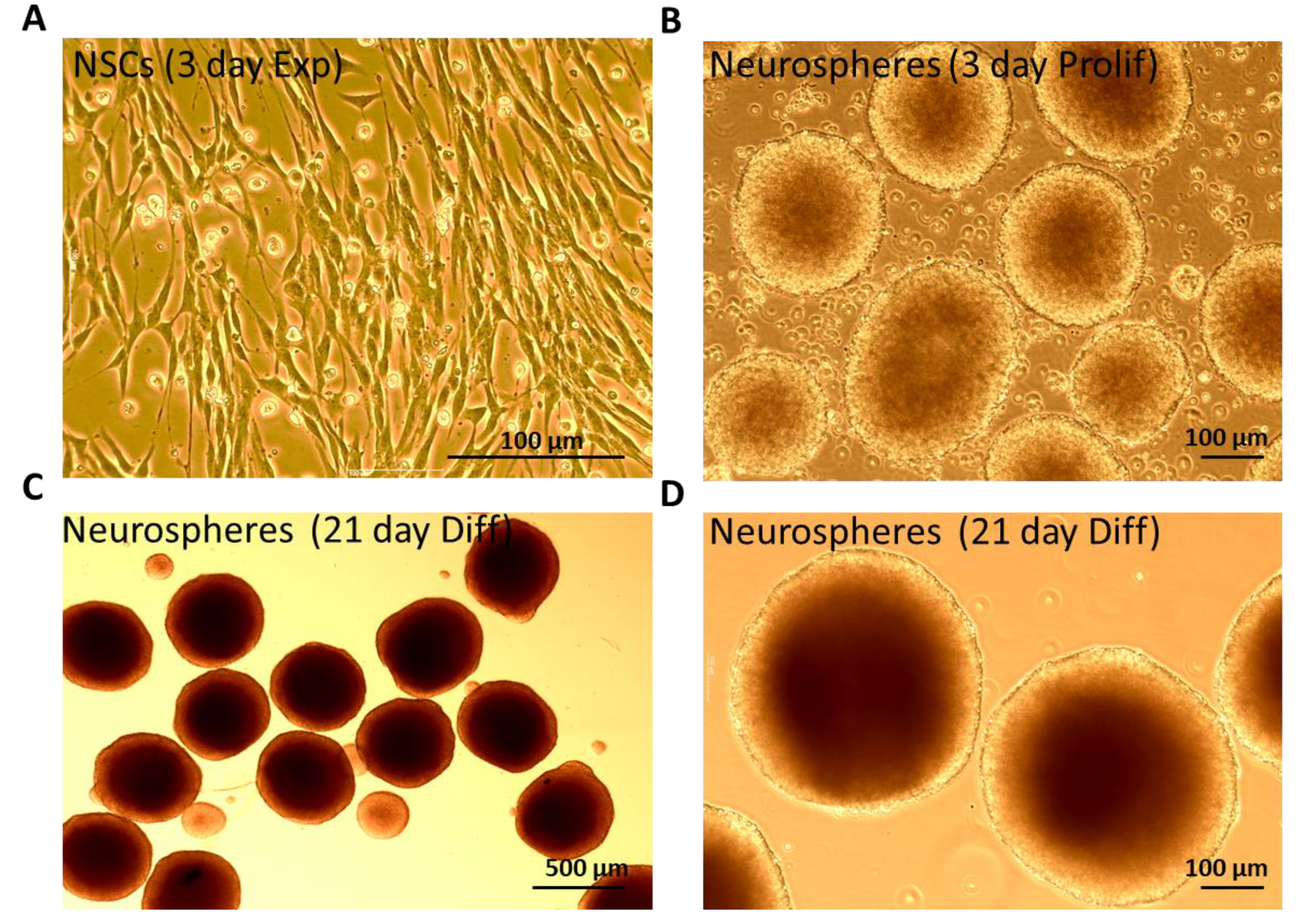

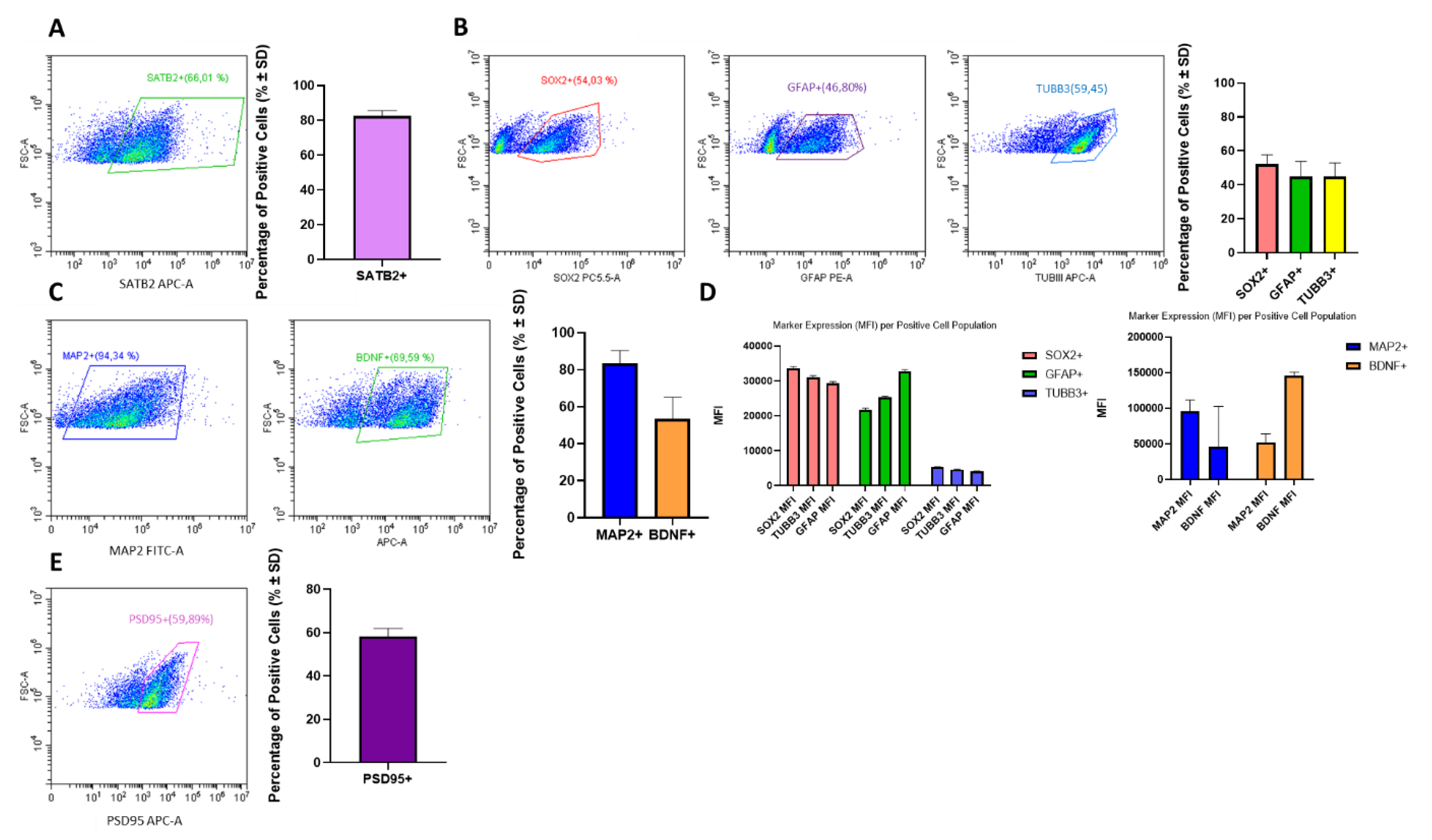

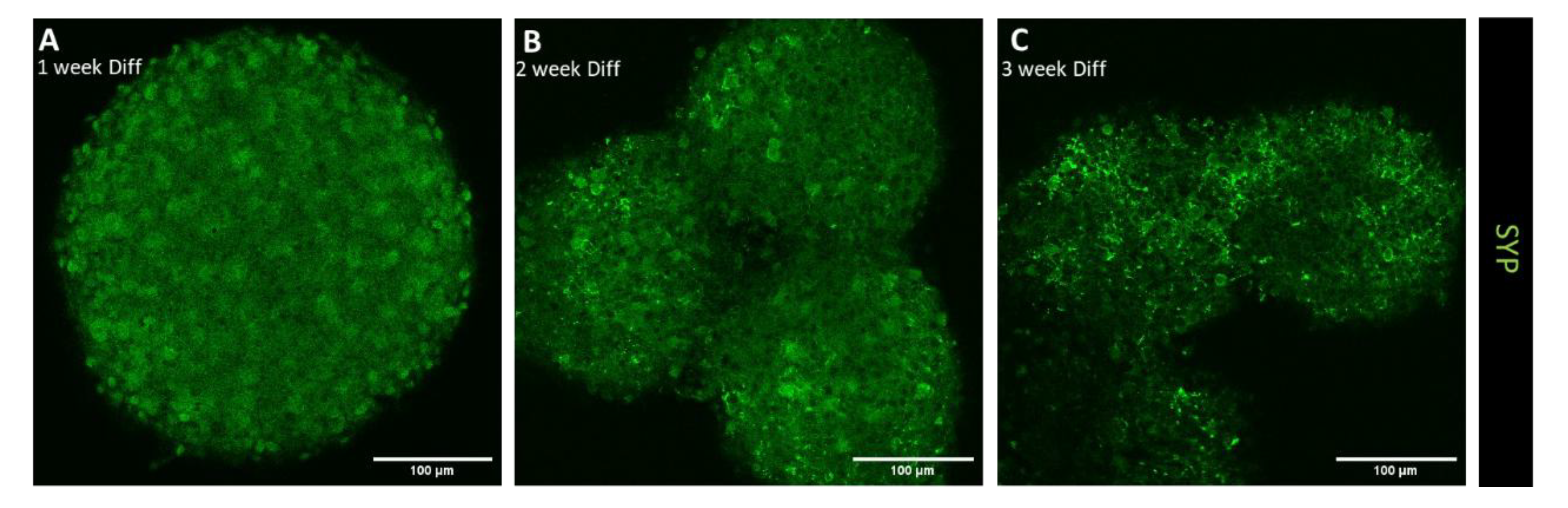

Background: Developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) arises from disruption of key neurodevelopmental processes, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and synaptogenesis. Traditional in vivo testing is costly and lacks mechanistic resolution, prompting OECD and EFSA to endorse new approach methodologies (NAMs) such as the neurosphere assay (NSA). Methods: We validated a mouse-derived NSA over a three-week differentiation period using multiparametric endpoints—proliferation, neuronal and glial differentiation, radial migration, synaptogenesis, and astrocytic maturation. Baseline characterization was established by flow cytometry, confocal immunofluorescence, and qPCR. Toxicants were applied under two exposure scenarios: (i) chronically during the 7-day proliferation phase, and (ii) chronically after three days of proliferation and maintained throughout the three-week differentiation period. Chlorpyrifos (CPF) served as a DNT-positive reference, and a biomonitoring-relevant mixture of PFAS (PFOS, PFOA, PFUnDA, PFHxS) was designed from the French Esteban study. Results: Baseline analyses confirmed progressive neuronal and glial differentiation, synaptic maturation, and growth factor responsiveness. CPF induced biphasic effects: early enlargement, subsequent growth arrest, migration impairment, overt cytotoxicity at 250 µM, and GFAP downregulation. PFAS mixtures produced modest viability effects but consistently reduced migration and downregulated GFAP and SYP at low-nM levels, consistent with epidemiological and experimental evidence linking PFAS to neurodevelopmental disorders. Migration emerged as a more sensitive endpoint than bulk viability, revealing functional impairments below overt toxicity thresholds. Conclusions: The NSA faithfully recapitulates corticogenesis and detects toxicant-specific liabilities, with CPF impairing astrocytic maturation and PFAS mixtures disrupting astrocytic and synaptic programs at environmentally relevant levels. By integrating complementary endpoints under chronic exposure conditions across proliferation and differentiation, this study advances the NSA as a mechanistic, human-relevant, and regulatory-ready NAM for DNT assessment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Neurosphere Culture and Differentiation into 3D Mixed Population of Neurons and Glia

2.2. Repeated Dose Treatment with CPF and PFAS Mixture

2.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.4. XTT Cytotoxicity Assay for Cell Viability

2.5. Growth Factor–Dependent Proliferation Assay

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Microscopy

2.7. Migration Assay

2.8. Measurement of Neurosphere Size During Differentiation

2.9. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Analyses

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Mouse- Derived NSCs Differentiated Towards Neurons and Glia as 3D Neurospheres

3.1.1. Model Characterization by Cytometry

3.1.2. Confocal Immunofluorescence Analysis of Differentiation, Migration, and Synaptic Maturation

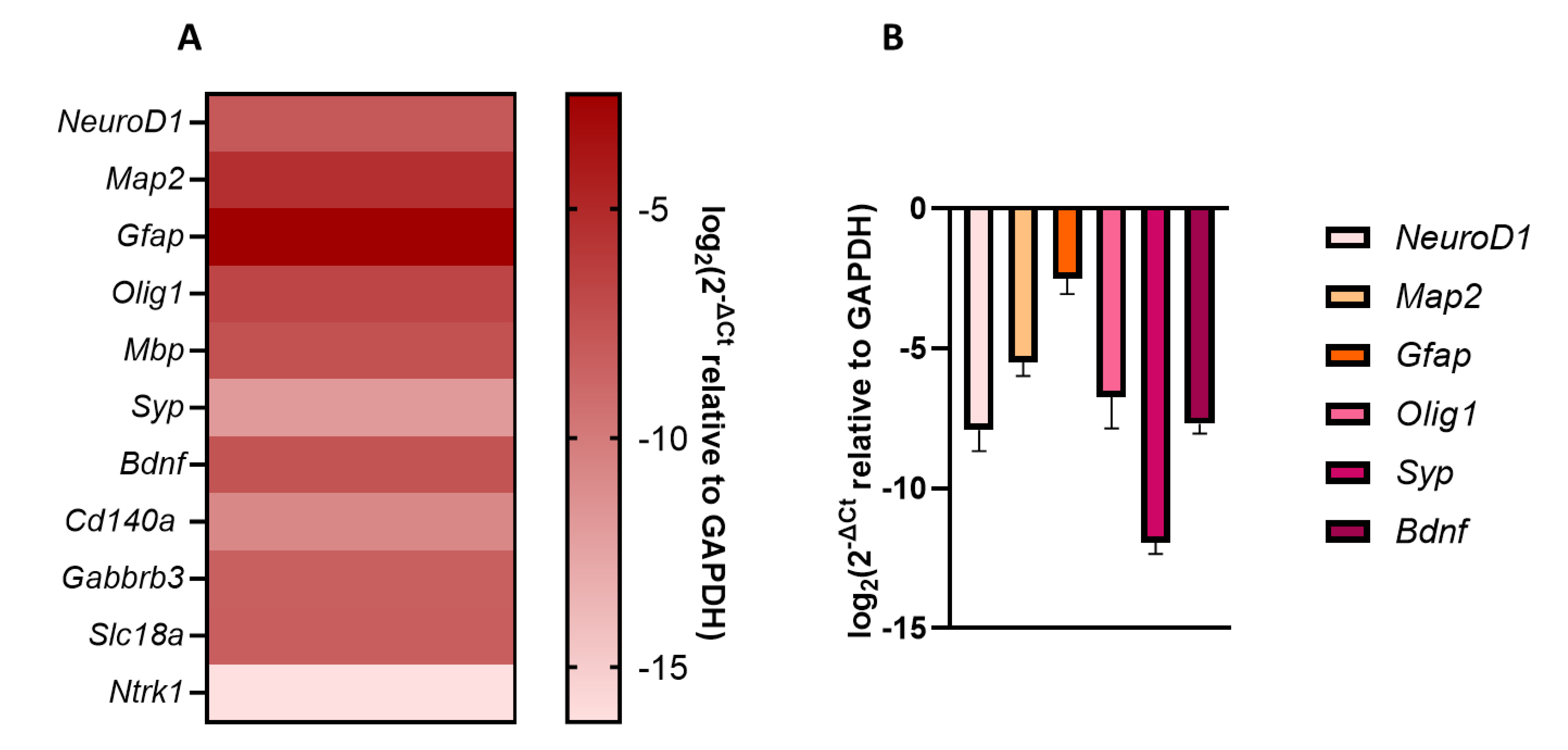

3.1.3. Basal Transcriptional Profiling of Neurodevelopmental Genes

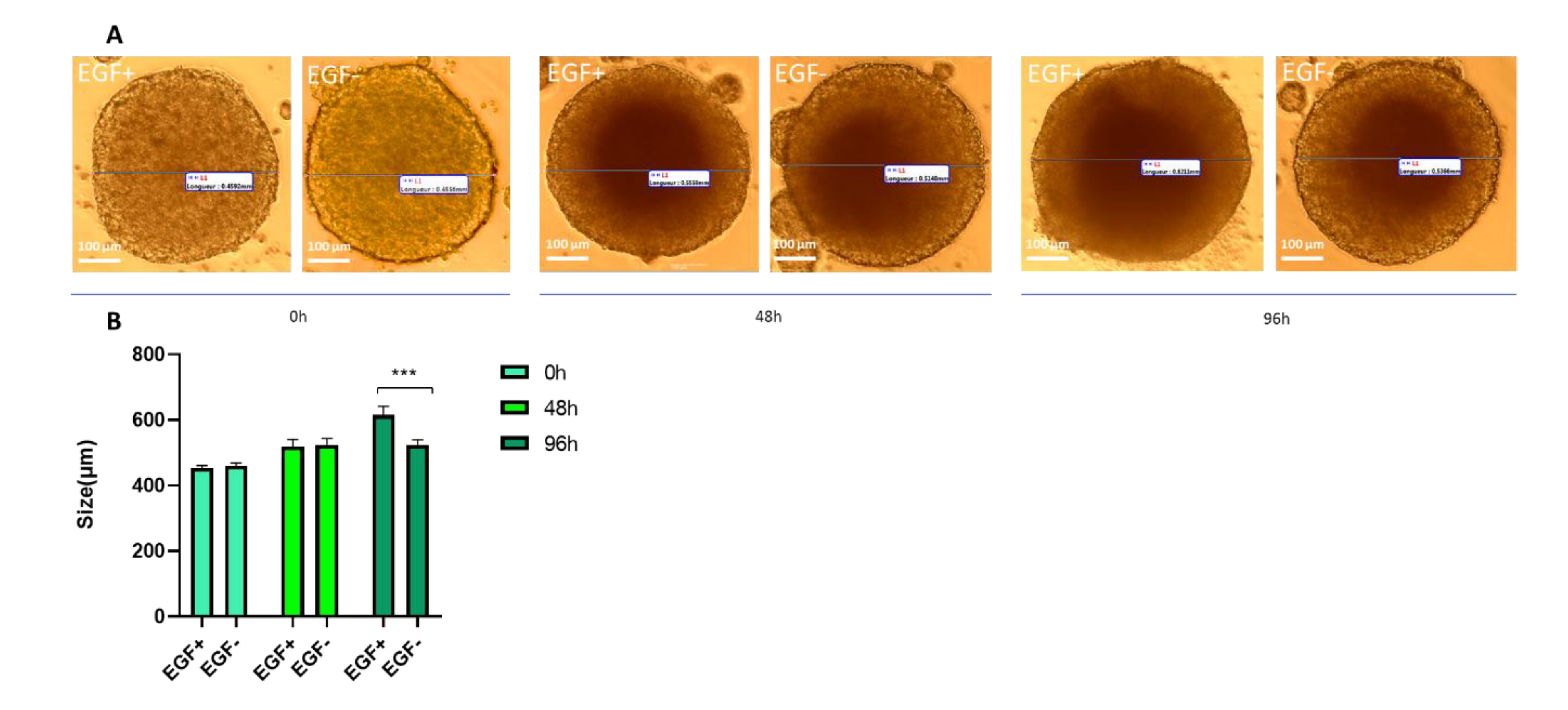

3.1.4. Proliferation Assay Under Growth Factor Conditions

3.2. Effects of CPF and PFAS on 3D Neuronal/Glial Culture

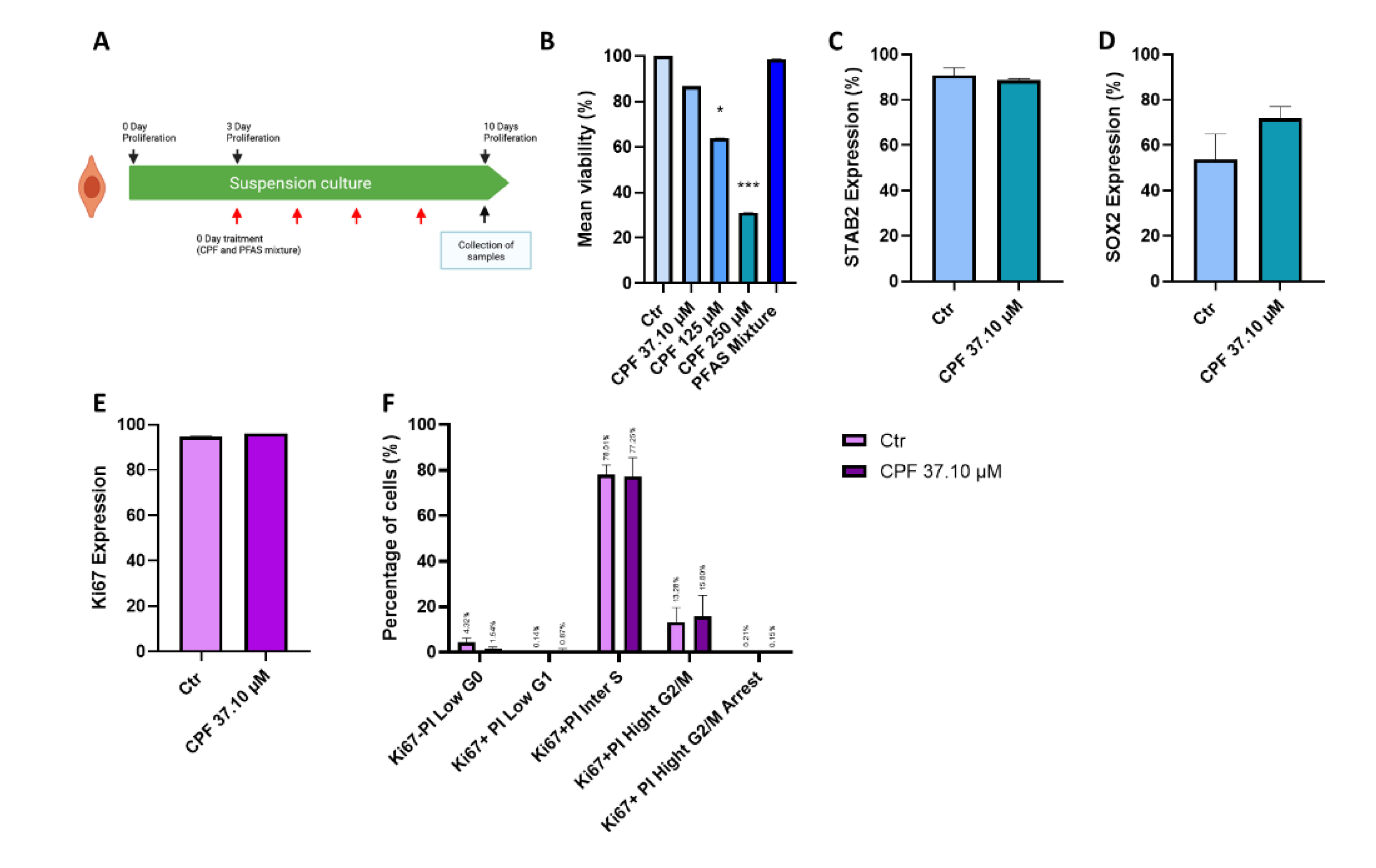

3.2.1. Effects of CPF and PFAS on Proliferative Neurospheres

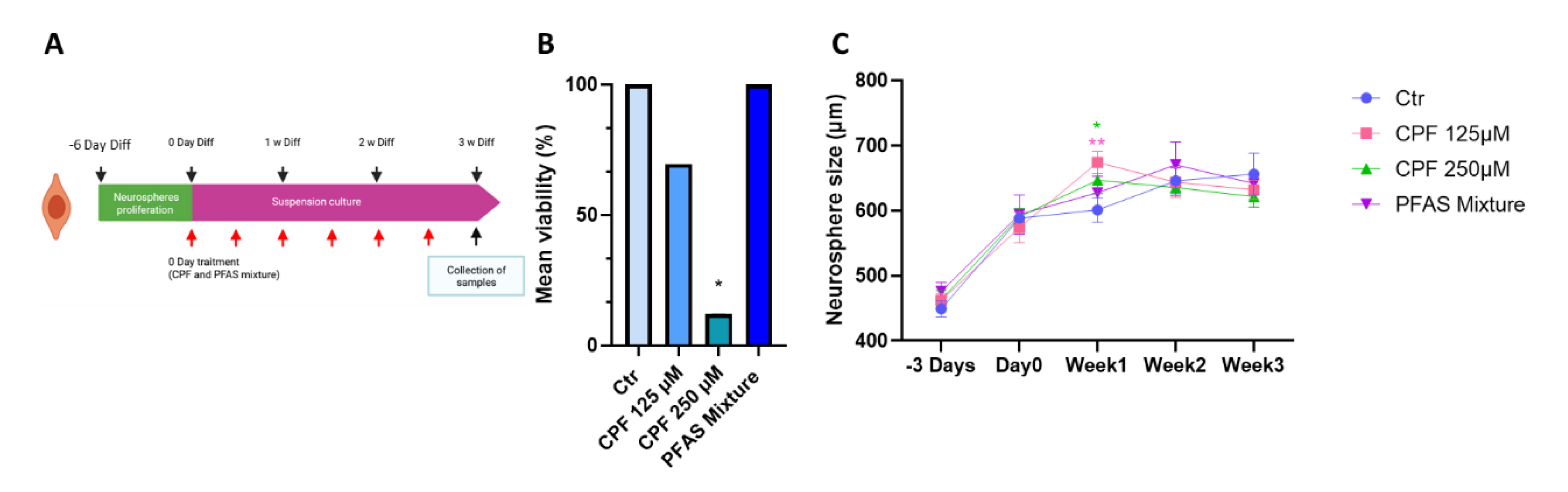

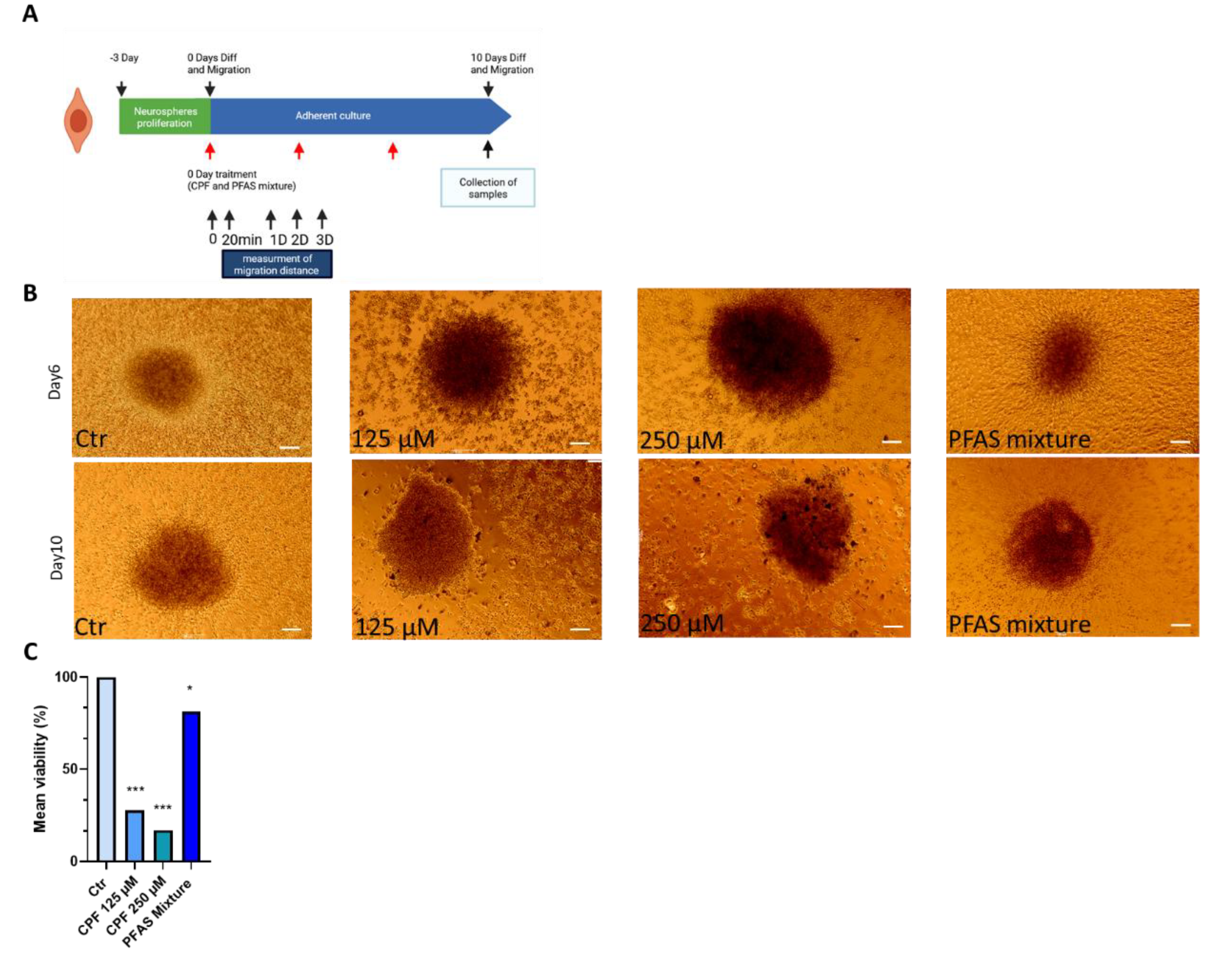

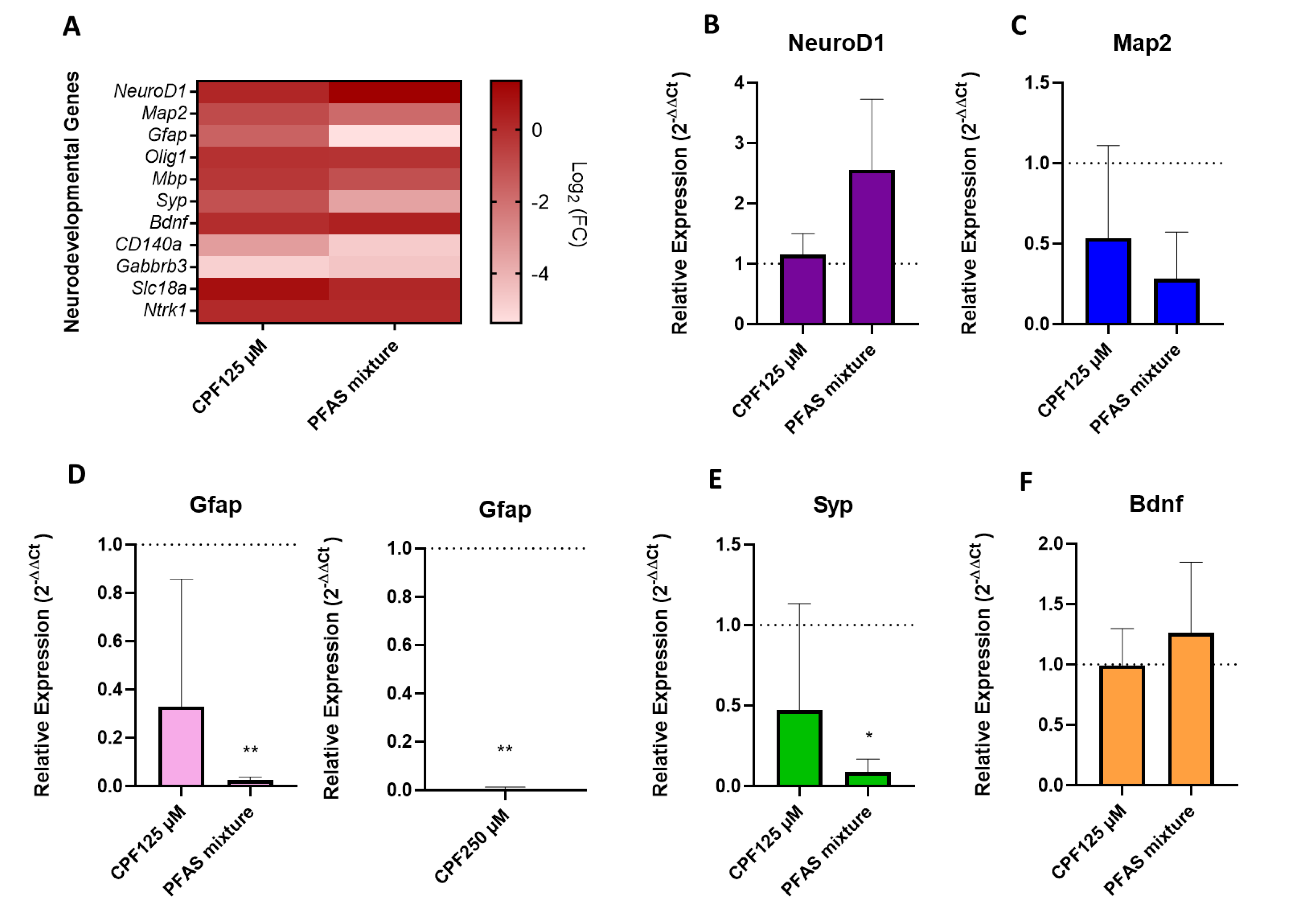

3.2.2. Effects of CPF and PFAS on Differentiated Neurospheres3.2.2.1. Effects of CPF and PFAS Mixture on Neurosphere Viability and Growth During Differentiation

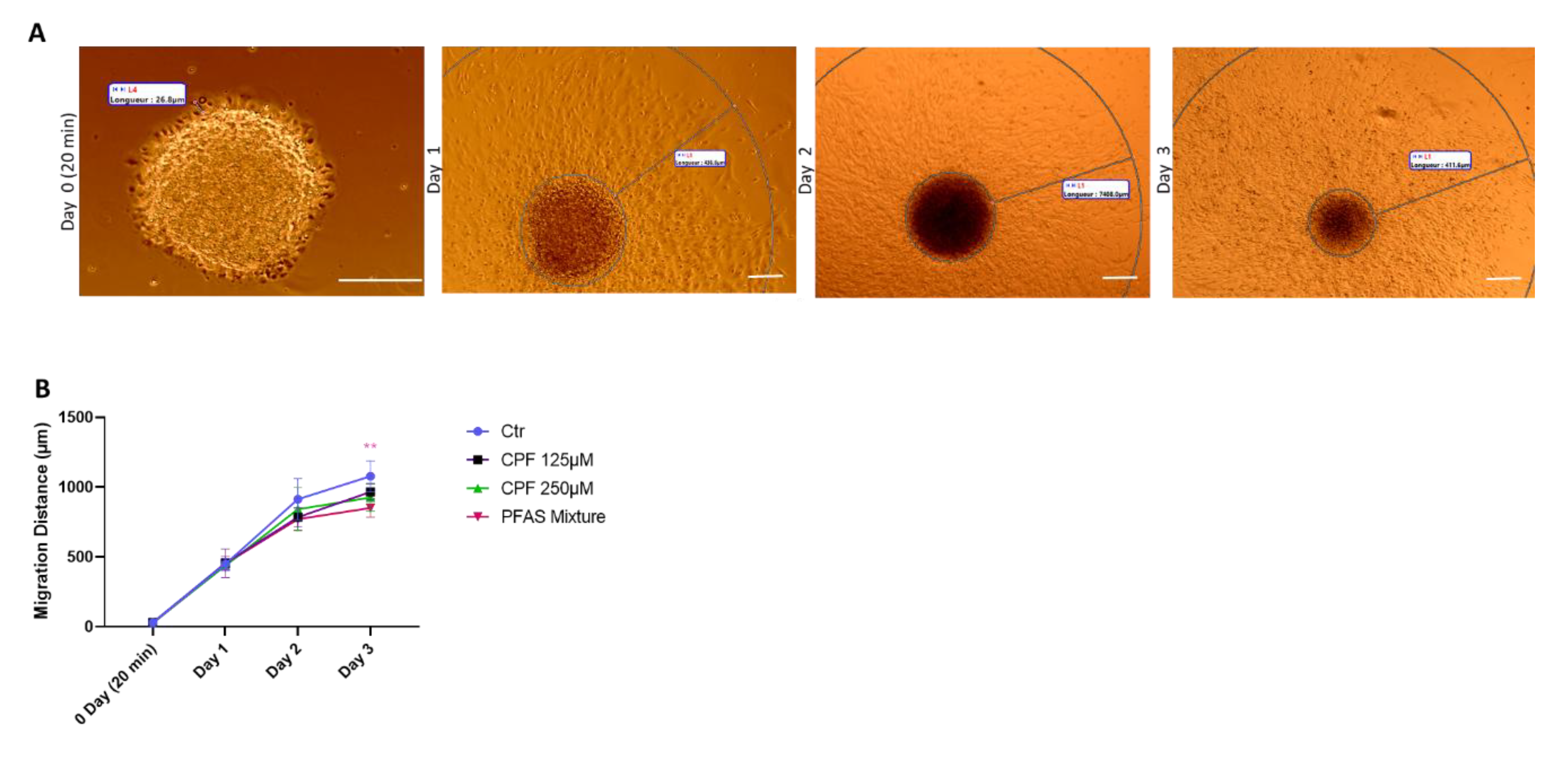

3.2.2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Early Radial Migration Dynamic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| CPF | Chlorpyrifos |

| Dlg4 / PSD95 | Discs Large MAGUK Scaffold Protein 4 / Postsynaptic Density Protein 95 |

| DMEM/F12 | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DNT | Developmental Neurotoxicity |

| DNT IVB | Developmental Neurotoxicity In Vitro Battery |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| IC20 | 20% Inhibitory Concentration |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 |

| Mbp | Myelin Basic Protein |

| NAM | New Approach Methodology |

| Neurod1 | Neurogenic Differentiation 1 |

| NSA | Neurosphere Assay |

| NSC | Neural Stem Cell |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| Olig1 | Oligodendrocyte Transcription Factor 1 |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| PFAS | Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexane Sulfonic Acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic Acid |

| PFUnDA | Perfluoroundecanoic Acid |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SYP | Synaptophysin |

| SATB2 | Special AT-Rich Sequence-Binding Protein 2 |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SOX2 | SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2 |

| Tubb3 / βIII-tubulin | Class III Beta-Tubulin |

| XTT | 2,3-Bis(2-Methoxy-4-Nitro-5-Sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium-5-Carboxanilide Sodium Salt |

References

- Smirnova, L. Developmental Neurotoxicity – Challenges in the 21st Century and In Vitro Opportunities. ALTEX 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, R.; Crofton, K.M. Developmental Neurotoxicity Guideline Study: Issues with Methodology, Evaluation and Regulation*: DNT Guideline Study. Congenital Anomalies 2012, 52, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofton, K.M.; Bassan, A.; Behl, M.; Chushak, Y.G.; Fritsche, E.; Gearhart, J.M.; Marty, M.S.; Mumtaz, M.; Pavan, M.; Ruiz, P.; et al. Current Status and Future Directions for a Neurotoxicity Hazard Assessment Framework That Integrates in Silico Approaches. Computational Toxicology 2022, 22, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal-Price, A.; Lein, P.J.; Keil, K.P.; Sethi, S.; Shafer, T.; Barenys, M.; Fritsche, E.; Sachana, M.; Meek, M.E. (Bette) Developing and Applying the Adverse Outcome Pathway Concept for Understanding and Predicting Neurotoxicity. NeuroToxicology 2017, 59, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparella, M.; Bennekou, S.H.; Bal-Price, A. An Analysis of the Limitations and Uncertainties of in Vivo Developmental Neurotoxicity Testing and Assessment to Identify the Potential for Alternative Approaches. Reprod Toxicol 2020, 96, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, E.; Crofton, K.M.; Hernandez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Leist, M.; Bal-Price, A.; Reaves, E.; Wilks, M.F.; Terron, A.; Solecki, R.; et al. OECD/EFSA Workshop on Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT): The Use of Non-Animal Test Methods for Regulatory Purposes. ALTEX 2017, 34, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Price, A. Advancing the Science of Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT): Testing for Better Safety Evaluation. ALTEX 2012, 29, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Price, A.K.; Hogberg, H.T.; Buzanska, L.; Lenas, P.; van Vliet, E.; Hartung, T. In Vitro Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) Testing: Relevant Models and Endpoints. NeuroToxicology 2010, 31, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Price, A.; Crofton, K.M.; Sachana, M.; Shafer, T.J.; Behl, M.; Forsby, A.; Hargreaves, A.; Landesmann, B.; Lein, P.J.; Louisse, J.; et al. Putative Adverse Outcome Pathways Relevant to Neurotoxicity. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2015, 45, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel), E.P. on C. in the F.C. (EFSA C.; Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L. (Ron); Leblanc, J.-C.; et al. Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Food. EFSA Journal 2020, 18, e06223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain (CONTAM), E.P. on C. in the F.; Knutsen, H.K.; Alexander, J.; Barregård, L.; Bignami, M.; Brüschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; et al. Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid and Perfluorooctanoic Acid in Food. EFSA Journal 2018, 16, e05194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjosthusmann, S.; Blum, J.; Bartmann, K.; Dolde, X.; Holzer, A.; Stürzl, L.; Keßel, E.H.; Förster, N.; Dönmez, A.; Klose, J.; et al. Establishment of an a Priori Protocol for the Implementation and Interpretation of an In-vitro Testing Battery for the Assessment of Developmental Neurotoxicity. EFS3 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, J.; Barenys, M.; Gassmann, K.; Fritsche, E. Comparative Human and Rat “Neurosphere Assay” for Developmental Neurotoxicity Testing. CP Toxicology 2014, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, K.; Bartmann, K.; Hartmann, J.; Kapr, J.; Klose, J.; Kuchovská, E.; Pahl, M.; Schlüppmann, K.; Zühr, E.; Fritsche, E. Scientific Validation of Human Neurosphere Assays for Developmental Neurotoxicity Evaluation. Front Toxicol 2022, 4, 816370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofton, K.M.; Mundy, W.R. External Scientific Report on the Interpretation of Data from the Developmental Neurotoxicity In Vitro Testing Assays for Use in Integrated Approaches for Testing and Assessment. EFS3 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, J.; Dolde, X.; Krebs, A.; Pinto-Gil, K.; Pastor, M.; Behl, M.; Waldmann, T.; Leist, M. Combination of Multiple Neural Crest Migration Assays to Identify Environmental Toxicants from a Proof-of-Concept Chemical Library. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91, 3613–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallocca, G.; Grinberg, M.; Henry, M.; Frickey, T.; Hengstler, J.G.; Waldmann, T.; Sachinidis, A.; Rahnenführer, J.; Leist, M. Identification of Transcriptome Signatures and Biomarkers Specific for Potential Developmental Toxicants Inhibiting Human Neural Crest Cell Migration. Arch Toxicol 2016, 90, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kumar T, P.; Joshee, S.; Kirschstein, T.; Subburaju, S.; Khalili, J.S.; Kloepper, J.; Du, C.; Elkhal, A.; Szabó, G.; et al. Endothelial Cell-Derived GABA Signaling Modulates Neuronal Migration and Postnatal Behavior. Cell Res 2018, 28, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Patterson, B.; Kang, Y.-J.; Govindaiah, G.; Roselaar, N.; Cakir, B.; Kim, K.-Y.; Lombroso, A.P.; Hwang, S.-M.; et al. Fusion of Regionally Specified hPSC-Derived Organoids Models Human Brain Development and Interneuron Migration. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 383–398.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, J. A High-Throughput Approach to Identify Specific Neurotoxicants / Developmental Toxicants in Human Neuronal Cell Function Assays. ALTEX 2018, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, B.; Lee, G.; Balmer, N.V.; Meganathan, K.; Sachinidis, A.; Studer, L.; Leist, M. Evaluation of Developmental Toxicants and Signaling Pathways in a Functional Test Based on the Migration of Human Neural Crest Cells. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistollato, F.; de Gyves, E.M.; Carpi, D.; Bopp, S.K.; Nunes, C.; Worth, A.; Bal-Price, A. Assessment of Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chemical Mixtures Using an Adverse Outcome Pathway Concept. Environ Health 2020, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Kubo, Y.; Yamazaki, D.; Sekino, Y.; Kanda, Y. Chlorpyrifos Inhibits Neural Induction via Mfn1-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistollato, F.; Carpi, D.; Mendoza-de Gyves, E.; Paini, A.; Bopp, S.K.; Worth, A.; Bal-Price, A. Combining in Vitro Assays and Mathematical Modelling to Study Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chemical Mixtures. Reproductive Toxicology 2021, 105, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzanska, L.; Sypecka, J.; Nerini-Molteni, S.; Compagnoni, A.; Hogberg, H.T.; del Torchio, R.; Domanska-Janik, K.; Zimmer, J.; Coecke, S. A Human Stem Cell-Based Model for Identifying Adverse Effects of Organic and Inorganic Chemicals on the Developing Nervous System. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 2591–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, P.; Deng, Y.; Dai, H.; Tian, J.; Wu, G.; Zhao, L. Chlorpyrifos-Induced Dysregulation of Synaptic Plasticity in Rat Hippocampal Neurons. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 2023, 58, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.J.; Seidler, F.J.; Slotkin, T.A. Developmental Neurotoxicity of Chlorpyrifos: Targeting Glial Cells. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2005, 19, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.-P.; Zhao, L.-L. Effect of Chlorpyrifos and Lipopolysaccharide on Primary Cultured Astrocytes. dtbh 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, L.; Rosca, A.; Oniga, A.; Zambrano, A.; Ramos, J.J.; González, M.C.; Liste, I.; Motas, M. Effects of Chlorpyrifos on Cell Death and Cellular Phenotypic Specification of Human Neural Stem Cells. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 683, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Consiglio, E.; Pistollato, F.; Mendoza-De Gyves, E.; Bal-Price, A.; Testai, E. Integrating Biokinetics and in Vitro Studies to Evaluate Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chlorpyrifos in Human iPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cells Undergoing Differentiation towards Neuronal and Glial Cells. Reprod Toxicol 2020, 98, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starnes, H.M.; Rock, K.D.; Jackson, T.W.; Belcher, S.M. A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Impacts of Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances on the Brain and Behavior. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 881584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharal, B.; Ruchitha, C.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, R.; Rachamalla, M.; Niyogi, S.; Naidu, R.; Kaundal, R.K. Neurotoxicity of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Evidence and Future Directions. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 955, 176941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.W.; Mair, D.C.; Lange, C.C.; Harrington, L.M.; Church, T.R.; Goldberg, C.L.; Herron, R.M.; Hanna, H.; Nobiletti, J.B.; Rios, J.A.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in American Red Cross Adult Blood Donors, 2000–2015. Environmental Research 2017, 157, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddalon, A.; Pierzchalski, A.; Kretschmer, T.; Bauer, M.; Zenclussen, A.C.; Marinovich, M.; Corsini, E.; Herberth, G. Mixtures of Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Reduce the in Vitro Activation of Human T Cells and Basophils. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Qin, S.; Zeng, H.; Chou, W.; Oudin, A.; Kanninen, K.M.; Jalava, P.; Dong, G.; Zeng, X. Adverse Outcome Pathway for the Neurotoxicity of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Systematic Review. Eco-Environment & Health 2024, 3, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Yang, Q.; Wu, L.; He, Y.; Zeng, N.; Wang, Z. Neurotoxic Effects of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Mixture Exposure in Mice: Accumulations in Brain and Associated Changes of Behaviors, Metabolome, and Transcriptome. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 489, 137699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé publique France Imprégnation de la population française par les composés perfluorés. Programme national de biosurveillance, Esteban 2014–2016; Santé publique France: Saint-Maurice, 2019; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A.M.; Bouwman, L.M.S.; van Kleef, R.G.D.M.; Hendriks, H.S.; Legler, J.; Westerink, R.H.S. Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) Acutely Affect Human α1β2γ2L GABAA Receptor and Spontaneous Neuronal Network Function in Vitro. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.M.; Wijnolts, F.M.J.; de Groot, A.; Westerink, R.H.S. Applicability of hiPSC-Derived Neuronal Cocultures and Rodent Primary Cortical Cultures for In Vitro Seizure Liability Assessment. Toxicological Sciences 2020, 178, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamies, D.; Wiersma, D.; Katt, M.E.; Zhao, L.; Burtscher, J.; Harris, G.; Smirnova, L.; Searson, P.C.; Hartung, T.; Hogberg, H.T. Human IPSC 3D Brain Model as a Tool to Study Chemical-Induced Dopaminergic Neuronal Toxicity. Neurobiology of Disease 2022, 169, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Gorczyca, G.; Mendoza-deGyves, E.; Ponti, J.; Bogni, A.; Carpi, D.; Bal-Price, A.; Pistollato, F. Upscaling Biological Complexity to Boost Neuronal and Oligodendroglia Maturation and Improve in Vitro Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) Evaluation. Reproductive Toxicology 2022, 110, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Soto-Moreno, E.J.; Prakash, A.; Balboula, A.Z.; Qiao, H. Adverse PFAS Effects on Mouse Oocyte in Vitro Maturation Are Associated with Carbon-chain Length and Inclusion of a Sulfonate Group. Cell Proliferation 2023, 56, e13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.-J.; Hsieh, W.-S.; Chen, P.-C.; Liu, C.-Y. Prenatal Perfluoroalkyl Substance Exposure in Association with Global Histone Post-Translational Methylation in 2-Year-Old Children. Toxics 2024, 12, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haimbaugh, A.; Wu, C.-C.; Akemann, C.; Meyer, D.N.; Connell, M.; Abdi, M.; Khalaf, A.; Johnson, D.; Baker, T.R. Multi- and Transgenerational Effects of Developmental Exposure to Environmental Levels of PFAS and PFAS Mixture in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Toxics 2022, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadir, A.; Kandel, S.; Lewis, N.; Dauvergne, O.; Rosby, R.; Hossain, E. Epigenetic Consequences of In Utero PFAS Exposure: Implications for Development and Long-Term Health 2025.

- Pistollato, F.; de Gyves, E.M.; Carpi, D.; Bopp, S.K.; Nunes, C.; Worth, A.; Bal-Price, A. Assessment of Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chemical Mixtures Using an Adverse Outcome Pathway Concept. Environ Health 2020, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagare, A.; Gobin, M.; Monzel, A.S.; Schwamborn, J.C. A Robust Protocol for the Generation of Human Midbrain Organoids. STAR Protocols 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Zhang, S.; Xie, R.; Gao, B.; Campos, B.; Herold-Mende, C.; Lei, T. The Utility and Limitations of Neurosphere Assay, CD133 Immunophenotyping and Side Population Assay in Glioma Stem Cell Research. Brain Pathology 2010, 20, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible Ii, M.W.; Lovelace, M.D.; Mundell, H.D.; Pang, T.W.R.; Chan-Ling, T. BMPRII+ Neural Precursor Cells Isolated and Characterized from Organotypic Neurospheres: An in Vitro Model of Human Fetal Spinal Cord Development. Neural Regen Res 2024, 19, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracaro, L.; Hochuli, A.H.D.; Selenko, A.H.; Capriglione, L.G.A.; Brofman, P.R.S.; Senegaglia, A.C. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth Express Neuronal Markers before Differentiation Induction. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2023, 31, e20220489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Abbasi, F.; Koch, W.T.; Mostowski, H.; Varadkar, P.; Mccright, B. Evaluation of the Differentiation Status of Neural Stem Cells Based on Cell Morphology and the Expression of Notch and Sox2. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 1472–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lislien, M.; Kuchovska, E.; Kapr, J.; Duale, N.; Andersen, J.M.; Dirven, H.; Myhre, O.; Fritsche, E.; Koch, K.; Wojewodzic, M.W. Transcriptomic Characterization of 2D and 3D Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based in Vitro Models as New Approach Methodologies for Developmental Neurotoxicity Testing. Toxicology 2025, 510, 154000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsche, E.; Barenys, M.; Hogberg, H.T. Editorial: Methods and Protocols in Neurotoxicology. Front Toxicol 2022, 4, 1031667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Shaker, M.R.; Lee, E.; Lee, B.; Sun, W. NeuroCore Formation during Differentiation of Neurospheres of Mouse Embryonic Neural Stem Cells. Stem Cell Research 2020, 43, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, B.C.; Gong, T.; Wang, S.; Lim, L.W.; Wu, W.; Zhang, C. Decellularized Matrix Derived from Neural Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells Enhances the Neurogenic Potential of Dental Follicle Stem Cells. Journal of Endodontics 2017, 43, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamies, D. A Human Brain Microphysiological System Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Study Neurological Diseases and Toxicity. ALTEX 2017, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobolak, J.; Teglasi, A.; Bellak, T.; Janstova, Z.; Molnar, K.; Zana, M.; Bock, I.; Laszlo, L.; Dinnyes, A. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived 3D-Neurospheres Are Suitable for Neurotoxicity Screening. Cells 2020, 9, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Yang, Z. Developmental Origins of Human Cortical Oligodendrocytes and Astrocytes. Neurosci. Bull. 2022, 38, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Yang, Z. Developmental Origins of Human Cortical Oligodendrocytes and Astrocytes. Neurosci. Bull. 2022, 38, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Yue, T.; Ma, Z.; Wu, F.; Gow, A.; Lu, Q.R. Myelinogenesis and Axonal Recognition by Oligodendrocytes in Brain Are Uncoupled in Olig1 -Null Mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, K.L.; Fancy, S.P.J.; Franklin, R.J.M.; Rowitch, D.H. Olig Gene Function in CNS Development and Disease. Glia 2006, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Consiglio, E.; Pistollato, F.; Mendoza-De Gyves, E.; Bal-Price, A.; Testai, E. Integrating Biokinetics and in Vitro Studies to Evaluate Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chlorpyrifos in Human iPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cells Undergoing Differentiation towards Neuronal and Glial Cells. Reprod Toxicol 2020, 98, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundy, W.R.; Crofton, K.M. Recommended DNT Reference Chemical Test Set For In Vitro Assay Development*. EFS3 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, A.; Avci, H.X.; Ochalek, A.; Rösingh, L.N.; Molnár, K.; László, L.; Bellák, T.; Téglási, A.; Pesti, K.; Mike, A.; et al. Comparison of 2D and 3D Neural Induction Methods for the Generation of Neural Progenitor Cells from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Research 2017, 25, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-T.; Bendriem, R.M.; Wu, W.W.; Shen, R.-F. 3D Brain Organoids Derived from Pluripotent Stem Cells: Promising Experimental Models for Brain Development and Neurodegenerative Disorders. J Biomed Sci 2017, 24, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centeno, E.G.Z.; Cimarosti, H.; Bithell, A. 2D versus 3D Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cultures for Neurodegenerative Disease Modelling. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Sun, W. Isolation and Culture of Adult Neural Stem Cells from the Mouse Subcallosal Zone. J Vis Exp 2016, 54929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, C. Internationalization of Read-across as a Validated New Approach Method (NAM) for Regulatory Toxicology. ALTEX 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapping out Strategies to Further Develop Human-Relevant, New Approach Methodology (NAM)-Based Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) Testing. ALTEX 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hristozov, D.; Badetti, E.; Bigini, P.; Brunelli, A.; Dekkers, S.; Diomede, L.; Doak, S.H.; Fransman, W.; Gajewicz-Skretna, A.; Giubilato, E.; et al. Next Generation Risk Assessment Approaches for Advanced Nanomaterials: Current Status and Future Perspectives. NanoImpact 2024, 35, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymark, P.; Bakker, M.; Dekkers, S.; Franken, R.; Fransman, W.; García-Bilbao, A.; Greco, D.; Gulumian, M.; Hadrup, N.; Halappanavar, S.; et al. Toward Rigorous Materials Production: New Approach Methodologies Have Extensive Potential to Improve Current Safety Assessment Practices. Small 2020, 16, 1904749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, S.E.; Kamp, H.; Bennekou, S.H.; Bitsch, A.; Fisher, C.; Graepel, R.; Hengstler, J.G.; Herzler, M.; Knight, D.; Leist, M.; et al. Towards Grouping Concepts Based on New Approach Methodologies in Chemical Hazard Assessment: The Read-across Approach of the EU-ToxRisk Project. Arch Toxicol 2019, 93, 3643–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistollato, F.; Canovas-Jorda, D.; Zagoura, D.; Price, A. Protocol for the Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells into Mixed Cultures of Neurons and Glia for Neurotoxicity Testing. JoVE 2017, 55702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paşca, A.M.; Sloan, S.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Tian, Y.; Makinson, C.D.; Huber, N.; Kim, C.H.; Park, J.-Y.; O’Rourke, N.A.; Nguyen, K.D.; et al. Functional Cortical Neurons and Astrocytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells in 3D Culture. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middelkamp, H.H.T.; Verboven, A.H.A.; De Sá Vivas, A.G.; Schoenmaker, C.; Klein Gunnewiek, T.M.; Passier, R.; Albers, C.A.; ‘t Hoen, P.A.C.; Nadif Kasri, N.; van der Meer, A.D. Cell Type-Specific Changes in Transcriptomic Profiles of Endothelial Cells, iPSC-Derived Neurons and Astrocytes Cultured on Microfluidic Chips. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Koo, Y.; Russell, T.; Gay, E.; Li, Y.; Yun, Y. Three-Dimensional Brain-on-Chip Model Using Human iPSC-Derived GABAergic Neurons and Astrocytes: Butyrylcholinesterase Post-Treatment for Acute Malathion Exposure. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, S.; Dalley, A.; Kalita-de Croft, P.; Saunus, J.; Bassett, J.; Sadras, F.; Roberts-Thomson, S.; Monteith, G. Abstract P1-19-05: Establishment of a Human Neural Progenitor Cell Microenvironment Model to Investigate Signalling Events in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Brain Metastases in a High-Throughput Setting. Cancer Research 2019, 79, P1-19-05-P1-19–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dráberová, E.; Del Valle, L.; Gordon, J.; Marková, V.; Šmejkalová, B.; Bertrand, L.; De Chadarévian, J.-P.; Agamanolis, D.P.; Legido, A.; Khalili, K.; et al. Class III β-Tubulin Is Constitutively Coexpressed With Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Nestin in Midgestational Human Fetal Astrocytes: Implications for Phenotypic Identity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008, 67, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, C.; Xia, D.; Yuan, X. Leading Tip Drives Soma Translocation via Forward F-Actin Flow during Neuronal Migration. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 10885–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carulli, D.; Verhaagen, J. An Extracellular Perspective on CNS Maturation: Perineuronal Nets and the Control of Plasticity. IJMS 2021, 22, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.F.; Ghirnikar, R.S.; Lee, Y.L. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein: GFAP-Thirty-One Years (1969–2000). Neurochem Res 2000, 25, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, P.E.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Rapport, M.M. The Relationship of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein to the Shape, Motility, and Differentiation of Human Astrocytoma Cells. Experimental Cell Research 1982, 139, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, D.; López-Toledano, M.A.; Mason, I.; Cuevas, P.; Redondo, C.; Herranz, A.S.; Lobo, M.V.T.; Bazán, E. Developmental Expression of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Receptors in Neural Stem Cell Progeny. Modulation of Neuronal and Glial Lineages by Basic FGF Treatment. Neurological Research 2001, 23, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, B.A.; Weiss, S. Generation of Neurons and Astrocytes from Isolated Cells of the Adult Mammalian Central Nervous System. Science 1992, 255, 1707–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunç, B.S.; Toprak, F.; Toprak, S.F.; Sozer, S. In Vitro Investigation of Growth Factors Including MGF and IGF-1 in Neural Stem Cell Activation, Proliferation, and Migration. Brain Research 2021, 1759, 147366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.W.C.; Guillaud, L. The Role of Epidermal Growth Factor and Its Receptors in Mammalian CNS. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2004, 15, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tang, T.; Xie, Y. HDAC1 and HDAC2 Orchestrate Wnt Signaling to Regulate Neural Progenitor Transition during Brain Development. iScience 2024, 27, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.C.; Vong, K.I.; Kwan, K.M. Spatiotemporal Decline of BMP Signaling Activity in Neural Progenitors Mediates Fate Transition and Safeguards Neurogenesis. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 3616–3624.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telley, L.; Agirman, G.; Prados, J.; Amberg, N.; Fièvre, S.; Oberst, P.; Bartolini, G.; Vitali, I.; Cadilhac, C.; Hippenmeyer, S.; et al. Temporal Patterning of Apical Progenitors and Their Daughter Neurons in the Developing Neocortex. Science 2019, 364, eaav2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Miyata, T.; Konno, D.; Ueda, H.R.; Kasukawa, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Matsuzaki, F.; Kawaguchi, A. Cell-Cycle-Independent Transitions in Temporal Identity of Mammalian Neural Progenitor Cells. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, D.B.; Meredith, R.M. Environmental Toxicology: Sensitive Periods of Development and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. NeuroToxicology 2017, 58, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D.R.; Tang, S.; Miller, C.; Gagnon, D.; Shekh, K.; Alcaraz, A.J.G.; Janz, D.M.; Hecker, M. A Multi–Life Stage Comparison of Silver Nanoparticle Toxicity on the Early Development of Three Canadian Fish Species. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2021, 40, 3337–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.K.; Ijzerman, M.M.; Venier, C.; Prosser, R.S. Development of an Embryo Toxicity Test to Assess the Comparative Toxicity of Metal Exposure on Different Life Stages of Freshwater Gastropods. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2023, 42, 1791–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Cui, K.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Q. Identification of Sensitive Endpoints for the Assessment of Phthalates-Induced Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity: A Literature Mining Study. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2024, 188, 114686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidsen, N.; Rosenmai, A.K.; Lauschke, K.; Svingen, T.; Vinggaard, A.M. Developmental Effects of PFOS, PFOA and GenX in a 3D Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Differentiation Model. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.; Vats, A.; Lim, I.E.; Sapkota, B.; Abdelmoneim, A. Effects of Developmental Exposure to Individual and Combined PFAS on Development and Behavioral Stress Responses in Larval Zebrafish. Environmental Pollution 2024, 349, 123912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haimbaugh, A.; Wu, C.-C.; Akemann, C.; Meyer, D.N.; Connell, M.; Abdi, M.; Khalaf, A.; Johnson, D.; Baker, T.R. Multi- and Transgenerational Effects of Developmental Exposure to Environmental Levels of PFAS and PFAS Mixture in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Toxics 2022, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, J.; Dolde, X.; Krebs, A.; Pinto-Gil, K.; Pastor, M.; Behl, M.; Waldmann, T.; Leist, M. Combination of Multiple Neural Crest Migration Assays to Identify Environmental Toxicants from a Proof-of-Concept Chemical Library. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91, 3613–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Morita, T.; Mayanagi, T.; Tanokashira, D.; Yoshida, T.; Sakai, A.; Sobue, K. Detrimental Effects of Glucocorticoids on Neuronal Migration during Brain Development. Mol Psychiatry 2009, 14, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzetti, M.; Pathak, S.; Giordano, G.; Costa, L.G. Effect of Organophosphorus Insecticides and Their Metabolites on Astroglial Cell Proliferation. Toxicology 2005, 215, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, L. The Expression Change of GFAP and HMGB1 in Primary Cultured Astrocytes Exposed to Chlorpyrifos and Lipopolysaccharide. In Proceedings from the ICERP 2016; De Gruyter Open, 2017; pp. 161–169 ISBN 978-3-11-055904-0.

- Abu-Salah, A.; Cesur, M.F.; Anchan, A.; Ay, M.; Langley, M.R.; Shah, A.; Reina-Gonzalez, P.; Strazdins, R.; Çakır, T.; Sarkar, S. Comparative Proteomics Highlights That GenX Exposure Leads to Metabolic Defects and Inflammation in Astrocytes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 20525–20539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto-Rodrigues, M.C.; Monteiro-Neto, J.R.; Teglas, T.; Toborek, M.; Soares Quinete, N.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Adesse, D. Early-Life Exposure to PCBs and PFAS Exerts Negative Effects on the Developing Central Nervous System. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 485, 136832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, L.; Cristobal, J.R.; Karageorgiou, C.; Camdzic, M.; Aguilar, J.M.N.; Gokcumen, O.; Aga, D.S.; Atilla-Gokcumen, G.E. Investigating the Mechanism of Neurotoxic Effects of PFAS in Differentiated Neuronal Cells through Transcriptomics and Lipidomics Analysis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 4568–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.M.; Bouwman, L.M.S.; Van Kleef, R.G.D.M.; Hendriks, H.S.; Legler, J.; Westerink, R.H.S. Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) Acutely Affect Human α1β2γ2L GABAA Receptor and Spontaneous Neuronal Network Function in Vitro. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Bonilla, K.M.; Aga, D.S.; Lee, J.; König, M.; Qin, W.; Cristobal, J.R.; Atilla-Gokcumen, G.E.; Escher, B.I. Neurotoxic Effects of Mixtures of Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) at Environmental and Human Blood Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024; acs.est.4c06017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Shao, J. PFOS Elicits Cytotoxicity in Neuron Through Astrocyte-Derived CaMKII-DLG1 Signaling In Vitro Rat Hippocampal Model. Neurochem Res 2024, 49, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Shao, J. Evaluation of PFOS-Mediated Neurotoxicity in Rat Primary Neurons and Astrocytes Cultured Separately or in Co-Culture. Toxicology in Vitro 2017, 38, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan Ibrahim, W.N.; Tofighi, R.; Onishchenko, N.; Rebellato, P.; Bose, R.; Uhlén, P.; Ceccatelli, S. Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Induces Neuronal and Oligodendrocytic Differentiation in Neural Stem Cells and Alters the Expression of PPARγ in Vitro and in Vivo. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2013, 269, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ng, C. Absorption, Distribution, and Toxicity of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in the Brain: A Review. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2021, 23, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Liu, L.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Guo, Y. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Crossing the Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier: Their Occurrence in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 442, 130003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, L.; Ji, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, X.-M.; Wang, S.-L. Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Disrupts the Blood Brain Barrier through the Crosstalk between Endothelial Cells and Astrocytes in Mice. Environmental Pollution 2020, 256, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, M.H.; Robotti, E.; Ghignone, A.; Fabbris, A.; Brandi, J.; Cecconi, D.; Masini, M.A.; Dondero, F.; Marengo, E. Sensitive and Accurate Determination of 32 PFAS in Human Serum Using Online SPE-UHPLC-HRMS. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 485, 136780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colnot, T.; Dekant, W. Commentary: Cumulative Risk Assessment of Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids and Perfluoralkyl Sulfonic Acids: What Is the Scientific Support for Deriving Tolerable Exposures by Assembling 27 PFAS into 1 Common Assessment Group? Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 3127–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.J.; Roark, S.A.; Middleton, E.T. Considerations for Toxicity Experiments and Risk Assessments with PFAS Mixtures. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 2021, 17, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, R.; Cheli, V.T.; Santiago-González, D.A.; Rosenblum, S.L.; Wan, Q.; Paez, P.M. Impaired Postnatal Myelination in a Conditional Knockout Mouse for the Ferritin Heavy Chain in Oligodendroglial Cells. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 7609–7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J.L.; Jones, J.J.; Taniike, M.; Morell, P.; Suzuki, K.; Matsushima, G.K. Mature Oligodendrocyte Apoptosis Precedes IGF-1 Production and Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Accumulation and Differentiation during Demyelination/Remyelination. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 61, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faley, S.L.; Neal, E.H.; Wang, J.X.; Bosworth, A.M.; Weber, C.M.; Balotin, K.M.; Lippmann, E.S.; Bellan, L.M. iPSC-Derived Brain Endothelium Exhibits Stable, Long-Term Barrier Function in Perfused Hydrogel Scaffolds. Stem Cell Reports 2019, 12, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Is the Time Right for in Vitro Neurotoxicity Testing Using Human iPSC-Derived Neurons? ALTEX 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Consiglio, E.; Pistollato, F.; Mendoza-De Gyves, E.; Bal-Price, A.; Testai, E. Integrating Biokinetics and in Vitro Studies to Evaluate Developmental Neurotoxicity Induced by Chlorpyrifos in Human iPSC-Derived Neural Stem Cells Undergoing Differentiation towards Neuronal and Glial Cells. Reproductive Toxicology 2020, 98, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Cohen, J.D.; Pustovalova, O.; Lewis, L.; Shen, L. Profiling Secreted miRNA Biomarkers of Chemical-Induced Neurodegeneration in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons. Toxicological Sciences 2022, 186, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrichter, M.; Nimtz, L.; Tigges, J.; Kabiri, Y.; Schröter, F.; Royer-Pokora, B.; Hildebrandt, B.; Schmuck, M.; Epanchintsev, A.; Theiss, S.; et al. Comparative Performance Analysis of Human iPSC-Derived and Primary Neural Progenitor Cells (NPC) Grown as Neurospheres in Vitro. Stem Cell Research 2017, 25, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Acronym | Formula | Chain Length | Final conc. (µg/L) | Final conc. (nM) |

| Perfluoro-octane sulfonic acid | PFOS | C8HF17O3S | Long-chain (C8) | 2.22 | ~4.4 |

| Perfluorooctanoic acid | PFOA | C8HF15O2 | Long-chain (C8) | 1.56 | ~3.8 |

| Perfluoroundecanoic acid | PFUnDA | C11HF21O2 | Long-chain (C11) | 0.12 | ~0.23 |

| 1H,1H,2H, 2H-perfluorohexane sulfonic acid | 1H,1H,2H, PFHxS | C6H5F11O3S | Short-chain (C6) | 0.79 | ~2 |

| Gene name | Gene Symbol | Assay ID |

| Neurogenic differentiation 1 | Neurod1 | Mm01946604_s1 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 2 | Map2 | Mm00485231_m1 |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | Gfap | Mm01253033_m1 |

| Oligodendrocyte transcription factor 1 | Olig1 | Mm00497537_s1 |

| Myelin basic protein | Mbp | Mm01266402_m1 |

| Synaptophysin | Syp | Mm00436850_m1 |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | Bdnf | Mm04230607_s1 |

| PDGF receptor alpha (used as CD140a marker) | Pdgfra (Cd140a) | Mm00440701_m1 |

| GABA-A receptor subunit beta-3 | Gabrb3 | Mm00433473_m1 |

| Vesicular acetylcholine transporter | Slc18a3 | Mm00491465_s1 |

| Neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1 | Ntrk1 | Mm01219406_m1 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (reference) | Gapdh | Mm99999915_g1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).