1. Introduction

In the last decades, an ever-growing body of research has been establishing connections between language and its co-occurring bodily motion, mainly hand gestures but also, and increasingly, other visual modalities such as pose, facial expression, or gaze[

1]. Despite this progress, the correlations between multimodal behaviors and specific linguistic structures is still quite an uncharted territory. The existence of multimodal linguistic constructions or gestalts has been proposed[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], but such multimodal patterns are, for the most part, abstractions over a very limited number of instances of communicative behavior, usually observed in the lab, and very often also elicited. Typically, a ‘gesture,’ or any other non-verbal pattern, is analyzed as a sequence of discrete actions in bodily motion, composed by various steps. The generic ‘recipes’ to execute one of these sequences may or may not be realized simultaneously to the uttering of a related linguistic expression. When this happens, the gesture contribute to the meaning of the utterance, but they are generally regarded as optional or adjacent to language.

Such idea of multimodal behavior as a sequence of discrete units is coherent with a compositional view of language as a concatenation of symbols. Although the view of language as a string of individuated signs[

6] has led to important insights, segmentation problems overshadow all its many rival theories[

7]. This is becoming more evident as we move beyond technologies exclusively based on the verbal and textual, seeking to face the challenges of the multimodal stream. Small fluctuations or disalignments in the fineness of human interaction can strongly impact the swift prediction and exchange that underlie communication[

8]. If we view communication as action[

9], we are likely to be missing a lot by not looking into its subtle statistical patterns and their relation to language.

Nevertheless, it is certainly challenging to address the multimodal flow without abstracting its variability away. Cross-modal correlations found in psycholinguistic studies could provide evidence for multimodal signatures associated to specific verbal patterns[

10], but experimental studies cannot obtain enough tokens for the same linguistic expression. The skewed distribution of n-gram frequency in natural languages causes low frequencies of use for individual words and phrases[

11]. For example, most time phrases[

12] appear less than once per million in oral communication in English (data from COCA Spoken[

13]). It would be necessary to record thousands of hours of speech, from multiple speakers, in order to produce a lab sample with a significant number of tokens for most linguistic expressions.

Consider the dataset presented here, for time-deictic expressions in English. Deictic words or phrases express present/past/future with respect to a center of temporal reference. Some of them have relatively high frequencies of use according to COCA (“now” 1651,40 instances per million words; “today” 430,75 ipmw) [

13], but most are well under 100 instances per million words, many of them even under 1 per million (“at the moment” 15,76; “the previous month” 0,34; “the following month” 0,37). For the small pilot study presented here, we gathered an average of nearly 9 tokens per expression, for a total of 44 deictic words or phrases. This requires a minimum of around 40 million spoken words, given the frequencies of use in our corpus. Therefore, in order to produce the total of 379 tokens in our dataset, we would have needed to record around 6,000 hours of video from conversations by hundreds of different speakers, if we consider a rate of around 120 words per minute and include the pauses, hesitations, and transitions habitual in authentic oral communication. Full time-aligned transcripts would also be required for the resulting corpus.

Current time-aligned scientific corpora with quality recordings are dwarfed by these demands. For example, the transcripts of the Buckeye corpus from Ohio State University contain around 300,000 words from 40 speakers, roughly 40 hours of audio recordings [

14]. COCA Spoken is 127 million words; in total, COCA is just over 1 billion words, written + spoken. The whole British National Corpus is just over 100 million words, about 10 million for the audio part. None of these corpora have video data.

When the data are extracted from an audiovisual repository, of television or of any other source that, unlike lab recordings, is not produced with scientific purposes in mind, a considerable proportion of initial search results need to be filtered out, to eliminate repetitions and to discard clips where the speaker is non-visible (voice-overs, camera shifts at the moment in which the phrase is spoken, unclear shots, and so forth). Therefore, repositories at least in the tens of thousands of hours are needed to obtain enough tokens for most words or phrases, even for the sample size used in this pilot study.

These limitations have been affecting research into the correlations of specific linguistic structures and the fine details of bodily motion and other multimodal behaviors. This has resulted in a widespread assumption that multimodal behavior beyond speech articulation is essentially “non-verbal,” and mainly supplementary. To overcome these shortcomings, we need to correlate multiple instances of the same linguistic expressions with their co-occurring multimodal behaviors, carefully measuring their co-variation over time.

The analysis of multimodal corpora with multiple tokens for specific linguistic expressions will allow us to examine whether nuanced distinctions of meaning between words and phrases, alongside some of their linguistic features (frequency of use, length, stress distribution, morphosyntactic function) are predictive of a substantial part of the variability in so-called non-verbal behaviors. In that case, multimodal variability would cease to be a problem to become part of the solution: by being deeply structured and intertwined with meaning and communicative intention, multimodal behaviors would be crucial for humans to carry out complex communicative exchanges at daunting speed. Thus so-called non-verbal behaviors in the communicative signal could perhaps be more verbal than we think. New paths could then open for models that seek to generate and evaluate multimodal behaviors with such correlations in mind.

2. Materials and Methods

To build large-scale datasets with multiple video tokens for the same linguistic utterances, we extract our data from the UCLA NewsScape Library of TV News. NewsScape is an audio-visual repository holding over 700,000 hours of recordings and 5 billion words of close-captioning from news programs, mainly in English, with smaller collections in other 16 languages[

15]. NewsScape is developed by the Red Hen Lab

TM[

16]. NewsScape captures several hundred hours per week of news shows, from multiple recording stations around the world. Videos are forced-aligned with their transcripts. Thus the time-aligned subtitles can be searched with corpus-linguistic tools, and the hits display renders video clips in which the expressions searched were uttered. NewsScape’s broad selection of news shows (news broadcasts, late-night shows, gossip, interviews...) showcases multiple communicative situations, differing in number of participants, physical disposition, register, dialect, and so forth. For this pilot study, we searched the year 2016 of this collection, for which vrt files have been created, allowing a precise time-alignment of video and transcripts with Gentle[

17].

Given a group of linguistic patterns that we seek to investigate, we search NewsScape for videos containing these words and phrases. For these textual searches we use our own development of the corpus-linguistic software CQPweb[

18,

19]. The result is a concordance with a list of hits in the text of the NewsScape close-captioning (e.g. videos in which a speaker utters the word yesterday) linked directly to the moments in the shows when the word or phrase was uttered. We have developed a PHP plugin for CQPWeb, which allows for the download of the relevant sections of the videos, processed with ffmpeg[

20]. We then download and clip the videos searched via CQPWeb within a configurable time-window before and after the target n-gram (e.g., one second before and one second after the word yesterday is uttered).

Most hits resulting from these searches contain a non-valid video, mainly because the speaker is not on camera or it is a repetition (the same commercial, show, or news item broadcasted at different times). Repetitions can be automatically detected with text corpus tools. We have also developed a procedure for automatically filtering out the videos where the speaker is not clearly visible. For this we use OpenPose[

21,

22], a body key point detection software based on deep learning. OpenPose estimates the presence of a person or more in an image, and locates up to 137 key points of the body. We use OpenPose, python, and ffmpeg libraries to capture isolated frames of the videos, discarding any videos where we fail to locate a person and its relevant upper-body key points, such as nose and shoulders[

23].

Through manual annotation, we ensure that all videos in the final dataset show a speaker who utters the target n-gram. We label hundreds of these short videos (3-5 seconds each) per hour using the Rapid Annotator, an application that was developed for this purpose by Uhrig and collaborators [

24,

25]. Unlimited additional labels can be added to annotate for further variables related to statistical biases: e.g. the television genre, indoors or outdoors, sitting or standing, face-to-face or remote exchanges, and so forth. Corpora thus annotated have the potential to include hundreds or thousands of videos for each selected set of linguistic expressions, forced-aligned with their transcripts.

For all videos, OpenPose provides the absolute coordinates in 2D space for the key points of the speaker’s body in every frame, at the rate of approximately 30 frames per second for standard American television. These absolute coordinates in the image of each frame are not sensitive to position changes of the body or the camera. Therefore, we need to convert them into dynamic coordinates situating all key points with respect to a body center of our choice.

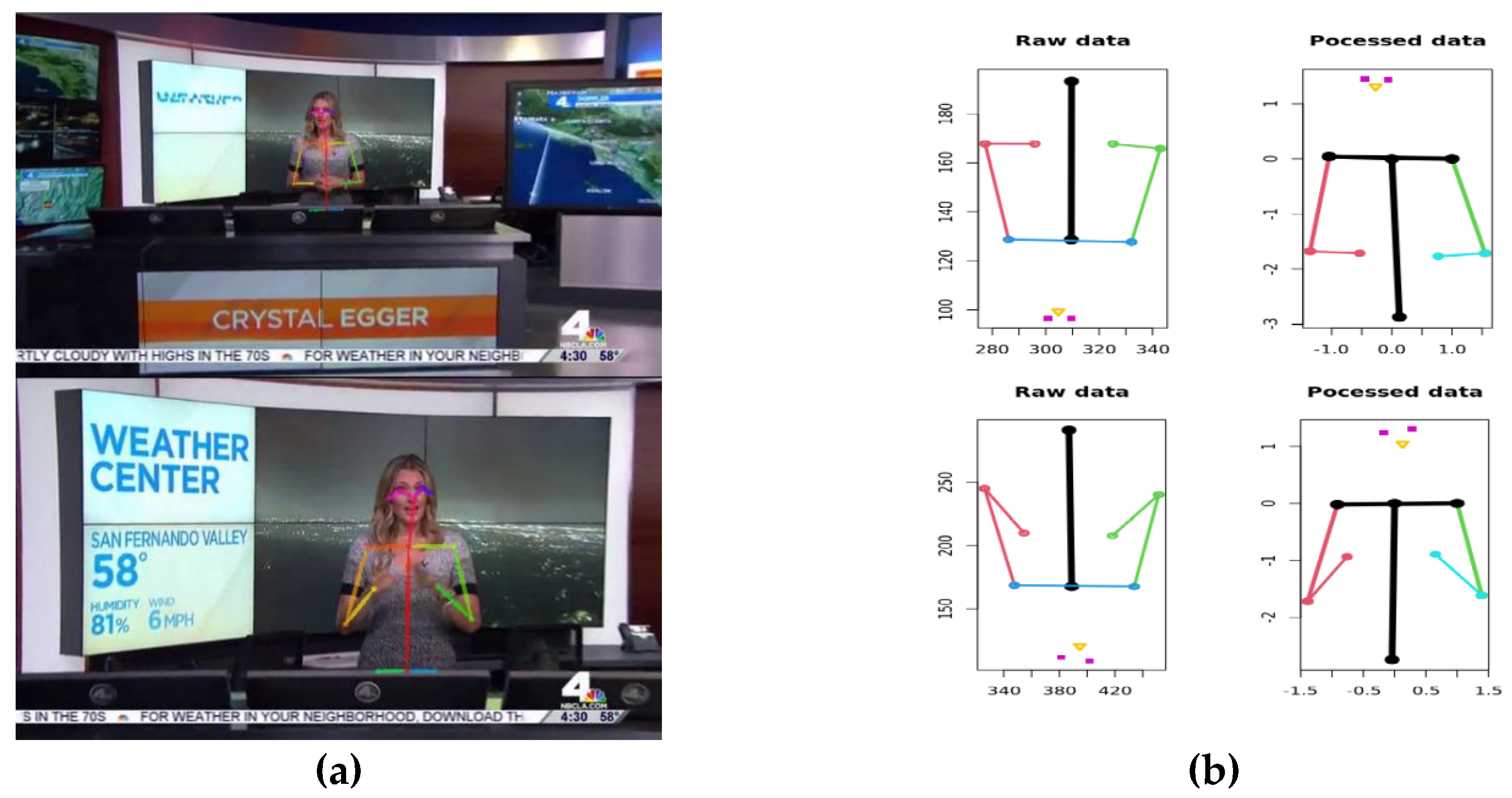

Using the R function dfmaker[

26], which we developed specifically for this purpose, we convert OpenPose JSON files to per-video CSV, structure per-frame records, and merge video metadata (filename, station, broadcast time/date) and linguistic labels (Rapid Annotator) into a single dataset containing spatial coordinates (x, y), frame index (≈33 ms), and OpenPose keypoint IDs (0–136). We then transform image coordinates into a body-centered system with xycorrector and cramerOpenPose: keypoint 1 (chest center) is the origin, the shoulder line sets the x-axis, and distances are normalized so that span 1↔5 equals +1 on x and span 1↔2 equals −1; this linear transform, solved via Cramer’s rule, produces dimensionless coordinates that are unaffected by resolution, zoom, or small in-plane rotations, thereby standardizing space across frames and speakers and enabling direct comparison and downstream statistical modeling.

As a result, all key point positions detected in a given video frame are located in relation to the central chest position and in proportion with the distance between central chest and left shoulder, independently of the changes in position of body and camera (

Figure 1). Each video is tested to ensure that the mean value of the distance between central chest and right shoulder (OpenPose points 1 and 2) lies within a value very close to -1, with the margin of error established statistically on the basis of a large sample of videos.

Using all the aforementioned methods, we extracted a dataset of 379 tokens from 44 linguistic expressions from NewsScape, the Ariadna dataset [

27]. Each token is labeled for its time expression and its time deixis (past/present/future). For every frame we have the detected positions of all or some of the 137 key body points provided by OpenPose. Here we offer some preliminary results examining the relationship between wrist position and the semantics of time deixis, that is, the distinction between past, present, and future.

3. Results

3.1. Wrist Position Is Correlated with the Present/Past/Future Distinction Across Time Deictic Expressions

3.1.1. Differences in Module Length for Polar Coordinates

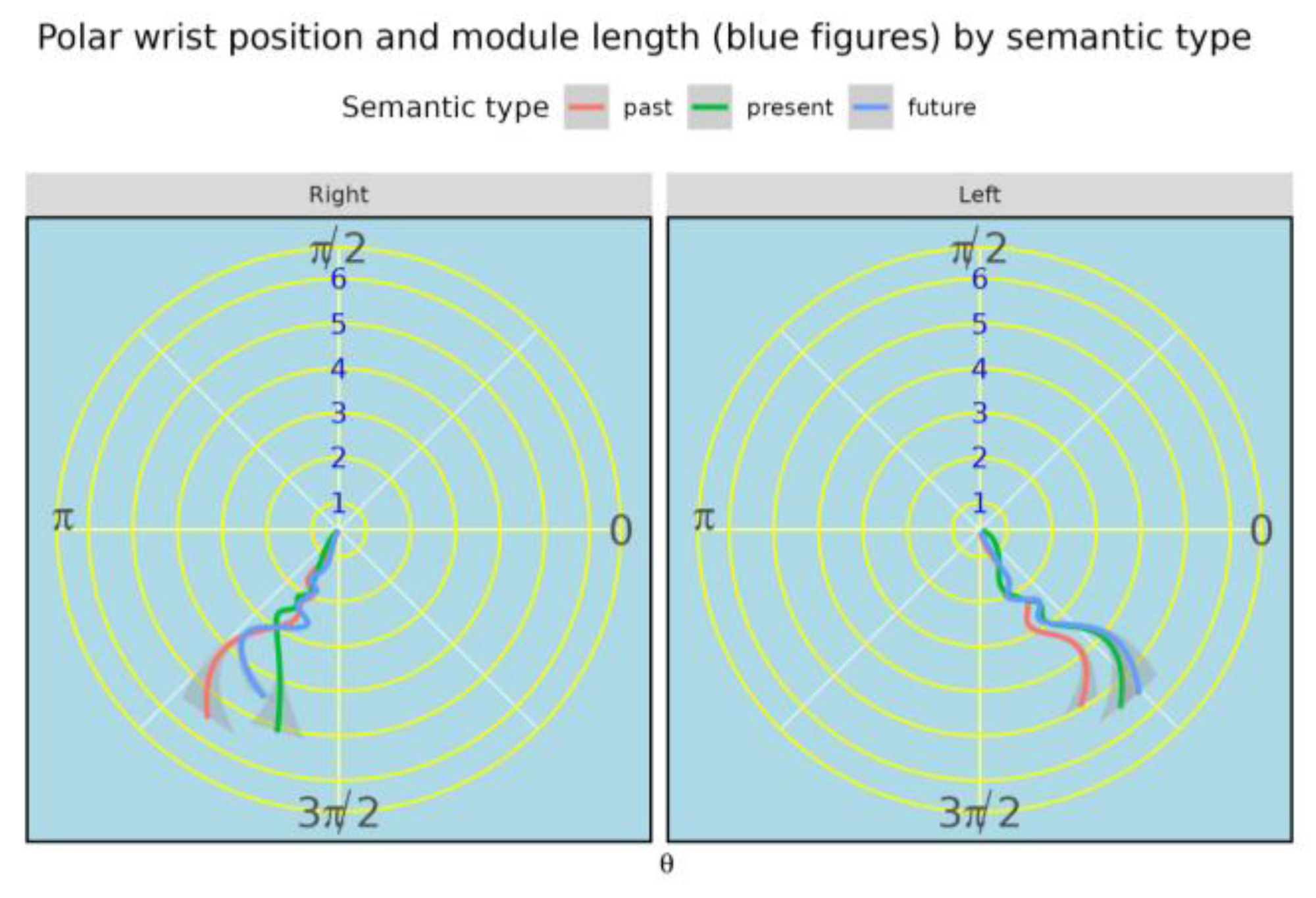

We represent wrist positions using polar coordinates centered on the chest (origin at OpenPose point 1). The module r is the Euclidean distance from the chest center to the wrist; small r indicates the hand is near the center of the torso, and large r indicates extension away from it. The angle \theta denotes direction on the goniometric circle. We refer to the third quadrant as π to 3π/2 and the fourth quadrant as 3π/2 to 0.

Because right-handed speakers are the majority in typical samples, the right hand exhibits greater positional variability overall. In the aggregate distribution (

Figure 2), most wrist positions cluster near the center (small r), which limits discrimination by semantic type at this level. Nevertheless, when attention shifts to larger radii, distinct profiles emerge, especially for past expressions in both hands. In addition, for present expressions the right hand tends to move closer to the chest and to appear in the fourth quadrant; there is no corresponding symmetric pattern of the left hand invading the third quadrant. Overall, the left hand shows only minor separation among past, present, and future when all radii are pooled.

Although

Figure 2 provides a useful overview, it is dominated by positions near the chest (small module), which introduces noise for semantic discrimination. In any clip with a deictic utterance, most wrist detections fall within this central region of the gesture space. This area contains most of the information for the reconstruction of the path followed by any particular gestural motion. However, at this stage we summarize overall spatial distributions, not time-ordered trajectories, so central clustering carries the most mass but the least discriminative power. This motivates focusing on larger module values in §3.1.2.

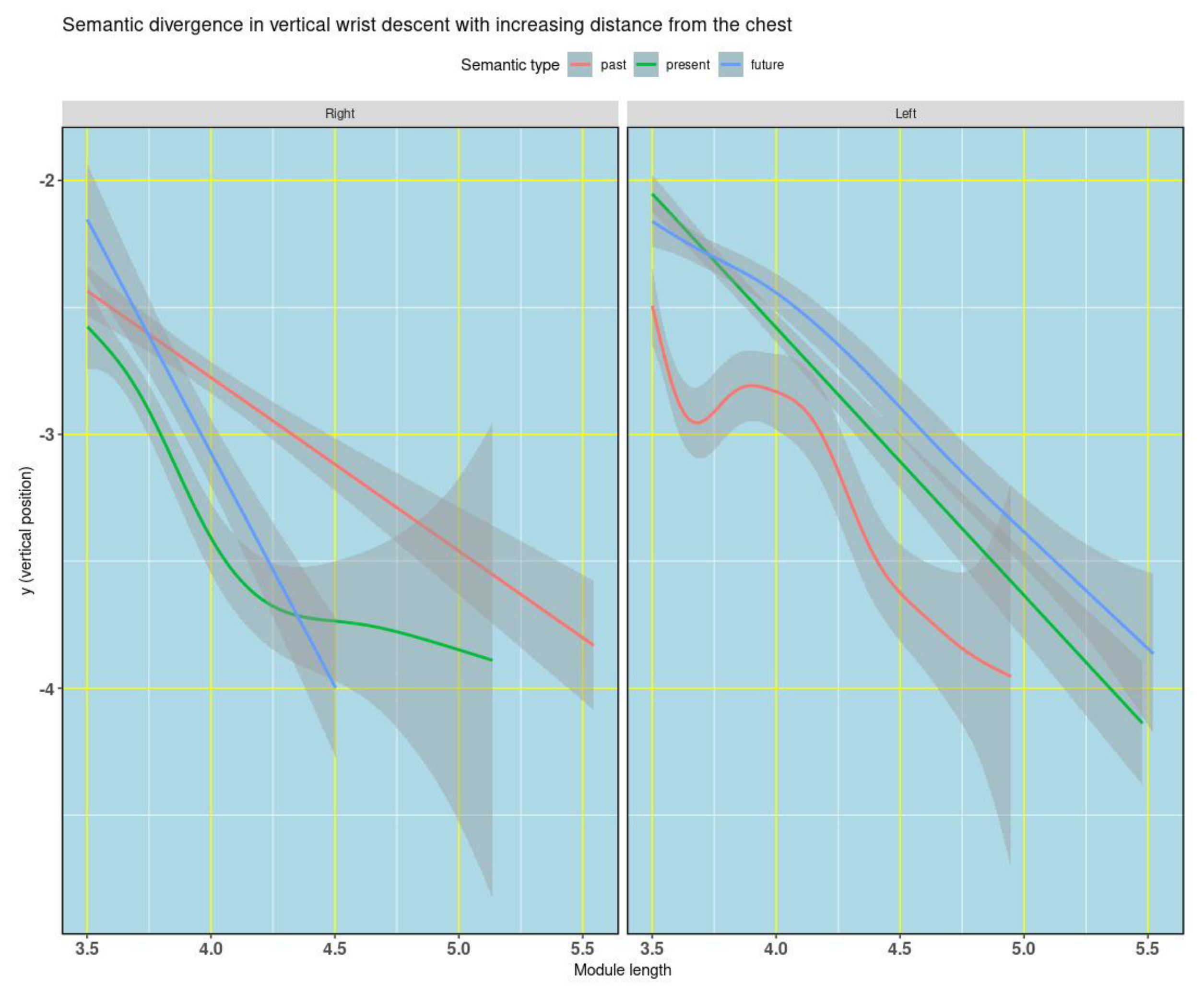

3.1.2. Larger Module Length Values Correlate with the Present/Past/Future Distinction

To reduce central clustering and focus on informative positions, we examine the relationship between normalized wrist height (ny) and module (r) only for larger radios, setting a threshold of r>= 3.5 within each hand’s lower quadrant (left: third; right: fourth;

Figure 3). This choice minimizes the dominance of near-chest positions and increases sensitivity to semantically relevant differences.

As expected, ny decreases as r increases. Holding the hand both far from the chest and high in space is effortful; therefore, greater extension is typically associated with lower vertical positions. The key result is not the decline itself but its semantic modulation. From r=3.5 onward, past, present, and future show distinct patterns of ny over r. Generalized additive models capture these differences (

Figure 3), and they remain detectable under simpler linear assumptions for r >= 3.5 (

Table 1).

At higher radios, past vs. present is clearly separated in both quadrants. The future category is also separated in the left (third) quadrant, whereas the right (fourth) quadrant exhibits greater variability and a more complex pattern for future. This variability increases the significance of the future vs. past distinction. Across quadrants, as r grows, the present tends to occupy intermediate ny values between past and future. By focusing on the higher module-lengths, we get clearly-differentiated effects for past and present, and future for the right quadrant (4th), almost reaching significance for future also for the 3rd quadrant.

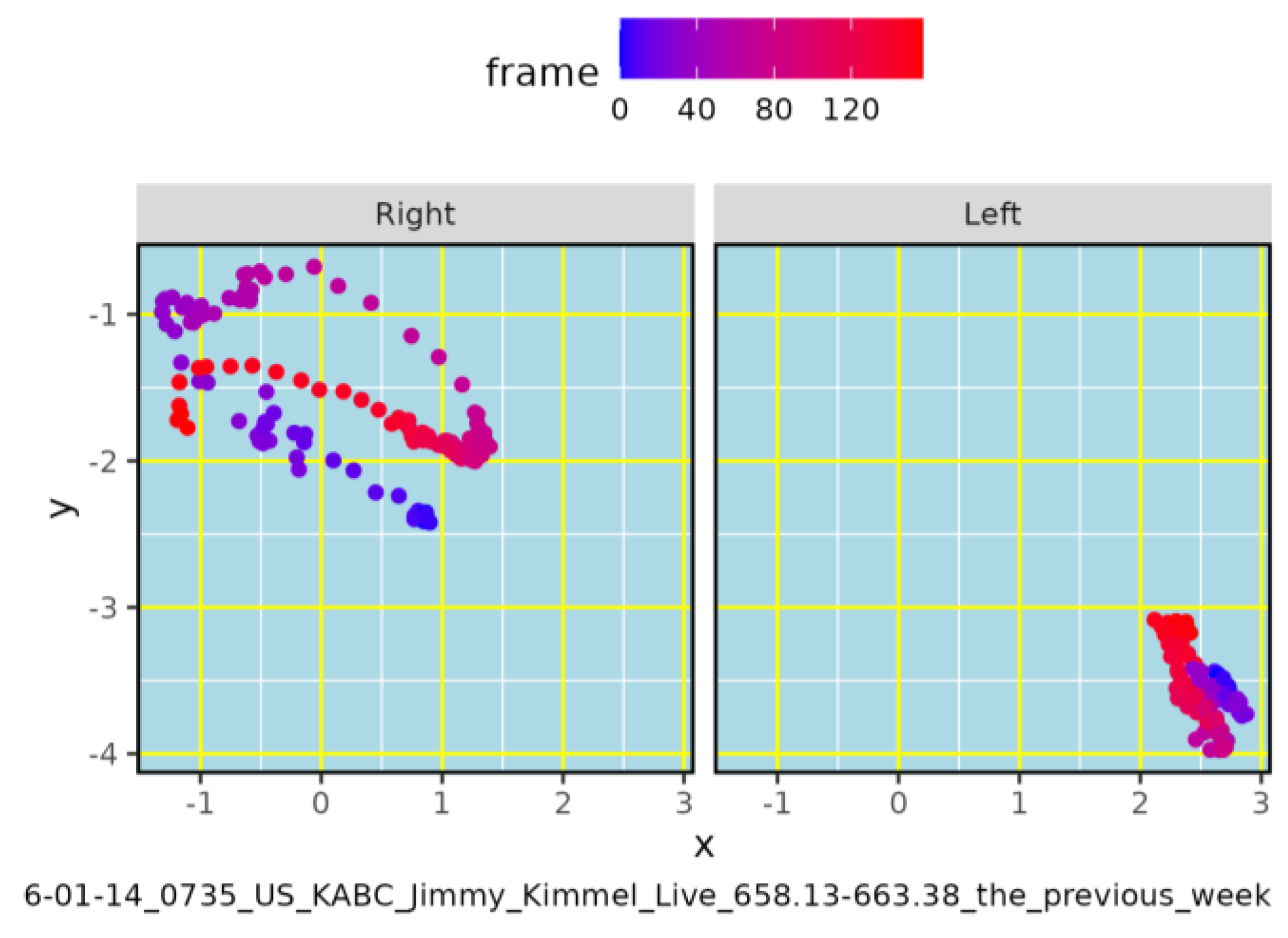

3.1.3. 2D Reconstruction of Gesture Trajectories can Be Aligned with Other Data

Building on the spatial analyses above, we reconstruct 2D wrist trajectories by ordering wrist coordinates frame by frame. This converts unordered position clouds into time-resolved motion paths, enabling the study of dynamics (e.g., approach/withdrawal, turns) and their temporal alignment with other modalities such as prosody and the words uttered by the person gesturing. These reconstructions allow us to test whether individual deictic expressions exhibit distinct motion profiles over time, beyond effects visible in static distributions.

Figure 4 illustrates a trajectory derived exclusively from wrist keypoints (OpenPose 4 and 7) for one video clip constituting a token for the expression “the previous week”. Each point corresponds to one video frame (approx 0.033 s per frame), and a color gradient encodes temporal progression along the path. To maintain geometric comparability across frames, we normalize the x and y axes using the distance between the chest center (OpenPose 1; origin) and the left shoulder (OpenPose 5); this scale is kept proportional over time. The file name shown below the plot records the TV program and date, the clip time interval, and the queried expression (e.g., “the previous week”), facilitating precise cross-reference and multimodal alignment. We can see how the right hand performs a gestural motion of certain amplitude, while the left hand only makes slight motions with no clear trajectory.

4. Discussion

This methodology allows us to systematically study the relationship between gestural motion, what is being said and/or intended in a communicative exchange, the words that are co-located with it, and any other relevant variables, related to the communicative situation or to any other aspects being studied or evaluated. As a very preliminary analysis,

Figure 3 shows a systematic relation between English time expressions of past, present, and future, and the distribution of wrist positions relative to the center chest—still without taking trajectories and time series into consideration: only distributions of positions along the x-y axis and distance from the chest center. Even at this level of granularity, the non-aleatory relation becomes evident: hand motion is affected by the semantic distinctions of their co-occurring words or phrases. By examining correlations throughout numerous tokens of the same linguistic expression, we can begin the task of modeling the statistical profiles of co-speech gesture in relation with linguistic meaning.

Thus we find that the distinction between past, present, and future influences wrist motion co-occurring with deictic expressions, even when we still do not have those detailed models and without considering the data from the central area, where most of the gesturing action takes place. Given that we are analyzing a not very large sample for a set of linguistic expressions that are very close in meaning, this evidence for systematicity between hand motion and semantic distinctions is quite remarkable. We can expect to get stronger effects if we compare, for example, temporal expressions with others that do not refer to time. Moreover, analyzing a set of language resources that often contrast with each other for semantic distinction (e.g. last/this/next year/month/week) renders quite coherent gestural patterns, suggesting a multimodal system for discriminating between these meanings.

Scaling up such data analysis will provide us with the opportunity to establish systematic relations between any linguistic pattern and its co-occurring bodily motion. The relevance of such methods for the generation and evaluation of multimodal behaviors in communication is hard to exaggerate. In order to realistically simulate human communicative behavior, we can now train new models that will connect fine-grained linguistic distinctions with detailed predictions for the variation of trajectories and the probability of motion in different areas of the gesture space. With the body pose detection technology used for this paper, the same can also be done for multiple body parts, also including facial expression. More sophisticated regression of human bodies can provide ever more accurate and detailed data. Given the skewedness of word frequency distributions, in all cases it will be crucial to rely on large-scale datasets, such as NewsScape, to obtain sizeable samples with multiple tokens for any given verbal pattern.

The design of multimodal interfaces is not yet based on these detailed correspondences between language and multimodal behavior, mainly because we did not yet have the methodology to explore them. The methods and preliminary results here presented open a new field of collaboration between researchers in communication, mathematics, and engineering. Scaling up the methods and results outlined here is now mainly a matter of resources and ingenuity. We have the opportunity to draw a detailed map of multimodal signatures of meanings in language, by combining natural language understanding, including the recent large language models being developed, and the computer-vision and speech-analysis technologies at hand, alongside the recent developments in machine learning and in the computational application of statistical techniques such as generalized additive models. Avatars, robots, simulations, evaluation-systems, and any other technologies can now be informed by these new insights into the multimodal patterns of human communicative behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas; methodology, Brian Herreño Jiménez and Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas; software, Brian Herreño Jiménez and Raúl Sánchez Sánchez; validation, Brian Herreño Jiménez and Raúl Sánchez Sánchez; formal analysis, Brian Herreño Jiménez and Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas.; investigation, Ariadna López Bernal and Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas; resources, Brian Herreño Jiménez and Raúl Sánchez Sánchez; data curation, Brian Herreño Jiménez, Raúl Sánchez Sánchez, Daniel Alcaraz Carrión and Ariadna López bernal; writing—original draft preparation, Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas; writing—review and editing, Brian Herreño Jiménez, Raúl Sánchez Sánchez and Daniel Alcaraz Carrión; visualization, Brian Herreño Jiménez; supervision, Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas.; project administration, Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas; funding acquisition, Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Spain’s Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, through a Research Consolidation Grant, grant number CNS2022-135806, to Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas as PI.

Data Availability Statement

As stated in the article, the dataset developed for this study, also including sample video clips, is available from:

https://daedalus.um.es/?page_id=109/#Datasets. The video repository used to build the corpus for this dataset, the NewsScape Library of Television News, is of restricted access, due to copyright laws. Access related to research purposes, including, among other uses, peer-review evaluation and new studies, can be requested from the directors of the International Distributed Little Red Hen Lab™. See:

https://www.redhenlab.org/access-to-red-hen-tools-and-data.

Acknowledgments

We thank the directors of the Red Hen Lab, Professors Francis Steen (University of California Los Angeles) and Mark Turner (Case Western Reserve University), for access to the data and tools developed by Red Hen, and for constant support and participation in grants and multiple academic activities related to this study. We thank Professor Peter Uhrig (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg) for his contributions to the development of the Rapid Annotator and other tools used for this study, and for his constant availability for consulting in relation with those tools. We thank Professor Javier Valenzuela (University of Murcia) for his support to the partnership with the Red Hen Lab through the Daedalus Lab Research Group at the University of Murcia, and his facilitation for the use of the tools involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A Figures and model code

Appendix A.1 Polar representation (Figure 2)

# A.1 Polar wrist position by temporal semantic type

read.csv("Data.csv") -> data

library(ggplot2)

# Factors

if ("semType" %in% names(data)) data$semType <- factor(data$semType, levels=c("past","present","future"))

if ("wrists" %in% names(data)) data$wrists <- factor(data$wrists, levels=c("Right","Left"))

# Ring numbers (1..6) placed at pi/2 for each facet

labs_rad <- expand.grid(wrists = levels(data$wrists), module = 1:6)

labs_rad$angle <- pi/2

labs_rad$label <- as.character(labs_rad$module)

ggplot(data = data, aes(module, angle, col = semType)) +

geom_smooth(se = TRUE) +

geom_text(data = labs_rad, aes(x = module, y = angle, label = label),

inherit.aes = FALSE, size = 3.5) +

coord_polar(theta = "y", direction = -1, start = 3*pi/2) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 2*pi),

breaks = c(0, pi/2, pi, 3*pi/2),

labels = expression(0, pi/2, pi, 3*pi/2)) +

theme(panel.border = element_rect(size = 1, fill = NA),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = 'lightblue'),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "yellow"),

legend.position = "top",

axis.text = element_text(face = "bold", size = 16),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5)) +

facet_wrap(~ wrists) +

labs(title = "Polar wrist position by temporal semantic type",

y = "Module length", x = expression(theta),

col = "Semantic type")

Appendix A.2 — Vertical position vs. distance (Figure 3)

# A.2 ny ~ module (long modules), faceted by wrist

df <- subset(data, module >= 3.5)

ggplot(df, aes(x = module, y = ny, col = semType)) +

geom_smooth(method = "gam", formula = y ~ s(x), se = TRUE) +

facet_wrap(~ wrists) +

labs(title = "Semantic divergence in vertical wrist descent with increasing distance from the chest",

x = "Module length", y = "y (vertical position)",

col = "Semantic type") +

theme(panel.border = element_rect(size = 1, fill = NA),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "lightblue"),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "yellow"),

legend.position = "top",

axis.text = element_text(face = "bold", size = 12))

Appendix A.3 — Linear models by quadrant (Table 1)

# A.3 Linear models by quadrant, with modules >= 3.5

data_long <- subset(data, module >= 3.5)

# 3rd quadrant (x<0, y<0)

data_q3 <- subset(data_long, nx < 0 & ny < 0)

mod_q3 <- lm(ny ~ module + semType, data = data_q3)

summary(mod_q3)

# 4th quadrant (x>0, y<0)

data_q4 <- subset(data_long, nx > 0 & ny < 0)

mod_q4 <- lm(ny ~ module + semType, data = data_q4)

summary(mod_q4)

Appendix A.4 — Angle calculation and normalization to [0,2π) (method and check)

# A.4 Module (distance) and angle (direction) from the chest

# Note: atan2(ny, nx) returns angles in (-pi, pi]; to work in [0, 2*pi) we normalize.

# Vectorized calculation

data$module <- sqrt(data$nx^2 + data$ny^2)

theta_raw <- atan2(y = data$ny, x = data$nx) # (-pi, pi]

data$angle <- ifelse(theta_raw < 0, theta_raw + 2*pi, theta_raw) # [0, 2*pi)

# (Optional check) Ranges in degrees by geometric quadrant

deg <- data$angle * 180/pi

range_Q1 <- range(deg[data$nx > 0 & data$ny > 0], na.rm = TRUE) # 0°..90°

range_Q2 <- range(deg[data$nx < 0 & data$ny > 0], na.rm = TRUE) # 90°..180°

range_Q3 <- range(deg[data$nx < 0 & data$ny < 0], na.rm = TRUE) # 180°..270°

range_Q4 <- range(deg[data$nx > 0 & data$ny < 0], na.rm = TRUE) # 270°..360°

list(Q1 = range_Q1, Q2 = range_Q2, Q3 = range_Q3, Q4 = range_Q4)

atan2(ny, nx) returns the angle in radians relative to the +x axis, with sign: negative values when ny < 0 (lower half-plane) and positive values when ny ≥ 0. To work with non-negative angles in (0°–360°), add 2π to negative angles. This is equivalent to the manual adjustment in the 3rd and 4th quadrants; the version with quadrant conditions and the + 2*pi adjustment implements the same normalization. The final check reports that each region falls within its expected range (Q1 ≈ 0–90°, Q2 ≈ 90–180°, Q3 ≈ 180–270°, Q4 ≈ 270–360°).

Appendix B — Definitions of Module and Angle θ

The wrist–chest distance (module) is defined as the Euclidean distance between the wrist coordinates (x_wrist, y_wrist) and the chest coordinates (x_chest, y_chest):

\text{module} = \sqrt{(x_{\text{wrist}} - x_{\text{chest}})^2 + (y_{\text{wrist}} - y_{\text{chest}})^2}

The orientation of this vector is given by the angle θ, computed using the two-argument arctangent:

\theta = \operatorname{atan2}(y_{\text{wrist}} - y_{\text{chest}}, \; x_{\text{wrist}} - x_{\text{chest}})

Normalized to the interval [0, 2π).

Finally, the normalized vertical wrist coordinate (y) was modeled as a function of module and the deictic category D ∈ {past, present, future} (with past as the reference). The general linear model can be expressed as:

References

- Holler, J.; Levinson, S.C. Multimodal language processing in human communication. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, S.C.; Holler, J. The origin of human multi-modal communication. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, F.; Turner, M.B. Multimodal Construction Grammar. In Language and the Creative Mind; Borkent, M., Dancygier, B., Hinnell, J., Eds.; CSLI Publications: Stanford, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T. Multimodal constructs—multimodal constructions? The role of constructions in the working memory. Linguist. Vanguard 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienki, A. Utterance Construction Grammar (UCxG) and the variable multimodality of constructions. Linguist. Vanguard 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saussure, F. Cours de linguistique générale; Payot: Paris, France, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen, R.H.; Ramscar, M. learning. In Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics; Dabrowska, E., Divjak, D., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, S.C. On the human "interaction engine". In Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition and Interaction; Enfield, N.J., Levinson, S.C., Aiello, L.C., Eds.; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H.H. Using Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, S.; Healey, M.; Özyürek, A.; Holler, J. The processing of speech, gesture, and action during language comprehension. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2015, 22, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipf, G.K. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least-Effort; Addison-Wesley: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán Cánovas, C.; Valenzuela, J.; Carrión, D.A.; Olza, I.; Ramscar, M. Quantifying the speech-gesture relation with massive multimodal datasets: Informativity in time expressions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Pitt, M.A.; Johnson, K.; Hume, E.; Kiesling, S.; Raymond, W. Buckeye Corpus of Conversational Speech (2nd Release); Department of Psychology, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2007; Available online: https://buckeyecorpus.osu.edu/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Steen, F.F.; Hougaard, A.; Turner, M.; Stjernfelt, F.; Almonte, J.L.; Pagán Cánovas, C.; Engberg-Pedersen, E.; Cienki, A. Toward an infrastructure for data-driven multimodal communication research. Linguist. Vanguard 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Hen Lab. Available online: https://www.redhenlab.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Gentle. Available online: https://lowerquality.com/gentle/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Hardie, A. CQPweb—Combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 2012, 17, 380–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CQPweb Main Page. Available online: https://cqpweb.lancs.ac.uk/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- FFmpeg. Available online: https://ffmpeg.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.08008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CMU-Perceptual-Computing-Lab. OpenPose Repository. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/CMU-Perceptual-Computing-Lab/openpose (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- daedalusLAB. mario_plumber/is_there_a_person_in_the_video Repository. Available online: https://github.com/daedalusLAB/mario_plumber/tree/main/is_there_a_person_in_the_video (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Red Hen Lab. Red Hen Rapid Annotator. Available online: https://www.redhenlab.org/home/tutorials-and-educational-resources/-red-hen-rapid-annotator (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- MULTIFLOW RapidAnnotator OpenPose Demo. Available online: https://gallo.case.edu/go/cpc/0001/video_erc.mp4 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- multimolang R Package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/multimolang/readme/README.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Multimodal Datasets. Available online: https://daedalus.um.es/?page_id=109/#Datasets (accessed on 18 September 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).