Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

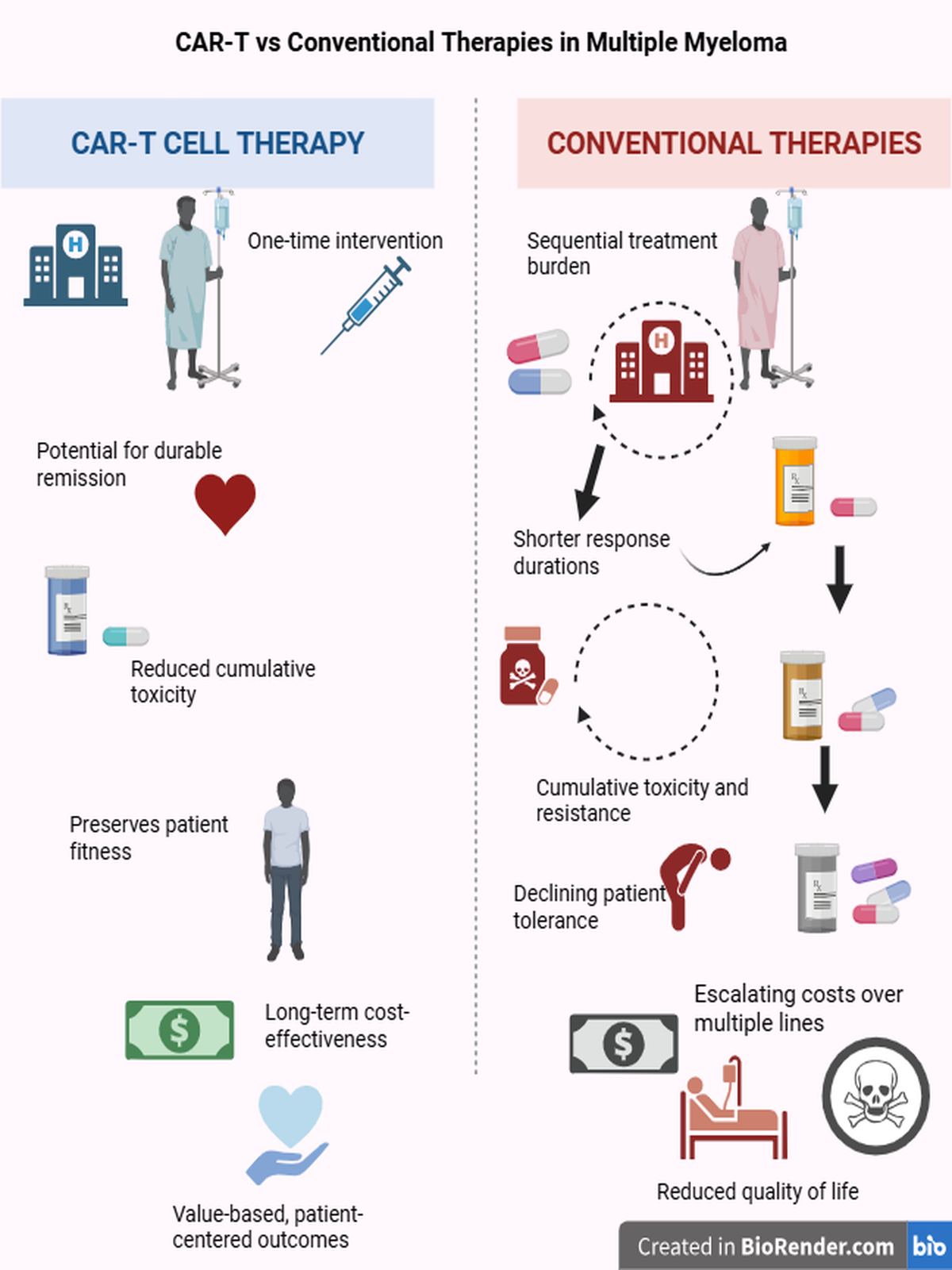

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Dedication

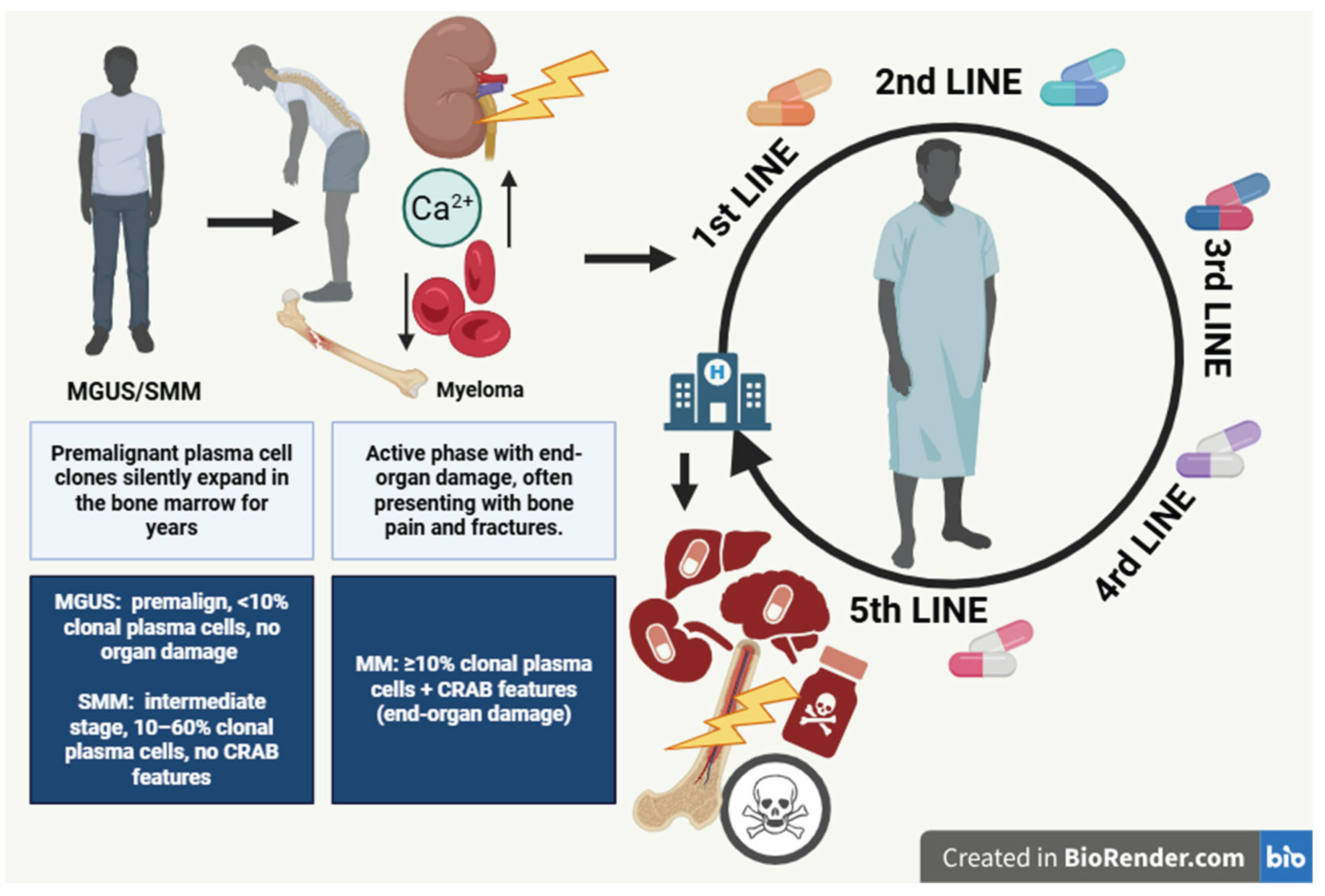

1. Introduction

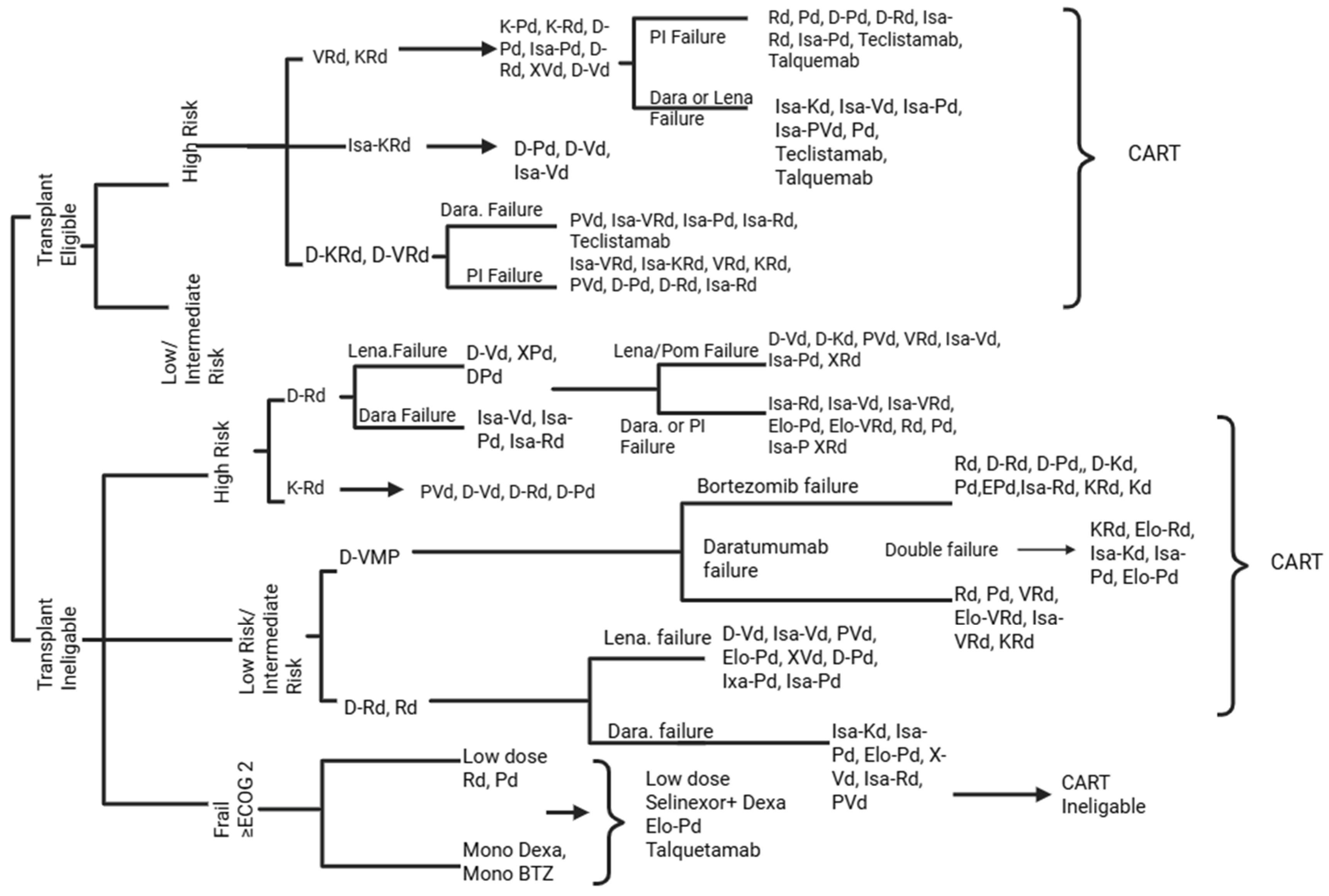

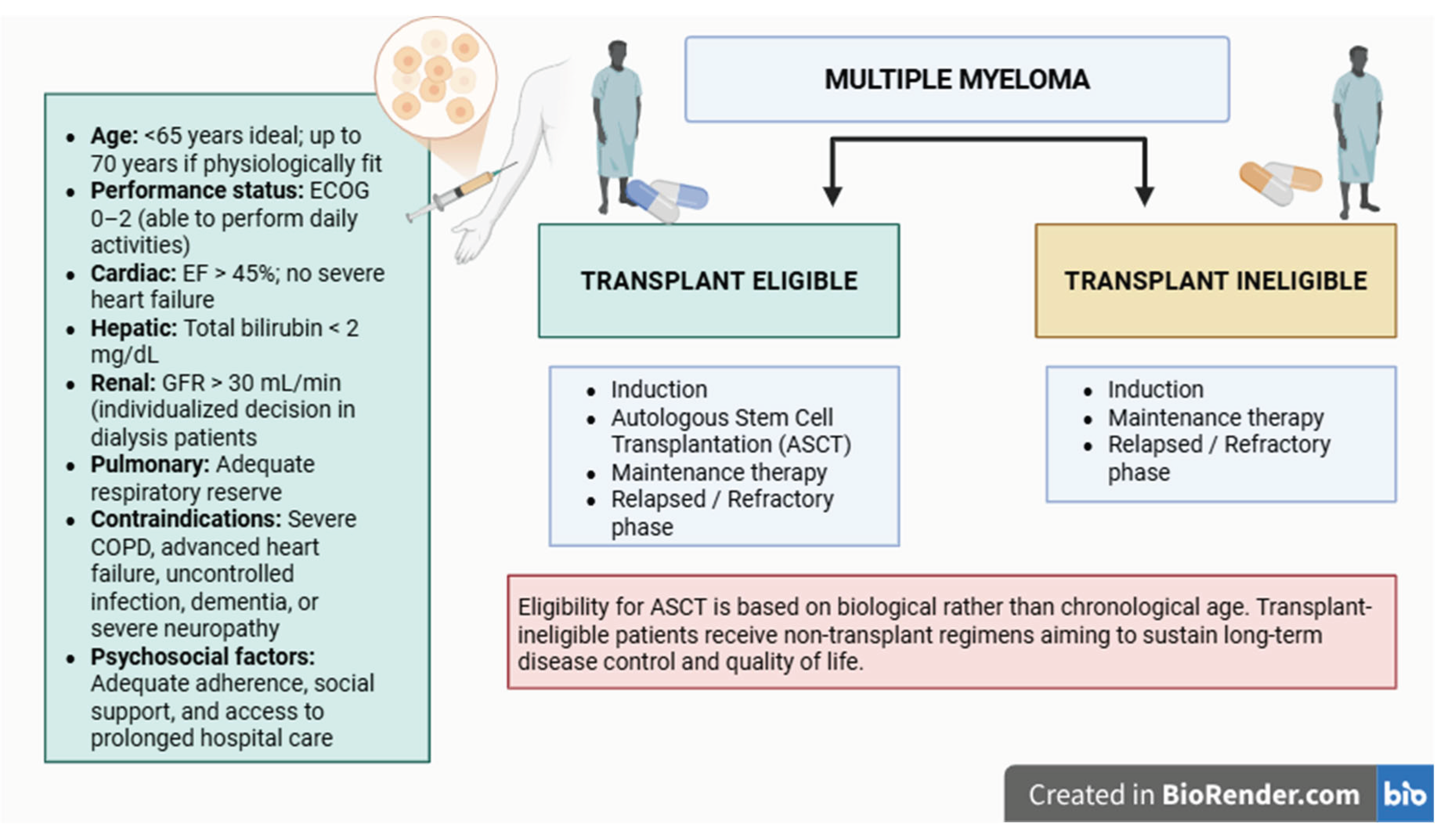

2. Myeloma Therapies

2.1. Induction Therapies

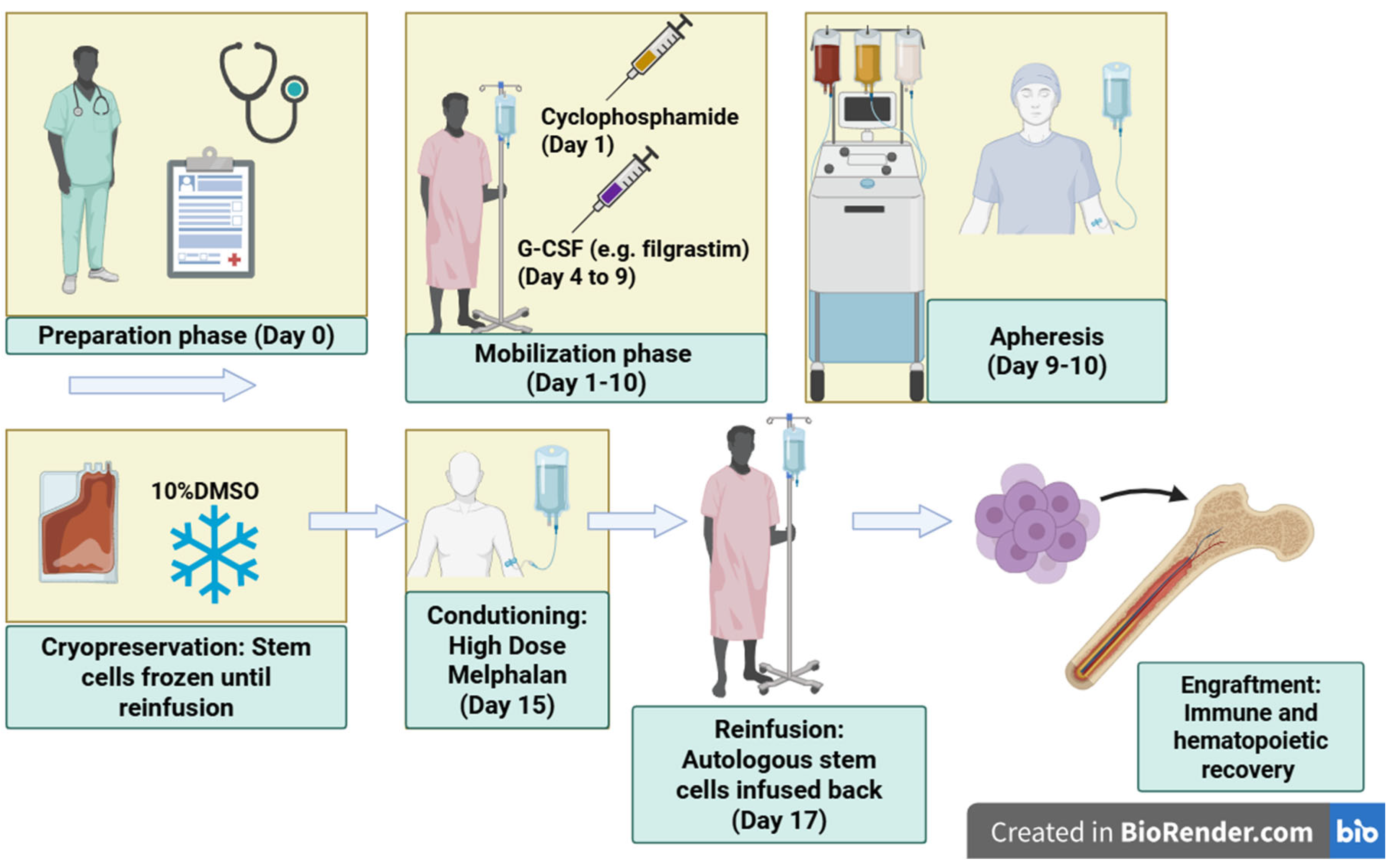

2.2. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

2.3. Maintenance Therapies

2.4. Relapsed/Refractory Phase

3. CAR-T Therapies

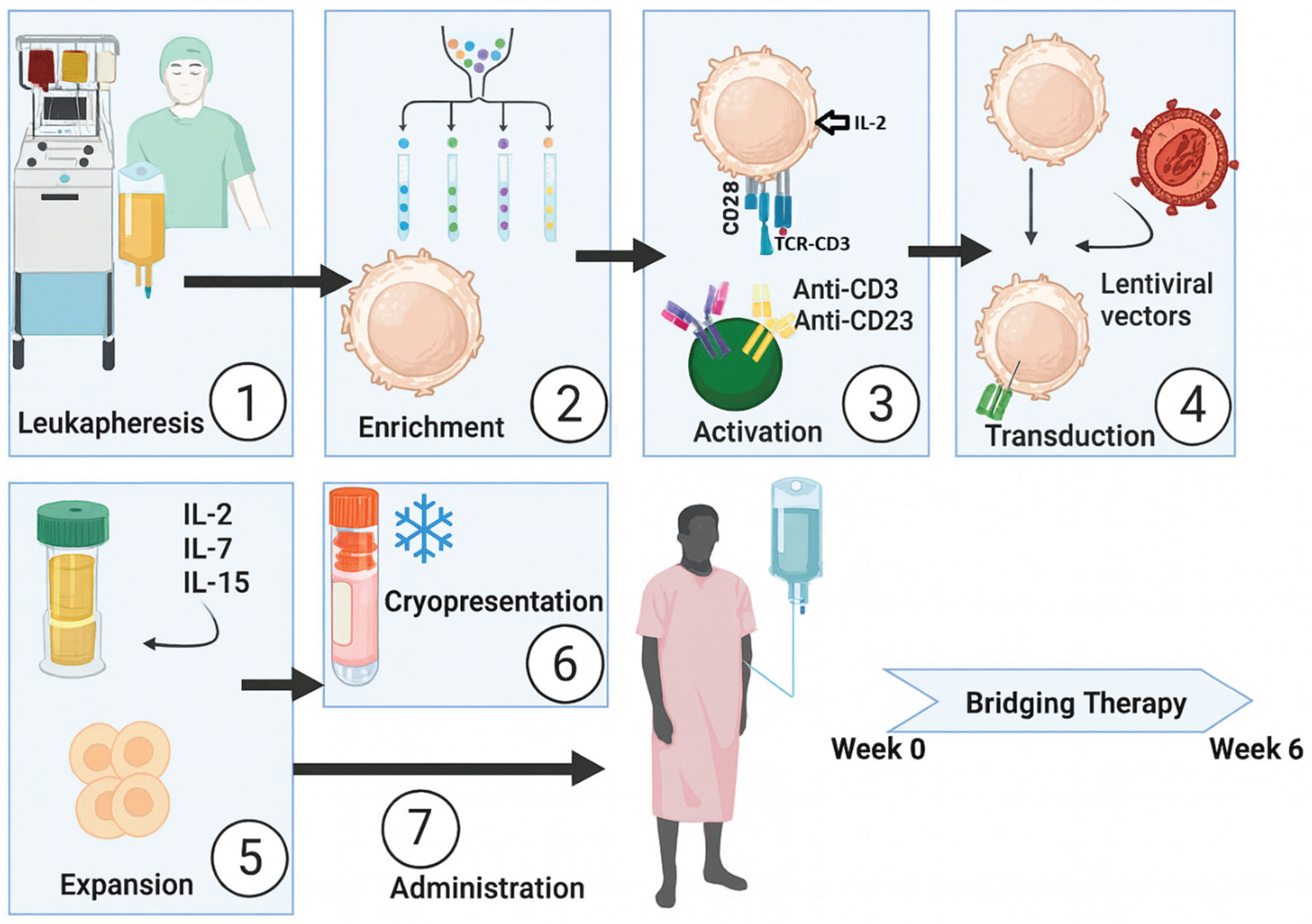

3.1. Treatment Process and Clinical Application

- Activation: stimulation using anti-CD3/CD28 microbeads and cytokines such as IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15.

- Genetic modification: transduction of the CAR construct, most commonly via lentiviral vectors.

- Expansion: large-scale proliferation in controlled culture systems to generate millions of CAR-T cells.

- Quality control and cryopreservation: verification of cell viability, microbial safety, and CAR expression, followed by freezing and storage until infusion.

3.2. Clinical Efficacy, Innovations, and Limitations of CAR-T Cell Therapy

3.3. CAR-T Cell Trials

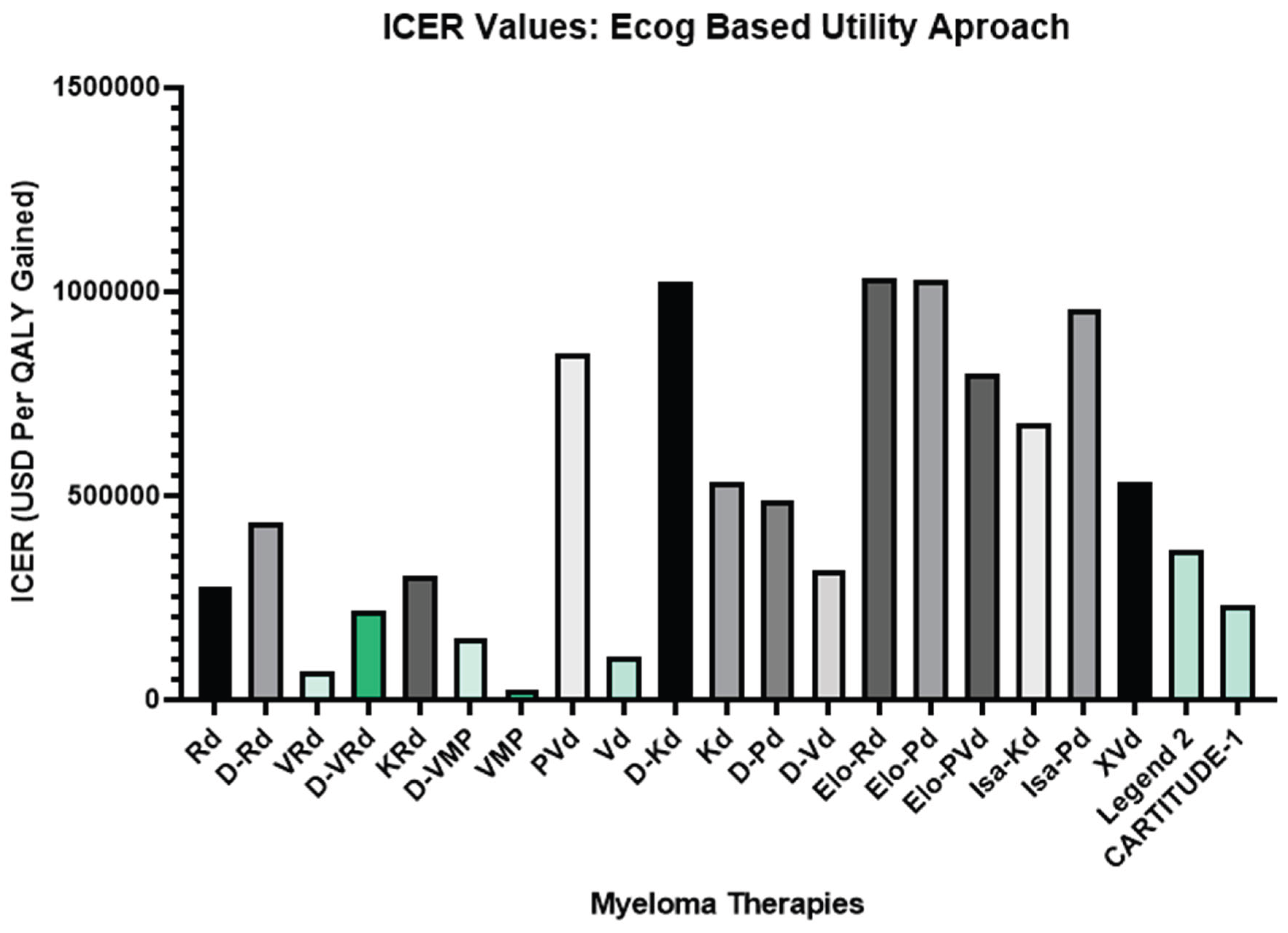

4. Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) and ECOG-Based Modeling

- Low ICER → higher cost-effectiveness

- High ICER → lower value or higher cost per QALY [95]

5. Methods (Summary)

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Availability of Data and Materials

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

Consent for Publication

Appendix A

| Therapy / Class | Year (Approval / Milestone) | Mechanism / Target | Current Use in MM | Key Toxicities |

| Autologous Stem Cell Transplant (ASCT) | 1983 (MM application) | Hematopoietic rescue | Standard in eligible patients | Myelosuppression, infection risk |

| Bortezomib (first PI) [103,104] | 2003 | Reversible 20S proteasome inhibitor | Backbone of induction (VRd etc.) | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Carfilzomib (2nd-gen PI) [104] | 2012 | Irreversible PI | Relapsed/refractory, combo regimens | Cardiac toxicity |

| Ixazomib (oral PI) [104] | 2015 | Oral PI | Maintenance, frail patients | GI, mild cytopenias |

| Lenalidomide (IMiD) [102] | 2005 | IMiD, cytokine modulation, T-cell activation | Frontline & maintenance backbone | Cytopenias, thrombosis |

| Pomalidomide (IMiD) [105] | 2013 | Next-gen IMiD | Relapsed/refractory settings | Cytopenias, infections |

| Daratumumab (anti-CD38 mAb) [1,107] | 2015 | ADCC, CDC, ADCP, direct apoptosis | Widely used frontline & RRMM | Neutropenia, infusion reactions |

| Isatuximab (anti-CD38 mAb) [1,106] | 2020 | Distinct CD38 epitope, direct apoptosis | Combo with Pd in RRMM | Neutropenia, infections |

| Selinexor (XPO1 inhibitor) [1,106] | 2019 | Nuclear export inhibition, p53 reactivation | Triple-class refractory | GI toxicity, cytopenias |

| Venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) [1,106] | Investigation | BCL-2 inhibition | Targeted subgroup (t(11;14)) | Tumor lysis, cytopenias |

| Melflufen (peptide-drug conjugate) [1,106] | 2021 (revoked FDA approval) | Alkylating payload via peptide conjugate | EMA-approved, not FDA | Cytopenias, survival concern |

| HDAC inhibitors (e.g., panobinostat) [1,106] | 2015 (panobinostat FDA) | Histone deacetylase inhibition | Adjunct in refractory disease | GI, fatigue, cytopenias |

| Checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1/PD-L1) [1,106] | Trials (halted in MM) | Immune checkpoint blockade | Investigational only | Immune toxicities |

| Bispecific Abs / CAR-T / NK [1,106] | 2020s | Redirected T/NK cytotoxicity | Rapidly emerging | CRS, neurotoxicity, cytopenias |

Appendix B

References

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024;99(9):1802–1824. [CrossRef]

- Mavrothalassitis E, Triantafyllakis K, Malandrakis P, et al. Current treatment strategies for multiple myeloma at first relapse. J Clin Med. 2025;14(5):1655. [CrossRef]

- Gay F, Marchetti E, Bertuglia G. Multiple myeloma unpacked. Hematol Oncol. 2025;43(Suppl 2):e70067. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca R, Hinkel J. Value and cost of myeloma therapy- we can afford it. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:647–655. [CrossRef]

- Lopes R, Caetano J, Ferreira B, et al. The immune microenvironment in multiple myeloma: friend or foe? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(4):625. [CrossRef]

- Chroma K, Skrott Z, Gursky J, et al. A drug repurposing strategy for overcoming human multiple myeloma resistance to standard-of-care treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:203. [CrossRef]

- Du J, Fu W, Jiang H, et al. Updated results of a phase I, open-label study of BCMA/CD19 dual-targeting FASTCAR-T GC012F for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Hemasphere. 2023;7(Suppl):e84060bf. [CrossRef]

- Swan D, Madduri D, Hocking J. CAR-T cell therapy in multiple myeloma: current status and future challenges. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:206. [CrossRef]

- Prommersberger S, Reiser M, Beckmann J, et al. CARAMBA: a first-in-human clinical trial with SLAMF7 CAR-T cells prepared by virus-free Sleeping Beauty gene transfer to treat multiple myeloma. Gene Ther. 2021;28:560–571. [CrossRef]

- Moradi V, Omidkhoda A, Ahmadbeigi N. The paths and challenges of “off-the-shelf” CAR-T cell therapy: an overview of clinical trials. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;169:115888. [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt MJ, Schaefers C, Leypoldt LB, et al. Activity of CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma with extramedullary involvement. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:126. [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(4):335–347. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, et al. Ide-cel or standard regimens in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(11):1002–1014. [CrossRef]

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(6):2962–2972. [CrossRef]

- Mian O, Puts M, McCurdy A, et al. Decision-making factors for an autologous stem cell transplant for older adults with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a qualitative analysis. Front Oncol. 2023;12:974038. [CrossRef]

- Cornell RF, D’Souza A, Kassim AA, et al. Maintenance versus induction therapy choice on outcomes after autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(2):269–277. [CrossRef]

- Mateos MV, San-Miguel J, Cavo M, et al. Bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone with or without daratumumab in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): final analysis of an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26(5):596–608. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Choi J, Min CK, et al. Superior outcomes and high-risk features with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone combination therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: results of the multicenter KMMWP2201 study. Haematologica. 2024;109(11):3681–3692. [CrossRef]

- Voorhees PM, Sborov DW, Laubach J, et al. Addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplantation-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (GRIFFIN): final analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(10):e825–e837. [CrossRef]

- Landgren CO, Yeh JC, Hillengass J, et al. Randomized, multicenter study of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) with or without daratumumab in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ADVANCE trial). J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(16 Suppl):7503. [CrossRef]

- Ogura M, Ishida T, Nomura M, et al. Efficacy of modified VRd-lite for transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):4. [CrossRef]

- Fu W, Bang SM, Huang H, et al. Bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone with or without daratumumab in transplant-ineligible Asian patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the phase 3 OCTANS study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023;23(6):446–455.e4. [CrossRef]

- Facon T, Moreau P, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed myeloma: MAIA long-term outcomes. Leukemia. 2025;39(4):942–950. [CrossRef]

- Grant SJ, Lipe B. Management of frail older adults with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma moving toward a personalized approach. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(Suppl 1):S76–S80. [CrossRef]

- Geraldes C, Roque A, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, et al. Practical management of disease-related manifestations and drug toxicities in patients with multiple myeloma. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1282300. [CrossRef]

- Wang YN, Zhang CW, Gao YX, Ge XL. The progress of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of multiple myeloma (review). Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2025;24:15330338251321349. [CrossRef]

- Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):132–147. [CrossRef]

- Garfall AL. Updated analysis of EMN02 demonstrated overall survival benefit to early ASCT for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Lee SI, Kang KS. Function of capric acid in cyclophosphamide-induced intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and barrier function in pigs. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16530. [CrossRef]

- Le D, Deau P, Roche B, et al. Thiotepa, busulfan, cyclophosphamide: effective but toxic conditioning regimen prior to autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in central nervous system lymphoma. Med Sci (Basel). 2023;11(1):14. [CrossRef]

- İlhan Ç, Suyanı E, Sucak GT, et al. Inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and antioxidant capacity in healthy allo-HSCT donors during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization. J Clin Apher. 2015;30(4):197–203. [CrossRef]

- Araki D, Chen V, Redekar N, et al. Post-transplant G-CSF impedes engraftment of gene-edited human hematopoietic stem cells by exacerbating p53-mediated DNA damage response. Cell Stem Cell. 2025;32(1):53–70.e8. [CrossRef]

- Shah G, Giralt S, Dahi P. Optimizing high-dose melphalan. Blood Rev. 2024;64:101162. [CrossRef]

- Chai RC, McDonald MM, Terry RL, et al. Melphalan modifies the bone microenvironment by enhancing osteoclast formation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(40):68047–68058. [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir G, Björkholm M, Turesson I, et al. Cumulative exposure to melphalan chemotherapy and subsequent risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2021;107(2):275–282. [CrossRef]

- Bekkem A, Selby G, Chakrabarty JH. Retrospective analysis of intravenous DMSO toxicity in transplant patients. Transplant Cell Ther. 2013;19(2 Suppl):S313. [CrossRef]

- Joseph NS, Kaufman JL, Gupta VA, et al. Quadruplet therapy for newly diagnosed myeloma: comparative analysis of sequential cohorts with triplet therapy lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (RVd) versus daratumumab with RVd (DRVd) in transplant-eligible patients. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):159. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee R, Williams L, Mikhael JR. Should I stay or should I go (to transplant)? Managing insufficient responses to induction in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):89. [CrossRef]

- Zweegman S, van de Donk NWCJ. Maintain maintenance in multiple myeloma? Blood. 2023;142(18):1501–1502. [CrossRef]

- Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, et al. Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:2997. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA–ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309–322. Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):117. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Teoh PJ, Koh MY, Mitsiades C, Gooding S, Chng WJ. Resistance to immunomodulatory drugs in multiple myeloma: the cereblon pathway and beyond. Haematologica. 2025;110(5):1074–1091. [CrossRef]

- Franqui-Machin R, Wendlandt EB, Janz S, Zhan F, Tricot G. Cancer stem cells are the cause of drug resistance in multiple myeloma: fact or fiction? Oncotarget. 2015;6(38):40496–40506. [CrossRef]

- Vijjhalwar R, Kannan A, Fuentes-Lacouture C, Ramasamy K. Approaches to managing relapsed myeloma: switching drug class or retreatment with same drug class? Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2025;41(3):478–493. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Herrera A, Sarasquete ME, Jiménez C, Puig N, García-Sanz R. Minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma: past, present, and future. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(14):3687. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee R, Cowan AJ, Ortega M, et al. Financial toxicity, time toxicity, and quality of life in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24(7):446–454.e3. [CrossRef]

- Barberio J, Lash TL, Nooka AK, Naimi AI, Patzer RE, Kim C. Real-world risk of severe cytopenias in multiple myeloma patients sequentially treated with immunomodulatory drugs. Acta Haematol. 2025;148(2):135–147. [CrossRef]

- Teh BW, Harrison SJ, Worth LJ, et al. Risks, severity and timing of infections in patients with multiple myeloma: a longitudinal cohort study in the era of immunomodulatory drug therapy. Br J Haematol. 2015;171(1):100–108. [CrossRef]

- Hong JS, Zhou B, Yee AJ, Barmettler S. Hypogammaglobulinemia and daratumumab in multiple myeloma: risk factors, infections, immunoglobulin replacement, and mortality. Blood. 2024;144(Suppl 1):3353. [CrossRef]

- Reagan MR, Rosen CJ. Navigating the bone marrow niche: translational insights and cancer-driven dysfunction. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(3):154–168. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty JA, Elder CT. Managing multiple myeloma in the face of drug-induced adverse drug reaction. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(3):500–504. [CrossRef]

- Karam K, Chebbo H, Saleh S, et al. Bortezomib-induced hepatotoxicity in a patient with multiple myeloma: a case report. Med Rep. 2024;6:100099. [CrossRef]

- Patel UH, Mir MA, Sivik JK, et al. Central neurotoxicity of immunomodulatory drugs in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep. 2015;7(1):5704. [CrossRef]

- El-Cheikh J, Moukalled N, Malard F, Bazarbachi A, Mohty M. Cardiac toxicities in multiple myeloma: an updated and deeper look into the effect of different medications and novel therapies. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):83. [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld P, Dimopoulos MA, Boccadoro M, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(4):301–313. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowiak AJ, et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) as maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(16 Suppl):7535. [CrossRef]

- Richardson P, Beksaç M, Oriol A, et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: final survival and subgroup analyses from the OPTIMISMM trial. Eur J Haematol. 2025;114(5):822–831. [CrossRef]

- Usmani SZ, Quach H, Mateos MV, et al. Final analysis of carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab vs carfilzomib and dexamethasone in the CANDOR study. Blood Adv. 2023;7(14):3739–3748. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Ding S, Zhang M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of CAR-T cell therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in China. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):701–709. [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld P, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma: overall survival results from the phase 3 CASTOR trial. Hemasphere. 2022;6(Suppl):12. [CrossRef]

- Pourrahmat MM, Kim A, Kansal AR, et al. Health state utility values by cancer stage: a systematic literature review. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(8):1275–1288. [CrossRef]

- Zayad A, Magee G, Mansour R, et al. Efficacy and safety of daratumumab, pomalidomide and dexamethasone compared to daratumumab, carfilzomib and dexamethasone in relapsed multiple myeloma: multicenter real-world experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025 Aug 27. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Lonial S, White D, et al. Elotuzumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in RRMM: final overall survival results from the phase 3 randomized ELOQUENT-2 study. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(9):91. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Dytfeld D, Grosicki S, et al. Elotuzumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: final overall survival analysis from the randomized phase II ELOQUENT-3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(3):568–578. [CrossRef]

- Yee AJ, Laubach JP, Campagnaro EL, et al. Elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2025;9(5):1163–1170. [CrossRef]

- Martin T, Dimopoulos MA, Mikhael J, et al. Isatuximab, carfilzomib, and dexamethasone in relapsed multiple myeloma: updated results from IKEMA, a randomized phase 3 study. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):72. Erratum in: Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):152. doi:10.1038/s41408-023-00923-6. [CrossRef]

- Attal M, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10214):2096–2107. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019;394(10214):2072. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32944-7. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Wang BY, Yu SH, et al. Long-term remission and survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after treatment with LCAR-B38M CAR T cells: 5-year follow-up of the LEGEND-2 trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:23. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Carvykti) indication: reimbursement recommendation [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2024 Nov. Report No.: PG0361. PMID: 39693466.

- Jagannath S, Martin TG, Lin Y, et al. Long-term (≥5-year) remission and survival after treatment with ciltacabtagene autoleucel in CARTITUDE-1 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43(25):e700–e710. [CrossRef]

- Richard S, Chari A, Delimpasi S, et al. Selinexor, bortezomib, and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone in previously treated multiple myeloma: outcomes by cytogenetic risk. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(9):1120–1130. [CrossRef]

- Sheykhhasan M, Ahmadieh-Yazdi A, Vicidomini R, et al. CAR T therapies in multiple myeloma: unleashing the future. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024;31(5):667–686. [CrossRef]

- Chekol Abebe E, Yibeltal Shiferaw M, Tadele Admasu F, Asmamaw Dejenie T. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel: the second anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapeutic armamentarium of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:991092. [CrossRef]

- Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, Puig-Saus C, Chen YY. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J Exp Med. 2024;221(2):e20230903. [CrossRef]

- Afrough A, Abraham PR, Turer L, et al. Toxicity of CAR T-cell therapy for multiple myeloma. Acta Haematol. 2025;148(3):300–314. [CrossRef]

- Jain MD, Smith M, Shah NN. How I treat refractory CRS and ICANS after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood. 2023;141(20):2430–2442. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Hu T, Wu H, et al. Prolonged haematologic toxicity in CAR-T-cell therapy: a review. J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27(23):3662–3671. [CrossRef]

- Beyar-Katz O, Rejeski K, Shouval R. Immune effector cell-associated hematotoxicity: mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. Haematologica. 2025;110(6):1254–1268. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, van den Brink MRM. Allogeneic “off-the-shelf” CAR T cells: challenges and advances. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2024;37(3):101566. [CrossRef]

- Anderson LD Jr. Idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 2022;18(3):277–289. [CrossRef]

- Munshi NC, Anderson LD Jr, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):705–716. [CrossRef]

- Hillengass J, Cohen AD, Agha ME, et al. The phase 2 CARTITUDE-2 trial: updated efficacy and safety of ciltacabtagene autoleucel in patients with multiple myeloma and 1–3 prior lines of therapy (Cohort A) and with early relapse after first-line treatment (Cohort B). Blood. 2023;142(Suppl 1):1021. [CrossRef]

- Cohen AD, Mateos MV, Cohen YC, et al. Efficacy and safety of cilta-cel in patients with progressive multiple myeloma after exposure to other BCMA-targeting agents. Blood. 2023;141(3):219–230. [CrossRef]

- Arnulf B, Kerre T, Agha M, et al. MM-505: efficacy and safety of ciltacabtagene autoleucel ± lenalidomide maintenance in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with suboptimal response to frontline autologous stem cell transplant: CARTITUDE-2 Cohort D. Lancet Haematol. 2024;[Epub ahead of print]. [CrossRef]

- Mina R, Mylin AK, Yokoyama H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following ciltacabtagene autoleucel or standard of care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2025;12(1):e45–e56. [CrossRef]

- Dytfeld D, Dhakal B, Agha M, et al. Bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRd) followed by ciltacabtagene autoleucel versus VRd followed by lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) maintenance in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma not intended for transplant: a randomized, phase 3 study (CARTITUDE-5). Blood. 2021;138(Suppl 1):1835. [CrossRef]

- Broijl A, San-Miguel J, Suzuki K, et al. EMAGINE/CARTITUDE-6: a randomized phase 3 study of DVRd followed by ciltacabtagene autoleucel versus DVRd followed by autologous stem cell transplant in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Hemasphere. 2023;7(Suppl):22–23. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, et al. Plain language summary of the KarMMa-3 study of ide-cel or standard-of-care regimens in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 2024;20(18):1221–1235. [CrossRef]

- Seyringer S, Pilz MJ, Al-Naesan I, et al. Validation of the cancer-specific utility measure EORTC QLU-C10D using evidence from four lung cancer trials covering six country value sets. Sci Rep. 2025;15:14907. [CrossRef]

- Osoba D, Zee B, Pater J, et al. Psychometric properties and responsiveness of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in patients with breast, ovarian and lung cancer. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):353–364. [CrossRef]

- Pickard AS, Ray S, Ganguli A, Cella D. Comparison of FACT- and EQ-5D-based utility scores in cancer. Value Health. 2012;15(2):305–311. [CrossRef]

- Yang SC, Kuo CW, Lai WW, et al. Dynamic changes of health utility in lung cancer patients receiving different treatments: a 7-year follow-up. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(11):1892–1900. [CrossRef]

- Harrison JP, Kim H. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status is an independent predictor of HRQoL in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A474. [CrossRef]

- Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70. [CrossRef]

- Ronquest NA, Paret K, Gould IG, Barnett CL, Mladsi DM. The evolution of ICER’s review process for new medical interventions and a critical review of economic evaluations (2018–2019). J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(11):1601–1612. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar UD, Bashir Q, Qazilbash M, Champlin RE, Ciurea SO. Fifty years of melphalan use in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(3):344–356. [CrossRef]

- Konudula RD, Gorantla CSR, Athe R. Exploring holistic healing of cancer: German New Medicine (GNM) and homeopathic treatment beyond traditional therapies. J Appl Toxicol. 2025;45(9):1669–1674. [CrossRef]

- Pawlyn C, Davies FE. Toward personalized treatment in multiple myeloma based on molecular characteristics. Blood. 2019;133(7):660–675. [CrossRef]

- Souto Filho JTD, Cantadori LO, Crusoe EQ, Hungria V, Maiolino A. Daratumumab-based quadruplet versus triplet induction regimens in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Mateos MV, Martínez-López J, Rodriguez Otero P, et al. Curative strategy for high-risk smoldering myeloma: KRd followed by transplant, KRd consolidation, and Rd maintenance. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(27):3247–3256. [CrossRef]

- Magen H, Muchtar E. Elotuzumab: the first approved monoclonal antibody for multiple myeloma treatment. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(4):187–195. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CW, Wang YN, Ge XL. Lenalidomide use in multiple myeloma (review). Mol Clin Oncol. 2023;20(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Sogbein O, Paul P, Umar M, et al. Bortezomib in cancer therapy: mechanisms, side effects, and future proteasome inhibitors. Life Sci. 2024;358:123125. [CrossRef]

- Fricker LD. Proteasome inhibitor drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;60:457–476. [CrossRef]

- Hoy SM. Pomalidomide: a review in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Drugs. 2017;77(17):1897–1908. [CrossRef]

- El Khatib HH, Abdulla K, Nassar LK, Ellabban MG, Kakaruogkas A. Advancements in multiple myeloma therapies: a comprehensive review by disease stage. Lymphatics. 2025;3(1):2. [CrossRef]

| Regimen | Patient Group | Main Advantages | Main Toxicities |

| VRd | Transplant-eligible or ineligible (standard-risk) | High response rate, prolonged PFS | Peripheral neuropathy, hematologic toxicity |

| D-VRd | Transplant-eligible | Increased MRD negativity, well tolerated | Infusion reactions, hematologic toxicity |

| KRd | Younger, fit, high-risk cytogenetics | Deeper response, increased MRD negativity | Cardiotoxicity, hypertension |

| D-KRd | Transplant-eligible, high-risk | Deep and durable MRD negativity | Cardiac and hematologic toxicity |

| D-VMP | Transplant-ineligible, elderly | OS benefit, effective in elderly | Hematologic toxicity, infections |

| D-Rd | Transplant-ineligible, frail or elderly | Long OS, oral administration convenience | Immunosuppression, hematologic toxicity |

| Rd | Frail or relapsed patients | Oral administration, convenience | Myelosuppression, fatigue |

| VRd-Lite | Elderly, frail, or comorbid | Better tolerability | Potential lower efficacy |

| Therapy | Setting/Lines | Mean OS*a | Mean PFS*a |

Cost*b USD |

QALY*c |

| Rd [23] | First Line/Frail | 57 months | 40 months | 995,924 USD | 3.6195 |

| D-Rd [23] | First Line/TIE | 70 months | 54.1 months | 1,924,803 USD | 4.434 |

| D-VRd [37,55] | First Line/TE | 159.12 months | 83.75 months | 2,184,110 USD | 9.9874 |

| VRd [37,55] | First Line/TE | 128.9 months | 37.98 months | 508,940 USD | 7.145 |

| KRd [56] | 2-5th Line | 56.9 months | 23 months | 795,518 USD | 2.608 |

| D-VMP [17,22] | First Line/TIE | 87 months | 66.7 months | 766,416 USD | 4.9778 |

| VMP [17,22] | First Line/TIE | 68 months | 42.4 months | 72,731 USD | 3.0866 |

| PVd [57] | 2-4th+ Lines | 43 months | 24 months | 633,028 USD | *d 0.7478 |

| Vd [57] | 2-4th+ Lines | 38 months | 18 months | 70,333 USD | *d 0.6727 |

| D-Kd [58,59] | 2-4th Lines | 61 months | 37 months | 2,153,071 USD | 2.103 |

| D-Vd [58,59,60,61] | 2-4+Lines | 66 months | 56 months | 611,243 USD | 1.9338 |

| D-Pd [58,59,62] | 2-4th Lines | 73 months | 32 months | 1,176,157 USD | 2.4164 |

| Kd [58,59] | 2-4th Lines | 55 months | 20 months | 935,796 USD | 1.7618 |

| Elo-Rd [63] | 2-4th Lines | 47.1 months | 31 months | 995,764 USD | 0.9655 |

| Elo-Pd [64] | 3-5th+ Lines | 34 months | 22 months | 835,752 USD | 0.8139 |

| Elo-PVd [65] | 2-10th Lines | 35 months | 18 months | 700,628 USD | 0.875 |

| Isa-Kd [58,66] | 2-4th Lines | 54 months | 34 months | 1,700,907 USD | 2.511 |

| Isa-Pd [67] | 3+ Lines | 38 months | 23.3 months | 907,989 USD | 0.95 |

| CAR-T Legend-2 [68,69] | 4+ Lines | 54 months+ | 30 months | 640,000 USD | 1.7433 |

| CARTITUDE-1 [69,70] | 4+ Lines | 85 months+ | 43.85 months | 640,000 USD | 2.7384 |

| X-Vd [71] | 2-4th Lines | 34.98 months | 18.5 | 839,679 USD | 1.575 |

| Study Name | Phase / Design | Patient Profile | Treatment Line | Regimen / Comparator | Key Message |

| LEGEND-2 (NCT03090659) [68] | Phase 1, open-label, single-arm | ≥3 prior lines (PI + IMiD-treated RRMM) | 4+ line | LCAR-B38M single infusion | First-in-human BCMA-CAR-T; deep and durable responses |

| CARTITUDE-1 (NCT03548207) [70] | Phase 1b/2, multicenter | ≥3 prior lines (PI + IMiD + anti-CD38) | 4+ line | Cilta-cel single infusion | Global validation; high depth and long PFS |

| CARTITUDE-2 (NCT04133636) | Phase 2, multi-cohort | Cohorts A-E: RRMM, len-refractory, 1-3 prior lines | 2nd–3rd line | Cilta-cel single infusion | High efficacy maintained in early-line settings |

| CARTITUDE-4 (NCT04181827) [85] | Phase 3, global | 1–3 prior lines, len-refractory | 2nd–3rd line | Cilta-cel vs PVd / DPd | Phase 3 confirmation of superiority vs SOC |

| CARTITUDE-5 (NCT04923893) [86] | Phase 3 (ongoing) | Newly diagnosed, transplant ineligable | 1st line | VRd+Cilta-cel vs VRd+Rd maintenance | CAR-T as potential maintenance alternative in frontline |

| CARTITUDE-6 (NCT05257083) [87] | Phase 3, comparative | Newly diagnosed, transplant-eligible | 1st line | D-VRd+Cilta-cel + Lenalidomide vs D-VRd+ASCT+DVRd+Lenalidomide | Immune-regenerative CAR-T as ASCT replacement |

| KarMMa-1 (NCT03361748) [13] | Phase 2, single-arm | ≥3 prior lines RRMM | 4+ line | Ide-cel (bb2121) | First approved BCMA-CAR-T (US) |

| KarMMa-3 (NCT03651128) [88] | Phase 3, randomized | 2nd–4th line | - | Ide-cel vs SOC | Ide-cel effective but with shallower depth of response |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).