Introduction

Primary lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide and is the leading cause of cancer-related death.[

1,

2] Despite increasing efforts to detect and treat lung cancer early,[

3,

4] most lung cancer patients are still diagnosed in advanced tumor stages especially due to the frequent lack of specific symptoms in early disease.[

5]

Over the past ten years, the clinical practice in treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has improved significantly, leading to considerably longer survival.[

6] Next to targeted therapy in specific genetically determined patient groups, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy (CHT) represents the current therapeutic first-line standard for most advanced NSCLC patients.[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]

Median progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) according to long-term data in the era of first-line ICI therapy has been reported between around 6-11 and 16-26 months (M), respectively, depending on histology, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression level, and concomitant use of bevacizumab. In the CHT comparator arms, PFS and OS ranged from 4-7 and 11-15M, respectively.[

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] In comparison, studies on first-line chemotherapy from the pre-ICI era indicated PFS and OS of around 4-6M and 8-12M.[

19,

20,

21,

22]

However, the successful adoption of ICI therapies as standard treatment came with significant costs, with single dose prices ranging from 4,000 to 11,000€, depending on time, country-specific factors, and reimbursement models. For example, calculations based on the Impower 110 study on Atezolizumab versus CHT reported a gain of 0.87 quality adjusted life years (QALYs), leading to a cost of

$123,424/QALY.[

23] Similarly, comparing Atezolizumab (IMpower 110) vs. Pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE 024 and 042) in the Spanish healthcare system as of 2020, a study reported 1.43 and 1.61 QALYs in PFS for Atezolizumab and Pembrolizumab, respectively, with total therapy cost of €149,213€ and €227,894€ and total healthcare cost of €172,861 and €254,769 respectively.[

24] Concerning Pembrolizumab treatment and calculations based on US data, the addition of ICI to chemotherapy resulted in additional 0.78 QALYs at an incremental cost of

$151,409, resulting in an incremental cost-efficacy ratio of

$194,372/QALY.[

25]

As compared to CHT, ICI therapies are typically administered over longer time and - despite predictive biomarkers like PD-L1 expression and mutational status are available - response on the individual patients’ level is still hard to foresee.[

26,

27]

We aimed to assess the real-life benefit and costs of first line Pembrolizumab treatment in advanced NSCLC in an institutional lung cancer registry cohort, as compared to a historical matched cohort of patients receiving first-line CHT from the pre-ICI era.

Patients and Methods

Data of patients treated with Pembrolizumab were retrieved from the institutional retrospective lung cancer immunotherapy registry. Patients were included in this analysis if they had received at least one cycle of first line Pembrolizumab therapy alone or in combination with a platinum-based doublet CHT between 2017 and 2021 at the Department of Pulmonology of the Kepler University Hospital in Linz, Austria, for stage IV or not otherwise treatable stage III NSCLC. Patients with targetable oncogenic driver mutations were excluded. The historical CHT-treated controls were derived from the institutional lung cancer registry starting in 2011, whereas patients were selected when they had received at least one cycle of platinum-based doublet CHT in the aforementioned indication between 2011 and 2014. Patients with targetable driver mutations were excluded, as well as patients who had received ICI therapy in later therapy lines.

The patient registry and the current analysis were approved by the Ethics Committee of Upper Austria (EC No. 1139/2019), the need for patients’ informed consent was waived due to the entirely non-interventional and retrospective approach. Patients were retrospectively followed from therapy initiation on to death or censored to the date of last verified contact before the data cut at the end of 2020.

In the historical chemotherapy cohort, according to the institutional standard, patients routinely received four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy using Pemetrexed for adenocarcinomas, not otherwise specified (NOS-)NSCLC and large cell carcinomas, and Gemcitabine for squamous cell carcinomas,[

21] together with Carbo- or Cisplatin according to the treating physician’s choice. Maintenance therapy with Pemetrexed or Gemcitabine could be administered until progression or toxicity warranting withdrawal.

Patients in the ICI-CHT cohort similarly received the same CHT backbone therapy for non-squamous tumors,[

7] but paclitaxel for squamous histology according to the respective underlying trials.[

28] Patients with a PD-L1 expression of ≥50% were eligible for receiving either mono-ICI therapy with Pembrolizumab or a combination of CHT and Pembrolizumab at the discretion of the treating physician. CHT-ICI therapy was routinely administered for four cycles if tolerated by the patient, followed by ICI and – optionally – Pemetrexed or Gemcitabine maintenance until disease progression or occurrence adverse events warranting withdrawal of therapy. Upon radiographic progression, immunotherapy could be resumed in selected cases with significant clinical benefit as treatment beyond progression, or if local treatment of limited progression, e.g. by radiotherapy, was possible. Also, an earlier switch to ICI maintenance therapy could be performed in case of unacceptable CHT-induced toxicity.

In both cohorts, clinical and radiological follow-up was performed routinely after two cycles of ICI-CHT combination or CHT alone, or three cycles of Pembrolizumab monotherapy or CHT maintenance, equaling intervals of two to three months. Routinely, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and the upper abdomen using iodized contrast medium was obtained, additional imaging such as magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) for follow-up of known cerebral metastases, or 18F-FDG-PET/CT could be performed when deemed necessary by the treating physician. Upon symptoms suggesting disease progression and therapy-associated side effects, re-staging could be preponed.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.2;

www.r-project.org). Descriptive statistics like mean and standard deviation were used for continuous variables, counts with percentages were used for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed with the Fisher's exact test and with the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were respectively assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method. For statistical analysis between the groups, the log-rank test was performed. We conducted both univariate and multivariate analyses for predictive factors towards PFS and OS based on the Cox proportional hazards models, using each of the potential predictors as independent variables and progression/survival as the dependent variable. Results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). An alpha error was set at 0.05.

As our analysis aimed to compare two treatments for advanced NSCLC, propensity-score matching between the groups was performed: To find statistical "twins" for each of the observations in the ICI cohort, logistic regression with age, sex, ECOG and histology as independent variables and the respective cohort dataset as dependent variable was performed. This enabled obtaining an estimation for the propensity score, according to which each observation of the ICI dataset was matched with one of the "chemotherapy-dataset". The R-package "matchit" was used for the matching process.

Cost Calculation

We calculated the therapy costs for the two cohorts according to the average costs of the respective medications as recorded by the Kepler University Hospital pharmaceutical department for the respective time intervals between 2011-2014 and 2015-2020, respectively. The costs per cycle of therapy for both groups were multiplied with the number of cycles per patient and summed up at the end to determine the total costs per cohort. Furthermore, costs per patient were calculated as incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) per month of median OS gained.

Results

Ninety-three patients of the first-line ICI cohort and 106 patients of the historical CHT cohort met the requirements to be included in our study. Ninety-three patients of the latter cohort were then matched for comparison. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

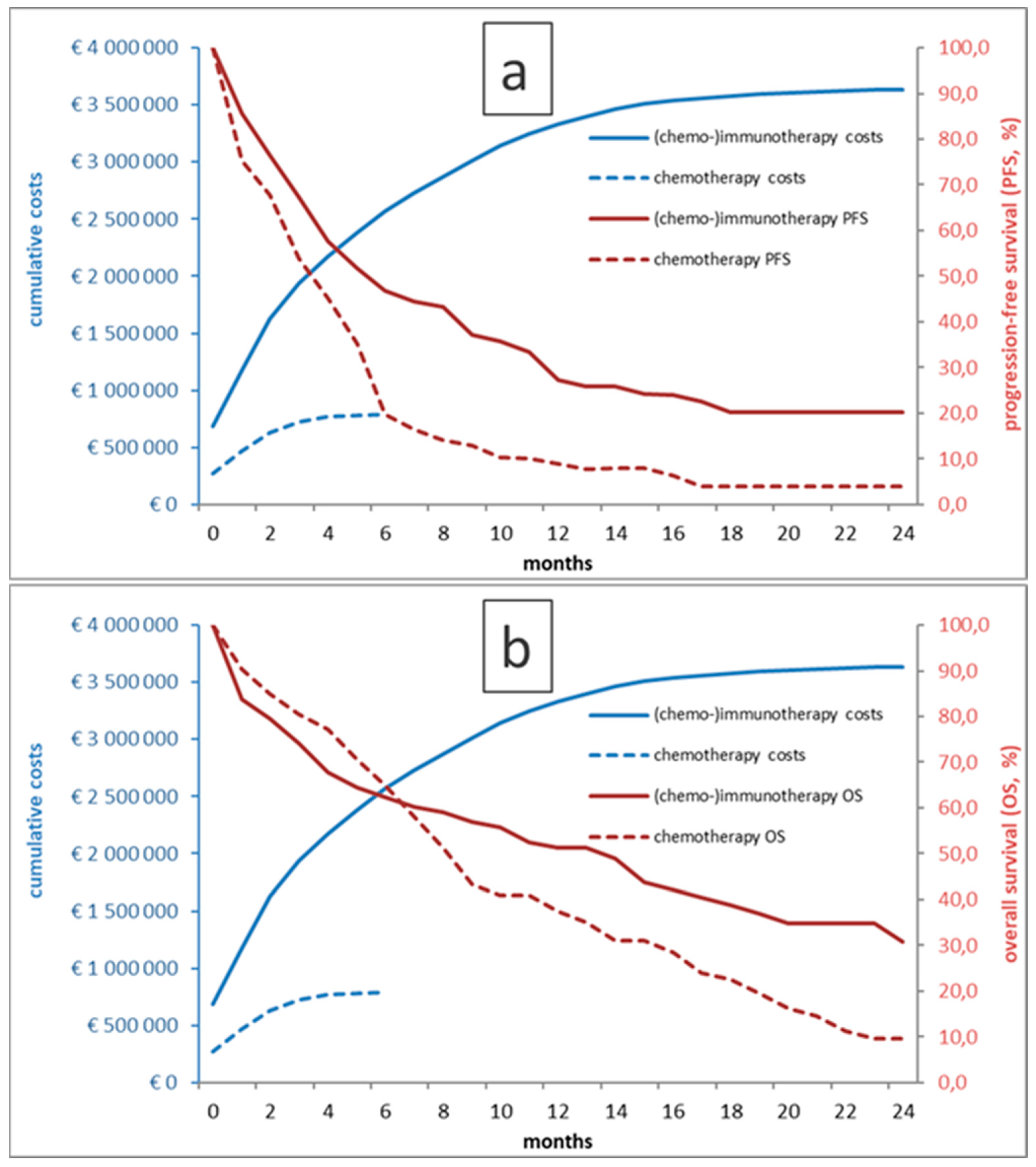

As shown in figure 1, patients treated with first-line Pembrolizumab had a longer (p<0.001) median PFS of 6M (95% confidence interval (CI) 4-9), as compared to 4M (95%CI 3-5) in the historical CHT group. Similarly, median OS was significantly longer in the ICI group (14M (95% CI 8-19) vs. 8M (95% CI 7-10); p=0.01). Of interest, the OS curves crossed at approximately 6M, indicating excess mortality in patients undergoing ICI in the first half year.

In regression analyses, there were no significant multivariate prognostic variables for progression in the CHT cohort, while the only significant variable in the ICI cohort was lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). For survival, there were significant multivariate interactions with C-reactive protein (CRP) in the CHT cohort and with Eastern Co-operative of Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and LDH in the ICI cohort.

Table 2.

Uni- and multivariate analyses for progression and survival in the matched chemo- and immunotherapy cohorts, respectively.HR=hazard ratio, ECOG=Eastern Co-operative of Oncology Group, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, CRP=C-reactive protein, PD-L1=programmed death-ligand 1.

Table 2.

Uni- and multivariate analyses for progression and survival in the matched chemo- and immunotherapy cohorts, respectively.HR=hazard ratio, ECOG=Eastern Co-operative of Oncology Group, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, CRP=C-reactive protein, PD-L1=programmed death-ligand 1.

| |

Chemotherapy cohort 2011-2014 (n=93) |

Immunotherapy cohort 2014-2020 (n=93) |

| |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

| |

HR (95% CI) |

P |

HR (95% CI) |

P |

HR (95% CI) |

P |

HR (95% CI) |

p |

| Progression free survival |

| Sex (male vs. female) |

1.19 (0.75-1.88) |

0.463 |

|

|

0.81 (0.50-1.31) |

0.384 |

|

|

| Age (≥ 70 vs. < 70 years) |

0.91 (0.56-1.44) |

0.669 |

|

|

1.19 (0.70-2.03) |

0.517 |

|

|

| ECOG (2+ vs. 0,1) |

1.56 (0.97-2.51) |

0.067 |

|

|

1.64 (0.87-3.08) |

0.126 |

|

|

| Histology (adeno vs. not adeno) |

1.51 (0.92-2.46) |

0.106 |

|

|

1.09 (0.63-1.89) |

0.768 |

|

|

| Packyears (≥5 vs. <5) |

0.90 (0.44-1.89) |

0.778 |

|

|

0.56 (0.22-1.41) |

0.215 |

|

|

| LDH ((≥250 vs. <250U/L) |

1.51 (0.82-2.79) |

0.191 |

|

|

2.28 (1.36-3.84) |

0.002 |

2.28 (1.36-3.84) |

0.001 |

| CRP (≥0.5 vs. <0.5mg/dL) |

1.34 (0.83-2.16) |

0.232 |

|

|

1.41 (0.79-2.51) |

0.245 |

|

|

| Lymphocytes (≥1 vs. <1G/L) |

0.96 (0.60-1.53) |

0.855 |

|

|

1.20 (0.73-1.98) |

0.478 |

|

|

| PD-L1 status (neg. vs. Pos.) |

- |

|

- |

|

1.09 (0.66-1.82) |

0.736 |

- |

|

| Overall survival |

| Sex (male vs. female) |

1.49 (0.91-2.46) |

0.115 |

|

|

1.00 (0.59-1.71) |

0.995 |

|

|

| Age (≥70 vs. <70 years) |

1.05 (0.64-1.73) |

0.843 |

|

|

1.35 (0.76-2.40) |

0.298 |

|

|

| ECOG (2+ vs. 0,1) |

2.14 (1.28-3.58) |

0.004 |

|

|

2.51 (1.35-4.64) |

0.004 |

2.04 (1.02-4.08) |

0.043 |

| Histology (adeno vs. not adeno) |

1.26 (0.75-2.13) |

0.389 |

|

|

1.48 (0.83-2.63) |

0.182 |

|

|

| Packyears (≥5 vs. <5) |

0.85 (0.39-1.85) |

0.676 |

|

|

0.86 (0.31-2.36) |

0.758 |

|

|

| LDH (≥250 vs. <250U/L) |

1.34 (0.71-2.56) |

0.370 |

|

|

3.21 (1.36-7.60) |

0.008 |

1.97 (1.10-3.55) |

0.023 |

| CRP (≥0.5 vs. <0.5mg/dL) |

1.87 (1.10-3.18) |

0.021 |

1.87 (1.10-3.18) |

0.021 |

2.19 (1.07-4.49) |

0.032 |

|

|

| Lymphocytes (≥1 vs. <1G/L) |

0.87 (0.52-1.45) |

0.595 |

|

|

0.86 (0.51-1.46) |

0.582 |

|

|

| PD-L1 status (neg. vs. Pos.) |

- |

|

- |

|

1.23 (0.72-2.10) |

0.458 |

- |

|

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS (a) and OS (b) for chemo- and immunotherapy-treated patients as well as respective cumulative treatment costs over time.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS (a) and OS (b) for chemo- and immunotherapy-treated patients as well as respective cumulative treatment costs over time.

According to our cost-benefit analysis, the total treatment costs in the (chemo-)ICI group amounted to 3,635,572€. Mean costs per patient were 39,092€ (SD 30,476€). In contrast, the total costs in the CHT group were 867,000€; mean costs per patient were 8,179€ (SD 5,624€)). ICER per month of median OS gained was €5,152.

Discussion

Our analyses showed a clear PFS and OS benefit of ICI therapy with Pembrolizumab over platinum-based CHT alone in a historical cohort. However, we also found excess mortality in the ICI cohort in the initial months, as well as markedly higher treatment costs.

The administration of first-line Pembrolizumab, either as combination with CHT or as monotherapy, could significantly prolong both median PFS and OS, by 2M and 6M, respectively. These figures confirm the reported phase 3 trial results of KEYNOTE-024, -189, and -407, which all found a clear survival benefit with the use of Pembrolizumab as compared to CHT therapy. Also, our presented historical CHT-cohort showed similar PFS and OS results as reported in historical trials, for example in the ECOG trial published in 2002, with a median OS of 8M in our study.[

20,

29]

A major finding that warrants discussion in the results is the crossing of the Kaplan-Meier OS curves (figure 1) at 6M. This finding implies that there was excess mortality in the (CHT-)ICI group as compared to the historical CHT control group, although overall OS showed superiority of ICI therapy in the end with a plateau in the OS curve indicating long-term survival in a minority of patients. The two cohorts were well matched with significant differences only in terms of a lower lymphocyte count and higher LDH in the ICI group, which may imply a higher systemic inflammatory state in these patients. Otherwise however, as most ICI-treated patients received concomitant CHT, and as the CHT substances used as well as application strategies did not change significantly in the meantime, it is likely that this observed effect was not caused by baseline biomarkers or the treatment itself, but rather by patient selection and oncological management. In the CHT era, patient selection according to performance status and comorbidities was more relevant due to the lack of alternatives to CHT. In the ICI era, especially with the option of ICI monotherapy with generally less side effects as compared to CHT, the decision for medical treatment over best supportive care may have become more liberal and this might have led to overtreatment in patients showing no survival benefit in the end. Thus, the finding that our cohort of first-line ICI patients did not experience a prognostic benefit from ICI treatment in the first six months of treatment clearly warrants a more efficient patient selection, ideally based on widely available biomarkers. In multivariate analyses, LDH>250 had significant implications on progression and survival in the ICI cohort, in addition to ECOG PS ≥2 for OS. In the CHT cohort, there were no significant uni- and multivariate results for PFS, and an interaction of elevated CRP with increased mortality only. The utility of LDH as a prognostic factor regarding outcomes in ICI therapy of NSCLC is well known as shown by Peng et al. and Taniguchi et al., who reported that LDH ≤240 U/L in ICI-treated NSCLC was associated with better survival.[

27,

30,

31] Pretreatment ECOG status and high CRP have also been extensively reported as prognostic biomarkers in NSCLC patients.[

32,

33] In contrast to other published data, our study did not find a significant interaction of outcomes with PD-L1 status in the ICI group. However, most patients received CHT-ICI combinations, and large Phase-III trials on such combination treatments similarly showed consistent efficacy across all PD-L1 subgroups.[

7]

Not only the type of therapy changed dramatically in the past decades, but so did therapy costs. According to our cost-benefit analysis, the total costs in the (CHT-)ICI group amount to 3,635,572€ as compared to 867,000€ for CHT. The ICER for one months of OS was €5,152, which can be extrapolated to €61,826 per year of OS, without adjustments for quality of life and irrespective of other healthcare cost, as these data were not available in our dataset. These figures are in line with similar observations from France for patients with PD-L1>50%,[

34] where an ICER of €66,825 per life year and €84,097/QALY were reported as likely cost-efficient assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold at 100,000€/QALY. Still, in our cohort, reflecting the crossing of the OS curves with no OS benefit in the first 6 months of therapy, the additional cost of ICI treatment appears enormous and equity in healthcare allocation is an ongoing and eagerly debated issue.

Our analyses and the reported results have several strengths and limitations: Using propensity score matching of two cohorts fully evaluated and treated at the same center, by largely the same medical team and using very similar CHT regimens, our analyses offer a good estimation of the real-life effects of the introduction of first-line ICI treatment, together with its costs. Still, the development in cancer diagnostics and treatment, as well as in supportive management has been rapidly evolving in the recent years and this likely has caused imbalances between the two groups that could not be fully accounted for by propensity score matching. The case numbers of both cohorts are comparably low, so that 1:1 matching was used, which means that there might be limitations in applying the results to larger populations. Additionally, due to the retrospective study design, we could neither include the cost of comedication, hospitalizations, or treatment of complications, but only the true medication costs of the evaluated anticancer therapies. Additionally, these are difficult to compare internationally due to national regulations and health system-dependent variability, as well as site-specific consideration such as reimbursement models like pay-for-performance or discounts. However, within those limitations, we found very comparable costs as also reported by other European groups.[

24,

34] Furthermore, we could not provide quality of life data, which makes comparability with other, more elaborate cost-efficacy analyses difficult. It should be emphasized that the mere prolongation of the survival time does not allow to draw conclusions about the patient’s physical and mental condition during this time.

We conclude that in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with first-line Pembrolizumab in a single-center retrospective cohort, results paralleled the data published in the respective phase III trials. Patients had significantly longer PFS and OS as compared to historical cohorts of propensity score matched first line CHT patients. However, there was excess mortality of first-line ICI-treated patients as compared to CHT patients in the first six months of therapy and the therapeutic benefit of ICI in further course of treatment went along with considerably higher treatment costs. However, rather than saving money by denying patients effective therapies, more resources should be allocated to the development of evidence-based biomarker and decision-support tools , as well as to early detection and smoking cessation and prevention programs.

Author Contributions

All authors have made significant contributions to this manuscript and meet the criteria for authorship as established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the local ethics committees of Upper-Austria (EK Nr. 1139/2019). It was conducted in an entirely retrospective fashion, without an experimental approach or additional patient contact. Only patient data assessed in clinical routine were analyzed. Patient data were collected in an anonymized fashion and securely electronically stored in a way, that only the authors had access to the data.

Informed Consent Statement

The need for patients’ written informed consent was waived according to the institutional ethics committee’s regulations for non-interventional retrospective studies.

Data Availability Statement

According to the terms imposed by the ethics committee, the full datasets analyzed during the current study cannot be made publicly available, as they contain possibly identifiable patient data. Upon reasonable request to the authors and if approved as an amendment by the institutional committee, selected anonymized data can however be shared.

Conflicts of interest

VP and AH have received travel/accommodation funding from Roche and Merck Sharp & Dohme. RW has received speakers’ honoraria and travel/accommodation funding from and served as consultant/advisor to Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bristol-Myers Squibb. BL has received speakers’ honoraria from and has served as consultant/advisor to Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bristol-Myers Squibb. DL has served as consultant/advisor to and received travel/accommodation funding from Roche and Merck Sharp & Dohme. LF and BK declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, L.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.S.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Solomon, B.J.; et al. Non-Oncogene-Addicted Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Annals of Oncology 2023, 34, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365, 395–409. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, H.J.; van der Aalst, C.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.-W.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, P.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hui, Z.; Liu, S.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; et al. What Are the Clinical Symptoms and Physical Signs for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer before Diagnosis Is Made? A Nation-wide Multicenter 10-year Retrospective Study in China. Cancer Med 2019, 8, 4055–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlader, N.; Forjaz, G.; Mooradian, M.J.; Meza, R.; Kong, C.Y.; Cronin, K.A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Lowy, D.R.; Feuer, E.J. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gümüş, M.; Mazières, J.; Hermes, B.; Çay Şenler, F.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.S.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Solomon, B.J.; et al. Non-Oncogene-Addicted Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Annals of Oncology 2023, 34, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab Combined with Two Cycles of Chemotherapy in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CheckMate 9LA): An International, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassino, M.C.; Gadgeel, S.; Speranza, G.; Felip, E.; Esteban, E.; Dómine, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; Bischoff, H.G.; Peled, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novello, S.; Kowalski, D.M.; Luft, A.; Gümüş, M.; Vicente, D.; Mazières, J.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Tafreshi, A.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50%. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.G.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Cobo, M.; Bennouna, J.; Schenker, M.; Cheng, Y.; Juan-Vidal, O.; Mizutani, H.; Lingua, A.; Reyes-Cosmelli, F.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab With Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone for Metastatic NSCLC in CheckMate 9LA: 3-Year Clinical Update and Outcomes in Patients With Brain Metastases or Select Somatic Mutations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2023, 18, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socinski, M.A.; Nishio, M.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; et al. IMpower150 Final Overall Survival Analyses for Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy in First-Line Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2021, 16, 1909–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassem, J.; de Marinis, F.; Giaccone, G.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Oprean, C.; Kim, Y.-C.; Andric, Z.; et al. Updated Overall Survival Analysis From IMpower110: Atezolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Treatment-Naive Programmed Death-Ligand 1–Selected NSCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2021, 16, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Chiodini, P.; Sun, J.-M.; O’Brien, M.E.R.; von Plessen, C.; Barata, F.; Park, K.; Popat, S.; Bergman, B.; Parente, B.; et al. Six versus Fewer Planned Cycles of First-Line Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Lancet Oncol 2014, 15, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.H.; Harrington, D.; Belani, C.P.; Langer, C.; Sandler, A.; Krook, J.; Zhu, J.; Johnson, D.H. Comparison of Four Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2002, 346, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.V.; Parikh, P.; Von Pawel, J.; Biesma, B.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Manegold, C.; Serwatowski, P.; Gatzemeier, U.; Digumarti, R.; Zukin, M.; et al. Phase III Study Comparing Cisplatin plus Gemcitabine with Cisplatin plus Pemetrexed in Chemotherapy-Naive Patients with Advanced-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socinski, M.A.; Bondarenko, I.; Karaseva, N.A.; Makhson, A.M.; Vynnychenko, I.; Okamoto, I.; Hon, J.K.; Hirsh, V.; Bhar, P.; Zhang, H.; et al. Weekly Nab -Paclitaxel in Combination With Carboplatin Versus Solvent-Based Paclitaxel Plus Carboplatin as First-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Final Results of a Phase III Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012, 30, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Pei, R.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Tang, L.; Yin, T.; Liu, S. Atezolizumab Compared to Chemotherapy for First-Line Treatment in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with High PD-L1 Expression: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis from US and Chinese Perspectives. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1481–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isla, D.; Lopez-Brea, M.; Espinosa, M.; Arrabal, N.; Pérez-Parente, D.; Carcedo, D.; Bernabé-Caro, R. Cost-Effectiveness of Atezolizumab versus Pembrolizumab as First-Line Treatment in PD-L1-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Spain. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2023, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wan, X.; Peng, L.; Peng, Y.; Ma, F.; Liu, Q.; Tan, C. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Previously Untreated Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the USA. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodor, J.N.; Boumber, Y.; Borghaei, H. Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Cancer 2020, 126, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, L.; Lopes, S.; Bertrand, B.; Creusot, Q.; Kotovskaya, M.; Pencreach, E.; Beau-Faller, M.; Mascaux, C. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in the Era of Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gümüş, M.; Mazières, J.; Hermes, B.; Çay Şenler, F.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.V.; Parikh, P.; Von Pawel, J.; Biesma, B.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Manegold, C.; Serwatowski, P.; Gatzemeier, U.; Digumarti, R.; Zukin, M.; et al. Phase III Study Comparing Cisplatin plus Gemcitabine with Cisplatin plus Pemetrexed in Chemotherapy-Naive Patients with Advanced-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Qian, X.; Li, Y. Peripheral Blood Markers Predictive of Outcome and Immune-Related Adverse Events in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with PD-1 Inhibitors. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2020, 69, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Tamiya, A.; Isa, S.-I.; Nakahama, K.; Okishio, K.; Shiroyama, T.; Suzuki, H.; Inoue, T.; Tamiya, M.; Hirashima, T.; et al. Predictive Factors for Poor Progression-Free Survival in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Nivolumab. Anticancer Res 2017, 37, 5857–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, J.M.; Barth, D.A.; Brueckl, W.M.; Zeitler, G.; Foris, V.; Mollnar, S.; Stotz, M.; Rossmann, C.H.; Terbuch, A.; Balic, M.; et al. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Levels in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response and Progression in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Bi-Center Study. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, K.; Gill, R.R.; Widick, P.; Bindal, P.; McDonald, D.C.; Shea, M.; Rangachari, D.; Costa, D.B. Association of Performance Status With Survival in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Pembrolizumab Monotherapy. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2037120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouaid, C.; Bensimon, L.; Clay, E.; Millier, A.; Levy-Bachelot, L.; Huang, M.; Levy, P. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Pembrolizumab versus Standard-of-Care Chemotherapy for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1 Positive (>50%) Metastatic Squamous and Non-Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in France. Lung Cancer 2019, 127, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics in the (chemo-)immunotherapy cohort as well as in the chemotherapy cohort, with all patients and in the propensity-score matched cohort. The p-value is for comparison between the two matched cohorts. SD=standard deviation, ECOG=Eastern Co-operative of Oncology Group, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, CRP=C-reactive protein, py=pack years, IQR=interquartile range, PD-L1=programmed death-ligand 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics in the (chemo-)immunotherapy cohort as well as in the chemotherapy cohort, with all patients and in the propensity-score matched cohort. The p-value is for comparison between the two matched cohorts. SD=standard deviation, ECOG=Eastern Co-operative of Oncology Group, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, CRP=C-reactive protein, py=pack years, IQR=interquartile range, PD-L1=programmed death-ligand 1.

| |

Pembrolizumab (n=93) |

Chemotherapy matched (n=93) |

p-value |

Chemotherapy all patients (n=106) |

| Patient characteristics (%) |

| Male sex |

60.2 |

67.7 |

n.s. |

67.9 |

| Age (mean, SD) |

65.3 (8.7) |

64.6 (9.9) |

n.s. |

63.9 (9.8) |

| Age <60 |

31.2 |

38.7 |

n.s. |

29.0 |

| Age 60-69 |

41.9 |

33.3 |

38.7 |

| Age 70+ |

26.9 |

28.0 |

32.3 |

| ECOG 0,1 |

81.7 |

73.1 |

n.s. |

74.5 |

| ECOG 2+ |

18.3 |

26.9 |

25.5 |

| Former or current smokier (≥5py) |

92.5 |

88.2 |

n.s. |

86.8 |

| Never smoker (<5py) |

7.5 |

11.8 |

13.2 |

| Laboratory biomarkers |

| LDH (U/L; mean, SD) |

322 (583) |

217 (120) |

0.017 |

216 (119) |

| CRP (mg/L; mean, SD) |

2.9 (5.1) |

3.0 (3.6) |

n.s. |

3.0 (3.5) |

| Neutrophil count (G/L; mean, SD) |

8.5 (4.5) |

8.4 (3.6) |

n.s. |

8.4 (3.5) |

| Lymphocyte count (G/L; mean, SD) |

1.3 (0.8) |

1.6 (0.8) |

0.024 |

1.7 (1.1) |

| Tumor characteristics (%) |

| Adenocarcinoma |

73.1 |

74.2 |

n.s. |

73.6 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

25.8 |

18.3 |

17.9 |

| Other histology |

1.1 |

7.5 |

8.5 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles (median, IQR) |

3 (3) |

4 (2) |

n.a. |

4 (2) |

| Number of immunotherapy cycles (median, IQR) |

5 (8) |

- |

n.a. |

- |

| PD-L1 – positive |

58.1 |

- |

n.a. |

- |

| PD-L1 – negative |

36.6 |

- |

- |

| PD-L1 - status missing |

5.4 |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).