1. Introduction

As human assisted reproductive technologies evolve, new approaches to improve infertility treatment are emerging. These include mitochondrial replacement therapy, which is used to prevent mitochondrial diseases [

1,

2], and restoration of normal ploidy in triploid zygotes [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Mitochondrial replacement therapy involves nuclear transfer between oocytes or zygotes and can be performed as a germinal vesicle (GV) transfer, metaphase II (MII) spindle transfer and pronuclear (PN) transfer. Ploidy normalization in triploid zygotes, in addition to the task of obtaining embryos with normal ploidy [

5], also serves to obtain diploid human embryonic stem cells [

7,

8]. Furthermore, pronuclear removal is also required for pronuclear transfer in human oocytes [

9].

Both these approaches involve the removal of genetic material or part of it from the egg (enucleation). In the case of zygotes, removal of the pronucleus is sometimes referred to as epronucleation [

6,

10]. Currently, enucleation (epronucleation) is performed only by aspiration using a microneedle. During aspiration, the oocyte is inevitably punctured, and part of the cytoplasm is removed along with the metaphase plate or pronucleus. In addition, oocytes are cultured with cytoskeletal inhibitors (cytochalasin B, demecolcine or colcemid) before enucleation [

1,

3,

6].

For the clinical approaches, the invasiveness is of key importance, since it is the factor that largely determines the success of the procedures performed. Currently, lasers are often applied for the oocyte and embryo manipulation. Due to high-precision focusing, lasers are able to act locally inside a living object without damaging the surrounding material [

11]. In the field of reproductive technologies, lasers are routinely used for assisted hatching, embryo biopsy, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, cryopreservation and sperm immobilization/selection [

12,

13].

Using near-infrared ultrashort lasers to remove genetic material in oocytes offers great advantages. A key advantage of laser enucleation over aspiration is the ability to retain all intracellular compartments. Besides, when using the laser, it is not necessary to puncture the oocyte and apply cytoskeletal inhibitors. Previously, we have demonstrated the fundamental possibility of DNA destruction in human oocytes at the metaphase II stage [

14], and the potential for pronuclei destruction in mouse zygotes [

15]. We have also demonstrated the low-invasive effect of the laser on mouse oocytes [

16]. The combination of effectiveness and low-invasiveness becomes possible due to non-linear nature of femtosecond laser absorption by biological material. Absorption occurs only in the region of highest laser intensity (laser focal spot), enabling highly localized action. Nonlinear adsorption of femtosecond laser action results in highly localized formation of low-density plasma [

17]. The interaction between the low-density plasma and biological material leads to the desired localized DNA breakdown [

18].

In this work, we demonstrated the pronucleus destruction in triploid human zygotes by a 1033 nm femtosecond laser. Moreover, we studied the viability of treated and control zygotes by observing cleavage and specific apoptosis staining.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oocyte Collection, Cryopreservation, Vitrification and Culturing

Three-pronuclear zygotes were obtained by IVF: normally, they are not used in ART programs and are disposed of as biological waste. These zygotes were collected and pre-frozen for storage in liquid nitrogen. Freezing and thawing were performed using the Kitazato Kit (91121, Kitazato Corporation) according to the manufacturer's standard protocol. After thawing, 8 of the 12 samples had 3 pronuclei, 2 had 2 pronuclei, and 2 had no pronuclei. Zygotes with two pronuclei and samples without pronuclei were used for preliminary experiments to select the laser parameters.

Zygotes were cultured in a 5-well culture dish (16004, Vitrolife) with G-TL culture medium (10145, Vitrolife) covered with Ovoil Heavy (10174, Vitrolife). The dish was prepared 16 hours before use. An atmosphere of 5% O2 and 6% CO2 was used for dish preparation and cultivation of oocytes, zygotes and embryos. Development was assessed the day after exposure (the second day of development, when two-cell embryos should be present) and 4 days later (the fifth day of development, when blastocysts are typically observed). Embryo quality and development were determined according to the Spanish Association of Reproduction Biology Studies (ASEBIR) criteria.

2.2. Laser Parameters and Pronuclear Irradiation

A detailed description of the experimental setup is given in [

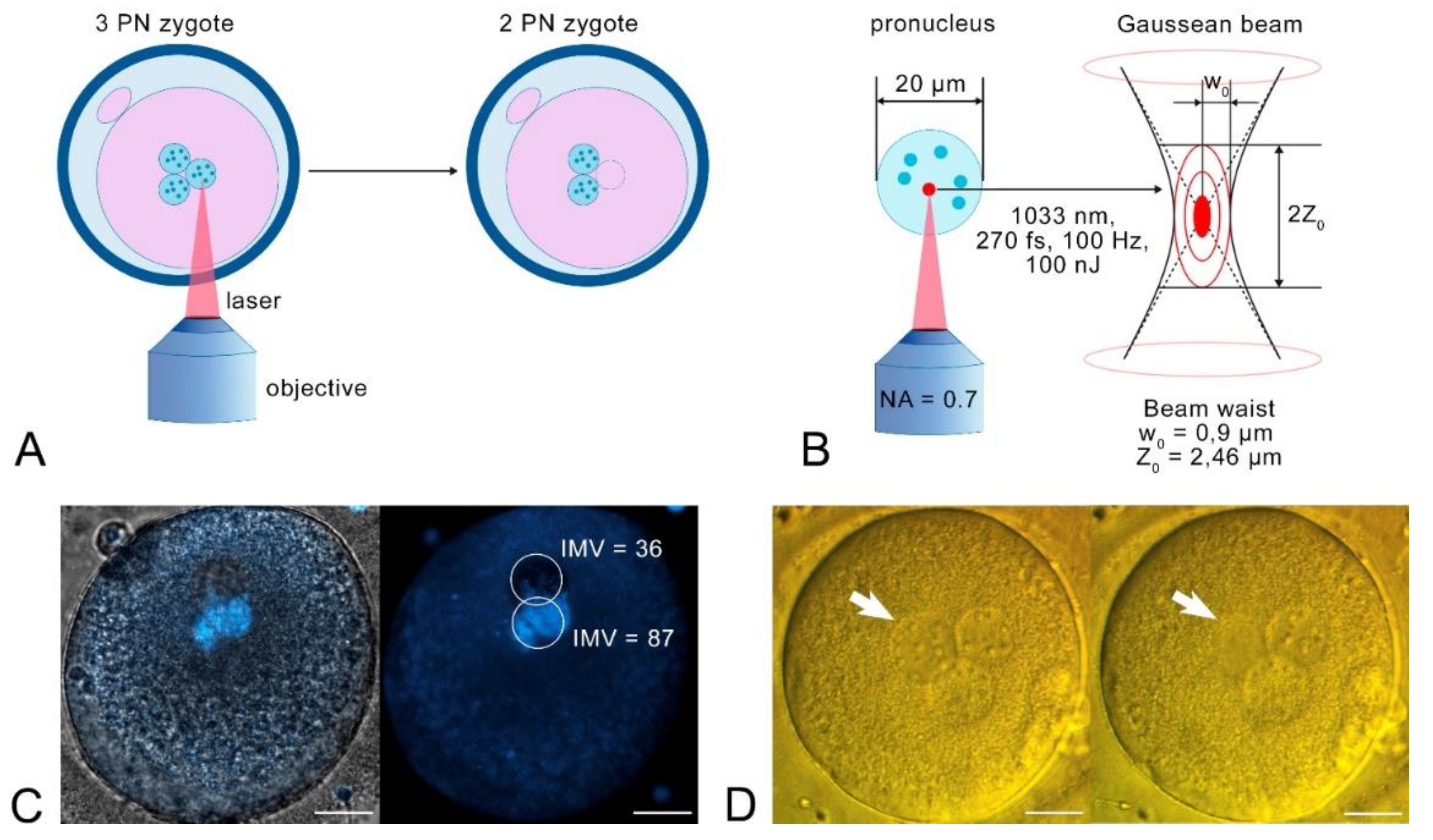

13]. Briefly, in these experiments we used a femtosecond laser TETA (Avesta Project). The following irradiation parameters were applied for pronuclear destruction: λ = 1033 nm, υ = 100 Hz, pulse duration 270 fs, pulse energy 100 nJ measured in the sample plane after the objective lens (60х, NA = 0.7). For experiments, zygotes were placed on a 0.17 mm coverglass (Heinz Herenz) in 50 µl of G-MOPS (10130, Vitrolife). The pronucleus was then exposed to laser radiation, as it shown at

Figure 1, a and b. Exposure of the entire PN was achieved by moving the microscope slide using an integrated external hand controller. The procedure was repeated in three different Z planes (observation plane and ± 5 µm from the observation plane) for a complete exposure of the pronucleus.

2.3. Hoechst Staining and Visualization

The oocytes were stained for DNA in a 50 µl M2 drop supplemented with 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (B2261, Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes. The oocytes were then placed in a clear medium and imaged on a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany), 20x Plan-Apochromat objective (NA = 0.8). Single-photon excitation of Hoechst was performed using a wavelength of 405 nm laser.

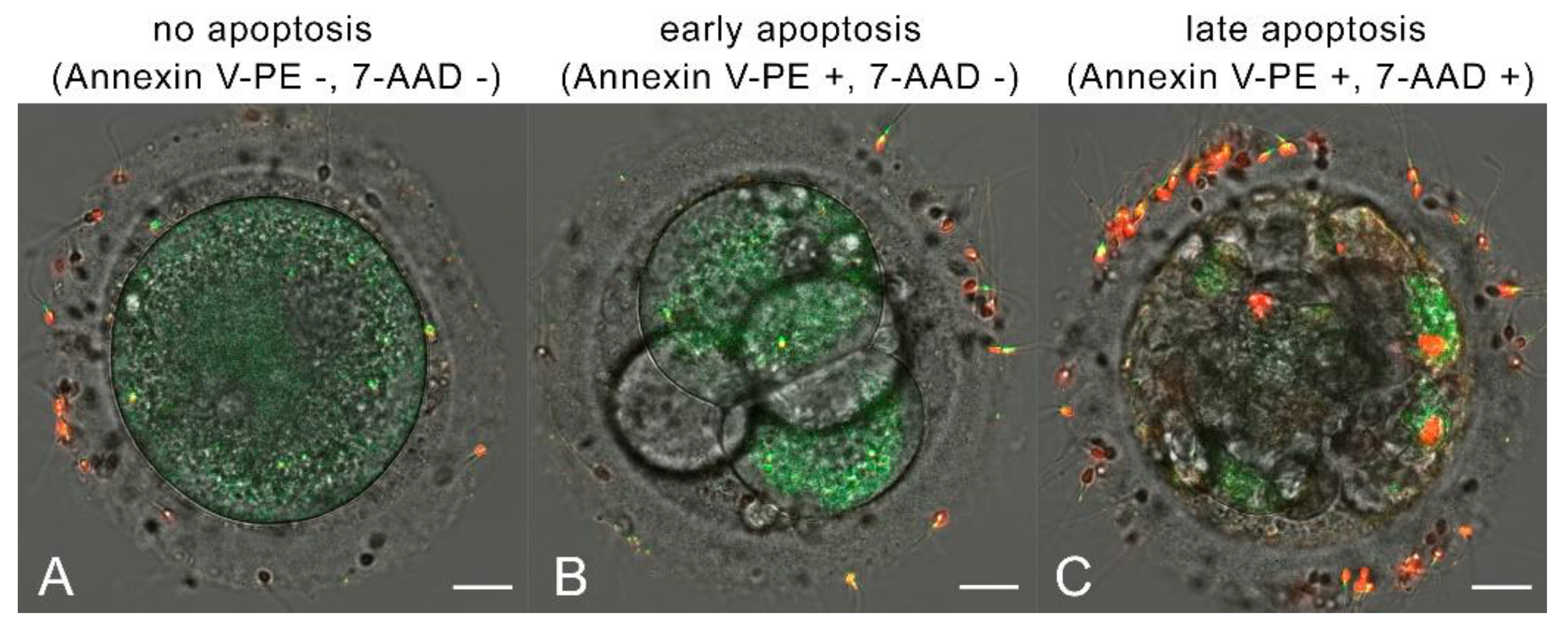

2.4. Apoptosis Staining, Classification and Imaging

The embryos were stained for early and late apoptosis on day 5 of development using the Annexin V-PE/7-AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit (A213, Vazyme). The embryos were incubated in a 30 µl drop of a binding buffer supplemented with 2 µl Annexin V-PE and 2 µl 7-AAD and covered with liquid paraffin (10100060A, Origio) for 10 minutes. This apoptosis detection kit allowed us to determine early apoptosis using Annexin V labeled with phycoerythrin (PE), which binds to phosphatidylserine (PS). Late apoptosis (or necrosis) was detected using 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD), a nucleic acid dye which cannot penetrate an intact cell membrane. Depending on the appearance of the fluorescent signal, this staining kit allowed us to divide the samples into three groups: no apoptosis (Annexin V-PE -, 7-AAD -); early apoptosis (Annexin V-PE +, 7-AAD -) and late apoptosis/necrosis (Annexin V-PE +, 7-AAD +). Imaging was performed with a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany), 20x Plan-Apochromat objective (NA = 0.8). Single-photon excitation of Annexin V-PE was performed with a 488 nm laser wavelength, and 7-AAD – with a 561 nm laser. Annexin V-PE luminescence was detected in the range of 495-602 nm, and 7-AAD was detected in the range of 566-728 nm. Due to the high sensitivity of the detectors, the autoluminiscence signal was also detected in 495-602 nm range, overlapping the Annexin V-PE signal. In healthy and unstained samples, the autoluminiscence signal (mean intensity over the sample) can be measured up to 10 arbitrary units (a.u.). Thus, to distinguish autoluminiscence from Annexin V-PE signal, we assumed the signal below 10 a.u. as «no apoptosis» (Annexin V-PE -), and the signal above 10 a.u. as «early apoptosis» (Annexin V-PE +).

3. Results

First, we investigated the effect of the laser on the pronucleus. In this preliminary experiment, we chose the optimal parameters for PN irradiation, and set the pulse energy to a value of 100 nJ. After pronucleus irradiation, the oocyte was stained with Hoechst 33342 to examine the presence of DNA (Fig. 1, c). Confocal imaging revealed weak DNA luminescence in the irradiated PN (it was two times lower than DNA luminescence in the intact pronucleus).

In the main series of experiments, one randomly selected pronucleus was irradiated. The pronucleus lost its borders and its nuclei disappeared during irradiation (Fig. 1, d). The experimental group contained 4 oocytes, while the control group also contained 4 oocytes which were not exposed to the laser.

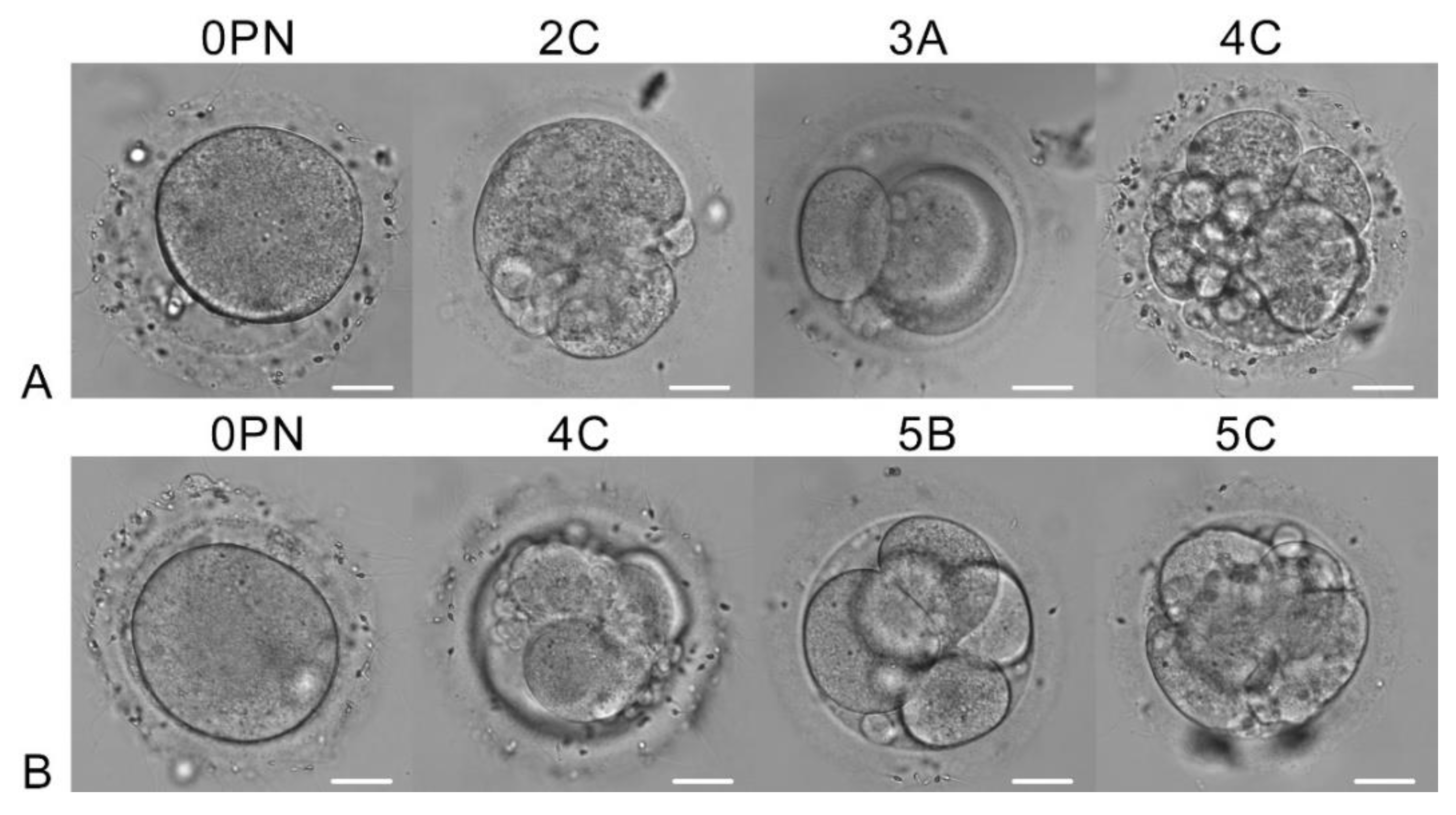

After overnight culturing, we assessed the development of zygotes (day 2 of development). One oocyte in the experimental group blocked its development, and the other three cleaved (

Figure 2, a). The same situation was observed in the control group (

Figure 2, b). The developing embryos had 2-5 cells, however, their quality by ASEBIR criteria was not very high: 0PN, 2C, 3A and 4C in the experimental group, and 0PN, 4C, 5B and 5C in the control group. On day 5, all embryos stopped their development or became atretic.

We examined the embryos for early and late apoptosis on day 5 of development. Among the irradiated oocytes, one showed no signs of apoptosis, two were in early apoptosis, and one was in late apoptosis. In the control group, one sample showed no signs of apoptosis, and three were in late apoptosis. A typical appearance of early and late apoptosis is shown in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated the principal possibility of zygote ploidy normalization using a 1033 nm femtosecond laser. After laser exposure, the irradiated pronucleus completely disappeared and lost the ability to stain DNA fluorescently. This indicates that the DNA in the irradiated pronucleus was destroyed or at least lost its double helix structure. The sample is not sufficient to make a convincing conclusion about viability, but irradiation of the pronucleus did not reveal oocyte destruction. The ability of irradiated zygotes to cleave was comparable to that of the oocytes in the control group (three of four zygotes (75%) cleaved in each group). In comparison, in microsurgical PN removal, the ability of zygotes with normalized ploidy to cleave was estimated at 77% (57 of 74 zygotes cleaved), and 6.8% of zygotes formed a blastocyst (5 of 74) [

7].

Exposure on living cells to femtosecond lasers is often accompanied by vapor-gas or cavitation bubbles which can damage the cell integrity [

19]. We determined laser parameters that allow for efficient pronucleus destruction without boiling and cavitation. Thus, we suggest that this approach can be useful for assisted reproductive technologies.

Funding

This work is supported by the Russian Science Foundation under grant № 25-75-20020.

Data Availability Statement

No data were generated or analyzed in the presented research.

Acknowledgments

The work was performed on the facilities of ACBS Center of the Collective Equipment (№ 506694, FRCCP RAS) and large-scale research facilities № 1440743.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- J. Zhang, H.L., S. Luo, Z. Lu, et al., “Live birth derived from oocyte spindle transfer to prevent mitochondrial disease,” Reprod Biomed Online, 34(4), 361-368 (2017). [CrossRef]

- E. Kang, J. Wu, N.M. Gutierrez, et al., “Mitochondrial replacement in human oocytes carrying pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations,” Nature, 540(7632), 270-275 (2016). [CrossRef]

- S. Kattera and C. Chen, “Microsurgical enucleation of tripronuclear human zygotes,” Fertil Steril, 50(2), 266-272 (1988). [CrossRef]

- H.E. Malter and J. Cohen, “Embryonic development after microsurgical repair of polyspermic human zygotes,” Fertil Steril, 52(3), 373-380 (1989). [CrossRef]

- S. Kattera and C. Chen, “Normal birth after microsurgical enucleation of tripronuclear human zygotes: case report,” Hum Reprod, 18(6), 1319-1322 (2003). [CrossRef]

- M.-J. Escribá, J. Martín, C. Rubio, et al., “Heteroparental blastocyst production from microsurgically corrected tripronucleated human embryos,” Fertility and Sterility, 86(6), 1601-1607 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Y. Fan, R. Li, J. Huang, et al., “Diploid, but not haploid, human embryonic stem cells can be derived from microsurgically repaired tripronuclear human zygotes,” Cell Cycle, 12(2), 302–311 (2013). [CrossRef]

- C. Jiang, L. Cai, B. Huang, et al., “Normal human embryonic stem cell lines were derived from microsurgical enucleated tripronuclear zygotes,” Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 114(9), 2016–2023 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Hyslop L. “Pronuclear transfer in human oocytes,” Methods Mol Biol, 1818, 31-36 (2018).

- B.E Rosenbusch, “Selective microsurgical removal of a pronucleus from tripronuclear human oocytes to restore diploidy: disregarded but valuable?” Fertility and Sterility, 92(3), 897-903 (2009). [CrossRef]

- A.M. Shakhov, A.A. Astafiev, A.A. Osychenko, et al., “Effect of femtosecond laser radiation on mammalian oocytes,” Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 10(5), 816-819 (2016). [CrossRef]

- I. Ilina and D. Sitnikov, “From zygote to blastocyst: application of ultrashort lasers in the field of assisted reproduction and developmental biology,” Diagnostics (Basel), 11(10), 1897 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L.M. Davidson, Y. Liu, T. Griffiths, et al., “Laser technology in the ART laboratory: a narrative review,” Reprod Biomed Online, 38(5), 725-739 (2019). [CrossRef]

- A.A. Osychenko, A.D. Zalessky, A.V Bachurin, et al., “Stain-free enucleation of mouse and human oocytes with a 1033 nm femtosecond laser,” Journal of Biomedical Optics, 29(6), 065002 (2024). [CrossRef]

- U.A. Tochilo, A.A. Osychenko, A.D. Zalessky, et al., “Femtosecond laser is an effective instrument to remove DNA in pronuclei of mouse zygotes,” St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University Journal. Physics and Mathematics, 15(3.2), 302-305 (2022).

- A.A. Osychenko, A.D. Zalessky, U.A. Tochilo, et al., “Femtosecond laser oocyte enucleation as a low-invasive and effective method of recipient cytoplast preparation,” Biomedical Optics Express, 13(3),1447-1456 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Vogel, J. Noack, G. Hüttman, et al., “Mechanisms of femtosecond laser nanosurgery of cells and tissues,” Applied Physics B, 81(8), 1015–1047 (2005). [CrossRef]

- A. Zalessky, Y. Fedotov, E. Yashkina, et al., “Immunocytochemical localization of XRCC1 and γH2AX foci induced by tightly focused femtosecond laser radiation in cultured human cells,” Molecules, 26(13), 4027 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A.A. Osychenko, U.A. Tochilo, A.A. Astafiev et al., “Determining the range of noninvasive near-infrared femtosecond laser pulses for mammalian oocyte nanosurgery,” Sovremennye Tehnologii v Medicine, 9(1), 21-26 (2017). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).