1. Introduction

A shallow seasonal snowpack covers approximately 50% of the Northern Hemisphere, making the snowpack surface the primary land-atmosphere interface during the winter season [

1,

2]. Across Colorado United States (U.S.), an important headwater state in the western United States, 60% of annual precipitation falls as snow [

3,

4]. Accurate observations and modeling of snow water resources in the western United States is essential for water budgeting, recreation, wildfire management, and ecological resources [

5].

The snowpack varies spatially and temporally [

6], and is controlled by local, regional, and global weather and climate [

7]. Consequently, snowpack conditions will vary between maritime and continental climates [

8]. Due to the variability of the snowpack across these various regimes, a standard metric to quantify the snowpack is difficult to acquire. The aerodynamic roughness length,

, can be used as a measure of the snowpack surface [

9,

10]. The

captures the variability that is produced by land cover characteristics as well as the underlying topography [

2,

6,

11]. The variability is further enhanced by meteorological conditions [

6], non-uniform distribution of snow cover during accumulation and ablation [

6,

9], snow-canopy interactions [

12], and wind redistribution of snow [

13]. Small scale (<1 meter) and large scale (>1 meter) variations within the snowpack can alter the overall

value [

10,

14,

15]. The effect of a single roughness feature coupled with non-uniform spatial arrangement among other elements affects all aspects of the snowpack surface [

9,

10]. A dynamic

characterizes heterogeneity in snow-water equivalent, melt rates [

9], redistribution, snow deposition [

6], and surface energy fluxes [

16].

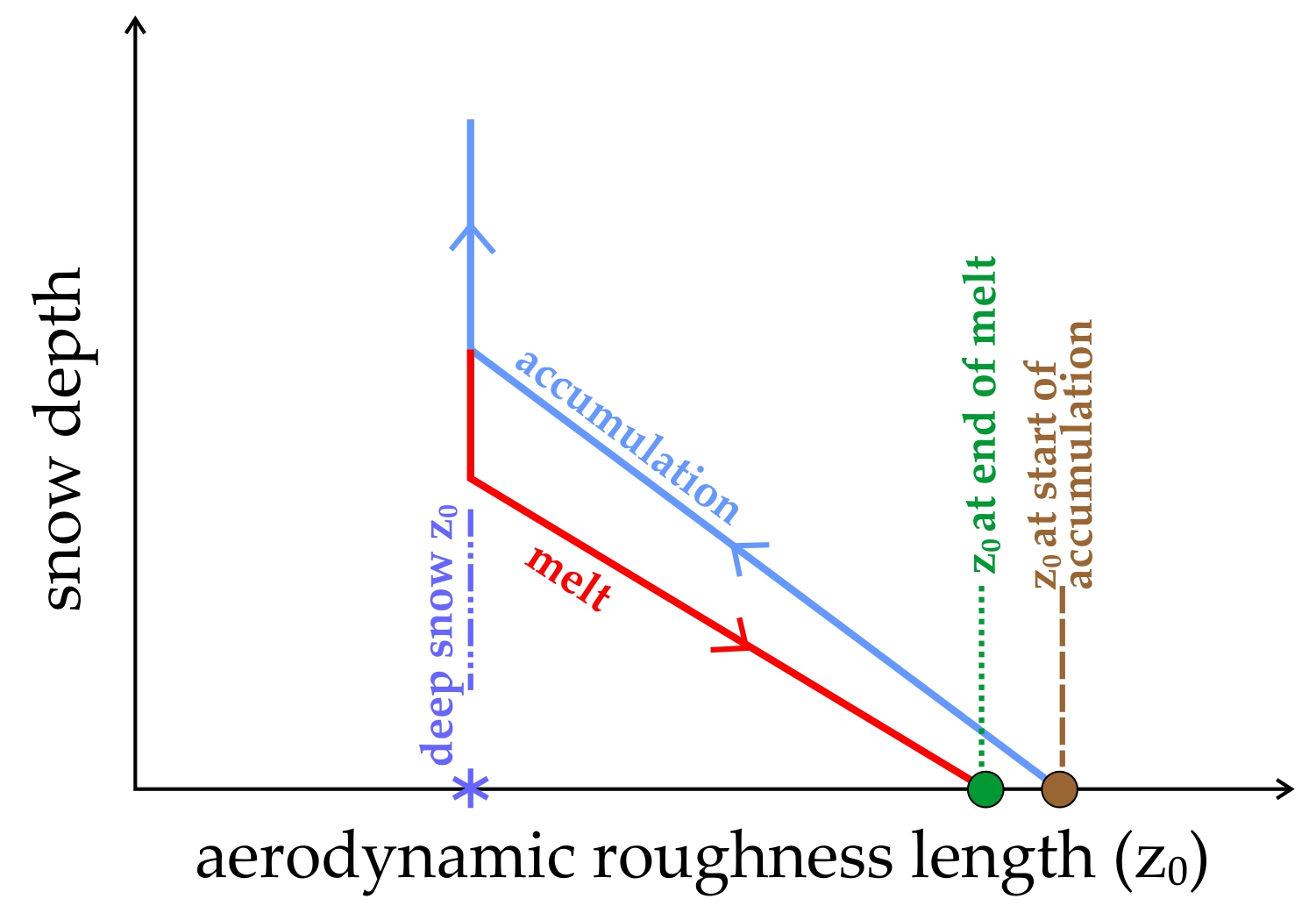

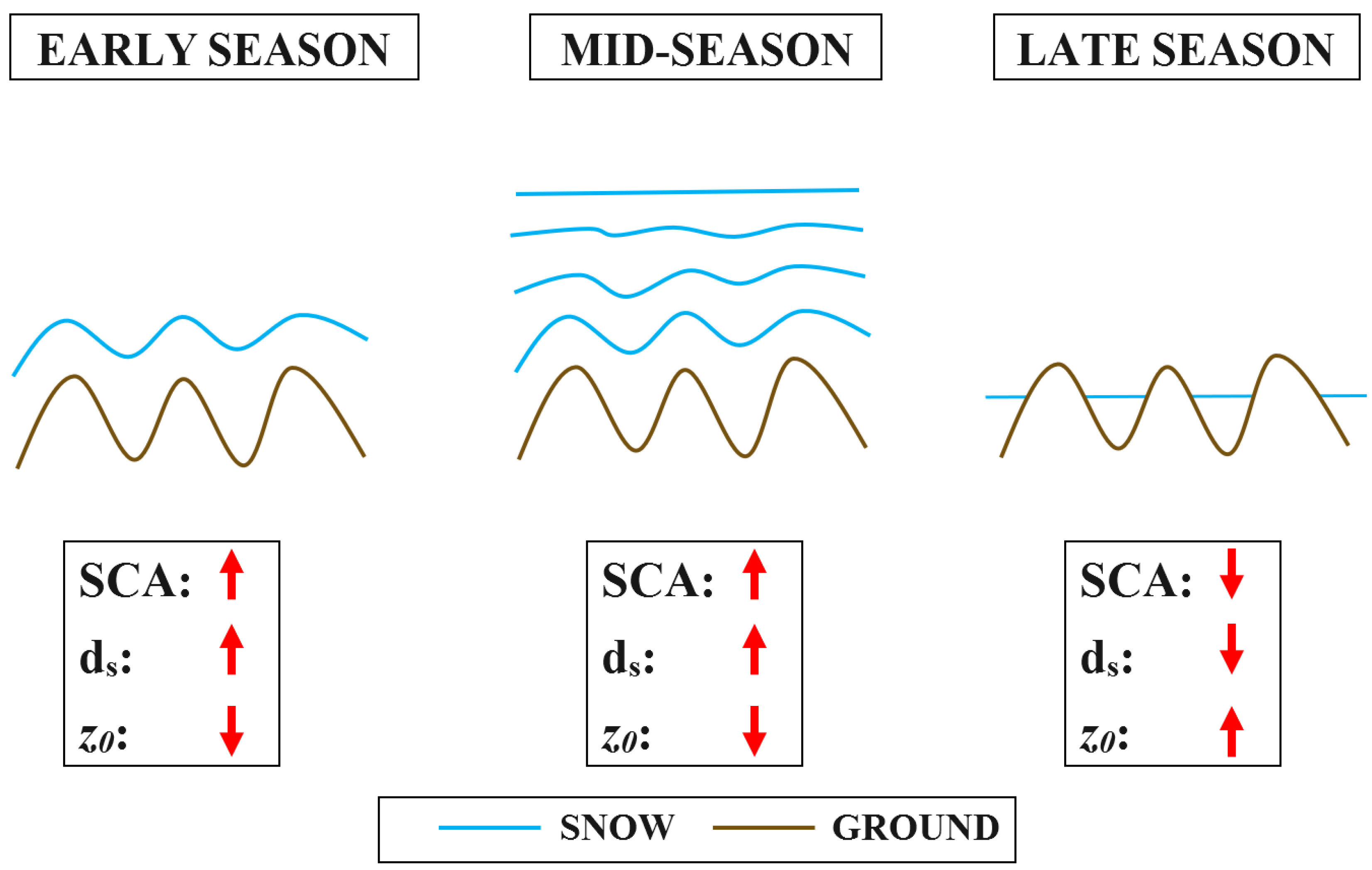

The

will decrease during accumulation as the snow initially conforms to the underlying terrain (

Figure 1) [

16]. Once a threshold snow depth,

, is reached, the snow surface has decoupled from the topography and becomes smoother, resulting in a smaller

[

9,

16,

17]. Quincey et al. [

18] found that one new snowfall decreased

by 75% since it covered small scale feature variability and only large features were left to increase the roughness. As

decreases due to compaction, metamorphism and/or ablation, ground-based surface features and underlying topographical features are re-coupled with

, increasing its variability [

16,

19].

This relation of increasing

and decreasing

in some form has been observed previously [

2,

9,

20]. This correlation of

and

is not considered within hydrologic, snowpack, or land surface models. The relation of these two factors is also expected to differ between periods of melt and accumulation as periods of melt are typically less uniform [

16]. Swenson and Lawrence [

21] found that topography and land cover features have the most influence on the hysteresis. Once the snow cover has reached full coverage over these features, the snowpack will accumulate homogeneously [

16]. These early, mid, and late-season snowpack surface changes have important impacts (

Figure 1) on estimating an accurate

value within hydrologic models [

19].

To accurately understand and model the snowpack, variability needs to be considered at the local level. Otherwise, hydrologic models will either over or underestimate melt water availability and melt rates [

19,

22,

23]. Currently, the same

is used for an entire watershed, based on the assumption of 100% snow covered area, undeviating melt throughout an area, despite the topographic or vegetation influences [

6,

23]. No other spatial or temporal variation in

are represented [

24]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the incorporation of

as a dynamic variable, rather than a static parameter, will improve meteorologic, snowpack and hydrologic models [

2,

19,

20,

23,

25]. To understand and observe the relation between

and

, the following questions are asked: 1) Does the snow surface roughness, defined here as

, change as a function of

? 2) Does the correlation between

and

vary over space? 3) Is the decrease in

as

increases consistent regardless of the initial ground roughness? 4) Is the correlation between increasing

and decreasing snow surface

a function of the initial roughness feature, such as dominate vegetation and topographic features? and, 5) Is there a difference between the

-

correlation during periods of accumulation and melt, i.e., is it a hysteretic?

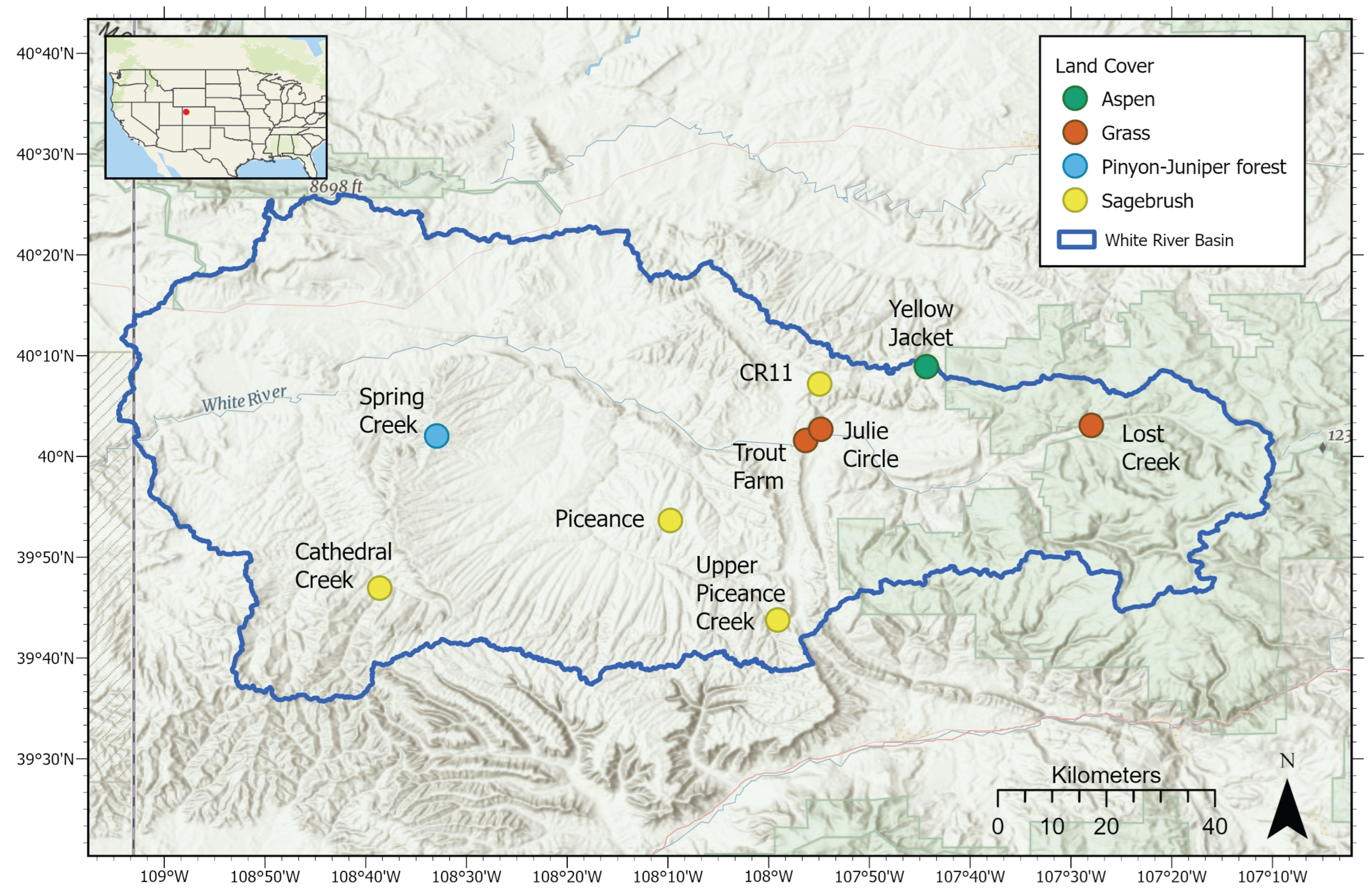

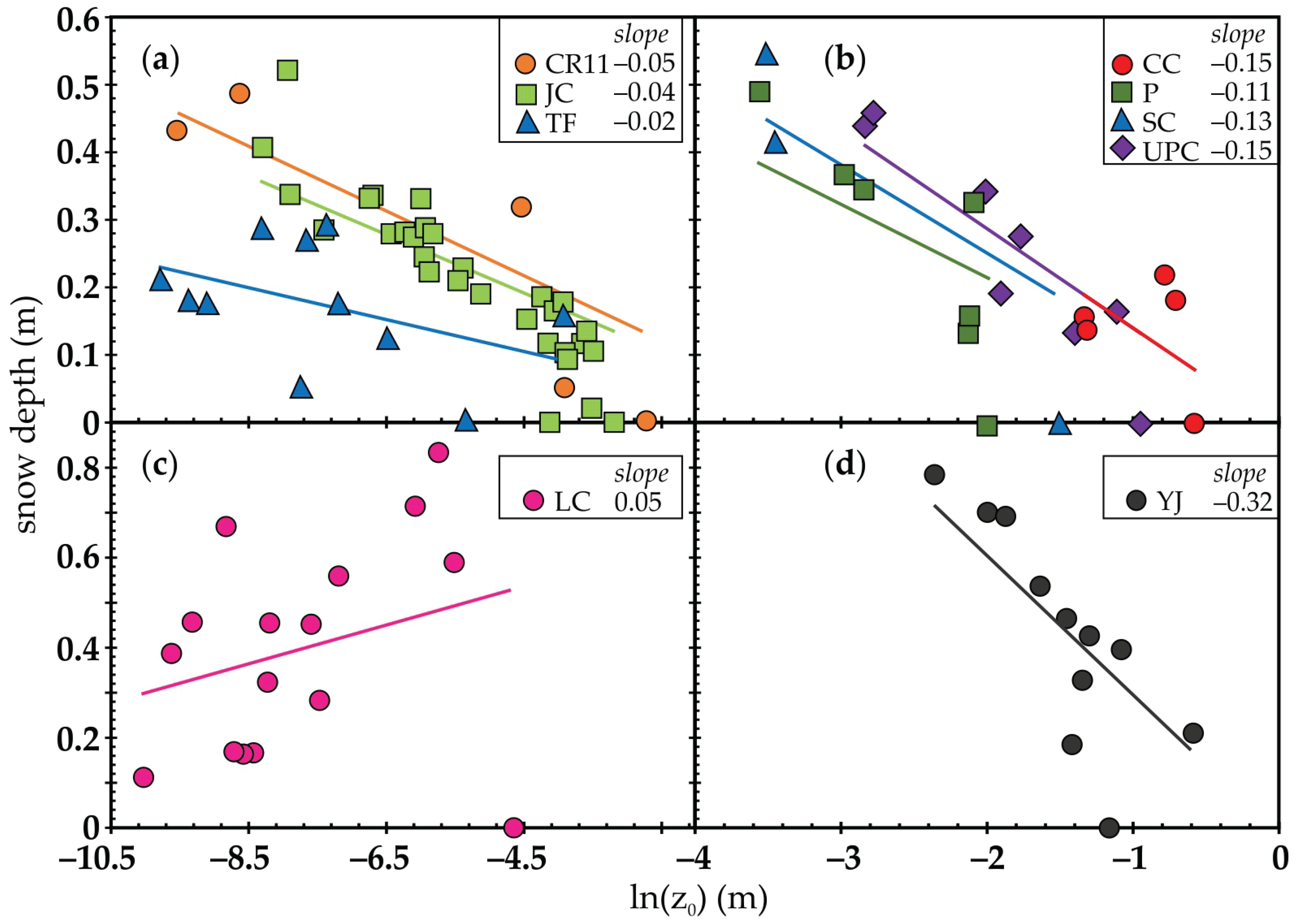

3. Results

Over the 2019-2020 winter season, 112 total site visits were conducted between October and April. All sites, except Lost Creek (

Figure 4c), showed that as

increased and enveloped roughness features, the corresponding

decreased (

Figure 4). For example, the Piceance site (P in

Figure 4b) shows

increasing and the corresponding decreasing in

until 3 March 2020, when melt began. Furthermore, as

starts decreasing, the

values begin to increase. This relation developed quickly, and roughness feature size had an impact on the trend line slope. Lost Creek was disturbed during the spring and therefore did not follow this same temporal pattern (

Figure 4c and

Figure 5a,b).

To identify spatial and temporal patterns, the sites were grouped using the resulting slopes from the least square regression fit: CR11, Julie Circle, and Trout Farm (

Figure 4a); Cathedral Creek, Piceance, Spring Creek, and Upper Piceance Creek (

Figure 4b); Lost Creek (

Figure 4c); and Yellow Jacket (

Figure 4d). CR11 and Julie Circle have similar

values (0.73 and 0.68, respectively), slope, roughness feature height, and initial

values (

Figure 4a). This result was seen despite the difference in data quantity between the two sites, i.e., five measurements (CR11) versus 31 measurements (JC). The primary roughness feature height (height of the tallest feature found within the AOI

Table 1) at CR11 and Julie Circle are 0.46 m and 0.35 m; the slope is -0.048 and -0.043, respectively. Julie Circle had one notable outlier on 6 February 2020, with a

of 0.52 m and a

value of 3.5 x

m (

Figure 6). This occurred after an overnight storm deposited 0.18 m of new snow. Conversely, the lowest

at the site occurred on 10 February 2020 with a

of 0.41 m and a

of 0.25 x

m. Similar to Julie Circle, the deepest

at CR11 of 0.49 m on 10 February 2020 had a

of 0.18 x

m, yet the lowest

(

of 0.07 x

) at the site occurred during the second deepest

of 0.43 m on 29 January 2020. Trout Farm had a similar slope to this pair (

Figure 4a). Yet, compared to CR11 and Julie Circle with initial

values of 66 x

m and 40 x

m, Trout Farm had the lowest roughness feature height (0.01 m for a grassy lawn) and initial

of 4.8 x

m (

Figure 5c,d. These initial

values are an order of magnitude different between CR11 and Julie Circle. However, the slope of -0.02 at Trout Farm was not substantially different from Julie Circle.

The second grouping of sites includes Cathedral Creek, Piceance, Spring Creek, and Upper Piceance Creek (

Figure 4b). These sites had the lowest number of site visits (three to eight) due to distance and difficult winter access. The slopes of all four sites were alike, Cathedral Creek -0.15, Piceance -0.11, Spring Creek -0.13, and Upper Piceance Creek -0.14. The main variation among these sites is the

, primary roughness feature height, and initial

values. Spring Creek and Upper Piceance Creek have the highest

of 0.71 and 0.79, respectively. Though, Spring Creek had the least amount of site visits and corresponding data. Upper Piceance has the highest amount of site visits in this grouping. Outliers from Cathedral Creek are from the two highest

of 0.19 m and 0.23 m, and

values 4.9 x

m and 4.4 x

m, respectively. Furthermore, the second group had the largest variation of roughness feature sizes ranging between 0.68 m at Piceance and 1.65 m at Upper Piceance Creek. It was initially thought that Piceance would correlate with group a (

Figure 4a) due to the size of the primary roughness feature height. Yet, the initial

was 1.1 x

m, which is much larger than the others within group a.

Spring Creek had a roughness feature height of 1.1 m and initial

of 2.2 x

m which represents an average throughout the sites. The all-site average slope, roughness feature size, and initial

was -0.10, 0.84 m, and 1.9 x

m, respectively. Cathedral Creek had the highest initial

value of 5.6 x

m, but it had only the third largest roughness feature (1.3 m), indicating the site had the highest quantity of roughness features. Upper Piceance Creek had the second-largest initial

value and roughness feature height at 3.9 x

m and 1.65 m, respectively. However, both sites fell below Yellow Jacket, which was placed singularly into

Figure 4d. Yellow Jacket had the largest roughness feature of 1.85 meters (Aspen, large sage, and shrubbery). Though, it produced the third largest initial

value of 3.3 x

m. Additionally, it had the steepest slope of any of the sites at -0.32. Yellow Jacket had two outliers that resulted in a higher

value than the initial

value. These instances occurred on 16 March 2020 and 7 April 2020, late in the season after peak

had occurred (

Figure 5e,f).

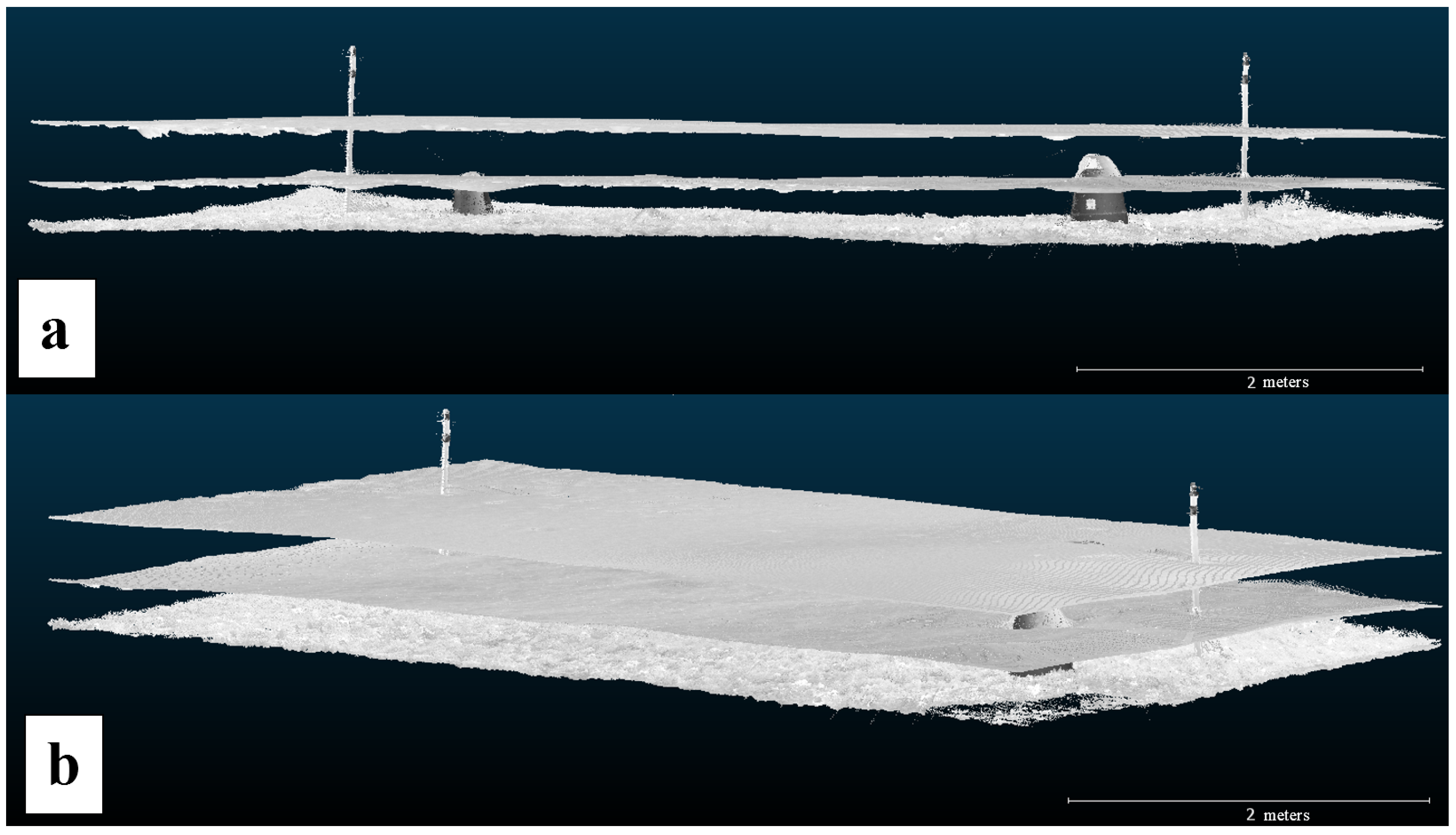

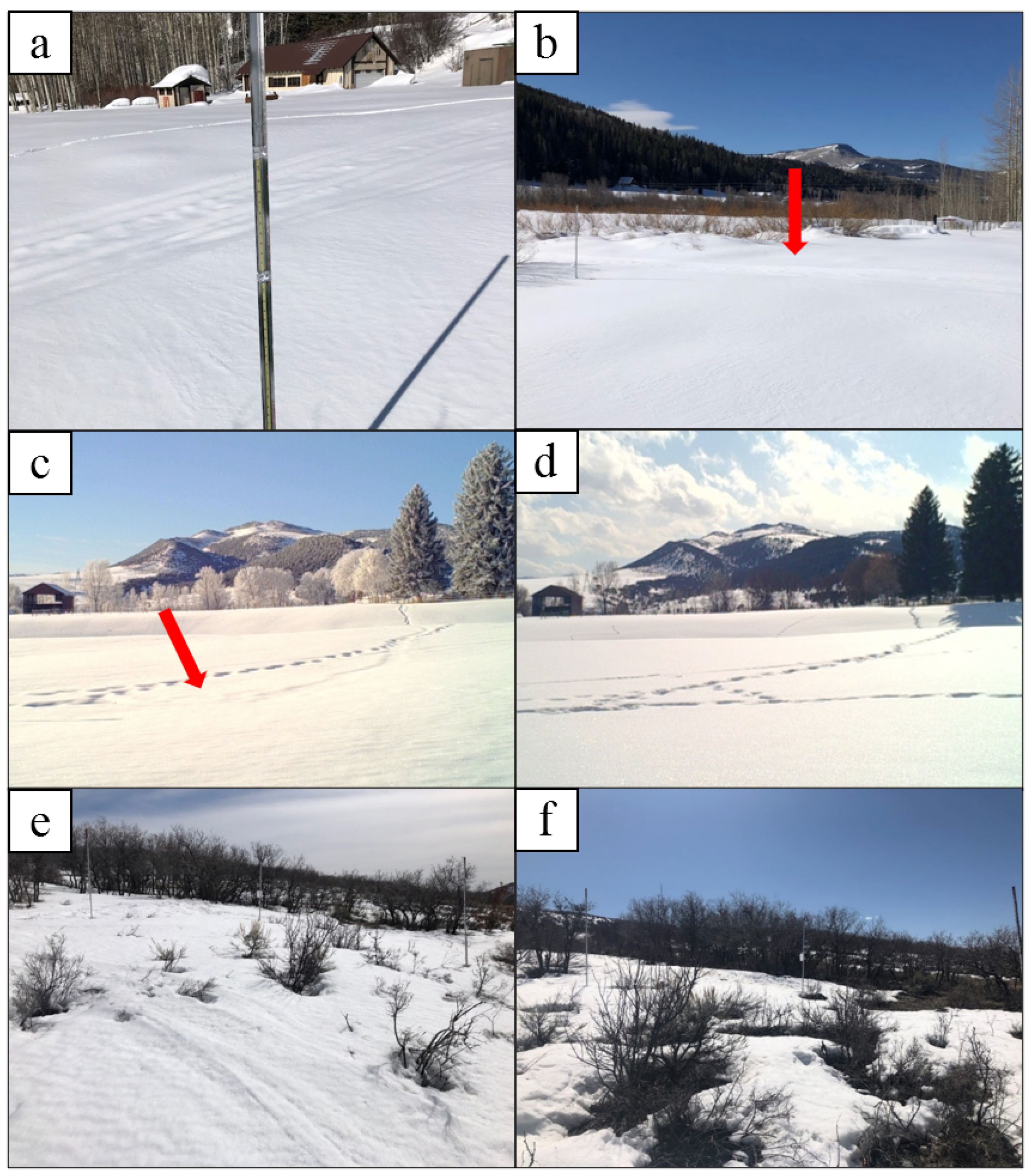

Lost Creek experienced heavy anthropogenic influence as shown in

Figure 4c. Between 28 January and 26 February 2020 a snowmobile drove through the site which altered the natural progression of the snow (

Figure 5a,b). Still, Lost Creek results show some similarities to the other sites. Prior to the snowmobile, Lost Creek was following the same hysteresis relation as the other sites. Lost Creek had the lowest

, -0.28, attributed to the data being forced through the origin on the plot. When the data is not forced, the

becomes 0.08, which is still a very low correlation likely due to the snowmobile tracks.

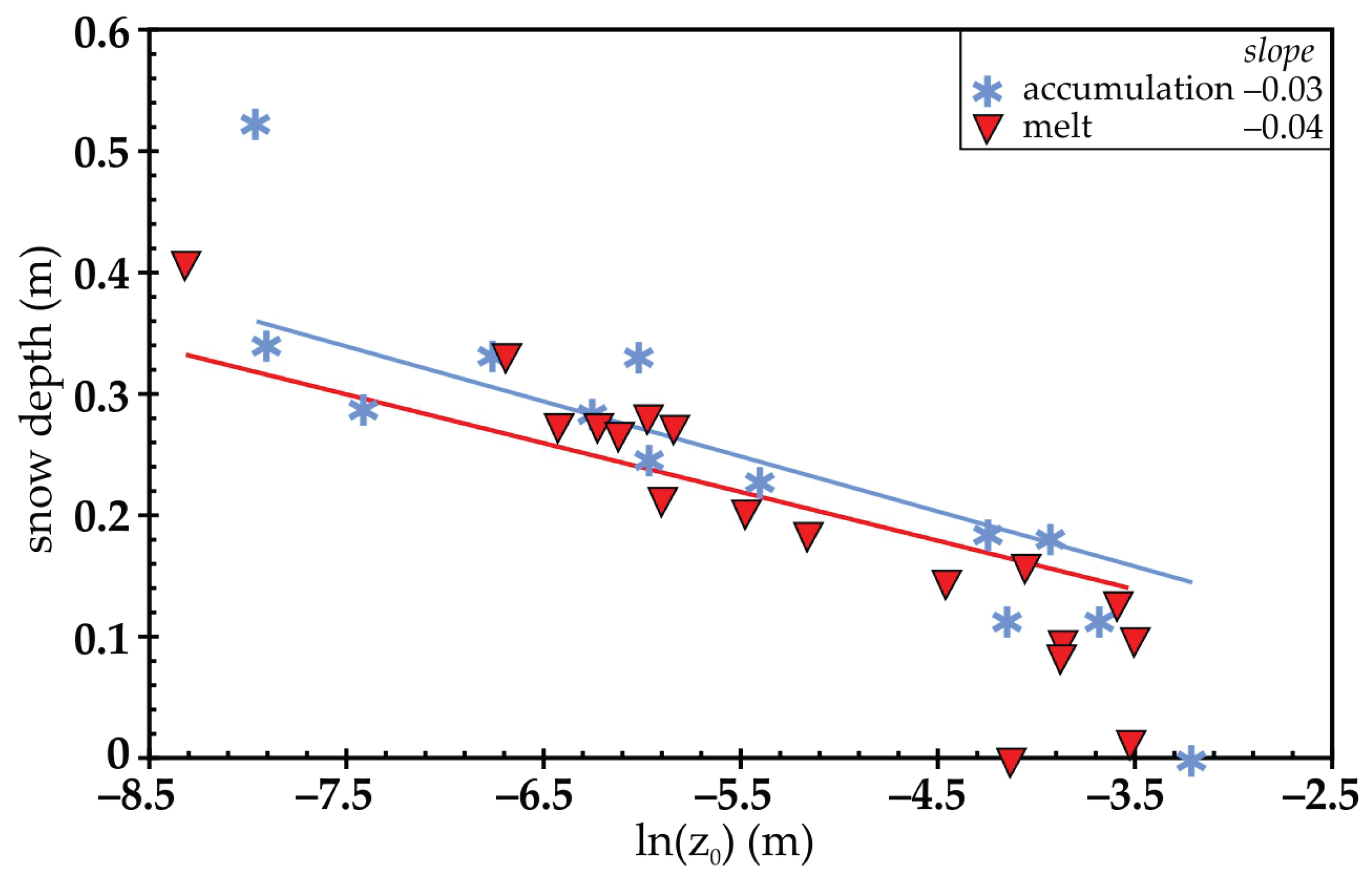

Since Julie Circle had the most data points of any site, it was used to analyze melt and accumulation values (

Figure 6). There are 12 accumulation points, 17 melt points, and two points with

of 0 m, taken as the initial surface roughness scan (fall) and the final surface roughness scan (spring). The results had a varying slope of -0.03 for melt, and -0.04 for accumulation. Melt resulted in an

of 0.36, and accumulation resulted in an

of 0.66.

4. Discussion

The calculated

changed as a function of observed

, although outliers of the relation existed. The first outlier was at the Julie Circle location (

Figure 4a). The initial point on the x-axis indicates the highest

value (40 x

m) due to the lack of snow, i.e.,

= 0 and this occurred prior to accumulation. The other point with a

of 0 was at the end of the season after all the snow melted produced less than half the

(16 x

m)of the initial

. This is likely attributed to the vegetation type, which is a regular lawn grass that was pushed down by the weight of the snow throughout the year. This scenario could happen to any type of thin, flexible vegetation, fluctuating

values depending on time of year [

10,

18].

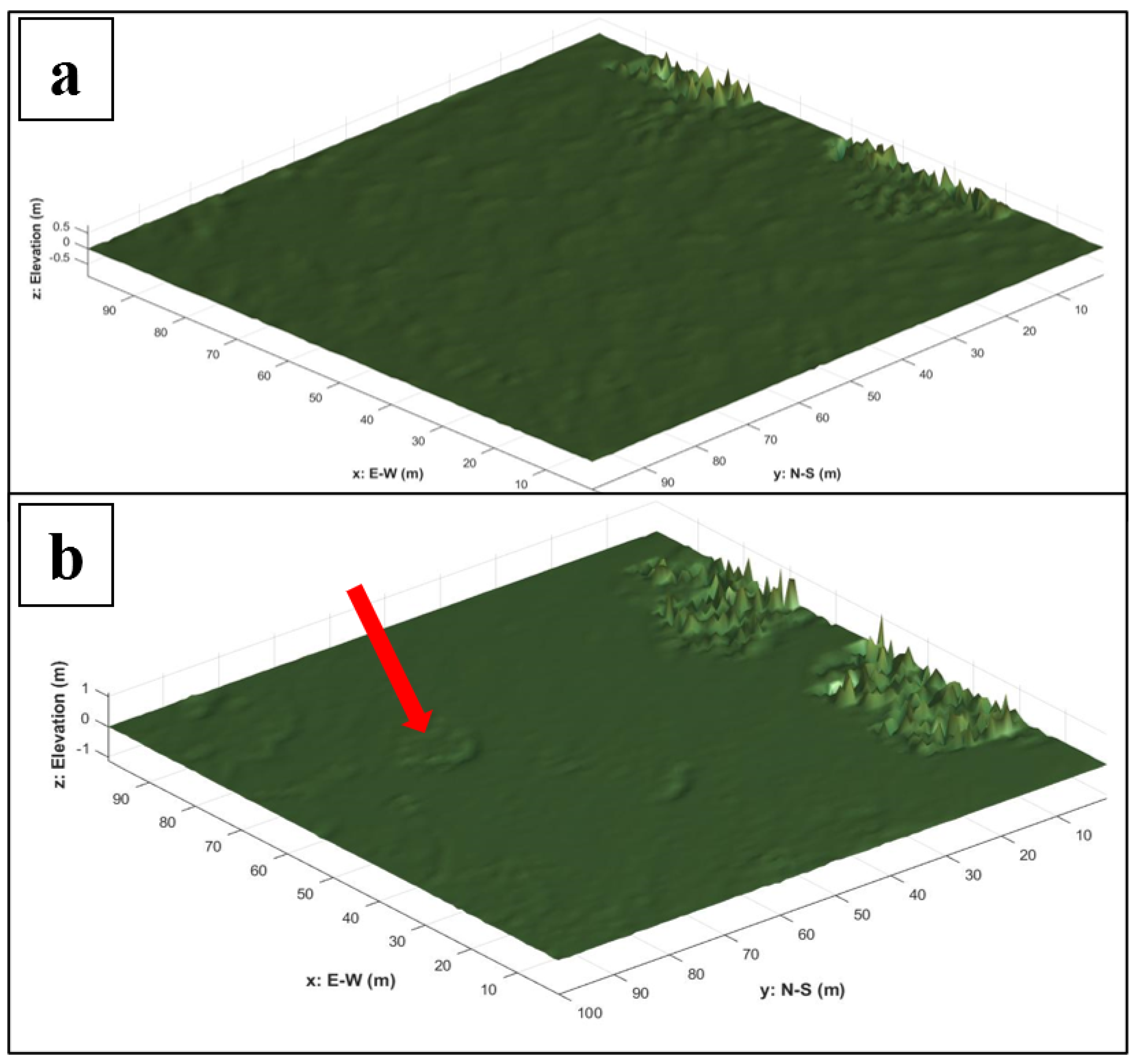

Another discrepancy at the Julie Circle site is the lack of correlation between the highest

and lowest

value. A likely explanation for this observation is the large Cottonwood tree that overhangs the Julie Circle site. For example, within the point clouds the pock-marks in the snowpack surface (

Figure 3b) where accumulated canopy snow fell from the limbs and altered the roughness. No other sites in this study had canopy cover like Julie Circle. Although, most sites did have shrubbery present [

32], so even small-scale canopy interception and deposition was possible [

18]. Canopy interception and redeposition is a potential issue when correlating between

and

. Therefore, to assume a uniform or linearly metamorphosing or melting snowpack could lead to errors [

9,

10,

33].

This lack of correlation is also noted at CR11 and Trout Farm. Similar to Julie Circle, the highest

value did not correspond with the lowest

value at CR11. This can be attributed to a recent snowfall event of about 10 cm that had fallen the day before the 29 January 2020 scan. On 10 February 2020 there was less fresh snow (approximately 5 cm) and conditions were sunny and warm. These differences in the snowpack were recorded in site notes and photos from the visits. Likewise, Trout Farm also experienced the same contradiction, the highest

value had a

greater than double the lowest calculated

. This indicates that these small variations of the snowpack surface is key to addressing

beyond simply considering the snow depth. Accounting for small surface variations is especially important on flat sites where initial

may be surpassed by the development of surface features such as sun cups, sastrugi, surficial features, wildlife, and anthropogenic modifications [

4,

18,

33,

34].

Cathedral Creek (

Figure 4b), followed the

and

relation until the 10 and 24 February 2020 scans. Between the scan dates of 16 January and 10 February 2020 temperatures were often warmer than , with a maximum temperature of 19°C. The interpolated surfaces of 16 January 2020 (lowest

) and 24 February 2020 (highest

) are shown in

Figure 7, highlighting pock-marks and uneven melting. These elevated temperatures resulted in an increased, non-uniform melt [

9]. So, even though additional snow fell between the scans, it did not completely cover the snow surface characteristics [

9,

16,

17].

Yellow Jacket had the highest initial

of any of the sites (

Figure 4c). Photos from the field visits late in the season show a lot of recent melt, which revealed larger shrubs as well as the development of sun cups within the AOI (

Figure 4e,f). The late season increase in roughness likely produced two irregular points with a higher

than the initial after peak

had occurred [

2]. Another influence on the site was the anthropogenic modifications of snowmobile tracks. Combining these two factors led the roughness variations to be larger than the initial grassy, shrub-filled plot. This same anthropogenic disruption occurred at the Lost Creek site (

Figure 4c and

Figure 5a-d). This led to an extreme increase in

after the disturbance, even with the deep snowpack 0.85 m (

Figure 4d). The large increase in

at the site was exacerbated by the very flat topography that contained one small, controlled roughness feature (railroad tie) in the middle.

We hypothesized that slopes would remain the same and the x-intercept would change. However, the initial ground roughness played a critical role in the slope of the data. The 0.13 meter railroad tie at the Lost Creek site is an example of a feature responsible for the initial site

value of 9.4 x

m. Without it, the

would have been lower as the site was an open, grassy field. Due to this controlled roughness feature, none of the snowmobile-caused

values were larger than the initial

. Lost Creek also had some of the highest

, which led to higher

values, especially coupled with snowmobile tracks. Snowmobiling and other recreational activities are common throughout public lands during the winter [

4]. Anthropogenic factors such as these are important to consider when evaluating a spatially and temporally dynamic

[

4]. Moreover, this could explain the discrepancies in sites like Yellow Jacket, also influenced by snowmobiles. Together, land cover type and function need to be considered when applying

[

4].

Figure 4b shows the grouping of Cathedral Creek, Piceance, Spring Creek, and Upper Piceance Creek. The slopes of all four sites were similar ranging from -0.11 to -0.15. The

values, roughness features (ranging between 0.68-1.65 meters), and initial

values (ranging from 1.1 to 5.7 x

m) varied among the sites. Based on the primary roughness feature heights, Piceance aligns with the CR11, Julie Circle, and Trout Farm group than the one in which it was placed. Upper Piceance was more similar in initial

and roughness feature size to Yellow Jacket, but their slopes have a difference of 0.17. However, as discussed, there were some values that skewed the slopes in these sites. Potential reasoning for this was noted at several sites, such as overall changes of the surface of the snowpack throughout the season due to wind redistribution [

35], surface energy fluxes [

9], formation of surface features [

2], and non-uniform melt and accumulation [

9]. These influences metamorphize the snowpack and are very difficult to quantify or predict. The development of surface features is one reason why the slopes of Trout Farm and Julie Circle have only a slight difference despite the initial

values being an order of magnitude different (4.8 x

and 40 x

m, respectively).

Julie Circle was used to compare melt and accumulation values (

Figure 6). The accumulation values had a stronger

value of 0.66, compared to that of the melt (

= 0.36), indicating accumulation was more uniform [

16] (

Figure 1). This was to be expected, since this relation was not observed to be linear in either case. The low correlation of the melt values can be attributed to several environmental processes, which is typically occurs within any snowpack. Potential melt factors are sensible and latent heat fluxes, dust deposition [

36], spatial and temporal distribution of incoming solar radiation [

37], wind redistribution [

33,

39], longwave radiation [

38], anthropogenic alterations [

4,

13], air temperature [

40], spatial heterogeneity of the snowpack [

23], and vegetation cover [

7]. Since melting occurred throughout the season, the environmental influences were also affecting accumulation rates, which supports the heterogeneity of the accumulation

values. Melt rates influence atmospheric and hydrologic processes [

13], and understanding the processes and rates that control melt water production is important for predicting the timing and magnitude of peak melt in a watershed [

22,

23,

41]. Initially, accumulation versus melt hysteresis aspect of the study was to be conducted at Lost Creek and Yellow Jacket, however, these sites were anthropogenically altered and were thus not used. It was hypothesized that the melt versus accumulation at Yellow Jacket would yield a higher difference between the accumulation slope and the melt slope due to the higher initial roughness and quantity of roughness features to enhance melt (

Figure 5e and f). Since Lost Creek was a flat, open site (

Figure 5a), it was hypothesized that the slopes would be similar to Julie Circle. The primary influence of melt at Julie Circle was the addition of ecological factors from the tree near the site, and the proximity to a residential house, potentially increasing the effects of longwave radiation induced melt. At Lost Creek, incoming solar radiation would dominate snowmelt. Therefore, slopes even more similar to each other were expected.

The method used to determine melt compared to accumulation values is also a source of potential error. Settling and metamorphism of the snowpack could have occurred resulting in snow depth decreases without any actual snowmelt taking place [

13,

16,

37]. Photos, atmospheric conditions, and visual assessments of the site were completed. For these shallow snowpacks where multiple melt cycles can occur, snow wetness sensors, soil moisture sensors, and other atmospheric/hydrologic monitoring equipment could aid in determining the exact periods of melt. In deeper snowpacks, that typically only have one melt period at the end of the winter, within snowpack temperature sensors could assist in determining when the snowpack becames isothermal and is being to melt.

4.1. Next Steps

This study consisted of 112 site visits, which produced a robust dataset for observing trends and correlations. While increased temporal scan frequency, preferably daily, would offer further insight into the snowpack surface evolution due to surface processes [

6,

7] and meteorological factors [

2,

40], the current dataset still captures the overall temporal changes. The scan areas represent a small portion of the White River watershed. Although this limits direct watershed-scale extrapolation, the findings highlight important local-scale processes and variability. Site-specific features, such as the cottonwood tree at Julie Circle which influenced surface conditions and canopy cover, reflect natural heterogeneity common in snow-covered landscapes [

16]. However, some consistency was observed between sites with similar terrain and land cover. For example, Upper Piceance Creek and Cathedral Creek, both are situated on old river terraces near cliffs, exhibited comparable initial roughness values (39 x

and 56 x

m) and similar feature heights (1.65 m and 1.3 m), producing nearly identical

versus

slopes (-0.15). This suggests that once a

versus

correlation is identified, it could be applied to other areas with similar characteristics.

Future studies could include larger plots within a smaller watershed that can be scanned with LiDAR for snow accumulation and melt more frequently [

16,

20]. Measuring and/or modeling meteorological data, such as (net) shortwave and longwave radiation, could provide more insight to determining melt periods and subsequent accumulation periods during mid and late season melt [

36,

37]. This could yield a change in one of

or

without a change in the other, i.e., hysteresis between blue and red lines in

Figure 6 [

42]. This study is a step toward understanding snowpack surface roughness dynamics and scaling roughness-based energy balance assessments, which will improve snowpack, hydrological and meteorological modeling [

2,

19,

20,

23].

Furthermore, future studies could explore errors of uncertainty within the

calculations. The current code [

15] calculates

based on the local maxima and minima within the scan area. This method is acceptable when roughness elements are homogenously spaced and sized, however, that is not always the case in nature. The code could be reformed to calculate

on a certain sized area (every 0.012 meter, or 0.12 meter, etc. depending on the size of the scan). This would give a distribution of

values that would encompass the variations in terrain, vegetation, size, and/or distribution of roughness characteristics. This methodology could enhance the estimation of

for an area that is larger, as a larger area (>100 m) will tend to have more variations than a small area (<10 m), such as sites used within this study.