3.5. Visualisation Results

- 2.

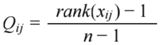

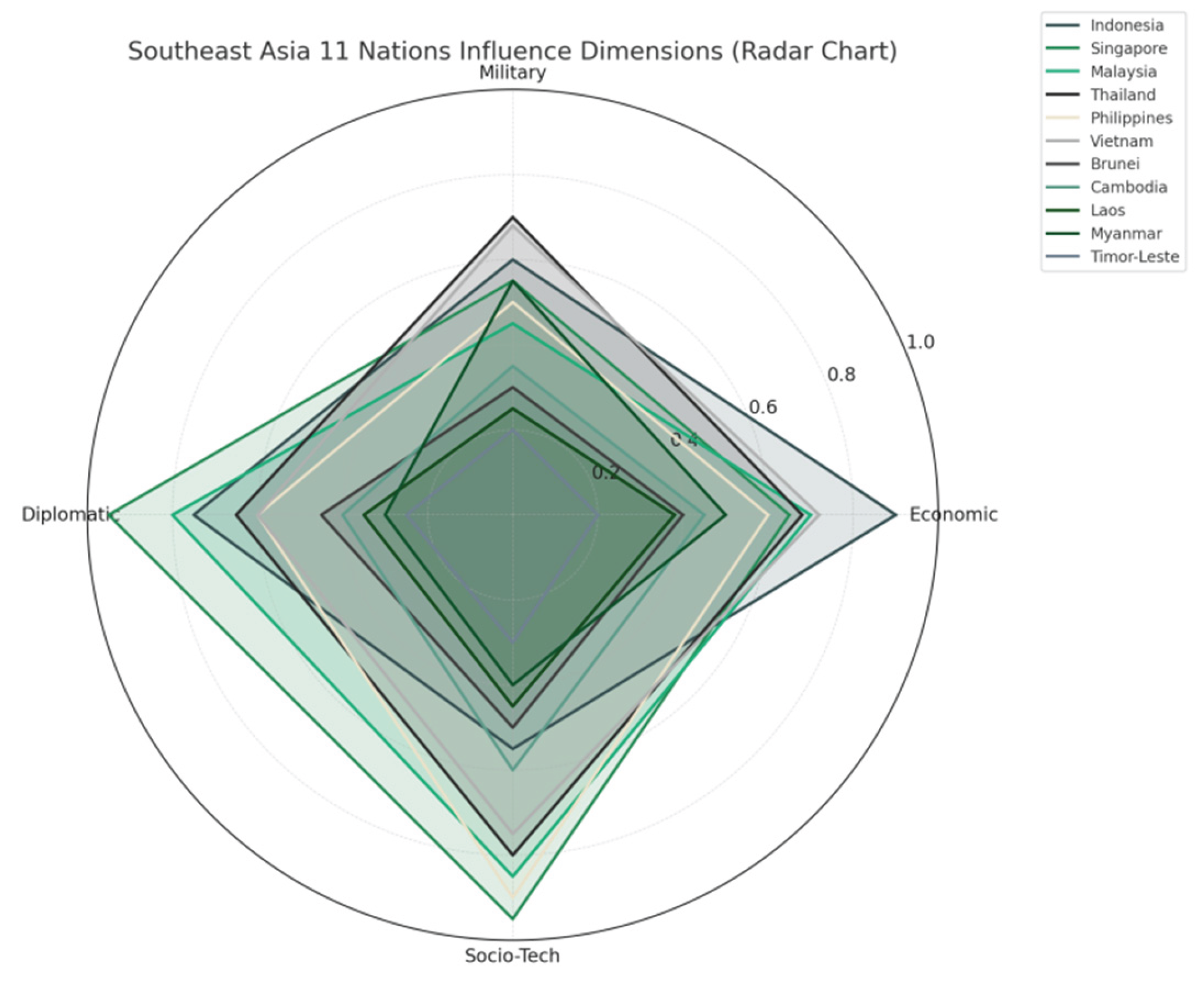

Radar chart: Indonesia stands out in the economic dimension, Singapore in the diplomatic and socio-technical dimension, and Thailand is stronger in the military dimension.

- 3.

Heat map: The midstream countries show “patchy” performance in different dimensions, while Indonesia and Singapore show “comprehensive” performance.

- 4.

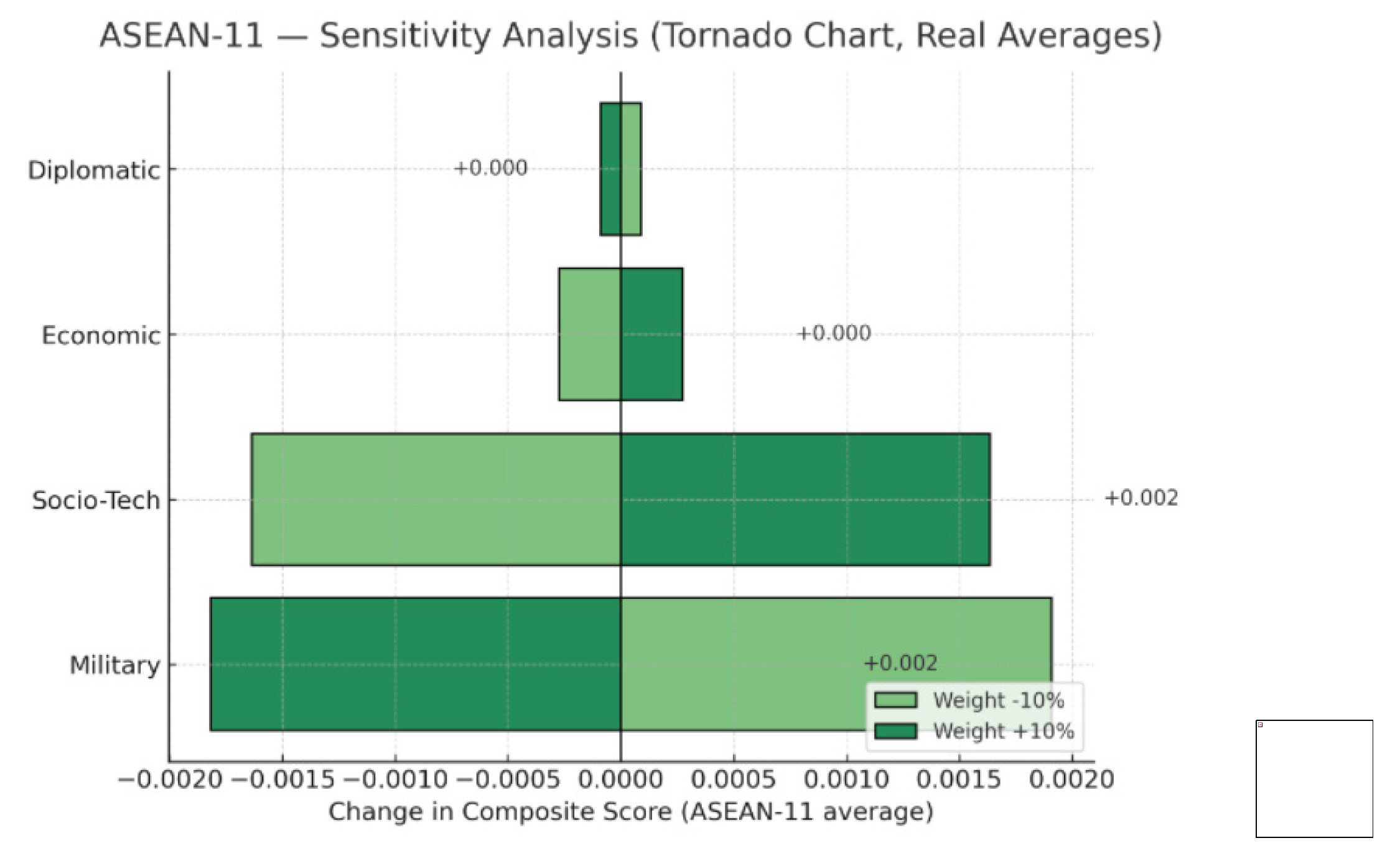

Tornado chart of sensitivities: the 11-country average chart shows that the economic dimension has the greatest impact on the index, followed by military, socio-scientific and diplomatic, and that the sensitivities of each country are listed separately and can be used as reference data for important decisions

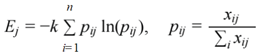

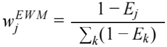

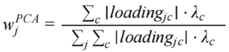

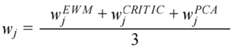

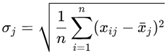

Table 1.

Mean sensitivity tornado map for 11 countries in South-East Asia (based on four-dimensional ±10 per cent disturbance).

Table 1.

Mean sensitivity tornado map for 11 countries in South-East Asia (based on four-dimensional ±10 per cent disturbance).

| Dimension (math.) |

ΔScore (-10%) |

ΔScore (+10%) |

Impact Magnitude |

Swing,|+10% − -10%| |

| Militarily |

0.001909 |

-0.001818 |

0.004702 |

0.003727 |

| Social technology |

-0.001636 |

0.001636 |

0.005140 |

0.003273 |

| Economics |

-0.000273 |

0.000273 |

0.003223 |

0.000545 |

| Diplomacy |

0.000091 |

-0.000091 |

0.002827 |

0.000182 |

The horizontal axis represents the change in composite scores. Left side (light green): Impact of a 10% decrease in dimension weight. Right side (dark green): Impact of a 10% increase in dimension weight.

This chart illustrates the average sensitivity of the 11 ASEAN nations (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Timor-Leste) across four dimensions (economic, diplomatic, military, socio-technological) of the Soft Power Index (SAII). The bars indicate the range of change in the composite score when the weight is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars represent score decreases when the weight is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars represent score increases when the weight is increased by 10%. The results show: The military dimension and the socio-technological dimension exhibit the highest average sensitivity, both reaching approximately ±0.002, indicating these two dimensions are the primary drivers of Southeast Asia’s overall influence. The average sensitivity of the economic dimension is relatively low, exhibiting only minor fluctuations. The diplomatic dimension shows almost no significant change, indicating that, on average, diplomatic factors have a minor impact on the composite score. Overall, the influence structure of the 11 Southeast Asian nations presents a “dual-engine model driven by military and socio-technological factors, with economics playing a secondary role and diplomacy having marginal influence.” This conclusion highlights the shared reliance of regional nations on hard power and socio-technological development.

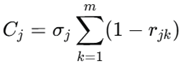

Figure 1.

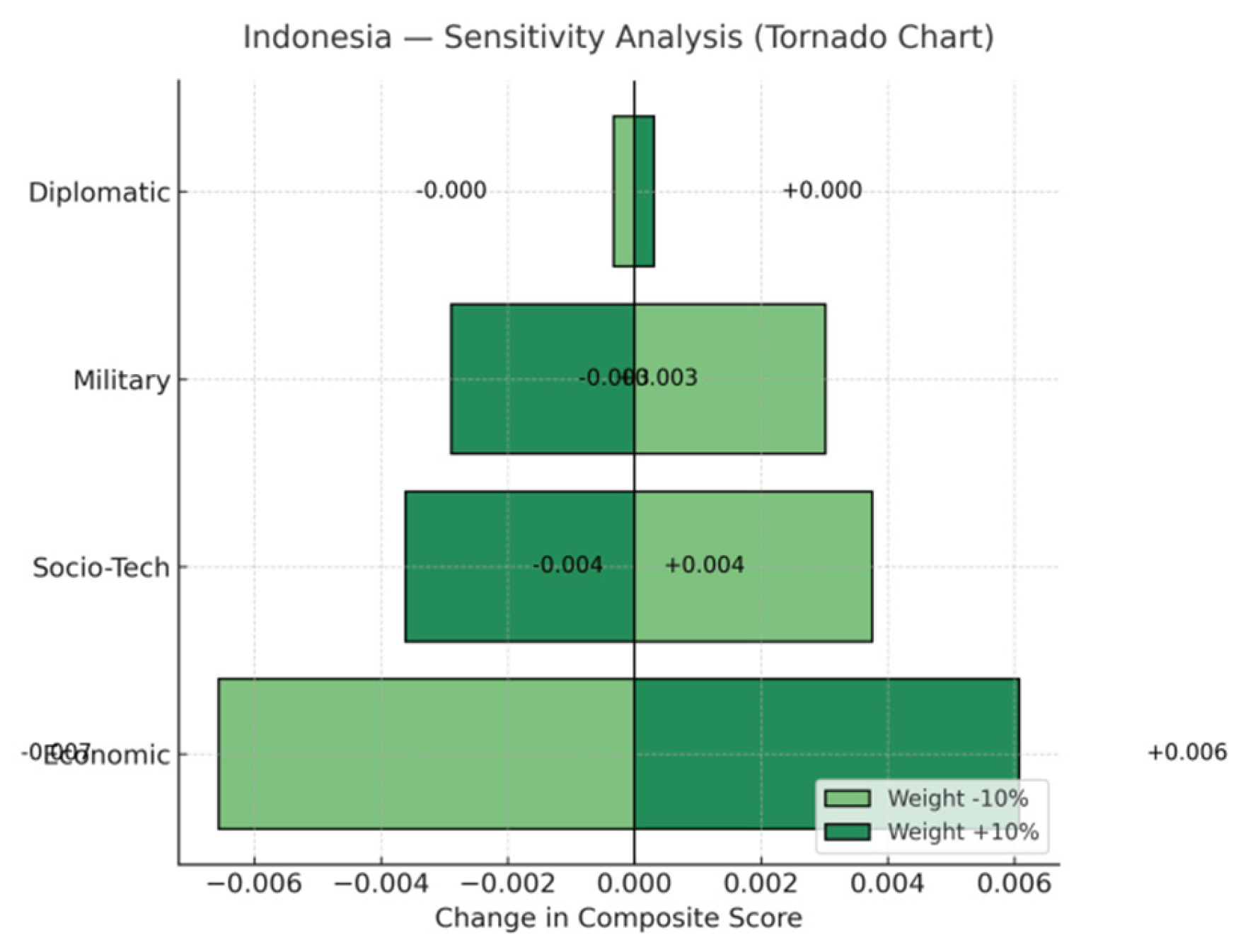

Indonesia - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 1.

Indonesia - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This tornado chart illustrates the sensitivity of Indonesia’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to ±10% changes in the weights of its four dimensions: economic, military, socio-technological, and diplomatic. Horizontal bars indicate the range of score variation, with light green bars representing score decreases when a dimension’s weight is reduced by 10%, and dark green bars indicating score increases when a dimension’s weight is increased by 10%. Among the four dimensions, the economy exerts the greatest influence, with the composite score fluctuating by approximately ±0.006. This is followed by socio-technology (±0.004) and military (±0.003). The diplomatic dimension exhibits the least sensitivity. This indicates that Indonesia’s influence index is structurally dominated by economic performance, with socio-technology and military capabilities playing secondary roles.

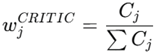

Figure 2.

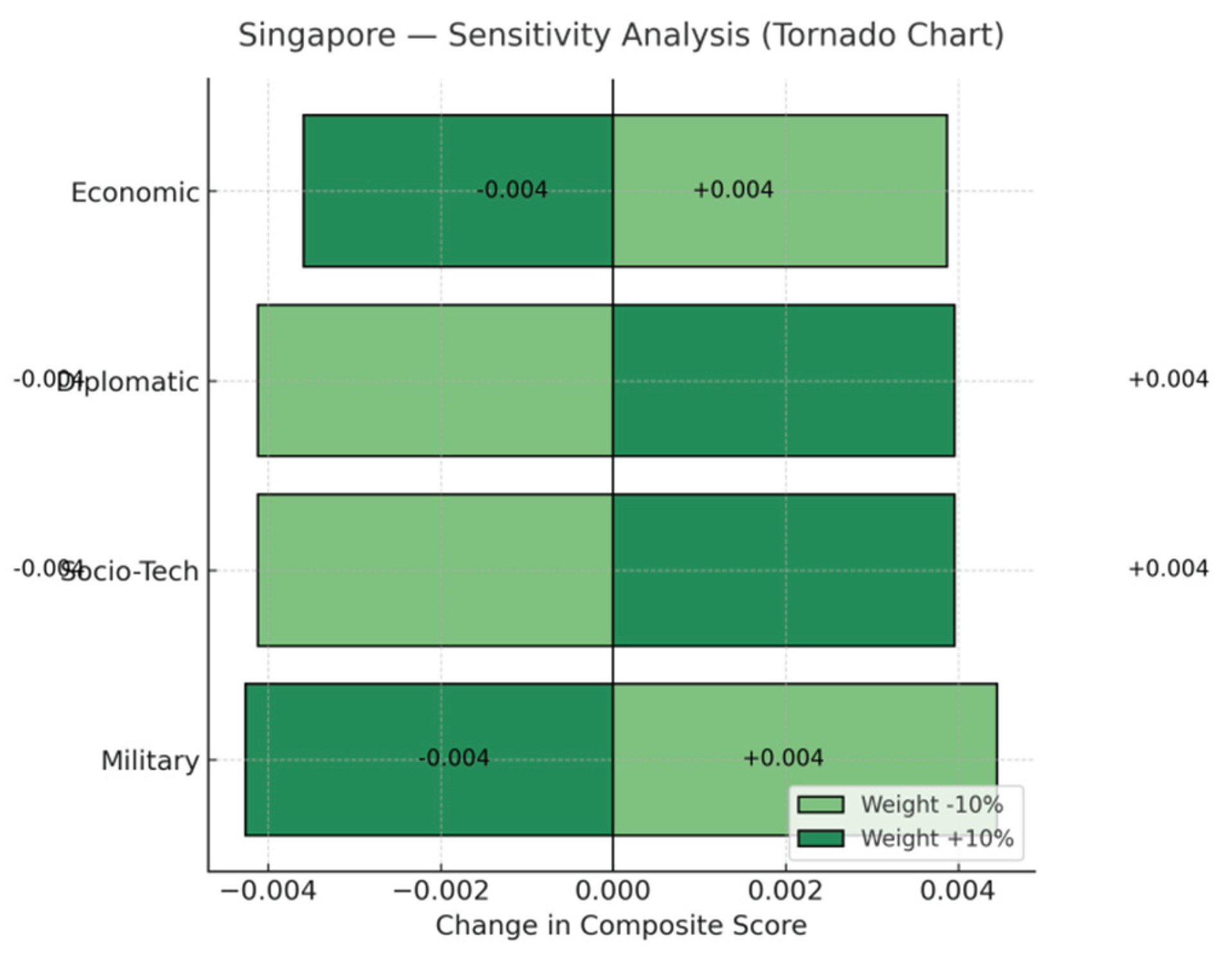

Singapore - Sensitivity analysis of the Southeast Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 2.

Singapore - Sensitivity analysis of the Southeast Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Singapore’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. The bars indicate the range of composite score variation when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars represent score declines when weights decrease by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when weights rise by 10%. The results indicate that Singapore exhibits broadly consistent sensitivity across the economic, diplomatic, socio-technological, and military dimensions, with each showing a sensitivity range of approximately ±0.004. This suggests a relatively balanced structure in its composite score. Compared to Indonesia, Singapore’s index does not rely on any single dimension but instead achieves comprehensive influence through balanced development across multiple dimensions.

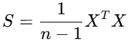

Figure 3.

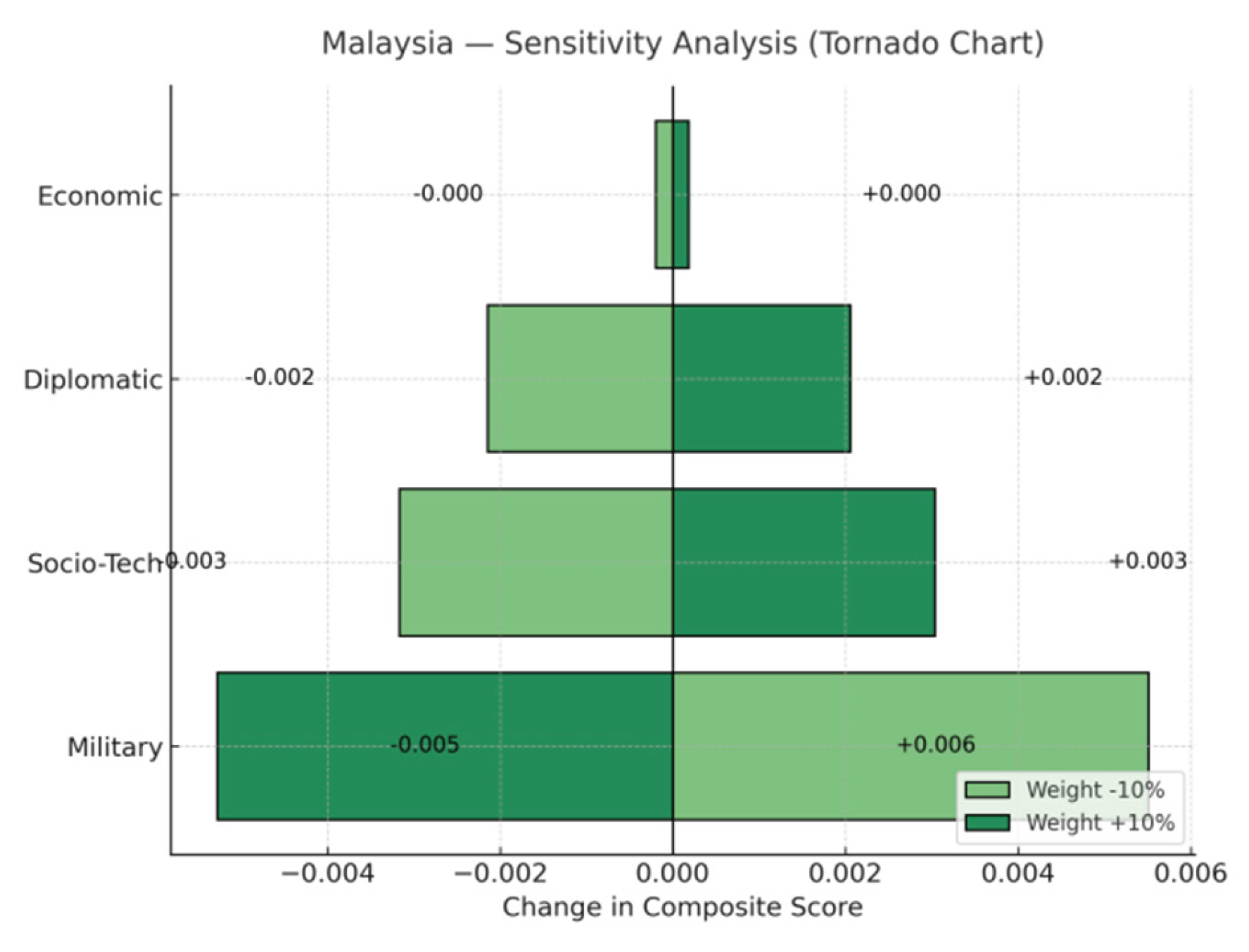

Malaysia - Sensitivity analysis of the Southeast Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 3.

Malaysia - Sensitivity analysis of the Southeast Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Malaysia’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to shifts in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score declines with a 10% weight reduction, while dark green bars show score increases with a 10% weight increase. Results reveal that the military dimension exerts the greatest impact on the composite score, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.006; followed by the socio-technological dimension at approximately ±0.003; the diplomatic dimension has a relatively minor impact at around ±0.002; while the economic dimension exerts virtually no significant influence. Overall, Malaysia’s influence structure exhibits high dependence on the military dimension, indicating its strategic security sensitivity in the regional context far exceeds that of economic and diplomatic spheres.

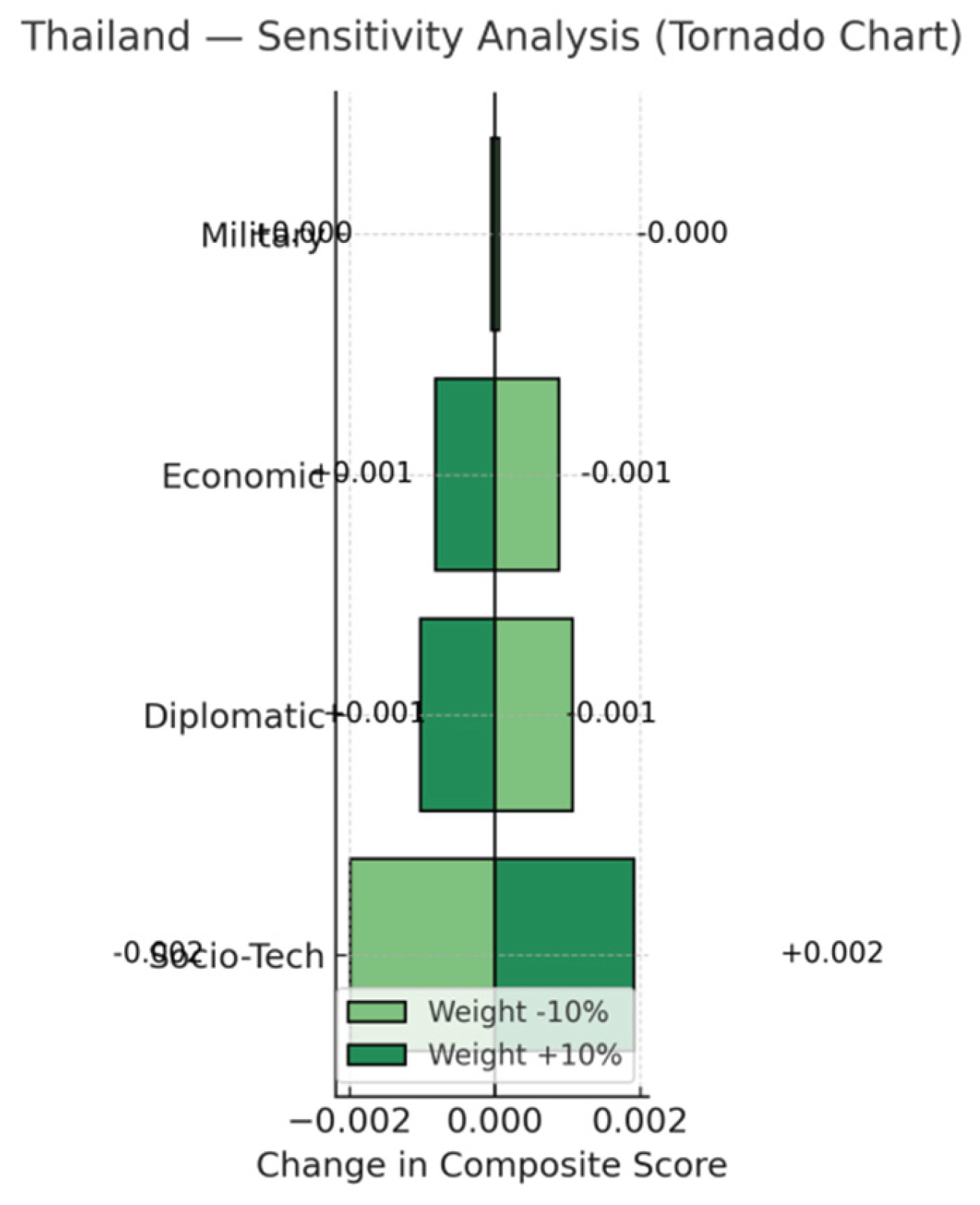

Figure 4.

Thailand - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 4.

Thailand - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Thailand’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate Thailand’s composite score is most sensitive to the socio-technological dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.002. The economic and diplomatic dimensions follow, each showing sensitivity of about ±0.001. The military dimension exerts negligible impact. Overall, Thailand’s index structure is primarily driven by social and technological development. While economic and diplomatic factors contribute, their influence remains relatively limited, demonstrating that Thailand’s comprehensive influence relies heavily on social and technological elements.

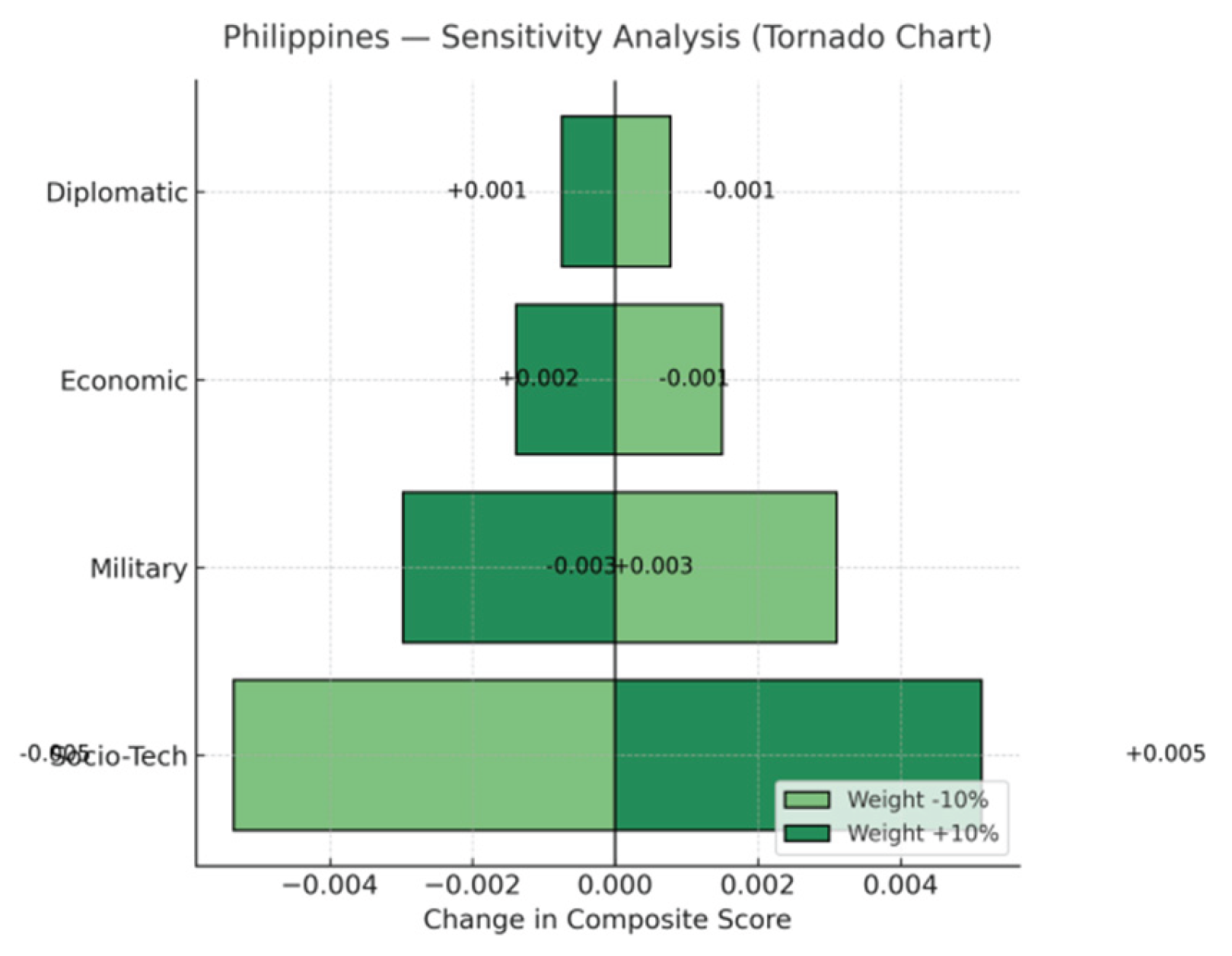

Figure 5.

Philippines - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 5.

Philippines - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of the Philippines’ composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate that the Philippines’ composite score is most sensitive to the socio-technological dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.005, highlighting the critical role of social and technological development in national influence. The military dimension follows with sensitivity of about ±0.003, suggesting security and defense still carry significant weight. The economic dimension exhibits moderate sensitivity, ranging from ±0.001 to ±0.002. The diplomatic dimension shows the weakest sensitivity, at only ±0.001. Overall, the Philippines’ influence index structure is highly dependent on social and technological development, with secondary contributions from military and economic factors.

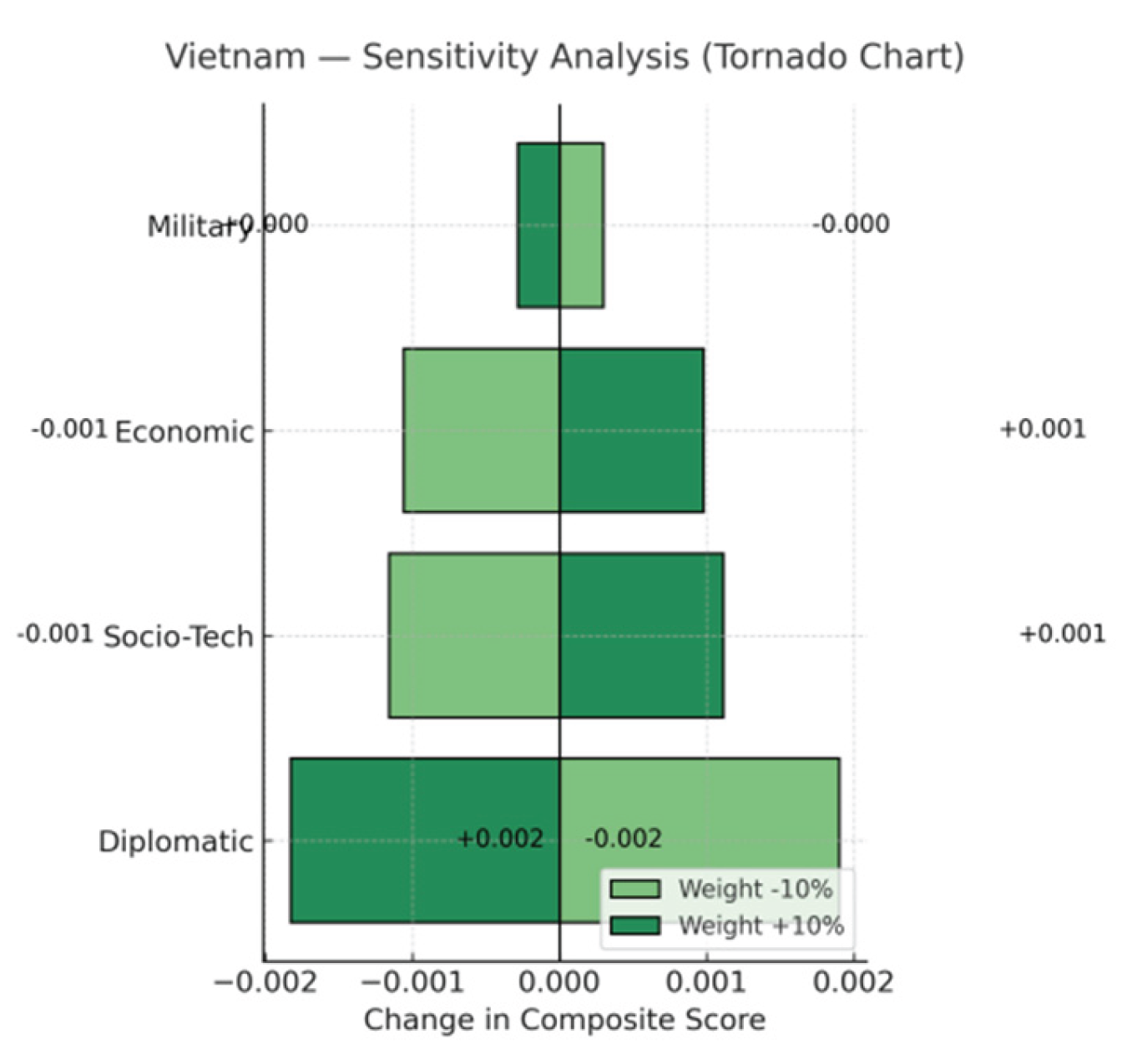

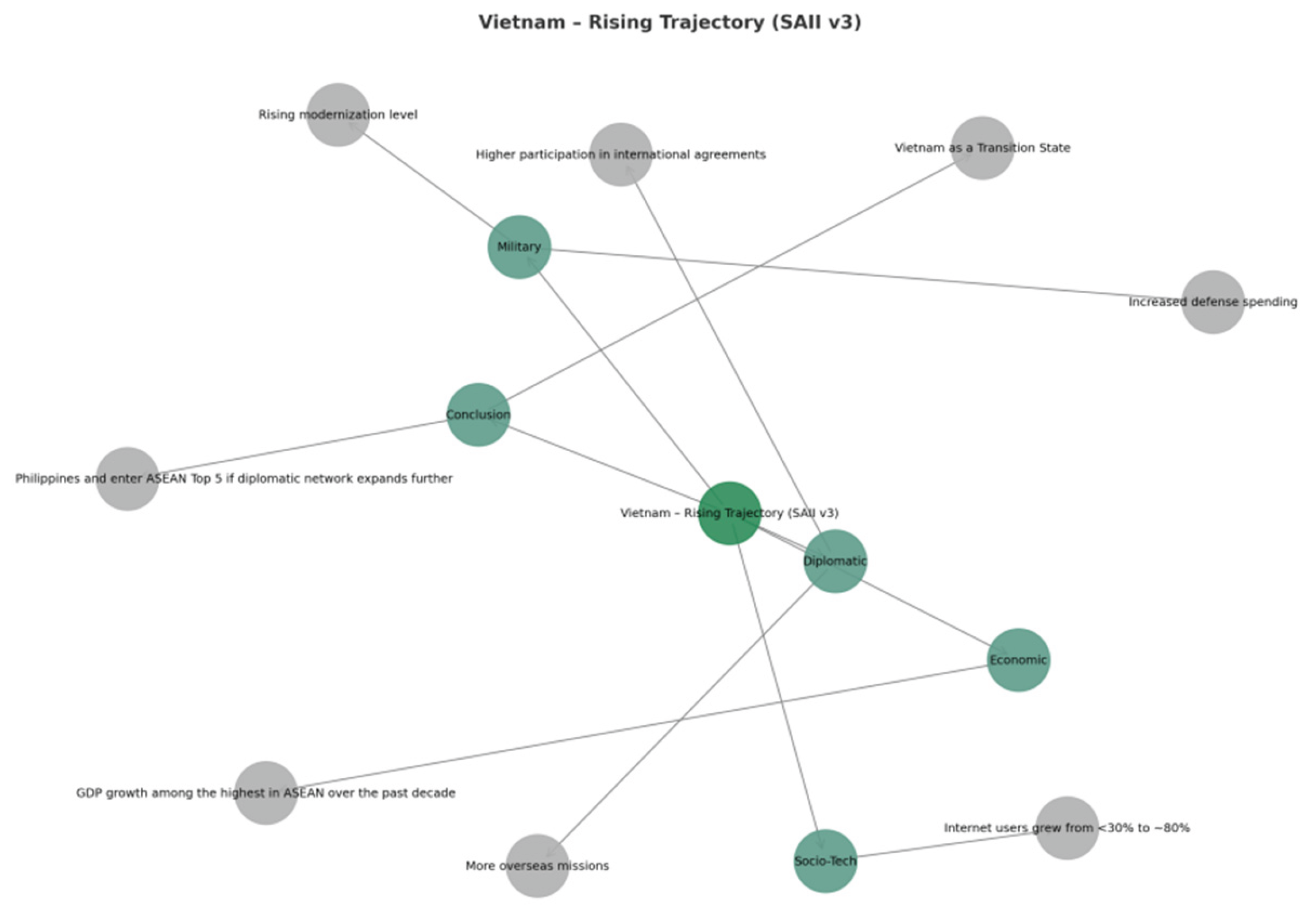

Figure 6.

Viet Nam - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 6.

Viet Nam - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Vietnam’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate that Vietnam’s composite score is most sensitive to the diplomatic dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.002. This highlights the critical role of regional standing and international cooperation in shaping national influence. The economic and socio-technological dimensions follow with sensitivity levels of approximately ±0.001 each. The military dimension exerts negligible impact. Overall, Vietnam’s influence structure relies heavily on diplomatic outreach and international partnerships, supported by economic and socio-technological development.

Figure 7.

Brunei - Southeast Asia Impact Index Sensitivity Analysis (Tornado Chart).

Figure 7.

Brunei - Southeast Asia Impact Index Sensitivity Analysis (Tornado Chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Brunei’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to weight adjustments across four dimensions. Each bar represents the composite score range when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score declines with a 10% weight reduction, while dark green bars show score increases with a 10% weight increase. Results indicate Brunei’s composite score is most sensitive to the military dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.002. This highlights the nation’s high dependence on limited yet critical military security factors for its influence. The socio-technological dimension follows with sensitivity of approximately ±0.002, reflecting the significant complementary role of society and technology in overall influence. The diplomatic dimension exhibits lower sensitivity at only ±0.001, while the economic dimension has negligible impact. Overall, Brunei’s influence structure exhibits characteristics of “military and socio-technological dominance with low economic dependency.”

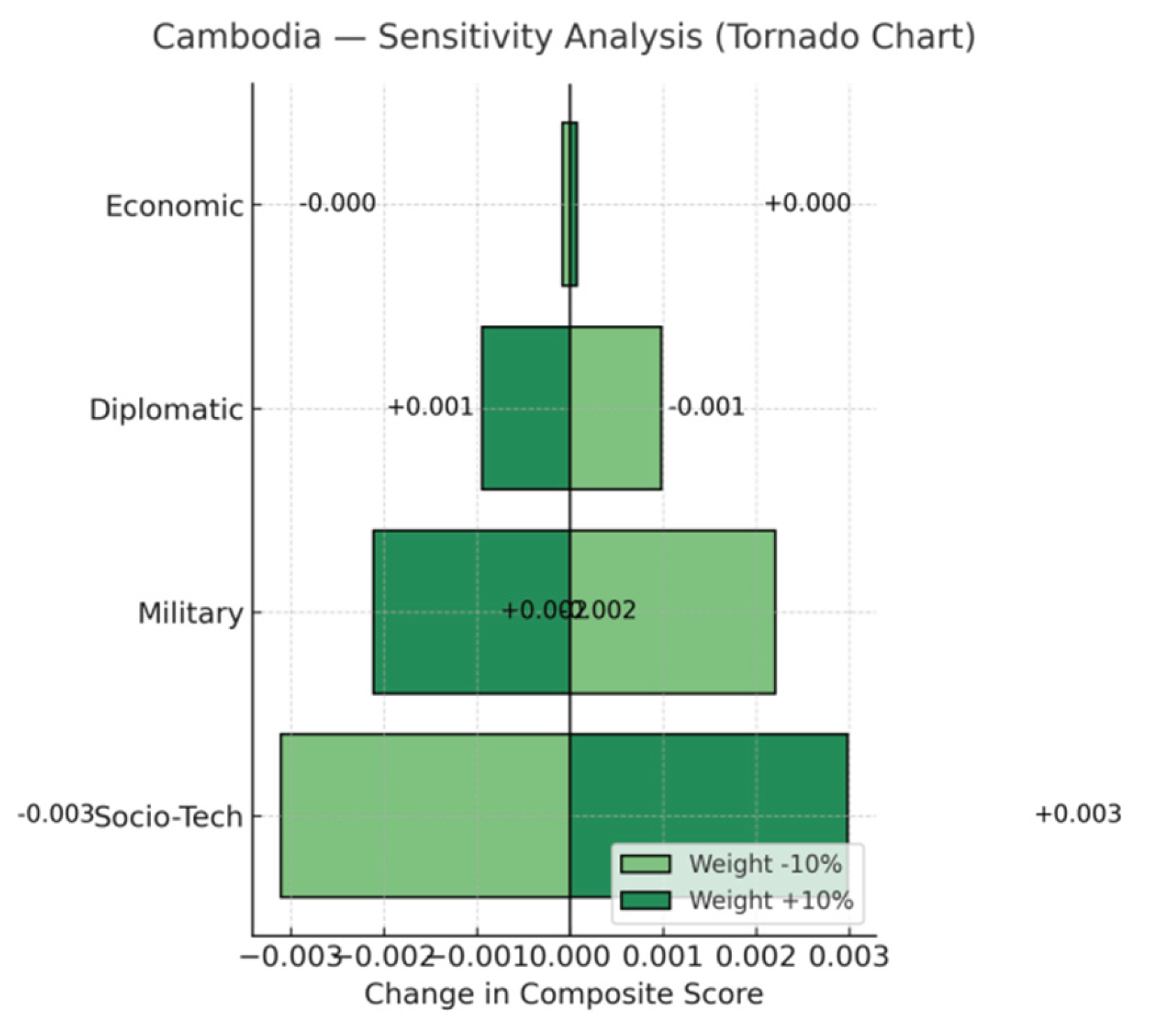

Figure 8.

Cambodia - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 8.

Cambodia - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates Cambodia’s sensitivity to changes in the weighting of four dimensions within the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) and their impact on the composite score. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate Cambodia’s composite score is most sensitive to the socio-technological dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.003, suggesting its national influence primarily relies on social and technological development factors. The military dimension follows with sensitivity around ±0.002. The diplomatic dimension has a relatively minor impact, only approximately ±0.001, while the economic dimension exerts negligible influence. Overall, Cambodia’s influence structure exhibits characteristics of “socio-technological dominance, military support, and low economic dependence.”

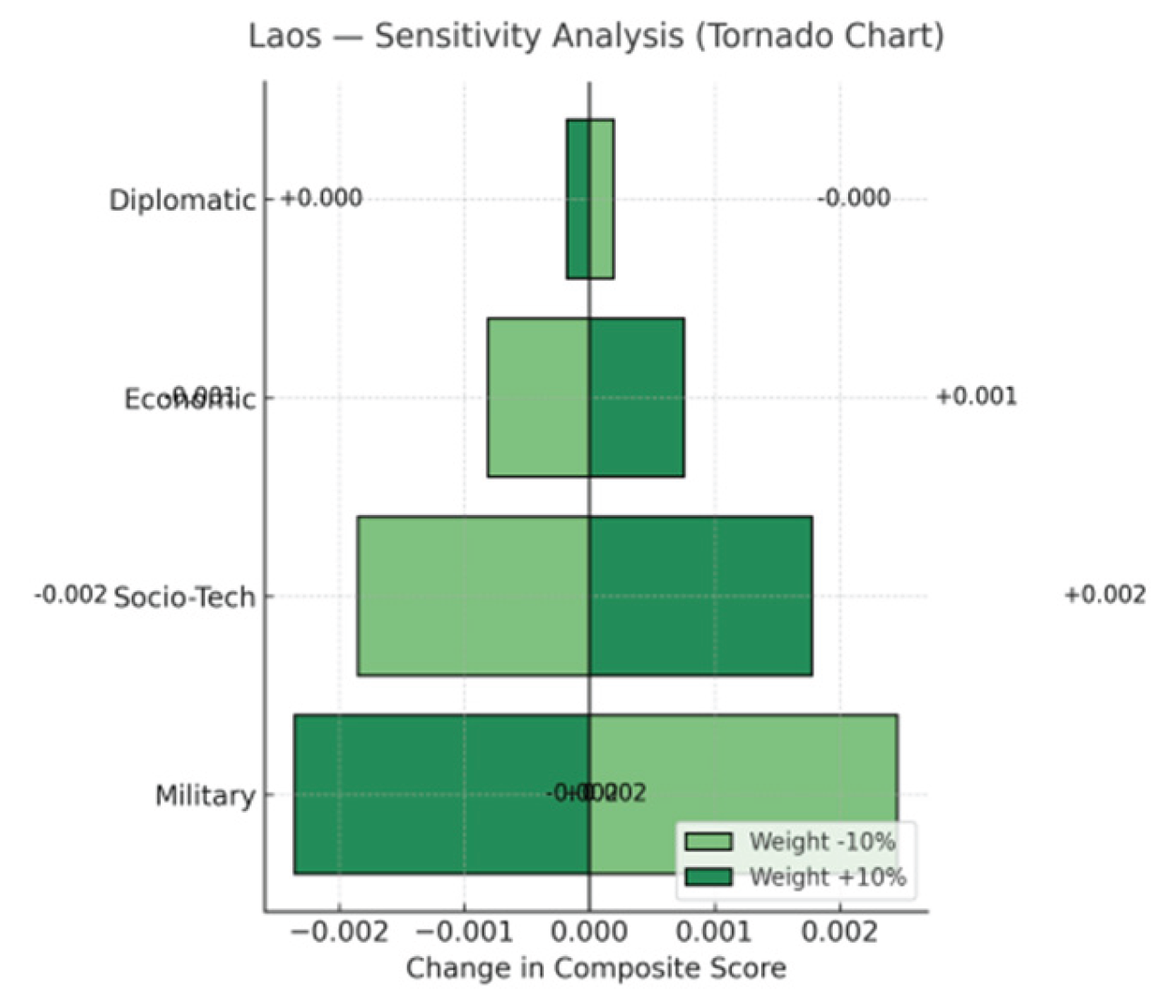

Figure 9.

Laos - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 9.

Laos - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Laos’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate that Laos’s composite score is most sensitive to the military dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.002, reflecting its national influence heavily reliant on limited yet critical military factors. The socio-technical dimension follows with sensitivity around ±0.002. The economic dimension has a smaller impact at approximately ±0.001, while the diplomatic dimension exerts negligible influence. Overall, Laos’ influence structure exhibits characteristics of “military and socio-technical dominance, limited economic impact, and low diplomatic dependency.”

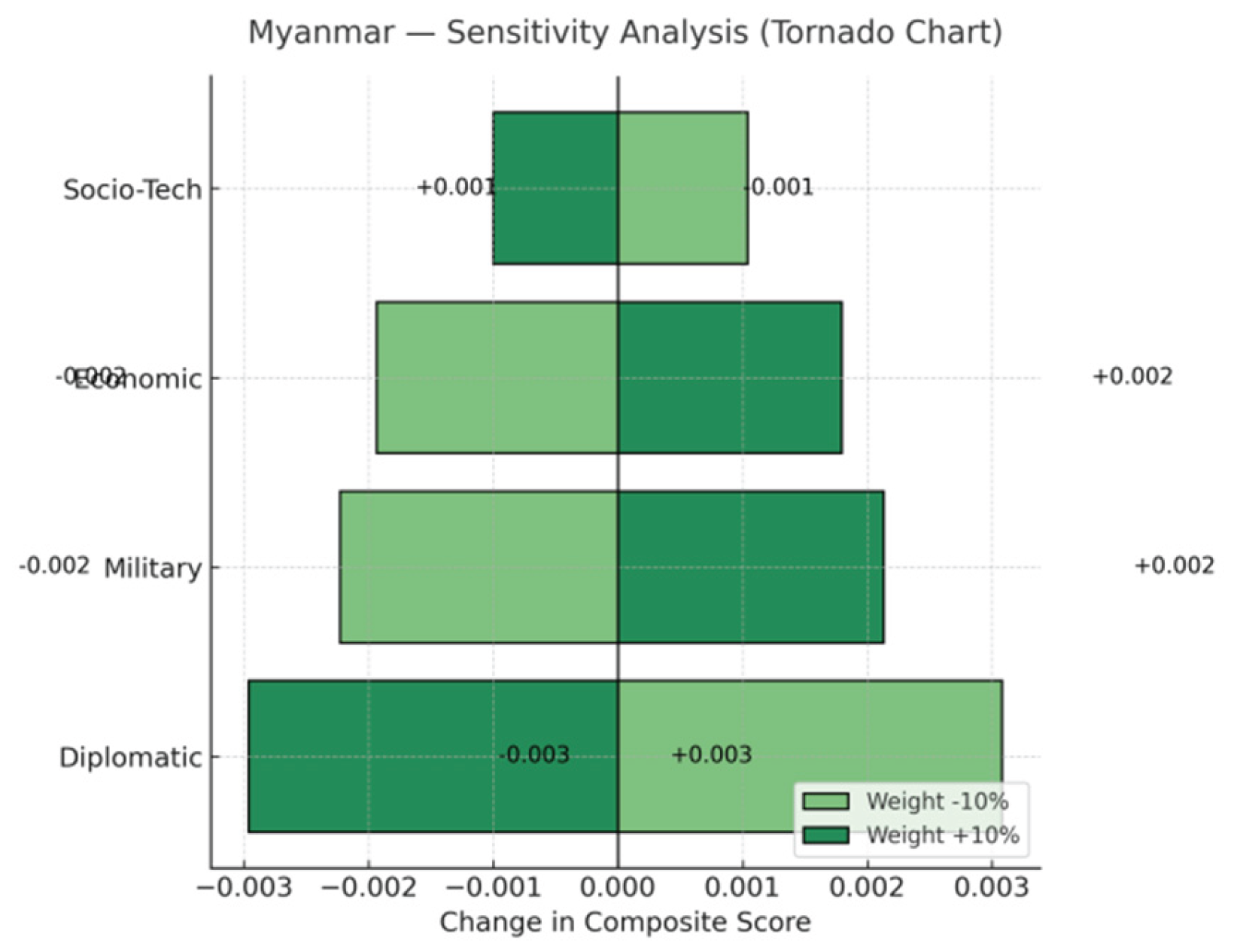

Figure 10.

Myanmar - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

Figure 10.

Myanmar - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado chart).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Myanmar’s composite score in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII) to changes in the weighting of its four dimensions. Each bar represents the range of composite score variation when the weighting is adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when the weighting is reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when the weighting is increased by 10%. Results indicate Myanmar’s composite score is most sensitive to the diplomatic dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.003, highlighting the dominant role of international relations and regional cooperation in its national influence. The economic and military dimensions follow with sensitivity levels of approximately ±0.002 each. while the socio-technical dimension has the least impact, with sensitivity of only ±0.001. Overall, Myanmar’s influence structure exhibits characteristics of “diplomacy as the primary driver, supported by economics and military, with limited socio-technical underpinnings.”

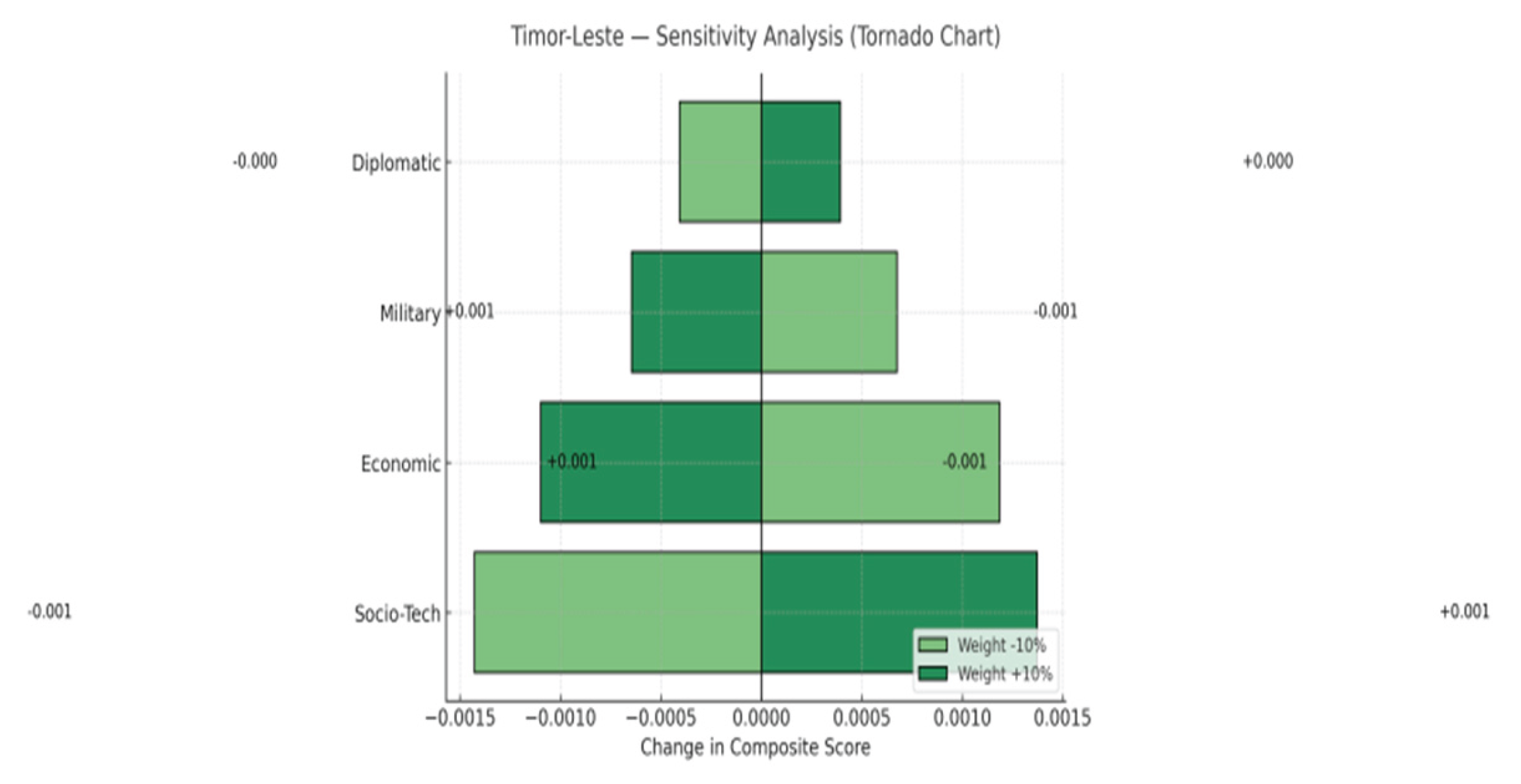

Figure 11.

Timor-Leste - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado diagram).

Figure 11.

Timor-Leste - Sensitivity analysis of the South-East Asia Impact Index (tornado diagram).

This chart illustrates the sensitivity of Timor-Leste’s composite score to weight adjustments across four dimensions in the Southeast Asia Influence Index (SAII). Each bar represents the composite score range when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars indicate score decreases when weights are reduced by 10%, while dark green bars show score increases when weights are raised by 10%. Results indicate that Timor-Leste’s composite score is most sensitive to the socio-technical dimension, with fluctuations of approximately ±0.0015. This demonstrates that the nation’s influence is highly dependent on advancements in social development and technological capabilities. The economic dimension follows with sensitivity around ±0.001. The military dimension has a relatively minor impact, at only ±0.001. The diplomatic dimension exerts negligible influence. Overall, Timor-Leste’s influence structure exhibits characteristics of being primarily driven by socio-technical factors, followed by economic factors, with limited roles played by military and diplomatic factors.

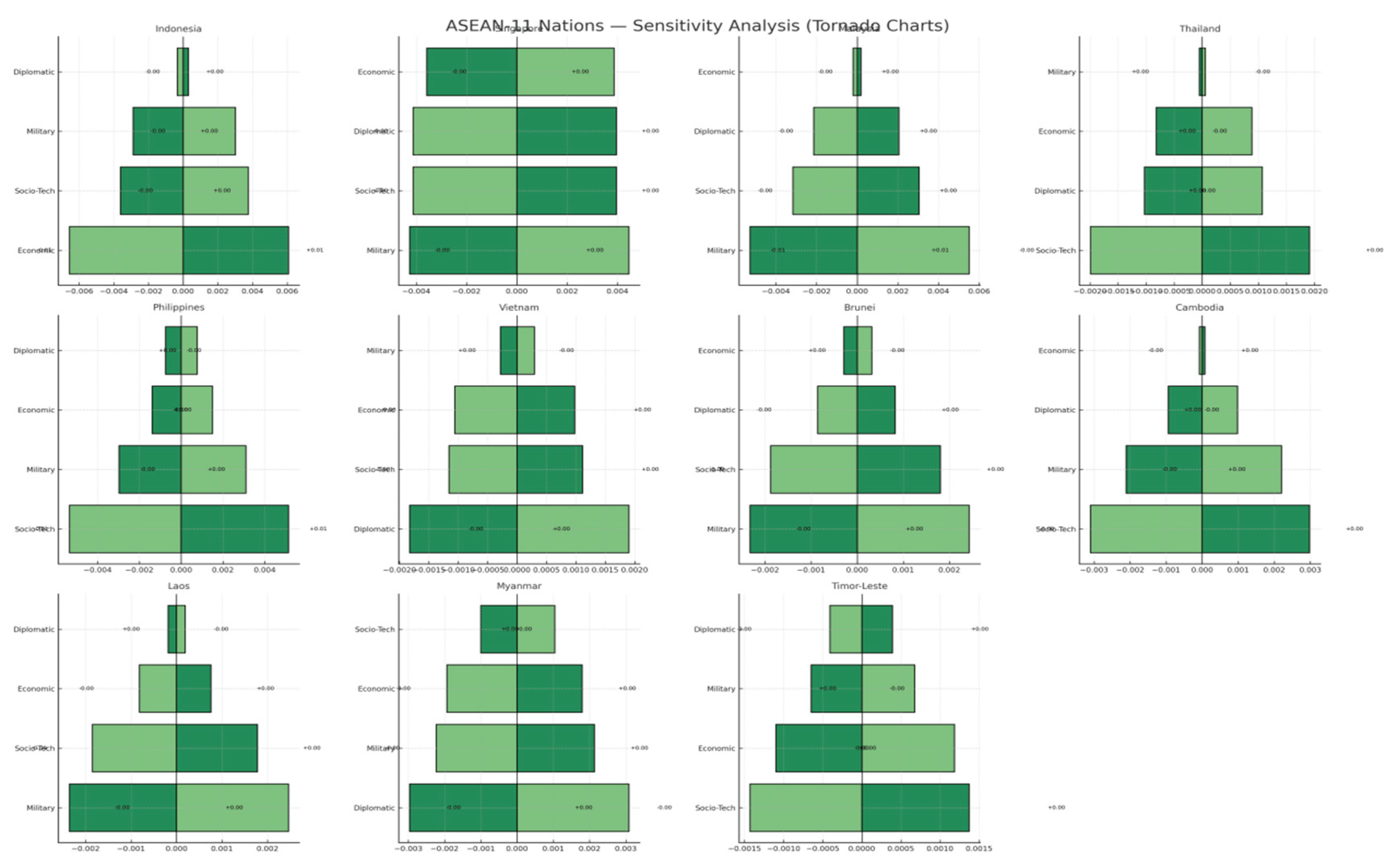

Figure 12.

11 countries in South-East Asia - impact index sensitivity analysis (tornado chart overview). This chart comprehensively displays the sensitivity analysis results across four dimensions (economic, diplomatic, military, and socio-technological) of the Southeast Asian 11 Countries (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, East Timor) within the Southeast Asian Influence Index (SAII). Each sub-chart indicates the range of composite score changes when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars represent score decreases when weights are reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when weights are raised by 10%.

Figure 12.

11 countries in South-East Asia - impact index sensitivity analysis (tornado chart overview). This chart comprehensively displays the sensitivity analysis results across four dimensions (economic, diplomatic, military, and socio-technological) of the Southeast Asian 11 Countries (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, East Timor) within the Southeast Asian Influence Index (SAII). Each sub-chart indicates the range of composite score changes when weights are adjusted by ±10%: light green bars represent score decreases when weights are reduced by 10%, while dark green bars indicate score increases when weights are raised by 10%.

Overall trends reveal:

The economic dimension stands out in Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines, serving as a key driver of composite score fluctuations.

The diplomatic dimension is most sensitive in Vietnam and Myanmar, reflecting the core role of regional cooperation and international relations in shaping these nations’ influence.

The military dimension exhibits higher sensitivity in Malaysia, Brunei, and Laos, indicating that limited yet critical military capabilities form a vital foundation for their influence.

The socio-technological dimension proved most critical in the Philippines, Cambodia, and Timor-Leste, demonstrating the significant propulsive effect of social development and technological advancement on overall national influence.

Overall, Southeast Asian nations exhibit diverse pathways to influence formation: some rely on economic and diplomatic expansion (e.g., Singapore, Vietnam), others on military security (e.g., Brunei, Laos), while others demonstrate heightened sensitivity in social and technological development (e.g., Philippines, Cambodia, Timor-Leste). This outcome highlights the heterogeneity and complementarity within ASEAN’s national influence structures.

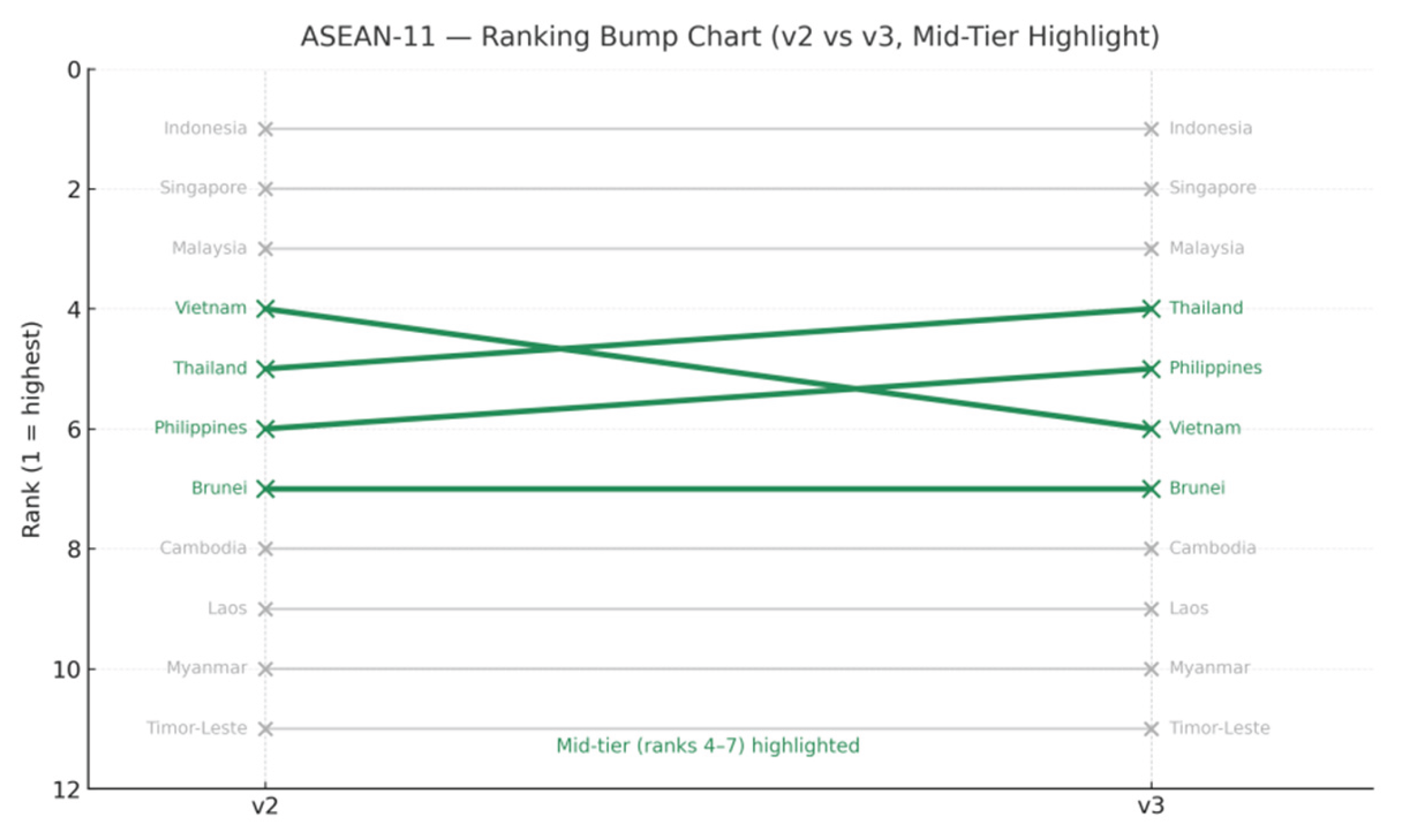

- 5.

Bump Chart: Illustrates the subtle ranking differences between v2 and v3 in mid-tier countries.

Figure 13.

Southeast Asia 11 - V2 vs. V3 Ranking Streamline Comparison (Midstream Countries Highlighted).

Figure 13.

Southeast Asia 11 - V2 vs. V3 Ranking Streamline Comparison (Midstream Countries Highlighted).

This chart illustrates the ranking shifts among the 11 ASEAN nations in the Influence Index versions V2 and V3, with a focus on changes among mid-tier countries (ranks 4 to 7). Vietnam dropped from 4th to 6th place, Thailand rose from 5th to 4th, the Philippines climbed from 6th to 5th, while Brunei remained unchanged at 7th. The top tier (Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia) and bottom tier (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Timor-Leste) maintained overall stable rankings. The results indicate that V3, following methodological refinements over V2 (multi-method weighting and robustness testing), elevates the rankings of countries with more balanced overall structures (Thailand, Philippines) while lowering those of countries relying on single-dimensional strengths (Vietnam).

During the iterative development of SAII, V2 served as the prototype version. It employed single-weighting and simple standardization methods, enabling rapid process execution and reasonable ranking. However, it exhibited limitations in robustness and originality. V3 builds upon this foundation by introducing multi-method integrated weighting (EWM, CRITIC, PCA), a three-stage standardization chain, and robustness tests using Bootstrap and Kendall’s Tau. These enhancements significantly elevate the index’s scientific rigor and auditability. Comparative results show that rankings for leading and trailing nations remain largely stable, while mid-tier countries exhibit minor shifts: Thailand and the Philippines rise due to enhanced structural balance, while Vietnam declines slightly as its single-dimensional advantage weakens. This divergence demonstrates V3’s superior ability to highlight the influence characteristic of “multi-dimensional synergistic drivers.” This finding aligns with sensitivity analysis results, confirming that military strength and socio-technical capabilities are the drivers with the most significant marginal effects.

Interpreting Regional Dynamics

This section aims to move beyond mere numerical rankings by interpreting SAII v3 findings through the lens of regional political-economic structures. By comparing performance across four primary dimensions, we can outline Southeast Asia’s overall influence landscape.

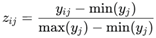

1) Stability of the “One Major Power, Two Medium Powers” Structure

Indonesia, as Southeast Asia’s largest economy, consistently ranks first across all methodologies. This outcome stems not only from its economic scale but also from its geopolitical position (as a hub connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans), population size (approximately 270 million), and leading role in ASEAN affairs. Indonesia’s dominant position remains unchallenged regardless of whether v2’s expert mapping weights or v3’s pure algorithmic weights are applied, indicating that its regional influence has established long-term structural advantages.

Singapore and Malaysia form a “two mediums” pattern. Singapore demonstrates “hard and soft power” characteristics through its highly globalized diplomatic and financial hub status; Malaysia achieves balanced development across all four dimensions, ranking mid-to-high. While lacking a single dominant strength, it exhibits strong overall resilience. This “one strong, two mediums” pattern reflects Southeast Asia’s multipolar trend.

2 )Competition and Vulnerabilities Among Mid-Tier Nations

Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam form a “deadlocked” group in the rankings, with minimal gaps in their composite scores and distinct strengths and weaknesses across dimensions:

Thailand: Excels in military strength and tourism/cultural appeal, but political instability diminishes its diplomatic influence.

Philippines: Possesses clear advantages in internet infrastructure and population size, but economic and diplomatic shortcomings constrain its upward potential.

Vietnam: Demonstrates robust economic growth and accelerated military modernization, yet faces limitations in its diplomatic network.

Bootstrap tests reveal significant overlap in the ranking intervals for these three nations, indicating any one could achieve a “leap forward” in the coming years through breakthroughs in specific dimensions—but also carries the risk of “decline.”

3)Structural Challenges for Peripheral Nations

Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Brunei, and Timor-Leste rank in the lower tier of the composite index. This stems not from lagging in a single dimension but from constraints across multiple dimensions.

Despite high GDP per capita, Brunei’s limited population and market size constrain its regional influence.

Cambodia and Laos have shown improvements in internet penetration and economic openness, yet their overall scale remains constrained.

Myanmar suffers significant losses across economic, diplomatic, and social-technological dimensions due to political instability.

Timor-Leste remains in its nation-building phase, with data hovering near the lower bounds across most indicators.

A common trait among these nations is the absence of breakthroughs across multiple dimensions. Even when excelling in a single area—such as Brunei’s per capita income—they struggle to translate this advantage into regional influence.

4) Leapfrog Opportunities in the Social Technology Dimension

Unlike hard power domains like economics and military strength, which require long-term accumulation, the social technology dimension—particularly internet penetration and digital infrastructure—offers smaller nations potential opportunities for leapfrog development. For example:

The Philippines’ high internet penetration enhances its social connectivity;

Vietnam’s development in the digital economy and e-commerce adds to its strengths;

Cambodia and Laos’ rapid progress in mobile internet penetration has led to the fastest improvement in their social technology scores.

This demonstrates that in the digital age, Southeast Asian nations can swiftly elevate their relative standing in regional influence through relatively low-cost technological investments.