Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gazpacho

2.1.1. High-Pressure Processing (HPP)

2.1.2. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment (PEF)

2.1.3. Low-Temperature Pasteurised Gazpacho (LP)

2.1.4. Freshly-Prepared Gazpacho (FP)

2.2. Participants and Study Design

2.3. Carotenoid Analysis in Gazpacho and Serum

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPP | High pressure processing |

| PEF | Pulsed electric field |

| LP | Low-pasteurised |

| FP | Freshly prepared |

References

- UNESCO. Gazpacho. Available online: https://mediterraneandietunesco.org/gazpacho/ Accessed on 1 September 2025.

- Medina-Remón, A.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Arranz, S.; Ros, E.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Sacanella, E.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; et al. Gazpacho consumption is associated with lower blood pressure and reduced hypertension in a high cardiovascular risk cohort. Cross-sectional study of the PREDIMED trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovas Dis 2013, 23, 944e952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, V.; Bertozzi, B.; Fontana, L. Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018, 2, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campra, P.; Aznar-Garcia, M.J.; Ramos-Bueno, R.P.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, M.J.; Khaldi, H.; Garrido-Cardenas, J.A. A whole-food approach to the in vitro assessment of the antitumor activity of gazpacho. Food Res Internat 2019, 121, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, V.; Temple, N.J.; La Vecchia, C.; Castellan, G.; Tavani, A.; Guercio, V. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Eur J Nutr 2019, 58, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, E.J.; Bowyer, C.; Tsouza, A.; Chopra, M. Tomatoes: An Extensive Review of the Associated Health Impacts of Tomatoes and Factors That Can Affect Their Cultivation. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde Méndez, C.M.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, E.M.; Díaz Romero, C.; Matallana González, M.C.; Torija Isasa, M.E. Comparison of the mineral and trace element concentrations between ‘gazpacho’ and the vegetables used in its elaboration. Internat J Food Sci Nutr 2008, 59, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde Méndez, C.M.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, E.M.; Díaz Romero, C.; Sánchez Mata, M.C.; Matallana González, M.C.; Torija Isasa, M.E. Vitamin C and organic acid contents in Spanish “Gazpacho” soup related to the vegetables used for its elaboration process. CyTA - Journal of Food 2011, 91, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Osorio, C.; Vargas-Murga, L.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Comprehensive database of carotenoid contents in ibero-american foods. A valuable tool in the context of functional foods and the establishment of recommended intakes of bioactives. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 5055–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viña, I.; Robles, A.; Viña, J.R. Association Between Lycopene and Metabolic Disease Risk and Mortality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA – Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Consumo de gazpacho según los datos del panel de consumo alimentario. News 10 August Available on-line at https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/prensa/ultimas-noticias/detalle_noticias/el-consumo-de-gazpacho-y-salmorejo-preparados-aumenta-un-10-1--en-2023--con-una-facturacion-de-178-96-millones-de-euros/bc2b1537-1c5a-4f1a-8662-996e0a0bdfa4 Accessed 29 August 2025.

- Estévez-Santiago, R.; Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of dietary lutein, zeaxanthin and lycopene intakes and sources in the Spanish survey of dietary intake (2009–2010). Inter J Food Sci Nutr 2016, 67, 3,305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Estévez-Santiago, R.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of dietary vitamin A intake (retinol, a-carotene, b-carotene, b-cryptoxanthin) and its sources in the National Survey of Dietary Intake in Spain (2009–2010). Int J Food Sci Nutr 2015, 66, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Martín, A.; Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Plaza, L.; De Ancos, B.; Cano, P. Effect of vegetable soup gazpacho consumption on vitamin C bioavailability, antioxidant status and inflammatory markers in healthy humans. FASEB J 2004, 18. Dietary Bioactive Components, A907 (Abs 598.9). [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; De Ancos, B.; Plaza, L.; Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Martín, A. Mediterranean vegetable soup consumption increases plasma vitamin C, and decreases F2-isoprostanes, prostaglandin E2, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in healthy humans. J Nutr Biochem 2006, 17, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmero, P.; Lemmens, L.; Ribas-Agustí, A.; Sosa, C.; Met, K.; De Dieu Umutoni, J.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Novel targeted approach to better understand how natural structural barriers govern carotenoid in vitro bioaccessibility in vegetable-based systems. Food Chem 2013, 141, 2036–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilla, A.; Bosch, L.; Barberá, R.; Alegría, A. Effect of processing on the bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds—A review focusing on carotenoids, minerals, ascorbic acid, tocopherols and polyphenols. J Food Compos Anal 2018, 68, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gámez, G.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Recent Advances toward the Application of Non-Thermal Technologies in Food Processing: An Insight on the Bioaccessibility of Health-Related Constituents in Plant-Based Products. Foods 2021, 10, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narra, F.; Piragine, E.; Benedetti, G.; Ceccanti, C.; Florio, M.; Spezzini, J.; Troisi, F.; Giovannoni, R.; Martelli, A.; Guidi, L. Impact of thermal processing on polyphenols, carotenoids, glucosinolates, and ascorbic acid in fruit and vegetables and their cardiovascular benefits. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2024, 23, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jalao, I.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; De Ancos, B. Effect of high-pressure processing on flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, dihydrochalcones and antioxidant activity of apple ‘Golden Delicious’ from different geographical origin. Inn Food Sci and Emer Technol 2019, 51, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilla, A.; Rodrigo, M.J.; De Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; Zacarías, L.; Alegría, A.; Barberá, R. Impact of high-pressure processing on the stability and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds of Clementine mandarin juice and its cytoprotective effect in Caco-2 cells. Food Funct 2020, 11, 8951–8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ancos, B.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; Zacarías, L. Effect of high-pressure processing applied as pretreatment on carotenoids, flavonoids and vitamin C in juice of the sweet oranges ‘Navel’ and the red-fleshed ‘Cara Cara’. Food Res Internat 2020, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R. N.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Roobab, U.; Munir, M. A.; Naderipour, A.; Qureshi, M. I.; El-Din Bekhit, A.; Liu, Z. W.; Aadil, R. M. Pulsed electric field: A potential alternative towards a sustainable food processing. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 11, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houška, M.; Silva, F.V.M.; Evelyn; Buckow, R. ; Terefe, N.S.; Tonello, C. High pressure processing applications in plant foods. Foods 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Li, R.; Song, X.; Clausen, M.P.; Orlien, V.; Giacalone, D. The effect of high-pressure processing on sensory quality and consumer acceptability of fruit juices and smoothies: A review. Food Res Intern 2022, 157, 111250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-de la Peña, M.; Rábago-Panduro, L.M.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Welti-Chanes, J. Pulsed Electric Fields Technology for Healthy Food Products. Food Engin Rev 2021, 13, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Plaza, L.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, P. Effect of combined treatments of high-pressure and natural additives on carotenoid extractability and antioxidant capacity of tomato puree (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.). Eur Food Res Technol 2004, 219, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Mariutii, L.R.B.; Bragagnolo, N.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Barbosa-Canovas, G.V.; Orlien, V. Bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds from fruits and vegetables after thermal and nonthermal processing. Trends Food Sci. Tech 2017, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Agustí, A.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Elez-Martínez, P. Food processing strategies to enhance phenolic compounds bioaccessibility and bioavailability in plant-based foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 58, 2531–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gámez, G.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Pulsed electric field treatment strategies to increase bioaccessibility of phenolic and carotenoid compounds in oil-added carrot purées. Food Chemistry 2021, 364, 130377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Gil-Martìnez, E.; Blanco, I.; Rojas-Hidalgo, E. Reference values for retinol, alpha-tocopherol and main carotenoids in serum of control and insulin-dependent diabetic Spanish subjects. Clin Chem 1997, 43, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, H. Carotenoid interactions. Nutr Re. 1999, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Illingworth, D.R.; Connor, S.L.; Duell, P.B.; Connor, W.E. Competitive inhibition of carotenoid transport and tissue concentrations by high dose supplements of lutein, zeaxanthin and beta-carotene. Eur J Nutr 2010, 49, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.G.; Borge, G.I.A.; Kljak, K.; Mandić, A.I.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Pintea, A.M.; Ravasco, F.; Šaponjac, V.T.; Sereikaitė, J.; et al. European database of carotenoid levels in foods. Factors affecting carotenoid content. Foods 2021, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Mandić, A.I.; Bantis, F.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G.I.A.; Brnčić, M.; Bysted, A.; Cano, M.P.; Dias, M.G.; Elgersma, A.; et al. A comprehensive review on carotenoids in foods and feeds: status quo, applications, patents, and research needs. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 8, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, F.; Olmedilla, B.; Blanco, I.; Rojas-Hidalgo, E. Carotenoid composition in raw and cooked spanish vegetables. J Agric Food Chem 1992, 40, 2135–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, G. B.; Boluda-Aguilar, M.; Taboada-Rodríguez, A.; Soto-Jover, S.; Marín-Iniesta, F.; López-Gómez, A. Processing, packaging, and storage of tomato products: Influence on the lycopene content. Food Engineering Reviews 2015, 8, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Changes of health-related compounds throughout cold storage of tomato juice stabilized by thermal or high intensity pulsed electric field treatments. Innovative Food Sci Emerging Technol 2008, 9, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Hernández-Jover, T.; Martín-Belloso, O. Carotenoid and phenolic profile of tomato juices processed by high intensity pulsed electric fields compared with conventional thermal treatments. Food Chem 2009, 112, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, P.; Cano, M. P.; De Ancos, B.; Plaza, L.; Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Martín, A. Intake of Mediterranean soup treated by pulsed electric fields affects plasma vitamin C and antioxidant biomarkers in humans. Int J Food Sci Nut. 2005, 56, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, L.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; De Ancos, B.; Cano, P. Carotenoid content and antioxidant capacity of Mediterranean vegetable soup (gazpacho) treated by high-pressure/temperature during refrigerated storage. Eur Food Res Technol 2006, 223, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Vendrell-Pacheco, M.; Heskitt, B.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Failla, M.; Sastry, S.K.; Francis, D.M.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Kopec, R.E. Novel Processing Technologies as Compared to Thermal Treatment on the Bioaccessibility and Caco-2 Cell Uptake of Carotenoids from Tomato and Kale-Based Juices. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 10185–10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Casado, S.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Application of pulsed electric fields to tomato fruit for enhancing the bioaccessibility of carotenoids in derived products. Food Funct 2018, 9, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayathunge, K.G.L.R.; Stratakos, A.C.; Cregenzán-Albertia, O.; Grant, I.R.; Lyng, J.; Koidis, A. Enhancing the lycopene in vitro bioaccessibility of tomato juice synergistically applying thermal and non-thermal processing technologies. Food Chem 2017, 221, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, V.; Lietz, G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Phelan, D.; Reboul, E.; Bánati, D.; Borel, P.; Corte-Real, J.; de Lera, A.R.; Desmarchelier, C.; et al. From carotenoid intake to carotenoid blood and tissue concentrations—Implications for dietary intake recommendations. Nutr Rev 2021, 79, 544–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla, B.; Granado, F.; Southon, S.; Wright, A.J.A.; Blanco, I Gil-Martínez, E. ; Van Den Berg, H.; Thurnham, D.; Corridan, B.; Chopra, M.; Hininger, I. A European multicentre, placebo-controlled supplementation study with a-tocopherol, carotene-rich palm oil, lutein or lycopene: analysis of serum responses. Clin Sci 2002, 102, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboul, E. Absorption of vitamin A and carotenoids by the enterocyte: focus on transport proteins. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3563–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, T.W.; Boileau, A.C.; Erdman, J.W.Jr. Bioavailability of all-trans and cis-isomers of lycopene. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002, 227, 914–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Concepción, M.; Ávalos, F.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Limón, C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog Lipid Res 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.; Sies, H. Uptake of lycopene and its geometrical isomers is greater from heat-processed than from unprocessed tomato juice in humans. J Nutr 1992, 122, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstone, J.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Riedl, K.M.; Haufe, T.C.; Schweiggert, R.M.; King, S.A.; Timmers, C.D.; Francis, D.M.; Lesinski, G.B.; Clinton, S.K.; Schwartz, S.J. Enhanced bioavailability of lycopene when consumed as cis-isomers from tangerine compared to red tomato juice, a randomized, cross-over clinical trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015, 59, 658–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livny, O.; Reifen, R.; Levy, I.; Madar, Z.; Faulks, R.; Southon, S.; Schwartz, B. Beta-carotene bioavailability from differently processed carrot meals in human ileostomy volunteers. Eur J Nutr 2003, 42, 338–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J.; Qin, J.; Krinsky, N.I.; Russell, R.M. Nutrient Requirements and Interactions Ingestion by Men of a Combined Dose of b-Carotene and Lycopene Does Not Affect the Absorption of b-Carotene but Improves That of Lycopene. J Nutr 1997, 127, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, D.; White, W.S.; Olson, J.A. Intestinal absorption, serum clearance, and interactions between lutin and beta-carotene when administered to human adults in separate or combined oral doses. Am J Clin Nutr 1995, 62, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, H. ; van Vliet,T. Effect of simultaneous, single oral doses of beta-carotne with lutein or lycopene on the beta-carotene and retinyl ester responses in the triacylglycerol-rich lipoprotein fraction of men. Am J Clin Nutr 1998, 68, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micozzi, M.S.; Brown, E.D.; Edwards, B.K.; Bieri, J.G.; Taylor, P.R.; Khachik, F.; Beecher, G.R.; Smith, J.C.Jr. . Plasma carotenoid response to chronic intake of selected foods and beta-carotene supplements in men. Am J Clin Nutr, 1992; 55, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar]

| Type of gazpacho* | Concentrations in gazpacho (µg/100 dL) | Concentrations supplied (µg/day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene (total) | Trans-lycopene | Cis-isomer lycopene (1 and 2 peaks) | β-carotene (total) | Cis-β-carotene | Lycopene | β-carotene | % trans-lycopene | % trans-β-carotene | |

| Gazpacho-LP | 2176.6 | 1678.6 | 183.4 / 302.6 | 360.3 | 108.1 | 10883 | 1802 | 77.12 | 70.05 |

| Gazpacho-FP | 825.4 | 687.7 | 70.0 /66.8 | 209.9 | 17.4 | 4127 | 1050 | 83.32 | 91.7 |

| Gazpacho-HPP | 1263.2 | 991.4 | 141.9 /130.0 | 206.9 | 32.6 | 6316 | 1035 | 78.48 | 84.24 |

| Gazpacho-PEF | 1671.7 | 1306.7 | 128.2 / 236.8 | 186.0 | 32.9 | 8359 | 930 | 78.17 | 82.31 |

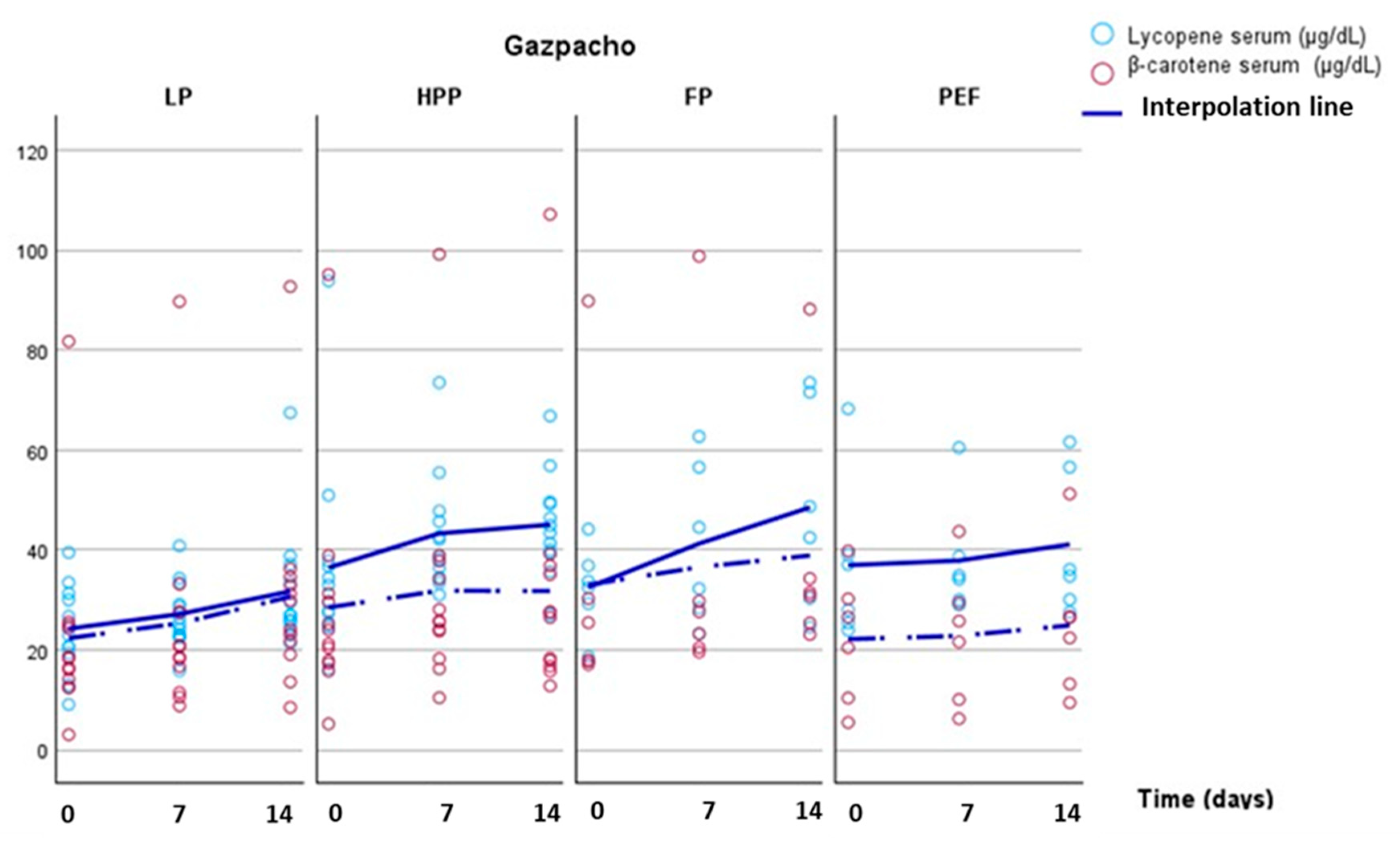

| Gazpacho-LP (n=12) | Gazpacho-FP (n=6) | Gazpacho-HPP (n=12) |

Gazpacho-PEF (n=6) |

Gazpacho (LP, HPP, FP, PEF) (n=36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene - basal | 24.2 ± 2.5 A [23.6] | 32.5 ± 3.5 A [33.1] |

36.4 ± 5.8 [31.3] |

36.9 ± 6.8 [32.5] | 31.8 ± 2.5 A [29.5] |

| Lycopene – 7 d | 27.1 ± 1.9 a B [26.8] | 41.3 ± 6.5 b B [38.4] | 43.3 ± 3.4 b [40.5] |

37.9 ± 4.8 [34.5] | 36.7 ± 2.1 B [34.2] |

| Lycopene – 14 d | 31.7 ± 3.6 a C[26.9] | 48.5 ± 8.4 b B [45.6] | 45.0 ± 2.9 b [44.2] |

41.1 ± 5.9 [35.4] |

40.5 ± 2.5 B[38.0] |

| ß-carotene - basal | 22.3 ± 5.7 [17.4] |

33.0 ± 11.6 [21.7] |

28.5 ± 6.5 [22.6] |

22.1 ± 5.2 [23.5] |

26.1 ± 3.5 X[20.4] |

| ß-carotene – 7 d | 25.3 ± 6.2 [19.6] |

36.5 ± 12.6 [25.4] |

31.8 ± 6.6 [25.7] |

22.8 ± 5.6 [23.7] |

28.9 ± 3.7 [23.9] |

| ß-carotene – 14 d | 30.6 ± 6.2 [26.9] |

38.9 ± 10.0 [31.2] |

31.8 ± 7.3 [27.0 ] |

24.9 ± 6.0 [24.4] |

31.4 ± 3.6 Y[26.5] |

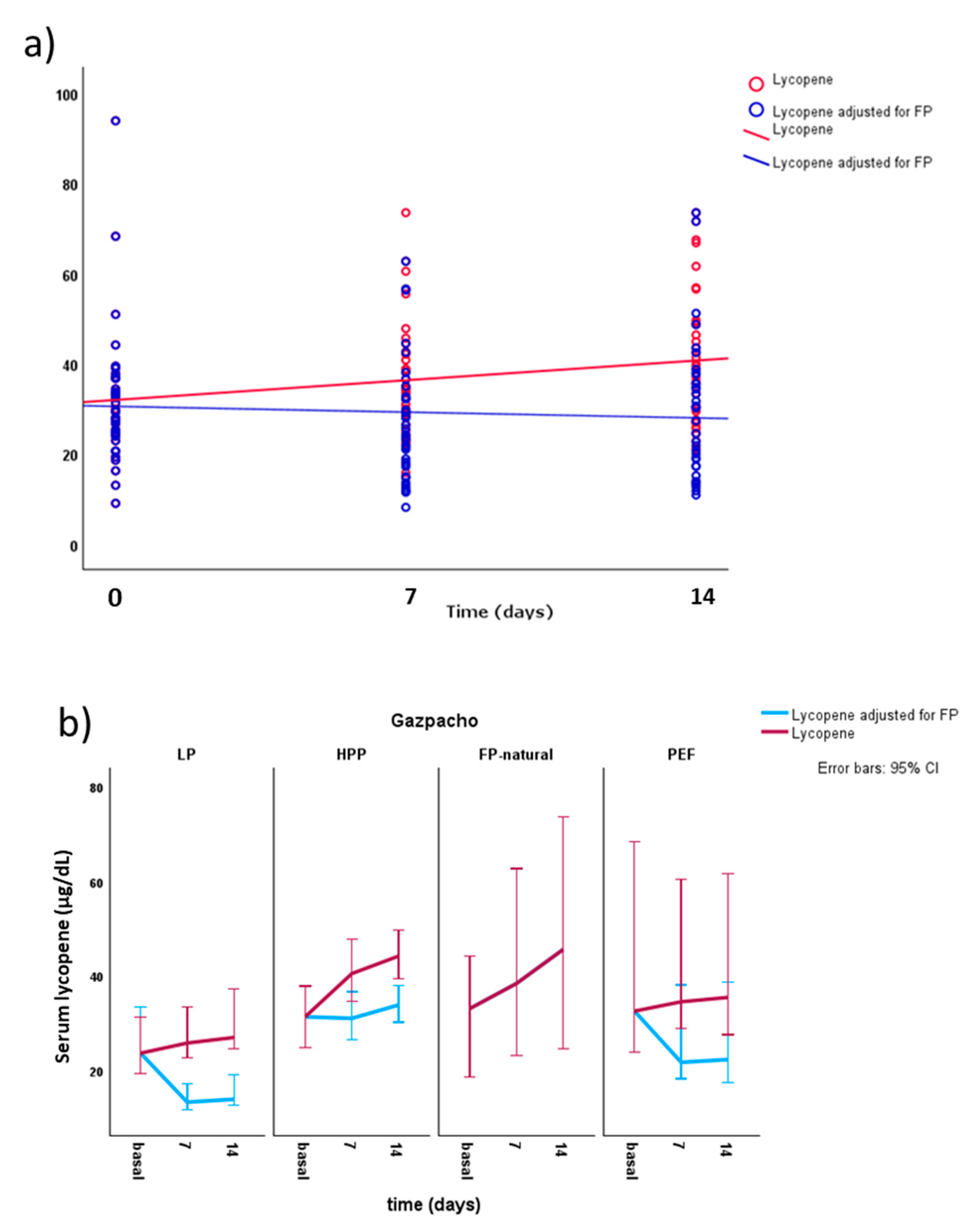

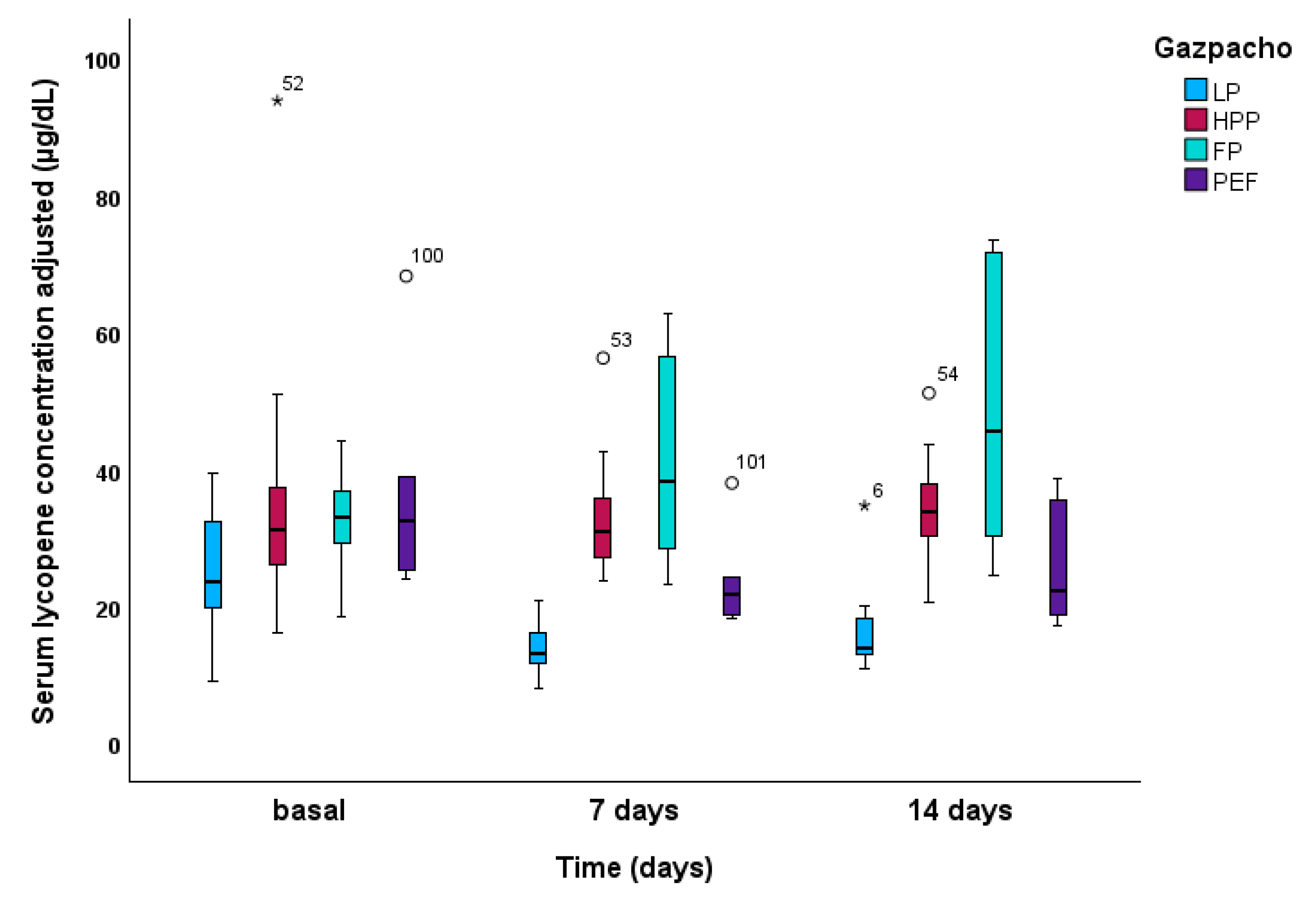

| Gazpacho-LP (n=12) |

Gazpacho-FP (n=6) | Gazpacho-HPP (n=12) | Gazpacho-PEF (n=6) |

Gazpacho (LP, HPP, FP, PEF) (n=36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene - basal | 24.5 ± 8.9 [23.6] A | 32.5 ± 8.5 [33.1] | 36.4 ± 20.0 [31.3] | 37.0 ± 16.5 A [32.5] | 31.9 ± 15.2 [29.5] |

| Lycopene – 7 d | 14.0 ± 3.4 Aa [13.3] |

41.3 ± 16.0 Ab [38.4] | 33.2 ± 9.0 b[31.0] | 23.8 ± 7. 3 B [21.7] | 26.6 ± 13.4 [24.1] |

| Lycopene – 14 d | 16.3 ± 6.4 Ba [13.9] |

48.5 ± 20.5 Bb [45.6] | 34.5 ± 7.8 b[33.8] | 25.8 ± 9.0 [22.3] | 29.3 ± 15.4 [28.8] |

| ß-carotene - basal | 22.3 ± 19.8 [17.4] | 33.0 ± 28.3 [21.7] | 28.5 ± 22.7 [22.6] | 22.1 ± 12.8 [23.5] | 26.1 ± 21.0 [20.4] |

| ß-carotene – 7 d | 19.4 ± 16.5 [15.1] | 36.5 ± 30.7 [25.4] | 31.7 ±22.8 [25.6] | 23.9 ± 14.3 [24.8] | 27.1 ± 21.4 [23.0] |

| ß-carotene – 14 d | 23.5 ± 16,4 [20.7] | 38.9 ±24.5 [31.2] | 31.7 ± 25.3 [26.9] | 26.0 ± 15.4 [25.6] | 29.2 ± 10.1 [25.3] |

| Lycopene | β-carotene | |

|---|---|---|

| Gazpacho-LP | 15.11 ± 0.87 (13.28 , 16.94) A | 21.69 ± 2.83 (15.95 , 27.44) |

| Gazpacho-HPP | 34.13 ± 1.59 (30.86 , 37.40) B | 30.55 ± 3.81 (22.82 , 38.28) |

| Gazpacho-FP | 36. 19 ± 3.04 (29.33 , 43.04) B | 36.40 ± 16.45 (23.45 , 49.35) |

| Gazpacho-PEF | 25.62 ± 2.16 (20.91 , 30.33) C | 23.77 ± 3.13 (17.16 , 30.39) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).