1. Introduction

Healthy calves are essential for a successful cattle production system, both in terms of animal welfare and economic outcomes [

1]. Poor calf health leads to immediate financial losses and long-term performance setbacks. Europe is a major global producer of beef and veal, with the European Union producing approximately 6.6 million tonnes in 2022, accounting for 15.6% of its total meat production [

2]. In Finland, beef production largely depends on raising bull calves that are either pure dairy breeds or crosses between dairy and beef breeds. About two-thirds of these calves, usually around 2 to 3 weeks old, are transported from multiple dairy farms first to specialized calf-rearing units. Later, at approximately six months of age, they are moved to specialized beef production farms. The other one-third are delivered directly from dairy farms to integrated beef production farms. This transportation practice of calves from multiple farms increases stress levels and infection risks [

3].

Calf mortality is multifactorial, resulting from a combination of factors such as infectious agents, maternal causes and substandard housing and management conditions, as well as commingling of calves from different sources [

4]. Among the most significant health challenges in calf rearing are respiratory infections [

5], with both upper and lower respiratory tract infections grouped under the umbrella term of bovine respiratory disease (BRD). BRD contributes to calf mortality, increased treatment costs, and long-term declines in animal performance [

6]. Studies consistently identify BRD as the primary reason for high treatment rates on calf rearing farms [

3,

7]. A recent study in Finland found that 67% of calves received at least one treatment with antibiotics and NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), with 66% of those cases involving antibiotics alone [

7].

Calves rely on passive immunity from dams as their primary defence against diseases. This immunity is transferred in the form of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies found in colostrum, along with leucocytes and immune-modulating factors such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase proteins (APP) [

8]. Inadequate transfer of passive immunity to the calves is a major risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality [

9]. At around three weeks of age, calves begin producing their own antibodies, marking the onset of active immune development [

10]. However, passive immunity presents both benefits and challenges for young calves: while it protects young calves from disease, it can also interfere with their ability to develop active immunity [

11]. During this vulnerable period, around the age of 3 weeks, stressors such as transportation, sorting, and extensive commingling further increase their susceptibility to disease.

As BRD contributes to calf morbidity and mortality, increased treatment costs (antibiotics and NSAID), and reduced performance, the early detection of respiratory disease through sensitive diagnostic tools could improve calf welfare, support healthy growth, and promote responsible antibiotic use. In calves, APP like haptoglobin (Hp), serum amyloid A (SAA), and albumin (Alb), are sensitive markers of systemic inflammation, secreted by the liver during the acute phase response [

12]. Previous studies have linked and shown usefulness of measuring APP in both naturally occurring and experimental respiratory infections [

13,

14,

15]. A study by Gånheim et al. [

16] reported that when calves were introduced into new farm environments, those originating from herds with a higher disease incidence had higher serum APP concentrations and lower weight gains than healthier herds. Similarly, the study by Orro et al. [

17] found that SAA was a sensitive marker of inflammation, even when clinical signs of respiratory disease were mild to moderate. Since APP reflect systemic inflammation [

15], disease severity [

17] and can help in evaluating overall calf health [

16], they may serve as valuable tools for assessing and monitoring disease, welfare, and general health status in calves from an early age.

Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate changes in serum concentrations of SAA, Hp, Alb, and IgG in calves with clinical signs of BRD, along with their seroconversion status for selected respiratory infections, longitudinally during the rearing period. The data used in this study were collected from calves during farm visits in Finland, as reported by Seppä-Lassila et al. [

3], the first publication from this trial. That study investigated the association between group size and calf health and growth. Here, another dataset from the same trial is used to explore the associations between calf health, passive immunity, management factors, and inflammatory response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

A randomized trial was conducted in a calf rearing unit in Western Finland from September 2013 to April 2014. Calves were transported to the rearing unit from dairy farms within a 200 km radius. A detailed description of the study design and sampling was provided by Seppä-Lassila et al. [

3]. That study reported the association between group size and calf health and growth whereas, the current study examined the associations between health, passive immunity, management factors, and inflammatory responses in rearing calves considering group size.

Briefly, the study was conducted in one calf rearing facility with 18 compartments housing a total of 1,440 calves. The calves (mean arrival age: 24.1 ± 9.2 days) were transported from surrounding farms and randomly assigned upon arrival to either a large group (40 calves per pen) or four small groups (10 calves per pen) upon arrival to the facility, using an alternating allocation method. Throughout the study, two specific all-in-all-out calf rearing compartments were consistently utilised, with 6 batches of approximately 80 calves each investigated for 50 days of the rearing period, warranting a balanced comparison between group sizes. On average, calves in the small groups came from 7.2 herds per batch (range: 5–9 herds), while those in the large groups originated from 23.8 herds per batch (range: 16–31 herds). The calf batches included breeds: Holstein-Friesian, Finnish Ayrshire, and dairy-beef breed mix. Sample size calculations are described by Seppä-Lassila et al. [

3]. Altogether, 476 calves were included in the study, consisting of 238 calves reared in large groups and 238 calves housed in small groups. All calves were housed in an insulated barn, with controlled ventilation, a slatted floor feeding area, a resting area with wood shaving bedding and standard space allocation per calf. Calves had free access to water and acidified milk replacer, consuming an average of 8–9 litres per day. Concentrates and silage were provided ad libitum and no intake was not recorded. It was assumed that all calves were managed according to current legislation on the source farms, which includes providing adequate colostrum, and feeding with milk or starter feed before transporting to the rearing facility. Further details on animal and farm characteristics are provided in

Table 1.

2.2. Clinical Assessment and Sample Collection

Upon arrival, or the following day, the calves underwent clinical assessment. The following clinical parameters were documented for all calves: rectal temperature (ºC), respiratory rate (breaths/min), presence of nasal and ocular discharge (yes/no), auscultation findings, navel or joint swelling, diarrhoea, and demeanour (depression). Farm workers conducted daily observations for clinical signs in the calves from the time of arrival through the 50-day study period. Following the clinical examination, blood samples were collected by veterinary personnel during the first 50 days of the rearing period: first time directly after arrival at the facility or the following day (first sampling time), and then at three week intervals (second and third sampling times). In total, 476 calves were included at the first sampling time. By the second (n = 471) and third sampling times (n = 469), the number of calves decreased due to mortality or missing data. All in all, 1416 blood samples were collected for laboratory analysis. Calves that showed clinical BRD signs during the 50-day observation period received antimicrobial treatment according to veterinarian’s guidelines. Farm workers administered antimicrobial treatment if calves met at least two of the following criteria for BRD: rectal temperature ≥39.8°C, visibly rapid breathing (>60 breaths/min), or signs of depression (lethargy, empty stomach, or lying down while others were active). To estimate infection pressure within the pen, the percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD at the time of each sampling times was calculated (

Table 1). BRD data used in the analyses were based on the diagnosis at the sampling times made by veterinarians.

The primary BRD treatment consisted of a single intramuscular dose of tulathromycin (Draxxin 100 mg/ml, 2.5 mg/kg) and a subcutaneous dose of meloxicam (Metacam 20 mg/ml, 0.5 mg/kg). If additional treatment was required in recurrent BRD cases, oxytetracycline (Terramycin/LA 200 mg/ml, 20 mg/kg) was administered intramuscularly three times every other day, with meloxicam repeated alongside each antibiotic administration. If a calf met only one of the specified clinical BRD criteria, a single subcutaneous dose of meloxicam (Metacam 20 mg/ml, 0.5 mg/kg) was administered. In cases where primary BRD treatment proves ineffective, benzyl penicillin (Ethacilin 300,000 IU/ml or Penovet 300,000 IU/ml, 20,000-30,000 IU/kg) was administered in combination with NSAID. During the study period, respiratory disease was the primary reason for antimicrobial treatment, accounting for 88.6% of all diseases diagnoses, followed by diarrhoea at 3.7%, lethargy at 3.5%, feet problems at 1.0%, colic at 0.8%, ear infections or drooping ears at 0.6%, umbilical diseases at 0.4%, fever at 0.2%, and undefined (1.2%). A total of 458 calves (96.2%) received antimicrobial treatment, while 18 calves (3.8%) remained untreated. The mean number of antimicrobial treatments per calf was 2.10 (SD ± 1.01). Calves treated with NSAID only were primarily showing signs of respiratory disease (93.3%) or lethargy (5.5%). The mean number of NSAID-only treatments per calf was 2.77 (SD ± 2.45; [

3]).

2.3. Sample Analysis

Blood samples were collected from the jugular veins of calves and were stored on the day of sampling in a Styrofoam box with cooling elements and transported overnight to the laboratory, protected from extreme temperatures. The following day, serum was separated by centrifugation, then frozen and stored in the freezer until analysis. Serum SAA concentration was measured using a commercial ELISA kit (Phase SAA kit, Tridelta Ltd., Ireland) following the manufacturer’s instructions for cattle. Initially, all samples were diluted 1:1,000, with a maximum standard curve concentration of 150 mg/l. Samples exceeding this concentration were further diluted and re-assayed. The detection limit of the kit was 0.3 mg/l.

Hp concentrations were measured using the haemoglobin assay method by Makimura and Suzuki [

18], modified to use tetramethylbenzidine (0.06 mg/ml) as the chromogen [

19]. Standard curves for the assay were generated by serial dilution of pooled, lyophilized bovine acute-phase serum. Calibration used a bovine sample with a known Hp concentration, provided by the European Commission Concerted Action Project (QLK5-CT-1999-0153).

Alb concentrations were determined with an automated chemistry analyser (KONE Pro, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland), and IgG levels were measured using a commercial ELISA kit (Bio-X Diagnostics, Rochefort, Belgium) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Virus specific antibodies were also detected in the blood samples collected at all three sampling times. Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis) antibodies were tested using the BIO K302 Monoscreen Ab ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics). Antibodies against bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (BPIV3), and bovine coronavirus (BCV) were tested using kits from SVANOVA Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). Seroconversion to these respiratory pathogens was defined as a two-fold rise in antibody levels, compared to the optical density value determined at the first sampling time. If a calf seroconverted during the study period, the same calf was considered seroconverted at all subsequent sampling times.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Linear mixed-effects regression models were used to study how clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size and other farm level factors were associated with APP and IgG concentrations in calves during the 50-day rearing period. Four mixed-effects linear regression repeated measure models were built, with SAA, Hp, Alb, and IgG concentrations as outcome variables. Also, IgG concentration measured at the first sampling (reflecting each calf’s passive transfer of maternal immunity) was included as a predictor in the APP models to account for variation in passive immunity among calves, and for its probable role in mitigating systemic inflammatory response.

To achieve normal distributions, SAA and Hp values were logarithmically transformed. Interaction with sampling time was used for all explanatory variables. Random effects accounted for variability at the batch and pen levels, as well as repeated sampling within the same calf using a first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances to account for temporal correlations. As the pen-level random effect was not significant, this level was excluded from all models, and two-level (batch and calf) nested hierarchical models were used instead.

Potential confounders were controlled in the models, including age at first sampling time, breed, group size (large group: 40 calves per pen; small group: 10 calves per pen), and sample haemolysis. As serum Hp measurements can be affected by haemolysis, the degree of haemolysis (no haemolysis, moderate haemolysis or severe haemolysis) was evaluated and included in the statistical model for Hp.

The explanatory variables included in the initial models were clinical BRD status at the sampling time, seroconversion to respiratory pathogens (M. bovis, BRSV, BPIV3, BCV), days since the last antimicrobial and NSAID treatments, percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD, IgG concentration measured at the first sampling time and presence of other clinical signs such as diarrhoea, umblical swelling and joint inflammation. Interaction terms with sample time with all predictor variables were included to the model.

A stepwise backward elimination was used to construct the final models, retaining only variables and interactions that were significant at any sampling time. The model results are presented according to each sampling time. Model fit and variance components were evaluated using the intra-class correlation coefficient for batch effects and the correlation between consecutive sampling times within calves. The likelihood ratio test was performed for each model to determine the significance of random effects.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC 14.2 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA), and results were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

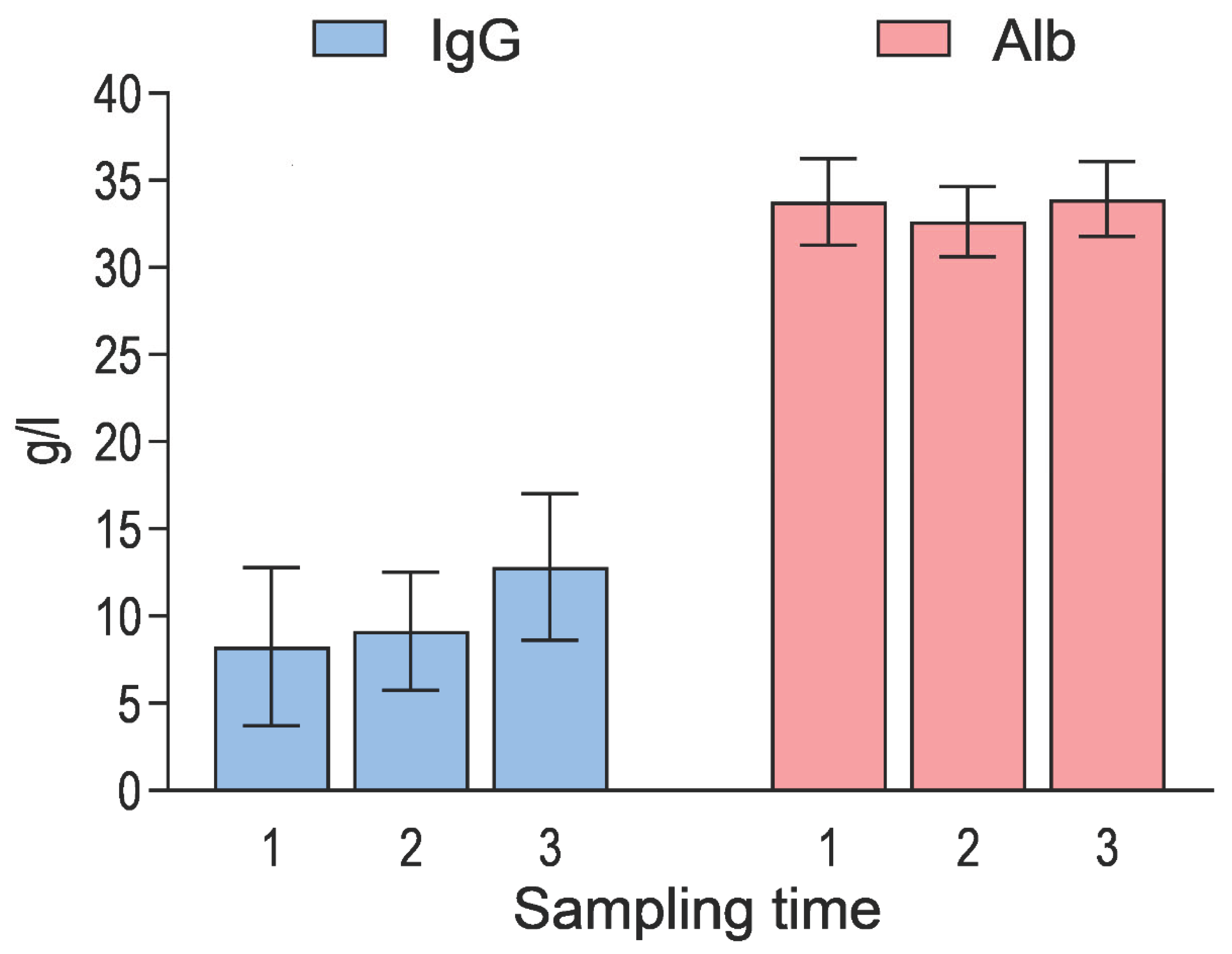

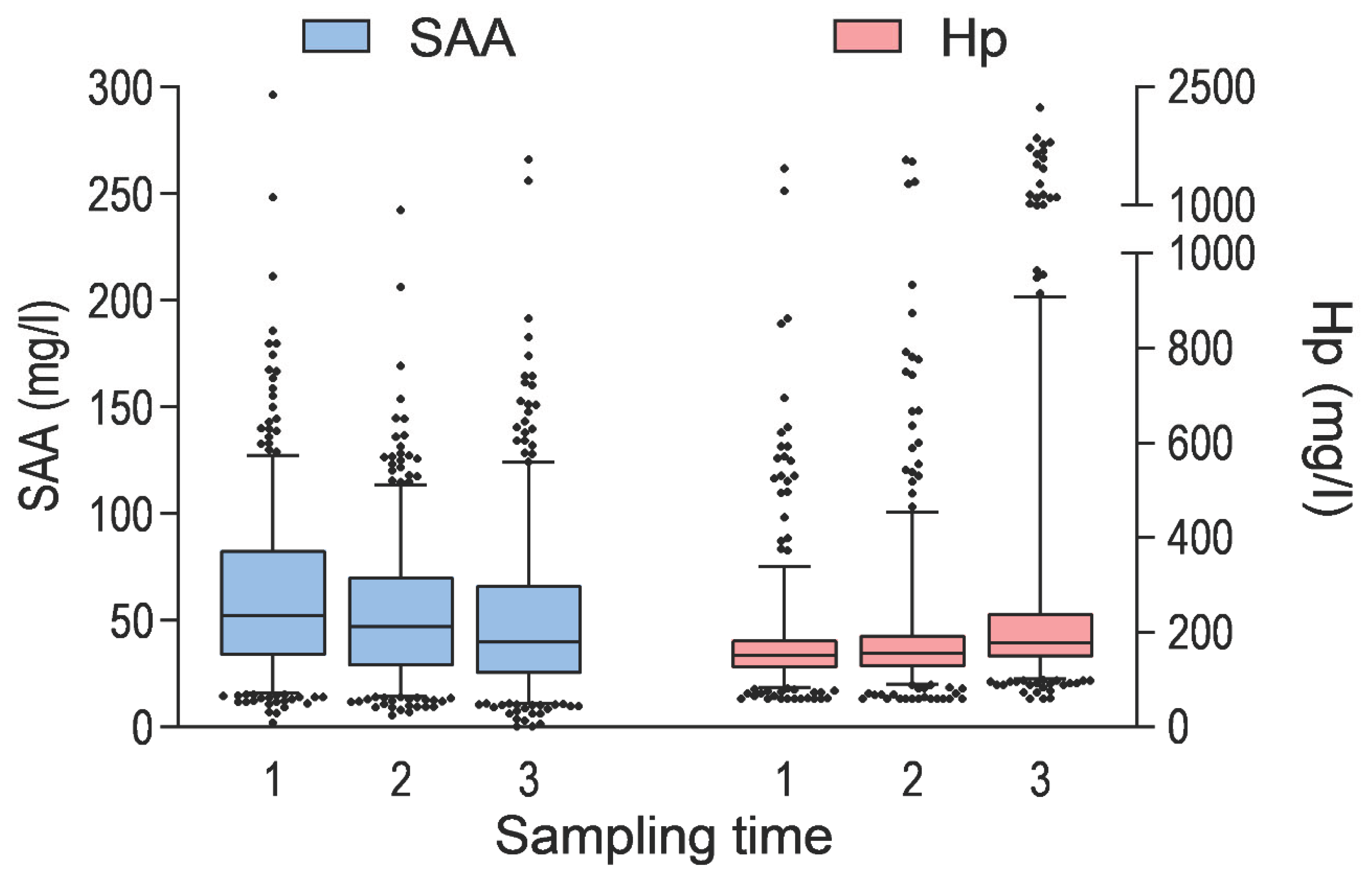

A total of 476 calves were included in the study, arriving at the rearing facility at an average age of 24.1 ± 9.2 days. At the first sampling time, the calves were 25.0 ± 10.2 days old. The majority were male (82.8%), and most of the calves belonged to Holstein-Friesian (45.8%) or Finnish Ayrshire (37.4%) breeds. Clinical signs of disease were present in a proportion of calves at the first sampling time: 5.0% had clinical BRD, 13.4% had diarrhoea, 11.3% showed umbilical swelling, and 0.4% had joint swelling. Descriptive characteristics of animal- and farm-level variables, as well as concentrations of SAA, Hp, Alb, and IgG are provided in

Table 1 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

3.1. APP Association with Clinical BRD

Based on multivariable analysis, calves with clinical BRD had significantly increased serum Hp concentrations at the second (p = 0.020) and third sampling time (p < 0.001;

Table 2). Additionally, calves with clinical BRD had increased serum SAA concentrations at the third sampling time (p < 0.001;

Table 3). At the first sampling time, a higher percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD was associated with lower serum Alb (p < 0.001;

Table 4) and increased serum Hp concentrations (p = 0.029;

Table 2) whereas at the third sampling time, pens with a higher percentage of calves with clinical BRD had significantly increased serum SAA concentration (p = 0.002;

Table 3).

3.2. APP and IgG Associations with Seroconversion to Respiratory Infections

Calves that seroconverted to BRSV had significantly lower serum Alb (p < 0.001;

Table 4) and lower serum IgG concentrations (p = 0.015;

Table 5) at the first sampling time. Additionally, BRSV seroconversion in calves was significantly associated with increased serum SAA concentrations at the second sampling time (p = 0.006;

Table 3). At the third sampling time,

M. bovis seroconversion was significantly associated with increased serum Hp concentration (p = 0.035;

Table 2). Seroconversion to BPIV3 and BCV in calves were also evaluated; however, no significant associations were found.

3.3. Effect of Group Size on APP Concentrations

Group size had a significant effect on serum APP concentrations only at the third sampling time. Calves housed in larger groups (40 calves per pen) had lower serum Hp (p = 0.033;

Table 2), serum SAA (p < 0.001;

Table 3) and serum Alb concentrations (p < 0.001;

Table 4) compared to those in smaller groups (10 calves per pen).

3.4. Associations Between APP and IgG Concentrations

Serum IgG at the first sampling time was positively associated with serum Hp (p = 0.046;

Table 2) and negatively associated with SAA (p = 0.047;

Table 3) and serum Alb concentrations (p < 0.001;

Table 4). The positive association between serum IgG measured at the first sampling time and serum Hp concentration was present also at the second sampling time (p = 0.017;

Table 2).

3.5. Breed and Treatment History Effect on APP and IgG Concentrations

Holstein calves had lower serum SAA concentrations compared to Finnish Ayrshire calves, with significant differences at both the first (p < 0.001) and second (p = 0.020;

Table 3) sampling times. Holstein calves also had significantly lower serum IgG concentrations than Finnish Ayrshire calves at the second (p = 0.021;

Table 5) and third (p = 0.004;

Table 5) sampling times, while mixed dairy-beef breed calves had lower serum IgG concentrations at the third sampling time compared to Finnish Ayrshire calves (p = 0.009;

Table 5).

Previous antibiotic and NSAID treatments were significantly associated with APP and IgG concentrations. Serum SAA concentration was negatively associated with the number of days since the last antibiotic treatment at the second (p = 0.009) and third sampling times (p = 0.009;

Table 3), whereas serum Alb and IgG concentrations were positively associated with days since the last antibiotic treatment at the second (p = 0.033;

Table 4) and third sampling times (p = 0.013;

Table 5), respectively. Moreover, days since the last NSAID treatment were positively associated with serum Alb concentration (p = 0.021;

Table 4) and negatively associated with serum IgG concentration at the third sampling time (p = 0.029;

Table 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical BRD and APP/IgG Responses

The use of APP as biomarkers in calves is important for understanding their immune status and ability to respond to infections during early life. APP serve as valuable indicators of inflammation, immune function, and overall health, which are essential factors for effective calf management [

14]. With this in mind, the present study investigated APP serum concentrations in relation to clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors at three sampling times, over a 50-day period post-arrival in a calf-rearing facility in Finland.

BRD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in calves, and Hp is frequently used as a marker of inflammation or infection, especially in respiratory diseases [

13,

14,

20]. The positive association found in this study between clinical BRD status and serum Hp concentration at the second and third sampling times, supports the established role of Hp in responding to respiratory infections. Similarly, the presence of clinical BRD was associated with increased serum SAA concentrations at the third sampling time, which aligns with the role of SAA as an APP that increases during respiratory infections [

15,

17,

20]. This result also suggests that at first sampling time, fewer clinical BRD calves might mean less systemic immune activation in calves. As more calves had developed BRD by the third sampling time, the inflammatory response became more evident, which might explain the delayed increase in APP response. A higher percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD was also associated with APP response, which is reflected in increased serum SAA and lower serum Alb concentrations, agreeing with their roles as positive and negative APP [

21,

22].

4.2. Associations Between Seroconversion to Respiratory Infections with APP

Calves that seroconverted for BRSV had significantly lower serum Alb concentrations at the first sampling time and increased serum SAA at the second sampling time. BRSV infections can elicit widespread inflammation, causing acute phase response and further decrease in serum Alb [

22] and increase in serum SAA concentrations as part of the inflammatory process [

17].

Moreover, the association between

M. bovis seroconversion and increased serum Hp concentration in calves at the third sampling time suggests that calves exposed to

M. bovis also have increased inflammatory responses. As a well-known pathogen associated with respiratory disease,

M. bovis exposure is linked to chronic inflammation, specifically if co-pathogens worsen disease outcomes in

M. bovis infected calves [

14,

23]. This also explains why there was a delayed increase in serum Hp: it is likely due to the subclinical nature of

M. bovis [

24,

25], which may not cause an acute phase response after exposure or may cause a response only in cases with co-infections.

We also found that serum IgG concentrations were significantly lower in calves that had seroconverted to BRSV at the first sampling time, suggesting that infections like BRSV may impair IgG production [

26]. Alternatively, it is also possible that calves with lower IgG were more vulnerable to earlier BRSV infection. Maternal antibodies play a protective role and can reduce the severity of clinical disease [

27], however, this observation can also be due to the presence of maternal antibodies in case of BRSV [

28], which delay the calf's immune response and hinder its ability to develop a strong defence. Overall, this highlights the complex but important role of IgG in immune protection and disease resilience in the face of common respiratory infections during the early calf rearing period.

4.3. Associations Between APP and IgG Concentrations at Calf Arrival

At the first and second sampling time, IgG showed a marginal positive association with Hp. Reasonably, calves with higher serum IgG should be less prone to infections and thus should have lower inflammation if Hp was only reflecting an acute-phase inflammatory response. However, Hp is not only an APP but also a scavenger of free haemoglobin. Hp binds free haemoglobin released during haemolysis and clears it, preventing oxidative damage [

29]. Calves with lower IgG are more prone to subclinical or low grade infections [

30] that may cause erythrocyte damage and haemolysis, leading to higher Hp utilisation in blood and consequently lower circulating serum Hp. This interpretation is supported by the findings of Seppä-Lassila et al. [

13], who reported that lower serum Hp concentrations were associated with mild signs of eimeriosis and suggested that this decrease was not directly related to the inflammatory process but rather reflected Hp’s role as a haemoglobin scavenger. In contrast, calves in the present study with higher serum IgG (better transfer of passive immunity) may have been less susceptible to low-grade infections, leading to higher measurable serum Hp concentrations. The persistence of this association at the second sampling time may represent a carry-over effect from calves with initially low IgG, which remained more prone to infections during rearing.

Higher serum IgG concentration was also associated with lower serum SAA at first sampling time, which suggests that calves with successful transfer of passive immunity are better protected against early inflammatory challenges, thus showing lower serum SAA concentrations. Increased serum IgG was associated with lower serum Alb at first sampling time. One possible explanation is that calves with lower serum IgG were more prone to inflammatory or infectious processes [

30], resulting in a compensatory increase in Alb synthesis whereas calves with higher serum IgG concentrations were better protected against inflammation and thus did not need to upregulate serum Alb synthesis. Another related explanation is that calves with higher serum IgG may have an overall different protein profile, as both immunoglobulin and APP production occurs in the liver. During early calf life under novel environment and infection pressure, the liver may prioritize maintaining a balanced protein profile, warranting proper concentrations of immunoglobulins and APP [

31].

4.4. Effect of Housing on Calf Serum APP Concentrations

At the third sampling time, calves in larger groups had lower serum SAA, Hp and Alb concentrations. This finding is intriguing, as it conflicts with the common understanding that housing calves in larger groups increases the risk of infection [

32], and consequently inflammatory response [

33], compared to smaller groups which may present a lower infection pressure. Svensson and Liberg [

32] found no significant differences in mean Hp concentrations between calves kept in the small-sized (6-9) versus the large-sized groups (12-18). One possible explanation to the findings of our study is that larger groups might buffer individual calves from stress through social interactions promoting positive psychological or social states, and neuroimmune regulation [

34,

35,

36]. Recent work in mice reported that activation of the brain’s reward system in ventral tegmental area (VTA), reduces certain systemic inflammatory signalling (lower interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta) and simultaneously support other inflammatory processes (liver-derived complement component 3 and helper T cells), for better recovery from injury [

36]. Thus, larger groups may provide calves with improved social interactions that may stimulate reward system activation through sympathetic nervous system, leading to a more adaptive immune profile. Whereas, calves in small groups may actually experience less social stimulation and reward signalling, leaving calves in a relatively pro-inflammatory state even under lower infection pressure. Consequently, the immune systems of calves from small pens may have been less prepared to cope with infection challenges.

4.5. Other Influential Factors Affecting APP and IgG Concentrations

In our study, serum SAA concentrations in calves varied between breeds: Holstein calves had lower serum SAA compared to Finnish Ayrshire calves, both at first and second sampling times, while mixed dairy-beef breed calves showed no significant difference compared to Finnish Ayrshire, suggesting breed-specific differences in immune response [

37]. This difference may be influenced by Holsteins’ genetic selection for high milk production, which may influence their immune responses differently compared to breeds like Finnish Ayrshire [

38]. Breed was also associated with serum IgG concentrations, with Holstein calves showing significantly lower serum IgG than Finnish Ayrshire calves at both the second and third sampling times and mixed dairy-beef breed calves only at third sampling time. This aligns with research suggesting that genetic differences affect immune resilience, with some breeds being more resistant to infections [

39]. Additionally, the Finnish Ayrshire breed is more common in traditional, smaller herds, whereas Holsteins are predominantly reared in larger, more intensive production systems. It is reported that larger herd size is a significant risk factor for inadequate colostrum management [

6].

The negative association between days since the last antibiotic treatment and serum SAA concentration suggests that antibiotics, by reducing infection and inflammation [

40], significantly lowers SAA serum concentration in calves. Moreover, the positive association between serum Alb concentration and days since the last antibiotic and NSAID treatment shows recovery from inflammation where the liver resume to normal albumin production [

41]. Together, these associations may suggest the potential use of APP to monitor treatment effectiveness. Days since last antibiotic treatments showed a significant positive relationship with serum IgG concentrations, indicating active IgG production during the recovery phase post-infection. Furthermore, a negative association between days since last NSAID treatment and serum IgG concentration was also observed, which may be due to NSAID anti-inflammatory effects that can suppress immune responses [

42,

43].

4.6. Limitations

The nature of the observational part of this study limits making causal inferences due to the potential for residual confounding from unmeasured pen-level factors such as ventilation efficacy, transport stress etc. Furthermore, while confounding effect of breed was controlled in models, it may still act as a proxy for underlying management and environmental differences, since calves originated from different herds. Another limitation is that while seroconversion indicates whether calves were exposed to respiratory pathogens and developed an immune response, we lack the information about the exact time of infection. As a result, some infection-related effects on APP responses may not have been fully accounted for in our analyses. Although the models controlled for several confounders, unmeasured factors at the pen or herd level could still influence the outcomes. Therefore, the findings must be interpreted in light of potential field-level variations, as some associations may be influenced by confounding factors or by interactions not captured in the models.

5. Conclusions

This study found that calves with clinical BRD and those that seroconverted to BRSV and M. bovis showed changes in serum APP concentration indicating an acute phase response to pathogen exposure. Additionally, calves housed in larger pens had lower serum Hp, SAA and Alb concentrations, highlighting the influence of management practices on calves’ probability of suffering from inflammation-related diseases. Calves with lower serum IgG concentration at arrival to the facility were more likely to seroconvert to BRSV, whereas higher serum IgG concentrations were associated with increased inflammatory marker levels, suggesting a complex role of IgG in immune protection and disease resilience during the early calf-rearing period. While more research is needed to assess APP feasibility for routine farm use our results reinforce their utility for monitoring calf health and welfare and impact of management in calf rearing systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O. and T.S.; methodology, R.K., L.S.-L., H.S., T.H., E.D.-S. and T.O; validation, R.K.; formal analysis, R.K., and T.O.; investigation, L.S.-L., H.S., T.H., V.T., J.O., U.R., E.D.-S. and T.O.; resources, L.S.-L., H.S., T.H. and T.O.; data curation, R.K. and T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, R.K. and T.O.; supervision, L.S.-L., T.H., K.M., T.S., H.S. and T.O.; project administration, L.S.-L., H.S. and T.O.; funding acquisition, T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The analysis of the samples was partly funded by the Mercedes Zachariassen foundation and by the Estonian Research Council project IUT8-1. The study was also partly co-funded by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development as KESTO project (Kestävä karjatalous – Sustainable Livestock Production).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data and blood samples used in this study were collected from calves during farm visits at a calf rearing unit, conducted from September 2013 to April 2014 in Finland. These visits, including the sampling of calves, were part of routine work within the development project for contract farm producers (slaughterhouses’ development project) or herd health investigations. According to the legislation in force at the time, this was not considered an experimental study, and therefore ethical approval for an animal experiment was not required. However, all ethical procedures were strictly followed, and blood sample collection was carried out by veterinary personnel with minimal restraint and stress to the calves.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly thank the personnel and the owner of the calf rearing unit for participating in the study, as well as our colleague Dr. Marina Erm for helping with grammatical corrections in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

During the study, Tuomas Herva was working as a veterinarian of Atria Ltd, to which the calves were finally sold and slaughtered. This did not affect aims or performance of the study or interpreting the results. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Canali, E.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Schmidt Gortazar, C.; Herskin, M.; Michel, V.; Chueca Miranda, M.A.; Padalino, B.; Pasquali, P.; Roberts, C.H.; Spoolder, H.; Stahl, K.; Velarde, A.; Viltrop, A.; Jensen, M.B.; Waiblinger, S.; Candiani, D.; Lima, E.; Mosbach-Schulz, O.; Van der Stede, Y.; Vitali, M.; Winckler, C. Welfare of calves. EFSA J. 2023, 21, 07896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agricultural production - livestock and meat, October 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=427096 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Seppä-Lassila, L.; Oksanen, J.; Herva, T.; Dorbek-Kolin, E.; Kosunen, H.; Parviainen, L.; Soveri, T.; Orro, T. Associations between group sizes, serum protein levels, calf morbidity and growth in dairy-beef calves in a Finnish calf rearing unit. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 161, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsein, M.; Lindberg, A.; Hallén, S.C.; Persson, W.K.; Törnquist, M.; Svensson, C. Risk factors for calf mortality in large Swedish dairy herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 99, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Nagamine, B.; Ducatez, M.F. Understanding the mechanisms of viral and bacterial coinfections in bovine respiratory disease: a comprehensive literature review of experimental evidence. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, I.; Earley, B.; Gilmore, J.; Hogan, I.; Kennedy, E.; More, S.J. Calf health from birth to weaning. III. Housing and management of calf pneumonia. Ir. Vet. J. 2011, 64, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelin, A.; Hälli, O.; Härtel, H.; Herva, T.; Kaartinen, L.; Tuunainen, E.; Rautala, H.; Soveri, T.; Simojoki, H. Effect of farm management practices on morbidity and antibiotic usage on calf rearing farms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetsalu, K.; Niine, T.; Loch, M.; Dorbek-Kolin, E.; Tummeleht, L.; Orro, T. Effect of colostrum on the acute-phase response in neonatal dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6207–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, D.; Francoz, J.; Berman, S.; Dufour, S.; Buczinski, S. Association between transfer of passive immunity and health disorders in multisource commingled dairy calves raised for veal or other purposes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8371–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertz, A.F.; Hill, T.M.; Quigley, J.D. III; Heinrichs, A.J.; Linn, J.G.; Drackley, J.K. A 100-year review: Calf nutrition and management. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10151–10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeel, I.; Antonis, A.F.G.; Fluess, M. Efficacy of a modified live intranasal bovine respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in 3-week-old calves experimentally challenged with BRSV. Vet. J. 2007, 174, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersall, P.D.; Bell, R. Acute phase proteins: Biomarkers of infection and inflammation in veterinary medicine. Vet. J. 2010, 185, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppä-Lassila, L.; Orro, T.; Lassen, B.; Lasonen, R.; Autio, T.; Pelkonen, S.; Soveri, T. Intestinal pathogens, diarrhoea and acute phase proteins in naturally infected dairy calves. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 41, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ider, M.; Maden, M. Biomarkers of infectious pneumonia in naturally infected calves. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 83, ajvr.21.10.0172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaura, R.; Dorbek-Kolin, E.; Loch, M.; Viidu, D.A.; Orro, T.; Mõtus, K. Association of clinical respiratory disease signs and lower respiratory tract bacterial pathogens with systemic inflammatory response in preweaning dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5988–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gånheim, C.; Alenius, S.; Persson Waller, K. Acute phase proteins as indicators of calf herd health. Vet. J. 2007, 173, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orro, T.; Pohjanvirta, T.; Rikula, U.; Huovilainen, A.; Alasuutari, S.; Sihvonen, L.; Pelkonen, S.; Soveri, T. Acute phase protein changes in calves during an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makimura, S.; Suzuki, N. Quantitative determination of bovine serum haptoglobin and its elevation in some inflammatory diseases. Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 1982, 44, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsemgeest, S.P.M.; Kalsbeek, H.C.; Wensing, T.; Koeman, J.P.; Van Ederen, A.M.; Gruys, E. Concentrations of serum amyloid-A (SAA) and haptoglobin (HP) as parameters of inflammatory diseases in cattle. Vet. Q. 1994, 16, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikunen, S.; Härtel, H.; Orro, T.; Neuvonen, E.; Tanskanen, R.; Kivelä, S.L.; Sankari, S.; Aho, P.; Pyörälä, S.; Saloniemi, H.; Soveri, T. Association of bovine respiratory disease with clinical status and acute phase proteins in calves. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 30, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orro, T. Acute phase proteins in dairy calves and reindeer changes after birth and in respiratory infections. PhD Thesis, University of Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, H.H.; Nielsen, J.P.; Heegaard, P.M.H. Application of acute phase protein measurements in veterinary clinical chemistry. Vet. Res. 2004, 35, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulikh, K.; Burrows, D.; Perez-Casal, J.; Tabatabaei, S.; Caswell, J.L. Effects of inflammatory stimuli on the development of Mycoplasma bovis pneumonia in experimentally challenged calves. Vet. Microbiol. 2024, 297, 110203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caswell, J.L.; Archambault, M. Mycoplasma bovis pneumonia in cattle. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2007, 8, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, M.; Lamont, E.A.; Janagama, H.K.; Widdel, A.; Vulchanova, L.; Stabel, J.R.; Waters, W.R.; Palmer, M.V.; Sreevatsan, S. Biomarker discovery in subclinical mycobacterial infections of cattle. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.; Petrie, L.; Konoby, C.; Haines, D.M.; Cortese, V.; Ellis, J.A. The efficacy of modified-live bovine respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in experimentally infected calves. Vaccine 1999, 18, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, G.; Foret-Lucas, C.; Delverdier, M.; Cuquemelle, A.; Secula, A.; Cassard, H. Protection against bovine respiratory syncytial virus afforded by maternal antibodies from cows immunized with an inactivated vaccine. Vaccines 2023, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Fulton, R.W.; Burge, L.J.; DuBois, W.R.; Payton, M. Passively transferred immunity in newborn calves, rate of antibody decay, and effect on subsequent vaccination with modified live virus vaccine. Bovine Pract. 2001, 35, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, D.J.; Buehler, P.W. Cell-free hemoglobin and its scavenger proteins: new disease models leading the way to targeted therapies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a013433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtala, A.M.; Gröhn, Y.T.; Mechor, G.D.; Erb, H.N. The effect of maternally derived immunoglobulin G on the risk of respiratory disease in heifers during the first 3 months of life. Prev. Vet. Med. 1999, 39, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immler, M.; Büttner, K.; Gärtner, T.; Wehrend, A.; Donat, K. Maternal impact on serum immunoglobulin and total protein concentration in dairy calves. Animals 2022, 12, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, C.; Liberg, P. The effect of group size on health and growth rate of Swedish dairy calves housed in pens with automatic milk-feeders. Prev. Vet. Med. 2006, 73, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, M.E.; Boerman, J.P. Graduate student literature review: Social and feeding behavior of group-housed dairy calves in automated milk feeding systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 4833–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhao, X.-W.; Su, H.; Wang, Z.-P.; Wang, C.; Li, J.-H.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.-X.; Bao, J. Effects of group size on the behaviour, heart rate, immunity, and growth of Holstein dairy calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 241, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.-w.; Miao, E.-y.; Wang, Z.-p.; Xu, Y.; Bai, X.-j.; Bao, J. Effect of group size and regrouping on physiological stress and behavior of dairy calves. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, H.; Avishai, E.; Krot, M.; Ghiringhelli, M.; Reshef, M.; Abboud, Y.; Melamed, S.; Merom, S.; Boshnak, N.; Azulay-Debby, H.; Ziv, T.; Gepstein, L.; Rolls, A. Reward system activation improves recovery from acute myocardial infarction. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, M.A. Immune responses of Holstein and Jersey calves during the preweaning and immediate postweaning periods when fed varying planes of milk replacer. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 7319–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronzo, V.; Lopreiato, V.; Riva, F.; Amadori, M.; Curone, G.; Addis, M.F.; Cremonesi, P.; Moroni, P.; Trevisi, E.; Castiglioni, B. The role of innate immune response and microbiome in resilience of dairy cattle to disease: The mastitis model. Animals 2020, 10, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowder, G.D.; Van Vleck, L.D.; Cundiff, L.V.; Bennett, G.L. Influence of breed, heterozygosity, and disease incidence on estimates of variance components of respiratory disease in preweaned beef calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buret, A.G. Immuno-modulation and anti-inflammatory benefits of antibiotics: The example of tilmicosin. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2010, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S.H. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in animals. In MSD Vet. Manual; MSD: Kenilworth, NJ, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/pharmacology/inflammation/nonsteroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-in-animals (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Bancos, S.; Bernard, M.P.; Topham, D.J.; Phipps, R.P. Ibuprofen and other widely used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit antibody production in human cells. Cell. Immunol. 2009, 258, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y. Immunomodulatory effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at the clinically available doses. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2007, 30, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mean (±SD) serum concentrations of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and albumin (Alb) in calves by sampling time (n = 476, n = 471 and n = 469 respectively).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SD) serum concentrations of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and albumin (Alb) in calves by sampling time (n = 476, n = 471 and n = 469 respectively).

Figure 2.

Serum concentrations of serum amyloid A (SAA) and haptoglobin (Hp) in calves by sampling time (n = 476, n = 471 and n = 469 respectively). In this box-and-whisker chart, the box represents the interquartile range and median of the data. The whiskers represent the 5-95% of the data.

Figure 2.

Serum concentrations of serum amyloid A (SAA) and haptoglobin (Hp) in calves by sampling time (n = 476, n = 471 and n = 469 respectively). In this box-and-whisker chart, the box represents the interquartile range and median of the data. The whiskers represent the 5-95% of the data.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of animal- and farm-level variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of animal- and farm-level variables.

| Variable |

mean (±SD) / n (%) |

| Age for calves at arrival (days) |

24.1 ± 9.2 |

|

| Sex: |

|

| Male |

394 (82.8%) |

| Female |

82 (17.2%) |

| Breed: |

|

| Finnish Ayrshire |

178 (37.4%) |

| Holstein Friesian |

218 (45.8%) |

| Mixed dairy-beef breed 80 (16.8%) |

| Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) and treatment |

First sampling time (n = 476) |

Second sampling time (n = 471) |

Third sampling time (n = 469) |

| Number of pens with ≥1 calf with clinical BRD |

30 |

30 |

30 |

| Mean % of calves per pen with clinical BRD |

4.8% |

11.2% |

8.6% |

Calves with clinical BRD

(n, % ) |

24 (5.0%) |

45 (9.6%) |

50 (10.7%) |

Median days since last antimicrobial treatment

(min-max) |

0 (0-1) |

8 (1-22) |

16 (1-43) |

Median days since last NSAID5 treatment

(min-max) |

0 (0-1) |

11 (1-22) |

20 (1-43) |

| Other recorded clinical signs |

| Diarrhoea (n, %) |

64 (13.4%) |

108 (23.0%) |

25 (5.3%) |

| Umbilical swelling (n, %) |

54 (11.3%) |

24 (5.1%) |

27 (5.8%) |

| Swelling of joints (n, %) |

3 (0.4%) |

1 (0.2%) |

4 (0.9%) |

| Positive seroconversion status1 to respiratory pathogens |

|

Mycoplasa bovis (n, %) |

8 (1.7%) |

7 (1.5%) |

8 (1.7%) |

| BRSV2 (n, %) |

134 (28.6%) |

133 (28.2%) |

132 (28.1%) |

| BCV3 (n, %) |

106 (22.3%) |

104 (22.1%) |

104 (22.2%) |

| BPIV34 (n, %) |

79 (16.6%) |

76 (16.1%) |

75 (16.0%) |

Table 2.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of haptoglobin (Hp) concentration (log (mg/l)) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

Table 2.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of haptoglobin (Hp) concentration (log (mg/l)) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

| Variable |

n |

Coeff. |

SE |

p-value |

Wald test

p-value |

| At first sampling time |

| IgG1 at first sampling (g/l) |

476 |

0.010 |

0.005 |

0.046 |

|

| Percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD2

|

476 |

0.009 |

0.004 |

0.029 |

|

| Intercept |

|

0.069 |

9.039 |

0.994 |

|

| At second sampling time |

| IgG1 at first sampling (g/l) |

471 |

0.012 |

0.005 |

0.017 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.063 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

176 |

|

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

215 |

-0.109 |

0.052 |

0.037 |

|

| Mixed3

|

80 |

-0.129 |

0.069 |

0.067 |

|

| Clinical BRD2: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

426 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

45 |

0.191 |

0.082 |

0.020 |

|

|

M. bovis4 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

464 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

7 |

-0.330 |

0.193 |

0.087 |

|

| Intercept |

|

5.087 |

0.084 |

<0.001 |

|

| At third sampling time |

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.079 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

175 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

214 |

-0.096 |

0.052 |

0.066 |

|

| Mixed3

|

80 |

-0.134 |

0.069 |

0.054 |

|

| Clinical BRD2: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

419 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

50 |

0.632 |

0.079 |

<0.001 |

|

| Group size: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Small (10 calves per pen) |

236 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Large (40 calves per pen) |

233 |

-0.115 |

0.054 |

0.033 |

|

| Days since last antibiotic treatment |

469 |

-0.003 |

0.002 |

0.098 |

|

|

M. bovis4 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

461 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

8 |

0.383 |

0.182 |

0.035 |

|

| Intercept |

|

5.512 |

0.081 |

<0.001 |

|

Table 3.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of serum amyloid A (SAA) concentration (log (mg/l)) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

Table 3.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of serum amyloid A (SAA) concentration (log (mg/l)) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

| Variable |

n |

Coeff. |

SE |

p-value |

Wald test

p-value |

| At first sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

476 |

-0.052 |

0.012 |

<0.001 |

|

| Age at first sampling time squared (day) |

476 |

0.0005 |

0.0002 |

0.009 |

|

| IgG1 at first sampling time (g/l) |

476 |

-0.014 |

0.007 |

0.047 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

178 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Holstein- Friesian |

218 |

-0.268 |

0.067 |

<0.001 |

|

| Mixed2

|

80 |

-0.049 |

0.089 |

0.577 |

|

| Intercept |

|

5.105 |

0.196 |

<0.001 |

|

| At second sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

471 |

-0.009 |

0.004 |

0.010 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.061 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

176 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

215 |

-0.157 |

0.067 |

0.020 |

|

| Mixed2

|

80 |

-0.045 |

0.090 |

0.617 |

|

| Days since last antibiotic treatment |

471 |

-0.007 |

0.003 |

0.009 |

|

| BRSV3 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

338 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

133 |

0.197 |

0.071 |

0.006 |

|

| Intercept |

|

3.924 |

0.142 |

<0.001 |

|

| At third sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

469 |

-0.013 |

0.003 |

<0.001 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.052 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

175 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

214 |

-0.154 |

0.067 |

0.023 |

|

| Mixed1

|

80 |

-0.153 |

0.089 |

0.088 |

|

| Group size: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Small (10 calves per pen) |

236 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Large (40 calves per pen) |

233 |

-0.312 |

0.070 |

<0.001 |

|

| Clinical BRD4: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

419 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

50 |

0.366 |

0.102 |

<0.001 |

|

| Days since last antibiotic treatment |

469 |

-0.007 |

0.003 |

0.009 |

|

| Percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD4

|

469 |

0.013 |

0.004 |

0.002 |

|

|

M. bovis5 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

461 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

8 |

0.418 |

0.236 |

0.076 |

|

| Intercept |

|

4.171 |

0.119 |

<0.001 |

|

Table 4.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of albumin (Alb) concentration (g/l) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

Table 4.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of albumin (Alb) concentration (g/l) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), and at the end (n = 469). The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

| Variables |

n |

Coeff. |

SE |

p-value |

| At first sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

476 |

0.218 |

0.039 |

<0.001 |

| Age at first sampling time squared (day) |

476 |

-0.003 |

0.001 |

<0.001 |

| IgG1 at first sampling time (g/l) |

476 |

-0.078 |

0.022 |

<0.001 |

| Percentage of calves per pen with clinical BRD2

|

476 |

-0.096 |

0.015 |

<0.001 |

| BRSV3 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

| No |

342 |

0 |

|

|

| Yes |

134 |

-1.159 |

0.224 |

<0.001 |

| Intercept |

|

31.666 |

0.641 |

<0.001 |

| At second sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

471 |

0.036 |

0.011 |

0.001 |

| Days since last antibiotic treatment |

471 |

0.027 |

0.013 |

0.033 |

| Intercept |

|

31.169 |

0.439 |

<0.001 |

| At third sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

469 |

0.044 |

0.011 |

<0.001 |

| Days since last NSAID4 treatment |

469 |

0.009 |

0.003 |

0.021 |

| Group size: |

|

|

|

|

| Small (10 calves per pen) |

236 |

0 |

|

|

| Large (40 calves per pen) |

233 |

-1.119 |

0.26 |

<0.001 |

| Intercept |

|

32.82 |

0.418 |

<0.001 |

Table 5.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of immunoglobulin gamma (IgG) concentration (g/l) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), at the end (n = 469) of 50 days rearing period. The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

Table 5.

Results of multivariable linear mixed-effects regression model analysing the association of immunoglobulin gamma (IgG) concentration (g/l) with clinical respiratory disease, seroconversion to respiratory infections, group size, and other farm-level factors in calves during the 50-day rearing period by sampling time: at the beginning (n = 476), in the middle (n = 471), at the end (n = 469) of 50 days rearing period. The batch (n = 6) and sample time of the calf with first-order autoregressive structure with homogenous variances (AR1) were included as random factors.

| Variables |

n |

Coeff. |

SE |

p-value |

Wald test

p-value |

| At first sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

476 |

0.141 |

0.02 |

<0.001 |

|

| BRSV1 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

342 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

134 |

-1.054 |

0.431 |

0.015 |

|

|

M. bovis2 seroconversion: |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

468 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Yes |

8 |

-2.389 |

1.416 |

0.092 |

|

| Intercept |

|

5.549 |

0.693 |

<0.001 |

|

| At second sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

471 |

0.139 |

0.02 |

<0.001 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.043 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

215 |

0 |

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

176 |

-0.925 |

0.402 |

0.021 |

|

| Mixed3

|

80 |

-0.062 |

0.537 |

0.939 |

|

| Intercept |

|

6.931 |

0.741 |

<0.001 |

|

| At third sampling time |

| Age at first sampling time (day) |

469 |

0.099 |

0.020 |

<0.001 |

|

| Breed: |

|

|

|

|

0.005 |

| Finnish Ayrshire |

214 |

|

|

|

|

| Holstein Friesian |

175 |

-1.164 |

0.403 |

0.004 |

|

| Mixed3

|

80 |

-1.406 |

0.541 |

0.009 |

|

| Days since last antibiotic treatment |

469 |

0.033 |

0.013 |

0.013 |

|

| Days since last NSAID4 treatment |

469 |

-0.013 |

0.006 |

0.029 |

|

| Intercept |

|

10.728 |

0.730 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).