Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

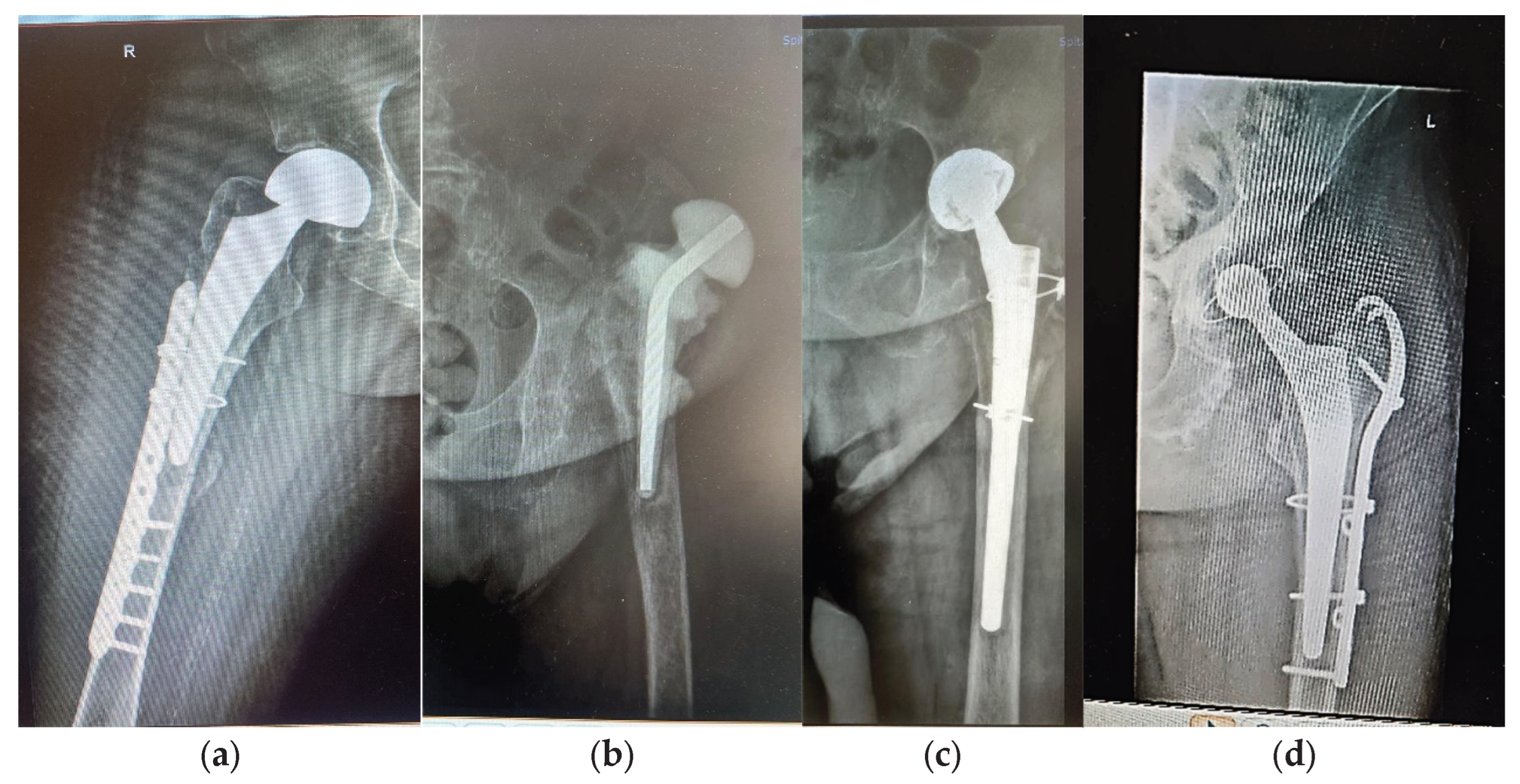

2.1. Three Case Report

| Case No. | Sex | Age [Years] | HA/Cause |

Type of Prosthesis | Underlying Conditions | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Revision Time [Years] | ||||||

| 1 -F1 | F | Over 35 | Yes; basicervical femoral neck fracture; unspecified fall; hemiarthroplasty; periprosthetic fracture |

- |

Bipolar, Zimmer Biomet Ti6Al4V stem and cable fixation |

Type 1 diabetes; renal failure end stage; essential hypertension | Insulin dependency, Dialysis dependency |

| 2 – F2 | F | Over 80 | Yes; 15; periprosthetic fracture; unspecified fall | Taper lock complete, Zimmer Biomet Ti6Al4V stem |

High blood pressure (AHT); Dyslipidaemia; hyperglycaemia; azotaemia; uraemia hypothyroidism | - | |

| 3 - M | M | Over 65 | Yes; 7; periprosthetic fracture; unspecified fall | Taper lock complete, Zimmer Biomet, Ti6Al4V stem |

AHT third degree, Congestive heart failure, old myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease (CAD), atrioventricular block (AV) first degree, right bundle branch block (RBBB), dyslipidaemia (mixt hyperlipidaemia), azotaemia, uraemia |

fractured stem left in place 6 months till revision; bone fragment with thin metal layer; periprosthetic tissue with cellulitis, panniculitis, myositis | |

2.2. Disorders in General Functions of the Body and Bone Health

2.3. Bone-Titanium Alloy Interaction-Study on Retrieved Prostheses, Ex Vivo Direct Bone Samples, and Simulated Body Fluids

2.3.1. Stems in Synthetic Plasma

| Compound | NaCl | CaCl2 | KCl | MgSO4 | NaHCO3 | Na2HPO4 | NaH2PO4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass [g] | 6.80267 | 0.20370 | 0.40099 | 0.10153 | 2.20212 | 0.12780 | 0.02644 |

2.3.2. Tissue in Synthetic Plasma

2.3.3. Surface Morphology and Element Analysis

2.3.4. Histopathological Analyses of Soft Tissue Remnant on Stem1

3. Results

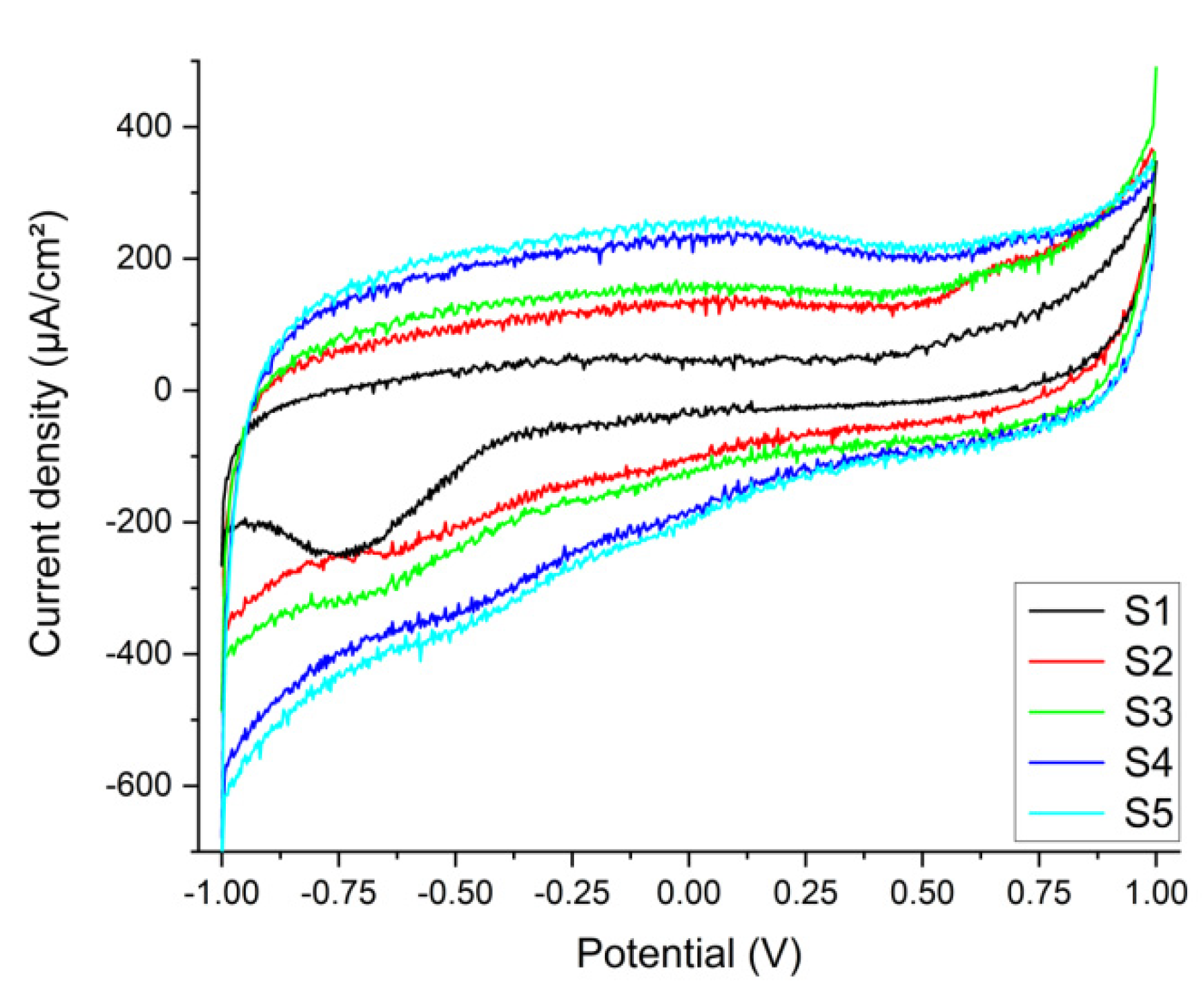

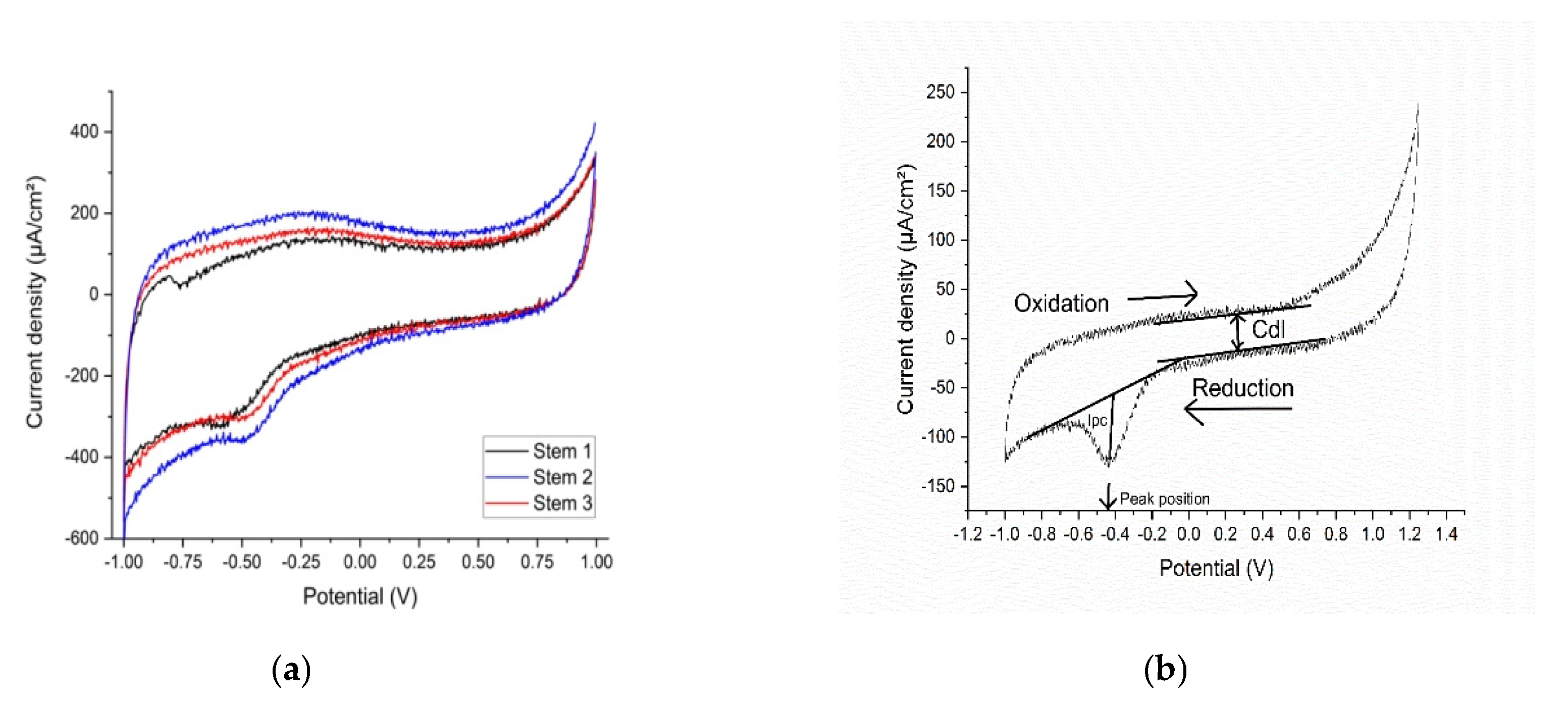

Electrochemistry

3.1.1. Stems in Synthetic Plasma

3.1.2. Tissue in Synthetic Plasma

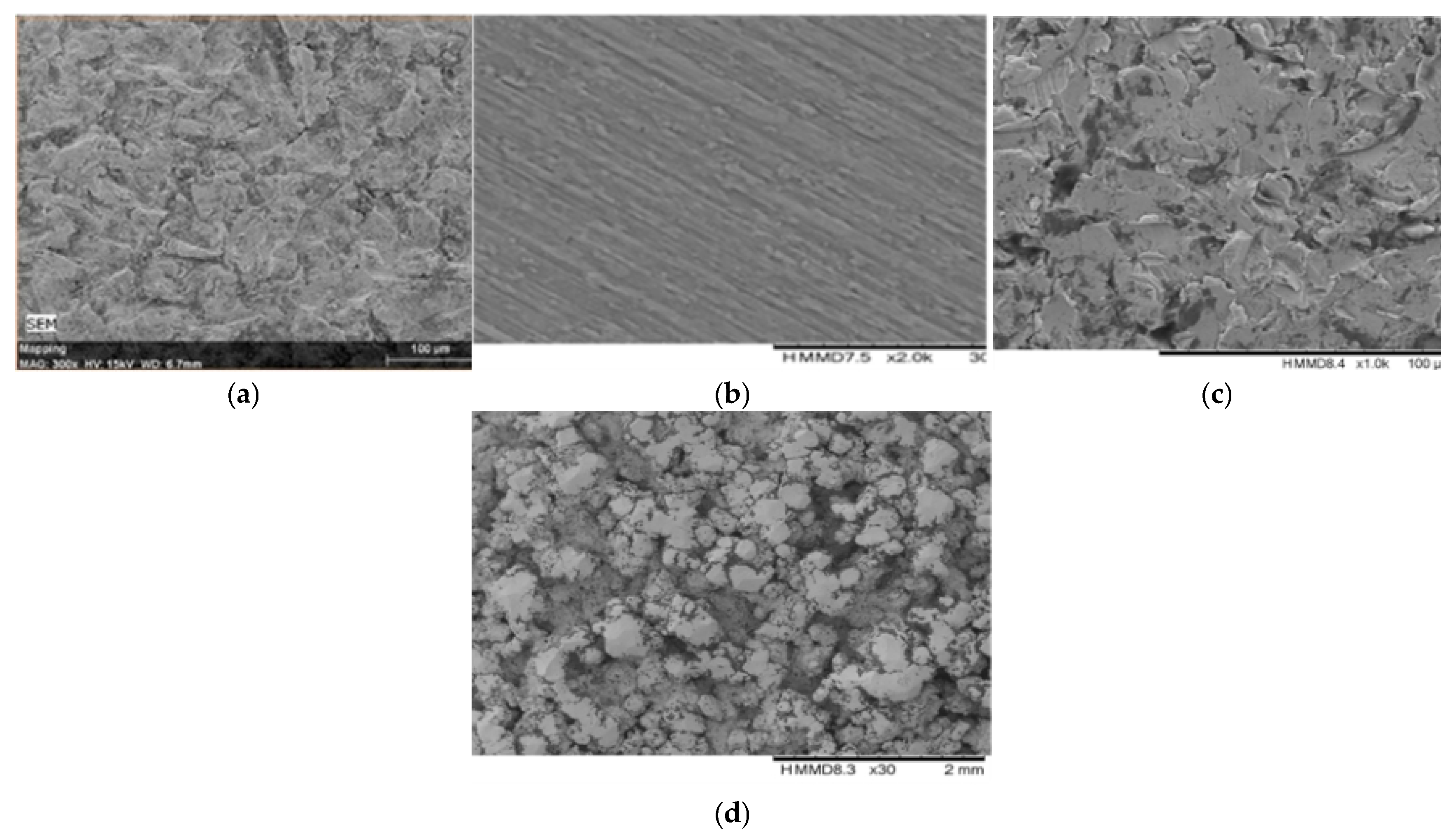

3.1.3. Surface Morphology and Element Analysis

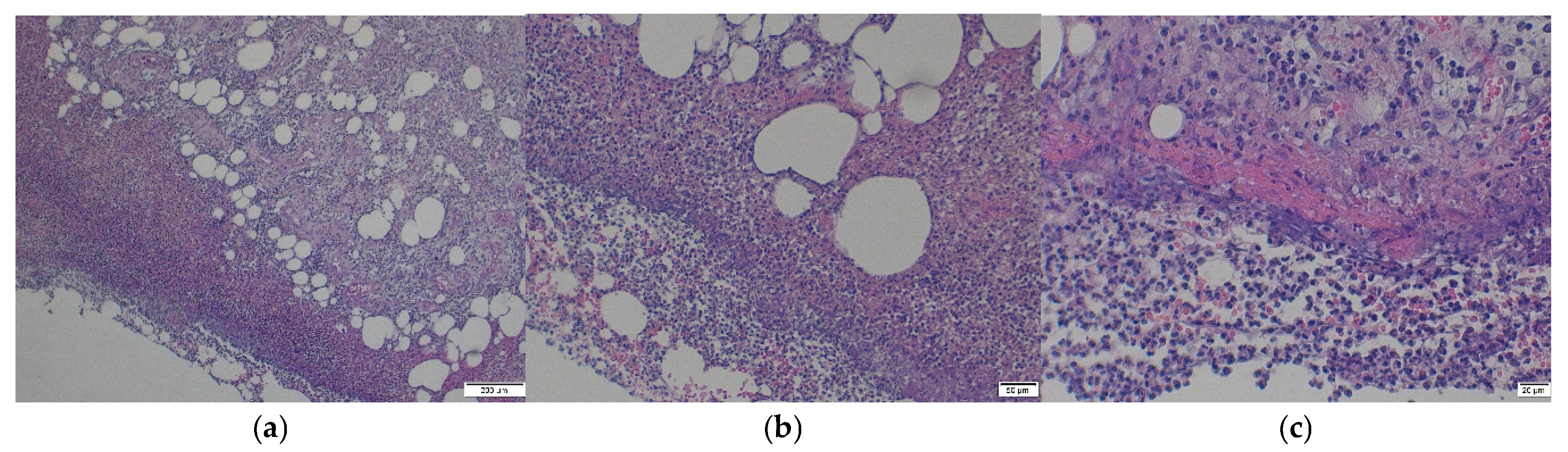

3.1.4. Histopathological Analyses of Soft Tissue Remnant on Stem1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. J. DeRogatis, E. Wintermeyer, T R. Sperring, P. S. Issack, Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, New York – Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, JBJS Am. 2019;101:745-54 d. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaur, K. Singh, Review on titanium and titanium - based alloys as biomaterials for orthopaedic applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019, Vol.102, pp. 844–862. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Abdel, U. Cottino, D.R. Larson, A.D. Hanssen, D.G. Lewallen, D.J. Berry, Modular fluted tapered stems in aseptic revision total hip arthroplasty. J BJS Am., 2017 May 17;99(10):873-81. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Cross, W. G. Paprosky, Managing femoral bone loss in revision total hip replacement: fluted tapered modular stems, Bone Joint J 2013 ;95-B, Supple A:95–7. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Brown, M. Tetreault, C. A. Cipriano, C. J. Della Valle, W. Paprosky, S. Sporer, Modular Tapered Implants for Severe Femoral Bone Loss in THA: Reliable Osseointegration but Frequent Complications, Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015, 473:555–560. [CrossRef]

- D. Apostu, O. Lucaciu, C. Berce, D. Lucaciu, D. Cosma, Current methods of preventing aseptic loosening and improving osseointegration of titanium implants in cementless total hip arthroplasty: a review, J Int Med Res 2017, Nov 3;46(6):2104–2119. ,. [CrossRef]

- B. Ziaie, X. Velay, W. Saleem, Advanced porous hip implants: A comprehensive review, Heliyon, 2024, 10 :18, e37818. [CrossRef]

- K. Solou, A. Vasiliki Solou, I. Tatani, J. Lakoumentas, K. Tserpes, P. Megas, A Customized Distribution of the Coefficient of Friction of the Porous Coating in the Short Femoral Stem Reduces Stress Shielding, Prosthesis 2024, 6, 1310–1324. [CrossRef]

- P. Hameeda, V. Gopala, S. Bjorklund, A. Ganvir, D. Sen, N. Markocsan, G. Manivasagam, Axial Suspension Plasma Spraying: An ultimate technique to tailor Ti6Al4V surface with HAp for orthopaedic applications, Colloids Surf.B: Biointerfaces, 2018, 173 806-815. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Baciu, Energy, Waves, and Forces in Bilateral Fracture of the Femoral Necks: Two Case Presentations and Updated Critical Review, Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2592. [CrossRef]

- E. Onochie, B. Kayani, S. Dawson-Bowling, S. Millington, P. Achan, S. Hanna, Total hip arthroplasty in patients with chronic liver disease: A systematic review, SICOT-J 2019, 4;5:40. [CrossRef]

- S.-M. Lee, W. C. Shin, S. H. Woo, T. W. Kim, D. H. Kim, K. T. Suh, Hip arthroplasty for patients with chronic renal failure on dialysis, Sci. Rep. 2023 13:3311. [CrossRef]

- P. Anagnostis, M. Florentin, S. Livadas, I. Lambrinoudaki, D. G. Goulis, Bone Health in Patients with Dyslipidemias: An Underestimated Aspect, Int. J. Mol.Sci. 2022, 23, 1639. [CrossRef]

- A. Arteaga, J. Qu, S. Haynes, B. G. Webb, J. LaFontaine, D. C. Rodrigues, Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Orthopedic Implant Surface Performance: A Retrieval and In Vitro Study, Bio Tribocorros. 2021; 7(2). [CrossRef]

- N. R. Rundora, J. W. Van der Merwe, D. E. P. Klenam, M. O. Bodunrin, Enhanced corrosion performance of low-cost titanium alloys in a simulated diabetic environment, Mater.Corros. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Si, M. Li, H. Liu, X. Jiang, H. Yu, D. Sun, Evaluation of tribocorrosion performance of Ti6Al4V alloy in simulated inflammatory and hyperglycemic microenvironments, Wear 2023, Volumes 532–533, 205077. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhong, X. Pan, Y. Chen, Q. Lian, J. Gao, Y. Xu, J. Wang, Z. Shi, H. Cheng, Prosthetic Metals: Release, Metabolism and Toxicity, Int J Nanomedicine 2024; 19:5245-5267. [CrossRef]

- N. Eliaz, Corrosion of Metallic Biomaterials: A Review, Materials 2019 12(3), 407. [CrossRef]

- D.C. Rodrigues, R.M. Urban, J. J. Jacobs, J. L Gilbert, In vivo severe corrosion and hydrogen embrittlement of retrieved modular body titanium alloy hip-implants, J.Biomed. Mat. Res. Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2009 88(1), 206-219. [CrossRef]

- J.-I. Yoo, Y. Cha, J. Kwak, H.-Y. Kim, W.-S. Choy, Review on Basicervical Femoral Neck Fracture:.

- Definition, Treatments, and Failures, Hip Pelvis 2020 32(4): 170-181. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Maceroli, R. S. Yoon, F.A. Liporace, Use of Antibiotic Plates and Spacers for Fracture in the Setting of Periprosthetic Infection, J Orthop Trauma 2019; 33 Suppl 6:S21-S24. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Petis, M. P. Abdel, K. I. Perry, et al., Long-term results of a 2-stage exchange protocol for periprosthetic joint infection following total hip arthroplasty in 164 hips, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019; 101:74–84. [CrossRef]

- N. Panahi, A. Soltani, A. Ghasem-Zadeh, G. Shafiee, R. Heshmat, F. Razi, N. Mehrdad, I. Nabipour, B. Larijani, A. Ostovar, Associations between the lipid profile and the lumbar spine bone mineral density and trabecular bone score in elderly Iranian individuals participating in the Bushehr Elderly Health Program: A population-based study, Arch. Osteoporos. 2019, 14, 52. [CrossRef]

- K.Y. Chin, C.Y. Chan, S. Subramaniam, N. Muhammad, A. Fairus, P.Y. Ng, N.A. Jamil, N.A. Aziz, S. Ima-Nirwana, N. Mohamed, Positive association between metabolic syndrome and bone mineral density among Malaysians, Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 2585–2593. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, Q. Wang, C. Lu, Y. Xu, H. Cao, X. Xie, X. Wu, J. Li, D. Chen, Association Between Bone Mineral Density and Lipid Profile in Chinese Women, Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1649–1664. [CrossRef]

- V. N. Shah, K. K. Harrall, C. S. Shah, T. L. Gallo, P. Joshee, J. K. Snell-Bergeon & W. M. Kohrt, Bone mineral density at femoral neck and lumbar spine in adults with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Osteoporos Int 2017 28, 2601–2610. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, Z. Fu, X. Wang , P. Zhou, Q. Yang, Y. Jiang, D. Zhu, A narrative review of diabetic bone disease: Characteristics, pathogenesis, and treatment, Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022; 13:1052592. [CrossRef]

- R. Chermiti, S. Burtey, L. Dou, Role of Uremic Toxins in Vascular Inflammation Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med, 2024, 13 (23), pp.7149. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Kattah, S. M. Titan, R. A. Wermers, The Challenge of Fractures in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease, Endocr. Pract.2025, 31:4, 511-520. [CrossRef]

- A. Pimentel, P. Ureña-Torres, J. Bover, J. L. Fernandez-Martín, M. Cohen-Solal, Bone Fragility Fractures in CKD Patients. Calcif Tissue Int. 2021, 108(4):539-550. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, E. Lee, M.-J. Lee, B. Park, I. Park, Characteristics of fracture in patients who firstly starts kidney replacement therapy in Korea: a retrospective population-based study, Sci Rep 2022, 12 3107. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Ureña Torres, M. Cohen-Solal, Evaluation of fracture risk in chronic kidney disease, J Nephrol. 2017 30(5):653-661. [CrossRef]

- L. Benea, N. Simionescu-Bogatu, Reactivity and Corrosion Behaviors of Ti6Al4V Alloy Implant Biomaterial under Metabolic Perturbation Conditions in Physiological Solutions, Materials 2021; 14(23):7404. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Gittens, R. Olivares-Navarrete, R. Tannenbaum, B.D. Boyan, Z. Schwartz, Electrical Implications of Corrosion for Osseointegration of Titanium Implants, J Dent Res. 2011; 90(12):1389-97. [CrossRef]

- D. Prando, A. Brenna, M. V. Diamanti, S. Beretta, F. Bolzoni, M. Ormellese, and M.P. Pedeferri, Corrosion of Titanium: Part 1: Aggressive Environments and Main Forms of Degradation, J. Appl. Biomater. Functional Mater 2017, 15, 4, e291-e302. [CrossRef]

- J. van Drunen, B. Zhao, G. Jerkiewicz, Corrosion behavior of surface-modified titanium in a simulated body fluid, J Mater Sci. 2011, 46:5931–5939. [CrossRef]

- M. Prestat, D. Thierry, Corrosion of titanium under simulated inflammation conditions: clinical context and in vitro investigations, Acta Biomater 2021, 136, 72-87. [CrossRef]

- M. Darwish Elsayed, Biomechanical Factors That Influence the Bone-Implant-Interface, Res Rep Oral Maxillofsc Surg 2017, 3:023. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Naghavi, H. Wang, S.N. Varma, M. Tamaddon, A. Marghoub, R. Galbraith, J. Galbraith, M. Moazen, J. Hua, W. Xu, C. Liu, On the morphological deviation in additive manufacturing of porous Ti6Al4V scaffold: a design consideration, Materials 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- N. Kohli, J. C. Stoddart, R. J. van Arkel, The limit of tolerable micromotion for implant osseointegration: a systematic review, Sci Rep 11, 2021 10797. [CrossRef]

- P. Kazimierczak, A. Przekora, Osteoconductive and Osteoinductive Surface Modifications of Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration: A Concise Review Coatings 2020, 10(10), 971. [CrossRef]

- W. Zuo, L. Yu, J. Lin, Y. Yang, Q. Fei, Properties improvement of titanium alloys scaffolds in bone tissue engineering: a literature review, Ann Transl Med. 2021, 9(15):1259. [CrossRef]

- V. Vasudha Nelluri, R. Kumar Gedela, M. Roseme Kandathilparambil, Influence of Surface Modification on Corrosion Behavior of the Implant Grade Titanium Alloy Ti-6Al-4V, in Simulated Body Fluid: An In Vitro Study. Int J Prosthodont Restor Dent 2020; 10(3):102–111. [CrossRef]

- T. Umamathi, R. Parimalam, V. Prathipa, A. Josephine Vanitha, K. Muneeswari, B. Mahalakshmi1, S. Rajendran, A. Nilavan, Influence of urea and glucose on corrosion resistance of Gold 21K alloy in the presence of artificial sweat, Zas Mat 2022 63:3, 341 – 352. [CrossRef]

- A. Ait Sidimou, D. M. El Marrakchia, E. Khoumri, Electrochemical corrosion behavior of a-titanium alloys in simulated biological environments (comparative study), RSC Adv., 2024, 14, 38110,. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Bard, R. Parsons, J. and Jordan, Standard Potentials in Aqueous Solution-1st Edition. IUPAC-Marcel Dekker Inc., New York ISBN 9780824772918, Published August 27, 1985 by CRC Press.

- S.A. H. Naghavi, S. N. Wang, M. Varma, A. Tamaddon, R. Marghoub, J. Galbraith, M. Galbraith, J. Moazen, J. Hua, W. Xu, C. Liu, On the morphological deviation in additive manufacturing of porous Ti6Al4V scaffold: a design consideration, Materials 2022, 15(14), 4729. [CrossRef]

- Alireza Rahimnia, Hamid Hesarikia, Amirhosein Rahimi, Shahryar Karami, and Kamran Kaviani, Evaluation and comparison of synthesised hydroxyapatite in bone regeneration: As an in vivo study, J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2021 Jul 15;16(6):878-886. [CrossRef]

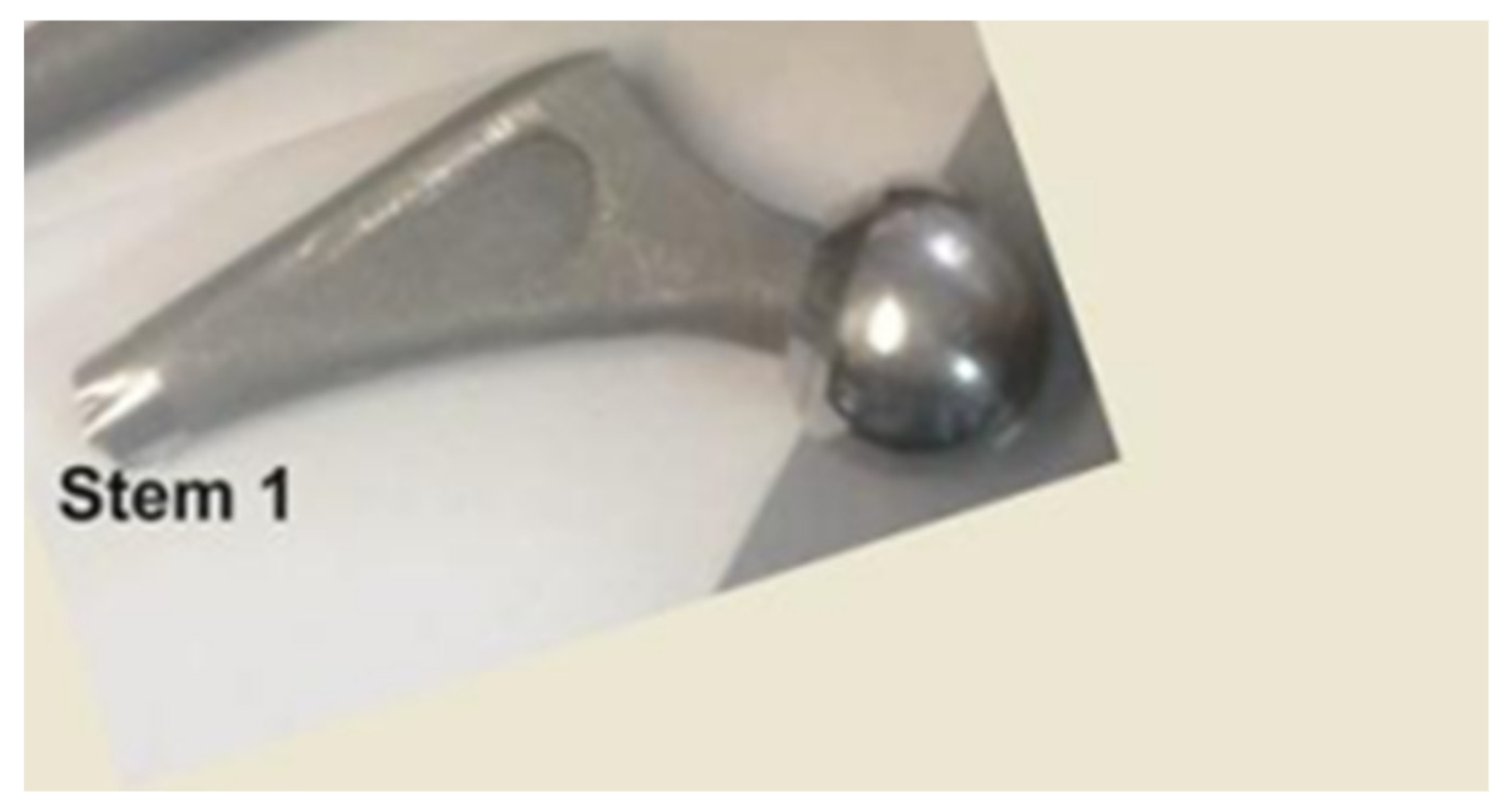

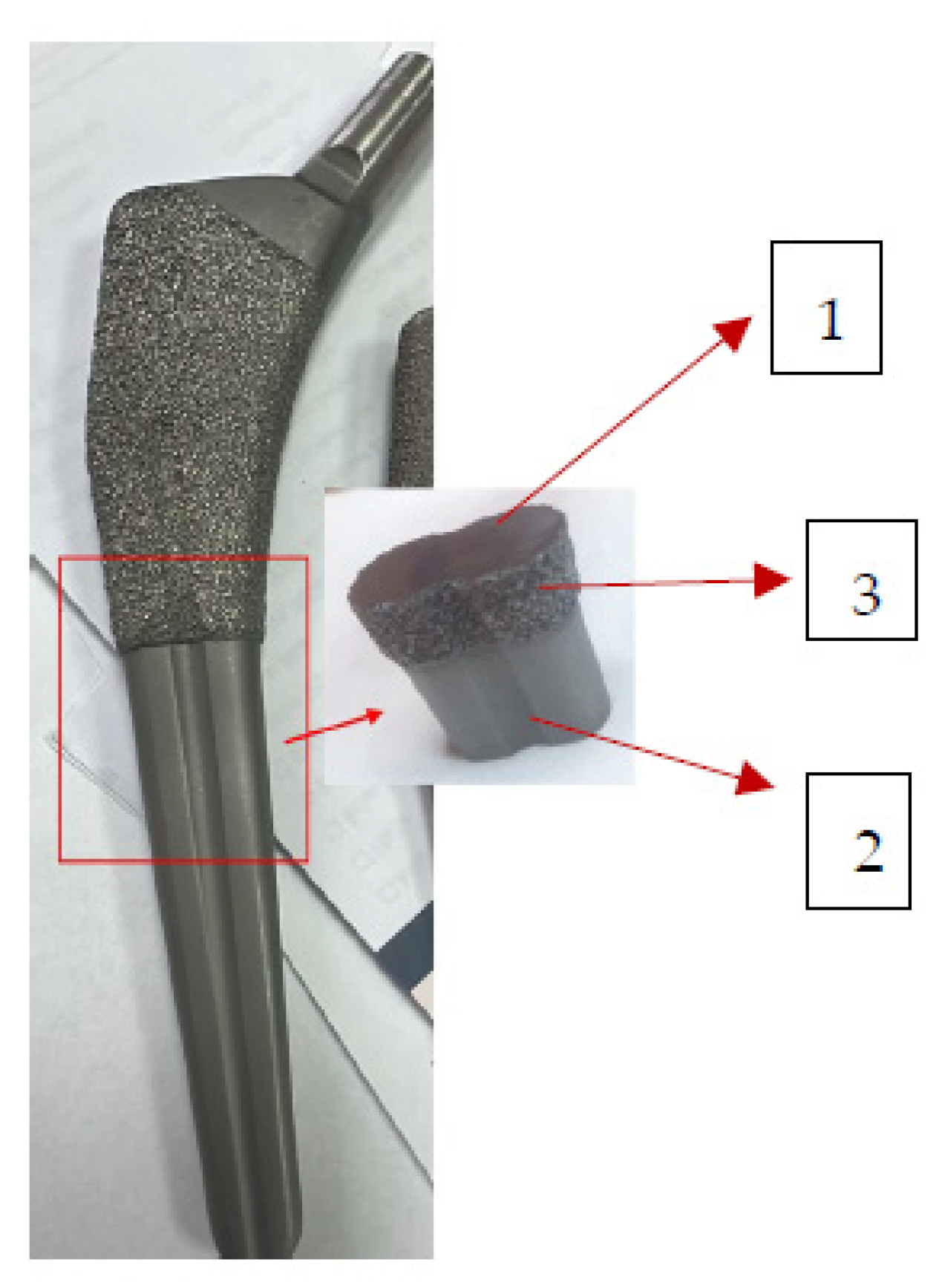

| Sample Name | Type | Condition | Source | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem 1 -fragment from the broken end | Solid, Ti-alloy +HAp, femoral stem | Broken approx. perpendicular to its longitudinal axis, 7 years used unbroken, 6 months used broken | Femur of patient M, aged over 65 years with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, chronic renal disease, azotaemia, uraemia |

L=20 mm, l=11 mm and h=6.56 mm |

| Stem 2 -fragment from the distal end | Solid, Ti-alloy +HAp, femoral stem | Unutilized | Unutilized | L=20 mm, l=11 mm and h=6.56 mm |

| Stem 3- fragment from the distal end | Solid, Ti-alloy +HAP*, femoral stem | Unutilized | Unutilized | L=20 mm, l=11 mm and h=6.56 mm |

| Synthetic plasma (Table 3) | Liquid | Synthesized | 50 µL/sample | |

| 3 x soft tissue fragments | Solid | Ex vivo direct | Surface of Stem 1 | 1.5 cm2 1.098 g each |

| Bone tissue fragment with thin metal layer | Solid | Ex vivo direct | Surface of Stem 1 | 1.75 cm2 2.532 g |

| Compound Added to the “Healthy” Synthetic Plasma | Concentration in “Healthy Synthetic Plasma” [mg/dL] | Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose |

266 |

F1 |

|

| Urea | 119 |

||

| Glucose | 118 | F2 | |

| Urea | 85 |

||

| Glucose | 95 | M | |

| Urea | 50 | ||

| Stem1, Layer | Stem1, Substrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Element | At. % | Element | At. % |

| Titanium | 24.05 ± 1.73 | Titanium | 75.09 ± 2.91 |

| Aluminium | 10.53 ± 0.70 | Aluminium | 7.02 ± 0.27 |

| Vanadium | 0.82 ± 0.09 | Vanadium | 2.79 ± 0.14 |

| Oxygen | 55.22 ± 4.95 | Carbon | 8.50 ± 0.41 |

| Calcium | 0.81 ± 0.07 | Oxygen | 5.60 ± 0.42 |

| Phosphorus | 0.001 ± 0.00 | Nitrogen | 0.99 ± 0.10 |

| Carbon | 5.73 ± 0.48 | ||

| Silicon | 1.00 ± 0.09 | ||

| Sodium | 0.99 ± 0.10 | ||

| Potassium | 0.31 ± 0.04 | ||

| Iron | 0.30 ± 0.05 | ||

| Magnesium | 0.18 ± 0.04 | ||

| Molybdenum | 0.05 ± 0.03 | ||

| 99.991 ±8.37 | 99.99 ± 4.25 | ||

| Stem 2, Substrate | Stem 2, Fine Layer | Stem 2 Rough, Layer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | At. % | Element | At. % | Element | At. % |

| Titanium | 72.52688066 | Titanium | 60.290 | Titanium | 37.180 |

| Aluminium | 7.863345632 | Aluminium | 3.536 | Aluminium | 3.411 |

| Vanadium | 2.347607468 | Vanadium | 1.902 | Vanadium | 1.300 |

| Silicon | 0.132498649 | Silicon | 3.725 | Silicon | 0.347 |

| Iron | 0.074318149 | Iron | 0.760 | Iron | 0.079 |

| Oxygen | 7.407082668 | Calcium | 0.609 | Calcium | 0.097 |

| Nitrogen | 0.908577893 | Phosphorus | 0.001 | Phosphorus | 0.043 |

| Carbon | 8.739688878 | Oxygen | 24.923 | Oxygen | 28.494 |

| Carbon | 3.590 | Carbon | 28.184 | ||

| Sodium | 0.512 | Sodium | 0.671 | ||

| Magnesium | 0.115 | Magnesium | 0.091 | ||

| Chlorine | 0.068 | ||||

| Potassium | 0.035 | ||||

| Sulphur | 0.001 | ||||

| 100.000 | 99.963 | 99.963 | 100.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).