Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

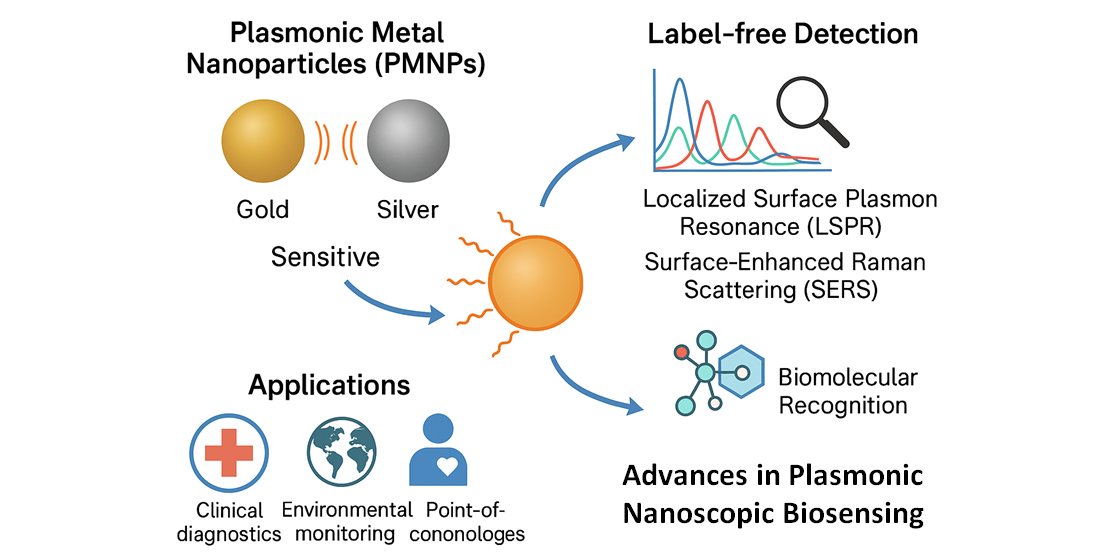

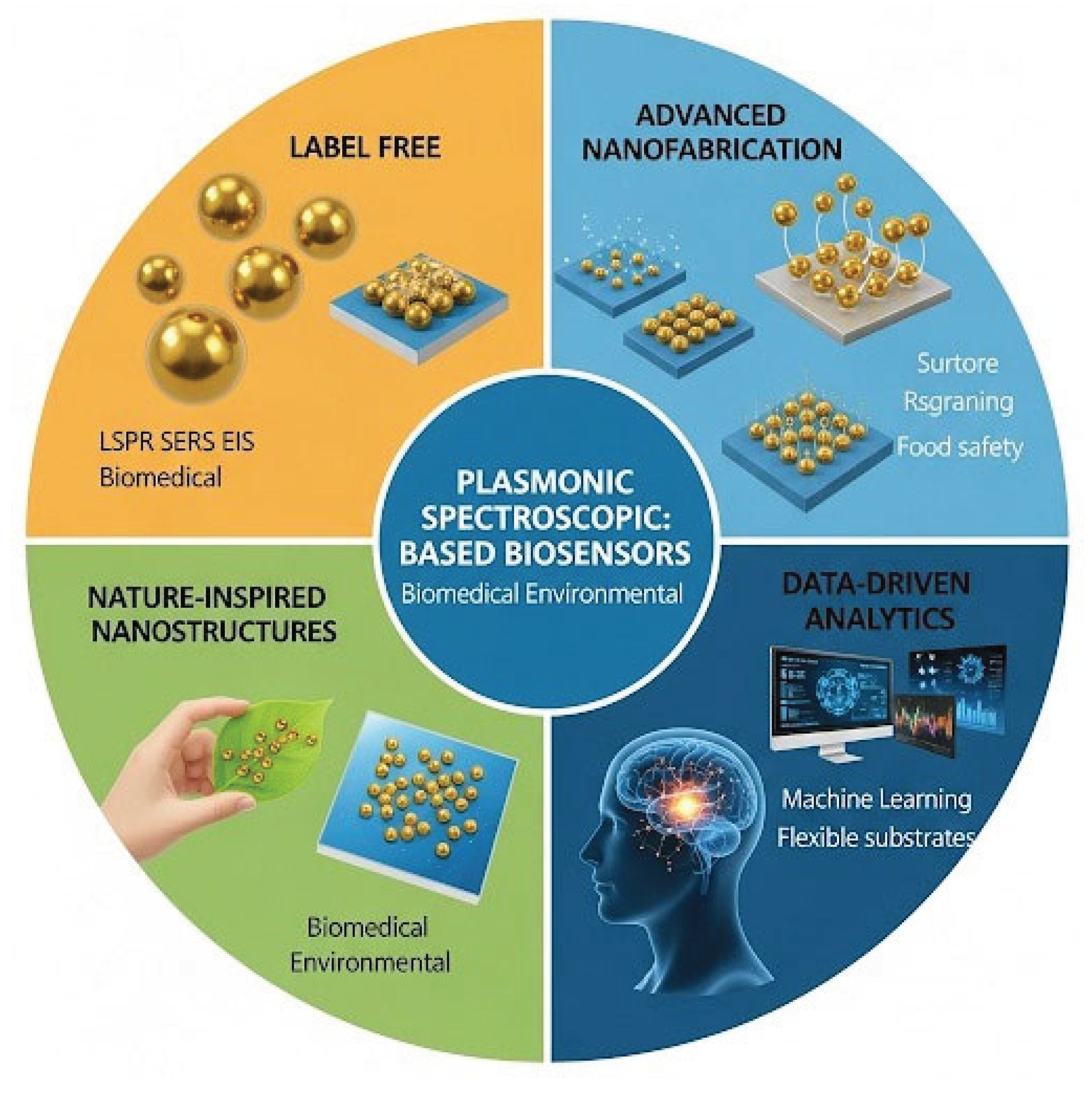

1. Introduction

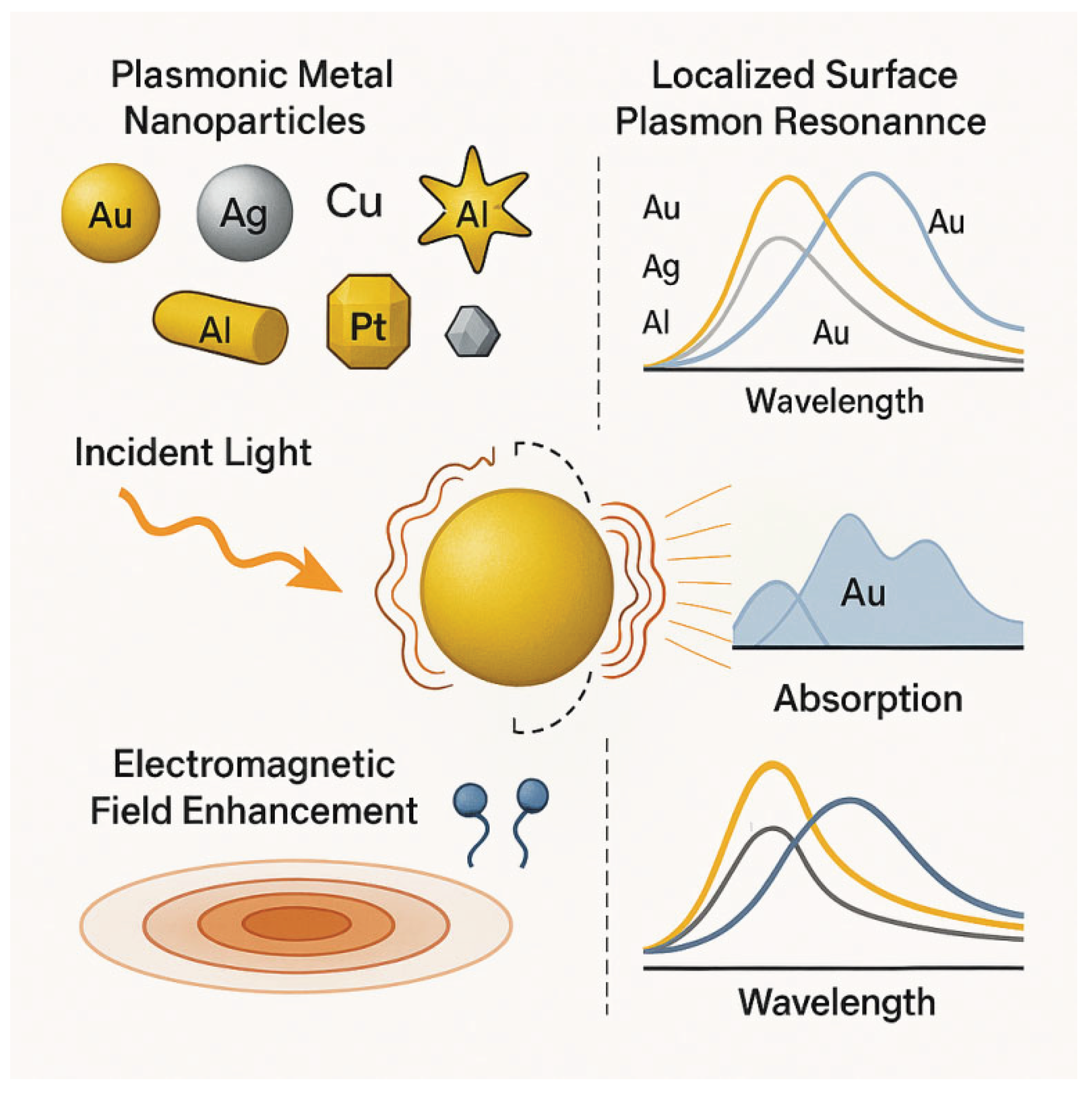

2. Fundamentals of Plasmonic Nanoparticles

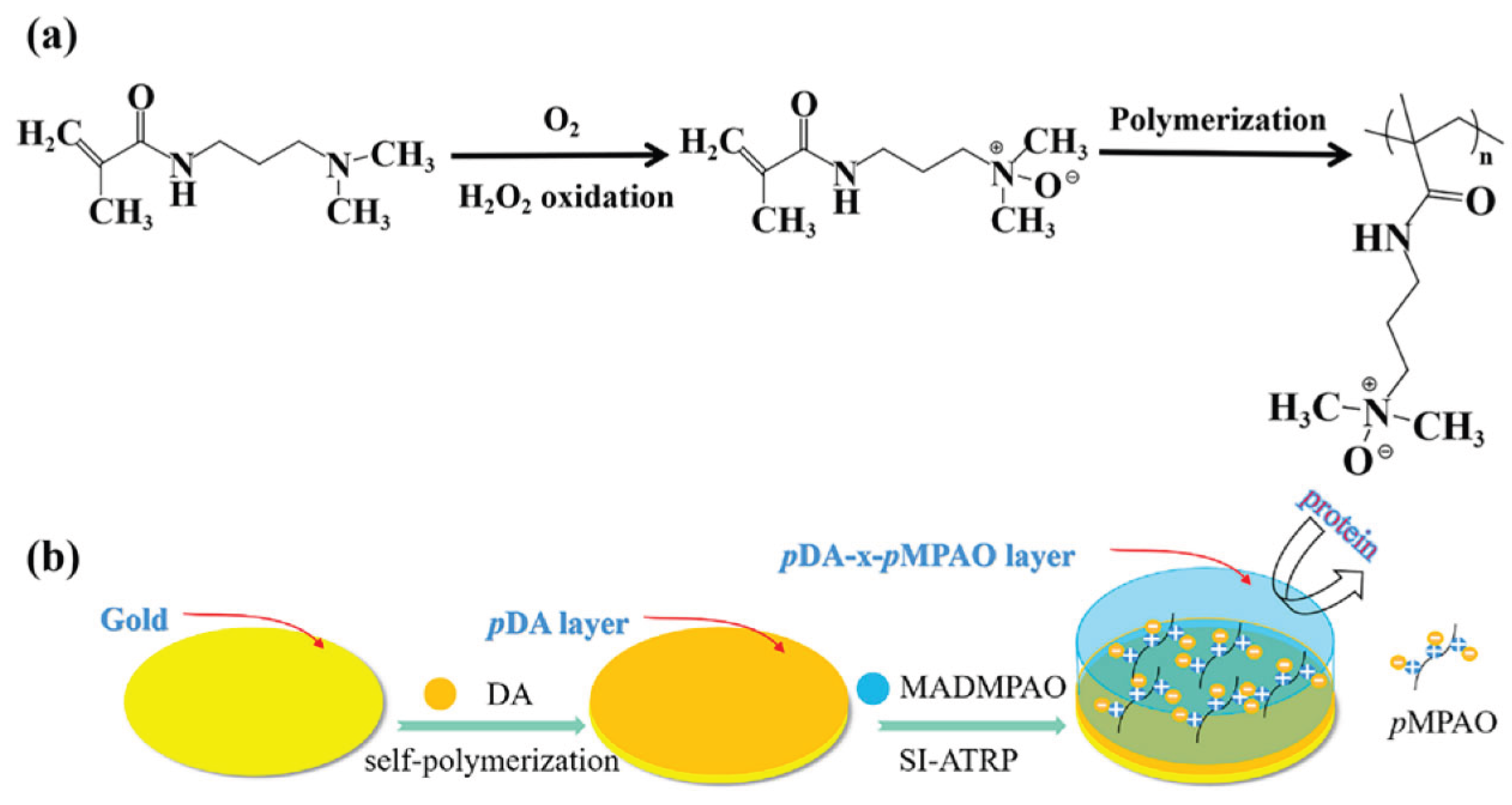

3. Design Strategies for Biosensing Platforms

4. Spectroscopic Techniques in Biosensing

4.1. Localize Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) Biosensors

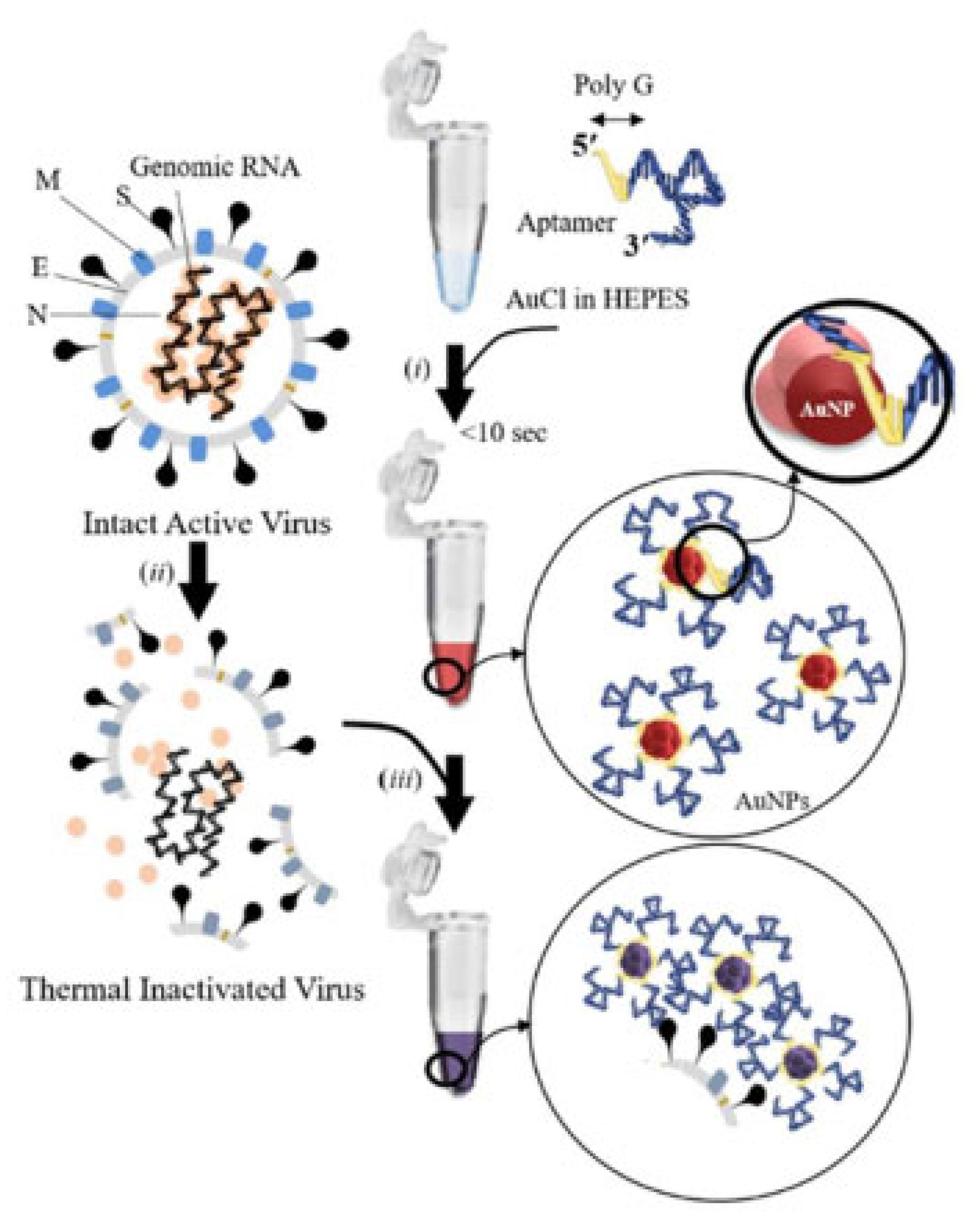

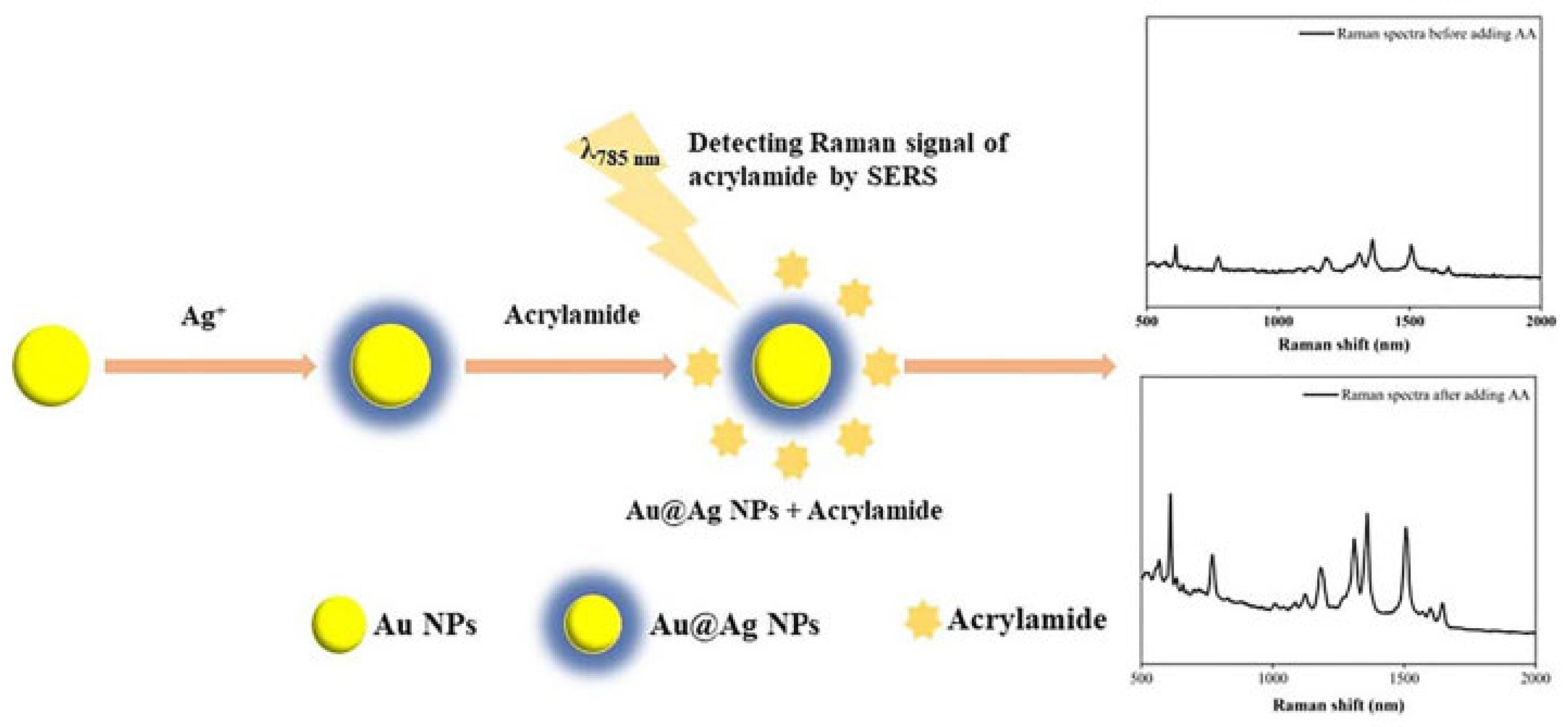

4.2. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Biosensors

5. Label-Free Detection Strategies

6. Biomedical And Environmental Applications

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Reproducibility, Stability, and Scalability

6.2. Emerging Technological Trends

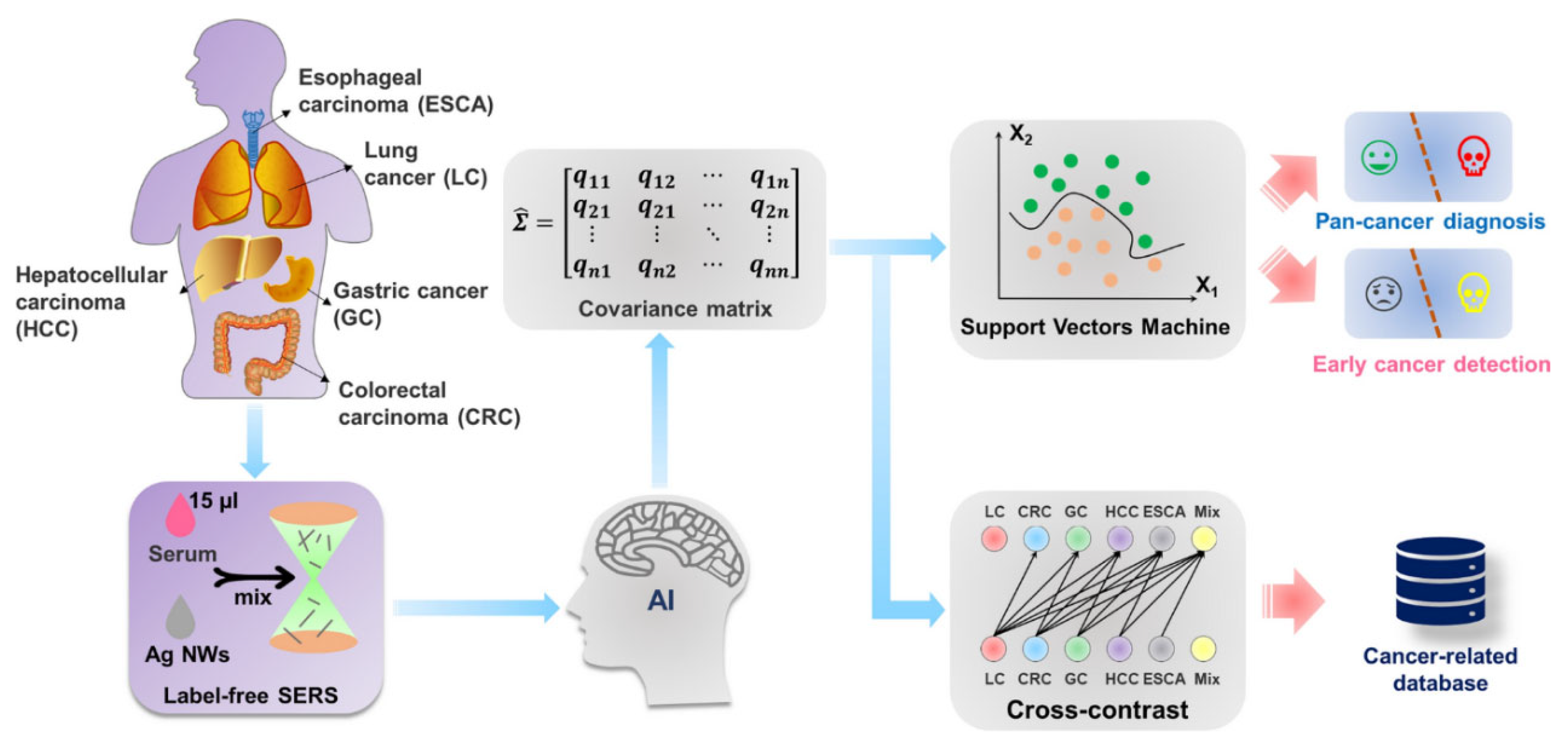

6.2.1. Machine Learning-Assisted Spectral Analysis

6.2.2. Quantum Plasmonics

6.2.3. Bioinspired Architectures

6.3. Outlook on Clinical Translation and Commercialization

6.4. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Reference

Author Contributions

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hang Y, Wang A, Wu N. Plasmonic silver and gold nanoparticles: shape- and structure-modulated plasmonic functionality for point-of-caring sensing, bio-imaging and medical therapy. Chemical Society Reviews 2024;53:2932-71. [CrossRef]

- Nanda BP, Rani P, Paul P, Aman, Ganti SS, Bhatia R. Recent trends and impact of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) in modern analysis. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2024;14:100959. [CrossRef]

- Samuel VR, Rao KJ. A review on label free biosensors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X 2022;11:100216. [CrossRef]

- Needham L-M, Saavedra C, Rasch JK, Sole-Barber D, Schweitzer BS, Fairhall AJ, et al. Label-free detection and profiling of individual solution-phase molecules. Nature 2024;629:1062-8. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Majdinasab M, Khan R, Li Z, Hayat A, Marty JL. Nanomaterials in fluorescence-based biosensors: Defining key roles. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2021;27:100774. [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda P, Xynomilakis O, Casati S, Ottria R. Fluorescence-Based Enzyme Activity Assay: Ascertaining the Activity and Inhibition of Endocannabinoid Hydrolytic Enzymes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences2024. [CrossRef]

- Rabbani A, Rudacille R, Hasegawa K. Local Refractive Index Sensitivity of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024;128:19210-21. [CrossRef]

- Cialla-May D, Bonifacio A, Markin A, Markina N, Fornasaro S, Dwivedi A, et al. Recent advances of surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) in optical biosensing. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024;181:117990. [CrossRef]

- Khondakar KR, Mazumdar H, Das S, Kaushik A. Machine learning (ML)-assisted surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy (SERS) technologies for sustainable health. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2025;344:103594. [CrossRef]

- Barucci A, D’Andrea C, Farnesi E, Banchelli M, Amicucci C, de Angelis M, et al. Label-free SERS detection of proteins based on machine learning classification of chemo-structural determinants. Analyst 2021;146:674-82.

- Chomean S, Nakkam N, Tassaneeyakul W, Attapong J, Kaset C. Development of label-free electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for the detection of HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-B*15:21 for the prevention of carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Analytical Biochemistry 2022;658:114931. [CrossRef]

- Rejeeth C, Almeer R, Sharma A, Varukattu NB. Label-free electrochemical assessment of human serum and cancer cells to determine the folate receptor cancer biomarker. Bioelectrochemistry 2025;163:108883. [CrossRef]

- Rejeeth C, Sharma A, Kannan S, Kumar RS, Almansour AI, Arumugam N, et al. Label-Free Electrochemical Detection of the Cancer Biomarker Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor in Human Serum and Cancer Cells. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2022;8:826-33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Rejeeth C, Xu W, Zhu C, Liu X, Wan J, et al. Label-Free Electrochemical Sensor for CD44 by Ligand-Protein Interaction. Analytical Chemistry 2019;91:7078-85.

- Garrote BL, Santos A, Bueno PR. Perspectives on and Precautions for the Uses of Electric Spectroscopic Methods in Label-free Biosensing Applications. ACS Sensors 2019;4:2216-27. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Sun Z, Sun K, Liu Q, Chu W, Fu L, et al. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy-Based Biosensors for Label-Free Detection of Pathogens. Biosensors2025. [CrossRef]

- Chandra A, Kumar V, Garnaik UC, Dada R, Qamar I, Goel VK, et al. Unveiling the Molecular Secrets: A Comprehensive Review of Raman Spectroscopy in Biological Research. ACS Omega 2024;9:50049-63. [CrossRef]

- Schorr HC, Schultz ZD. Digital surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy for quantifiable single molecule detection in flow. Analyst 2024;149:3711-5. [CrossRef]

- Demishkevich E, Zyubin A, Seteikin A, Samusev I, Park I, Hwangbo CK, et al. Synthesis Methods and Optical Sensing Applications of Plasmonic Metal Nanoparticles Made from Rhodium, Platinum, Gold, or Silver. Materials2023. [CrossRef]

- McOyi MP, Mpofu KT, Sekhwama M, Mthunzi-Kufa P. Developments in Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Plasmonics 2025;20:5481-520.

- de Albuquerque CDL, Zoltowski CM, Scarpitti BT, Shoup DN, Schultz ZD. Spectrally Resolved Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Imaging Reveals Plasmon-Mediated Chemical Transformations. ACS Nanoscience Au 2021;1:38-46. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Zhang T, Zhang L, Wang G, Huang X, Li W, et al. Synergistic enhancement of chemical and electromagnetic effects in a Ti3C2Tx/AgNPs two-dimensional SERS substrate for ultra-sensitive detection. Analytica Chimica Acta 2024;1331:343330. [CrossRef]

- Almomani AS, Omar AF, Oglat AA, Al-Mafarjy SS, Dheyab MA, Khazaalah TH. Developed a unique technique for creating stable gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to explore their potential against cancer. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 2025;53:142-52. [CrossRef]

- Devaraji M, Thanikachalam PV, Elumalai K. The potential of copper oxide nanoparticles in nanomedicine: A comprehensive review. Biotechnology Notes 2024;5:80-99. [CrossRef]

- Shukla S, Arora P. Aluminum as a competitive plasmonic material for the entire electromagnetic spectrum: A review. Results in Optics 2025;18:100760. [CrossRef]

- Pisarek M, Krawczyk M, Hołdyński M, Ambroziak R, Bieńkowski K, Roguska A, et al. Hybrid Nanostructures Based on TiO2 Nanotubes with Ag, Au, or Bimetallic Au–Ag Deposits for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Applications. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2023;127:24200-10. [CrossRef]

- Oberhaus FV, Frense D, Beckmann D. Immobilization Techniques for Aptamers on Gold Electrodes for the Electrochemical Detection of Proteins: A Review. Biosensors2020. [CrossRef]

- Ali K, Munawar I, Manan S, Nawazish F, Fatima B, Jabeen F, et al. Development of polymer monolith-MOF hybrid via surface functionalization for bioanalytical sciences. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2025;417:3503-11. [CrossRef]

- Zou S, Peng G, Ma Z. Surface-Functionalizing Strategies for Multiplexed Molecular Biosensing: Developments Powered by Advancements in Nanotechnologies. Nanomaterials2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Shi Q. Bioinspired Dopamine and N-Oxide-Based Zwitterionic Polymer Brushes for Fouling Resistance Surfaces. Polymers2024. [CrossRef]

- Massia SP, Hubbell JA. Convalent surface immobilization of Arg-Gly-Asp- and Tyr-Ile-Gly-Ser-Arg-containing peptides to obtain well-defined cell-adhesive substrates. Analytical Biochemistry 1990;187:292-301. [CrossRef]

- Yoo SS, Ho J-W, Shin D-I, Kim M, Hong S, Lee JH, et al. Simultaneously intensified plasmonic and charge transfer effects in surface enhanced Raman scattering sensors using an MXene-blanketed Au nanoparticle assembly. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2022;10:2945-56. [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Guo Z, Liu Z. Recent Advances in Rational Design and Engineering of Signal-Amplifying Substrates for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering-Based Bioassays. Chemosensors2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghodeswar US, Joshi KV, Waje MG, Patil TR, Upadhye S, Shelke N, et al. Sensitivity Improved Plasmonic Biosensors with Coupling Quantum-Dots for Optimization of Biosensing Process: Application in Biomedical Diagnostics and Environmental Monitoring Processes. Plasmonics 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ma X, Guo G, Wu X, Wu Q, Liu F, Zhang H, et al. Advances in Integration, Wearable Applications, and Artificial Intelligence of Biomedical Microfluidics Systems. Micromachines2023. [CrossRef]

- Abbasiasl T, Mirlou F, Istif E, Ceylan Koydemir H, Beker L. A wearable paper-integrated microfluidic device for sequential analysis of sweat based on capillary action††Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Fig. S1–S7.Sensors and Diagnostics 2022;1:775-86. [CrossRef]

- Simone, G. Trends of Biosensing: Plasmonics through Miniaturization and Quantum Sensing. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2024;54:2183-208. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhang X. Microfluidics-Based Plasmonic Biosensing System Based on Patterned Plasmonic Nanostructure Arrays. Micromachines2021. [CrossRef]

- Austin Suthanthiraraj PP, Sen AK. Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) biosensor based on thermally annealed silver nanostructures with on-chip blood-plasma separation for the detection of dengue non-structural protein NS1 antigen. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019;132:38-46.

- Singh S, Singh PK, Umar A, Lohia P, Albargi H, Castañeda L, et al. 2D Nanomaterial-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Biosensing Applications. Micromachines2020. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi T, Latag GV. Self-Assembled Monolayers as Platforms for Nanobiotechnology and Biointerface Research: Fabrication, Analysis, Mechanisms, and Design. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2025;8:8570-87. [CrossRef]

- Kaye S, Zeng Z, Sanders M, Chittur K, Koelle PM, Lindquist R, et al. Label-free detection of DNA hybridization with a compact LSPR-based fiber-optic sensor. Analyst 2017;142:1974-81. [CrossRef]

- Lu M, Zhu H, Lin M, Wang F, Hong L, Masson J-F, et al. Comparative study of block copolymer-templated localized surface plasmon resonance optical fiber biosensors: CTAB or citrate-stabilized gold nanorods. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021;329:129094. [CrossRef]

- Alikhanian A, Shadmehri N, Borghei Y-S, Arefian E, Habibi-Rezaei M. Rapid, Label-Free LSPR Aptasensor for Sensitive Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in Throat Swab Samples. Plasmonics 2025. [CrossRef]

- Petronella F, De Biase D, Zaccagnini F, Verrina V, Lim S-I, Jeong K-U, et al. Label-free and reusable antibody-functionalized gold nanorod arrays for the rapid detection of Escherichia coli cells in a water dispersion. Environmental Science: Nano 2022;9:3343-60. [CrossRef]

- Hoque SZ, Somasundaram L, Samy RA, Dawane A, Sen AK. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Biomarker Detection with On-Chip Microfluidic Devices in Point-of-Care Diagnostics. In: Joshi SN, Chandra P, editors. Advanced Micro- and Nano-manufacturing Technologies: Applications in Biochemical and Biomedical Engineering. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2022. p. 199-223.

- Sayin S, Zhou Y, Wang S, Acosta Rodriguez A, Zaghloul M. Development of Liquid-Phase Plasmonic Sensor Platforms for Prospective Biomedical Applications. Sensors2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Lu Y, Liu Y, Hu X, Chen H. Current strategies of plasmonic nanoparticles assisted surface-enhanced Raman scattering toward biosensor studies. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2023;228:115231. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Yue Z, Fang X, Lin H, Wang L, Cao L, et al. SERS detection of thiram using polyacrylamide hydrogel-enclosed gold nanoparticle aggregates. Science of The Total Environment 2023;856:159108. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Chen J, Xu W, Sun B, Wu J, Chen Q, et al. Highly homogeneous bimetallic core–shell Au@Ag nanoparticles with embedded internal standard fabrication using a microreactor for reliable quantitative SERS detection. Materials Chemistry Frontiers 2023;7:1100-9.

- Awiaz G, Lin J, Wu A. Recent advances of Au@Ag core–shell SERS-based biosensors. Exploration 2023;3:20220072.

- Xie Y, Xu J, Shao D, Liu Y, Qu X, Hu S, et al. SERS-Based Local Field Enhancement in Biosensing Applications. Molecules2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Song C, He X, Liu J, Chao J, Wang L. DNA-mediated precise regulation of SERS hotspots for biosensing and bioimaging. Chemical Society Reviews 2025;54:5836-63.

- Maher, RC. SERS Hot Spots. In: Kumar CSSR, editor. Raman Spectroscopy for Nanomaterials Characterization. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. p. 215-60.

- Liu G, Mu Z, Guo J, Shan K, Shang X, Yu J, et al. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering as a potential strategy for wearable flexible sensing and point-of-care testing non-invasive medical diagnosis. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022;Volume 10 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Haque Chowdhury MA, Tasnim N, Hossain M, Habib A. Flexible, stretchable, and single-molecule-sensitive SERS-active sensor for wearable biosensing applications. RSC Advances 2023;13:20787-98. [CrossRef]

- Unser S, Bruzas I, He J, Sagle L. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensing: Current Challenges and Approaches. Sensors2015. p. 15684-716. [CrossRef]

- Kabashin AV, Kravets VG, Grigorenko AN. Label-free optical biosensing: going beyond the limits. Chemical Society Reviews 2023;52:6554-85. [CrossRef]

- Soler M, Lechuga LM. Principles, technologies, and applications of plasmonic biosensors. Journal of Applied Physics 2021;129:111102. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadasi M, Grist S, Mitchell M, Newton K, Kioussis S, Chowdhury S, et al. An integrated evanescent-field biosensor in silicon2024.

- Puumala LS, Grist SM, Wickremasinghe K, Al-Qadasi MA, Chowdhury SJ, Liu Y, et al. An Optimization Framework for Silicon Photonic Evanescent-Field Biosensors Using Sub-Wavelength Gratings. Biosensors2022.

- Dong S, He D, Zhang Q, Huang C, Hu Z, Zhang C, et al. Early cancer detection by serum biomolecular fingerprinting spectroscopy with machine learning. eLight 2023;3:17. [CrossRef]

- Yuan K, Jurado-Sánchez B, Escarpa A. Nanomaterials meet surface-enhanced Raman scattering towards enhanced clinical diagnosis: a review. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022;20:537. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Rahman A, Huang Q, Vikesland PJ. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy enabled evaluation of bacterial inactivation. Water Research 2022;220:118668. [CrossRef]

- Lin C, Li Y, Peng Y, Zhao S, Xu M, Zhang L, et al. Recent development of surface-enhanced Raman scattering for biosensing. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2023;21:149. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Aljuhani W, Zhang Y, Ye Z, Li C, Bell SEJ. A practical approach to quantitative analytical surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Chemical Society Reviews 2025;54:62-84. [CrossRef]

- Choi JR, Yong KW, Choi JY, Cowie AC. Emerging Point-of-care Technologies for Food Safety Analysis. Sensors2019.

- Rayani PK, Changder S. Sensor-based continuous user authentication on smartphone through machine learning. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2023;96:104750. [CrossRef]

- Fdez-Sanromán A, Bernárdez-Rodas N, Rosales E, Pazos M, González-Romero E, Sanromán MÁ. Biosensor Technologies for Water Quality: Detection of Emerging Contaminants and Pathogens. Biosensors2025. [CrossRef]

- Iyiola A, Setufe S, Ofori-Boateng E, Jacob B, Ogwu M. Biomarkers for the Detection of Pollutants from the Water Environment. 2024. p. 569-602.

- Caruncho-Pérez S, Giráldez A, Terrón D, Pazos M, Sanromán MÁ, González-Romero E. Electrochemistry solving problems in water disinfection: Direct voltammetric monitoring of pyocyanin from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025;522:167828. [CrossRef]

- Karim, M. Biosensors: Ethical, Regulatory, and Legal Issues. 2021. p. 679-705.

| Design Domain | Key Innovation | Performance Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Functionalization | MOF–polymer hybrids, zwitterionic brushes | ↑ Selectivity, ↓ non-specific binding | [28,30] |

| Bioinspired Interfaces | Peptide motifs, ECM mimics | ↑ Biorecognition under flow | [31] |

| Signal Amplification | MXene–Au hybrids, QD-coupled metasurfaces | ↑ SERS EF, ↓ LOD, multiplexing | [32,34] |

| Substrate Engineering | Porous scaffolds, anisotropic clusters | ↑ Hotspot density, analyte accessibility | [33] |

| Miniaturization | Paper-based microfluidics, wearable patches | ↑ Portability, ↓ sample volume | [35,36] |

| Digital Integration | Smartphone interfaces, quantum plasmonics | ↑ Accessibility, real-time feedback | [37,38] |

| Application Domain | Key Innovation | Detection Limit / Benefit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Interactions | Plasmon rulers, SAM-modified nanorods | High kinetic resolution, label-free | [40,41] |

| DNA Hybridization | Fiber-optic probes, polymer-templated AuNPs | 10 fM to 67 pM, portable formats | [42,43] |

| Pathogen Detection | Aptamer–AuNP sensors, reusable nanorod arrays | ~10³ copies/mL (SARS-CoV-2), 8.4 CFU/mL | [44,45] |

| Microfluidic Integration | PDMS channels, nanohole arrays | Real-time, low-volume, multiplexed assays | [46,47] |

| Design Feature | Key Advancement | Performance Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core–Shell Nanostructures | Au@Ag NPs, microfluidic synthesis | ↑ SERS EF, ↓ LOD, improved reproducibility | [49,50,51] |

| Nanogap Engineering | DNA-mediated hotspots, 3D crevice structures | ↑ Field localization, single-molecule SERS | [52,53,54] |

| Flexible Substrates | PDMS, silk fibroin, 3D arrays | ↑ Wearability, ↓ sample volume, POCT-ready | [52,55,56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).