1. Introduction

Object tracking is a core problem in computer vision that aims to localize one or more objects over time in a sequence of video frames. It plays a vital role in a wide array of real-world applications, including video surveillance, autonomous driving, robotics, augmented reality, human-computer interaction, and sports analytics. Tracking involves not only detecting objects in each frame but also maintaining consistent identities despite challenges such as occlusion, motion blur, illumination variation, and object deformation.

To structure this evolving field, this survey categorizes tracking into three major settings: Single Object Tracking (SOT), where a single target is tracked through a video; Multi-Object Tracking (MOT), which involves identifying and maintaining multiple object identities; and Long-Term Tracking (LTT), where the tracker must re-detect the object after occlusion or disappearance. Each setting poses unique challenges and inspires different methodological choices.

Over the years, object tracking methods have progressed from traditional algorithms based on handcrafted features and probabilistic models to modern deep learning-based frameworks. Recent advancements include Siamese-based trackers, transformer architectures, and end-to-end joint detection and tracking models. Additionally, the rise of vision-language models and open-vocabulary trackers marks a new direction toward more flexible and generalizable tracking systems.

To provide a comprehensive overview, this survey is organized into several key sections, each focused on a different axis of the object tracking landscape: foundational problem settings and taxonomy, traditional methods, deep learning approaches, multi-object tracking architectures, long-term tracking, benchmarks and metrics, and finally, emerging trends such as foundation models and multimodal tracking.

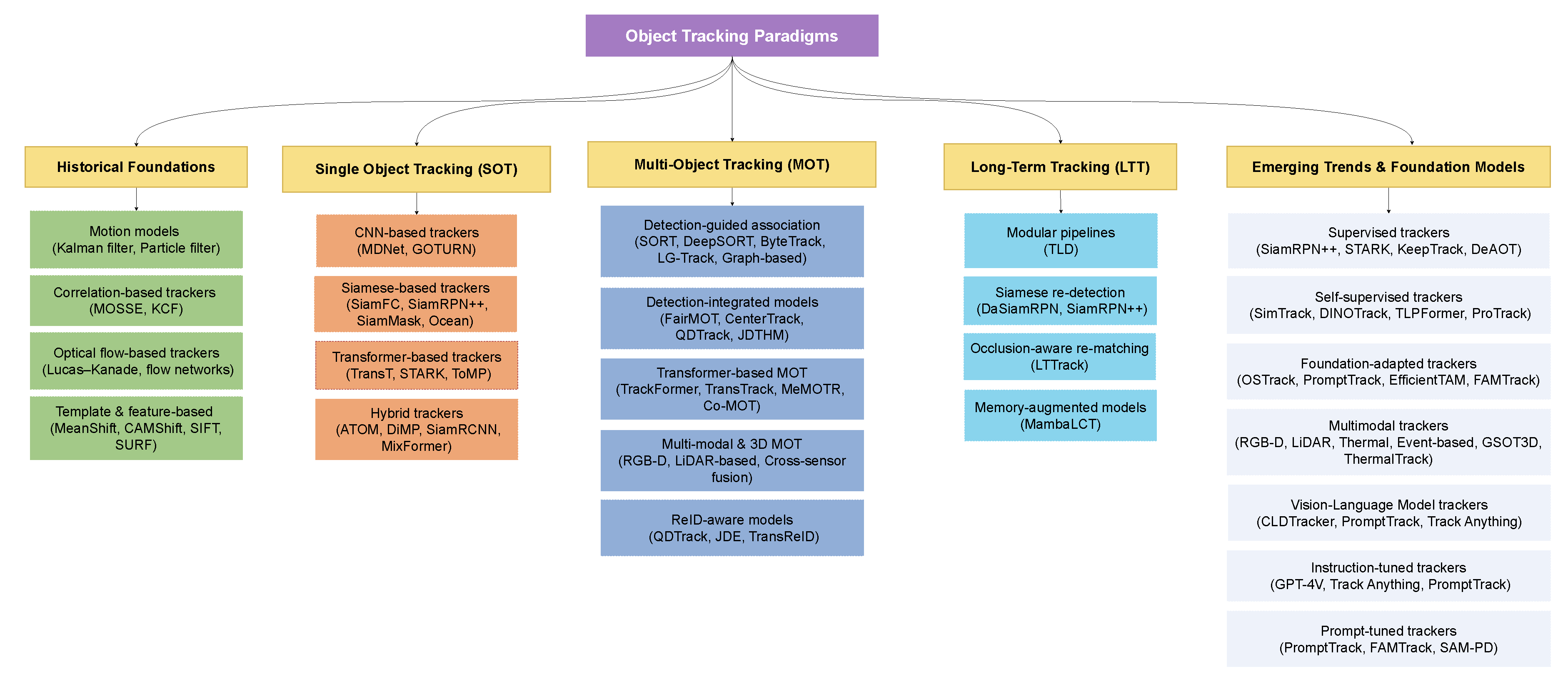

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of object tracking paradigms, spanning historical foundations, single-object tracking (SOT), multi-object tracking (MOT), long-term tracking (LTT), and emerging trends leveraging foundation and vision-language models. Each branch highlights representative methods and architectures across the evolution of tracking research

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of object tracking paradigms, spanning historical foundations, single-object tracking (SOT), multi-object tracking (MOT), long-term tracking (LTT), and emerging trends leveraging foundation and vision-language models. Each branch highlights representative methods and architectures across the evolution of tracking research

This survey aims to serve as a unified reference for researchers and practitioners in the object tracking community by:

Presenting a structured taxonomy of object tracking paradigms.

Reviewing traditional tracking methods such as correlation filters, optical flow, and probabilistic filters.

Detailing deep learning-based methods, including CNN-based, Siamese-based, and transformer-based trackers.

Highlighting key advances in multi-object tracking, with a focus on data association, identity preservation, and joint detection-tracking architectures.

Discussing recent developments in open-vocabulary and multimodal tracking using foundation models.

Summarizing widely-used datasets and

2. Problem Formulation and Taxonomy

Object tracking is a fundamental task in computer vision that involves estimating the state (e.g., position, scale, and shape) of a target object as it moves through a video sequence. The primary objective is to maintain a continuous and accurate trajectory of the object over time, despite challenges such as occlusions, abrupt motion, background clutter, and varying illumination or viewpoint conditions. Tracking algorithms must be robust to appearance variations, efficient enough for real-time performance, and capable of distinguishing the target from distractors in complex environments.

Let denote a sequence of T video frames. The goal is to predict a set of spatial coordinates or bounding boxes in each frame that correspond to the same physical object across time. More formally, the tracker estimates the evolving object states using the current and past observations, possibly incorporating prior knowledge such as motion patterns, category information, or contextual cues.

Contemporary tracking systems typically involve several key components:

Feature Extraction: Transforming raw pixels into semantically meaningful embeddings using deep neural networks, such as convolutional or transformer-based backbones.

Motion Modeling: Capturing temporal dynamics using techniques like optical flow, Kalman filters, or learned motion predictors to estimate object displacement across frames.

Data Association: Linking estimated object states across time by matching detections or predictions using appearance similarity, spatial proximity, or temporal consistency.

Model Update: Adapting the tracking model online to accommodate changes in object appearance, scale, pose, and environmental context.

While the core objective remains consistent, tracking formulations differ based on the number of objects tracked, the temporal length of tracking, and the constraints on initialization or supervision. These scenarios are explored in detail in the

3. Problem Formulation and Taxonomy

Object tracking is a fundamental task in computer vision that involves estimating the state (e.g., position, scale, and shape) of a target object as it moves through a video sequence. The primary objective is to maintain a continuous and accurate trajectory of the object over time, despite challenges such as occlusions, abrupt motion, background clutter, and varying illumination or viewpoint conditions. Tracking algorithms must be robust to appearance variations, efficient enough for real-time performance, and capable of distinguishing the target from distractors in complex environments.

Let denote a sequence of T video frames. The goal is to predict a set of spatial coordinates or bounding boxes in each frame that correspond to the same physical object across time. More formally, the tracker estimates the evolving object states using the current and past observations, possibly incorporating prior knowledge such as motion patterns, category information, or contextual cues.

Contemporary tracking systems typically involve several key components:

Feature Extraction: Transforming raw pixels into semantically meaningful embeddings using deep neural networks, such as convolutional or transformer-based backbones.

Motion Modeling: Capturing temporal dynamics using techniques like optical flow, Kalman filters, or learned motion predictors to estimate object displacement across frames.

Data Association: Linking estimated object states across time by matching detections or predictions using appearance similarity, spatial proximity, or temporal consistency.

Model Update: Adapting the tracking model online to accommodate changes in object appearance, scale, pose, and environmental context.

While the core objective remains consistent, tracking formulations differ based on the number of objects tracked, the temporal length of tracking, and the constraints on initialization or supervision. These scenarios are explored in detail in the

4. Single Object Tracking (SOT)

Single Object Tracking (SOT) involves estimating the trajectory of a target object across a video sequence, given its initial bounding box in the first frame [

1]. Unlike multi-object tracking, SOT concentrates on localizing a single instance without requiring class labels or re-identification. The task is challenging because the target may undergo occlusion, scale variation, rotation, deformation, or illumination change. While traditional methods relied on handcrafted features, correlation filters, and template matching [

2,

3], modern deep learning-based trackers represent the task as a learnable similarity function between the initial target template

and candidate regions

in the search frame

:

where

denotes the set of candidate regions and

is a learned similarity function parameterized by neural networks.

4.1. CNN-Based Trackers

The first wave of deep trackers used convolutional networks to replace handcrafted features with learned representations. MDNet cast tracking as a binary classification task, using shared convolutional layers trained across multiple domains and domain-specific fully connected layers updated online [

4]. This enabled robust discrimination under occlusion but suffered from slow inference due to repeated online fine-tuning. GOTURN instead approached tracking as direct bounding box regression, predicting target coordinates in a feed-forward manner without online updates [

5]. Although highly efficient, it lacked adaptation to appearance change. Hybrid CNN–detector trackers, inspired by the TLD framework, incorporated global re-detection modules to recover after failures, though they remained sensitive to drift when noisy updates occurred [

6].

4.2. Siamese-Based Trackers

Siamese networks marked a major shift by learning template–search similarity through shared feature embeddings. SiamFC introduced the fully convolutional Siamese design, where cross-correlation between template and search features produced a response map [

7]. While simple and real-time, it lacked scale adaptability. SiamRPN integrated a region proposal network to predict both classification scores and bounding box offsets, enabling more precise localization [

8]. Its successor, SiamRPN++, extended this with deeper backbones and spatial-aware sampling, which improved robustness at the cost of increased computation [

9]. Later extensions such as SiamMask and Ocean expanded the paradigm to include segmentation and attention-based matching for more fine-grained target modeling [

10,

11].

4.3. Transformer-Based Trackers

Transformers brought global attention and long-range reasoning to SOT. TransT removed reliance on anchors and region proposals by employing cross-attention between template and search regions, learning discriminative correlations directly [

12]. STARK extended this approach by treating tracking as sequence prediction, using spatio-temporal transformers to model historical and current features jointly [

13]. Other transformer-based designs such as ToMP adapted generic vision transformer backbones to tracking, tokenizing frames into patches and applying dense attention for fine-grained matching [

14]. These methods demonstrated the strength of attention-based models in handling clutter, occlusion, and appearance variability, though often at higher computational cost.

4.4. Hybrid Tracking Architectures

Hybrid trackers combine the strengths of convolutional, Siamese, and transformer paradigms. ATOM separated feature extraction from bounding box estimation, using a ResNet backbone and a target-specific regression head optimized online [

15]. DiMP improved upon this by introducing a meta-learned optimization module for faster and more robust online adaptation [

16]. SiamRCNN bridged Siamese matching and region-based detection, handling scale and aspect ratio variation more flexibly [

17]. More recent designs such as SiamBAN and MixFormer unified classification and regression into joint prediction heads, with MixFormer coupling transformers and convolutional backbones to achieve strong performance with fewer parameters [

18,

19]. These approaches illustrate the ongoing convergence of architectural ideas to achieve a balance between accuracy, adaptability, and efficiency.

Single Object Tracking has progressed from CNN classifiers and regressors to efficient Siamese similarity learning, transformer-driven architectures, and hybrid systems. The central theme across these methods is balancing real-time performance with robustness to appearance change and occlusion, with unified frameworks offering a promising path forward.

Table 1 summarizes prominent Single Object Tracking (SOT) models, highlighting their architectural categories, backbone designs, key strengths, limitations, and benchmark performance.

Table 1.

Single Object Tracking (SOT) models categorization.

Table 1.

Single Object Tracking (SOT) models categorization.

| Method |

Category |

Backbone |

Key Strength |

Key Weakness |

Performance (Dataset/Metric) |

| MDNet [4] |

CNN |

Conv + FC (multi-domain) |

Learns domain-invariant representations through multi-domain training; robust under challenging conditions such as heavy occlusion and background clutter; demonstrates strong generalization to unseen objects. |

Computationally expensive due to frequent online updates; suffers from low inference speed, limiting real-time usability; performance degrades in long sequences with rapid appearance variation. |

AUC: 0.678 (OTB100) |

| GOTURN [5] |

CNN |

Dual-input CNN regressor |

Extremely fast (>100 FPS), enabling real-time deployment; simple fully offline pipeline; no online fine-tuning needed; efficient feed-forward regression. |

Lacks adaptation to target appearance changes; brittle under occlusion, deformation, and scale variation; struggles with long-term robustness in cluttered environments. |

AUC: 0.46 (OTB100) |

| TLD-CNN [6] |

CNN |

CNN + online learner |

Combines detection and tracking, allowing recovery from failures; online learning enables adaptation to dynamic targets; can re-detect objects after drift or loss. |

Online updates prone to noise accumulation, leading to drift; high complexity compared to simpler Siamese models; unstable in highly cluttered or fast-moving scenarios. |

Precision: ∼0.56 (OTB100) |

| SiamFC [7] |

Siamese |

Shared CNN encoder |

Lightweight and efficient design; achieves real-time operation ( 86 FPS); end-to-end similarity learning via cross-correlation; robust against moderate distractors. |

Relies on fixed template without update, limiting adaptability; weak handling of scale and aspect ratio changes; fails under long occlusion or drastic appearance variation. |

AUC: 0.582 (OTB100) |

| SiamRPN [8] |

Siamese |

Siamese CNN + RPN |

Incorporates region proposal network (RPN) for accurate localization; handles scale variation better than SiamFC; improved robustness for short- to mid-term tracking. |

Strong dependency on anchor design introduces rigidity; limited adaptability to unseen object classes; inference cost increases compared to SiamFC. |

EAO: 0.41 (VOT2018) |

| SiamRPN++ [9] |

Siamese |

ResNet-50 Siamese |

Leverages deep residual features for strong representation; improved receptive fields and robustness; achieves state-of-the-art accuracy on multiple benchmarks. |

Computationally heavier than earlier Siamese trackers; constrained by anchor-based formulation; reduced efficiency in embedded or resource-limited systems. |

AUC: 0.696 (OTB100) |

| TransT [12] |

Transformer |

Cross/self-attention modules |

Exploits global context through self- and cross-attention; anchor-free design avoids hand-crafted priors; generalizes well to diverse object categories. |

High computational overhead during inference; requires large-scale pretraining for stability; slower than Siamese models on resource-limited devices. |

AUC: 0.649 (LaSOT) |

| STARK [13] |

Transformer |

Encoder–decoder Transformer |

Models temporal dependencies explicitly with spatio-temporal attention; stable under jitter, occlusion, and appearance changes; strong bounding box regression accuracy. |

Memory- and compute-intensive; performance sensitive to sequence design; not suitable for lightweight or mobile scenarios. |

AUC: 0.678 (LaSOT) |

| ToMP [14] |

Transformer |

Transformer + predictor |

Performs dense feature matching with strong robustness to appearance changes; eliminates need for frequent online updates; flexible prediction capability. |

Dense patch-token representation increases latency; higher complexity hinders real-time performance; resource-demanding for large-scale deployment. |

AUC: 0.70 (TrackingNet) |

| TLD [20] |

Hybrid |

Optical flow + detector |

First to propose tracking–learning–detection loop; global re-detection enables recovery from failures; adaptive appearance models for long-term use. |

Online updates prone to drift; handcrafted features limit robustness; unstable in rapidly changing or dynamic scenes. |

AUC: 0.53 (OTB100) |

| ATOM [15] |

Hybrid |

ResNet + regressor head |

Accurate bounding box estimation via dedicated regression head; robust under challenging appearance changes; strong baseline for hybrid trackers. |

Requires per-sequence optimization online; prevents real-time deployment; increased latency compared to lightweight models. |

AUC: 0.669 (LaSOT) |

| DiMP [16] |

Hybrid |

ResNet + meta-learner |

Discriminative classification combined with meta-learned updates; adapts quickly to new targets; competitive accuracy on long sequences. |

Still requires online optimization; additional training complexity; slower compared to pure Siamese architectures. |

AUC: 0.678 (LaSOT) |

| SiamRCNN [17] |

Hybrid |

Siamese backbone + R-CNN |

Achieves high accuracy under challenging conditions; integrates detection for robust target estimation; flexible handling of aspect ratio and scale. |

Computationally heavy two-stage design; significantly slower inference; complex pipeline compared to single-stage trackers. |

AUC: 0.64 (LaSOT) |

| SiamBAN [18] |

Hybrid |

Siamese + unified head |

Anchor-free classification and regression head improves flexibility; balanced trade-off between accuracy and efficiency; robust across diverse conditions. |

Still limited by fixed template; lacks strong recovery under long occlusion; less competitive for long-term tracking. |

AUC: 0.63 (LaSOT) |

| MixFormer [19] |

Hybrid |

Transformer encoder + joint head |

Unified CNN+Transformer architecture with fewer parameters; competitive performance across datasets; strong robustness to appearance variation. |

Requires extensive pretraining to achieve best performance; heavier than lightweight Siamese designs; reduced efficiency in embedded scenarios. |

AUC: 0.704 (LaSOT) |

5. Multi-Object Tracking (MOT)

Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) focuses on the task of simultaneously localizing and maintaining consistent identities for multiple objects across video frames [

21]. Formally, given a set of object detections at each time step

, the goal is to estimate a set of trajectories

such that each trajectory

corresponds to the same real-world object.

A key challenge in MOT is the

data association problem - correctly linking detections across frames despite occlusions, abrupt motion, camera shifts, and the presence of visually similar objects. Modern MOT systems often adopt a tracking-by-detection paradigm [

22], which separates object detection and temporal association into modular stages. Although this pipeline simplifies learning and improves flexibility, it may suffer from detector errors and delayed identity recovery after occlusion.

Over the past decade, MOT research has shifted from classical filtering and matching algorithms to deep learning-based approaches that integrate appearance models, motion prediction, and re-identification features. Public benchmarks such as MOT17 [

23] and DanceTrack [

24] have driven progress, enabling fair comparison across identity preservation, detection recall, and trajectory fragmentation.

Despite progress, MOT remains a fundamentally ambiguous problem in crowded scenes and long-term tracking due to ID switches, partial occlusions, and class-agnostic interactions. This has motivated ongoing research into joint detection-tracking models, temporal attention mechanisms, and multi-modal inputs such as LiDAR and radar in autonomous driving.

5.1. Detection-Guided Association Models

Detection-guided tracking frameworks follow a decoupled pipeline wherein objects are first detected in each frame and then associated across time to form trajectories. This paradigm remains dominant due to its modularity and ability to leverage advances in object detection. Formally, let

be the set of detections at frame

t, and

be the set of active tracks. The goal is to associate

to

via an assignment matrix

A minimizing total cost:

where the cost integrates appearance, motion (e.g., Kalman prediction), and geometric similarity. The design choice of how to compute this cost has led to several families of approaches.

5.1.1. SORT Extensions: From Motion-Only to ReID-Aware

Early MOT systems such as SORT relied purely on motion cues and Kalman filtering, yielding efficiency but poor identity consistency. DeepSORT [

25] extended this baseline by adding deep appearance embeddings trained for person re-identification (ReID), significantly reducing ID switches. StrongSORT [

26] further incorporated Kalman updates and outlier suppression, showing how stabilizing identity propagation improves robustness in noisy scenes. Introducing ReID embeddings transformed MOT from motion-driven matching into a vision-guided task, improving occlusion handling at the cost of higher compute.

5.1.2. Detector-Driven Propagation

Instead of explicit association, some methods reuse the detector itself to propagate trajectories. Tracktor++ [

27] leverages the regression head of the detector to move bounding boxes across frames, using classification scores to terminate occluded tracks. Detector-driven propagation simplifies the pipeline but is limited by the detector’s recall and struggles under long occlusion or multi-class tracking.

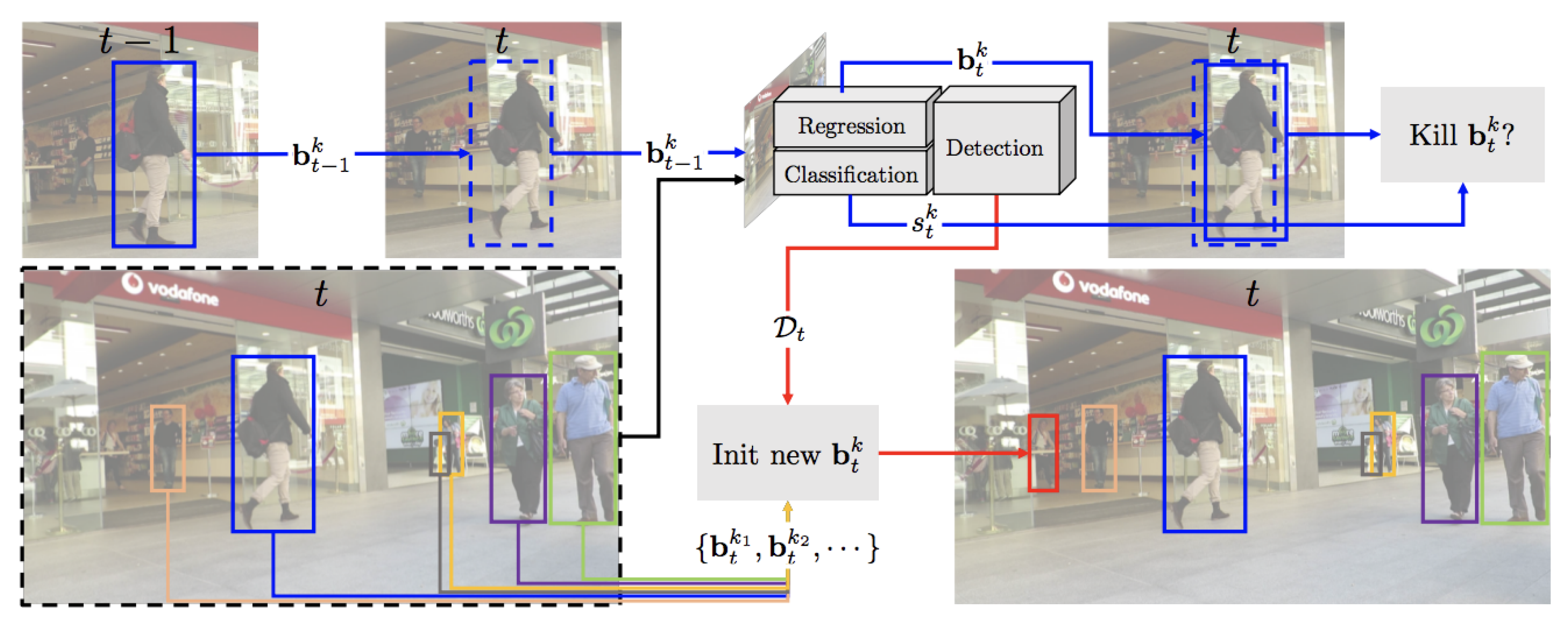

Figure 2.

Overview of the Tracktor pipeline for multi-object tracking [

27]. Regression aligns bounding boxes from frame

to

t, while classification scores determine termination. New detections are introduced when overlaps are low.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Tracktor pipeline for multi-object tracking [

27]. Regression aligns bounding boxes from frame

to

t, while classification scores determine termination. New detections are introduced when overlaps are low.

5.1.3. Recall-Boosting Trackers

Another line of work focuses on reducing false negatives by leveraging low-confidence detections. ByteTrack [

28] retains these candidates and applies a two-stage association, improving robustness in crowded scenes. MR2-ByteTrack [

29] adapts this principle for embedded platforms using resolution-aware matching to preserve accuracy under resource constraints.Recall-boosting methods highlight the precision–recall trade-off, demonstrating that retaining noisy detections can improve identity stability if handled with careful association.

5.1.4. Confidence-Aware Association

LG-Track [

30] distinguishes between classification and localization confidence, improving association by retaining well-localized but low-score detections. Deep LG-Track [

31] enhances this approach with adaptive Kalman filtering and confidence-aware embedding updates, reducing ID switches in occlusion-heavy scenarios.Decoupling localization from classification confidence provides a more nuanced reliability signal for robust identity matching.

5.1.5. Graph-Based and Group-Aware Association

Recent methods leverage graph structures for long-range temporal reasoning. RTAT [

32] introduces a two-stage association with a graph neural network that refines tracklets via message passing. Similarly, Wang et al. [

33] cluster object candidates with similar motion patterns into groups before applying bipartite association, enforcing local consistency.Graph-based association represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond pairwise similarity toward structured reasoning over sets of detections and tracklets.

5.2. Detection-Integrated Tracking Models

End-to-end integrated architectures aim to unify detection and association in a single network, reducing the error compounding that occurs in modular pipelines and enabling shared representations across tasks. Given a frame sequence

, a network

directly predicts detections and identities at each timestep:

where

is the number of detected objects in frame

t. Current work in this area can be grouped into several design paradigms.

5.2.1. Dual-head networks

FairMOT [

34] employs a shared backbone with two parallel heads, one for object localization and the other for appearance embeddings. This balances the two objectives and avoids the trade-offs often observed in cascaded pipelines. Speed-FairMOT [

35] modifies the backbone with lightweight components such as ShuffleNetV2 and adaptive feature fusion, achieving approximately 40% higher throughput while retaining competitive accuracy. These dual-head models illustrate how detection and identity features can coexist in the same representation space to improve both efficiency and robustness.

5.2.2. Query-modular designs

TBDQ-Net [

36] separates detection and association into distinct components, freezing a strong detector while training a lightweight association module. The query mechanism integrates content–position alignment and interaction blocks to maintain identity consistency. This modular structure shows how trackers can inherit improvements from new detectors while learning only the association step, lowering training costs.

5.2.3. Higher-order graph formulations

JDTHM [

37] integrates detection and tracking through hypergraph matching. Rather than pairwise association, the model optimizes over higher-order relations, learning hyperedges that capture interactions among multiple detections and tracklets simultaneously. This shift toward structured reasoning helps improve identity preservation in dense or crowded scenes.

5.2.4. Keypoint-driven propagation

CenterTrack [

38] extends CenterNet to predict object centers, motion offsets, and bounding boxes jointly. Identities are implicitly propagated through continuity of centers:

where

encodes motion offsets relative to prior locations. This approach reduces the reliance on appearance embeddings and enables real-time inference, though it degrades in heavily occluded scenarios where spatial continuity is disrupted.

5.2.5. Quasi-dense association

QDTrack [

39] learns identity-aware embeddings by exploiting quasi-dense matching between temporally adjacent frames. The training signal is amplified by using abundant frame pairs, reducing reliance on manual identity labels and external ReID modules. Although computationally heavier at inference due to dense matching, the method is particularly effective in scenes with frequent occlusion and visual ambiguity.

Detection-integrated approaches illustrate a spectrum of designs: dual-head networks that balance detection and identity cues, modular systems that decouple detection from association, hypergraph-based methods that encode higher-order relations, keypoint-centered frameworks that propagate identity through spatial continuity, and quasi-dense association that leverages large amounts of unlabeled data. Collectively, they demonstrate how moving beyond modular pipelines allows richer identity modeling, though trade-offs remain between computational efficiency and long-term identity robustness.

5.3. Transformer-Based MOT Architectures

Transformer-based models have emerged as powerful tools for Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) by treating the problem as sequence modeling with queries and attention. This shift eliminates the need for hand-crafted affinity measures, allowing joint optimization of detection and identity association in an end-to-end framework. The core idea is that attention mechanisms can retain identity information across time, improving robustness in complex and crowded scenes. Current approaches can be organized into four main categories.

5.3.1. Query-based frameworks

TrackFormer [

40] proposes a unified query-driven architecture where detection queries are used to discover new objects and track queries maintain identities across frames. By reusing track queries from frame

as input to frame

t, the model retains identity continuity without motion models or handcrafted associations. This autoregressive mechanism has shown strong performance on benchmarks such as MOT17 and MOT20, demonstrating that query propagation enables stable long-term identity retention.

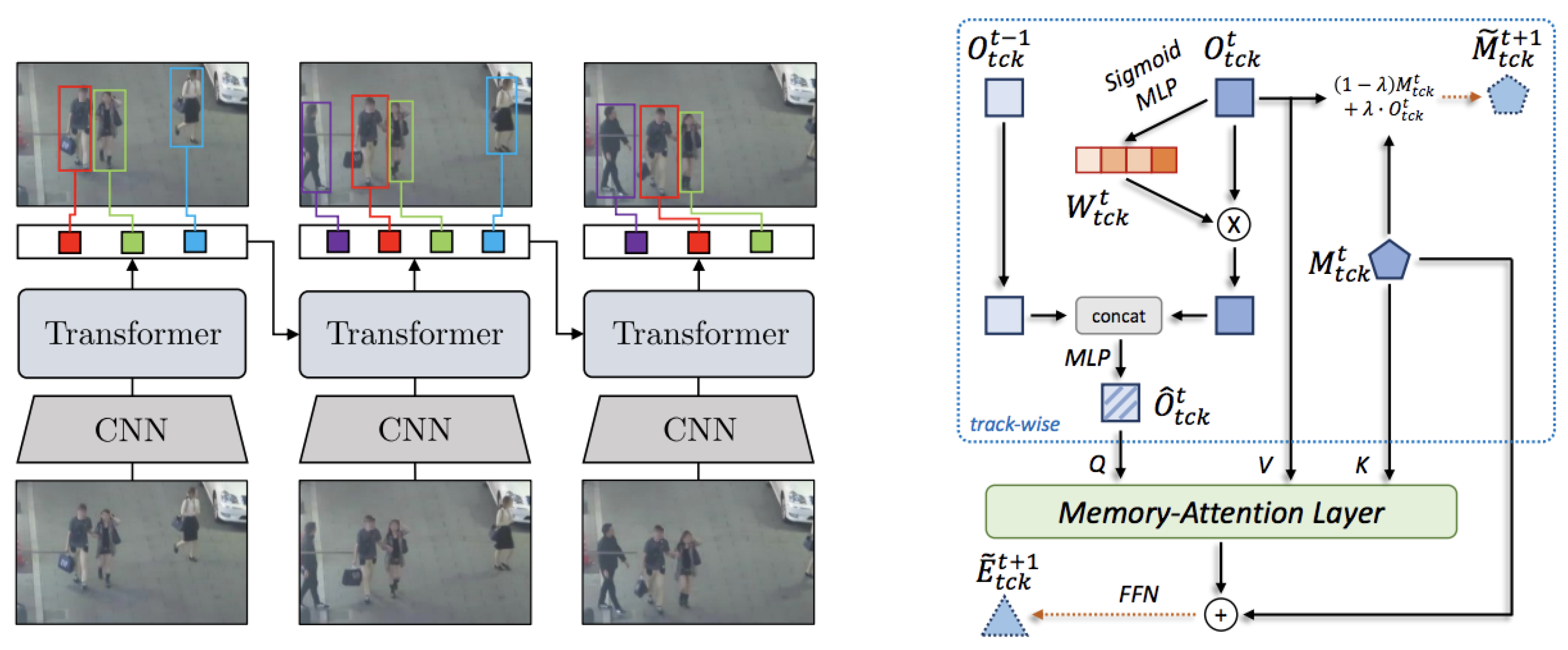

Figure 3.

(Left) TrackFormer [

41] introduces autoregressive queries to model detection and identity jointly. (Right) The Temporal Interaction Module in MeMOTR [

42], which uses memory-based attention and gated updates for long-term identity propagation.

Figure 3.

(Left) TrackFormer [

41] introduces autoregressive queries to model detection and identity jointly. (Right) The Temporal Interaction Module in MeMOTR [

42], which uses memory-based attention and gated updates for long-term identity propagation.

5.3.2. Cross-frame aligned attention

TransTrack [

43] aligns object features from the previous frame to guide association in the current frame, injecting appearance and motion priors into query embeddings. ABQ-Track [

44] extends this idea by introducing anchor-based queries that encode object positions directly, improving spatial alignment and reducing ID switches. While this enhances identity consistency in cluttered scenes, reliance on anchors can add rigidity and limit flexibility in dynamic environments.

5.3.3. Memory-augmented models

MeMOTR [

45] incorporates a memory bank that stores historical features and combines them with the current frame’s encoded representations. Queries are updated by attending to both recent and stored features:

This design improves long-range tracking and facilitates recovery after occlusion, particularly effective in datasets like DanceTrack where identities frequently disappear and reappear. By explicitly modeling temporal continuity through memory, these methods capture richer spatiotemporal dependencies.

5.3.4. Conflict-resolution attention

Recent work has explored replacing classical matching mechanisms with fully learnable attention. Co-MOT [

46] trains with a coopetition-aware query strategy that balances object discovery with identity consistency, while TADN [

47] removes Hungarian matching in favor of a transformer-based assignment decoder. These models show that conflict resolution in data association can be learned directly, offering more flexibility than fixed optimization heuristics.

Transformer-based MOT represents a paradigm shift: query propagation enables stable identity retention, spatially aligned attention improves consistency, memory augmentation provides robustness under occlusion, and learnable conflict resolution replaces rigid matching algorithms. Collectively, these advances highlight how attention-based sequence modeling is reshaping multi-object tracking.

5.4. Multi-Modal and 3D Multi-Object Tracking

While traditional Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) systems typically rely on RGB imagery, many real-world applications—such as autonomous driving, robotics, and surveillance—demand robustness to occlusion, clutter, and long-range perception. To meet these requirements, modern approaches increasingly incorporate depth sensors, LiDAR, radar, and inertial measurements. Multi-modal inputs provide complementary cues that enhance localization accuracy and improve identity association under challenging conditions. Three main families of approaches can be distinguished.

5.4.1. RGB-D tracking

Depth information supplies geometric cues that support scale estimation and foreground–background separation. Early RGB-D trackers such as DS-KCF [

48] and OTR [

49] integrated color and depth channels in correlation filters to adapt templates dynamically and suppress distractors. These classical methods, however, suffered when depth data was sparse or noisy in outdoor settings. More recent deep RGB-D approaches [

50] adopt gated attention and confidence-aware fusion to combine modalities more effectively:

where

and

represent RGB and depth frames. By learning the reliability of depth cues spatially, these networks improve accuracy, though challenges remain in calibration, real-time speed, and generalization beyond controlled environments.

5.4.2. LiDAR-based 3D MOT

LiDAR sensors yield 3D point clouds that capture structure with high spatial accuracy but little appearance detail. Tracking in this setting involves associating objects directly in world coordinates, often through Bird’s Eye View (BEV) representations. AB3DMOT [

51] combines Kalman filtering with 3D IoU constraints to match bounding boxes across frames. More advanced methods such as CenterPoint [

52] incorporate velocity priors to improve continuity, while transformer-based UVTR-MOT [

53] encodes spatiotemporal dependencies via voxelized representations. These methods achieve strong results on large-scale datasets like nuScenes [

54] and Waymo [

55], but the computational burden and sensitivity to sparse points in distant regions remain open issues.

5.4.3. Cross-sensor fusion

Sensor fusion strategies aim to combine the strengths of different modalities: RGB contributes appearance, LiDAR provides geometry, radar captures velocity, and IMU aids in ego-motion compensation. Fusion can occur at multiple levels:

Early fusion: Raw sensor data is concatenated prior to feature extraction [

56], though misalignments can degrade results.

Late fusion: Predictions from individual modalities are merged [

57], which is flexible but prevents deep cross-modal reasoning.

Deep fusion: Learned attention modules integrate features at intermediate layers [

58], capturing cross-modal correlations:

Recent work has explored self-supervised fusion [

59], enforcing consistency without requiring exhaustive labels. Despite progress, synchronization across sensors, heterogeneous resolution, and calibration drift continue to pose significant deployment challenges.

Multi-modal and 3D MOT has expanded tracking beyond RGB video, introducing depth for scale, LiDAR for structure, radar for motion, and IMU for stability. While RGB-D models address indoor ambiguity, LiDAR-based approaches dominate autonomous driving benchmarks, and cross-sensor fusion explores how to combine complementary cues effectively. The main trade-off lies between richer sensing and the practical constraints of synchronization, computation, and scalability.

Table 2.

Multi -Object Tracking (MOT) methods categorized by architecture, backbone, strengths, weaknesses, and performance (dataset + metric). Performance column shows metric along with the dataset it was reported on.

Table 2.

Multi -Object Tracking (MOT) methods categorized by architecture, backbone, strengths, weaknesses, and performance (dataset + metric). Performance column shows metric along with the dataset it was reported on.

| Method |

Category |

Backbone |

Key Strength |

Key Weakness |

Performance (Dataset/Metric) |

| DeepSORT [25] |

Detection-Guided |

CNN ReID + Kalman |

Handles occlusion by integrating appearance features with motion; modular and easy to integrate into existing detectors; widely used baseline for MOT pipelines. |

Relies heavily on detector quality; identity switches when embeddings drift; weak under scale variation and crowded scenes. |

MOTA: 61.4 (MOT17) |

| StrongSORT [26] |

Detection-Guided |

Kalman + suppression + CNN ReID |

Enhances DeepSORT with outlier suppression; improves ID stability in cluttered environments; handles partial occlusion better; open-source and fast in practice. |

Still experiences residual ID switches in heavy occlusion; sensitive to noisy embeddings; performance tied to detector backbone. |

IDF1: 72.5 (MOT17) |

| Tracktor++ [27] |

Detection-Guided |

Detector regression head |

Simple and efficient design; reuses detector regression to propagate boxes; avoids explicit association; competitive with minimal engineering. |

Limited by detector recall; weak under occlusion and motion blur; less effective for multi-class tracking. |

MOTA: 53.5 (MOT17) |

| ByteTrack [28] |

Detection-Guided |

Association + simple motion |

Strong recall by keeping low-confidence detections; robust in crowded scenes; balances precision and recall effectively; competitive real-time speed. |

Does not leverage embeddings; prone to ID drift under occlusion; struggles with long-term re-identification. |

HOTA: 63.1 (MOT20) |

| MR2-ByteTrack [29] |

Detection-Guided |

Resolution-aware association stack |

Lightweight and embedded-friendly; resilient under low-resolution and noisy detections; stable on edge devices with limited resources. |

Accuracy drops significantly during long occlusions; limited generalization across diverse benchmarks. |

MOTA: 60.2 (MOT20) |

| LG-Track [30] |

Detection-Guided |

Local-Global Association + CNN ReID |

Combines local motion with global context; reduces ID switches by balancing short-term and long-term cues; lightweight design with solid accuracy. |

Struggles under dense occlusion; performance sensitive to hyperparameter tuning; still tied to detector quality. |

MOTA: 66.2 (MOT17) |

| Deep LG-Track [31] |

Detection-Guided |

Deep Local-Global Features + Kalman |

Extends LG-Track with deep hierarchical features; handles long-term occlusion better; improved embedding robustness; achieves state-of-the-art stability. |

Computationally heavier than LG-Track; requires careful training data; scalability limited in real-time scenarios. |

IDF1: 74.1 (MOT20) |

| RTAT [32] |

Detection-Guided |

Two-Stage Association (Motion + ReID) |

Robust two-stage association that first filters candidates by motion, then refines with appearance; improves robustness under occlusion and noisy detections. |

Extra association stage increases latency; dependent on motion modeling assumptions; weaker in long occlusions. |

MOTA: 69.8 (MOT17) |

| Wu et al. [33] |

Detection-Guided |

Graph Matching + Appearance Embeddings |

Uses graph-based association for global consistency; better at maintaining IDs across fragmented detections; reduces error accumulation. |

Sensitive to graph construction errors; scalability issues on large scenes; requires strong embeddings. |

IDF1: 70.6 (MOT17) |

| FairMOT [34] |

Detection-Integrated |

Shared CNN with detection + ReID heads |

Jointly optimizes detection and embeddings; avoids trade-offs between cascaded pipelines; balanced accuracy and efficiency; strong ID preservation. |

Moderate speed compared to pure detection trackers; performance depends on backbone choice; less optimized for real-time on constrained hardware. |

IDF1: 72.3 (MOT17) |

| CenterTrack [38] |

Detection-Integrated |

CenterNet + motion offset head |

Real-time tracking via center-based detection; simple online association; effective balance of accuracy and efficiency. |

No explicit appearance model; fragile identity handling under occlusion; weak at long-term re-identification. |

MOTA: 67.8 (MOT17) |

| QDTrack [39] |

Detection-Integrated |

CNN with quasi-dense matching |

Quasi-dense similarity supervision improves embeddings; learns ReID signals without explicit labels; robust local feature matching. |

High computational demand; identity drift under prolonged clutter; scalability issues for large benchmarks. |

IDF1: 71.1 (MOT17) |

| Speed-FairMOT [35] |

Detection-Integrated |

Lightweight CNN + Joint Detection-Tracking |

Optimized for speed with reduced backbone; achieves real-time performance on edge devices; preserves FairMOT joint detection-tracking design. |

Sacrifices accuracy for speed; limited robustness in crowded or complex scenes; weaker embeddings. |

FPS: 45, MOTA: 59.7 (MOT17) |

| TBDQ-Net [36] |

Detection-Integrated |

Transformer + Query Matching |

Efficient query-based detection-tracking framework; reduces redundant computations; competitive accuracy with better speed-accuracy tradeoff. |

Query design limits scalability; harder to adapt to unseen objects; performance tied to transformer efficiency. |

MOTA: 68.3 (MOT20) |

| JDTHM [37] |

Detection-Integrated |

Joint Detection-Tracking Heatmap |

Uses joint heatmap representation for detection and tracking; improves spatial consistency and reduces ID switches; efficient training pipeline. |

Limited generalization to non-standard scenes; struggles in low-resolution inputs; identity drift under long occlusion. |

IDF1: 71.2 (MOT17) |

| TrackFormer [40] |

Transformer |

Transformer encoder–decoder |

End-to-end query-based detection and tracking; propagates identity with track queries; avoids handcrafted association modules. |

Slower inference than modular methods; heavy GPU demand; sensitive to hyperparameters. |

HOTA: 58.4 (MOT17) |

| TransTrack [43] |

Transformer |

Transformer with cross-frame attention |

Cross-frame aligned attention improves spatial consistency; effective for short-term identity preservation; integrates detection and tracking. |

ID persistence weak under long occlusion; requires careful initialization; heavier than CNN-based trackers. |

IDF1: 60.9 (MOT17) |

| ABQ-Track [44] |

Transformer |

Transformer with anchor queries |

Encodes positional priors via anchor queries; reduces ID switches in crowded environments; competitive accuracy with fewer parameters. |

Anchor design adds rigidity; reduced generalization across datasets; not robust to unseen layouts. |

HOTA: 61.7 (MOT20) |

| MeMOTR [45] |

Transformer-Based |

Memory-Augmented Transformer |

Integrates long-term memory into transformer decoder; robust under long occlusion; captures contextual dependencies over frames. |

Computationally heavy; memory module increases complexity; requires large-scale training data. |

MOTA: 70.9 (MOT20) |

| Co-MOT [46] |

Transformer-Based |

Cooperative Transformer + ReID |

Uses cooperative transformer layers to share context among objects; excels in crowded scenes; strong re-identification accuracy. |

High GPU demand; longer inference time; requires careful parameter balancing. |

IDF1: 76.4 (MOT20) |

5.5. ReID-Aware Models

Re-identification (ReID)-aware models improve identity consistency in Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) by learning discriminative appearance embeddings. These embeddings are particularly valuable in scenarios with heavy occlusion, re-entry after disappearance, or high visual similarity where motion-based association alone is unreliable. Training typically employs metric learning objectives such as the triplet loss:

where

denote the embeddings for anchor, positive, and negative instances, and

is a margin parameter. Several representative approaches illustrate the evolution of ReID in MOT.

5.5.1. Quasi-dense similarity learning

QDTrack [?] introduces quasi-dense matching across spatially and temporally adjacent frames. By constructing soft association labels through spatial–temporal consistency, it regularizes embedding distributions and enhances robustness to appearance ambiguity. This strategy significantly improves tracking performance in crowded environments such as DanceTrack and MOT17, where occlusion is frequent. Quasi-dense supervision illustrates how abundant unlabeled frame pairs can strengthen embedding learning without requiring external ReID datasets.

5.5.2. Joint detection and embedding

JDE [

60] unifies detection and ReID extraction within a single convolutional backbone. Unlike two-stage pipelines that train a detector and a separate ReID model, JDE optimizes both tasks end-to-end. This reduces inference latency while maintaining strong identity preservation under occlusion and motion blur. The design highlights how shared features across detection and embedding can balance efficiency with identity robustness, especially in real-time scenarios.

5.5.3. Transformer-based re-identification

TransReID [

61] adopts a Transformer backbone for ReID, addressing viewpoint variation and domain shift. It introduces a camera-aware position embedding (CAPE) to encode cross-camera context and a jigsaw patch module that enhances spatial invariance. By leveraging self-attention, TransReID captures long-range dependencies and fine-grained part alignment beyond convolutional limits. Although originally designed for person re-identification benchmarks such as Market-1501, DukeMTMC-ReID, and MSMT17, these advances also benefit MOT by strengthening embedding robustness across diverse environments.

ReID-aware models strengthen MOT systems by focusing on appearance cues that persist through occlusion, re-entry, and motion blur. Quasi-dense similarity learning leverages frame-level abundance, joint detection–embedding architectures reduce latency by sharing backbones, and Transformer-based approaches achieve fine-grained, domain-robust embeddings. Together, they highlight how re-identification has evolved from a supporting module into a central component of modern tracking pipelines.

Table 2 summarizes prominent Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) models, detailing their architectural categories, backbone designs, major strengths, limitations, and benchmark performance across standard datasets.

Table 3.

MultiModal/3D and ReID Aware Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) methods categorized by architecture, backbone, strengths, weaknesses, and performance (dataset + metric). Performance column shows metric along with the dataset it was reported on.

Table 3.

MultiModal/3D and ReID Aware Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) methods categorized by architecture, backbone, strengths, weaknesses, and performance (dataset + metric). Performance column shows metric along with the dataset it was reported on.

| Method |

Category |

Backbone |

Key Strength |

Key Weakness |

Performance (Dataset/Metric) |

| RGB–D Tracking [50] |

Multi-Modal / 3D |

Dual encoders + attention fusion |

Depth cues improve occlusion handling and scale estimation; foreground/background separation; enhanced robustness in indoor scenarios. |

Depth noise or missing data outdoors reduces reliability; sensor calibration errors degrade performance. |

MOTA: 46.2 (RGBD-Tracking) |

| CS Fusion [58] |

Multi-Modal / 3D |

RGB + LiDAR + Radar + IMU stack |

Cross-sensor fusion complements appearance, geometry, and velocity cues; robust under weather and illumination challenges; improves generalization. |

Sensitive to sensor synchronization and calibration; computationally expensive; deployment complexity in real-world setups. |

AMOTA: 56.3 (nuScenes) |

| DS-KCF [48] |

Multi-Modal/3D |

Depth-aware Correlation Filter |

Early depth-aware tracker; combines RGB and depth cues; robust against background clutter and partial occlusion. |

Limited scalability to large datasets; handcrafted correlation filters less robust than deep features. |

Success Rate: 72.1 (RGB-D benchmark) |

| OTR [49] |

Multi-Modal/3D |

RGB-D Correlation Filter + ReID |

Exploits both depth and appearance; improved occlusion handling in RGB-D scenes; maintains IDs across viewpoint changes. |

Depth sensor noise affects accuracy; limited to RGB-D applications; heavier computation than 2D trackers. |

Precision: 74.5 (RGB-D benchmarks) |

| DPANet [50] |

Multi-Modal/3D |

Dual Path Attention Network |

Fuses RGB and depth with attention mechanisms; adaptive weighting improves robustness; handles occlusion well. |

Needs high-quality depth input; expensive feature fusion; generalization limited to RGB-D datasets. |

MOTA: 62.3 (MOT-RGBD) |

| AB3DMOT [51] |

Multi-Modal/3D |

Kalman + 3D Bounding Box Association |

Widely used 3D MOT baseline; fast and simple; effective for LiDAR-based tracking in autonomous driving. |

Limited by detection quality; struggles in long occlusion; ignores appearance cues. |

AMOTA: 67.5 (KITTI) |

| CenterPoint [52] |

Multi-Modal/3D |

Center-Based 3D Detection + Tracking |

Center-based pipeline for LiDAR; accurate and efficient; strong baseline for 3D MOT in autonomous driving. |

Requires high-quality LiDAR; misses small/occluded objects; limited in multi-modal fusion. |

AMOTA: 78.1 (nuScenes) |

| JDE [60] |

ReID-Aware |

CNN detector + embedding head |

Unified backbone for joint detection and embedding; reduced inference latency; optimized for real-time applications. |

Embeddings weaker than specialized ReID models; suffers under heavy occlusion; trade-off between detection and ReID accuracy. |

MOTA: 64.4 (MOT16) |

| TransReID [61] |

ReID-Aware |

Transformer with CAPE |

Captures long-range dependencies; part-aware embedding improves viewpoint robustness; strong results across cameras. |

High computational cost; domain-shift sensitivity; needs large-scale pretraining for stability. |

IDF1: 78.0 (Market-1501) |

6. Long-Term Tracking (LTT)

Long-term tracking (LTT) extends conventional short-term paradigms by addressing prolonged occlusion, target disappearance and reappearance, and appearance drift. Unlike standard trackers that assume continuous visibility, LTT systems must detect target loss, re-localize objects after long gaps, and maintain consistent identity over extended sequences. Research in this area has progressed from modular pipelines with handcrafted features to re-detection modules, memory-enhanced architectures, and modern state-space approaches.

6.0.1. Early modular frameworks

The Tracking-Learning-Detection (TLD) framework [

20] was one of the first to formalize long-term tracking. It combined short-term prediction, an online detector, and a learning module that updated incrementally using high-confidence results. While pioneering in separating tracking, validation, and adaptation, its reliance on handcrafted features limited robustness under complex motion, background clutter, and large appearance changes.

6.0.2. Siamese re-detection models

The rise of Siamese architectures led to several influential long-term trackers. DaSiamRPN [

62] extends SiamRPN with a distractor-aware module and a re-detection branch that activates when confidence drops. By incorporating global search and embeddings tuned for distractor suppression, the tracker achieves reliable recovery in cluttered or reappearance-heavy sequences. SiamRPN++ [

9] further improves localization with deeper backbones and widened receptive fields. In its long-term variant, global template matching is triggered upon low-confidence predictions to recover lost targets, though the absence of adaptive memory makes it prone to appearance drift.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the Distractor-Aware Siamese Region Proposal Networks (DaSiamRPN). Compared to a general Siamese tracker, DaSiamRPN leverages both target and background information to suppress distractor influence during tracking, resulting in improved robustness [

62].

Figure 4.

Illustration of the Distractor-Aware Siamese Region Proposal Networks (DaSiamRPN). Compared to a general Siamese tracker, DaSiamRPN leverages both target and background information to suppress distractor influence during tracking, resulting in improved robustness [

62].

6.0.3. Occlusion-aware re-matching

LTTrack [

63] addresses long-term failure by combining short-term association with an occlusion-aware re-matching mechanism. Lost tracks are stored in a suspended “zombie pool,” and reactivation occurs when new detections align with stored trajectories based on bounding box overlap and motion consistency:

where

denotes predicted positions and

d is a gating threshold. This hybrid strategy improves continuity in crowded or dynamic scenes by enabling robust recovery from missed detections and prolonged occlusion.

6.0.4. Memory-augmented approaches

MambaLCT [

64] introduces a state-space model that compresses and encodes long-term context. By aggregating temporal information without excessive computation, it sustains identity preservation during lengthy disconnections. Such memory-based designs represent a shift toward scalable architectures that balance long-term reasoning with real-time feasibility.

Long-term tracking has evolved from modular pipelines like TLD to Siamese re-detection models, occlusion-aware re-matching mechanisms, and memory-enhanced architectures. Each design highlights a trade-off: modular systems pioneered problem decomposition but lacked robustness, Siamese-based trackers introduced efficient re-detection yet remained sensitive to drift, re-matching approaches strengthened occlusion handling, and state-space memory models point toward efficient long-horizon reasoning. Together, these contributions underline how LTT has become central to applications requiring sustained identity preservation in dynamic, unconstrained environments.

7. Emerging Trends: Vision-Language and Foundation Model-Based Tracking

7.1. Unified Taxonomy of Tracking Paradigms

We propose a refined taxonomy of recent tracking models that emphasizes the pretraining paradigm—including supervised, self-supervised, foundation-model-adapted, and multimodal approaches—rather than purely architectural distinctions. This reflects the growing influence of foundation models and their integration into tracking pipelines.

7.1.1. Supervised Trackers

Supervised trackers are trained on fully annotated video datasets using explicit supervision in the form of object category labels and bounding boxes across frames. The training objective typically combines classification and regression losses to jointly localize and identify the target object. The total loss is often formulated as:

where

is a cross-entropy or focal loss over predicted class labels

, and

is a localization loss such as IoU, GIoU [

65], or CIoU [

66] between predicted boxes

and ground-truth boxes

b.

Classical models like SiamRPN++ [

9] extend the Siamese tracking paradigm using deep ResNet features and anchor-based classification. STARK [

13], on the other hand, introduces a Transformer-based encoder-decoder design that predicts object trajectories using spatial-temporal attention, achieving strong results on LaSOT and GOT-10k benchmarks. KeepTrack [

67] enhances target re-identification by incorporating a learned external memory that captures long-term appearance variations. DeAOT [

68] further pushes the envelope by adopting dual-path attention and adaptive object templates, offering strong generalization in segment tracking and multiple object settings.

Despite strong benchmark performance, supervised trackers are often constrained by their dependence on labeled data and limited adaptability to out-of-distribution settings. They tend to overfit to frequent object categories and exhibit poor generalization when transferred to new domains or modalities without fine-tuning.

7.1.2. Self-Supervised Trackers

Self-supervised trackers leverage unlabeled data and pretext tasks to learn visual representations that generalize well to tracking scenarios without requiring human annotations. These methods design proxy objectives aligned with tracking-relevant signals such as temporal continuity, spatial consistency, and appearance invariance.

SimTrack [

69] extends SimCLR-style contrastive learning to tracking by aligning positive frame pairs and learning object-centric embeddings using the InfoNCE loss:

where

and

are feature embeddings from the same object across frames, and

is a temperature hyperparameter controlling concentration. DINOTrack [

70] adapts the self-distillation framework of DINO [

71] by training a student-teacher model on patch-level embeddings that are temporally stable, enabling object localization and transfer to long-term tracking datasets like TREK-150 and EgoTracks. TLPFormer [

72] proposes a temporally masked token prediction task where randomly dropped frames force the model to interpolate features across time, improving performance under occlusion and abrupt motion. ProTrack [

73] incorporates motion flow estimates into its contrastive learning objective, ensuring consistency of identity embeddings across deformation and jitter, especially in mobile and egocentric scenarios.

These self-supervised methods increasingly serve as robust initialization backbones for downstream fine-tuning, and their scalability on large-scale unlabeled video corpora makes them particularly compatible with foundation model development.

7.1.3. Foundation-Adapted Trackers

Foundation-adapted trackers repurpose large pretrained vision or vision-language models—such as CLIP [

74], DINOv2 [

75], or SAM [

76]—for tracking by adapting their frozen or partially fine-tuned representations to localization and identification tasks. These models are trained on massive datasets with weak supervision, enabling strong zero-shot or few-shot generalization.

The core strategy is to reuse the powerful embedding space

learned by foundation models, and formulate tracking as a similarity matching or mask-guided localization problem. A generic form of the tracking objective is:

where

is the current frame,

is the initial template, and

enforces spatial alignment through bounding box or segmentation mask supervision.

Prominent examples include OSTrack [

77], which reuses the early stages of a pretrained backbone and adds lightweight attention heads for temporal modeling. DeAOT [

68] adapts dual-path attention over frozen foundation features for video object segmentation and achieves state-of-the-art on DAVIS benchmarks. PromptTrack [

78] introduces lightweight prompts to adapt frozen CLIP features for instance-level tracking. EfficientTAM [

79] combines ViT-based tracking heads with prompt-denoised masks from SAM to achieve high-speed tracking with minimal fine-tuning.

While foundation-adapted models demonstrate excellent cross-domain robustness and sample efficiency, they face challenges in fine-grained identity tracking, dynamic scenes, and temporal consistency. Additionally, inference cost remains a concern due to the large backbone sizes and transformer depth. Ongoing work explores efficient adapters, sparse prompting, and retrieval-augmented inference to mitigate these limitations [

80].

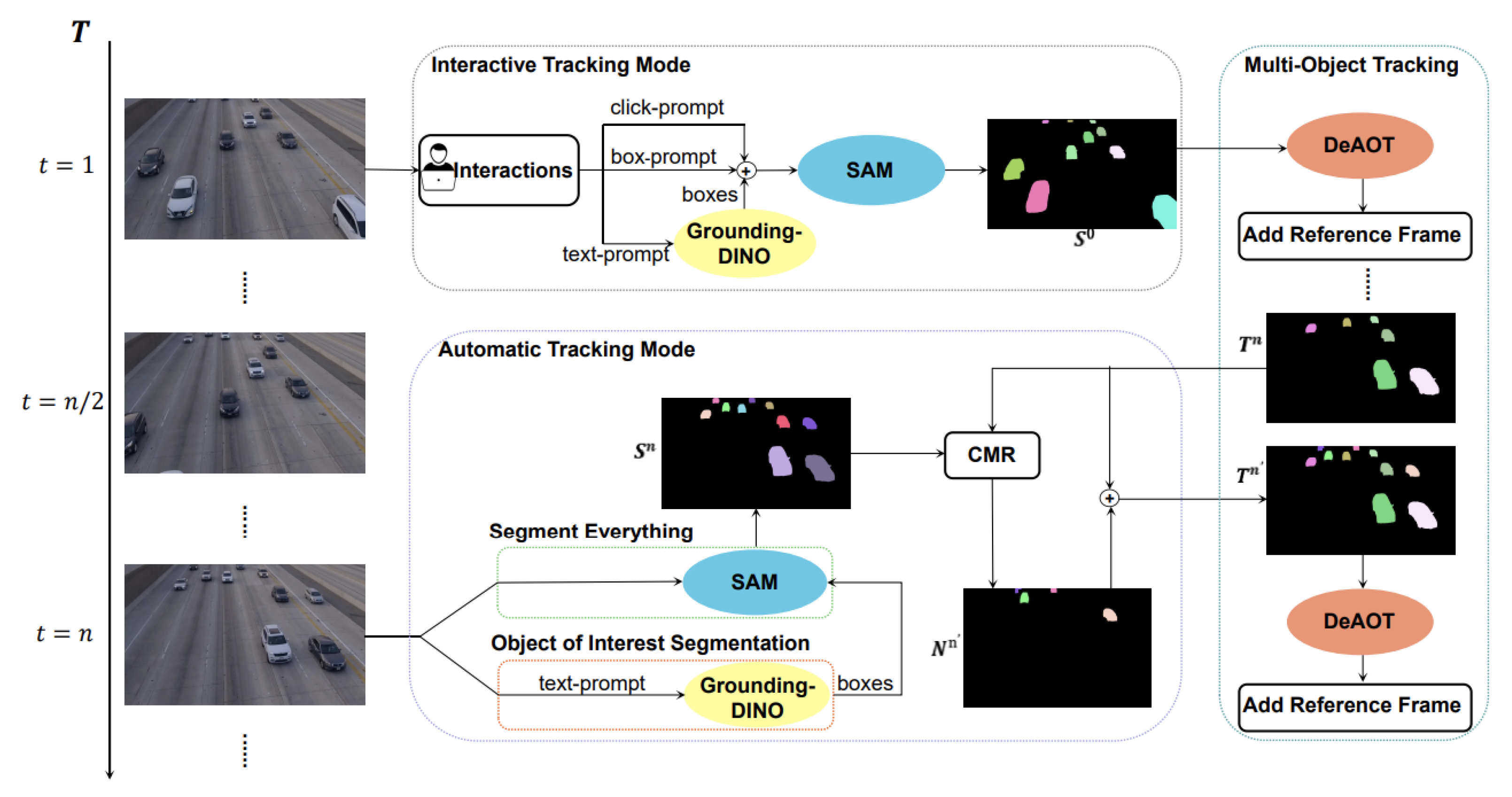

Figure 5.

Overview of a SAM-based multi-object tracking framework [

81]. The system supports both interactive and automatic tracking modes. In the interactive mode, object prompts (e.g., clicks, boxes, or text) are passed to Grounding-DINO and SAM to generate instance masks, which are tracked via DeAOT. In automatic mode, frames are processed by SAM with "segment everything" or object-specific prompts, and merged using context-aware reasoning (CMR). The resulting object masks are tracked using DeAOT with reference frame updates.

Figure 5.

Overview of a SAM-based multi-object tracking framework [

81]. The system supports both interactive and automatic tracking modes. In the interactive mode, object prompts (e.g., clicks, boxes, or text) are passed to Grounding-DINO and SAM to generate instance masks, which are tracked via DeAOT. In automatic mode, frames are processed by SAM with "segment everything" or object-specific prompts, and merged using context-aware reasoning (CMR). The resulting object masks are tracked using DeAOT with reference frame updates.

7.1.4. Multimodal Trackers

Multimodal trackers leverage heterogeneous sensor inputs such as RGB, depth (D), thermal (T), LiDAR (L), or event-based data to enhance robustness in complex environments. These models fuse complementary cues across modalities to improve tracking under challenging conditions like occlusion, low-light, or motion blur.

A common approach is to first extract features from each modality using dedicated encoders:

where

is the input signal and

is the modality-specific encoder.

The fused representation

is then obtained via a fusion function

:

where

may implement early fusion (concatenation), mid-level fusion (transformer blocks), or late fusion (score-level voting).

In transformer-based fusion, cross-attention is often used to align modalities:

where queries

Q, keys

K, and values

V are derived from features of different modalities.

Recent models like FELT [

82] introduce asynchronous fusion mechanisms to handle RGB and event streams jointly for long-term tracking, addressing issues of temporal misalignment. GSOT3D [

83] leverages RGB, depth, and LiDAR signals for real-time 3D tracking in autonomous scenarios, achieving strong performance on KITTI and GSOT benchmarks. VIMOT2024 [

84] introduces modality-specific encoders and transformer-based fusion to handle sensor shift across RGB, depth, and thermal domains. Meanwhile, ThermalTrack [

85] applies cross-attention to fuse RGB and thermal imagery in night-time surveillance applications, showing significant robustness to illumination changes.

7.1.5. Vision-Language Model (VLM)-Powered Trackers

Vision-Language Model (VLM)-powered trackers represent a major paradigm shift in tracking by conditioning object representations on textual descriptions, enabling open-vocabulary tracking and natural language grounding. These models are typically initialized from large-scale pretrained VLMs such as CLIP [

74], BLIP [

86], or GPT-4V [

87], and fine-tuned or adapted for spatiotemporal localization tasks.

Unlike traditional trackers that require exemplar templates or object category supervision, VLM-based trackers operate using language prompts that describe the object of interest (e.g., “the man in the red shirt”). The objective function often includes a contrastive alignment loss that matches visual features with text embeddings:

where

is the visual embedding of the query frame,

is the correct text prompt,

are candidate texts, and sim denotes cosine similarity.

Recent models like CLDTracker [

88] utilize dual-stream transformers to jointly encode visual and textual modalities and achieve state-of-the-art results on EgoTrack++ and TREK-150. PromptTrack [

89] learns prompt-aware temporal attention for better alignment between object descriptions and frame-wise evidence. Other models such as Track Anything [

90] integrate SAM with VLM-guided refinement modules for zero-shot object tracking.

VLM-based trackers are particularly strong at handling ambiguous or novel targets that lack predefined labels, and can generalize across domains with minimal retraining. However, their reliance on semantic priors from pretraining introduces biases toward common concepts and poses challenges in precise localization. Additionally, prompt design and phrasing sensitivity remain open research questions, especially in low-resource or real-time scenarios.

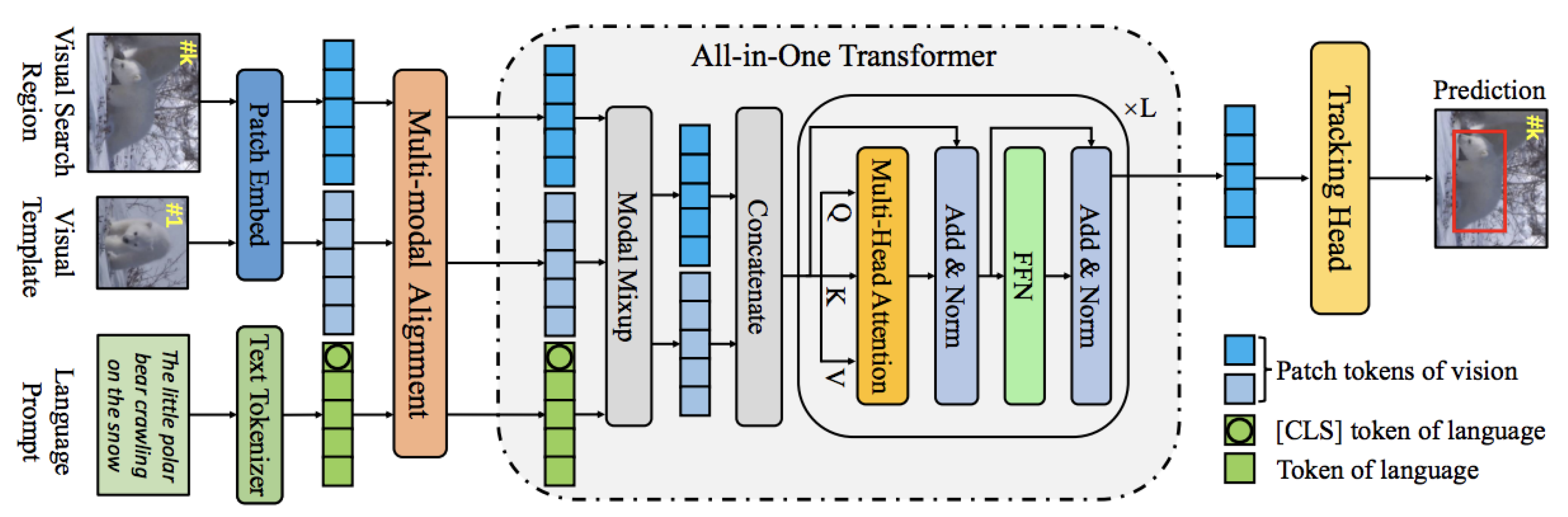

Figure 6.

Overview of the All-in-One vision-language tracker [

91]. The model unifies visual search region, visual template, and language prompts through multi-modal alignment. Features are embedded using separate vision and language encoders, followed by modal mixup and joint processing via a multi-head self-attention Transformer. The All-in-One Transformer encodes both modalities for tracking, and a shared tracking head predicts object locations in the target frame.

Figure 6.

Overview of the All-in-One vision-language tracker [

91]. The model unifies visual search region, visual template, and language prompts through multi-modal alignment. Features are embedded using separate vision and language encoders, followed by modal mixup and joint processing via a multi-head self-attention Transformer. The All-in-One Transformer encodes both modalities for tracking, and a shared tracking head predicts object locations in the target frame.

7.1.6. Instruction-Tuned Trackers

Instruction-tuned trackers leverage vision-language foundation models that have been aligned with natural language instructions via supervised or reinforcement learning objectives. These models are capable of following open-ended textual commands to condition the tracking objective, thereby enabling natural language grounding, multi-object tracking, and re-identification in a unified manner. Unlike fixed-language encoders or prompt-tuned trackers, instruction-tuned trackers generalize across tasks by learning task format and semantics during instruction tuning.

A typical architecture combines a pretrained vision backbone

(e.g., ViT, SAM) with a language encoder

(e.g., T5, OPT) and a fusion module

that integrates both modalities:

where

is the current video frame and

L is the instruction or textual prompt. The resulting fused representation

z guides object prediction via decoders or matching heads.

Track Anything [

90] demonstrates flexible object segmentation and re-identification across frames by integrating the Segment Anything Model (SAM) with instruction-following prompts. PromptTrack [

89] extends this further with language-driven multi-object selection using grounding-aware vision transformers. GPT-4V [

87] can track arbitrary objects in images and videos by interpreting prompts like “follow the person wearing red” or “track the object that enters from the left,” exhibiting emergent tracking capabilities without explicit supervision.

These models are promising for real-world applications in robotics, video editing, and surveillance, especially in scenarios where object categories are unknown or dynamically defined by users. However, limitations include prompt sensitivity, the need for large-scale instruction tuning data, and inconsistent reliability across modalities like thermal or depth input.

7.1.7. Prompt-Tuned Trackers

Prompt-tuned trackers represent a recent paradigm where vision-language foundation models are conditioned through prompts to perform tracking. Instead of fine-tuning all model parameters, lightweight prompt modules or embeddings are optimized to adapt large pretrained models to the tracking task. This design significantly reduces training cost while leveraging rich visual-language priors.

A common setup involves optimizing soft prompt vectors

prepended to visual or language tokens in a transformer-based model. The forward pass becomes:

where

is the tokenized input (e.g., query image, text prompt). The tracking objective may then combine similarity-based localization and a prompt-adapted classification loss:

where

measures alignment between the prompt-conditioned output and target object embeddings, and

supervises identity prediction.

Recent models include PromptTrack [

92], which adapts CLIP with learnable visual prompts for open-set tracking, achieving competitive results on OTB and LaSOT. FAMTrack [

93] introduces feature-aware memory prompting in a transformer backbone for long-term tracking. SAM-PD [

80] applies prompt-denoising on top of SAM, using text queries to localize and refine object masks in videos. Track-Anything [

90] builds on Segment Anything and LLaVA to support interactive tracking via language and mouse clicks. VIMOT-2024 [

84] uses modality-specific prompts to adapt foundation models across RGB, depth, and thermal domains, providing robustness to domain shifts.

These methods demonstrate the viability of prompt tuning for tracking tasks, offering generalization to unseen objects and modalities with minimal supervision. However, their effectiveness is often limited by prompt sensitivity and alignment quality, especially in cluttered or rapidly changing scenes. Designing optimal prompts remains a challenge, motivating hybrid approaches with retrieval-based guidance or reinforcement learning.

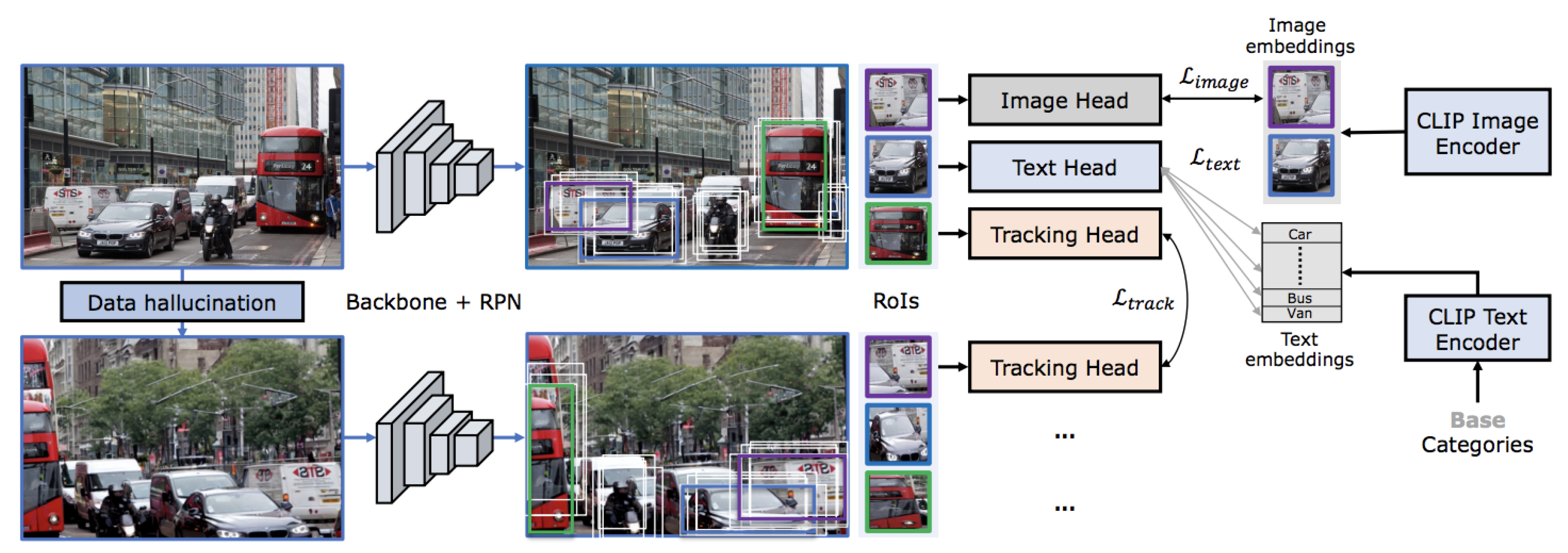

Figure 7.

OVTrack training pipeline: Backbone with RPN generates region proposals (RoIs). Image and text heads produce embeddings optimized via contrastive losses and aligned with CLIP encoders. The tracking head employs a tracking loss for temporal identity association. Data hallucination augments samples to enhance model robustness and generalization.

Figure 7.

OVTrack training pipeline: Backbone with RPN generates region proposals (RoIs). Image and text heads produce embeddings optimized via contrastive losses and aligned with CLIP encoders. The tracking head employs a tracking loss for temporal identity association. Data hallucination augments samples to enhance model robustness and generalization.

7.2. Meta-Analysis of Transferability

7.2.1. Cross-Model Representation Reuse

Recent advancements in vision-language and foundation models have enabled powerful feature representations that can be reused across tasks without task-specific fine-tuning. This subsubsection examines how such pretrained backbones—especially CLIP [

74], DINOv2 [

75], EVA-CLIP [

94], InternImage-V2 [

95], and SAM [

76]—contribute to transfer learning in tracking pipelines.

Rather than retraining models end-to-end, many recent works directly plug in these backbones to extract embeddings that serve as input for lightweight tracking heads. For instance, CLIP-based encoders are employed in CLDTracker [

88] and OVTrack [

96] to match natural language prompts with image regions. DINOv2 and InternImage-V2 are used in EfficientTAM [

79] to derive semantically rich and spatially precise features for object localization.

We define the

Transfer Gain metric to quantify the effectiveness of reused representations:

where

denotes the performance (e.g., AUC, SR, or HOTA) using the pretrained VLM backbone, and

refers to a conventional CNN-based tracker (e.g., SiamFC [

7] or STARK [

13]).

Empirical evidence shows that EVA-CLIP embeddings provide up to 15% relative gains in long-tail object scenarios on the TREK-150 [

97] benchmark. Similarly, InternImage-V2 enables dense correspondence learning in FAMTrack without supervision, outperforming classical ResNet50-based trackers by over 8 AUC points on LaSOT [

98].

Interestingly, SAM’s segmentation-aware features have also proven effective in zero-shot tracking tasks when adapted via prompt-denoising heads as in SAM-PD [

80], bridging detection and tracking with no explicit re-training.

Despite these advantages, foundation-model representations often require alignment modules or prompt engineering to work reliably across tracking settings. This highlights the need for stronger inductive biases or adapter-tuning frameworks that minimize domain shift when reusing large-scale features.

7.2.2. Cross-Dataset Transfer Evaluation

To assess the generalization capacity of pretrained vision and vision-language models, we analyze their performance across diverse tracking datasets without any fine-tuning. This subsubsection quantifies how well representations from models like CLIP [

74], DINOv2 [

75], EVA-CLIP [

94], InternImage-V2 [

99], and SAM [

76] transfer to different domains such as aerial views, egocentric videos, and nighttime scenes.

Let the performance metric (e.g., AUC or HOTA) of a pretrained model

M on dataset

be denoted as

. Then, the average cross-dataset generalization can be defined as:

where

N is the number of distinct datasets evaluated. Models with higher generalization scores are considered more transferable.

Empirical findings from recent works support this analysis. For instance, CLIP embeddings used in CLDTracker [

88] and OVTrack [

100] generalize well across LaSOT [

98], TREK-150 [

101], and Ego4D [

102], especially in text-guided setups. EVA-CLIP and InternImage-V2 demonstrate strong performance on UAV20L [

103] and VisDrone [

104] benchmarks without retraining, as observed in EfficientTAM [

79].Conversely, classical trackers like STARK [

13] and SiamRPN++ [

9] often struggle with such cross-dataset settings due to limited representation flexibility.

However, VLM-based trackers underperform in crowded or densely annotated datasets such as MOT17 [

23], where strong detection priors or object-specific fine-tuning are still crucial. Furthermore, models pretrained on web-scale data (e.g., CLIP) may inherit dataset biases, leading to uneven performance across demographics or environments.

These findings emphasize that while pretrained embeddings show remarkable transferability to semantically rich or sparse datasets, their applicability in dense tracking or long-term scenarios still requires further investigation and adaptation strategies.

7.2.3. Modality-Level Transfer Insights

This subsubsection analyzes how different input modalities—such as RGB, depth, thermal, event streams, and natural language—affect the transferability of pre-trained representations in tracking pipelines. As modern vision-language models increasingly support multiple modalities, understanding their differential impact is crucial for selecting or designing task-specific trackers.

Let

denote the input representation for modality

. For a tracking model

f with frozen backbone

, we define modality-aware transferability gain as:

where

is the performance of a supervised baseline using the same modality

m.

Recent work has shown that text-guided embeddings, as in PromptTrack [

105] and DUTrack [

106], provide high gains for open-vocabulary or referring-expression based tracking. Depth-aware models such as GSOT3D and thermal-assisted models like ThermalTrack [

107] leverage auxiliary spatial cues to improve occlusion handling and nighttime tracking. Event-driven models such as FELT [

108] encode motion-triggered representations from neuromorphic cameras, offering superior performance in high-speed and low-latency settings. However, these modalities often require specialized sensor inputs or careful calibration, limiting scalability. A modality hierarchy emerges from these studies: while RGB remains the default input modality, VLM-enabled text prompts and hybrid inputs (e.g., RGB+Depth or RGB+Text) yield greater transferability in semantically rich and long-tail settings. Conversely, niche modalities like thermal and event streams offer domain-specific robustness at the expense of generality and accessibility.

7.2.4. Challenges and Opportunities in Transferability

While foundation and vision-language models (VLMs) demonstrate strong generalization and zero-shot transferability, several challenges persist in adapting them effectively to tracking tasks.

First, the spatial and temporal resolution mismatch remains a fundamental issue. Most VLMs (e.g., CLIP, SAM) are pre-trained on static image-text pairs and lack fine-grained temporal modeling. This limits their ability to track fast-moving or occluded objects in videos. Furthermore, temporal information often must be implicitly captured via spatial cues unless additional modules like temporal adapters or memory-enhanced attention are introduced.

Another key challenge is

domain-specific brittleness. Models trained on large-scale internet data (e.g., CLIP, EVA-CLIP) often fail to generalize to real-world edge cases such as thermal imaging, low-light scenes, or egocentric viewpoints unless enhanced with domain-specific priors. For instance, ThermalTrack [

85] and GSOT3D [

83] address these limitations by integrating depth, thermal, or 3D cues, but at the cost of added modality complexity.

In terms of optimization, foundation-based trackers often suffer from

computational overhead, especially when leveraging large frozen encoders. This can be quantified via a compute-adaptivity trade-off curve:

where

denotes the efficiency of model

M in terms of performance-per-computation. Models like EfficientTAM [

79] try to balance this trade-off by integrating lightweight adapters or hybrid token pruning.

Despite these limitations, VLMs offer exciting opportunities. One such direction is

promptable tracking, where users specify targets via natural language or image region instead of initializing bounding boxes. Works like PromptTrack [

78] and Track Anything [

90] lay foundational efforts for flexible user interaction. These systems could be extended to multi-turn dialog-based tracking in long videos, grounded action recognition, or task-aware surveillance.

Finally,

alignment and distillation strategies represent promising frontiers. Embedding alignment between CLIP-like and tracking-specific features, or distilling representations from frozen VLMs into lightweight student models for real-time tracking, could offer a practical compromise. Adapter-tuning and contrastive pretraining on video-language datasets (e.g., Ego4D [

102], TREK-150 [

97]) also remain underexplored.

In summary, while VLMs have opened new avenues for generalization and usability in tracking, realizing their full potential will require innovations in architecture, supervision, and evaluation tailored to the temporal and interactive nature of the task.

7.3. Roadmap for Promptable Tracking