Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Joint control formulation. We pose a coupled optimization that integrates UAV kinematics, uplink NOMA scheduling with adaptive SIC ordering, and per-subchannel power allocation under minimum user-rate constraints, with the objective of maximizing the number of served users.

- Bounded-action PPO–GAE agent. We design a continuous-action actor–critic algorithm (PPO–GAE) with explicit action bounding for flight and power feasibility, yielding stable learning and safe-by-construction decisions.

- Realistic A2G modeling & robustness. We employ a 3GPP-compliant A2G channel and evaluate robustness to imperfect SIC and channel-state information (CSI), capturing practical impairments often overlooked in prior art.

- Ablation studies. We isolate the gains due to (i) NOMA vs. OMA, (ii) adaptive SIC ordering, and (iii) bounded action parameterization, and quantify their individual and combined benefits.

- Reproducibility. We release complete code and configurations to facilitate verification and extension by the community.

2. Related Work

2.1. UAV Path and Trajectory Optimization: Prior Art and Research Gap

2.2. State of the Art in UAV Wireless Optimization and the Disaster-Response Uplink Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Initialization

-

Users and channel setting.A set of users, , transmit to the UAV over frequency-selective channels impaired by additive Gaussian noise. Per-user channel gains and power variables are denoted and , respectively.

-

Spectrum partitioning and MAC policy.The system bandwidth is , partitioned into orthogonal subchannels, , each with . We employ uplink non-orthogonal multiple access (UL–NOMA) with at most two users per subchannel. User n allocates power subject to the per-UE budgetwhich is enforced in the optimization (see constraints). The UL–NOMA pairing and successive interference cancellation (SIC) rule are detailed later and used consistently during training (see Algorithm 1).

-

User field (spatial layout).Users are uniformly instantiated within a area (i.e., ). Alternative layouts (e.g., clustered, ring, edge-heavy) can be sampled for robustness; the initialization here defines the default field for the baseline experiments.

-

UAV platform and kinematic bounds.A single UAV acts as the RL agent and is controlled via 3D acceleration commands under hard feasibility limits:

- –

- altitude ( ft),

- –

- speed ( mph),

- –

- acceleration .

These bounds are baked into the action parameterization to guarantee feasibility by design (see the PPO action head and spherical parameterization). -

Time discretization.The environment advances in fixed steps of , which is used consistently in the kinematic updates, scheduling decisions, and reward aggregation.

3.1.1. Notation and Symbols

3.2. System Model

3.2.1. A2G Channel in 3GPP UMa

-

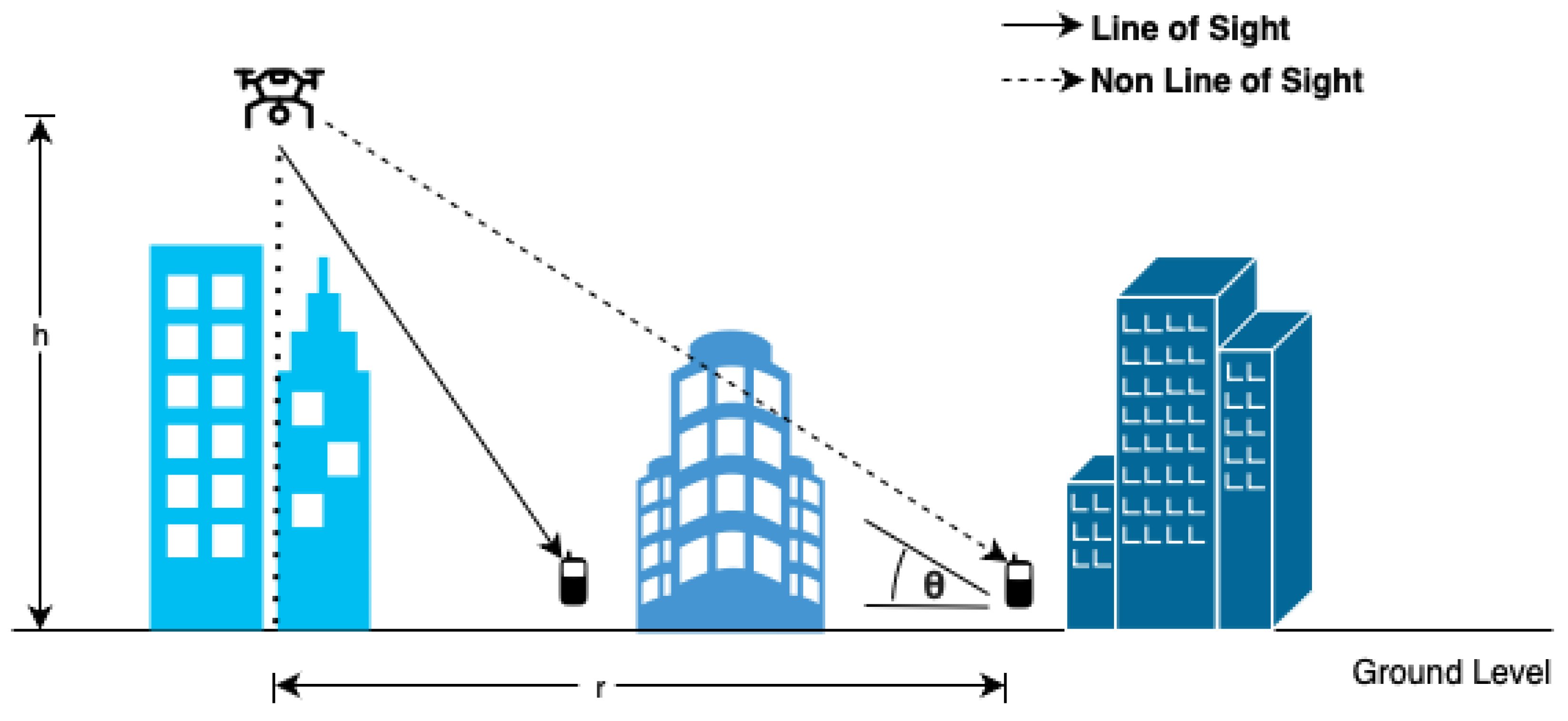

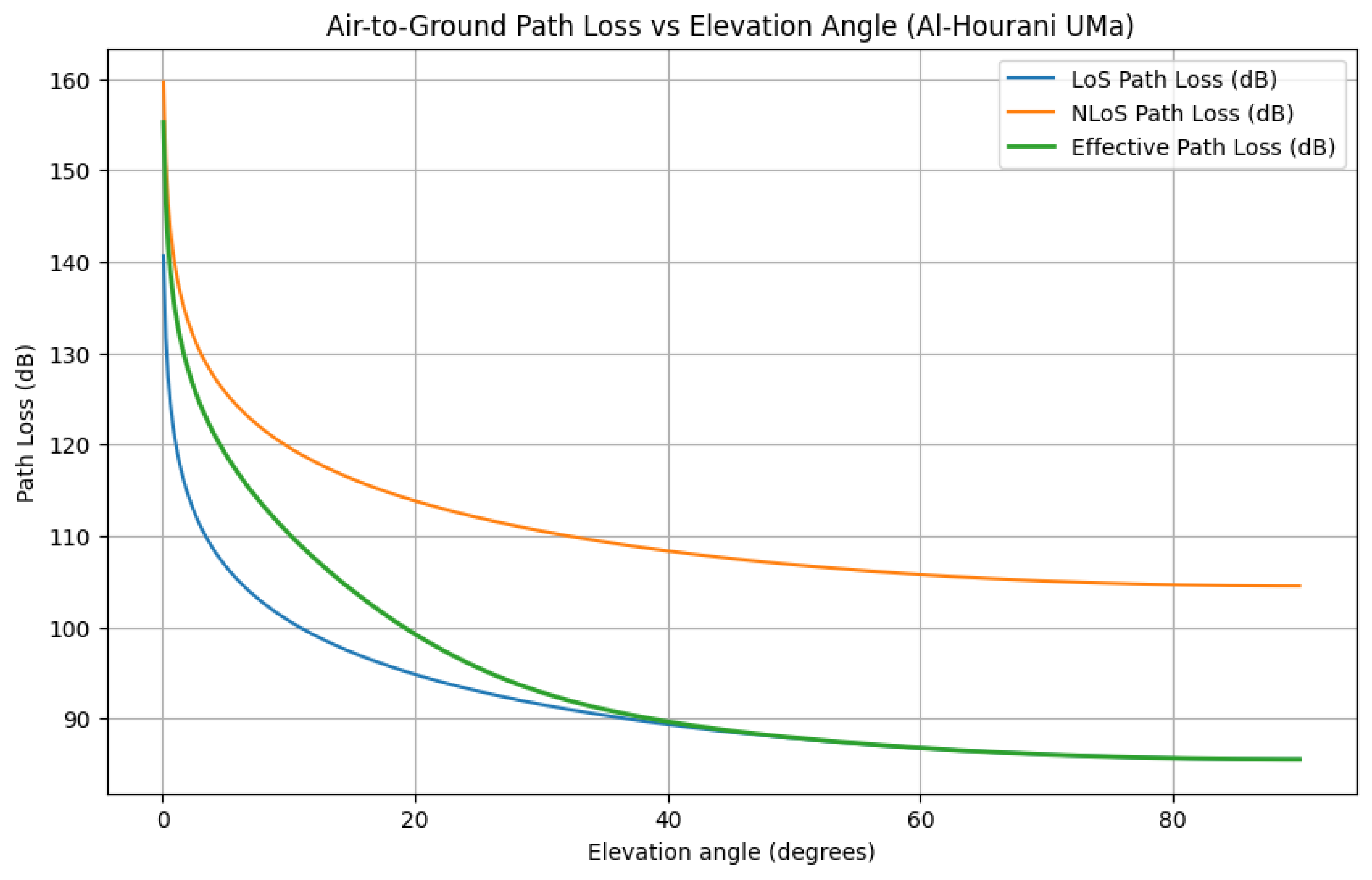

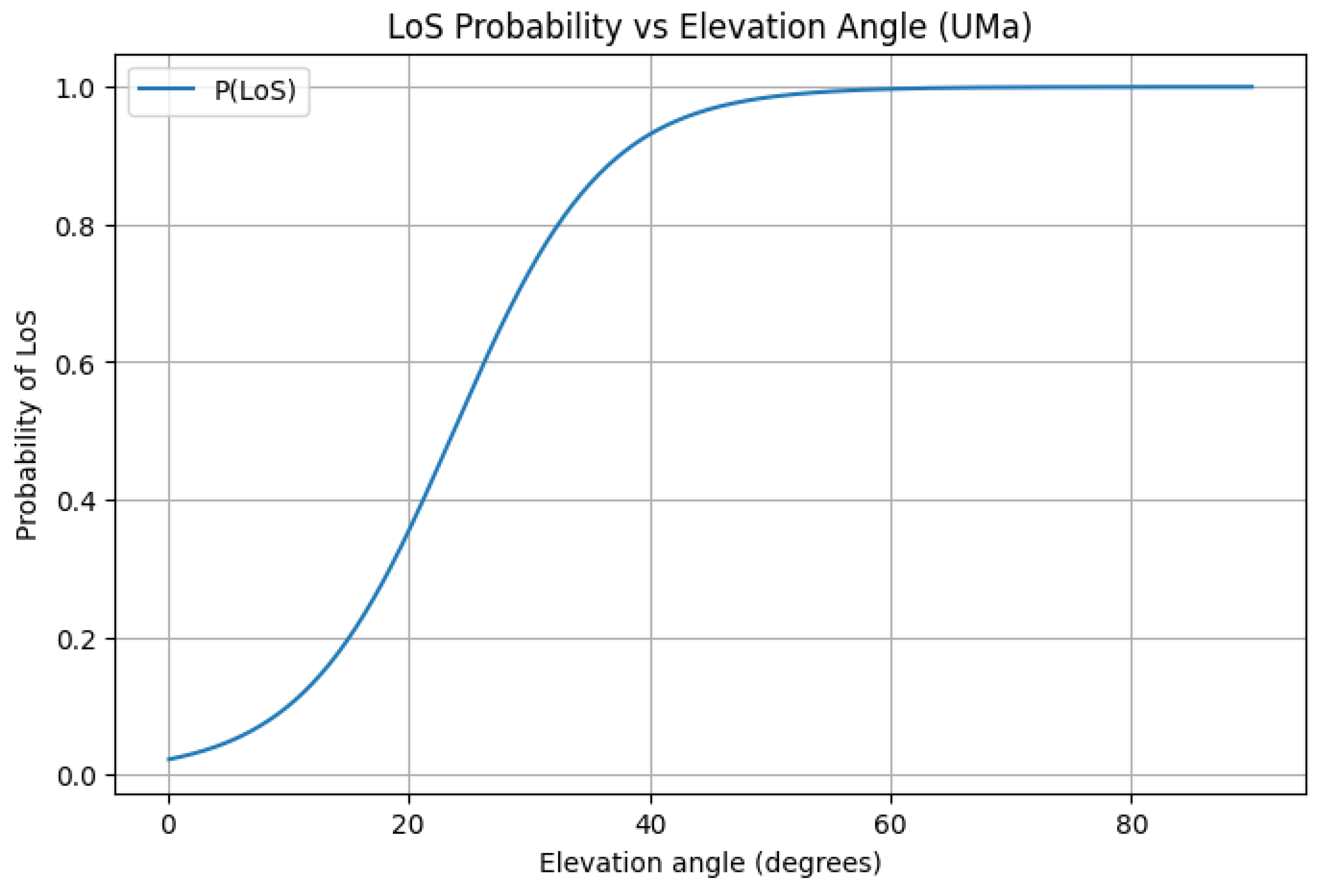

Environment and propagation modes.Following [41,42], the UAV base station (UAV-BS) is modeled as a low-altitude platform (LAP) operating in a 3GPP Urban Macro (UMa) environment. Radio propagation alternates probabilistically between LoS and NLoS conditions depending primarily on the elevation angle between the UAV and a given user equipment (UE); see Figure 1 for the geometry.

-

Geometry and LoS probability (Al-Hourani).Let the UAV be at horizontal coordinates and altitude , and user n be at . The ground distance and slant range areWith elevation angle (degrees) , the LoS probability iswith for urban environments [41]. Larger elevation angles typically increase , but higher altitudes also increase distance , creating a distance–visibility trade-off.

-

Path loss (dB) and effective channel gains (linear).Free-space loss at carrier iswith and c the speed of light. Excess losses for UMa are typically dB and dB, yieldingConvert to linear scale before mixing:and form the effective per-UE, per-subchannel gain as

-

Computation recipe (linked to Figure 1).

-

Interpretation and design intuition.Raising altitude improves visibility (higher ) but increases distance (higher ). Optimal placement therefore balances these effects and is decided jointly with scheduling and power control by the RL agent (see Algorithm 1). The net elevation trends are shown next.

3.2.2. Throughput Model (UL–NOMA with SIC)

-

Rate expression and interference structure.Using Shannon’s formula, the rate of user n on subchannel s iswhere is the subchannel bandwidth, the UE transmit power, the effective channel gain from (7), and the post-SIC residual interference.

- Receiver noise and SIC residuals. Per-subchannel noise (thermal plus receiver figure) iswith dB. UL–NOMA decodes in ascending received power or under an adaptive rule; the interference for user n on subchannel s iswhere denotes the decoding order, the scheduled set on s, and models imperfect SIC with residual factor . The elevation-driven behavior of and its impact on are visualized in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.2.3. Aerodynamic/Kinematic Update Model

-

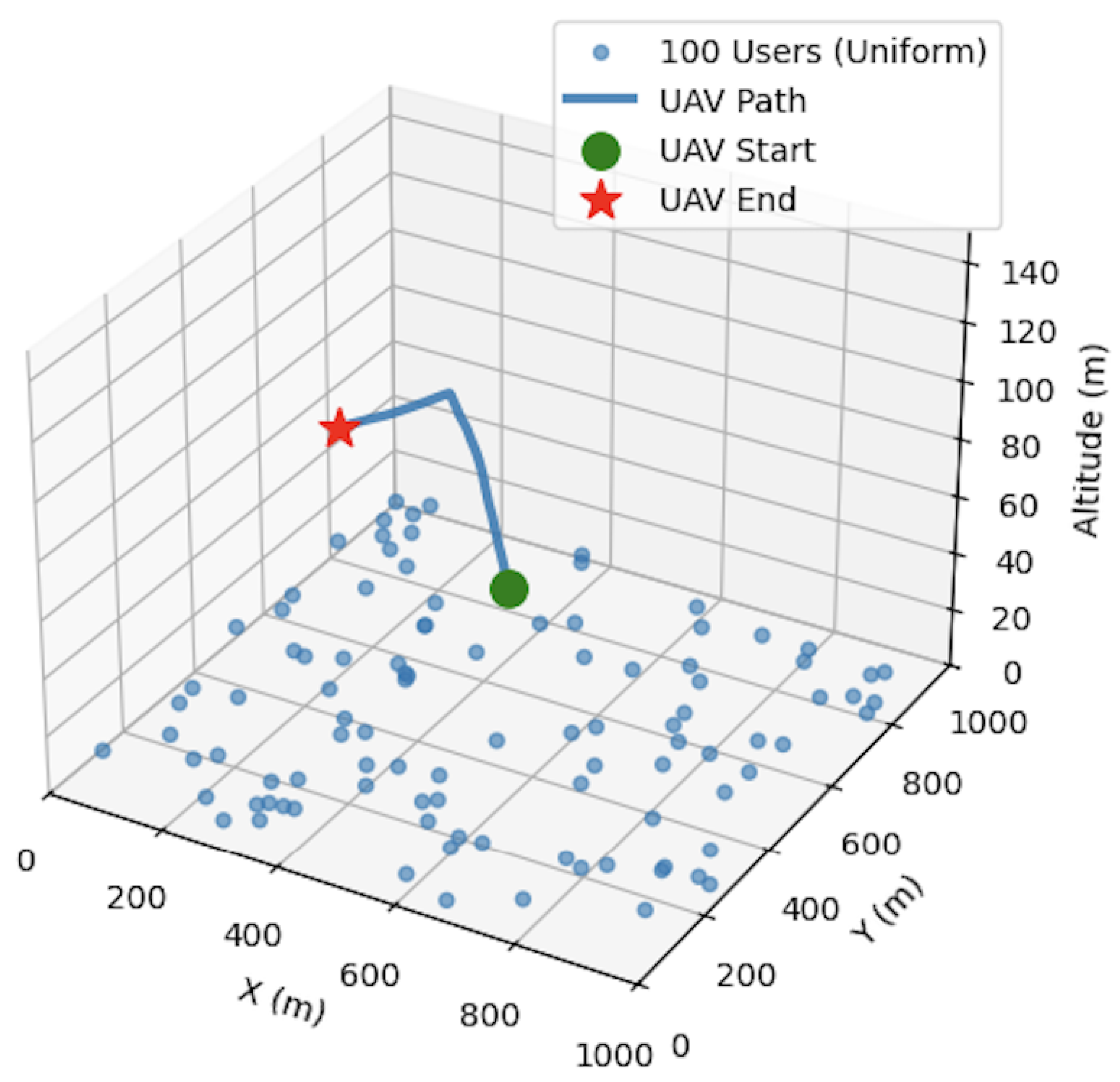

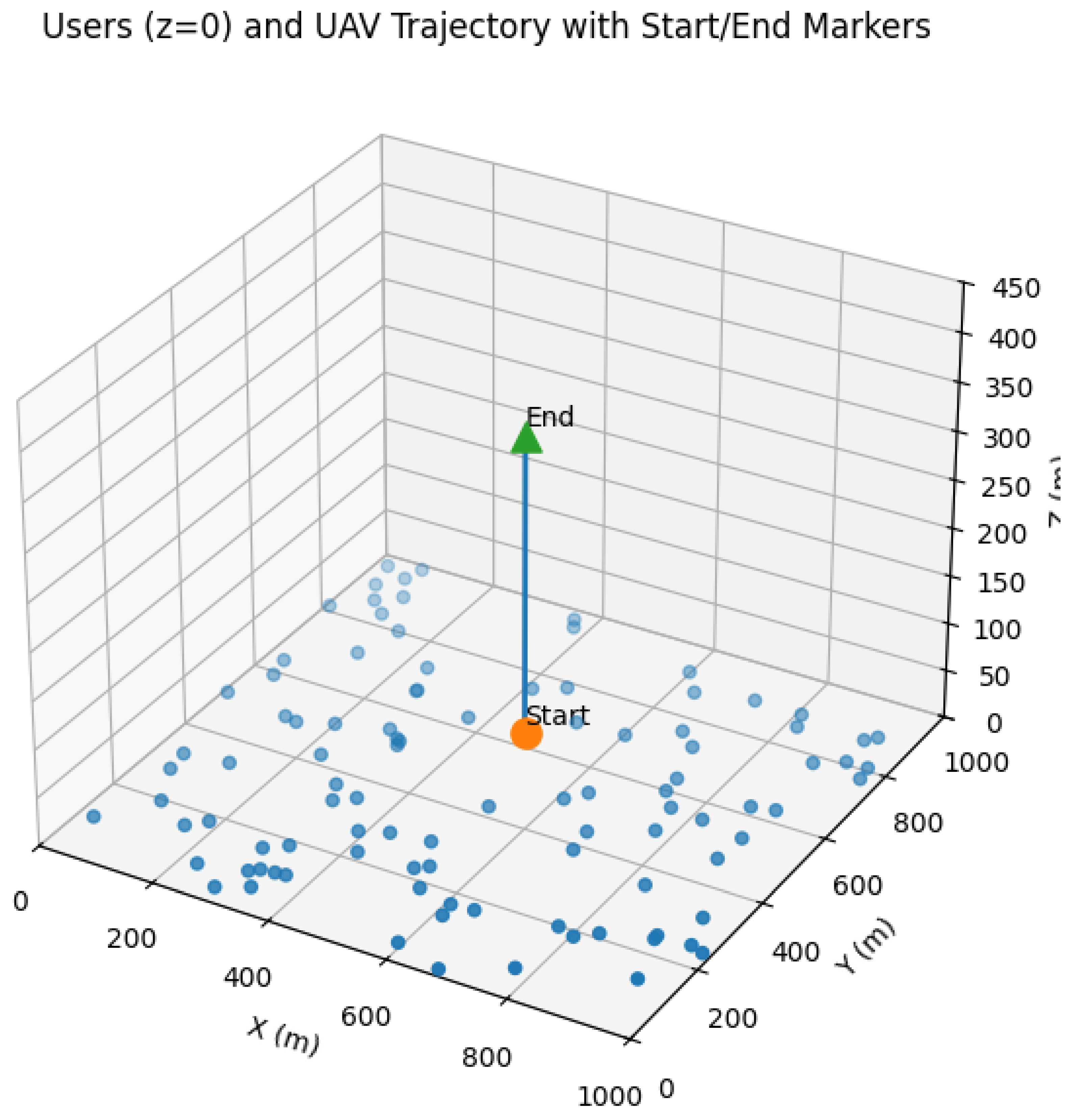

Semi-implicit (trapezoidal) integration.We update the UAV state from velocity and acceleration at time t (given and previously). The velocity update isand the position update iswhere the traveled distance isThis trapezoidal scheme preserves kinematic feasibility and aligns with the illustrative trajectory in Figure 2. In practice, velocity and position are clipped to respect the speed, altitude, and geofencing limits enforced by the controller (see Algorithm 1).

3.3. Problem Formulation

-

Scope, horizon, and decision variables.At each time , the controller selects (i) per-UE per-subchannel transmit powers and (ii) the UAV acceleration vector . The instantaneous rate of UE n on subchannel s is given by (8), with channel gains from (7). The aggregate rate of UE n iswhere follows Shannon’s law with UL–NOMA/SIC interference structure (cf. System Model).

-

Objective: rate-coverage maximization.Let be the per-UE target rate. Define the coverage indicatorThe optimization objective over an episode is

-

Constraints.We enforce communication, kinematic, geofencing, and regulatory constraints at every time step t:

- –

- Per-UE power budget:

- –

- Non-negativity:

- –

- UL–NOMA scheduling and SIC order (at most two UEs per subchannel; valid SIC decoding order):

- –

- Kinematics (acceleration and velocity; FAA bound [44]):

- –

- Geofencing (UAV horizontal):

- –

- User field (fixed deployment region):

- –

- Altitude bound (FAA Part 107 [44]):

-

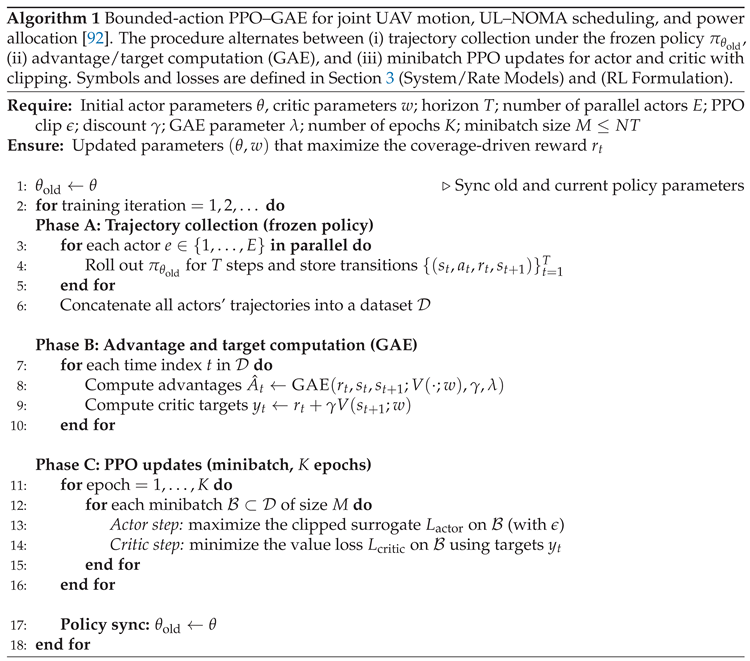

Solution strategy.We solve the coupled communication–control problem with a reinforcement-learning approach based on Proximal Policy Optimization with Generalized Advantage Estimation (PPO–GAE), using bounded continuous actions to ensure feasibility and training stability; see Algorithm 1 for the training loop placed near its first reference in the text.

-

Reward shaping.To align the RL objective with rate coverage while enforcing feasibility, the per-step reward iswith a composite penaltywhere each term is implemented as a hinge (or indicator) cost that activates only upon violation (e.g., ). The weights of these terms are tuned during simulation to reflect constraint priority.

-

State and actions.State at time t. We include (i) channel-gain status , (ii) UAV kinematic state (previous position/velocity) , and (iii) current allocation summaries (e.g., or normalized logits, subchannel occupancy, and recent SIC order statistics).Actions at time t. Two heads are produced by the actor: (i) UAV acceleration , and (ii) per-UE per-subchannel power fractions that are normalized into feasible powers.

-

Action representation (spherical parameterization).To guarantee by design, the actor outputs spherical parameters and maps them to Cartesian acceleration:with feasible domains , , and . This parameterization simplifies constraint handling and improves numerical stability [45].

-

Action sampling (Beta-distribution heads).The components , , and are sampled from Beta distributions , , and , respectively, naturally producing values on . After linear remapping (for angles), this yields bounded, well-behaved continuous actions and stable exploration near the acceleration limit .

-

Training HyperparametersTo ensure stable learning and reproducibility across layouts, we adopt a conservative PPO–GAE configuration drawn from widely used defaults and tuned with small grid sweeps around clipping, entropy, and rollout length. Unless otherwise stated, all values in Table 2 are fixed across experiments, with linear learning-rate decay and early stopping to avoid overfitting to any one topology.

-

PPO–GAE framework (losses and advantages).The actor is trained with the clipped surrogate,while the critic minimizes the value regression loss,Generalized Advantage Estimation uses TD error andbalancing bias and variance via .

-

Training loop and placement.The PPO–GAE training procedure for joint UAV motion, UL–NOMA scheduling, and power allocation is summarized in Algorithm 1.

3.4. Evaluation Protocol, Baselines, and Metrics

-

User layouts (testbeds).We evaluate four canonical spatial layouts within a field (Section 3, Initialization):

- Uniform: users are sampled i.i.d. uniformly over .

- Clustered: users are drawn from a mixture of isotropic Gaussian clusters (centers sampled uniformly in the field; cluster spreads chosen to keep users within bounds).

- Ring: users are placed at approximately fixed radius around the field center with small radial/azimuthal jitter, producing pronounced near–far differences.

- Edge-heavy: sampling density is biased toward the four borders (users within bands near the edges), emulating disadvantaged cell-edge populations.

Unless stated otherwise, the UAV geofence is the square centered on the user field (Section 3), with altitude constrained by FAA Part 107. -

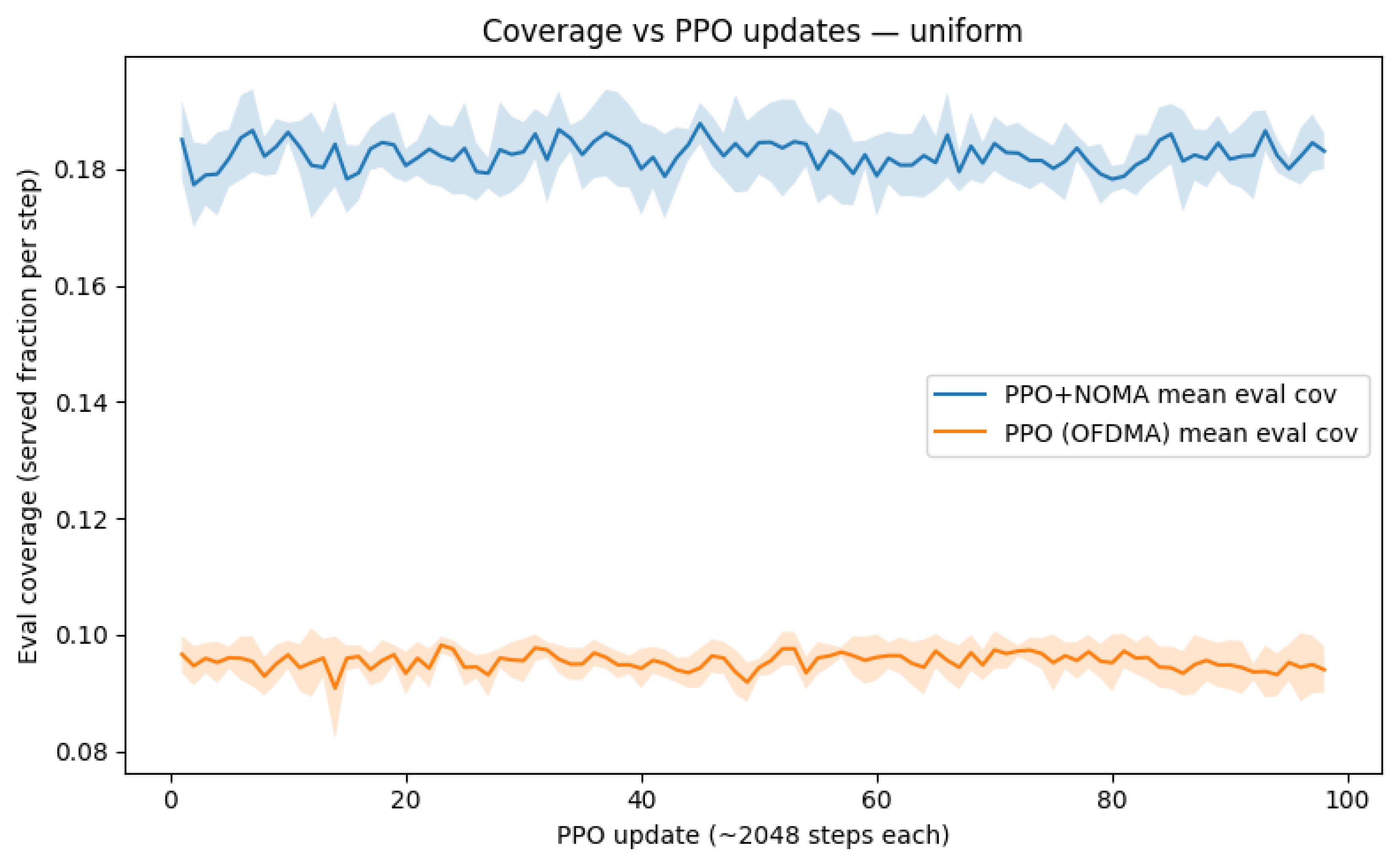

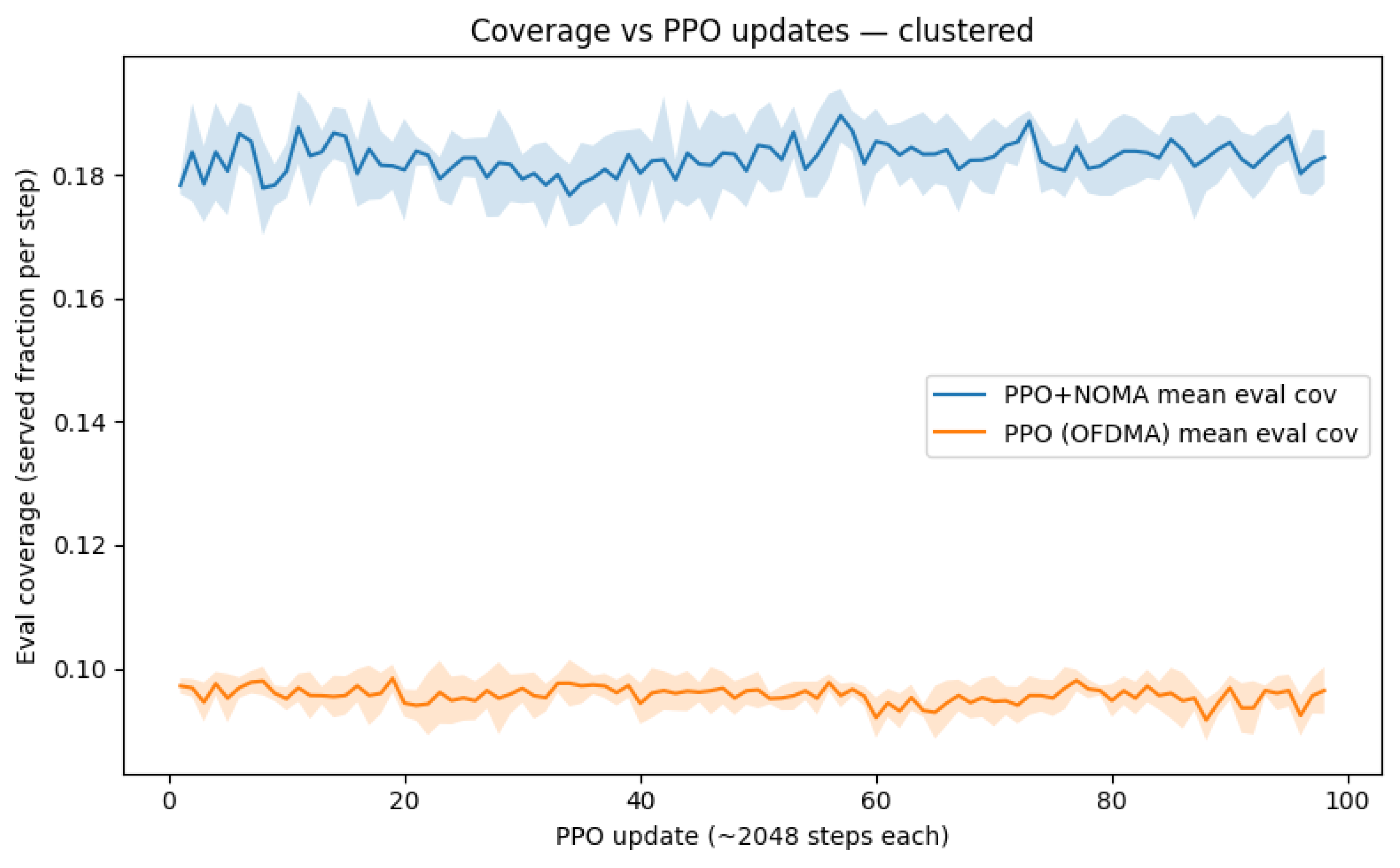

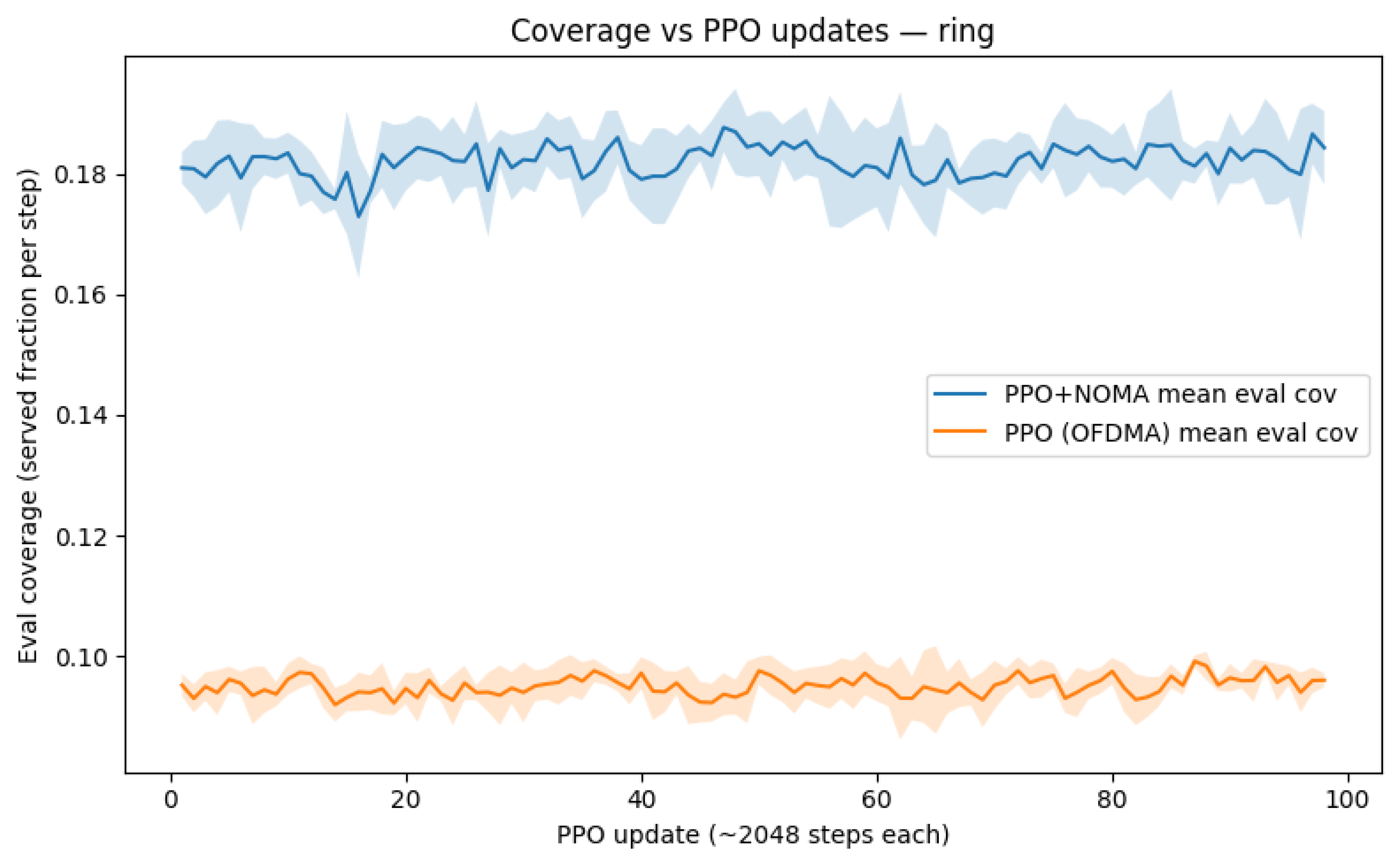

Train/validation protocol.Training uses 1000 episodes with horizon time steps (step ). We employ five training random seeds and five disjoint evaluation seeds (Section 3), fixing all hyperparameters across runs. After each PPO update (rollout length 2048 steps), we evaluate the current policy on held-out seeds and report the mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

-

Baselines.We compare the proposed PPO+UL–NOMA agent against:

- –

- PPO (OFDMA): same architecture/hyperparameters, but limited to one UE per subchannel (OMA) and no SIC.

- –

- OFDMA + heuristic placement: grid/elevation search for a feasible hovering point and altitude; OFDMA scheduling with per-UE power budget.

- –

- PSO (placement/power): particle-swarm optimization over plus a global per-UE power scaling factor; OFDMA scheduling.

All baselines share the same bandwidth, noise figure, and UE power constraints as the proposed method. -

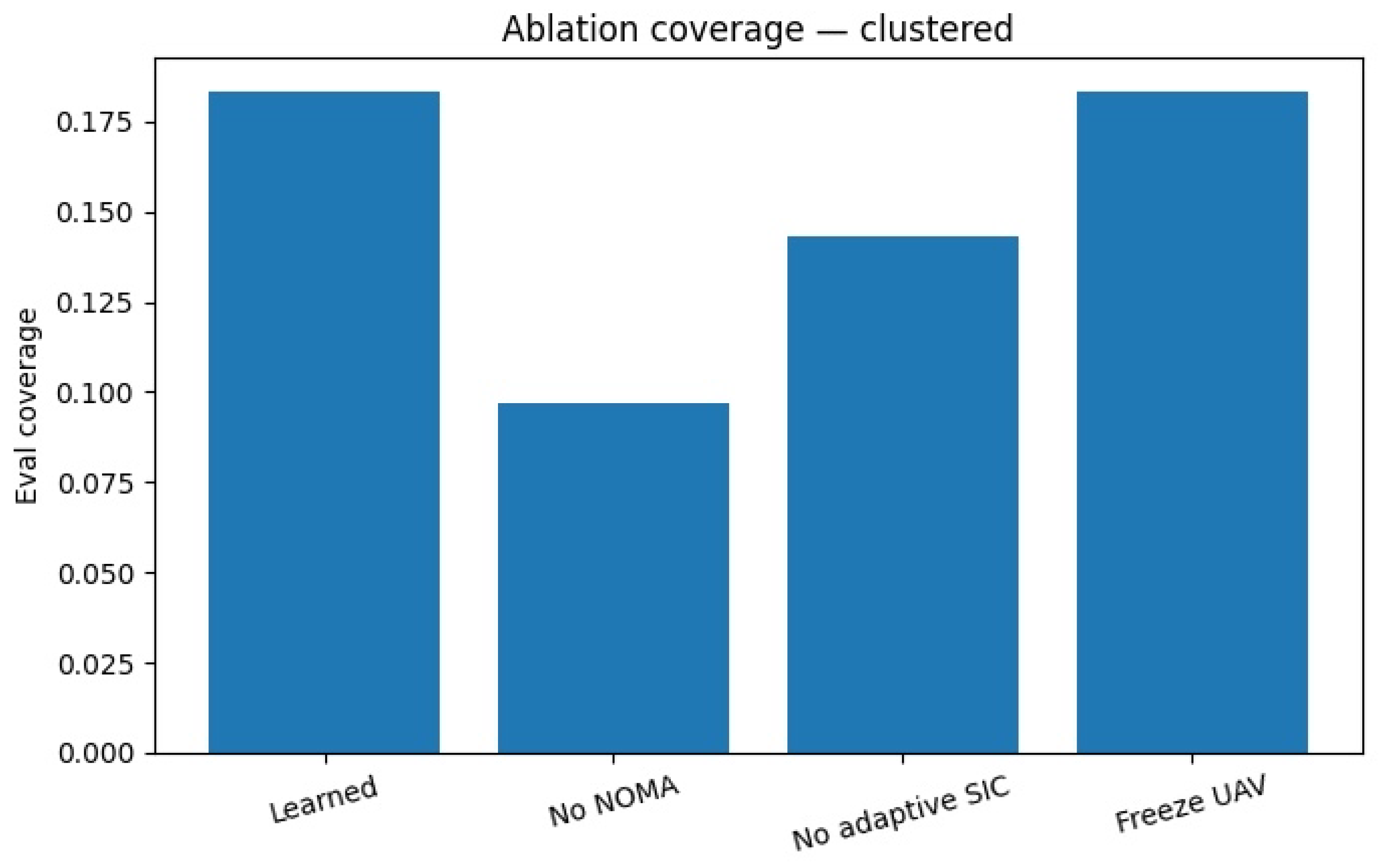

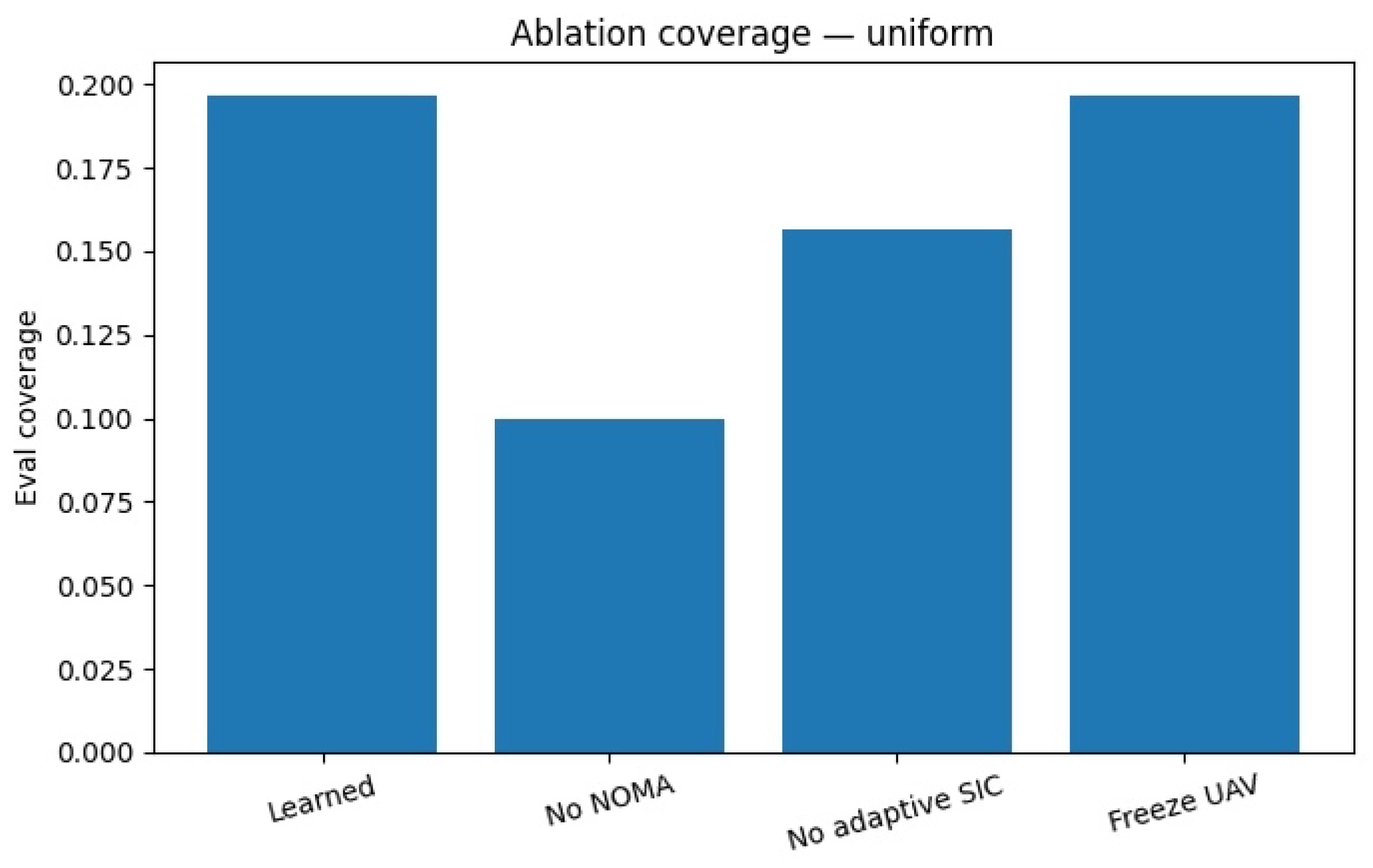

Ablations.To quantify the contribution of each component we perform:

- –

- No-NOMA: PPO agent with OMA only.

- –

- Fixed SIC order: PPO+NOMA with a fixed decoding order (ascending received power), disabling adaptive reordering.

- –

- No mobility: PPO+NOMA with UAV motion frozen at its initial position (power/scheduling still learned).

- –

- Robustness sweeps: imperfect SIC residual factor and additive CSI perturbations to channel gains.

-

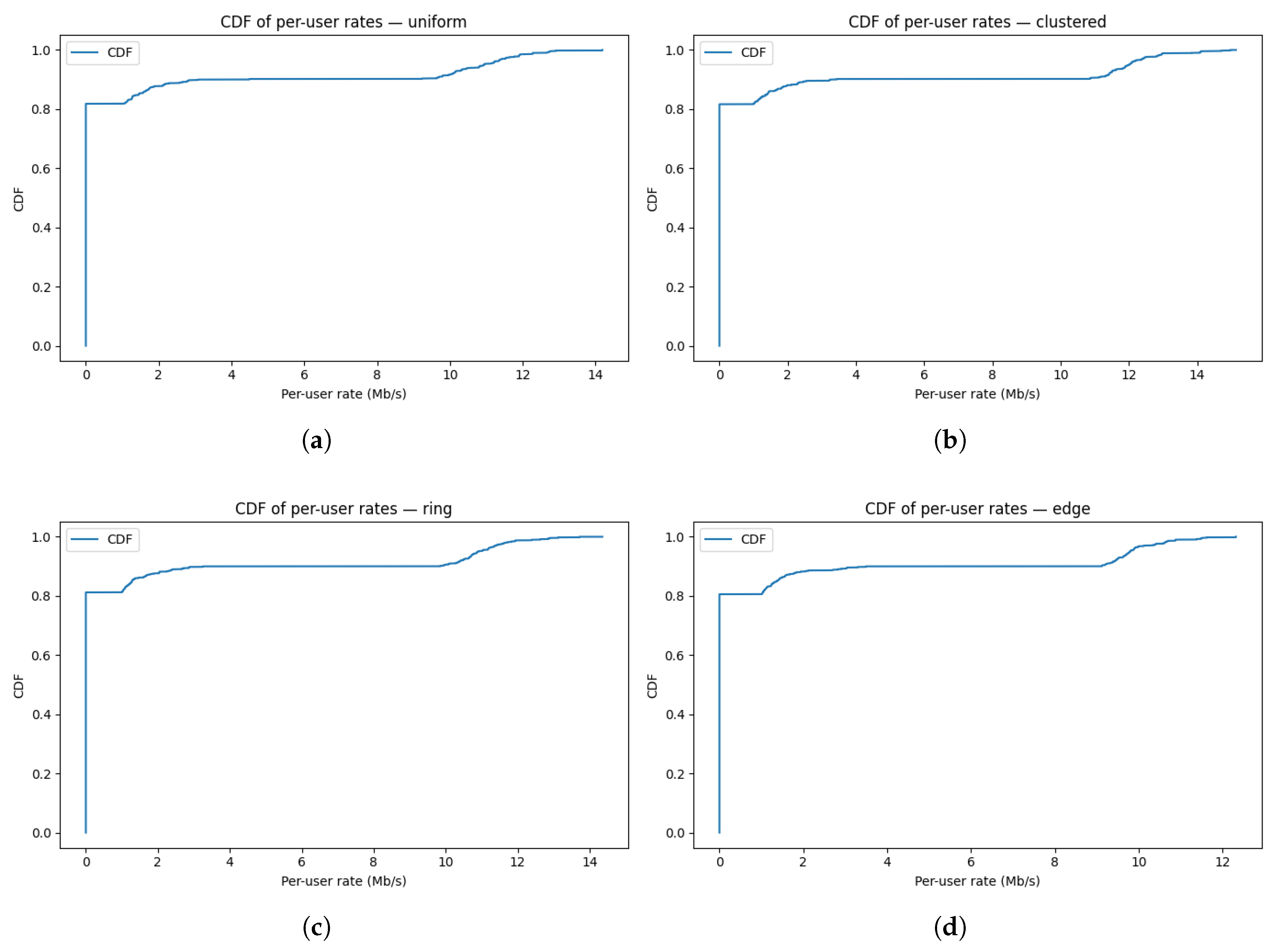

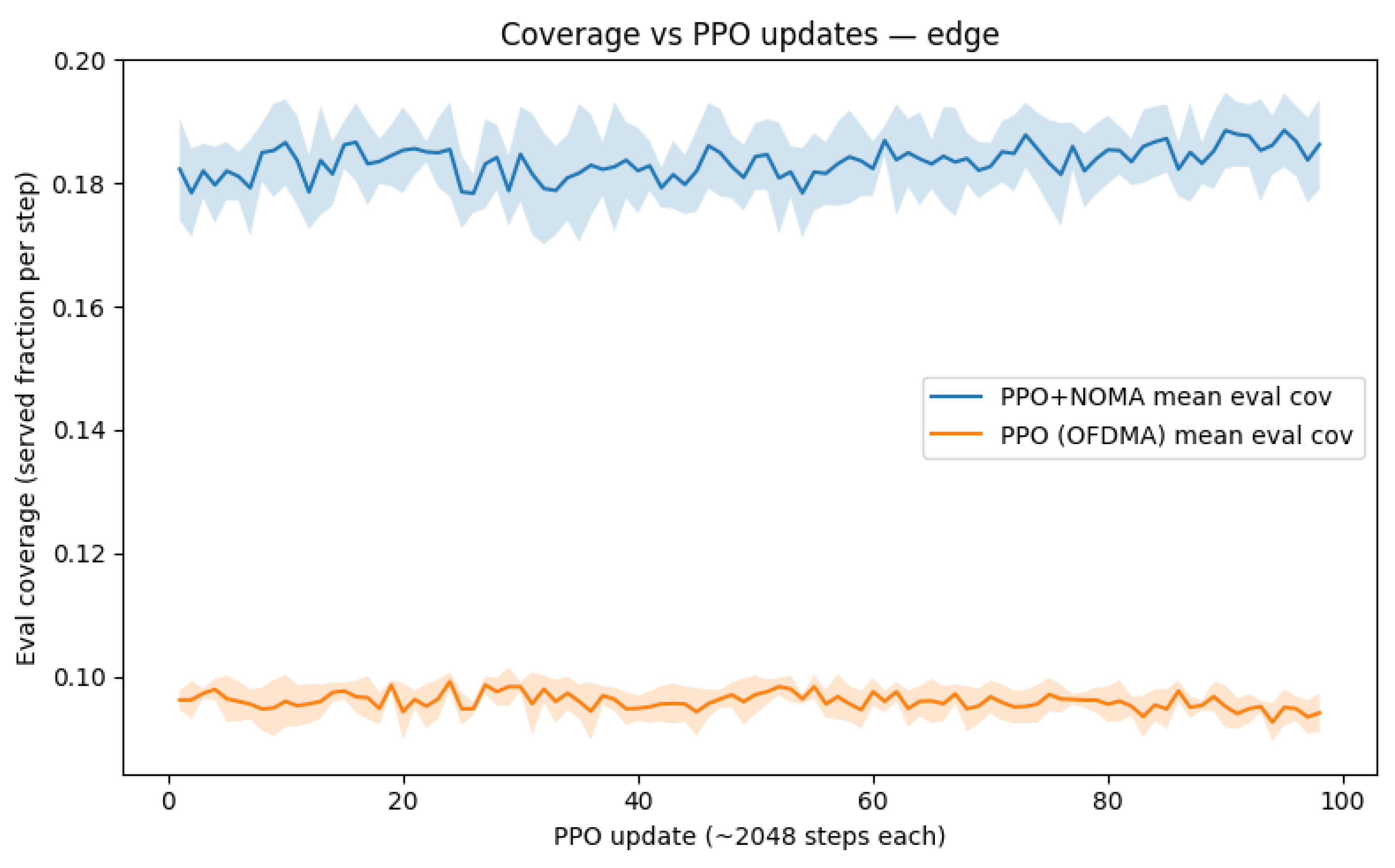

Primary and secondary metrics.The primary metric is rate coverage, i.e., the fraction of users meeting the minimum rate :Secondary metrics include: (i) per-user rate CDFs to characterize fairness, (ii) median UE transmit power to reflect energy burden at the user side, and (iii) training curves (coverage vs. PPO updates) to assess convergence behavior. Coverage-vs-update plots are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8; CDFs in Figure 12(a)–(d). Aggregate comparisons appear in Table 4 and Table 5; ablations are summarized in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

-

Statistical treatment and reporting.For each configuration (layout × method), we average metrics over evaluation seeds and episodes, and report the mean ± 95% CI. CIs are computed from the empirical standard error under a t-distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of independent trials minus one. Where appropriate (paired comparisons across seeds), we also report percentage-point (pp) gains.

-

Reproducibility.

4. Results

Notation for Results and Reporting Conventions

| Symbol | Meaning (units) |

|---|---|

| U | PPO update index (dimensionless) |

| T | Steps per PPO update (; dimensionless) |

| N | Number of users () |

| Minimum-rate threshold ( Mbps) | |

| C | Rate coverage: fraction of users with () |

| CDF of per-user rate: | |

| “pp” | Percentage points; e.g., |

| Layout | One of {uniform, clustered, ring, edge-heavy} |

4.1. Convergence of Rate Coverage Across Layouts

4.2. Ablation Studies: Contribution of Each Component

4.3. Learned UAV Behavior

4.4. Per-User Rate Distributions (Fairness Analysis)

4.5. Comparison with OFDMA and PSO Baselines

| Distribution | Coverage (NOMA) | Coverage (OFDMA) | Gain (pp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| clustered | 0.17840 | 0.09595 | 8.245 |

| edge | 0.19543 | 0.09486 | 10.057 |

| ring | 0.18599 | 0.09800 | 8.799 |

| uniform | 0.18063 | 0.09800 | 8.263 |

| Distribution | x (m) | y (m) | z (m) | Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clustered | 864.70 | -36.89 | 21.45 | 0.600 | 0.10 |

| uniform | 742.46 | 1445.02 | 91.09 | 0.921 | 0.10 |

| ring | 1490.73 | -150.89 | 165.55 | 0.312 | 0.10 |

| edge | 920.32 | 360.25 | 246.87 | 0.953 | 0.10 |

5. Discussion and Limitations

5.1. Key Findings and Practical Implications

-

Coverage gains across diverse layouts.Across uniform, clustered, ring, and edge-heavy deployments, the proposed PPO+UL–NOMA agent consistently improves rate coverage relative to strong baselines (Table 4 and Table 5). Typical gains over PPO with OFDMA lie in the 8–10 pp range, with the largest improvements in edge-heavy scenarios (Figure 8) where near–far disparities are most pronounced and adaptive SIC can be exploited effectively.

-

Fairness and user experience.Per-user rate CDFs (Figure 12(a)–(d)) show that the learned policy not only raises average performance but also shifts the distribution upward so that most users exceed . This is particularly relevant for emergency and temporary coverage, where serving many users with a minimum quality-of-service (QoS) is paramount.

-

Lower user-side power.Relative to baselines, the learned controller reduces median UE transmit power (by up to tens of percent in our runs), reflecting more favorable placement and pairing decisions. Lower UE power is desirable for battery-limited devices and improves thermal/noise robustness at the receiver.

-

Feasibility by design.The bounded-action parameterization guarantees kinematic feasibility, contributing to stable training and trajectories that respect FAA altitude and speed limits. The learned paths (Figure 11) exhibit quick exploration followed by convergence to stable hovering locations that balance distance and visibility (Section 3).

5.2. Limitations and Threats to Validity

-

Single-UAV, single-cell abstraction.Results are obtained for one UAV serving a single cell. Interference coupling and coordination in multi-UAV, multi-cell networks are not modeled and may affect achievable coverage.

-

Channel and hardware simplifications.We adopt a widely used A2G model (Al-Hourani in 3GPP UMa) with probabilistic LoS/NLoS and a fixed noise figure. Small-scale fading dynamics, antenna patterns, and hardware impairments (e.g., timing offsets) are abstracted, and Shannon rates are used as a proxy for link adaptation.

-

Energy, endurance, and environment.UAV battery dynamics, wind/gusts, no-fly zones, and backhaul constraints are outside our scope. These factors can influence feasible trajectories and airtime.

-

Objective design.We optimize rate coverage at a fixed . Other system objectives; e.g., joint optimization of coverage, average throughput, and energy introduce multi-objective trade-offs that we do not explore here.

5.3. Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | 3rd Generation Partnership Project |

| 5G | Fifth-Generation Mobile Network |

| A2G | Air-to-Ground |

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation (optimizer) |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| GAE | Generalized Advantage Estimation |

| LAP | Low-Altitude Platform |

| LoS | Line-of-Sight |

| MAC | Multiple Access Channel |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| NF | Noise Figure |

| NLoS | Non-Line-of-Sight |

| NOMA | Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OMA | Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OFDMA | Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access |

| pp | Percentage Points |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SIC | Successive Interference Cancellation |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UAV-BS | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Base Station |

| UL | Uplink |

| UL–NOMA | Uplink Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| UMa | Urban Macro (3GPP) |

References

- V, S. ; B. In V, V.; S M, K. Deep Q-Networks and 5G Technology for Flight Analysis and Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), 2024, 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electronics; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Efficient trajectory optimization and resource allocation in UAV 5G networks using dueling-Deep-Q-Networks. Wireless Networks 2024, 30, 6687–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Kato, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Uplink/Downlink Resource Allocation in High Mobility 5G HetNet. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2020, 38, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, S.; Qian, Y.; Hu, R.Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Dynamic Reputation Policy in 5G Based Vehicular Communication Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 6136–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, M.; Cervelló-Pastor, C.; Sallent, S. Deep Learning at the Mobile Edge: Opportunities for 5G Networks. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillouet, C.; Mitton, N. Optimization and Communication in UAV Networks. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exposito Garcia, A.; Esteban, H.; Schupke, D. Hybrid Route Optimisation for Maximum Air to Ground Channel Quality. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2022, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Khan, T.; Afshang, M.; Mozaffari, M. A: Air-to-Ground Network Design and Optimization, 2020; arXiv:cs.IT/2011.08379].

- Hu, H.; Da, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ni, L.; Pan, Y. SE and EE Optimization for Cognitive UAV Network Based on Location Information. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 162115–162126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, P.; Gagnon, F.; Tran, L.N.; Labeau, F. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation in Cooperative UAV-Assisted Wireless Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2021, 20, 7610–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubbati, O.S.; Lakas, A.; Guizani, M. Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Wireless-Powered UAV Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 16044–16059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, F.R. Intelligent Trajectory Design in UAV-Aided Communications With Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 8227–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, P.S.; Michailidis, E.T.; Nomikos, N.; Vouyioukas, D.; Kanatas, A.G. A Survey on Machine-Learning Techniques for UAV-Based Communications. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning in NOMA-Aided UAV Networks for Cellular Offloading. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 21, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jabbari, B.; Ansari, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning Driven UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 25449–25459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvirianti. ; Narottama, B.; Shin, S.Y. Layerwise Quantum Deep Reinforcement Learning for Joint Optimization of UAV Trajectory and Resource Allocation. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, F.; Wang, Y. Path Planning of UAV Based on Improved Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 89400–89411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Long, K.; Jiang, C.; Guizani, M. Joint Resource Allocation and Trajectory Optimization With QoS in UAV-Based NOMA Wireless Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2021, 20, 6343–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.; Vidal-Calleja, T.; Hitz, G.; Chung, J.J.; Sa, I.; Siegwart, R.; Nieto, J. An informative path planning framework for UAV-based terrain monitoring. Autonomous Robots 2020, 44, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; peng Yang, Z.; qing Chen, D.; yang Liang, S.; Ma, H. Maneuvering target tracking of UAV based on MN-DDPG and transfer learning. Defence Technology 2021, 17, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Fang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Jin, H.; Song, Y. Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for UAV Based on Improved RRT Algorithm. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society 2022, 2022, 4544499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maboudi, M.; Homaei, M.; Song, S.; Malihi, S.; Saadatseresht, M.; Gerke, M. A Review on Viewpoints and Path Planning for UAV-Based 3-D Reconstruction. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 5026–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X.; Zheng, D.; Gao, Y.; Ng, D.W.K.; Renzo, M.D. Trajectory Design for UAV-Based Internet of Things Data Collection: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 3899–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.Y.; Denizer, S.N. Multi UAV Based Traffic Control in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, D.S.; Masood, A.; Cho, S. 3D UAV Placement and Trajectory Optimization in UAV Assisted Wireless Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN); 2020; pp. 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Su, Z.; Xu, Q. Game theoretical secure wireless communication for UAV-assisted vehicular Internet of Things. China Communications 2021, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matracia, M.; Kishk, M.A.; Alouini, M.S. On the Topological Aspects of UAV-Assisted Post-Disaster Wireless Communication Networks. IEEE Communications Magazine 2021, 59, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, H.; Sun, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, N. Channel Assignment and Power Allocation Utilizing NOMA in Long-Distance UAV Wireless Communication. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 12970–12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chang, Z.; Guo, X.; Hämäläinen, T. Energy Efficient Resource Allocation for Wireless Powered UAV Wireless Communication System With Short Packet. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2023, 7, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, I. UAV-Aided Wireless Communication Designs With Propulsion Energy Limitations. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Dong, X.; Lu, T.; Xu, W.; Yuen, M. Distributed and Multilayer UAV Networks for Next-Generation Wireless Communication and Power Transfer: A Feasibility Study. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 7103–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guizani, M. Secure UAV Communication Networks over 5G. IEEE Wireless Communications 2019, 26, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Kumar, H.; Davari, A. Performance evaluation of OFDM transmission in UAV wireless communication. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Southeastern Symposium on System Theory, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Resource Allocation for 5G-UAV-Based Emergency Wireless Communications. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2021, 39, 3395–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Che, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, K. Throughput Maximization for Laser-Powered UAV Wireless Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops); 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R. Energy Minimization for Wireless Communication With Rotary-Wing UAV. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2019, 18, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnagar, S.I.; Salhab, A.M.; Zummo, S.A. Q-Learning-Based Power Allocation for Secure Wireless Communication in UAV-Aided Relay Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33169–33180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, Q.; Mao, K.; Ali, F.; Chen, X.; Zhong, W. Generative Network-Based Channel Modeling and Generation for Air-to-Ground Communication Scenarios. IEEE Communications Letters 2024, 28, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Ndreveloarisoa, A.F.; Desheng, W.; Heriniaina, R.F.; Murad, N.M.; Fontgalland, G.; Ravelo, B. Channel Modelling for UAV Air-to-Ground Communication. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical, Electronic and Communications Engineering (ELECOM); 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Li, T.; Mao, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, Q. A UAV-aided channel sounder for air-to-ground channel measurements. Physical Communication 2021, 47, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hourani, A.; Kandeepan, S.; Lardner, S. Optimal LAP Altitude for Maximum Coverage. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2014, 3, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X. Deploying UAV Base Stations in Communication Networks Using Machine Learning. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 2017.

- Demographics of the world. Demographics of the world — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_the_world?oldid=XXXXX, 2025. [Online; accessed 3 September 2025].

- Federal Aviation Administration. Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Regulations (Part 107). https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/small-unmanned-aircraft-systems-uas-regulations-part-107, 2025. Accessed: 3 September 2025.

- Yu, L.; Li, Z.; Ansari, N.; Sun, X. Hybrid Transformer Based Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Multiple Unpiloted Aerial Vehicle Coordination in Air Corridors. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2025, 24, 5482–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. CoRR 2017, abs/1707.06347. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Meaning (units) |

|---|---|

| N, | Number/set of users; index n |

| S, | Number/set of subchannels; index s |

| W, | System and per-subchannel bandwidth (Hz) |

| UAV position at time t (m) | |

| , | UAV velocity/acceleration (m·, m·) |

| , | Max UAV speed/acceleration |

| Min/Max UAV altitude (m) | |

| Carrier frequency (Hz) | |

| Effective channel gain (linear) for UE n on subchannel s | |

| , | UE power on s (W) and per-UE limit (W) |

| Receiver noise on s (W); NF: noise figure (dB) | |

| Residual interference for UE n on s (W) | |

| SIC decoding order on subchannel s | |

| SIC residual factor in | |

| , | Rate on s (bit·); per-UE target rate |

| Time step (s) | |

| Spherical-parameterized acceleration magnitude/angles | |

| , | Policy/value networks with parameters , w |

| , | Discount factor and GAE parameter |

| Generalized advantage estimate at time t | |

| System state at time t (features used by actor/critic) | |

| Agent action at time t (UAV accel. & power allocation) | |

| Immediate reward at time t (dimensionless) | |

| Critic value function parameterized by w |

| Component | Setting |

|---|---|

| Policy / Value architecture | Two-layer MLP (ReLU), orthogonal initialization |

| Optimizer | Adam; learning rate ; linear decay over training |

| Discount factor | |

| GAE parameter | |

| PPO clipping | |

| Entropy coefficient | |

| Value loss coefficient | |

| Gradient clipping | Global norm |

| Rollout length (per update) | 2048 environment steps |

| Minibatch size | 64 |

| PPO epochs per update | 10 |

| Action distribution | Beta heads (bounded in ); spherical accel. mapping |

| Episode horizon & step | steps; |

| Random seeds | 5 training seeds; 5 disjoint evaluation seeds |

| Early stopping | Coverage plateau; patience 20 updates |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).