2. Related Works

RQ1: What clustering algorithms have been used in UAV-assisted wireless coverage, and how do they perform in disaster scenarios?

Clustering algorithms are vital for optimising UAV-assisted wireless coverage, particularly in disaster scenarios. Among these, K-means and K-means++ have been widely adopted for clustering ground users and UAV deployment. K-means++ enhances the initial centroid selection, significantly improving the user throughput and satisfaction ratio [

1,

2,

3]. The Hybrid K-means PSO approach combines K-means with PSO, achieving a more balanced performance in terms of coverage, energy efficiency, and reliability [

4]. Particle swarm optimization (PSO) is another widely used technique for optimising cluster coverage and 3D UAV placement problems. It exhibits faster convergence and requires fewer UAVs than K-means [

5,

6]. The Ellipse Clustering Algorithm further contributes by adjusting the UAV antenna parameters to maximise the user coverage probability while minimizing the transmission power [

7]. Fuzzy Logic and Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) offer dynamic solutions such as cluster head selection based on sensor node energy and storage levels [

2]. An enhanced version, Fit-FCM, integrates additional factors such as energy, distance, and trust to improve cluster head selection in UAV-based wireless sensor networks [

8]. DBSCAN, a density-based clustering algorithm, has been used in conjunction with convex optimisation for UAV trajectory planning and charger allocation. This integration reduces the number of chargers required while boosting the overall throughput [

9]. Meanwhile, Log Linear Learning has proven effective for UAV deployment in disaster-stricken regions by using a UAV coverage utility function to ensure comprehensive network coverage [

10]. These algorithms have different strengths and weaknesses in disaster scenarios. K-means is effective for initial coverage and user satisfaction, although its performance can vary based on the centroid initialisation and distance metrics used [

1,

3]. It supports user association, optimal UAV placement, and altitude selection to maximise data rates in emergencies [

11]. PSO-based algorithms not only reduce the number of UAVs required, but also outperform GA and artificial bee colony (ABC) methods in terms of execution time and energy efficiency [

6,

12]. Fuzzy logic and fit fuzzy c-means clustering improve the lifetime of the network and reduce packet loss, which are crucial for reliable communication in WSNs assisted by UAVs [

2,

8].

DBSCAN minimises charger use and increases throughput, offering a cost-effective disaster response solution [

9]. Finally, log-linear learning has demonstrated both generality and the best performance compared with optimal selection algorithms in emergency deployments [

10].

Clustering algorithms, such as K-means, PSO, fuzzy logic, FCM, DBSCAN, and log-linear learning, are critical for enhancing the effectiveness of UAV-assisted wireless coverage. These methods contribute significantly to improving coverage, energy efficiency, and system reliability, particularly when the terrestrial communication infrastructure is compromised by the environment. While K-means and PSO offer robust overall performance, algorithms such as Fuzzy Logic and DBSCAN provide specialised advantages in terms of energy conservation and operational cost, making them indispensable in emergency and disaster response scenarios.

Table 1 compares eight clustering methods, K-means, K-means++, PSO, FCM, DBSCAN, and log-linear learning, used in UAV-assisted disaster scenarios. It highlights each method’s type, disaster support capability, optimisation goals, and respective strengths and limitations. For instance, K-means++ offers simplicity and fast convergence but is sensitive to centroid initialisation, whereas DBSCAN is cost-effective in sparse networks but struggles with scalability. This comparison sets the foundation for why a hybrid adaptive clustering method is needed in post-disaster UAV networks (see

Table 1).

RQ2: How have machine learning or neural models been used to guide clustering or adapt path planning in dynamic environments?

Machine learning and neural models have been increasingly applied to guide clustering and adapt path planning in dynamic environments. One notable approach is the Two-Stage Learning-Based Model, where the first stage extracts features of the surrounding environment and predicts the trajectories of dynamic obstacles, and the second stage utilises reinforcement learning to plan a feasible and efficient path based on those predictions. This model demonstrates high predictability and processing capacity for dynamic obstacles and successfully executes planning tasks in various dynamic scenarios [

13]. In the realm of Neural Network-Guided Path Planning, methods such as NST-PRM and NST-RRT employ neural networks trained on datasets generated through probabilistic roadmaps (PRM) and rapidly exploring random trees (RRT). These techniques notably reduce the dataset generation time and enhance path-planning efficiency in environments with numerous obstacles [

14]. A Graph Neural Network (GNN)-Based Planner, further improves planning by leveraging prior exploration experience and minimising replanning costs under unpredictable conditions. This results in a high planning performance with fast speeds and low path costs, outperforming both traditional and other learning-based methods [

15]. Another advancement is the Dynamic Distance Transform Algorithm, in which a neural model adapts the distance transform method for dynamic contexts, forming a dynamically updating potential field. This ensures an effective local adaptation and optimal path planning in dynamic environments [

16].

In terms of Clustering for Path Planning, cluster-based routing for UAVs integrates online path planning, clustering-based network topology, reinforcement-learning-driven cluster management, and data routing. The outcomes include improved coverage, better adaptation to changing environments, enhanced packet delivery ratios, and reduced communication delays [

17]. Furthermore, combining clustering and neural networks for trajectory prediction, such as the use of DBSCAN and multicell neural networks (MCNN), produces accurate short-term 4D trajectory predictions, demonstrating their robustness and effectiveness in dynamic settings [

18,

19].

Among Hybrid and Reinforcement Learning Approaches, Q-Learning-Based Local Planning considers factors such as path length, safety, and energy consumption and shows reliable performance in both static and dynamic environments by avoiding the typical pitfalls of conventional algorithms [

20]. When Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are combined with Q-learning, the ANN serves as a path-planning controller, whereas Q-learning generates training samples. This hybrid strategy is more effective than using either technique alone to find optimal paths [

21]. In practical applications, Multi-Robot Systems (MRS) benefit from improved neural dynamics approaches that incorporate territorial mechanisms, resulting in robust and fair path planning in complex and changing environments [

22]. Similarly, Autonomous Vehicles leverage deep reinforcement learning and clustering-based strategies to develop both theoretical models and practical solutions for effectively navigating dynamic surroundings [

23,

24].

The integration of machine learning and neural models has significantly improved path planning and clustering performance in dynamic environments. By enhancing efficiency, adaptability, and accuracy, these methods, particularly those involving reinforcement learning, neural networks, and clustering, effectively address the challenges posed by dynamic obstacles and varying conditions.

Table 2 lists various ML- and NN-based frameworks that assist in UAV path planning and clustering in dynamic environments. It spans methods such as Two-Stage ML+RL models, GNN, neural potential fields, and hybrid RL-routing systems. The table clarifies their roles in clustering, path planning, adaptability to environmental changes, and trade-offs between complexity and data dependency. This provides the motivation for integrating ANN-guided clustering into the proposed model ( see

Table 2).

RQ3: What hybrid clustering or dynamic strategy selection methods exist, and how do they affect trajectory or resource efficiency?

Hybrid clustering and dynamic strategy selection methods have been introduced to enhance trajectory planning and resource efficiency in various applications. One of such approach is the Hybrid Selection Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (HSMEA), which combines angle and distance metrics for clustering individuals, followed by a hybrid selection mechanism. This method strikes an effective balance between convergence and diversity, making it suitable for complex multi-objective optimisation tasks [

25]. Another notable method, the Density-based K-means (DKGK) approach, utilises Differential Evolution (DE) to promote diversification, K-means for refinement, and a GA enhanced with heuristic crossover to ensure fast convergence. This combination outperforms conventional approaches, such as DE, GA, DE-K-means, and GA-K-means, by significantly reducing intra-cluster distances, leading to better clustering accuracy and efficiency [

26].

The hybrid grasshopper and differential evolution-based optimisation algorithm (HGDEOA) integrates adaptive strategies into DE, thereby enhancing its global search ability and reducing the risk of premature convergence. This results in improved energy stability, higher throughput, and extended network lifetime in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) [

27]. Similarly, the Hybrid Deep Fixed K-Means (HDF-KMeans) approach merges Deep K-Means++ for advanced feature extraction and centroid initialisation with Fixed Centered K-Means to improve stability. This hybrid model enhances clustering accuracy and consistency, particularly in critical domains such as healthcare [

28].

Among the Dynamic Strategy Selection Methods, the Dynamic Genetic Algorithm (DGA) improves the automatic calculation of the number of clusters (k) and improves the population initialisation, genetic operators, and fitness functions. These improvements lead to more accurate clustering outcomes and better estimation of the cluster numbers [

29]. The Gaussian Mutation Adaptive Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (GAAFSA) incorporates Gaussian mutation and adaptive strategies to avoid local optima and early convergence, which boosts the network lifespan, increases packet reception rates, and reduces packet loss in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks (IWSNs) [

30]. Meanwhile, adaptive density peak clustering with Fisher linear discriminant (ADPC-FLD) employs kernel density estimation and weighted Euclidean distances, along with adaptive strategies for selecting cluster centres. This significantly enhances the clustering accuracy and efficiency, particularly in high-dimensional data scenarios [

31].

Regarding the effects on trajectory and resource efficiency, methods such as HGDEOA and GAAFSA contribute significantly to energy efficiency and network longevity by optimising cluster head selection and data transmission in WSNs and IWSNs [

27,

30]. In terms of convergence and diversity, HSMEA and DKGK provide robust clustering solutions that enhance system performance [

25,

26]. For applications demanding high precision, such as healthcare and complex data analysis, techniques such as HDF-KMeans and ADPC-FLD deliver notable improvements in precision and consistency [

28,

31]. Hybrid clustering and dynamic strategy selection methods offer meaningful advancements in trajectory optimisation and resource efficiency. By enhancing energy stability, promoting balanced convergence and diversity, and increasing clustering accuracy, these techniques are valuable in a wide array of technical domains.

Table 3 compares hybrid approaches, such as HSMEA, DKGK, HGDEOA, and adaptive clustering methods. Each combines different algorithms (e.g., DE+GA+K-means) to optimize clustering accuracy, convergence, and resource use. The strengths of these models include improved energy stability and accuracy; however, their limitations often involve parameter tuning or domain-specific constraints. The discussion in this paper leverages this to justify the hybrid APC–DBSCAN + ANN framework (see

Table 3).

RQ4: What fitness functions or multi-objective optimisation approaches are most effective for UAV path planning in DRNs?

To identify the most effective fitness functions or multi-objective optimisation approaches for UAV path planning in DRNs, various insights have emerged from recent research. Several

fitness functions are typically used in this context. One core focus is on minimising both

distance and risk, as seen in methods that apply the Bézier theory and impose constraints such as turning angle and flight altitude [

32]. Similarly, another study incorporated travelling distance and risk along with height, angle, and slope limitations to guide UAV navigation [

33].

Energy efficiency is another critical criterion. Some models aim to reduce fuel consumption, altitude costs, and threat exposure during flights [

34]. In particular, Bézier curve-guided paths optimised via GAs and multi-objective swarm-based strategies are effective in improving energy use [

35]. In

multi-UAV systems, utility-based objectives such as maximising the number of people rescued are coupled with collision avoidance to ensure operational safety [

36]. Additionally,

Quality of Service (QoS) is emphasised in UAV-assisted Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) frameworks, where path planning considers geometric distance, risk level, and terminal user demand [

37]. Several techniques have been proposed for textbfmulti-objective approaches. A

knee-guided differential evolution algorithm directs the search toward optimal UAV paths with smooth trajectory generation [

32], whereas another variant incorporates an

adaptive selection mutation to improve refinement while preserving exploration [

33].

Reinforcement learning (RL) methods are effective in dynamic urban settings, optimising UAV paths under conditions of mobile obstacles and variable threats [

37].

GAs remain widely used for path optimization due to their versatility in complex optimisation. One approach normalizes the fitness criteria and employs swarm-based enhancements for energy efficiency [

35]. Another study combined an

adaptive GA for mission assignment with an

improved artificial bee colony method for optimal path planning [

38]. The

Hybrid Equilibrium Optimizer (HEO) uses techniques such as Gaussian distribution estimation and Lévy flight to divide populations and balance exploration and exploitation [

34]. Moreover,

Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO) has been improved for accurate 3D path planning, minimising flight path length, and terrain threats [

39].

Table 4 outlines the fitness criteria, such as distance, risk, energy, and QoS, alongside the optimisation technique used (e.g., DE, RL, GA, hybrid metaheuristics, ACO). This emphasises that effective UAV path planning must balance efficiency, safety, and adaptability. This reinforces why the proposed GA-based framework incorporates multiple weighted objectives ( see

Table 4).

Effective UAV path planning in DRNs using GA depends on fitness functions that measure distance, risk, energy consumption, and mission utility. Multi-objective optimisation techniques, such as differential evolution, reinforcement learning, GAs, hybrid optimisation, and ant colony optimisation, exhibit strong capabilities in navigating complex dynamic environments. Each technique offers unique strengths, ranging from convergence speed to adaptability, making it appropriate for different operational requirements. Expanding

Table 4,

Table 5 details the scope, strengths, and limitations of specific optimisation approaches, such as knee-guided DE, RL-based planning, GA+swarm hybrids, and enhanced ACO. It shows how each method addresses constraints such as smoothness, collision avoidance, and threat minimisation, further supporting the design choices in the hybrid framework (see

Table 5).

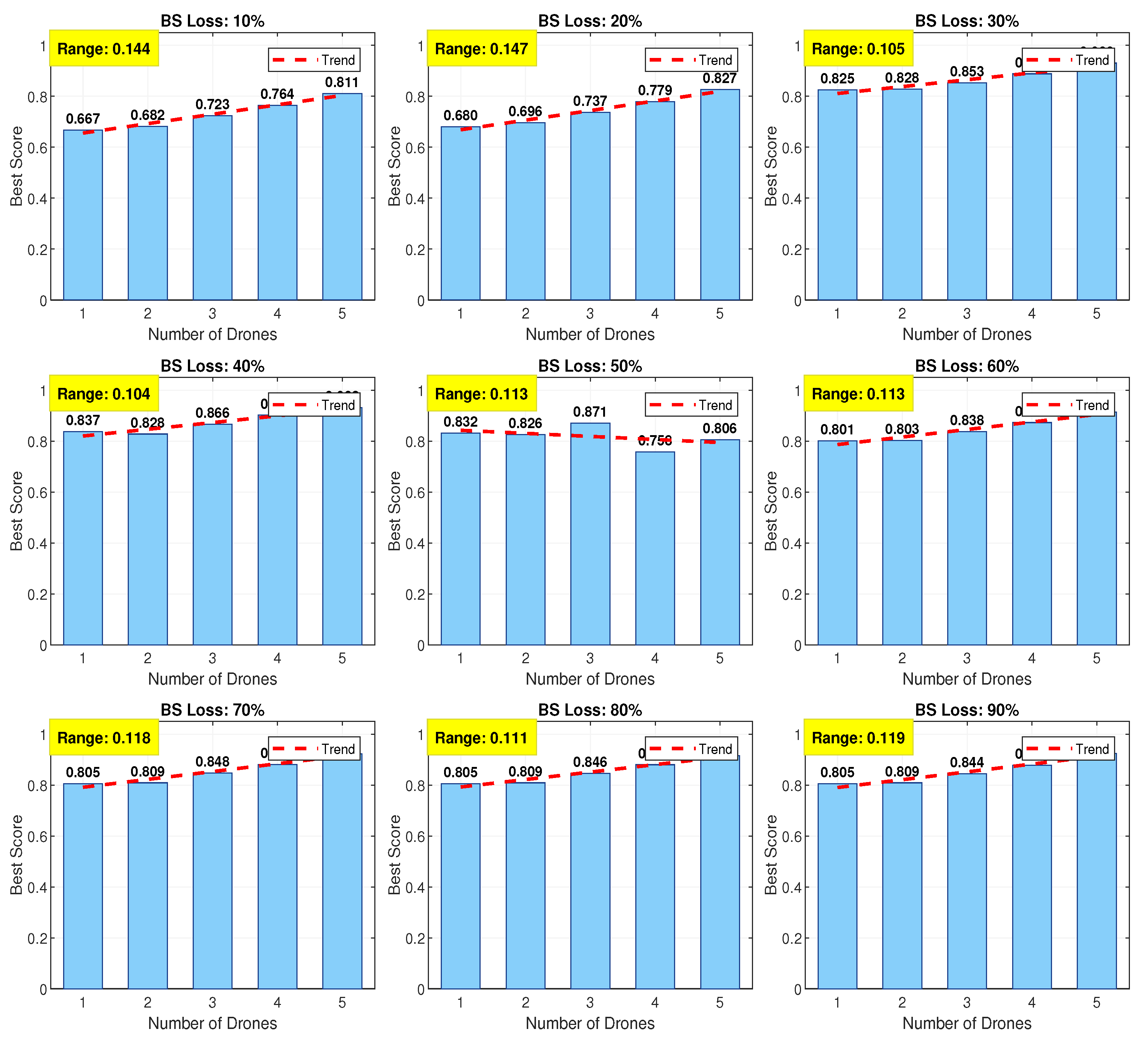

RQ5: How do clustering and optimisation approaches handle varying BS loss, user densities, or terrain constraints in DRNs?

Clustering and Optimisation Approaches in DRNs

To handle varying BS losses, clustering approaches often face challenges due to interference from nodes outside the cluster. To address this, some frameworks allow clusters to exchange optimisation parameters through low-rate backhauls, approaching near-global optimisation performance [

40]. In the case of BS failures, delay-tolerant networks (DTNs) offer resilience by enabling user devices to self-organise and relay messages through multihop connections to functional BSs or nearby users, thereby improving load balancing [

41]. Under sparse BS deployment, users may rely on others who are willing to relay messages to an accessible BS. Optimized beaconing policies are used to maximise message delivery success while minimising power usage [

42]. In high-density scenarios, clustering algorithms such as K-means, DBSCAN, and Agglomerative Clustering were evaluated to determine the most efficient choice. Machine learning (ML) methods can also predict optimal BS parameters, thereby reducing the computational overhead [

43].

The optimization of irregular terrain requires sophisticated modelling. For instance, the Longley-Rice model enables accurate path-loss estimation using high-resolution topographic data [

44]. In urban vehicular DTNs, geographic complexity is managed by segmenting maps into adjacent regions to aid delay analysis and trajectory prediction [

45]. Energy-saving strategies include optimising the activation and deactivation of BS transmissions. Clustering and timed activation approaches help minimise energy use while fulfilling traffic demands [

46]. Battery-aware techniques, such as Improved Lifetime Optimization Clustering (ILCK), apply Kruskal’s minimal spanning tree heuristic and monitor battery health to extend the network lifetime [

47]. Analytical methods, such as convex optimisation, are used to minimise the total transmit power under QoS constraints and are often extended to multi-BS scenarios using iterative algorithms [

48]. Metaheuristic approaches, such as chaotic gorilla troop optimization, enhance energy-aware clustering by considering the neighbor distance, BS proximity, and energy ratio [

49].

Table 6 summarises the strategies for dealing with BS loss, varying user densities, and terrain constraints. Approaches range from DTN routing and ML-based parameter tuning to terrain-aware propagation models and energy-saving BS scheduling. The relevance of the proposed work lies in showing how adaptability to these challenges is crucial (see

Table 6).

These clustering and optimisation techniques collectively address the challenges related to BS loss, varying user densities, and complex terrain in disaster relief networks. By leveraging analytical models, adaptive routing, and energy-aware clustering, these methods can significantly improve the reliability and efficiency of DRNs. The strategies compared in

Table 7 further illustrate how clustering and optimisation methods address BS loss, varying user densities, and terrain constraints in DRNs. By juxtaposing their benefits and limitations, the table highlights that adaptability and energy-awareness are the most critical enablers for post-disaster UAV deployments.

To provide a broader perspective,

Table 8 consolidates the methods examined across all five research questions (RQ1–RQ5). This summary highlights how clustering, learning-based optimisation, and hybrid strategies collectively contribute to improving UAV service coverage, path efficiency, and resilience in disaster response networks.

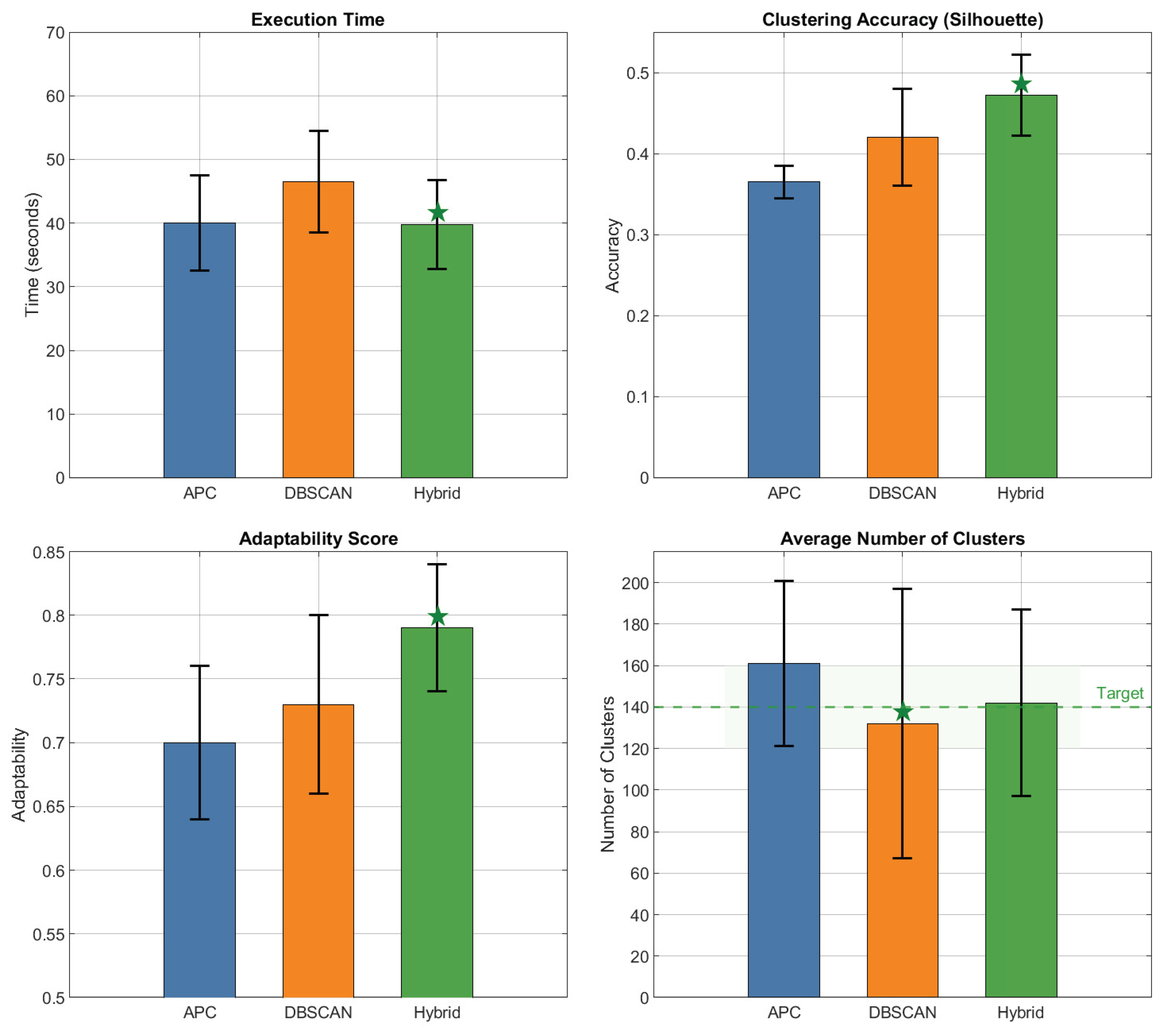

3. Environment Modelling

This section outlines the key assumptions and system architecture of the studied UAV-assisted emergency network deployment in post-disaster scenarios. The objective is to provide resilient and rapid connectivity to UEs through the deployment of MABSs using a newly proposed hybrid clustering-based optimisation framework. The proposed solution enhances the previous work [

50] by dynamically selecting between APC and a learned clustering strategy that combines DBSCAN with an ANN. This hybrid model enables more flexible and adaptive UAV path planning depending on the network density, terrain, and disaster impact levels.

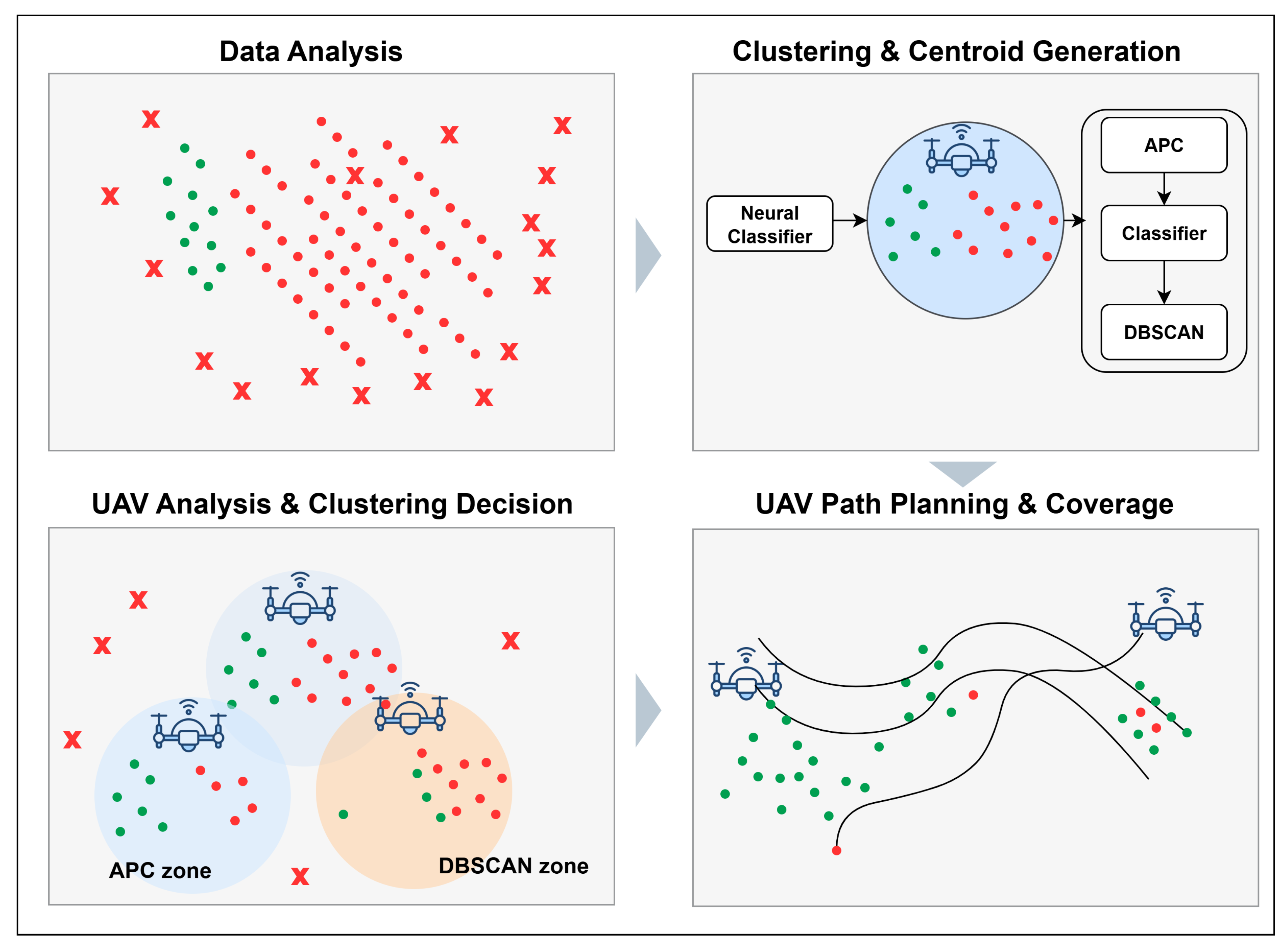

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed system model, which offers an intelligent and resilient solution for restoring wireless connectivity in post-disaster environments in which conventional base stations have failed. UAVs are used as MABSs to provide temporary coverage to disconnected UEs. The green markers indicate UEs with active services, whereas the red markers indicate UEs that have lost connectivity and require temporary MABS coverage. Each MABS follows an optimised trajectory to visit the centroid of the user clusters.

The process begins with the identification of failed base station zones and the classification of the UEs as either connected or disconnected. Spatial features, such as UE density, base station outage levels, and distribution spread, are then extracted and fed into a lightweight neural classifier. This classifier dynamically selects the optimal clustering method by choosing either APC for dense, structured regions or DBSCAN with ANN-guided parameter tuning for sparse or irregular topologies. This hybrid selection process enables more accurate and adaptive clustering, thereby ensuring efficient centroid placement. These centroids serve as UAV visitation points and are further processed by a GA that optimises the UAV trajectories based on multi-objective criteria, including service ratio, smoothness, and overlap avoidance.

The hybrid model’s ability to adapt to varying UE distributions and disaster intensities, combined with machine-learning-driven decision-making, makes it a robust and scalable framework for real-time UAV-assisted communication restoration. The adaptability of the system was further enhanced by incorporating real-time data updates, allowing for dynamic reclustering and trajectory adjustments as the post-disaster scenario evolved. This continuous optimisation ensures that the UAV network remains responsive to changing ground conditions, such as shifting UE concentrations or newly restored BSs.

In this extended model, the cluster centroids were computed using a decision layer selected between APC and DBSCAN+ANN, depending on the real-time conditions. Moreover, the framework includes a predictive component that anticipates potential changes in the UE distribution based on historical patterns and current movement trends, enabling proactive UAV positioning for improved service continuity.

3.1. Clustering Mode Selection

The novel contribution of this study is the dynamic selection of a clustering method for identifying UAV visitation centroids. This logic is defined as follows:

Table 9.

Clustering selection logic based on UE distribution.

Table 9.

Clustering selection logic based on UE distribution.

| Condition |

Selected Clustering Method |

| High UE density |

APC |

| Low UE density or sparse regions |

DBSCAN with ANN-guided parameter tuning |

| Unstructured or mixed topology |

ANN-only centroid prediction |

The ANN model was pretrained on synthetic post-disaster UE distributions to predict the optimal clustering configurations. When used with DBSCAN, the ANN adjusts the clustering parameters (e.g., and MinPts) or refines the centroid locations to minimize misclustering in sparse environments.

3.2. Simulation Setup and Parameters

Table 10.

Simulation Parameters and Settings.

Table 10.

Simulation Parameters and Settings.

| Notation |

Description |

Value |

| U |

Number of UEs |

2500 |

|

BS Distribution (Poisson) |

|

| A |

Area |

25 km × 25 km |

| D |

Number of MABS |

1 to 5 |

| S |

GA Population Size |

50 |

| P |

GA Iterations |

100 |

|

Clustering Logic Mode |

Hybrid (APC, DBSCAN+ANN) |

| ANNmodel

|

Neural Model Enabled |

True |

|

BS Outage Percentage |

10% to 90% |

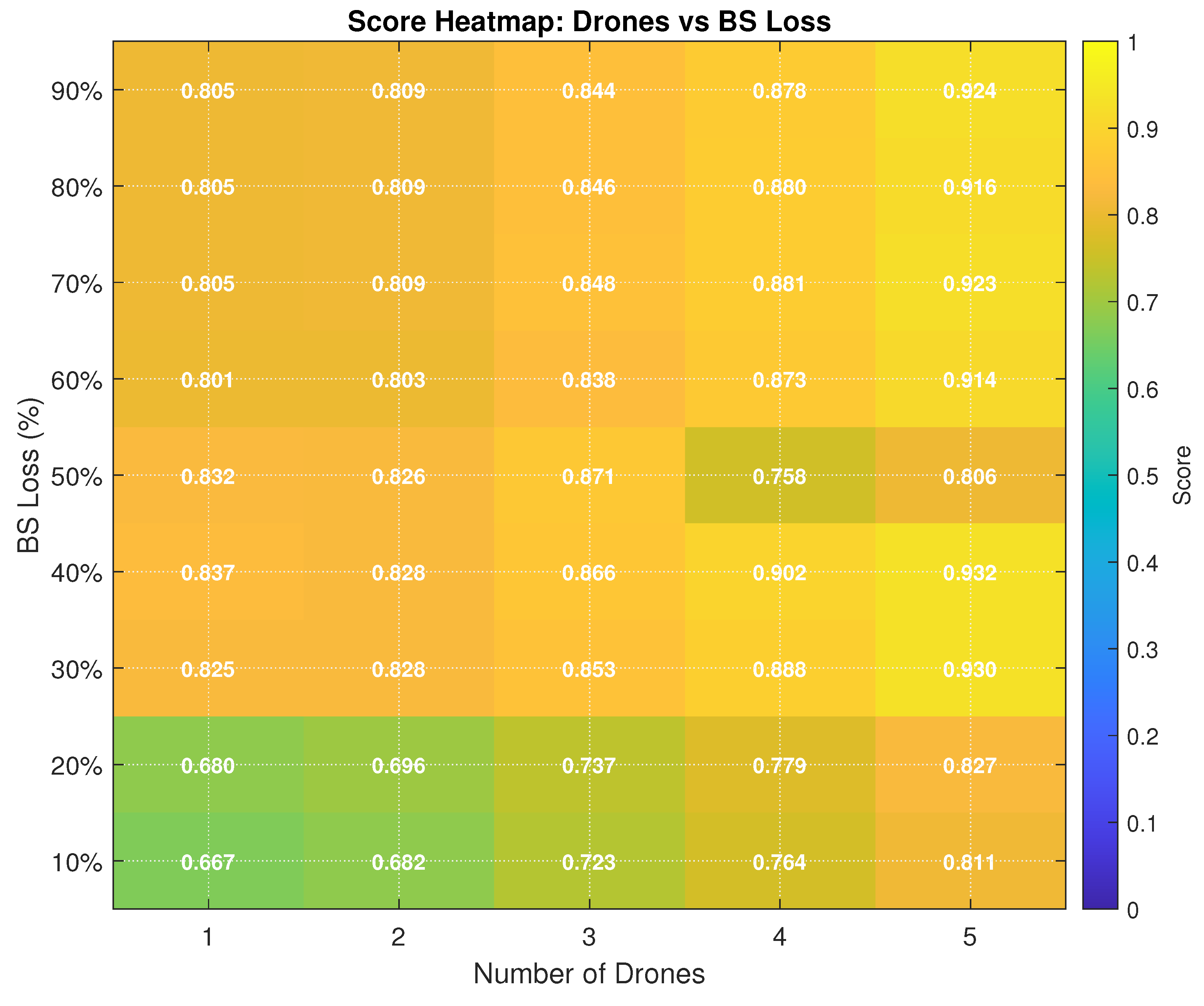

The simulation emulates a

km

2 area, representing a mid-sized town. The UE and BS locations follow a Poisson distribution with

and

, respectively. Each UE requires a minimum bandwidth of 200 kbps. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and link capacity are estimated using the Shannon–Hartley theorem as follows:

and

represent the desired and interfering signal powers, respectively.

is the noise set to

dBm. The transmission powers were 46 dBm (BS), 30 dBm (MABS), and 10 dBm (UE). Path loss was calculated using the Okumura–Hata model as follows:

3.3. Clustering Algorithm Integration

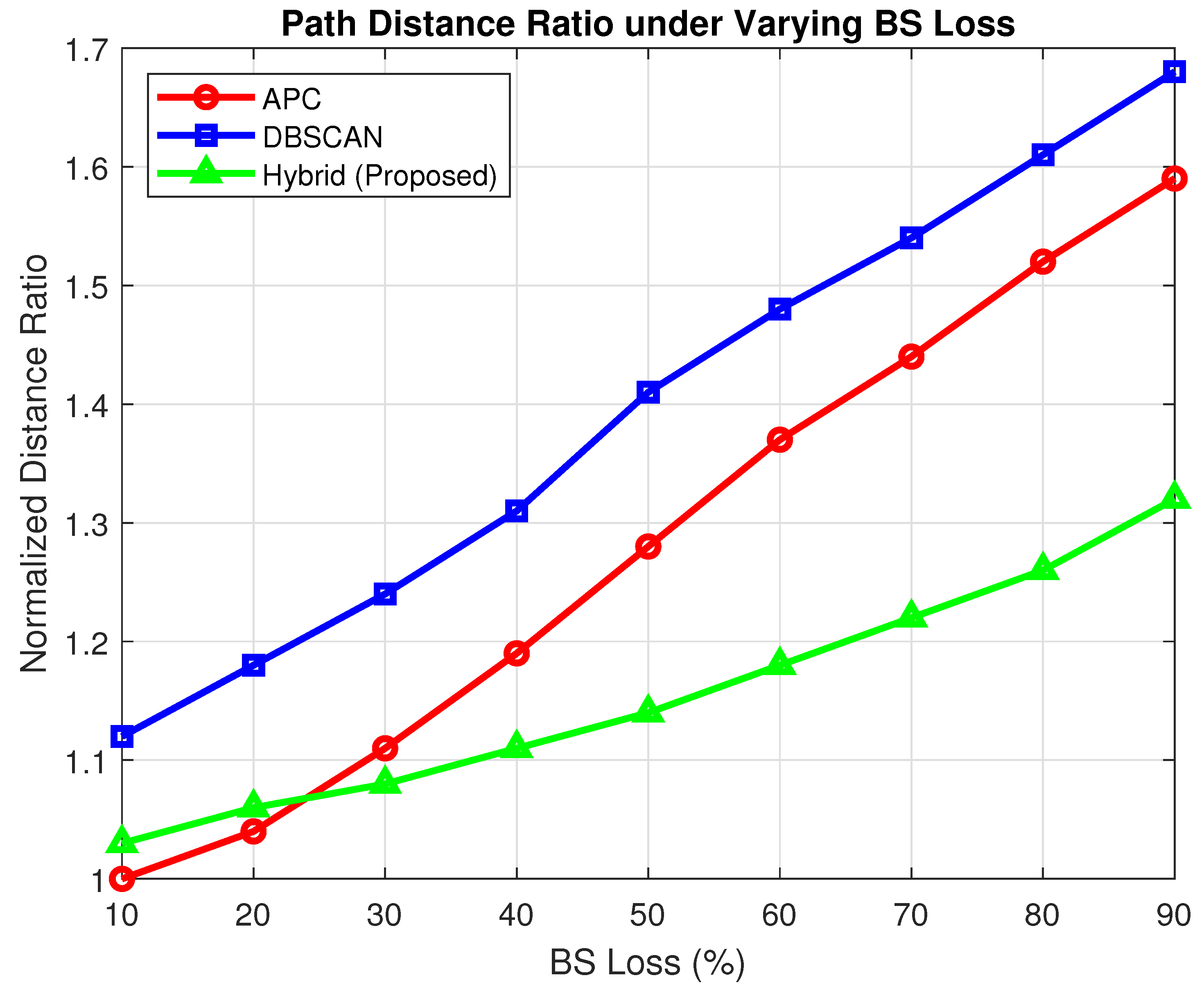

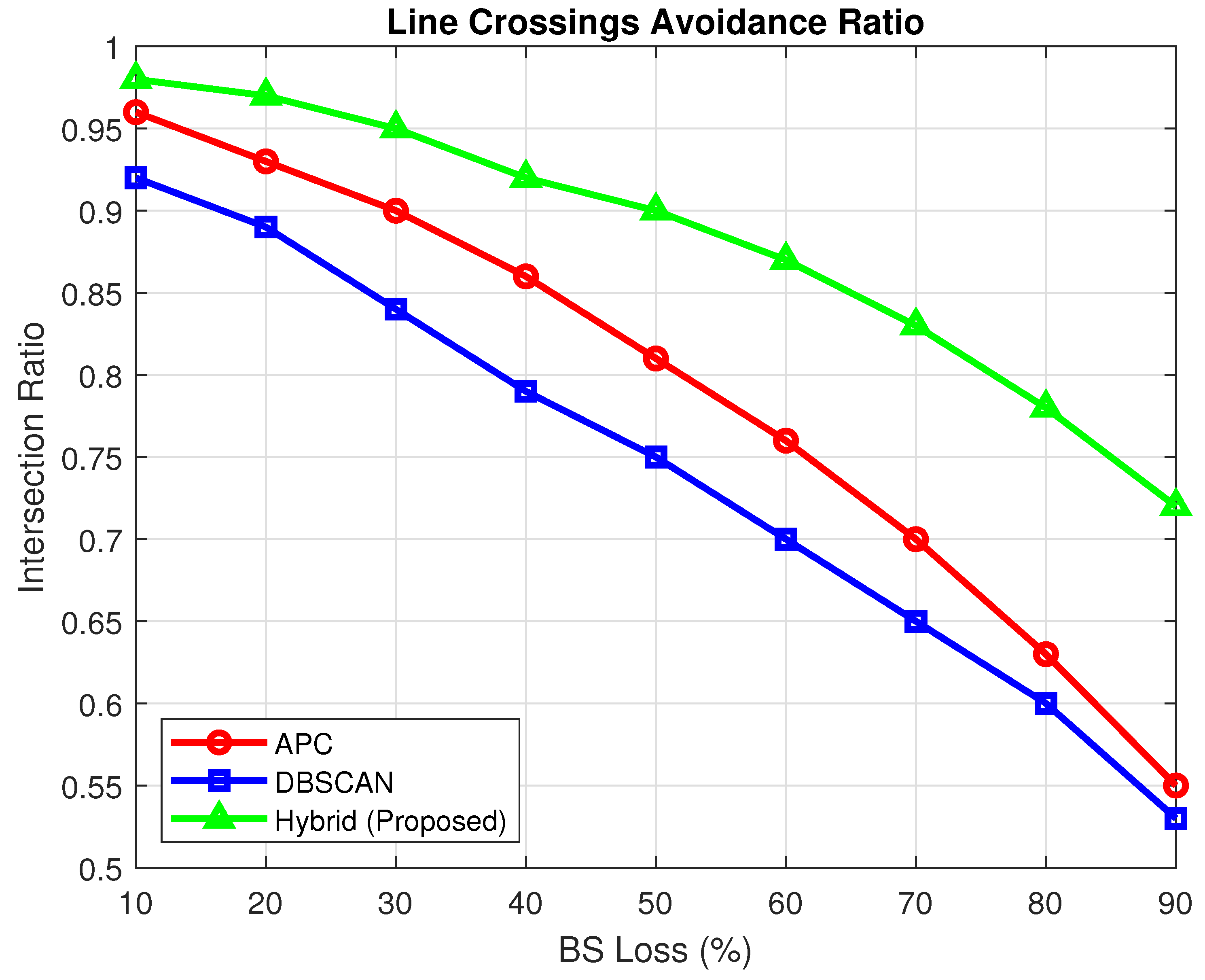

For each level of BS outage (10% to 90%), the hybrid clustering model selectes the most suitable strategy. If the ANN recommends an APC, traditional cluster propagation is applied; otherwise, DBSCAN with ANN-guided parameter tuning generates adaptive centroids. These centroids act as waypoints for UAVs during subsequent genetic optimisation.

A damping factor of 0.6 was used for APC, whereas and MinPts in DBSCAN were adapted dynamically. The output centroids vary according to the sparsity of the network, the distribution of services, and the distance traveled.

3.4. Hybrid Clustering Strategy for UAV-Based UE Grouping

The hybrid clustering strategy described in this study is a neural-guided adaptive framework that dynamically selects between APC and DBSCAN based on the spatial characteristics of the UE distributions. This decision was driven by a lightweight neural network classifier.

Stage 2: Neural Classifier-Based Clustering Selection

Objective: Use a trained neural model to decide between APC and DBSCAN.

where: is the input feature vector, , are trainable weights and biases, and : 0 = APC, 1 = DBSCAN (possibly with ANN refinement).

Stage 3: Clustering Execution

Case A: If APC is selected

Case B: If DBSCAN is selected

Parameters:: neighborhood radius, and MinPts: minimum number of points to form a cluster. Definitions: Core point: and Directly density-reachable: .

An ANN can refine the centroid locations or tune the clustering parameters and MinPts dynamically.

Stage 4: Centroid Generation for UAV Routing

Cluster centroids are computed as:

where

is the

kth cluster.

Table 11.

Summary of the hybrid clustering process for UAV deployment.

Table 11.

Summary of the hybrid clustering process for UAV deployment.

| Stage |

Description |

Output |

| 1 |

Extract UE spatial features |

Feature vector

|

| 2 |

Neural classifier decision |

APC or DBSCAN |

| 3 |

Apply selected clustering |

Cluster centroids |

| 4 |

Generate centroids |

|

| 5 |

Feed into GA path planning |

Optimized UAV routes |