1. Introduction

Different regulatory mechanisms are crucial for the maintenance of distinct NBs and are also important for the overall homeostasis of brain development. Neural stem cells are a type of cells generating neurons or glial cells, which compose the central nervous system (CNS) [

1,

2]. Excessive proliferation of neural stem cells may induce the onset of malignancies, whereas insufficient division of neural stem cells can lead to neurodevelopmental defects [

3,

4]. Mammalian neural stem cells exhibit various division modes, and the division modes of type I and type II neural stem cells (neuroblasts, NBs) [

5] in

Drosophila are analogous to two of these modes in

mammals [

1,

6]. Therefore,

Drosophila NBs serve as an excellent model for studying neural stem cells. The

Drosophila central brain NBs are primarily categorized into two types: type I and type II NBs [

7].

Drosophila NBs originate during embryogenesis, and by the third instar larval stage, there are eight type II NBs per hemisphere, a number that is significantly smaller than the approximately 90 type I NBs [

8,

9]. In addition, the progeny cells produced by the two types of NBs differ. Type II NBs generate another NB and an intermediate neural progenitor (INP), which undergoes a limited number of division cycles before differentiating into a ganglion mother cell (GMC), while type I NBs give rise to another NB and a ganglion mother cell (GMC), which subsequently produces neurons or glial cells [

1,

7]. Different types of neural stem cells produce varying numbers of progeny and contribute to distinct brain structures [

10,

11,

12,

13]. For example, type II NBs can generate numerous progeny cells that contribute to the formation of the central complex of the

Drosophila central brain, or to the optic lobe by producing glial cells which differentiate into lobular giant glial cells [

1,

8,

9,

10,

12]. In addition to the aforementioned differences, type I and type II NBs also express distinct molecular markers. Asense (Ase) is specifically expressed in type I NBs, but not in type II NBs, whereas Pntp1 (Pnt) is exclusively expressed in type II NBs [

14,

15]. Many studies have reported the different maintenance mechanisms of type I and type II NBs. For example,

Six4 can specifically inhibit the premature differentiation of INPs [

16]. However, it remains unclear whether there are other unknown specific regulatory factors that affect different types of NBs. The process by which type II NBs generate INPs is analogous to that of higher mammalian NSCs, making type II NBs an excellent model for studying the maintenance of neural stem cells [

17,

18]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the mechanisms involved in maintaining

Drosophila type II NBs specifically.

It has been reported that ectopic activation of Notch signaling leads to over-proliferation and an increase in ectopic NBs, which appears to be more pronounced in type II NBs [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The mechanism by which the Notch signaling pathway exerts its effects through cleavage is conserved. Upon binding of the Notch receptor to ligands secreted by adjacent cells, a series of cleavage events occurs, resulting in the generation of the active form, Notch

NICD (Notch intracellular domain, NICD). Notch

NICD subsequently translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it activates the expression of downstream Notch target genes [

23,

24]. During the activation of the Notch signaling pathway, numerous factors regulate this process. For example, the mammalian SHARP functions as a co-repressor recruited by RBP-J. In the absence of Notch

NICD, SHARP and RBP-J bind to DNA, thereby repressing the expression of downstream target genes [

24,

25,

26]. This process is mediated by HAIRLESS (H) in

Drosophila, however, no homologous protein has been identified in

mammals [

24,

27]. Although many regulatory factors have been reported, it remains unclear whether there are other regulatory factors of Notch signaling pathway and whether multiple co-repressors exist to coordinately regulate the Notch signaling pathway in

Drosophila type II NBs. Therefore, investigating new regulatory factors of the Notch signaling pathway is crucial for the maintenance of type II NBs.

S

plit ends (spen) (also called MINT in mice and SHARP in human [

28,

29]) plays an important role in regulating gene expression and tissue development. SHARP, as a transcriptional co-repressor, can combine to chromatin-remolding complexes or physically associate with the nuclear receptor components [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. The biological functions of SPEN include promoting cilia formation, maintaining middle glial cell fate, and regulating various other processes [

35,

36,

37]. In addition,

spen is involved in multiple signaling pathways that collectively regulate tissue growth and development [

38,

39,

40,

41]. For example, during

Drosophila eye development, the absence of

spen results in ectopic activation of Notch signaling, and this aberrant activation subsequently diminishes the activity of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway, ultimately leading to the disruption of adult eye morphology [

41]. However, the role of

spen in

Drosophila NBs is currently unclear, and the relationship between Notch signaling pathway in

Drosophila type II NBs remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether multiple signaling pathways collaborate to exert their effects in

Drosophila NBs, and whether SPEN plays a critical regulatory role in NBs.

In this study, we find that SPEN can prevent the generation of supernumerary type II NBs but does not affect the number of type I NBs. Moreover, we identify that the specific role of spen in type II NBs is mediated by the inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway, which prevents the dedifferentiation of imINPs. In addition, we also find that knockdown of both spen and Hairless can enhance the phenotype resulting from knockdown of spen alone in type II NBs. Furthermore, in imINPs, Hairless and spen appear to play distinct roles. The reduction of the EGFR signaling pathway can partially rescue the increase in type II NBs caused by spen. Therefore, our experiments highlight that spen functions as a novel regulatory factor of Notch signaling in Drosophila to prevent the generation of supernumerary type II NBs specifically. This regulatory role suggests that spen, like Hairless, may function as a homolog of mammalian sharp.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drosophila Stocks and Genetics

Flies were raised at 25 ℃, and mated at 29 ℃. The GAL4 strains involved in this paper included: UAS-Dicer2; wor-GAL4, ase-GAL80, UAS-mCD8-GFP; + (II NB-GAL4), w; ase-GAL4; UAS-Dicer2, w; UAS-Dicer2; PntP1-GAL4, UAS-mCD8-GFP (pnt NB-GAL4),w;UAS-mCD8-GFP;UAS-Dicer2, 9D11-GAL4(9D11 mINP-GAL4), w; UAS-LacZ, 9D10-GAL4 (9D10 mINP-GAL4);sb/Tm6B, Repo-GAL4/Tm6B, Elav-GAL4.The other strains involved in this paper included: UAS-spen RNAi (Tsing Hua Fly Center THU0750), UAS-spen RNAi (Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC) 108801, P{KK100153}VIE-260B), UAS-spen RNAi (V49542,w1118; P{GD16317}v49542, gift from Li Hua Jin), UAS-spen RNAi (v48846, gift from Li Hua Jin), UAS-spen (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) 20756,y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}spenEY12567), UAS-luciferase (BDSC35788, P{UAS-LUC.VALIUM10}attP2), UAS-LacZ RNAi (V51446), UAS-Notch RNAi (THU0549), UAS-Notch RNAi (BDSC33611, P{TRiP.HMS00001}attP2), w; +; E(spl) mg-GFP (gift from Yan Song), UAS-Egfr RNAi (THU1863, THU1864), UAS-Egfr CA (BDSC9533, BDSC9534), UAS-hairless RNAi (THU3690), UAS-hairless RNAi (v24466), UAS-Arm RNAi (THU1631), UAS-Ctbp RNAi (THU1078), UAS-Ctbp RNAi (THU1919), UAS-Brat (B13860).

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Third larval brains were dissected, and then they were incubated in 4%paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. Samples were washed with 0.3%PBST for 4 times and subsequently blocked by 2% BSA for 1 hour. Samples were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies. The samples were washed with 0.3% PBST for 4 times, then the secondary antibody was incubated for 2 hours, and the secondary antibody was finally washed off. Finally, the tissues were observed with Zeiss LSM700 and Zeiss LSM900 confocal microscopes. The following primary antibodies were used in this paper: Chicken polyclonal anti-GFP (1:1000, Cat# A10262, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Rat monoclonal anti-Miranda (1:1000, Cat#ab197788, Abcam), Rat monoclonal anti-Dpn (1:1000, Cat# ab195173; Abcam), Rabbit polyclonal anti-PH3 (1:100, Cat# 9701, Cell Signaling Technology), Rat anti-Elav (1:50, Cat# 9F8A9, DSHB), Rabbit anti-Ase (Serum antibodies constructed by the laboratory), Mouse anti- PKC ζ (1:50, Cat#177781, Santa Cruz), anti-α tublin (1:100, cat#ab7291, Abcam), Mouse anti-NICD (1:50,cat#C17.9C6, DSHB). Mouse anti-NECD (1:50, cat#C458.2H, DSHB) Rabbit anti-mcherry (1:10, Cat#ab213511, Abcam)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Fluorescence intensity analysis was performed on samples under consistent background conditions using ImageJ software. Fluorescence intensity and other statistical data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). The total number of animals, p-values, and significance levels were indicated in the figure legends.

4. Discussion

Different neural stem cells produce varying numbers of progeny cells to maintain normal brain development, making it crucial to investigate the factors that regulate the development of distinct neural stem cell populations. Given that the progeny production pattern of

Drosophila type II NBs is similar to that of

higher mammals, investigating new factors involved in maintaining

Drosophila type II NBs could provide insights for future studies on the maintenance of neural stem cells in higher mammals. Although factors regulating different NBs in

Drosophila have been reported, it remains unclear whether there are additional and important factors yet to be discovered. In this article, we found that

spen knockdown leads to an increase in the number of type II NBs by inhibiting the Notch

NICD level to prevent the dedifferentiation of imINP (

Figure 7). This phenotype specifically occurs in type II NBs, and is not present in type I NBs, neurons, or glial cells. Although

spen has been investigated in various

Drosophila tissues, including the eyes, intestinal stem cells, and glial cells [

14,

30,

32], its specific function in

Drosophila NBs has remained unclear. Our study provides additional insights into the role of

spen in the maintenance of type II NBs.

In

Drosophila, Hairless is known as a co-repressor of the Notch signaling pathway, recruiting factors such as CtBP to collectively inhibit Notch signaling [

27,

57]. However, in

mammals, there is no homolog of

Hairless, and thus this process is carried out by the

Drosophila spen homolog,

sharp [

24,

53]. Some studies have suggested that

Drosophila spen may not functionally correspond to mammalian

sharp [

53]. Our experimental results indicate that the concomitant knockdown of

spen and

Hairless results in a greater increase of type II NBs compared to the individual knockdown of either

spen or

Hairless. Furthermore, the phenotype resulting from the knockdown of

spen is noticeably more pronounced than that from the knockdown of

Hairless, suggesting that

spen may play a more critical role than

Hairless. Based on our findings regarding the mechanism by which

spen inhibits Notch signaling, we propose that

spen and

Hairless may function together as co-repressors. While the binding of mammalian SHARP to RBP-J has been reported, the interaction of

spen as a co-repressor with the

Drosophila RBP-J homolog su(H) also requires investigation. This will be the focus of our future work, as we aim to provide more definitive evidence for the existence of two distinct co-repressors in

Drosophila type II NBs. The presence of these two different co-repressors within the same lineage raises questions about their functional roles—possibly exerting different effects in distinct cell types? Our research indicates that the knockdown of

spen in type II NBs or imINPs leads to a specific increase in type II NBs, while

Hairless appears to function solely within type II NBs. This phenotype may be due to that

spen and

Hairless regulate distinct Notch downstream target genes, which is another avenue for our future exploration. In addition, it will be an intriguing area of future research to investigate when HAIRLESS begins to disappear in various species and how its function is gradually replaced by SHARP.

spen has been reported to influence diseases by modulating signaling pathways. For instance,

spen can regulate nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) by maintaining the levels of PI3K/AKT and c-JUN [

40]. And in

Drosophila tissues, different signaling pathways often work together to regulate development. Our study shows that during the third instar larval stage, not only is the Notch signaling pathway crucial for the development of type II NBs, but the Egfr signaling pathway also plays a role in maintaining the number of NBs. This effect is mediated exclusively by SPEN. Studying the regulation of type II NBs development by different signaling pathways is crucial for maintaining the number of type II NBs. However, the mechanisms by which these two signaling pathways collaboratively regulate each other remain unclear. In the future, we will pursue this as our research objective, aiming to target

spen in order to specifically modulate the interactions between different signaling pathways, with the goal of addressing related diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z., F.Z., M.R and S.W.; methodology, Q.Z., F.Z., S.G., S.Z., W.G., M.R and S.W.; formal analysis, Q.Z., F.Z. and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z.,M.R and S.W.; performing experiments: Q.Z. and F.Z.; funding acquisition, M.R and S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

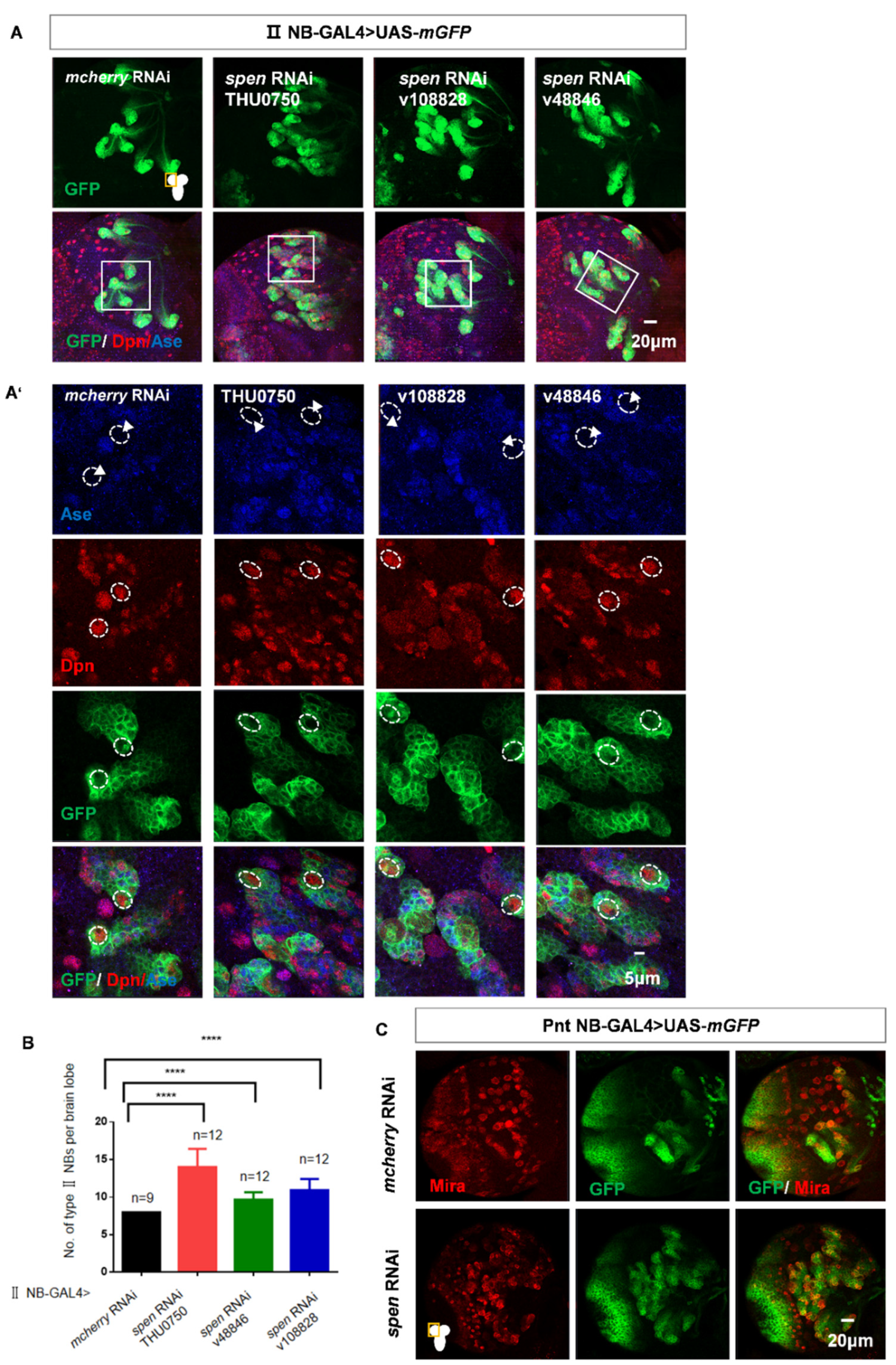

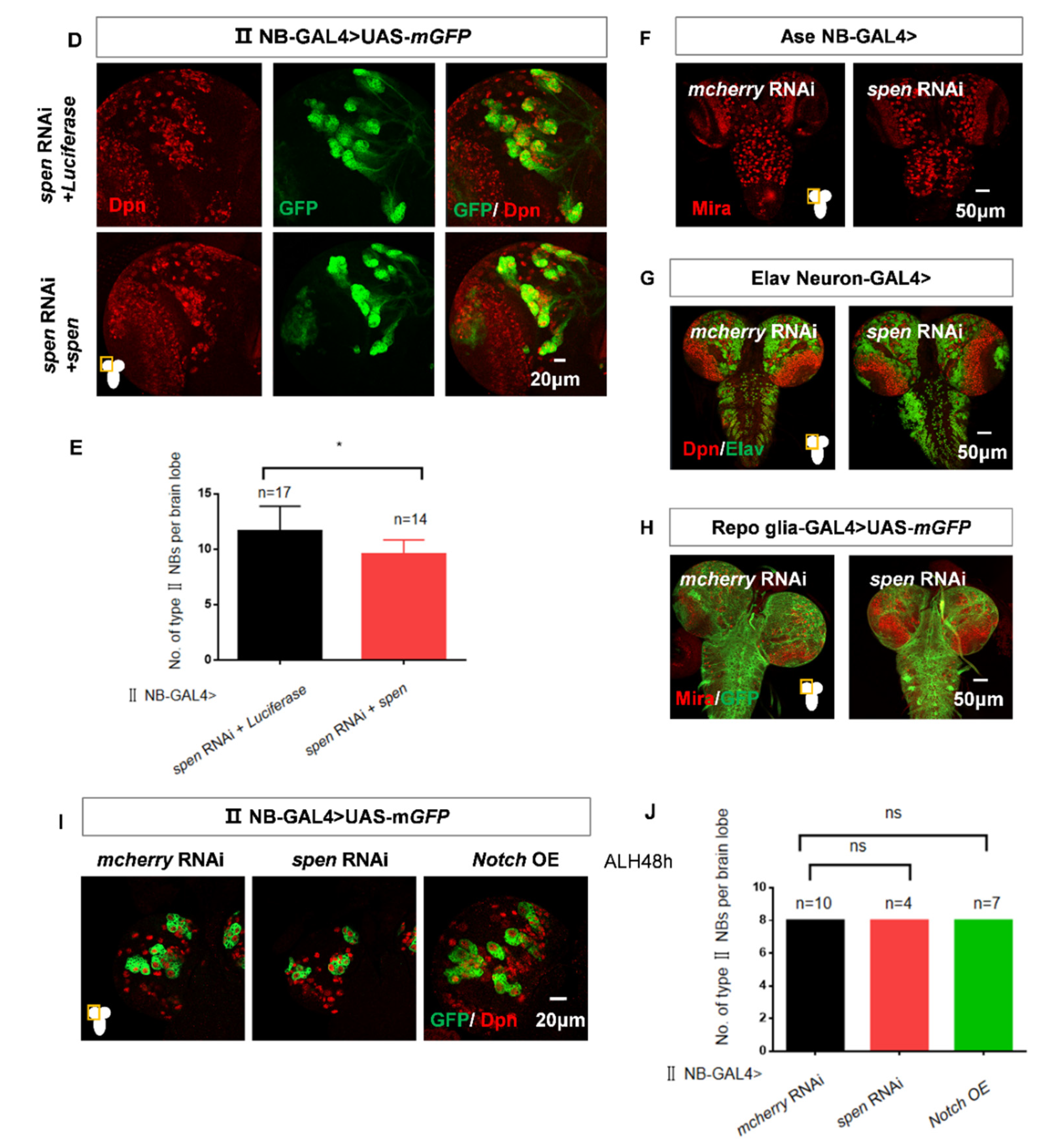

Figure 1.

spen knockdown leads to an increased number of type II NBs specifically. (A) Utilizing type II NB-GAL4 to knock down different spen RNAi lines consistently resulted in an increase in type II NBs. (A’) showed type II NB lineages which were labeled by GFP, Dpn, and Ase (white arrowhead) in (A). (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (A). Mean ± SEM ****P<0.0001. (C) Knocking down spen by Pnt-GAL4 also induced the increase number of type II NBs. (D-E) Overexpression spen in a background where spen was knocked down can partially rescue the number of ectopic type II NBs, and (E) showed quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe. Mean ± SEM, *P<0.05. (F-H) Knocking down spen in type I NBs by Ase-GAL4 (F) and in neurons by Elav-GAL4 (G) and in pan-glial cells by Repo-GAL4(H) resulted in no obvious effect on the whole brain size and NBs. (I-J) At ALH48h, the number of type II NBs had no obvious change in spen knockdown and Notch overexpressing flies. (J) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (I), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. Mira or Dpn represented NBs in all results. Elav showed neuronal cells in G, and GFP showed the structure of glial cells in H. All brains were obtained from third-instar larvae. Type II NB lineages are labeled by GFP, Dpn.

Figure 1.

spen knockdown leads to an increased number of type II NBs specifically. (A) Utilizing type II NB-GAL4 to knock down different spen RNAi lines consistently resulted in an increase in type II NBs. (A’) showed type II NB lineages which were labeled by GFP, Dpn, and Ase (white arrowhead) in (A). (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (A). Mean ± SEM ****P<0.0001. (C) Knocking down spen by Pnt-GAL4 also induced the increase number of type II NBs. (D-E) Overexpression spen in a background where spen was knocked down can partially rescue the number of ectopic type II NBs, and (E) showed quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe. Mean ± SEM, *P<0.05. (F-H) Knocking down spen in type I NBs by Ase-GAL4 (F) and in neurons by Elav-GAL4 (G) and in pan-glial cells by Repo-GAL4(H) resulted in no obvious effect on the whole brain size and NBs. (I-J) At ALH48h, the number of type II NBs had no obvious change in spen knockdown and Notch overexpressing flies. (J) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (I), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. Mira or Dpn represented NBs in all results. Elav showed neuronal cells in G, and GFP showed the structure of glial cells in H. All brains were obtained from third-instar larvae. Type II NB lineages are labeled by GFP, Dpn.

Figure 2.

spen knockdown induces imINP dedifferentiate into type II NBs. (A-C) spen knockdown induced the Dpn+ Pnt+ (NB) cells number increase (white arrowhead) and Dpn+ Pnt- (imINP) cells decrease. (B) Quantification of Dpn+ Pnt+ (NB) cells number per II NB lineage from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. (C) Quantification of Dpn+ Pnt- (imINP) cells number per II NB lineage from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. (D-E) Knocking spen down by 9D10 GAL4 induced the type II NBs number increase. (E) Quantification of type II NBs number (Ase-Dpn+ cells, white arrowhead) per brain lobe was shown in figure (D). Mean ± SEM , ***P<0.001. (F-G) spen defect in mINPs had no effect on the number of NBs. (G) Quantification of NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (F), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A. LacZ marked imINPs and their lineages in D.

Figure 2.

spen knockdown induces imINP dedifferentiate into type II NBs. (A-C) spen knockdown induced the Dpn+ Pnt+ (NB) cells number increase (white arrowhead) and Dpn+ Pnt- (imINP) cells decrease. (B) Quantification of Dpn+ Pnt+ (NB) cells number per II NB lineage from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. (C) Quantification of Dpn+ Pnt- (imINP) cells number per II NB lineage from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. (D-E) Knocking spen down by 9D10 GAL4 induced the type II NBs number increase. (E) Quantification of type II NBs number (Ase-Dpn+ cells, white arrowhead) per brain lobe was shown in figure (D). Mean ± SEM , ***P<0.001. (F-G) spen defect in mINPs had no effect on the number of NBs. (G) Quantification of NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (F), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A. LacZ marked imINPs and their lineages in D.

Figure 3.

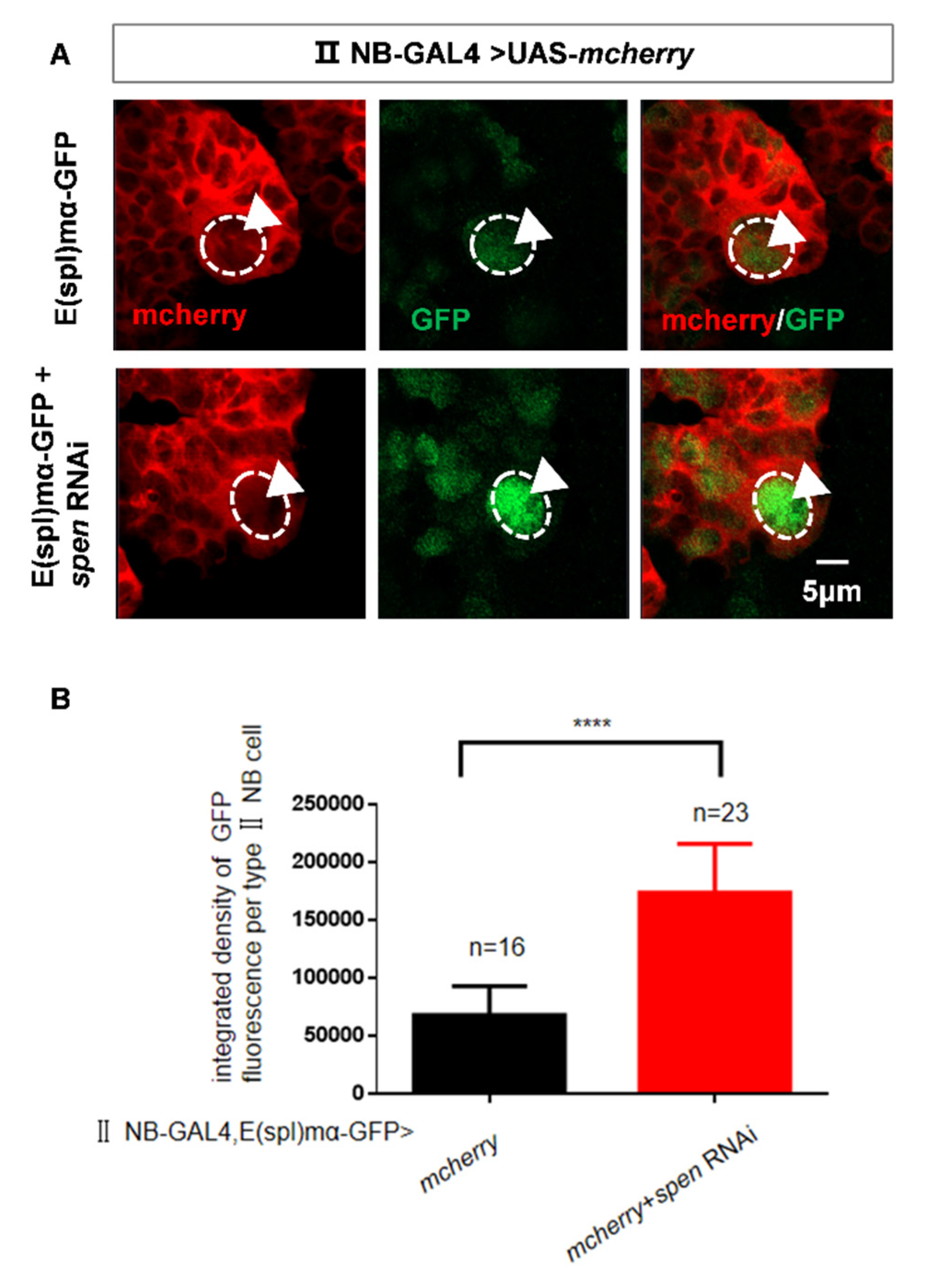

spen knockdown can activate the Notch signaling pathway. (A-B) The content of E(spl)mα in spen defect brains increased (white arrowhead). (B) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of E(spl)mα-GFP in a single type II NB from genotypes in (A). ****P<0.0001. (C-D) Double knockdown of spen and notch (B33611) rescued the increasing type II NBs number compared to knockdown of spen and lacZ. (D) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (C). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in C; Mcherry marked type II NBs in A.

Figure 3.

spen knockdown can activate the Notch signaling pathway. (A-B) The content of E(spl)mα in spen defect brains increased (white arrowhead). (B) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of E(spl)mα-GFP in a single type II NB from genotypes in (A). ****P<0.0001. (C-D) Double knockdown of spen and notch (B33611) rescued the increasing type II NBs number compared to knockdown of spen and lacZ. (D) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (C). Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in C; Mcherry marked type II NBs in A.

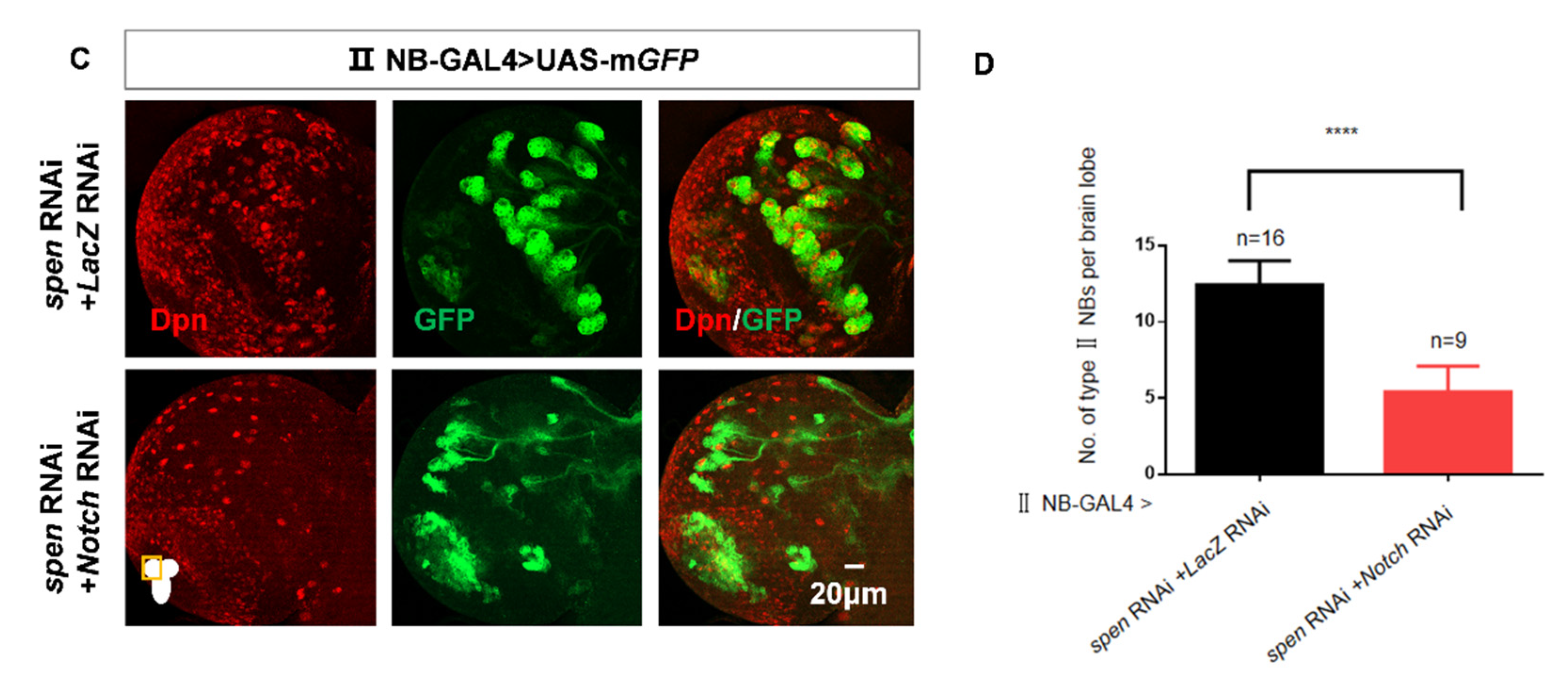

Figure 4.

spen knockdown promotes nuclear NICD level in Drosophila. (A) The fluorescence of NICD increased in spen knockdown brains. (B) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of NICD in type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (A). ****P<0.0001. (C-D) The fluorescence of NECD had no difference in spen knockdown brains. (D) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of NECD in type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (C), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. (E-F) Brat overexpression in the background of spen knockdown could not downregulate the NICD level compared to control. (F) Quantification of NICD level in per type II NB from genotypes in (E), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A, C, and E..

Figure 4.

spen knockdown promotes nuclear NICD level in Drosophila. (A) The fluorescence of NICD increased in spen knockdown brains. (B) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of NICD in type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (A). ****P<0.0001. (C-D) The fluorescence of NECD had no difference in spen knockdown brains. (D) Quantification of fluorescence integrated density of NECD in type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (C), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. (E-F) Brat overexpression in the background of spen knockdown could not downregulate the NICD level compared to control. (F) Quantification of NICD level in per type II NB from genotypes in (E), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A, C, and E..

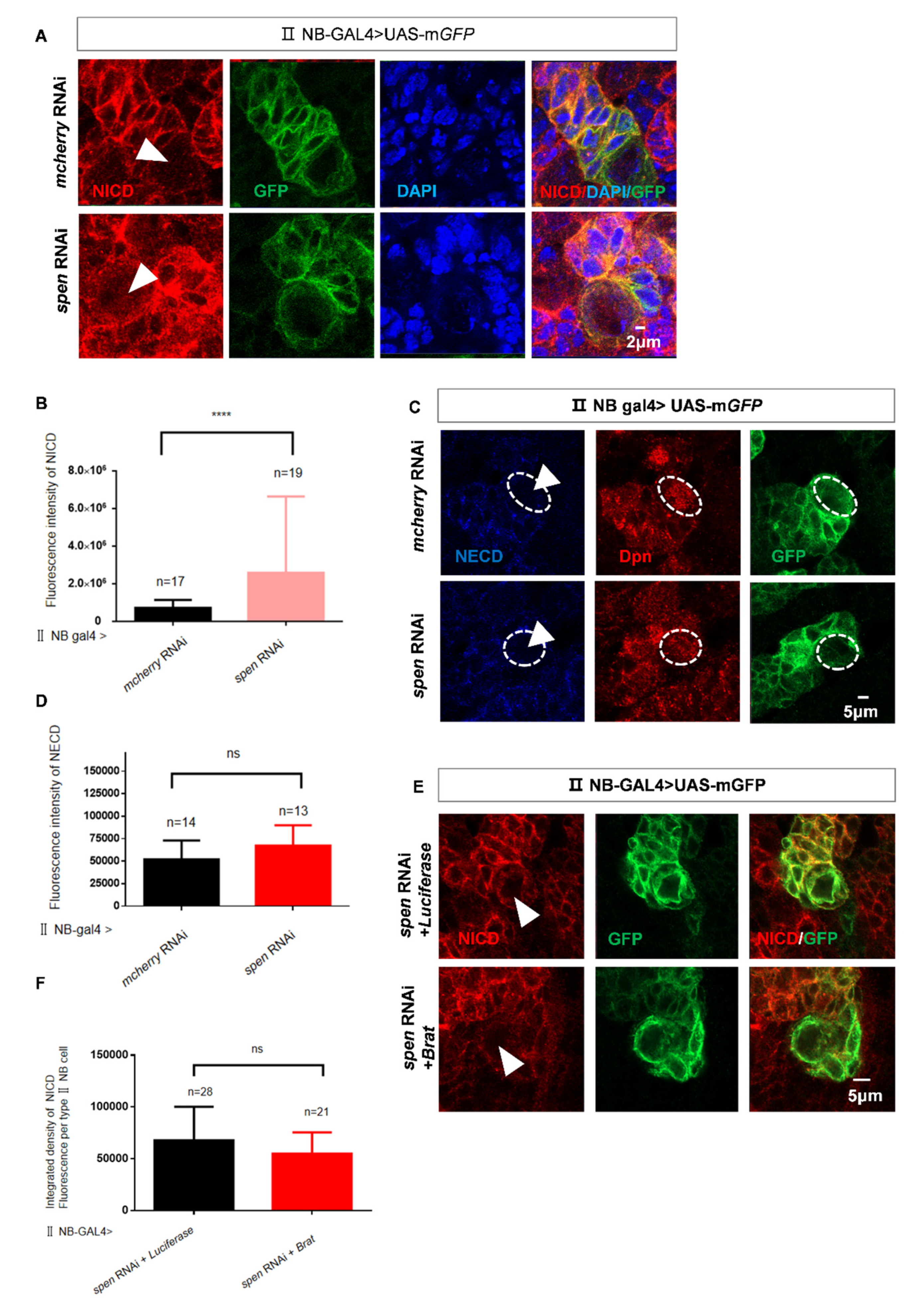

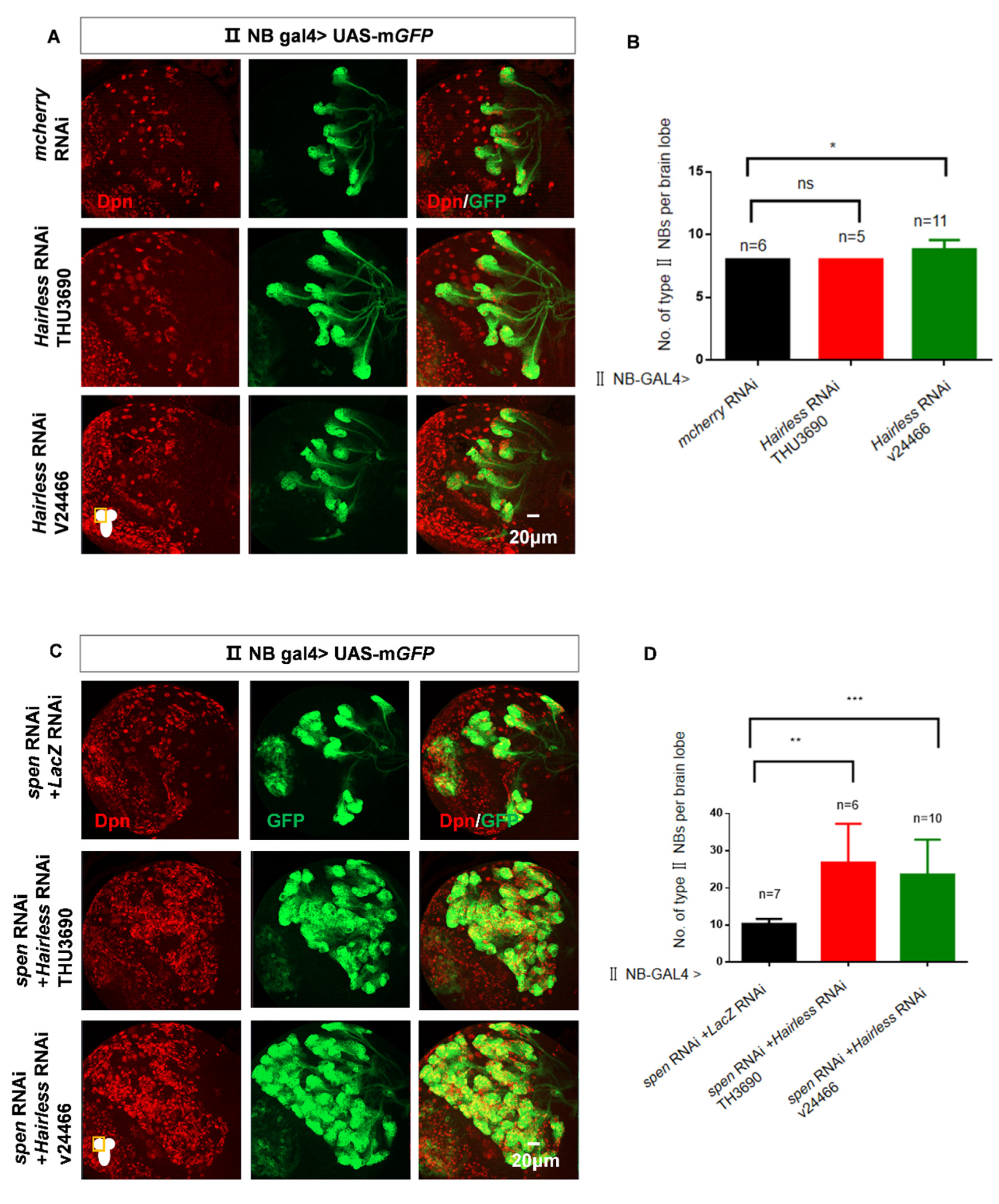

Figure 5.

The double knockdown of spen and Hairless leads to an excessive increase in the number of type II NBs. (A-B) The number of type II NBs had a modest effect in Hairless knockdown brains. (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (A) Mean ± SEM , *P<0.05, ns, non-significant. (C-D) Knocking spen and Hairless down led to more ectopic type II NBs compared to knockdown spen alone. (D) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (C).**,*** P<0.01. (E-F) Hairless knockdown in imINPs remained normal type II NBs number. (F) Quantification of type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (E), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. (G) Spen-GAL4 derived mcherry-NLS expression. (H) Hairless-GAL4 derived mGFP expression. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A and C. LacZ marked imINPs and their lineages in E.

Figure 5.

The double knockdown of spen and Hairless leads to an excessive increase in the number of type II NBs. (A-B) The number of type II NBs had a modest effect in Hairless knockdown brains. (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (A) Mean ± SEM , *P<0.05, ns, non-significant. (C-D) Knocking spen and Hairless down led to more ectopic type II NBs compared to knockdown spen alone. (D) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe about (C).**,*** P<0.01. (E-F) Hairless knockdown in imINPs remained normal type II NBs number. (F) Quantification of type II NBs in per brain lobe from genotypes in (E), Mean ± SEM, ns, non-significant. (G) Spen-GAL4 derived mcherry-NLS expression. (H) Hairless-GAL4 derived mGFP expression. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages in A and C. LacZ marked imINPs and their lineages in E.

Figure 6.

The EGFR signaling pathway is involved in spen-mediated maintenance of type II NBs. (A) Double knockdown of spen and Egfr could partially rescue the increasing type II NBs number compared to knock spen and lacZ down. (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, *** P<0.01,, ****P<0.0001 . (C-D) Overexpression of a constitutively active form of Egfr or knockdown of Egfr does not affect the number of type II NBs. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages.

Figure 6.

The EGFR signaling pathway is involved in spen-mediated maintenance of type II NBs. (A) Double knockdown of spen and Egfr could partially rescue the increasing type II NBs number compared to knock spen and lacZ down. (B) Quantification of type II NBs number in per brain lobe from genotypes in (A). Mean ± SEM, *** P<0.01,, ****P<0.0001 . (C-D) Overexpression of a constitutively active form of Egfr or knockdown of Egfr does not affect the number of type II NBs. GFP marked type II NBs and their lineages.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. Pattern diagram of the role of spen in type II NBs. (A) In wildtype, spen may act as a co-repressor to regulate nuclear NICD levels, thereby repressing the expression of genes downstream of the Notch signaling pathway. So that the number of type II NBs can be maintained at normal levels. (B) In the absence of spen, the level of nuclear NICD are elevated, resulting in increased expression of Notch signaling pathway genes. Then imINPs dedifferentiate into type II NBs to increase the number of type II NBs. Brat can inhibit this dedifferentiation.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. Pattern diagram of the role of spen in type II NBs. (A) In wildtype, spen may act as a co-repressor to regulate nuclear NICD levels, thereby repressing the expression of genes downstream of the Notch signaling pathway. So that the number of type II NBs can be maintained at normal levels. (B) In the absence of spen, the level of nuclear NICD are elevated, resulting in increased expression of Notch signaling pathway genes. Then imINPs dedifferentiate into type II NBs to increase the number of type II NBs. Brat can inhibit this dedifferentiation.