1. Introduction

Food and nutrition insecurity (FNI) has been documented as a significant issue affecting students in higher education, with estimates suggesting that 33-50% of college students experience some level of food insecurity [

1]. Studies have demonstrated that food insecurity negatively impacts academic performance, concentration, and overall student well-being[

2]. While FNI research has largely focused on undergraduate and graduate student populations, fewer studies have examined its prevalence among medical students, who face unique financial constraints due to intensive training requirements and limited employment opportunities during their education.

A 2021 study conducted at Yale School of Medicine found that 26.6% of surveyed medical students experienced food insecurity, a prevalence rate more than double the national average [

3]. However, the majority of existing research has been conducted at predominantly white institutions [

3,

4,

5], leaving a gap in understanding how FNI impacts students underrepresented in medicine. Native American, Latino, and Black medical students, in particular, face higher levels of educational debt, which may compound challenges related to food security and overall well-being [

6].

This study aims to address this gap by assessing the prevalence and impact of FNI among medical students at Howard University College of Medicine (HUCM), a historically Black medical institution. The findings will contribute to the growing body of research on financial hardship in medical education and provide a basis for institutional and policy-level interventions to support student well-being and prevent attrition.

2. Materials and Methods

In the Spring of 2025, a cross-sectional survey was administered to medical students in all classes at HUCM, following IRB approval. The survey incorporated the USDA Six-Item Short Form Food Security Scale[

7] to measure food insecurity in students. Criteria for food insecurity are a score of low to very low food security or >2 positive responses in the survey. No other standardized questions were used in the survey. We did collect demographics such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and the source of their financing while in school. We also asked students about their financial concerns, dietary habits, food access, and the subjective impact of food insecurity on their health and academic performance. Though we considered also asking about their expected amount of debt and income after graduation, as well as other aspects of well-being such as mental health, we chose to focus on FNI and keep the survey as brief as possible to maximize responses and reduce fatigue.

A link to the survey was sent to all students through bulk email and a QR code was posted at several points of contact throughout the school. Surveys were completed through Microsoft Forms to link responses to specific individuals in our institution. Data was analyzed through Microsoft Excel and R to generate descriptive statistics and figures.

3. Results

120 students responded to the survey out of the approximately 400 students (~100 students per class) who received it (~1/3 in total) and 100% of respondents filled out the survey in its’ entirety. Race and ethnicity of respondents are in

Table 1. The mean age was 26 years with a range of 20 to 40 years.

Based on the USDA short form, 49% of students reported food insecurity which is defined as having low or very low food security. 23% met criteria for very low food security while 27% had low food security.

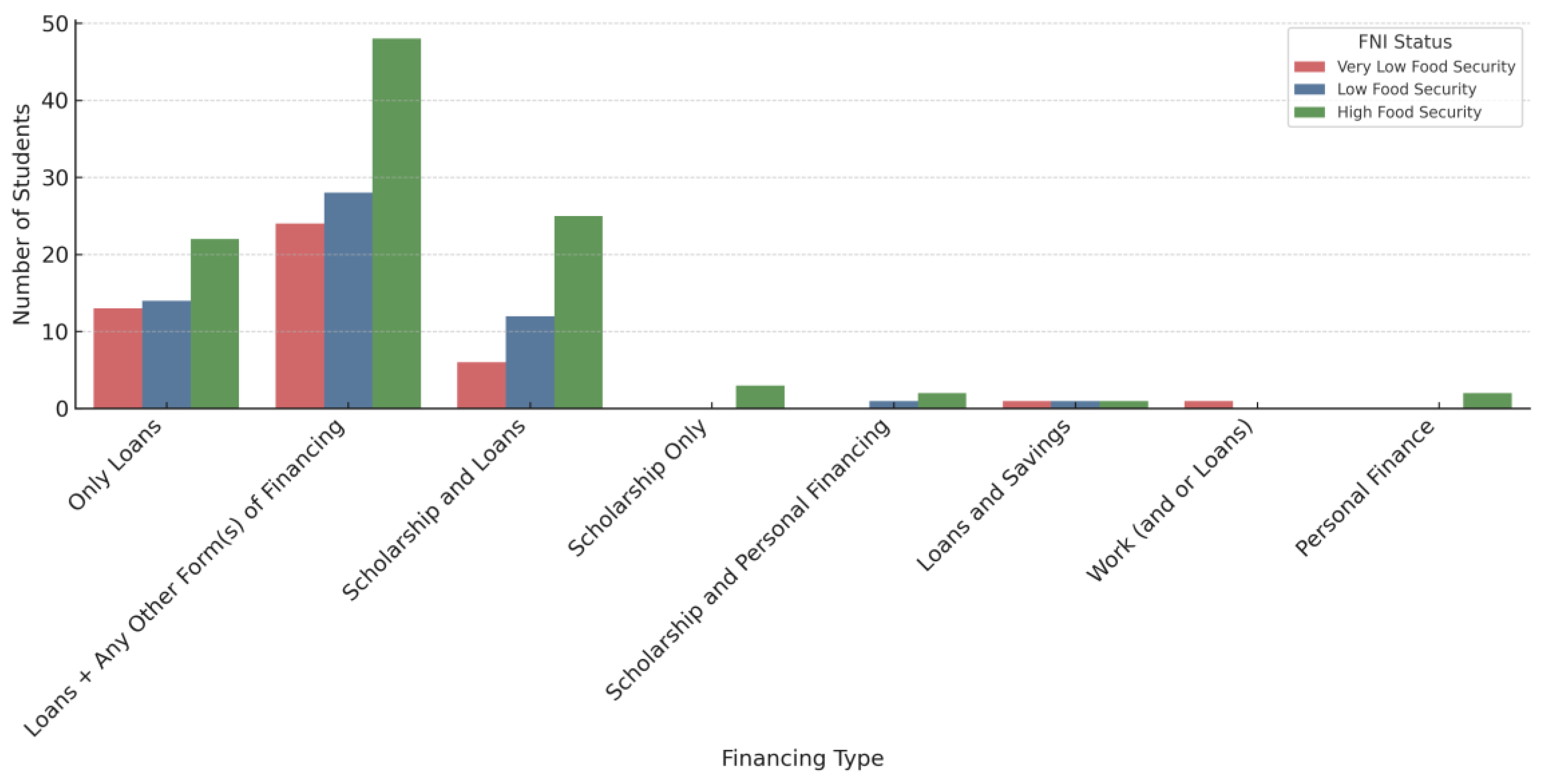

Next, we explored students’ financing and concerns about cost of living. 85% of students took out loans to finance their education, 42% were completely dependent on loans, 36% had a mix of loans and scholarships, 2% had full scholarships, and 1% had personal financing (

Figure 1). 82% reported concerns about meeting basic living expenses as well as the timing and amount of money provided through loans.

The most common financial concerns were debt after graduation (83%), the cost of housing (60%), food (59%), healthcare expenses (40%), and transportation (24%), these categories were not exclusive. 31% of students did not have reliable access to healthy foods. 70% reported skipping meals or replacing meals with less nutritious options due to financial and/or time constraints at least once a week. 77% identified food and nutrition security as impactful to their academic performance while 35% reported that FNI directly impacted their performance within the last month. 92% want additional food resources on campus and 83% are willing to volunteer to help maintain a garden on campus.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first documentation of food and nutrition insecurity (FNI) among students at a historically Black medical school. Nearly half of HUCM students surveyed met USDA criteria for food insecurity—a rate significantly higher than national and local estimates of 12.2% and 8.8%, respectively [

8]. More than 80% expressed concern about meeting basic living expenses, and 70% reported routinely skipping or downgrading meals due to financial or time constraints. The proximity of fast-food restaurants compared to grocery stores highlights how environmental factors intersect with financial limitations, favoring convenience over health for students with limited time.

A key contribution of this work is its focus on a majority Black student body—an underrepresented population in FNI research. While limited racial diversity in the sample constrained subgroup comparisons, it enabled an in-depth examination of structural barriers in a high-debt, high-stakes training environment. Survey results show that 84% of respondents rely on loans, with only 2% reporting full scholarships. Loan-dependent financial aid models appear inadequate to cover basic living expenses and likely contribute to unhealthy eating behaviors. Students reported sacrificing healthier food options to save money or reduce debt burden, underscoring systemic gaps in medical education financing.

Another structural issue raised by respondents is the delay in loan disbursements, particularly during summer months or academic progression delays, which compounds financial strain. This echoes broader inequities in financial aid structures, where students are assumed to have safety nets that may not exist. Similar concerns have been documented in other higher education settings, linking delayed or insufficient aid to academic stress and food insecurity [

1,

2,

3].

Strengths of this study include the use of validated USDA measures alongside context-specific questions and broad participation across class years, enhancing representativeness. Limitations include reliance on self-reported data, the brief survey format, and the single-institution scope, which may restrict generalizability. Future studies should incorporate additional measures such as projected debt, specialty choice, mental health, weight change, and major financial transitions during training. Longitudinal designs will be critical to understanding how FNI evolves over time and whether interventions succeed in mitigating its effects.

5. Conclusions

Half of HUCM medical students surveyed met criteria for food insecurity, revealing that FNI is not an isolated issue but a systemic challenge in medical education. Reliance on loans, delays in disbursement, and limited institutional support appear to drive students toward unhealthy coping behaviors that may undermine academic performance and wellness. Reforms in financial aid policy—including larger cost-of-living allowances, emergency support, and alignment of disbursements with academic schedules—are urgently needed. Local initiatives such as The FARM at HUCM demonstrate the potential of student-driven solutions, but structural reforms remain essential. Addressing FNI in medical education is critical not only for student well-being but also for sustaining a diverse and resilient physician workforce.

Author Contributions

D.H. was involved in concept development, data collection, analysis, drafting and editing of the manuscript. A.C. was involved in data collection and editing of the manuscript. Y.F. provided faculty mentorship and was involved in the concept development, data analysis, and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Howard University IRB in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under IRB# 2024-1575 and all participants consented to the use of their data for publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Howard University, College of Medicine, Medical Doctor Program, Classes of 2025, 2026, 2027, and 2028.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FNI |

Food and Nutrition Insecurity |

| HUCM |

Howard University College of Medicine |

| USDA |

United States Department of Agriculture |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| USMLE |

United States Medical Licensing Examination |

References

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M. The struggle is real: A systematic review of food insecurity among U.S. college students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne-Sturges, D.C.; Tjaden, A.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M. Student hunger on campus: Food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. Am J Health Promot. 2018, 32, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.G.; Mercier, M.R.; Chan, C.; Criscione, J.; Angoff, N.; Ment, L.R. Food insecurity in medical students: Preliminary data from Yale School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2021, 96, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, M.M.; Monteiro, K.; George, P.; Tunkel, A.R. Assessing food insecurity in medical students. Fam Med. 2020, 52, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholeye, O.O.; Taiwo, O.E.; Animasahun, V.J. Too little for comfort: Food insecurity among medical students in Sagamu, Southwest Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2021, 38, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMichael, B.; Lee, A.; Fallon, B.; Matusko, N.; Sandhu, G. Racial and socioeconomic inequity in the financial stress of medical school. MedEdPublish 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Rabbitt, M.P.; Reed-Jones, M.; Hales, L.J.; Burke, M.P. Household food security in the United States in 2023; ERR-337; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).