1.0. Introduction

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that plays crucial functions in load bearing of the knee joints, shock absorption and distribution, and further, it supplies nutrients, lubrication, and proprioception to the knees[

1]. The meniscus injury is often challenging to treat and affects the entire knee functions and the progression of the conditions leads to cartilage disruption, osteoarthritis, and loss of functions[

2]. In other words, meniscus injury is considered to have poor self-healing potential. The current clinical practice for meniscus injury is to trim the tear region known as a meniscectomy, surgically removed or meniscus transplantation is performed[

2,

3]. The post-operative surgery shows that the degeneration of left-over meniscus occurs directly proportional to the amount of meniscus removed. In addition, during the process of meniscus transplantation, the size, and shape of the meniscus vary within the same age group and this reflects on the load distribution of the meniscus while designing the implants[

4,

5]. To counteract the problems associated with meniscus treatment, there is a need for effective and persistent approaches. Thus, a patient-specific design helps to match the exact dimension and shape of the individual meniscus and avoids patent mismatch[

6]. In the past decade, 3D Bioprinting technology has gained a lot of attention due to its versatile nature. 3D bioprinting is an addictive manufacturing technique that enables the creation of intricate 3D live tissue constructs with precise shapes and architectures, mimicking the complexity of human tissues using bioinks[

7,

8]. The decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) is considered a potential bio-ink that provides microarchitecture, tissue-specific environment, and biochemical properties essential for cellular behavior like cell adhesion, infiltration, migration proliferation, and differentiation of cells[

9]. The dECM can form a hydrogel at physiological temperature and pH which makes it a suitable bio-ink for 3D printing. This bio-ink is desired to have biocompatibility, bioactivity, shape retention, and durability[

10]. In recent years, there have been significant improvements in developing the various dECM based biomaterials for meniscus tissue-engineering applications, especially with different cross-linking strategies to achieve variation in mechanical properties and stability[

7,

8,

11]. The most crucial aspect in 3D decellularized matrix constructs is that the desired shapes are expected to maintain structural strength, integrity, and architecture within the in situ environment. Thus the key successful meniscus 3D printing relies on the ability to mirror the anatomy, and framework of the meniscus’s macroscopic and microscopic organization[

2].

In this review, we focused on the anatomy, microarchitecture, and biomechanical properties of the meniscus, as well as current approaches and advancements available for addressing meniscus injuries. Additionally, the paper specifically explored the use of decellularized matrix as a source material for bio-ink in 3D printing. A thorough analysis was done on the essential criteria for dECM bio-inks, including immunogenicity, ECM protein composition, printability, biocompatibility, biomechanical properties, and types of cross-linkers. In conclusion, we discuss the potential applications of dECM bio-inks in meniscus tissue engineering and highlight the most promising approaches for meniscus 3D printing.

2.1. Meniscus Anatomy

The lateral and medial meniscus is a crescent-shaped structure made up of fibrocartilage tissue located in the knee and acts as a cushion between the femur and tibia bone during leg motion[

3,

4,

12]. The lateral and medial meniscus lengths are approximately 35mm and 45mm. The lateral meniscus is circular and dominantly covers the tibia bone more than the medial meniscus. The anterior, mid, and posterior horn regions are present in both lateral and medial meniscus. The anterior horn of the medial meniscus is attached to the tibia and the anterior cruciate ligament surface and the mid horn is linked to the medial collateral ligament[

13]. The posterior horn of the medial meniscus is connected to the intercondylar fossa, meniscocapsular, and meniscotibial ligaments. The width of the human medial meniscus in the anterior, mid, and posterior horns is 7.6mm, 9.3mm, and 12.6mm[

14] as shown in

Figure 1. The width of the lateral meniscus anterior horn is 7.5mm and the posterior and mid-horn width is 10.4mm. The lateral meniscus posterior horn is joint to the popliteomeniscal, posterolateral capsule, and meniscotibal ligament, and the anterior is connected to meniscofemoral ligaments in the tibia region.

2.2. Meniscus Microarchitecture

The meniscus is made up of three regions outer red-red region; red-white region; and white-white region as shown in

Figure 2(a). The human meniscus is composed of 20-30% organic materials like collagen, proteoglycan, and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) and the remaining 70-80% is water[

3,

13]. Predominantly, 90% of collagen is type I which is distributed whole meniscus in the form of circumferential fibers. Whereas, type II collagen is located in the inner avascular region in the form of circumferential and radial fibers and it is responsible for the tensile strength of the meniscus. However, type III, IV, V, and VI collagen proteins are also present in the meniscus in negligible forms. The orientation of the collagen fibers is not fixed in one direction; fibers are arranged in circumferential, radial, or irregular directions[

13]. GAG is organized in the inner zone of the meniscus consists of 60% chondroitin sulfate, 20-30% dermatan sulfate, 15% keratan sulfate, and hyaluronic acid proteins[

5]. The total dry weight percentage of GAG present in the inner meniscus is 0.8% which is responsible for load bearing. Aggrecan, decorin, biglycan, and fibromodulin are the common types of proteoglycan present in the meniscus, and aggrecan proteins are responsible for viscoelastic compression strain and prevent meniscus injury. One or more proteoglycan proteins are attached to form the GAG. Distinct cell morphologies have been observed across meniscus region[

2]. Such as fibroblast-like cells appear in elongated form in the outer red-red region[

12]. Whereas, chondrocyte-like cells appear oval or round in the red-white region, and fusiform cells are arranged in elongated form in the white-white region[

15]. The cell-specific marker for meniscal cells is CD34/alpha-smooth muscle actin which is responsible for the repair and regenerative processes during the pathological injury of the meniscus[

2,

5].

2.3. Biomechanical Properties of Meniscus

The meniscus covers about 60% of the contact area between the femoral condyles and the tibial plateau, over 50% of the axial load is transmitted directly[

16]. It exhibits an aggregate modulus of 100-150kPa under axial compression and a circumferential tensile modulus ranging from 100-300 MPa, with a shear modulus of approximately 120kPa[

17]. It also exhibits complex, time-dependent mechanical behavior that is strongly influenced by its structural and compositional heterogeneity. Kim et al. investigated the bovine meniscus and concluded that it shows higher ultimate tensile stress (18.9 MPa) and toughness (4.7 MPa) than cartilage, due to its higher collagen content[

18]. Also, Young’s modulus of 49.9 MPa and strain-dependent tensile modulus defines a material’s high tensile stiffness with a corresponding applied strain that enables it to withstand higher loads. This significantly exceeds those of cartilage, highlighting its superior mechanical strength. Li et al. found that the mechanical properties of the meniscus are highly anisotropic, particularly in the circumferential fibers, which show higher stiffness in the vertical section compared to the horizontal section[

19]. This anisotropy is most pronounced in the outer zone of the meniscus, where the circumferential fibers have significantly higher moduli compared to the inner zone[

20]. Furthermore, theoretical and experimental models at the microscale level indicate that the cells in the meniscus are exposed to a complex, time-varying environment of stress, strain, fluid pressure, fluid flow, and physicochemical factors[

21]. When normalized to ultimate tensile strength (UTS), the tensile fatigue strength of the human medial meniscus is not significantly affected by age, showing that both young and older menisci show similar fatigue resistance at lowstress levels. Such findings provide valuable insights into the mechanical behavior and resilience of the meniscus under repetitive loading. Therefore, it is important to consider the tissue’s structural and compositional heterogeneity in understanding its function and pathophysiology. This will enable to gain a deeper understanding of structure-function relationships, which is essential for advancing the fields of meniscal repair, replacement, and overall knee joint health. Rosa et al. introduced the Maxwell model for the characterization of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the meniscus, which captures the viscoelastic nature of the tissue[

22]. This model accurately describes the shear behavior of the meniscus, with the shear modulus increasing and the phase angle decreasing with shear frequency. The Maxwell model is a common way to explain how materials that are both stretchy and flowy behave[

16]. It uses a spring (for stretching) and a damper (for resisting flow) connected one after the other. This plays a crucial role in determining meniscus, the tissue in the knee and how it responds to stress over time. Also, the model captures the way materials change over time when stress is applied, which is a key characteristic of viscoelastic materials. In the case of human meniscus, the ECM’s mechanical response to shear stress was found to be well-described by a Maxwell model with three relaxation times which represent different characteristic time scales over which the tissue undergoes viscoelastic deformation, allowing the model to account for both the elastic and viscous components of the tissue’s response. The generalized Maxwell model’s ability to match experimental data from frequency sweep tests on meniscus samples shows its effectiveness in characterizing the meniscus’ viscoelastic behavior, especially under dynamic loading, which is key to understanding its response in the body.

2.4. Existing Treatment for a Meniscus Tear

The meniscus tear is usually caused by three major events such as sports-related activities, non-sports-related activities, and no injury[

23]. During sports-related activities like soccer, rugby football, hockey, and gymnastics people encounter sudden twists of the knee due to motion, and bearing heavyweight[

24]. As a result, the impact force or rotational forces and shear forces between the femoral condyles and the tibial plateau cause meniscus tear. In non-sports related activities, a person who suddenly falls from a motorcycle, or bicycle can twist the knee on landing on a surface leading to a minor meniscus tear[

12]. In no injury cases, meniscus tear occurs due to age-related degeneration, and osteoarthritis on the knee joints[

3]. The current challenge associated with meniscus tears is that tissue recovery occurs in the red-red region. In the case of the red-white region and white-white region, lack of vascularization of blood vessels results in low repair tendency[

25]. The current treatment for a meniscus tear is meniscectomy in which the torn region is surgically removed or a meniscus suture or meniscus transplantation is performed[

26]. The meniscus implant is preferred over meniscectomy and meniscus transplantation due to less invasive surgery, faster recovery time and reduces the risk of osteoarthritis[

2].

Figure 2(c) shows the commercially available meniscus implants like CMI

®, FibroFix

®, and Nusurface

®, are made up of synthetic or natural polymers

(Table: 1.1). Whereas, the problems associated with meniscus transplantation are finding a donor, prone to contamination, size mismatching, and graft rejection[

27]. Further, the post-operative complications include irreparable lesions of the avascular zone, cartilage re-injury, knee pain, joint stiffness, infection, mechanical block, and arthritis as shown in

Figure 2(b) shows [

28]. The choice and type of graft significantly contribute to the charges associated with meniscus surgery.

Table 1.1. Commercial available biomaterial-based scaffold for meniscus replacements

.

3.1. 3D Bioprinting Meniscus Implant/Scaffold Using dECM

3D bioprinting is an additive manufacturing technology that utilizes the bio-ink to print the layer-by-layer structure of the 3D object. Initially, the 3D design of the meniscus is obtained from 3D reconstruction of patient knee MRI data and later converted to 3D model for printing. The flow chart for the preparation of a 3D-printed meniscus construct made from a dECM bioink as shown in

Figure 3.

3.1.1. Source Material

The animal organ from which the material is obtained plays a major role in getting the maximum yield of dECM powder to construct the 3D structure[

29]. The dECM powder can be generated by decellularizing any source like skin, liver, heart tissue, intestinal, tendon, meniscus, and urinary bladder[

5,

8]. Initially, the source material is incubated with the various decellularizing solutions and exposed at different time intervals until the decellularization is achieved. However, the duration of the process varies from hour to day depending on the size, and thickness of the source material[

11]. During the decellularization process, the ECM is washed with PBS several times to prevent the chemical residues deposit.

3.1.2. Decellularization

Decellularization is a process of removing the cells from the ECM and the biochemical composition of the ECM is maintained to promote cell adhesion and differentiation without any immunogenic or allergic reaction in the host system[

29]. The decellularization process can be achieved by physical, chemical, enzymatic, or a combination of methods. Physical decellularization is performed by using agitation of the tissue with a magnetic stirrer, heat treatment, or sonication of the tissue to create a cell-free matrix[

29,

30]. The chemical approaches utilize ionic and non-ionic detergent, and hypotonic-hypertonic solution to solubilize the cytoplasmic membrane and cellular component in the ECM. The enzymatic approach uses nuclease, and other proteolytic enzymes to digest the DNA, RNA, and cellular protein of the ECM. At the end of decellularization, the ECM can be sterilized by gamma radiation, ethylene oxide, antibiotic/antimycotic, and peracetic acid.

3.1.3. Preparation of Bio-Ink from dECM

The dECM can be solubilized by using a combination of enzymatic, and acidic solutions[

31]. Briefly, the lyophilized form of dECM powder is digested by using pepsin in combination with acetic acid or hydrochloric acid, incubated at different time intervals with stirring conditions, to achieve a gel-like substance[

32]. After achieving a gel-like substance the pH of the samples is neutralized using NaOH to regain the intramolecular bonds of dECM. Wang et al. studied the effect of pH on dECM ink’s rheological and mechanical properties[

33]. At pH 11, the viscosity of dECM ink is higher resulting in a denser network of collagen fibers, and promotes higher compression strength compared to the native porcine meniscus. Additionally, the dECM ink inconsistent, rough, and non-uniformly during extrusion at pH 7. Concentration and type of acids play an important role in the preparation of bioink. For example, acetic acid and hydrochloric acid are used for solubilization of dECM at various concentrations (0.5M, 0.1M, 0.01M, 0.02M) [

14,

32,

33,

34]. Zhao et al. specifically, compared the three different acidic solutions to solubilize the decellularized porcine tendons using the pepsin enzyme[

32]. The 0.1M hydrochloric acid rapidly digests the dECM powder then 0.5M acetic acid and 0.01M hydrochloric acid. Additionally, the observation suggests that rapid digestion occurs due to the pH of the HCL being 1.6 at the end of the digestion and the activity of pepsin is higher when the pH is less than 2.2. Thus, the choice of acid concentration and lower pH promotes the proper digestion of dECM in the preparation of bioink.

3.2. Criteria Required for dECM Bio-Ink for Meniscus 3D Printing

3.2.1. Immunogenicity

The decellularized matrix obtained from xenogeneic sources like skin, liver, heart tissue, intestinal, tendon, meniscus, and urinary bladder contains allorecognition material[

35]. The allorecognition such as IgG/IgM/IgE proteins and alpha-gal carbohydrate causes hyperacute graft rejection in the human body[

36,

37]. The techniques for identifying immunogenic material in the dECM are DNA quantification, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and DAPI histology and comparing them with native tissue. Choudhury et al. state that in the post-decellularization process, the DNA content in the dECM should be below 50 ng/mg to discourage any graft rejection[

38]. Another approach to detecting the cellular and nuclear remnants present inside the dECM is stained by haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) DAPI staining[

31]. These techniques are used together to identify the cells present in the top and bottom surfaces as well as the cross-section of the ECM. In the H&E stain, the ECM appears pink in colour, and cell nuclei appear blue. Whereas, DAPI-stained nuclear DNA appears to have a fluorescent blue color. Lim et al. compared the effect of α-gal protein by implanting the decellularized scaffold and glutaraldehyde fixed tissue in the in vivo rabbit model for 60 days[

39]. The ELISA assay result shows the production of anti-α-gal in the decellularized tissue is significantly lower than in glutaraldehyde-fixed tissue. By minimizing the xenogeneic material, dECM can be safely used for biomedical applications.

3.2.2. ECM Proteins

Collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycan are the proteins present in ECM which are mainly responsible for cell adhesion, growth factor signaling, migration, and wound healing process[

40,

41]. During the decellularization process, the ECM is exposed to various chemicals and enzymatic agents for a longer duration of time, and as a result loss of ECM proteins occurs[

31]. Optimizing the decellularization process like the concentration of the chemical, and duration of exposures, helps to control the loss of proteins in the dECM[

42,

43]. Often, the biochemical assay is performed on the dECM and native tissue to determine the amount of collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycan loss in the post-decellularization process[

44]. In recent years, proteomic analysis has been performed on dECM using mass spectrometry. This experimental approach quantifies a group of proteins specifically present in each zone of dECM, and the gene responsible for production can be identified. Yun et al. reported totally 146 proteins were identified in the outer layer, mid-layer, and inner layer of decellularized porcine meniscus through proteomic analysis[

45].

3.2.3. Printability

The dECM bio-ink should extrude out precisely from the 3D printer and this is highly dependent upon the rheological properties and fabrication method. The rheological properties include viscosity, shear stress, and elasticity.

3.2.3. Rheological Properties

The rheological properties of the bioink are characterized by measuring the viscosity (η), storage modulus (

), and loss modulus

before and after incubation with cross-linker. Ideally, the bioink should gel rapidly, either following extrusion or crosslinking, to ensure the preservation of its shape and stability[

46]. The shear-thinning behaviour is an important rheological property that influences the printability[

47]. During printing, the hydrogel is subjected to high shear forces, which can break non-covalent bonds and reduce viscosity. However, when the shear force is removed, the bonds can reform, increasing the viscosity and helping the hydrogel retain its desired shape[

47]. The following sections provide a detailed discussion of each rheological parameter.

3.2.3.1. Viscosity

Viscosity refers to the material resistance to the flow of fluid in between the nozzles[

47]. The dECM bio-ink viscosity depends upon the molecular weight, ECM components, temperature, fabrication method, and the ratio of the components used in the study[

48]. For the inkjet fabrication method, the bio-ink required a low viscosity of 3.5-12 mPa.s to achieve a precise 3D shape[

49]. Whereas, the stereolithography requires bio-ink viscosity ranging from 1-300 mPa.s. Moon et al. reported that the optimal viscosity for extrusion bioprinting ranges from 30-60 × 10

7 mPa.s for bio-ink[

50]. Usually, the bioink’s higher viscosity provides excellent mechanical strength and prevents structure deformation. However, the higher viscosity encapsulates the cell and restricts the cell survival, and proliferation, controlling the cell’s bioactivity. In contrast, the bio-ink with lower viscosity supports cell viability and bioactivity but often faces the issue of poor printing resolution and fidelity. Hence, optimizing the viscosity of bio-ink can provide desired mechanical strength, cell survival, cell bioactivity, and high printing resolution. The viscosity of bio-ink changes when the force is applied and it is calculated by the power law equation[

47].

where, η represents the viscosity,

is the shear rate, and K and n are the shearing thinning coefficients

3.2.3.3. Extrusion Pressure and Shear Stress

The cross-section of the nozzle tip is divided into the inner region, middle region, and outer region[

46,

51]. In cell-laden 3D bioprinting, the cells get entrapped and extruded with the bioink, and will experience shear stress in different regions. The average shear stress (τ) experienced by the bio-ink can be calculated by force applied (F) divided by the cross-section of the area (A)

3.2.3.4. Elasticity

The elasticity of bio-ink can be determined by storage modulus (

) and loss modulus (

)[

52]. The storage modulus (

) represents the ability of the materials to store energy which is also known as elastic behavior and the material’s ability to dissipate energy is represented by loss modulus (

)[

53]. If the storage modulus higher than the loss modulus, it results in increased mechanical stiffness and provides efficient printing fidelity. The bioprinting fidelity (loss tangent δ) refers to the accuracy of the final 3D printed product in comparison with 3D model and it is based on the ratio between storage modulus (

) and loss modulus (

). A loss tangent δ value greater than 1 signifies liquid-like behaviour of the bioink. Conversely, a solid-state material exhibits a tangent δ value less than 1. Therefore, a higher loss modulus than the storage modulus can impart more fluid-like flow characteristics to the bioinks, potentially compromising shape fidelity.

In general, the human meniscus loss modulus is between 0.1-0.5 MPa and the storage modulus is 0.5-2.0 MPa. There are various studies that reported the use of dECM bioink to achieve loss and storage modulus values matching human meniscus. Ronca et al. reported that the storage and loss modulus of 12% of collagen hydrogel were: 5.1 ± 1.4 kPa and 0.65 ± 0.16 kPa[

54]. The time taken by the hydrogel to break the non-covalent bond and recovery time from liquid to gelatinous takes 4.1 ± 0.3 s. This shows good layer by layer stacking construct can be achieved. Similarly, Chae et al. reported dECM meniscus bio-ink

is similar to the pure collagen bioink at a temperature below 15°C and the modulus increased rapidly as the temperature reached 37°C, which is an indication of bioink gelation [

55]. The time taken for gelation was found to be 30 minutes. In another study, the storage modulus of bovine collagen type-I with methacrylate was found to be 3kPa, and exposure to UV light enhanced the modulus to 9.68kPa and recovery time from liquid to pasty took 4 minutes[

14]. Overall, the gelation time of dECM is influenced by concentration, crosslinking agent, pH, and ionic strength[

56].

3.2.4. Fabrication Method for dECM Scaffold

3D bioprinting is used to print cell-free natural polymers, cells encapsulated in hydrogels, cell aggregates, and cell-seeded microcarriers formulated as “bioinks”[

57]. It is based on the principle of layer-by-layer deposition of the bioink. Various bioprinting techniques are used in decellularized extracellular matrices[

58].

3.2.4.1. Extrusion Bioprinting

Extrusion bioprinting is the most versatile and commonly used method among 3D bioprinting techniques. Extrusion-based printing works on the principle of dispensing the bio-ink as a continuous filament in a layer-by-layer manner to produce a 3D structure. The dispensing technique can be pneumatic or mechanical extrusion, where the mechanical extrusion is further divided into piston-based or screw-driven systems[

2]. With the help of extrusion bioprinting, materials with a viscosity of (25 – 30) × 10

3 MPa can be printed. It works by reduction in viscosity due to an applied pressure leading to the deposition of material, followed by gelation as soon as the shear force is removed[

2]. Zhang et al. have printed dECM hydrogel in a three-dimensional grid structure with a printing pressure of 40kPa and a printing speed of 15 mm/s [

32]. The advantages of this technique include the ability to print a wide range of viscous biomaterials, and it offers high cellular density. It also has the advantage of printing tissues with high throughput and ease and processing capacity of several types of bio-inks[

57]. However, the speed and resolution of the printing process are relatively low[

58].

3.2.4.2. Inkjet Printing

Inkjet-based printers allow the release of controlled volumes of cells or biomaterials at predefined locations on a moving stage[

59]. The droplets of 10 µm are deposited in a bottom-up strategy where an actuator generates pressure at the nozzle opening, thereby ejecting the bio-ink droplets on the surface plate of the printer. Low-viscosity bio-inks (shear viscosity less than 30 MPa) are used in this technique to avoid nozzle clogging. Inkjet printing is a low cost and time-efficient process [

2]. This method is mainly used for printing structures with non-continuous flow of biomaterials[

58]. Cavallo et al. used micro-valve based inkjet printing with multiple printheads to print a custom-made human meniscus, with cell-laden high-density collagen type I using a printing speed of 12 mm/s at a pressure of 0.2 bar at 37ºC[

60]. Inkjet printing can be distinguished into thermal and piezoelectric jetting systems. The thermal jetting system or bubble jetting system uses heat and it is suitable for printing structures requiring high control over ultrastructure[

2]. The heat from the jetting system generates small air bubbles in the print head that collapse and eject the materials as bio-ink droplets. The droplet size and volume can be controlled by varying the heat and pressure of the system. In a piezoelectric jetting system, a voltage is generated due by the piezoelectric elements and it is used to actuate and form bioink droplets. In such systems, the cells might likely get affected by the voltage compromising cell membrane integrity. Therefore, thermal actuator systems are preferred[

2].

3.2.4. Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility in bio-ink refers to the non-cytotoxic materials, that support cell viability, adhesion, and proliferation and maintain phenotypic characteristics and should not elicit host inflammatory responses when implanted inside the human body[

57]. The numerous biocompatibility studies on the 3D printed meniscus have examined various cell types including meniscal fibro chondrocytes, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, synovial fluid[

5,

14,

61,

62,

63]. The MSCs have become popularly used and well-established sources due to easy sample collection, and reduced harm to donors[

64]. Chae et al. isolated the MSC from the bone marrow and culture for 14 days on the dECM bio-ink and compared it with pure collagen bio-ink[

55]. The cell proliferation analysis shows that 98% of MSC survived higher than commercially available bioink supports cell growth and differentiation of fibrochondrocytes. Lyons et al. determine the effect of various concentrations (8%, 12%, 16%) of genipin crosslinker on the biochemical response of the meniscus derived matrix [

65]. Genipin at a concentration of 16% significantly promoted the deposition of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and collagen within the meniscus derived matrix after 14 days of incubation. The aromatic compound with hydroxyl group presents the genipin covalent bond with ECM creating a suitable environment for cell growth. Similarly, Asgarpour et al. compared the various pore sizes (0.2 mm, 0.4 mm) of PCL, and biohybrid dECM_PCL to determine the effect of microarchitecture on hADSCs[

40]. The result showed that PCL-dECM with 0.2 mm porous space promotes higher metabolic activity than 0.4 porous space dECM. This is likely because biochemical cues for cell attachment, spreading, and proliferation are supported by the dECM with 0.2 mm PCL porous space. Various concentrations of decellularized collagen hydrogel (10, 12.5, 15%) were specifically designed to find the optimal concentration required for high printability[

54]. The meniscus cells obtained from avascular zone and vascular zone of human meniscus were seeded onto the decellularized collagen hydrogels. The gene expression analysis shows that the meniscus cells obtained from the both zones upregulated the matrix synthesis genes COL2A1 and COL1A1 in the 3D-printed 12% collagen scaffold after 28 days in the in vitro conditions. The biocompatibility of dECM bioink, as demonstrated by its ability to support cell viability, proliferation, and matrix synthesis, makes it a suitable material for meniscus tissue engineering applications.

3.2.4.1. Factors Affecting dECM Biocompatibility

The parameters that affect dECM biocompatibility include (i) shear force during extrusion of bio-ink and (ii) physical stress during homogenization of cells and bioink.

Shear force during extrusion of bio-ink

The shear force is usually generated in the bioink printed through an extrusion nozzle for 3D printing[

46]. The excessive shear force can damage the cell and bio-ink and reduce the cell viability in the 3D printed material. Habib et al. studied the effect of shear force on cell viability during the extrusion of bio-ink[

47]. Initially, sodium alginate hydrogel was extruded at 8 and 12 psi pressure through a 410 μm nozzle diameter. Overall, the cells could sustain up to 3.7kPa shear stress with 90% cell viability. In addition, the higher shear force was experienced by the cells at the nozzle wall, resulting in lower viability and preventing the consistent flow of the printed structure. The shear forces are usually affected by the nozzle diameter, nozzle type, and, extrusion speed. Pottathara et al. studied the effect of various nozzle diameters 500 µm, 250 µm, and 200µm on the 3D printed collagen-based hydrogel[

66]. After 14 days of incubation in Hanks’s blank salt solution, the wall diameter of the 3D-printed collagen increased with a decrease in the pore size of the nozzle. By optimizing factors such as nozzle diameter, and extrusion speed of the bio-ink, it is possible to minimize shear forces and improve the printability and biocompatibility of 3D-printed construct.

Physical stress during the homogenization of cells and bio-link

Traditional methods of mixing cells with bioink are performed by using the syringe coupler method or manual mixing using pipettes, which can lead to uneven distribution of cells within the bioink[

67,

68]. This variation in cell density and composition can affect the printed shape and its properties. Primary cells, in particular, are sensitive to the shear stress caused by aspiration and dispensing, which can result in cell damage or death[

69]. The physical stress during homogenization can be avoided by using alternate techniques like magnetic beads, cell encapsulation, and static mixing[

68]. These techniques help to protect the cells from damage by creating a semipermeable membrane around the cell, or by intense turbulence mixing. Thus, it is important to adopt alternative techniques to obtain uniform cell distribution and less cell damage during mixing with bio-ink.

3.2.5. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical strength is an essential criterion required for the dECM bioink for meniscus 3D bioprinting [

70]. The desired mechanical strength can be achieved by varying the concentration of dECM or using various types of crosslinkers[

71]. Usually, the mechanical properties of dECM hydrogel are studied by conducting compression testing, dynamic mechanical analysis, and ultimate tensile testing. Ronca et al. conducted dynamic mechanical analysis between 0.5-10 Hz, simulating normal physiological walking frequency, to investigate the mechanical behavior of decellularized collagen hydrogels with 40% and 70% infill[

54]. The storage modulus of the 70% infill hydrogel was found to be 73kPa, likely due to reduced porosity and increased scaffold stiffness. Notably, the storage modulus of native human menisci ranges from 0.5-2.0 MPa, suggesting that the 70% infill hydrogel may offer a suitable mechanical match for meniscus repair applications[

54]. In another study, tensile testing was performed on dECM bio-ink containing various concentrations of dECM (0%, 0.5%, 1%) in combination with gelation and methacrylate[

72]. The results demonstrated that the elastic modulus of dECM hydrogel was 33.24kPa, while it increased to 81.9kPa for the 1% dECM-gelation-methacrylate combination. However, it’s important to note that the elastic modulus of healthy human meniscus typically ranges from 105 to 189 MPa, indicating that further optimization may be necessary to achieve a more suitable mechanical match for meniscus tissue engineering applications[

73].

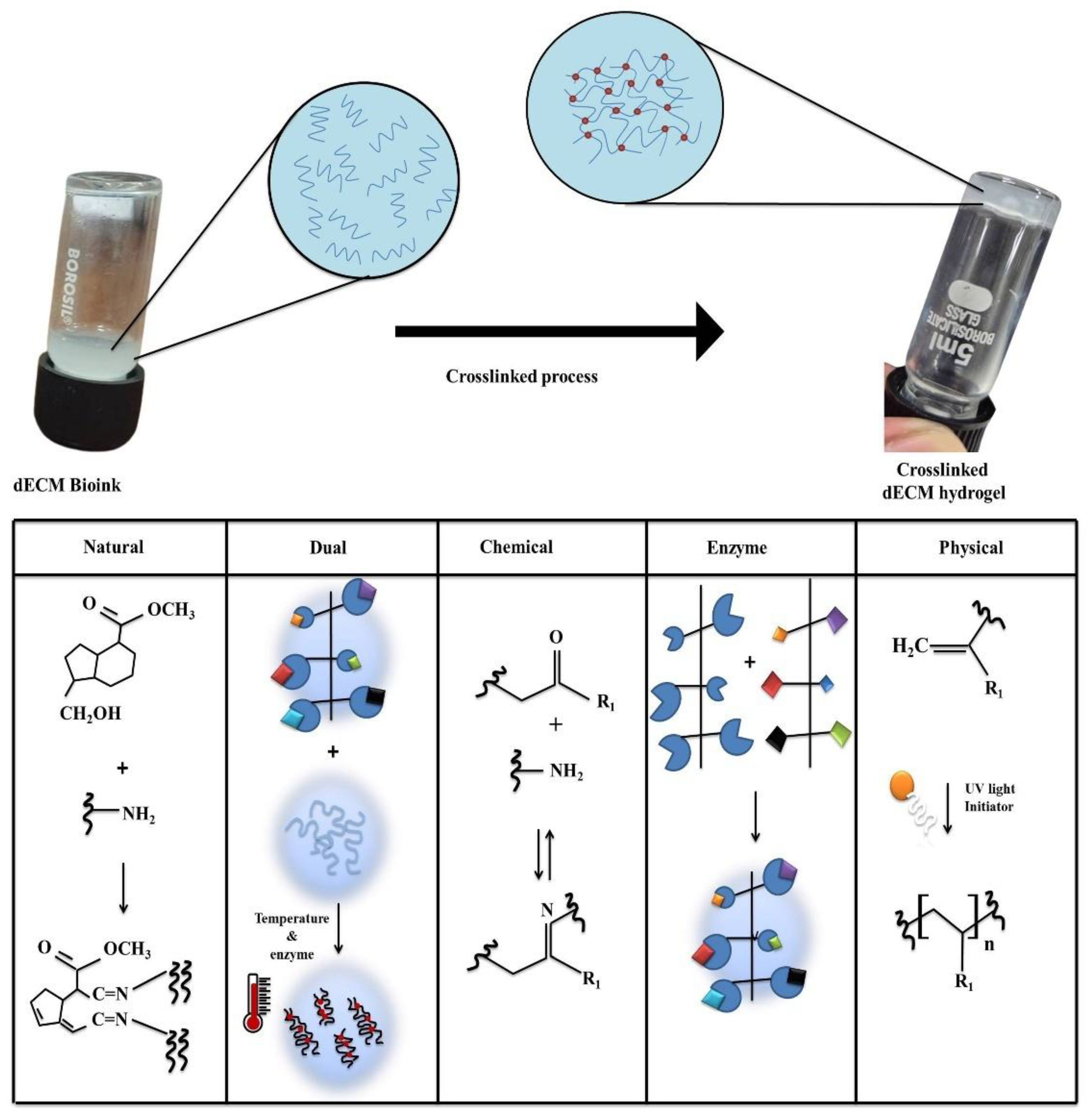

3.3. Crosslinkers for dECM Bio-Inks

In this section, we discuss natural, dual, chemical, physical, and enzymatic crosslinking performed on the dECM bioinks and schematic representation of the crosslinking mechanism are shown in

Figure 4. Then, the post-crosslinking results obtained from the various research groups obtained on the dECM bioinks are discussed.

Table 2, shows the recent studies on 3D printing meniscus tissue using dECM matrices and cross linker used.

Table 3, discusses the advantages and limitations of crosslinker used for dECM matrices.

Table 4.

Criteria required for dECM bio-ink for 3D printing meniscus.

Table 4.

Criteria required for dECM bio-ink for 3D printing meniscus.

| Parameters |

Essential meniscus characteristics required for dECM to 3D printing meniscus |

| Immunogenicity |

Cell-free extracellular matrix |

ECM proteins |

Collagen (60-70%), elastin (1-5%) and GAG (10-15%) |

Biomechanical properties |

Ultimate tensile strength |

Circumferential direction |

15-30MPa |

| Radial direction |

2-5MPa |

| Biocompatibility |

Supports the growth of meniscus cells |

Printability |

Viscosity |

Inkjet fabrication method: 3.5-12 mPa.s

Extrusion method: 30-60 × 107 mPa.s |

| n value between 0- 1 |

| Elasticity modulus |

Storage modulus (G‘) |

0.5-2.0MPa |

| Loss modulus(G‘‘) |

0.1-0.5MPa |

3.3.1. Natural

Hyaluronic acid

Xu et al. studied whether the decellularized crow scapular cartilage crosslinked with hyaluronic acid can be used as an injectable hydrogel for cartilage regeneration in the in vivo model[

51]. The crosslinked hydrogel was cultured with chondrocyte cells and subcutaneously implanted in the rabbit model. After 8 weeks of implantation, the quantitative analysis shows that the formation of collagen is 22mg/g of tissue which is like that of native tissue.

Genipin

Genipin is a derivative of the non-sugar component of glycosides present in the fruit of the gardenia jasminoides ellis plant and it is used as a traditional medicine for the treatment of headaches and inflammations[

11]. Genipin is composed of monosaccharides linked with glycosidic bonds that cross-link with proteins like collagen[

71]. The collagen cross-links with genipin through a nucleophilic attack on the C3 carbon atom of an amino group. As a result, dihydropyran open ring and unstable aldehyde group form. This open ring reacts with an amino group of collagen and forms a covalent bond. Further, the unstable aldehyde group attacks the other amino group to form another bond[

5]. Zhang et al. studied the effect of different concentrations of genipin on rat tail collagen to determine the optimal crosslinking conditions such as temperature and percentage of genipin. It was found that a 0.3% genipin concentration and a temperature of 37°C is optimal to achieve excellent crosslinking and good biocompatibility and non-cytotoxicity to rat chondrocytes[

74]. Adamiak et al. reported that genipin induces a change in the collagen-based hydrogel and incubation time increases the storage modulus of the collagen after being treated with genipin from 0-10 mM concentration[

75]. Overall, the concentration above 5mM concentration causes cell death in L929 fibroblast cells.

Dialdehyde starch

The dialdehyde starch is prepared by selective oxidation of starch using sodium periodate or potassium iodate[

76,

77]. The oxidation converts the starch to dialdehyde starch by cleaving the C2 and C3 bond in anhydroglucose and as a result, two aldehyde groups form[

71]. This dialdehyde starch acts as an excellent cross-linker for proteins and polysaccharides. The crosslinking occurs when dialdehyde reacts with amino acids and forms intermolecular bonds in the protein. The advantages of using it as a cross-linker are, it is less reactive and does not change the triple helical structure in the proteins. Wisniewska et al. used dialdehyde starch as an alternative to glutaraldehyde-based cross-linker for the collagen-based scaffold and performed the enzyme degradation study[

76]. The addition of 10% dialdehyde starch provides higher resistance to collagenase enzyme and this is due to the peptide bond between the amino acid preventing the enzyme from penetrating collagen tissue resulting in higher degradation resistance.

3.3.2. Dual Crosslinker

Recently, the dECM-based hydrogel was cross-linked using dual crosslinking techniques. This involved using both photo and thermal crosslinking to achieve the gelation of the 3D shape. For photo crosslinking, visible light or green light was exposed to the dECM bio-ink with photo-initiators like Eosin, triethanolamine, N-Vinylpyrrolidone, and vitamin B2[

9,

71,

78]. Later, the bioink is incubated at 37-40ºC to achieve thermal gelation. Overall, optimizing the concentration of the cross linker and duration of light exposed to the dECM plays a major role in printing the complex anatomical structure, and desired biomechanical properties and biocompatibility [

78].

Eosin & triethanolamine

Yeleswarapu et al. performed dual crosslinking of the decellularized smooth muscle matrix hydrogel with eosin & triethanolamine and visible light[

9]. The result showed that among 0.2 mM concentration of eosin crosslinked with dECM hydrogel has achieved excellent complex modulus, while it was varied from (0.03 to 0.5mM). There were no significant differences above 0.2 nM because of the saturation of the crosslinking agent in the hydrogel. Dual cross-linking also allows printing of a flexible structure and enhances L929 cell viability compared to the only visible crosslinked dECM hydrogel.

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl)-N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC-NHS)

Carbodiimide usually crosslinks with proteins and polysaccharides that contain functional groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl, and sulfhydryl in their chemical structure[

79]. The mechanism of collagen cross-link with EDC-NHS includes the formation of a covalent bond with a carboxylic group of aspartic and glutamic acid[

54]. These bonds in the collagen fiber create high mechanical strength and resistance to enzyme degradation. The carbodiimide in the EDC commence the formation of urea group and additions of NHS converts urea into carboxylic acid. Omobono et al. enhanced the stiffness of rat tail collagen-based hydrogel using dual cross-linking with EDC-NHS and exposing it to green light[

80]. The result shows that dual cross-linking collagen hydrogel provides a storage modulus is 117.6 ± 6.9 Pa which is 5 times higher than the photocross-linked collagen.

Vitamin B2

Jang et al. decellularized porcine left ventricles and cross-linked them using various concentrations (0.01-0.1 w/v %) of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light. The biocompatibility and mechanical properties of these decellularized tissues were evaluated by seeding them with cardiac cells in a bio-ink[

78]. Compressive modulus of crosslinked hydrogel was 15.74kPa, which is comparable similar for the native myocardium tissue. Moreover, the metabolic activity of cardiac cells was high when the hydrogel was treated with in 0.02% vitamin B2, and less in the 0.1% treatment.

Microbial transglutaminase (mTG)

mTG is obtained from the

Streptoverticillium mobaraense enzyme that is capable of cross-linking with protein molecules. The mechanism of crosslink occurs by the formation of isopeptide bonds between λ-carboxyamide groups and the ε-amino groups[

81]. Basara et al. develop the dECM bio-ink from the human left ventricle and combined it with gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) or hyaluronic acid to tune the mechanical stability of the bio-ink, by cross-link with mTG (80mg/ml) and UV light[

82]. The Young’s modulus of the bio-ink in all the treatment groups with cross-linker was observed to be higher than the untreated group. This indicates that dual crosslinking can enhance the mechanical stability of the bio-ink. Similarly, Kara et al. cross-linked the decellularized rabbit bone tissue and gelatin using 10% mTG and studied the cytocompatibility in the pre-osteoblast cell lines for 21 days. The cross-linked dECM hydrogel allowed for for proliferation of cells throughout the incubation period. Yang et al. studied the effects of different crosslinking agents such as glutaraldehyde, genipin, EDC, and mTG on the gelatin scaffold[

83]. Due to its excellent porosity, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility, mTG showed better results than the other crosslinking agents.

3.3.3. Chemical

Chemical crosslinking involves the use of crosslinking agents that can generate strong and durable covalent bonds to improve the properties of dECM bioink[

71]. Compared to physical crosslinking, the chemical method gives better stability and mechanical properties under physiological conditions. Some of the chemical crosslinking methods include photopolymerization, click chemistry, dynamic covalent crosslinking etc.

PEGDA

Lu et al. used the various combination of dECM and PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) to crosslink with PEGDA (Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate) to generate a 3D-printed meniscus[

70]. The alginate chains formed ionic networks, and PEGDA chains formed covalent bond networks along with dECM providing the necessary biological factors for meniscus tissue regeneration. 10% (w/v) PEGDA was added as a crosslinker and it was allowed to photo crosslink using a photo initiator.

Glutaraldehyde

Glutaraldehyde is a widely used five-carbon aliphatic molecule with an aldehyde group at each end of the chain. GA has mixed hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties which can allow rapid penetration into cell membranes and aqueous systems. It has high crosslinking efficiency but has less biocompatibility due to the presence of residues or hydrolytic/enzymatic degradation of linkages[

71,

84]. Collagen meniscal implant is fabricated by glutaraldehyde crosslinking and freezing.

3.3.4. Enzymatic

Enzymatic crosslinking forms strong covalent bonds with rapid reaction rates under physiological conditions. In general, various enzymes like transglutaminase, tyrosinase, horseradish peroxidase, and lysyl oxidase can catalyze covalent crosslinking [

71]. Protein-lysine 6- oxidase (lysyl oxidase) is a cuproenzyme that forms covalent linkages to crosslink collagen and elastin fibrous proteins thus stabilizing the extracellular matrix[

12,

56]. The catalytic mechanism is the oxidative deamination of lysines and hydroxylysines to aldehydes, which further reacts with amino groups by Schiff-base reaction to form imine bonds. On the other hand, tyrosinase is also a copper-containing enzyme that oxidizes phenol to quinone and catechol groups which can further react with amino groups[

56]. Khati et al. have used tyrosinase as a crosslinker to develop a multi-material decellularized liver matrix bio-ink reinforced with PEG and gelatin[

53]. Tyrosinase was added dropwise in a concentration of 500 units per ml and the 3D structure was allowed to crosslink at 37°C for 1 hour. It led to a heavily crosslinked structure exhibiting a 16-fold increase in viscosity and a 32-fold increase in storage modulus. Therefore enzymatic crosslinking is a cytocompatible method that can be done in physiological temperatures for extended 3D printing applications.

3.3.5. Physical

pH

pH induces gelation of dECM, which is based on ECM proteins like GAG, collagen, and elastin[

11]. These proteins are composed of carboxylic and amino groups. The ionization state of the amino acid group exposes hydrophobic regions, increasing interactions and leading to aggregation, ultimately forming a three-dimensional network that traps water molecules during pH changes[

85]. The optimal pH varies in dECM hydrogel depending upon the composition of the hydrogel[

86]. In general, for the dECM-based bio-ink, the pH is kept in the physiological range of 7.0[

53]. A pH below 6 or above 9 might cause protein denaturation or prevent the proper gelation or solubilization of the protein structure. Usually, the pH of the dECM solution adjusts to 7.4 by using 10 N NaOH solutions for the gelation process. Wang et al. studied the effect of different pH levels on the biomechanical strength of the 3D-printed meniscus[

33]. In contrast, at pH 11, there is a significant increase in compressive modulus of dECM hydrogel above 150kPa which is due to the net positive charge decrease in the collagen fiber and enhances the electrostatic interactions between the triple helices allowing the formation of a denser network compared to the pH 7.4.

Temperature

The effect of temperature plays a major role in the gelation of dECM hydrogel. Most of the bioprinter have a separate temperature controller for the extrusion nozzle and printing bed[

85]. The optimal extrusion nozzle temperature is always maintained between 20-25ºC for bio-ink with cells to prevent the shear force during the extrusion of dECM bio-ink[

32]. Whereas, the printing bed maintains 30-37ºC for the solidification of bioink and provides a suitable temperature for cell survival [

18,

43,

54,

57]. In contrast, Khati et al. experimented by extruding dECM bio-ink with HepG2 cells at 37 ºC to achieve excellent cell viability[

53]. To prevent structural damage of the printed structure, the sample was immediately incubated in a 500 U/ml tyrosinase solution for 1 hour. This treatment enhanced the stability of the dECM bio-ink and acheive the cell viability upto 93%.

UV light

UV light crosslinking can create free radicals on aromatic amino acids like tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine, leading to interactions and the formation of chemical bonds[

75]. For UV crosslinking, photoinitiators like 1-[4-(2-hydroxyethoxy) phenyl]-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-1-propanol, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate, and ruthenium are used[

43]. Commonly, UV light at 405 nm wavelength is used due to its penetration depth, cell viability, and better photoinitiator absorption[

85]. In contrast, 254 nm UV light is often used as a strong sterilizing agent to damage the genetic material of microorganisms. Recently, many research groups have utilized UV light combined with dual crosslinking agents like EDC/NHS and vitamin B2 to achieve improved rheological and biomechanical properties[

9,

71,

78]. Jang et al. developed the dECM bioink using porcine left ventricles and crosslink using vitamin B2 and exposed with and without UVA light at 30 mWcm

-2 for 3 minutes[

78]. Crosslinking of dECM bioink with 0.1% of vitamin B2 with UV caused cytotoxic to the cardiac cells. This indicates the duration of exposure and concentration influence the viability of the cells

4.0. Summary

This review examines the anatomy, microstructure, and biomechanical properties of the meniscus, and the criteria necessary for bioinks aimed at 3D printing meniscus tissue. The goal of 3D printing the meniscus using a decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) is to obtain a cell-free matrix that retains essential ECM components like collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycan, which are crucial for its inherent function. Notably, extrusion and inkjet printing techniques are only used for fabricating the dECM hydrogel, because of their high resolution, precision in printing the complex geometry, support for photo cross-linking, and cause less damage to cells. Stereo lithography and laser-induced forward transfer bioprinters lack control over the internal structure, causing damage to the hydrogel and cells. Recent dECM crosslinking methods, particularly the dual crosslinking approach, which combines natural and physical crosslinking methods, have shown promising results in improving dECM crosslinking efficiency. This approach is expected to become a standard technique for developing 3D-printed meniscus from dECM matrices. Overall, a combination of crosslinking agents appears to be a better option as compared to single crosslinking agents, offering unaltered dECM, enhanced biomechanical strength, reduced cytotoxicity, and improved biocompatibility.

Most of the biocompatibility studies showed that MSC cells derived from bone marrow, and adipose tissue are used, because of the ease of availability and their ability to differentiate into chondrocytes and fibrocyte cells. However, the MSC lacks specific phenotype, biochemical cues and functional characteristics of meniscus cells which can differentiate to other cell types. Therefore, studying biocompatibility on meniscus cells possesses inherent functional characteristics like cell specificity. The study will also provide essential cues for cell behavior, tissue development and the natural ability of meniscus cells to interact with ECM for withstanding mechanical stress.

The review emphasizes that meniscus from various animal sources, such as bovine, porcine, caprine, and human, are frequently used for decellularization. In contrast, alternative materials like pericardium, liver, and heart tissue from animal sources remain less explored. 3D printing using bio-ink, particularly with dECM and advanced crosslinking techniques, may contribute significantly to meniscus tissue engineering. The property gradients of the native meniscus can be mimicked by lattice structures and composition. 3D printing holds the prospect of providing functional and robust material for the damaged meniscus, which can ultimately improve the patient’s quality of life. Future directions in 3D printing technology emphasizes major areas which includes optimization of printing parameters, in vivo studies, tailoring solutions to the Indian population. A continuous upgrade is needed to optimize the printing parameters such as nozzle size, printing speed, and thickness which will help to achieve precise control over the 3D-printed structure. Simultaneously, extensive in vivo studies are necessary to determine the long-term biocompatibility, biomechanical properties, and clinical potency of 3D-printed meniscus implants. Acquisition of MRI data from the Indian population offers a scalable strategy for the development of meniscus implants specifically designed to cater the anatomical and physiological needs of the Indian population, addressing disparities in access and affordability.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by the Indian Insitute of Technology Madras, and we thank Dr. Amit Nain for assisting with proofreading.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contribution

Lakshminath Kundanati and Thirumalai Deepak developed the outline of the research work. Writing- Original draft -Thirumalai Deepak, Nagarajan Janani, Surendran Vivek, Sarah Biju wrote the manuscript under the supervision of Lakshminath Kundanati.

References

- Stocco, T. D.; Silva, M. C. M.; Corat, M. A. F.; Lima, G. G.; Lobo, A. O. Towards Bioinspired Meniscus-Regenerative Scaffolds: Engineering a Novel 3D Bioprinted Patient-Specific Construct Reinforced by Biomimetically Aligned Nanofibers. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, E.; Porzionato, A.; De Rose, E.; Barbon, S.; Caro, R. De; Macchi, V. Meniscus Regeneration by 3D Printing Technologies: Current Advances and Future Perspectives; 2022; Vol. 13. [CrossRef]

- van Minnen, B. S.; van Tienen, T. G. The Current State of Meniscus Replacements. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2024, 17 (8), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluyskens, L.; Debieux, P.; Wong, K. L.; Krych, A. J.; Saris, D. B. F. Biomaterials for Meniscus and Cartilage in Knee Surgery: State of the Art. J. ISAKOS 2022, 7 (2), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarmann, G. J.; Gaston, J.; Ho, V. B. A Review of Strategies for Development of Tissue Engineered Meniscal Implants. Biomater. Biosyst. 2021, 4 (May), 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A. C.; Fritz, J.; Kesselring, A.; Schüssler, F.; Otahal, A.; Nehrer, S. Biomechanical Testing of Virtual Meniscus Implants Made from a Bi-Phasic Silk Fibroin-Based Hydrogel and Polyurethane via Finite Element Analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 162 (November 2024), 106830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, K.; Sun, J. Utilizing Bioprinting to Engineer Spatially Organized Tissues from the Bottom-Up. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wehrle, E.; Rubert, M.; Müller, R. 3d Bioprinting of Human Tissues: Biofabrication, Bioinks and Bioreactors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeleswarapu, S.; Dash, A.; Chameettachal, S.; Pati, F. 3D Bioprinting of Tissue Constructs Employing Dual Crosslinking of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 152 (May), 213494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theus, A. S.; Ning, L.; Hwang, B.; Gil, C.; Chen, S.; Wombwell, A.; Mehta, R.; Serpooshan, V. Bioprintability: Physiomechanical and Biological Requirements of Materials for 3d Bioprinting Processes. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12(10), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska, A. A.; Intravaia, J. T.; Sathe, V. M.; Kumbar, S. G.; Nukavarapu, S. P. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Biomaterials for Regenerative Therapies: Advances, Challenges and Clinical Prospects. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32 (October 2023), 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignes, H.; Conzatti, G.; Hua, G.; Benkirane-Jessel, N. Meniscus Repair: From In Vitro Research to Patients. Organoids 2022, 1(2), 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameri, E. S.; Dasari, S. P.; Fortier, L. M.; Verdejo, F. G.; Gursoy, S.; Yanke, A. B.; Chahla, J. Review of Meniscus Anatomy and Biomechanics. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2022, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarmann, G. J.; Piroli, M. E.; Loverde, J. R.; Nelson, A. F.; Li, Z.; Gilchrist, K. H.; Gaston, J. D.; Ho, V. B. 3D Printing a Universal Knee Meniscus Using a Custom Collagen Ink. Bioprinting 2023, 31 (December 2022), e00272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M. Z.; Dou, Y.; Ai, L. Y.; Su, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. R.; Jiang, D. Meniscus Heterogeneity and 3D-Printed Strategies for Engineering Anisotropic Meniscus. Int. J. Bioprinting 2023, 9(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, M.; Filippone, G.; Best, T. M.; Jackson, A. R.; Travascio, F. Mechanical Properties of Meniscal Circumferential Fibers Using an Inverse Finite Element Analysis Approach. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126 (December 2021), 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, E. H.; Matuska, A. M.; McFetridge, P. S.; Allen, K. D. Mechanical Integrity of a Decellularized and Laser Drilled Medial Meniscus. J. Biomech. Eng. 2016, 138(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M. K.; Jeong, W.; Lee, S. M.; Kim, J. B.; Jin, S.; Kang, H. W. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Based Bio-Ink with Enhanced 3D Printability and Mechanical Properties. Biofabrication 2020, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Qu, F.; Han, B.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Mauck, R. L.; Han, L. Micromechanical Anisotropy and Heterogeneity of the Meniscus Extracellular Matrix. Acta Biomater. 2017, 54, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, A. L.; Guilak, F. Mechanobiology of the Meniscus. J. Biomech. 2015, 48(8), 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B. S.; Cudworth, K. F.; Wale, M. E.; Siegel, D. N.; Lujan, T. J. Tensile Fatigue Strength and Endurance Limit of Human Meniscus. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 127 (December 2021), 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Filippone, G.; Best, T. M.; Jackson, A. R.; Travascio, F. Mechanical Properties of Meniscal Circumferential Fibers Using an Inverse Finite Element Analysis Approach. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126 (December 2021), 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhan, K. Meniscal Tears: Current Understanding, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus 2020, 12(6), 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruckeberg, B. M.; Krych, A. J.; Lamba, A.; Wulf, C. A.; Knudsen, M. L.; Camp, C. L. Meniscal Injuries Are Decreasing but Are Increasingly Being Treated Surgically With Excellent Return to Play Rates in Professional Baseball Players. Arthrosc. Sport. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 5(5), 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zuo, J. Natural Biopolymer Scaffold for Meniscus Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10 (September), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Floyd, E. R.; A Kowalski, M.; Aikman, E.; Elrod, P.; Burkey, K.; Chahla, J.; LaPrade, R. F.; Maher, S. A.; Robinson, J. L.; Patel, J. M. Meniscal Repair: The Current State and Recent Advances in Augmentation. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39(7), 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abpeikar, Z.; Javdani, M.; Alizadeh, A.; Khosravian, P.; Tayebi, L.; Asadpour, S. Development of Meniscus Cartilage Using Polycaprolactone and Decellularized Meniscus Surface Modified by Gelatin, Hyaluronic Acid Biomacromolecules: A Rabbit Model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 213, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, T.; Pitsilos, C.; Verdonk, R.; Verdonk, P. Segmental Meniscal Replacement. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2023, 3(1), 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dang, H.; Xu, Y. Recent Advancement of Decellularization Extracellular Matrix for Tissue Engineering and Biomedical Application. Artif. Organs 2022, 46(4), 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Du, A.; Liu, S.; Lv, M.; Chen, S. Research Progress in Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Derived Hydrogels. Regen. Ther. 2021, 18, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, A. D.; Moser, M. A. J.; Chen, X. Preparation and Use of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Dai, W.; Yan, W.; Sun, M.; Ding, G.; Li, Q.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Duan, X.; Hu, X.; Ao, Y. Comparison of Three Different Acidic Solutions in Tendon Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bio-Ink Fabrication for 3D Cell Printing. Acta Biomater. 2021, 131, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Barceló, X.; Von Euw, S.; Kelly, D. J. 3D Printing of Mechanically Functional Meniscal Tissue Equivalents Using High Concentration Extracellular Matrix Inks. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20 (April). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, F.; Jang, J.; Ha, D.; Won Kim, S.; Rhie, J.; Shim, J.; Kim, D.; Cho, D. Printing Three-Dimensional Tissue Analogues with Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioink. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5(1), 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Gao, G.; Cho, D. W. Tissue-Specific Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioinks for Musculoskeletal Tissue Regeneration and Modeling Using 3d Bioprinting Technology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perusko, M.; Grundström, J.; Eldh, M.; Hamsten, C.; Apostolovic, D.; van Hage, M. The α-Gal Epitope - the Cause of a Global Allergic Disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15 (January), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuravi, K. V.; Sorrells, L. T.; Nellis, J. R.; Rahman, F.; Walters, A. H.; Matheny, R. G.; Choudhary, S. K.; Ayares, D. L.; Commins, S. P.; Bianchi, J. R.; Turek, J. W. Allergic Response to Medical Products in Patients with Alpha-Gal Syndrome. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 164(6), e411–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Yee, M.; Sheng, Z. L. J.; Amirul, A.; Naing, M. W. Decellularization Systems and Devices: State-of-the-Art. Acta Biomater. 2020, 115, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-G.; Kim, S. H.; Choi, S. Y.; Kim, Y. J. Anticalcification Effects of Decellularization, Solvent, and Detoxification Treatment for Genipin and Glutaraldehyde Fixation of Bovine Pericardium. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2012, 41(2), 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarpour, R.; Masaeli, E.; Kermani, S. Development of Meniscus-inspired 3D-printed PCL Scaffolds Engineered with Chitosan/Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32(12), 4721–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Hong, H.; Hu, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, C. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds: Recent Trends and Emerging Strategies in Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10 (September 2021), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, T.; Babu, A. R. A Review of Current Approaches for Decellularization, Sterilization, and Hemocompatibility Testing on Xenogeneic Pericardium. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33 (September), 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, L. Strategies for Improving the 3D Printability of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioink. Theranostics 2023, 13(8), 2562–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, L.; She, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, N. Microstructural and Micromechanical Properties of Decellularized Fibrocartilaginous Scaffold. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H. W.; Song, B. R.; Shin, D. Il; Yin, X. Y.; Truong, M. D.; Noh, S.; Jin, Y. J.; Kwon, H. J.; Min, B. H.; Park, D. Y. Fabrication of Decellularized Meniscus Extracellular Matrix According to Inner Cartilaginous, Middle Transitional, and Outer Fibrous Zones Result in Zone-Specific Protein Expression Useful for Precise Replication of Meniscus Zones. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 128, 112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. B.; Fazel Anvari-Yazdi, A.; Duan, X.; Zimmerling, A.; Gharraei, R.; Sharma, N. K.; Sweilem, S.; Ning, L. Biomaterials / Bioinks and Extrusion Bioprinting. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28 (June), 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M. A.; Khoda, B. Rheological Analysis of Bio-Ink for 3D Bio-Printing Processes. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 76 (February), 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomaa, L.; Almalla, A.; Keshi, E.; Hillebrandt, K. H.; Sauer, I. M.; Weinhart, M. Rise of Tissue- and Species-Specific 3D Bioprinting Based on Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Derived Bioinks and Bioresins. Biomater. Biosyst. 2023, 12 (June), 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, E.; Meyer, A. S.; Ikuma, K.; Rivero, I. V. Three Dimensional Printed Biofilms: Fabrication, Design and Future Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S. H.; Park, T. Y.; Cha, H. J.; Yang, Y. J. Photo-/Thermo-Responsive Bioink for Improved Printability in Extrusion-Based Bioprinting. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 25 (July 2023), 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jia, L.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, G.; Chen, W.; Chen, R. Injectable Photo-Crosslinking Cartilage Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Cartilage Tissue Regeneration. Mater. Lett. 2020, 268, 127609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abadi, H.; Thai, H. T.; Paton-Cole, V.; Patel, V. I. Elastic Properties of 3D Printed Fibre-Reinforced Structures. Compos. Struct. 2018, 193 (March), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khati, V.; Ramachandraiah, H.; Pati, F.; Svahn, H. A.; Gaudenzi, G.; Russom, A. 3D Bioprinting of Multi-Material Decellularized Liver Matrix Hydrogel at Physiological Temperatures. Biosensors 2022, 12(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronca, A.; D’Amora, U.; Capuana, E.; Zihlmann, C.; Stiefel, N.; Pattappa, G.; Schewior, R.; Docheva, D.; Angele, P.; Ambrosio, L. Development of a Highly Concentrated Collagen Ink for the Creation of a 3D Printed Meniscus. Heliyon 2023, 9(12), e23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Lee, S. S.; Choi, Y. J.; Hong, D. H.; Gao, G.; Wang, J. H.; Cho, D. W. 3D Cell-Printing of Biocompatible and Functional Meniscus Constructs Using Meniscus-derived Bioink. Biomaterials 2021, 267 (October 2020), 120466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort-Mascort, J.; Flores-Torres, S.; Peza-Chavez, O.; Jang, J. H.; Pardo, L. A.; Tran, S. D.; Kinsella, J. Decellularized ECM Hydrogels: Prior Use Considerations, Applications, and Opportunities in Tissue Engineering and Biofabrication. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 11(2), 400–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamchand, L.; Makeiff, D.; Gao, Y.; Azyat, K.; Serpe, M. J.; Kulka, M. Biomaterial Inks and Bioinks for Fabricating 3D Biomimetic Lung Tissue: A Delicate Balancing Act between Biocompatibility and Mechanical Printability. Bioprinting 2023, 29 (November 2022), e00255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirian, F.; Mozafari, M. Decellularized ECM-Derived Bioinks: Prospects for the Future. Methods 2020, 171 (February 2019), 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiguera, S.; Del Gaudio, C.; Di Nardo, P.; Manzari, V.; Carotenuto, F.; Teodori, L. 3D Printing Decellularized Extracellular Matrix to Design Biomimetic Scaffolds for Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardo, G.; Petretta, M.; Cavallo, C.; Roseti, L.; Durante, S.; Albisinni, U.; Grigolo, B. Patient-Specific Meniscus Prototype Based on 3D Bioprinting of Human Cell-Laden Scaffold. Bone Joint Res. 2019, 8(2), 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Yin, Z.; Yu, X. Fabrication and Evaluation of Porous DECM/PCL Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Ghibhela, B.; Mandal, B. B. Current Advances in Engineering Meniscal Tissues: Insights into 3D Printing, Injectable Hydrogels and Physical Stimulation Based Strategies. Biofabrication 2024, 16(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H. J.; Lee, S. W.; Hong, M. W.; Kim, Y. Y.; Seo, K. D.; Cho, Y. S.; Lee, S. J. Total Meniscus Reconstruction Using a Polymeric Hybrid-Scaffold: Combined with 3d-Printed Biomimetic Framework and Micro-Particle. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Q.; Tian, Z.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, M. Recent Advances in 3D Bioprinted Cartilage-Mimicking Constructs for Applications in Tissue Engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23 (November). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, A. L.; Lyons, L. P.; Perea, S. H.; Weinberg, J. B.; Wittstein, J. R. Meniscus-Derived Matrix Bioscaffolds: Effects of Concentration and Cross-Linking on Meniscus Cellular Responses and Tissue Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottathara, Y. B.; Kokol, V. Effect of Nozzle Diameter and Cross-Linking on the Micro-Structure, Compressive and Biodegradation Properties of 3D Printed Gelatin/Collagen/Hydroxyapatite Hydrogel. Bioprinting 2023, 31 (January), e00266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, P. S.; Orrhult, L. S.; Martínez, H. Bioprinting of Cartilage and Skin Tissue Analogs Utilizing a Novel Passive Mixing Unit Technique for Bioink Precellularization. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 2018(131), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, S.; Ahlfeld, T.; Albrecht, F.; Duin, S.; Kluger, P.; Lode, A.; Gelinsky, M. Homogeneous and Reproducible Mixing of Highly Viscous Biomaterial Inks and Cell Suspensions to Create Bioinks. Gels 2021, 7(4), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina, J. A.; Cordeiro, M. H.; Milivojevic, M.; Pajić-Lijaković, I.; Barriga, E. H. Response of Cells and Tissues to Shear Stress. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136(18), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Jin, J.; Xie, C.; Xue, B.; Lai, J.; Cheng, B.; Li, L.; Jiang, Q. The Design and Characterization of a Strong Bio-Ink for Meniscus Regeneration. Int. J. Bioprinting 2022, 8(4), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Peijie, T.; Nan, J. Crosslinking Strategies of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix in Tissue Regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part A 2024, 112(5), 640–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. W.; Lin, Y. H.; Lin, T. L.; Lee, K. X. A.; Yu, M. H.; Shie, M. Y. 3D-Biofabricated Chondrocyte-Laden Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Contained Gelatin Methacrylate Auxetic Scaffolds under Cyclic Tensile Stimulation for Cartilage Regeneration. Biofabrication 2023, 15(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setayeshmehr, M.; Hafeez, S.; van Blitterswijk, C.; Moroni, L.; Mota, C.; Baker, M. B. Bioprinting via a Dual-Gel Bioink Based on Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) and Solubilized Extracellular Matrix towards Cartilage Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.; Zhang, N.; Dong, L.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, B. The Effects of Different Crossing-Linking Conditions of Genipin on Type I Collagen Scaffolds: An in Vitro Evaluation. Cell Tissue Bank. 2014, 15(4), 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, K.; Sionkowska, A. Current Methods of Collagen Cross-Linking: Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Dialdehyde Starch by One-Step Acid Hydrolysis and Oxidation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannous, A.; Milaneh, S.; Said, M.; Atassi, Y. New Approach for Starch Dialdehyde Preparation Using Microwave Irradiation for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Water. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4(5), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Kim, T. G.; Kim, B. S.; Kim, S. W.; Kwon, S. M.; Cho, D. W. Tailoring Mechanical Properties of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioink by Vitamin B2-Induced Photo-Crosslinking. Acta Biomater. 2016, 33, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavarse, A. C.; Frachini, E. C. G.; da Silva, R. L. C. G.; Lima, V. H.; Shavandi, A.; Petri, D. F. S. Crosslinkers for Polysaccharides and Proteins: Synthesis Conditions, Mechanisms, and Crosslinking Efficiency, a Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202 (January), 558–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omobono, M. A.; Zhao, X.; Furlong, M. A.; Kwon, C. H.; Gill, T. J.; Randolph, M. A.; Redmond, R. W. Enhancing the Stiffness of Collagen Hydrogels for Delivery of Encapsulated Chondrocytes to Articular Lesions for Cartilage Regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part A 2015, 103(4), 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; Benzvi, C. Microbial Transglutaminase Is a Very Frequently Used Food Additive and Is a Potential Inducer of Autoimmune/Neurodegenerative Diseases. Toxics 2021, 9(10), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basara, G.; Ozcebe, S. G.; Ellis, B. W.; Zorlutuna, P. Tunable Human Myocardium Derived Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for 3D Bioprinting and Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Gels 2021, 7(2), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xiao, Z.; Long, H.; Ma, K.; Zhang, J.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J. Assessment of the Characteristics and Biocompatibility of Gelatin Sponge Scaffolds Prepared by Various Crosslinking Methods. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ding, Y.; Pan, W.; Lu, L.; Jin, R.; Liang, X.; Chang, M.; Wang, Y.; Luo, X. A Comparative Study on Two Types of Porcine Acellular Dermal Matrix Sponges Prepared by Thermal Crosslinking and Thermal-Glutaraldehyde Crosslinking Matrix Microparticles. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10 (August), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennifer, A.; Manivannan, S.; Sethuraman, S.; Kumbar, S. G.; Sundaramurthi, D. 3D Bioprinting and Photocrosslinking: Emerging Strategies & Future Perspectives. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xing, F.; Yu, P.; Lu, R.; Ma, S.; Shakya, S.; Zhou, X.; Peng, K.; Zhang, D.; Liu, M. Biomimetic Fabrication Bioprinting Strategies Based on Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Musculoskeletal Tissue Regeneration: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Mater. Des. 2024, 243 (April), 113072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, B. P.; Zaslav, K. R.; Alfred, R. H.; Alley, R. M.; Edelson, R. H.; Gersoff, W. K.; Greenleaf, J. E.; Kaeding, C. C. Preliminary Results From a US Clinical Trial of a Novel Synthetic Polymer Meniscal Implant. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 2020, 8(9), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Idrees, E.; Szojka, A. R. A.; Andrews, S. H. J.; Kunze, M.; Mulet-Sierra, A.; Jomha, N. M.; Adesida, A. B. Chondrogenic Differentiation of Synovial Fluid Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Human Meniscus-Derived Decellularized Matrix Requires Exogenous Growth Factors. Acta Biomater. 2018, 80, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, K.; Rothrauff, B. B.; Tuan, R. S. Region-Specific Effect of the Decellularized Meniscus Extracellular Matrix on Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Meniscus Tissue Engineering. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45(3), 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Feng, Z.; Guo, W.; Yang, D.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Shen, S.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Hao, L.; Peng, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Q. PCL-MECM-Based Hydrogel Hybrid Scaffolds and Meniscal Fibrochondrocytes Promote Whole Meniscus Regeneration in a Rabbit Meniscectomy Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11(44), 41626–41639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapuła, P.; Bialik-Wąs, K.; Malarz, K. Are Natural Compounds a Promising Alternative to Synthetic Cross-Linking Agents in the Preparation of Hydrogels? Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, J.; Guo, M. Mechanical, Microstructural, and Rheological Characterization of Gelatin-Dialdehyde Starch Hydrogels Constructed by Dual Dynamic Crosslinking. LWT 2022, 161 (March), 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Sharifi, H.; Akbari, A.; Chodosh, J. Systematic Optimization of Visible Light-Induced Crosslinking Conditions of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobreiro-Almeida, R.; Gómez-Florit, M.; Quinteira, R.; Reis, R. L.; Gomes, M. E.; Neves, N. M. Decellularized Kidney Extracellular Matrix Bioinks Recapitulate Renal 3D Microenvironment in Vitro. Biofabrication 2021, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).