Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- Strict avoidance of prolonged fasting with early and continuous glucose supplementation.

- Avoidance of propofol and lipid-based therapies, due to impaired fatty acid metabolism.

- Use of lactate-free intravenous solutions to prevent worsening acidosis.

- Selection of cisatracurium over rocuronium, reducing hepatic load and avoiding sugammadex concerns.

- Close interdisciplinary communication to prevent errors such as inappropriate fluid substitutions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

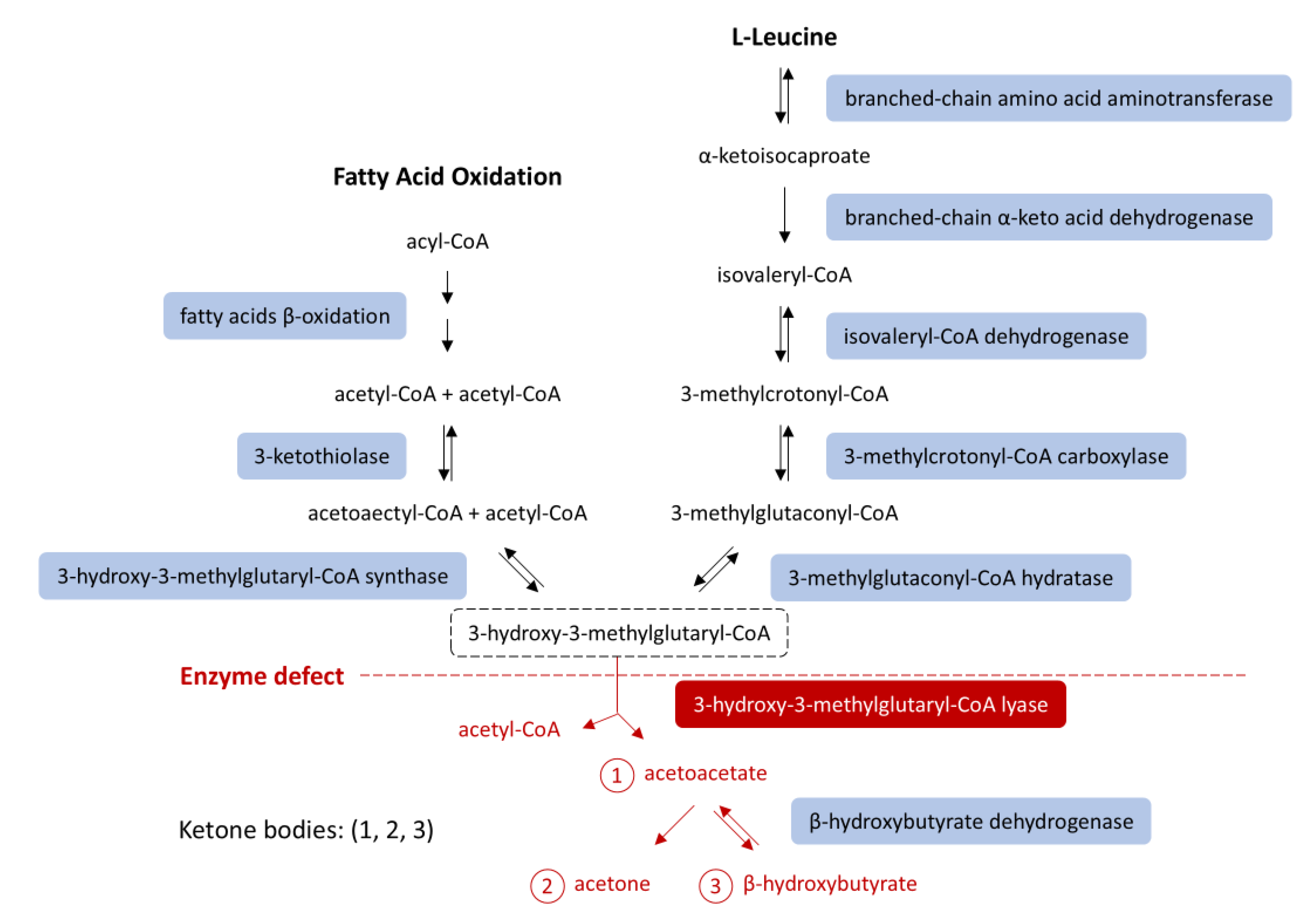

| HMGCLD | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency |

| HMGCL | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase gene |

| HMG-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A |

| PICU | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| IV | Intravenous |

| ABG(s) | Arterial Blood Gas(es) |

| PaO₂ | Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood |

| FiO₂ | Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| PaCO₂ | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood |

| BE | Base excess |

| HCO₃⁻ | Bicarbonate |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| KCl | Potassium chloride |

| MgSO₄ | Magnesium sulfate |

| MAC | Minimum alveolar concentration |

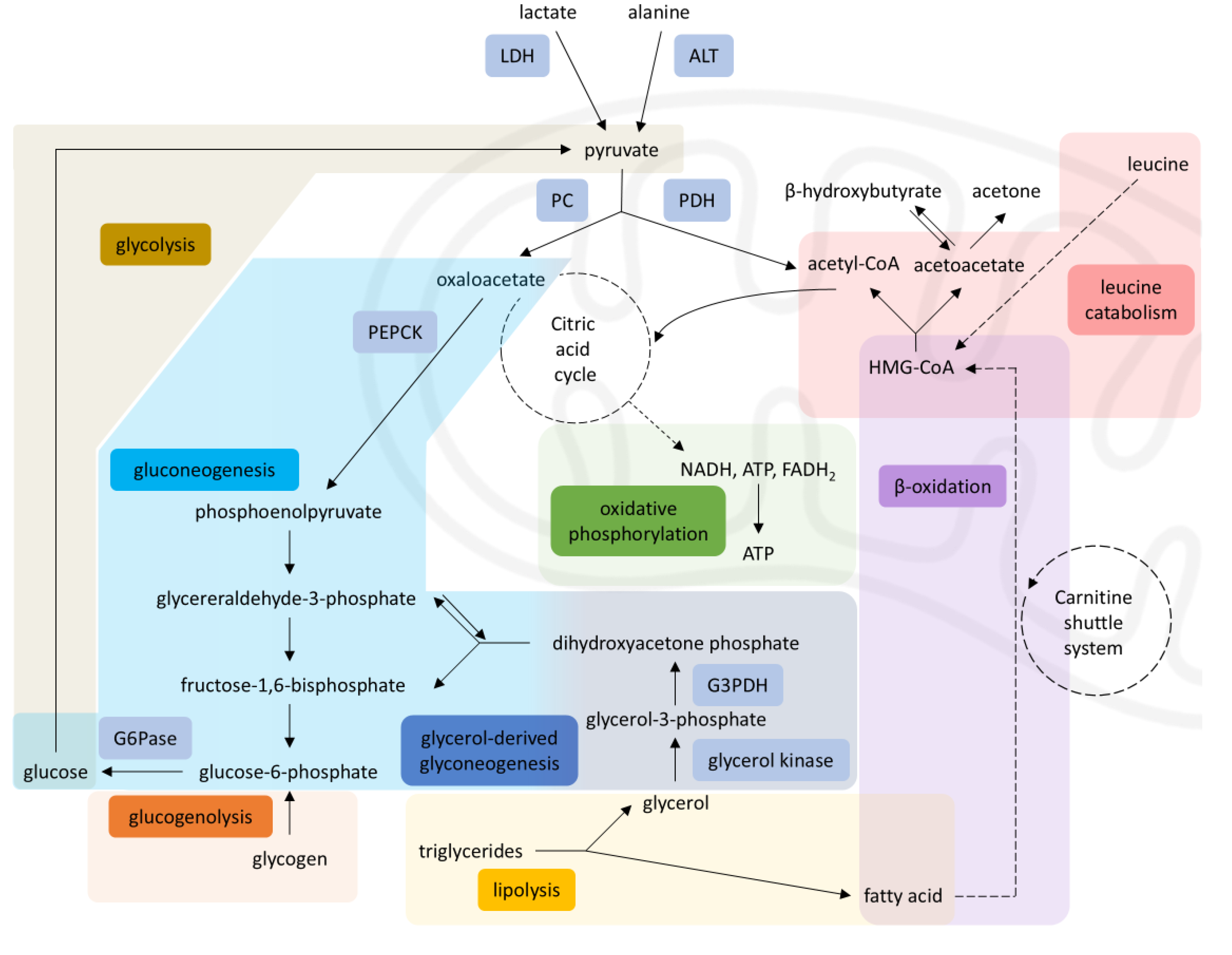

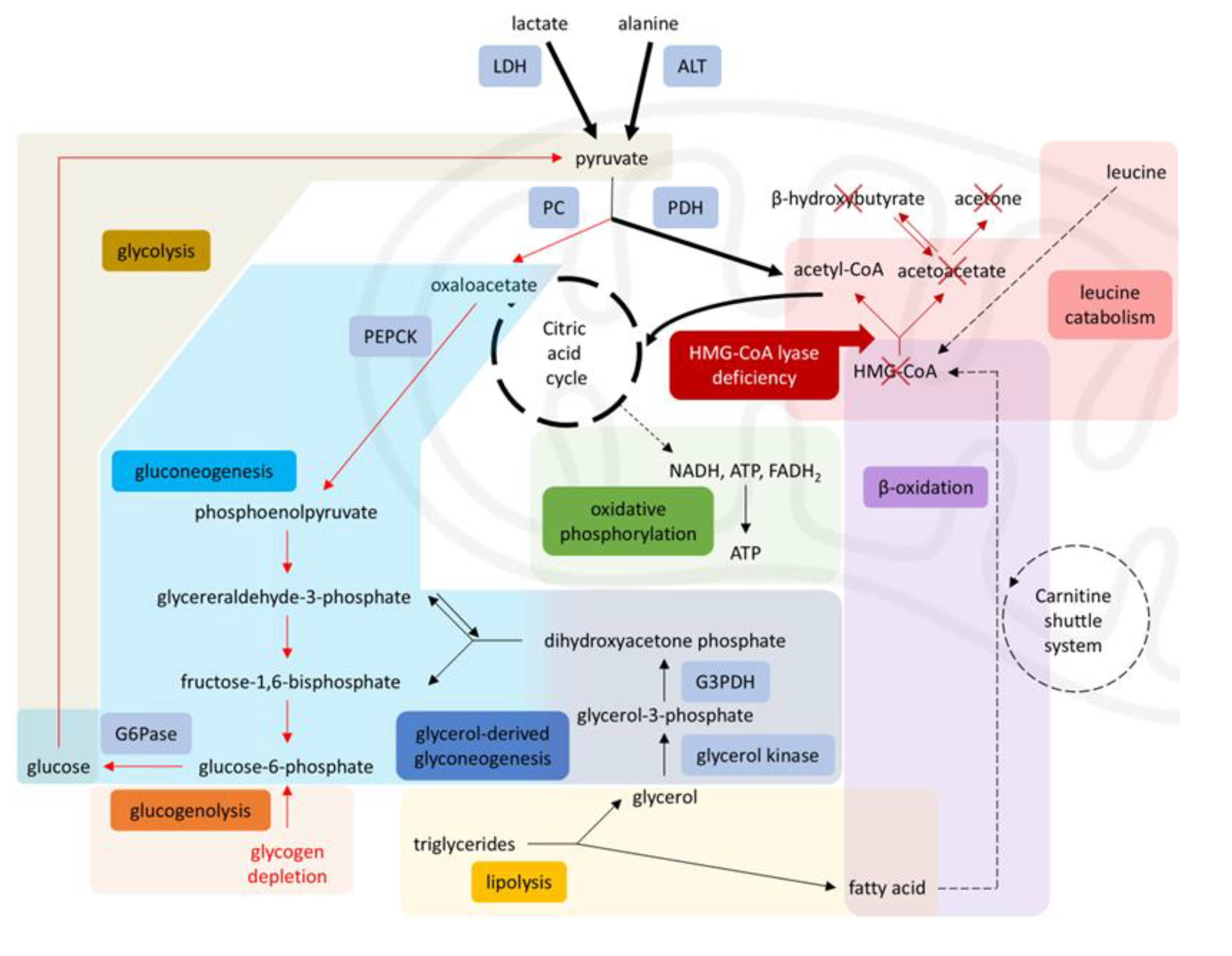

| PC | Pyruvate carboxylase |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| PEPCK | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| G6Pase | Glucose-6-phosphatase |

| G3PDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) |

| FADH₂ | Flavin adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) |

References

- Faull K, Bolton P, Halpern B, others. Patient with Defect in Leucine Metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1013–5.

- Grünert SC, Schlatter SM, Schmitt RN, Gemperle-Britschgi C, Mrázová L, Balcı MC, et al. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A lyase deficiency: Clinical presentation and outcome in a series of 37 patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2017 Jul;121(3):206–15.

- Grünert SC, Sass JO. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A lyase deficiency: one disease - many faces. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020 Feb 14;15(1):48.

- Pié J, López-Viñas E, Puisac B, Menao S, Pié A, Casale C, et al. Molecular genetics of HMG-CoA lyase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2007 Nov;92(3):198–209.

- Thompson S, Hertzog A, Selvanathan A, Batten K, Lewis K, Nisbet J, et al. Treatment of HMG-CoA Lyase Deficiency-Longitudinal Data on Clinical and Nutritional Management of 10 Australian Cases. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 19;15(3):531.

- Leipnitz G, Vargas CR, Wajner M. Disturbance of redox homeostasis as a contributing underlying pathomechanism of brain and liver alterations in 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015 Nov;38(6):1021–8.

- Puisac B, Arnedo M, Concepcion M, Teresa E, Pie A, Bueno G, et al. HMG–CoA Lyase Deficiency. In: Ikehara K, editor. Advances in the Study of Genetic Disorders [Internet]. InTech; 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.intechopen.

- Alfadhel M, Abadel B, Almaghthawi H, Umair M, Rahbeeni Z, Faqeih E, et al. HMG-CoA Lyase Deficiency: A Retrospective Study of 62 Saudi Patients. Front Genet. 2022;13:880464.

- Hatano R, Lee E, Sato H, Kiuchi M, Hirahara K, Nakagawa Y, et al. Hepatic ketone body regulation of renal gluconeogenesis. Mol Metab. 2024;84:101934.

- Holeček, M. Origin and Roles of Alanine and Glutamine in Gluconeogenesis in the Liver, Kidneys, and Small Intestine under Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 27;25(13):7037.

- Kolb H, Kempf K, Röhling M, Lenzen-Schulte M, Schloot NC, Martin S. Ketone bodies: from enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med. 2021 Dec 9;19(1):313.

- Barendregt K, Soeters P, Allison S, Sobotka L. Basics in clinical nutrition: Simple and stress starvation. Eur E-J Clin Nutr Metab. 2008 Dec 1;3(6):e267–71.

- Xiang F, Zhang Z, Xie J, Xiong S, Yang C, Liao D, et al. Comprehensive review of the expanding roles of the carnitine pool in metabolic physiology: beyond fatty acid oxidation. J Transl Med. 2025 Mar 14;23(1):324.

- Olpin, SE. Pathophysiology of fatty acid oxidation disorders and resultant phenotypic variability. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(4):645–58.

- Houten SM, Violante S, Ventura FV, Wanders RJA. The Biochemistry and Physiology of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation and Its Genetic Disorders. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016 Feb 10;78(1):23–44.

- Suzuki T, Komatsu T, Shibata H, Inagaki T. Metabolic Responses to Energy-Depleted Conditions. In: Takada A, Himmerich H, editors. Psychology and Pathophysiological Outcomes of Eating [Internet]. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2021. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Thompson GN, Hsu BYL, Pitt JJ, Treacy E, Stanley CA. Fasting Hypoketotic Coma in a Child with Deficiency of Mitochondrial 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase. N Engl J Med. 1997 Oct 23;337(17):1203–7.

- New England Consortium of Metabolic Programs [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 24]. 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (3-HMG CoA) Lyase Deficiency. Available from: https://www.newenglandconsortium.

- Orphanet: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric aciduria [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.orpha.

- Delgado CA, Balbueno Guerreiro GB, Diaz Jacques CE, Moura Coelho D, Sitta A, Manfredini V, et al. Prevention by L-carnitine of DNA damage induced by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric and 3-methylglutaric acids and experimental evidence of lipid and DNA damage in patients with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric aciduria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019 Jun 15;668:16–22.

- Yu HK, Ok SH, Kim S, Sohn JT. Anesthetic management of patients with carnitine deficiency or a defect of the fatty acid β-oxidation pathway: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Feb 18;101(7):e28853.

- Martins, P. Glutaric acidaemia type 1. Anästh Intensiv. 2020;61(Suppl 6):S108–14.

- Robbins KA, León-ruiz EN. Anesthetic Management of a Patient with 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency. Anesth Analg. 2008 Aug;107(2):648.

- Gunduz Gul G, Ozer AB, Demirel I, Aksu A, Erhan OL. The effect of sugammadex on steroid hormones: A randomized clinical study. J Clin Anesth. 2016 Nov;34:62–7.

- obin KAR, Steineger HH, Alberti S, Spydevold Ø, Auwerx J, Gustafsson JÅ, et al. Cross-Talk between Fatty Acid and Cholesterol Metabolism Mediated by Liver X Receptor-α. Mol Endocrinol. 2000 May 1;14(5):741–52.

- Berthet, V. The Impact of Cognitive Biases on Professionals’ Decision-Making: A Review of Four Occupational Areas. Front Psychol. 2022 Jan 4;12:802439.

| ABGs | Pre-PICU | PICU prior to surgery |

Intraoperative 1 | Intraoperative 2 | Postoperative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.577 | 7.472 | 7.406 | 7.368 | 7.414 | |||

|

PaO2 (mmHg) |

234 | 166 | 201 | 204 | 188.7 | |||

| FiO2 | 0.5 | ~ 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.35 | ~ 0.28 | |||

|

PaCO2 (mmHg) |

16.4 | 28.4 | 30,6 | 34 | 33 | |||

| BE | -4.8 | -2.5 | -5.1 | -5.4 | -1.3 | |||

| HCO3 | 15 | 20.3 | 18.8 | 19.3 | 20.4 | |||

|

Lactate (mmol/L) |

3.38 | 1.64 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |||

|

Glucose (mg/dL) |

74 | 173 | 144 | 177 | 204 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).