1. Introduction

Dynamic Sparse Training (DST) has emerged as a promising paradigm for training artificial neural networks with sparse connectivity, aiming to reduce computational and memory overhead while maintaining performance. Unlike static pruning methods, DST allows network topology to evolve during training, drawing inspiration from synaptic turnover in biological neural networks [

1,

2,

3].

Among recent DST advances, Cannistraci-Hebb Training (CHT) has demonstrated remarkable capabilities in training ultra-sparse networks [

3]. CHT implements epitopological learning—a brain-inspired framework that evolves network topology through structural reorganization rather than solely weight updates. By using the CH3-L3 link predictor for gradient-free regrowth, CHT enables artificial neural networks with merely 1% connectivity to surpass fully connected counterparts in multiple visual tasks.

However, existing CHT methods are primarily designed for fully connected layers, leaving convolutional neural networks (CNNs) largely unexplored. CNNs present unique challenges for topological evolution due to two fundamental constraints: receptive field locality, which limits the spatial range of possible connections, and weight-sharing dependency, which requires grouped manipulation of connections rather than independent link control.

This paper addresses these challenges by extending CHT to convolutional layers through CHT-Conv, using a three-step evolution method. During the evolution, we expanded the mask repeatedly to construct a global topology, which is subsequently used for link prediction. The average value across different sliding windows is then computed to determine which links should be regrowed.

We evaluate CHT-Conv on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using VGG16 architectures. Results demonstrate that CHT-Conv achieves competitive or superior performance compared to traditional dynamic sparse training methods like SET in the same sparsity level. This work represents a significant step toward applying brain-inspired topological learning principles to modern deep learning architectures.

2. Related Work

2.1. Dynamic Sparse Training

Dynamic Sparse Training (DST) has emerged as a promising paradigm for training artificial neural networks (ANNs) with sparse connectivity, aiming to reduce computational and memory overhead while maintaining or even enhancing model performance. Unlike static sparse methods such as pruning-at-initialization [

4], DST allows the network topology to evolve during training, drawing inspiration from synaptic turnover in biological neural networks [

5].

2.2. Epitopological Learning and Cannistraci-Hebb Training

A significant innovation in DST is the introduction of epitopological learning (EL), a brain-inspired framework rooted in network science and complex systems theory [

6,

7,

8]. EL is derived from a dual interpretation of Hebb’s axiom — "neurons that fire together wire together" — and emphasizes epitopological plasticity: the ability of a network to learn through structural reorganization rather than solely through weight updates [

6]. EL can be addressed as a link prediction task using a series of topology-based link predictors such as CH3-L3 [

9], with which Cannistraci-Hebb Training (CHT) [

3] implements EL and demonstrates that artificial neural networks with merely 1% connectivity can surpass fully connected counterparts in multiple visual tasks.

3. CHT-Conv

In this section, we provide a detailed explanation of how the CHT method is extended to convolutional layers within CNN.

3.1. Topology Matrix in Convolutional Layer

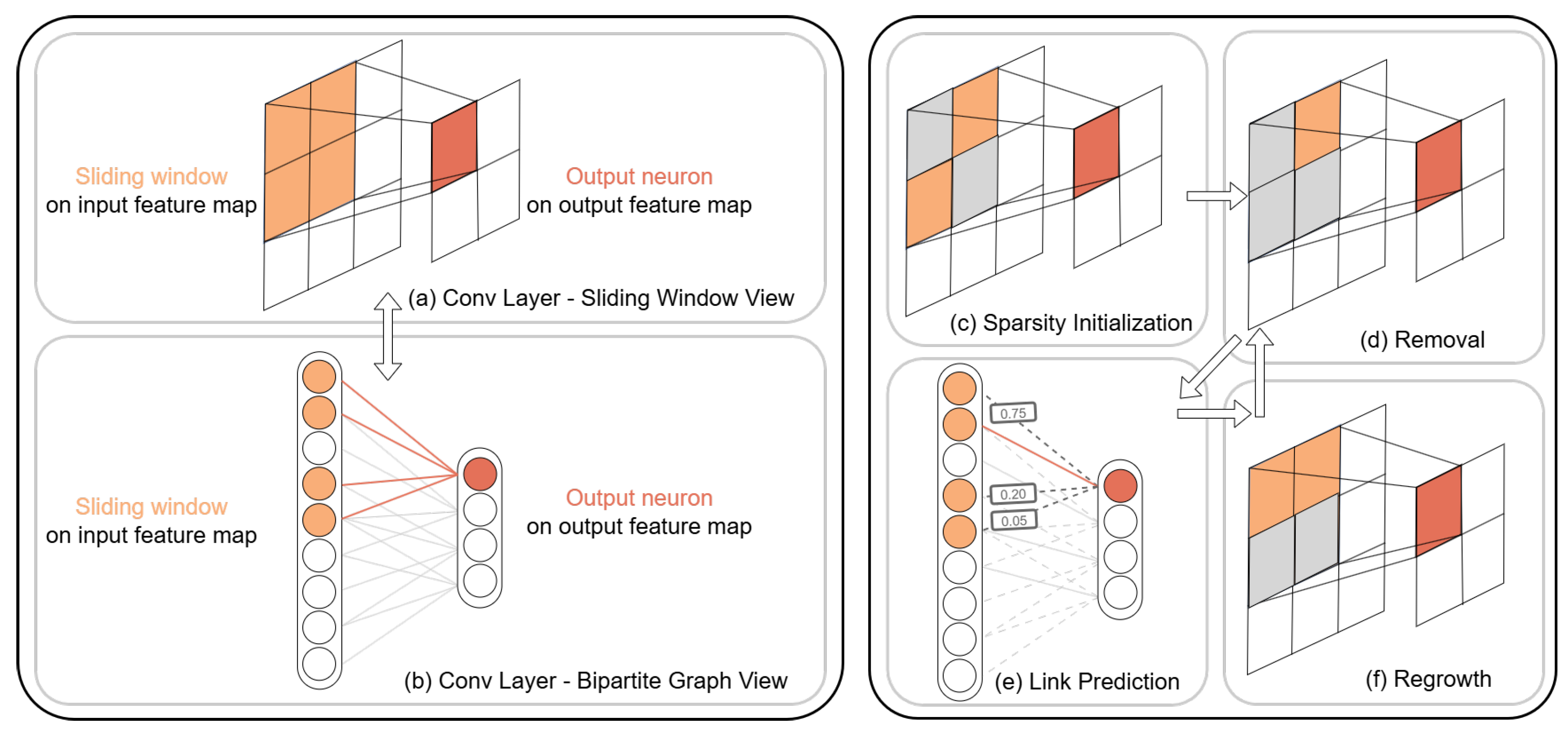

To extend the CHT framework to CNNs, the first essential step is to establish an appropriate definition of topology within convolutional layers. A bipartite graph can be constructed between the inputs and outputs of a convolutional layer. As illustrated in the first column in

Figure 1 (a)(b), for each kernel, the first partite set consists of activations from the input feature maps, while the second partite set comprises neurons corresponding to each sliding window position in the output.

However, the topological structure in convolutional neural networks is subject to two constraints: (1) Receptive Field Locality. Due to the limited receptive field of each sliding window, the range of activations that can connect to a given output neuron is constrained by the network architecture. (2) Weight-Sharing Dependency. Owing to the inherent weight-sharing mechanism in convolutional operations, individual connections cannot be independently removed or regrown.

Constraint 2 poses a challenge for implementing Epitopological Learning via CHT, where the link predictor independently computes a score for each connection in the network topology and selects the most promising ones for regrowth.

3.2. Proposed Method

3.2.1. Initialization

For each convolutional layer, we initialize a random boolean tensor mask of the same shape as each kernel to govern which positions are removed at this phase, as illustrated in

Figure 1 (c). Note that the same mask is applied to all the sliding windows, thereby preserving the shared-weight nature of convolutional operations.

3.2.2. Evolution

The evolution process in CHT-Conv is conducted on a per-kernel basis following the steps below, as shown in

Figure 1 (d)(e)(f).

Removal. On each kernel, a fixed fraction positions with the smallest weight magnitudes are removed.

Link Prediction. For each kernel, we perform link prediction on the bipartite graph formed by the input feature map, the output feature map, and all the active links between them. Each position on the kernel corresponds to multiple links in the graph. We adopts CH link predictors to assign likelyhood scores to the disabled links based on the current topology of the network.

Regrowth. At this stage, an equal number of previously disabled positions are growed back on each kernel. To best preserve the topology identified by the link predictor in the previous step while maintaining the weight-sharing dependency, we compute the average of the likelihood scores for each kernel position across all sliding windows. Given that CH-L3n link predictors only score disabled links, active links are assigned the highest score among disabled. To determine the final regrown positions, CHT [

3] chooses disabled positions with the highest average likelihood scores, whereas CHTs [

10] samples from a multinomial distribution parameterized by these scores.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance of CHT-Conv, we conducted preliminary experiments on two widely-used benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 [

11], with VGG16 [

12] as our backbone. For the CHT-Conv method, we evaluated the performance of the CH2-L3n and CH3-L3n predictors [

10]. The baselines included the dense model and the sparse model trained under SET [

1], which adopts a uniformly random link regrowth procedure. To focus on examining proposed CHT-Conv, when conducting experiments using CHT-Conv or SET, we sparsified only to the convolutional parts while keeping the Multi-Layer Perceptron at the end of the network dense. The detailed experimental setup is described in

Appendix A.

4.2. Results

The accuracy of each experimental group is reported in

Table 1, where the error intervals are derived from standard error. Preliminary experimental results indicate that: (1) As sparsity progressively increases, the performance of the network declines; (2) Compared to SET, the CHT method either outperforms SET (on CIFAR-10) or performs at least comparably to SET (on CIFAR-100).

5. Conclusions

This study extends Cannistraci-Hebb Training to convolutional neural networks through CHT-Conv, addressing the fundamental challenge of applying epitopological learning principles to weight-sharing architectures. Experimental results on CIFAR datasets indicate that CHT-Conv achieves performance competitive with existing dynamic sparse training methods across multiple sparsity levels. In subsequent work, we plan to further refine the performance of CHT-Conv and conduct more extensive experimental evaluations to strengthen its robustness and general applicability.

Appendix A. Experimental Setup

Data Augmentation. For both CIFAR10 and CIFAR100, we applied random horizontal flip (p=0.5) on training set, and normalization with the mean and std on valid and test sets.

Reproducibility. For all experiments, we used the random seeds of 14, 15, and 16. We also turned on all the deterministic flags in Python, Pytorch and NumPy.

Training Hyperparameters.

Table A1.

Hyperparatmeters for Training VGG16 on CIFAR10 and CIFAR100.

Table A1.

Hyperparatmeters for Training VGG16 on CIFAR10 and CIFAR100.

| Dataset |

Optimizer |

Learning Rate |

Batch Size |

#Epochs |

Scheduler |

| CIFAR10 |

Adam |

0.01 |

128 |

100 |

Linear-Linear |

| CIFAR100 |

SGD |

0.1 |

128 |

240 |

Linear-CosAnnealing |

References

- Mocanu, D.C.; Mocanu, E.; Stone, P.; Nguyen, P.H.; Gibescu, M.; Liotta, A. Scalable training of artificial neural networks with adaptive sparse connectivity inspired by network science. Nature communications 2018, 9, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evci, U.; Gale, T.; Menick, J.; Castro, P.S.; Elsen, E. Rigging the lottery: Making all tickets winners. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 2943–2952. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Muscoloni, A. Epitopological learning and cannistraci-hebb network shape intelligence brain-inspired theory for ultra-sparse advantage in deep learning. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Frankle, J.; Carbin, M. The lottery ticket hypothesis: Finding sparse, trainable neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.03635 2018.

- Holtmaat, A.; Svoboda, K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2009, 10, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannistraci, C.V.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Ravasi, T. From link-prediction in brain connectomes and protein interactomes to the local-community-paradigm in complex networks. Scientific reports 2013, 3, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daminelli, S.; Thomas, J.M.; Durán, C.; Cannistraci, C.V. Common neighbours and the local-community-paradigm for topological link prediction in bipartite networks. New Journal of Physics 2015, 17, 113037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannistraci, C.V. Modelling self-organization in complex networks via a brain-inspired network automata theory improves link reliability in protein interactomes. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 15760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscoloni, A.; Michieli, U.; Zhang, Y.; Cannistraci, C.V. Adaptive network automata modelling of complex networks 2022.

- Zhang, Y.; Cerretti, D.; Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Liao, Z.; Michieli, U.; Cannistraci, C.V. Brain network science modelling of sparse neural networks enables Transformers and LLMs to perform as fully connected. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.19107 2025.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G.; et al. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images 2009.

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).